Abstract

Halogenated contaminants, particularly brominated flame retardants, disrupt circulating levels of thyroid hormones (THs), potentially affecting growth and development. Disruption may be mediated by impacts on deiodinase (DI) activity, which regulate the levels of active hormones available to bind to nuclear receptors. The goal of this study was to develop a mass spectrometry–based method for measuring the activity of DIs in human liver microsomes and to examine the effect of halogenated phenolic contaminants on DI activity. Thyroxine (T4) and reverse triiodothyronine (rT3) deiodination kinetics were measured by incubating pooled human liver microsomes with T4 or rT3 and monitoring the production of T3, rT3, 3,3′-diiodothyronine, and 3-monoiodothyronine by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Using this method, we examined the effects of several halogenated contaminants, including 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (BDE 99), several hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-BDEs), tribromophenol, tetrabromobisphenol A, and triclosan, on DI activity. The Michaelis constants (KM) of rT3 and T4 deiodination were determined to be 3.2 ± 0.7 and 17.3 ± 2.3μM. The Vmax was 160 ± 5.8 and 2.8 ± 0.10 pmol/min.mg protein, respectively. All studied contaminants inhibited DI activity in a dose-response manner, with the exception of BDE 99 and two OH-BDEs. 5′-Hydroxy 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether was found to be the most potent inhibitor of DI activity, and phenolic structures containing iodine were generally more potent inhibitors of DI activity relative to brominated, chlorinated, and fluorinated analogues. This study suggests that some halogenated phenolics, including current use compounds such as plastic monomers, flame retardants, and their metabolites, may disrupt TH homeostasis through the inhibition of DI activity in vivo.

Keywords: thyroid hormones, deiodinase enzymes, human liver microsomes, brominated flame retardants, halogenated phenolics, metabolites

It has been shown that some halogenated aromatic compounds (HOCs), such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), may disrupt thyroid hormone (TH) homeostasis (Darnerud et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2002), presumably due to their structural similarity to the endogenous hormones. Although the specific mechanisms responsible for this disruption are not entirely clear, several mechanisms have been investigated. For example, it has been shown that HOCs and their metabolites may competitively bind to the TH transporter proteins, transthyretin (TTR) (Hamers et al., 2006; Meerts et al., 2000) and thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) (Marchesini et al., 2008), as well as to the TH receptor in mammals (Kitamura et al., 2008; Kojima et al., 2009). In general, it has been shown that hydroxylated compounds, with halogens adjacent to the hydroxyl group, are potent competitive binders to thyroid transporters and receptors. Furthermore, hydroxylated metabolites (e.g., OH-PBDEs) have been shown to be stronger binders than their parent compounds (Hamers et al., 2008; Meerts et al., 2000), presumably because these analogues are more structurally similar to endogenous hormones. In addition, some HOCs have been shown to inhibit TH sulfation (Schuur et al., 1998a, 1998b).

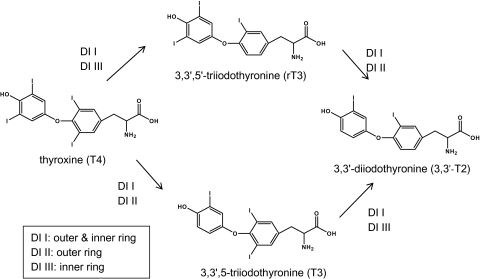

Another potential route by which disruption of THs and biological pathways mediated by THs may be effected is through impacts on deiodinases (DIs) and their activity. DIs are selenocysteine-containing proteins that regulate TH levels within peripheral tissues. The major TH form secreted by the thyroid gland is thyroxine (3,5,3′,5′-tetraiodothyronine, T4). However, the biologically active hormone is 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (T3), which is formed through the reductive deiodination of the T4 phenolic ring (“outer ring” deiodination, ORD) (Fig. 1). It is recognized that the majority (∼80%) of circulating T3 is formed through T4 deiodination in the peripheral tissues (Köhrle, 1999) and is catalyzed by type I (broad activity) and type II (outer ring specific) DI enzymes (Gereben et al., 2008). Deiodination may also occur on the T4 tyrosyl ring (“inner ring” deiodination, IRD), forming 3,3′,5′-triiodothyronine (reverse triiodothyronine [rT3]), and is catalyzed by type I and type III (inner ring specific) DI enzymes. Both T3 and rT3 may undergo additional deiodination to form 3,3′-diiodothyronine (3,3′-T2). The rT3 and T2 hormones are thought to be biologically inactive. In addition, THs may undergo conjugation with glucuronic acid and sulfate at the phenolic OH-group, and the sulfate conjugates may be more readily deiodinated (Visser, 1994). Thus, the disruption of DI activity may potentially impact circulating levels of THs within the body.

FIG. 1.

Deiodinase reactions investigated in the present study. DI I, DI II, and DI III refer to specific isoforms of the DI enzyme.

It has been shown that natural and synthetic flavonoids inhibit rat DI activity both in vitro (Auf'mkolk et al., 1986; Ferreira et al., 2002) and in vivo (Schröder-van der Elst et al., 1991). Also, 17β-estradiol and the chemical sunscreen, octyl-methoxycinnamate, were shown to diminish rat hepatic DI activity after long-term exposure (Schmutzler et al., 2004). It has been suggested that DI enzymes may be involved in the metabolism of PBDEs in fish (Noyes et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2004). Thus, although not yet specifically investigated, it is possible that PBDEs may also act as DI competitors.

