Abstract

Oral isotretinoin (13-cis retinoic acid) is the most effective drug in the treatment of acne and restores all major pathogenetic factors of acne vulgaris. isotretinoin is regarded as a prodrug which after isomerizisation to all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) induces apoptosis in cells cultured from human sebaceous glands, meibomian glands, neuroblastoma cells, hypothalamic cells, hippocampus cells, Dalton's lymphoma ascites cells, B16F-10 melanoma cells, and neuronal crest cells and others. By means of translational research this paper provides substantial indirect evidence for isotretinoin's mode of action by upregulation of forkhead box class O (FoxO) transcription factors. FoxOs play a pivotal role in the regulation of androgen receptor transactivation, insulin/insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-signaling, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPArγ)- and liver X receptor-α (LXrα)-mediated lipogenesis, β-catenin signaling, cell proliferation, apoptosis, reactive oxygene homeostasis, innate and acquired immunity, stem cell homeostasis, as well as anti-cancer effects. An accumulating body of evidence suggests that the therapeutic, adverse, teratogenic and chemopreventive effecs of isotretinoin are all mediated by upregulation of FoxO-mediated gene transcription. These FoxO-driven transcriptional changes of the second response of retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-mediated signaling counterbalance gene expression of acne due to increased growth factor signaling with downregulated nuclear FoxO proteins. The proposed isotretinoin→ATRA→RAR→FoxO interaction offers intriguing new insights into the mode of isotretinoin action and explains most therapeutic, adverse and teratogenic effects of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne by a common mode of FoxO-mediated transcriptional regulation.

Key words: acne, apoptosis, FoxO, isotretinoin, transcriptional regulation, stem cell

Introduction

With the observation of Peck et al. in 1979 that isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) produced marked clearing in patients with nodulocystic acne, a new era in acne treatment began.1 Since its approval by the US FDA in 1982, isotretinoin has been considered a breakthrough treatment against severe nodulocystic acne.2,3 Isotretinoin is the most potent known inhibitor of sebum production. Multiple modes of action of isotretinoin, including suppression of sebaceous gland activity, normalization of the pattern of keratinization within the sebaceous gland follicle, inhibition of inflammation, reduction of growth of Propionibacterium acnes and normalization of the expression of tissue matrix metalloproteinases make isotretinoin the single most effective drug in the treatment of acne. Isotretinoin not only affects the sebaceous follicle but exerts adverse effects on various tissues in the body.4 Isotretinoin undergoes significant and selective all-trans-isomerization to all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) in cultured sebocytes.5 Isotretinoin has been considered as a prodrug mediating its activity through isomerization to ATRA.5–7 Despite its multiple actions on proliferation, metabolism, reactive oxygen homeostasis, inflammation, matrix remodeling and sebum suppression, the underlying mode of action and especially its unique sebostatic activity has not been unraveled despite more than 30 years of clinical use. The effectiveness of isotretinoin on all major pathogenetic aspects of acne implies that there is however a fundamental mechanism of action at the regulatory level of gene transcription which cannot be explained by primary transcriptional responses of ATRA to retinoic acid receptor (RAR).2

Binding of ATRA initiates changes in interactions of RARs/retinoid X receptors (RXRs) with corepressor and coactivator proteins, activating transcription of primary target genes. Importantly, ATRA/RAR-signaling induces secondary responses in gene expression encoding transcription factors and signaling proteins that further augment a whole cascade of gene expression.8 These transcription factors of the secondary response, especially FoxO proteins, then transcriptionally activate their target genes to generate the whole spectrum of retinoid-mediated transcriptional regulation. It has been speculated that the addition of ATRA leads to major intra- and interchromosomal transcription “interactomes” so that active ATRA-coregulated genes and their regulatory factors cooperate to generate specialized nuclear areas for coordinated transcriptional control.8 These secondary responses and the full orchestration of transcription factors and coregulators of the second response to ATRA are less well characterized but appear to be crucial for isotretinoin's mode of action. It has recently been recognized that ATRA increased the expression of transcription factor FoxO3a in neuroblastoma cells.9 FoxO3a has also been identified as a key regulator for ATRA-induced granulocytic differentiation and apoptosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia.10 Treating acute promyelocytic leukemia cells with ATRA, FoxO3a phosphorylation was reduced and FoxO3a trans-located into the nucleus. Intriguingly, FoxO3a is a strong inducer of the transcription factor FoxO1.11 FoxO1 expression is stimulated by activated FoxO3a at the promoter of FoxO1 in a positive feed back loop.11 The transcription of FoxO genes is stimulated by FoxO3 and repressed by growth factors like insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) which are increased in puberty and acne-associated syndromes with insulin resistance.11,12 Thus, there is evidence from translational research for a relationship between retinoid signaling and FoxO-mediated gene regulation. This relationship and the fact, that a multitude of cellular events in acne pathophysiology, isotretinon action and isotretinoin-induced adverse effects can be related to FoxO regulation resulted in the formulation of a recent hypothesis for the role of FoxO1 in acne pathogenesis and isotretinoin's mode of action.13

Indirect evidence will be provided in this paper which strongly suggests that acne may be explained by a growth factor-induced nuclear deficiency of FoxO1, whereas isotretinoin increases nuclear FoxO1 levels and thus reverses acne-related imbalances of FoxO homeostasis.13 In fact, all adverse and teratogenic effects of isotretinoin can be explained by FoxO-mediated proapoptotic signaling. To understand the pluripotent and multifunctional roles of FoxO transcription factors, a brief introduction in the extending network of FoxO transcription factors is helpful.

FoxO-Transcription Factors

Forkhead box O (FoxO) transcription factors FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 and FoxO6 are important regulatory proteins that modulate the expression of genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, apoptosis, oxidative stress, cell differentiation, glucose metabolism, inflammation, immune functions and regulation of stem cell homeostasis.14–19 FoxO1 represents the predominant FoxO isoform. FoxO1 and FoxO3a are proteins with a length of about 650 amino acids. FoxOs contain a conserved DNA binding domain and either activate or inhibit the transcription of target genes containing a consensus DNA binding sequence TTG TTT AC.14,19 Furthermore, FoxO proteins can interact with several other transcription factors like androgen receptor (AR) or β-catenin, therby modifying gene regulation. Central to the regulation of FoxO transcription factors is a shuttling system, which confines FoxO factors to either the nucleus or the cytosol (Fig. 1).14,15 Among other involved and less important kinases, shuttling of FoxOs requires protein phosphorylation of nuclear FoxOs by phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-mediated activation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt (also known as protein kinase B, PKB).11–14 Activated (phosphorylated) Akt translocates into the nucleus for FoxO phosphorylation. Phosphorylated FoxOs leave the nucleus, thereby changing gene regulation (Fig. 1). Dysregulation of FoxO1 and its nuclear export by insulin, IGF-1, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) or other growth factors modifying the activation of PI3K/Akt affect the transcriptional activity of key target genes and nuclear receptors involved in acne pathogenesis. Increased growth factor signaling is an endocrinological hallmark of puberty as well as insulinotropic western nutrition with increased consumption of milk and other insulinotropic dairy products and carbohydrates with high glycemic index.20–23

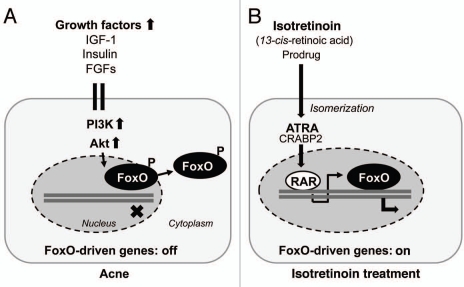

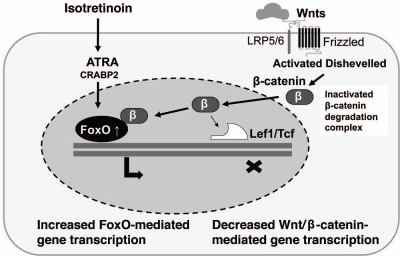

Figure 1.

(A) Nuclear exclusion of FoxO proteins into the cytoplasm by growth factor signaling due to Akt kinase-mediated phosphorylation of nuclear FoxO proteins. (B) Isotretinoin-mediated upregulation of FoxO expression as a secondary response of proapoptotic RAR-signaling. FoxO-regulated genes are switched on. IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; FGFs, fibroblast growth factors; PI3K, phosphoinositol-3 kinase; Akt, Akt kinase (protein kinase B); FoxO, forkhead box class O transcription factor; ATRA, all-trans-retinoic acid; CRABP2, cellular retinoic acid binding protein-2; RAR, retinoic acid receptor.

