Abstract

This paper presents the results of the assessment of the intramolecular residue-residue contact predictions submitted to CASP9. The methodology for the assessment does not differ from that used in previous CASPs, with two basic evaluation measures being the precision in recognizing contacts and the difference between the distribution of distances in the subset of predicted contact pairs versus all pairs of residues in the structure. The emphasis is placed on the prediction of long-range contacts (i.e. contacts between residues separated by at least twenty-four residues along sequence) in target proteins that cannot be easily modeled by homology. Although there is considerable activity in the field, the current analysis reports no discernable progress since CASP8.

Keywords: CASP, intramolecular contacts, residue-residue contact prediction, protein structure modeling

INTRODUCTION

Interactions among protein residues are crucial in stabilizing the tertiary structure1,2 and knowing them can be of invaluable help in modeling of protein structure. Prediction of contact maps of proteins – even in the simplified form of a binary matrix - can help both free modeling and hard template-based modeling methods. Several algorithms for deriving an approximate structure of a protein from its contact map have been developed3–7, reaching different levels of accuracy. Clearly, the application of contact maps to structure prediction requires that at least a fraction of contacts is identified with high accuracy; the exact number depends on the difficulty of the problem (FM/TBM), protein length, and distribution of contacts along the sequence, among others. Skolnick and coworkers, for example, state that their algorithm is able to successfully fold a small protein using on average one contact for every seven residues7. Other authors report that the tertiary structure of a protein can be modeled with an average RMSD lower than 5.0 Å provided that at least 25% of contacts are correct6. Even if the correctly predicted contacts are too few or too inaccurate for generating a structure, they may still be used for selecting a better template or a model from among alternative ones or to narrow the search space of possible conformations8–11.

Several rather successful three-dimensional structure prediction methods and model quality assessment methods are already taking advantage of contact prediction tools in their pipelines12,13. For example, I-TASSER, one of the most successful structure prediction servers in recent CASPs14,15, has been recently upgraded by adding an ab-initio contact prediction module, which significantly improved its performance and increased quality of the resulting models on hard targets by 4.6% on the average16. In some cases quality of I-TASSER models improved by as much as 30%, resulting in de-facto conversion of essentially “non-foldable” targets into “foldable ones”.

Various approaches have been developed to predict contacts and they can be roughly subdivided into three broad categories:

Methods using homologous proteins with known structures17–20. These are clearly very reliable, but their usefulness is limited to cases where templates can be identified. They are especially helpful for effective combining information derived from several templates, when these are available.

Methods relying on machine learning and mathematical modeling algorithms - such as Hidden Markov models21,22, neural networks22–26, support vector machines27–29, genetic algorithms30, graph theory31, and other techniques32 - to recognize contacts from features identified in protein structures. These methods can obviously be applied to virtually any target.

Methods exploiting evolutionary information. They are based on the concept of correlated mutations33–36, stating that similar patterns of mutations correspond to similar contacts. Some methods37,38 combine this approach with machine learning techniques.

Since contact prediction category was introduced in CASP in 199639, the number of methods has been steadily increasing. Discussions within the community in the first few years of the experiment led to the development of a standard procedure for the assessment of predictions, which has remained stable in the last three CASPs40–42. This enabled us to carry out the evaluation in an automatic fashion. We would like to use this occasion to remind interested readers of the existence of a discussion forum (http://www.forcasp.org/) where alternative evaluation methods can be proposed and discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Contact definition and targets

We use the intramolecular contact definition as accepted in previous CASPs40–42. A pair of residues is considered in contact if the distance between their Cβ atoms (Cα in case of Gly) is lower than 8.0 Å. We distinguish three types of contacts, depending on the number of amino acids separating the residues along the sequence: (i) long range contacts (separation ≥ 24); (ii) medium range contacts (12 ≤ separation ≤ 23) and (iii) short range contacts (6 ≤ separation ≤ 11). Contacts between residues separated by less than 6 residues are usually associated with the protein secondary structure and are not considered here. The most valuable in structure prediction are the long range contacts and here we concentrate on this type of contacts.

