Abstract

Social scientists do not agree on the size and nature of the causal impacts of parental income on children's achievement. We revisit this issue using a set of welfare and antipoverty experiments conducted in the 1990s. We utilize an instrumental variables strategy to leverage the variation in income and achievement that arises from random assignment to the treatment group to estimate the causal effect of income on child achievement. Our estimates suggest that a $1,000 increase in annual income increases young children's achievement by 5%–6% of a standard deviation. As such, our results suggest that family income has a policy-relevant, positive impact on the eventual school achievement of preschool children.

Keywords: income, child achievement, causal estimates

Despite countless studies estimating the association between family income and child development, there is still a lively debate about how, and even whether, a policy-induced increase in family income would be spent in ways that would boost the achievement of children (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Magnuson & Votruba-Drzal, 2009; Mayer, 1997, 2002). The estimation problem is a familiar one: Most studies of income effects are based on nonexperimental data and are susceptible to biases from unmeasured parent and family characteristics, as well as from bidirectional influences of children on their parents. Yet, understanding how much, if any, of the association between parents’ income and children's achievement is causal is critical to advancing developmental theory as well as improving our understanding about whether interventions designed to increase income are likely to promote children's academic achievement (Gennetian, Magnuson, & Morris, 2008).

We contribute to this field of study using data from 16 implementations of welfare-to-work experiments, all of which assigned low-income and welfare-recipient single parents at random to control groups or to various welfare and employment policy treatments. All policy treatments had components designed to increase employment and reduce welfare; some, but not all, were designed to increase parents’ income as well. We use the exogenous variation in family income generated by random assignment (as well as the variation across the experimental treatment sites) to identify the effects of income on the achievement of young children. In doing so, we contribute to prior research to generate an estimate for the effect of income on young children's achievement as they enter the elementary school years.

Background Research on Poverty and Children's Development

Extensive literature examining the relation between family economic resources and children's developmental outcomes has developed in economics, developmental psychology, and sociology; most researchers now offer integrated theoretical models across disciplines. In psychology, building from Glen Elder's seminal work on families during the Great Depression (Elder, 1974, 1979; Elder, Liker, & Cross, 1984), researchers have theorized that income may affect parental stress and thereby change the consistency and harshness of the parent–child relationship, in turn affecting children's outcomes (McLoyd, 1990; McLoyd, Jayartne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994). More recent work by Evans and colleagues (Evans & English, 2002; Evans, Gonella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005) has argued that poverty contributes to a context of chaos that impinges on children's physiology, resulting in the cost of making long-term adaptive shifts across a broad range of biological systems to meet environmental demands (allostatic load; Ganzel, Morris, & Wethington, 2010; McEwen & Stellar, 1993). In economics, a household production model posits that child outcomes are the product of the amount and quality of parental time inputs, the amount and quality of other caretakers’ time, and market goods spent on behalf of children (Becker, 1965; Desai, Chase-Landsdale, & Michael, 1989). Income matters in this model because it enables parents to purchase inputs that matter for the production of positive child outcomes.

Numerous nonexperimental studies show that family income has positive associations with outcomes for children, although sometimes more so for cognitive outcomes than for child behavior and health (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Haveman & Wolfe, 1995). Moreover, the income associations appear to differ across the childhood age span. Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, Yeung, and Smith (1998) found that family economic conditions experienced before the age of 5 years are more strongly associated with children's completed schooling than are economic conditions from ages 6–15. Duncan, Ziol-Guest, and Kalil (2010) showed the same patterns for the prediction of adult earnings and work hours. Votruba-Drzal (2006) used change models and found that early childhood income (but not middle childhood income) has positive, but small, associations with academic outcomes, although income in both periods is associated with behavior.

Results regarding the stronger effects of income in early childhood are consistent with theoretical predictions about the developmental malleability of preschool children (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000); about the susceptibility of the early childhood period to family influences, compared with schools, neighborhoods, and peer influences (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998, 2006; McCall, 1981); and about the notion that early skills provide a key foundation for later skill acquisition (Heckman, 2006).

Furthermore, the literature has suggested that changes in income have stronger associations with outcomes for children in low-income compared with higher income families (Alderson, Gennetian, Dowsett, Imes, & Huston, 2008; Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2006; Duncan et al., 2010). This is to be expected because income increases at the low end of the distribution represent larger proportional increases in total family income and are more likely to reduce material deprivation and stress.

Striving for causal effect estimates rather than mere association is critical for both developmental theory and policy. However, securing causal effects is difficult, particularly when using nonexperimental data. Because poverty is associated with other experiences of disadvantage, it is difficult to determine whether it is poverty per se that really matters or, instead, other related experiences, for example, a low level of maternal education or being raised in a single-parent family. Moreover, because income is endogenously determined by the individuals and families under study, association between income and outcomes for children may reflect reversed causation, with children's outcomes affecting parents’ income (see Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002, for a discussion of limitations of nonexperimental research). These biases are worrisome because they may lead to erroneous conclusions regarding causal effects. As such, determining the extent of causal effect is critical for the advancement of theory and the design of effective interventions.

The only large-scale randomized interventions to alter family income directly were the Negative Income Tax Experiments, which were conducted between 1968 and 1982 with the primary goal of identifying the influence of guaranteed income on parents’ labor force participation. Using information from those sites that also collected data on child achievement and attainment, Maynard and Murnane (1979) found that elementary school children in the experimental group exhibited higher levels of early academic achievement and school attendance. No test score differences were found for adolescents, although youths in the experimental group did have higher rates of high school completion and educational attainment (Salkind & Haskins, 1982). This suggests that higher income may indeed cause higher child achievement. However, even in this case it is impossible to distinguish the effects of income from the reductions in parental work effort that accompanied the income, in part because of the complicated way in which the benefit payments were calculated (Moffitt, 2003).

Experimental welfare reform evaluation studies undertaken during the 1990s provide more recent opportunities to consider how policies that increase family income affect poor children's development. One study analyzed data from seven random-assignment welfare and antipoverty policies, all of which increased parental employment, whereas only some increased family income (Morris, Duncan, & Clark-Kauffman, 2005). Preschool and elementary school children's academic achievement was improved by programs that boosted both income and parental employment but not by programs that increased only employment. The school achievement of adolescents did not appear to benefit from either kind of program.

Causal impacts can sometimes be inferred even when families are not randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. One such study capitalized on the natural variation in policy implementation to evaluate the impact of income on children's school achievement (Dahl & Lochner, 2008). Between 1993 and 1997, the maximum Earned Income Tax Credit, which provides a credit to working poor families, increased from $1,801 to $3,923 for a family with two children, which enabled Dahl and Lochner (2008) to compare the school achievement of children in otherwise similar working families before and after the increase in the tax credit. They found improvements in low-income children's achievement that coincided with the policy change.

A second, Canadian-based study took advantage of variation across Canadian provinces in the generosity of the National Child Benefit program to estimate income impacts on child outcomes observed in Canadian achievement data (Milligan & Stabile, 2008). Among children residing in low-income families, policy-induced income increases had a positive and significant correlation with both math and vocabulary scores. Both studies estimated similar effect sizes: A $3,000 increment to annual family income was associated with a one-fifth standard deviation increase in test scores. Interestingly, this study also found that higher income was associated with a drop in maternal depression, which suggests a possible pathway for the observed income effects.

These findings suggest that income might play a causal role in younger children's achievement, although it should be kept in mind that the programs with positive effects on children increased both income and parental employment. Combining these results with those from the 1970s experiments reviewed earlier, it is apparent that income effects on younger children's achievement emerge when policies increase parental employment as well as when they decrease employment, which suggests that the income boost may have been the most active ingredient in the beneficial impacts, a premise we test in this article.

A third natural experimental study examined the impact of the introduction of a casino by a tribal government in North Carolina, which distributed approximately $6,000 per person to all adult tribal members each year (Akee, Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2010). Its comparison of Native American children with non-Native American children, before and after the casino opened, found that receipt of casino payments for about 6 years increased the educational attainment of poor Native American youth by nearly a year. It also found that increased family income reduced criminal behavior and drug use, thereby benefiting society as a whole.

Our use of random assignment as an instrument is similar to the approach taken by Ludwig and Kling (2007) in their investigation of neighborhood effects on adolescent crime in the five-city Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration (see also Gennetian et al., 2008; Gennetian, Morris, Bos, & Bloom, 2005; Kling, Liebman, & Katz, 2007). MTO randomly assigned families to one of two different voucher-based mobility treatments or to a control group. To separate the effects of neighborhood crime, tract-level poverty, and racial composition on crime, MTO used cross-site variation in experimental impacts on neighborhood conditions and crime to estimate an instrumental-variables model of neighborhood effects on crime. Although each site tested a single MTO program, cross-site variation in neighborhood conditions emerged from the site-specific implementation of the experiment and local conditions.

