Abstract

Mismatch repair (MMR) strongly enhances cyto- and genotoxicity of several chemotherapeutic agents and environmental carcinogens. DNA-double-strand breaks (DSB) formed after two replication cycles play a major role in MMR-dependent cell death by DNA alkylating drugs. Here we examined DNA damage detection and the mechanisms of the unusually rapid induction of DSB by MMR proteins in response to carcinogenic chromium(VI). We found that MSH2-MSH6 (MutSα) dimer effectively bound DNA probes containing ascorbate-Cr-DNA and cysteine-Cr-DNA crosslinks. Binary Cr-DNA adducts, the most abundant form of Cr-DNA damage, were poor substrates for MSH2-MSH6 and their toxicity in cells was weak and MMR-independent. Although not involved in the initial recognition of Cr-DNA damage, MSH2-MSH3 (MutSβ) complex was essential for the induction of DSB, micronuclei and apoptosis in human cells by chromate. In situ fractionation of Cr-treated cells revealed MSH6 and MSH3 chromatin foci that originated in late S phase and did not require replication of damaged DNA. Formation of MSH3 foci was MSH6- and MLH1-dependent whereas MSH6 foci were unaffected by MSH3 status. DSB production was associated with progression of cells from S into G2 phase and was completely blocked by the DNA synthesis inhibitor aphidicolin. Interestingly, chromosome 3 transfer into MSH3-null HCT116 cells activated an alternative, MSH3-like activity that restored dinucleotide repeat stability and sensitivity to chromate. Thus, sequential recruitment and unprecedented cooperation of MutSα and MutSβ branches of MMR in processing of Cr-DNA crosslinks is the main cause of DSB and chromosomal breakage at low and moderate Cr(VI) doses.

Introduction

The primary function of mismatch repair (MMR) is to correct errors arising during DNA replication (1, 2). Detection of single base mispairs occurs through the binding of the MutSα complex (MSH2-MSH6 heterodimer) (3, 4), which is also capable of recognizing small loops containing 1–3 nucleotide insertion/deletions (4). The less abundant MutSβ heterodimer (MSH2-MSH3) predominantly recognizes insertion/deletion loops greater than 2 nucleotides (3, 4). Following recognition and binding to mispaired DNA, MutSα/β recruits MutLα (MLH1-PMS2 heterodimer), and the MutS-MutL complex activates the excision of up to 1 kb of newly synthesized DNA to remove the mispairs (1, 2). Loss of MMR leads to highly elevated rates of spontaneous mutagenesis and is a cause of microsatellite instability found in 15–20% of human cancers (5). In addition to their role in correction of replication errors, MMR proteins are known to participate in the cytotoxic responses to several chemotherapeutic drugs including SN1-type methylating agents (6, 7), cisplatin (8, 9) and halogenated nucleotides (10–12). The activation of cell death by these drugs involved the initial recognition of modified DNA bases by MutSα and a subsequent recruitment of MutLα. MutSβ has not been found to play any significant role in toxicity of alkylating agents or base analogs (13, 14). MMR-dependent processing of DNA damage leads to a delayed formation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) and these secondary lesions are important for apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and cytogenetic damage (15–17). Direct signaling from DNA damage-bound MMR complexes has been proposed as an alternative model for the induction of cell death (5, 18, 19).

Another chemical that displays a MMR-dependent mechanism of cell death is the potent human carcinogen chromium(VI) (20, 21). Cr(VI) is a procarcinogen activated via reduction to Cr(III) by cellular ascorbate (Asc) and small thiols (22), which results in the formation of weakly mutagenic Cr-DNA adducts and strongly mutagenic reducer-Cr-DNA crosslinks (22–25). The importance of MMR in Cr(VI) carcinogenesis is indicated by a very high frequency (>80%) of microsatellite instability in chromate-induced human lung carcinomas (26, 27), suggested to result from selective outgrowth of resistant cells during chronic exposures to Cr(VI) (20, 28). Mechanistically, MMR appears to induce cell death in response to Cr-DNA damage differently than in the cases of other DNA-damaging agents. The initiation of apoptosis by MMR of Cr-treated cells was preceded by the formation of poorly repaired DSB that were induced almost immediately after Cr(VI) exposure (20, 29). This rapid DSB production is inconsistent with the model of futile MMR cycling in which DSB are not formed until the second S-phase following a generation of single-strand breaks and gaps in the daughter DNA strand after the first S-phase (15–17). Thus, in addition to the importance of mechanistic understanding of high genotoxicity of this widespread carcinogen, Cr(VI) can also serve as a tool to uncover novel functions of MMR proteins in responses to DNA damage.

In this work, we identified ternary Cr-DNA crosslinks as high affinity substrates for recognition by MSH2-MSH6 dimer. Using an in situ fractionation approach and selective knockdowns of MMR proteins, we discovered the formation of MSH6 and MSH3 nuclear foci and a unique requirement for the MutSβ complex in induction of DSB and apoptosis by Cr(VI).

MATERIALS and METHODS

Cells and treatments

Human colon HCT116 (MLH1−/−) and DLD1 (MSH6−/−), lung epithelial H460, and lung fibroblast IMR90 cell lines were purchased from ATCC. HCT116+chr.3 (MLH1+) and DLD1+chr.2 (MSH6+) were gifts from Dr. T. Kunkel. Loading with Asc and measurements of its cellular concentrations by HPLC were performed as previously described (29, 30). Exposures to K2CrO4 [Cr(VI)] were for 3 hr in serum-free medium. For clonogenic experiments, colonies were stained with Giemsa solution and counted 10–14 days later.

Cr-DNA modifications

Cr-DNA adducts were formed according to the previously described conditions (24, 25). Binary Cr-DNA adducts were generated by reacting 2 μg DNA with 0–80 μM CrCl3•6H2O in 25 mM MES buffer (pH 6.0). Standard reaction mixtures for Cr-DNA binding during Cr(VI) reduction contained 2 μg DNA, 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 0–150 μM K2CrO4 and either 1 mM Asc or 2 mM cysteine. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min (CrCl3 and Asc reactions) or 1 hr (cysteine reactions). Unreacted Cr was removed by 2 passages through Bio-Gel P-30 (plasmids) or P-6 (oligos) columns. DNA-bound Cr was measured by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (30).

