Ruth Loos and colleagues report findings from a meta-analysis of multiple studies examining the extent to which physical activity attenuates effects of a specific gene variant, FTO, on obesity in adults and children. They report a fairly substantial attenuation by physical activity on the effects of this genetic variant on the risk of obesity in adults.

Abstract

Background

The FTO gene harbors the strongest known susceptibility locus for obesity. While many individual studies have suggested that physical activity (PA) may attenuate the effect of FTO on obesity risk, other studies have not been able to confirm this interaction. To confirm or refute unambiguously whether PA attenuates the association of FTO with obesity risk, we meta-analyzed data from 45 studies of adults (n = 218,166) and nine studies of children and adolescents (n = 19,268).

Methods and Findings

All studies identified to have data on the FTO rs9939609 variant (or any proxy [r 2>0.8]) and PA were invited to participate, regardless of ethnicity or age of the participants. PA was standardized by categorizing it into a dichotomous variable (physically inactive versus active) in each study. Overall, 25% of adults and 13% of children were categorized as inactive. Interaction analyses were performed within each study by including the FTO×PA interaction term in an additive model, adjusting for age and sex. Subsequently, random effects meta-analysis was used to pool the interaction terms. In adults, the minor (A−) allele of rs9939609 increased the odds of obesity by 1.23-fold/allele (95% CI 1.20–1.26), but PA attenuated this effect (p interaction = 0.001). More specifically, the minor allele of rs9939609 increased the odds of obesity less in the physically active group (odds ratio = 1.22/allele, 95% CI 1.19–1.25) than in the inactive group (odds ratio = 1.30/allele, 95% CI 1.24–1.36). No such interaction was found in children and adolescents.

Conclusions

The association of the FTO risk allele with the odds of obesity is attenuated by 27% in physically active adults, highlighting the importance of PA in particular in those genetically predisposed to obesity.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Editors’ Summary

Background

Two in three Americans are overweight, of whom half are obese, and the trend towards increasing obesity is now seen across developed and developing countries. There has long been interest in understanding the impact of genes and environment when it comes to apportioning responsibility for obesity. Carrying a change in the FTO gene is common (found in three-quarters of Europeans and North Americans) and is associated with a 20%–30% increased risk of obesity. Some overweight or obese individuals may feel that the dice are loaded and there is little point in fighting the fat; it has been reported that those made aware of their genetic susceptibility to obesity may still choose a poor diet. A similar fatalism may occur when overweight and obese people consider physical activity. But disentangling the influence of physical activity on those genetically susceptible to obesity from other factors that might impact weight is not straightforward, as it requires large sample sizes, could be subject to publication bias, and may rely on less than ideal self-reporting methods.

Why Was This Study Done?

The public health ramifications of understanding the interaction between genetic susceptibility to obesity and physical activity are considerable. Tackling the rising prevalence of obesity will inevitably include interventions principally aimed at changing dietary intake and/or increasing physical activity, but the evidence for these with regards to those genetically susceptible has been lacking to date. The authors of this paper set out to explore the interaction between the commonest genetic susceptibility trait and physical activity using a rigorous meta-analysis of a large number of studies.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find?

The authors were concerned that a meta-analysis of published studies would be limited both by the data available to them and by possible bias. Instead of this more widely used approach, they took the literature search as their starting point, identified other studies through their collaborators’ network, and then undertook a meta-analysis of all available studies using a new and standardized analysis plan. This entailed an extremely large number of authors mining their data afresh to extract the relevant data points to enable such a meta-analysis. Physical activity was identified in the original studies in many different ways, including by self-report or by using an external measure of activity or heart rate. In order to perform the meta-analysis, participants were labeled as physically active or inactive in each study. For studies that had used a continuous scale, the authors decided that the bottom 20% of the participants were inactive (10% for children and adolescents). Using data from over 218,000 adults, the authors found that carrying a copy of the susceptibility gene increased the odds of obesity by 1.23-fold. But the size of this influence was 27% less in the genetically susceptible adults who were physically active (1.22-fold) compared to those who were physically inactive (1.30-fold). In a smaller study of about 19,000 children, no such effect of physical activity was seen.

What Do these Findings Mean?

This study demonstrates that people who carry the susceptibility gene for obesity can benefit from physical activity. This should inform health care professionals and the wider public that the view of genetically determined obesity not being amenable to exercise is incorrect and should be challenged. Dissemination, implementation, and ensuring uptake of effective physical activity programs remains a challenge and deserves further consideration. That the researchers treated “physically active” as a yes/no category, and how they categorized individuals, could be criticized, but this was done for pragmatic reasons, as a variety of means of assessing physical activity were used across the studies. It is unlikely that the findings would have changed if the authors had used a different method of defining physically active. Most of the studies included in the meta-analysis looked at one time point only; information about the influence of physical activity on weight changes over time in genetically susceptible individuals is only beginning to emerge.

Additional Information

Please access these websites via the online version of this summary at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001116.

This study is further discussed in a PLoS Medicine Perspective by Lennert Veerman

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides obesity-related statistics, details of prevention programs, and an overview on public health strategy in the United States

A more worldwide view is given by the World Health Organization

The UK National Health Service website gives information on physical activity guidelines for different age groups, while similar information can also be found from US sources

Introduction

Over the past three decades, there has been a global increase in the prevalence of obesity, which has been mainly driven by changes in lifestyle [1]. However, not everyone becomes obese in today’s obesogenic environment. In fact, twin studies suggest that changes in adiposity in response to environmental influences are genetically determined [2]–[6]. Until recently, there were no confirmed obesity-susceptibility loci that could be used to test whether the influence of genetic susceptibility on obesity risk is enhanced by an unhealthy lifestyle. However, in 2007, the intron 1 of the fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene was identified as the first robust obesity-susceptibility locus in genome-wide association studies [7],[8]. Each additional minor allele of the rs9939609 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in FTO was found to be associated with a 20%–30% increase in the risk of obesity and a 1–1.5 kg increase in body weight [7],[8]. The risk-increasing allele of FTO is common, with 74% of individuals of European descent (HapMap CEU population), 76% of individuals of African-American descent (HapMap ASW population), and 28%–44% of individuals of Asian descent (HapMap CHB, CHD, GIH, and JPT populations) carrying at least one copy of the FTO risk allele.

