Abstract

Objectives To test whether bisphosphonate use is related to improved implant survival after total arthroplasty of the knee or hip.

Design Population based retrospective cohort study.

Setting Primary care data from the United Kingdom.

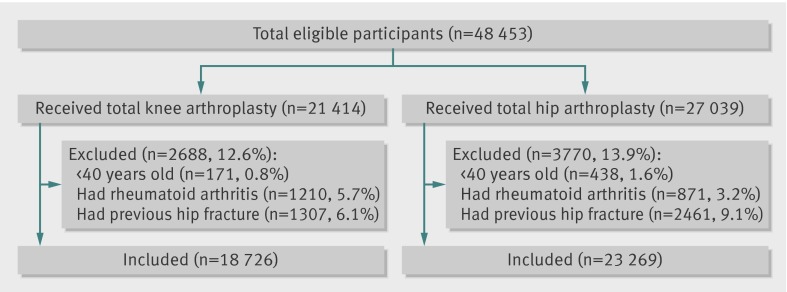

Participants All patients undergoing primary total arthroplasty of the knee (n=18 726) or hip (n=23 269) in 1986-2006 within the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database. We excluded patients with a history of hip fracture before surgery or rheumatoid arthritis, and individuals younger than 40 years at surgery.

Intervention Bisphosphonate users were classified as patients with at least six prescriptions of bisphosphonates or at least six months of prescribed bisphosphonate treatment with more than 80% adherence before revision surgery.

Outcome measures Revision arthroplasties occurring after surgery, identified by READ and OXMIS codes. Parametric survival models were used to determine effects on implant survival with propensity score adjustment to account for confounding by indication.

Results Of 41 995 patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty, we identified 1912 bisphosphonate users, who had a lower rate of revision at five years than non-users (0.93% (95% confidence interval 0.52% to 1.68%) v 1.96% (1.80% to 2.14%)). Implant survival was significantly longer in bisphosphonate users than in non-users in propensity adjusted models (hazard ratio 0.54 (0.29 to 0.99); P=0.047) and had an almost twofold increase in time to revision after hip or knee arthroplasty (time ratio 1.96 (1.01 to 3.82)). Assuming 2% failure over five years, we estimated that the number to treat to avoid one revision was 107 for oral bisphosphonates.

Conclusions In patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty, bisphosphonate use was associated with an almost twofold increase in implant survival time. These findings require replication and testing in experimental studies for confirmation.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in the Western world, with total joint arthroplasty being the most effective therapy for severe osteoarthritis of the lower limb.1 Osteoarthritis accounted for 97% of 71 527 primary total arthroplasties of the knee and for 93% of 64 772 primary total arthroplasties of the hip performed in the United Kingdom in 2009.2 Furthermore, increases in the numbers of elderly and obese individuals have driven up rates of primary arthroplasty.3

Revision surgery has a poorer clinical outcome than primary joint surgery4 5 and is more costly.6 According to the 7th annual report of the National Joint Registry for England and Wales, revision rates at five years were 2.9% and 3.6% for total hip and knee arthroplasties, respectively (using data collected from 2003 to 2009).2 In 2003, about one in 75 patients needed a revision of their prosthesis within three years.7 The most common cause of revision is loosening, which occurs if the bone supporting the implant is resorbed.2 Bone remodelling at the bone-implant interface leads to localised bone lysis, which may also result in the need for revision.8

Efforts to identify patients at risk of revision and develop new treatments to improve implant survival are urgently needed. Bisphosphonates, through their antiresorptive properties on osteoclast activity, have potential protective effects on implant survival.4 Some randomised clinical trials,9 10 11 12 but not all,13 have suggested a potential benefit of bisphosphonate treatment on implant survival after total arthroplasty of the knee or hip, by showing improvements in surrogate outcomes such as implant migration. However, none of the trials had used revision of the implant as the primary outcome.

We aimed to test whether bisphosphonate use is associated with increased survival of implants in the lower limb after primary total arthroplasty.

Methods

Study population

We used a cohort of patients from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database with a medical diagnosis code for primary total arthroplasty of the hip or knee from 1986 to the end of 2006. The database comprises computerised records of all clinical and referral events in both primary and secondary care in addition to comprehensive demographic information. Data include medication prescriptions, clinical events, specialist referrals, and hospital admissions with their major outcomes in a sample of 6.5 million patients from 433 contributing practices, chosen to be representative of the wider UK population. The database, which is managed by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency,14 only includes general practices that pass quality control. Deletion or encoding of personal and clinic identifiers ensures the confidentiality of information in the database. Data are stored using OXMIS (Oxford Medical Information System (UK)) and READ codes for diseases that are cross referenced to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9); we used these codes to identify primary total arthroplasty of the knee or hip.

