The article examines the level of involvement of oncologists in bereavement rituals after a patient dies.

Keywords: Oncologists, Bereavement, Death, Spirituality, Religion

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Examine the level of involvement of oncologists in bereavement rituals after a patient dies, in order to improve the effectiveness of oncologists and other caregivers in helping families cope with their loss.

Analyze the reasons physicians do or do not participate in rituals involving direct contact or indirect contact with the bereaved families of their patients.

Develop formal programs for the care team to provide continuing support involving direct contact and indirect contact with bereaved families.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Purpose.

We sought to determine the level of involvement of oncologists in bereavement rituals after a patient dies.

Subjects and Methods.

Members of the Israeli Society for Clinical Oncology and Radiation Therapy (ISCORT) were surveyed. The survey instrument consisted of questions regarding participation in bereavement rituals for patients in general and those with whom the oncologist had a special bond. Oncologists were queried as to the reasons for nonparticipation in bereavement rituals.

Results.

Nearly 70% of the ISCORT membership (126 of 182) completed the survey tool. Respondents included radiation, surgical, and medical oncologists. In general, oncologists rarely participated in bereavement rituals that involved direct contact with families such as funerals and visitations. Twenty-eight percent of physicians at least occasionally participated in rituals involving direct contact whereas 45% had indirect contact (e.g., letter of condolence) with the family on an occasional basis. There was significantly greater involvement in bereavement rituals when oncologists developed a special bond with the patient. In a stepwise linear regression model, the only factor significantly associated with greater participation in bereavement rituals was self-perceived spirituality in those claiming not to be religious. The major reasons offered for nonparticipation were time constraints, need to maintain appropriate boundaries between physicians and patients, and fear of burnout.

Conclusion.

Although many oncologists participate at least occasionally in some sort of bereavement ritual, a significant proportion of oncologists are not involved in these practices at all.

Introduction

The role of oncologists in providing comprehensive cancer care continues to expand. In 1998, the American Society of Clinical Oncology published a position statement stressing the need for a greater focus on palliative care that consists of a variety of interventions that ameliorate the suffering of the patient and family [1, 2]. There is also a greater appreciation of the fact that cancer care does not terminate at the time of the patient's death, and that there is a responsibility on the part of the oncologist to continue to interact with the families of deceased patients [3]. Such interactions may include bereavement counseling, continued informal communication with the family, and participation in formal bereavement rituals.

From a different perspective, oncologists often develop protracted and even intense relationships with patients and their families. The cessation of the therapeutic association that occurs when the patient expires has a significant impact on both family members and the physician [4–19]. Both studies and vignettes from patients and physicians detail the void that exists after a patient dies [17, 20–23]. The family often feels abandoned by the health care system in general and by their physicians specifically [20, 24–26]. Physicians experience grief and a sense of loss, especially for patients with whom they developed a special bond. The nature of the patient–physician relationship and the boundaries associated with this relationship often make it difficult for doctors to find the appropriate channels for mourning their loss [5, 15, 16, 27–32]. Several studies have shown that many physicians have little interaction with families after patients expire, and the interactions that do exist are usually in the form of “non-face-to-face contact” such as letters or phone communication [8, 32, 33].

The necessity and appropriateness of physician involvement in bereavement practices have been discussed primarily in the context of qualitative reporting [11, 34–36]. Some authors have focused on the wishes of physicians for closure whereas others examined the topic from the perspective of the needs of the family [37, 38]. There is less information available on the extent of physician participation in bereavement practices and the type of interaction that an individual physician has with family members [5, 8, 16, 33, 39].

The current study was undertaken to define the frequency with which oncologists participate in bereavement rituals. A secondary objective was to identify factors that prompt some oncologists to forego such participation.

