Abstract

The binding stoichiometry between Cu(II) and the full-length β-amyloid Aβ(1–42) and the oxidation state of copper in the resultant complex were determined by electrospray ionization-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI-FTICR-MS) and cyclic voltammetry. The same approach was extended to the copper complexes of Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–28). A stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 was directly observed and the oxidation state of copper was deduced to be 2+ for all the complexes and residues tyrosine-10 and methionine-35 are not oxidized in the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex. The stoichiometric ratio remains the same in the presence of more than 10 fold excess of Cu(II). Redox potentials of the sole tyrosine residue and the Cu(II) center were determined to be ca. 0.75 V and 0.08 V vs. Ag/AgCl (or 0.95 V and 0.28 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)), respectively. More importantly, for the first time, Aβ-Cu(I) complex has been generated electrochemically and was found to catalyze the reduction of oxygen to produce hydrogen peroxide. The voltammetric behaviors of the three Aβ segments suggest that diffusion of oxygen to the metal center can be affected by the length and hydrophobicity of the Aβ peptide. The determination and assignment of the redox potentials clarify some misconceptions in the redox reactions involving Aβ and provide new insight into the possible roles of redox metal ions in the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. In cellular environments, the reduction potential of the Aβ-Cu(II) complex is sufficiently low to react with antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid) and cellular redox buffers (e.g., glutathione), and the Aβ-Cu(I) complex produced could subsequently reduce oxygen to form hydrogen peroxide via a catalytic cycle. Using voltammetry, the Aβ-Cu(II) complex formed in solution was found to be readily reduced by ascorbic acid. Hydrogen peroxide produced, in addition to its role in damaging DNA, protein, and lipid molecules, can also be involved in the further consumption of antioxidants, causing their depletion in neurons and eventually damaging the neuronal defense system. Another possibility is that Aβ-Cu(II) could react with species involved in the cascade of electron transfer events of mitochondria and might potentially side-track the electron transfer processes in the respiratory chain, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder underscored by the appearance of senile plaques in disease-inflicted brains. The major components in senile plaques are peptides containing 39–43 amino acid residues (amyloid-β or Aβ peptides) generated from proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases (1, 2). Such findings(2, 3) led to the hypothesis that deposition of Aβ fibrils and other aggregates is responsible for neuronal cell loss (4). However, how β-amyloid associates with the AD pathogenesis remains unclear.

Other characteristics in AD-affected brains include the enhanced level of oxidative stress manifested by extensive oxidation of proteins (5–7) and DNA (8–10), unusually high levels of metals (e.g., copper, zinc and iron) present in the senile plaques, and a decline of polyunsaturated fatty acids (11, 12) coupled with increased lipid peroxidation (13–15). On the basis of the amyloid hypothesis and the existence of oxidative stress, Butterfield and coworkers (15) proposed a model to account for neurodegeneration in AD, viz., β-amyloid peptide-initiated oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. The aggregated amyloid peptide, perhaps in concert with complexed redox metal ions, produces free radicals and triggers a cascade of events, which include, but are not limited to, protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and cellular dysfunction. All of these detrimental processes result in death of neurons (15).

Together with these pathological characteristics, intracellular lesions, including impairment of mitochondrial energy metabolism, have also been purported to be a cause of the AD development (9, 10, 16, 17). In addition, impaired energy metabolism and altered cytochrome c oxidase activity are among the earliest detectable defects in AD (18–21). Recently, the linkage between mitochondrial dysfunction and Aβ peptides has been suggested by Deshpande et al. (22) who showed that, after treatment of neuronal cells with Aβ oligomers, mitochondrial redox potential dropped precipitously. A marked decease in ATP level and drastic increases in caspase activation and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release were also observed prior to the occurrence of massive cell death (22). It also has been reported that synthetic Aβ inhibited activity of the human cytochrome c oxidase and the inhibitory effect is dependent on the copper content (23, 24). Only in the presence of copper does Aβ significantly inhibit the activity of human cytochrome c oxidase in mitochondria. These results suggest that copper plays a significant role in the neurotoxicity of Aβ.

The brain utilizes metal ions for many biochemical reactions, and cortical neurons release exchangeable copper and zinc ions during depolarization and neurotransmission (25, 26). Whether metal ions are involved in the pathogenesis of AD and what roles they play in the evolvement of oxidative stress and AD development are not known. Yet, the fact that senile plaques in the neocortical region of the brains of AD patients contain up to millimolar concentrations of Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe3+ (27) suggests that metal ions probably play a pivotal role in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A recent study by Raman spectroscopy of senile plaques extracted from postmortem samples demonstrated that copper and zinc ions are bound via histidine imidazole rings (28). More importantly, it was found that extensive methionine oxidation in Aβ has occurred in intact plaques (28). For metals to exert important influences on the AD pathogenesis, it is likely that a series of redox reactions facilitated by the metal-containing Aβ species have occurred, leading to the production of ROS and/or the interruption of electron transfer (ET) chain in the respiratory processes. Along this line, Cu(II) coordination with Aβ has been extensively investigated (29–34). In support of the important role of copper-containing Aβ species in ROS production, studies have shown that in vitro incubation of an Aβ/Cu(II) mixture with electron donors under aerobic condition produced hydrogen peroxide (35–37).

A number of techniques have been employed for examining the various aspects of the interactions between β-amyloid and copper ions (e.g. the structure of and binding sites in the complex) (34, 35, 38, 39). Although conflicting results have been reported on certain aspects (for example, the metal binding stoichiometry and affinity) (29, 34, 38, 39), it is generally accepted that metal ions are bound to the hydrophilic portion of Aβ species (residues 1–16). Moreover, the involvement of histidine residues at positions 6, 13, and 14 has been ascertained by many studies (30, 34, 38). Given the wide existence of ET processes in cells in general and neuronal cells in particular, the introduction of exogenous redox-active species may alter the ET reactions or pathways in mitochondria. The accurate determination of redox potentials of Aβ and its metal complexes will certainly help unravel their roles in oxidative stress, metal homeostasis and detoxification, and Aβ aggregation/fibrillation. Surprisingly, other than a single experiment comparing the voltammetric behaviors of Aβ(1–42) and its copper complex (35), a systematic effort has not been made to measure accurately the redox potentials of metal complexes of the full-length and different segments of Aβ and to relate them to redox reactions in cellular milieu. Moreover, there exist inconsistencies in the interpretations of the redox reactions of the Aβ-metal complexes (e.g., whether Cu(II) can be reduced by Aβ and, if the reduction does occur, which constituents in Aβ cause the reduction) (27, 35, 37, 40). Compounded by the complexity in Aβ structural elucidation and the possible involvement of Aβ in many cellular processes, evidence regarding the effect of redox-active metal ions on ROS generation and the possible oxidations of the methionine residue near the C terminus (Met-35) and the tyrosine moiety in the hydrophilic domain (Tyr-10) remain either indirect or largely elusive.

Electrochemical methods can allow for the accurate and direct determination of potentials of redox-active biomolecules and provide insight about their ET reactions (41). By judiciously choosing the electrode materials and electrolyte system, one can achieve facile ET rates at the electrode/solution interface and reliably determine the redox potentials. In this study, we employed cyclic voltammetry (CV) and mass spectrometry (MS), to investigate the redox properties of several Aβ variants and their copper complexes. We present strong evidence about the inability of Aβ, in the absence of a cofactor (i.e., a reductant), to reduce Cu(II) and report on an experiment in which electrogenerated Aβ-Cu(I) complex can indeed facilitate the catalytic reduction of dissolved oxygen to hydrogen peroxide. Based on the redox potential of Aβ-Cu(II) and comparing it to those of selected cellular reductants, the implications of the Aβ involvement in the production of ROS and the ET chain of mitochondria and their relations with AD pathogenesis are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lyophilized Aβ(1–16), Aβ(1–28), and Aβ(1–42) (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK16LVFFAEDVGSNK28GAIIGLMVGGVVIA42) samples were purchased from American Peptide Co. Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Aβ(1–28) and Aβ(1–42) samples, generously provided by Prof. C. Glabe (University of California at Irvine, CA), were also used in this study. No difference in terms of experimental results between the two sources of Aβ samples was found. Other chemicals were of analytical grade (Sigma-Aldrich). All the aqueous solutions were prepared using Millipore water (18 MΩ cm). Throughout the work, 1 mM CuCl2 dissolved in 1 mM H2SO4 was used as the Cu(II) stock solution. Aβ(1–16) were prepared freshly by dissolving lyophilized powder samples in Millipore water or 5 mM NaOH. No apparent difference was observed for electrochemistry and MS results between samples dissolved in water and those dissolved in NaOH. To ensure no substantial aggregation occurs and to rid the solution of any aggregates, Aβ (1–28) and Aβ (1–42;) samples were routinely prepared using a similar protocol developed by Teplow and coworkers (42) and Zorgowski and coworkers (43). Briefly, Aβ stock solutions (0.5 mM) were prepared daily by dissolving the lyophilized Aβ in 5 mM NaOH. This was followed by sonication for 1 min. The as-prepared solutions were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min and the supernatants were pipetted out for further dilutions. During the relatively short voltammetric and MS measurements, Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–28) were not found by atomic force microscopy to aggregate considerably, whereas small amounts of oligomers of Aβ(1–42) were observed. By decreasing the Aβ(1–28) concentration and adding 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) into the Aβ(1–42) solution, aggregation in both cases was avoided or significantly retarded.

Electrochemical measurements

All the electrochemical experiments were performed on a CHI 832 electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, Austin, Texas) using a home-made plastic electrochemical cell. A glassy carbon disk electrode and a platinum wire were used as the working and counter electrodes, respectively. The reference electrode was Ag/AgCl and all the potential values are reported with respect to this electrode unless otherwise stated. Prior to each experiment, the glassy carbon electrode was polished with diamond pastes of 15 and 3 µm and alumina pastes of 1 and 0.3 µm in diameter (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL). The electrolyte solution was a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH, 7.4) containing 0.1 M Na2SO4. Although it has been noted that different buffer solutions may affect Aβ/Cu(II) binding and the subsequent H2O2 generation, we did not test other buffers because H2O2 had been detected in phosphate buffer containing Aβ and Cu(II).(37) Thus, the voltammetric studies in such an electrolyte solution are more relevant to the elucidation of the redox reactions of Aβ-Cu(II) and H2O2 generation. For Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–28), aliquots of Aβ from stock solutions were diluted with the phosphate buffer to desired concentrations. For voltammetric studies in the presence of Cu(II), these Aβ solutions were spiked with the Cu(II) stock solution to different Aβ/Cu(II) molar ratios. For voltammetric studies of Aβ(1–42), the same procedures were employed except that the 10 mM phosphate/0.1 M Na2SO4 (pH 7.4) solution containing 10% dimethylsulfoxide was chosen to retard the rapid aggregation of Aβ(1–42).