Based upon their structural similarity to THs and their likely ability to interact with TTR and the TH receptor, we hypothesize that HOCs and their metabolites may also inhibit DI activity in human liver tissues. This paper describes the development of an in vitro assay to investigate DI activity in human hepatic microsomes using a new detection method. Initial experiments quantified the kinetics of ORD from T4 and rT3, respectively, in human liver microsomal fractions. The THs were detected using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), allowing for the simultaneous quantification of both IRD and ORD. The developed techniques were used to investigate the DI inhibition by OH-BDEs (PBDE metabolites), tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), 2,4,6-tribromophenol (2,4,6-TBP), and triclosan. Finally, structure-activity relationships were explored with fluorinated, chlorinated, brominated, and iodinated analogues of 2,4,6-trihalogenated phenol and bisphenol A, as well as BDE 99 and two hydroxylated metabolites. BDE 99 is one of the dominant BDE congeners in human blood and was included to examine the influence of hydroxylation on DI inhibition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

T4 (> 98%), T3 (> 95%), rT3 (> 95%), 3,3′-T2 (> 99%), 3,5-diiodothyronine (3,5-T2, 98%), triclosan (Irgasan, > 97%), TBBPA (97%), 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphenol (BPA-AF, 97%), 2,4,6-TBP (99%), 2,4,6-triiodophenol (2,4,6-TIP, 97%), 2,4,6-trifluorophenol (2,4,6-TFP, 99%), 2,4,6,-trichlorophenol (2,4,6-TCP, 98%), DL-dithiothreitol (DTT, > 99%), and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate reduced tetrasodium salt hydrate (β-NADPH, > 93%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). 3,3′,5,5′-Tetrachlorobisphenol A (TCBPA, 98%) was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). 3,3′,5,5′-tetraiodobisphenol A (TIBPA, 98%) was purchased from Spectra Group Limited (Millbury, OH). 2,2′,4,4′,5-Pentabromodiphenyl ether (BDE 99), 5-hydroxy 2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (5-OH BDE 47), 5′-hydroxy 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (5′-OH BDE 99), 6′-hydroxy 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (6′-OH BDE 99), and 4′-hydroxy 2,2′,4,5,5′-pentabromodiphenyl ether (4′-OH BDE 101) were purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT). 3-Monoiodothyronine (3-T1, 95%) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada). Stable isotope standards (13C12-T4, 13C6-3,3′,5′-T3, 13C6-3,3′,5-rT3, and 13C6-T2) were purchased from Isotec (Miamisburg, OH).

DI assays.

Human liver microsomes (CellzDirect, Durham, NC) were diluted to 1 mg protein/ml in 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 10mM DTT and 100μM NADPH (total volume = 1 ml). ORD kinetics were investigated by varying T4 or rT3 concentrations (10nM–100μM). Iodoacetate DI inhibitor experiments used 3.8μM each of T4 and rT3, respectively, with an iodoacetate concentration of 10mM. In the HOC competitor study, the substrate was held constant at 1μM T4 and varying competitor concentrations. Initial experiments used 5′-OH BDE 99, TBBPA, 2,4,6-TBP, and triclosan as competitors (chemical structures shown in the Supplementary data). Further experiments were conducted with 2,4,6-TFP, 2,4,6-TCP, 2,4,6-TIP, BPA-AF, TCBPA, TIBPA, BDE 99, 5-OH BDE 47, 6′-OH BDE 99, and 4′-OH BDE 101 to examine the role of structure on DI inhibition. Competitor concentrations ranged 1000-fold with the highest dose representative of approximately 10-fold the reported or estimated aqueous solubility. However, the microsomal protein presumably increased the competitor solubility in the incubation systems. Stock solutions of the competitors were prepared in acetone, spiked into the vials (5 μl) and vortexed. The active control vials were spiked with clean acetone only. In all studies, buffer controls were prepared to correct for substrate impurities and abiotic degradation. The kinetic experiments were performed in duplicate, whereas the competitor treatments were performed in triplicate.

Reactions were initiated with the microsome addition, vials covered and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a shaking water bath. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 1 ml of ice-cold methanol, 120 μl of a “protecting” solution was added (25 g/l of citric acid, ascorbic acid, and DTT), and vials were covered and left for 45 min. Extraction and solid-phase extraction (SPE) cleanup procedures were adapted from Wang and Stapleton (2010) with slight modifications as follows (flow charts are presented in the Supplementary data). The incubations were centrifuged at 3500 revolutions per minute for 5 min at 25°C, and the supernatant was decanted into a clean amber glass vial. The suite of mass-labeled standards were added (25 ng each of 13C12-T4, 13C6-T3, 13C6-rT3, and 13C6-T2), and the microsomes were further extracted with 900 μl of 1:1 acetone:water, centrifuged, the supernatants combined, and the extraction repeated. The solvent was evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas, and the aqueous sample was loaded onto SampliQ SPE cartridges, initially conditioned with 3 ml of methanol followed by 5 ml of water. The column was rinsed with 1 ml of 30% methanol in water and the THs eluted with 4 ml of methanol. The methanol eluents were concentrated to approximately 1 ml under nitrogen gas.

Instrumental analysis.

