Abstract

The superfamily of glutathione S-transferases has been the subject of extensive study but Actinobacteria produce mycothiol (MSH) in place of glutathione and no mycothiol S-transferase (MST) has been identified. Using mycothiol and monochlorobimane as substrates a MST activity was detected in extracts of Mycobacterium smegmatis and purified sufficiently to allow identification of MSMEG_0887, a member the DUF664 family of the DinB superfamily, as the MST. The identity of the M. smegmatis and homologous Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Rv0443) enzymes was confirmed by cloning and the expressed proteins were found to be active with MSH but not bacillithiol (BSH) or glutathione (GSH). Bacillus subtilis YfiT is another member of the DinB superfamily but this bacterium produces BSH. The YfiT protein was shown to have S-transferase activity with monochlorobimane when assayed with BSH but not with MSH or GSH. Enterococcus faecalis EF_3021 shares some homology with MSMEG_0887 but this organism produces GSH but not MSH or BSH. Cloned and expressed EF_0321 was active with monochlorobimane and GSH but not with MSH or BSH. MDMPI_2 is another member of the DinB superfamily and has been previously shown to have mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate isomerase activity. Three of the eight families of the DinB superfamily include proteins shown to catalyze thiol-dependent metabolic or detoxification activities. Since more than two-thirds of the sequences assigned to the DinB superfamily are members of these families it seems likely that such activity is dominant in the DinB superfamily.

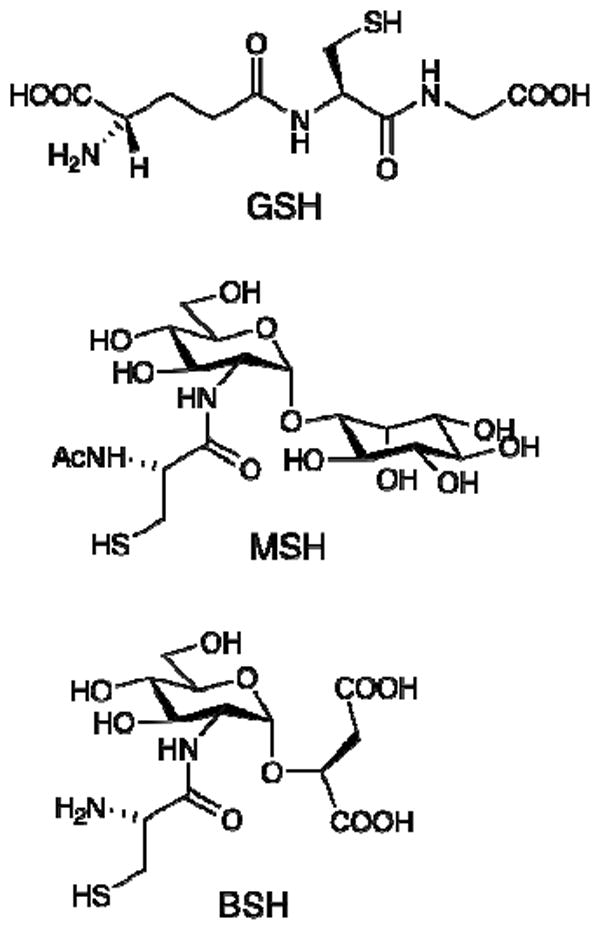

Most aerobic organisms generate a low-molecular-weight thiol that plays a role in protecting against oxidative stress and in the neutralization of electrophilic toxins. In eukaryotes the thiol is glutathione (GSH, Figure 1) and the glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) constitute a superfamily of enzymes that catalyze the reaction of GSH with a wide range of electron deficient substrates (1-4). Chlorinated hydrocarbons are one important class of GST substrates and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) is a convenient, but not universal, assay substrate (5). GSTs also catalyze the reduction of organic hydroperoxides by GSH, the addition of GSH to enals, enones and thiocarbamates, the conjugation of GSH with epoxides, and the GSH-dependent isomerization at carbon-carbon double bonds (3). The GST superfamily includes at least 15 different enzyme classes (3, 6) and these enzymes are currently a common subject of research.

