Background: Phosphoethanolamine methyltransferases (PMT) are required for growth and development of nematodes.

Result: Biochemical studies of two PMT from a parasitic nematode reveal key similarities and differences.

Conclusion: Although the nematode PMT are conserved, the domains that catalyze specific reactions may undergo different conformational changes upon ligand binding.

Significance: Because the PMT are not found in mammals, these proteins are potential antiparasitic targets for human and veterinary medicine.

Keywords: C. elegans, Enzyme Inhibitors, Enzymes, Parasite, Parasite Metabolism, S-Adenosylmethionine, Methylation, nematode, Phosphocholine

Abstract

Nematodes are a major cause of disease and the discovery of new pathways not found in hosts is critical for development of therapeutic targets. Previous studies suggest that Caenorhabditis elegans synthesizes phosphocholine via two S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-dependent phosphoethanolamine methyltransferases (PMT). Here we examine two PMT from the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Sequence analysis suggests that HcPMT1 contains a methyltransferase domain in the N-terminal half of the protein and that HcPMT2 encodes a C-terminal methyltransferase domain, as in the C. elegans proteins. Kinetic analysis demonstrates that HcPMT1 catalyzes the conversion of phosphoethanolamine to phosphomonomethylethanolamine (pMME) and that HcPMT2 methylates pMME to phosphodimethylethanolamine (pDME) and pDME to phosphocholine. The IC50 values for miltefosine, sinefungin, amodiaquine, diphenhydramine, and tacrine suggest differences in the active sites of these two enzymes. To examine the interaction of AdoMet and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoCys), isothermal titration calorimetry confirmed the presence of a single binding site in each enzyme. Binding of AdoMet and AdoCys is tight (Kd ∼2–25 μm) over a range of temperatures (5–25 °C) and NaCl concentrations (0.05–0.5 m). Heat capacity changes for AdoMet and AdoCys binding suggests that each HcPMT differs in interaction surface area. Nonlinear van't Hoff plots also indicate a possible conformational change upon AdoMet/AdoCys binding. Functional analysis of the PMT from a parasitic nematode provides new insights on inhibitor and AdoMet/AdoCys binding to these enzymes.

Introduction

In animals, the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine typically occurs either through the de novo choline (or Kennedy) pathway that converts phosphocholine into the phospholipid or by methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine to phosphatidylcholine by the Bremer-Greenberg pathway (1, 2). These pathways allow for the use of exogenous choline and other phospholipids to be used for the synthesis of the major membrane phospholipid. In contrast, plants endogenously synthesize phosphocholine (pCho)2 via the sequential methylation of phosphoethanolamine (pEA) in the phosphobase methylation pathway (3–8). Interestingly, the plant-like phosphobase methylation pathway is also found in the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which causes malaria (9–14).

In the phosphobase methylation pathway, the conversion of pEA to pCho is performed by phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase (PMT; Fig. 1A) (3–14). Although the PMT found in plants, nematodes, and protozoans all catalyze the S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-dependent methylation of pEA to pCho, the physical organization of the methyltransferase domains in these enzymes from plants (type 1), protozoa (type 2), and nematodes (type 3) differs dramatically (Fig. 1B). The plant PMT contain tandem methyltransferase domains in a single polypeptide, in which the N-terminal domain catalyzes the initial methylation of pEA to phosphomonomethylethanolamine (pMME) and the C-terminal domain catalyzes the methylations of pMME to phosphodimethylethanolamine (pDME) and pDME to pCho (7, 8). The PMT from P. falciparum is half the length of the plant enzyme and consists of a single methyltransferase domain that methylates all three phosphobases (13–14).

FIGURE 1.

PMT overview. A, the three methylation reactions in the phosphobase methylation pathway found in plants, nematodes, and Plasmodium. B, methyltransferase domain organization in the type 1 (plant), type 2 (Plasmodium), and type 3 (nematode) PMT. MT-1 catalyzes conversion of pEA to pMME and MT-2 methylates pMME to pDME and pDME to pCho. SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine.

Analysis of the PMT from C. elegans revealed a third domain organization of the methyltransferase active sites. In C. elegans, two genes encode for PMT that are similar in size to the plant enzymes but contain either the N-terminal methyltransferase domain (CePMT1) or the C-terminal methyltransferase domain (CePMT2) (9, 10). CePMT1 only catalyzes the conversion of pEA to pMME (10) and CePMT2 methylates pMME to pDME and pDME to pCho (9). Sequence examination of the genomes from multiple parasitic nematodes of humans, including Ascaris lumbricoides (intestinal roundworm), Trichuris trichiura (whipworm), Necator americanus (hookworm) and Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworm), livestock, including Ascaris suum, Strongyloides stercoralis, Haemonchus contortus, and Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and plants, such as Meloidogyne javanica, M. chitwoodi, M. incognita, Globodera rostochiensis, and Heterodera glycines, indicate that all these organisms encode type 3 PMT sharing greater than 40% amino acid sequence identity with either CePMT1 or CePMT2. Because the PMT are not found in humans or other mammals and are essential for normal growth and development of C. elegans and Plasmodium (9–14), these proteins are potential targets for the development of antiparasitic compounds for medical and veterinary use.