Patients were included in the analysis if aged 40 years or over at the time of surgery. We excluded individuals with a medical diagnosis code for rheumatoid arthritis. Since we could not accurately differentiate patients undergoing arthroplasty for osteoarthritis from those undergoing arthroplasty for either an acute hip fracture or a late complication of hip fracture, we excluded individuals with a history of hip fracture before primary arthroplasty. Using these criteria, we identified 41 995 eligible participants: 23 269 with hip arthroplasty and 18 726 with knee arthroplasty. To calculate the rate of revision, we followed up patients for a maximum of 15 years after surgery.

Main outcome

The main outcome of this study was implant survival, calculated as the time from primary total arthroplasty to revision surgery. We identified patients undergoing a surgical revision by using their READ and OXMIS codes (web appendix).

Identification of bisphosphonate users

According to the General Practice Research Database, patients were prescribed the following oral bisphosphonates: alendronate, etidronate, ibandronate, and risedronate. We defined bisphosphonate users by two criteria. Firstly, we identified patients who had been prescribed bisphosphonates by their general practitioner at least six months before revision surgery for at least six months and who had a high adherence—that is, a medication possession ratio of more than 80%.15 The medication possession ratio is defined as the proportion of days between the first prescription and the last prescription of bisphosphonates for which the patient has medication supplied. Secondly, we identified patients who had filled at least six prescriptions of bisphosphonates.

We defined bisphosphonate non-users as individuals who were never prescribed bisphosphonates or who had their first prescription of bisphosphonates after a revision surgery. Oral bisphosphonate treatment for a short duration has been shown not to have a biologically plausible effect on bone strength, based on clinical outcomes.16 Therefore, we also classified partial users of bisphosphonates as non-users—that is, individuals with fewer than six prescriptions and either less than six months of treatment or a medication possession ratio of less than 0.8.

Covariates

We considered the following potential confounders for the study:

Age

Sex

Body mass index

Type of joint replaced (hip/knee)

Year of joint replacement operation

Recorded diagnosis of osteoarthritis (yes/no)

Previous fracture before surgery (yes/no)

Use of calcium and vitamin D supplements (yes/no)

Use of hormone replacement therapy or selective oestrogen receptor modulators (yes/no)

Oral glucocorticosteroid treatment (yes/no)

Smoking status and alcohol intake, recorded closest to the date of primary surgery

General practice deprivation score (as defined by the Index of Multiple Deprivation)

Location of surgery (UK region)

Comorbid conditions registered by physician: asthma, malabsorptive syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (yes/no)

Chronic kidney failure (yes/no)

Neoplasms (yes/no)

Diabetes (yes/no)

Use of drugs that might affect fracture risk: proton pump inhibitors, antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, anti-parkinson drugs, statins, thiazide diuretics, and anxiolytics

We identified patients with a previous hip fracture by using the following READ and OXMIS codes: S302.00, S30y.00, S30..11, S302400, S30..00, S305.00, S314.00, S31..00, S310100, S31z.00, 7K1L400, S30y.11, S310.00, 14G7.00, 820 T, 820 B, 8210, and 820A.

Statistical analyses

We used propensity score adjustment to reduce the effects of confounding by indication and to accurately estimate the effect of bisphosphonates in a non-experimental observational study.17 The propensity score for bisphosphonate use represents the probability that a patient is prescribed bisphosphonate treatment, and was estimated for the whole study population by multivariate logistic regression modelling.18 Bisphosphonate use was a binary outcome and fractional polynomial regression modelling was used to account for non-linear effects of age and body mass index.

We imputed data for important missing covariates (that is, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol intake) in the propensity and survival models, because the cumulative effect of missing data often excludes a substantial proportion of the original sample, causing a loss of precision and power. This bias can be overcome by multiple imputation, which avoids the uncertainty of missing data by creating several plausible imputed datasets and appropriately combining their results. We used the procedure for imputation by chained equations in Stata,19 and included all predictor variables in the multiple imputation process, together with the outcome variable and length of follow-up time on the log scale since this information helps calculate the missing values of the predictors. The resulting logistic equation for a propensity score yielded a C statistic of 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.79), indicating a good adjustment for confounding by indication.

