Abstract

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS) provides the highest mass resolving power and mass measurement accuracy for unambiguous identification of biomolecules. Previously, the highest-mass protein for which FT-ICR unit mass resolution had been obtained was 115 kDa at 7 T. Here, we present baseline resolution for an intact 147.7 kDa monoclonal antibody (mAb), by prior dissociation of non-covalent adducts, optimization of detected total ion number, and optimization of ICR cell parameters to minimize space charge shifts, peak coalescence, and destructive ion cloud Coulombic interactions. The resultant long ICR transient lifetime (as high as 20 s) results in magnitude-mode mass resolving power of ~420,000 at m/z 2,593 for the 57+ charge state (the highest mass for which baseline unit mass resolution has been achieved), auguring for future characterization of even larger intact proteins and protein complexes by FT-ICR MS. We also demonstrate up to 80% higher resolving power by phase correction to yield an absorption-mode mass spectrum.

Keywords: Proteomics, top-down protein sequencing

(Introduction)

The integration of electrospray ionization (ESI)1 and ultrahigh resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS)2, 3 has facilitated confident analysis of biomolecules such as proteins,4 nucleotides,5, 6 polar lipids,7 etc. FT-ICR MS provides the highest broadband mass spectral resolving power,8 mass resolution,9, 10 and mass measurement accuracy.8, 11 Ultrahigh resolution enables charge state determination from a single charge state as well as separation of overlapped isotopic distributions for high-mass biological molecules. Higher mass accuracy improves identification confidence and increases the speed of database search for proteomics.12–14 FT-ICR MS is now widely recognized as a powerful tool for top-down proteomics,15–17 particularly for identification and characterization of intact proteins and up/down-regulation of post-translational modifications (PTMs) of proteins.

Once charge states have been resolved, the next step is to obtain unit mass resolution of large biomolecules.6, 18–23 However, Mitchell and Smith showed that cyclotron phase locking limits the highest mass at which unit mass resolution can be realized with FT-ICR MS, due to Coulombic interactions.24 Nevertheless, McLafferty and co-workers successfully unit mass-resolved a 112 kDa protein at the then-highest magnetic field (9.4 T) with 3 Da mass error.21 Twelve years later, unit FT-ICR mass resolution was reported for a cardiac myosin binding protein C (115 kDa) at 7 T.23 The multiple-charging characteristic of ESI enables detection of analytes in excess of 100 kDa by lowering the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) requirement to a range readily accessible by FT-ICR MS. Only FT-ICR MS has resolved the isotopic multiplets of an intact protein higher than 100 kDa in mass, thereby offering the prospect of resolution and identification (by MSn) of non-covalent adducts (e.g., cations, buffers, ligands) as well as posttranslational modifications (e.g., deamidation (+1 Da),25 oxidation (+16 Da),26 pyroglutamic acid formation (−17 Da), dehydration (−18 Da), sulfation, glycosylation,27 phosphorylation,23 etc.)

FT-ICR mass resolving power, m/Δm50% (in which Δm50% is mass spectral peak full width at half-maximum peak height), varies approximately inversely with m/z.2, 28 Thus, in view of FT-ICR mass resolving power, m/Δm50% = 8,000,000 achieved for ubiquitin (~8,500 Da) in 1998,29 one might expect m/Δm50% > 400,000 for a 150 kDa protein (i.e., effectively baseline unit mass resolution). However, in the last fifteen years, "nominal" (unit) mass resolution has been achieved for only three proteins whose molecular weight exceeds 100,000 Da.21, 23 Difficulties include: sample heterogeneity, cation/solvent/buffer adduction, space charge limitations30–32 and electric and magnetic field inhomogeneity.33, 34

Here, we report the highest mass protein isotopically resolved to date. Substantial redesign of our 9.4 T FT-ICR mass spectrometer,35 and improved data collection/processing capabilities36 enable unit mass resolution for an intact monoclonal antibody, based on a 20 s time-domain signal with magnitude-mode resolving power of ~420,000. The measurement also benefits from in-source collisional dissociation to remove adducts; implementation of an electrically compensated open cylindrical cell for improved DC potential tunability to reduce destructive shearing force on the ion cloud;33, 37 and phase correction to yield absorption-mode spectra with significantly higher resolving power.38–40

