Abstract

The involvement of the recently characterized 5′ exonuclease activity of RNase J1 and endonuclease activity of RNase Y in the turnover of ΔermC mRNA in Bacillus subtilis was investigated. Evidence is presented that both of these activities determine the half-life of ΔermC mRNA.

TEXT

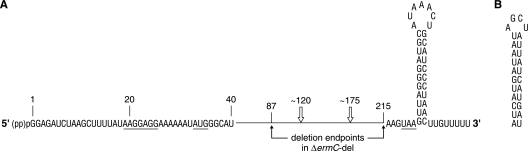

The 260-nucleotide (nt) ΔermC mRNA (Fig. 1A) has served as a useful model for determining the effects of structural and translational elements on mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis (1, 16, 17, 20). The involvement of the essential RNase J1, a bifunctional enzyme that has both endonuclease and 5′ exonuclease activities (10, 12), in ΔermC mRNA decay was reported previously (20): the half-life of ΔermC mRNA increased 2.5-fold, from 7.5 min to 18.5 min, in an RNase J1-limited strain. The terms “RNase J1-” and “RNase Y-limited strain” refer to strains in which expression of the particular RNase is under pspac promoter control, which results in an RNase concentration severalfold lower than that in the wild-type strain (7). A 130-nt derivative of ΔermC mRNA, which had an in-frame deletion of nt 87 to 215 and which we call here ΔermC-del (Fig. 1A), showed a 2-fold increase in half-life in the wild-type strain (14.6 min). This result indicated strongly that exonucleolytic degradation by RNase J1 from the 5′ end could not account completely for ΔermC mRNA turnover, as this mode of decay was unlikely to be affected by an internal deletion. We hypothesized that one or more RNase J1 endonuclease cleavage sites were located between nt 87 and 215 and that deletion of this sequence increased half-life by eliminating these decay initiation sites. Whether exonucleolytic degradation by RNase J1 from the 5′ end also contributed to determining the half-life of the native transcript was not investigated. At the time of this study, we were unaware of the existence of RNase Y, a recently discovered essential endoribonuclease (5, 15) that may be even more important than RNase J1 for turnover of bulk mRNA (15). Here, we address the roles of RNase J1 5′ exonuclease activity and RNase Y endonuclease activity in ΔermC mRNA decay.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of ΔermC mRNA. Translational signals are underlined. Open arrows above the schematic show approximate positions of putative RNase Y cleavage sites that would generate the two major 3′-terminal decay intermediates indicated by carets in Fig. 2. The mRNA is shown with either a monophosphate or a triphosphate at the 5′ end. Endpoints of the deletion within ΔermC mRNA that gave ΔermC-del mRNA are shown. (B) Sequence and predicted structure of the 5′SS mRNA stabilizer.

The effect of RNase Y on ΔermC mRNA half-life was determined in an RNase Y-limited strain (15). Northern blot analysis, performed as described previously (19), showed that reduction of RNase Y levels resulted in an almost 2-fold increase in ΔermC mRNA half-life (7.5 min to 13.8 min; Table 1). Thus, in addition to RNase J1, RNase Y is also involved in determining ΔermC mRNA stability.

Table 1.

ΔermC mRNA half-lives in wild-type and RNase mutant strains

| mRNA | Half-life (min)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | J1 mutant | Y mutant | |

| ΔermC | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 18.5 ± 2.8 | 13.8 ± 1.7 |

| ΔermC-del | 14.6 ± 1.6 | >30 | 15.0 ± 0.7 |

| 5′SS-ΔermC | 18.3 ± 1.3 | 14.9 ± 1.7 | 31.9 ± 2.8 |

| 5′SS-ΔermC-del | >45 | ||

Values are the averages ± SD of results from three determinations.

We next measured the effect of RNase Y on the half-life of ΔermC-del mRNA and found that it was unchanged from that of the wild-type strain (14.6 min and 15.0 min; Table 1). This suggested that the deleted sequence (nt 87 to 215) in ΔermC-del mRNA contained one or more RNase Y cleavage sites; deletion of this sequence gave an mRNA that was no longer targeted by RNase Y.