Isotretinoin, FoxO1 and Suppression of Androgen Receptor Transactivation

Androgen receptor (AR)-mediated signal transduction plays an essential role for the stimulation of the size of sebocytes and sebum production as well as keratinocyte proliferation in the ductus seboglandularis and the acroinfundibulum. ARs are expressed in basal and differentiating sebocytes and pilosebaceous duct keratinocytes.24–25 Androgens induce the expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), the most important transcription factor of lipogenesis.26 Androgen-insensitive subjects who lack functional ARs do not produce sebum and do not develop acne.27 Increased AR protein levels have been determined in skin of acne patients.28

AR is a modular protein organized into functional domains, consisting of an N-terminal transcription activation domain (TAD), a DNA-binding domain and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain for androgens.29 Ligand-activated ARs induce the transcription of androgen-responsive target genes. The TAD of AR mediates the majority of AR transcriptional activity and provides the most active coregulator interaction surface.30 The AR integrates a multitude of regulatory signals and its final transcriptional activity is integrated by the action of more than 150 known coregulators which are either coactivators or corepressors.31 FoxO1 is an important metabolically regulated AR corepressor and binds to the TAD, where it disrupts p160 coactivator binding and suppresses N-terminal/C-terminal-interaction, which is most important for AR transcriptional activity (Fig. 2A).32 The AR repressive function of FoxO1 is attenuated by increased growth factor signaling with activation of the PI3K/Akt cascade.33,34 On the other hand, the expression of several growth factors like IGF-1 and regulatory proteins of cell cycle control and lipogenesis are dependent on androgen signal transduction,35 pointing to the hierarchical control of AR-mediated gene expression for downstream AR-dependent growth factor signaling. Nuclear FoxO1 extrusion by increased growth factor signaling and upregulation of AR transcriptional activity will thus augment the expression of a substantial set of AR-responsive target genes involved in acne pathogenesis. FoxO1 regulation of AR activity at the genomic level is the connecting piece explaining the functional interaction of insulin/IGF-1 and androgens in the pathogenesis of acne.

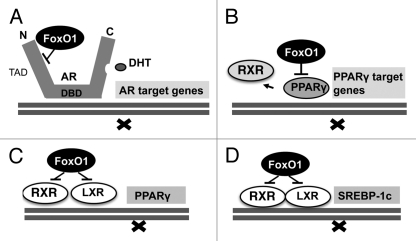

Figure 2.

(A) FoxO1-mediated suppression of androgen-receptor (AR) by FoxO1-binding to the AR transcription activation domain (TAD) thereby inhibiting N-/C-terminal interaction of AR resulting in reduced AR transactivation. (B) Direct FoxO1-mediated suppression of PPARγ-regulated target genes. (C) FoxO1-mediated suppression of the PPARγ promoter reducing PPARγ expression. (D) FoxO1-mediated suppression of the SREBP-1c promoter reducing SREBP-1c expression, the key transcription factor of most lipogenic enzymes. DBD, DNA binding domain; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; RXR, retinoid X receptor; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ.

Moreover, like an amplification loop, AR receptor signaling increased IGF-1-expression and IGF-1/IGF-1 receptor (IGF1R)-signaling in the ventral prostate gland.35 Oral isotretinoin treatment has recently been shown to decrease serum IGF-1 levels,36 which may decrease AR-mediated gene expression. Furthermore, decreased AR protein levels have been observed in skin of male acne patients after oral isotretinoin treatment.37 These data imply that isotretinoin treatment may downregulate the transcriptional activity of AR by increasing the nuclear concentration of the AR cosuppressor FoxO1. Furthermore, the isotretinoin-induced decrease of IGF-1 serum levels may impair IGF-1/PI3K/Akt-mediated nuclear export of FoxO1. Moreover, IGF-1 is regarded as an androgen-dependent stimulator of 5α-reductase activity.38 In fact, experimental evidence has been provided for decreased androgen 5α-reduction in skin and liver of men with severe acne after oral isotretnoin treatment.39 The isotretinoin-induced decrease of IGF-1 may reduce the conversion of less potent testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT), thereby decreasing the activity status of the AR ligand binding domain, which binds DHT 10 times stronger than testosterone. Free bioactive IGF-1 is controlled by IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs). In human dermal papilla cells, ATRA induced a significant increase of IGFBP-3,40 which reduced the bioavailability of free IGF-1 for IGF-1/IGF1R-signaling with potential impact on nuclear FoxO1 import. Thus, at least four mechanisms of isotretinoin treatment may explain reduced AR transcriptional activity affecting both the FoxO1 regulated N-terminal TAD and the androgen-regulated C-terminal AR ligand binding domain (Fig. 2A).

Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Polymorphism and Acne Relapse after Isotretinoin

The high prevalence of acne (>80%) in adolescents of industrialized countries with western life style as well as the increasing persistence of acne into adulthood clearly points to the predominace of environmental and nutrional factors in acne.41,42 However, there is also clear evidence for a genetic disposition for acne from various twin studies. Sebum excretion exhibited higher correlations in monozygotic vs. dizygotic twins.43 The proportion of branched fatty acids in the fraction of sebaceous wax esters highly correlated in monozygotic compared with dizygotic twins.44 Apolipoprotein A1 serum levels were significantly lower in acne twins and a family history of acne was also significantly associated with an increased risk of developing acne.45 A clinical study evaluating the role of heredity confirmed the importance of heredity as a prognostic factor for the development of acne and showed that a family history of acne is associated with earlier occurrence of the disease, increased number of retentional lesions and therapeutic difficulties.46 Especially, the risk for a relapse after oral isotretinoin treatment was significantly higher in the population of patients with a positive family history of acne.46

AR polymorphism with shortened CAG repeats (<20) encoding the polyglutamine tract of the N-terminal TAD domain of the AR has been associated with increased genetic disopistion for acne and other androgen-driven diseases like hirsutism and androgenetic alopecia.47–49 On the other hand, AR polymorphism with extended CAG repeats results in androgen insensitivity as observed in Kenendy syndrome.27,50 The N-terminal TAD domain of the AR is the interacting site for AR corregulators,29,31 which modify N-terminal-C-terminal interaction of the AR protein most important in the regulation of AR transcriptional activity.29 Intriguingly, FoxO1 binds to the N-terminal domain of AR and inhibits N-terminal/C-terminal interaction of the AR.32 It is conceivable that a shorter polyglutamine tract of the AR (CAG repeats <20) decreases the ability and affinity for FoxO1 binding, thus increasing coactivator binding and raising the basal state of AR transcriptional activity. Impaired FoxO1 binding to ARs with TAD with shortened polyglutamine tracts could thus explain the increased susceptibility for acne of individuals with AR polymorphisms with shortened CAG repeats (<20) in comparsion with individuals with normal (>20) or extended CAG repeats (>30). In acne patients with shortened CAG repeats, isotretinoin-induced upregulation of nuclear FoxO1 would thus have less inhibitory effects on AR transcriptional activity. Impaired FoxO1-AR-TAD interactions may explain the necessity for higher isotretinoin doses to reach therapeutical effects. Taken together, dimished FoxO1 interaction with ARs with shortened polyglutamine tracts (CAG repeats <20) may explain increased relapse rates of isotretinoin treatment in patients with a high genetic disposition for acne due to AR polymorphism with reduced CAG repeat numbers.

The Potential Role of FoxO1 for Isotretinoin's Sebum Suppressive Effect

Isotretinoin is the strongest known sebum suppressive drug for the treatment of acne. The sebaceous gland is actively involved in lipid metabolism. Isotretinoin is the most effective retinoid in reducing sebaceous gland size (up to 90%), by decreasing proliferation, disturbing the differentiation of basal sebocytes and suppressing sebum production in vivo.51 During isotretinoin treatment a marked decrease of wax esters, a limited decrease of squalene and a relative increase of cholesterol concentration has been detected in skin surface lipids.52 Oral isotretinoin was also shown to decrease glyceride fraction, whereas the relative composition of free sterols and total ceramides were increased in comedonal lipids.53 Isotretinoin exerts pronounced, direct inhibitory effects on proliferation, lipid synthesis and differentiation of human sebocytes in vitro.54 Inhibition of sebocyte proliferation and lipid synthesis were found to be independent mechanisms of isotretinoin activity.55 Eight weeks of isotretinoin treatment downregulated numerous genes encoding lipid-metabolizing enzymes involved in the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids and fatty acids and increased the expression of genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins like collagen and fibrobectin.56,57 To understand the sebum suppressive effect of isotretinoin, the inbibtory effects of isotretinoin (1) on sebocyte lipid synthesis, (2) the inhibition of sebocyte proliferation, (3) isotretinoin's effect on sebocyte apoptosis and (4) isotretinoin's effects on sebocyte stem cell homeostasis have to be elucidated. Evidence from translational research points to the involvement of the FoxO transcription factors FoxO1 and and FoxO3a in all four aspects of isotretinoin action.

Isotretinoin, FoxO1 and Inhibition of Lipid Metabolism

The sebaceous gland belongs to the type of glands and organs with most active lipid biosynthesis. FoxO transcription factors play a critical role in metabolism and especially in lipid metabolism.19,58 FoxOs have been implicated in regulating cellular proliferation, stress resistance, apoptosis and longevity. Through the insulin receptor substrate/PI3K/Akt signal cascade, FoxO1 integrates insulin action with the systemic nutrient and energy homeostasis. FoxOs are expressed ubiquitously in mammalian tissues, especially adipose, brain, heart, liver, lung, ovary, pancreas, prostate, skin, skeletal muscle, spleen, thymus and testis.19 Recently, FoxO1 protein has been detected in human sebaceous glands by immune histochemistry (Liakou A, Zouboulis CC, personal communication).

FoxO1 and PPARγ.