Figure 1.

Structures for glutathione (GSH), mycothiol (MSH) and bacillithiol (BSH).

In prokaryotes the situation is more complex. GSH is absent in many Gram-positive bacteria (7) and those bacteria that possess GSH produce it in a variety of different ways. Some bacteria have similar independent genes encoding γ-glutamylcysteine ligase (GshA) and GSH synthetase (GshB) to produce γ-Glu-Cys-Gly (GSH), as occurs in most eucaryotes (8). However, the genomes of halobacteria and some lactobacilli have only a gshA gene homolog and the bacteria produce γ-Glu-Cys but no GSH (9, 10). In other bacteria GSH is generated by a fused gene encoding both the GshA and GshB activities. The fused gene and corresponding protein designated as γ-GCS-GS (11) were identified in Streptococcus agalactiae and the protein designated GshF (12) was independently identified in Listeria monocytogenes. Phylogenetic analysis has suggested that the gshA (8) and gshF (11, 12) genes have spread by horizontal gene transfer. Given the complexity of GSH distribution and biosynthesis in bacteria it follows that the biochemistry of bacterial GSTs is also predicted to be complex.

Bacterial GSTs have been less extensively studied but already have been shown to be involved in diverse chemical processes, including many involved with metabolism of xenobioic compounds (13, 14). The first bacterial GST was detected in Escherichia coli using the spectrophotometric assay with CDNB as substrate (15). Subsequently bacterial GSTs associated with the beta, chi, theta and zeta classes have been identified and GSTs of the MAPEG (membrane-associated proteins involved in ecosanoid and glutathione metabolism) class have also been determined (13). Most of these GSTs are found in proteobacteria and cyanobacteria, phyla generally found to produce GSH (16-18). The rates for bacterial GSTs are substantially lower (5-200-fold) than those of mammalian liver GSTs (19). Bacterial GSTs have been shown to catalyze a wide range of GSH-dependent activities; examples include detoxification of antibiotics such as fosfomycin (20), double bond isomerization of maleylpyruvate (21) and maleylacetoacetate (22), reductive and hydrolytic dechlorination of organic chlorides (23-25), and reduction of disulfides (26).

In contrast with the dominance of GSH in Gram negative bacteria, most Gram positive bacteria do not produce GSH (7, 27). In Actinobacteria the dominant thiol is mycothiol (MSH, Figure 1) (27) and sufficient evidence indicates that MSH has similar functions in these bacteria to the role that GSH has for Gram negative bacteria (28-30). However, no mycothiol S-transferases catalyzing MSH-dependent detoxification reactions have been described thus far. Another bacterial thiol, bacillithiol (BSH, Figure 1), has recently been found in Firmicutes and Deinococcus radiodurans (31). Much less is known about the function of this newest bacterial thiol but BSH was recently shown to be the preferred thiol substrate employed by FosB in the detoxification of fosfomycin, the first example of a bacillithiol S-transferase activity (32).

In the present study we describe the purification of a mycothiol S-transferase (MST) from Mycobacterium smegmatis and its identification as MSMEG_0887. This enzyme is related by amino acid sequence to Enterococcus faecalis EF_3021 whose structure (3cex) places it in the DinB_2 family of the DinB superfamily of DNA-damage-induced gene products (33). The DinB_2 family also includes Bacillus subtilis YfiT (1rxq). Of the 15 proteins with structures related to that of Geobacillus stearothermophilus DinB (3gor) (33) the only one having an experimentally verified function is a mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate isomerase (MDMPI) from Corynebacterium glutamicum (34, 35). Here we show that Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0443 like its homolog MSMEG_0887 is also a MST, that YfiT is a bacillithiol S-transferase (BST) and that EF_3021 is a novel DinB GST.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Mycothiol (36) and bacillithiol (32) were produced as described. Azithromycin, cerulenin, dithiothreitol, glutathione, lincomycin, mitomycin C, p-nitrophenyl acetate, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), N-α-p-tosyl-l-phenylalanylchloromethyl ketone (TPCK) and N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysinechloromethyl ketone (TLCK) were from Sigma. Antimycin A and streptozotocin were from Calbiochem, spectinomycin and methanesulfonic acid were from Fluka, and monochlorobimane was from Invitrogen. All other buffers and reagents were from Fisher except as noted.