In this article, we use cross-site variability in experimental impacts on parents’ income and children's achievement. Because prior research has found stronger effects for preschool children and for low-income samples, we focus our effort on identifying the causal effects of income for this group of children and families. Moreover, given the stronger evidence for the effects of income on cognitive and schooling outcomes, we examine the effects of increases in income on children's achievement in school and standardized test scores.

Method

Studies and Sample

As shown in Table 1, our data come from seven random-assignment studies conducted by MDRC that collectively evaluated 10 welfare and antipoverty programs in 11 sites, producing a total of 16 program/site combinations: Connecticut's Jobs First (D. Bloom et al., 2002); Florida's Family Transition Program (FTP; D. Bloom et al., 2000); the Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence Evaluation (LA-GAIN; Freedman, Knab, Gen netian, & Navarro, 2000); the Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP; testing the effects of two programs, the Full MFIP in urban and rural counties and the MFIP Incentives Only in urban counties only; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Miller et al., 2000); the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies (NEWWS; testing the effects of two programs, the Labor Force Attachment [LFA] and the Human Capital Development [HCD], in Atlanta, Georgia; Grand Rapids, Michigan; and Riverside, California; Hamilton et al., 2001); the New Hope Project (Huston et al., 2001); and the Canadian Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP; testing the effects of two programs, SSP in the provinces of New Brunswick and British Columbia and SSP-Plus in New Brunswick; Michalopoulos et al., 2002; Quets, Robins, Pan, Michalopoulos & Card, 1999).

Table 1.

Details of the Random Assignment Experimental Studies Used in This Analysis

| Study | Random assignment study design | Key policy features tested | Target sample and site(s) | Start date (follow-up length) | Response rates for follow-up surveys | No. of participants | Project synopsis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut's Jobs First | 2 groups: Jobs First and control | Mandatory employment services; Generous earnings supplement; Time limits | Single-parent welfare recipients in New Haven and Manchester, CT | 1996 (36 mo.) | 71–80 | 1,521 | Generous earnings disregard (parents could keep entire welfare grant while working), requirements to participate in employment-related activities, and short welfare time limit. |

| Florida's Family Transition Program (FTP) | 2 groups: FTP and control | Mandatory employment services; Time limits; Expanded child care resources | Single-parent welfare recipients in Escambia County, FL | 1994 (48 mo.) | 78–80 | 1,110 | Time limit on receipt of welfare benefits, requirements to participate in employment-related activities, and supported referral to child care. |

| Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence Evaluation (LA-GAIN) | 2 groups: LA–GAIN and control | Mandatory employment services | Single-parent welfare recipients in Los Angeles County, CA | 1996 (24 mo.) | 74 | 169 | Required participation in employment-related activities as a condition for receiving welfare. |

| Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP) | 3 groups: Full MFIP, MFIP Incentives Only, and control | Mandatory employment services; Time limits; Expanded child care resources | Single-parent welfare recipients in seven counties in Minnesota | 1994 (36 mo.) | 80–81 | 1,547 (urban), 348 (rural) | Full MFIP: requirements to participate in employment-related activities, earnings disregards (parents could keep part of welfare grant if they worked), and prepayment for child care. MFIP Incentives Only: no mandates to participate. |

| National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies | 3 groups: Human Capital Development, Labor Force Attachment, and control | Mandatory employment services | Single-parent welfare recipients in Atlanta, GA; Grand Rapids, MI; and Riverside, CA | 1991 (24 mo. and 60 mo.) | 80–91 at 24 mo.; 63–86 at 60 mo. | 3,706 (Atlanta), 2,116 (Grand Rapids), 2,625 (Riverside) | Required participation in employment- or education-related activities as a condition for receiving welfare. |

| New Hope Project | 2 groups: New Hope program and control | Generous earnings supplement; Expanded child care resources | Low-income parents willing to work in Milwaukie, WI | 1994 (24 mo. and 60 mo.) | 79 at 24 mo.; 71 at 60 mo. | 1,049 | Offered cash supplement as well as health and child care subsidies contingent on full-time work. |

| Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP) | 2 groups in British Columbia and New Brunswick: SSP and control; Separate substudy for 2 groups in New Brunswick: SSP-Plus and control | Generous earnings supplement | Single-parent long-term welfare recipients in two Canadian provinces | 1992 (36 mo. and 54 mo.) | 81 at 36 mo.; 85 at 54 mo. | SSP study: 2,131 (British Columbia), 1,844 (New Brunswick); SSP-Plus study: 471 (New Brunswick) | Offered cash supplement contingent on full-time work. SSP-Plus added employment services. |

Across these studies, various packages of welfare and antipoverty policies were tested; however, all programs were aimed at increasing the self-sufficiency of low-income parents. The programs can be characterized by five program components (most programs mixed and matched these strategies to implement a “packaged” approach): generous earnings supplements, work first, education/training first, time limits, and child care assistance programs. Generous earnings supplement programs are designed to make work pay by providing cash supplements outside the welfare system or by allowing parents to keep part of their welfare grant as their earnings increase. The remaining programs attempt to boost work through the use of services, sanctions, and time limits. The service component of these programs mandates participation in education and training (in the education/training first model) or job search assistance (in the work first model) and enforces sanctions for nonparticipation. Some programs pair these self-sufficiency strategies with expanded child care assistance, which is designed to enhance access to subsidies and child care information by offering services such as resource and referral, encouragement of formal care, higher income-eligibility limits, direct payment to providers, and reduced bureaucratic barriers (Gennetian, Crosby, Huston, & Lowe, 2004).

The mixture of earnings supplement programs and nonearnings supplement programs (those that attempt to increase income and employment compared with those that attempt to increase employment alone) provides key variation in the impact of these programs on income. Additional variation arises from program implementation differences across sites within similarly classified program models (H. S. Bloom, Hill, & Riccio, 2003). For example, programs with mandatory components differed considerably in the extent to which they emphasized quick job entry (to take any job quickly as opposed to searching for the highest quality job), and differences in this characteristic of program implementation has been found to be associated with differing impacts on parents’ employment (H. S. Bloom et al., 2003) and parents’ depression (Morris, 2008).

For all programs, participants were randomly assigned to the given program or to a control group that continued to be eligible to receive welfare as usual (the Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC] system for the U.S. studies and Income Assistance for the Canadian study). In all but one study, parents were applying for welfare or renewing eligibility when they were randomly assigned (in the case of the New Hope study, all geographically eligible low-income parents could participate).

Taken together, these studies provide 18,677 child observations taken from 10,238 children living in 9,113 primarily single-parent families. Children's ages ranged from 2 to 5 at the time of random assignment. Differences in baseline parent and family characteristics between treatment and control groups are presented in Table 2. As would be expected from successful random assignment, few differences are statistically significant at the .05 level, and none are consistently significant across studies.

Table 2.

Selected Baseline and Demographic Characteristics by Research Group and Study

| Connecticut jobs first |

FTP |

LA–GAIN |

New hope project |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Control | Exp | Sig | Control | Exp | Sig | Control | Exp | Sig | Control | Exp | Sig |

| Parent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Parent under 18 at child's birth (%) | 0.122 | 0.132 | 0.137 | 0.146 | 0.073 | 0.115 | 0.169 | 0.112 | ** | |||

| Race (%) | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.437 | 0.404 | 0.583 | 0.576 | 0.390 | 0.402 | 0.545 | 0.576 | ||||

| White | 0.324 | 0.361 | 0.403 | 0.410 | 0.171 | 0.103 | 0.134 | 0.122 | ||||

| Latino | 0.238 | 0.225 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.378 | 0.448 | 0.299 | 0.265 | ||||

| Other | 0.001 | 0.009 | * | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.061 | 0.046 | 0.072 | 0.076 | |||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Never married | 0.732 | 0.711 | 0.510 | 0.570 | 0.512 | 0.598 | 0.698 | 0.675 | ||||

| Separated/divorced | 0.257 | 0.271 | 0.474 | 0.426 | 0.415 | 0.379 | 0.200 | 0.241 | ||||

| Married | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.073 | 0.023 | 0.102 | 0.084 | ||||

| Parent education, employment, and income | ||||||||||||

| Received high school degree or GED (%) | 0.633 | 0.585 | 0.565 | 0.481 | ** | 0.390 | 0.529 | * | 0.603 | 0.665 | ||

