Abstract

Activation of Raf/Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and elevated expression of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) are associated with von Hippel–Lindau gene alterations in renal cell carcinoma. We postulated that the degree of MEK activation was related to graded expression of MT1-MMP and the resultant phenotype of renal epithelial tumors. Madin Darby canine kidney epithelial cells transfected with a MEK1 expression plasmid yielded populations with morphologic phenotypes ranging from epithelial, mixed epithelial/mesenchymal to mesenchymal. Clones were analyzed for MEK1 activity, MT1-MMP expression and extent of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Phenotypes of the MDCK-MEK1 clones were evaluated in vivo with nu/nu mice. Tissue microarray of renal cell cancers was quantitatively assessed for expression of phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP proteins and correlations drawn to Fuhrman nuclear grade. Graded increases in the MEK signaling module were associated with graded induction of epithelial–mesenchymal transition of the MDCK cells and induction of MT1-MMP transcription and synthesis. Inhibition of MEK1 and MT1-MMP activity reversed the epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Tumors generated by epithelial, mixed epithelial/mesenchymal and mesenchymal MDCK clones demonstrated a gradient of phenotypes extending from well-differentiated, fully encapsulated non-invasive tumors to tumors with an anaplastic morphology, high Fuhrman nuclear score, neoangiogenesis and invasion. Tumor microarray demonstrated a statistically significant association between the extent of phosphorylated MEK1, MT1-MMP expression and nuclear grade. We conclude that graded increases in the MEK1 signaling module are correlated with M1-MMP expression, renal epithelial cell tumor phenotype, invasive activity and nuclear grade. Phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP may represent novel, and mechanistic, biomarkers for the assessment of renal cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Recent insights into the molecular pathogenesis of renal cell carcinoma, particularly of the clear cell type, have made major contributions to our current understanding of this common neoplasia and have led to the development of potentially more effective therapies (1,2). Alterations in the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) gene, through mutation or inactivation by hypermethylation, with resultant accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIF-α) results in the transcriptional activation of a number of genes associated with tumorigenesis and neoangiogenesis (3). In addition, VHL inactivation can result in sustained oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling through the Akt-1 and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (Raf/MEK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades (4,5). MEK (also designated mitogen-activated protein kinase) exists in two isoforms (MEK1/MEK2) and is a dual-specificity kinase that binds to inactive MAPK. Upon activation of MEK kinase activity via phosphorylation by Raf, MEK phosphorylates MAPK, yielding an active kinase with multiple substrates, including transcription factors.

VHL inactivation in renal clear cell carcinoma also induces sustained phosphorylation and activation of the tyrosine kinase activity of the MET protein, which further contributes to tonic activation of the MAPK signaling cascade (6). Sustained activation of the MEK1 signaling module disrupts epithelial polarity in Madin Darby canine kidney (MDCK) renal epithelial cells and induces expression of membrane Type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP, also denoted MMP-14), suggesting that tonic activation of this signaling module contributes to the morphologic and phenotypic changes seen in renal cell carcinoma (7). In support of this, constitutive activation of the MEK/MAPK signaling pathway has been documented been in a variety of human tumors (8). Within the context of renal cell carcinoma, MAPK activation was observed in the majority of tumors and the extent of MAPK activity correlated with tumor grade (9).

Local invasion and distal metastasis are important predictors of clinical outcomes in renal cell carcinoma, and increased expression of several matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP-2, MMP-9 and MT1-MMP has been reported in clinical renal cell carcinoma tissues (10,11). Increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 correlates with poor prognostic features in renal cell carcinoma, including tumor grade and vascular invasion (12,13). The ability of tumor cells to successfully invade three-dimensional extracellular matrices is critically dependent upon the activity of the membrane-associated MMP class, particularly MT1-MMP (14–16). Petrella et al. (17,18) have recently identified MT1-MMP as a transcriptional target of HIF-2α and determined that the invasive activity of VHL−/− renal cell carcinoma cells in vitro was dependent upon MT1-MMP activity. In additional to transcriptional activation of MT1-MMP by HIF-2α, collagen-induced MT1-MMP synthesis in cultured endothelial cells is dependent upon the activity of the MEK1/MAPK signaling cascade (19). Furthermore, MT1-MMP exerts a positive feedback stimulatory effect on the MEK1/MAPK axis through transactivation of the EGFR (20), thereby stimulating cellular migration.

Given the above observations, we postulated that graded expression of active MEK1 would result in a co-ordinated graded induction of MT1-MMP synthesis that would progressively affect the invasive activity of tumor cells. To approach this issue, we generated clonal populations of MDCK renal epithelial cells expressing increasing amounts of constitutively active MEK1 protein. Graded expression of MEK1 correlated with progressive epithelial–mesenchymal transition, MT1-MMP expression and invasive activity in vitro and in vivo. These observations were validated by tissue microarray analysis of a panel of human renal cell carcinoma tissues, which demonstrated a significant association of tumor grade with levels of phosphorylated MEK1 protein and MT1-MMP expression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The renal epithelial MDCK cell line, the VHL+/+ renal cell carcinoma cell line Caki-1 and the VHL−/− renal cell carcinoma cell line 786-O were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured according the supplier’s instructions.

Generation of stable MEK1-MDCK transfectants

MDCK cells were cotransfected using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with pTK-hygro (50 ng; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and pUSEamp-MEK-HA (500 ng, Millipore, Billerica, MA). pUSEamp-MEK1-HA encodes a constitutively active MEK1 with substitution of aspartic acid for serines at 218 and 222 and an HA epitope tag. Control cells were transfected with pTK-hygro alone. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were selected with hygromycin (250 μg/ml). Six discrete clones with distinctive morphologic features on phase contrast microscopy ranging from epithelial to fully mesenchymal were derived by single cell cloning. These clones were characterized as detailed in the Results section. The clonal populations were expanded through five passages, harvested, aliquoted and frozen for use in subsequent experiments.