Even though contact predictions were submitted for the whole targets, we performed the assessment on a domain level, according to the definitions agreed on by the assessors43. Similarly to previous CASPs, targets for residue contact prediction were limited to the free modeling (FM) and template-based modeling/free modeling (TBM/FM) domains, since in the case of higher homology targets contacts can easily be derived from templates. One domain in the FM category (T0537-D2) was excluded from assessment because of its very short length (31 residues). In the end, evaluation was performed on the 28 “difficult” target domains (25 FM and 3 TBM/FM). A more unbiased view of the success of de novo contact prediction methods would require to limit the analysis only to non-template based “new fold” targets, however the paucity of the latter (just four in the current edition of the experiment43), does not allow to draw any statistically sound conclusion from their analysis.

Participating groups

Twenty-seven groups, including eighteen servers, submitted residue-residue contact predictions in CASP9. Although these numbers are higher than in the last CASP42 (22 and 14, respectively), according to the submitted abstracts44, only very few prediction groups used new methods. The remaining groups used modified versions of methods already tested in previous CASPs. A detailed list of the best publicly available RR servers participating in CASP is provided in Table I. As it can be appreciated from the short description of the servers given in the Table, all of them are based on some machine learning technique.

Table I.

A short description of best ten publicly available servers participating in CASP9.

| Server name and URL address (* standalone software free to download) | Description |

|---|---|

| MULTICOM-CLUSTER28 http://casp.rnet.missouri.edu/download/svmcon1.0.tar.gz (*) |

Method is based on support vector machines. The input data include secondary structure, solvent accessibility and sequence profile for residues of a 9 by 9 residue windows. |

| PROC_S3; PROC_S1 http://www.abl.ku.edu/Pred_CMAP/ |

Ab-initio prediction methods are based on Random Forest models – a machine-learning technique using over 1,000 sequence-related features. |

| DISTILL24 http://dbstill.ucd.ie/distill/ |

The method is based on 2D-recursive neural networks. |

| SAM-T0845 http://compbio.soe.ucsc.edu/SAM_T08/ SAM-T06 http://compbio.soe.ucsc.edu/SAM_T06/ |

Ab-initio contact prediction servers using neural networks and information about correlated mutations in the multiple sequence alignments, which are built using Hidden Markov models. |

| MULTICOM-CONSTRUCT26; MULTICOM-REFINE 26 http://casp.rnet.missouri.edu/download/nncon1.0.tar.gz (*) |

Both methods are based on recursive neural networks. MULTICOM-REFINE has an incorporated module to predict contacts in beta-sheets. |

| SVMSEQ27 http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/SVMSEQ_CASP9 |

Machine-learning-based method for ab initio contact prediction trained on a variety of sequence-derived features, which include both local features and in-between segment features. The vector of features has over 700 components for short, medium and long range contacts. |

| FRAGHMMENT21 http://bioinfo8.limbo.ifm.liu.se/FragHMMent/ |

The method is based on Hidden Markov models trained on alignments of local descriptors of protein structure. |

Prediction format and contact lists

The format for submitting predictions was the same as in previous CASPs40–42: predictors were asked to submit a list of pairs of residues, together with the corresponding probabilities of the two residues being in contact.

Different predictors submitted different numbers of contacts per target. To compare them, we first sorted the contacts according to their predicted probabilities and then generated lists of L/5 and L/10 best predicted contacts40–42, where L is the length of the domain sequence. We also used a list containing only the five top predictions (top-5 list) to evaluate cases where predictors submitted only a very small number of contacts. The assessment was performed on all three lists, whenever possible.

The number of contact lists evaluated for each group is summarized in Figure 1. Two groups (G179 and G201) are not included due to insufficient number of submitted contact predictions.

Figure 1.

Number of targets evaluated for each group using the L/10, L/5 and Top-5 lists of contacts.