Assay of MST Activity

Assay of MST activity during purification of MST was conducted by mixing 25 μL of sample with 25 μL of a mixture of 2 mM NADPH, 20 μM mycothiol disulfide, and 5.8 μg of mycothiol disulfide reductase in 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min to generate 20 μM MSH and reaction initiated by addition of 2.5 μL of 0.5 mM monochlorobimane in DMSO. After 30 min of reaction a 20 μL sample was quenched by mixing with 20 μL of 50 mM methanesulfonic acid in acetonitrile and heated at 60 °C for 10 min to precipitate protein. After icing for 15 min the precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 3 min in a microcentrifuge. A 25 μL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with 100 μL of 10 mM aqueous methanesulfonic acid and the mixture analyzed by HPLC. HPLC analysis was conducted using a 4.6 × 250 mm Beckman Ultrasphere C18 column with a linear gradient from 0% solvent A (0.25% aqueous acetic acid, pH4.0) to 100% solvent B (methanol) over 35 min. MST activity was calculated from the sum of the amount of MSmB (elution time 23 min) and AcCySmB (elution time 25 min) produced.

For assay of the purified MST the protocol was modified. A 75 μL aliquot containing 50 μM thiol, 100 μM DTT and 0.1 M NaCl in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.0 plus 3.2 μL of enzyme stock or buffer (control) was prewarmed at 37°C for 5 min. Reaction was initiated by addition of 2 μL of 2 mM mBCl in DMSO and incubation continued at 37°C. Reactions were sampled three times at intervals up to a maximum of 30-40 min and the 20 μL aliquot was mixed with 20 μL 50 mM methanesulfonic acid in acetonitrile. After heating the mixture at 60 °C for 10 min, icing for 15 min, and centrifuging 3 min at 13,000 × g in a microcentrifuge, 25 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 100 μL 10 mM methanesulfonic acid for HPLC analysis on a 4.6 × 250 mm Beckman Ultrasphere IP C18 column using a linear gradient from 0.25% aqueous acetic acid (pH 3.8) to 100% methanol over 35 min. Rates were calculated for each time point and were linearly extrapolated to zero time to compensate for the decline in enzyme activity with time owing to substrate depletion and enzyme inactivation. Reported values represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

Purification of M. smegmatis MST (MsMST)