DNA-protein pulldown assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described (31) with the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) to the lysis buffer. The sense oligo, 5′-GGGAAGCTGCCAGGCCCCAGTGTCAGCCTCCTATGCTC, was modified with a 5′ biotin label. The antisense sequence for the homoduplex contained normal Watson-Crick base pairing and antisense sequence for the heteroduplex probe contained one G/T mispair in the center of the sequence, 5′-GAGCATAGGAGGCTGACATTGGGGCCTGGCAGCTTCCC. Nuclear extracts (100 μg) were preincubated with 0.1 μg of non-biotinylated homoduplex and 5 μg poly DI:DC in 1x DNA binding buffer [12% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2] for 5 min at 4°C. Next, 100 ng biotinylated duplex was added to the reaction for 30 min. Biotin-DNA-protein complexes were captured by incubation with 80 μl streptavidin-agarose beads for 2 hr at 4°C. Beads were washed 4 times with 1 ml of 1x DNA binding buffer, resuspended in 30 μl of 2x SDS loading buffer and bound proteins were released by boiling.

Western blotting

Cells were collected by scraping, washed twice with cold PBS and then resuspended in a lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (20). Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred onto ImmunoBlot PVDF membranes. Primary antibodies for MLH1, MSH2, MSH3 and MSH6 were from PharMingen. Protein bands were visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Plasmid replication in cells

Control and Cr-modified pSP189 plasmids (M. Seidman) were transfected into HCT116 and HCT116+chr.3 and allowed to replicate for 48 hr. The replicated plasmids were isolated by the Mini-prep kit from Qiagen. DNA was ethanol precipitated, dissolved in deionized water, and electroporated into E. coli MBL50 strain. Transformed E. coli cells were plated on minimal agar plates containing 30 μg/ml of ampicillin and 0.5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol to assess the yield of replicated plasmids.

Knockdown experiments

Stable depletion of protein levels was achieved by expression of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) from the pSUPER-RETRO vector. The plasmid was linearized with HindIII and BglII to permit the insertion of the annealed oligonucleotides directed towards the mRNA of interest. The targeting vectors for MSH2, luciferase (29), MLH1 (32) and infection conditions (33) have already been described. MSH6- and MSH3-targeting vectors were constructed using 5′-gatccccggtgatccctctgagaactttcaagagaagttctcagagggatcacctttttggaaa and 5′-gatccccgccagtttgtgaactagaattcaagagattctagttcacaaactggctttttggaaa oligos, respectively. Vector-expressing cells were selected in the presence of 1.5 μg/ml puromycin.

MLH1 complementation

MluI fragment caring MLH1 gene was excised from pCMV-SPORT6 (ATCC) and inserted into the pQCXIN retroviral vector opened with EcoRI. Viral particles were packaged in 293T cells by co-transfection with plasmids encoding VSV-G envelope protein and MoMuLV gag-pol (33). HCT116 cells were infected with pQCXIN-MLH1 and control vectors and then selected with 600 μg/ml G418.

Microsatellite instability assay

Cells were seeded in 60 mm dishes and allowed to attach overnight prior to retroviral infection with the pCXpur/(CA)17/out-of-frame plasmid (gift from Dr. N. Kato) (34). Infected cells were cultured for 7–10 days (3 passages) and then selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin at a density of 1 × 106 cells per 100 mm dish. Mutation frequency was calculated by dividing the number of puromycin resistant colonies per 106 clonable cells.

Microscopy

Micronuclei were scored at 48 hr post-Cr as previously described (29). For confocal immunofluorescence cells were grown on Superfrost Plus slides, washed twice with cold PBS and extracted at 4°C for 10 min in a modified cytoskeleton buffer (33). Slides were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, extracted with 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature and incubated with 2% FBS for 30 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Double labeling was performed by simultaneous incubation of primary antibodies for 2 hr at 37°C. Slides were washed three times with PBS for 5 min followed by incubation with Alexa-Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and Alexa-Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Slides were washed four times with PBS for5 min and mounted with Vectashield hard set mounting medium containing DAPI. Fluorescence images were recorded with a Zeiss Axiovert 100 confocal microscope and analyzed by Phoenix and Metamorph software. Slides were always coded and scored in a blind manner.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

PFGE plugs were prepared using BioRad Mammalian CHEF Genomic Plug Kit at 1.0 × 106 cells/plug. Cells were digested in proteinase K buffer [100 mM EDTA, 1% N-laurylsarcosyl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mg/ml proteinase K] at 20°C for 24 hr and then washed 5 times in a detergent-free wash buffer. PFGE was performed using a 1% gel (Pulsefield Certified Megabase Agarose, BioRad) in 0.5X TBE buffer on a CHEF Mapper XA Pulsed Field Electrophoresis System (Bio-Rad) for 18 h under the following conditions: 120° field angle, 240 s switch time, 4 V/cm, 14°C. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

MSH2-MSH6 dimer recognizes Cr-DNA crosslinks in vitro

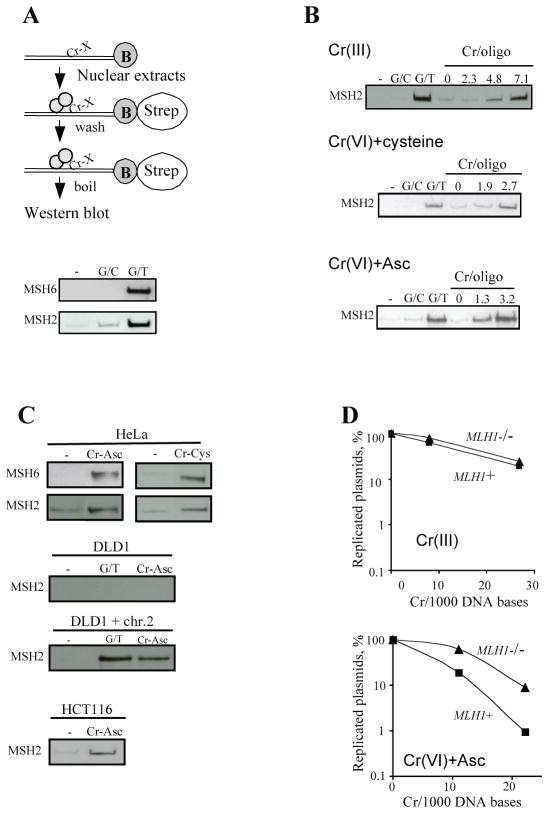

To examine whether MMR proteins are able to recognize Cr-DNA damage, we devised a DNA-protein pulldown assay. Biotinylated oligos were incubated with nuclear extracts, pulled down with streptavidin beads, and bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by immunoblotting. Validation experiments confirmed the ability of biotinylated DNA containing a single G/T mismatch to pull down both MSH2 and MSH6 from HeLa extracts (Fig 1A). Cr-DNA binding does not display apparent base or sequence-specificity leading to a near random distribution of adducts (23, 35). As adjacent bases exert strong effects on the ability of MMR complexes to bind their substrates (19, 36), analysis of randomly-damaged templates offers a benefit of examining multiple sequence contexts. In our initial experiments, we monitored binding of MSH2, a component of both MutSα and MutSβ mismatch-sensing complexes. Oligos containing solely binary Cr-DNA adducts showed reproducible binding of MSH2 but only at a high density of modifications (approx. 7 Cr/oligo) (Fig. 1B). However, DNA probes modified in the presence of Cr(VI)-cysteine displayed a strong binding of MSH2 at 2.7 Cr/oligo. Oligos modified in the reaction of Cr(VI) with its dominant cellular reducer Asc pulled down MSH2 at both 1.3 and 3.2 Cr/probe (Fig. 1B). We have previously determined that Cr(VI)-cysteine reactions generated approximately equal numbers of Cr-DNA adducts and cysteine-Cr-DNA crosslinks (37). Cr(VI)-Asc reactions yielded about 25% Asc-Cr-DNA crosslinks and 75% Cr-DNA adducts (30).