To determine whether the PMT from a parasitic nematode share the same domain organization and biochemical reaction specificity as the enzymes from C. elegans, we have cloned the two PMT (HcPMT1 and HcPMT2) from the sheep parasite H. contortus (sheep barber pole worm). Grazing sheep and goats consume infective larvae of H. contortus, and other gastrointestinal nematodes of the trichostrongylid family, which is a major cause of livestock disease and economic losses worldwide (15–17). Kinetic analysis demonstrates that the division of biochemical function observed in C. elegans also occurs in this parasite with HcPMT1 converting pEA to pMME and HcPMT2 methylating pMME to pDME and pDME to pCho. Because the two HcPMT were more stable than the previously characterized CePMT, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to elucidate the energetic basis of AdoMet and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoCys) interaction with the nematode PMT and to demonstrate that only a single methyltransferase domain is functional in each of the type 3 PMT. Comparison of the van't Hoff plots for the HcPMT suggests a possible conformation change occurs during AdoMet/AdoCys binding and that the binding site differs in each enzyme. Overall, thermodynamic analysis of ligand binding in the plant-like PMT from a parasitic nematode provides new insight on the functional properties of these enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The Escherichia coli Rosetta II(DE3) pLysS cells and BL21(DE3) pLysS cells were from Novagen and Stratagene, respectively. Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose resin was purchased from Qiagen. The Superdex-200 16/60 size exclusion FPLC column was from Amersham Biosciences. Radiolabeled [methyl-14C]AdoMet (55.8 mCi/mmol) was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. The pMME and pDME substrates were synthesized by Gateway Chemical. Kanamycin and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside were from Research Products International. All other reagents were from Sigma.

Cloning of hcpmt1

Partial sequence data for hcpmt1 was obtained from a H. contortus expressed sequence tag (EST; GenBankTM 27590930), which includes the nucleotide sequence for codons 3–86. The available sequence lacked the first 2 codons and the last 374 codons of hcpmt1, as well as the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR). To obtain the 5′ sequence of the hcpmt1 gene, rapid amplification of 5′ complementary DNA ends (5′-RACE) and splice leader sequence 2 PCR was performed using first strand cDNA from H. contortus as a template (18). The first strand cDNA was PCR amplified using a gene-specific primer (5′-dGCTAGCACAGTAGTGAAGC-3′) designed from the known EST sequence that anneals to a site located within the cDNA and splice leader sequence 2 primer (5′-dGGTTTTAACCCAGTATCTCAAG-3′), which is homologous to the 5′-end of H. contortus cDNAs (18). Amplified PCR products were then cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen) for DNA sequence analysis. The obtained clone contains codons 1–55 in addition to 5′-UTR. To obtain the 3′-sequence of hcpmt1, 3′-RACE was used. The first strand cDNA was directly amplified by PCR using a gene-specific primer (5′-dGAAACTGCTCGATGGGTTC-3′) and the abridged universal adapter primer (Invitrogen) (5′-dGGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC-3′). This procedure yielded a clone containing codons 79–460 in addition to 3′-UTR. These two clones, along with the known EST, comprise the complete open reading frame of the hcpmt1 gene (GenBankTM DD357247.1). Using the known 5′- and 3′-ends of the above sequences, primers were made to bridge the two fragments together and add the necessary restriction sites: primer 1, 5′-dGAAGATTCATATGACGGCTGAGGTGCG-3′ (NdeI site underlined; start codon in bold) and primer 2, 5′-dGATTCGAGCTCTTAAAGTGAAGCCTTGATCAGTAG-3′ (SacI site underlined; stop codon in bold). The PCR was carried out using Expand High Fidelity PCR polymerase (Roche Applied Science) and cloned into pCRII-TOPO for sequencing. After sequencing of the new construct, the coding region was digested with NdeI and SacI, and then ligated into pET-28a (Novagen) using a Fast-Link DNA ligase kit (Epicenter) to generate pET28a-hcpmt1.

Cloning of hcpmt2

hcpmt2 was cloned using an approach similar to that of hcpmt1. Partial sequence data were obtained from a sequencing read from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute genome of H. contortus (heme-253j23.p1k). The available sequence lacked the first 202 codons and the last 374 codons of the hcpmt2 gene, as well as each UTR. Both 5′-RACE and splice leader sequence 2 PCR were performed using first strand cDNA from H. contortus as a template. The first strand cDNA was PCR amplified using a gene-specific primer (5′-dGCTAGCACAGTAGTGAAGC-3′) and the splice leader sequence 2 primer (18). Amplified PCR products were then cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen). The resulting clone contained codons 1–202 in addition to 5′-UTR. To obtain the 3′-sequence (codons 259–432) of hcpmt2, a nested PCR primer (5′-dTTGAAACGTTTCGGACCAATGAAGACAG-3′) was designed from the 3′-sequence of the EST. The 3′-region of hcpmt2 was amplified by touchdown PCR (melting: 98 °C, 10 s; annealing: 62 to 42 °C (−1 °C/cycle) for the first 20 cycles and 42 °C for the second 20 cycles, 30 s; extension: 72 °C, 60 s) from a H. contortus cDNA using the forward nested PCR primer and the reverse oligo(dT)30 primer. The full coding region of hcpmt2 was then amplified by PCR using 5′-dCTAGCTAGCATGCCTGCCGTTGAACGACAACTGATTGAG-3′ (NheI site underlined; coding region start codon in bold) as the forward primer and 5′-dCCGGAATTCTTATTGTGGCTTGACAGCAGCGAAAAAGTT-3′ as the reverse primer (EcoRI site underlined; coding region stop codon in bold). The 1.3-kb PCR product was cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector and the sequence confirmed. Digestion of the pCRII-TOPO-hcpmt2 vector with NheI and EcoRI released the fragment for ligation into pET-28a to yield the pET28a-hcpmt2.