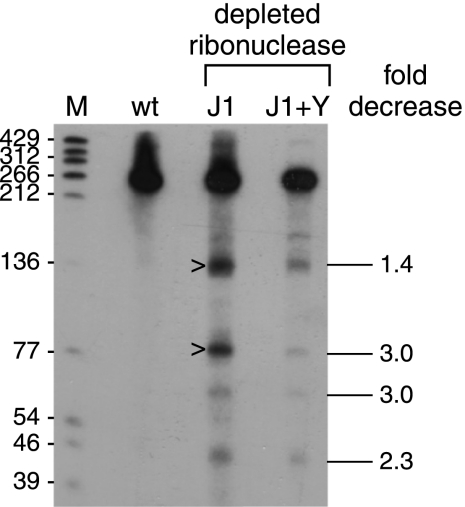

We showed previously that prominent ΔermC mRNA decay intermediates of <140 nt could be detected with a 3′-proximal probe in the RNase J1-limited strain, although not in the wild-type strain (20). We hypothesized that these fragments were generated by endonuclease cleavages at around nt 120 and 175 and were degraded rapidly in the wild-type strain by RNase J1 in the 5′-to-3′ direction. The approximate locations for two cleavage sites are indicated in Fig. 1A, and the resultant decay intermediates are indicated by carets in Fig. 2. As the current results indicated that RNase Y was initiating decay by endonuclease cleavage between nt 87 and 215, we tested whether RNase Y was involved in generating these 3′ fragments. The levels of 3′-terminal decay intermediates were compared in strains that were RNase J1 depleted and expressed either wild-type or decreased levels of RNase Y (Fig. 2). The results showed that decreased RNase Y levels resulted in a decreased level of 3′-terminal decay intermediates. Thus, we concluded that RNase Y makes endonucleolytic, decay-initiating cleavages in the region between nt 87 and 215.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of ΔermC mRNA decay fragments probed with a 36-nt 3′-terminal probe that was complementary to ΔermC mRNA nt 205 to 240. The strain types are indicated above each lane: wt, wild type; J1, RNase J1 limited; J1+Y, RNase J1 and RNase Y limited. Marker lane M contained 5′-end-labeled TaqI fragments of plasmid pSE420 DNA (2), with the sizes of these fragments indicated on the left. On the right is the fold decrease of each of four prominent decay intermediates in the J1+Y lane relative to the J1 lane and normalized to the amount of full-length RNA (average of results from four experiments).

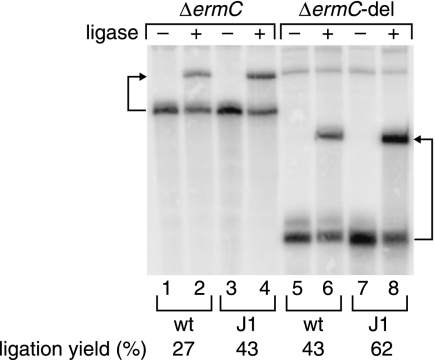

The half-life of ΔermC-del mRNA, which was 2-fold greater than that of ΔermC in the wild-type strain, was increased at least another 2-fold in the RNase J1-limited strain (to >30 min) (Table 1), suggesting that additional RNase J1 target sites outside the 87-to-215-nt region were present on ΔermC-del mRNA (20). The endpoint of the 87-to-215-nt deletion is just three nucleotides upstream of the ΔermC stop codon (Fig. 1A), which is followed immediately by an extremely strong transcriptional terminator stem-loop structure (ΔG0 = −24.1 kcal/mol). For this reason, it was considered unlikely that the sequence downstream of the ΔermC-del open reading frame (ORF) was a target site for RNase J1 cleavage. Rather, RNase J1 could cleave endonucleolytically at one or more sites between positions +1 and +87 (see below) or could degrade exonucleolytically from the 5′ end. To examine the latter possibility, a splinted ligation assay (PABLO) specific for 5′ ends bearing a single phosphate (3) was used to determine the level of monophosphorylation at the 5′ end of ΔermC mRNA. We reasoned that a decrease in the level of 5′ exonucleolytic activity in the RNase J1-limited strain would result in an increase in the relative abundance of monophosphorylated 5′ ends, which are uniquely capable of undergoing ligation to an oligonucleotide in the PABLO assay. The results shown in Fig. 3 reveal that the ligation yield for ΔermC mRNA, which was 27.4% in the wild-type strain, increased ∼1.5-fold to 42.5% in the RNase J1-limited strain. (Note that the ligation yield depends not only on the percentage of 5′ ends that are monophosphorylated but also on the ligation efficiency. Ligation efficiencies are typically only 50% to 80% [4]. Thus, the ligation yields for ΔermC mRNA in vivo likely reflect an even higher percentage of 5′-monophosphorylated mRNA.) The increase in ligation yield for ΔermC mRNA in the RNase J1-limited strain is best explained by a reduction in 5′ exonuclease activity that removes the 5′-terminal, ligatable nucleotide. In addition, the reduction in RNase J1 activity should result in a larger amount of ΔermC mRNA, and this is observed (Fig. 3, lane 3 versus lane 1).