Detection of hydrogen peroxide

Based on the voltammetric data (cf. Results Section), the electrode potential was held at 0.07 V to reduce the Aβ/Cu(II) complex. Possible H2O2 generation was monitored using the Fluoro H2O2 detection kit (Cell Technology Inc., Mountain View, CA). In the presence of H2O2, 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (ADHP) is oxidized to a fluorescent product, resorufin. This reaction is rapidly catalyzed by peroxidase in a homogeneous solution. Briefly, 50 µL of the sample solution was added to 50 µL aliquot of the reaction cocktail, which contained 100 µL of 10 mM ADHP, 200 µL of 10 U/mL horseradish peroxidase, and 4.7 mL of reaction buffer. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature in dark for 10 min. Subsequently the fluorescence intensity of resorufin was measured at an excitation wavelength of 550 nm with a Cary Eclipse Spectrofluorometer (Varian, Inc, Palo Alto, CA). By comparing the fluorescence intensity of resorufin of the sample solution to that of the control, H2O2 can be detected.

Electrospray ionization-Fourier transform ion cyclotron mass spectrometry (ESI-FTICR-MS)

The ESI-FTICR-MS experiments were conducted on an IonSpec FT-ICR mass spectrometer equipped with a 4.7-Tesla superconducting magnet (IonSpec Inc., Lake Forest, CA) and an LTQ linear-ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) operated in the high-resolution, “ultra zoom scan” mode. For the MS measurements, Aβ was first dissolved in a water/methanol solution (50/50 volume ratio) to yield a 50-µM Aβ stock solution. Aliquots were then diluted with the water/methanol solution to a final concentration of 5 µM. The Aβ solution and Aβ solution spiked with CuCl2 at different molar ratios were introduced to and analyzed by MS. The typical mass resolving power for the FTICR-MS is approximately 200,000.

RESULTS

Copper binds Aβ at 1:1 molar ratio and the oxidation state of copper is +2

The coordination chemistry between Cu(II) and Aβ has been investigated by various techniques, such as circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (34, 35), electron spin resonance (ESR) (34, 35, 38) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (34, 39). While all the studies indicate that Cu(II) can be incorporated mainly in the hydrophilic domain (residues 1 through 16), contradictory results have been reported regarding the coordination stoichiometry, the ligands involved, and the oxidation state of copper. A few papers suggested that Aβ-Cu(II) binding ratio is 1:2 (29, 34), whereas other papers showed that the ratio should be 1:1 (38, 39). MS can provide evidence for the number of copper ions bound per Aβ molecule. ESI-MS is particularly advantageous in that the soft ionization by ESI generates multiply charged species of proteins or peptides while keeping the molecular ions intact. Formation of multiply charged species also decreases the mass-to-charge ratios, shifting molecular ions of large biomolecules to the mass range readily accessible by most mass analyzers (44). Furthermore, when the MS employed has a high resolving power, the analysis of isotopic peaks affords an opportunity to deduce the oxidation state of the ligated metal ion. To our knowledge, the use of ESI coupled with high-resolution MS to study Aβ-metal ion binding has not been reported.

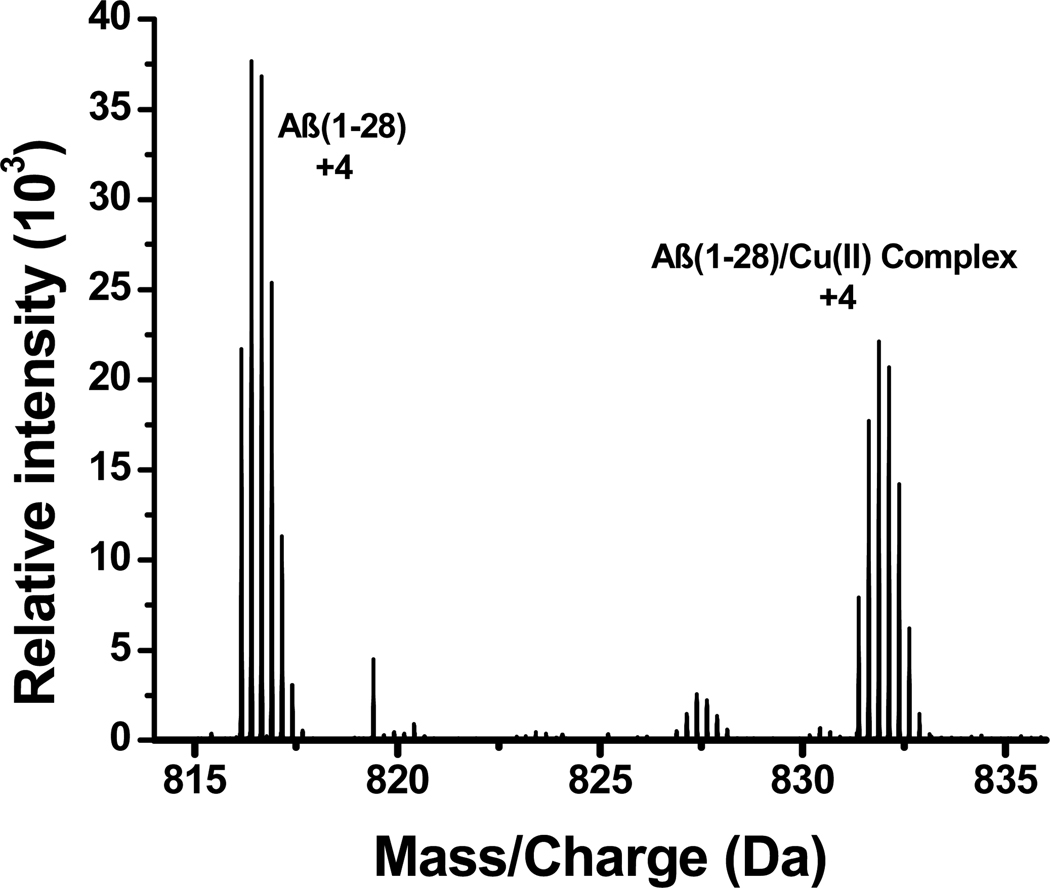

The predominate peaks in the ESI-FTICR mass spectra indicate that Aβ and its copper complex are of the 3+, 4+, and 5+ charge states, with the 4+ charge state being the most abundant. Figure 1 shows the m/z range covering the peaks corresponding to the 4+ charge states of free Aβ(1–28) and its copper complex. Clustered around m/z 816 and m/z 832 are the various isotopic peaks of the quadruply charged Aβ(1–28) and Aβ(1–28)-copper ion complex, respectively. An ESI-FTICR mass spectrum of Aβ(1–28) in the absence of Cu2+ exhibited peaks at around m/z 816 (See Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). The difference in the mass between the monoisotopic peaks of free Aβ(1–28) and Aβ (1–28)-Cu complex is 4×(831.387–816.142)=60.980 Da. Since the monoisotopic Aβ (1–28)-Cu(II) complex has two less protons, the actual mass difference is 60.980 +2 = 62.980, which is close to the nominal mass of a copper ion. Therefore, the ESI-MS result supports that the binding stoichiometry between Aβ(1–28) and Cu is 1:1. Further increasing the molar ratio between Cu(II) and Aβ(1–28) (up to 10) in the solution only changed the relative intensities of the free Aβ(1–28) and Aβ(1–28)-Cu(II) peaks, but did not create other peaks of different binding stoichiometries (e.g., 1:2 or 2:1).

Figure 1.

Positive-ion ESI-MS of an Aβ(1–28)/Cu(II) mixture at 1:1 ratio.

The oxidation number of the copper ion in the complex can be determined from the measured m/z values of the 4+ ion of the complex. In this respect, if Cu(I) is involved in the formation of the complex, the complex will need to be associated with three protons to yield a 4+ ion; on the other hand, if Cu(II) is present in the complex, it would only require two protons to give a quadruply charged ion. The oxidation number of copper ion present in the complex can, therefore, be determined by comparing the experimentally measured m/z values of the isotope clusters for the quadruply charged complex with the calculated m/z values for the complexes that are associated with either Cu(I) or Cu(II) (see Table 1). Clearly, the deviations between the measured and calculated m/z values for the Cu(II)-complex are 15–23 ppm, which are markedly smaller than the 280–290 ppm deviations found for the differences between the measured and calculated m/z values for the Cu(I)-complex. These results, therefore, strongly support that the charge state of copper ion in the Aβ(1–28)-copper complex is 2+. Similar analysis of the isotope cluster peaks for the 3+ ion leads to the same conclusion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Extracting the copper oxidation state from mass peaks of the Aβ (1–28)-Cu(II) adduct

|

Aβ(1–28)-Cu |

Aβ-Cu(I) | Aβ-Cu(II) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meas. m/z | Meas. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Calcd. m/z |

Calcd. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Dev. (ppm) |

Calcd. m/z |

Calcd. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Dev. (ppm) |

||

| 3+ Ion | A | 1108.145 | 15 | 1108.491 | 48 | 310 | 1108.155 | 48 | 9 |

| A+1 | 1108.475 | 77 | 1108.825 | 85 | 320 | 1108.489 | 85 | 13 | |

| A+2 | 1108.806 | 100 | 1109.159 | 100 | 320 | 1108.823 | 100 | 15 | |

| A+3 | 1109.139 | 75 | 1109.493 | 88 | 320 | 1109.157 | 88 | 16 | |

| A+4 | 1109.470 | 30 | 1109.827 | 61 | 320 | 1109.491 | 61 | 19 | |

| 4+ Ion | A | 831.387 | 36 | 831.620 | 48 | 280 | 831.368 | 48 | 23 |

| A+1 | 831.634 | 80 | 831.871 | 85 | 280 | 831.619 | 85 | 18 | |

| A+2 | 831.883 | 100 | 832.121 | 100 | 290 | 831.869 | 100 | 17 | |

| A+3 | 832.134 | 93 | 832.372 | 88 | 290 | 832.120 | 88 | 17 | |

| A+4 | 832.382 | 64 | 832.622 | 61 | 290 | 832.370 | 61 | 15 | |

| A+5 | 832.634 | 28 | 832.872 | 33 | 290 | 832.620 | 33 | 17 | |

It has been proposed that Cu(II), in the presence of dissolved oxygen, could alter the redox state of Aβ(1–42), possibly by oxidizing Met-35 into its sulfoxide or sulfone analogs (30, 35, 36). Thus, since Aβ(1–28) does not comprise the methionine residue, it is conceivable that Cu(II) remains unchanged upon binding to Aβ(1–28). However, there has been a lack of direct spectroscopic evidence for chemical modifications of methionine even in Aβ(1–42) (except for samples produced under extreme conditions such as laser photolysis (45) or from autopsy (28)). It has been further contended that Met-35 oxidation could change the Cu(II) center to Cu(I), which remains coordinated by Aβ(1–42) (28, 35). If the methionine residue were chemically modified or the copper ion oxidation state were changed, the mass spectra of Aβ(1–42) treated with Cu(II) would contain peaks showing the addition of oxygen or different m/z values for the isotope clusters (vide supra).

