Abstract

Progress in genomics and proteomics attended to the door for better understanding the recent rapid expanding complex research field of metabolomics. This trend in biomedical research increasingly focuses to the development of patient-specific therapeutic approaches with higher efficiency and sustainability. Simultaneously undesired adverse reactions are avoided. In parallel, the development of molecules for molecular imaging is required not only for the imaging of morphological structures but also for the imaging of metabolic processes like the aberrant expression of the cysteine protease cathepsin B (CtsB) gene and the activity of the resulting product associated with metastasis and invasiveness of malign tumors. Finally the objective is to merge imaging and therapy at the same level. The design of molecules which fulfil these responsibilities is pivotal and requires proper chemical methodologies. In this context our modified solid phase peptide chemistry using temperature shifts during synthesis is considered as an appropriate technology. We generated highly variable conjugates which consist of molecules useful as diagnostically and therapeutically active molecules. As an example the modular PNA products with the complementary sequence to the CtsB mRNA and additionally with a cathepsin B cleavage site had been prepared as functional modules for distinction of cell lines with different CtsB gene expression. After ligation to the modular peptide-based BioShuttle carrier, which was utilized to facilitate the delivery of the functional modules into the cells' cytoplasm, the modules were scrutinized.

Keywords: Click Chemistry, Diels Alder Reactioninverse (DARinv), Fluorescence Imaging, Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA), PNA building block functionalization

Introduction

A search for the very first documentations of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) led to Miller's and Urey's experiments in the year 1953. They verified the hypothesis of the appearance of organic molecules under reducing atmospheric conditions 1. The PNA's role as a pivotal prebiotic molecule in the RNA world which acts as a template for the polymerization of the complementary nucleotide phosphoroimidazoles was postulated 2-6. The focus lies on Nielsen's successful pioneering work in the PNA syntheses 7. Contributions were made by the introduction of the Merriefield's solide phase peptide synthesis 8 and Carpino's protecting group methodologies 9. Additionally further parameters like the microwave-assistance 10, 11, the choice of the solvents 12, the manual and automated procedures as well as the selection of resins and linkers 13, 14 ameliorated the SPPS methodology concerning the yields, purity, and reaction times are comprehensively documented by Martinez 15.

All this enabled the use of PNAs useful in many ways, for instance as antisense molecules in pro- as well as in eukaryotic organisms 16, 17, and as triplex forming oligonucleotides (TFO) for antigenic strategies 18-20. From this point of view the use as therapeutic and diagnostic agents was documented 21. Further, PNAs have applications in analysis of biosensor chips for identification of nucleic acids 22. The structural and the physico-chemical properties of PNAs as well as the different synthesis methodologies are well documented 23-30. They reveal similarities to the native nucleic acids whose phospho-ribose backbone is substituted by a backbone of poly-2-aminoaethyl glycine with nucleobases connected via an acetate linker 31-34.

The use of PNA molecules is not restricted to its role as a DNA derivative. Derivatizations permit further functionalizations of the PNA polyamide backbone as demonstrated 35, 36. Finally the nucleobases were substituted with functional molecules as reaction partners for chemical reactions, for instance as a ligation partner in the “click-chemistry” 37-40. Manifold ligation reactions like the copper catalyzed alkine-azide cycloadditions introduced by Sharpless 41 are well reviewed by El-Sagheer and Brown 42. Here for instance, we used as ligation technology the Diels Alder Reaction with inverse electron demand (DARinv) introduced by Lindsay 43 and comprehensively investigated by Sauer 44 and Bertozzi 45, 46. The potential of the DARinv is well documented, undoubted and underlines multifaceted applications in the medical science. It is an attractive platform for active agents in therapy 47-50 as well as for imaging components in diagnostics 51, 52. The combination of different drugs and different diagnostic molecules in optimized ratios 52 allows the design of molecules ready to use for bi- tri- and multi-modal strategies. These can be considered as promising molecules in the personalized medicine and in the increasing field of theranostics 53. Our variant, a heat-assisted approach of the solid phase peptide synthesis is considered as an indispensable methodology which realizes a proper chemistry of PNA-based backbones functionalized multifold with a great potential to contribute to the diagnostics' precision and to the better therapy's success.

We tested the synthesized PNAs implemented into the drug delivery and targeting system called BioShuttle 54 as functional modules for hybridization in the cells with target sequences in the cathepsin B (CtsB) mRNA reacting in case of the existence of the activated CtsB enzyme in the cells 55. After enzymatic cleavage in the cytoplasm the fluorescent dye Rhod110 is transported and detectable in the cell nucleus.

