Abstract

Recent experience in evaluating large-scale global health programmes has highlighted the need to consider contextual differences between sites implementing the same intervention. Traditional randomized controlled trials are ill-suited for this purpose, as they are designed to identify whether an intervention works, not how, when and why it works. In this paper we review several evaluation designs that attempt to account for contextual factors that contribute to intervention effectiveness. Using these designs as a base, we propose a set of principles that may help to capture information on context. Finally, we propose a tool, called a driver diagram, traditionally used in implementation that would allow evaluators to systematically monitor changing dynamics in project implementation and identify contextual variation across sites. We describe an implementation-related example from South Africa to underline the strengths of the tool. If used across multiple sites and multiple projects, the resulting driver diagrams could be pooled together to form a generalized theory for how, when and why a widely-used intervention works. Mechanisms similar to the driver diagram are urgently needed to complement existing evaluations of large-scale implementation efforts.

ملخص

لقد أوضحت الخبرات الحديثة النابعة من تقييم البرامج الصحية الجاري تطبيقها على نطاق واسع الحاجة إلى مراعاة التباين في المعلومات الأساسية بين مواقع تنفيذ نفس التدخل. ولا يصلح استخدام التجارب التقليدية ذات الشواهد المختارة عشوائياً لهذا الغرض، لأنها مصممة كي تستكشف إذا كان التدخل يعمل أم لا، ولكنها لا تستكشف كيف أو متى أو لماذا يعمل هذا التدخل. وفي هذه الورقة، راجع الباحثون العديد من تصاميم التقييم التي حاولت شرح عوامل المعلومات الأساسية التي تساهم في فعالية التدخل. وباستخدام هذه التصميمات كأساس، اقترح الباحثون مجموعة من المبادئ يمكنها أن تساعد في الاستحواذ على المعلومات حول تلك المعلومات الأساسية. وفي النهاية، اقترح الباحثون أداة، تسمى مخطط القيادة، ويُستخدم عادة في التنفيذ كي يتيح لمن يجرون التقييم الرصد المنهجي للتغيرات الديناميكية في تنفيذ المشروع، والتعرف على التباين في المعلومات الأساسية للمواقع. ووصف الباحثون مثالاً مرتبطاً بالتنفيذ في جنوب أفريقيا للتأكيد على مواطن قوة هذه الأداة. والتي إذا استخدمت في العديد من المواقع والمشاريع المتعددة، فإن المخططات القيادية الناتجة عنها يمكن تجميعها لتشكيل نظرية عامة حول كيف ومتى ولماذا يعمل التدخل الجاري تطبيقه على نطاق واسع. وهناك حاجة إلى آليات مشابهة للمخطط القيادي على وجه السرعة لاستكمال التقييمات الجارية لجهود التنفيذ الواسعة النطاق.

Résumé

De récentes expériences d’évaluation des programmes sanitaires mondiaux à grande échelle ont mis en évidence le besoin d’examiner les différences contextuelles entre les sites mettant en œuvre la même intervention. Les essais contrôlés aléatoires traditionnels conviennent mal à cet objectif car ils sont conçus pour déterminer si une intervention fonctionne, et non pas comment, quand et pourquoi elle fonctionne. Dans cet article, nous analysons plusieurs projets d’évaluation qui tentent d’expliquer les facteurs contextuels contribuant à l’efficacité de l’intervention. En nous basant sur ces projets, nous proposons un ensemble de principes susceptibles de saisir des informations sur le contexte. Enfin, nous proposons un outil appelé graphique de pilotage, généralement utilisé lors de l’implémentation, qui permettrait aux experts de contrôler de façon systématique l’évolution de la dynamique dans la mise en œuvre du projet et d’identifier la variation contextuelle entre les sites. Nous décrivons un exemple de mise en œuvre en Afrique du Sud pour mettre en évidence les points forts de l’outil. Lors de leur utilisation sur plusieurs sites et dans le cadre de projets multiples, les graphiques de pilotage générés pourraient être rassemblés pour constituer une théorie généralisée permettant de comprendre comment, quand et pourquoi une intervention à grande échelle fonctionne. Des mécanismes semblables au graphique de pilotage constituent un besoin urgent pour compléter les évaluations existantes des d’efforts de mise en œuvre à grande échelle.