Figure 1. Recognition of Cr-DNA adducts by MMR proteins.

Western blots are representative of 3 independent experiments for each adduct. Data for Cr-DNA adducts are means from 4 determinations. (A) DNA-protein pulldown assay and its validation with HeLa extracts incubated with normal (G/C) or mismatched (G/T) duplexes. (B) Binding of MSH2 from HeLa extracts to oligos containing Cr-DNA adducts [Cr(III) reactions] or mixtures of Cr-DNA adducts and reducer-Cr-DNA crosslinks [Cr(VI)+cysteine or Cr(VI)+ Asc reactions]. (C) Pulldowns of MSH2 and MSH6 proteins using nuclear extracts from HeLa, DLD1 (MSH6−/−), DLD+chr.2 (MSH6+) or HCT116 (MLH1−/−) cells. Labels: untreated (−), treated with Cr(VI) and ascorbate (Cr-Asc), Cr(VI) and cysteine (Cr-Cys), duplex containing a single G:T mispair (G/T). (D) Replication efficiency of Cr-modified pSP189 plasmids in MLH1−/− and MLH1+ cells. Plasmids were replicated in HCT116 (MLH1−/−) and HCT116+chr.3 (MLH1+) cells for 48 hr, and the yield of replicated plasmids was determined by bacterial transformation assay. Cr(III): plasmids were reacted with Cr(III) yielding Cr-DNA adducts; Cr(VI)+Asc: plasmids were modified during reduction of Cr(VI) with Asc, which generated both Cr-DNA adducts and Asc-Cr-DNA crosslinks. Data are means±SD of 4 independent transfections.

We next examined the role of MSH2-MSH6 and MSH2-MSH3 complexes in recognition of Cr-DNA adducts. Oligos modified during Cr(VI) reduction with cysteine or Asc pulled down MSH6 from HeLa nuclear extracts (Fig. 1C). We were unable to detect the presence of MSH3 in HeLa pulldowns (data not shown). To further test a potential involvement of MSH3, we analyzed DNA adduct-binding activity of nuclear extracts from DLD1 (MSH6−) and DLD1+chr.2 (MSH6+) cells. While MSH2 was pulled down by Cr-DNA damage from MSH6+ extracts, there was no MSH2 binding in MSH6− extracts (Fig. 1C). Similarly to detection of base mismatches, recognition of Cr-DNA damage by MutSα was independent of MLH1 as nuclear extracts from MLH1-null HCT116 cells showed normal binding of MSH2 to Cr/Asc-modified DNA probes (Fig. 1C). Since lack of MLH1 makes cells resistant to Cr(VI) cytotoxicity (20, 21), this protein appears to act in the genotoxic responses downstream of MutSα-mediated recognition of Cr-DNA adducts. To test whether the differences in binding by MSH2-MSH6 accurately predict genotoxic responses in cells, we examined replication inhibition by Cr-DNA modifications at levels equivalent to 0.8–2.2 Cr/pulldown oligo. In agreement with MutSα binding affinity, plasmids treated with Cr(VI)+Asc but not with Cr(III) displayed a strong MMR-dependent replication inhibition (Fig. 1D).

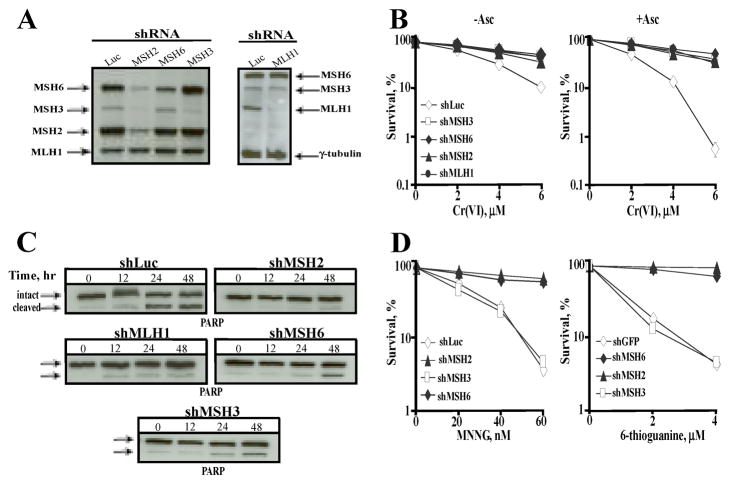

Both MutS dimers are required for the induction of cell death by Cr-DNA damage

To test the importance of MMR complexes in cellular responses to Cr(VI), we created stable knockdowns of different MMR proteins in H460 cells (Fig. 2A). shRNA-mediated depletions of MLH1, MSH3 and MSH6 were highly specific whereas knockdown of MSH2 was also accompanied by decreased stability of its partners MSH3 and MSH6. Surprisingly, loss of MSH3 suppressed clonogenic lethality of Cr(VI) to the same degree as did loss of MSH6, MSH2 or MLH1 (Fig. 2B). The same result was observed in cells supplemented with physiological 1 mM Asc, the most important Cr(VI) reducer in vivo (22) with barely detectable concentrations in H460 (21) and other cultured human cells (29, 30). Potentiating effects of Asc on Cr(VI) toxicity are completely blocked by MMR inactivation (21, 29), which makes preloading of cells with this vitamin a very useful tool for a selective enhancement of the MMR-dependent toxic responses. Silencing of MSH3 or other MMR proteins all inhibited Cr(VI)-induced apoptosis as evidenced by decreased PARP cleavage (Fig. 2C). MSH3 depletion had no effect on clonogenic lethality of two chemicals with MSH6- but not MSH3-dependent toxicity (13, 14), N-methyl-N′-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) and 6-thioguanine (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that the involvement of MSH3 in MMR-activated cell death was specific to Cr-DNA damage. Stable knockdowns of MSH3 and MSH6 in primary lung IMR90 fibroblasts were also equivalent in suppression of all Cr(VI)-induced cytotoxic effects (not shown).

Figure 2. Cytotoxic responses in H460 cells with shRNA-mediated depletion of MMR proteins.