Protein Expression and Purification

The pET28a-hcpmt1 and pET28a-hcpmt2 expression constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS cells and RosettaII (DE3) pLysS cells, respectively. Cells were grown at 37 °C in Terrific broth containing either 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin for the BL21(DE3) cells or 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 35 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol for the RosettaII(DE3) cells until A600 nm ∼ 0.8–1.2. Following induction with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, the cultures were grown at 18 °C overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (3,000 × g; 30 min) and re-suspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 25 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 1% Tween 20). After sonication and centrifugation (11,000 × g for 30 min), the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid column previously equilibrated with lysis buffer. Wash buffer (lysis buffer minus Tween 20) was used to remove unbound proteins, and then bound protein was eluted using wash buffer containing 250 mm imidazole. Eluted protein was buffer exchanged into 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl and loaded onto a HiTrap Q-Sepharose FPLC column. A linear salt gradient (100–500 mm NaCl) was used to elute protein from the column. Fractions containing either HcPMT1 or HcPMT2 were pooled and loaded onto a Superdex-200 size exclusion FPLC column equilibrated in 25 mm Hepes (pH 7.5) and 100 mm NaCl. Fractions with purified protein were pooled, concentrated to 10 mg ml−1, and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using molar extinction coefficients for each PMT calculated using ProtParam. CePMT2 protein for ligand binding studies was prepared as previously described (9).

Enzyme Assays and Kinetic Analysis

A radiochemical assay was used to measure enzymatic activity (9, 10). Standard assay conditions for the PMT were 0.1 m Hepes·KOH (pH 8), 2 mm Na2EDTA, 10% glycerol, 2.5 mm AdoMet (100 nCi of [methyl-14C]AdoMet), and 5 mm phosphobase substrate (pEA, pMME, or pDME) in 100 μl. Reactions contained 1 μg of protein and were incubated for 2.5, 5, and 7 min at 25 °C. Protein amount and time of reaction provided a linear rate of product formation. Reactions were terminated by addition of 1 ml of ice-cold water. The phosphorylated product was purified by loading the quenched reaction to a 1-ml Dowex (50W X8–100) resin column, which was washed with 2 ml of ice-cold water and then eluted with 10 ml of 0.1 n HCl. For scintillation counting, 2 ml of the eluant was mixed with 3 ml of Ecolume scintillation fluid. Steady-state kinetic parameters for AdoMet (5–2,000 μm) were determined under standard assay conditions at 3 mm pEA or 10 mm pDME. Product formation was measured by scintillation counting. The kcat and Km values of HcPMT1 for pEA (5–2,000 μm) and HcPMT2 for pDME and pMME (5–2,000 μm) were determined at 2.0 mm AdoMet. All data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation, v = (kcat[S])/(Km + [S]), using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software). Inhibitor screens to determine IC50 values were performed using standard assay conditions with substrate concentrations of 0.25 mm AdoMet and 0.1–0.3 mm phosphobase and varied concentrations of amodiaquine (4-[(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)amino]-2-[(diethylamino)methyl]phenol), miltefosine (2-(hexadecoxy-oxido-phosphoryl)oxyethyl-trimethylazanium), sinefungin, diphenhydramine (2-(diphenylmethoxy)-N,N-dimethylethanamine), or tacrine (1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-amine).

Calorimetric Measurements

For standard ITC analysis of ligand binding, proteins were dialyzed overnight in 25 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 5% glycerol at 4 °C. Ligands (i.e. AdoMet, AdoCys, pEA, and pCho) were prepared in the same buffer. AdoMet and AdoCys concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically (A260 nm; ϵ = 15,400 m−1 cm−1) (19). ITC experiments were performed using a VP-ITC calorimeter (Microcal, Inc.). Injections (∼10 μl) of ligand were added to a sample solution containing protein using a computer-controlled 250-μl microsyringe at intervals of 5–6 min. Control experiments using buffer determined the heat of dilution for each injection, which was used as a correction in experimental titrations. Data obtained from the titrations were analyzed using a single-site binding model: Qitot = V0ΔHEtot[(KobsL)/(1 + KobsL)], in which Qitot is total heat after the ith injection, V0 is the volume of calorimetric cell, Kobs is the observed equilibrium constant, and ΔH the corresponding enthalpy change. In these equations, L and Etot are the free concentrations of the ligand and total concentration of protein, respectively, in the calorimetric cell after the ith injection. Estimates of Kobs and ΔH were obtained by fitting the experimental data using Origin software provided by the instrument manufacturer (Microcal, Inc.). Values for the change in free energy (ΔG) were calculated using ΔG = −RTln(Kobs), where R is the gas constant (1.9872 cal K−1 mol−1) and T is absolute temperature. Changes in entropy (ΔS) were calculated using ΔG = ΔH − TΔS. Kd was calculated as 1/Kobs.