Resumen

La experiencia reciente en la evaluación de programas de salud mundial a gran escala ha puesto de relieve la necesidad de considerar las diferencias contextuales entre los centros que implementan la misma intervención. Los tradicionales ensayos controlados aleatorizados no son la herramienta más adecuada para este propósito, ya que están diseñados para identificar si una intervención funciona, no para identificar cómo, cuándo y por qué funciona. En este artículo se revisan varios diseños de evaluación que intentan explicar los factores contextuales que contribuyen a la eficacia de la intervención. Tomando estos diseños como base, se propone un conjunto de principios que pueden ayudar a recopilar información sobre el contexto. Por último, proponemos una herramienta, llamada esquema conceptual, tradicionalmente aplicada durante la implementación, que permitiría a los evaluadores realizar un seguimiento sistemático de la dinámica cambiante en la implementación del proyecto e identificar la variación contextual entre los diferentes centros. Se describe un ejemplo de implementación en Sudáfrica con el objetivo de subrayar los puntos fuertes de la herramienta. Si se utilizan en varios centros y múltiples proyectos, los esquemas conceptuales resultantes se podrían combinar para formular una teoría generalizada sobre cómo, cuándo y por qué funciona una intervención ampliamente utilizada. Existe una necesidad urgente de desarrollar mecanismos similares al esquema conceptual que complementen las evaluaciones existentes de los esfuerzos de implementación a gran escala.

摘要

近期评估大型全球健康计划的经验已经突出表明了在实施同一干预措施的地区之间要考虑环境差异的必要性。传统的随机对照试验并不适用于此目的,因为这些试验是设计用来确定干预措施是否可行,而不是如何、何时和为何可行。本文中,我们对试图解释促进干预有效性的环境因素的若干评估设计进行综述。以这些设计为基础,我们提出了一组可帮助捕捉环境信息的原理。最后,我们提议运用传统上用于计划实施的一种称之为驱动因素图解的工具,这一工具能够使评估者对项目实施过程中的变化进行系统动态监测并识别各地区的环境差异。我们描述了南非与计划实施相关的例子以显现这一工具的优点。如果这一工具用于多个地区和多个项目,则由此产生的驱动因素图解可以汇集在一起,形成关于一个被广泛应用的干预措施如何、何时且为何实施的广义理论。目前迫切需要与驱动因素图解类似的机制以弥补对大规模实施效果的现有评估。

Резюме

Новейший опыт оценки крупномасштабных программ в области здравоохранения свидетельствует о необходимости учитывать различия условий между объектами, где внедряется одна и та же мера вмешательства. Традиционные рандомизированные контролируемые испытания плохо приспособлены для этой цели, поскольку предназначены для выявления того, работает ли мера вмешательства вообще, а не того, как, когда и почему она работает. В данной статье мы проводим обзор ряда планов оценки, в которых учитываются факторы условий, способствующие повышению эффективности меры вмешательства. Используя эти планы в качестве основы, мы предлагаем набор принципов, которые могут помочь собрать информацию о местных условиях. В заключение мы предлагаем инструмент, традиционно используемый в процессе внедрения, под названием «диаграмма драйверов», который позволит специалистам, проводящим оценку, систематически отслеживать изменения динамики внедрения проекта и выявлять вариации условий на различных объектах. Чтобы продемонстрировать положительные стороны инструмента, мы описываем опыт ЮАР, связанный с внедрением одной из инициатив. Если применять данный инструмент сразу к нескольким объектам и проектам, можно свести воедино результирующие диаграммы драйверов в форме обобщенного теоретического вывода о том, как, когда и почему используемая в широких масштабах мера вмешательства оказывается эффективной. Для дополнения существующих оценок крупномасштабных мер вмешательства настоятельно необходимы механизмы, аналогичные диаграммам драйверов.