After the discovery of FTO, several studies reported that its obesity-increasing effect may be attenuated in individuals who are physically active [9]–[20]. Other studies, however, were unable to replicate this interaction [21]–[26], leaving it unresolved whether physical activity (PA) can reduce FTO’s effect on obesity risk, and if so, to what extent. Identifying interactions between genetic variants and lifestyle is challenging as it requires much larger sample sizes than those needed for the detection of main effects of genes or environment [27]. Interaction studies are further hampered by the difficulty of measuring lifestyle exposures accurately, which reduces statistical power and necessitates large study sample sizes to offset this effect [28].

To collect a sufficiently large sample to unambiguously confirm or refute the interaction between FTO and PA, we meta-analyzed data from 45 studies, totaling 218,166 adults. In addition, we performed a similar meta-analysis among 19,268 children and adolescents from nine studies. We included all available data, both published and unpublished, and used standardized methods to analyze the interaction across the studies.

Methods

Ethics Statement

All studies were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the studies were approved by the ethics committees of the participating institutions.

Study Design

The literature on the interaction between FTO and PA is inconsistent with regard to the definitions used for PA, the statistical analysis of interactions, and the presentation of interaction results [29]. Furthermore, as statistically non-significant interactions may often not be reported, a meta-analysis of only published results would suffer from publication bias [29]. Therefore, a literature-based meta-analysis of the interaction between FTO and PA was not considered appropriate. Instead, we designed a meta-analysis based on de novo analyses of data according to a standardized plan to achieve the greatest consistency possible across studies, and to allow inclusion of all available studies, irrespective of whether they had or had not been used to examine this hypothesis in the past.

We identified all eligible studies by a PubMed literature search in December 2009 using the search term “FTO” and by following the publication history of each identified study to find those with data on PA. Furthermore, we identified all studies with genome-wide association data from published papers of genome-wide association consortia by a PubMed search using the keywords “genome-wide” and “association,” and searched the literature to determine whether these studies also had data on PA. Additional yet-unpublished studies were identified through the network of collaborators who joined the meta-analysis and were also included in the meta-analysis. Analyses according to our standardized plan were performed by each study locally, and detailed summary statistics were subsequently submitted using our standardized data collection form. Alternatively, datasets were sent to us to perform the required analyses centrally (15 studies) (Tables S1 and S2).

Quality Control

The data collection form included questions that allowed testing for internal consistency. The data were extracted automatically and cross-checked manually. The same checks for internal consistency were performed independent of whether the data were analyzed locally or centrally. All ambiguities were clarified with the respective study investigators before the final meta-analyses. A funnel plot, along with Begg and Egger tests, was used to test for the presence of “positive results bias” (i.e., to test whether studies with positive results were more likely to participate in the meta-analysis than those with negative or inconclusive results) (Figure S1).

Standardization of Physical Activity

PA was measured in various ways across the participating studies of the meta-analysis. Therefore, we standardized PA by categorizing it into a dichotomous variable (physically inactive versus active) in each study. In studies with categorical PA data, adults were defined as being “inactive” when they had a sedentary occupation and if they reported less than 1 h of moderate-to-vigorous leisure-time or commuting PA per week. In studies with continuous data on PA, adults were defined as being “inactive” when their level of PA was in the lowest sex-specific 20% of the study population concerned. All other individuals were defined as “physically active.” For children and adolescents, a more stringent cut-off for “inactivity” was chosen than for adults because of the high average PA levels in younger children [30] and the known weaker association between PA and childhood body mass index (BMI) [31]. Thus, children and adolescents were defined as being “inactive” when their level of PA was in the lowest sex- and age-specific 10% of the study population. The coding of the dichotomous PA variable in each study is described in detail in Text S1.

Genotyping

The rs9939609 SNP or a proxy (linkage disequilibrium r 2>0.8 in the corresponding ethnic group) was genotyped in each study using either direct genotyping methods or Affymetrix and Illumina genome-wide genotyping arrays (Text S1). The studies submitted only data that met their quality control criteria for genotyping call rate, concordance in duplicate samples, and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium p-value (Text S1).

Measurement of BMI, Waist Circumference, and Body Fat Percentage

BMI was calculated in each study by dividing height (in meters) by weight (in kilograms) squared. Waist circumference was measured with standard protocols and was not adjusted for height in the analyses. Body fat percentage was measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (seven studies), bioimpedance (11 studies), or the sum of skinfolds (seven studies) (Tables S3 and S4).

FTO×PA Interaction Analysis in Participating Studies

Each study tested for an effect of the FTO×PA interaction on BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage using the following additive genetic model:

| (1) |

The same model was used to test for an effect of the FTO×PA interaction on the odds of obesity (BMI≥30 versus BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI≥25 versus BMI<25 kg/m2) in adults, using normal-weight individuals as the reference group and testing for an additive effect in the “log odds” scale. In addition, each study tested the main effect of the FTO SNP on each outcome in the whole study population and in the inactive and physically active subgroups separately, using the model

| (2) |

Each study also tested the main effect of PA on each outcome, using the model

| (3) |

The interactions and associations of continuous outcome variables were analyzed with linear regression and those of dichotomous variables with logistic regression. In adults, BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage were analyzed as non-transformed variables, whereas in children, age- and sex-specific Z-scores of BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage were used.

Where data were from case-control studies for any outcome (Tables S1 and S2), cases and controls were analyzed separately. In studies with multiple ethnicities, each ethnicity was analyzed separately.

Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression

Because of heterogeneity between the studies participating in the meta-analysis, we pooled beta coefficients and standard errors for the main and interaction effects from individual studies using “DerSimonian and Laird” random effects meta-analysis, implemented by the metan command in Stata, version 11 (StataCorp). To confirm that our results were robust, we additionally pooled the interaction effects using the “Mantel and Haenszel” fixed effects method in Stata. However, as beta coefficients of fixed effects models and random effects models were the same (to two decimal points’ accuracy) for all traits, we report only the results for the random effects models. Data from adults and children were meta-analyzed separately. In all meta-analyses, between-study heterogeneity was tested by the Q statistic and quantified by the I 2 value. Low heterogeneity was defined as an I 2 value of 0%–25%, moderate heterogeneity as an I 2 of 25%–75%, and high heterogeneity as an I 2 of 75%–100% [32].