Methods

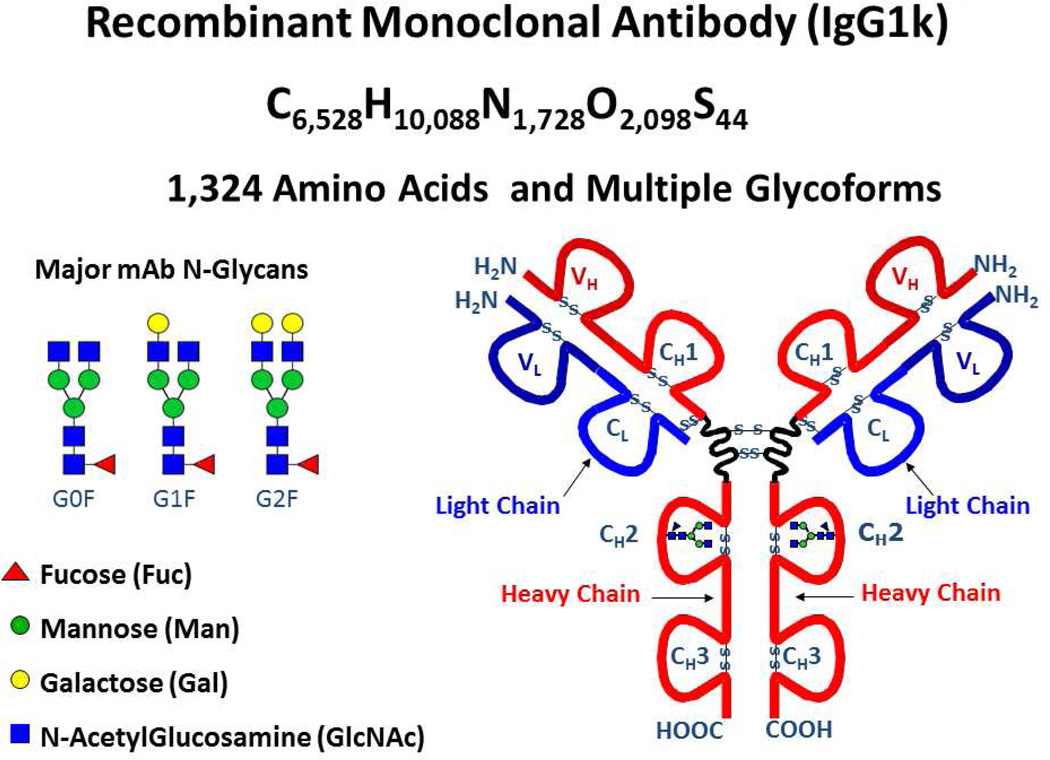

HPLC grade water and acetonitrile were purchased from J.T. Baker (Philipsburg, NJ). A recombinant, humanized IgG1k therapeutic antibody (1,324 amino acids—see Figure 1) expressed and purified by Pfizer Inc. was diluted to ~5 µM in conventional ESI solution: H2O/acetonitrile/formic acid, 50/49.5/0.5 (v/v/v).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the structure and glycoforms for recombinant monoclonal antibody, IgG1k.

The sample was micro-electrosprayed41 into a recently modified 9.4 T hybrid FT-ICR mass spectrometer35 at 400 nL/min. Positive ions formed at atmospheric pressure were transferred through different pressure chambers by rf-only octopoles (1.6 mm diameter titanium rods, 4.8 mm i.d.) operated at 1.4 MHz and 190 < Vp-p < 240 rf amplitude. Ions of a specific charge state were isolated in a mass-selective quadrupole and accumulated (1–3 s) in an external octopole ion trap42 prior to transfer to a 7 segment open cylindrical cell similar to the configuration of Tolmachev et al.33, 43 Broadband frequency sweep (chirp) dipolar excitation (720 KHz - 48 KHz) at 50 Hz/µs sweep rate accelerated the ions to a cyclotron orbital radius of approximately 45% of the cell radius. Direct-mode image current detection yielded 8–16 Mword time-domain data. Each time-domain signal acquisition was kept only if the calculated total ion abundance fell within a defined range for 125–235 averaged acquisitions ("conditional co-add").36 ICR time-domain transients were collected with a modular ICR data station (Predator),36 signal averaged, Hanning apodized, and zero-filled once prior to fast Fourier transformation to yield a magnitude-mode frequency spectrum that was converted to a mass-to-charge ratio spectrum by a two term calibration equation.30, 44