Challenges of evaluation

In January 2010, a retrospective evaluation of the United Nations Children’s Fund’s multi-country Accelerated Child Survival and Development programme was published in the Lancet.1 The authors found great variation in effectiveness of the programme’s 14 interventions and could not account for the causes of these differences.2 The journal’s editors wrote that “evaluation must now become the top priority in global health” and called for a revised approach to evaluating large-scale programmes to account for contextual variation in timing, intensity and effectiveness.3–6

Evaluations of large-scale public health programmes should not only assess whether an intervention works, as randomized designs do, but also why and how an intervention works. There are three main reasons for this need.

First, challenges in global health lie not in the identification of efficacious interventions, but rather in their effective scale-up.7 This requires a nuanced understanding of how implementation varies in different contexts. Context can have greater influence on uptake of an intervention than any pre-specified implementation strategy.3 Despite widespread understanding of this, existing evaluation techniques for scale-up of interventions do not prioritize an understanding of context.5,7

Second, health systems are constantly changing, which may influence the uptake of an intervention. To better and more rapidly inform service delivery, ongoing evaluations of effectiveness are needed to provide implementers with real-time continuous feedback on how changing contexts affect outcomes.7,8 Summative evaluations that spend years collecting baseline data and report on results years after the conclusion of the intervention are no longer adequate.

Finally, study designs built to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention in a controlled setting are often mistakenly applied to provide definitive rulings on an intervention's effectiveness at a population level.9,10 These designs, including the randomized controlled trial (RCT), are primarily capable of assessing an intervention in controlled situations that rarely imitate “real life”. The findings of these studies are often taken out of their contexts as proof that an intervention will or will not work on a large-scale. Instead, RCTs should serve as starting points for more comprehensive evaluations that account for contextual variations and link them to population-level health outcomes.5,11–18

The need for new evaluation designs that account for context has long been recognized.18–21 Yet designs to evaluate effectiveness at scale are poorly defined, usually lack control groups, and are often disregarded as unsatisfactory or inadequate.4 Recent attempts to roll out interventions across wide and varied populations have uncovered two important problems: first, the need for a flexible, contextually sensitive, data-driven approach to implementation and, second, a similarly agile evaluation effort. Numerous authors have proposed novel frameworks and designs to account for context, though few have been tested on a large scale.22–25 Moreover, these frameworks have tended to focus on theories to guide evaluations rather than concrete tools to assist evaluators in identifying and collecting data related to context. In this paper, we review these proposals, present guiding principles for future evaluations and describe a tool that aims to capture contextual differences between health facilities as well as implementation experiences, and may be useful when considering how to best scale up an intervention.

Context-sensitive designs

Several evaluation designs have been proposed in response to the need to understand context in study settings (Table 1). Some of these designs are based on RCTs with changes to allow for greater flexibility. The adaptive RCT design allows for adjustment of study protocols at pre-determined times during the study as contextual conditions change.14,37 Alternatively, the pragmatic RCT design explicitly seeks to mirror real-world circumstances, especially in selecting participants that accurately reflect the broader demographics of patients impacted by the intervention.14,37 Additionally, Hawe et al. propose supplementing RCTs with in-depth qualitative data collection to better understand variations in results.22 Each of these approaches has the potential to expand the explanatory reach of the RCT design and apply its strengths to questions of programme effectiveness and scale-up.