Chemical Procedures & Results

PNA synthesis

For the PNA synthesis of the sequences (I) cagcgctgcag-C, (II) ctgcagcgctg-C, and (III) agcgctgagct-C (listed in the column D of Table 1) we used a manual synthesizer, PetiSyzer® from HiPep Laboratories, Kyoto, Japan. On this instrument we performed low cost simultaneous synthesis in disposable polypropylene reactors. An assembly of five disposable reactors is connected to a polytetrafluoroethylene tube (PTFE) manifold via PTFE two-way valves and are fixed on to a rack that can be shaken by a vortex-like mixer. The five reactors make contact with an aluminium block whose temperature is controlled by either an electric heater or cooled by the circulation of chilled liquid. In peptide synthesis it is known that elevated temperatures in the coupling reaction can overcome some coupling difficulties and shorten the coupling time. However it is also known that Fmoc-removal with piperidine at elevated temperatures results in racemization. Thus temperature control is required for such reactions. For the present PNA synthesis we intended to minimize aggregation and sterical hindrance by raising the temperature during the coupling time as it is known from peptide synthesis 56. We used 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chloride (Fmoc)-building blocks with blocked side chains of Adenine A, Cytosine C, and Guanine G by benzhydroxylcarbonyl (Bhoc) groups. The syntheses were performed in an 2 µmol scale on a H-Cys(Trt)-HMPB-ChemMatrix® resin loading 0.19 mmol/g. In the first step the Fmoc-group was cleaved with 20% piperidine in dimethylformamide (DMF) for 5 min at 20°C. After that, the resin was washed 5 times with DMF. For the coupling reaction the temperature was raised to 80°C and the coupling reaction was performed with 2-(1H-7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) for 40 min. After the coupling all free amino groups were capped with acetic acid anhydride in DMF and the resin was washed with DMF. Before the next Fmoc-deprotection step the reaction vessel was cooled to 20°C and the resin was treated with 20% piperidine in DMF. At the end of the PNA synthesis, the last step was a cleavage of the N-terminal protecting group with piperidine.

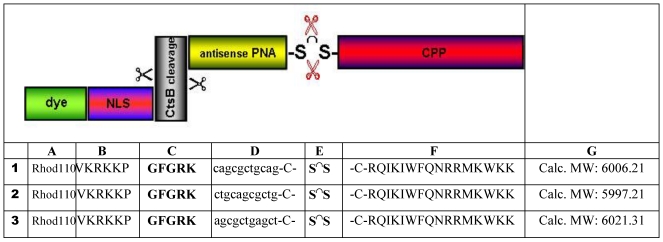

Table 1.

The schematic structure of the CtsB-BioShuttle (upper part) accentuates the modular construction which consists of the following functional units: CPP module (red) is responsible for the passage across cell membranes (the amino acid sequence is shown in the column F). The PNA module (yellow) harbours the sequences for the hybridization (column D, line 1 - antisense; line 2 - sense; line 3 - random) with the target-sequence inside of the CtsB mRNA's Exon I. After the enzymatic cleavage % (red) of the disulfide bridge (column E) inside of the cytosol, the CtsB cleavage module (column C, highlighted in grey) & covalently coupled to the NLS module (column B, red/blue) is cut. This in turn is connected to the Rhod110 (column A) fluorescent dye as a cargo (green) is illustrated. In the lines 1-3 the BioShuttle conjugates used for experiments are described.

A small sample of each PNA was cleaved with TFA (90%) and scavanger thriethylsilan/water (2.5%/2.5%) for 2.5 h at room temperature. The PNA was precipitated in ether and lyophilized. Analysis was carried out with HPLC and MS. By using different temperatures (20°C for Fmoc-protection (avoid racemization) and 80°C for the coupling reaction we could improve coupling efficiency compared to use of elevated temperature for the whole synthesis.

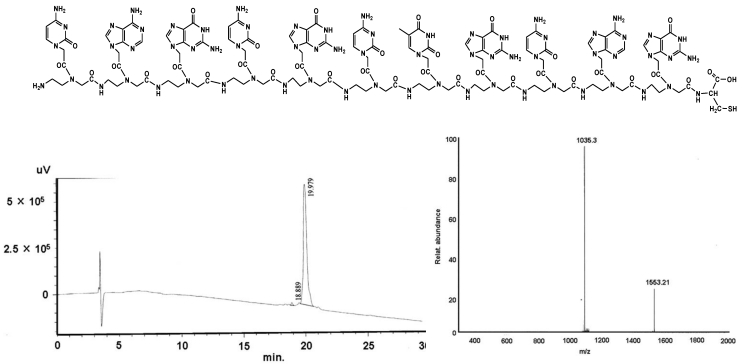

PNA I - cag cgc tgc ag-C

C120H151N67O34S:

Found mass: 3106.2; (M-2H)2+ 1553.21; (M+3H)3+ 1035.3

Exact mass: 3106.19 (Mol. Wt.: 3107.98);

m/e: 3107.19 (100.0%), 3108.19 (94.4%), 3106.19 (74.8%), 3109.19 (29.6%), 3109.20 (28.7%), 3107.18 (18.5%), 3110.20 (14.5%), 3110.19 (14.0%), 3111.20 (6.9%), 3108.18 (5.8%), 3111.19 (4.6%), 3109.18 (4.0%), 3112.20 (2.3%), 3108.20 (1.7%), 3110.18 (1.5%), 3112.19 (1.1%)

C, 46.37; H, 4.90; N, 30.19; O, 17.50; S, 1.03

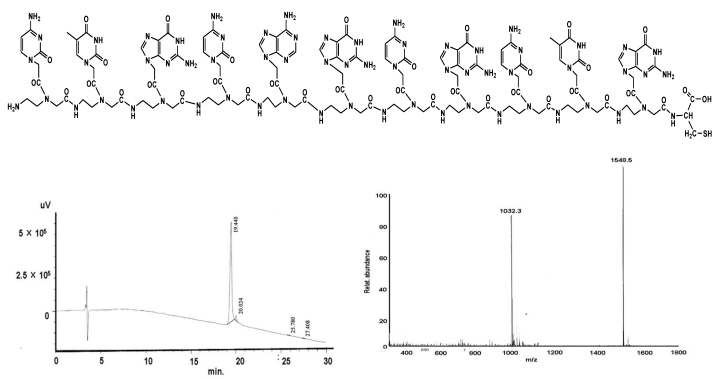

PNA II - ctg cag cgc tg-C

C120H152N64O36S:

Found mass: 3097.0; (M-2H)2+ 1548.5; (M+3H)3+ 1032.3

Exact mass: 3097.18; (Mol. Wt.: 3098.96)

m/e: 3098.18 (100.0%), 3099.18 (95.9%), 3097.18 (75.2%), 3100.19 (28.8%), 3100.18 (24.9%), 3098.17 (18.4%), 3101.19 (14.5%), 3101.18 (13.9%), 3100.17 (8.3%), 3102.19 (7.1%), 3099.17 (5.6%), 3102.18 (3.9%), 3103.19 (1.9%), 3101.17 (1.6%), 3103.18 (1.5%), 3102.17 (1.0%)

C, 46.51; H, 4.94; N, 28.93; O, 18.59; S, 1.03

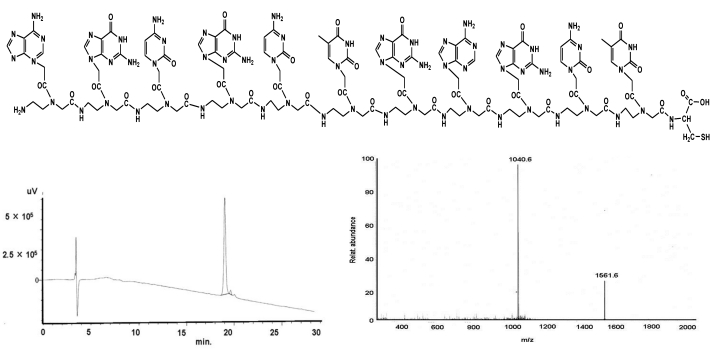

PNA III - agc gct gag ct-C

C121H152N66O35S;

Found mass: 3123.2; (M-2H)2+ 1561.6; (M+3H)3+ 1040.6

Exact mass: 3121.19; Mol. Wt.: 3122.99

m/e: 3122.19 (100.0%), 3123.19 (94.7%), 3121.19 (74.2%), 3124.19 (29.7%), 3124.20 (29.1%), 3122.18 (18.1%), 3125.20 (14.7%), 3125.19 (14.0%), 3126.20 (7.1%), 3123.18 (5.7%), 3126.19 (4.6%), 3124.18 (3.9%), 3127.20 (2.4%), 3123.20 (1.7%), 3125.18 (1.6%), 3127.19 (1.1%)

C, 46.54; H, 4.91; N, 29.60; O, 17.93; S, 1.03

Peptide synthesis

The peptides C-RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK [pAnt43-58], VKRKKP-GFGRK- cagcgctgcag-C, VKRKKP-GFGRK-ctgcagcgctg-C, and VKRKKP-GFGRK-agcgctgagct-C were synthesized in an automated multiple synthesizer Syro II (MultiSyn Tech, Germany) using Fmoc chemistry under atmospheric conditions at room temperature using the Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-HMPB-ChemMatrix® resin loading 0.50 mmol/g. For amino acid coupling a fivefold excess of the Fmoc-protected amino acid was activated in situ with 5 equivalents 2-(1H-Benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and DIPEA (0.5M) in DMF. The coupling time was 40 min. The Fmoc-group was cleaved with piperidine (20%) in DMF for 3 min and 10 min. After each step the resin was washed 5 times with DMF.