Results and Discussion

Antibody charge state distribution

Recombinant monoclonal antibodies (mAb)45 constitute a rapidly proliferating class of human pharmaceuticals because of their highly selective binding to an antigen. The amino acid sequence of the present recombinant, humanized IgG1k therapeutic antibody (1,324 amino acids) is known and our objective is to achieve isotopic resolution and confirm the molecular mass by FT-ICR MS. The antibody contains a total of sixteen intra- and inter-molecular disulfide bridges and exhibits heterogeneous N-glycosylation in each heavy chain and no modifications in the light chain. More specifically, the major N-glycoform of this IgG1k mAb, referred to as G0F/G0F, exhibits modification of Asn-299 with a core-fucosylated, asialo-, agalacto-biantennary N-linked glycan structure (G0F) on each heavy chain, as well as complete removal of the C-terminal lysine residues, which corresponds to an elemental composition of C6528H10088N1728O2098S44 and a calculated average mass (ICR-2LS) of ~147,758 Da.

No interpretable signal was observed for the antibody under typical electrospray source conditions (skimmer potential, 13 V; heated metal capillary 4.5 A, 65 V) due to adduction/interferant species. Previously reported methods of sample cleanup include infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD), and low energy and sustained off-resonance irradiation (SORI) collision-induced dissociation (CID).46–48 Here, dramatic increase in signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for IgG1k and downward shift in m/z distribution (i.e., higher charge states) was achieved by increased heat to the inlet capillary (7.5 A, 75 V) and higher skimmer voltage (56 V, which we interpret to produce declustering collisions with residual air in the first octopole). Acceleration into the second (accumulation) octopole in the presence of nitrogen gas further improved S/N by additional sample clean-up through loss of adducts. Figure 2 shows the resultant broadband charge state distribution from 47+ to 67+ (m/z 2,200 to 3,200). Because FT-ICR mass resolving power is proportional to charge state2, 49, several groups have successfully employed "supercharging" reagents to increase the charge states for various proteins.50–55 However, addition of such "supercharging" reagents did not significantly increase the charge states for IgG1k mAb.

Figure 2.

Broadband positive ESI 9.4 T FT-ICR MS mass spectrum for an IgG1k antibody protein. The characteristic charge state distribution envelope from 47+ to 67+ (m/z 2,200 – 3,200) is achieved by front-end skimmer dissociation of non-covalent adducts.

Unit mass resolution and simulation

Analysis of large intact proteins is challenging due to distribution of analyte signal over a greater number of charge states, wider isotopic distribution, and prevalence of adducts (cations, solvents, buffers, etc.), all of which decrease the signal magnitude of all measured species. Therefore, more total ions are required to define the charge state distribution. However, increased ion-ion coulombic interactions degrade FT-ICR performance due to peak coalescence and rapid loss of ion packet coherence. Therefore, we sum the data from 100+ time-domain acquisitions to accurately define the isotopic distribution while minimizing destructive coulombic interactions.56