In human sebocytes, testosterone alone is not able to induce the full program of sebaceous lipogenesis.59,60 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and their ligands have been identified as important coregulators for sebaceous lipogenesis.61 Specific agonists of each PPAR isoform (α, δ and γ) stimulate sebocyte differentiation. Fatty acids of n-3- and n-6 origin and their eicosanoid derivatives play an important role as natural PPAR ligands that modulate PPAR function. PPARγ and its natural ligand prostaglandin J2 are most important in the regulation of lipid metabolism, sebaceous gland development and function. PPARγ plays a significant role in mediating insulin sensitivity, glucose and lipid homeostasis, and is expressed on sebocytes increasing human sebum production.62,63 PPARγ is transrepressed by FoxO1 like AR (Fig. 2B). FoxO1 directly binds and represses the PPARγ2 promoter as well as PPARγ function.64,65 It has been shown in adipocytes that growth factor signaling with reduced nuclear FoxO1 concentrations augments PPARγ activity required for terminal differentiation and prevents FoxO1-PPARγ interaction which rescues transrepression of genes involved in lipogenesis.66 In fact, serum IGF-1 levels correlate with facial sebum excretion.67 PPARγ heterodimerizes with RXR and binds to PPAR response elements (PPRE) in promoters of target genes. One mechanism by which FoxO1 antagonizes PPARγ activity is through disruption of DNA binding as FoxO1 inhibits the DNA binding activity of the PPARγ/RXRα heterodimeric complexes which have recently been detected in sebocytes (Fig. 2B). Thus, growth factor signaling inhibits the transrepressive effect of FoxO1 on AR and PPARγ/RXRα heterodimers, thus amplifying the complete program of sebaceous lipogenesis.

FoxO1, LXR and SREBP1.

Liver X receptors (LXRs) like PPARs play a critical role in lipid metabolism. Expression of LXRα and LXRβ has been detected in SZ95 sebocytes and LXR ligands enhance the expression of LXRα stimulating lipid synthesis.68 LXRs directly control the expression of sterol response element binding protein-1 (SREBP-1).69 A LXRE motif is present in the PPARγ promoter, on which LXRα/RXRα heterodimer is bound and activated by a LXR ligand.70 (Fig. 2C) In SZ95 sebocytes activation of LXRα induced lipid synthesis that was accompanied with the induction of SREBP-1 and PPARs.68,71 In SEB-1 sebocytes, IGF-1 induced SREBP-1 expression and increased lipogenesis via activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.72 FoxO1 plays an important role in the regulation of the SREBP-1c promoter activity. In skeletal muscle, SREBP-1c expression is regulated by LXRα/RXRα heterodimer and RXRγ or RXRα, together with LXRα have been shown to activate the SREBP-1c promoter,73 whereas the expression of FoxO1 negatively correlated with SREBP-1c expression (Fig. 2D). Thus, evidence from translational research corroborates the fundamental impact of nuclear FoxO1 on the regulation and SREBP-1c expression, the key transcription factor of multiple lipogenic target genes expressed in adipocyte, hepatocyte, skeletal muscle and sebocyte. Taken together, research data from various cell types with prominent lipid synthesis exhibit the suppressive regulatory effect of nuclear FoxO1 in direct transcriptional regulation of AR and PPARγ as well as coregulation of PPARγ/RXRα and LXR/RXRα heterodimers (Fig. 2).

Isotretinoin, FoxO1 and the Regulation of Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis

Isotretinoin has been found to be superior to other non-aromatic retinoids, such as tretinoin and alitretinoin, in reducing sebocyte proliferation and suppressing sebum production.74 This superior effect of isotretinoin has been attributed to the delayed initiation of retinoid inactivation under incubation of sebocytes with isotretinoin, a fact that leads to high intracellular ATRA concentrations. In contrast, incubation with ATRA leads to rapid enhancement of cellular retinoic acid binding protein-2 (CRABP-2) expression, which reduces the free intracellular concentration of ATRA through promotion of its metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzymes, and by induction of CYP1A1 expression, a major xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme, in cultured sebocytes.5 The antiproliferative activity of retinoids on human sebocytes and rat preputial sebocyte-like cells in vitro was found to be mediated by RAR.5,75

Isotretinoin exerts a dose- and time-dependent antiproliferative effect on SEB-1 sebocytes and immortalized SZ95 sebocytes.5,55,76,77 A portion of this decrease was attributed to cell cycle arrest at the G1/S phase of the cell cycle, as evidenced by decreased DNA synthesis, increased p21 protein and decreased cyclin D1 protein.76 Isotretinoin-induced apoptosis was not apparent within the first 24-hour treatment period.78 Marginal induction of apoptosis in SEB-1 sebocytes by isotretinoin was detected after 48 and 72 hours of treatment which already points to delayed secondary responses of transcriptional regulation. The ability of isotretinoin to induce sebocyte apoptosis was not recapitulated by alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) or ATRA. The induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by isotretinoin was specific to sebocytes, as the compound failed to induce apoptosis in HaCaT keratinocytes or normal human epidermal keratinocytes.76 Furthermore, the RAR pan-antagonist AGN 193109 did not inhibit the apoptosis induced by isotretinoin which suggested an RAR-independent apoptotic mechanism. These observations have been interpreted in a way that, in sebocytes, isotretinoin causes inhibition of cell proliferation after intracellular metabolism to ATRA by an RAR-mediated pathway and cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by an RAR-independent mechanism, which contributes to its sebosuppressive effect. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by isotretinoin is likely to contribute to the overall effect on suppression of sebum, but isotretinoin also inhibits sebaceous lipid synthesis by an RAR- and RXR-mediated pathway.2,7,76

FoxOs and cell cycle arrest.

There is compelling evidence that retinoids alter the expression of FoxO transcription factors.8–10 It could be shown in neuroblastoma cells that ATRA induced increased expression of FoxO3a.9 ATRA treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells increased nuclear levels of FoxO3a which was associated with granulocytic differentiation and apoptosis.10 FoxO3a is the strongest activator of the FoxO1 promoter, thus increasing the transcription of FoxO1.11 Upregulation of FoxO3a correlated with the expression of FoxO target genes p27, p130 and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD).9 FoxO expression induces a cell cycle exit into quiescence. Increased expression of p130 protein is often associated with cell cycle exit and an entry into quiescence or senescence (Fig. 3).79,80 Intriguingly, the pattern of ATRA-activated FoxO target genes of cell cycle arrest just resembles the observed changes of cell cycle proteins in isotretinoin-treated SEB-1 sebocytes like upregulation of p21 and downregulation of cyclin D1 (Table 1).76 Recent studies on isotretinoin-induced changes in gene expression and apoptosis focused primarily on the regulatory role of RAR and RXR.78 However, it appears that not the primary ATRA-RAR/RXR interactions are responsible for the proapoptotic effect of isotretinoin but secondary responses due to upregulation of FoxO-transcription factors. Upregulated nuclear FoxO transcription factors are pivotal inducers of apoptosis in various cell systems.8,10,11,14,15 Increased CRABP-2 expression has been detected in suprabasal sebocytes of sebaceous follicles of isotretinoin-treated acne patients.81 CRABP-2 was strongly expressed in sebocytes compared to epidermis of isotretinoin-treated patients, pointing to a preferential transport of ATRA to RARs in sebocytes. Proapoptotic actitivies of ATRA are mediated predominantly by RAR and CRABP-2, its cognate intracellular lipid binding protein which delivers ATRA to RAR, whereas fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP-5) shuttles the hormone to PPARβ/δ which exert pro-proliferative responses like those observed in keratinocytes.82

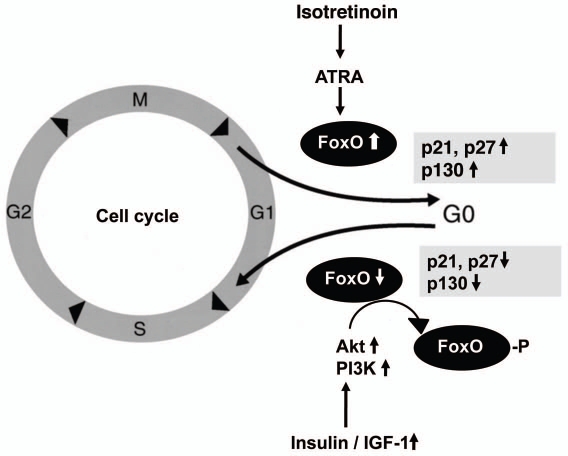

Figure 3.

FoxO-induced G1/S arrest of the cell cycle. Isotretinoin-mediated upregulation of cell cycle inhibitors p21 and p27 by FoxO binding to their promoters. Growth factor-mediated nuclear export of FoxO proteins with consecutive downregualtion of p21, p27 and p130. ATRA, all-trans-retinoic acid; Akt, Akt kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositol-3 kinase; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1.

Table 1.