We performed a meta-regression to explore sources of heterogeneity in our meta-analysis using the metareg command in Stata. Meta-regression included the following study-specific variables as covariates: study sample size, proportion of inactive individuals, age (mean age or age group <60 y versus ≥60 y), sex (male versus female), mean BMI, study design (population- or family-based versus case-control), self-reported ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, Hispanic), geographic region (North America, Europe, Asia), and measurement of PA (1: studies with a continuous PA variable versus studies with categorical data; 2: measurement of both occupational and leisure-time PA versus leisure-time PA only; 3: measurement of PA with a questionnaire versus objective measurement).

Differences in interaction effect sizes between two subgroups were assessed with a t-test.

Results

Studies Included

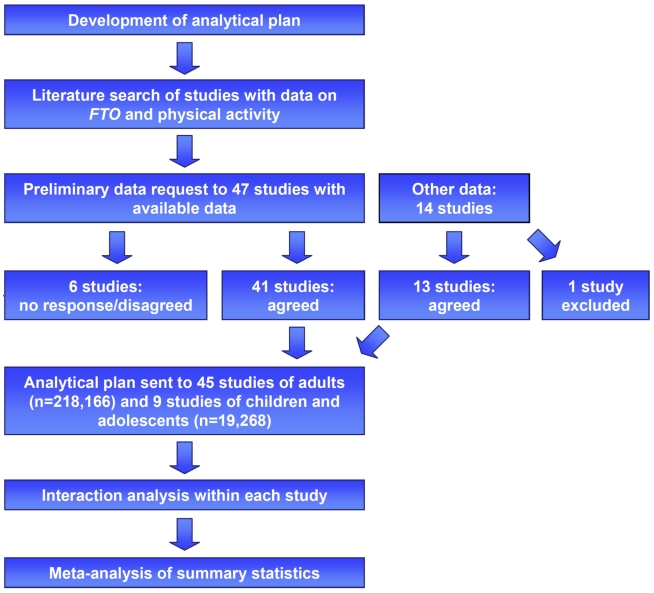

Our literature search identified 47 studies with data available on FTO and PA, of which 41 agreed to participate in our meta-analysis (Figure 1). Furthermore, 14 additional yet-unpublished studies that were identified through the network of collaborators who joined the meta-analysis were also invited to participate in the meta-analysis. We excluded one of these studies, however, because of inadequate measurement of PA. Eventually, our final meta-analysis comprised cross-sectional data on 218,166 adults (209,118 whites, 6,309 Asians, 1,770 African-Americans, and 969 Hispanics) from 45 studies, as well as data on 19,268 white children and adolescents from nine studies. Of the 45 studies of adults, 33 were from Europe, ten from North America, and two from Asia. All studies of children and adolescents were from Europe. In each study, PA was assessed using a self-report questionnaire, an accelerometer, or a heart rate sensor (Text S1).

Figure 1. Study design of the FTO×PA interaction meta-analysis.

Eligible studies were identified by a literature search, as well as through personal contacts (indicated in the figure as “other data”). Of all studies that were invited, 45 studies of adults (n = 218,166) and nine studies of children and adolescents (n = 19,268) joined the meta-analysis. A standardized analytical plan was sent to each of the studies. Summary statistics were subsequently meta-analyzed.

Association of Physical Activity with Obesity Traits (Main Effects)

Physically active adults had a 33% lower odds of obesity (p = 2×10−13), 19% lower odds of overweight (p = 7×10−9), 0.79 kg/m2 lower BMI (p = 3×10−15), 2.44 cm smaller waist circumference (p = 1×10−20), and 1.30% lower body fat percentage (p = 2×10−15) than inactive adults (Table S1). In children, PA did not have a statistically significant association with age- and sex-standardized BMI (p = 0.2), but physically active children had a waist circumference −0.11 Z-score units smaller (p = 0.04) and a body fat percentage −0.21 Z-score units lower (p = 0.02) than inactive children (Table S2).

Association of FTO with Obesity Traits (Main Effects)

In adults, each additional risk allele of the FTO rs9939609 variant increased the odds of obesity and overweight by 23% (p = 7×10−59) and 15% (p = 6×10−66), respectively (Table 1). The risk allele also increased BMI by 0.36 kg/m2 (∼1 kg in body weight for a person 170 cm tall) (p = 2×10−75), waist circumference by 0.77 cm (p = 5×10−43), and body fat percentage by 0.30% (p = 2×10−21) (Table 1).

Table 1. Association of the minor (A−) allele of the rs9939609 SNP or a proxy (r 2>0.8) in the FTO gene with BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, risk of obesity, and risk of overweight in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 218,166 adults.

| Trait | Geographic Region | N | Beta or OR1 (95% CI) | p-Value | I 2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | All individuals | 218,166 | 0.36 (0.32, 0.40) | 1.8×10−75 | 34% |

| Europe | 164,307 | 0.32 (0.29, 0.34) | 7.6×10−110 | 0% | |

| North America | 47,938 | 0.42 (0.32, 0.53) | 1.4×10−15 | 31% | |

| Asia | 5,921 | 0.59 (0.33, 0.85) | 7.9×10−6 | 39% | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | All individuals | 159,848 | 0.77 (0.66, 0.87) | 5.4×10−43 | 28% |

| Europe | 128,811 | 0.71 (0.60, 0.82) | 3.4×10−37 | 20% | |

| North America | 25,117 | 0.89 (0.60, 1.17) | 7.5×10−10 | 17% | |

| Asia | 5,920 | 1.28 (0.69, 1.86) | 1.8×10−5 | 34% | |

| Body fat percentage (%) | All individuals | 61,509 | 0.30 (0.24, 0.36) | 2.2×10−21 | 1% |

| Europe | 60,617 | 0.29 (0.23, 0.36) | 2.6×10−21 | 0% | |

| North America | 892 | 0.79 (0.12, 1.47) | 0.021 | 0% | |

| Asia | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Risk of obesity (BMI ≥30 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) | All individuals | 131,474 | 1.23 (1.20, 1.26) | 7.2×10−59 | 28% |

| Europe | 97,877 | 1.22 (1.19, 1.25) | 1.7×10−47 | 21% | |

| North America | 29,282 | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) | 3.3×10−14 | 33% | |

| Asia | 4,315 | 1.48 (1.25, 1.75) | 4.8×10−6 | 0% | |

| Risk of overweight (BMI ≥25 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) | All individuals | 213,564 | 1.15 (1.13, 1.16) | 5.5×10−66 | 10% |

| Europe | 163,069 | 1.14 (1.12, 1.16) | 5.6×10−55 | 5% | |

| North America | 44,574 | 1.14 (1.09, 1.18) | 2.4×10−10 | 21% | |

| Asia | 5,921 | 1.26 (1.14, 1.40) | 4.9×10−6 | 0% |

All models are adjusted for age and sex. Beta is the increase in trait per minor (A−) allele of rs9939609 or a proxy (r 2>0.8); I 2 is the heterogeneity between studies in the association of rs9939609 with the trait.