Evaluation criteria and scores

Since CASP6, predictions in the RR category are evaluated using two measures: Acc and Xd 40–42. Accuracy (Acc), is defined as the percentage of correctly predicted contacts with respect to the total number of contacts in the evaluated list:

where TP and FP are the numbers of correctly and incorrectly predicted contacts, respectively*. The Xd score is defined as:

where PiP is the fraction of predicted contacts in bin i, and Pia - the fraction of all residue pairs in bin i. The 15 bins include ranges of distances from 0 to 4 Å, 4 Å to 8 Å, 8 Å to 12 Å, etc. This score estimates the deviation of the distribution of distances in the list of contacts from the distribution of distances in all pairs of residues in the protein40,41. The higher the Xd, the higher the precision of the predicted contacts with respect to randomly selected pairs. Xd is close to zero for randomly selected pairs.

Prediction groups are ranked according to the Z-scores computed from the distributions of the Acc and Xd values for each target domain. The final per-target Z-scores are re-calculated from the “cleaned” distributions, where only the groups that scored above the level of the mean minus two standard deviations in the original all-group distribution are considered. This elimination of the poorest per-target scores from the final calculations is done to remove possible bias in scores due to trivial errors in the submission/algorithm. The per-domain Z-scores for Acc and Xd are added, and then averaged over N domains attempted by a prediction group for the resulting cumulative score expressed as:

We also compared the results of each pair of prediction groups “head-to-head”, by computing the fraction of common targets for which one group outperformed the other according to both the Acc and Xd scores. The statistical significance of the differences in performance between any two groups was assessed using a paired Student’s t-test on both the Acc and Xd scores.

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows the average Acc score for each of the targets. The accuracy for long range contacts in the L/5 lists ranges from 1% to about 35%, indicating that targets presented very different levels of difficulty for RR prediction. In particular, two targets (T0529-D1 and T0629-D2) seem particularly hard, with an average accuracy of 1% and 2%, respectively. A similar analysis using the Xd score (see Figure S1, Supplementary Material) confirms this conclusion. Domain T0629-D2 has very few native long range contacts, while T0529-D1 is a completely novel fold.

Figure 2.

Average value of the accuracy (Acc) obtained by the participating groups for each of the targets using the L/10, L/5 and Top-5 lists of contacts.

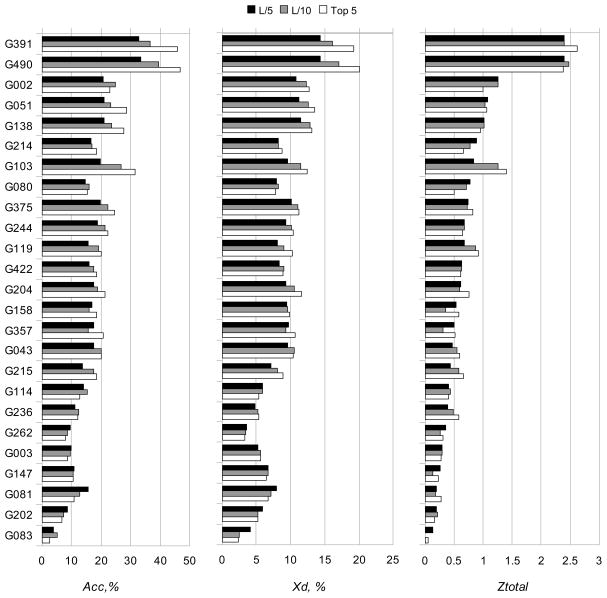

The results of the per group assessment are summarized in Figure 3 and Tables II and III. Figure 3 shows the values of Acc, Xd and Ztotal for all groups averaged over all predictions containing a sufficient number of contacts.

Figure 3.

Acc (a), Xd (b) and Z-score (c) values for the participating groups.

Table II.

Results of the Student t-tests on the Acc scores calculated for the L/5 sets of contacts. For each pair of groups, the numbers under the diagonal show the p-values, and those above - the numbers of common domains evaluated. Shaded cells correspond to the statistically indistinguishable groups at the 0.05 significance level.