Quantitation of MEK1 activity in transfectants

Near-confluent cell layers from the respective MEK1 clones and control were washed twice in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested by scraping and spun at 400 g for 10 min. MEK1 activity was determined using a MEK1 immunoprecipitation kinase assay kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using 100 μg protein per sample. In this assay immunoprecipated MEK1 is used to phosphorylate recombinant inactive MAPK1. The phosphorylated MAPK1 is separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and detected by western blot using anti-phospho-MAPK1. Quantitation is performed by digital densitometry. All assays were performed in quadruplicate for each clonal line.

Immunohistochemistry

Cells cultured on etched glass coverslips were fixed for 20 min at 4°C with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde. Cells stained for vimentin were also permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. The slips were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 30 min (Vector, Burlingame, CA), rinsed and subsequently blocked with an avidin/biotin kit (Vector). For detection of vimentin, slips were incubated sequentially with anti-vimentin IgG1 (10 μg/ml, clone RV202; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 [5 μg/ml, Invitrogen, in 1% goat serum/PBS at 25°C for 2 h, followed by streptavidin–rhodamine (0.5 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch] in 0.1% bovine serum albumin/PBS for 30 min. For E-cadherin detection, cells were incubated with anti-E-cadherin IgG2a (10 μg/ml, clone 36; Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-IgG2a (5 μg/ml; Invitrogen) in 1% goat serum/PBS at 25°C for 2 h. For detection of the MEK1-HA epitope tag, slips were incubated with murine monoclonal anti-HA IgG (5 μg/ml in 1% goat serum/PBS at 25 C for 2 h, followed by streptavidine–rhodamine conjugate as detailed above.

Western blots

Total cellular extracts were generated by lysis of cells using T-Per (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total cell extracts (20 μg/sample) were resolved by reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen), blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and blocked overnight at 4°C in StartBlock (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For detection of MT1-MMP, the blots were incubated sequentially with rabbit anti-MT1-MMP antibody (1 μg/ml; Millipore) and horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 (20 ng/ml; Invitrogen) in StartBlock. Vimentin was detected using rabbit anti-vimentin (1 μg/ml; Abcam) and horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 (20 ng/ml; Invitrogen). E-cadherin was detected using anti-E-cadherin IgG2a (1 μg/ml, Clone 36; Transduction Laboratories) and goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 (20 ng/ml; Invitrogen). Peroxidase activity was detected by chemiluminescence with the ECL Plus detection system (GE Healthcare).

The protein content of the analyzed cellular extracts was individually confirmed prior to performance of the western blots to assure equal protein loading of the respective lanes. In addition, blots were probed with rabbit anti-GAPDH (1 μg/ml; Abcam), followed by development at detailed above.

Transient transfection with MT1-MMP luciferase reporter constructs

Subconfluent cultures of cells were washed and transfected with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) using 0.4 μg of plasmid DNA from the control pGL2-Basic luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI) or plasmid pMT1-Luc3329 (composed of the first 3329 bp of the murine MT1-MMP 5′ flanking region cloned into pGL2-Basic) and a normalizing pSV40-β-galactosidase plasmid (50 ng/sample; Promega). Luciferase activity was measured 48 h posttransfection (Luciferase Assay System; Promega) and normalized to β-Gal activity (Luminescent β-Gal Reporter System; Clontech) and sample protein concentration. Values reported are the means ± SDs of quadruplicate determinations.

To assess the transcriptional activity of MT1-MMP within the context of VHL+/+ and VHL−/− status, Caki-1 and 786-O renal cell carcinoma cell lines were transiently transfected as detailed above in the presence or absence of the EGFR/ErbB-2 inhibitor 4557W (2.5 μM; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or MET inhibitor K252a (10 nM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 48 h, followed by lysis and analysis as detailed above.

Measurement of MT1-MMP enzyme activity

Control and the respective MEK1 MDCK clones were grown to subconfluency, washed with 4°C PBS, and extracted with 50 mM Tris/HCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 0.01% (vol/vol) Nonident P-40 and 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Cell suspensions were incubated for 10 min at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 2500g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C until use. MT1-MMP activity was measured on 20 μg cellular protein samples with the Sensolyte 520 MMP-14 assay (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay uses a quenched FRET peptide substrate and was normalized using a standard curve generated with activated recombinant MT1-MMP protein (AnaSpec). Assays were performed in quadruplicate and data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

MT1-MMP inhibition studies

Control and MEK1-transformed MDCK cells with a fully mesenchymal phenotype (clone F, see Figure 1) were cultured in OptiMEM (Invitrogen). To inhibit MT1-MMP activity, cells were incubated for increasing time periods (0–96 h) with a murine monoclonal IgG1κ directed against the catalytic domain of the enzyme (10 μg/ml, clone LEM-2/15.6; Millipore) or with control murine IgG1κ at the same concentration. Monoclonal clone LEM-2/15.6 targets the amino acid sequence 218-233 within the catalytic domain of MT1-MMP and has been demonstrated to inhibit MT1-MMP activity (21). Cells were stained for expression of E-cadherin and vimentin as detailed above and western blots for E-cadherin and vimentin were performed as detailed above.

Fig. 1.