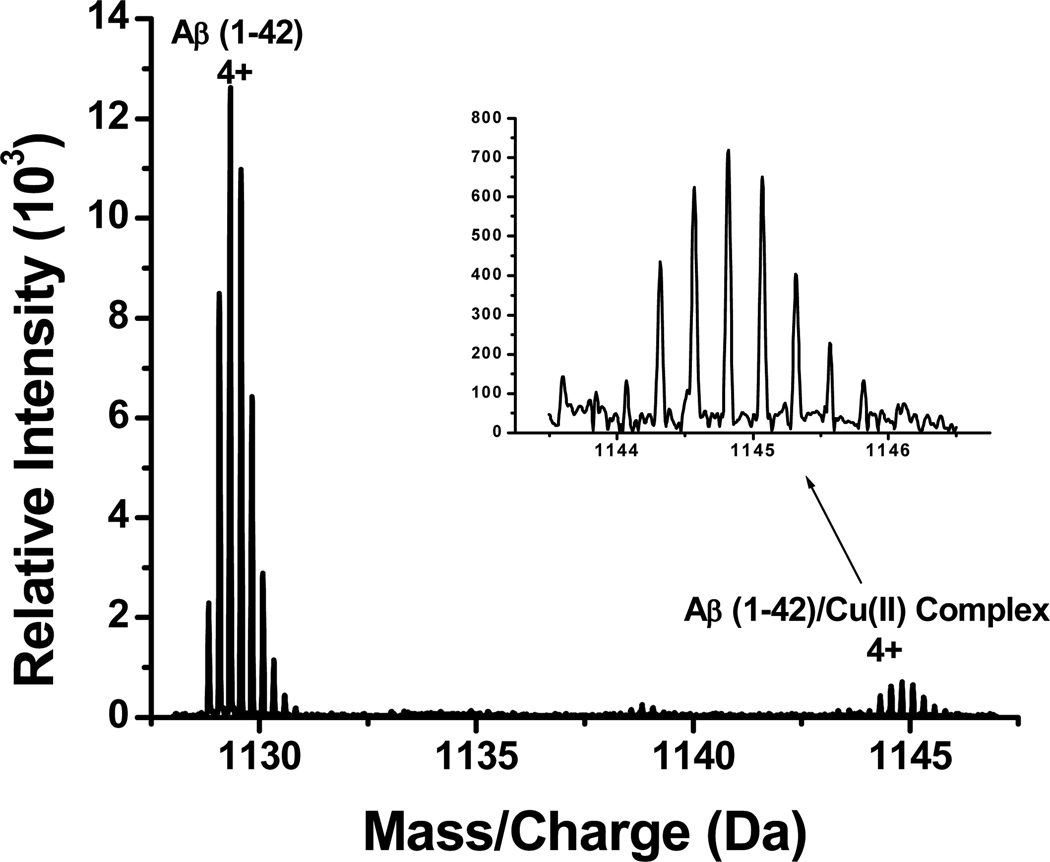

To verify whether the ligated Cu(II) could oxidize methionine, we collected mass spectra by spraying a solution containing Aβ(1–42) and Cu(II). Figure 2 is a representative mass spectrum in the mass range encompassing the 4+ charge states of Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–42)-copper ion complex. In Figure 2, peaks corresponding to both free Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex were observed, but any peaks associated with oxidized Aβ(1–42) were absent. This observation strongly suggests that, under the present experimental conditions, Aβ(1–42) itself cannot be oxidized by Cu(II). This observation is further supported by our voltammetric data (vide infra). A detailed analysis of the positions of the peaks corresponding to the 4+ and 5+ charge states again indicates that Cu(II) was not reduced (Table 2), consistent with the fact that the methionine residue was not chemically modified. Our results are also in good agreement with the report from the Zagorski group who conducted NMR measurements of Aβ(1–40) in the presence of Cu(II) and demonstrated that Met-35 oxidation and Cu(II) reduction did not occur (39). We conducted two additional experiments to show that Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex is indeed formed by mixing Cu(II) with Aβ(1–42). First, an FT-ICR mass spectrum collected from spraying a solution containing Aβ(1–42) did not exhibit peaks around m/z 1145 (Figure S2), indicating that Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) does not exist in the absence of Cu(II). The second experiment involves the confirmation of the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex peak with ESI-MS measurement on a linear-ion trap mass spectrometer. As can be seen in Figure S3 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information section, the peaks around 1145 are even more pronounced. Due to the greater mass resolving power of FTICR-MS and to be consistent in comparing the spectra among various species, we focused mainly on the FTICR-MS results.

Figure 2.

Positive-ion ESI-MS of an Aβ(1–42)/Cu(II) mixture at 1:1 ratio.

Table 2.

Extracting the copper oxidation state from the measured m/z values of the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) adduct

| Aβ(1–42)-Cu | Aβ-Cu(I) | Aβ-Cu(II) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meas. m/z | Meas. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Calcd. m/z | Calcd. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Dev. (ppm) |