Instrumental analysis was performed by LC with positive electrospray MS/MS (LC-MS/MS) using conditions modified from Wang and Stapleton (2010). Chromatography was performed using a Synergi Polar-RP column (50 × 2.0 mm, 2.5 μm particle size, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) preceded by a SecurityGuard Polar-RP (4 × 2.0mm) guard cartridge. Acetonitrile and water (modified with 10mM formic acid) were used as the mobile phases, the column oven was 40°C, the injection volume was 20 μl, and the flow rate was 400 μl/min. Initial conditions were 70:30 water:acetonitrile, increasing to 50:50 over 2.5 min, held for 1 min, increased to 5:95 over 1 min, held for 1 min, returned to initial conditions over 1 min, and held for 5 min (representative chromatogram shown in Supplementary data). In addition, samples from the T4 and rT3 ORD kinetic experiments were monitored for production of the 3-T1. Data were acquired under multiple reaction monitoring conditions using optimized parameters. Analyte responses were normalized to internal standard responses.

Quality assurance/quality control and data analysis.

Recovery of the mass-labeled standards were 70.8% (standard deviation = 2.7%) for 13C12-T4, 86.7% (11.9%) for 13C6-T3, 85.8% (5.4%) for 13C6-rT3, and 90.4% (3.4%) for 13C6-3,3′-T2 for a spike of 500 ng into heat-killed microsomes (n = 5). Trace quantities of T3 and rT3 were consistently detected in the buffer control vials at levels of ∼0.4% and ∼0.1%, respectively, relative to the T4 dose. These contaminants originated from T4 commercial material impurities, and no abiotic transformation was observed during the incubations. Considering all batches (n = 12), the mean T3 impurity, resulting from the T4 commercial product, was 30.3% (relative standard deviation = 29%) relative to the T3 formed in the incubations. Therefore, the T3 impurity did not interfere with our DI assays. 3,3′-T2 was not detected in either the T4 commercial product or the buffer controls. Therefore, measured formation rates were blank corrected using the mean buffer control values. Method detection limits (MDLs) were calculated as three times the standard deviation of the procedural blanks (950 μl of incubation buffer). However, T3, rT3, 3,3′-T2, and 3,5-T2 were not detected in any of the procedural blanks. Thus, for these analytes, the instrumental detection limit was used as the MDL. MDLs (normalized to incubation conditions) were 0.95 pmol/min.mg protein for 3,3′-T2 and 3,5-T2, 0.76 pmol/min.mg protein for T3 and rT3, and 11.3 pmol/min.mg protein for T4.

For the kinetics experiments, the line of best fit and the kinetic parameters, the Michaelis constant (KM) and the maximum reaction rate (Vmax), were obtained using the “Regression Wizard” in SigmaPlot (v. 9.01, Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL) assuming a “one-site saturation” model. At the lower rT3 concentrations, nearly all the substrate was consumed during the incubation. As such, the average of the initial and final rT3 concentration was used for the kinetic parameter calculations. The intrinsic clearance rate (CLint) was calculated as the ratio of the Vmax to the KM. In the competitor study, half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were obtained using the one-site competition model in SigmaPlot.

RESULTS

DI Enzyme Kinetics

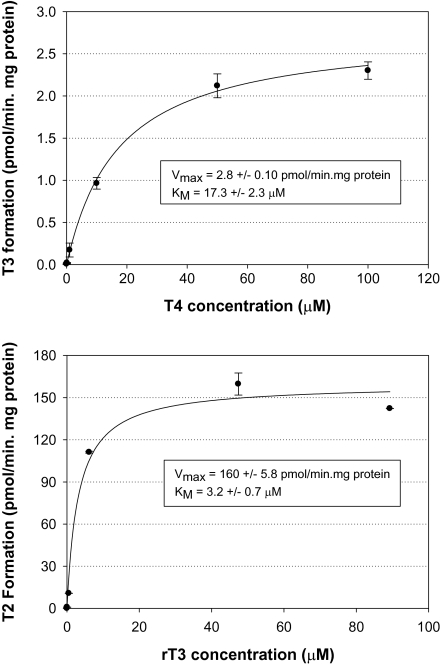

Incubation of human liver microsomes with both T4 and rT3 treatments showed typical Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics reaching apparent saturation within the range of concentrations tested (Fig. 2). The apparent KM for the T4→T3 reaction was 17.3 ± 2.3μM, and the Vmax was 2.8 ± 0.10 pmol/min.mg protein. For the rT3→3,3′-T2 reaction, the apparent KM was 3.2 ± 0.7μM and the Vmax was 160 ± 5.8 pmol/min.mg protein. Under physiologically relevant substrate concentrations (i.e., significantly below saturation), the most appropriate parameter for the comparison of metabolic rates is the CLint, calculated as the ratio of Vmax to KM (Hofstee, 1952). In the present study, the CLint parameters were 0.16 and 50 μl/min.mg protein for the T4 and rT3 incubations, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Formation rate (pmol/min.mg protein) of T3 and 3,3′-T2 resulting from incubation of T4 (top panel) and rT3 (bottom panel), respectively. Michaelis constant (KM) and maximum reaction rate (Vmax) obtained from nonlinear regression analysis. Each data point represents the mean (n = 2), error bars represent 1 standard error.

In addition, IRD was observed in the T4 incubations, as evidenced by the formation of rT3. Assuming that rT3 deiodination is the dominant pathway of 3,3′-T2 formation (Piehl et al., 2008) and that the T4→rT3 reaction is the limiting step, the kinetics of IRD can be estimated by the sum of rT3, 3,3′-T2, and 3-T1 formation. Using these assumptions, the apparent T4 IRD rates were 49–86% of ORD rates. The formation of 3,5-T2 was not observed in the T4 incubation, which indicates that T3 ORD does not occur. Finally, trace amounts of 3-T1 was formed in both the T4 and the rT3 incubations, accounting for 0.5–4% of the 3,3′-T2 yield.