| Employed in year prior to random assignment (%) | 0.507 | 0.447 | * | 0.464 | 0.442 | 0.354 | 0.425 | 0.685 | 0.708 | |||

| Earnings in year prior to random assignment (in $1,000s) | 2.954 | 2.576 | 1.907 | 1.841 | 1.767 | 2.378 | 4.381 | 4.693 | ||||

| Length of AFDC receipt prior to random assignment (yrs) | 2.665 | 2.634 | 2.583 | 2.534 | 2.683 | 2.701 | 2.477 | 2.637 | *** | |||

| Family composition and child age | ||||||||||||

| Focal child's age (yrs) | 4.036 | 4.003 | 3.885 | 3.966 | 5.351 | 5.320 | 4.136 | 3.981 | * | |||

| Average age of youngest child (yrs) | 3.234 | 3.165 | 2.912 | 3.046 | 4.293 | 4.276 | 2.293 | 2.584 | ** | |||

| Average no. of children in family | 2.369 | 2.397 | 2.593 | 2.680 | 2.622 | 2.322 | 2.781 | 2.706 | ||||

| Sample size | 762 | 759 | 563 | 547 | 82 | 87 | 539 | 510 | ||||

| SSP–British Columbia |

SSP–New Brunswick |

SSP-Plus–New Brunswick |

MFIP–Rural |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Parent under 18 at child's birth (%) | 0.062 | 0.051 | 0.107 | 0.125 | 0.128 | 0.131 | 0.094 | 0.091 | ||||

| Race (%) | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.031 | 0.011 | * | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.005 | |||

| White | 0.651 | 0.665 | 0.863 | 0.897 | 0.885 | 0.911 | 0.917 | 0.898 | ||||

| Latino | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.011 | ||||

| Other | 0.289 | 0.295 | 0.131 | 0.088 | * | 0.094 | 0.076 | 0.068 | 0.086 | |||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Never married | 0.521 | 0.500 | 0.672 | 0.701 | 0.692 | 0.700 | 0.349 | 0.301 | ||||

| Separated/Divorced | 0.448 | 0.476 | 0.298 | 0.271 | 0.278 | 0.287 | 0.641 | 0.694 | ||||

| Married | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.002 | ** | 0.026 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.005 | |||

| Parent education, employment, and income | ||||||||||||

| Received high school degree or GED (%) | 0.428 | 0.499 | * | 0.487 | 0.508 | 0.556 | 0.591 | 0.781 | 0.828 | |||

| Employed in year prior to random assignment (%) | 0.216 | 0.258 | 0.289 | 0.306 | 0.316 | 0.304 | 0.469 | 0.500 | ||||

| Earnings in year prior to random assignment (in $1,000s) | 0.995 | 1.011 | 1.144 | 0.987 | 0.871 | 0.690 | 2.982 | 2.921 | ||||

| Length of AFDC receipt prior to random assignment (yrs) | 2.712 | 2.765 | * | 2.863 | 2.884 | 2.850 | 2.878 | 2.646 | 2.500 | * | ||

| Family composition and child age | ||||||||||||

| Focal child's age (yrs) | 3.803 | 3.914 | * | 3.829 | 3.923 | 3.957 | 3.992 | 4.092 | 3.947 | |||

| Average age of youngest child (yrs) | 2.591 | 2.812 | ** | 2.591 | 2.838 | ** | 2.927 | 2.890 | 3.005 | 2.667 | * | |

| Average number of children in family | 1.965 | 1.924 | 1.913 | 1.789 | * | 1.765 | 1.755 | 2.422 | 2.290 | |||

| Sample size | 1,034 | 1,097 | 816 | 1,028 | 234 | 237 | 192 | 186 | ||||

| MFIP–Urban Full |

MFIP–Urban Incentives Only |

NEWWS–Atlanta LFA |

NEWWS–Atlanta HCD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Parent under 18 at child's birth (%) | 0.103 | 0.104 | 0.103 | 0.117 | 0.070 | 0.038 | * | 0.070 | 0.051 | |||

| Race (%) | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.378 | 0.370 | 0.378 | 0.408 | 0.959 | 0.952 | 0.959 | 0.962 | ||||

| White | 0.502 | 0.503 | 0.502 | 0.482 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.033 | 0.033 | ||||

| Latino | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.002 | ||||

| Other | 0.098 | 0.100 | 0.098 | 0.090 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.003 | ||||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Never married | 0.594 | 0.597 | 0.594 | 0.619 | 0.714 | 0.763 | 0.714 | 0.714 | ||||

| Separated/Divorced | 0.400 | 0.403 | 0.400 | 0.368 | 0.272 | 0.231 | 0.272 | 0.279 | ||||

| Married | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.007 | ||||

| Parent education, employment, and income | ||||||||||||

| Received high school degree or GED (%) | 0.738 | 0.698 | 0.738 | 0.697 | 0.656 | 0.619 | 0.656 | 0.658 | ||||

| Employed in year prior to random assignment (%) | 0.496 | 0.517 | 0.496 | 0.504 | 0.375 | 0.333 | 0.375 | 0.347 | ||||

| Earnings in year prior to random assignment (in $1,000s) | 3.427 | 3.711 | 3.427 | 2.426 | ** | 1.324 | 1.116 | 1.324 | 0.962 | ** | ||

| Length of AFDC receipt prior to random assignment (yrs) | 2.387 | 2.342 | 2.387 | 2.578 | *** | 2.764 | 2.784 | 2.764 | 2.780 | |||

| Family composition and child age | ||||||||||||

| Focal child's age (yrs) | 4.005 | 3.916 | 4.005 | 3.958 | 4.334 | 4.460 | ** | 4.334 | 4.432 | * | ||

| Average age of youngest child (yrs) | 2.642 | 2.599 | 2.642 | 2.695 | 3.793 | 3.821 | 3.793 | 3.794 | ||||

| Average number of children in family | 2.347 | 2.411 | 2.347 | 2.399 | 2.195 | 2.264 | 2.195 | 2.321 | ||||

| Sample size | 542 | 559 | 542 | 446 | 1,225 | 1,099 | 1,225 | 1,382 | ||||

| NEWWS–Grand Rapids LFA |

NEWWS–Grand Rapids HCD |

NEWWS–Riverside LFA |

NEWWS–Riverside HCD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Parent under 18 at child's birth (%) | 0.156 | 0.137 | 0.156 | 0.085 | ** | 0.074 | 0.058 | 0.080 | 0.070 | |||

| Race (%) | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.392 | 0.420 | 0.392 | 0.322 | 0.199 | 0.158 | 0.161 | 0.155 | ||||

| White | 0.508 | 0.489 | 0.508 | 0.596 | * | 0.431 | 0.433 | 0.369 | 0.348 | |||

| Latino | 0.073 | 0.069 | 0.073 | 0.065 | 0.346 | 0.383 | 0.444 | 0.458 | ||||

| Other | 0.027 | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.038 | ||||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Never married | 0.590 | 0.609 | 0.590 | 0.578 | 0.424 | 0.430 | 0.427 | 0.487 | ||||

| Separated/Divorced | 0.388 | 0.349 | 0.388 | 0.406 | 0.555 | 0.549 | 0.556 | 0.481 | ||||

| Married | 0.022 | 0.043 | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.032 | ||||

| Parent education, employment, and income | ||||||||||||

| Received high school degree or GED (%) | 0.582 | 0.618 | 0.582 | 0.634 | 0.508 | 0.575 | 0.254 | 0.237 | ||||

| Employed in year prior to random assignment (%) | 0.610 | 0.516 | * | 0.610 | 0.543 | 0.310 | 0.272 | 0.278 | 0.298 | |||

| Earnings in year prior to random assignment (in $1,000s) | 2.728 | 2.113 | 2.728 | 2.621 | 1.876 | 1.723 | 1.537 | 1.414 | ||||

| Length of AFDC receipt prior to random assignment (yrs) | 2.740 | 2.762 | 2.740 | 2.650 | * | 2.665 | 2.673 | 2.748 | 2.739 | |||

| Family composition and child age | ||||||||||||

| Focal child's age (yrs) | 4.298 | 4.310 | 4.298 | 4.291 | 4.140 | 4.150 | 4.160 | 4.085 | ||||

| Average age of youngest child (yrs) | 3.037 | 2.973 | 3.037 | 3.067 | 3.563 | 3.488 | * | 3.559 | 3.503 | |||

| Average number of children in family | 2.125 | 2.122 | 2.125 | 2.041 | 2.142 | 2.318 | 2.277 | 2.320 | ||||

| Sample size | 730 | 728 | 730 | 658 | 1,293 | 603 | 853 | 729 | ||||

Note. t tests were applied to differences between the experimental and control group covariates. FTP = Florida's Family Transition Program; LA–GAIN = Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence Evaluation; Exp = experimental group; Sig = significance of the difference between the control and experimental groups; GED = general equivalency diploma; AFDC = Aid to Families with Dependent Children; SSP = Self-Sufficiency Project; MFIP = Minnesota Family Investment Program; NEWWS = National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies; LFA = Labor Force Attachment experimental group; HCD = Human Capital Development experimental group.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Procedures and Measures

Data in each study were compiled from several sources. One, basic demographic information, including prior employment history, on all sample parents at the point of random assignment (baseline) to the program and control groups was completed by welfare and program office staff. Two, administrative records provided information on welfare receipt, employment, and program payments prior to random assignment and during the follow-up period. Three, a parent survey was conducted with each family 2–5 years after baseline, depending on the study. And four, in some studies, children were tested to determine academic achievement and/or elementary school teachers completed a survey about children's academic achievement 2–5 years after baseline.