Overlapping gene regulatory functions of FoxO proteins and isotretinoin

| Genes & cell functions | FoxO proteins | Ref. | Isotretinoin | Ref. |

| Cyclin D1 ↓ | FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 | 11, 14, 15, 18, 110 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) | 76 |

| p21 ↑ | FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 | 11, 14, 15, 18, 110 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) | 76 |

| Apo C-III ↑ | FoxO1 | 191 | Isotretinoin (hepatocyte) | 190 |

| IGFBP-3 ↑ | FoxOs | 15 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) ATRA (dermal papilla cells) | 40, 85 |

| Defensin β1 ↑ | FoxO | 88 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) | 85 |

| DNA synthesis ↓ | FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 | 11, 14, 15, 18, 80, 110 | Isotretinoin | 76 |

| G1/S arrest ↑ | FoxOs | 11, 14, 15, 18, 80, 103, 110 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) | 76 |

| Apoptosis ↑ | FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4 | 11, 14, 15, 18, 80, 110 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) | 76 |

| Caspase 3 ↑ | FoxOs | 267 | Isotretinoin (sebocyte) Dalton's lymphoma ascites cells B16F-10 melanoma cells | 76, 281, 282 |

| ROS ↓ | FoxOs, FoxO3a | 171, 172 | Isotretinoin (leukocytes) | 169 |

| Lipogenesis ↓ | FoxO1 | 19 | Isotretinoin (sebocytes) Isotretinoin (keratinocytes) | 56, 76 |

| VLDL ↑ | FoxO1 | 19, 187, 188 | Isotretinoin (plasma) | 184 |

| Insulin resistance ↑ | FoxO1 | 19, 180 | Isotretinoin | 176, 177 |

| Androgen receptor ↓ | FoxO1 | 32–34 | Isotretinoin (skin) | 37 |

| MMP-2 ↓ MMP-9 ↓ | FoxO1a, FoxO3a | 140, 144, 145 | Isotretinoin (sebum & keratinocyte) | 139 |

The ability of ATRA to mediate proapoptotic signaling is thus cell specific and is associated with a high CRABP-2/FABP-5 ration which results in partitioning of ATRA to RAR signaling.82 ATRA-induced G1/G0 growth arrest of HL-60 cells is known to require the activation of the RARα and RXR.83 Interestingly, FoxO3 has been identified as a key regulator for ATRA-induced apoptosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia.10 These data show that beside the sebocyte various other cell types are susceptible for isotretinoin/ATRA-induced apoptosis.84

There is substantiated evidence that several transcription factors including FoxOs act downstream of ATRA.8 The high correlation of gene-regulatory effects between known apoptotic mechanisms of FoxO-transcription factors and isotretinoin-induced apoptosis in SEB-1 sebocytes corroborates the suggestion that isotretinoin mediates its antiproliferative and apoptotic effects by upregulation of FoxO transcription factors, especially FoxO1 and FoxO3a (Table 1).13

NGAL and IGFBP-3.

Isotretinoin treatment of acne patients significantly upregulated the expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), which has been identified as an inducer of isotretinoin-mediated sebocyte apoptosis.85 However, other NGAL-independent mediators of apoptosis could not be excluded. Both isotretinoin and ATRA increased the expression of NGAL in SEB-1 sebocytes ten-fold and seven-fold, respectively.85 This similar range of NGAL expression allows the conclusion that NGAL-mediated apoptosis is not a specific mechanism of isotretinoin-induced sebocyte apoptosis. Remarkably, a 3.43-fold increased expression of IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) during isotretinoin treatment was exclusively observed in sebocytes but not in whole skin.85 The expression of IGFBP-3 has been shown to be retinoid responsive. For instance, IGFBP-3 is upregulated by ATRA in human dermal papilla cells.40 IGFBP-3 is a peculiar IGF-1 binding protein, which translocates into the nucleus and interferes with RAR/RXR leading to changes of receptor transactivation.86,87 Nuclear IGFBP-3 is a potent inducer of apoptosis.86 Intriguingly, IGFBP-3 is a known FoxO target gene.15 In prostate cancer cells IGFBP-3 enhanced RXR response element and inhibited RARE signaling. Thus, RXRα-IGFBP-3 interaction leads to modulation of the transcriptional activity of RXRα which is essential for mediating the effects of IGFBP-3 on apoptosis.86 There might be a common unifying mechanisms of NGAL- and IGFBP-3-mediated sebocyte apoptosis. The promoter region of the LCN2 gene contains consensus sequences for binding both RAR- and RXR.85 FoxO-mediated upregulation of IGFBP-3 may interact with RXR on the LCN2 promoter thus activating the expression of NGAL. This proposed FoxO/IGFBP-3-mediated gene regulatory mechanism of apoptosis would perfectly fit into FoxOs' biological role as inducers of apoptosis, metabolic rest (transcription factor of starvation) and activator of innate immunity associated with increased expression of antimicrobial peptides like defensin-β1.88 Both antimicrobial peptides and NGAL function as effectors of innate immunity against microbial pathogens.85,88 Is is thus not surprising that the expression of defensin-β1 is upregulated by FoxO as well as isotretinoin treatment.85,88 Isotretinoin-induced FoxO-activation of the IGFBP-3 promoter might be the underlying cause of isotretinoin-induced sebocyte apoptosis by nuclear IGFBP-3 overexpression. IGFBP-3/RXRα-mediated apoptosis as well as FoxO1-mediated downregulation of the AR transcriptional activity, PPARγ function and SREBP-1c promoter activity all together could thus contribute to the sebum-suppressive and apoptotic effect of isotretinoin treatment.

Isotretinoin-induced nuclear overexpression of FoxO1 and IGFBP-3 might also mediate the anti-comedogenic effects of isotretinoin as upregulated IGFBP-3 suppresses proliferation of transient amplifying keratinocytes.89 Comedo formation results from increased proliferation and retention of infundibular keratinocytes.90 The antiproliferative activity of nuclear IGFBP-3 has also been confirmed in myeloid leukemia cells, while IGFBP-3 enhances signaling through RXR/RXR homodimers, it blunts signaling by activated RAR/RXR heterodimers.91 In human breast cancer, ATRA mediated IGFBP-3-promoted apoptosis by enhancing the activity of RXRα.92 Thus, FoxO-mediated antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects may explain the chemopreventive activity of isotretinoin in certain types of cancers.

Does Isotretinoin Induce FoxO-Mediated Sebocyte and Sebocyte Stem Cell Arrest?

Fascinating research of the last years has elucidated various signals controlling sebocyte differentiation in vivo and major signaling pathways regulating differentiation of the sebaceous gland, recently reviewed in this journal.93 Activation of c-myc and hedgehog signaling cascades and repression of β-catenin signaling are important for the differentiation and maturation process experienced by sebocytes. They are essential inductive events responsible for the morphogenesis of the sebaceous gland during embryonal and neonatal development.93 There is good evidence that activation of c-myc in mouse skin results in enhanced sebaceous gland morphogenesis,94,95 and induction of sebocyte cell fate even within the interfollicular epidermis.96 The effect of c-myc is somewhat surprising because c-myc is reported to act downstream of β-catenin and is a direct target gene of canonical Wingless (Wnt) signaling.97,98 In skin, c-myc and β-catenin exert opposing effects on sebocyte differentiation. Analysis of transgenic mice with simultaneous activation of c-myc and β-catenin revealed mutual antagonism: c-myc blocked β-catenin-mediated formation of ectopic hair follicles and β-catenin reduced c-myc-stimulated sebocyte differentiation.99 Pulse-chase experiments in mouse skin suggested the existence of slow-cycling cells in the gland and a small cluster of cells at the base of the sebaceous glands expressed the transcriptional repressor Blimp1.100,101 Blimp1-expressing cells were suggested to be progenitors that give rise to all cells within the sebaceous gland. However, the functional signaling relationship between Blimp1 and c-myc is currently contradictory. On one hand, Blimp1 is not selectively expressed in sebaceous gland progenitor cells, but is also expressed by terminally differentiating cells in the interfollicular epidermis, sebaceous gland and hair follicle.99,102 A recent study implies that Blimp-1 is expressed late in embryonic development and is restricted to the evolving sebaceous gland and Blimp-1 labels only the most mature cellular constituents.102 More confusing is the fact that despite Blimp1's known negative regulation of the c-myc promoter,101 no correlation between Blimp1 and c-myc levels has been found in individual human sebaceous cells.99 This contradiction suggested that additional factors regulate levels of c-myc protein in sebocytes.99 Do FoxO transcription factors represent the missing link to understand these controversies in c-myc regulation?

FoxOs and c-myc.

FoxO transcription factors have been identified as important regulators of stem cell homeostasis.103 FoxOs play an increasing physiological role in the maintenance and integrity of stem cell compartments in a broad spectrum of tissues.103 For instance, FoxOs cooperate to affect quiescence of hematopoietic stem stells by regulation of mediators of the G0/G1 and G1/S arrest including Rb/p130, cyclin G2, p27, p57, p21 and cyclin D2.103 FoxO-mediated stem cell regulation of stem cell quiescence resembles isotretinoin-mediated effects on sebocyte cell cycle arrest. Thus, the question arises whether isotretinoin's sebumsuppressive effects are related to FoxO-induced quiescence of sebocyte stem cells? Recent evidence points to a substantial molecular cross talk between FoxO and c-myc dependent signal transduction.104,105 In colon cancer cells, induction of the transcriptional repressor protein Mxi1-SRα of the Mad/Mxd family of proteins by FoxO3a repressed myc-dependent gene expression.104 FoxO3a activation induced a switch in promoter occupancy from myc to Mxi1 on the E-box containing promoter regions of two studied myc target genes. siRNA-mediated transient silencing of Mxi1 or all Mad/Mxd proteins reduced exit from S phase in response to FoxO3a activation and stable silencing of Mxi1 or Mad1 reduced the growth inhibitory effect of FoxO3a. Thus, the induction of Mad/Mxd proteins contributes to the inhibition of proliferation in response to FoxO3a activation. Direct regulation of Mxi1 by FoxO3a appears to be an additional mechanism through which the PI3K/Akt/FoxO pathway can modulate c-myc function.104

There is another important connection bewteen FoxO and c-myc regulation of the p27 cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor. It has been shown in murine WEHI 231 immature B lymphoma cells that inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling decreased the levels of NFκB and c-myc, which has been shown to repress p27 promoter activity.105 p27 is coordinately regulated via two arms of a signaling pathway that are inversely controlled upon inhibition of PI3K: induction of the activator FoxO3a and downregulation of the repressor c-myc.105 FoxO1a, FoxO3a and FoxO4 transactivate the p27 promoter.105 FoxO3a induced p27 transcription and apoptosis of Ba/F3 cells.106 The p27 cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor plays an essential role in transition through the G1 phase, in particular the restriction point, via binding to and inhibiting such complexes as cyclin E-CDK2 and cyclin-A CDK2.107 There is strong evidence that FoxOs induce G1 arrest through expression of p27, p21 and p130 and increase the duration of the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inducing cyclin G2 (Fig. 3).80,108–112

Assuming that this regulatory mechanism operates in sebocytes and sebocyte stem cells as well, the reciprocal control of FoxO3a and c-myc via the PI3K pathway could modify sebcaous gland proliferation via p27 regulation. High levels of growth factors, insulin and IGF-1 in puberty, hyperinsulinemic western diet (hyperglycemic carbohydrates and insulinotropic milk) or acne-associated syndromes with insulin resistance would trans-locate FoxOs from the nucleus by increased PI3K/Akt singaling, whereas isotretinoin treatment with proposed upregulation of FoxOs counterbalances the effect of increased growth factor signaling in acne and downregualtes increased sebocyte proliferation and induces sebocyte apoptosis, the main regulatory features of FoxO transcription factors (Fig. 3).