RESULTS

Sequence Analysis of hcpmt1 and hcpmt2

Previous studies of the C. elegans PMT reported homologous ESTs in a wide range of parasitic nematodes of humans, livestock, and plants (9–12). To determine whether the activities of the PMT in a parasitic nematode are organized like the type 3 PMT of C. elegans, we used EST data and RACE-PCR to obtain two complete cDNAs for two putative PMT from the sheep barber pole worm H. contortus. The full-length hcpmt1 open reading frame (ORF) amplified from cDNA of H. contortus was 1,380 bp in length and encoded a 460-amino acid polypeptide (molecular mass = 53.1 kDa; pI 5.3) (supplemental Fig. S1). The hcpmt2 ORF was 1,293 bp long and encoded a 431-amino acid protein (molecular mass = 49.4 kDa; pI 5.5) (supplemental Fig. S2). The predicted amino acid sequences of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 shared only ∼6% identity to each other, but were 22 and 26% identical compared with Arabidopsis thaliana PMT2 (supplemental Fig. S3). HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 were 61 and 54% identical in amino acid sequence to their respective C. elegans homologs. As observed for the C. elegans PMT, each of the H. contortus enzymes contained the canonical sequence motifs (I-IV) for a methyltransferase domain in either the N- or C-terminal domains (20–21), but not both (Fig. S3). Homologous PMT1 and PMT2 sequences related by ∼50% sequence identity were found in the genomes of other nematodes, suggesting that the phosphobase pathway is conserved across these organisms.

Phosphobase Specificity and Inhibition of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2

Recombinant HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 were expressed in E. coli as N-terminal His6-tagged proteins and purified by nickel affinity and size exclusion chromatographies to apparent homogeneity. The molecular masses of purified recombinant His-tagged HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 as determined by SDS-PAGE were ∼55 and ∼48 kDa, respectively (supplemental Fig. S4), which corresponded to the predicted masses of the expressed proteins. Size exclusion chromatography of HcPMT1 (52.3 kDa) and HcPMT2 (51.9 kDa) indicated that each enzyme was present in solution as a monomer (supplemental Fig. S4).

To examine the substrate specificities of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2, each protein was assayed using pEA, pMME, and pDME as potential substrates for the AdoMet-dependent methylation reaction (Table 1). Steady-state kinetic assays demonstrated that HcPMT1 used only pEA as a substrate to efficiently catalyze the first reaction in the phosphobase methylation pathway. In contrast, HcPMT2 accepted both pMME and pDME, but not pEA, as substrates for the last two steps in the pathway. The substrate specificities of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 are identical to those reported previously for CePMT1 and CePMT2 (9, 10). Product inhibition for each HcPMT was also evaluated. HcPMT1 showed IC50 values for AdoCys, pDME, and pCho of 12.6 ± 0.8, 927 ± 30, and 470 ± 28 μm, respectively. Both AdoCys and pCho inhibited HcPMT2 with IC50 values of 10.2 ± 0.8 and 1,170 ± 12 μm, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for HcPMT1 and HcPMT2

Reactions were performed using a radiometric assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All kcat and Km values are expressed as a mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

| Enzyme | Substrate | kcat | Km | V/K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | μm | m−1s−1 | ||

| HcPMT1 | pEA | 518 ± 11 | 106 ± 8 | 81,447 |

| AdoMet | 349 ± 14 | 256 ± 30 | 22,721 | |

| HcPMT2 | pMME | 294 ± 7 | 424 ± 26 | 11,556 |

| pDME | 248 ± 8 | 217 ± 22 | 19,048 | |

| AdoMet | 137 ± 5 | 277 ± 32 | 8,243 |

No small molecule inhibitors have been reported for the nematode PMT; however, a limited number of inhibitors have been described for the PMT from P. falciparum, the protozoan parasite that causes malaria, including the AdoMet analog sinefungin (a nucleoside antibiotic from fungi), amodiaquine (a chloroquine-analog), and miltefosine (22). The effects of sinefungin, amodiaquine, miltefosine, diphenhydramine, and tacrine on HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 activity were evaluated (Table 2). Diphenhydramine and tacrine are histamine-N-methyltransferase inhibitors (23). Miltefosine and sinefungin were the most effective inhibitors against both enzymes, but displayed differential preferences with sinefungin 3-fold more effective versus HcPMT1 and miltefosine 10-fold more effective versus HcPMT2. Amodiaquine, diphenhydramine, and tacrine were all poor inhibitors (mm) of the HcPMT enzymes.

TABLE 2.

IC50 values for inhibitors of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2

Reactions (n = 3) were performed using a radiometric assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

ITC Analysis of AdoMet/AdoCys Binding to Nematode PMT

Sequence comparisons of the nematode PMT suggest that each enzyme contains a single functional methyltransferase domain; however, the binding stoichiometries for either AdoMet or AdoCys have not been examined for any PMT. ITC was used to investigate the protein-ligand interactions in the nematode PMT. For these experiments, HcPMT1, HcPMT2, and CePMT2 were used to evaluate AdoCys and AdoMet binding. Although CePMT1 was previously expressed and purified (10), this protein could not be sufficiently concentrated for calorimetry and was unstable in a range of buffer conditions tried for these titrations; this precluded further work with this protein. In addition, binding of pEA and pCho to the nematode PMT, which is possibly based on the random Bi Bi kinetic mechanism (9, 10), was not detectable by ITC. This result is consistent with the high Km and IC50 values determined for these molecules.