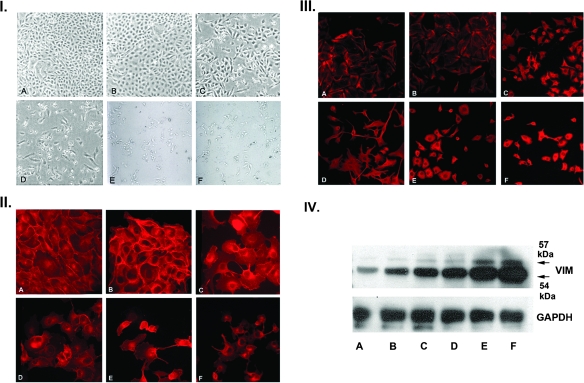

Generation and characterization of MDCK clones with a gradient of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Panel I: MDCK cells were stably transfected with constitutively active MEK1 and selected with hygromycin as detailed in Materials and Methods. Clones were derived from picked single cells and displayed a gradient of morphologic phenotypes by phase contrast microscopy ranging from fully epithelial (B), to a mixed intermediate phenotype (C and D), to a fibroblastic mesenchymal phenotype (E and F). Panel A is a control MDCK clone transfected with pTK-hydro alone. Panel II: Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of MDCK clones for E-cadherin. E-cadherin is progressively lost from junctional complexes as a function of the extent of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and assumes a primarily cytosolic and perinuclear distribution, particularly in the most mesenchymal E and F clones. Panel III: IF staining of MDCK clones for vimentin. In the epithelial clones, vimentin is found in a subcortical distribution, but as epithelial–mesenchymal transition progresses, there is dense cytocolic and perinuclear staining with vimentin arranged in cord-like bundles (I–III, ×200). Panel IV: Western blot analysis of vimentin in the MDCK clones. There is a progressive increase in the expression of vimentin in the MDCK clones as a function of the extent of epithelial–mesenchymal transition.

Invasion assay

The invasive activity of control and MEK1-MDCK clones was quantitatively determined using the Chemicon 96-well Collagen-Based Cell Invasion Assay Kit. Quadruplicate wells were loaded with 1 × 105 cells and the number of cells traversing the membranes determined at 48 h using CyQuant CR dye solution. The invasion assays were repeated three times.

In vivo subcutaneous tumor assay

Subconfluent cultures of three discrete MEK1 clones (clones B, D and F, see Figure 1) were washed in PBS, harvested by centrifugation and suspended in a 1:1 mixture of medium/Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cell suspensions (1 × 106) from the transfection controls and the respective MEK1 clones were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of groups of six athymic nu/nu female mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). The mice were killed at 4 weeks and excised tumors were fixed in buffered formalin, paraffin embedded and stained with hematoxylin/eosin. For MT1-MMP immunohistochemistry, the blocks were rehydrated, endogenous peroxide blocked and antigen retrieval performed with Sigma protease, 2 mg/ml for 10 min at 37° C. Following avidin/biotin block (Vector Laboratories), the sections were incubated for 90 min with a 1:10 dilution of biotinylated (ARK; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) primary anti-MT1-MMP murine monoclonal antibody (clone 113-5B7; Research Diagnostics, Flanders, NJ). Washed slides were incubated with streptavidin/horseradish peroxidase followed by development with diaminobenzidene (DAB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The counterstain was hematoxylin.

Tissue microarray staining for MT1-MMP and phospho-MEK1

Sequential sections of tissue microarray of human renal cancers (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) were stained for MT1-MMP and phospho-MEK1. MT1-MMP was stained as detailed above with the exception that the counterstain was methyl green. To detect phosphorylated MEK1, the avidin/biotin-blocked tissue arrays were stained with a rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-MEK1 antibody (20 μg/ml; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) for 90 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 (5 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and developed with DAB/hydrogen peroxide using standard methodology. Tumor nuclear grade was scored by an independent pathologist.

Quantitative chromogen detection was performed

The RGB image of an entire stained tissue section for each sample was captured at high resolution (1200 d.p.i.) and digitized under identical conditions. Each digitized image histogram was normalized using the ‘Image Adjust Auto tool’ of Adobe PhotoShop (version 7.0.1). In Adobe Photoshop, the DAB reaction product was selected using the ‘Magic Wand’ and ‘Select-Similar’ tools, and pixel intensity for the DAB reaction product was quantified using the ‘Edit-Selection-Select All’ and ‘Analyze-Measure’ tools within ImageJ (version 1.38x; National Institutes of Health). Pixel intensity for MT1-MMP or phospho-MEK1, for each tissue section, was graphically represented along with its corresponding Fuhrman nuclear grade. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the association of tumor grade with phospho-MEK1 and MT1-MMP protein intensities. The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test for differences in phospho-MEK1 and MT1-MMP across the four tumor grades.

Results and discussion

Stable transfection of the renal epithelial cell line MDCK with a constitutively active MEK1 construct resulted in a broad range of morphologic phenotypes. Observation of individual clonal populations by phase contrast microscopy indicated that the stable transfectants exhibited morphologic features extending from a conserved epithelial phenotype to a fully transitioned phenotype characterized by an extended and migratory fibroblastic morphology (Figure 1, panel I). Notably, a number of clones were observed with intermediate features common to both epithelial cells and fibroblasts when observed by phase contrast microscopy. For the purposes of this study, we isolated a panel of clonal populations with morphologic features extending from typical epithelial (clone B) through intermediate phenotypes (clones C and D) to fully fibroblastic phenotypes (clones E and F).

E-cadherin staining and organization were used as qualitative markers of the epithelial phenotype, whereas staining and organization of vimentin was used as a marker for the degree of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Control MDCK cells (Figure 1, panel II, A) and the epithelial clone (B) showed maintenance of cell surface staining characteristic of intact E-cadherin junctional complexes. The intermediate clones showed progressive dissolution of the junctional complexes with increased cytoplasmic localization of E-cadherin staining (C and D). E-cadherin distribution was primarily cytoplasmic in the fully fibroblastic clones (E and F).