Inhibition of Type I DI Enzyme

In the absence of the DI inhibitor iodoacetate, the formation of T3 was 0.67 ± 0.01 (standard deviation) pmol/min.mg protein from deiodination of 6.4μM of T4 and the yield of 3,3′-T2 was 19.7 ± 2.5 pmol/min.mg protein from the deiodination of 7.7μM of rT3. However, in the presence of 10mM iodoacetate, T3 and T2 were not formed in either incubation, indicating the complete shutdown of type I DI activity.

Competitive Substrate Experiments with Halogenated Contaminants

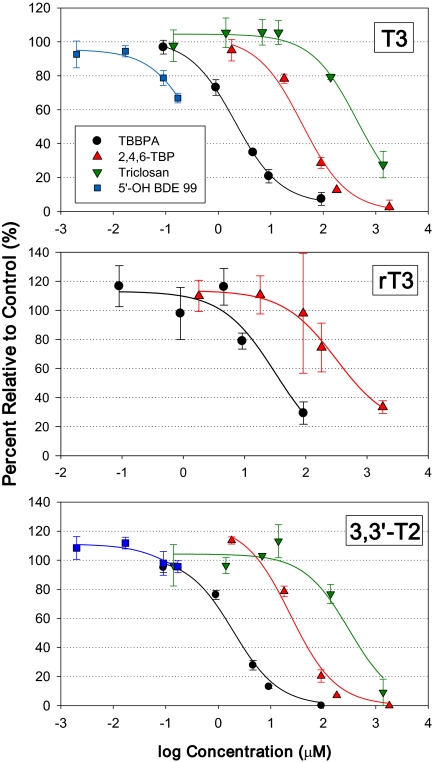

The inhibition of ORD was investigated by monitoring the formation of T3 from T4 in the presence of individual halogenated phenolic compounds. All compounds showed a dose-response relationship. Almost complete inhibition of DI activity was observed at the highest dose tested for TBBPA and 2,4,6-TBP (Fig. 3). The calculated IC50 values showed that the relative order of potency was 5′-OH BDE 99 (IC50 value = 0.4μM) > TBBPA (2.1μM) > 2,4,6-TBP (40μM) > triclosan (400μM) (Table 1). However, the IC50 value for the 5′-OH BDE 99 is approximate because the tested doses did not extend through the 50% inhibition level.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of T3, rT3, and 3,3′-T2 formation resulting from the incubation of human liver microsomes with 1μM T4 and various halogenated phenolic competitors. No relationship with 5′-OH BDE 99 and triclosan was found for the rT3 formation. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

TABLE 1.

IC50 Values (μM) for the Inhibition of T3, rT3, and 3,3′-T2 Formation from the Incubation of T4 with Human Liver Microsomes

| T3 | rT3 | 3,3′-T2 | |

| TIBPA | 15 | 81 | 11 |

| TBBPA | 2.1 | 32 | 1.9 |

| TCBPA | 3.2 | 27 | 3.2 |

| BPA-AF | 140 | 590 | 140 |

| 2,4,6-TIP | 10 | 57 | 7.6 |

| 2,4,6-TBP | 40 | 315 | 24 |

| 2,4,6-TCP | 130 | 470 | 70 |

| 2,4,6-TFP | 6200 | 11,000 | 3200 |

| Triclosan | 440 | n/aa | 310 |

| 5-OH BDE 47 | n/aa | n/aa | n/aa |

| 5′-OH BDE 99 | 0.4 | n/aa | 0.2 |

| 6′-OH BDE 99 | n/aa | n/aa | n/aa |

| 4′-OH BDE 101 | n/aa | n/aa | n/aa |

| BDE 99 | n/aa | n/aa | n/aa |

IC50 value could not be calculated by SigmaPlot.

Similarly, the IRD inhibition was investigated by monitoring the formation of rT3 from T4 in the presence of halogenated phenolic compounds. Investigation of IRD inhibition is complicated by the fact that the rT3 formed is rapidly deiodinated to 3,3′-T2. Consistent with the results from the kinetic studies, rT3 was formed in much lower rates than T3. A dose-response relationship was shown for TBBPA and 2,4,6-TBP, and the calculated IC50 values followed the same potency rank order as the ORD (Fig. 3, Table 1). Interestingly, 5′-OH BDE 99 and triclosan had no effect on rT3 levels (data not shown).

Inhibition of 3,3′-T2 formation was also observed, which can result from the inhibition of both IRD and ORD. Dose-response relationships were observed for all compounds with complete inhibition of 3,3′-T2 formation at the highest doses for TBBPA, 2,4,6-TBP, and triclosan (Fig. 3) 3,3′-T2 formation was only slightly inhibited (∼10%) at the highest 5′-OH BDE 99 dose (0.17μM). The rank order of 3,3′-T2 inhibition was similar to that shown for T3 inhibition, 5′-OH BDE 99 (IC50 values = 0.2μM) > TBBPA (1.9μM) > 2,4,6-TBP (24μM) > triclosan (311μM) (Table 1). Similar to the T3 IC50 value, the 5′-OH BDE 99 value is considered approximate.