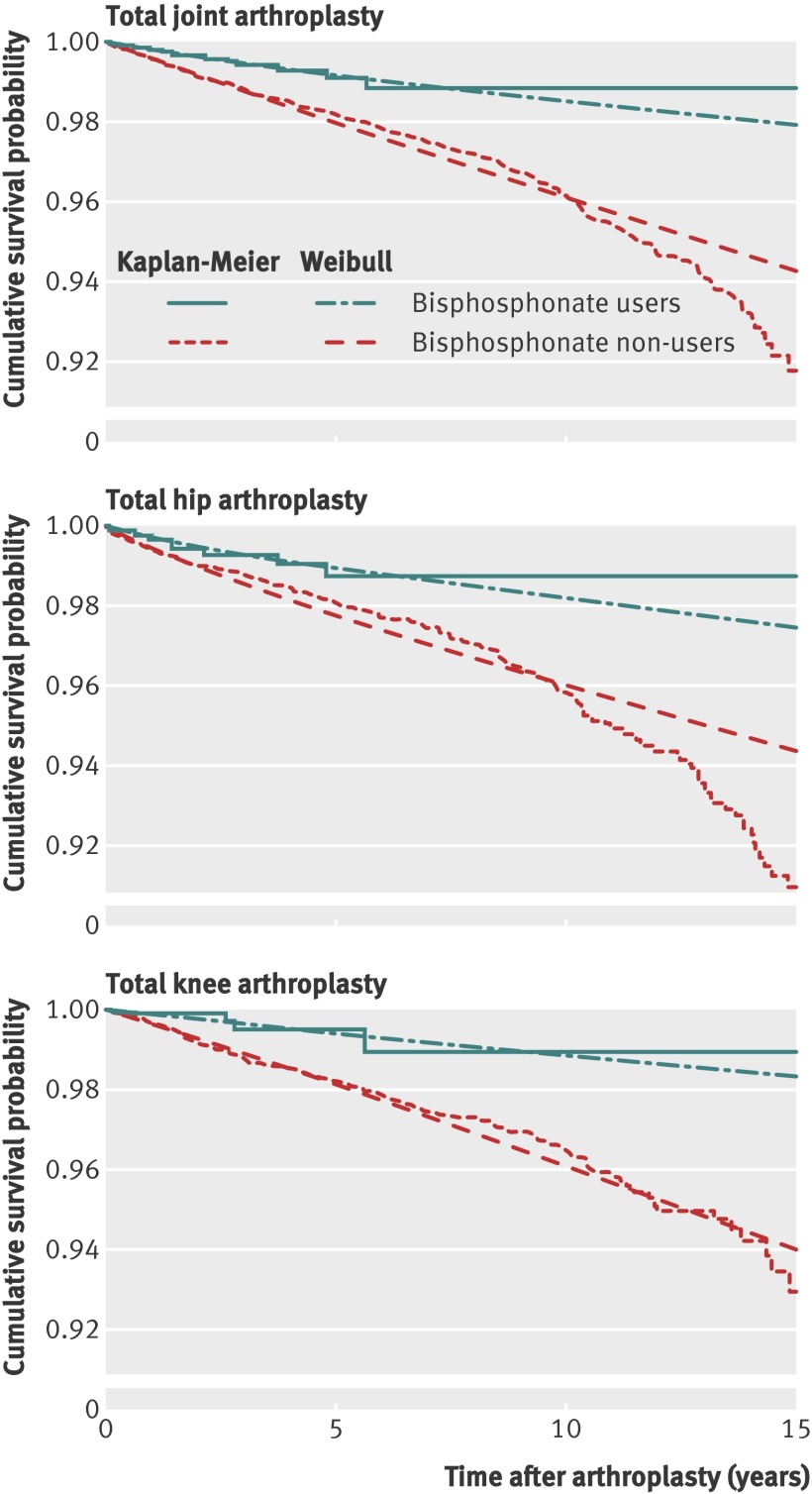

We calculated unadjusted rates of implant revision at five years for bisphosphonate users and non-users. We then tested the association between bisphosphonate use and implant revision using survival models adjusted for propensity score. Patients who left the registered practice or died were right censored. We first illustrated implant survival using non-parametric Kaplan-Meier plots, and then used parametric Weibull survival models to measure the effect of bisphosphonate use on implant survival both as a hazard function and a time ratio to improve interpretation.20 Assumptions underlying the parametric survival model were assessed with likelihood ratio tests, with no evidence seen of non-proportional hazards or times.