Sox9, FoxO and β-catenin.

The earliest known signal necessary for sebaceous gland development is the transcription factor Sox9.113 The Sox family of transcription factors has emerged as modulators of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and diverse disease contexts, recently reviewed elsewhere.114 Sox physically interact with β-catenin and modulate the transcription of Wnt-target genes.114 On the other hand, Wnt signaling also regulates Sox expression resulting in feedback regulatory loops that fine tune cellular responses to β-catenin/Tcf activity.114 Sox9 in mouse intestinal epithelium requires Wnt signaling, but Sox9 then locally attenuates Wnt-target gene expression.115,116 These observations clearly demonstrate, that β-catenin maintains a molecular cross-talk with other transcription factors, especially in early steps of stem cell regulation.

FoxO transcription factors not only interact with c-myc signaling but also interact with β-catenin signaling and may be a modulating element between c-myc-driven sebocyte proliferation and Wnt/β-catenin-regulated sebaceous gland morphogenesis. Blocking canonical Wnt signalling during skin development by expression of a dominant negative mutant transcription factor Lef1 (ΔNLef1) results in transdifferentiation of hair follicle keratinocytes into mature sebocytes.117,118 A high proportion of human sebaceous adenomas and sebaceomas exhibit double nucleotide mutations within the β-catenin binding domain of the lef1 gene. These mutations within the NH2 terminus of Lef1 prevent β-catenin binding and inhibit expression of β-catenin target genes.119 Transgenic mice expressing N-terminally deleted ΔNLef1 in the skin develop spontaneous sebaceous tumours.118 Suppression in Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity by overexpression of Smad7 with accelerated cytoplasmic β-catenin degradation resulted in increased sebaceous gland morphogenesis and increased sebocyte differentiation.120 Sebaceous gland hyperplasia observed in aged UV-exposed skin exhibits upregulation of Smad7 expression,121 which is associated with reduced β-catenin levels.120

Thus, there is good evidence that suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes sebocyte differention. c-myk is reported to be a direct target gene of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling and to act downstram of β-catenin.97,98 Therefore, it should be expected that downregulation of β-catenin would suppress c-myc as well. However, it is surprising that activation of c-myc in mouse skin enhanced sebaceous gland morphogenesis,94,95 and induced a sebocyte cell fate even within the interfollicular epidermis.96 c-myc and β-catenin exert thus opposing effects on sebocyte differentiation. Analysis of transgenic mice with simultaneous activation of c-myc and β-catenin revealed this mutual antagonism: c-myc blocked β-catenin-mediated formation of ectopic hair follicles and β-catenin reduced c-mycstimulated sebocyte differentiation.99

Does Isotretinoin Inhibit AR-Mediated Suppression of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling?

Wingless proteins (Wnts) are secreted lipid-modified proteins that bind to a receptor complex comprising frizzled and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 or 6 (LRP5 or LRP6).122 Activation of this receptor complex by Wnts leads to inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), which prevents the proteosomal degradation of the transcriptional coactivator β-catenin and, thereby, promotes its accumulation in the cytoplasm. β-Catenin translocates into the nucleus where it associates with the T-cell factor (Tcf)/lymphoid-enhancer binding factor (Lef) family of transcription factors and regulates the expression of Wnt target genes.122

There is recent evidence for a cross-regulation of signaling pathways of nuclear hormone receptors with the canonical Wnt pathway.123 The best characterized interaction between nuclear hormone receptors and the canonical Wnt pathway stems from the discovery that RAR binds directly to β-catenin in breast cancer cells.124 ATRA decreased the activity of the β-catenin-Lef/Tcf signaling pathway. β-catenin interacted directly with the RAR in a retinoid-dependent manner, but not with RXR and RAR competed with Tcf for β-catenin binding.124 Similar interactions have been discovered for vitamin D receptor (VDR), PPARγ, RXR, LXRα and β, estrogen receptor (ER) and AR.123

AR and β-catenin interact by direct binding and complexing, AR/β-catenin interactions are ligand sensitive, whereby complexing occurs in the presence of dihydrotestosterone (DHT).125 Intriguingly, AR has an inhibitory effect on Tcf/Lef-mediated transcription and can compete with Tcf/Lef molecules for β-catenin binding.126–128 Repression of the β-catenin/Tcf signaling is mediated by ligand-occupied AR that is in competition with Tcf for nuclear β-catenin.128 As outlined above, inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf/Lef-signaling is a requirement for sebocyte differentiation. The reciprocal relationship between AR and β-catenin on Tcf/Lef-mediated transcription allows the conclusion that a decrease in liganded AR would increase β-catenin-mediated Tcf/Lef-signaling, thus inhibiting sebocyte differentiation. Remarkably, a significant reduction in AR protein expression in skin of acne patients has been observed during oral isotretinoin treatment.37 However, the time course of reduced AR expression in skin after a usual 3 to 4 month lasting isotretinoin treatment is not known. Moreover, the role of AR and FoxOs in sebocyte stem cell homeostasis has not been studied but may contribute to a prolonged downregulation of Wnt signaling in sebaceous stem cells. It is conceivable that an impairment of sebaceous stem cells would contribute to insufficient epidermal regeneration after epithelial injury. The clinical observation of impaired wound healing after systemic isotretinoin treatment might find here a plausible explanation. Thus, further studies with cultured sebocytes, human sebaceous glands and stem cells should address the possible FoxO1/AR and AR/β-catenin interaction in the presence or absence of isotretinion.

Parallels between Adipocyte and Sebocyte Differentiation

There are striking similarities in the regulation of Wnt signaling between sebocyte differentiation and adipogenesis. As already outlined, reduced Wnt signaling is required for sebocyte differentiation, whereas increased Wnt signaling inhibits sebocyte differentiation.93 When Wnt signaling is off, adipogenesis is initiated, when it is on, adipogenesis is repressed.129 Thus, Wnt signaling like FoxO1 functions as a lipogenic switch. Wnt signaling maintains preadipocytes in an undifferentiated state through inhibition of the adipogenic transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) and PPARγ.129 High expression of C/EBPα, C/EBPβ and PPARγ has been detected in immortalized SZ95 sebocytes which is important for sebocyte differentiation and sebaceous lipogenesis.130 Intriguingly, the master transcription factors C/EBPα and PPARγ are under direct or indirect control by members of the FOX family.131–133 Expression of FoxO1, FoxO3a and FoxO4 is increased during adipogenesis coincident with expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα, but FoxO1 activation is delayed until the end of clonal expansion.133 Remarkably, expression of constitutively active FoxO1 mutants prevent the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes in adipocytes.131,132 Oral isotretinoin treatment is expected to force high expression of FoxO3a and FoxO1, which may inhibit sebocyte C/EBPα and PPARγ activity. Thus, evidence from translational research clearly demonstrates that FoxOs are involved in the regulation of AR, c-myc, C/EBPα, PPARγ; LXRα and SREBP-1c, all important regulatory transcription factors involved in differentiation of actively lipid synthesizing cells like sebocytes.

There is another regulatory metabolic relationship between Wnt signaling and ATRA. Wnt suppresses CYP26, an enzyme that is responsible for degrading ATRA into inactive metabolites.134 Low Wnt signaling would result in less CYP26 suppression with low levels of ATRA, whereas high Wnt signaling would have a stronger inhibitory effect on CYP26 resulting in high ATRA levels. In isotretinoin-treated sebocytes, high intracellular ATRA levels due to isotretinoin isomerization resemble a constellation of high Wnt signaling, thus suppressing sebocyte differentiation.

FoxO Proteins Interact with β-Catenin

Recent evidence corroborated the important role of Wnt signaling for sebocyte differentiation and sebaceous gland morphogenesis.93,99 In 2005, Essers et al. reported an evolutionarily conserved interaction between β-catenin and FoxO proteins.135 In mammalian cells, β-catenin interacts with FoxO1 and FoxO3a. This interaction requires armadillo repeats 1 to 8 of β-catenin and the C-terminal half of FoxO proteins.135 Binding of β-catenin to FoxO enhances the transcriptional activity of FoxO.135 Interestingly, high Wnt signaling with elevated levels of β-catenin are known to inhibit sebaceous gland morphogenesis and sebocyte differentiation. It is conceivable that high nuclear levels of β-catenin bind to FoxO3a and FoxO1 and augment their transcriptional proapoptotic effects.14,15,19 It is well demonstrated that FoxOs and Tcf factors compete for the limited nuclear pool of β-catenin.136,137 These observations confirm the pivotal role of the evolutionarily conserved FoxO/β-catenin interaction and provide new insights into the complex signaling network of AR, FoxO, Wnt, Sox, β-catenin and c-myc in the development and homeostasis of the sebaceous gland.