Table 1. Overview of context-specific evaluation designs.

| Evaluation design | Key components |

|---|---|

| Alternative randomized controlled trials22,26 | Randomized design with flexible protocols to allow for variation, real-world complications and greater external validity. |

| Realist evaluation27–29 | Approach designed to understand the interaction between the intervention in question and the context in which it is introduced. Theory building and case study methods are emphasized, though realist evaluation does not rely on a fixed methodology. |

| Evaluation platform design7 | Aims to assess effectiveness at scale and the contribution of a large-scale programme towards achieving broad health goals. Takes the district as the primary unit of analysis and relies on continuous monitoring of multiple levels of indicators. |

| Process evaluation16,30,31 | Assesses the actual implementation of a programme by describing the process of implementation and assessing fidelity to programme design. Relies on various tools to map processes, including logic models and programme impact pathways. |

| Multiple case study design32–34 | Applies case-study methodology to several subjects with the goal of understanding the complexities of a programme from multiple perspectives. Information is gathered through direct (e.g. interviews and observations) and indirect (e.g. documentation and archival records) means. |

| Interrupted time series design35,36 | Uses multiple data points over time, both before and after an intervention, to understand whether an intervention’s effect is significantly different from existing secular trends. |

In contrast to alternative RCT designs, theory-based evaluation has been proposed to further understand the actual process of change that an intervention seeks to produce.25,38 The most prominent example of theory-based evaluation is Pawson & Tilley’s “realistic evaluation” framework, which is best summarized by the equation “context + mechanism = outcome”.17 This framework suggests that the impact (“outcome”) of an intervention is the product of the pathway through which an intervention produces change (its “mechanism”) and how that pathway interacts with the target organization’s existing reality (“context”).

Victora et al. have proposed an “evaluation platform” design that aims to evaluate the impact of large-scale programmes on broad objectives, such as the United Nations Millennium Development Goals. This approach treats the district as the central unit of analysis and involves the continuous gathering of data from multiple sources which are analysed on a regular basis.7 The design begins with the creation of a conceptual model on which data collection and analysis are based, in line with the theory-based approach. The focus on ongoing data collection also resonates with the work of Alex Rowe, who has advocated for integrated continuous surveys as a means to monitor programme scale-up.8

Alongside these newly proposed evaluation frameworks, some commonly used methodologies have the potential to answer questions of contextual variation. Process evaluations, for example, are increasingly focused on understanding local context rather than simply assessing if each stage of the implementation itself was successful.16,22 Process evaluations use several tools and frameworks, including programme impact pathways and results chain evaluations.39 Interrupted time series designs also provide an opportunity to understand the effects of sequentially introduced interventions and their interactions with the local environment. These designs have been used in large, multi-pronged studies, in addition to smaller scale applications in conjunction with statistical process control analytic methods.40 Multiple case study research also provides a method to study the impact of an intervention on specific individuals (or other units of analysis), allowing researchers to analyse particular drivers behind successful or failed implementation at a local level.41,42

A context-sensitive approach

Each of these approaches attempts to respond to the need to identify and collect local contextual data.4,5,7,15,17,20,23 These data will vary significantly depending on the chosen approach, and will be both quantitative and qualitative. Regardless of data type and source, however, the following principles can help guide efforts to capture data on context.

Standardized and flexible

Flexibility is an important requirement to successfully capture the role of context, and it is also the most difficult to accomplish. It requires developing new qualitative and quantitative approaches, metrics and reliable data collection processes in conjunction with implementers, supervisors and researchers. The choice of metrics will itself be an iterative process that changes during data collection. Data collection tools, however, must also maintain a degree of standardization to be comparable across contexts. This is necessary to ensure that implementers understand the “whole” of a large-scale intervention, not just its component parts.

“One level removed”

A critical question that arises when developing evaluation methods is who will collect and evaluate the data. Potential candidates range from external researchers to the implementers themselves, neither of whom can effectively capture the role of context. An external researcher will have difficulty identifying the situational factors that should be monitored and lacks the intimate knowledge of local context necessary to effectively identify variables across sites. While those actually implementing an intervention will probably possess this knowledge, their perspectives may be subject to multiple biases. We propose identifying an agent who oversees implementation across multiple sites but is still closely involved in implementation activities. This agent would be “one level removed” from the day-to-day activities of programme rollout, thus giving him/her intimate knowledge of the implementation experience without prejudicing the process. Such an agent would facilitate cross-learning and comparisons to produce more generalizable results. Using the district as the unit of analysis, as others have proposed, this individual may be a “supervisor” who visits a subset of clinics as an intervention is rolled out.7

Vetting the data

Despite the particular advantages of a “one-level removed” implementer, the possibility of bias still remains. Key variables on context will need to be validated against multiple sources. Redundancies in currently available data can be used to check on newer data collection tools as they are developed and tested. For example, identifying an inconsistent supply chain as a barrier to implementation could be validated against records of pharmaceutical stocks at facilities. This will be especially true in the early stages of data collection, before the development of formalized structures for collecting contextual data.