Calcd. m/z |

Calcd. Rel. Abund. (%) |

Dev. (ppm) |

||

| 4+ Ion | A | 1144.068 | 19 | 1144.306 | 25 | 210 | 1144.054 | 25 | 12 |

| A+1 | 1144.317 | 62 | 1144.556 | 62 | 210 | 1144.304 | 62 | 11 | |

| A+2 | 1144.568 | 87 | 1144.807 | 92 | 210 | 1144.555 | 92 | 11 | |

| A+3 | 1144.818 | 100 | 1145.057 | 100 | 210 | 1144.805 | 100 | 11 | |

| A+4 | 1145.069 | 91 | 1145.308 | 87 | 210 | 1145.056 | 87 | 12 | |

| A+5 | 1145.318 | 56 | 1145.558 | 62 | 210 | 1145.306 | 62 | 11 | |

| A+6 | 1145.569 | 31 | 1145.809 | 37 | 210 | 1145.557 | 37 | 11 | |

| A+7 | 1145.819 | 19 | 1146.059 | 20 | 210 | 1145.807 | 20 | 10 | |

| 5+ Ion | A | 915.457 | 32 | 915.646 | 25 | 210 | 915.444 | 25 | 14 |

| A+1 | 915.656 | 54 | 915.847 | 62 | 210 | 915.645 | 62 | 12 | |

| A+2 | 915.856 | 83 | 916.047 | 92 | 210 | 915.856 | 92 | 12 | |

| A+3 | 915.055 | 100 | 916.247 | 100 | 210 | 916.046 | 100 | 10 | |

| A+4 | 916.256 | 94 | 916.448 | 87 | 210 | 916.246 | 87 | 11 | |

| A+5 | 916.456 | 66 | 916.648 | 62 | 210 | 916.446 | 62 | 11 | |

| A+6 | 916.656 | 40 | 916.848 | 37 | 210 | 916.647 | 37 | 10 | |

| A+7 | 916.859 | 23 | 916.049 | 20 | 210 | 916.847 | 20 | 12 | |

| A+8 | 917.063 | 10 | 916.249 | 9 | 200 | 917.048 | 9 | 16 | |

Redox potentials of Aβ-Cu(II) complexes

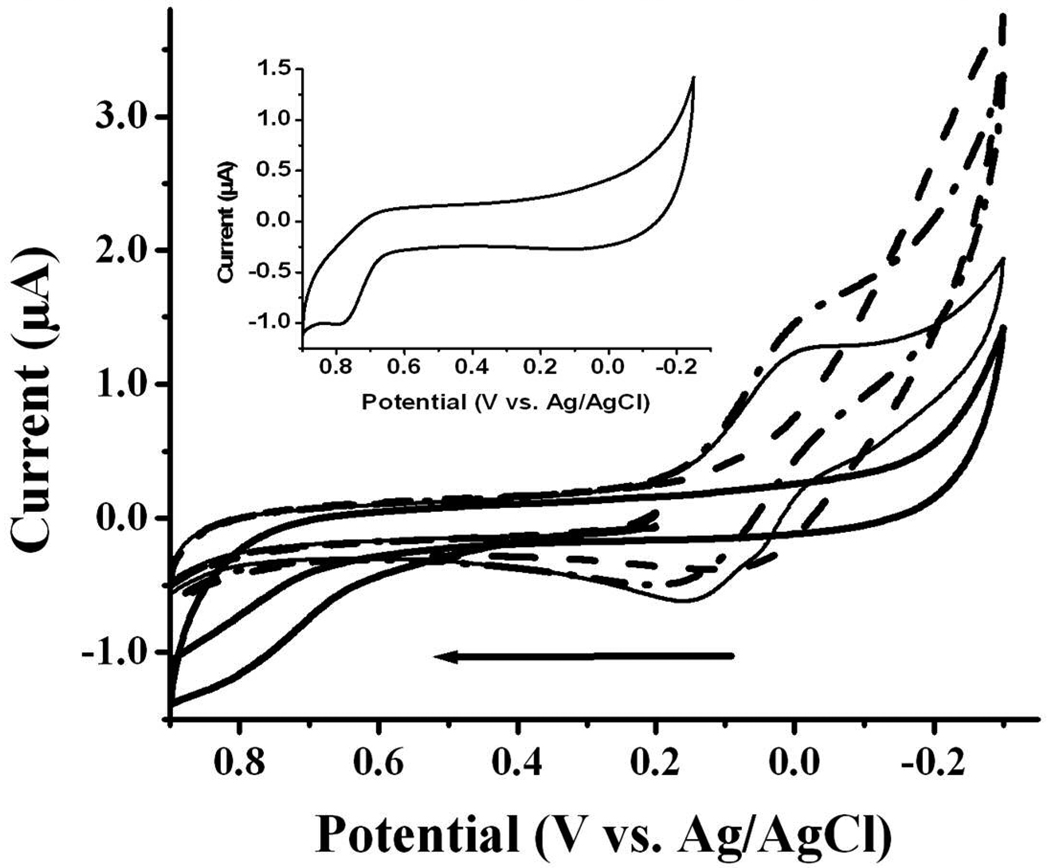

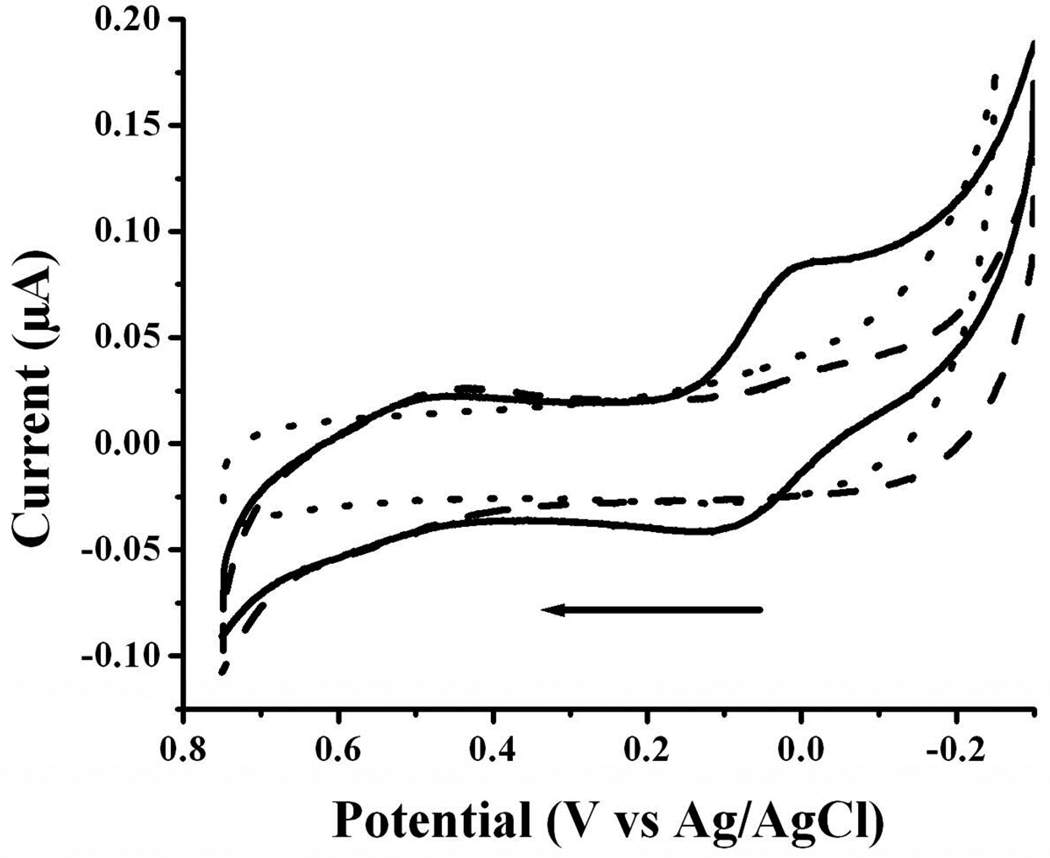

Since the proposed copper binding sites reside in the 16-amino acid N-terminal segment of Aβ(1–42), we first examined the redox behavior of Aβ(1–16) with or without Cu(II). Figure 3 is an overlay of voltammograms of Aβ(1–16) in a Cu(II)-free solution (thick solid curve), free Cu(II) (dashed curve), and Aβ(1–16) in the presence of an equimolar amount of Cu(II) (thin solid curve). To examine the effect of oxygen on the redox process involving Aβ(1–42), we also bubbled O2 into the mixture of Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16) and then recorded the voltammogram (dash-dot-dash curve). Notice that the voltammogram of Aβ(1–16) (thick solid curve) is rather different than that of Cu(II) (dashed curve), which produced an irreversible reduction peak starting from around 0.0 V. This peak can be attributed to the catalytic reduction of oxygen by electrogenerated Cu2O or CuOH layer (46). Due to the presence of trace amount of oxygen in solution, the follow-up catalytic oxidation of Cu2O or CuOH prevents Cu2O or CuOH from being further reduced to Cu(0). Therefore no copper stripping peak was observed. By thoroughly purging the solution with N2, a copper stripping peak was observed in the CV (Figure S4). The comparison of the voltammogram of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) (thick solid curve in Figure 3) to the Cu(II) reduction voltammogram shows that the reduction current of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) complex is smaller, even though the concentration of the former is twice as high as that of the latter. This suggests that Cu(II) is complexed, since the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) is expected to have a smaller diffusion coefficient. For the mixture of Aβ(1–16) and Cu(II), a pair of quasi-reversible waves (thin solid curve) was observed with an oxidation peak at 0.17 V and a reduction peak at ca. 0.0 V. The peak currents decrease inversely with the Aβ(1–16):Cu(II) molar ratio (Table S2). Apparently, catalytic reduction of O2 by electrogenerated Cu2O or CuOH occurs at a different potential (< −0.1 V) than the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) complex. We thus assign this pair of waves to the redox reactions between the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16)-Cu(I) complexes and report the reduction potential of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) to be 0.085 V vs. Ag/AgCl. We noticed that this potential value is similar to that of histidine-rich peptide-Cu(II) complexes (46–48). The fact that the reduction peak is higher than the oxidation peak suggests that a catalytic follow-up reduction (49) takes place after Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) is reduced. Another noteworthy point is that the oxidation peak became more pronounced as the potential scan rate is increased (data not shown). Furthermore, in the dash-dot-dash curve of Figure 3 the reduction peak was found to increase at the expense of the oxidation peak, suggesting the catalytic nature of the reaction and the involvement of O2.

Figure 3.

The cyclic voltammograms of 200 µM Aβ (1–16) (thick solid curve), 100 µM Cu(II) (dashed curve), a mixture containing 200 µM Aβ (1–16) and 200 µM Cu(II) (thin solid curve) and an O2-saturated Aβ (1–16)/Cu(II) mixture (dash-dot-dash). A voltammogram from a 50 µM tyrosine solution is shown in the inset. All solutions were prepared with a buffer containing 5 mM phosphate and 0.1 M Na2SO4 (pH 7.4) and data were obtained at a glassy carbon disk electrode with a diameter of 3 mm. The scan rate was 20 mV/s and the arrow indicates the initial scan direction.

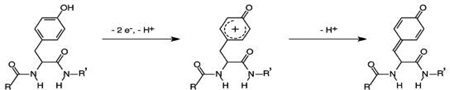

The Aβ (1–16) voltammogram exhibited a small and broad oxidation peak at the anodic side of Figure 3 (ca. 0.78 V). This oxidation peak is irreversible and disappears after the first cycle, and was observable even when Cu(II) was present (Note: the thin solid and dash-dot-dash curves in Figure 3 were acquired during the second cycle). Thus the peak must originate from the oxidation of a segment of the peptide and is irrelevant to the Cu(II) redox reaction. The peak potential is the same as that of Aβ(1–42) reported by and attributed to the Tyr-10 residue by Vestergaard et. al. (50). That the voltammogram of tyrosine solution alone (inset in Fig. 3) also showed an oxidation peak at a similar potential confirms our assignment. A tyrosine residue could undergo a two-electron, two-proton oxidation reaction (51), as depicted below:

In view that the hydrophobic segment in the Aβ-Cu(II) complex may affect the Aβ redox behavior, we conducted voltammetric experiments on Aβ(1–28) in the absence and presence of Cu(II). Superimposed in Figure 4 are the voltammograms of Aβ(1–28) alone (dashed curve) and Aβ(1–28) in the presence of an equimolar amount of Cu(II) (solid curve). The remarkable resemblance in the peak shapes between Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) and Aβ(1–28)-Cu(II) indicates that the more hydrophobic segment in Aβ(1–28) does not affect the redox potentials of both the Cu(II) center and the Tyr-10 residue. In addition, Aβ(1–28) (dashed curve) has similar redox behavior as Aβ(1–16). The main difference is that Aβ(1–28) is more prone to aggregation and causes a more significant adsorption onto the electrode surface. To alleviate this effect, we decreased the concentration of Aβ(1–28) for the acquisition of the voltammograms in Figure 4. Again, analogous to Aβ(1–16), Aβ(1–28) displayed an oxidation peak at ca. 0.78 V, which can be ascribed to the Tyr-10 oxidation.

Figure 4.

The cyclic voltammograms of 50 µM Aβ (1–28) (dashed curve) and a mixture of 50 µM Aβ (1–28)/50 µM Cu(II) mixture (solid curve) acquired at a glassy carbon disk electrode with a diameter of 3 mm at the scan rate of 20 mV/s. The arrow indicates the scan direction.

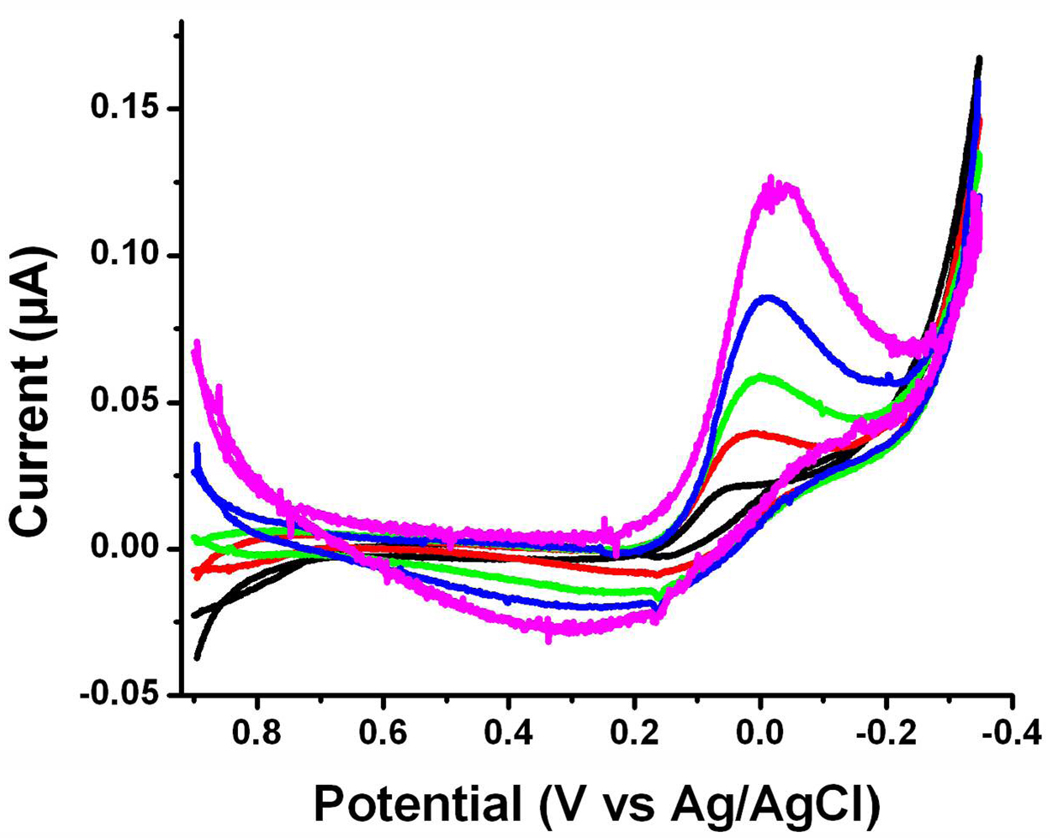

To clearly illustrate the effect of O2 on the magnitude of the Aβ-Cu(II) reduction peak, we subtracted the voltammograms of Aβ (1–28)/Cu(II) in a N2-purged solution from those of the same solution saturated with air (Figure 5). The plateaus at slow scan rates (e.g., 0.02 V/s) developed into peaks at higher scan rates. These features are again typical of an electrocatalytic reduction(49) and are also consistent with our findings related to Aβ(1–16) (vide supra). For oxygen to be catalytically reduced, oxygen molecules need to diffuse to and become associated with the newly electrogenerated Aβ(1–28)-Cu(I) center. We should note that, without background subtraction, the dependence of the steady-state current on O2 purged into the solution is not as obvious. This suggests that the O2 reduction is a diffusion-controlled process. Thus, O2, which is hydrophobic, appears to have interacted more strongly with the hydrophobic segment inherent in Aβ(1–28) and consequently its movement towards the Aβ-Cu(II) center is retarded (52).