Influence of Halogen Substitution on DI Inhibition

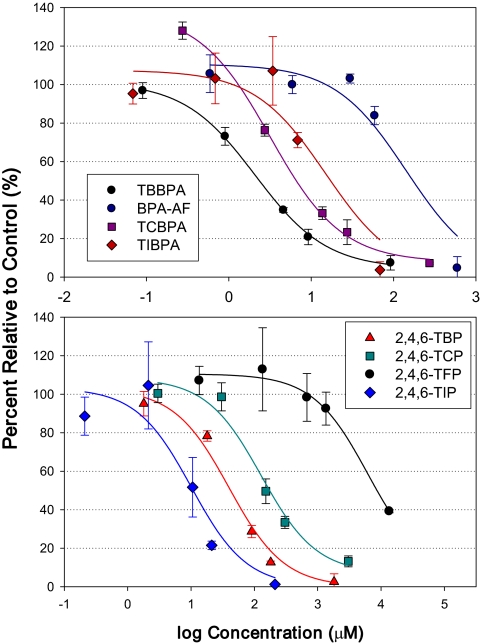

To investigate the role of specific halogens on DI inhibition, further assays were challenged with fluorinated, chlorinated, brominated, and iodinated analogues of 2,4,6-trihalogenated phenol and bisphenol A, as well as with BDE 99 and four OH-BDEs. In general, the DI inhibition potency increased with increasing halogen molecular weight, with the exception of TIBPA, which showed immediate potency.

TIBPA, TCBPA, and BPA-AF showed the ability to inhibit DI activity in a dose-response manner, similar to TBBPA (Fig. 4 for T3; results for rT3 and T2 not shown). However, TBBPA was the most potent DI inhibitor (IC50 value for T3 formation inhibition = 2.1μM) followed by TCBPA (3.2μM), TIBPA (15μM), and BPA-AF (140μM). IC50 values for T3, rT3, and T2 formation inhibition are shown in Table 1.

FIG. 4.

Structure-activity relationships for the inhibition of DI activity in human liver microsomes. Figures show the inhibition of T3 formation, as a function of competitor concentration, resulting from the incubation of human liver microsomes with 1μM. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

In addition, the iodo-, chloro-, and fluoro-substituted analogues of trihalogenated phenol showed increasing DI inhibition with increasing dose, in a similar manner to 2,4,6-TBP. Furthermore, the rank order of DI inhibition has shown increasing potency with increasing halogen molecular weight, specifically 2,4,6-TIP (IC50 value for T3 formation inhibition = 10μM) > 2,4,6-TBP (40μM) > 2,4,6-TCP (130μM) > 2,4,6-TFP (6200μM).

The parent BDE 99 and two of the hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-BDEs) (5-OH BDE 47 and 4′-OH BDE 101) did not show DI inhibition (Fig. 4 for BDE 99 and 5-OH BDE 47 and 4′-OH BDE 101 not shown). However, 5′-OH BDE 99 showed ∼35% inhibition of T3 formation at the highest dose (0.17μM). Furthermore, 6′-OH BDE 99 showed ∼15% T3 formation inhibition throughout the range of doses tested.

DISCUSSION

The kinetics of ORD was evaluated by monitoring the formation of T3 and 3,3′-T2 from incubations with T4 and rT3, respectively, in human liver tissues. Although ORD is catalyzed by both type I and II DI, these reactions presumably only involved type I DI because it has been shown that type II DI is not expressed in human liver (Richard et al., 1998) but is highly expressed in other tissues such as the brain, pituitary, and brown adipose tissue (Köhrle, 1999).

The present study showed that the rT3→T2 reaction was much more efficient than the T4→T3 reaction in human liver. These trends are consistent with rT3 being the preferred substrate for type I DI (Köhrle, 1999; Visser et al., 1988). The KM and Vmax parameters for the rT3→T2 reaction in the present study are similar to those reported from human liver homogenate (KM = 4.5μM, Vmax = 121 pmol/min.mg protein) (Sabatino et al., 2000) using radiolabeled methods. However, the Vmax values obtained in our study were approximately two- to threefold lower than previous studies using human liver microsomes, and the KM values were ∼10- to 20-fold greater than previously reported using radiolabeled methods in human liver microsomes (Toyoda et al., 1997; Visser et al., 1988). In addition, previous reports of CLint were ∼10-fold greater for T4→T3 and ∼10- to 100-fold greater for rT3→T2 (Toyoda et al., 1997; Visser et al., 1988). The differences in CLint values were due to the much greater KM values measured in the present study. The earlier studies (Toyoda et al., 1997; Visser et al., 1988) quantified TH formation using either a radioimmunoassay or by measuring the release of 125I− (only rT3 in Toyoda et al., 1997), which may have led to the discrepancies between the studies. LC-MS/MS methods, such as those employed in the present study, are superior to RIA and 125I− release techniques due to their unambiguous and simultaneous identification of THs, allowing for the concurrent quantification of ORD and IRD. Piehl et al. (2008) showed good agreement in KM and Vmax values between LC-MS/MS and 125I− release techniques using rT3 as the substrate in hepatic cell isolates. However, 125I− release techniques are presumably not appropriate for monitoring DI pathways that result from the consecutive removal of multiple iodine atoms, such as the formation of 3,3′-T2 from T4. In addition, DI enzyme polymorphism has been observed and has been shown to be correlated with circulating rT3 levels and rT3/T4 ratios (Peeters et al., 2003), which could explain some of the variation between the present study and the literature values.