Values are beta for all rows except risk of obesity and risk of overweight, for which values are OR.

NA, no data available for analysis.

In children and adolescents, each FTO risk allele increased age- and sex-specific BMI by 0.10 Z-score units (p = 1×10−21), waist circumference by 0.11 Z-score units (p = 8×10−16), and body fat percentage by 0.12 Z-score units (p = 2×10−11) (Table S3).

FTO×PA Interaction and Obesity Traits

FTO×PA interaction and BMI

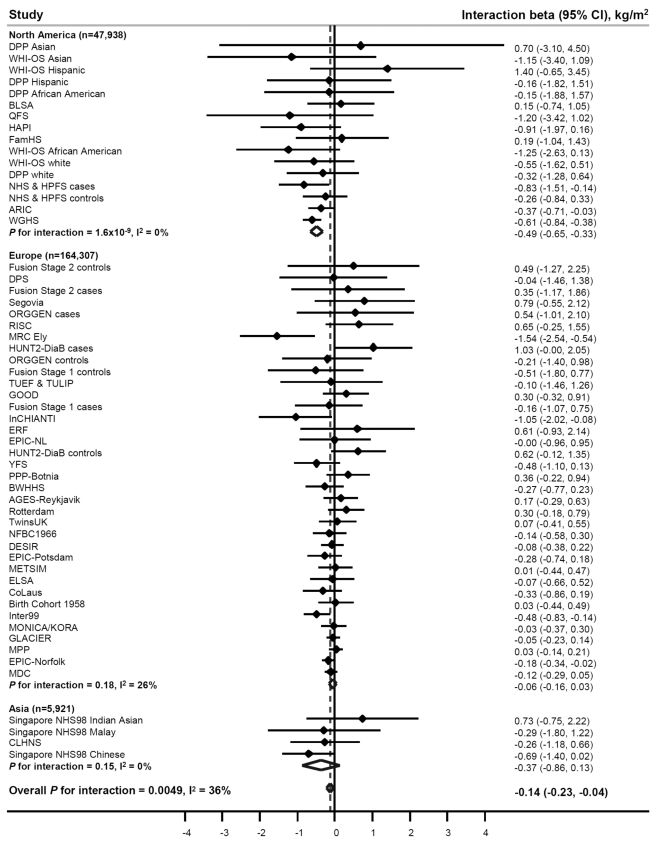

PA significantly (betainteraction = −0.14 kg/m2 per allele, p interaction = 0.005) attenuated the association between the FTO variant and BMI in our meta-analysis of 218,166 adults (Figure 2; Table 2) (i.e., a betainteraction of −0.14 kg/m2 represents the difference in the BMI-increasing effect of the risk allele between physically active and inactive individuals). The magnitude of the effect of the FTO risk allele on BMI was 30% smaller in physically active individuals (beta = 0.32 kg/m2) than in inactive individuals (beta = 0.46 kg/m2) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on BMI in a random effects meta-analysis of 218,166 adults.

The studies are sorted by sample size (largest sample size lowest). Details of the studies are given in Text S1. The interaction beta represents the difference in BMI per minor (A−) allele of rs9939609 comparing physically active individuals to inactive individuals, adjusting for age and sex. For example, a betainteraction of −0.10 kg/m2 for BMI represents a 0.10 kg/m2 attenuation in the BMI-increasing effect of the rs9939609 minor allele in physically active individuals compared to inactive individuals.

Table 2. Effect of the interaction between the rs9939609 SNP or a proxy (r 2>0.8) and PA on BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, risk of obesity, and risk of overweight in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 218,166 adults.

| Trait | Geographic Region | Main Effect of rs9939609 in Inactive Individuals | Main Effect of rs9939609 in Active Individuals | Rs9939609×PA Interaction | |||||||

| N | Beta or OR1 (95% CI) | p-Value | N | Beta or OR1 (95% CI) | p-Value | N | Betainteraction or Interaction OR1 (95% CI) | p-Value | I 2 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | All individuals | 54,611 | 0.46 (0.37, 0.55) | 3.7×10−23 | 163,555 | 0.32 (0.29, 0.36) | 4.5×10−69 | 218,166 | −0.14 (−0.23, −0.04) | 0.0049 | 36% |

| Europe | 44,052 | 0.37 (0.31, 0.44) | 1.0×10−26 | 120,255 | 0.30 (0.27, 0.34) | 2.4×10−62 | 164,307 | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.03) | 0.18 | 26% | |

| North America | 9,438 | 0.82 (0.65, 1.00) | 2.7×10−21 | 38,500 | 0.34 (0.25, 0.44) | 6.1×10−12 | 47,938 | −0.49 (−0.65, −0.33) | 1.6×10−9 | 0% | |

| Asia | 1,121 | 0.78 (0.14, 1.43) | 0.017 | 4,800 | 0.53 (0.32, 0.75) | 1.0×10−6 | 5,921 | −0.37 (−0.86, 0.13) | 0.15 | 0% | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | All individuals | 38,560 | 1.01 (0.80, 1.22) | 2.6×10−21 | 121,288 | 0.68 (0.58, 0.79) | 9.2×10−35 | 159,848 | −0.33 (−0.54, −0.12) | 0.0018 | 5% |

| Europe | 32,519 | 0.87 (0.65, 1.09) | 1.2×10−14 | 96,292 | 0.65 (0.55, 0.75) | 1.4×10−35 | 128,811 | −0.22 (−0.44, 0.00) | 0.049 | 4% | |

| North America | 4,921 | 1.72 (1.16, 2.28) | 1.4×10−9 | 20,196 | 0.65 (0.30, 1.01) | 3.2×10−4 | 25,117 | −1.02 (−1.60, −0.45) | 4.6×10−4 | 0% | |

| Asia | 1,120 | 1.65 (0.80, 1.22) | 0.029 | 4,800 | 1.12 (0.61, 1.62) | 1.5×10−5 | 5,920 | −0.84 (−2.03, 0.35) | 0.16 | 0% | |