Methods and Materials

Survey Design

The Israeli Society for Clinical Oncology and Radiation Therapy (ISCORT) is the umbrella professional organization that represents cancer specialists in Israel and includes all oncology specialties except for pediatrics. Members of ISCORT were invited to participate in the current survey via e-mail. Pursuant to the initial invitation, two additional prompts were sent to the electronic mailing list of the society. Members were also given the opportunity to respond at the two semiannual meetings conducted by ISCORT during the period of study. Anonymity of results was assured. A research assistant, working independently of the investigators, collated the data to preserve anonymity and verify that there was no duplication of respondents. Based on the nature of the study and the study group, review of the protocol by the Tel Aviv Medical Center Institutional Review Board and ISCORT was waived, consistent with the policies of both institutions.

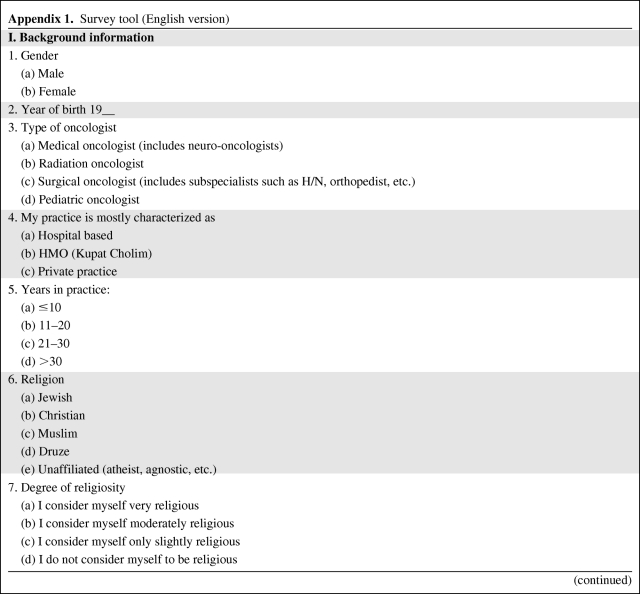

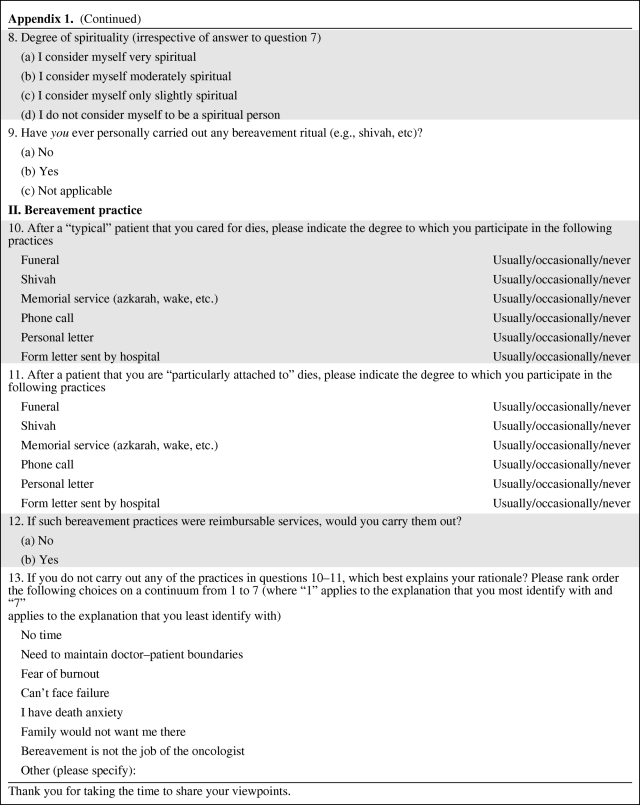

A survey tool (Appendix 1) was developed to query members regarding their participation in a wide range of bereavement rituals. The survey was divided into four sections: demographic characteristics of the study population, involvement in bereavement practices, religiosity and spirituality, and reasons for nonparticipation in bereavement practices. Demographic information collected included physician age, gender, subspecialty practice, years in practice, and religious affiliation. With regard to bereavement practices and reasons for nonparticipation, the survey was similar to that of Chau et al. [33] except that specific bereavement practices common to the region were included (e.g., Jewish shivah, Islamic A'za). The questionnaire also assessed other bereavement practices, such as telephone calls and correspondence (i.e., e-mail, postal mail). Those surveyed were asked whether their bereavement practices would change if they had developed a close relationship with a patient prior to death. The term close relationship was termed in the survey item as becoming “particularly attached” to a patient (Appendix 1) without further characterization. Respondents were also asked to rank order the reasons that they tended to not carry out bereavement practices. As part of a pilot study, the survey was administered to selected individuals to determine if there were ambiguities in any of the test items.