| G391 | G490 | G002 | G051 | G138 | G214 | G103 | G080 | G375 | G244 | G119 | G422 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G391 | - | 26 | 25 | 27 | 23 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 27 |

| G490 | 0.449 | - | 25 | 27 | 24 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| G002 | 0.006 | 0.006 | - | 25 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 |

| G051 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.468 | - | 24 | 28 | 28 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 28 |

| G138 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.443 | 0.261 | - | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| G214 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.072 | 0.258 | - | 28 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 28 |

| G103 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.478 | 0.315 | 0.469 | 0.171 | - | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 28 |

| G080 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.026 | 0.055 | 0.112 | 0.285 | 0.112 | - | 25 | 25 | 26 | 26 |

| G375 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.438 | 0.189 | 0.44 | 0.282 | 0.377 | 0.131 | - | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| G244 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.313 | 0.094 | 0.299 | 0.398 | 0.23 | 0.223 | 0.322 | - | 25 | 25 |

| G119 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.085 | 0.161 | 0.371 | 0.151 | 0.161 | 0.187 | 0.293 | - | 26 |

| G422 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.415 | 0.042 | 0.355 | 0.055 | 0.164 | 0.451 | - |

Table III.

Head-to-head comparison of participating groups. Cells show the percentages of cases in which the Acc score of the group designated with the row label is higher than that of the group designated with the column label. Cases where the accuracy is the same were not counted and therefore the percentages at the opposite sides of the diagonal do not necessarily add up to 100%. Computations were performed on the L/5 lists of contacts.

| group II | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G391 | G490 | G002 | G051 | G138 | G214 | G103 | G080 | G375 | G244 | G119 | G422 | ||

| group I | G391 | - | 19.2% | 68.0% | 70.4% | 65.2% | 74.1% | 51.9% | 80.0% | 66.7% | 70.8% | 80.0% | 74.1% |

| G490 | 26.9% | - | 64.0% | 63.0% | 62.5% | 77.8% | 63.0% | 80.8% | 64.0% | 68.0% | 80.8% | 70.4% | |

| G002 | 24.0% | 32.0% | - | 48.0% | 47.8% | 48.0% | 44.0% | 72.0% | 33.3% | 45.8% | 64.0% | 48.0% | |

| G051 | 22.2% | 25.9% | 40.0% | - | 45.8% | 57.1% | 50.0% | 65.4% | 52.0% | 56.0% | 65.4% | 60.7% | |

| G138 | 30.4% | 29.2% | 39.1% | 33.3% | - | 58.3% | 58.3% | 66.7% | 62.5% | 45.8% | 58.3% | 62.5% | |

| G214 | 14.8% | 18.5% | 48.0% | 28.6% | 33.3% | - | 39.3% | 57.7% | 48.0% | 40.0% | 57.7% | 46.4% | |

| G103 | 33.3% | 29.6% | 40.0% | 35.7% | 41.7% | 57.1% | - | 57.7% | 40.0% | 44.0% | 57.7% | 50.0% | |

| G080 | 12.0% | 11.5% | 24.0% | 26.9% | 29.2% | 30.8% | 38.5% | - | 48.0% | 28.0% | 26.9% | 42.3% | |

| G375 | 16.7% | 20.0% | 54.2% | 36.0% | 37.5% | 52.0% | 32.0% | 52.0% | - | 36.0% | 52.0% | 48.0% | |

| G244 | 16.7% | 20.0% | 45.8% | 36.0% | 41.7% | 48.0% | 36.0% | 64.0% | 40.0% | - | 64.0% | 60.0% | |

| G119 | 12.0% | 15.4% | 28.0% | 19.2% | 33.3% | 34.6% | 34.6% | 46.2% | 44.0% | 24.0% | - | 50.0% | |

| G422 | 22.2% | 22.2% | 28.0% | 17.9% | 25.0% | 46.4% | 25.0% | 42.3% | 32.0% | 32.0% | 46.2% | - | |

In general, there is a tendency for the accuracy of almost all groups to increase as the number of evaluated contacts decreases (from L/5 to L/10 to Top 5), demonstrating that methods are reasonably good in correctly ranking their predictions.