(A) Western blots demonstrating knockdown efficiencies for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or MSH3 by infections with targeted pSUPER-retro vectors. shRNA directed against luciferase (Luc) was used as a control. (B) Clonogenic lethality of Cr(VI) in shRNA expressing H460 cells without (−Asc) and with 1 mM Asc preloading (+Asc). Data area means±SD from 3 clonogenic experiments with 3 dishes/dose. (C) Western blots for intact and cleaved PARP in cellular extracts collected at different times following exposure to Cr(VI) in cells. Cells were preloaded with 1 mM Asc and exposed to 10 μM Cr(VI). (D) Clonogenic survival of H460 cells treated with MNNG (in the presence of 10 μM O6-benzylguanine) or 6-thioguanine. Data are means±SD from two clonogenic experiments with triplicate dishes/dose

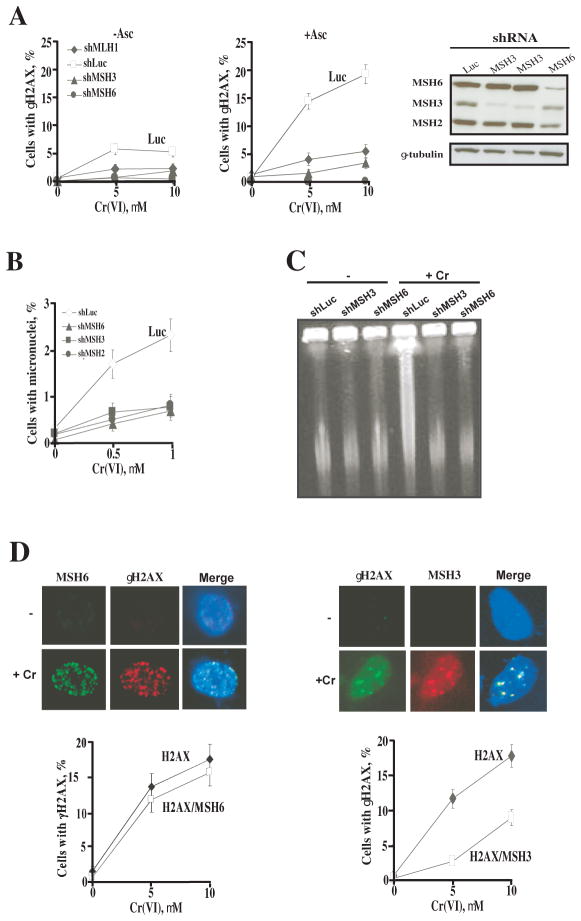

Both MSH6 and MSH3 are involved in DSB formation

The inhibition of all forms of cytotoxicity by silencing of MSH3 or MSH6 suggested that both proteins acted very early in toxic processing of Cr-DNA damage. Therefore, we examined the role of MSH6 and MSH3 in the generation of a DSB-specific marker γH2AX foci (38) that appear early after Cr-DNA damage and precede the activation of apoptotic responses (20, 29). We found that knockdowns of MSH3, MSH6 or MLH1 all abrogated the formation of γH2AX foci in Cr(VI)-treated IMR90 cells (Fig. 3A). As expected, supplementation of IMR90 cells with 1 mM Asc strongly enhanced the production of γH2AX foci by Cr(VI) but silencing of MSH3 or MSH6 eliminated the induction of this DSB marker. Knockdown of MSH3 or MSH6 also completely suppressed the formation of micronuclei by 0.5 and 1 μM Cr(VI) (Fig. 3B), indicating that processing of Cr-DNA damage by MutS dimers was responsible for chromosomal breakage by doses below the current US-EPA water standard of 100 ppb (1.92 μM) chromium. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis further confirmed that both MSH6 and MSH3 were required for DSB induction by Cr(VI) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Induction of DSB and nuclear foci of MSH3 and MSH6 in primary IMR90 cells.

(A) Frequency of γH2AX foci-containing IMR90 cells at 6 hr post-Cr exposure. (−Asc, no Asc loading; +Asc, 1 mM Asc supplementation prior to Cr treatments). (B) Inhibition of micronuclei formation by depletion of MSH2, MSH3 and MSH6. IMR90 cells were loaded with 1 mM Asc, treated with Cr(VI) for 3 hr and the frequency of micronuclei-containing cells was scored 48 hr later. Means±SD for 3 slides with >1000 cells/slide scored. (C) Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of DNA from IMR90 cells collected at 6 hr after exposure to 10 μM Cr(VI). Cells were preloaded with 1 mM Asc prior to Cr(VI) treatments. (D) Representative confocal images and frequencies of colocalization of MSH6 and MSH3 foci with DSB-associated foci of γH2AX in IMR90 cells. Asc-supplemented IMR90 cells were treated with 10 μM Cr(VI) for 3 hr and processed for immunostaining at 6 hr post-Cr exposure. H2AX – overall frequency of γH2AX foci-positive cells, H2AX/MSH6 – frequency of cells containing both γH2AX and MSH3 foci, H2AX/MSH3 – frequency of cells containing both γH2AX and MSH3 foci. Cells with ≥5 foci/cell were defined as positive. Data are means±SD for 3 slides with >100 cells/slide counted.

To investigate whether MMR proteins were present at the sites of DNA breaks, we examined the colocalization of MSH3 and MSH6 with γH2AX foci. After testing several different extraction conditions, we found that permeabilization in the CSK buffer prior to paraformaldehyde fixation was effective in removal of nucleoplasmic MMR proteins and it also revealed the formation of MSH3 and MSH6 foci in Cr(VI)-treated but not control IMR90 cells (Fig. 3D). Approximately 30–40% of γH2AX foci-containing cells showed colocalization with MSH3 foci. The frequency of γH2AX foci-positive cells displaying colocalization with MSH6 foci averaged 85–90%. We also found a high degree of colocalizaion of MSH6 foci with 53BP1 foci (not shown), another marker of DSB (39). The colocalization of MSH3 and MSH6 to DSB foci further supports a causal role of both proteins in breakage of Cr-adducted DNA.