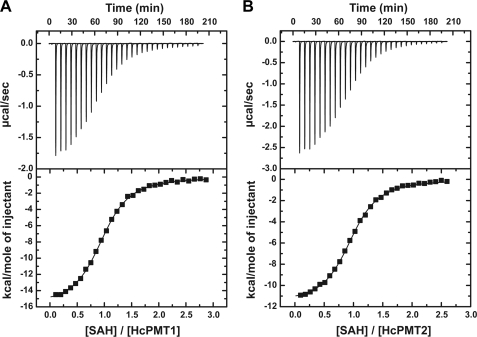

AdoCys binding could be detected and quantified for HcPMT1, HcPMT2, and CePMT2 (Table 3). Representative ITC titrations for AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 are shown in Fig. 2. For each PMT, AdoCys binding is tight (Kd ∼ 2–5 μm) with HcPMT1 showing a 2-fold lower Kd value compared with either HcPMT2 or CePMT2. The binding constants for AdoCys are similar to the IC50 values reported above for HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 and to the Kd for AdoCys binding to CePMT2 previously determined by fluorescence titration (9). AdoMet binding could be observed in all three PMT, but only accurately quantified for HcPMT1 with a Kd value 11-fold higher than AdoCys. The Kd values for AdoMet binding to HcPMT2 and CePMT2 were too high to provide sufficient heat to measure a binding isotherm. For each of the three nematode PMT, analysis of the binding curves for AdoMet and/or AdoCys indicate the presence of one binding site (Table 3), which is consistent with a single methyltransferase motif in each enzyme.

TABLE 3.

ITC analysis of AdoMet/AdoCys binding

Titrations were performed at the indicated temperature as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data were fit to a single-site binding model.

| Protein-ligand | Temperature | n | Kd | ΔG | ΔH | −TΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | μm | kcal mol−1 | ||||

| HcPMT1-AdoMet | 25 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 26.7 ± 3.8 | −6.2 ± 0.9 | −14.3 ± 1.3 | 8.1 |

| HcPMT1-AdoCys | 25 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | −7.6 ± 0.2 | −19.2 ± 0.1 | 11.5 |

| HcPMT2-AdoCys | 25 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | −7.2 ± 0.2 | −12.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 |

| CePMT2-AdoCys | 17 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 5.3 ± 0.4 | −7.0 ± 0.1 | −6.9 ± 0.1 | −0.1 |

FIGURE 2.

ITC analysis of AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 and HcPMT2. A, titration of HcPMT1 with AdoCys. The top panel shows the ITC data plotted as heat signal (μcal s−1) versus time (min). The experiment consisted of 30 injections of 10 μl of AdoCys (396 μm) into a solution containing protein (31.0 μm) at 20 °C. The botton panel shows the integrated heat response per injection from panel A plotted as normalized heat per mol of injectant. The solid line represents the fit to the data. B, titration of HcPMT2 (68.1 μm) with AdoCys (786 μm). Top and bottom panels are as described in A. SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine.

Temperature Dependence of AdoMet and AdoCys Binding to Nematode PMT

Binding isotherms were determined over a range of temperatures (5 to 25 °C) to examine the energetics of interaction between HcPMT1 and AdoMet, HcPMT1 and AdoCys, and HcPMT2 and AdoCys (Fig. 3, A-C, and Table 4). CePMT2 was not used for further analysis because of stability problems in ITC titration conditions above 17 °C. For each protein-ligand interaction, the Kd value was 2.8- to 4.3-fold tighter at 5 °C than at 25 °C with little change in the free energy of binding (ΔG) at each temperature. At each temperature, the enthalpic and entropic contributions compensate to maintain the ΔG for protein-ligand interaction. The negative enthalpy of binding indicates a favorable exothermic interaction between AdoCys with both HcPMT1 and HcPMT2. Similar results were observed with AdoMet binding to HcPMT1. At higher temperatures, the entropic contribution is more favorable. The changes in enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) are linear between 5 and 25 °C.

FIGURE 3.

Temperature dependence of thermodynamic parameters for AdoCys/AdoMet binding. The temperature dependence of ΔG (circle), ΔH (open circle), and −TΔS (square) for binding of (A) AdoMet to HcPMT1, (B) AdoCys to HcPMT1, and (C) AdoCys to HcPMT2. The ΔH values were used to calculate the change in heat capacity (ΔCp). D, van't Hoff plot of Keq versus temperature. Data are shown for HcPMT1-AdoMet (circles), HcPMT1-AdoCys (open circles), and HcPMT2-AdoCys (squares).

TABLE 4.

ITC analysis of the temperature dependence of AdoMet/AdoCys binding

Titrations were performed at the indicated temperature as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data were fit to a single-site binding model.

| Protein-ligand | Temperature | Kd | ΔG | ΔH | −TΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | μm | kcal mol−1 | |||

| HcPMT1-AdoMet | 5 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | −6.6 ± 0.6 | −4.6 ± 0.1 | −2.0 |

| 10 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | −6.6 ± 0.5 | −6.7 ± 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 15 | 11.4 ± 0.5 | −6.5 ± 0.3 | −8.9 ± 0.1 | 2.4 | |

| 20 | 16.6 ± 1.7 | −6.4 ± 0.7 | −11.1 ± 0.5 | 4.7 | |

| 25 | 26.7 ± 3.8 | −6.2 ± 0.9 | −14.3 ± 1.3 | 8.1 | |

| HcPMT1-AdoCys | 5 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | −7.9 ± 0.6 | −9.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 |

| 10 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | −7.9 ± 0.5 | −12.0 ± 0.1 | 4.1 | |

| 15 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | −7.9 ± 0.4 | −14.6 ± 0.1 | 6.7 | |

| 20 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | −7.8 ± 0.3 | −17.7 ± 0.1 | 9.9 | |

| 25 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | −7.6 ± 0.2 | −19.2 ± 0.1 | 11.5 | |

| HcPMT2-AdoCys | 5 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | −7.3 ± 0.6 | −9.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2 |

| 10 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | −7.3 ± 0.4 | −10.1 ± 0.1 | 2.8 | |

| 15 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | −7.3 ± 0.3 | −10.8 ± 0.1 | 3.5 | |

| 20 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | −7.2 ± 0.3 | −11.7 ± 0.1 | 4.5 | |

| 25 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | −7.2 ± 0.2 | −12.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 | |