A new tool

With these principles in mind, we describe an evaluation tool that aims to capture contextual differences between health facilities and may help programme implementers account for different outcomes for the same intervention in diverse settings. We propose using a specific tool, known as the “driver diagram”, as the central mechanism to capture variation across implementation contexts.43

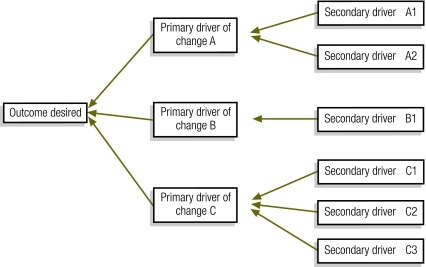

The driver diagram is a tool commonly used by implementers to understand the key elements that need to be changed to improve delivery of a health intervention in a given context.43 Beginning with the outcome or aim, an implementation team works backward to identify both the primary levers or “drivers” and the secondary activities needed to lead to that outcome (Fig. 1). Driver diagrams are used in many contexts to assist health system planners to implement change effectively.44–49

Fig. 1.

A basic driver diagram

In addition to outlining the implementation plan, local facility-based teams develop driver diagrams to help them identify key barriers to implementation and to develop measures to track process improvements to the primary and secondary drivers. The driver diagram can be revisited at predefined times throughout the implementation process, where it is adjusted to account for changes in strategies or unforeseen challenges. The goal of this process is to allow local health system actors to tap into their intimate knowledge of the changing context to more effectively facilitate the implementation process. The iterative nature of the driver diagram process allows adjustments to local context and situation so that, by the end of the implementation, there is a complete picture of that local team's implementation experience.

While driver diagrams have yet to be used specifically for evaluation, they have been widely used to guide implementation in a systematic way. An example is the 20 000+ Partnership, a regional initiative in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, that aims to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission rates to less than 5%. This project’s initial driver diagram outlined the spectrum of activities that the implementers intended to introduce. On a regular basis, implementers overseeing rollout met to discuss challenges and factors influencing success. These included the introduction of new antiretroviral medications, changes to South African national treatment policies in 2008 and 2010, the launch of a high-profile national HIV testing campaign, changes in local leadership and availability of systems infrastructure (meetings, personnel) to participate in the project.

Each of these meetings provided implementers with an opportunity to understand how local differences between participating sites lead to differences in effectiveness of the intervention activities. Over the course of the project’s implementation, the driver diagrams were modified to reflect ongoing changes (available at: http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Publications/EvalPopHealthOutcomes.aspx).

Though these models were used to guide implementation in this example, there is a clear opportunity for the use of this process in evaluation. The important characteristics that lead to differential outcomes across KwaZulu Natal could provide evaluators with information on important confounders and effect modifiers, in addition to qualitative data that could contextualize the findings of the evaluation.