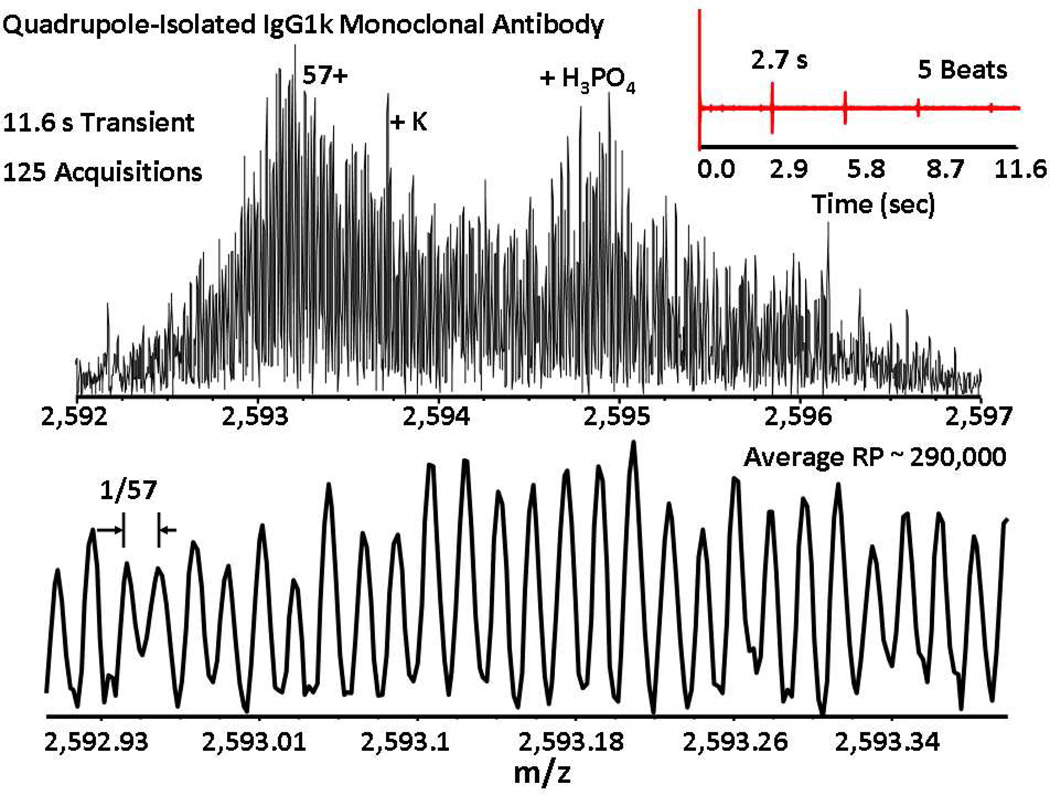

Figure 3 shows a direct infusion positive ESI FT-ICR mass spectrum for the quadrupole-isolated antibody 57+ charge state, acquired for an 11.6 s transient to yield a magnitude-mode spectrum with baseline unit mass resolution. The time-domain signal (inset) exhibits a characteristic isotopic beat pattern57 due to constructive/destructive interference between signals from different isotopomers. Optimization of the total number of trapped ions, chirp excitation rate, ion cyclotron excitation amplitude, and trapping potential improved the signal duration to attain an average resolving power of ~290,000 for 57+ charge state ions. Extension of the time-domain acquisition period to 14 s or 20 s further improves resolving power (at the cost of lower S/N and thus less accurate isotopic distribution envelope) as shown in supporting information Figures S1 and S2. The long isotopic beat period (~2.7 s) necessitates a long time-domain acquisition period to enable high mass resolution. However, cyclotron frequency can shift during a long transient, so that resolving power doesn't necessarily increase for longer time-domain acquisition period.58, 59

Figure 3.

Top: Positive ESI 9.4 T magnitude-mode FT-ICR mass spectrum for quadrupole-selected IgG1k showing 57+ charge state molecular ions along with various adducts, based on an 11.6 s transient with 5 isotopic beats (inset). Bottom: Mass scale-expanded segment, demonstrating unit mass baseline resolution of the isotopic distribution at ~290,000 average resolving power.

As mass increases, the isotopic distribution widens and the monoisotopic peak is no longer observed.60 (Although expression of a protein from a medium containing 13C-depleted glucose and 15N-depleted ammonium sulfate can dramatically increase the monoisotopic relative abundance for small proteins,61, 62 even double-depletion won't render the monoisotopic peak observable for a 150 kDa protein.) Zubarev and co-workers have shown the systematic shifts and numerous limitations of weighted abundance average mass measurements that can result in significant mass error.63, 64 Hence, the mass corresponding to the highest magnitude peak is often reported for large biomolecules.

Isotopic distribution fitting for a large biomolecule (>100 kDa) poses numerous challenges due to broad isotopic distribution (and thus reduced S/N), statistical fluctuation in ion populations, and analyte C13/C12 ratio difference from global average. Also, chemical noise due to biological heterogeneity, adducts, and neutral losses (−H2O, −NH3, −2H2O)21 can distort the wings of the experimental isotopic distribution envelope. Figure 4 shows the overlap between calculated and experimental isotopic distributions for the 57+ charge state for the antibody. Mercury algorithm (ICR-2LS program)65 was used to generate the calculated isotopic distribution based on the elemental composition. Spectral noise obviously results in variation of experimental isotopic abundance relative to calculated distribution. Here, a chi-square fit66, 67 defines the best statistical match to the experimental isotopic distribution. The highest magnitude isotopic peak differs from the predicted value by −1 Da for mAb. [Separately, the experimental data was time-domain data sampled21 to remove noise between the beats prior to fast Fourier transformation to yield a smoothed mass spectrum with 3 Da error based on the highest magnitude isotopic peak after chi-square fit (data not shown). The zeroing technique visually smooths the isotopic distribution but introduces artifacts21 (broadened isotopic distribution, slightly shifted peak positions, and mass periodicities and artificial peaks) that are being investigated further.]

Figure 4.