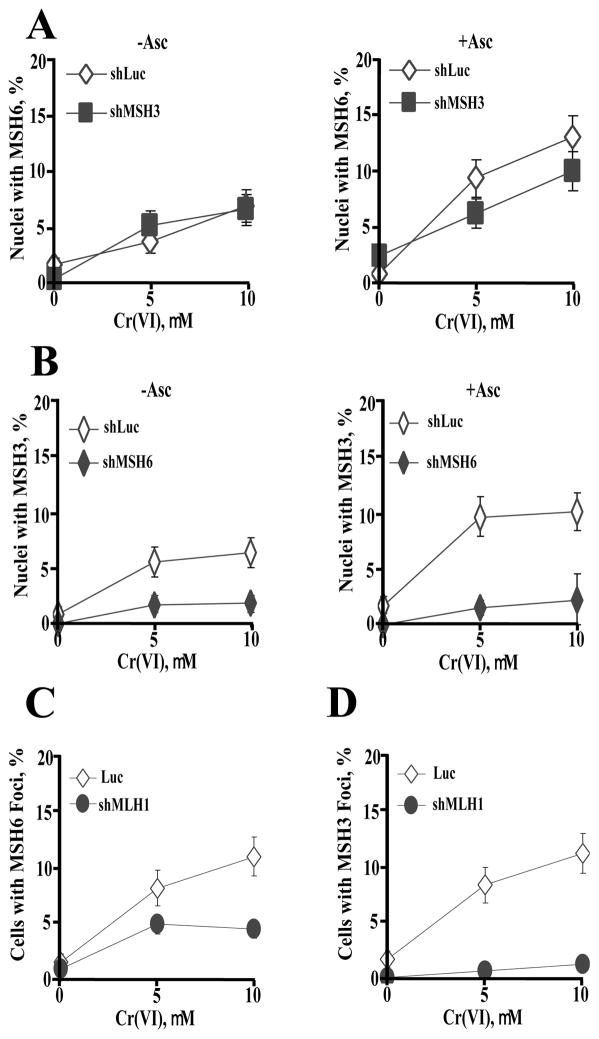

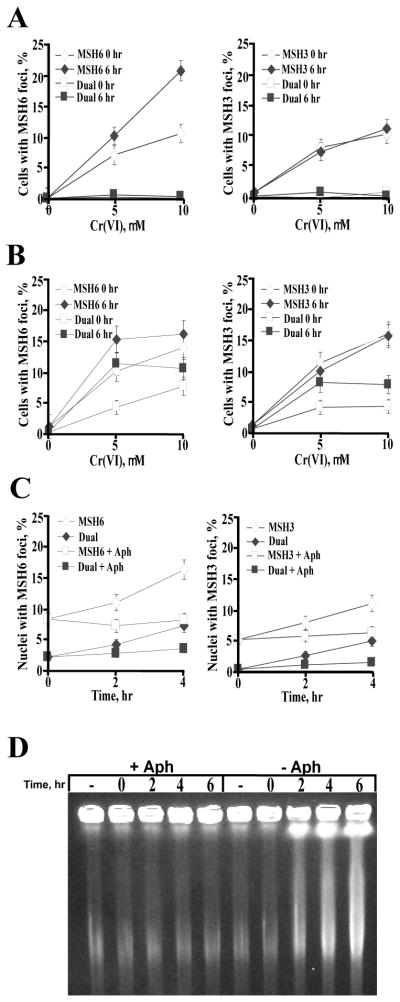

Dependence of MSH3 and MSH6 foci on other MMR proteins

Consistent with its lack of participation in recognition of Cr-DNA damage by MutSα in pulldown experiments, MSH3 depletion had no significant effect on the formation of MSH6 foci in Cr-treated IMR90 cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, MSH6 was absolutely required for the production of MSH3 foci in Cr(VI)-treated cells (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that MutSα complex is involved in the initial detection of Cr-DNA damage in cells and MSH3-containing MutSβ complex is recruited later. The majority of MSH6 foci-containing cells also had MSH3 foci and vice versa. For example, 80.9% of MSH6 foci+ cells contained MSH3 foci and 90.4% of MSH3 foci+ cells had MSH6 foci at 6 hr after 10 μM Cr exposure of 1 mM Asc-preloaded IMR90 cells. MLH1 depletion in primary IMR90 cells resulted in a moderately lower frequency of MSH6 foci-containing cells (Fig. 4C) and completely abrogated MSH3 foci (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Effect of MMR proteins on the induction of MSH3 and MSH6 foci by Cr-DNA damage in IMR90 cells.

(A) Frequency of MSH6 foci-containing cells expressing nonspecific (Luc) or MSH3-targeting shRNA. Cells were analyzed at 6 hr post-Cr exposure (−Asc, no Asc loading; +Asc, 1 mM Asc supplementation prior to Cr treatments). Data are means ±SD for 3 slides with >100 cells counted per slide. (B) Frequency of MSH3 foci-containing cells expressing nonspecific (Luc) or MSH6-targeting shRNA. Data are means ±SD for 3 slides with >100 cells counted per slide. (C) Formation of MSH6 and (D) MSH3 foci in MLH1-depleted cells (1 mM Asc-supplemented cells, means ±SD for 3 slides).

Cell cycle specificity and effect of replication on MSH3 and MSH6 foci

Since the majority of Cr-induced DSB are found in G2 cells (20, 29), we asked whether the formation of MMR foci also exhibits cell cycle specificity. S-phase cells were labeled by BrdU incorporation while G2 cells were identified by cyclin B1 staining. Our detergent extraction procedure retained cytoplasmic cyclin B1 due to the stability of its binding to microtubules (40). Essentially no cells displayed both BrdU incorporation and MSH6/MSH3 foci either immediately or 6 hr after Cr(VI) exposure (Fig. 5A). A large percentage of cells containing MSH6 foci and MSH3 foci also expressed the G2 phase marker cyclin B1 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Cell cycle specificity of MSH3 and MSH6 foci formation in primary IMR90 cells.

Cells were preloaded with 1 mM Asc prior to Cr(VI) treatments. Data are means±SD for at least 3 slides with >100 cells scored per slide. (A) Absence of MSH6 and MSH3 foci in BrdU-labeled cells at 0 and 6 hr post Cr exposure. MSH6 (MSH3) - total frequency of cells with MSH6 (MSH3) foci, dual – BrdU-labeled cells with MSH6 or MSH3 foci. (B) Frequency of MSH6 and MSH3 foci-containing cells expressing cyclin B1. MSH6 (MSH3) – total number of cells with MSH6 (MSH3) foci, dual – cells with foci and cyclin B1 expression. (C) Effect of replication inhibition on the formation of MSH6 and MSH3 foci in Cr-treated cells. Cells were preloaded with 1 mM Asc and then treated with Cr(VI) in the presence of 1 μM aphidicolin (added 15 min before Cr). Following Cr exposure, aphidicolin was either removed or added again (+Aph). MSH6/MSH3 – total frequency of foci-containing cells, dual – foci-containing cells with cyclin B1 expression. (D) Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of DNA from IMR90 cells collected at different times after exposure to 10 μM Cr(VI). Cells were preloaded with 1 mM Asc and exposed to Cr(VI) in the presence (+Aph) or absence (−Aph) aphidicolin. In +Aph samples, aphidicolin was also present during post-Cr incubations.