Staining for vimentin revealed an inverted pattern of expression as the MDCK cells transitioned from the epithelial to mesenchymal phenotypes. Vimentin staining in the controls and the epithelial cell clones (Figure 1, panel III, A and B) was limited to a delicate filamentous pattern in a subcortical distribution. Vimentin staining progressively increased in intensity as the cells transitioned to the mesenchymal phenotype, with a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution (C and D). In the fully mesenchymal phenotypes, vimentin staining was intense and organized in dense filamentous structures with a predominantly perinuclear concentration (E and F). Vimentin exists as a 54 kDa non-phosphorylated form and as a 57 kDa phosphorylated form (22). The 57 kDa phosphorylated form regulates intermediate filament assembly and cellular migration (22,23). Western blots of the respective clones demonstrated a graded increase in both forms of vimentin as a function of the extent of epithelial–mesenchymal transformation (Figure 1, panel IV).

The level of measured MEK1 activity, as determined by the rates of phosphorylation of recombinant MAPK1 protein, showed a direct relationship with the extent of epithelial–mesenchymal transformation (Figure 2, Panel I). Control MDCK cells were assigned a relative MEK1 activity of 100%. Cells with an intermediate phenotype (clones C and D) showed relative MEK1 levels of 160 ± 14% and 210 ± 23%, respectively (P < 0.05 as compared with controls). MDCK clones with fully transformed mesenchymal phenotypes expressed relative MEK1 activities of 260 ± 22% and 280 ± 18%, respectively (P < 0.05 as compared with controls). Thus, relatively small, but sustained and graded increases in MEK1 activity are sufficient to induce graded degrees of epithelial–mesenchymal transformation.

Fig. 2.

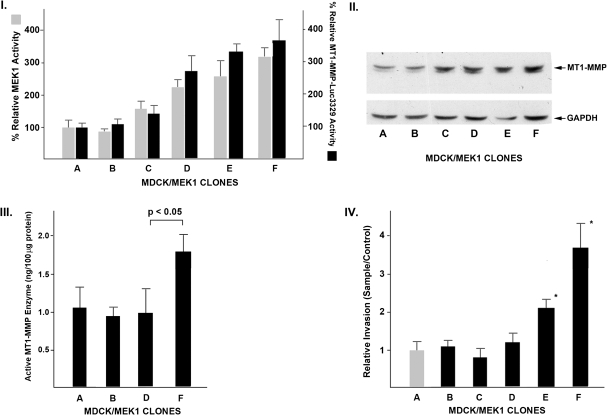

Quantitative analyses of MEK1 activity, MT1-MMP transcription rates, protein synthesis, MT1-MMP enzymatic activity and invasion. Panel I: MEK1 enzymatic activity was measured in the respective MDCK clones, with a value of 100% assigned to the control epithelial clone A (gray columns). MT1-MMP transcriptional activity was assessed as detailed in Materials and Methods using the murine MT1-MMP promoter driving a reporter luciferase cassette (black columns; Data are expressed as mean ± SD of quadruplicate determinations for each clone). Panel II: Western blot analysis of MDCK clone cell extracts for MT1-MMP. The dominant detected MT1-MMP band has the apparent molecular mass of the proenzyme form (62 kDa). Panel III: Quantitative MT1-MMP enzymatic assay of MDCK cellular extracts as detailed in Materials and Methods. Results are displayed as ng active MT1-MMP protein/100 μg cellular extract (mean ± 1 SD). Panel IV: Invasive activity of the respective control and MEK1-MDCK clones was performed as detailed in Materials and Methods using a collagen-based cell invasion kit (Data are expressed as mean ± SD of quadruplicate determinations; *P < 0.05 by t-test).

There was a similar relationship between the degree of epithelial–mesenchymal transformation and the levels of MT1-MMP transcription (Panel I) and protein synthesis (Panel II). Transcription rates for MT1-MMP as assessed with a luciferase reporter construct driven by the MT1-MMP promoter increased nearly 4-fold in the most transformed clones while the relative levels of MT1-MMP protein also increased by ∼4-fold. The dominant 62 kDa MT1-MMP band detected on the western blots conforms with the pro- or inactive form of MT1-MMP. The levels of enzymatically active MT1-MMP are highly regulated by a complex process of proenzyme secretion, membrane complex formation, catalytic activation, internalization, degradation or recycling (24–26). We therefore directly quantified the amounts of active MT1-MMP enzyme present in respective MDCK clones. As summarized in Figure 2, panel III, the epithelial clones (A and B) and intermediate clone (D) had similar levels of MT1-MMP enzyme activity (∼1.0 ng/100 μg cellular protein). The fully mesenchymal MDCK clone F had a higher MT1-MMP activity level of ∼1.7 ng/100 μg cellular protein. Thus, while MT1-MMP proenzyme protein progressively increases as a function of MEK1 activity, MT1-MMP enzymatic activity does not and is only elevated in the fully invasive MDCK clone.

Acquisition of an invasive phenotype is an important determinant of tumor behavior and ultimately of prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Although the prior figures describe a gradient of mesenchymal morphology, kinase activity and MT1-MMP transcription/translation across the MDCK/MEK clonal populations, this was not observed with a quantitative in vitro invasion assay. As summarized in Figure 2, panel IV, clones with intermediate (or mixed epithelial/mesenchymal) phenotypes (C and D) had the same levels of invasive activity observed in the fully epithelial cell clones (A and B). The fully mesenchymal clone F demonstrated a nearly 4-fold increase in invasive activity as compared with the other clones. Thus, acquisition of an invasive phenotype is a feature of MEK/MT1-MMP-dependent epithelial transformation seen only in those cells expressing the highest levels of MEK and higher levels of active MT1-MMP.