| Body fat percentage (%) | All individuals | 11,839 | 0.44 (0.30, 0.58) | 1.0×101−9 | 49,670 | 0.28 (0.20, 0.37) | 9.4×10−12 | 61,509 | −0.19 (−0.35, −0.04) | 0.016 | 0% |

| Europe | 11,658 | 0.43 (0.29, 0.57) | 3.1×10−9 | 48,959 | 0.29 (0.20, 0.38) | 4.8×10−10 | 60,617 | −0.18 (−0.34, −0.03) | 0.023 | 0% | |

| North America | 181 | 2.03 (0.35, 3.70) | 0.018 | 711 | 0.48 (−0.26, 1.22) | 0.20 | 892 | −1.57 (−3.34, 0.20) | 0.082 | 0% | |

| Asia | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Risk of obesity (BMI ≥30 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) | All individuals | 32,774 | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.1×10−29 | 97,779 | 1.22 (1.19, 1.25) | 1.0×10−46 | 131,474 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.97) | 0.0010 | 5% |

| Europe | 26,139 | 1.27 (1.22, 1.33) | 2.9×10−29 | 71,738 | 1.21 (1.17, 1.25) | 9.1×10−35 | 97,877 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.028 | 0% | |

| North America | 5,777 | 1.43 (1.28, 1.60) | 6.0×10−10 | 23,505 | 1.22 (1.15, 1.30) | 1.0×10−9 | 29,282 | 0.85 (0.75, 0.98) | 0.024 | 24% | |

| Asia | 858 | 1.86 (1.17, 2.93) | 0.0082 | 3,457 | 1.41 (1.18, 1.70) | 1.9×10−4 | 4,315 | 0.74 (0.46, 1.20) | 0.23 | 0% | |

| Risk of overweight (BMI ≥25 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) | All individuals | 53,726 | 1.19 (1.15, 1.23) | 2.0×10−22 | 159,838 | 1.14 (1.12, 1.16) | 2.1×10−42 | 213,564 | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 0.015 | 20% |

| Europe | 43,833 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.20) | 5.8×10−26 | 119,236 | 1.14 (1.11, 1.16) | 3.2×10−29 | 163,069 | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | 0.090 | 14% | |

| North America | 8,772 | 1.24 (1.11, 1.39) | 1.8×10−4 | 35,802 | 1.13 (1.09, 1.17) | 1.0×10−12 | 44,574 | 0.89 (0.80, 0.99) | 0.034 | 21% | |

| Asia | 1,121 | 1.21 (0.79, 1.87) | 0.38 | 4,800 | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41) | 4.9×10−5 | 5,921 | 0.99 (0.67, 1.48) | 0.98 | 50% | |

All models are adjusted for age and sex. Beta is the increase in trait per minor allele of rs9939609 or a proxy (r 2>0.8); betainteraction is the difference in trait per minor allele of rs9939069 comparing physically active individuals to inactive individuals, e.g., a betainteraction of −0.14 kg/m2 for BMI represents a 0.14 kg/m2 attenuation in the BMI-increasing effect of the rs9939609 minor allele in physically active individuals compared to inactive individuals; I 2 is the heterogeneity between studies in the meta-analysis; interaction OR is the ratio of ORs (OR[physically active]/OR[inactive]) per minor allele of rs9939609, e.g., an interaction OR of 0.92 for risk of obesity indicates that the obesity-increasing effect of the rs9939609 minor allele in physically active individuals is 0.92 of the effect in inactive individuals.

Values are beta/betainteraction for all rows except risk of obesity and risk of overweight, for which values are OR/interaction OR.

NA, no data available for analysis.

To examine the sources of heterogeneity between studies, which was moderate (I 2 = 36%) (Table 2; Figure 2), we used meta-regression. The meta-regression indicated heterogeneity by geographic region (North America versus Europe) in the interaction (p = 0.001) (Tables S4 and S5). When we subsequently stratified our meta-analysis by geographic region, the attenuating effect of PA on the association between the FTO variant and BMI was more pronounced in North American populations than in European populations (p difference = 5×10−6) (Table 2; Figure 2). More specifically, the BMI-increasing effect of the FTO risk allele in physically active North Americans was 59% smaller than in inactive North Americans (beta = 0.34 versus 0.82 kg/m2, respectively), whereas the attenuation in the BMI-increasing effect of the risk allele in physically active Europeans compared with inactive Europeans was only 19% (beta = 0.30 versus 0.37 kg/m2, respectively) (Table 2). There was no heterogeneity among North American studies (I 2 = 0%), whereas moderate heterogeneity was observed among European studies (I 2 = 26%) (Table 2; Figure 2). In a further sub-group meta-regression, none of the covariates explained a significant proportion of the remaining heterogeneity observed in Europeans.

To test for the presence of “positive results bias” (i.e., whether studies with positive results were more likely to participate in our meta-analysis than those with negative or inconclusive results), we drew a funnel plot of the interaction beta coefficients and standard errors and conducted Begg and Egger tests for bias. The funnel plot was symmetrical, and the results for Begg and Egger tests were non-significant (p = 0.9 and p = 0.8, respectively), indicating that our results were not affected by positive results bias (Figure S1).

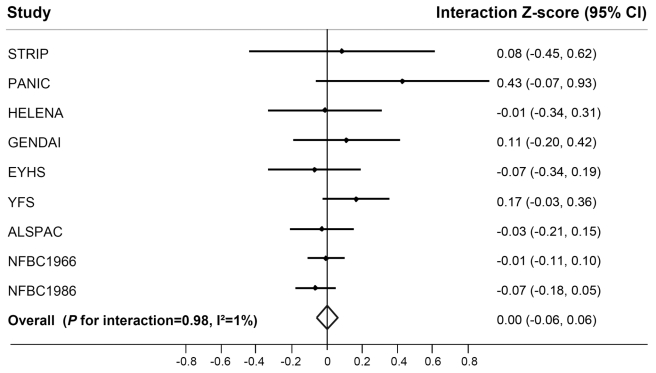

While we observed a strong effect of the FTO risk allele on BMI in children and adolescents (Table S3), this effect was not modified by their PA level (p interaction = 0.98) (Figure 3). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I 2 = 1%).

Figure 3. Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on BMI in a random effects meta-analysis of 19,268 children and adolescents.

The studies are sorted by sample size (largest sample size lowest). Details of the studies are given in Text S1. The interaction Z-score represents the difference in age- and sex-standardized BMI per minor (A−) allele of rs9939609 comparing physically active children to inactive children. For example, a betainteraction of −0.1 represents a 0.1 unit attenuation in the BMI Z-score-increasing effect of the rs9939609 minor allele in physically active children compared to inactive children.