Fig. 3.

PABLO analysis of the extent of 5′-monophosphorylation of ΔermC and ΔermC-del mRNAs in wild-type and RNase J1-limited cells. Details of the oligonucleotides used in the assay are as described previously (14). Arrows point from each transcript to its ligation product.

A similar result was observed for ΔermC-del mRNA, with a ligation yield of 42.7% in the wild-type strain that increased ∼1.5-fold to 62.1% in the RNase J1-limited strain (Fig. 3), as well as an increased level of the transcript (Fig. 3, lane 7 versus lane 5). The high ligation yields for ΔermC-del mRNA, relative to those of ΔermC mRNA, in wild-type cells were expected since monophosphorylated ΔermC-del mRNA is degraded more slowly and this should result in a higher ligation yield (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We conclude that a substantial fraction of ΔermC mRNA is 5′-monophosphorylated and that this intermediate is degraded by RNase J1, whose 5′ exonuclease activity is known to be blocked by a triphosphorylated 5′ end (9, 11, 14). Thus, the increased stability of ΔermC and ΔermC-del mRNAs in the RNase J1-limited strain is likely due to diminished exonucleolytic decay from the 5′ end. This conclusion is consistent with the prolonged lifetime of ΔermC mRNA in cells lacking RppH, the enzyme that converts triphosphorylated 5′ ends to monophosphorylated 5′ ends (14).

To test whether access to the 5′ end was required for determining ΔermC mRNA half-life, we constructed a derivative, called 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA, which contained a 26-nt stabilizer sequence at the 5′ terminus (Fig. 1B). This sequence is capable of forming a strong secondary structure (ΔG0 = −10.0 kcal/mol) and has been shown in other contexts to function as a 5′ stabilizer (13, 18). The addition of the 5′SS to ΔermC mRNA substantially increased the half-life in the wild-type strain to 18.3 min (Table 1). The presence of a 5′-terminal structure is known to inhibit the pyrophosphohydrolase activity needed to convert the 5′-triphosphate end of a native transcript to a 5′-monophosphate end (8, 14); thus, the 5′ end of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA should be primarily triphosphorylated. Since RNase J1 5′ exonuclease activity is blocked by the presence of a 5′-triphosphate (9, 11, 14), we predicted that the half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA would not be affected by lowering RNase J1 levels. This was indeed the case: the half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA in the RNase J1-limited strain was 14.9 min (Table 1), not significantly different from the half-life in the wild-type strain (P value of 0.02). Thus, RNase J1 was not involved in determining the half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA, suggesting that the 5′ end of ΔermC is the major, if not only, decay-initiating target for RNase J1. By primer extension analysis of ΔermC mRNA, we found previously in the RNase J1-limited strain a minor 5′ end at the +10 position (19), and it has been suggested that this may be due to endonucleolytic cleavage by a different RNase (6). We found that the amount of this “+10 band” decreased severalfold in the 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA construct (data not shown), suggesting that it may represent a minor block to RNase J1 5′ exonuclease degradation.

On the other hand, we found that depletion of RNase Y significantly increased the half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA. The half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA increased from 18.3 min in the wild-type strain to 31.9 min in the RNase Y-limited strain (Table 1). This was likely due to decreased cleavage by RNase Y in the 87-to-215-nt region. A prediction of this hypothesis was that adding the same 5′ stem structure to ΔermC-del mRNA, which would render it resistant to RNase J1 activity at the 5′ end, in addition to being devoid of internal RNase Y target sites, should result in an extremely stable mRNA, even in the wild-type strain. This prediction was verified, as shown in Table 1. There was virtually no decrease in the amount of 5′SS-ΔermC-del mRNA, even at the latest time point (45 min).