We had postulated a priori that an interaction between bisphosphonate use and the following variables might be present: sex, history of fracture before surgery, or type of joint replaced (knee or hip). To test for these variables, we included multiplicative interaction terms in survival models. However, in view of the strong protective effect of bisphosphonates on implant survival, the treated group did not have enough events to model these interactions.

As a guide to the clinical effect size, we calculated the number needed to treat to avoid one revision at 15 years of follow-up, based on the survival probability function and the hazard ratio. We did all statistical analyses using Stata (version 11.1).

Results

Of 48 453 eligible patients with primary total arthroplasty of the hip (n=27 039) or knee (n=21 414), we excluded 6458 (13.3%) from our analyses. In all, 2081 (4.3%) excluded patients had a physician diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, 609 (1.3%) underwent arthroplasty at age less than 40 years, and 3768 (7.8%) had a history of hip fracture before primary surgery (fig 1). Accordingly, we included and followed up 41 995 participants with hip (n=23 269) or knee (n=18 726) arthroplasty for a median of 3.5 years (interquartile range 1.6-6.3). Of 1912 (4.6%) patients classified as bisphosphonate users, 1484 (77.6%) did not have any history of fracture before the primary arthroplasty and the remaining 428 participants had at least one fracture before undergoing revision joint arthroplasty.

Fig 1 Population flowchart

The median duration of bisphosphonate treatment and was 3.07 years (interquartile range 1.65-5.20) and the median number of prescriptions was 19 (11-33). The median time (interquartile range) from first bisphosphonate prescription to primary surgery was 11.8 months (14.5 months before surgery to 39.5 months after surgery). Median time from first prescription to revision surgery was 34.0 months (10.8-55.5 months). Compared with non-users, bisphosphonate users were significantly older, thinner, and more likely to be female; they also had more comorbidities and used more fracture related drugs. We used these attributes for the propensity adjustment (table 1).

Table 1 .

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Total population (n=41 995) | Bisphosphonate use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=1912) | No (n=40 083) | P value of difference | ||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 69.98 (9.67) | 73.83 (8.15) | 69.80 (9.70) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 24 733 (58.9) | 1629 (85.2) | 23 104 (57.6) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 28.09 (4.88) | 26.64 (4.86) | 28.16 (4.88) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status*: | ||||

| Yes | 4640 (11.1) | 161 (8.6) | 4479 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 23 031 (54.8) | 1100 (58.4) | 21 931 (56.8) | |

| Former smoker | 12 833 (30.6) | 622 (33.0) | 12 211 (31.6) | |

| Alcohol drinking status*: | ||||

| Yes | 29 444 (70.1) | 1256 (73.5) | 28 188 (79.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 5342 (12.7) | 290 (17.0) | 5052 (14.2) | |

| Former drinker | 2469 (5.9) | 163 (9.5) | 2306 (6.5) | |

| Joint replaced (hip) | 23 269 (55.4) | 1052 (55.0) | 22 217 (55.4) | 0.73 |

| Osteoarthritis of the knee or hip | 34 336 (81.8) | 1532 (80.1) | 32 804 (81.8) | 0.058 |

| Diabetes | 4701 (11.2) | 156 (8.2) | 4545 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4223 (10.1) | 166 (8.7) | 4057 (10.1) | 0.041 |

| Deprivation score (general practice)*: | ||||

| 0 | 9686 (23.1) | 444 (23.4) | 9242 (23.2) | 0.023 |

| 1 | 7069 (16.8) | 305 (16.1) | 6764 (17.0) | |

| 2 | 8815 (21.0) | 452 (23.9) | 8363 (21.0) | |

| 3 | 8671 (20.7) | 358 (18.9) | 8313 (20.9) | |

| 4 | 7476 (17.8) | 336 (17.7) | 7140 (17.9) | |

| No of comorbid conditions†: | ||||

| 0 | 16 157 (38.5) | 536 (28.0) | 15 621 (39.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 15 647 (37.3) | 744 (38.9) | 14 903 (37.2) | |

| 2 | 7169 (17.1) | 427 (22.3) | 6742 (16.8) | |

| 3 | 2307 (5.5) | 154 (8.1) | 2153 (5.4) | |

| ≥4 | 715 (1.7) | 51 (2.7) | 664 (1.7) | |

| Time to implant failure (years): | ||||

| 0 to 5 | 522 (1.2) | 11 (0.6) | 511 (1.3) | |

| 0 to 15 | 748 (1.8) | 12 (0.6) | 736 (1.8) | |

| Median (IQR) follow-up time before failure | 3.54 (1.63-6.33) | 3.21 (1.56-5.19) | 3.57 (1.63-6.41) | <0.001 |