The Rhodamine 110 marker was inserted into the peptide by a manual coupling procedure. A threefold excess of this marker was activated in situ with 3 equivalents HATU and 2 equivalents DIPEA and added to the resin bound peptide for one hour reaction time. Afterwards the resin was washed three times with DMF, dichloromethane (DCM) and isopropanol and dried. The following cleavage of the peptide from the resin and of the side chain protecting groups was performed with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (90%) and as scavenger triethylsilan/water (2.5%/2.5%) for 2.5 h at room temperature was used.

Synthesis of the pAnt43-58 - cell penetrating peptide (CPP)

C107H174N35O21S2;

Found mass:2349.305;

Exact Mass: 2349.3; Mol. Wt.: 2235.77

m/e: 2350.30 (100.0%), 2351.31 (77.8%), 2353.31 (43.9%), 2354.31 (19.8%), 2355.26 (2.4%), 2356.31 (0.7%), 2357.31 (0.18%), C, 55.33; H, 7.53; N, 20.67; O, 13.60; S, 2.87

Found mass:

Exact mass: MW Cal: 6006.21 1501.37 (M+4H)4+; 1201.39 (M+5H)5+; 1001.28 (M+6H)6+

Purification of pAnt43-58 and Rhodamine-peptide-PNA conjugates

The crude material was purified by preparative HPLC on a Kromasil 100-10C 18 µm reverse phase column (30´ 250mm) using an eluent of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water (A) and 80% acetonitrile in water (B). The peptide was eluted with a successive linear gradient of 10% B to 80% B in 30 min at a flow rate of 23 ml/min. The fractions containing the purified protein were lyophilized. The purified material was characterized with analytical HPLC and matrix assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) (Figure 1 - 5).

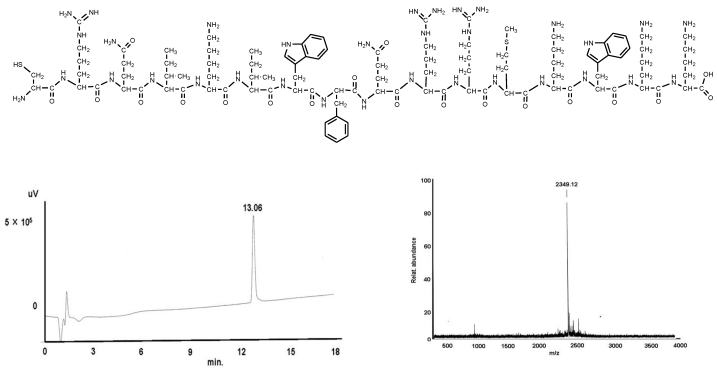

Figure 1.

shows the structural formula of the PNA I (upper part). The lower part demonstrates the graphs of HPLC (left) and mass (right).

Figure 2.

shows the structural formula of the PNA II (upper part). The lower part demonstrates the graphs of HPLC (left) and mass (right).

Figure 3.

shows the structural formula of the PNA III (upper part). The lower part demonstrates the graphs of HPLC (left) and mass (right).

Figure 4.

shows the structural formula of the pAnt43-58 (upper part). The lower part demonstrates the graphs of HPLC (left) and mass (right).

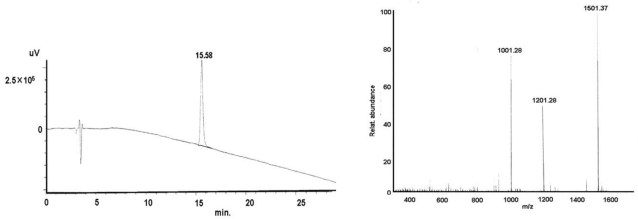

Figure 5.

shows exemplarily the HPLC and MS plots of the CtsB-BioShuttle construct 1 (shown in Table 1) containing the antisense PNA I after synthesis.

Ligation via disulfide bridge formation

The disulfide bridge between the N-terminal cysteine of pAnt43-58 and the N-terminal cysteine residue of the NLS was achieved by the activation of one cysteine using 2,2'-dithiopyridine and the subsequent coupling to the cysteine of the other module. The coupling reaction was carried out in an ethanol / water buffer at 60°C.