Retinoids modify this regulatory network at multiple sites: ATRA induces upregulation FoxO3a.9,10 Moreover, the Wnt pathway can moduclate RAR signaling and vice versa.123 ATRA decreases c-myc-dependent target genes.124 Isotretinoin reduces IGF-1 serum levels.36 The activated PI3K/Akt pathway promotes FoxO shuttling from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, inhibits GSK3β which prevents proteasomal degradation of β-catenin.125 These data imply that a forced intracellular upregulation of ATRA by isotretinoin administration interferes with the activity of multiple important transcription factors involved in gene regulation orchestrated by FoxO transcription factors.

Isotretinoin and FoxO-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Isotretinoin treatment in acne exerts various anti-inflammatory effects including modulation of metalloproteinase function, downregulation of reactive oxygen formation, inhibition of pro-inflammatory NFκB-mediated cytokine signaling and modulation of acquired and innate immunity. It will be shown that upregulated FoxO transcription factors are again most likely candidates which mediate all these anti-inflammatory effects.

FoxOs and metalloproteinases.

Isotretinoin is known to inhibit scarring in acne and affects dermal tissue remodeling. NFκB and activator protein-1 are activated in acne lesions with consequent elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines and matrix degrading metalloproteinases (MMPs). These elevated gene products have been shown to be molecular mediators of inflammation and collagen degradation in acne lesions in vivo.138 Sebum contains proMMP-9, which was decreased following per os or topical treatment with isotretinoin in parallel to the clinical improvement of acne. Sebum also contains MMP-1, MMP-13, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and TIMP-2, but only MMP-13 was decreased following treatment with isotretinoin. The origin of MMPs and TIMPs in sebum is attributed to keratinocytes and sebocytes, since HaCaT keratinocytes in culture secrete proMMP-2, proMMP-9, MMP-1, MMP-13, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. SZ95 sebocytes in culture secreted proMMP-2 and proMMP-9. Isotretinoin inhibited the arachidonic acid-induced secretion and mRNA expression of proMMP-2 and -9 in both cell types and of MMP-13 in HaCaT keratinocytes.139

Thus, there is evidence for the influence of isotretinoin on the regulation of certain MMPs, however there is little information on its regulatory role at the level of gene transcription. The question arises whether FoxOs may regulate the promoter activity of certain MMPs? Interestingly, Tanaka et al. recently investigated the effect of UV-induced changes in FoxO1a expression and the roles of FoxO1a in the regulation of collagen synthesis and MMP expression in human dermal fibroblasts.140 It should be emphasized that primarly the dermal compartment with its fibroblasts and not the keratinocytes and sebocytes is the primary target of tissue destruction and remodeling in acne. Interestingly, in UVA- or UVB-irradiated fibroblasts the expression of FoxO1a mRNA decreased significantly. The expression of type I collagen also decreased. On the other hand, MMP-1 and MMP-2 mRNA levels increased. FoxO1a small interfering RNA transfection induced the downregulation of FoxO1a expression, it also induced a decrease in type 1 collagen expression, and it increased MMP-1 and MMP-2 expression. In contrast, the addition of FoxO1a-peptide induced an increase in type 1 collagen expression and decreased in MMP-1 and MMP-2 expression.140 Therefore it was concluded that FoxO1a plays a substantial role in skin photoaging, and control of FoxO1a may be a novel approach to prevent the collagen deficiency observed in photoaged skin. This is exactly the rationale of topical ATRA-treatment for aged, UV-damaged skin: to increase collagen synthesis and to reduce the activity of matrix degrading MMPs.141,142

There is even more evidence for the regulatory role of FoxOs in MMP expression. In endothelial cells certain vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-responsive genes require FoxO1 activity for optimal expression like MMP-10.143 Furthermore, resveratrol, a PI3K inhibitor, can enhance the apoptosis-inducing potential of TRAIL by activating FoxO3a and its target genes associated with an inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression.144 Astrocyte-elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) has been reported to be upregulated in several malignant cells and plays a critical role in Ha-ras-mediated oncogenesis through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Interestingly, AEG-1 knockdown induced cell apoptosis through upregulation of FoxO3a activity. This alteration of FoxO3a activity was dependent on reduction of Akt activity in LNCaP and PC-3 cells. AEG-1 knockdown was associated with increased levels of FoxO3a and attenuated the expression of MMP-9.145 In vascular smooth muscel cells, the C-terminal transactivation domain of FoxO4 is required for FoxO4-activated MMP-9 transcription. FoxO4 activates transcription of the MMP-9 gene in response to tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) signaling.146 FoxO4 activates the MMP-9 promoter by binding to the transcription factor Sp1, whereas FoxO1 failed to activate the MMP-9 promoter.146 These data show that distinct FoxO isoforms are able to regulate or coregulate MMP promoters thus linking MMP activity to FoxO signaling. Together, there is an overlap in the inhibitory acitivity of FoxO1 and FoxO3a and isotretinoin, respectively, regulating the expression of MMP-1, MMP-2 and MMP-3. In conclusion, isotretinoin's suppressive effect on MMP expression can be well explained by isotretinoin-induced upregulation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a modifying MMP promoter activity.

Isotretinoin, FoxOs, TLRs and NFκB signaling.

The growth factor-stimulated PI3K/Akt pathway activates NFκB signaling that inhibits apoptosis and triggers inflammatory responses and mediates just the opposite of FoxO-mediated gene transcription.147 Acne in puberty and acne-associated syndromes are associated with increased insulin/IGF-1 signaling.12,20,21 Excessive insulin/IGF-1 signaling activates the Akt/IKK/NFκB pathway.147 The canonical pathway of NFκB activation transduces signals from Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and several cytokine receptors like interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) mainly to the IKKβ kinase.148,149

Activation of PI3K/Akt signaling by IGF-1 has been shown to increase SREBP-1 expression and sebaceous lipogenesis.72 Sebaceous triglycerides are a preferred nutrient source of P. acnes, a critical milieu factor for P. acnes follicular hypercolonization and biofilm formation which trigger TLR-signaling of surrounding cells of the follicular environment. Indeed, TLR expression was found to be increased in the epidermis of acne lesions (TLR2, TLR4) and macrophages (TLR2) in which P. acnes induced cytokine production through a TLR2-dependent pathway.150,151 Distinct strains of P. acnes induced selective human β-defensin-2 and IL-8 expression in human keratinocytes through TLRs.152 P. acnes, by acting on TLR2, activates NFκB and stimulates the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 by follicular keratinocytes and IL-8 and IL-12 by macrophages, giving rise to inflammation. Thus, TLRs play an important role in the induction of innate immunity and inflammatory cytokine responses in acne.153 Both, the insulin/IGF-1-mediated upregulation of Akt-mediated NFκB-signaling and P. acnes-TLR-mediated NFκB-signaling contribute to the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in acne. Intriguingly, TLR2 contains a PI3K binding motif and activation of PI3K is particularly important for TLR2 signaling.154 In response to bacterial ligands, Src family kinases initiate TLR2-associated signaling, followed by recruitment of PI3K and phospholipase Cγ necessary for the downstream activation of proinflammatory gene transcription.155 PI3K activation is not only associated with TLR signaling but as well as with IL-1/IL-1R signaling, which both converge in increased activation of NFκB.147 Furthermore, a direct interaction between PI3K and TLRs or their adaptor proteins, such as MyD88, has been reported.154,156 Thus, growth factor-signaling via PI3K/Akt/NFκB as well as TLR2/PI3K/Akt/NFκB signal transduction are integrated at the level of Akt activation most likely resulting in a nuclear deficiency of FoxOs. Isotretinoin treatment with upregulation of FoxOs will counterbalance the nuclear FoxO deficiency of growth factor-activated PI3K/Akt and will thereby attenuate PI3K/Akt-mediated proinflammatory NFκB signaling.

In a vicious cycle, P. acnes might stimulate TLR2 on sebocytes which further increase PI3K/Akt-mediated sebaceous lipogenesis. TLR2 and TLR4 are constitutively expressed on SZ95 sebocytes.157 Interestingly, P. acnes exposure to hamster sebaceous glands has been shown to augment lipogenesis in vivo and in vitro.158 This observation implicates that TLR2-mediated PI3K/Akt activation might not only be involved in the stimulation of inflammatory responses to P. acnes but also to P. acnes-triggered TLR2/PI3K/Akt-stimulated sebaceous lipogenesis. Downregulation of PI3K/Akt-mediated sebaceous lipogenesis by isotretinoin-induced upregulation of nuclear FoxOs would just impair lipogenesis and reduce the lipophilic follicular milieu for P. acnes overgrowth and P. acnes-mediated proinflammatory TLR2/PI3K/Akt/NFκB signal transduction.

Isotretinoin, FoxOs and Acquired Immunity

It is well known that isotretinoin exerts anti-inflammatory activity.2,3 Recent studies have highlighted a fundamental role for FoxO transcription factors in immune system homeostasis.159 In vitro overexpression studies suggested that FoxO1 and FoxO3a are important for growth factor withdrawal-induced lymphocyte cell death. Moreover, FoxO factors importantly regulate cell cycle progression of lymphocytes. FoxOs are of pivotal importance for the control of lymphocyte homeostasis including critical functions in the termination and resolution of an immune response.