Shahbabian and colleagues have reported that RNase Y activity is sensitive to the 5′ phosphorylation state, with 20-fold more activity in vitro on substrates containing a 5′-monophosphate end than a 5′-triphosphate end (15). Here, we find that the half-life of 5′SS-ΔermC mRNA, whose 5′ end is likely to be substantially in the triphosphorylated form, was still dependent on RNase Y. This suggests that, in vivo, RNase Y does not absolutely require a 5′-monophosphate end for access to an internal cleavage site that is important for determining half-life.

In summary, the model ΔermC mRNA has been used to obtain evidence for both RNase J1-mediated exonucleolytic and RNase Y-mediated endonucleolytic activities in the turnover of a single mRNA. We hypothesize that such cooperation is likely to occur in the decay of many B. subtilis mRNAs. Efforts to extend our findings from model RNAs to the B. subtilis transcriptome are under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants GM48804 (D.H.B.) and GM35769 (J.G.B.) from the National Institutes of Health.

The assistance of Gintaras Deikus in preparing Fig. S1 is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 9 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bechhofer D. H., Wang W. 1998. Decay of ermC mRNA in a polynucleotide phosphorylase mutant of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5968–5977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brosius J. 1992. Compilation of superlinker vectors. Methods Enzymol. 216:469–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Celesnik H., Deana A., Belasco J. G. 2007. Initiation of RNA decay in Escherichia coli by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Mol. Cell 27:79–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Celesnik H., Deana A., Belasco J. G. 2008. PABLO analysis of RNA 5′-phosphorylation state and 5′-end mapping. Methods Enzymol. 447:83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Commichau F. M., et al. 2009. Novel activities of glycolytic enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: interactions with essential proteins involved in mRNA processing. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8:1350–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Condon C. 2010. What is the role of RNase J in mRNA turnover? RNA Biol. 7:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daou-Chabo R., Mathy N., Benard L., Condon C. 2009. Ribosomes initiating translation of the hbs mRNA protect it from 5′-to-3′ exoribonucleolytic degradation by RNase J1. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1538–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deana A., Celesnik H., Belasco J. G. 2008. The bacterial enzyme RppH triggers messenger RNA degradation by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Nature 451:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deikus G., Condon C., Bechhofer D. H. 2008. Role of Bacillus subtilis RNase J1 endonuclease and 5′-exonuclease activities in trp leader RNA turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 283:17158–17167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Even S., et al. 2005. Ribonucleases J1 and J2: two novel endoribonucleases in B. subtilis with functional homology to E. coli RNase E. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:2141–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Zig L., Jamalli A., Putzer H. 2008. Structural insights into the dual activity of RNase J. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathy N., et al. 2007. 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity in bacteria: role of RNase J1 in rRNA maturation and 5′ stability of mRNA. Cell 129:681–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohki R., Tateno K. 2004. Increased stability of bmr3 mRNA results in a multidrug-resistant phenotype in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186:7450–7455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richards J., et al. 2011. An RNA pyrophosphohydrolase triggers 5′-exonucleolytic degradation of an mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell 43:940–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shahbabian K., Jamalli A., Zig L., Putzer H. 2009. RNase Y, a novel endoribonuclease, initiates riboswitch turnover in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 28:3523–3533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharp J. S., Bechhofer D. H. 2005. Effect of 5′-proximal elements on decay of a model mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 57:484–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharp J. S., Bechhofer D. H. 2003. Effect of translational signals on mRNA decay in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:5372–5379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yao S., Bechhofer D. H. 2009. Processing and stability of inducibly expressed rpsO mRNA derivatives in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 191:5680–5689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yao S., Blaustein J. B., Bechhofer D. H. 2008. Erythromycin-induced ribosome stalling and RNase J1-mediated mRNA processing in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1439–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yao S., Sharp J. S., Bechhofer D. H. 2009. Bacillus subtilis RNase J1 endonuclease and 5′ exonuclease activities in the turnover of ΔermC mRNA. RNA 15:2331–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.