Individuals were asked about religiosity and spirituality. Because there is little consensus on how to define or measure religiosity and spirituality in an objective manner, it was decided to rely on self-perception regarding an individual's religiosity and spirituality [40]. Each respondent was asked to rate their religiosity or spirituality on a four-point Likert scale, with 1 being the response if the individual considered him/herself very spiritual or religious and 4 the response if the individual considered him/herself to be nonreligious or nonspiritual (Appendix 1). Religion and spirituality were queried as separate items because these terms are not coterminous and were investigated as separate variables [41, 42].

Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet and then transferred to a SAS statistical program. For purposes of the analysis, bereavement practices were categorized into three groups: (a) practices including funerals, visitations, and memorial services in which there is a physical presence of the physician (face to face); (b) bereavement practices done indirectly either by phone or mail (indirect); and (c) no participation in a bereavement practice. The association between demographic as well as professional factors and the type of bereavement practice carried out was performed with a χ2 test. McNemar's test of symmetry was used to compare oncologists' bereavement practices in relation to patients in general and to patients with whom they had a special bond. Linear stepwise regression was used to determine the relationship between specific variables and participation in bereavement practices. The model was developed by first doing a bivariate analysis relating demographic and physician characteristics to participation in bereavement practices. Subsequently, a stepwise linear regression was done in three steps, including forced entry, forward selection, and backward elimination. Based on the above analysis, five variables were evaluated in the final model. SAS for Windows, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Bereavement Practices of Oncologists

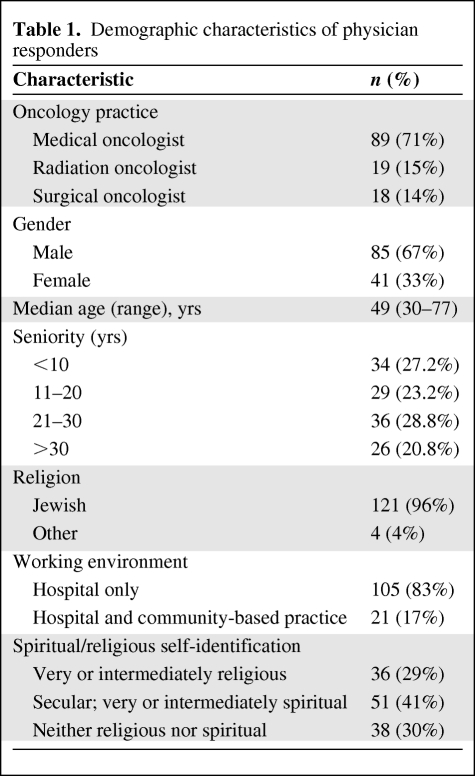

Nearly 70% of the ISCORT membership (126 of 182) completed the survey. The demographic and religious/spiritual background data of the respondents are displayed in Table 1. The male–female ratio was 2.1 and over two thirds of the respondents were medical oncologists. Most of the respondents were hospital-based oncologists, with only 17% of the subjects also practicing in a community setting.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of physician responders

The survey instrument did not provide a definition of either “religiosity” or “spirituality.” Rather, physicians were asked to characterize their religious and spiritual attitudes themselves. In response, 41% claimed to be spiritual and nonreligious whereas 30% asserted that they were neither religious nor spiritual. Of the 36 physicians claiming to be very religious or intermediately religious, 34 (94%) also stated that they were either very or intermediately spiritual. For purposes of the analysis, people who identified themselves as religious, even if minimally not spiritual, were considered as a single group (religious) whereas those who claimed to be very or intermediately spiritual but minimally or not religious were considered as a separate group (spiritual/nonreligious).