The role of replication in the formation of MMR foci was examined in two series of experiments with the DNA polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin. In the first set, there was no replication of Cr-adducted DNA at any time due the presence of aphidicolin during and after Cr(VI) treatments. In the second set, replication was only inhibited during Cr exposure and then the aphidicolin block was removed. We found that even in the absence of any replication, Cr-DNA damage resulted in a significant formation of MSH6 and MSH3 foci immediately after Cr(VI) exposure and their levels remained constant during 4 hr post-Cr incubations (Fig. 5C). Release of the replication block after Cr exposure resulted in a progressively higher number of MSH6/3 foci-containing cells with time and a parallel increase in the number of MMR foci/cyclin B1-double positive cells (Fig. 5C). Unlike MSH6/3 foci, replication arrest by aphidicolin completely blocked the formation of DSB (Fig. 5D), pointing to the importance of the completion of DNA replication and progression from S into G2 for DNA breakage by MMR.

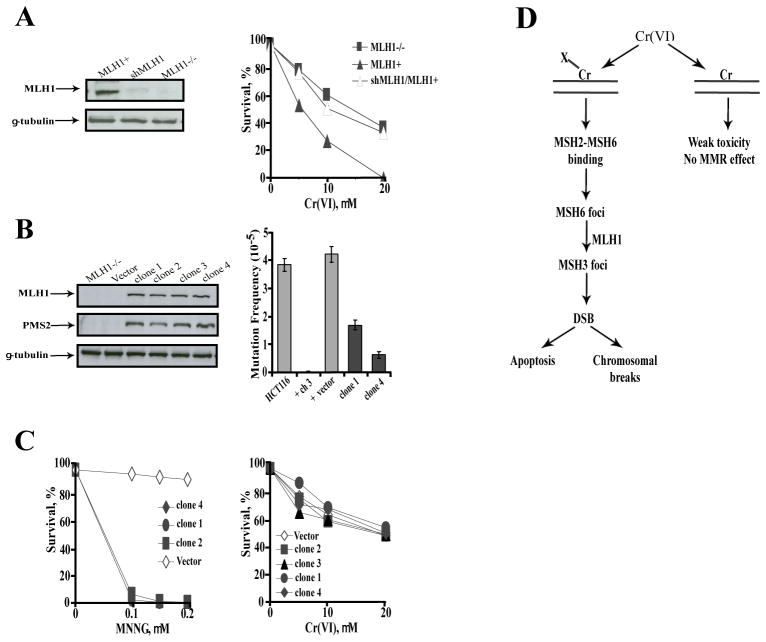

Different responses in HCT116 cells expressing MLH1 via vector or chromosome 3 complementation

We have previously found that MLH1-null HCT116 cells had much greater resistance to Cr(VI) and lower DSB induction than their counterparts complemented with MLH1 via chromosome 3 transfer (20). However, HCT116 cells have also been reported to lack functional MSH3 due to a −1 truncation mutation in the (A)8 repeat of exon 7 (41). This raised the important question of how chromosome 3 transfer increased sensitivity of HCT116 cells to Cr(VI) since MSH3 was clearly required for Cr-induced cytotoxicity and DSB production in IMR90 and H460 cells. Formation and repair of Cr-DNA adducts were identical in HCT116 and HCT116+chr.3 cells (20), excluding the possibility that chromosome complementation altered Cr(VI) metabolism or persistence of adducts. We sequenced exon 7 of MSH3 gene from our HCT116 lines and confirmed the presence of the previously reported truncation mutation in the (A)8 repeat. MLH1 silencing in HCT116+chr.3 cells restored their resistance to Cr(VI) (Fig. 6A), confirming MMR-dependence of cell death in Cr-treated HCT116+chr.3 cells. Since chromosome 3 introduced more genes than just MLH1, we infected HCT116 cells with the pQCXIN-MLH1 retroviral vector and selected several clones that expressed MLH1 at the same level as HCT116+chr.3 cells. As expected, expression of functional MLH1 in HCT116 cells was accompanied by stabilization of its partner PMS2 (Fig. 6B). While all MLH1-expressing clones were highly sensitive to MNNG, a chemical that induces MMR-dependent toxicity without MSH3 involvement (14), they showed no sensitization to Cr(VI) (Fig. 6C). Since repair of 2 nt-long insertion/deletion loops is primarily dependent on MSH2-MSH3 dimer (41,42), MLH1-complemented HCT116 cells containing only MutSα complex would be expected to display a weak suppression of frameshift mutagenesis at dinucleotide repeats. We found that two tested clones complemented with pQCXIN-MLH1 showed only modest 2.5- and 6.7-fold reductions in frameshift mutagenesis at CA repeats relative to the vector control (Fig. 6B, right panel). In contrast, chromosome 3 transfer completely restored CA repeat stability, with the frequency of puromycin-resistant clones decreasing 190-fold from 38.2×10−6 for HCT116 to to 0.2×10−6 HCT116+chr.3 cells. Thus, HCT116+chr.3 cells appeared to acquire the ability to compensate for the loss of functional MSH3, as evidenced by their sensitivity to Cr(VI) and highly efficient repair of slippage errors in dinucleotide sequences. Introduction of one extra chromosome into diploid human cells has been found to induce large alterations in the transcriptome of the trisomic and other cellular chromosomes (43) and this could have created either a new loop-processing activity or somehow enhanced affinity of MutSα to the substrates that are typically recognized by MutSβ. Despite the involvement of the alternative MSH3-like activity, HCT116+chr.3 cells (20) faithfully recapitulated toxic responses of H460 and primary human cells to Cr-DNA damage (21, 29).

Figure 6. Differential toxicity of Cr(VI) in HCT116 cells complemented with MLH1 gene via chromosome 3 transfer or retroviral infections.

Results are means±SD from 2–3 independent experiments. Where not seen, error bars were smaller than symbols. (A) Western blot demonstrating MLH1 knockdown by shRNA (left panel) and clonogenic survival of HCT116 (MLH1−/−), HCT116+chr.3 with nonspecific (MLH1+) and MLH1-targeteting shRNA (shMLH1/MLH1+) cells treated with Cr(VI) (right panel). (B) Expression of MLH1 and PMS2 in HCT116 clones generated by infection with pQCXIN-MLH1 (left panel) and frequency of frameshift mutagenesis at pCXpur/(CA)17 out-of-frame vector stably integrated in HCT116 cell lines (right panel). The number of cells with the restored reading frame was determined by scoring colonies surviving in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin. Total of 5–7×107 clonable cells were screened for puromycin resistance. Similar mutation frequencies were obtained when selection was performed with 5 μg/ml puromycin. (C) Clonogenic survival of control and MLH1-complemented HCT116 cells treated with MNNG or Cr(VI). (D) A model describing MMR-dependent genotoxicity of Cr(VI) involving recognition and sequential processing of ascorbate/cysteine-Cr-DNA crosslinks (X-Cr-DNA) by MMR proteins into toxic DSB. Binary Cr-DNA adducts are poor substrates for MSH2-MSH6 binding and their toxicity is weak and MMR-independent.