Participants volunteered for New Hope; in all other cases their application to the welfare system or receipt of welfare required participation in the random assignment and the administrative sources of data collection. Parents could opt to not respond to the evaluation surveys, but response rates in all studies were high—between 71% and 90%, and nonresponse bias analyses conducted as part of the original studies confirmed the equivalence of program and control groups in these respondent samples (D. Bloom et al., 2000, 2002; Bos et al., 1999; Freedman et al., 2000; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Hamilton et al., 2001; McGroder, Zaslow, Moore, & LeMenestrel, 2000; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000).

Family income

Our key endogenous variable was family income. For all sample members in the six U.S. studies, administrative records provided data on monthly cash assistance and Food Stamp benefits and any cash supplement payments provided by the earnings supplement programs, as well as quarterly earnings in jobs covered by the Unemployment Insurance system. For the Canadian SSP samples, administrative records provided information on receipt of Income Assistance and receipt of SSP supplement payments, while the parent survey collected data on earnings from employment. For each quarter following random assignment, we computed an average quarterly parent income based on the sum of earnings, AFDC/Temporary Assistance for Needy Families/Income Assistance and supplement payments, and Food Stamp payments. Note that this income measure omits self-employment and informal earnings (except in SSP), other public transfers, private transfers, and earnings from family members other than the sample member (although nearly the entire sample was composed of single parents). All income amounts have been inflation-adjusted to 2001 prices using the Consumer Price Index. Canadian dollars were converted to American dollars before being adjusted for inflation. From this information, average annual income (in $1,000s) and log average annual income were computed over the time between random assignment and the assessment of child achievement.

School achievement

Children's cognitive performance or school achievement was measured using parent or teacher report or test scores. The SSP, Connecticut, FTP, New Hope, MFIP, and LA-GAIN studies included parent reports of children's achievement on a 5-point rating of how well children were doing in school (n = 7,958; these are based on a single item measure; except in SSP, these are based on an average of children's reported functioning in three academic subjects). Teacher reports of achievement—collected in Connecticut, New Hope, and NEWWS (n = 2,074)—were based on items from the Academic Subscale of the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990). On this 10-item measure, teachers compared children's performance with that of other students in the same classroom on reading skill, math skill, intellectual functioning, motivation, oral communication, classroom behavior, and parental encouragement (internal consistency α = .94).

Test scores included the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 1981) for children ages 4–7 at the 36-month follow-up in SSP (n = 1,039), a math skills test containing a subset of items from the Canadian Achievement Tests (2nd ed.) for children ages 8 and up at the 36-month follow-up in SSP (n = 573), the Bracken Basic Concept Scale (Bracken, 1984) for children in NEWWS at the 2-year follow-up (n = 2,867), and the Math (N = 2,078) and Reading (N = 2,078) scores from the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery—Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1989–1990) for children in NEWWS at the 5-year follow-up, all well validated and reliable tests of children's cognitive performance. Consistent with the approach of Morris, Duncan, and Clark-Kauffman (2005) using these same data, to provide comparability in outcomes across studies, these achievement outcomes were standardized in our research by subtracting study-specific means and dividing by study-specific control-group standard deviations. A similar approach was utilized in other research involving multiple studies in which each study collected slightly differing measures of achievement (see Anderson, 2008). Combining across measures allowed us to test whether our results were robust across alternative measures of children's achievement.

Parent and teacher reports of children's achievement in these data were modestly correlated (r = .37), whereas, not surprisingly, teacher reports and test scores were more highly associated (r = .49–.54 between teacher reports and ratings on the Woodcock Johnson tests of math and reading). Important for this analysis, tests of whether experimental impacts on child achievement varied by source of report could not reject the null hypothesis of equivalence. That is, we interacted source-of-report dummies with the experimental dummy in models predicting child achievement. We found no significant differences in the experimental impacts depending on the source of achievement report, F(2, 9112) = 0.33, p = .72. Also, when we estimated impacts on child achievement in the individual studies in which multiple measures were available, we did not find significant interactions between source-of-report dummies and the experimental assignment indicator.

Proportion of quarters employed

From our Unemployment Insurance quarterly earnings data we calculated parental employment for each quarter of the follow-up period. Sample members were coded as having been employed in a quarter if their earnings for that quarter were greater than zero. Because these studies had differing lengths of follow-up, we calculated the proportion of quarters employed over follow-up by counting the numbers of quarters employed and dividing by the number of quarters in follow-up.

Employment hours

For the SSP, Connecticut, NEWWS (2-year follow-up only), and LA-GAIN studies, employment in formation was collected via the parent surveys. For each job parents had between random assignment and the survey, parents were asked to report the month and year in which they started and ended each job. Additionally, parents were asked to report for each job the number of hours worked per week when they left the job (or currently if still working). Respondents were asked to report all jobs, including self-employment and any other employment that may have taken place informally or out of state. Average hours employed per quarter over the follow-up was computed using the employment information on all jobs listed in the parent survey.

Welfare receipt

Monthly or quarterly welfare receipt from public assistance records was collected for all years of the follow-up period for each study. Proportion of quarters receiving any welfare was computed for all years of the follow-up using these data. Sample members were coded as having received welfare in a quarter if their welfare payments for that quarter were greater than zero. Our welfare variable is the average welfare receipt rate across all quarters of the follow-up period.

Other control variables

Covariates included in the first- and second-stage models were baseline parental and family characteristics (no baseline data were collected on children's outcomes in these studies). Administrative data and baseline surveys taken just prior to random assignment provided the following information: comparable pre-random-assignment measures of child age, number of years of receipt of cash assistance prior to baseline, average earnings in the year prior to baseline and its square, measures of whether the parent was employed in the year prior to baseline, whether the parent had a high school degree or general equivalency diploma, age of the child, whether the parent was a teenager at the time of the child's birth, the marital status of the parent, the number of children in the family, the age of the youngest child in the family, and the race/ethnicity of the parent. We also included controls for length of follow-up and type of achievement assessment, as well as dummy variables representing site/study controls.

Analysis Strategy

As with Ludwig and Kling (2007), we capitalized on program and site variation using an instrumental variables (IV) estimation strategy (for greater discussion of this approach, see Gennetian et al., 2008; Gennetian et al., 2005). IV estimation is designed to improve one's ability to draw causal inferences from nonexperi-mental data. The basic idea is simple: If one can isolate a portion of variation in family income that is unrelated to unmeasured confound variables and then use only that portion to estimate income effects, then the resulting estimates are likely to be free from omitted-variable bias.

In effect, IV methods seek to approximate experiments by focusing only on “exogenous” variation in family income caused by some process that is completely beyond the control of the family. In our case, random assignment to treatment or control groups in the various welfare experiments was an excellent candidate for an IV variable because families had no say in whether they were assigned to the experimental or control group as a function of the lottery-like random assignment process.

More formally, we used interactions between treatment group assignments (T) and site (S) as instrumental variables to isolate experimentally induced variations in income (Inc) and achievement (Ach) across program models (ε is the error term). With X denoting baseline covariates, the models are shown in the following equations:

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

In effect, Equation 1 estimates Inc on the basis of experimental assignment and controls by site, whereas Equation 2 regresses the predicted level of Inc taken from Equation 1 on child achievement. The inclusion of the same control variables in Equation 2 as in Equation 1 and, importantly, of site fixed effect dummies ensures that the only variation in Inc used in the estimation of Ach comes from the lottery-based assignment to treatment and control groups by site.