Figure 5.

The cyclic voltammograms generated by subtracting voltammograms of a 1:1 mixture of Aβ(1–28)/Cu(II) in a N2-purged solution from those of the same mixture in an air-saturated buffer solution at different scan rates, 0.01 V/s (black), 0.02 V/s (red), 0.04 V/s (green), 0.08 V/s (blue) and 0.16 V/s (purple). A glassy carbon disk electrode with a diameter of 3 mm was used as the working electrode.

We then extended the same approach to the study of Aβ(1–42) and its complex with Cu(II). Since Aβ(1–42) has the strongest propensity to form aggregates, we added a small amount of dimethylsulfoxide (see Experimental) into the solution to impede the Aβ aggregation and to improve the reproducibility of the experiment. Several points can be extracted from the voltammograms in Figure 6. First, in the cathodic range (solid curve), the redox behavior of the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) is highly comparable to those of the Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–28) counterparts. Accordingly, we assigned the peak at ~0.02 V to the reduction of Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) to Aβ(1–42)-Cu(I) and conclude that the redox potential of the Cu(II) center remains largely unaffected by the length of the hydrophobic segment of Aβ. Although the reduction current is much greater than the oxidation current during scan reversal, purging the solution with oxygen and nitrogen led to little change in the peak heights. This is in contrast to the cases of the shorter Aβ variants (cf. Figures 3 and 5). The insensitivity of reduction or oxidation current of the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex to the oxygen concentration could be caused by the slow coordination of oxygen molecules with the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(I) center due to the greater steric hindrance imposed by the longer length and the greater hydrophobicity of the Aβ(1–42) strand.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of 50 µM Aβ (1–42) (dashed curve) and a mixture of 50 µM Aβ (1–42) and 50 µM Cu(II) (solid curve) in a 5 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M Na2SO4 and 10% dimethylsulfoxide or DMSO (pH 7.4). The background voltammogram was collected from the same electrolyte solution without Aβ (1–42) and Cu(II) (dotted curve). A glassy carbon disk electrode with a diameter of 3 mm was used as the working electrode. The scan rate was 20 mV/s.

In the anodic range of the CV, a pair of small peaks, with the reduction peak potential at ca. 0.48 V and the oxidation peak potential at ca. 0.6 V, were observed. Again, these peaks are independent of Cu(II), since the peaks in solid and dashed curves in Figure 6 are almost congruent in this range. These peaks were assigned to the redox reaction of the Cu(II) center to its Cu(I) counterpart by Huang et al. (35). However, given its close proximity to the oxidation peak of Tyr-10 (cf. inset of Figure 3 and the reported value (50)) and its independence of Cu(II) in the solution, we feel that the assignment to the Tyr-10 redox reaction is more plausible. The greater reversibility of tyrosine oxidation in Aβ(1–42) with respect to those of Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–28) may be partially contributed by the adsorbate nature of Aβ(1–42). Moreover, it is well known that adsorption of redox species onto the electrode tends to yield redox peaks whose positions are different than those originated from the soluble species (49).

Aβ-Cu(I) complex catalyzes the reduction of oxygen to hydrogen peroxide

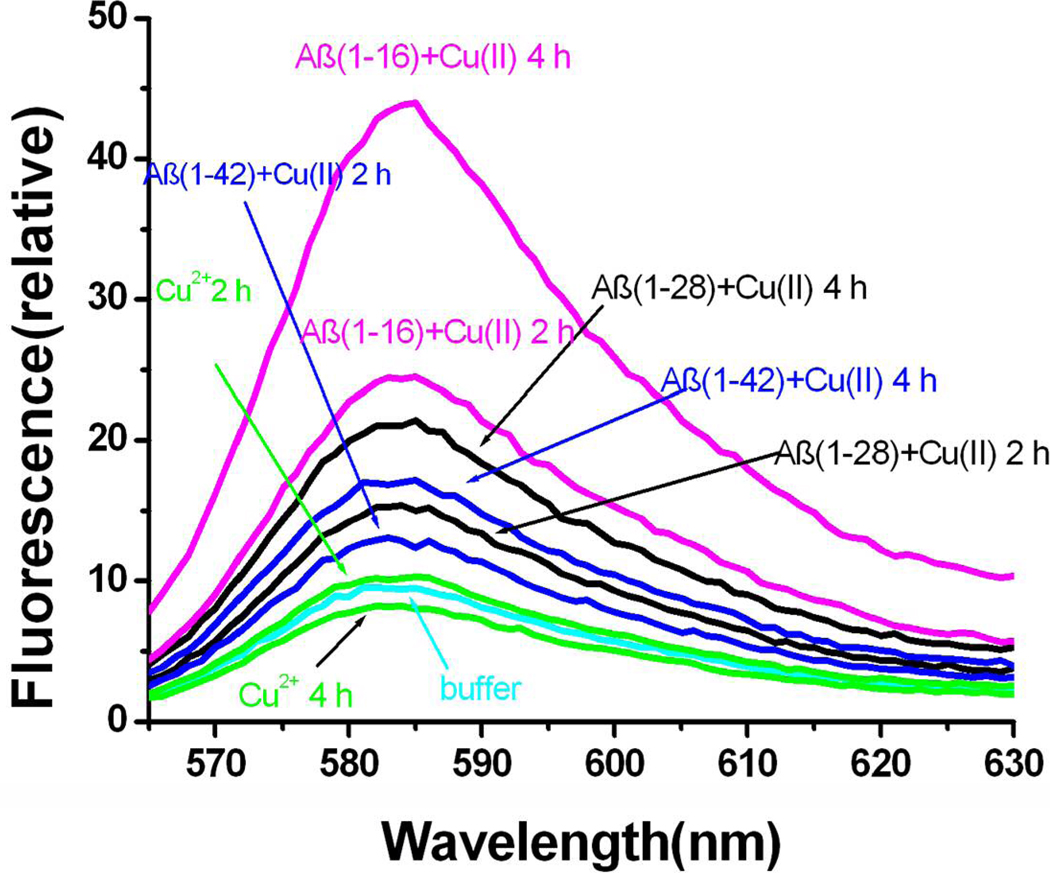

As mentioned above, the reduced form of the Aβ-Cu(II) complex can catalyze oxygen reduction, producing H2O2 as one of the possible products (30, 35, 37). To directly link the redox state of the Cu-containing Aβ complex to the H2O2 production, we carried out spectrofluorometric detection of H2O2 from Aβ(1–16)/Cu(II), Aβ(1–28)/Cu(II), and Aβ(1–42)/Cu(II) solutions that had been subject to controlled potential electrolyses.

After electrolyses of these solutions at 0.07 V for a period of time, the solutions were analyzed by a hydrogen peroxide detection kit. We chose 0.07 V because it is at the plateaus of the electrocatalytic reduction peaks of all the Aβ variants (thin solid curve in Figure 3 and solid curves in Figures 4 and 6). At this potential the complication of possible catalytic reduction of oxygen by unbound copper ion can also be excluded (i.e., the potential is more positive than the onset potential of free Cu(II) reduction; cf. the dashed curve in Figure 3). As shown in Fig. 7, for all three Aβ variants, the fluorescence peak heights increase with the electrolysis time. Moreover, the resorufin fluorescence peaks are significantly greater than those in the buffer and Cu(II) solutions. Notice that the fluorescence intensity from the electrolyzed Cu(II) solution was not different than that from the buffer solution, again suggesting that the catalytic reaction involving Cu(II) and O2 occurs at a different potential. Aβ-Cu(II) complex solutions without being electrolyzed also exhibited similar responses to those of the buffer solution. All these observations indicate that it is the reduced Aβ-Cu(II) complex that is responsible for the H2O2 production.

Figure 7.

The fluorescence spectra of resorufin for mixtures containing Cu(II) and different Aβ species upon electrolyses for different times: 100 µM Aβ (1–16)/Cu(II) (pink curves), 100 µM Aβ (1–28)/Cu(II) (black curves), 50 µM Aβ (1–42)/Cu(II) (blue curves), 100 µM Cu (II) solution (green curves) and buffer solution (light blue). In the electrolyses, a normal three-electrode system was used and a glassy carbon working electrode with an area of 0.071 cm2 was held at 0.07 V. The solution volume for each was 300 µL. The electrolysis times are indicated next to the respective curves.

A point particularly worth noting is that the fluorescence intensity increases inversely with the length of the Aβ variants. This explains why the catalytic reduction current becomes less sensitive to the concentration of dissolved oxygen as the Aβ strand becomes longer. Such a consistency reinforces our earlier contention that the movement of oxygen to the electrogenerated Cu(I) center is dependent on both the length and hydrophobicity of the Aβ strand.

DISCUSSION

As mentioned in the Introduction, it is generally believed that the Cu(II) binding domain in Aβ is within the segment comprising residues 1–14 (30, 34, 38, 53), with His-6 , His-13, and His-14 having the strongest metal binding affinities. Our ESI-FTICR-MS study has demonstrated that the binding ratio between Cu(II) and Aβ(1–28) or Aβ(1–42) is 1:1, which is consistent with results by Karr et al. (38) and Garzon-Rodriguez et. al. (54). We did not find other binding ratios as reported by others (29, 34). The ESI-FTICR-MS results are also in good agreement with our voltammetric data, which showed that the reduction current of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) complex leveled off once the molar ratio between Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16) had exceeded 1:1.