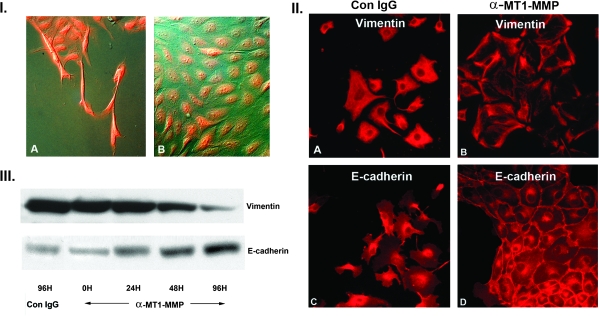

Both MEK1 and MT1-MMP enzymatic activity were required for the maintenance of MDCK epithelial–mesenchymal transformation. The fully mesenchymal MDCK clone F, at the 10 passage, was incubated for 48 h in the presence or absence of the selective MEK1 inhibitor, PD98059 (30 μM) and examined by immunofluorescence staining for the MEK1 protein and with Nomarksi optics to define cellular morphology. As shown in Figure 3, panel I, A, MDCK cells from clone F demonstrate an extended migratory morphology with prominent MEK1 protein staining. Inhibition of MEK1 activity reverts the cellular morphology from mesenchymal to fully epithelial (B). We also quantified the effects of selective MEK1 inhibition by PD98059 on MT1-MMP transcription rates. Incubation for 48 h with PD98059 decreased MT1-MMP relative transcriptional activity to 56 ± 24 relative luciferase units as compared with the control value of 245 ± 58 relative luciferase units (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

MEK1 and MT1-MMP enzymatic activity are required to maintain MEK1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Panel I: Mesenchymal clone F was incubated with the selective MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (30 μM) for 48 h, followed by immunofluoresence staining of the HA-MEK1 epitope tag. (A) Control clone F cells demonstrating extended migratory phenotype and bright MEK1 staining. (B) PD98059-treated cells showing reversion to a fully epithelial phenotype with persistent MEK1 protein staining (×300). Panel II: Mesenchymal MDCK clone F was incubated with control IgG or a monoclonal antibody directed against the catalytic site of MT1-MMP. Incubation with the anti-MT1-MMP antibody for 96 h reverts vimentin and E-cadherin distribution to an epithelial phenotype. (×300) Panel II: Western blot for vimentin and E-cadherin of clone F cells treated with control IgG or with anti-MT1-MMP antibody. There is a temporal increase in E-cadherin expression and a temporal decrease in vimentin expression.

As detailed in Figure 3, panel II, incubation of the fully mesenchymal clone F with a monoclonal antibody directed against the catalytic active site of the MT1-MMP protein induced a reversion to a fully epithelial cell phenotype, as demonstrated by morphology and immunohistochemical staining for E-cadherin and vimentin. Western blot analyses of MT1-MMP antibody-treated cells (panel III) show a progressive decrease in vimentin staining over a 96 h period while E-cadherin increased significantly at the same time point. Incubation with a control monoclonal IgG had no effect on vimentin or E-cadherin expression levels. Thus, sustained expression of both active MEK1 and active MT1-MMP are required for the maintenance of the mesenchymal phenotype. These findings confirm an absolute requirement for the integrity of the MEK1/MT1–MMP axis in maintaining MDCK epithelial–mesenchymal transformation.

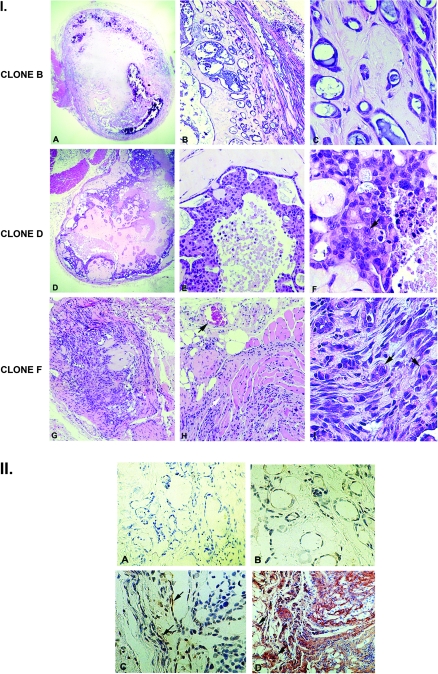

We assessed the tumor-forming properties of the MDCK-MEK clones in nu/nu mice. For these studies, mice received a subcutaneous flank injection of MDCK clones with an epithelial phenotype (clone B), an intermediate phenotype (clone D) and the fully mesenchymal invasive clone F. Representative sections are shown in Figure 4, Panel I. Tumors derived from the epithelial phenotype MDCK clone (panels A–C) were characterized as well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with developed tubulocystic structures and abundant intraluminal mucin. These tumors were relatively acellular within a dense stroma and surrounded by a very dense fibrous capsule. There was no evidence for local invasion or neoangiogenesis. The Fuhrman nuclear grade score for these tumors was 1.2 ± 0.2 (n = 50 scored nuclei).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of in vivo tumors generated by MDCK-MEK1 clones. Panel I: Cultures from the epithelial clone B, the intermediate clone D and the fully mesenchymal clone F were suspended in Matrigel and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nu/nu mice as detailed in Materials and Methods. Tumors were excised at 4 weeks for analysis. Epithelial clone B-derived tumors (A–C) have features typical of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma within a dense capsule with a relatively acellular stroma. Intermediate phenotype clone D-derived tumors (D–F) are encased in a dense capsule but are more cellular than the clone B-derived tumors. Mesenchymal phenotype clone F-derived tumors are highly cellular with an anaplastic morphology (arrows, I), with local invasion and neoangiogenesis (arrow, H) (A, D and G ×40; B, E and H ×200; C, F and I ×400). Panel II: Tumors derived from epithelial clone B intermediate phenotype clone D and fully mesenchymal phenotype clone F were stained for MT1-MMP as detailed in Materials and Methods. (A) Negative antibody control. (B) There is no detectable MT1-MMP staining in the clone B-derived tumors. (C) There is occasional MT1-MMP staining of cells lining epithelial cystic structures in the intermediate clone D tumor (arrows). (D) There is intense cellular staining of the highly invasive clone F-derived tumor, with prominent staining of columns of invasive cells (arrows) (×200).