DISCUSSION

Pulldown experiments with Cr-modified probes and formation of MSH6 foci in Cr-treated cells in the absence of DNA replication indicated that MSH2-MSH6 dimer acted as a sensor of Cr-DNA damage. Binding of MutSα complex to Cr-adducted DNA was independent on MSH3 and MLH1, demonstrating that the initial recognition of Cr-DNA damage was very similar to the detection of single base mismatches (1, 2). Reduction of Cr(VI) by Asc or cysteine created a combination of Cr-DNA adducts and Asc/cysteine-Cr-DNA crosslinks and led to strong binding of MSH2-MSH6 to oligos containing on average 3 Cr/oligo. No significant binding was detected using probes with 1–3 binary Cr-DNA adducts. These results indicated that Cr-DNA crosslinks were high affinity substrates for MMR proteins, which was further confirmed in the plasmid replication experiments. The ability of cellular Asc to enhance cytotoxicity and DSB formation by Cr(VI) strictly in a MMR-dependent manner (21, 29) was consistent with a strong MMR-activating potential of Asc-Cr-DNA crosslinks. Since Cr-DNA adducts and crosslinks showed no differences in the sites of DNA attachment (22, 23), higher affinity of MutSα for crosslinks could be associated with their increased bulkiness. Although binding of MSH2 and MSH6 in amounts similar to the samples with a single G/T mismatch required up to 3 Cr/oligo for Cr(VI)-cysteine or Cr(VI)-Asc reactions, the affinity of MutSα complex for Cr-DNA crosslinks was probably as good as for the mismatch. First, because Asc/Cr(VI)-modified oligos contained 75% inactive Cr-DNA adducts, G/T mismatch-equivalent levels of MSH2-MSH6 binding were reached with 0.75 crosslinks/probe. Second, since Cr-DNA binding was random, only about 1/3 of all Cr-DNA modifications were expected to be within the central area of our 38-bp long oligo, which provided a sufficient sequence length for binding of MMR proteins (44).

MMR-dependent DSB formation by Sn1-methylating agents involves the production of persistent single-strand gaps after the first S-phase and a subsequent collapse of replication forks in the second S-phase (17, 45). The unique aspect of MMR-induced DSB in Cr-damaged DNA was an almost immediate appearance of DSB after short Cr exposures. DSB production in Cr-treated cells also showed unprecedented requirement for MSH3, a component of the MutSβ complex principally responsible for recognition and repair of DNA loops with ≥2 nucleotides (1,2). MSH2-MSH3 dimer acted downstream of MSH2-MSH6 because MSH6 depletion eliminated MSH3 foci while MSH3 silencing had no effect on the levels of MSH6 foci. Formation of MSH3 foci was also blocked by MLH1 knockdown, indicating that the recruitment of MSH3 occurs after the completion of a series of MutSα-initiated MMR events (Fig. 6D). What signal or DNA structure activates MSH3 is currently unclear but the formation of hairpins or loops in single-stranded regions containing repetitive sequences could represent one possibility. Alternatively, MSH3 could be recruited by recombination intermediates formed at the sites of single-stranded gaps generated by MutSα-MutLα activity. MSH2-MSH3 dimer is known to participate in rejection of imperfectly matched sequences during homologous recombination through activation of endonucleases (46). In the case of Cr-damaged DNA, MSH3-dependent recruitment of endonucleases could lead to the inappropriate cleavage of recombination products and formation of toxic DSB.

A combination of our findings with phase-specific markers and replication-arrested cells indicates that the formation of Cr-DNA damage-processing MMR complexes occurs in late S phase. Normal initial formation of MSH6 foci in replication-arrested cells and then parallel increases in the total number of MSH6 foci and MSH6 foci/cyclin B1 double positive cells after removal of replication block are indicative of a relatively rapid progression of MSH6 foci-containing cells into G2 phase. MMR-promoted DSB foci were predominantly found in G2 cells but inhibition of DNA synthesis by aphidicolin completely blocked DSB induction. Thus, accumulation of MSH6/3 foci and DSB after Cr(VI) exposure appears to require not replication but the progression of cells through late S into early G2 phase which creates the permissible conditions for cleavage of both DNA strands. S-phase cells display higher thresholds for checkpoint activation relative to G2 cells (47) and increased sensitivity to DNA damage-induced signaling in the late S phase could be one contributing factor to the formation of MSH6 foci at this stage of cell cycle. Another important event occurring in late S phase is the induction of exonuclease-1 expression (48), which is a critical MMR component that has recently been found to be necessary for cell death by the MMR-dependent toxicant 6-thioguanine (49).

Recent risk assessment studies have shown that even Cr(VI) exposures not exceeding a new, 10-times lower permissible limit could result in as many as 45 additional cancer deaths per 1000 workers (50). These risks are striking considering relatively modest amounts of inhaled Cr(VI) and high rates of Cr-DNA damage removal by nucleotide excision repair (30). A rapid activation of both MMR branches apparently outcompetes beneficial repair processes and is the principal cause of chromosomal breaks at low chromate doses. Drugs producing DNA adducts with similarly rapid MMR processing into toxic DSB should offer greater clinical efficacy due to less dependence on repair deficiency of cancer cells and no need for persistence of adducts until second S phase, which is a requirement for the currently used Sn1 alkylating agents (17).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants ES008786 and ES012915.