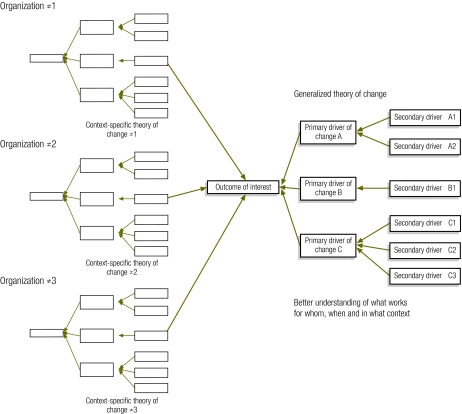

Extrapolating from this experience, several teams involved in scaling up an intervention could create local, site-specific driver diagrams and pool these together to show how to best implement that intervention (Fig. 2). This implementation theory would specify consistent findings that could be standardized as well as findings that work best when customized to the local context. Specifically, this product would include: (i) an overall driver diagram reflecting common elements of each facility-specific driver diagram; (ii) a list of diagram components that differed widely across the facility-specific diagrams; and (iii) a list of common contextual factors across the participating organizations’ experiences. This process will allow the public health community to understand the factors that need to be considered when implementing a specific intervention in any given context. Over time, as the driver diagram matures, subsequent implementation efforts would probably be more efficient and more effective.

Fig. 2.

A master driver diagram created from an aggregation of project-specific driver diagrams

Taking the concept one step further, if multiple programmes implementing the same interventions around the world pooled their information (and driver diagrams) together, the public health community could develop a more in-depth understanding of that intervention’s dynamics. We join others in proposing an approach similar to the Cochrane Collaboration, in which multiple organizations synthesize their learning in a standardized way.50 As more context-specific details are fed into this “knowledge bank”, the overall ability to implement interventions at scale will become more accurate, more nuanced and better able to inform future endeavours.

The driver diagram is not without limitations and has not traditionally been used to understand contextual barriers to implementation. Its linear nature is both a shortcoming and an asset as it provides a useful mechanism for organizing complex contextual data but perhaps over-simplifies the same in the process. Its use by programme designers and implementers makes it a useful candidate for bridging the work of implementers and evaluators. While the driver diagram is a useful place to start, we hope that this proposal will catalyse the creation of additional evaluation tools that can capture the role of context as it impacts on population-level health outcomes and draws the implementing and evaluation communities in closer relationship and dialogue.