To determine the change in heat capacity (ΔCp) for each protein/ligand interaction, the slope of the ΔH versus temperature plot was determined. For the HcPMT1-AdoMet, HcPMT1-AdoCys, and HcPMT2-AdoCys interactions, the ΔCp were −476, −581, and −168 kcal mol−1 K−1, respectively. The negative values suggest that ligand binding is specific and accompanied by burial of the nonpolar surface area (24–25). The difference between HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 implies structural variations between the AdoMet/AdoCys binding sites of each enzyme. Moreover, analysis of the temperature dependence of binding shows curvature in the van't Hoff plot (Fig. 3D), which suggests that AdoMet/AdoCys binding in HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 may be accompanied by possible conformational changes (26–28), as discussed later.

Ionic Dependence of AdoMet/AdoCys Binding

Although the three-dimensional structure of a PMT remains to be elucidated, the presence of conserved aspartic acids in the canonical motif has led to the suggestion that electrostatic interactions may play a key role in ligand binding (20, 21). To evaluate the potential role of ionic interactions, the effect of NaCl on AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 and AdoMet binding to HcPMT1 was examined (Fig. 4 and Table 5). For AdoCys binding to each protein, there is a modest 2–3-fold variation in binding affinity from 0.05 to 0.5 m NaCl. These small differences suggest that electrostatic interactions are not a driving force for binding of AdoCys. Similar results were obtained for binding of AdoMet to HcPMT1.

FIGURE 4.

Ionic dependence of AdoCys/AdoMet binding. Effect of NaCl concentration on Kd for the binding of AdoMet to HcPMT1 (circles), AdoCys to HcPMT1 (open circles), and AdoCys to HcPMT2 (squares).

TABLE 5.

ITC analysis of the ionic dependence of AdoMet/AdoCys binding

Titrations were performed at the indicated temperature as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data were fit to a single-site binding model.

| Protein-Ligand | NaCl | Kd | ΔG | ΔH | −TΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | μm | kcal mol−1 | |||

| HcPMT1-AdoMet | 0.05 | 47.2 ± 5.3 | −5.8 ± 0.7 | −15.1 ± 1.7 | 9.3 |

| 0.10 | 19.1 ± 0.9 | −6.3 ± 0.3 | −12.5 ± 0.3 | 6.2 | |

| 0.30 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | −6.7 ± 0.3 | −13.6 ± 0.2 | 6.9 | |

| 0.50 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | −7.0 ± 0.3 | −12.7 ± 0.2 | 5.6 | |

| HcPMT1-AdoCys | 0.05 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | −7.4 ± 0.2 | −15.2 ± 0.1 | 7.8 |

| 0.10 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | −7.6 ± 0.2 | −15.9 ± 0.1 | 8.3 | |

| 0.30 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | −7.9 ± 0.1 | −17.8 ± 0.0 | 9.9 | |

| 0.50 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | −8.1 ± 0.4 | −9.8 ± 0.1 | 9.8 | |

| HcPMT2-AdoCys | 0.05 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | −6.8 ± 1.0 | −16.5 ± 1.5 | 9.7 |

| 0.10 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | −7.0 ± 0.7 | −11.9 ± 0.3 | 4.9 | |

| 0.30 | 9.3 ± 1.1 | −6.8 ± 0.8 | −12.4 ± 0.8 | 5.7 | |

| 0.50 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | −7.0 ± 2.1 | −6.7 ± 0.7 | −0.3 | |

DISCUSSION

The PMT of the phosphobase methylation pathway catalyze formation of pCho in plants, nematodes, and protozoan parasites (6–14), but the molecular basis for the organization of the methyltransferase domains and their active sites remains poorly understood. For example, the inference of a single AdoMet/AdoCys binding site in the two PMT from C. elegans is based solely on analysis of consensus sequence motifs for methyltransferase domains (9, 10). Moreover, the differences between the vestigial and functional methyltransferase domains and between active sites with different specificity (pEA versus pMME and pDME) in the PMT are not clear. To establish that the predicted methyltransferase domain organization and reaction specificities observed in the free-living nematode C. elegans are conserved across the nematode PMT, we biochemically examined two PMT from H. contortus, a parasitic nematode that causes significant livestock losses worldwide (15–17).

Comparison of the amino acid sequences (supplemental Fig. S3) and kinetic properties (Table 1) of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 to the homologs from C. elegans confirms that the divided functionality of these enzymes is retained. Given the ∼50% amino acid sequence identity between PMT1 and PMT2 found in various free-living and parasitic nematodes, the domain organization and reaction specificity of the two enzymes appears to be maintained across these widely divergent organisms (29). This separation of function dates back to the pre-Cambrian era of more than 500 million years ago when the phylum nematoda was established (30, 31). Although the PMT are essential for normal growth and development of C. elegans (9–12), a similar role for the phosphobase methylation pathway in parasitic nematodes of humans, animals, and plants remains to be established, but the conservation of the PMT across these organisms suggests a conserved role for this metabolic pathway.