Calculated65 and experimental isotopic distributions for multiply-charged (57+) IgG1k molecular ions. The inset table shows the chi-square values obtained by shifting the theoretical distribution by ~1/z (i.e., 1 Da) increments to the left and right relative to the experimental distribution to locate the best fit with least error.66, 67 The calculated mass is for the unadducted antibody with two G0F glycans (see Figure 1)

Phase correction

The time delay between excitation and detection (to avoid leakage of the excitation signal into the detector) results in a mass-dependent phase shift in the resulting FT spectrum. Thus, FT-ICR mass spectra have conventionally been displayed in magnitude mode, which is independent of phase. As described in detail elsewhere,38–40 broadband phase correction yields an absorption-mode spectrum with significantly higher resolving power and higher mass accuracy (after one zero-fill of the time-domain data) without loss in S/N. Figure 5 illustrates magnitude-mode and absorption-mode spectra for the 57+ charge state for the IgG1k antibody. Automated phase correction of time-domain FT-ICR signal yields narrower spectral peak width at half-maximum height and concomitant improvement (80%) in resolving power for the absorption-mode spectrum (~530,000) relative to the magnitude-mode spectrum (~290,000).

Figure 5.

ESI 9.4 T FT-ICR mass spectra for the IgG1k antibody. Top: magnitude mode; Bottom: absorption mode. Phase correction of the magnitude-mode mass spectrum results in an absorption-mode spectrum with ~1.8 times higher resolving power.