Tumors derived from the MDCK clone with an intermediate mesenchymal phenotype (clone D) remained encased in a relatively dense capsule but were considerably more cellular with a Fuhrman nuclear score of 1.8 ± 0.5 (panels D–F, n = 50 scored nuclei). In contrast, tumors derived from the fully mesenchymal MDCK clone F were highly cellular, lacked capsule formation and demonstrated local invasion into the surrounding soft tissues and muscle (panels G–H). The cellular morphology was anaplastic in nature with a Fuhrman nuclear score of 3.6 ± 0.3 (n = 50 scored nuclei).

Immunohistochemical staining of the tumors for MT1-MMP expression was performed (Figure 4, panel II). There was little to no detectable MT1-MMP cellular expression in the tumors derived from the epithelial MDCK clones (B), whereas cells lining cystic structures were noted to express MT1-MMP in the tumors derived from the intermediate MDCK clone (C). There was intense cellular staining in the tumors derived from the fully mesenchymal MDCK clones, with prominent staining of columns of cells invading muscle and adipose tissue (D).

We next examined the relationship between VHL status, EGFR and MET signaling with rates of MT1-MMP transcription and synthesis using VHL+/+ Caki-1 clear cell carcinoma cells and VHL−/− 786-0 clear cell carcinoma cells. These studies are summarized in Figure 5. MT1-MMP transcription rates were approximately six times greater in the VHL−/− 786-O cells as compared with the VHL+/+ Caki-1 cells (Figure 5, Panel 1).

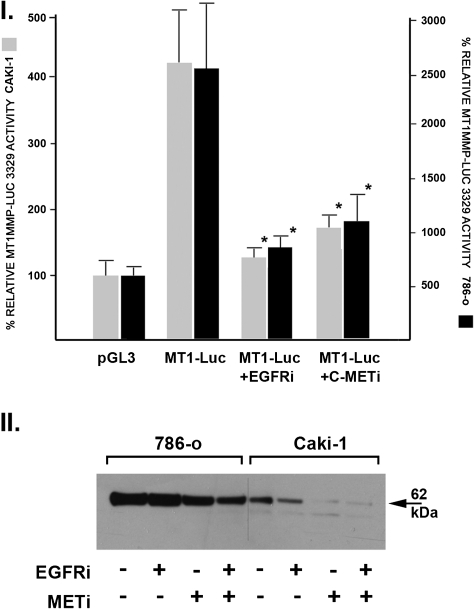

Fig. 5.

Relationship between VHL status and MT1-MMP transcription and synthesis—effects of EGFR and MET inhibition. Panel I: VHL+/+ Caki-1 and VHL−/− 786-O clear cell carcinoma cells were transiently transfected with the MT1-MMP luciferase reporter construct in the presence or absence of the EGFR inhibitor 4557w (2.5 μM) or the MET inhibitor K252a (10 nM). After 48 h, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity determined. Data expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate to quadruplicate measurements where the control pGL3 vector was assigned a relative activity of 100%. (*P < 0.05 as compared with untreated MT1-Luc activity by t-test). Panel II: Western blot analysis of Caki-1 and 786-0 cell lysates incubated for 48 h in the presence or absence of 4557w, K242a or the combination.

The effects of two signaling inhibitors on MT1-MMP transcription rates were also assessed. In the concentration used (10 nM), K252a is a potent and selective inhibitor of the receptor tyrosine kinase activity of c-MET (27). The compound 4557w [4-(4-benzyloxyanilino)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline] is a potent and selective inhibitor of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity (28). MT1-MMP transcription rates in both cell types were significantly reduced by either the EGFR or MET chemical inhibitors, indicating that basal transcription of MT1-MMP is primarily mediated by a constitutively active receptor tyrosine kinase-coupled Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling cascade.

Similar findings were observed in terms of MT1-MMP protein synthesis (Figure 5, Panel II). VHL+/+ Caki-1 cells synthesized approximately one-fifth the amount of MT1-MMP as compared with the VHL−/− 786-0 cells. MT1-MMP protein synthesis was inhibited by inclusion of the EGFR or MET inhibitors in the culture media. Thus, these experiments link VHL status with Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling and resultant MT1-MMP transcription and synthesis.