| Fracture before primary surgery | 5684 (13.5) | 428 (22.4) | 5256 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Use of other drugs: | ||||

| HRT-SERM | 5933 (14.1) | 315 (16.5) | 5618 (14.0) | 0.003 |

| Calcium-vitamin D supplements | 553 (1.3) | 96 (5.0) | 457 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 118 (0.3) | 9 (0.5) | 109 (0.3) | 0.11 |

| Other drugs associated with increased fracture risk‡ | 9395 (22.4) | 502 (26.3) | 8893 (22.2) | <0.001 |

IQR=interquartile range. HRT-SERM=hormone replacement therapy-selective oestrogen receptor modulator. χ2 test and t test used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

*Missing data for body mass index (n=5122), smoking (n=1491), alcohol drinking status (n=4740), and deprivation score (n=278).

†Any of the following: asthma, malabsorption syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, and cancer.

‡Any of the following: anti-arrhythmic drugs, anticonvulsants, or tricyclic antidepressants.

Bisphosphonate users and revision rates

At five years’ follow-up, 522 (1.2%) participants had revision surgery (304 (1.3%) for hip, 218 (1.2%) for knee). Overall, we recorded 511 (1.3%) revisions (296 (1.3%) hip, 215 (1.2%) knee) in bisphosphonate non-users, with a lower rate of 11 (0.6%) in users (eight (0.8%) hip, three (0.3%) knee). For patients with at least five years of follow-up, bisphosphonate users had a lower revision rate at five years than non-users (0.93% (95% confidence interval 0.52% to 1.68%) v 1.96% (1.80% to 2.14%)).

Table 2 and figure 2 show that bisphosphonate use had a strongly protective effect on implant survival throughout the study (adjusted hazard ratio 0.54 (95% confidence interval 0.29 to 0.99), P=0.047), with a significant increase in median prosthesis survival (time ratio 1.96 (1.01 to 3.82)). After stratifying for the type of joint replaced (knee or hip), we found that the time to revision more than doubled after knee arthroplasty, with a borderline significance (time ratio 2.37 (0.94 to 6.01)), and increased by a non-significant 70% after hip arthroplasty (1.71 (0.74 to 3.94)).

Table 2 .

Parametric Weibull model assessment of the effect of bisphosphonate use on prosthesis survival, up to 15 years after surgery

| Study group | Unadjusted models | Propensity adjusted models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) for implant failure | Time ratio (95% CI) for implant survival | P value* | Hazard ratio (95% CI) for implant failure | Time ratio (95% CI) for implant survival | P value* | ||

| Total population (n=41 995) | 0.41 (0.22 to 0.76) | 2.54 (1.34 to 4.83) | 0.004 | 0.54 (0.29 to 0.99) | 1.96 (1.01 to 3.82) | 0.047 | |

| Population diagnosed with osteoarthritis (n=34 336) | 0.30 (0.13 to 0.70) | 3.47 (1.44 to 8.37) | 0.005 | 0.40 (0.17 to 0.93) | 2.69 (1.07 to 6.73) | 0.034 | |

| Population undergoing knee arthroplasty (n=18 726) | 0.33 (0.12 to 0.88) | 2.79 (1.12 to 6.91) | 0.027 | 0.40 (0.15 to 1.07) | 2.37 (0.94 to 6.01) | 0.068 | |

| Population undergoing hip arthroplasty (n=23 269) | 0.47 (0.24 to 0.94) | 2.36 (1.07 to 5.21) | 0.033 | 0.64 (0.32 to 1.28) | 1.71 (0.74 to 3.94) | 0.20 | |

P values apply to both time ratios and hazard ratios.

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier and Weibull model estimates for revision events after primary total arthroplasty of the hip, knee, and joint

As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated these propensity adjusted survival models for the 34 336 (81.8%) patients who had a documented diagnosis of osteoarthritis in their primary care records. Among these patients, bisphosphonate use had a greater protective effect on failure risk (adjusted hazard ratio 0.40 (0.17 to 0.93), P=0.034; time ratio 2.69 (1.07 to 6.73)).

Assuming an accumulated incidence of failure of 2% over five years, we estimated that the number to treat to avoid one revision was 107 for patients aged more than 40 years undergoing lower limb arthroplasty for osteoarthritis.