FTO×PA interaction and risk of obesity and overweight

Consistent with the meta-analysis of BMI, PA attenuated the effect of the FTO risk allele on the odds of obesity (p interaction = 0.001) and on the odds of overweight (p interaction = 0.02) (Table 2; Figures S2 and S3). The odds of obesity for the FTO risk allele were 27% smaller (odds ratio [OR] = 1.22 versus 1.30, respectively) and the odds of overweight were 26% smaller (OR = 1.14 versus 1.19, respectively) in physically active individuals than in inactive individuals (Table 2). Similar to the results for BMI, there seemed to be a more pronounced FTO×PA interaction effect in North American populations than in Europeans: the risk-attenuating effect of PA was more than double in North Americans compared to Europeans (Table 2; Figures S2 and S3). The differences in the interaction effect between North Americans and Europeans on the odds of obesity and overweight were, however, not significant (p difference = 0.2 for both obesity and overweight).

FTO×PA interaction on waist circumference and body fat percentage

We observed a significant effect of the FTO×PA interaction on waist circumference (betainteraction = −0.33 cm, p interaction = 0.002) and body fat percentage (betainteraction = −0.19%, p interaction = 0.02) (Table 2; Figures S4 and S5). The influence of the FTO risk allele on waist circumference was 33% smaller and the influence on body fat percentage 36% smaller in physically active individuals than in inactive individuals (Table 2). Similar to the results for BMI, the effect of the FTO×PA interaction on waist circumference was also more pronounced in North American populations (betainteraction = −1.02 cm) than in Europeans (betainteraction = −0.22 cm) (p difference = 0.01) (Table 2; Figure S4). We found a similar difference for body fat percentage (betainteraction = −1.57% in North Americans versus betainteraction = −0.18% in Europeans) that, however, did not reach significance (p difference = 0.1), but few North American individuals had data on body fat percentage (n = 892) (Table 2; Figure S5).

The effect of the FTO risk allele on waist circumference and body fat percentage in children and adolescents was not modified by their PA level (p interaction = 0.7 and 0.4, respectively) (Figures S6 and S7). There was no heterogeneity between the studies in these meta-analyses (I 2 = 0%).

Association of FTO with Physical Activity

There was no association between FTO and the level of PA in adults (p = 0.2) (Figure S8) or children (p = 0.6) (Figure S9). No between-study heterogeneity was found in these meta-analyses either (I 2≤1%).

Discussion

By combining data from 218,166 adults from 45 studies, we confirm that PA attenuates the influence of FTO variation on BMI and obesity. The association of the FTO rs9939609 variant with BMI and with the odds of obesity was reduced by approximately 30% in physically active compared to inactive adults. We also found an interaction effect on the odds of overweight and on waist circumference and body fat percentage. No interaction between FTO and PA was found in our meta-analysis of 19,268 children and adolescents.

Our findings are highly relevant for public health. They emphasize that PA is a particularly effective way of controlling body weight in individuals with a genetic predisposition towards obesity and thus contrast with the determinist view held by many that genetic influences are unmodifiable. While our findings carry an important public health message for the population in general, they do not have an immediate impact at the individual level. More specifically, targeting PA interventions based on FTO genotype screening only would not accurately identify those who would benefit most of such intervention, as the effect of the FTO variant on body weight is relatively small (∼1 kg) and the attenuation of this effect by PA is limited. Of interest is that current evidence does not suggest that genetic testing would lead to an increased motivation of individuals to improve their lifestyle [33]. On the contrary, a recent study suggests that those shown to be genetically susceptible to obesity may even worsen their dietary habits [33]. Convincing evidence of gene–lifestyle interactions, however, might give people a sense of control that risk-reducing behaviors can be effective in prevention. Thus, identifying interactions between genes and lifestyle is important as it demonstrates that a genetic susceptibility to obesity is modifiable by lifestyle. Furthermore, insights from gene–lifestyle interactions contribute to elucidating the mechanisms behind genetic regulation of obesity, which may help in the development of new treatments in the future.

Interestingly, we found a geographic difference in the interaction of FTO with PA, which was consistent across the studied phenotypes. In particular, the interaction was stronger in North American populations than in populations from Europe. Reasons for the observed geographic difference are unclear. As the participating North American and European studies are mainly representative of individuals of European descent, genetic differences between them are small and unlikely to substantially contribute to the observed difference in the interaction. However, we speculate that the geographic difference may, at least in part, be related to the lower average levels of PA in individuals living in North America than in Europe [34],[35]. The FTO×PA interaction effect may materialize more in populations with a high prevalence of very sedentary individuals [17]. Furthermore, sedentariness may also associate with other lifestyle factors that may contribute to the interaction, such as unhealthy diet [16],[19],[20], which we were not able to adjust for in our meta-analyses and which may be more prevalent in North American populations than in Europeans [36]. Finally, there were differences in the measurement methods used to assess PA between North American and European studies. More specifically, all North American studies quantified PA using a continuous PA variable, whereas many European studies used categorical variables. As a result, the overall number of individuals defined as inactive was smaller in North American (20%) than in European studies (27%). We also found that PA was associated with a 1.34 kg/m2 lower BMI in North American populations, but with only a 0.72 kg/m2 lower BMI in Europeans. As misclassification in exposure measurements usually biases the effect towards the null, it is possible that lower accuracy of PA measurements in European studies may have deflated the effect of PA on BMI, as well as the interaction between FTO and PA. In our meta-regressions, however, we did not find a significant association between the measurement of PA and the observed FTO×PA interaction effect (Tables S4 and S5). Nevertheless, it is likely that our overall effect estimate for the interaction is a considerable underestimate of the true effect because of measurement error of PA.

In studies with continuous measures of PA, we chose to use a definition of “inactivity” based on a relative (lowest 20%) cut-off of PA levels. The use of a cut-off based on fixed percentage may have introduced heterogeneity as the percentage may correspond to different absolute PA values in the participating studies. However, the use of an absolute cut-off might have led to even greater heterogeneity, because of the wide differences in the measurement instruments that were used to provide the continuous measures of PA. In theory, the accuracy of a relative PA cut-off could be improved by choosing a specific cut-off for each country on the basis of national PA data. In practice, however, comparing PA data between countries is difficult, as prevalence estimates for sedentariness have been assessed by different survey instruments, which sometimes have also changed over time, and prevalence estimates are not always available from representative samples of the population.