The reduction potentials of Aβ-Cu(II) deduced from Figures 3, 4, and 6 allowed us to gain insight about the factors or redox species that could be involved in the reduction of the Aβ-Cu(II) complex in the cellular milieu. Thus, for example, to reduce Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), a species must have a reduction potential that is more negative (cathodic) than 0.08 V vs. Ag/AgCl or 0.28 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode, NHE (cf. Figure 6 and Table 3). Since the Tyr-10 redox peak appeared at ~0.78 V, we conclude that Tyr-10 cannot reduce Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) in vitro. Several reports have suggested that Tyr-10 participates in the metal ion coordination. A Raman analysis of samples from deceased AD patients’ brains indicated that the tyrosine residue in Aβ(1–42) was oxidized (28). Thus, it is clear that the Aβ-Cu(II) complex is not the sole species responsible for the Tyr-10 oxidation, and other cellular species or processes must be involved. Another amino acid residue that is susceptible to oxidation and has been implicated in the reduction of Aβ-Cu(II) and generation of ROS such as H2O2 is Met-35 (30, 45, 55). However, from the ESI-FTICR-MS data, we did not find ions corresponding to oxidized or chemically modified (e.g., oxygenated adducts) Aβ(1–42) and/or Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II). Previously the peak potential for the Met-35 oxidation to its radical cation has been reported to exceed 1.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl in aqueous solution (56). Such a value is almost 1.2 V more positive than the Aβ-Cu(II) reduction potential, suggesting that Met-35 would not be a viable reductant under the in-vitro condition. Moreover, in the natively unstructured Aβ(1–40) or Aβ(1–42) monomer, there is a wide separation between the metal center (close to the N terminus) and Met-35 (in the vicinity of the C terminus), which is unfavorable for facile ET. Therefore, based on the MS and voltammetric data, we also ruled out the possibility that Met-35 had undergone oxidation reactions with Cu(II) in solution and/or Cu(II) in the complex without involving other cellular species. This conclusion is in agreement with what was found by Hou and Zagorski (39).

Table 3.

Redox potentials of Aβ-Cu(II) complex and common redox species of biological relevance.

| System | E0’ (V vs NHE) |

|---|---|

| Norepinephrine | 0.384(1) |

| Epinephrine | 0.372(1) |

| Dopamine | 0.370(2) |

| O2/H2O2 | 0.295(4) |

| Cytochrome a | 0.290(1) |

| Aβ-Cu(II) | 0.280 |

| Cytochrome c | 0.250(1) |

| Hemoglobin | 0.152(3) |

| CoQ/CoQH2a | 0.100(1) |

| Ascorbic acid | 0.051(3) |

| Cytochrome b | 0.040(1) |

| Fumarate/Succinate | 0.031(4) |

| Myoglobin | 0.005(1) |

| Crotonyl-CoA/Butyryl-CoA | −0.015(4) |

| FMN/FMNH2b | −0.120(1) |

| Oxaloacetate/malate | −0.166(4) |

| Pyruvate/lactate | −0.185(4) |

| Glutathione | −0.228(1) |

| Vitamin B12 | −0.244(1) |

| NAD+/NADHc | −0.320(1) |

| FAD/FADH2d | −0.327(1) |

Coenzyme Q (ubiquinone) oxidized/reduced forms

Flavin mononucleotide oxidized/reduced forms

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidized/reduced forms

Flavin adenine dinucleotide oxidized/reduced forms

G. Dryhurst, K. M. Kadish, F. Scheller, R. Renneberg, Biological Chemistry, Vol. 1, Academic Press, New York, London

D. C.-S. Tse, T. Kuwana, Anal. Chem., 50 (1978), 1315.

B. E. Conway, Electrochemical Data, Greenwood Press Publisher. New York

A. L. Lehninger, D. L. Nelson, M. M. Cox, Principles of Biochemistry, Worth Publishers. New York

In solution, Aβ binds Cu(II), and under an externally applied potential, the resultant Aβ-Cu(II) complex can be reduced to Aβ-Cu(I), once the cathodic scan has passed ~0.080 V:

| (1) |

Notice that the reduction potential for Aβ-Cu(II) complex is quite different than that reported by Huang et al.(35). As the redox potentials of copper complexed by histidine-containing peptides are in the range between −0.1 and 0.1 V (46–48, 57, 58), we believe that the redox potential around 0.1 V is more reasonable.

In the presence of dissolved oxygen, the electroreduced Aβ-Cu(I) center could react with O2 in solution, producing H2O2:

| (2) |

The above reaction is responsible for the O2-dependent reduction peaks exhibited in Figures 3–6. As the potential for the Aβ-Cu(II)/Aβ-Cu(I) (0.28 V vs. NHE) is lower than that for O2/H2O2 (0.295 V vs. NHE, Table 3), reaction (2) is thermodynamically allowed. A much higher potential for Aβ-Cu(II)/Aβ-Cu(I), as that reported in Ref (35) (0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl), however, would cause Reaction (2) to proceed in the reverse direction (i.e., H2O2 oxidation). Thus, our measured potential value explains the catalytic reduction of O2 to H2O2 better. We should point out that the present study cannot rule out the possibility that some O2 might be reduced to H2O in a similar fashion to that catalyzed by Cu(II)-containing enzymes such as laccase.(59) However, the Aβ-Cu(II) complexes are not considered to be “enzymes”, and the direct four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O typically involves multiple copper centers.(59) Furthermore, based on the H2O2 detected and other published data (37), the reactions outlined above should constitute the major mechanism. To further confirm the proposed mechanism, we simulated the kinetics of ET reaction and the follow-up catalytic oxygen reduction. The simulated voltammogram, overlaid with the experimentally measured one, is provided in the Supporting Information, together with the parameters used for the simulation. The heterogeneous ET rate constant for Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) at the electrode was estimated to be about 5 × 10−4 s−1 and the follow-up catalytic reaction rate constant was deduced to be about 1000 M−1 s−1. The reasonable agreement between the experimental and simulated voltmmograms suggests that the proposed mechanism is quite likely. Moreover, the rather high reaction rate constant deduced for equation 2 indicates that there is a strong tendency for the reduced Aβ-Cu(II) complex to catalytically reduce O2 to H2O2. The rapid depletion of ascorbic acid (Figure S6), initiated by the Aβ-Cu(II) complex, indicates the fast turnover rate (vide infra).

Based on our spectrofluoremetric measurements (Figure 7), it is clear that a prerequisite for H2O2 generation is the conversion of Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I). The difference in the dependence of the catalytic peak currents on the O2 content in solution among the three Aβ-Cu(II) complexes implies that in AD patients, the amount of H2O2 produced in Reaction (2) is likely to be dependent on the Aβ sequence and length. It is generally known that Aβ(1–42) has a much stronger tendency to aggregate than Aβ(1–40), and the Aβ(1–42) content in senile plaques of AD patients is disproportionately high (60). Given the relatively high affinity of Aβ species towards metal ions, it has been shown that Aβ and its aggregates, upon complexation with redox-active metal ions such as Cu(II) and Fe(III), can generate H2O2 (35, 37). The level of H2O2 can be sufficiently high to cause cell death (37). Based on the aforementioned dependence of H2O2 amount on the strand length of Aβ species, we postulate that there might exist an alternative process responsible for the slow onset of AD symptom. If Reactions (1) and (2) are at work, the amount of H2O2 generated must be dependent on all the reactants (i.e., Aβ, Cu(II), and O2). Since in senile plaques the content of Aβ and concentration of Cu(II) are high and the function of brains requires a constant supply of large amounts of O2 (61), one would expect that H2O2 concentration be substantially high. In addition to metabolic degradation of species that can potentially generate ROS and scavenging of ROS (including H2O2) by antioxidants, we think that the slow diffusion of O2 to the metal center in the Cu(II)-Aβ complex should have dramatically hindered the H2O2 generation. Regarding the dependence of H2O2 generation on the Aβ sequence, it is interesting to note that mice do not develop AD (62) and its Aβ is mutated at two of the metal binding sites, viz., His-13 and Tyr-10 (replaced by Arg and Phe, respectively). The decreased binding affinity of such a mutated Aβ towards Cu(II) leads to a dramatically lower H2O2 production (37). In the case of familial AD, the Aβ is point-mutated, which causes early onset AD. Interestingly, none of the mutations occurs in the metal binding region. These facts strongly suggest the important roles of metal binding and H2O2 production in the pathogenesis of AD.

During the CV scan reversal, Aβ-Cu(I) molecules that have not been completely oxidized by O2 in solution (cf. thin solid curve in Figure 3 and thick solid curves in Figures 4 and 6), will be reoxidized:

| (3) |

The concentration of Aβ-Cu(I) depends on the catalytic turnover rate, which is in turn governed by the accessibility of the Aβ-Cu(I) complex to oxygen and the oxygen concentration in solution. A declined oxygen level in solution results in the availability of more Aβ-Cu(I), which leads to a greater oxidation current during the reverse potential scan (cf. Figure 3). The function of metalloproteins in a biological process involving O2 requires the binding to and activation of diatomic O2 molecules by the metal center(s). Recent studies have captured the O2-containing intermediates (63, 64). Similarly, the catalytic reduction of O2 by Aβ-Cu(I) also entails the binding of O2 to the copper center. It is conceivable that a longer Aβ segment will increase the steric hindrance for O2 binding to the copper center and decrease the catalytic turnover rate. This is in accord with our experimental results. Given the slow and gradual development of AD, our contention appears to be plausible.

As stated in previous sections, a prerequisite for the catalytic production of H2O2 is the reduction of Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I) and the subsequent binding of O2. This process would not occur in vitro without a suitable electron donor. However, Aβ-Cu(II) complex could be reduced in vivo by redox reactions involving easily oxidizable cellular species (i.e., antioxidants). There exists a wide range of intracellular and extracellular electroactive species and antioxidants, some of which, together with their reduction potentials, are listed in Table 3.

Species whose reduction potentials are more positive than the Aβ-Cu(II) reduction potential (0.280 V) are incapable of reducing Aβ-Cu(II). These include some important redox-active neurotransmitters such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. This is interesting, since, to our knowledge, there is no evidence directly linking the appearance of Aβ aggregates or senile plaques to the deficiency of these neurotransmitters. It is a well known fact that another neurodegenerative disease, Parkinson’s disease, is directly related to dopamine deficiency and loss of dopaminogenic neurons. The species listed inTable 3 that could (i.e. potentials more negative) reduce the Aβ-Cu(II) complex can be classified into three categories: extracelluar species (e.g., ascorbic acid), intracellular redox buffers (e.g., glutathione), and membrane-bound redox species (especially those associated with mitochondria that governs cellular respiratory processes and bioenergetics).