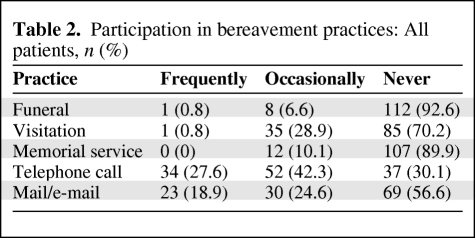

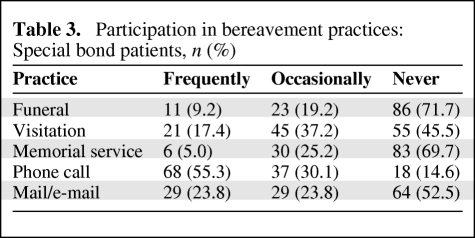

The extent of physician participation in bereavement practices is shown for patients in general (Table 2) and separately for patients with whom physicians had a special bond (Table 3). As a frequent practice, physicians rarely participated in bereavement rituals that involved direct physical contact with families, such as funerals and visitations. However, on an occasional basis, physicians would have face-to-face contact, usually in the format of a visitation. When it came to patients with whom the physician had developed a special bond, there was a higher rate of participation in all forms of bereavement practice.

Table 2.

Participation in bereavement practices: All patients, n (%)

Table 3.

Participation in bereavement practices: Special bond patients, n (%)

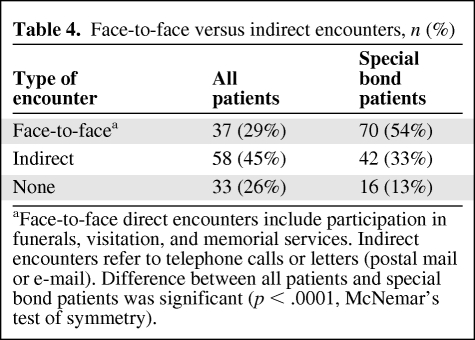

As described above, bereavement practices were divided into face-to-face interactions and indirect interactions. Table 4 shows oncologists' participation (frequent or occasional) in bereavement practices for patients in general and for patients with whom there was a special bond in terms of face-to-face and indirect interactions. Notably, although 74% of physicians either frequently or occasionally participated in a bereavement ritual, 26% stated that they never participated in any sort of bereavement ritual for patients in general and 13% gave the same response even for patients with whom they had a special bond. When broken down into type of bereavement practice, nearly 30% of oncologists participated in a face-to-face encounter at least on an occasional basis, whereas 45% had indirect contact with families at least occasionally. The frequencies of face-to-face and indirect interactions were significantly greater when there was a special bond (p < .0001, McNemar's test of symmetry).

Table 4.

Face-to-face versus indirect encounters, n (%)

aFace-to-face direct encounters include participation in funerals, visitation, and memorial services. Indirect encounters refer to telephone calls or letters (postal mail or e-mail). Difference between all patients and special bond patients was significant (p < .0001, McNemar's test of symmetry).

Factors Associated with Face-to-Face Bereavement Practices

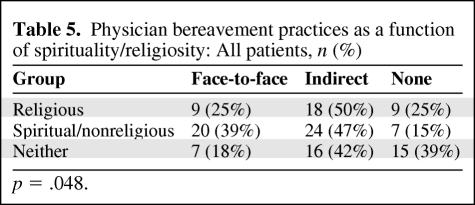

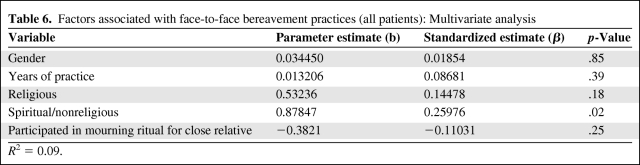

On univariate analysis, demographic and religious/spiritual factors associated with participation versus nonparticipation in bereavement rituals were evaluated (Table 5). The only factor found to have an association with greater participation in bereavement rituals for patients in general was spirituality among those who identified themselves as nonreligious, when compared with those who were either religious or nonreligious but not spiritual (p = .048). For patients with special bonds, religious/spiritual factors were not associated with greater participation in bereavement rituals. The impact of religiosity and spirituality was also evaluated using a stepwise linear regression model (Table 6), and here too there was a significant association between nonreligious spirituality and face-to-face interactions with bereaved family members that persisted even after adjusting for other demographic variables (p =.02). It should be noted that the predictive power of the model was relatively low (R2 = .09), indicating that demographic factors as a whole (including gender, religious background, and duration of practice) were not particularly informative in predicting whether a specific oncologist would participate in a bereavement ritual. What this means is that other variables most likely related to either the inherent personality or working conditions of an individual physician motivated his/her participation in bereavement rituals, and these characteristics are not easily generalizable or measurable.