The present meta-analysis was based on cross-sectional data and thus does not provide information on the longitudinal relationships between variables. While germline DNA remains stable throughout the life course, PA levels may change and may be confounded by other lifestyle and environmental factors that correlate with PA and body weight. So far, only three prospective follow-up studies (n range = 502 to 15,844) on the interaction between FTO and PA have been reported, and none showed an interaction between FTO and baseline PA, or change in PA, on weight change during follow-up [21]–[23]. Although studies investigating PA alone did not find an interaction, the Diabetes Prevention Program in the US showed an interaction between FTO and a 1-y lifestyle intervention, consisting of PA, diet, and weight loss combined, on change in subcutaneous fat area among 869 individuals [37]. The minor allele of the FTO variant was associated with an increase in subcutaneous fat area in the control group but not in the lifestyle intervention group [37]. Two studies have tested whether FTO modified the effect of a standardized exercise program on change in body weight in individuals who were sedentary at baseline, but results were inconsistent. While the first study showed a greater weight loss for the carriers of the major (C−) allele of FTO rs8050136 after a 20-wk endurance training program among 481 men and women [38], a subsequent study with a 6-mo endurance training program among 234 women indicated weight loss benefits for the carriers of the minor (A−) allele of the same variant [39]. These studies may have been insufficiently powered to detect an interaction between FTO variation and exercise intervention. A meta-analysis of prospective studies may be required to confirm or refute whether there is an interaction between changes in PA and FTO on weight gain in a sufficiently powered population sample. Finally, a large-scale randomized controlled trial would be needed to infer causality for the interaction between PA and FTO.

We found no interaction between the FTO variant and PA on BMI in children and adolescents, which could be because of low statistical power, as the sample size was 11 times smaller than in the meta-analysis of adults. Even so, the effect size of the interaction was null, suggesting that no attenuation of PA on the BMI-increasing effect of FTO would be found, even if a larger sample was meta-analyzed. The lack of interaction in children may, at least in part, be due to the weak association between PA and childhood BMI and the higher activity levels in children than in adults [30]. Despite the fact that BMI is a noninvasive and easy-to-obtain measure of adiposity, its weakness is that it does not distinguish lean body mass from fat mass and may therefore not be the best measure of adiposity in children. Indeed, the associations of PA with waist circumference and body fat percentage were significant, and the effect of the FTO×PA interaction on body fat percentage pointed towards a slightly decreased effect of the FTO risk allele in physically active children as compared to sedentary children.

We designed a meta-analysis based on a de novo analysis of data according to a standardized plan in all studies identified as having available data. The analytical consistency across studies, which helped minimize between-study heterogeneity, and the pooling of all identified data, which minimized biases related to study selection, are major strengths of our meta-analysis. A greater consistency and statistical power could ultimately be reached only through the establishment of large single or multicenter studies using standardized methods and precise measurement of PA.

In summary, we have established that PA attenuates the association of the FTO gene with adult BMI and obesity by approximately 30%. We have also demonstrated that large-scale international collaborations are useful for confirming interactions between genes and lifestyle.

Supporting Information

Funnel plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on BMI in a random effects meta-analysis of 45 studies (218,166 adults).

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on risk of obesity (BMI ≥30 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) in a random effects meta-analysis of 131,474 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on risk of overweight (BMI ≥25 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) in a random effects meta-analysis of 213,564 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on waist circumference in a random effects meta-analysis of 159,848 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of 61,509 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on age- and sex-standardized waist circumference in a random effects meta-analysis of 12,392 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on age- and sex-standardized body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of 6,864 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the association of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with physical activity in a random effects meta-analysis of 218,166 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the association of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with physical activity in a random effects meta-analysis of 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Association of physical activity with BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, risk of obesity, and risk of overweight in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 218,166 adults.

(PDF)

Association of physical activity with age- and sex-standardized BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Association of the minor (A−) allele of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with age- and sex-standardized BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Results of meta-regression showing the associations of all study characteristics combined with the FTO×PA interaction effect on BMI in adults.

(PDF)

Results of meta-regressions for the association of each study characteristic separately with the FTO×PA interaction effect on BMI in adults.

(PDF)

Supplementary descriptive information about the studies included in the meta-analyses.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments and funding.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The full list of Acknowledgments appears in Text S2.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- OR

odds ratio

- PA

physical activity

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

JJN has, since January 2011, been employed at Steno Diabetes Centre, a legally independent clinical and research body, which is wholly owned by Novo Nordisk. In relation to his contribution to this manuscript (through the RISC study), all of this work pre-dates his appointment to his current position. All other authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