The success of IV models such as those seen in Equations 1 and 2 depends on the strength of first-stage prediction of income on the basis of being randomly assigned to the program treatment groups. Our site-based instruments had relatively strong predictive power. In the case of prediction of parents’ annual income and log income, the F statistics for the instruments when using program components that interacted with treatment group assignment as instruments were 45.68 and 26.64, respectively, and the F statistics for the instruments when using the Site × Treatment Group interactions as instruments were 15.59 and 9.71, respectively. This is important because it has been shown that weak instruments can result in potentially biased IV estimates as well as large errors in the second stage of the procedure. In our case, the F statistics show that our instruments are close to or exceed recommended levels (Bound, Jaeger, & Baker, 1995).

Exclusion restrictions required that our random-assignment instruments affect achievement only through their effect on income (Angrist, Imbens, & Rubin, 1996). There are several reasons why this assumption might not have been met in our studies. First, some programs provided child care subsidies and others mandated mothers’ participation in educational activities. Because both center-based child care (see e.g., National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network & Duncan, 2002) and maternal schooling (see e.g., Magnuson, 2003) have been linked to child achievement, these program elements provide ways in which assignment to these programs could have influenced achievement independently of income. Because we could account for these effects of the treatment that occurred alongside the changes in income we observed for all the children in the sample, we estimated Models 1 and 2 for a reduced set of programs that provided neither child care subsidies nor education mandates (leaving us with NEWWS–LFA, LA-GAIN, SSP, and Connecticut for the analysis). These provided arguably our least biased estimates of the effects of income on child achievement.

A second concern was that all of the intervention studies sought to increase maternal employment and reduce welfare use. Maternal employment could have an independent effect on children's achievement by altering parental time allocation and thus violate the exclusion restriction (see e.g., Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2002; Waldfogel, Han, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Prior research has also suggested that welfare receipt may itself have an independent effect on children because of the stigma associated with welfare receipt, although the evidence on this issue is mixed (see e.g., Levine & Zimmerman, 2005). To address this concern, we estimated a more complete version of Models 1 and 2 in which time spent in employment and welfare receipt were treated as additional endogenous variables.

Results

Before estimating our model on our full pooled sample, we estimated the set of impacts on economic and child achievement measures, as shown in Table 3. The top panel pools studies by type of program (i.e., program components); the bottom panel shows study-specific results. In all models, baseline child, parental, and family characteristics are included as control variables.1

Table 3.

Impacts on Parents’ Economic Outcomes and Child Achievement, by Program Type and by Study/Site

| Dependent variables |

IV model results |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program type and study/site | Prop. of quarters employed over follow-up | Average annual income (in $l,000s) | Log average annual income | Prop. of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | Child achievement | Effects of income on child achievement | Effects of log income on child achievement |

| Program type (not mutually exclusive) | |||||||

| Earnings supplements (n = 8,941) | 0.086 (0.010)*** | 1.468 (0.158)*** | 0.137 (0.018)*** | –0.035 (0.010)*** | 0.076 (0.024)*** | 0.052 (0.017)*** | 0.554 (0.188)*** |

| Work first (n = 9,957) | 0.079 (0.010)*** | 0.446 (0.156)*** | 0.025 (0.021) | –0.022 (0.010)** | 0.040 (0.025) | 0.089 (0.064) | 1.627 (1.710) |

| Education/training first (n = 6,017) | 0.044 (0.014)*** | 0.308 (0.196) | 0.046 (0.025)* | –0.003 (0.013) | 0.027 (0.037) | 0.089 (0.130) | 0.596 (0.852) |

| Time limits (n = 2,631) | 0.061 (0.016)*** | 0.505 (0.251)** | 0.033 (0.035) | –0.014 (0.015) | 0.064 (0.041) | 0.127 (0.105) | 1.926 (2.461) |

| Child care assistance programs (n = 4,084) | 0.072 (0.013)*** | 0.961 (0.244)*** | 0.074 (0.031)** | 0.001 (0.013) | 0.050 (0.034) | 0.052 (0.037) | 0.681 (0.543) |

|

Study/site | |||||||

| Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP) | |||||||

| British Columbia (n = 2,131) | 0.076 (0.023)*** | 1.609 (0.327)*** | 0.146 (0.031)*** | –0.056 (0.020)*** | 0.112 (0.050)** | 0.070 (0.034)** | 0.768 (0.375)** |

| New Brunswick (n = 1,844) | 0.135 (0.023)*** | 1.916 (0.274)*** | 0.192 (0.035)*** | –0.142 (0.023)*** | 0.125 (0.054)** | 0.065 (0.030)** | 0.648 (0.306)** |

| SSP Plus–New Brunswick (n = 471) | 0.116 (0.047)** | 2.244 (0.455)*** | 0.243 (0.071)*** | –0.170 (0.043)*** | 0.061 (0.113) | 0.027 (0.052) | 0.252 (0.491) |

| Connecticut's Jobs First (n = 1,521) | 0.053 (0.021)** | 0.813 (0.362)** | 0.074 (0.041)* | 0.038 (0.020)* | 0.032 (0.054) | 0.040 (0.069) | 0.436 (0.779) |

| MFIP | |||||||

| Urban Full (n = 1,101) | 0.114 (0.022)*** | 1.302 (0.409)*** | 0.130 (0.057)** | 0.071 (0.022)*** | 0.045 (0.056) | 0.035 (0.044) | 0.345 (0.461) |

| Urban Incentives Only (n = 988) | 0.050 (0.024)** | 0.914 (0.413)** | 0.109 (0.063)* | 0.105 (0.024)*** | –0.016 (0.062) | –0.018 (0.068) | –0.150 (0.569) |

| Rural Full (n = 378) | 0.086 (0.041)** | 1.630 (0.585)*** | 0.158 (0.075)** | 0.077 (0.039)** | –0.013 (0.093) | –0.008 (0.057) | –0.081 (0.591) |

| New Hope (n = 1,049) | 0.065 (0.023)*** | 1.630 (0.541)*** | 0.125 (0.047)*** | –0.023 (0.023) | 0.034 (0.066) | 0.021 (0.041) | 0.272 (0.533) |

| NEWWS | |||||||

| Atlanta LFA (n = 2,324) | 0.046 (0.023)** | 0.317 (0.286) | 0.043 (0.029) | –0.020 (0.022) | 0.074 (0.059) | 0.232 (0.264) | 1.705 (1.663) |

| Atlanta HCD (n = 2,607) | 0.020 (0.021) | 0.398 (0.262) | 0.055 (0.027)** | –0.007 (0.019) | 0.101 (0.056)* | 0.255 (0.205) | 1.835 (1.265) |

| Grand Rapids LFA (n = 1,458) | 0.104 (0.027)*** | 0.072 (0.452) | –0.045 (0.062) | –0.074 (0.028)*** | 0.030 (0.070) | 0.414 (2.720) | –0.667 (1.873) |

| Grand Rapids HCD (n = 1,388) | 0.026 (0.026) | 0.004 (0.462) | –0.007 (0.056) | 0.011 (0.027) | –0.050 (0.078) | –12.823 (1,511.755) | 7.043 (54.664) |

| Riverside LFA (n = 1,896) | 0.121 (0.028)*** | 0.095 (0.497) | –0.042 (0.077) | –0.079 (0.029)*** | 0.007 (0.070) | 0.071 (0.801) | –0.162 (1.732) |

| Riverside HCD (n = 2,022) | 0.099 (0.024)*** | 0.557 (0.354) | 0.072 (0.053) | 0.007 (0.024) | –0.036 (0.066) | –0.065 (0.123) | –0.505 (0.971) |

| LA-GAIN (n = 169) | –0.004 (0.062) | –1.047 (0.884) | –0.112 (0.096) | 0.009 (0.045) | 0.000 (0.157) | 0.000 (0.150) | –0.003 (1.405) |

| FTP (n = 1,110) | 0.069 (0.022)*** | 0.137 (0.330) | –0.019 (0.059) | –0.084 (0.020)*** | 0.112 (0.063)* | 0.816 (2.041) | –6.021 (19.141) |

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses. Means and standard deviations of each variable are as follows: average hours employed per quarter (M = 145.3, SD = 167.3); average quarters receiving any welfare (M = .747, SD = .321); average annual income (M = 11.0, SD = 5.2); log average annual income (M = 9.19, SD = .583); child achievement (M = .030, SD = .993). Economic variables were measured over study follow-up, and child achievement was measured at the time of follow-up. Separate regression equations were conducted for each study impact. The regressions also included the following covariates measured at baseline: child's age, earnings in the prior year, earnings in the prior year squared, amount of time mother was on welfare, employed in prior year, mother had no high school degree or equivalent, mother's marital status, number of children in the family, age of youngest child, mother's race/ethnicity, and whether parents’ age was less than 18 at the time of child's birth; also included were the following additional covariates: elapsed time between study entry and follow-up, type of achievement report (e.g. parent or test/teacher, when applicable). IV = instrumental variables; Prop. = proportion; MFIP = Minnesota Family Investment Program; NEWWS = National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies; LFA = Labor Force Attachment; HCD = Human Capital Development; LA–GAIN = Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence Evaluation; FTP = Florida's Family Transition Program.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

All types of programs boosted employment to roughly similar degrees, although the earnings supplement programs produced the largest impacts on family income, amounting to nearly $1,500 per year. Welfare use fell the most in the earnings supplement programs as well. Although the point estimates of impacts on achievement were positive for all program types, only in the case of the earnings supplement programs was the coefficient statistically significant. The effect size was small, however, amounting to less than one tenth of a standard deviation.