Conclusion

New models for rapidly implementing efficacious interventions at scale are urgently needed; new ways of understanding their impact are also needed. Through the use of continuous data collection, iterative feedback loops and an acute sensitivity to contextual differences across projects, we can more thoroughly assess the population-level health impacts of interventions already proven to be efficacious in controlled research environments. Further study is needed to develop and test the tools described here in the context of real-time service delivery programmes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gareth Parry, Sheila Leatherman, Don Goldmann, Lloyd Provost and Pierre Barker for their review and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Theodore Svoronos is also affiliated with the Harvard University (Cambridge, MA, USA) and Kedar Mate is also affiliated with Weill Cornell Medical College (New York, USA).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Bryce J, Gilroy K, Jones G, Hazel E, Black RE, Victora CG. The Accelerated Child Survival and Development programme in west Africa: a retrospective evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375:572–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson S. Assessing the scale-up of child survival interventions. Lancet. 2010;375:530–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Arifeen S, Blum L, Hoque D, Chowdhury E, Khan R, Black RE, et al. Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) in Bangladesh: early findings from a cluster-randomised study. Lancet. 2004;364:1595–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker P, Twum-Danso N, Provost L. Retrospective evaluation of UNICEF's ACSD programme. Lancet. 2010;375:1521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora CG, Habicht J, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:400–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everybody's business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Victora CG, Black R, Boerma J, Bryce J. Measuring impact in the Millennium Development Goal era and beyond: a new approach to large-scale effectiveness evaluations. Lancet. 2011;377:85–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60810-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe AK. Potential of integrated continuous surveys and quality management to support monitoring, evaluation, and the scale-up of health interventions in developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:971–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Øvretveit J, Gustafson D. Using research to inform quality programmes. BMJ. 2003;326:759–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidoff F. Heterogeneity is not always noise: lessons from improvement. JAMA. 2009;302:2580–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habicht JP, Victora C, Vaughan J. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:10–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd RC, Goldmann D. A matter of time. JAMA. 2009;302:894–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luce BR, Kramer J, Goodman S, Connor J, Tunis S, Whicher D, et al. Rethinking randomized clinical trials for comparative effectiveness research: the need for transformational change. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:206–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madon T, Hofman K, Kupfer L, Glass R. Public health: implementation science. Science. 2007;318:1728–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2006;332:413–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7538.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenbroucke JP. Observational research, randomised trials and two views of medical science. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birckmayer JD, Weiss C. Theory-based evaluation in practice: what do we learn? Eval Rev. 2000;24:407–31. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0002400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth A, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilley N. Realistic evaluation: an overview In: Founding conference of the Danish Evaluation Society; September 2000. Available from: http://www.evidence-basedmanagement.com/research_practice/articles/nick_tilley.pdf [accessed 17 August 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T, Gold L. Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:788–93. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fixsen D, Naoom S, Blase K, Friedman R, Wallace F. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa: Florida Mental Health Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walshe K. Understanding what works – and why – in quality improvement: the need for theory-driven evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:57–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, Lee V, Middleton E, Richardson G, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:254–61. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Hughes J, Macfarlane F, Butler C, Pawson R. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in London. Milbank Q. 2009;87:391–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazi M. Realist evaluation for practice. Br J Soc Work. 2003;33:803–18. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/33.6.803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchal B, Dedzo M, Kegels G. A realistic evaluation of the management of a well-performing regional hospital in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fotu KF, Moodie MM, Mavoa HM, Pomana S, Schultz JT, Swinburn BA. Process evaluation of a community-based adolescent obesity prevention project in Tonga. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reelick MF, Faes MC, Esselink Ra J, Kessels RPC, Olde Rikkert MGM. How to perform a preplanned process evaluation for complex interventions in geriatric medicine: exemplified with the process evaluation of a complex falls-prevention program for community-dwelling frail older fallers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bond S, Bond J. Outcomes of care within a multiple-case study in the evaluation of the experimental National Health Service nursing homes. Age Ageing. 1990;19:11–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kegler MC, Steckler A, Malek SH, McLeroy K. A multiple case study of implementation in 10 local Project ASSIST coalitions in North Carolina. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:225–38. doi: 10.1093/her/13.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson K, Elliott SJ, Driedger SM, Eyles J, O'Loughlin J, Riley B, et al. Using linking systems to build capacity and enhance dissemination in heart health promotion: a Canadian multiple-case study. Health Educ Res. 2005;20:499–513. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillings D, Makuc D, Siegel E. Analysis of interrupted time series mortality trends: an example to evaluate regionalized perinatal care. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:38–46. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan P, Goldmann D. The promise of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2011;305:400–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers PJ. Causal models in program theory evaluation. N Dir Eval 2000. 2000:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douthwaite B, Alvarez BS, Cook S, Davies R, George P, Howell J, et al. Participatory impact pathways analysis: a practical application of program theory in research-for-development. Can J Program Eval. 2007;22:127–59. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458–64. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.6.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harvey G, Wensing M. Methods for evaluation of small scale quality improvement projects. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:210–4. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.White CM, Schoettker PJ, Conway PH, Geiser M, Olivea J, Pruett R, et al. Utilising improvement science methods to optimise medication reconciliation. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011:372–381. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.047845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryckman FC, Yelton PA, Anneken AM, Kiessling PE, Schoettker PJ, Kotagal UR. Redesigning intensive care unit flow using variability management to improve access and safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35:535–43. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryckman FC, Schoettker PJ, Hays KR, Connelly BL, Blacklidge RL, Bedinghaus CA, et al. Reducing surgical site infections at a pediatric academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35:192–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rushmer R, Voigt D. MEASURE IT, IMPROVE IT: the Safer Patients Initiative and quality improvement in subcutaneous insulin therapy for hospital in-patients. Diabet Med. 2008;25:960–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinto A, Burnett S, Benn J, Brett S, Parand A, Iskander S, et al. Improving reliability of clinical care practices for ventilated patients in the context of a patient safety improvement initiative. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:180–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Project Fives Alive (Internet site). Accra: National Catholic Secretariat; 2011.

- 50.Øvretveit J, Leviton L, Parry G. Methods to evaluate quality improvement initiatives. In: AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, Boston, MA, 22–29 June 2010 [Google Scholar]