The individual components and the complete modules were validated using LCMS (Shimadzu LC-10 and LCQ electrospray, Finnigan-Mat, (Thermo Fischer Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The purity levels were generally >90%.

After ligation the reaction products were tested in the following cell study; the ultimate conjugates are listed Table 1.

Cell culture & CtsB-BioShuttle FFM-measurements

In order to characterize the CtsB-BioShuttle conjugates we used HeLa 57, 58 and MDA-MB-231 59, 60, human cell lines which are characterized by their different CtsB expression and activity of the gene product. CtsB considered as a genetic marker is strongly expressed during proteolysis' and apoptosis' processes 61-63. Therefore the CtsB mRNA was chosen as a target for a fluorescent imaging test of our CtsB-BioShuttle constructs.

In GenBank with the accession number M14221 the human cathepsin B mRNA sequence was searched. This sequence describes the total CtsB mRNA.

The bases sequences of the three investigated PNAs are represented as follows:

The PNA I is the corresponding antisense molecule and possesses the antiparallel complementary sequence of the CtsB mRNA Exon I at the position 70-80. As a control we synthesized the PNA II which is identical with the sequence of the CtsB mRNA at the end of the Exon I position 70-80 64. The PNA III's sequence is randomized.

The MDA-MB-231 cell line was cultivated in Dulbeco's modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% Glutamine (Biochrom, Germany). The HeLa cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal Calf serum. All cell lines were cultivated without phenol red and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 with high atmospheric humidity.

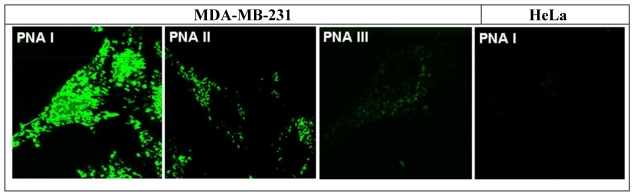

24 hours before fluorescence measurement studies the cells were washed in Hank's Balanced Salts (PAN-Biotech, Germany), after treatment with trypsin/EDTA solution (0.5/0.2 %) harvested and suspended in fresh medium. Cell suspension (400 µl) were transferred to chambers of the Lab-Tek™ Chamber Slides (Nunc, USA) and incubated under identical conditions as described above. For measurement studies the MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the CtsB-BioShuttle conjugates PNA I, PNA II, and PNA III (final concentration 100 nM) for 1 h. Finally, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with Hank's and fresh medium was added. The HeLa cells were treated identically with the CtsB-BioShuttle PNA I variant (as a negative control). After 24 hours, the samples were measured as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The figure shows FFM-measurement pictures the of the cell lines: MDA-MB-231 cells 24 hours after treatment (final concentration 100 nM) with the CtsB-BioShuttle conjugates PNA I, PNA II and PNA III, and HeLa control cells (right picture) treated with the PNA I (antisense). The fluorescence signals can be observed inside of both lines and indicate an uptake of all tested CtsB-BioShuttle conjugates. Whereas the fluorescence signal intensity inside of the cytoplasm of the MDA-MB-231 cells treated with PNA III (random) is hardly visible related to the signal intensities inside of the cytosol of MDA-MB-231 cells which are treated with PNA I and PNA II. Solely in the nuclei of the MDA-MB-231 cells treated with the PNA I clear morphologic structures with high fluorescence intensities are recognizable. The HeLa control cells treated with the PNA I (antisense) did not show fluorescence signals.

Discussion and outlook

Progresses in both, the genome - and in the informatics research established proteomics and metabolomics and influenced the pharmaceutical research in diagnostic as well as in therapeutic areas 65-70. “Old fashioned” diagnostic molecules and drugs are highly effective but not sensitive enough, hamper the therapeutic success and result in discontinuation of treatment. It is beyond controversy that these drugs, which represent the old paradigm “one size fits all”, is not really up-to-date anymore 71, 72.

The Blockbusters' importance seems to approach perpetually its end, in parallel, the time for individual therapeutic interventions started 73, 74. The situation changed and the new paradigm delineates the “patient specific medicine” 75. This “personalized medicine” is based on the generation and application of the patient-specific drug 76, 77. The development of such components is deemed to be a global challenge for “Big Pharma”. In consideration of quality and specificity the biotech industry seems to have advances in providing breakthrough products more efficiently than pharmaceutical industrial manufacturing 78. The recombinant chemistry together with the solid phase peptide synthesis chemistry (SPPS) represent two methodologies to fulfil the demands of crucial criteria (high quality & high variability) for biotechnology products 79 and the synthesis of molecules designed for the patient's genetic disposition.