The best results, regardless of the considered list of contacts, were obtained by groups “Smeg_CCP” (G391) and “Multicom” (G490). These groups submitted predictions for almost complete set of targets (27 targets out of 28) and their results are statistically better than those of other groups but indistinguishable between themselves according to the paired t-tests (Table II). This conclusion is confirmed by the head-to-head comparison of group scores over commonly predicted targets (Table III). The methods used by groups G391 and G490 are very similar and rely on the 3D structures submitted by CASP9 servers for deriving distance constraints through a consensus strategy. The remaining groups submitted predictions of significantly lower quality (Figure 3), and the ten groups, which are ranked below the top two are statistically indistinguishable from each other (Table II). The results based on the Xd scores are very similar and presented in the Supplementary Material (Tables S1 and S2).

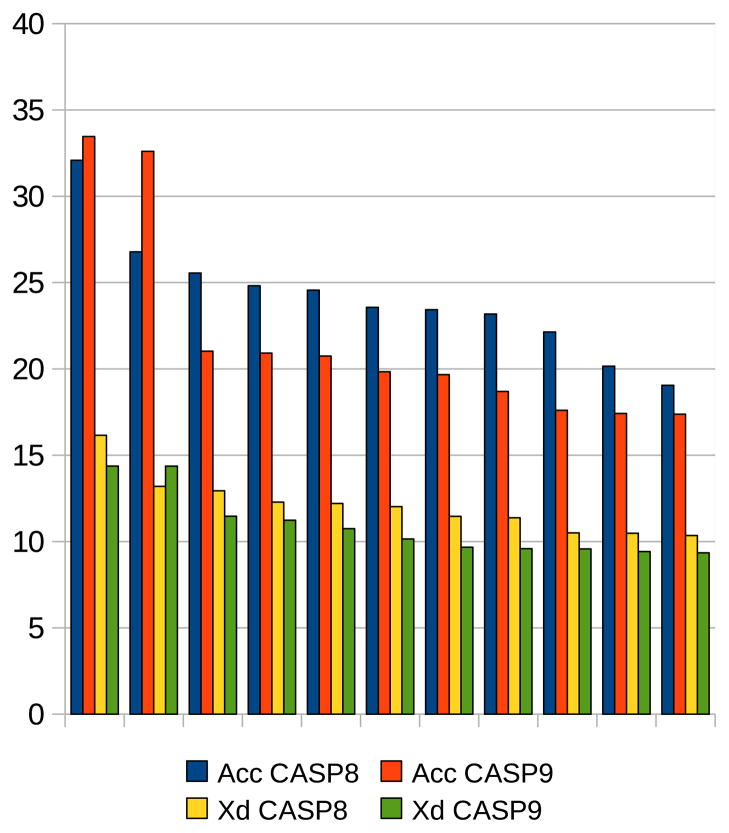

Comparison with previous CASPs

Only 12 targets were used for the RR assessment in CASP8, compared with the 28 assessed here. The average Acc and Xd values obtained by RR groups in this CASP are 16.8% and 8.5%, respectively. When the two very difficult domains T0629-D2 and T0529-D1 are not considered, the corresponding numbers increase to 18.0% and 9.2%. For comparison, in CASP842 the average Acc and Xd values were 21.1% and 10.1%, respectively. This would suggest that either the CASP9 methods are slightly worse than those in CASP8, or that the targets for this experiment are more difficult to handle. We believe that the drop in scores is due to a higher difficulty of the CASP9 targets, as discussed in another paper in this issue46. This reasoning is further corroborated by the fact that many of the same methods were tested both in CASP8 and CASP9, providing a direct means of comparison.

Figure 4 shows the results of comparison of the best twelve performing groups in CASP9 and CASP8 according to both the Acc and Xd scores. Also in this case, predictions submitted to CASP9 seem to be relatively less accurate than those submitted in the previous experiment.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the results obtained by the best twelve predictors in CASP8 and CASP9. The twelve groups were selected based on the Acc score.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the RR predictions submitted in CASP9 suggests that improvement in the methods (if any) was more than offset by the increased target difficulty. It is also somewhat disappointing to observe that the best results are obtained by leveraging the ability to predict tertiary structures and to derive contact predictions from them, rather than the opposite. Since the main reason for predicting contacts is to aid in the prediction of structure and not the other way around, the emergence and relative success of techniques relying on the already predicted structures, seems to be of limited importance. Perhaps we should limit assessment to only the targets where model building remains highly unreliable, although few of these are available in any single CASP. Or we should proceed as now, noting the deficiencies in the currently most successful techniques, and hoping for the emergence of methods capable of making an independent contribution to modeling of structure.