Biochemically, the kinetic analysis of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 provides a functional parallel with the PMT from C. elegans, in which the N-terminal domain of PMT1 converts pEA to pMME and the C-terminal domain of PMT2 methylates pMME to pDME and pDME to pCho (Table 1). Calorimetric analysis of AdoMet/AdoCys binding to HcPMT1, HcPMT2, and CePMT2 demonstrates the presence of a single ligand binding site in each enzyme (Fig. 2 and Table 3), which suggests that the vestigial domains of the nematode PMT do not bind either AdoMet or AdoCys. As observed with most methyltransferases (31, 32), AdoCys is an effective feedback inhibitor of HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 and binds 10-fold tighter than AdoMet in the HcPMT1 active site (Table 3).

Because the PMT are found in parasitic nematodes and protozoans, the inhibition of these enzymes may provide a route for the development of anti-parasitic therapeutics (11–12, 22). Because sinefungin, amodiaquine, and miltefosine are inhibitors of the PMT from the malaria parasite P. falciparum (13, 22), the effects of these molecules, along with diphenhydramine and tacrine, on the nematode PMT were evaluated (Table 2). Except for sinefungin and miltefosine, none of these molecules are potent inhibitors of either HcPMT1 or HcPMT2. The HcPMT IC50 values for sinefungin and miltefosine are comparable with those determined for the Plasmodium enzyme (∼50 μm for each compound) (13, 22), which suggest possible conserved binding interactions. Amodiaquine inhibits the Plasmodium enzyme with an IC50 ∼ 5 μm (22), but amodiaquine, diphenhydramine, and tacrine all bind histamine methyltransferase with nanomolar inhibition constants (23). Although these compounds are poor inhibitors of the HcPMT, comparison with their effects on the Plasmodium PMT and histamine methyltransferase suggest that identification of methyltransferase-specific inhibitors is possible. Moreover, it is likely that high-throughput screening of compounds against the PMT from parasitic nematodes and protozoans may lead to the identification of potential lead compounds for further investigation (34–36).

Thermodynamic analysis of AdoMet and AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 provides new insights on the association of these ligands with the PMT. Comparison of AdoMet versus AdoCys binding in HcPMT1 reveals a modest 1.4 kcal mol−1 difference in the free energy of binding between these two ligands with enthalpic and entropic contributions that differ (Table 3). Although the sulfonium ion of AdoMet destabilizes the molecule by 13 kcal mol−1 in the chemical reaction to provide a highly reactive substrate (33, 37), ITC analysis of HcPMT1 indicates that the charge state of AdoMet versus AdoCys does not drastically alter the free energy of binding. Detailed comparison of the temperature dependence of AdoMet and AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 (Fig. 3, A and B, and Table 4) also shows that the enthalpic and entropic contributions for interaction of either molecule to the protein at temperatures from 5 to 25 °C are similar. Likewise, there is a modest 2–3-fold difference in the Kd values for binding of either AdoMet or AdoCys to HcPMT1 from 0.05 to 0.5 m NaCl (Fig. 4 and Table 5), but this effect does not support a role for electrostatic interactions as a driving force in protein-ligand interaction in the PMT.

As observed with the kinetic and inhibitor studies, thermodynamic analysis of AdoCys binding to HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 also suggests that the active sites of these two enzymes differ, even though they bind AdoMet/AdoCys and chemically similar phosphobase substrates. Data obtained by ITC shows that the thermodynamic parameters for AdoMet and AdoCys binding to each HcPMT display similar trends (Fig. 3, A–C); however, the slopes of the enthalpic and entropic changes differ between the two proteins. Based on sequence and the biological role of the PMT, conservation of the AdoMet/AdoCys binding site should lead to similar overall thermodynamic properties with variations arising from structural differences. This is highlighted by comparing the changes in heat capacity (ΔCp) for HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 (Fig. 3D). The ΔCp values for AdoMet (ΔCp = −476 kcal mol−1 K−1) and AdoCys (ΔCp = −581 kcal mol−1 K−1) to HcPMT1 were greater than that for AdoCys binding to HcPMT2 (ΔCp = −168 kcal mol−1 K−1). These values indicate that ligand binding results in the burial of different amounts of nonpolar surface area in each protein (24, 25). Moreover, analysis of the temperature dependence of binding shows a curvature in the van't Hoff plot (Fig. 3D), which suggests that AdoMet/AdoCys binding in HcPMT1 and HcPMT2 may result in conformational changes (26–28).

Although no structural information is available for a PMT from nematodes, plants, or Plasmodium, conformational changes have been observed in other small molecule methyltransferases. For example, glycine methyltransferase, which is a tetrameric enzyme, undergoes cooperative changes in each monomer upon AdoMet binding (38, 39). Likewise, the crystal structures of the guanidoacetate-, phenylethanolamine-, and histamine-N-methyltransferases reveal that different parts of their respective N-terminal regions act as a lid domain that shifts into the active site upon binding of either AdoMet or AdoCys binding (40–42). If analogous structural changes occur in the nematode PMT1 and PMT2, the location of a functional methyltransferase domain in either the N- or C-terminal half of each protein may affect the mobility of any potential active site lid region. Conformational changes in a lid domain may be more restricted in HcPMT2 compared with a less constrained placement at the N-terminal of HcPMT1. This may account for the observed differences in thermodynamic properties with varied temperature and heat capacity changes between HcPMT1 and HcPMT2.