Table 5.

Physician bereavement practices as a function of spirituality/religiosity: All patients, n (%)

p = .048.

Table 6.

Factors associated with face-to-face bereavement practices (all patients): Multivariate analysis

R2 = 0.09.

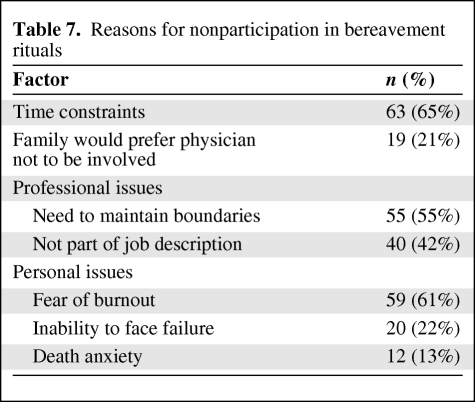

Reasons for Not Participating in Bereavement Practices

Reasons for not participating in bereavement practices are shown in Table 7, which enumerates the percentages of physicians who listed a specific factor as one of the first three responses (out of seven) provided for not participating in a bereavement ritual. Nearly two thirds of the physicians cited time constraints as a major reason for nonparticipation. The second most common reason was related to the fear of burnout. A majority of oncologists (55%) made reference to the need to maintain appropriate boundaries between physician and family as a reason for nonparticipation whereas other physicians believed that attending bereavement rituals was not part of their job description (42%). A majority of physicians linked their non-participation in bereavement practices to a fear of burnout (61%). Most physicians did not attribute their non-participation to perceived family wishes, a sense of failure, and/or death anxiety. Although 55% of respondents reported that they did not attend funerals or visitations because of a lack of time, only 11% answered affirmatively to the question of whether they would attend these bereavement rituals if they were monetarily compensated.

Table 7.

Reasons for nonparticipation in bereavement rituals

Discussion

The issue of physician participation in bereavement practices can be considered from both an empirical and a normative perspective. The empirical questions assess the degree to which physicians participate in these practices, reasons for not participating, and expectations of family members. The normative question of whether physicians should participate in these practices is best considered in the context of empirical findings regarding physicians' participation in bereavement practices.

Several facts can be stated regarding physicians and bereavement practices. First, the level of participation is relatively low. In a study of Oregon physicians by Tolle and colleagues, only 6% of physicians had contact with the family after a patient's death [16]. A follow-up study found that, among 128 surviving spouses of patients who had expired in a university hospital setting, only 50% had any form of contact with physicians [39]. In a study done at a large tertiary referral center, more than two thirds of the physicians did not attend funerals, viewings, or wakes. In terms of home condolence visits, physicians overwhelmingly responded (91.6%) that they never made a home condolence visit for their expired inpatients. Less than 3% of physicians participated in bereavement practices on a consistent basis (defined as >50% participation in these events for expired patients). In terms of indirect contacts, 65.7% stated that they never had written communication with the family and 32.1% did not have phone contact with family members of expired inpatients [8]. In a recent study of oncologists and palliative care physicians, 95% of oncologists and 70% of palliative care physicians rarely or never attended funerals [33].

Our results expand upon these findings. It is a rare physician who makes it a practice to participate in any type of face-to-face bereavement ritual. A large proportion of oncologists do participate in face-to-face bereavement practices other than funerals. For example, 29.8% of the interviewed physicians admitted to occasionally going to a visitation, versus 6.6% who would go to a funeral. It may be that visitations and memorial services are more suited to physicians because they provide a venue in which they can speak to bereaved family members. It is also possible that visitations and memorial services that do not occur immediately after the patient's death provide the physician with greater flexibility in terms of finding the time to attend.