In addition to ORD, IRD was observed in the T4 incubations as evidenced by the formation of rT3. The IRD observed was most likely catalyzed by type I DI because it has been shown that type III is generally negligible in adult human liver microsomes (Huang, 2005; Richard et al., 1998). The most relevant pathway of 3,3′-T2 formation is presumably through rT3 ORD because it was shown that T3 was not deiodinated in lysates from the HepG2 human liver carcinoma cell line (Piehl et al., 2008). However, it is unknown if this trend would be observed in the liver microsomes. In our experiments, the higher 3,3′-T2 formation rate as compared with rT3 is consistent with the high rate of rT3 deiodination observed in rT3 incubations. Furthermore, the relative trends in T3, rT3, and 3,3′-T2 formation are consistent with other studies using human liver microsomes (Visser et al., 1988). We did not observe the formation of 3,5-T2 in the T4 incubations, which indicates that T3 ORD did not occur in appreciable amounts. We could not monitor for the potential rT3 IRD because an authentic standard for this compound (3′,5′-T2) was not available.

The addition of high iodoacetate concentrations (10mM) resulted in the complete inhibition of type I DI in the human liver microsomes. Iodoacetate is a well-known inhibitor of type I DI, and its inhibition mechanism proceeds through the carboxymethylation of the DI active center resulting in irreversible inactivation (Bianco et al., 2002). These trends, together with the kinetic studies, indicate that our assay was satisfactory for the investigation of DI activity in human liver microsomes.

Our initial DI inhibition experiments broadly investigated the potential of halogenated phenolic compounds to inhibit DI activity when T4 was used as the substrate. This pathway was chosen for the competitive experiments because it is the more biologically relevant reaction in thyroid homeostasis. Several of the compounds investigated have current uses. Triclosan is an antimicrobial widely used in personal care products. BDE 99 was a component of the predominantly banned pentaBDE commercial mixture but is still widely detected in the environment, whereas OH-BDEs are formed through the P450 oxidative metabolism of BDEs. 2,4,6-TBP is used as a flame retardant and, analogous to the formation of 2,4,5-TBP from BDE 99 (Stapleton et al., 2009), also may result from the biotransformation of some PBDEs. In contrast, BPA-AF is a hexafluoro derivative of BPA where the two bridge CH3 groups are replaced with CF3 groups and, like BPA, is used as a monomer for polymers and has recently garnered interest due to its potential estrogenic effects (Matsushima et al., 2010).

All classes of halogenated phenolic compounds tested showed some inhibition of DI activity, although there were some differences between the compounds with regard to ORD and IRD inhibition trends. Specifically, inhibition of T3 and 3,3′-T2 formation was shown for all compounds, whereas inhibition of rT3 formation was not shown for 5′-OH BDE 99 and triclosan. This may represent different mechanisms of type I DI inhibition by these compounds although the mechanism is unclear. For example, the 5′-OH BDE 99 and triclosan may bind differently, perhaps to a different active site in the type I DI enzyme, that prevents the inhibits of ORD but not the IRD. Based on their structural similarity to the endogenous THs, it was assumed that the HOCs behaved as competitive inhibitors. However, it is also possible that the HOCs were noncompetitive inhibitors binding to a non-active enzyme site and disturbing the enzyme structure, thereby inhibiting overall DI activity. Further work is necessary to determine the precise mechanism of inhibition.

The general rank order of DI inhibition potency was 5′-OH BDE 99 > TBBPA > 2,4,6-TBP > triclosan. This ranking presumably represents the rank order of potential binding to the DI active site. To our knowledge, none of the compounds examined in the present study have previously been investigated for their DI inhibition potential in vitro. However, Szabo et al. (2009) showed a reduction in DI activity in male rat pups exposed to DE-71 (a commercial pentaBDE mixture) during gestation. Very little is known about the binding pocket requirements for type I DI. However, it has been suggested that the type I DI binding requirements are similar to that of the TTR transporter protein (Auf'mkolk et al., 1986; Koehrle et al., 1986). For example, using a biosensor-based assay, TBBPA and 2,4,6-TBP were classified as “strong” binders, whereas triclosan was classified as a “moderate” binder. 5′-OH BDE 99 was not tested, but 6′-OH BDE 99 was also classified as a strong binder (Marchesini et al., 2008). Furthermore, using in vitro binding assays, it was shown that TBBPA and 2,4,6-TBP were more potent TTR binders than T4 (Hamers et al., 2006; Meerts et al., 2000).

Our structure-activity relationship experiments showed that the DI inhibition potency generally increased with increasing halogen molecular weight (i.e., I > Br > Cl > F). The exception was that the TIBPA showed relatively intermediate potency (TBBPA > TCBPA > TIBPA > BPA-AF). These findings are consistent with studies investigating T4-TTR binding affinity (Marchesini et al., 2008; Meerts et al., 2000).

In the present study, it was shown that BDE 99 did not inhibit DI activity over the range of concentrations tested (0.01–5μM). However, two of the hydroxylated metabolites (5′-OH BDE 99 and 6′-OH BDE 99) did show DI inhibition. These results are consistent with studies that have shown negligible or slight TTR competitive binding with PBDEs (Marchesini et al., 2008) but increased binding after metabolic conversion (Hamers et al., 2008; Meerts et al., 2000). Thus, the trends in the present study and previous studies with TTR demonstrate the importance of an OH-group for the binding to TTR and DI enzymes. Interestingly, two of the OH-BDEs tested did not show DI inhibition (5-OH BDE 47 and 4′-OH BDE 101). These findings were surprising because 5-OH BDE 47 was shown to be a potent competitive binder to TTR (Hamers et al., 2008; Marchesini et al., 2008). Thus, there appears to be some differences in the relative binding of these contaminants to the TTR and DI active sites.