There is a functional link between upregulated TLR2-signaling in acne with increased interleukin-1α (IL-1α) production and T-cell mediated acquired immunity because selected IL-1 receptor associated kinases (IRAK-1, 2, M and 4) are bifunctional and can be recruited either to the TLR complex and thus mediate TLR-signaling or can associate with adapter proteins involved in T- and B-cell receptor-mediated signaling pathways linking TLR/IRAK signaling to adaptive immune responses.160 ATRA has been shown to downregulate TLR2 expression and function.161 TLR2/PI3K-signaling appears to be the connecting element between upregulated innate and adaptive immune responses in acne. Increased CD4+ T cell infiltration and IL-1 activity has been detected in acne-prone skin areas prior to follicular hyperkeratinization and comedo formation.162

Intriguingly, FoxO family members play critical roles in the suppression of T cell activation and T cell homing.16–18 FoxO1 deficiency in vivo resulted in spontaneous T cell activation and effector differentiation.17,18 Functional studies validated interleukin 7 receptor-α (IL-7Rα) as a FoxO1 target gene essential for FoxO1 maintenance of naïve T cells. These findings reveal crucial functions of FoxO1-dependent transcription in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. FoxO1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and IL-7Rα.163

Isotretinoin, FoxOs and Innate Immunity

There is new evidence that metabolism and growth factor status determine the activity of genes involved in innate immunity which may play a role in P. acnes hypercolonization. A recent study underlined the pivotal role of FoxOs in the regulation of innate immunity.88 In Drosophila flies FoxO transcription factor control the expression of several antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in various tissues including skin.88 AMP induction is lost in foxo null mutants but enhanced when FoxO is overexpressed. In Drosophila, AMP activation can be achieved independently of immunoregulatory pathogen-dependent pathways by FoxO, indicating the existence of cross-regulation of metabolism and innate immunity at the promoter level of FoxO-activated AMP genes.88 In contrast, insulin and IGF-1 dependent signaling with Akt-mediated translocation of FoxO from the nucleus into the cytosol reduces the expression of AMPs. It is thus conceivable that insulinotropic western diet (milk, dairy and hyperglycemic carbohydrates) affects the balance and activity of AMPs. We have to ask whether insulinotropic western diet impairs innate immunity of the pilosebaceous follicle in such a way that P. acnes hypercolonization is promoted. Both isotretinoin-induced upregulation of FoxO1 with reduced sebaceous lipogenesis and isotretinoin-induced stimulation of the AMP response are synergistic mechanisms which could explain isotretinoin's suppressive effects on sebaceous lipogenesis, P. acnes growth and bacterial follicular colonization.

Taken together, isotretinoin-mediated upregulation of FoxO1 may exert anti-inflammatory effects by downregualtion of T-cell responses and upregulation of innate immunity.16–18 In contrast, growth factor (insulin, IGF-1, FGF)-induced nuclear deficiency of FoxOs would activate T-cell proliferation and decreases expression of AMPs. A decrease of AMPs would increase the number of pathogens (P. acnes) stimulating TLR-induced proinflammatory genes. These pro-inflammatory changes of acquired and innate immunity in acne may be counterbalanced by isotretinoin-mediated upregulation of FoxO1.

FoxO1 and Isotretinoin-Mediated Suppression of Oxidative Stress

Isotretinoin treatment in acne and rosacea has beneficial effects due to its ability to suppress the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The ability of neutrophils to produce ROS was significantly increased in patients with inflammatory acne.164 The involvement of ROS generated by neutrophils appears to play an important role in the disruption of the integrity of the follicular epithelium promoting inflammatory processes of acne. Patients with inflammatory acne showed a significantly increased level of hydrogen peroxide produced by neutrophils compared to patients with comedonal acne and healthy controls.165 In acne patients, lower levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase have been measured in polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) in comparison to controls, which may be responsible for the increased levels of superoxide anion radicals in the epidermis.166–168 The effect of isotretinoin on the generation of ROS by stimulated human neutrophils showed that isotretinoin exerted an antioxidant activity against the superoxide anion.169

One of the most important functions of FoxOs is the protection of cells from oxidative damage by increasing transcription of multiple genes regulating scavenging of ROS.14,18 Activated FoxO proteins promote stress resistance by binding to the promoters of the genes encoding manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and catalase, two scavenger enzymes that play essential roles in oxidative detoxification in mammals.11,135,170–172 FoxO-mediated oxidative-stress resistance is influenced by multiple other pathways like β-catenin which binds directly to FoxO proteins and enhances their transcriptional activity in mammalian cells.135

Moreover, FoxO1 conrols the promoter activity of the key enzyme of cytochrome synthesis, heme oxigenase.173 Upregulated FoxO1 downregulates the synthesis of heme, the prothetic group of hemoglobin and various cytochromes of the mitochondrial respiratory chain involved in ROS formation.173 Thus, isotretinoin-induced upregulation of FoxO1 explains the suppression of mitochondrial ROS generation and increased ROS catabolism thereby normalizing increased ROS generation in acne.

FoxO-Upregulation Explains all Adverse Effects of Isotretinoin Therapy

All patients treated with isotretinoin suffer from multiple side effects. This already shows that isotretinoin affects other organ systems. The side-effect profiles qualitatively resemble toxic effects of vitamin A or hypervitaminosis A syndrome.174

FoxO1 and Isotretinoin-Induced Hepatotoxicity

In approximately 15–20% of patients treated with isotretinoin mild-to-moderate transitory elevations of mitochondrial liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) have been observed.175 Circulating levels of alkaline phosphatase, lactic dehydrogenase and bilirubin may also become elevated during retinoid therapy.2,175 Again, we have to ask whether upregulated hepatic FoxO1 is the common cause of liver toxicity resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction with increased release of mitochondrial enzymes and increase in bilirubin?

The critical role of FoxO1 in hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism is well established and reviewed extensively elsewhere in reference 19. Under ordinary conditions, feeding stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, and FoxO1 in the liver is inhibited by insulin signal via IRS/PI3K/Akt cascade (Fig. 1). In fasting state, insulin signal is weak and FoxO1 is activated by translocation into the nuclei to trigger gluconeogenesis for glucose supply. Under insulin resistance conditions, however, hyperactive FoxO1 promotes gluconeogenesis in such an uncontrolled way that it leads to hyperglycemia. It is well known that isotretinoin impairs insulin resistance.176,177 This fact can be well explained by FoxO1-mediated upregulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), the key enzyme of gluconeogenesis.19 Thus, hyperactive FoxO1 explains impaired insulin sensitivity and an increased disposition for hyperglycemia observed under isotretinoin treatment (Fig. 4).

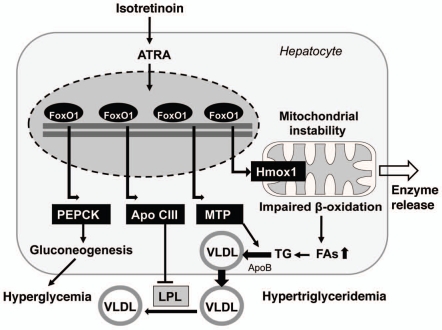

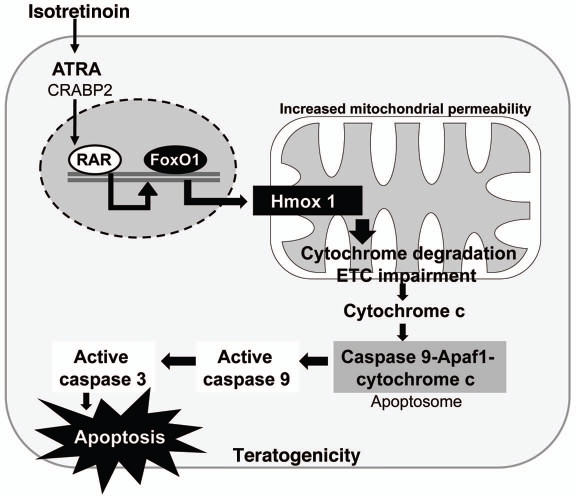

Figure 4.

Isotretinoin/FoxO1-mediated upregulation of hepatic gene expression at the promoter level: upregulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) results in gluconeogenesis; upregulation of apolipoprotein C-III (Apo CIII) inhibits the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL); upregulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) leads to increased production and secretion of very low density lipoproteins (VLDL). Increased expression of heme oxigenase 1 (Hmox1) results in cytochrome degradation and mitochondrial damage with impaired β-oxidation of fatty acids (FAs) leading to increased formation of hepatic triglycerides (TG).