There was no specific funding for this project/meta-analysis. Funding sources for the individual authors and for the studies included in the meta-analysis are listed in Text S2. The publication is the work of the authors, and the views in this paper are not necessarily those of any funding body. No funding body has dictated how analyses were undertaken or results interpreted, and Ruth Loos acts as guarantor for the contents.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Nadeau A, Lupien TJ, et al. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1477–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005243222101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hainer V, Stunkard AJ, Kunesova M, Parizkova J, Stich V, et al. Intrapair resemblance in very low calorie diet-induced weight loss in female obese identical twins. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mustelin L, Silventoinen K, Pietiläinen K, Rissanen A, Kaprio J. Physical activity reduces the influence of genetic effects on BMI and waist circumference: a study in young adult twins. Int J Obes. 2009;33:29–36. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCaffery JM, Papandonatos GD, Bond DS, Lyons MJ, Wing RR. Gene x environment interaction of vigorous exercise and body mass index among male Vietnam-era twins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1011–1018. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silventoinen K, Hasselbalch AL, Lallukka T, Bogl L, Pietiläinen KH, et al. Modification effects of physical activity and protein intake on heritability of body size and composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1096–1103. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreasen CH, Stender-Petersen KL, Mogensen MS, Torekov SS, Wegner L, et al. Low physical activity accentuates the effect of the FTO rs9939609 polymorphism on body fat accumulation. Diabetes. 2008;57:95–101. doi: 10.2337/db07-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cauchi S, Stutzmann F, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Durand E, Pouta A, et al. Combined effects of MC4R and FTO common genetic variants on obesity in European general populations. J Mol Med. 2009;87:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsson JA, Riserus U, Axelsson T, Lannfelt L, Schioth HB, et al. The common FTO variant rs9939609 is not associated with BMI in a longitudinal study on a cohort of Swedish men born 1920-1924. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HJ, Kim IK, Kang JH, Ahn Y, Han BG, et al. Effects of common FTO gene variants associated with BMI on dietary intake and physical activity in Koreans. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1716–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rampersaud E, Mitchell BD, Pollin TI, Fu M, Shen H, et al. Physical activity and the association of common FTO gene variants with body mass index and obesity. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1791–1797. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz JR, Labayen I, Ortega FB, Legry V, Moreno LA, et al. Attenuation of the effect of the FTO rs9939609 polymorphism on total and central body fat by physical activity in adolescents: the HELENA study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:328–333. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott RA, Bailey ME, Moran CN, Wilson RH, Fuku N, et al. FTO genotype and adiposity in children: physical activity levels influence the effect of the risk genotype in adolescent males. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1339–1343. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonestedt E, Roos C, Gullberg B, Ericson U, Wirfalt E, et al. Fat and carbohydrate intake modify the association between genetic variation in the FTO genotype and obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1418–1425. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vimaleswaran KS, Li S, Zhao JH, Luan J, Bingham SA, et al. Physical activity attenuates the body mass index-increasing influence of genetic variation in the FTO gene. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:425–428. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xi B, Shen Y, Zhang M, Liu X, Zhao X, et al. The common rs9939609 variant of the fat mass and obesity-associated gene is associated with obesity risk in children and adolescents of Beijing, China. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonestedt E, Gullberg B, Ericson U, Wirfalt E, Hedblad B, et al. Association between fat intake, physical activity and mortality depending on genetic variation in FTO. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:1041–1049. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad T, Lee IM, Pare G, Chasman DI, Rose L, et al. Lifestyle interaction with fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) genotype and risk of obesity in apparently healthy U.S. women. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:675–680. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonsson A, Renström F, Lyssenko V, Brito EC, Isomaa B, et al. Assessing the effect of interaction between an FTO variant (rs9939609) and physical activity on obesity in 15,925 Swedish and 2,511 Finnish adults. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1334–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaakinen M, Läärä E, Pouta A, Laitinen J, et al. Hartikainen Al. Life-course analysis of a fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene variant and body mass index in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 using structural equation modeling. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:653–665. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lappalainen TJ, Tolppanen AM, Kolehmainen M, Schwab U, Lindström J, et al. The common variant in the FTO gene did not modify the effect of lifestyle changes on body weight: The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Obesity. 2009;17:832–836. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liem ET, Vonk JM, Sauer PJ, van der Steege G, Oosterom E, et al. Influence of common variants near INSIG2, in FTO, and near MC4R genes on overweight and the metabolic profile in adolescence: the TRAILS (TRacking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:321–328. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Zhu H, Lagou V, Gutin B, Stallmann-Jorgensen IS, et al. FTO variant rs9939609 is associated with body mass index and waist circumference, but not with energy intake or physical activity in European- and African-American youth. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan JT, Dorajoo R, Seielstad M, Sim XL, Ong RT, et al. FTO variants are associated with obesity in the Chinese and Malay populations in Singapore. Diabetes. 2008;57:2851–2857. doi: 10.2337/db08-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith PG, Day NE. The design of case-control studies: the influence of confounding and interaction effects. Int J Epidemiol. 1984;13:356–365. doi: 10.1093/ije/13.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong MY, Day NE, Luan JA, Chan KP, Wareham NJ. The detection of gene-environment interaction for continuous traits: should we deal with measurement error by bigger studies or better measurement? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:51–57. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palla L, Higgins JP, Wareham NJ, Sharp SJ. Challenges in the use of literature-based meta-analysis to examine gene-environment interactions. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1225–1232. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekelund U, Sardinha LB, Anderssen SA, Harro M, Franks PW, et al. Associations between objectively assessed physical activity and indicators of body fatness in 9- to 10-y-old European children: a population-based study from 4 distinct regions in Europe (the European Youth Heart Study). Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:584–590. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:524–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Neilson HK, Matthews CE, Willis G, et al. Reliability and validity of the Past Year Total Physical Activity Questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:959–970. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagströmer M, Troiano RP, Sjöström M, Berrigan D. Levels and patterns of objectively assessed physical activity—a comparison between Sweden and the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell LH, Kazlauskaite R, Shima C, Appelhans BM. Lifestyle in France and the United States: an American perspective. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:845–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franks PW, Jablonski KA, Delahanty LM, McAteer JB, Kahn SE, et al. Assessing gene-treatment interactions at the FTO and INSIG2 loci on obesity-related traits in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2214–2223. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1158-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rankinen T, Rice T, Teran-Garcia M, Rao DC, Bouchard C. FTO genotype is associated with exercise training-induced changes in body composition. Obesity. 2010;18:322–326. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell JA, Church TS, Rankinen T, Earnest CP, Sui X, et al. FTO genotype and the weight loss benefits of moderate intensity exercise. Obesity. 2010;18:641–643. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Funnel plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on BMI in a random effects meta-analysis of 45 studies (218,166 adults).

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on risk of obesity (BMI ≥30 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) in a random effects meta-analysis of 131,474 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on risk of overweight (BMI ≥25 versus BMI <25 kg/m2) in a random effects meta-analysis of 213,564 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on waist circumference in a random effects meta-analysis of 159,848 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of 61,509 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on age- and sex-standardized waist circumference in a random effects meta-analysis of 12,392 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the effect of the interaction between the FTO rs9939609 SNP and physical activity on age- and sex-standardized body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of 6,864 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the association of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with physical activity in a random effects meta-analysis of 218,166 adults.

(PDF)

Forest plot of the association of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with physical activity in a random effects meta-analysis of 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Association of physical activity with BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, risk of obesity, and risk of overweight in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 218,166 adults.

(PDF)

Association of physical activity with age- and sex-standardized BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Association of the minor (A−) allele of the FTO rs9939609 SNP with age- and sex-standardized BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage in a random effects meta-analysis of up to 19,268 children and adolescents.

(PDF)

Results of meta-regression showing the associations of all study characteristics combined with the FTO×PA interaction effect on BMI in adults.

(PDF)

Results of meta-regressions for the association of each study characteristic separately with the FTO×PA interaction effect on BMI in adults.

(PDF)

Supplementary descriptive information about the studies included in the meta-analyses.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments and funding.

(PDF)