One of the limitations of many earlier studies is that they cluster all types of patients together. However, it has been shown that physicians often build bonds with dying patients, and the duration and nature of the bond can have a significant impact on the patient–physician interaction. For example, Redinbaugh et al. [43] interviewed physicians at two academic centers who dealt with patients dying from cancer. Those authors found that physicians who spent longer periods of time caring for specific patients developed close bonds and felt more vulnerable to feelings of loss when those individuals died [43]. Our findings show that there is an association between a physician's bonding with a specific patient and subsequent participation in bereavement practices.

Physicians' spirituality and religious beliefs have been shown to influence their practice, especially in terms of interactions with patients. In seeking to identify factors associated with bereavement practices, we queried oncologists as to their level of religiosity and spirituality. Individuals who identified themselves as neither religious nor spiritual had the lowest level of participation. What is interesting is that the only group that was more likely to participate in a bereavement practice was comprised of those who were self-identified as both nonreligious and spiritual. Surprisingly, those claiming to be religious and spiritual were not more likely to participate in a bereavement practice. It is not clear why there is a difference between these two groups. Our findings support the argument made by Koenig that spirituality and religiosity are not the same entity, and the two should be differentiated both in terms of practice and how religion and spirituality are characterized in clinical studies [41]. This assertion is supported by a study by Greenfield et al. [42], who found that formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions had independent linkages to diverse measurements of psychological well-being.

Oncologists were surveyed as to reasons why they would or could not participate in bereavement practices. Similar to the observations of Chau et al. [33], we found that time constraints were a major factor in preventing participation in funerals. We noted that the other factors that were also frequently cited subsumed professional issues, including the view that such participation is not a part of a physician's function or the need to maintain boundaries. Interestingly, 61% of our respondents did not want to participate because of a fear of burnout. The fear of burnout may be well based because 30%–50% of oncologists, including medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists, report manifestations of burnout [44–48]. However, it should be noted that there is no objective evidence showing that participation in bereavement rituals contributes to burnout. Factors that might have been expected to play a role, but did not, were the perceived wishes of the family, a sense of failure, and death anxiety, which have been listed as reasons in previous studies or essays.

There are several limitations to this study. Most of those surveyed were Israelis who were Jewish, which raises the issue of the generalizability of the findings. It may be that there are cultural or religious differences that play a role in determining participation in bereavement practices [49]. Likewise, the nature of cancer care delivery in Israel is primarily hospital based (Table 1), and these oncologists may either have a greater or lesser tendency to participate in bereavement practices than community-based oncologists. However, a comparison of our data with those of Chau et al. [33], who studied a more heterogeneous population of oncologists, did not disclose dramatic differences. This would indicate that the low level of participation in bereavement practices is a more universal phenomenon and less likely to be related to cultural or geographic factors.

Another limitation is that oncologists may have overestimated their participation in bereavement practices because of the perceived “social desirability” of such activities [50]. Thus, our data may overrepresent true participation in bereavement practices. To minimize the impact of social desirability, we intentionally avoided asking value-laden questions such as “should physicians attend funerals or send condolence cards,” because this may have biased the response to the empirical questions.

There is also the possibility of responder bias, in which those willing to participate in the survey were more likely to participate in socially desirable or responsible activities such as bereavement practices. Thus, the sample population may not be totally representative of the general population of oncologists and the level of participation in bereavement practices among oncologists may be even lower than what is suggested by our data.

The issue of physician participation in bereavement practices is also normative. From the perspective of families, there are substantial data from both qualitative and quantitative studies indicating that they had a desire and need to see medical personnel after the patient's death [6, 23, 24, 26, 37, 51]. Other studies show that contact with the physician (especially face to face) after a family member's death can provide closure and help with the bereavement process [6, 21, 24, 25]. From the physician's perspective, many medical doctors indicated that it was important for medical staff to be involved in aftercare, and supported initiatives to encourage such participation [5, 8, 33, 43].