Here we discuss a SPPS variant featuring these properties which is based on the classical solid phase strategy but focuses on the temperature as physical parameter. However, folding processes after peptide syntheses can hamper the prolongation of the peptide bond formation during the solid phase synthesis.

Microwave heat assisted syntheses, however at elevated reaction temperature resulted in increased racemization 80, 81. We circumvented this drawback using a concept based on a personal synthesizer, used for peptide synthesis and also for organic chemical syntheses that involves heating, cooling and filtration procedures 82. A microwave methodology providing synthesis conditions avoiding racemization is still under investigation by the Nokihara group, HiPep Laboratories, Kyoto (unpublished data).

The temperature is assumed to be the critical parameter in limiting the peptide synthesis as documented in 1988 by Merrifield 83. A heat-induced unfolding of peptide chains can be understood as an initial point for the successful construction of large proteins, shown by the Dolphin group 56. Here we studied this methodology in the solid phase synthesis of peptide nucleic acids as an initial step for the entry into “personalized medicine” in oncology using exemplarily the cathepsin B gene (CtsB) and the corresponding mRNA as molecular target. The SPPS, the attachment of a fluorescence dye and the following ligation of the modules by disulfide formation result in the final CtsB-BioShuttle conjugate designed for fluorescence imaging in the selected cell lines. HeLa cells were used as a control and the imaging of the CtsB mRNA was documented 55. Here we confirmed the data of the non-invasive HeLa cervix carcinoma and the invasive MDA-MB-231 the breast cancer cell lines differentially expressing the CtsB (Figure 6). The CtsB-BioShuttle on MDA-MB-231 resulted in strong signal using the construct with the complementary PNA I. This would be the direct way to detect tumor cells and treat with patient specific PNA at the same time. Insistently, the complexity of the pharmaceutical research and in biotechnology, the dedicated chemical methodologies like the SPPS hold a key role in the development of patient-specific drugs and imaging agents.