It is possible that some of the HOC competitors were metabolized in the in vitro assays to additional hydroxylated and methoxylated compounds. In the present study, no attempt was made to quantify potential metabolites. However, using human liver microsomes that were incubated for 2 h, BDE 99 was shown to be metabolized between 15 and 60% relative to the parent compound in three different samples (Lupton et al., 2009). However, in our study, BDE 99 did not inhibit DI activity, but several of the hydroxylated metabolites did, indicating that there was likely minimal metabolism of BDE 99 or that metabolites were formed which are not DI inhibitors. Hamers et al. (2008) showed that the TTR binding potency increased after individual BDEs were biotransformed but decreased after metabolism of TBBPA and 2,4,6-TBP. However, it is not known if oxidative metabolism will similarly increase the DI inhibition potency of BDEs.

The IC50 values for the 5′-OH BDE 99 (400 and 200nM for T3 and 3,3′-T2 inhibition, respectively) were only approximately two- to fourfold greater than those measured for TTR-T4 and TBG-T4 binding inhibition (84 and 100nM, respectively) (Marchesini et al., 2008). Furthermore, TTR-T4 binding assays with a suite of penta-substituted OH-BDEs showed IC50 values ranging from 17 to 170nM (Hamers et al., 2008). These results suggest that OH-BDE potency for DI inhibition is within the same range as that observed for other TH-disrupting mechanisms (i.e., binding to TTR and TBG). However, the IC50 values from the various TH in vitro assays may not be directly comparable due to the different experimental conditions. Furthermore, because we used in vitro conditions, it is not possible to directly compare the IC50 values in our study to circulating contaminant levels in humans.

Environmental Relevance

This study contributes to the growing body of literature that demonstrates that halogenated phenolic compounds may impact TH homeostasis. Specifically, the present study showed that some halogenated phenolic compounds can inhibit type I DI activity in human liver microsomes, thereby diminishing the conversion of T4 to lower iodinated compounds. Therefore, the findings of the present study suggest that the inhibition of DI activity by exogenous compounds may be a possible mechanism for the disruption of TH homeostasis that has been observed in laboratory animal exposure studies, particularly with PBDEs. In fact, research by our laboratory has demonstrated that the in vivo exposure of BDE 209 inhibits DI activity in juvenile fathead minnows (Noyes et al., 2011). Considering that DI activity is also critical to development in other tissues (e.g., brain and placenta/fetus), further investigation of DI inhibition in these tissues is warranted. In addition, studies are needed to understand the impact of HOC inhibition on DI activity in whole body TH homeostasis and possible developmental effects. For example, type III DI is highly expressed in the placenta and is important for maintaining low TH levels in the developing fetus early in pregnancy (Bianco et al., 2002). Research with type III DI knockout mice shows reduced T3 clearance and elevated T3 levels in neonates but reduced hypothyroidism in weanlings and adults (Hernandez et al., 2006). In addition, these type III DI knockout mice showed increased perinatal mortality and growth retardation (Hernandez et al., 2006). Interestingly, type I/II DI knockout mice showed unaltered T3 levels but moderately increased T4 levels (Galton et al., 2009). Overall, these findings suggest that the regulation of DI enzymes is critical for normal development in mammals and HOCs, which are commonly detected in human tissues, may be affecting normal DI activity.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 ES016099); 545 postdoctoral fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to C.M.B.