Despite the need of families for aftercare and the expressed desire of physicians to offer such services, the bottom line is that few physicians provide face-to-face aftercare on a frequent basis. Whether it is because of time constraints, a physician's belief about his/her role, or an individual physician's fear of burnout, the reality is that aftercare by treating oncologists is not provided to families in a consistent manner. Based on the results of our study, if participation in bereavement practices is left to the discretion of the individual physician, then many families will not have interactions with physicians after the death of the patient.

A practical solution to the problem of aftercare could be the launching of formal programs in which designated medical staff either individually or as a group visit the family and maintain some form of contact. Several oncology and palliative care programs have established such programs, and the response of family members has been positive [52].

Alternatively, consideration may be given to educational interventions for physicians, both in medical school curriculums and postgraduate education, focusing on the needs of families and the role of health care personnel in maintaining contact with relatives even after the death of the patient [53–55]. Likewise, the issues of “burnout,” perceived patient–physician boundaries, and issues of practice priorities can be explored as they relate to bereavement practices [56]. To be sure, not all physicians will participate in bereavement practices, but placing greater emphasis on the status of family members after a patient's death may increase the percentage of physicians who would be willing to be involved in aftercare as part of the holistic approach to the management of terminal patients.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded, in part, by grants from the Life's Door-Tishkofet Foundation and the UJA-Federation of New York.

Appendix 1.

Survey tool (English version)

Appendix 1.

(Continued)

Thank you for taking the time to share your viewpoints.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Benjamin Corn, Esther Shabtai, Ofer Merimsky, Moshe Inbar, Isaiah Wexler

Provision of study material or patients: Benjamin Corn, Ofer Merim sky, Moshe Inbar, Eli Rosenbaum, Amichay Meirovitz, Isaiah Wexler

Collection and/or assembly of data: Benjamin Corn, Esther Shabtai, Eli Rosenbaum, Amichay Meirovitz, Isaiah Wexler

Data analysis and interpretation: Benjamin Corn, Esther Shabtai, Ofer Merimsky, Moshe Inbar, Eli Rosenbaum, Amichay Meirovitz, Isaiah Wexler

Manuscript writing: Benjamin Corn, Esther Shabtai, Ofer Merimsky, Moshe Inbar, Eli Rosenbaum, Amichay Meirovitz, Isaiah Wexler