References

- 1.Miller SL. A Production of Amino Acids Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions. Science. 1953;117:528–9. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3046.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SL. Peptide nucleic acids and prebiotic chemistry. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:167–9. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohler C, Nielsen PE, Orgel LE. Template switching between PNA and RNA oligonucleotides. Nature. 1995;376:578–81. doi: 10.1038/376578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen PE. Peptide nucleic acids and the origin of life. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1996–2002. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson KE, Levy M, Miller SL. Peptide nucleic acids rather than RNA may have been the first genetic molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3868–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prebiotic. Miller SL; http://exobio.ucsd.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Berg RH. et al. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merriefield RB. Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. I The Synthesis of a Tetrapeptide. J Americ Chem Soc. 1963;85:2149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpino LA, Han GY. The 9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl Amino-Protecting Group. J ORG CHEM. 1972;37:3404–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galanis AS, Albericio F, Grotli M. Solid-phase peptide synthesis in water using microwave-assisted heating. Org Lett. 2009;11:4488–91. doi: 10.1021/ol901893p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen SL, Sorensen KK, Jensen KJ. Semi-automated microwave-assisted SPPS: Optimization of protocols and synthesis of difficult sequences. Biopolymers. 2010;94:206–12. doi: 10.1002/bip.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hojo K, Maeda M, Tanakamaru N. et al. Solid phase peptide synthesis in water VI: evaluation of water-soluble coupling reagents for solid phase peptide synthesis in aqueous media. Protein Pept Lett. 2006;13:189–92. doi: 10.2174/092986606775101607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabatino G, Papini AM. Advances in automatic, manual and microwave-assisted solid-phase peptide synthesis. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2008;11:762–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss JA. Guide for resin and linker selection in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2005. Chapter 18: Unit 18.7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Amblard M, Fehrentz JA, Martinez J. et al. Fundamentals of modern peptide synthesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;298:3–24. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-877-3:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good L, Nielsen PE. Antisense inhibition of gene expression in bacteria by PNA targeted to mRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:355–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ecker DJ, Freier SM. PNA, antisense, and antimicrobials. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:332. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank Kamenetskii MD, Mirkin SM. Triplex DNA structures. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen PE. Targeting double stranded DNA with peptide nucleic acid (PNA) Curr Medicinal Chem. 2001;8:545–50. doi: 10.2174/0929867003373373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey BP, Glazer PM. Gene targeting via triple-helix formation. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;67:163–92. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)67028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal S, Iyer RP. Modified oligonucleotides as therapeutic and diagnostic agents. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:12–9. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arlinghaus HF, Kwoka MN, Jacobson KB. Analysis of biosensor chips for identification of nucleic acids. Anal Chem. 1997;69:3747–53. doi: 10.1021/ac970267p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leijon M, Graslund A, Nielsen PE. et al. Structural characterization of PNA-DNA duplexes by NMR. Evidence for DNA in a B-like conformation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9820–5. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksson M. Structure of PNA-Nucleic Acid Complexes. Nucleos Nucleot. 1997;16:617–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demidov VV, Potaman VN, Frank Kamenetskii MD. et al. Stability of peptide nucleic acids in human serum and cellular extracts. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:1310–3. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen PE, Christensen L. Strand Displacement Binding of a Duplex-Forming Homopurine PNA to a Homopyrimidine Duplex DNA Target. J AMER CHEM SOC. 1996;118:2287–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson M, Nielsen PE. PNA-nucleic acid complexes. Structure, stability and dynamics. Q Rev Biophys. 1996;29:369–94. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen PE. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA) in chemical biology and drug discovery. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7:786–804. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dueholm KL, Egholm M, Behrens C. et al. Synthesis of Peptide Nucleic Acid Monomers Containing the Four Natural Nucleobases: Thymine, Cytosine, Adenine, and Guanine and their Oligomerization. J ORG CHEM. 1994;59:5767–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fader LD, Myers EL, Tsantrizos YS. Synthesis of novel analogs of aromatic peptide nucleic acids (APNAs) with modified conformational and electrostatic properties. TETRAHEDRON. 2004;60:2235–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Nielsen PE. et al. Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA). Oligonucleotide Analogues with an Achiral Peptide Backbone. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1895–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchardt O, Egholm M, Berg RH. et al. Peptide nucleic acids and their potential applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1993;11:384–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(93)90097-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen PE, Haaima G. Peptide Nucleic-Acid (PNA) - A DNA Mimic with a Pseudopeptide Backbone. CHEM SOC REV. 1997;26:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dueholm KL, Nielsen PE. Chemistry, Properties and Applications of PNA (Peptide Nucleic- Acid) NEW J CHEM. 1997;21:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jordan S, Schwemler C, Kosch W. et al. Synthesis of New Building-Blocks for Peptide Nucleic-Acids Containing Monomers with Variations in the Backbone. Bioorg Medicinal Chem Letter. 1997;7:681–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu J, Xu XY, Liu KL. Synthesis of new chiral building blocks for novel peptide nucleic acids. Chinese Journal of Chemistry. 2003;21:566–73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiessler M, Waldeck W, Pipkorn R. et al. Extension of the PNA world by functionalized PNA monomers eligible candidates for inverse Diels Alder Click Chemistry. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:213–23. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiessler M, Waldeck W, Kliem C. et al. The Diels-Alder-reaction with inverse-electron-demand, a very efficient versatile click-reaction concept for proper ligation of variable molecular partners. Int J Med Sci. 2009;7:19–28. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun K, Ehemann V, Wiessler M. et al. High-Resolution Flow Cytometry: a Suitable Tool for Monitoring Aneuploid Prostate Cancer Cells after TMZ and TMZ-BioShuttle Treatment. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:338–47. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:1128–37. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV. et al. A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective "ligation" of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:2596–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Sagheer AH, Brown T. Click chemistry with DNA. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1388–405. doi: 10.1039/b901971p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carboni RA, Lindsey RV. Reactions of Tetrazines with Unsaturated Compounds - A New Synthesis of Pyridazines. J Americ Chem So. 1959;81:4342–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauer J, Wiest H. Diels-Alder-Additionen Mit Inversem Elektronenbedarf. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 1962;74:353. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin FL, Hoyt HM, van HH. et al. Mechanistic investigation of the staudinger ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2686–95. doi: 10.1021/ja044461m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang PV, Prescher JA, Sletten EM. et al. Copper-free click chemistry in living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911116107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braun K, Wiessler M, Ehemann V. et al. Treatment of glioblastoma multiforme cells with temozolomide-BioShuttle ligated by the inverse Diels-Alder ligation chemistry. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2008;2:289–301. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waldeck W, Wiessler M, Ehemann V. et al. TMZ-BioShuttle--a reformulated temozolomide. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5:273–84. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pipkorn R, Waldeck W, Didinger B. et al. BioShuttle as a carrier for temozolomide transport into prostate cancer cells. Journal of Peptide Science. 2008;14:156. doi: 10.1002/psc.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pipkorn R, Wiessler M, Waldeck W. et al. Tmz-Bioshuttle, An Exemplary Drug Reformulation by Inverse Diels Alder Click Chemistry. Biopolymers. 2009;92:350–1. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braun K, Dunsch L, Pipkorn R. et al. Gain of a 500-fold sensitivity on an intravital MR contrast agent based on an endohedral gadolinium-cluster-fullerene-conjugate: a new chance in cancer diagnostics. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:136–46. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Braun K, Wiessler M, Pipkorn R. et al. A cyclic-RGD-BioShuttle functionalized with TMZ by DARinv "Click Chemistry" targeted to alphavbeta3 integrin for therapy. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:326–39. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warner S. Diagnostics + Therapy = Theranostics. The Scientist. 2004;18:38. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braun K, Peschke P, Pipkorn R. et al. A biological transporter for the delivery of peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) to the nuclear compartment of living cells. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:237–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pipkorn R, Waldeck W, Spring H. et al. Delivery of substances and their target-specific topical activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:606–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolphin GT. A designed well-folded monomeric four-helix bundle protein prepared by Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis and native chemical ligation. Chemistry. 2006;12:1436–47. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macville M, Schrock E, Padilla-Nash H. et al. Comprehensive and definitive molecular cytogenetic characterization of HeLa cells by spectral karyotyping. Cancer Res. 1999;59:141–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker CC, Phelps WC, Lindgren V. et al. Structural and transcriptional analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:962–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.962-971.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cailleau R, Young R, Olive M. et al. Breast tumor cell lines from pleural effusions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:661–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young RK, Cailleau RM, Mackay B. et al. Establishment of epithelial cell line MDA-MB-157 from metastatic pleural effusion of human breast carcinoma. In Vitro. 1974;9:239–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02616069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baici A, Lang A, Horler D. et al. Cathepsin B as a marker of the dedifferentiated chondrocyte phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:684–91. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.8.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foghsgaard L, Wissing D, Mauch D. et al. Cathepsin B acts as a dominant execution protease in tumor cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:999–1010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohanam S, Jasti SL, Kondraganti SR. et al. Down-regulation of cathepsin B expression impairs the invasive and tumorigenic potential of human glioblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:3665–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zwicky R, Muntener K, Goldring MB. et al. Cathepsin B expression and down-regulation by gene silencing and antisense DNA in human chondrocytes. Biochem J. 2002;367:209–17. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drews J, Ryser S. The role of innovation in drug development. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1318–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Werner RG. Biobusiness in the pharmaceutical industry. Arzneimittelforschung. 1987;37:1086–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farber GK. New approaches to rational drug design. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;84:327–32. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roth CM, Yarmush ML. Nucleic acid biotechnolqgy. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:265–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hogemann D, Basilion JP. "Seeing inside the body": MR imaging of gene expression. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:400–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0765-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Okubo K, Matsumoto K, Ssito H. ["Omics" study of diseases] Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2011;114:51–9. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.114.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farooqi AA, Bhatti S, Nawaz A. et al. One size fits all in prostate cancer: a story tale whose time has come and gone. Int J Biol Markers. 2011;26:75–81. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2011.8368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swain SM. Chemotherapy: updates and new perspectives. Oncologist. 2011;16(Suppl 1):30–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garnier JP. Rebuilding the R&D engine in big pharma. Harv Bus Rev. 2008;86:68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Badcott D. Some causal limitations of pharmacogenetic concepts. Med Health Care Philos. 2006;9:307–16. doi: 10.1007/s11019-006-9008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diamandis M, White NM, Yousef GM. Personalized medicine: marking a new epoch in cancer patient management. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1175–87. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gibson WM. Can personalized medicine survive? Can Fam Physician. 1971;17:29–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kawamoto K, Lobach DF, Willard HF. et al. A national clinical decision support infrastructure to enable the widespread and consistent practice of genomic and personalized medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lavis J, Ross S, McLeod C. et al. Measuring the impact of health research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:165–70. doi: 10.1258/135581903322029520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rathore AS. Roadmap for implementation of quality by design (QbD) for biotechnology products. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palasek SA, Cox ZJ, Collins JM. Limiting racemization and aspartimide formation in microwave-enhanced Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:143–8. doi: 10.1002/psc.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bacsa B, Horvati K, Bosze S. et al. Solid-phase synthesis of difficult peptide sequences at elevated temperatures: a critical comparison of microwave and conventional heating technologies. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7532–42. doi: 10.1021/jo8013897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nokihara K, Yamamoto S, Toda C, Wang J. Development of a simple and low cost manual synthsizer for chemical library construction. In: Aoyagi H, editor. Peptide Science. Japan: The Japanese Peptide Society; 2001. pp. 61–4. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tam JP, Riemen MW, Merrifield RB. Mechanisms of aspartimide formation: the effects of protecting groups, acid, base, temperature and time. Pept Res. 1988;1:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]