Outside the neuronal cells, reduction of Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I) by ascorbic acid and vitamin B12 is thermodynamically favored (Table 3). The reduced Aβ-Cu(I) can then catalyze the reduction of oxygen to form hydrogen peroxide. The as-formed hydrogen peroxide can either react further with antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and vitamin B12 or attack cell membrane and other organelles in brain. This certainly will deplete the antioxidants and damage the cellular defense system, making the cells vulnerable. To verify that the Aβ-Cu(II) reduction by ascorbic acid is kinetically facile, we acquired CVs of ascorbic acid in the absence and presence of Aβ-Cu(II). As shown in Figure S6, without Aβ(1–16) and Cu(II) in the solution, an irreversible oxidation peak of ascorbic acid at ca. 0.42 V was observed. The irreversible reduction is due to the ring-closure reaction following the ET reaction, as shown in equation (4):

| (4) |

When Aβ-Cu(II) is present, the addition of an equimolar amount of ascorbic acid did not show the characteristic irreversible ascorbic acid oxidation peak. Only after the addition a few more molar equivalents did the oxidation peak appear in the first potential scan (Figure S6). Interestingly, the peak quickly disappeared in the second scan. When the solution was thoroughly purged, the ascorbic acid oxidation peak was observable regardless of the presence of Aβ-Cu(II). These observations thus demonstrate that ascorbic acid can rapidly reduce Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I) and the resultant Aβ-Cu(I) catalyzes the oxygen reduction. The overall catalytic redox reaction cycle coverts ascorbic acid to dehydroacorbic acid. The rapid depletion of ascorbic acid is also consistent with the high chemical reaction rate constant in the aforementioned kinetic simulation.

There have been many mechanisms suggesting that Aβ penetrates cell membranes and enters cytoplasma (65–67). Aβ has been shown to exist inside (22, 68–70) and outside of neuronal cells in AD-affected brains. In PC12 cells and human fibroblasts Aβ oligomers were found to adsorb onto the cell surface and became internalized into the cytosol (71, 72). Given the relatively high binding affinity of Aβ to Cu(II) (29), Cu(II)-bound Aβ monomers and oligomers should be capable of penetrating the neuronal cell membrane. In addition, it is purported that APP from which Aβ is cleaved can function as a copper chaperone, regulating the intracellular copper concentration and homeostasis (73). Inside the neuronal cells, the glutathione redox couple (GSH/GSSG), present at millimolar concentrations, has a high redox buffering capacity. The GSH/GSSG couple not only maintains the function of mitochondria (74) but also regulates the apoptosis of cells (75–79). From Table 3, the reduction of Aβ-Cu(II) complex to Aβ-Cu(I) by glutathione is favored thermodynamically and H2O2 produced via Reaction (2) could consequently disrupt the potentiation of the GSH/GSSG couple. The possible decline in the cellular glutathione may not only induce abnormal apoptosis but also cause dysfunction of mitochondria. Another intracellular species whose reduction potential is lower than Aβ-Cu(II) complex is pyruvate, which serves as the fuel for mitochondria-mediated metabolic process. As shown by the potential values in Table 3, a redox reaction between Aβ-Cu(II) and pyruvate is possible. Similarly, given the presence of a high concentration of O2 in brain and particularly in neuronal cells (61), the catalytic reduction of O2 to H2O2 by Aβ-Cu(I) is likely to occur. The H2O2 would subsequently oxidize more pyruvate molecules and cause a depletion of the cellular pyruvate concentration. As a result, ATP production is decreased and mitochondria are starved energetically. This p rocess may have some relevance to the observed decline in the production of ATP in AD patients (80–83). In line with our suggestion, therapeutic treatments of AD patients with pyruvate derivatives have shown promises in alleviating AD symptoms (84).

It has been well documented that mitochondrial insufficiencies contribute significantly to the pathophysiology of AD and mitochondrial dysfunction is also a hallmark of AD (80, 85–87). However, the intricate relationship between AD and mitochondrial dysfunction awaits further elucidation. Aβ has been found to exist inside mitochondria and deposited on mitochondria membranes in AD brains (81, 88). Recent studies demonstrated that, in the presence of Cu(II), Aβ inhibits the activity of cytochrome c oxidase in mitochondria (22–24, 82). This provides a possible link between the dysfunction of mitochondria and Aβ-Cu(II). The function of mitochondria relies on the uninterrupted ET processes in the cascade of events at the membrane and in the intermembrane space. As shown in Table 3, the redox reactions of Aβ-Cu(II) with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), Coenzyme Q (CoQH2), cytochrome b, cytochrome c1 and cytochrome c in the ET chain are all thermodynamically allowed. If there is a reaction of Aβ-Cu(II) with any of the species, the normal electron flow will be side-tracked, leading dysfunction of mitochondria and triggering a mitochondrial death pathway. We should note that mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to be associated with the AD development (80, 85, 86, 89).

Overall, Aβ-Cu(II) complex can react with redox-active molecules essential to neuronal cells and present in biological fluids. Thus, the accurate measurements of the redox potentials of various Aβ-Cu(II) species and the confirmation of H2O2 generation by Aβ-Cu(I) complex provides new insight into AD pathogenesis and offers some possible interpretations about certain AD symptoms and the roles of metal ions in AD neuropathology.

CONCLUSIONS

We have studied, for the first time, the interaction of Aβ with Cu(II) by high-resolution mass spectrometry. It reveals that Cu(II) coordinates with Aβ in a 1:1 ratio. Independent of the methionine residue, the oxidation state of the copper center in the complex is 2+. The presumed reduction reaction of Cu(II) center to Cu(I) cannot occur in vitro. The redox chemistry of the complexes of Aβ(1–16), Aβ(1–28), or Aβ(1–42) with Cu(II) was systematically investigated by cyclic voltammetry and the redox potential for the reduction of the copper center was determined to be 0.08 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). The Aβ-Cu(I) electrogenerated was found to catalyze the reduction of oxygen and produce hydrogen peroxide. The remarkable similarity among the voltammetric behaviors of these three complexes excludes the possibility that methionine-35 can be oxidized by the Cu(II) center. In addition, we found that the diffusion of oxygen to the Cu(II) center is dependent on the peptide length (steric hindrance) and hydrophobicity. To our knowledge, this is the first work showing that Aβ-Cu(I) can be controllably generated and studied in the presence and absence of O2. The implication of the redox properties of the complex is discussed in the biological context. Based on the redox potentials of Aβ, Aβ-Cu(II) complexes, and common redox-active biomolecules, a number of redox reactions could occur. As a result, antioxidants may be depleted, which may destroy the normal protective system against oxidative stress. Using voltammetry and digital simulation, we show that the thermodynamically allowed reduction of Cu(II)-Aβ(1–42) by ascorbic acid, is kinetically facile. The redox reactions of the Aβ-Cu(II) complex with species in the ET chain of mitochondria are also thermodynamically favorable. Although whether these reactions occur in vivo remain to be investigated, the possibility raises an important aspect that such reactions could sidetrack the normal electron flow in the respiratory process of mitochondria.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- ADHP

10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- CV

Cyclic voltammetry

- ESI-FTICR-MS

Electrospray ionization-Fourier transform ion cyclotron mass spectrometry

- ET

Electron transfer

- Met-35

Methionine at position 35

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Tyr-10

Tyrosine at position 10

Footnotes

This work was supported by research grants (Grant No. GM 08101 to F. Z. and R01 CA101864 to Y. W.) and partially supported by the NIH-RIMI Program at California State University-Los Angeles (P20 MD001824-01).