Final approval of manuscript: Benjamin Corn, Isaiah Wexler

References

- 1.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1986–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penson RT, Green KM, Chabner BA, et al. When does the responsibility of our care end: Bereavement. The Oncologist. 2003;7:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry PA. The absence of sadness: Darker reflections on the doctor-patient relationship. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:266–268. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins-Tracey S, Clayton JM, Kirsten L, et al. Contacting bereaved relatives: The views and practices of palliative care and oncology health care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:807–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dangler LA, O'Donnell J, Gingrich C, et al. What do family members expect from the family physician of a deceased loved one? Fam Med. 1996;28:694–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickinson GE, Tournier RE. A decade beyond medical school: A longitudinal study of physicians' attitudes toward death and terminally-ill patients. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1397–1400. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison NM, Ptacek JT. Physician interactions with families and caregivers after a patient's death: Current practices and proposed changes. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:49–55. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Wolfe P, et al. Talking with terminally ill patients and their caregivers about death, dying, and bereavement: Is it stressful? Is it helpful? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1999–2004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrell B. Meeting spiritual needs: What is an oncologist to do? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:467–468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang LY. A piece of my mind. The first wake. JAMA. 2009;301:467–468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mount BM. Dealing with our losses. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1127–1134. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rea MP, Greenspoon S, Spilka B. Physicians and the terminal patient: Some selected attitudes and behavior. Omega (Westport) 1975;6:291–302. doi: 10.2190/wraw-xv2x-xdre-ucdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinmetz D, Walsh M, Gabel LL, et al. Family physicians' involvement with dying patients and their families. Attitudes, difficulties, and strategies. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.753. discussion 761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolle SW, Elliot DL, Hickam DH. Physician attitudes and practices at the time of patient death. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:2389–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanafelt T, Adjei A, Meyskens FL. When your favorite patient relapses: Physician grief and well-being in the practice of oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2616–2619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donato AA. Rationing empathy. Acad Med. 2009;84:268. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000345399.47940.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson VA, Sullivan AM, Gadmer NM, et al. “It was haunting … ”: Physicians' descriptions of emotionally powerful patient deaths. Acad Med. 2005;80:648–656. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe M. The rest is silence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:232–236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arroll B, Falloon K. Should doctors go to patients' funerals? BMJ. 2007;334:1322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39251.616678.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moores TS, Castle KL, Shaw KL, et al. ‘Memorable patient deaths’: Reactions of hospital doctors and their need for support. Med Educ. 2007;41:942–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: Loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:474–479. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Caring for bereaved patients: “All the doctors just suddenly go”. JAMA. 2001;286:1369–1376. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Main J. Improving management of bereavement in general practice based on a survey of recently bereaved subjects in a single general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:863–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billings JA, Kolton E. Family satisfaction and bereavement care following death in the hospital. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:33–49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rickerson EM, Somers C, Allen CM, et al. How well are we caring for caregivers? Prevalence of grief-related symptoms and need for bereavement support among long-term care staff. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson G. Why don't the doctors attend the funerals of their patients who die? MedGenMed. 2007;9:49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorburn R, Roland M. Attending patients' funerals: We can always care. BMJ. 2007;335:112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39275.958009.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hood GA. Why I go to patients' funerals. Med Econ. 2003;80:88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan SP. Physicians and funerals. JAMA. 1992;267:1266. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.9.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemkau JP, Mann B, Little D, et al. A questionnaire survey of family practice physicians' perceptions of bereavement care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:822–829. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chau NG, Zimmermann C, Ma C, et al. Bereavement practices of physicians in oncology and palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:963–971. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bedell SE, Cadenhead K, Graboys TB. The doctor's letter of condolence. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1162–1164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janson CG. Essay. White daisies on my mind (Requiem for an Alzheimer patient) Neurology. 2005;65:654–656. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173032.00531.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irvine P. The attending at the funeral. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1704–1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506273122608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milberg A, Olsson EC, Jakobsson M, et al. Family members' perceived needs for bereavement follow-up. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA, et al. On saying goodbye: Acknowledging the end of the patient-physician relationship with patients who are near death. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:682–685. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolle SW, Bascom PB, Hickam DH, et al. Communication between physicians and surviving spouses following patient deaths. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1:309–314. doi: 10.1007/BF02596210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puchalski C, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:129–137. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenig HG. Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;96:349–355. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816ff796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenfield EA, Vaillant GE, Marks NF. Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:196–212. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redinbaugh EM, Sullivan AM, Block SD, et al. Doctors' emotional reactions to recent death of a patient: Cross sectional study of hospital doctors. BMJ. 2003;327:185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1263–1269. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whippen DA, Canellos GP. Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: Results of a random survey of 1,000 oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1916–1920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balch CM, Copeland E. Stress and burnout among surgical oncologists: A call for personal wellness and a supportive workplace environment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3029–3032. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis AE. Reducing burnout: Development of an oncology staff bereavement program. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:1065–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyckholm L. Avoiding stress and burnout in cancer care. Words of wisdom from fellow oncologists. Oncology (Williston Park) 2007;21:269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witztum E, Malkinson R, Rubin SS. Death, bereavement and traumatic loss in Israel: A historical and cultural perspective. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2001;38:157–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:859–883. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med. 2004;18:39–45. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm837oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stein J, Peles-Borz A, Buchval I, et al. The bereavement visit in pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3705–3707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilewski T. The art of medicine: Teaching oncology fellows about the end of life. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dickinson GE. Teaching end-of-life issues in US medical schools: 1975 to 2005. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23:197–204. doi: 10.1177/1049909106289066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, et al. A study of oncology fellows' training in end-of-life care. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Armstrong J, Lederberg M, Holland J. Fellows' forum: A workshop on the stresses of being an oncologist. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19:88–90. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1902_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]