Discussion

We have shown that bisphosphonate use is associated with a significantly lower rate of revision surgery of up to about 50% and a twofold greater median implant survival time after primary total arthroplasty of the lower limb in patients without a previous fracture. The observed effect size was higher for patients who had a knee arthroplasty than for those who had a hip arthroplasty, although the statistical power to confirm this difference was limited. Finally, in patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis by their general practitioners, bisphosphonate use had a greater protective effect, with an almost threefold greater median prosthesis survival time.

Comparison with other studies

The most common cause of failure of a hip or knee prosthesis requiring revision is aseptic loosening, which accounted for around 56% and 41% of revisions done after total arthroplasties of the hip and knee, respectively, in the UK in 2009.21 The mechanism for loosening is thought to be a sustained chronic inflammatory response, which recruits macrophages, osteoclasts, and other cells to accelerate the loss of periprosthetic bone. These pathways could be prevented by bisphosphonate treatment.22

Currently published data are conflicting about the protective effect of bisphosphonates on different surrogates for total hip or knee arthroplasty failure. Although some authors13 have not found any significant effect of oral bisphosphonates, others9 10 11 12 have reported a potential benefit of bisphosphonates, both as oral or intravenous treatment, on several surrogate markers for failure such as bone integration and prosthesis migration. While the studies showing a beneficial effect have covered oral, local, and intravenous treatment of bisphosphonates, the intervention group in the only study showing no effect on implant migration14 received weekly doses of oral alendronate for six months, which was the minimum duration of treatment we considered in our study to define bisphosphonate users. Regarding the effect of bisphosphonates on periprosthetic bone loss, a recently published systematic review23 and a meta-analysis24 have also provided conflicting results.

Our results are consistent with most of the published trials, since we showed a significant protective effect of oral bisphosphonates on implant failure risk after hip or knee arthroplasty, using revision as the clinical end point. Although we did not have enough statistical power to show a definitive result, the protective benefit of bisphosphonate use seemed most effective after five years, when the most common cause of failure is loosening secondary to osteolysis.

A recent case-control study from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register reported a non-significant association between the long term use of bisphosphonates and a reduced risk of revision, but an increased risk of revision due to deep infections among bisphosphonate users.25 However, unlike our study, the researchers restricted their sample to patients with either osteoporosis (as registered in the database) or a previous osteoporotic fracture, they only examined effects on total hip arthroplasty, and they did not exclude individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, who would have probably been at an raised risk of loosening due to increased rates of bone turnover and infection caused by immunosuppression. In our study, we excluded patients with a previous hip fracture (in whom the mechanism for revision is likely to lead to complications such as altered gait and risk of falls 26 and persisting periprosthetic symptoms) but included individuals with fractures at other skeletal sites.

Our finding of a stronger protective effect associated with bisphosphonate use in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of osteoarthritis could indicate misclassification of participants without a code for osteoarthritis even though we excluded those with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis or hip fracture. Furthermore, patients with a primary care diagnosis of osteoarthritis might also have more severe disease, either structurally and or symptomatically. Further work should aim to identify the radiographic grade and patient symptom score at the time of surgery and the benefit from bisphosphonate use.

We have published a potential role for bisphosphonates in minimising the increased risk of fractures seen immediately after a total knee arthroplasty.27 28 If, in addition to fracture reduction, bisphosphonate use leads to a reduced risk of implant failure and therefore an extension of implant survival, its use should be assessed in clinical settings. If these findings are replicated in other observational cohorts, a randomised clinical trial is needed to test the efficacy and cost effectiveness of bisphosphonate use at or before the time of surgery to improve implant survival and reduce fracture risk.

We estimated that the number of patients needed to treat to avoid one failure was 107 for oral bisphosphonates. This number is about five times that needed to avoid one vertebral fracture in patients with osteoporosis (range 9-21), and higher than the number corresponding to the effect of oral bisphosphonates on hip fracture prevention (91 patients).29 However, the costs of revision surgery are higher than either of these two settings; the estimated average total cost for all types of revision arthroplasties is about $54 000 (£34 268.40; €40 078.80).6

Potential side effects associated with bisphosphonate use should be taken into account before initiating treatment in these patients. However, the relatively low incidence of side effects (1-0.1/10 000 patient years for treatment for osteonecrosis of the jaw30 31 and about 5/10 000 patient years for atypical fractures32) seems very low when compared with our estimated number needed to treat. Further work needs to establish whether individuals who will benefit most from treatment can be identified within the heterogeneity of patient groups who undergo total joint arthroplasty, in terms of age, sex, and other established determinants for poor skeletal status.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study’s main strengths were the long period of follow-up and the generalisability of the General Practice Research Database, which represents the vast majority of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Population based cohorts provide data for a wide range of subjects, including both sexes, older patients, and individuals with comorbid conditions. In addition, data from the General Practice Research Database accurately reflect primary care in the UK, because they are collected from a representative sample of general practices. Hence, the observed protective effect of bisphosphonate use on implant survival could be assumed to be valid for the wider population of patients undergoing a total hip or knee replacement.