Supporting Information Available: ESI-FTICR mass spectra of Aβ(1–28) and Aβ(1–42), an linear-ion trap mass spectrum of the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex, a voltammogram of Cu(II) in a thoroughly deaerated solution, voltammograms of ascorbic acid in the presence of Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), and a table showing the relation between the Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) complex and the molar ratio of Cu(II) and Aβ(1–42) are included in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multihaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. Amyloid production secretase. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in alzheimer disease and down syndrome. PNAS. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenner GC, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and charaterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hensley K, Hall N, Subramaniam R, Cole P, Harris M, Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Gabbita P, Wu JF, Carney JM, Lovell M, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Brain regional correspondence between Alzheimer's disease histopathology and biomarkers of protein oxidation. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2146–2156. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CD, Carney JM, Starke-Reed PE, Oliver CN, Stadtman ER, Floyd RA, Markesbery WR. Excess brain oxidation and enzyme dysfunction in normal aging and Alzheimer' disease. PNAS. 1991;88:10540–10543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyras L, Cains NJ, Jenner A, Jenner P, Halliwell B. An assessment of oxidative damage to proteins, lipids and DNA in brains from patients with alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:2061–2069. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markesbery WR, Carney JM. Oxidative alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mecocci P, MacGarvey U, Kaufman AE, Koontz D, Shoffner JM, Wallace DC, Beal MF. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA show marked age-dependent increases in human brain. Ann. Neurol. 1993;34:609–616. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mecocci P, MacGarvey U, Beal MF. Oxidative damage to mitochodrial DNA is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1994;36:747–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitsch RM, Bluztajn JK, Pittas AG, Slack BE, Growdon JH, Wurtman RJ. Evidence for a membrane defect in Alzheimer's disease brain. PNAS. 1992;89:1671–1675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svennerholm L, Gottfries CG. Membrane lipids, selectively diminished in Alzheimer's brains, suggest synapse loss as a primary event in early-onset and demyelination in late-onset form. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:1039–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subbarao KV, Richardson JS, Ang LC. Autopsy samples of Alzheimer's cortex show increased peroxidation in vitro. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:342–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus DL, Thomas C, Rodriguez C, Simberkoff K, Tsai JS, Strafaci JA, Freedman ML. Increased peroxidation and reduced antioxidant enzyme activity in Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Neurol. 1998;150:40–44. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varadarajan S, Yatin S, Aksenova M, Butterfield DA. Review:Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:184–208. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sims NR. Energy metabolism, oxidative stress and neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5:435–440. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1366:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker WD., Jr Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1991;640:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de La Monte SM, Luong T, Neely TR, Robinson D, Wands JR. Mitochondrial DNA damage as a mechanism of cell loss in Alzheimer's disease. Lab. Invest. 2000;80:1323–1335. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer I, Zierz S, Moller HJ. A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neuobiol. Aging. 2000;21:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valla J, Bernt JD, Gonzalez-Lima F. Energy hypo metabolism in posterior cingulate cortex of Alzheimer's patients: superficial laminar cytochrome oxidase associated with disease duration. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:4923–4930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshpande A, Mina E, Glabe C, Busciglio J. Different conformations of amyloid beta induce neurotoxicity by distinct mechanisms in human cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6011–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crouch PJ, Barnham KJ, Duce JA, Blake RE, Masters CL, Trounce IA. Copper-dependent inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase by abeta requires reduced methionine at residue 35 of the abeta peptide. J. Neurochem. 2006;99:226–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crouch PJ, Blake R, Duce JA, Ciccotosto GD, Li Q-X, Barnham KJ, Curtain CC, Cherny RA, Cappai R, Dyrks T, Masters CL, Trounce IA. Copper-dependent inhibition of human cytochrome c oxidase by a dimeric conformer of amyloid-beta. J. Neurosci. 2005;19:672–679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4276-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlief ML, Craig AM, Gitlin JD. NMDA receptor activation mediates copper homeostasis in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:239–246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howell GA, Welch MG, Frederickson CJ. Stimulation-induced uptake and release of zinc in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1984;308:736–738. doi: 10.1038/308736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtain CC, Ali FE, Smith DG, Bush AI, Masters CL, Barnham KJ. Metal Ions, pH, and cholesterol regulate the interactions of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β peptide with membrane lipid. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2977–2982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong J, Atwood CS, Anderson VE, Siedlak SL, Smith MA, Perry G, Carey PR. Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid-β within isolated senile plaque cores: Raman microscopic evidence. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2768–2773. doi: 10.1021/bi0272151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atwood CS, Scarpa RC, Huang X, Moir Robert D, Jones WD, Fairlie DP, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Characterization of copper interactions with Alzheimer amyloid-β peptides: identification of an attomolar-affinity copper binding site on amyloid β1–42. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:1219–1233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtain CC, Ali F, Volitakisi I, Chernyi RA, Norton RS, Beyreuther K, Barrow CJ, Mastersi CL, Bush AI, Barnham KJ. Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-β binds copper and zinc to generate an allosterically ordered membrane-penetrating structure containing superoxide dismutase-like subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20466–20473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowalik-Jankowska T, Ruta M, Wisniewska K, Lankiewicz L. Coordination abilities of the 1 – 16 and 1 – 28 fragments of β-amyloid peptide towards copper(II) ions: a combined potentiometric and spectroscopic study. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003;95:270–282. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Mardesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishino S, Nishida Y. Oxygenation of amyloid beta-peptide (1–40) by copper(II) complex and hydrogen peroxide system. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2001;4:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. Copper binding to the amyloid-beta peptide associated with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18169–18177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X, Cuajungco MP, Atwood CS, Hartshorn MA, Tyntall JDA, Hanson GR, Stokes KC, Leopold M, Multhaup G, Goldstein LE, Scarpa RC, Saunders AJ, Lim J, Moir RD, Glabe C, Bowden EF, Masters CL, Fairlie DP, Tanzi RE, Bush A. Cu(II) potentiation of Alzheimer's Aβ Neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37111–37116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch T, Cherny RA, Bush AI. Oxidative processes in Alzheimer's disease: the role of Aβ–metal interactions. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:445–451. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opazo C, Huang X, Cherny RA, Moir RD, Roher AE, White AR, Cappai R, Masters CL, Tanzi RE, Inetstrosa NC, Bush AI. Metalloenzyme-like activity of Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40302–40308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karr JW, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. Amyloid-β binds Cu2+ in a mononuclear metal ion binding site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13534–13538. doi: 10.1021/ja0488028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou L, Zagorski MG. NMR reveals anomalous copper(II) binding to the amyloid Aβ peptide of Alzheimer's disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9260–9261. doi: 10.1021/ja046032u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atwood CS, Moir RD, Huang X, Scarpa RC, Bacarra NME, Romano DM, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer Aβ by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12817–12826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bott AW. Redox properties of electron transfer metalloproteins. Current Separations. 1999;18:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fezui Y, Hartley D, Harper J, Khurana R, Walsh D, Condron M, Selkoe D, Lansbury P, Fink AL, Teplow D. An improved meethod of preparing the amyloid β-protein for fibrillogenesis and neurotoxicity experiments. Amyloid: Int. J. Exp. Clin. Invest. 2000;7:166–178. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou L, Kang I, Marchant RE, Zagorski MG. Methionine 35 oxidation reduces fibril assembly of the amyloid Aβ (1𠄴2) peptide of Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40173–40176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoneich C, Pogocki D, Hug GL, Bobrowski K. Free radical reactions of methionine in peptides: mechanisms relevant to beta-amyloid oxidation and Alzheimer's disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13700–13713. doi: 10.1021/ja036733b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weng YC, Fan F-RF, Bard AJ. Combinatorial Biomimetics. Optimization of a composition of copper(II) poly-L-histidine complex as an electrocatalyst for O2 reduction by scanning electrochemical microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17576–17577. doi: 10.1021/ja054812c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonomo RP, Conte E, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Purrello R, Rizzarelli E. Copper(II) complexes with cyclo(L-aspartyl) and cyclo(L-glutamyl-L-glutamyl) derivatives and their antioxidant properties. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1996;1996:3093–3099. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonomo RP, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Purrello R, Rizzarelli E, Tabbi G. Coordinating properties of cyclopeptides. Thermodynamic and spectroscopic study on the formation of copper(II) complexes with cyuclo(gly-his)4 and cyclo(Gly-His-Gly)2 and their superoxide dismutase-like activity. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1998;1998:3851–3857. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vestergaard M-D, Kerman K, Saito M, Nagatani N, Takamura Y, Tamiya E. A rapid label-free electrochemical detection and kinetic study of Alzheimer's amyloid beta aggregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11892–11893. doi: 10.1021/ja052522q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brabec V, Mornstein V. Electrochemical behavior of proteins at graphite electrodes: II electrooxidation of amino acids. Biophys. Chem. 1980;12:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(80)80048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem. J. 1984;219:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miura T, Suzuki K, Kohata N, Takeuchi H. Metal binding modes of Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide in insoluble aggregates and soluble complexes. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7024–7031. doi: 10.1021/bi0002479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garzon-Rodriguez W, Yatsimirsky AK, Glabe CG. Binding of Zn(II), Cu(II), and Fe(II) ions to Alzheimer's all peptide studied by fluorescence. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2243–2248. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varadarajan S, Kanski J, Aksenova M, Lauderback C, Butterfield DA. Different mechanisms of oxidative stress and neurotoxicity for Alzheimers Aβ (1–42) and Aβ (25–35) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5625–5631. doi: 10.1021/ja010452r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanaullah, Wilson GS, Glass RS. The effect of pH and complexation of amino acid functionality on the redox chemistry of methionine and X-ray structure of [Co(en)2(L-Met)](ClO4)2.H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1994;55:87–99. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(94)85031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonomo RP, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Rizzarelli E, Tabbi G. Copper binding modes in the prion octapeptide PHGGGWGQ, a spectroscopic and voltammetric study. Eur. Chem. J. 2000;6:4195–4202. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001117)6:22<4195::aid-chem4195>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang W, Jarmillo D, Gooding JJ, Hibbert DB, Zhang R, Willett GD, Fisher KJ. Sub-ppt detection limits for copper ions with Gly-Gly-His modified electrodes. Chem. Comm. 2001;2001:1982–1983. doi: 10.1039/b106730n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. Multicopper Oxidases and Oxygenases. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morgan C, Colombres M, Nunez MT, Inestrosa NC. Structure and function of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004;74:323–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of neural science. New York: McGraw Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vaughan DW, Peters A. The structure of neuritic plaque in cerebral cortex of aged rats. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1981;40:472–487. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aboelella NW, Reynolds AM, Tolman WB. Catching copper in the act. Science. 2004;304:836–837. doi: 10.1126/science.1098301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prigge ST, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Amzel LM. Dioxygen binds end-on to mononuclear copper in a precatalytic enzyme complex. Science. 2004;304:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kayed R, Sokolov Y, Edmonds B, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Hall JE, Glabe CG. Permeabilization of lipid bilayers is a common conformation-dependent activity of soluble amyloid oligomers in protein misfolding diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46363–46366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arispe NH, Pollard HB, Rojas E. Giant multilevel cation channels formed by Alzheimer's disease amyloid β-protein [Aβp-(1–40)] in bilayer membrane. PNAS. 1993;90:10573–10577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quist A, Doudevsli I, Lin H, Azimova R, Ng D, Frangione B, Kagen B, Ghiso J, Lal R. Amyloid ion channels: a common structural link for protein-misfolding disease. PNAS. 2005;102:10427–10432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502066102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dickson DW. Apoptotic mechanisms in Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration: cause or effect. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;111:23–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oddo s, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Meterate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Aβ and synaptic dysfuction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue L-F, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zeiwier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, Wu H. ABAD directly links Aβ to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knauer MF, Soreghan B, Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Glabe CG. Intracellullar accumulation and resistance to degradation of the Alzheimer amyloid A4/β protein. PNAS. 1992;89:7437–7441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Knauer MF, Glabe CG. Preferential adsorption, internalization and resistance to degradation of the major isoform of the Alzheimer's amyloid peptide, Aβ1–42, in differentiated PC Cells. Brain Res. 1997;746:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prohaska JR, Gybina AA. Intracellular copper transport in mammals. J. Nutr. 2004;134:1003–1006. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koehler CM, Beverly KN, Leverich EP. Redox pathways of the mitochondrion. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:813–822. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hiroi MA, Tohru H, Kazuya H, Masashi M, Takao T, Niki E. Regulation of apoptosis by glutathione redox state. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;38:1057–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lora J, Alonso FJ, Segura JA, Lobo C, Marquez J, Mates JM. Antisense glutaminase inhibitions decrease glutathione antioxidant capacity and increase apoptosis. Europ. J. Biochem. 2004;271:4298–4306. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biaglow JE, Lee I, Donahue J, Held K, Mieyal J, Dewhirst M, Tuttle S. Glutathione depletion or radiation treatment alters respiration and induce apoptosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2003;530:153–164. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Biroccio A, Benassi B, Filomeni G, Amodei S, Marchini S, Chiorino G, Rotilio G, Zupi G, Ciriolo MR. Glutathione influences C-Myc-induced apoptosis in M14 human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43763–43770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van den Dobbelsteen DJ, Nobel CSI, Schlegel J, Cotgreave IA, Orrenius S, Slater AFG. Rapid and specific efflux of reduced glutathione during apoptosis induced by anti-Fas/APO-1 antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15420–15427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baloyanis SJ. Mitochondrial alterations in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2006;9:119–126. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aleard AM, Benard G, Augereau O, Malgat M, Talbot JC, Mazat JP, Letellier T, Dachary-Prigent J, Solaini GC, Rossignol R. Gradual alteration of mitochondrial structure and function by β-amyloid: importance of membrane viscosity changes, energy deprivation, reactive oxygen species production, and cytochrome c release. J. Bioeneg. Biomem. 2005;37:207–225. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]