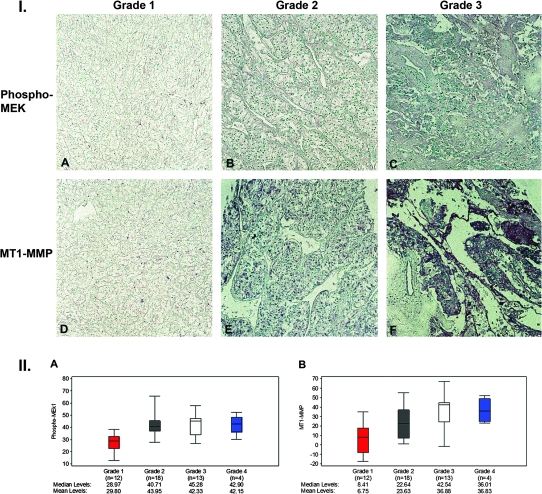

Tissue microarrays of controls and 49 specimens of renal cell carcinoma (42 clear cell type, 2 papillary type, 2 collecting duct type and 3 granular type) were stained for phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP. Digitized images of each specimen were then quantitatively assessed for the levels of phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP staining using the ImageJ software package and correlated with the corresponding Fuhrman nuclear grade. Representative sections from the tissue arrays are shown in Figure 6 and show a progressive increase in staining for phosphorylated MEK1 (A–C) and MT1-MMP (D–F) as a function of increasing Fuhrman nuclear grade. Figure 6 summarizes the quantitative assessment of phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP expression. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the association of tumor grade with phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP. Tumor grade is significantly associated with both phosphorylated MEK1 (r = 0.44, P = 0.002) and MT1-MMP (r = 0.56, P < 0.0001). The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test for differences in phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP levels across the four tumor grades. This test also revealed a significant difference in protein expression across tumor grades, both for phosphorylated MEK1 (P = 0.005) and MT1-MMP (P = 0.002).

Fig. 6.

Representative sections of sections from renal carcinoma tissue microarray stained for phospho-MEK1 and MT1-MMP and quantitative assessment of phosphor-MEK1 and MT1-MMP expression as a function of nuclear grade. Panel I: Tissue microarrays were stained for phosphor-MEK1 and MT1-MMP as detailed in Materials and Methods. Phospho-MEK1 and MT1-MMP expression are increased in tumors with higher Furhman nuclear grade (×200). Panel II: Digitized immunohistologic images were quantified for phosphor-MEK1 and MT1-MMP expression as detailed in Materials and Methods and analyzed according to nuclear grade. The median is indicated by the black center lie and the interquartile range (first and third quartiles) are the edges of the boxes. Whiskers denote Q1 −1.5 × interquartile range and Q3 +1.5 × interquartile range. Tumor grade is significantly associated with both phosphor-MEK1 and MT1-MMP (r = 0.44/P = 0.002 and r = 0.56/P < 0.0001, respectively, Spearman correlation coefficients).

Montesano et al. (7) first reported a relationship between high level MEK1 expression, elevated MT1-MMP synthesis and acquisition of an invasive phenotype in three-dimensional culture. In the current study, we have attempted to build on this initial observation and to provide a mechanistic linkage between graded activation of the MAPK/MT1–MMP axis and renal cell carcinoma phenotypic features directly associated with clinical outcomes. The levels of relative MEK1 activity in the MDCK clonal populations were in the same range as reported for human renal cell carcinoma samples (29), indicating that the observed phenotypes are unlikely to be the result of gross MEK1 overexpression. The functional linkage between both components of the MEK/MT1–MMP axis for the determination of the final cellular phenotype is underscored by the observation that expression of MT1-MMP alone in MDCK cells generates tumor cells that maintain a well-differentiated, fully epithelial non-invasive phenotype (30).

Sustained activation of the MEK signaling module undoubtedly alters the expression of numerous genes in addition to MT1-MMP. It is intriguing, however, that inhibition of MT1-MMP enzymatic activity with an antibody directed against the catalytic site is sufficient to revert fibroblastic, fully mesenchymal MDCK cells to a differentiated epithelial phenotype. Thus, both sustained MEK1 activity and MT1-MMP enzymatic activity are required for the development of the fully mesenchymal phenotype, but this phenotype cannot be maintained in the absence of MT1-MMP enzymatic activity.

The relationship between MEK1 and MT1-MMP is bidirectional. A recent study by Sounni et al. (31) demonstrated that binding of TIMP2 to cell surface MT1-MMP-stimulated cellular migration via activation of MEK1/2 phosphorylation, a process that occurs independently of MT1-MMP proteolytic activity (32). Thus, elevated expression of the MT1-MMP proenzyme is sufficient, via MEK1/2 phosphorylation, to induce proliferation and migration, whereas expression of the active enzyme is required for cellular invasion of extracellular matrices. Distinct roles of the catalytic and hemopexin domains of MT1-MMP have been defined in the epithelial–mesenchymal transformation of prostate cancer cells (33,34). This underscores the conclusion that MT1-MMP effects on cellular behavior are multilayered and involve both proteolytic and non-proteolytic activities that are intricately linked to activation of the MEK1/ERK signaling cascade.

MT1-MMP plays a critical role in the ability of tumor cells to invade three-dimensional extracellular matrices (14–16). In addition, MT1-MMP has been shown to induce aneuploidy and chromosomal instability in model epithelial cells systems (35–37). This process may provide an explanation for the association of higher tumor nuclear grade and anaplastic morphology with higher levels of MT1-MMP expression observed in this study.

Induction of MT1-MMP transcription by MEK1 signaling provides at least a partial mechanistic explanation for the efficacy of protein kinase inhibitors for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma (29). Furthermore, MT1-MMP protein synthesis is regulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (38,39) and the positive treatment results observed in some patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus may be, at least in part, a result of inhibition of MT1-MMP synthesis.

There is considerable interest in the identification and validation of biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma that are either associated with tumor behavior or response to treatment. The level of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression correlates with Fuhrman nuclear grade and the membrane-associated metalloproteinase ADAM has been associated with renal cell cancer progression (40,41). Our current findings suggest that expression of phosphorylated MEK1 and MT1-MMP may also provide new biomarkers that are mechanistically linked and represent potential treatment targets.