A potential limitation was the completeness of the coding for revision surgery and of important potential confounding variables. Nevertheless, the General Practice Research Database has been widely used for epidemiological research, with high validity and completeness for prescription data and discrete outcomes such as fracture and surgery.

In the absence of information indicating the side of primary or revision surgery in patients with bilateral replacements, some revisions could have been contralateral to the primary operation. We propose that this misclassification would have little effect on our results; our observed revision rate (about 2% for a median 3.5 years of follow-up) was similar to that reported by the National Joint Registry (2.9% for and 3.6% for total hip and knee arthroplasty, respectively, at five years of follow-up).2 Furthermore, any misclassification would probably be random in the groups of bisphosphonate users and non-users, and therefore would tend to bias our results towards the null hypothesis.

The design of this study was observational, and considerable controversy exists on whether this type of study can provide reliable information on causality and, especially, on the effectiveness of drugs.33 Nevertheless, we have used propensity score adjustment as a method to control for confounding by indication, which is currently recognised as the best analytical approach to reduce such confounding.17 Furthermore, findings from observational studies using electronic medical records from primary care databases (such as the General Practice Research Database) have been compared with findings from randomised control trials, with promising results if appropriate methods (such as propensity score adjustment) are used to reduce confounding.34

Unsolved issues were residual confounding (due to unobserved variables such as bone mineral density, ethnic origin, design of implant, or type of fixation) and the absence of a non-active comparator compound to take into account the placebo effect. Furthermore, we could not assess the effect of other antiresorptive drugs on implant survival, because only 13 patients could be defined as calcitonin users and one patient as a strontium ranelate user. We also did not identify any users of either parathormone or bisphosphonate preparations that included vitamin D, because the last patient was followed up until the end of 2006, when these drugs were not available in the UK.

What is already known on this topic

Although bisphosphonates have theoretical benefits on implant survival, direct evidence for effects on clinical outcomes is scarce

What this study adds

In an observational cohort of patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty, bisphosphonate use was related to an almost twofold increase in implant survival time. These findings need confirmation in experimental studies

Contributors: All the authors drafted the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published. NKA had full access to all the data in the study and is the study guarantor. DP-A, NKA, MKJ, and CC were responsible for the study concept and design. DP-A, CC, and NKA were responsible for the data collection. All the authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding: This research was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407-10064). The study also received funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit into Musculoskeletal Disease, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, and University of Oxford; Institut Catala de la Salut-IDIAP Jordi Gol (via a grant for a research fellowship at the Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica); and Merck, Sharpe and Dohme, Novartis, and Southampton Rheumatology Trust (via unrestricted educational grants).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that: DP-A, AJ, and AC have no conflicts of interest; MKJ, NKA, and CC have received honorariums, held advisory board positions (which involved receipt of fees), and received consortium research grants, respectively, from: Novartis and Alliance for Better Health and Lilly; Merck, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche, Novartis, Smith and Nephew, Q-MED, Nicox, Servier, GlaxoSmithKline, Schering-Plough, Pfizer, and Rottapharm; and Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Novartis, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Servier, Eli Lilly, and GlaxoSmithKline; they have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The General Practice Research Database group obtained ethical approval from a multicentre research ethics committee for purely observational research using data from the database, such as ours. This study obtained approval from the independent scientific advisory committee of the General Practice Research Database, which is responsible for reviewing protocols for scientific quality.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d7222

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: READ and OXMIS codes used to identify surgical revision of primary knee or hip replacement

References

- 1.Harris WH, Sledge CB. Total hip and total knee replacement. N Engl J Med 1990;323:725-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Joint Registry. National joint registry for England and Wales. 7th annual report; 2010.