The study-specific estimates were variable and often imprecise but generally conformed to the impact patterns of their program type. Program impacts on income ranged from –$1,000 to +$2,200 but were positive and statistically significant only for the earnings supplement programs. Program impacts on achievement were positive and statistically significant for only four of the 16 programs, two of which supplemented earnings and two of which did not.

The final two columns of Table 3 show preliminary IV estimates of the effects of annual and log income on child achievement when income was taken to be the only endogenous variable. These coefficients amount to the ratio of program impacts on child achievement to the program impacts on income. Coefficients in the top panel are all positive in sign, although only in the earnings supplement programs are they statistically significant. Site-specific IV estimates show that almost all coefficients are positive in sign, although many of these coefficients have large standard errors.

Pooled IV Estimates

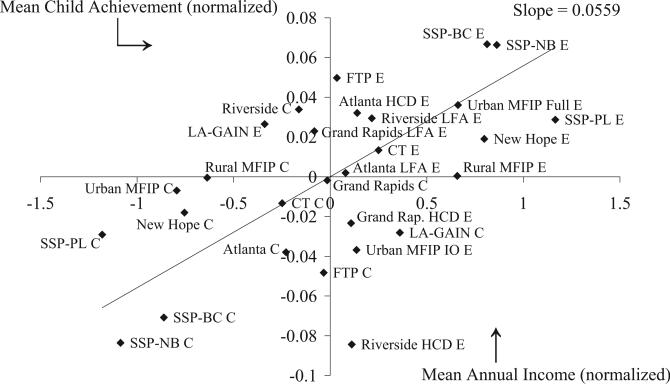

The full power of our IV approach comes from pooling data across all studies. In effect, in any given study, IV estimation leveraged the variation in family income due to random assignment to either the control or experimental group within each program or site—thus ensuring that this variation was unrelated to personal characteristics of the program participants—to predict the relationship between income and child achievement. In the pooled model, we leveraged the variation in impacts on income and child achievement across the studies and sites. This variation is depicted graphically in Figure 1 (see Ludwig & Kling, 2007), where the distance between each point and the x-axis represents the deviation of the group's average income from the overall site's average income and where the distance of each point from the y-axis represents the difference between the group's average child achievement level and the overall site's achievement level.

Figure 1.

Individual study achievement means by income means. E = experimental group; C = control group; FTP = Florida's Family Transition Program; LA-GAIN = Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence; SSP = Self-Sufficiency Project; PL = Plus; BC = British Columbia; NB = New Brunswick; MFIP = Minnesota Family Investment Program; IO = Incentives Only; LFA = Labor Force Attachment; HCD = Human Capital Development; CT = Connecticut's Job's First.

If income mattered for child achievement, we would have expected that the treatment group/site combinations with the biggest positive income deviations would also have the biggest positive achievement deviations. When a trend line was fit through these 28 points, the slope of the line (.0599) was equal to the IV estimate of the effect of income on child achievement including only site dummies as covariates and using Site × Treatment Group inter actions as instruments.2 The interpretation of the slope is that each $1,000 increase in income was associated with a .06 standard deviation increase in child achievement.

First-stage estimates of our IV models were virtually identical to the impacts shown in the second and third columns of Table 3 (see Table 4). This is as was expected because the two sets of estimating equations differed only in that the study-by-study estimates allowed for study-specific coefficients on control variables, whereas the pooled model constrained control coefficients to be identical across studies.

Table 4.

First-Stage Instrumental Variables (IV) Model Results

| Dependent variables |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies |

Reduced set of studies |

|||||||

| Variables interacted with treatment (instruments) | Average annual income (in $l,000s) | Log average annual income | Prop. of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | Prop. of quarters employed over follow-up | Average annual income (in $l,000s) | Log average annual income | Prop. of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | Average hr employed per quarter |

| Program type (not mutually exclusive) | ||||||||

| Earnings supplements | 1.567 (0.117)*** | 0.157 (0.015)*** | –0.044 (0.007)*** | 0.077 (0.008)*** | 1.850 (0.134)*** | 0.178 (0.016)*** | –0.103 (0.009)*** | 50.835 (4.417)*** |

| Work first | 0.150 (0.113) | –0.002 (0.015) | –0.030 (0.007)*** | 0.075 (0.007)*** | 0.096 (0.200) | –0.004 (0.024) | –0.047 (0.013)*** | 38.937 (6.580)*** |

| Education/training first | 0.303 (0.121)** | 0.047 (0.016)*** | 0.001 (0.008) | 0.043 (0.008)*** | ||||

| Time limits | –0.557 (0.221)** | –0.057 (0.029)** | 0.022 (0.014) | –0.054 (0.014)*** | –1.171 (0.333)*** | –0.108 (0.040)*** | 0.182 (0.022)*** | –67.197 (10.934)*** |

| Child care assistance programs | –0.100 (0.179) | –0.020 (0.023) | 0.044 (0.011)*** | –0.011 (0.012) | ||||

| F (instruments) | 45.68*** | 26.64*** | 12.72*** | 56.42*** | 67.10*** | 42.03*** | 50.69*** | 58.85*** |

| Model R2 | 0.259 | 0.134 | 0.234 | 0.274 | 0.269 | 0.147 | 0.168 | 0.236 |

| Model F | 202.96*** | 89.77*** | 177.43*** | 219.28*** | 113.67*** | 53.24*** | 62.30*** | 95.69*** |

| Sample size | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 |

|

Study/site | ||||||||

| Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP) | ||||||||

| British Columbia | 1.577 (0.205)*** | 0.141 (0.027*** | –0.055 (0.013)*** | 0.081 (0.013)*** | 1.594 (0.194)*** | 0.143 (0.023)*** | –0.054 (0.013)*** | 40.848 (6.353)*** |

| New Brunswick | 2.007 (0.207)*** | 0.197 (0.027)*** | –0.146 (0.013)*** | 0.119 (0.014)*** | 2.007 (0.196)*** | 0.198 (0.024)*** | –0.145 (0.013)*** | 56.871 (6.421)*** |

| SSP Plus–New Brunswick | 2.405 (0.340)*** | 0.263 (0.044)*** | –0.161 (0.021)*** | 0.178 (0.022)*** | 2.438 (0.321)*** | 0.265 (0.039)*** | –0.160 (0.021)*** | 74.042 (10.528)*** |

| Connecticut's Jobs First | 0.764 (0.242)*** | 0.068 (0.031)** | 0.034 (0.015)** | 0.056 (0.016)*** | 0.776 (0.229)*** | 0.067 (0.028)** | 0.032 (0.015)** | 22.594 (7.507)*** |

| NEWWS | ||||||||

| Atlanta LFA | 0.299 (0.196) | 0.040 (0.025) | –0.019 (0.012) | 0.043 (0.013)*** | 0.166 (0.306) | 0.035 (0.037) | –0.024 (0.020) | 7.911 (10.051) |

| Atlanta HCD | 0.296 (0.185) | 0.050 (0.024)** | –0.005 (0.012) | 0.015 (0.012) | ||||

| Grand Rapids LFA | 0.108 (0.247) | –0.040 (0.032) | –0.077 (0.015)*** | 0.107 (0.016)*** | 0.096 (0.433) | –0.055 (0.052) | –0.095 (0.028)*** | 78.708 (14.188)*** |

| Grand Rapids HCD | 0.147 (0.254) | 0.000 (0.033) | –0.011 (0.016) | 0.040 (0.017)** | ||||

| Riverside LFA | 0.163 (0.233) | –0.034 (0.030) | –0.074 (0.014)*** | 0.122 (0.015)*** | 0.285 (0.383) | 0.009 (0.046) | –0.058 (0.025)** | 68.730 (12.549)*** |