References

- 1.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–23. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modrich P. Mechanisms in eukaryotic mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30305–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600022200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acharya S, Wilson T, Gradia S, et al. hMSH2 forms specific mispair-binding complexes with hMSH3 and hMSH6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13629–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genschel J, Littman SJ, Drummond JT, Modrich P. Isolation of MutSb from human cells and comparison of the mismatch repair specificities of MutSb and MutSa. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19895–901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishel R. Signaling mismatch repair in cancer. Nat Med. 1999;5:1239–41. doi: 10.1038/15191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickman MJ, Samson LD. Role of DNA mismatch repair and p53 in signaling induction of apoptosis by alkylating agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cejka P, Stojic L, Mojas N, et al. Methylation-induced G(2)/M arrest requires a full complement of the mismatch repair protein hMLH1. Embo J. 2003;22:2245–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aebi S, Kurdi-Haidar B, Gordon R, et al. Loss of DNA mismatch repair in acquired resistance to cisplatin. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3087–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink D, Zheng H, Nebel S, et al. In vitro and in vivo resistance to cisplatin in cells that have lost DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1841–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swann PF, Waters TR, Moulton DC, et al. Role of postreplicative DNA mismatch repair in the cytotoxic action of thioguanine. Science. 1996;273:1109–11. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan T, Berry SE, Desai AB, Kinsella TJ. DNA mismatch repair (MMR) mediates 6-thioguanine genotoxicity by introducing single-strand breaks to signal a G2-M arrest in MMR-proficient RKO cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2327–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers M, Wagner MW, Mazurek A, et al. DNA mismatch repair-dependent response to fluoropyrimidine-generated damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5516–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinz JM, Meuth M. MSH3 deficiency is not sufficient for a mutator phenotype in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:215–20. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wind N, Dekker M, Claij N, et al. HNPCC-like cancer predisposition in mice through simultaneous loss of Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair protein functions. Nat Genet. 1999;23:359–62. doi: 10.1038/15544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bignami M, O’Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Unmasking a killer: DNA O(6)-methylguanine and the cytotoxicity of methylating agents. Mutat Res. 2000;462:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.York SJ, Modrich P. Mismatch repair-dependent iterative excision at irreparable O6-methylguanine lesions in human nuclear extracts. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22674–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603667200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mojas N, Lopes M, Jiricny J. Mismatch repair-dependent processing of methylation damage gives rise to persistent single-stranded gaps in newly replicated DNA. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3342–55. doi: 10.1101/gad.455407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin DP, Wang Y, Scherer SJ, et al. An Msh2 point mutation uncouples DNA mismatch repair and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:517–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshioka K, Yoshioka Y, Hsieh P. ATR kinase activation mediated by MutSalpha and MutLalpha in response to cytotoxic O6-methylguanine adducts. Mol Cell. 2006;22:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson-Roth E, Reynolds M, Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Mismatch repair proteins are activators of toxic responses to chromium-DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3596–07. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3596-3607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds M, Zhitkovich A. Cellular vitamin C increases chromate toxicity via a death program requiring mismatch repair but not p53. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1613–20. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhitkovich A. Importance of chromium-DNA adducts in mutagenicity and toxicity of chromium(VI) Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:3–11. doi: 10.1021/tx049774+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voitkun V, Zhitkovich A, Costa M. Cr(III)-mediated crosslinks of glutathione or amino acids to the DNA phosphate backbone are mutagenic in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2024–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhitkovich A, Song Y, Quievryn G, Voitkun V. Non-oxidative mechanisms are responsible for the induction of mutagenesis by reduction of Cr(VI) with cysteine: role of ternary DNA adducts in Cr(III)-dependent mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2001;40:549–60. doi: 10.1021/bi0015459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quievryn G, Peterson E, Messer J, Zhitkovich A. Genotoxicity and mutagenicity of chromium(VI)/ascorbate-generated DNA adducts in human and bacterial cells. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1062–70. doi: 10.1021/bi0271547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose T, Kondo K, Takahashi Y, et al. Frequent microsatellite instability in lung cancer from chromate-exposed workers. Mol Carcinog. 2002;33:172–80. doi: 10.1002/mc.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi Y, Kondo K, Hirose T, et al. Microsatellite instability and protein expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene, hMLH1, of lung cancer in chromate-exposed workers. Mol Carcinog. 2005;42:150–8. doi: 10.1002/mc.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhitkovich A, Peterson-Roth E, Reynolds M. Killing of chromium-damaged cells by mismatch repair and its relevance to carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1050–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds M, Stoddard L, Bespalov I, Zhitkovich A. Ascorbate acts as a highly potent inducer of chromate mutagenesis and clastogenesis: linkage to DNA breaks in G2 phase by mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:465–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quievryn G, Messer J, Zhitkovich A. Carcinogenic chromium(VI) induces cross-linking of vitamin C to DNA in vitro and in human lung A549 cells. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3156–67. doi: 10.1021/bi011942z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Y, Lin FT, Lin WC. ATM-mediated stabilization of hMutL DNA mismatch repair proteins augments p53 activation during DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6430–44. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6430-6444.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds M, Peterson E, Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Human nucleotide excision repair efficiently removes chromium-DNA phosphate adducts and protects cells against chromate toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30419–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naganuma A, Dansako H, Nakamura T, Nozaki A, Kato N. Promotion of microsatellite instability by hepatitis C virus core protein in human non-neoplastic hepatocyte cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1307–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhitkovich A, Voitkun V, Costa M. Formation of the amino acid-DNA complexes by hexavalent and trivalent chromium in vitro: importance of trivalent chromium and the phosphate group. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7275–82. doi: 10.1021/bi960147w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman PD, Wang H, Lawrence CW, et al. Binding of MutS mismatch repair protein to DNA containing UV photoproducts, “mismatched” opposite Watson--Crick and novel nucleotides, in different DNA sequence contexts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:983–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhitkovich A, Shrager S, Messer J. Reductive metabolism of Cr(VI) by cysteine leads to the formation of binary and ternary Cr--DNA adducts in the absence of oxidative DNA damage. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:1114–24. doi: 10.1021/tx0001169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie A, Hartlerode A, Stucki M, et al. Distinct roles of chromatin-associated proteins MDC1 and 53BP1 in mammalian double-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2007;28:1045–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ookata K, Hisanaga S, Bulinski JC, et al. Cyclin B interaction with microtubule-associated protein 4 (MAP4) targets p34cdc2 kinase to microtubules and is a potential regulator of M-phase microtubule dynamics. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:849–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ku JL, Yoon KA, Kim DY, Park JG. Mutations in hMSH6 alone are not sufficient to cause the microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1724–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edelmann W, Yang K, Umar A, et al. Mutation in the mismatch repair gene Msh6 causes cancer susceptibility. Cell. 1997;91:467–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Upender MB, Habermann JK, McShane LM, et al. Chromosome transfer induced aneuploidy results in complex dysregulation of the cellular transcriptome in immortalized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6941–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warren JJ, Pohlhaus TJ, Changela A, et al. Structure of the human MutSalpha DNA lesion recognition complex. Mol Cell. 2007;26:579–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stojic L, Mojas N, Cejka P, et al. Mismatch repair-dependent G2 checkpoint induced by low doses of SN1 type methylating agents requires the ATR kinase. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1331–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.294404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans E, Alani E. Roles for mismatch repair factors in regulating genetic recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7839–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7839-7844.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimada K, Pasero P, Gasser SM. ORC and the intra-S-phase checkpoint: a threshold regulates Rad53p activation in S phase. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3236–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.239802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaetzlein S, Kodandaramireddy NR, Ju Z, et al. Exonuclease-1 deletion impairs DNA damage signaling and prolongs lifespan of telomere-dysfunctional mice. Cell. 2007;130:863–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Department of Labor. Occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium. Final rule Fed Regist. 2006;71:10099–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]