- 3.Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Tudor G, Koch GG, et al. One in four people may develop symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in his or her lifetime. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Steiger RN, Miller LN, Prosser GH, Graves SE, Davidson DC, Stanford TE. Poor outcome of revised resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010;81:72-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hossain F, Patel S, Haddad F. Midterm assessment of causes and results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:1221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:128-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibanda N, Copley LP, Lewsey JD, Borroff M, Gregg P, MacGregor AJ, et al. Revision rates after primary hip and knee replacement in England between 2003 and 2006. PLoS Med 2008;5:e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anthony P, Gie G, Howie C, Ling R. Localised endosteal bone lysis in relation to the femoral components of cemented total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72-B:971-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Goodship AE, Blunn GW, Green J, Coathup MJ. Prevention of strain-related osteopenia in aseptic loosening of hip prostheses using perioperative bisphosphonate. J Orthop Res 2008;26:693-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilding M, Aspenberg P. Local peroperative treatment with a bisphosphonate improves the fixation of total knee prostheses: a randomized, double-blind radiostereometric study of 50 patients. Acta Orthop 2007;78:795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilding M, Aspenberg P. Postoperative clodronate decreases prosthetic migration: 4-year follow-up of a randomized radiostereometric study of 50 total knee patients. Acta Orthop 2006;77:912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedl G, Radl R, Stihsen C, Rehak P, Aigner R, Windhager R. The effect of a single infusion of zoledronic acid on early implant migration in total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:274-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansson U, Toksvig-Larsen S, Ryd L, Aspenberg P. Once-weekly oral medication with alendronate does not prevent migration of knee prostheses. Acta Orthop 2009;80:41-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walley T, Mantgani A. The UK General Practice Research Database. Lancet 1997;350:1097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brankin E, Walker M, Lynch N, Aspray T, Lis Y, Cowell W. The impact of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonates among postmenopausal women in the UK: evidence from three databases. Curr Medical Res Opin 2006;22:1249-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Delzell E, Saag KG. Risk of hip fracture after bisphosphonate discontinuation: implications for a drug holiday. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1613-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Normand S-LT, Sykora K, Li P, Mamdani M, Rochon PA, Anderson GM. Readers guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 2005;330:1021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41-55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update of ice. Stata J 2005;5:527-36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox C, Chu H, Schneider MF, Muñoz A. Parametric survival analysis and taxonomy of hazard functions for the generalized gamma distribution. Stat Med 2007;26(23):4352-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 6th annual report; 2009.

- 22.Abu-Amer Y, Darwech I, Clohisy J. Aseptic loosening of total joint replacements: mechanisms underlying osteolysis and potential therapies. Arthritis Res Ther 2007;9:S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng Y, Lai O, Shen B, Yang J, Zhou Z, Kang P, Pei F. A systematic review assessing the effectiveness of alendronate in reducing periprosthetic bone loss after cementless primary THA. Orthopedics 2011;34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lin T, Yan SG, Cai XZ, Ying ZM. Bisphosphonates for periprosthetic bone loss after joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 2011; published online 20 September. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Thillemann TM, Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Johnsen SP, Søballe K. Postoperative use of bisphosphonates and risk of revision after primary total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide population-based study. Bone 2010;46:946-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lloyd BD, Williamson DA, Singh NA, Hansen RD, Diamond TH, Finnegan TP, et al. Recurrent and injurious falls in the year following hip fracture: a prospective study of incidence and risk factors from the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:599-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prieto-Alhambra D, Javaid M, Judge A, Maskell J, Kiran A, Cooper C, et al. Bisphosphonate use and risk of post-operative fracture among patients undergoing a total knee replacement for knee osteoarthritis: a propensity score analysis. Osteoporosis Int 2011;22:1555-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prieto-Alhambra D, Javaid MK, Maskell J, Judge A, Nevitt M, Cooper C, et al. Changes in hip fracture rate before and after total knee replacement due to osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reginster JY. Antifracture efficacy of currently available therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Drugs 2011;71:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook P, Olver I, Goss A. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Aust Fam Physician 2006;35:801-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felsenberg D. Osteonecrosis of the jaw--a potential adverse effect of bisphosphonate treatment. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2006;2:662-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1728-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ioannidis JPA, Haidich A-B, Pappa M, Pantazis N, Kokori SI, Tektonidou MG, et al. Comparison of evidence of treatment effects in randomized and nonrandomized studies. JAMA 2001;286:821-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tannen RL, Weiner MG, Xie D. Use of primary care electronic medical record database in drug efficacy research on cardiovascular outcomes: comparison of database and randomised controlled trial findings. BMJ 2009;338:b81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: READ and OXMIS codes used to identify surgical revision of primary knee or hip replacement