Funding

NIH (DK 39776 to D.H.L. and CA130860 to R.D.) and a Department of Veterans Affairs Career Development Award (M.A. A.-J.).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr T.S.B.Yen, Department of Pathology, UCSF, for his interpretation of the pathology.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DAB

diaminobenzidene

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDCK

Madin Darby canine kidney

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MT1-MMP

membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- VHL

von Hippel–Lindau

References

- 1.Clark PE. The role of VHL in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma and its relation to targeted therapy. Kidney Int. 2009;76:939–945. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dancey J. mTOR signaling and drug development in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010;7:209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossage L, et al. Alterations in VHL as potential biomarkers in renal-cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010;7:277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss in renal cell carcinoma promotes oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor signaling via Akt-1 and MEK-1. Eur. Urol. 2008;54:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunaratnam L, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor activates the transforming growth factor-α/epidermal growth factor receptor growth stimulatory pathway in VHL -/- renal cell carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44966–44974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakaigawa N, et al. Inactivation of von Hippel-Lindau gene induces constitutive phosphorylation of MET protein in clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3699–3705. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montesano R, et al. Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase MEK1 disrupts morphogenesis and induces an invasive phenotype in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:317–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshino R, et al. Constitutive activation of the 41-/43-kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human tumors. Oncogene. 1999;18:813–822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oka H, et al. Constitutive activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4182–4187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagemann T, et al. mRNA expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in subtypes of renal cell carcinomas. Eur. J. Cancer. 2001;37:1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katagawa Y, et al. Expression of messenger RNAs for membrane-type 1, 2, and 3 matrix metalloproteinases in human renal cell carcinomas. J. Urol. 1999;162:905–909. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199909010-00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiya N, et al. Increased in situ gelatinolytic activity in renal cell tumor tissues correlates with tumor size, grade and vessel invasion. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;106:480–485. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallakury BVS, et al. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 1 and 2 correlate with poor prognostic variables in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:3113–3119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiki M, et al. Roles of pericellular proteolysis by membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase in cancer invasion and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh Y, et al. MT1-MMP: a potent modifier of peri-cellular microenvironment. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;206:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotary K, et al. Regulation of cell invasion and morphogenesis in a three-dimensional Type I collagen matrix by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2 and 3. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:1309–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrella BL, et al. Identification of membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase as a target of hypoxia-inducible factor-2α in von Hippel Lindau renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:1043–1052. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrella BL, et al. Tumor cell invasion of von Hippel Lindau renal cell carcinoma cells is mediated by membrane type-I matrix metalloproteinase. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:66–80. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd PJ, et al. MAPK signaling regulates endothelial cell assembly into networks and expression of MT1-MMP and MMP-2. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C659–C668. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00211.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langlois S, et al. Membrane-Type 1 matrix metalloproteinase stimulates cell migration through epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:569–583. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matias-Roman S, et al. Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase is involved in migration of human monocytes and is regulated through their interaction with fibronectin or endothelium. Blood. 2005;105:3956–3964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson JE, et al. Specific in vivo phosphorylation sites determine the assembly dynamics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:919–932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barberis L, et al. Leukocyte transmigration is modulated by chemokine-mediated PI3Kgamma-dependent phosphorylation of vimentin. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1136–1146. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bravo-Cordero JJ, et al. MT1-MMP proinvasive activity is regulated by a novel Rab8-dependent exocytic pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26:1499–1510. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovett DH, et al. YB-1 alters MT1-MMP trafficking and stimulates MCF-7 breast tumor invasion and metastasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;398:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, et al. Co-recycling of MT1-MMP and MT3-MMP through the trans-Golgi network: identification of DKV582 as a recycling signal. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9331–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morotti A, et al. K252a inhibits the oncogenic properties of Met, the HGF receptor. Oncogene. 2002;21:4885–4893. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cockerill S, et al. Indazolylamino quinazolines and pyridopyrimidines as inhibitors of the EGFr and C-erb B-2. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;11:1401–1405. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang D, et al. Inhibition of MAPK kinase signaling pathways suppressed renal cell carcinoma growth and angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:81–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soulie P, et al. Membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase confers tumorigenicity on nonmalignant epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:1689–1697. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sounni NE, et al. Timp-2 binding with cellular MT1-MMP stimulates invasion-promoting MEK/ERK signaling in cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;126:1067–1078. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Alessia S, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 binding to membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase induces MAPK activation and cell growth by a non-proteolytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:87–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao J, et al. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase induces epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6232–6240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao J, et al. Distinct role for the catalytic and hemopexin domains of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in substrate degradation and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:14129–14139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golubkov VS, et al. Membrane Type-1 matrix metalloproteinase confers aneuploidy and tumorigenicity on mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10460–10465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golubkov VS, et al. Membrane Type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) exhibits an important intracellular cleavage function and causes chromosome instability. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25079–25086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golubkov VS, et al. Proteolysis-driven oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:147–150. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.2.3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley JMB, et al. Signaling pathways used in trabecular matrix metalloproteinase response to mechanical stretch. Invest. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:5174–5181. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berthier CC, et al. Sirolimus ameliorates the enhanced expression of metalloproteinases in a rat model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008;23:880–889. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad N, et al. The expression of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor correlates with Fuhrman grading of renal cell carcinomas. Human Pathol. 2004;35:1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritzsche FR, et al. ADAM9 is highly expressed in renal cell cancer and is associated with tumour progression. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:179–188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]