In any case, the CASP RR contact prediction data collected over more than a decade, and the developed standard assessment procedure, provide a useful reference for predictors to evaluate novel ideas and algorithms. We hope that the still growing community in this area will soon make important advancements, significantly influencing ab initio structure prediction in general.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Library of Medicine (NIH/NLM) – grant LM007085 to KF and by KAUST Award KUK-I1-012-43 to AT.

Abbreviations

- 3D

three-dimensional

- RR

residue-residue contact

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

Footnotes

In descriptive statistics, this definition of Acc is usually called positive predictive value (PPV) or precision. We retained the name “accuracy” here for consistency with the previous CASP assessments.

References

- 1.Niggemann M, Steipe B. Exploring local and non-local interactions for protein stability by structural motif engineering. J Mol Biol. 2000;296(1):181–195. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gromiha MM, Selvaraj S. Inter-residue interactions in protein folding and stability. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;86(2):235–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vendruscolo M, Kussell E, Domany E. Recovery of protein structure from contact maps. Fold Des. 1997;2(5):295–306. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(97)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohr J, Bohr H, Brunak S, Cotterill RM, Fredholm H, Lautrup B, Petersen SB. Protein structures from distance inequalities. J Mol Biol. 1993;231(3):861–869. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollastri G, Vullo A, Frasconi P, Baldi P. Modular DAG-RNN architectures for assembling coarse protein structures. J Comput Biol. 2006;13(3):631–650. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassura M, Margara L, Di Lena P, Medri F, Fariselli P, Casadio R. FT-COMAR: fault tolerant three-dimensional structure reconstruction from protein contact maps. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(10):1313–1315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skolnick J, Kolinski A, Ortiz AR. MONSSTER: a method for folding globular proteins with a small number of distance restraints. J Mol Biol. 1997;265(2):217–241. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eyal E, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Sobolev V, Pietrokovski S. A pair-to-pair amino acids substitution matrix and its applications for protein structure prediction. Proteins. 2007;67(1):142–153. doi: 10.1002/prot.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller CS, Eisenberg D. Using inferred residue contacts to distinguish between correct and incorrect protein models. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(14):1575–1582. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tress ML, Valencia A. Predicted residue-residue contacts can help the scoring of 3D models. Proteins. 2010;78(8):1980–1991. doi: 10.1002/prot.22714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gniewek P, Leelananda SP, Kolinski A, Jernigan RL, Kloczkowski A. Multibody coarse-grained potentials for native structure recognition and quality assessment of protein models. Proteins. 2011;79(6):1923–1929. doi: 10.1002/prot.23015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng J, Wang Z, Tegge AN, Eickholt J. Prediction of global and local quality of CASP8 models by MULTICOM series. Proteins. 2009;77 (Suppl 9):181–184. doi: 10.1002/prot.22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y. I-TASSER: fully automated protein structure prediction in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77 (Suppl 9):100–113. doi: 10.1002/prot.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y. Template-based modeling and free modeling by I-TASSER in CASP7. Proteins. 2007;69 (Suppl 8):108–117. doi: 10.1002/prot.21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu S, Szilagyi A, Zhang Y. Improving protein structure prediction using multiple sequence-based contact predictions. Structure. 2011;19(7) doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.05.004. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234(3):779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shao Y, Bystroff C. Predicting interresidue contacts using templates and pathways. Proteins. 2003;53 (Suppl 6):497–502. doi: 10.1002/prot.10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Kolinski A, Skolnick J. TOUCHSTONE II: a new approach to ab initio protein structure prediction. Biophys J. 2003;85(2):1145–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misura KM, Chivian D, Rohl CA, Kim DE, Baker D. Physically realistic homology models built with ROSETTA can be more accurate than their templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(14):5361–5366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509355103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjorkholm P, Daniluk P, Kryshtafovych A, Fidelis K, Andersson R, Hvidsten TR. Using multi-data hidden Markov models trained on local neighborhoods of protein structure to predict residue-residue contacts. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(10):1264–1270. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollastri G, Baldi P. Prediction of contact maps by GIOHMMs and recurrent neural networks using lateral propagation from all four cardinal corners. Bioinformatics. 2002;18 (Suppl 1):S62–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fariselli P, Casadio R. A neural network based predictor of residue contacts in proteins. Protein Eng. 1999;12(1):15–21. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vullo A, Walsh I, Pollastri G. A two-stage approach for improved prediction of residue contact maps. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, Huang DS, Zhao XM, Li X. Predicting contact map using radial basis function neural network with conformational energy function. Int J Bioinform Res Appl. 2008;4(2):123–136. doi: 10.1504/IJBRA.2008.01834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tegge AN, Wang Z, Eickholt J, Cheng J. NNcon: improved protein contact map prediction using 2D-recursive neural networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W515–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Zhang Y. A comprehensive assessment of sequence-based and template-based methods for protein contact prediction. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(7):924–931. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng J, Baldi P. Improved residue contact prediction using support vector machines and a large feature set. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P, Han K, Li X, Huang DS. Predicting key long-range interaction sites by B-factors. Protein Pept Lett. 2008;15(5):478–483. doi: 10.2174/092986608784567573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen P, Li J. Prediction of protein long-range contacts using an ensemble of genetic algorithm classifiers with sequence profile centers. BMC Struct Biol. 2010;10 (Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stout M, Bacardit J, Dirst JD, Smith RE, Krasnogor N. Prediction of topological contacts in proteins using learning classifier systems. Soft Computing. 2009;13:245–258. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stout M, Bacardit J, Hirst JD, Krasnogor N. Prediction of recursive convex hull class assignments for protein residues. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(7):916–923. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gobel U, Sander C, Schneider R, Valencia A. Correlated mutations and residue contacts in proteins. Proteins. 1994;18(4):309–317. doi: 10.1002/prot.340180402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halperin I, Wolfson H, Nussinov R. Correlated mutations: advances and limitations. A study on fusion proteins and on the Cohesin-Dockerin families. Proteins. 2006;63(4):832–845. doi: 10.1002/prot.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kundrotas PJ, Alexov EG. Predicting residue contacts using pragmatic correlated mutations method: reducing the false positives. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:503. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton N, Burrage K, Ragan MA, Huber T. Protein contact prediction using patterns of correlation. Proteins. 2004;56(4):679–684. doi: 10.1002/prot.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fariselli P, Olmea O, Valencia A, Casadio R. Prediction of contact maps with neural networks and correlated mutations. Protein Eng. 2001;14(11):835–843. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.11.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shackelford G, Karplus K. Contact prediction using mutual information and neural nets. Proteins. 2007;69 (Suppl 8):159–164. doi: 10.1002/prot.21791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesk AM. CASP2: report on ab initio predictions. Proteins. 1997;(Suppl 1):151–166. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(1997)1+<151::aid-prot20>3.3.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grana O, Baker D, MacCallum RM, Meiler J, Punta M, Rost B, Tress ML, Valencia A. CASP6 assessment of contact prediction. Proteins. 2005;61 (Suppl 7):214–224. doi: 10.1002/prot.20739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izarzugaza JM, Grana O, Tress ML, Valencia A, Clarke ND. Assessment of intramolecular contact predictions for CASP7. Proteins. 2007;69 (Suppl 8):152–158. doi: 10.1002/prot.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ezkurdia I, Grana O, Izarzugaza JM, Tress ML. Assessment of domain boundary predictions and the prediction of intramolecular contacts in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77 (Suppl 9):196–209. doi: 10.1002/prot.22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinch L, Shi S, Cheng H, Cong Q, Pei J, Schwede T, Grishin N. CASP9 target classification. Proteins. 2011 doi: 10.1002/prot.23190. Current. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.http://predictioncenter.org/casp9/doc/Abstracts.pdf

- 45.Karplus K. SAM-T08, HMM-based protein structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W492–497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kryshtafovych A, Fidelis K, Moult J. CASP9 results compared to those of previous CASP experiments. Proteins. 2011 doi: 10.1002/prot.23182. Current. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.