| Riverside HCD | 0.554 (0.220)** | 0.088 (0.028*** | –0.005 (0.014) | 0.095 (0.014)*** | ||||

| LA–GAIN | –0.846 (0.726) | –0.113 (0.094) | –0.002 (0.045) | –0.003 (0.047) | –0.860 (0.687) | –0.108 (0.083) | –0.001 (0.045) | –1.253 (22.522) |

| MFIP | ||||||||

| Urban Full | 1.317 (0.284)*** | 0.135 (0.037)*** | 0.067 (0.018)*** | 0.116 (0.019)*** | ||||

| Urban Incentives Only | 1.105 (0.302)*** | 0.120 (0.039)*** | 0.099 (0.019)*** | 0.056 (0.020)*** | ||||

| Rural Full | 1.552 (0.486)*** | 0.135 (0.063)** | 0.066 (0.030)** | 0.088 (0.032)*** | ||||

| New Hope | 1.355 (0.292)*** | 0.104 (0.038)*** | –0.041 (0.018)** | 0.049 (0.019)** | ||||

| FTP | 0.037 (0.283) | –0.039 (0.037) | –0.083 (0.018)*** | 0.068 (0.018)*** | ||||

| F (instruments) | 15.59*** | 9.70*** | 18.30*** | 22.66*** | 26.10*** | 17.15*** | 23.32*** | 26.35*** |

| Model R2 | 0.259 | 0.135 | 0.243 | 0.277 | 0.269 | 0.148 | 0.171 | 0.239 |

| Model F | 151.61*** | 67.36*** | 138.89*** | 165.64*** | 95.61*** | 45.04*** | 53.53*** | 81.63*** |

| Sample size | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 |

Notes. Standard errors are in parentheses. Economic variables were measured over study follow-up. The regressions also include the following covariates measured at baseline: child's age, earnings in the prior year, earnings in the prior year squared, amount of time mother was on welfare, employed in prior year, mother had no high school degree or equivalent, mother's marital status, number of children in the family, age of youngest child, mother's race/ethnicity, and whether parents’ age was less than 18 at the time of child's birth; also included were the following additional covariates: study site flags (e.g., NEWWS–Atlanta, NEWWS–Riverside, LA–GAIN), elapsed time between study entry and follow-up. Prop. = proportion; NEWWS = National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies; LFA = Labor Force Attachment; HCD = Human Capital Development; LA–GAIN = Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence Evaluation; MFIP = Minnesota Family Investment Program; FTP = Florida's Family Transition Program.

* p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 5 presents ordinary least squares (OLS) and second-stage IV estimates from a series of achievement models. These models all utilized the pooled data, which represented our preferred models in allowing us to estimate the unique effects of income. We first present the findings using all studies (which include some for which we could not fully control for all the other potential mediators of program impacts), and then we present the results from models using the subset of studies for which we could model key mediators of impacts alongside income (which arguably present our least biased estimates).

Table 5.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Second-Stage Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimates of the Effects of Income on Child Achievement

| OLS |

Program type as instruments IV |

Sites as instruments IV |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model and variable | Log income | Annual income | Log income | Annual income | Log income | Annual income |

| All studies | ||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Income | 0.006 (0.002)*** | 0.049 (0.016)*** | 0.052 (0.016)*** | |||

| Log income | 0.025 (0.016) | 0.453 (0.173)*** | 0.438 (0.162)*** | |||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Income | 0.006 (0.002)** | 0.029 (0.032) | 0.042 (0.029) | |||

| Log income | 0.043 (0.021)** | 0.216 (0.270) | 0.291 (0.236) | |||

| Average hr employed per quarter (in 100 hr) | ||||||

| Proportion of quarters employed over follow-up | 0.004 (0.040) | 0.006 (0.041) | 0.246 (0.530) | 0.332 (0.481) | –0.127 (0.420) | 0.021 (0.365) |

| Proportion of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | –0.159 (0.034)*** | –0.179 (0.037)*** | –0.221 (0.945) | –0.283 (0.941) | –0.512 (0.290)* | –0.559 (0.294)* |

| Sample size | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 | 18,667 |

|

Reduced set of studies | ||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Income | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.063 (0.019)*** | 0.060 (0.019)*** | |||

| Log income | 0.000 (0.024) | 0.649 (0.209)*** | 0.611 (0.201)*** | |||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Income | 0.000 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.043) | 0.062 (0.035)* | |||

| Log income | –0.015 (0.028) | 0.032 (0.411) | 0.539 (0.316)* | |||

| Average hr employed per quarter (in 100 hr) | 0.019 (0.011)* | 0.022 (0.011)* | 0.180 (0.152) | 0.181 (0.144) | –0.029 (0.113) | 0.014 (0.109) |

| Proportion of quarters employed over follow-up | ||||||

| Proportion of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | –0.092 (0.050)* | –0.077 (0.054) | –0.193 (0.789) | –0.190 (0.804) | –0.128 (0.638) | –0.065 (0.670) |

| Sample size | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 | 8,073 |

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

As seen in columns 1 and 2 of Table 5, OLS estimation revealed positive income effects for both linear and log income models, but only the linear model coefficient was statistically significant at conventional levels. Coefficient estimates were small, however, with an additional $1,000 of annual family income being associated with less than 1% of a standard deviation increase in child achievement.3

In the third through sixth columns of Table 5, we present the IV models utilizing all studies available, first using study components as instruments and then using study sites as instruments. When, in Model 1, income is the only endogenous variable, estimates suggest a .05 standard deviation increase in child achievement associated with every $1,000 increase in parents’ annual income and a .45 standard deviation increase in child achievement associated with a log-unit increase in parents’ income.4 Controls for parents’ employment and welfare income decreased the estimated income effect by about half and increased standard errors as well.

The bottom half of Table 5 presents our preferred estimates. In this case, IV estimates were based on the subset of studies that targeted employment, welfare receipt, and/or income but neither maternal education nor child care use. This reduced set of studies better conformed to the exclusion restriction and, with survey data on parents’ work hours, allowed us to substitute a conceptually more appropriate measure of work hours for quarters of employment.

These analyses boosted point estimates of income effects slightly, with $1,000 and log-unit annual income increases associated with .06 and .60 standard deviation increases in child achievement, respectively. The addition of work hours and welfare as endogenous variables had little effect on the income effect estimates in site-based estimates but reduced coefficients and increased standard errors in the program-based estimates. Thus, it appears that the income effects we estimated were largely independent of the changes in employment and welfare receipt that may have been produced by assignment to the experimental treatments.

Concern that results might be sensitive to the source of achievement reports led us to estimate the IV models presented in Table 6, all of which are based on the reduced set of studies and log income and use sites as instruments. As shown in the first column, averaging all available achievement reports for each child increased both coefficient estimates and standard errors modestly (Anderson, 2008). Restricting samples to include just the parent reports and test scores yielded .50–.65 coefficients when income was considered to be the only endogenous variable; in the multiple-endogenous-variable models, very unstable estimates are found.5

Table 6.

Robustness Tests (Instrumental Variables)

| By source of achievement score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average achievement score |

Parent reporta |

Test scoreb |

||||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Log average annual income | 0.734 (0.256)*** | 0.629 (0.369)* | 0.648 (0.262)** | 0.154 (1.447) | 0.512 (0.231)** | 0.179 (0.226) |

| Average hr employed by quarter (in 100 hr) | 0.011 (0.001) | 0.165 (0.445) | –0.140 (0.226) | |||

| Proportion of quarters receiving any welfare over follow-up | –0.159 (0.717) | –0.019 (0.701) | –1.400 (1.804) | |||

| Sample size | 5,693 | 4,280 | 3,549 | |||

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses. The regressions include covariates measured at baseline.

Analyses include Connecticut's Jobs First, Los Angeles Jobs-First Greater Avenues for Independence, Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP), and SSP-Plus programs.

Analyses include National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies, SSP, and SSP-Plus programs.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Finally, concern about the unique effects of the Canadian-based study led us to estimate models with and without SSP and to test for the interaction of country of study with our estimates of income effects. These analyses showed that models without SSP generated similar estimates of the effects of income (coefficients of .06 and .78 for linear and log income, respectively), but the loss of power from the substantial reduction in sample reduced these effects to nonsignificance. Consistent with these findings, formal tests of the significance of the difference of income estimated from models with and without SSP showed no significant differences,6 indicating that country of origin did not interact with the effect of income on child achievement in these IV models (findings are available from the authors).

Discussion

We found noteworthy effects of family income on school achievement of young children in most of our IV models. This effect of income for young children is consistent with some of the nonexperimental research and with some of the emerging studies cited at the outset that attempted to estimate effects of income using models that allow for more definitive causal inference.