Crystallographic studies of the PMT from plants, nematodes, and protozoans are required to reveal the molecular details of how these enzymes function by providing insight on the organization of their active sites, reaction chemistry, and the determinants of substrate specificity. Because the PMT play an important role in maintaining normal growth and development in nematodes and Plasmodium (the causative agent of malaria) and are not found in mammals (9–14, 22), these enzymes are potential targets for inhibitors that may have value as anti-parasitics for human and/or animal medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Xuemin (Sam) Wang at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center for generous access to the calorimeter in his laboratory.

This work was supported by United States Environmental Protection Agency Grant X-83228201 (to J. P. M., D. J. W., M. C. H., and J. M. J.) and Department of Agriculture Grant 2005-33610-16465 (to M. C. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- pCho

- phosphocholine

- EST

- expressed sequence tag

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- pDME

- phosphodimethylethanolamine

- pEA

- phosphoethanolamine

- pMME

- phosphomonomethylethanolamine

- PMT

- phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase

- RACE

- rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends

- AdoHcy

- S-adenosylhomocysteine

- AdoMet

- S-adenosylmethionine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (1989) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58, 635–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kent C. (1995) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 314–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mudd S. H., Datko A. H. (1986) Plant Physiol. 82, 126–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Datko A. H., Mudd S. H. (1988) Plant Physiol. 88, 854–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Datko A. H., Mudd S. H. (1988) Plant Physiol. 88, 1338–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolognese C. P., McGraw P. (2000) Plant Physiol. 124, 1800–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nuccio M. L., Ziemak M. J., Henry S. A., Weretilnyk E. A., Hanson A. D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14095–14101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charron J. B., Breton G., Danyluk J., Muzac I., Ibrahim R. K., Sarhan F. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 363–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palavalli L. H., Brendza K. M., Haakenson W., Cahoon R. E., McLaird M., Hicks L. M., McCarter J. P., Williams D. J., Hresko M. C., Jez J. M. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6056–6065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brendza K. M., Haakenson W., Cahoon R. E., Hicks L. M., Palavalli L. H., Chiapelli B. J., McLaird M., McCarter J. P., Williams D. J., Hresko M. C., Jez J. M. (2007) Biochem. J. 404, 439–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jez J. M. (2007) Curr. Enz. Inhib. 3, 133–142 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee S. G., Jez J. M. (2011) Curr. Chem. Biol. 5, 183–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pessi G., Kociubinski G., Mamoun C. B. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6206–6211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pessi G., Choi J. Y., Reynolds J. M., Voelker D. R., Mamoun C. B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12461–12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grenfell B. T. (1988) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 321, 541–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilleard J. S. (2006) Int. J. Parasitol. 36, 1227–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zajac A. M. (2006) Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 22, 529–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Redmond D. L., Knox D. P. (2001) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 117, 107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Montange R. K., Mondragón E., van Tyne D., Garst A. D., Ceres P., Batey R. T. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 396, 761–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kagan R. M., Clarke S. (1994) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 310, 417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng X., Roberts R. J. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3784–3795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bobenchik A. M., Choi J. Y., Mishra A., Rujan I. N., Hao B., Voelker D. R., Hoch J. C., Mamoun C. B. (2010) BMC Biochem. 11, 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horton J. R., Sawada K., Nishibori M., Cheng X. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 353, 334–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spolar R. S., Record M. T., Jr. (1994) Science 263, 777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Brien R., DeDecker B., Fleming K. G., Sigler P. B., Ladbury J. E. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 279, 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horn J. R., Brandts J. F., Murphy K. P. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 7501–7507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumaran S., Grucza R. A., Waksman G. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14828–14833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumaran S., Jez J. M. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 5586–5594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blaxter M. L., De Ley P., Garey J. R., Liu L. X., Scheldeman P., Vierstraete A., Vanfleteren J. R., Mackey L. Y., Dorris M., Frisse L. M., Vida J. T., Thomas W. K. (1998) Nature 392, 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ridley M. (2004) Evolution, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aguinaldo A. M., Turbeville J. M., Linford L. S., Rivera M. C., Garey J. R., Raff R. A., Lake J. A. (1997) Nature 387, 489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cantoni G. L. (1975) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 44, 435–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schubert H. L., Blumenthal R. M., Cheng X. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 329–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Renslo A. R., McKerrow J. H. (2006) Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 701–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaletta T., Hengartner M. O. (2006) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hunter W. N. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11749–11753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walsh C. T. (1979) Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms, W. H. Freeman and Company, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fu Z., Hu Y., Konishi K., Takata Y., Ogawa H., Gomi T., Fujioka M., Takusagawa F. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 11985–11993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takata Y., Huang Y., Komoto J., Yamada T., Konishi K., Ogawa H., Gomi T., Fujioka M., Takusagawa F. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 8394–8402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Komoto J., Huang Y., Takata Y., Yamada T., Konishi K., Ogawa H., Gomi T., Fujioka M., Takusagawa F. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 320, 223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu Q., Gee C. L., Lin F., Tyndall J. D., Martin J. L., Grunewald G. L., McLeish M. J. (2005) J. Med. Chem. 48, 7243–7252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horton J. R., Sawada K., Nishibori M., Zhang X., Cheng X. (2001) Structure 9, 837–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.