In summary, we have established a new upper mass record for unit mass baseline resolution of proteins, auguring for future characterization of large multichain antibodies and protein complexes, by FT-ICR MS. Further improvements in sample preparation and purification protocols, higher magnetic field (21 T), new ICR cell designs for improved electric field homogeneity and reduced space charge effects34, 68 should enable "nominal" resolution for a host of high molecular weight proteins (> 200 kDa) spanning (e.g.) the full human proteome,69 to reveal their post-translational modifications and populations of adducts and ligands.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John P. Quinn for help with operation and maintenance of the instrument, and Joshua J. Savory for help with tuning the ICR cell. This work was supported by NIH (1R01 GM78359), NSF Division of Materials Research through DMR-06-54118, and the State of Florida.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Additional information as noted in the text. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL, Jackson GS. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1998;17:1–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1998)17:1<1::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amster IJ. J. Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:1325–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aebersold R, Mann M. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunschel DS, Pasa-Tolic L, Feng B, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:333–337. doi: 10.1016/s1044-0305(99)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson LM, Null AP, Muddiman DC. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:601–604. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00148-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He H, Conrad CA, Nilsson CL, Ji Y, Schaub TM, Marshall AG, Emmett MR. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:8423–8430. doi: 10.1021/ac071413m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaub TM, Hendrickson CL, Horning S, Quinn JP, Senko MW, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:3985–3990. doi: 10.1021/ac800386h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He F, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:647–650. doi: 10.1021/ac000973h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossio RE, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:1674–1679. doi: 10.1021/ac0108461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savory JJ, Kaiser NK, McKenna AM, Xian F, Blakney GT, Rodgers RP, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:1732–1736. doi: 10.1021/ac102943z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogdanov B, Smith RD. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2005;24:168–200. doi: 10.1002/mas.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann M, Kelleher NL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:18132–18138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800788105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He F, Emmett MR, Hakansson K, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:61–67. doi: 10.1021/pr034058z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelleher NL. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:197A–203A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Cui W, Wen J, Blankenship RE, Gross ML. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1966–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge Y, Lawhorn BG, ElNaggar M, Strauss E, Park JH, Begley TP, McLafferty FW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:672–678. doi: 10.1021/ja011335z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loo JA, Quinn JP, Ryu SI, Henry KD, Senko MW, McLafferty FW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:286–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood TD, Chen LH, Kelleher NL, Little DP, Kenyon GL, McLafferty FW. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16251–16254. doi: 10.1021/bi00050a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senko MW, Hendrickson CL, Pasa-Tolic L, Marto JA, White FM, Guan S, Marshall AG. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1996;10:1824–1828. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(199611)10:14<1824::AID-RCM695>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelleher NL, Senko MW, Siegel MM, McLafferty FW. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1997;8:380–383. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL, Shi SD. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:252A–259A. doi: 10.1021/ac022010j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge Y, Rybakova IN, Xu Q, Moss RL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:12658–12663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813369106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell DW, Smith RD. J. Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:771–790. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cournoyer JJ, Lin C, O'Connor PB. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:1264–1271. doi: 10.1021/ac051691q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge Y, Lawhorn BG, ElNaggar M, Sze SK, Begley TP, McLafferty FW. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2320–2326. doi: 10.1110/ps.03244403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An HJ, Peavy TR, Hedrick JL, Lebrilla CB. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5628–5637. doi: 10.1021/ac034414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall AG, Comisarow MB, Parisod G. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:4434–4444. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi SD-H, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:11532–11537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledford EB, Jr, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Anal. Chem. 1984;56:2744–2748. doi: 10.1021/ac00278a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong RL, Amster IJ. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1681–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boldin IA, Nikolaev EN. Rapid Commun. Mass spectrom. 2009;23:3213–3219. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolmachev AV, Robinson EW, Wu S, Kang H, Lourette NM, Pasa-Tolic L, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolaev EN, Boldin IA, Jertz R, Baykut G. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1125–1133. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser NK, Quinn JP, Blakney GT, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1343–1351. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blakney GT, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Int. J. of Mass Spectrom. 2011;306:246–252. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolmachev AV, Robinson EW, Wu S, Pasa-Tolic L, Smith RD. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009;281:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comisarow MB, Marshall AG. Can. J. Chem. 1974;52:1997–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xian F, Hendrickson CL, Blakney GT, Beu SC, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:8807–8812. doi: 10.1021/ac101091w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qi Y, Thompson CJ, Van Orden SL, O'Connor PB. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:138–147. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emmett MR, Caprioli RM. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:605–613. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senko MW, Hendrickson CL, Emmett MR, Shi SDH, Marshall AG. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1997;8:970–976. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaiser NK, Savory JJ, McKenna AM, Quinn JP, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:6907–6910. doi: 10.1021/ac201546d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi SD-H, Drader JJ, Freitas MA, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000;195/196:591–598. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck A, Wagner-Rousset E, Bussat MC, Lokteff M, Klinguer-Hamour C, Haeuw JF, Goetsch L, Wurch T, Van Dorsselaer A, Corvaia N. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2008;9:482–501. doi: 10.2174/138920108786786411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speir JP, Senko MW, Little DP, Loo JA, McLafferty FW. J. Mass Spectrom. 1995;30:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolic LP, Bruce JE, Lei QP, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:405–408. doi: 10.1021/ac970828c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freitas MA, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG, Rostom AA, Robinson CV. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00180-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:232–235. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19990815)13:15<1639::AID-RCM691>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iavarone AT, Williams ER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2319–2327. doi: 10.1021/ja021202t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sterling HJ, Williams ER. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:1933–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sterling HJ, Cassou CA, Trnka MJ, Burlingame AL, Krantz BA, Williams ER. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1cp20277d. xxx, xxx-xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lomeli SH, Yin S, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:593–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lomeli SH, Peng IX, Yin S, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valeja SG, Tipton JD, Emmett MR, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:7515–7519. doi: 10.1021/ac1016858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruce JE, Anderson GA, Udseth HR, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:519–525. doi: 10.1021/ac9711706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofstalder SA, Bruce JE, Rockwood AL, Anderson GA, Winger BE, Smith RD. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Processes. 1994;132:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruce JE, Anderson GA, Hofstalder SA, Winger BE, Smith RD. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1993;7:700–703. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guan S, Wahl MC, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:3647–3653. doi: 10.1021/ac00072a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yergey J, Heller D, Hansen G, Cotter RJ, Fenselau C. Anal. Chem. 1983;55:353–356. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marshall AG, Senko MW, Li W, Li M, Dillon S, Guan S, Logan TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:433–434. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bou-Assaf GM, Chamoun JE, Emmett MR, Fajer PG, Marshall AG. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:3293–3299. doi: 10.1021/ac100079z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zubarev RA, Demirev PA, Hakansson P, Sundqvist BUR. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:3793–3798. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zubarev RA, Demirev PA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rockwood AL, Van Orden SL, Smith RD. Rapid Commun. Mass spectrom. 1996;10:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Senko MW, Beu SC, McLafferty FW. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1995;6:229–233. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frahm JL, Mason CJ, Muddiman DC. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;234:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boldin IA, Nikolaev EN. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:122–126. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karabacak NM, Li L, Tiwari A, Hayward LJ, Hong P, Easterling ML, Agar JN. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:846–856. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800099-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.