The results are consistent with developmental theories suggesting that children's development is malleable and susceptible to family influences during the preschool period (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; McCall, 1981). Although we did not focus on income effects across the childhood age period because of data limitations (not enough of the welfare and employment studies included children across the full childhood age span to allow for such an analysis), our results do show that the preschool period, at least, is amenable to change as a result of parents’ income change generated by employment-incentive programs.

How large are our effects? Our IV estimates suggest that a $1,000 increase in annual income sustained for between 2 and 5 years boosts child achievement by 6% of a standard deviation and that a log-unit increase in annual income increases child achievement by a little over half a standard deviation. These estimates are similar to those estimated in the quasiexperimental studies of Dahl and Lochner (2008) and Akee et al. (2010). Translated into an IQ-type scale, 6% of a standard deviation amounts to about 1 point and half a standard deviation amounts to 8 points. Translated into one of the achievement tests we used—the Bracken Basic Concept Scale—these effect sizes translate into about one and six additional correct answers, respectively, to a 61-question test regarding colors, letters, numbers/counting, comparisons, and shapes.

Are these effect sizes policy-relevant? On the face of it, they seem quite small. And, in fact, experimental studies of early preschool intervention programs offering high levels of quality have shown much larger effects. Treatment effect sizes on IQ were 1.0 standard deviations at 3 years and .75 at age 5 for the Abecedarian Project and .60 for the Perry Preschool Project. But at $40,000 and $15,000, respectively, these large effect sizes came at a great cost. For $7,500, the Tennessee class size experiment showed that smaller K–3 class sizes increased achievement by about .2 of a standard deviation, which was estimated to increase benefits more than cost (Krueger & Whitmore, 2001).

The earnings supplement programs in our study boosted family income for younger children by between $800 and nearly $2,200 per year, which corresponds to achievement effect sizes ranging from 5% to 12% of a standard deviation. Bos, Duncan, Gennetian, and Hill (2007) showed that the benefits to participants and to taxpayers outweighed the costs of one of these programs (the New Hope Project).

Although we want to be cautious about extrapolating beyond our findings, it is possible that larger increases in income to families might produce proportionally larger impacts on children. Moreover, the fact that our income gains may be distributed across children within families argues that the per-child returns of income gains to families are even larger than we present here.

By comparing income supplementation and early education policy effect sizes, we do not mean to imply that the two kinds of programs serve the same purpose. Child development is the explicit target of educational interventions, but it is only one of many possible goals for income redistribution policies. Ensuring school readiness for all children probably requires that some receive preschool education intervention programs, independent of whatever income redistribution program might be present.

What might account for these income effects? One possibility is that higher incomes might reduce parental stress, which in turn might improve parenting (McLoyd, 1998). However, a review of the original impact reports for these studies shows that the earnings supplement programs failed to boost parenting warmth, monitoring, or provision of learning experiences in the home, nor did they consistently reduce parental harshness or depression (Duncan, Gennetian, & Morris, 2007; Morris, Huston, Duncan, Crosby, & Bos, 2001). Nor were there consistent impacts on marriage and cohabitation. The absence of effects on the home environment and parenting may be due to the fact that the increases in income were accompanied by increases in employment, offsetting any potential benefits of reduced financial strain with increased time pressure, a point to which we return later. Moreover, a few of the studies showed that the increased income was spent on child care, clothing, and food for children, which may simply not have been sufficient to reduce the strain of low income and result in measurable changes in parents’ behavior and emotional well-being.

Another possibility is that some of the earnings supplement programs increased parents’ use of center-based child care arrangements. In fact, research conducted on these same samples has indeed suggested that programs that increase children's participation in center-based care arrangements also increase children's school achievement (Gennetian, Crosby, Dowsett, & Huston, 2007; Morris, Gennetian, & Duncan, 2005). Analyses parallel to those reported here have shown that that use of center-based care, as opposed to care in someone's home, during a child's preschool years has a positive effect on school achievement in the early grades of elementary school (Gennetian et al., 2007). In the Gennetian et al. (2007) research, effect sizes were modest but comparable to those for income—a .10 increase in probability of being exclusively in center-based care during the preschool years increased achievement by about 10% of a standard deviation.

It is also likely that families use extra income to improve the quality of child care for their children. In this way, income-induced child care changes are separate from child care changes induced by the program directly (e.g., by encouraging families to take up a different kind of care without changing their income level). That is, the income effects on children can be viewed in a path model context: If money were truly randomly assigned, then some of that money might be spent on higher quality child care, reductions in work to spend more time with children, better health care, or a host of other ways. This article is focused on estimating the total effects of income itself. Estimating the process model behind these total effects is an important research priority but not the focus of the current article.

Several caveats apply to our study. First, our data were drawn from children growing up in single-parent low-income families, precluding our ability to generalize to other family types and socioeconomic levels. Second, in pooling our data across sites, we assumed similarity in the ways in which income affected children across our studies and sites, an assumption that might not be met with the Canadian vs. U.S. data or for diverse sites across the United States. Notably, our individual study estimates suggest similarity in effects of income across sites, providing some justification for pooling these data.

Finally, because we used earnings supplement programs to generate our effects of income on child achievement, our findings are likely most germane to income-boosting policies that link increases in income to increases in employment. Although we controlled for employment hours in all of these models, there may be psychological benefits to increases in earned but not other sources of income. To the extent that these benefits were part of our income effects, our results are most relevant to income increases arising from earnings supplements as opposed to policies providing cash grants not tied to work (such as child allowances). But of course this matters a great deal from a policy perspective.

Although many studies have attempted to estimate the effects of income on children's development, few have relied on experimental or quasiexperimental variation in income. As such, our findings contribute to ongoing debates on whether and how much policy-induced increases in family income have a causal effect on the school achievement of preschool children (Blau, 1999; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Haveman & Wolfe, 1995; Jacob & Ludwig, 2007; Mayer, 1997). The effects reported here are compelling and informative for guiding developmental theory as well as future income-support policies. The extent to which such effects hold up under slightly varying economic contexts, evolving and more stringent welfare-to-work policies, or compositional changes among low-income workers is an open question that should guide future research in efforts to inform research and policy.

Acknowledgments

This article was completed as part of the Next Generation project, which examines the effects of welfare, antipoverty, and employment policies on children and families. This article was funded by the Next Generation Project funders—the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation—and by Grant R01HD045691 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank the original sponsors of the studies for permitting reanalyses of the data; Nina Castells, Beth Clark-Kauffman, Heather Hill, Ginette Azcona, and Francesca Longo for analytical and research assistance; Joshua Angrist, Raquel Bernal, Dan Black, David Blau, David Card, David Ellwood, Christopher Jencks, Jeffrey Kling, Steven Levitt, Sara McLanahan, Robert Moffitt, Stephen Raudenbush, and Chris Taber for thoughtful comments on earlier versions.

Footnotes

Authors are listed alphabetically to reflect equal contribution to this work.

Results in Table 3 are based on ordinary least squares regressions, with a cluster adjustment to account for the fact that in some cases there are multiple achievement reports per child and multiple children per family. In doing so, we allowed for nonindependence between both within-child and within-sibling measurements but did not specify the relative amount of shared variance in each.

Adding baseline characteristics to this model increased the precision of the estimate and changed the coefficients slightly. Thus, this slope was slightly different from the IV estimate of the coefficient on income reported in the analyses that follow.

These OLS estimates are somewhat smaller than those reported in the nonexperimental literature and are much smaller in magnitude than the IV estimates we report. Part of the explanation is the unusual nature of our samples of parents, some of whom relied extensively on welfare whereas others’ incomes consisted mostly of earnings. OLS analysis of the separate effect on achievement of income from earnings and welfare showed the expected positive effect of earnings on child achievement but a similar-sized negative coefficient on welfare income. We suspect that the negative effect of welfare income reflects unmeasured characteristics of high welfare-recipient mothers and their families. Of course, the earnings coefficient may be upwardly biased by positive unobservables. At any rate, our IV estimates should be purged of this kind of omitted-variable bias.

The linear model assumes that, say, a $1,000 increment to family income has the same effect on achievement for a family with a $5,000 income as for one with a $20,000 income. The logarithmic model presumes equal proportionate effect (e.g., that a 50% increase of $2,500 in average income from $5,000 to $7,500 has the same effect as the 50% increase of $10,000 in average income from $20,000 to $30,000. A one-unit change in log income is a 2.7-fold increase in child achievement—quite a large effect.

There were too few studies that included data on teacher report to conduct our analysis using only this outcome measure of child achievement.