Furthermore, recent observations indicate that activated FoxO1 impairs fatty acid oxidation. A hepatic increase in fatty acids may promote dyslipidemia which may arise at least in part from mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 4).178–180 By directly binding the promoter, FoxO1 induces heme oxigenase-1 (Hmox1) that reduces the heme content required for expression, stability and function of electron transport chain (ETC) components.178,181 Heme is the functional prosthetic group of all cytochromes in the liver which drive the mitochondrial ETC. FoxO1-mediated induction of Hmox1 disrupts the ETC and impairs mitochondrial metabolism including fatty acid β-oxidation. Hyperactivated FoxO during severe insulin resistance contributes to the accumulation of hepatic lipids.178–180 Adenoviral delivery of constitutively nuclear FoxO1 to mouse liver promotes hepatic triglyceride accumulation that can progress to steatosis as seen in hypervitaminosis A syndrome.180 The lipid accumulation is associated with decreased fatty acid oxidation. In rats, administration of isotretinoin (100 mg/kg diet) increased the total hepatic lipid and triglyceride content as well as serum triglyceride concentrations.182

FoxO1 mediated increase in heme oxigenase-1 with resultant mitochondrial dysfunction is of fundamental biological importance and explains the isotretinoin-mediated increase of mitochondrial liver enzymes. ATRA, alitretinoin and isotretinoin are able to induce membrane permeability transition observed as swelling and decrease in membrane potential in isolated rat liver cells (Fig. 4).183 Isotretinoin appeared to be the most effective and stimulated the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, suggesting a potential target of retinoids in the induction of cell apoptosis.183 Isotretinoin's effect on mitochondrial permeability via FoxO1-mediated inhibition of the ETC not only explains the increased release of mitochondrial liver enzymens but also increased bilirubin levels following increased heme catabolism.

Remarkably, FoxO1-upregulated heme oxigenase-1 and disturbance of mitochondrial function and integrity may be an important trigger for the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. In this regard, isotretinoin mimics growth factor withdrawal with upregulation of FoxO1/heme oxigenase-induced intrinsic pathway of apoptosis mediated through mitochondrial instability (Fig. 4).

Togehter, the effects of isotretinoin on hepatic glucose, lipid and heme metabolism as well as mitochondria-dependend apoptosis may be well explained by isotretinoin-induced overexpression of hepatic FoxO1.

Isotretinoin-Induced Hypertriglyceridemia

Isotretinoin at pharmacological doses elevates plasma triglycerides and induces overt hypertriglyceridemia.184–186 There are at least three mechanisms involved in the generation of isotretinoin-induced hypertriglyceridema:

Hepatic triglycerides and free fatty acids are elevated by isotretinoin treatment as a result of FoxO1-mediated upregualtion of heme oxigenase-1 with impaired activity of the ETC and diminished fatty acid oxidation.179,180 Increased free fatty acids in the liver are incorporated into triglycerides.

Hepatic very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) production is facilitated by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) in a rate-limiting step that is regulated by insulin. In hepatocytes, FoxO1 binds and stimulates MTP promoter activity (Fig. 4). Mice that expressed a constitutively active FoxO1 transgene revealed enhanced MTP expression, augmented VLDL production and elevated plasma triglyceride levels.187 VLDL production is suppressed in response to increased insulin release after meals by insulin-mediated PI3K/Akt activation and reduction of nuclear levels of FoxO1.188 Thus, isotretinoin-induced upregulation of nuclear FoxO1 would nicely explain increased hepatic VLDL synthesis resulting in retinoid-induced hypertriglyceridemia.

A third mechanism provides indirect evidence for isotretinoin's ability to raise nuclear FoxO1 concentrations. Isotretinoin increases the expression of apolipoprotein C-III, a known antagonist of plasma triglyceride catabolism. Apo C-III functions as an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase.189 In fact, isotretinoin treatment resulted in elevated plasma levels of apo C-III.190 Recent studies confirmed that FoxO1 stimulated hepatic apo C-III expression and correlated with the ability of FoxO1 to bind to the apo C-III promoter.191 These observations clearly explain the basic mechanism of isotretinoin-mediated hypertriglyceridemia at the level of upregulated FoxO1-mediated gene transcription and are an excellent proof of the proposed role isotretinoin-induced FoxO transcription in hepatic lipid and lipoprotein metabolism.

Isotretinoin and FoxO1-Mediated Bone Toxicity

Isotretinoin in high doses and given over prolonged periods (>1 mg/kg body weight, >1 year) disturbs the physiological homeostasis of bone metabolism including demineralization, thinning of the bones and premature closure of the epiphyses as well as hyperostosis, periostosis (disseminated idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, DISH syndrome).192–196 It has been clearly demonstrated that treatment of rats with isotretinoin decreased bone mass.197 Bone mineral density, bone mineral content, bone diameter and cortical thickness of the femur were reduced in rats treated daily with 10 or 15 mg/kg ATRA or 30 mg/kg isotretinoin.197 In acne patients receiving high dose isotretinoin (1 mg/kg of body weight) bone density at the Ward triangle significantly decreased by a mean of 4.4% after 6 months of isotretinoin use and some patients showed decreased density of more than 9% at the Ward triangle.194 However, patients receiving a single course of isotretinoin treatment for 4–6 months until a cumulative dose of 120 mg/kg did not exhibit clinically significant effects on bone metabolism.195 Most hyperostoses are asymptomatic and clinically insignificant.2,196,198 High-dose isotretinoin for a period of over 2 years have been shown to appear to induce skeletal hyperostoses and anterior spinal ligament calcification. Bone abnormalities in children, particularly premature closure of the epiphyses, are associated with high isotretinoin doses (>1 mg/kg/day), vitamin A supplementation and long-term treatment.

Again the question: Is there a link between high levels of isotretinoin, FoxOs and bone metabolism? During the last decade, it has been extensively documented that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a critical determinant of bone mass.122 The paramount importance of the Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling for bone mass has been explained by the essential role of β-catenin in determining the commitment of multipotential mesenchymal progenitors to the osteoblastic lineage.199,200 In addition to promoting osteoblastogenesis, Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibits adipogenesis, an alternative fate of the multipotential mesenchymal progenitors, by blocking the expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα as already outline above.201 Similar to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, oxidative stress influences fundamental cellular processes including stem cell fate and has been linked to aging and the development of age-related diseases like osteoporosis. β-catenin has recently been implicated as a pivotal molecule in defense against oxidative stress by serving as a cofactor of FoxO transcription factors.122 In addition, it has been shown that oxidative stress is a pivotal pathogenetic factor of age-related bone loss and strength in mice, leading to a decrease in osteoblast number and bone formation. These particular cellular changes evidently result from diversion of the limited pool of β-catenin from Tcf- to FoxO-mediated transcription in osteoblastic cells (Fig. 5).135,137,202 Fascinatingly, attenuation of Wnt-mediated transcription has been linked not only to premature osteoporosis, but also to hyperlipidema, insulin resistance and diabetes—observed changes of isotretinoin treatment. It is thus conceivable that bone toxicity of isotretinoin may be mediated by increased nuclear FoxO levels which divert β-catenin from to Tcf-binding to FoxO-binding, thereby attenuating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the bone (Fig. 5).

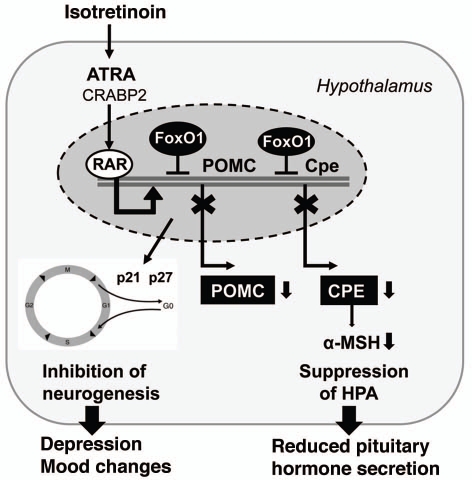

Figure 5.

Isotretinoin-mediated overexpression of FoxO proteins and divergence of β-cateinin signaling from Lef1/Tcf-induced transcription by increased binding of β-catenin to nuclear FoxO proteins. ATRA, all-trans-retinoic acid; CRABP2, cellular retinoic acid binding protein-2; Wnts, Wingless proteins; LRP5/6, low density receptor-related proteins 5/6; Frizzled, Wnt receptor Frizzled; β, β-catenin; Lef1, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor-1; Tcf, T cell factor.

Interestingly, ATRA treatment of mouse epiphyseal chondrocytes in culture increased Wnt/β-catenin signaling.203 Cross-regulation of Wnt signaling and retinoid signaling affect chondrocyte function and phenotype and could be quite important in the process of chondrogenesis and proper progression of enchondral ossification during skeletal growth.203 Thus, isotretinoin/FoxO-mediated attenuation of epiphyseal chondrocyte Wnt singaling may be a conceivable mechanism explaining premature closure of the epiphyses by isotretinoin treatment.

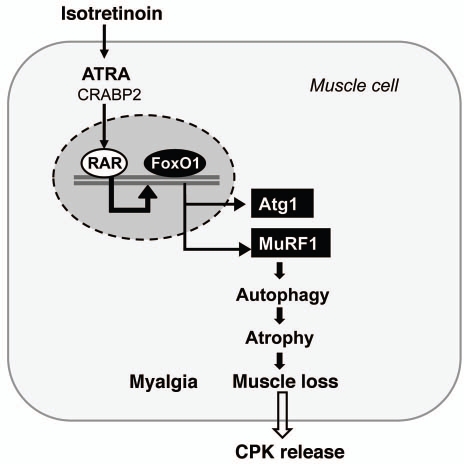

Isotretinoin and FoxO-Mediated Adverse Effects on Muscle

Arthralgias and myalgias may occur in up to 2–5% of individuals receiving oral isotretinoin in doses higher than 0.5 mg/kg/day and is more common in adolescents and young adults. In some cases severe muscle pain and temporary disability of movement with early-morning arthralgias were seen. Occasionally, concomitant malaise and fever and increases in creatine phosphokinase (CPK), a specific marker of muscle destruction, may be observed.2,204,205 CPK, has been found to be elevated, occasionally by up to 100 times the normal value with or without muscular symptoms and signs in a variable percentage of patients receiving isotretinoin treatment and particularly in those undergoing vigorous physical exercise.206