Supplementary Material

References

- Auf'mkolk M, Koehrle J, Hesch R-D, Cody V. Inhibition of rat liver iodothyronine deiodinase: Interaction of aurones with the iodothyronine ligand-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11623–11630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23:38–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnerud PO, Eriksen GS, Johannesson T, Larsen PB, Viluksela M. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers: Occurrence, dietary exposure, and toxicology. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109:49–68. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira ACF, Lisboa PC, Oliveira KJ, Lima LP, Barros IA, Carvalho DP. Inhibition of thyroid type1 deiodinase activity by flavonoids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:913–917. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA. The roles of the iodothyronine deiodinases in mammalian development. Thyroid. 2005;15:823–834. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA, Schneider MJ, Clark AS, Germain DLS. Life without thyroxine to 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine conversion: Studies in mice devoid of the 5′-deiodinases. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2957–2963. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereben B, Zavacki AM, Ribich S, Kim BW, Huang SA, Simonides WS, Zeöld A, Bianco AC. Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:898–938. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers T, Kamstra JH, Sonneveld E, Murk AJ, Kester MHA, Andersson PL, Legler J, Brouwer A. In vitro profiling of the endocrine-disrupting potency of brominated flame retardants. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;92:157–173. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers T, Kamstra JH, Sonneveld E, Murk AJ, Visser TJ, Van Velzen MJM, Brouwer A, Bergman A. Biotransformation of brominated flame retardants into potentially endocrine-disrupting metabolites, with special attention to 2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:284–298. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, St Germain D. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:476–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI26240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstee BHJ. On the evaluation of the constants Vm and KM in enzyme reactions. Science. 1952;116:329–331. doi: 10.1126/science.116.3013.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SA. Physiology and pathophysiology of type 3 deiodinase in humans. Thyroid. 2005;15:835–840. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Shinohara S, Iwase E, Sugihara K, Uramaru N, Shigematsu H, Fujimoto N, Ohta S. Affinity for thyroid hormone and estrogen receptors of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers. J. Health Sci. 2008;54:607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Koehrle J, Auf'mkolk M, Rokos H, Hesch R-D, Cody V. Rat liver iodothyronine monodeiodinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11613–11622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhrle J. Local activation and inactivation of thyroid hormones: The deiodinase family. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1999;151:103–119. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima H, Takeuchi S, Uramaru N, Sugihara K, Yoshida T, Kitamura S. Nuclear hormone receptor activity of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and their hydroxylated and methoxylated metabolites in transactivation assays using Chinese ovary cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:1210–1218. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton SJ, McGarrigle BP, Olson JR, Wood TD, Aga DS. Human liver microsome-mediated metabolism of brominated diphenyl ethers 47, 99, and 153 and identification of their major metabolites. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:1802–1809. doi: 10.1021/tx900215u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini GR, Meimaridou A, Haasnoot W, Meulenberg E, Albertus F, Mizuguchi M, Takeuchi M, Irth H, Murk AJ. Biosensor discovery of thyroxine disrupting chemicals. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;232:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima A, Liu X, Okada H, Shimohigashi M, Shimohigashi Y. Bisphenol AF is a full agonist for the estrogen receptor ERα but a highly specific antagonist for ERβ. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:1267–1272. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerts IATM, van Zanden JJ, Luijks EAC, van Leeuwen-Bol I, Marsh G, Jakobsson E, Bergman A, Brouwer A. Potent competitive interactions of some brominated flame retardants and related compounds with human transthyretin in vitro. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;56:95–104. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Hinton DE, Stapleton HM. Accumulation and debromination of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) in juvenile fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) induces thyroid disruption and liver alterations. Toxicol. Sci. 122:265–274. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Kelly SM, Mitchelmore CL, Stapleton HM. Characterizing the in vitro hepatic biotransformation of the flame retardant BDE 99 by common carp. Aquat. Toxicol. 2010;97:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters RP, van Toor H, Klootwijk W, de Rijke YB, Kuiper G, Uitterlinden AG, Visser TJ. Polymorphisms in thyroid hormone pathway genes are associated with plasma TSH and iodothyronine levels in healthy subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:2880–2888. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl S, Heberer T, Balizs G, Scanlan TS, Köhrle J. Development of a validated liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method for the distinction of thyronine and thyronamine constitutional isomers and for the identification of new deiodinase substrates. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3286–3296. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard K, Hume R, Kaptein E, Sanders JP, Van Toor H, De Herder WW, Den Hollander JC, Krenning EP, Visser TJ. Ontogeny of iodothyronine deiodinases in human liver. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:2868–2874. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino L, Iervasi G, Ferrazzi P, Francesconi D, Chopra IJ. A study of iodothyronin 5′-monodeiodinase activities in normal and pathological tissues in man and their comparison with activities in rat tissues. Life Sci. 2000;68:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutzler C, Hamann I, Hofmann PJ, Kovacs G, Stemmler L, Mentrup B, Schomburg L, Ambrugger P, Gruters A, Seidlova-Wuttke D, et al. Endocrine active compounds affect thyrotropin and thyroid hormone levels in serum as well as endpoints of thyroid hormone action in liver, heart and kidney. Toxicology. 2004;205:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-van der Elst JP, van der Heide D, Köhrle J. In vivo effects of flavonoid EMD 21388 on thyroid hormone secretion and metabolism in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991;261:E227–E232. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.2.E227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuur AG, Legger FF, van Meeteren ME, Moonen MJH, van Leeuwen-Bol I, Bergman A, Visser TJ, Brouwer A. In vitro inhibition of thyroid hormone sulfation by hydroxylated metabolites of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998a;11:1075–1081. doi: 10.1021/tx9800046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuur AG, van Leeuwen-Bol I, Jong WMC, Bergman A, Coughtrie MWH, Brouwer A, Visser TJ. In vitro inhibition of thyroid hormone sulfation by polychlorobiphenylols: Isozyme specificity and inhibition kinetics. Toxicol. Sci. 1998b;45:188–194. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Alaee M, Letcher RJ, Baker JE. Debromination of the flame retardant decabromodiphenyl ether by juvenile carp (Cyprinus carpio) following dietary exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:112–119. doi: 10.1021/es034746j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Kelly SM, Pei R, Letcher RJ, Gunsch C. Metabolism of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) by human hepatocytes in vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:197–202. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo DT, Richardson VM, Ross DG, Diliberto JJ, Kodavanti PRS, Birnbaum LS. Effects of perinatal PBDE exposure on hepatic phase I, phase II, phase III, and deiodinase 1 gene expression involved in thyroid hormone metabolism in male rat pups. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;107:27–39. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda N, Kaptein E, Berry MJ, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Visser TJ. Structure-activity relationships for thyroid hormone deiodination by mammalian type I iodothyronine deiodinases. Endocrinology. 1997;138:213–219. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ. Role of sulfation in thyroid hormone metabolism. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1994;92:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ, Kaptein E, Terpstra OT, Krenning EP. Deiodination of thyroid hormone by human liver. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1988;67:17–24. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Stapleton HM. Analysis of thyroid hormones in serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;397:1831–1839. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Taylor MM, DeVito MJ, Crofton KA. Developmental exposure to brominated diphenyl ethers results in thyroid hormone disruption. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;66:105–116. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.