M. smegmatis mc2155 was grown to late exponential phase in Middlebrook 7H9 medium containing 0.05% Tween 80 and 1% glucose and harvested by centrifugation. A 100 g wet weight cell sample was suspended in 600 mL of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 35 μM each of TPCK and TLCK. The suspension was sonicated on ice for 20 min with the temperature maintained below 16 °C and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm in a 12,000 × g for 30 min at 10 °C in a Sorvall RC5 centrifuge. Ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant (680 mL) and pellets collected at 0-20%, 20-45%, 45-65% and 65-80% saturation. Most of the activity was found in the 45-65% fraction that was taken up in 20 mL of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 35 μM TPCK and 35 μM TLCK. Bradford protein assay (Biorad) indicated a protein concentration of 5 mg/mL. After dialysis against 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 35 μM TPCK, 35 μM TLCK and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, this fraction was loaded on a 55 × 190 mm Toso-Haas DEAE 650M column and eluted with 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 35 μM TPCK, 35 μM TLCK and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol at 1.5 ml/min with a linear gradient from 1 mM to 1 M NaCl. A total of 96 20 mL fractions was collected with the MST activity eluting in 0.34-0.40 M NaCl. The fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 35 μM TPCK and 35 μM TLCK. The dialyzed sample was loaded onto a 30 × 330 mm hydroxylapatite (Biorad) column and eluted with a linear gradient from 10 mM sodium phosphate/100 mM NaCl to 200 mM sodium phosphate/0 mM NaCl at pH 6.8 in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2, 35 μM TPCK and 35 μM TLCK at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. A total of 130 20 mL fractions were collected and activity eluted at 58 – 76 mM sodium phosphate. Ammonium sulfate was added to each active fraction to 65% saturation and the protein pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 10 °C in a Sorvall RC5 centrifuge. Each pellet was solubilized in 1 mL of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, containing 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and adjacent samples were combined to generate five 2 mL samples. Each pooled sample was chromatographed on a 20 × 140 mm Sephacryl S200 gel filtration column eluted at 0.2 mL/min with 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Fractions (2.5 mL) were collected and activity was detected from fractions 56-63, corresponding to a molecular weight of ~40 kDa based upon calibration with known standards. Active MST fractions were concentrated with a Centricon 10 kDa Ultra Filter to ~200 μL Glycerol was added to 10% and the samples stored at -70 °C.

Identification, Cloning and Expression of M. smegmatis MST

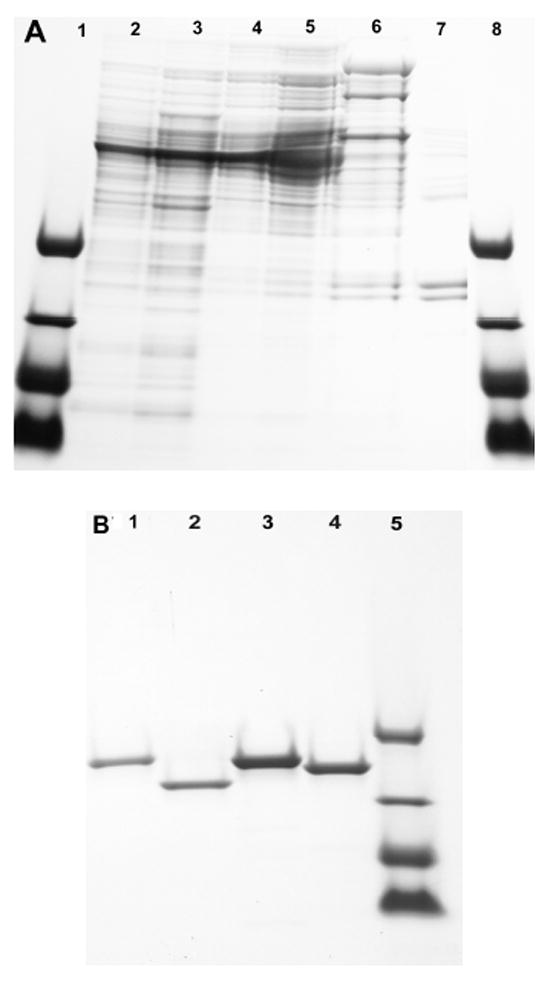

The peak of MST activity on the Sephacryl S200 column eluted in fraction 59 and produced two major protein bands at ~20 kDa on a 10-20% Tris-Tricine Criterion (Biorad) SDS gel (Figure 2A, lane 7). The two major bands at ~20 kDa were identified by the UCSD Molecular Proteomics Laboratory using an in gel digest with trypsin and sequencing by tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry as previously described (37). The upper band was identified by 19 peptides (95% confidence) with 71% sequence coverage as MSMEG_1680 which is annotated as a conserved hypothetical protein, is found in a limited group of mycobacterial strains and was not pursued. The lower band was identified by 19 peptides (95% confidence) with 88% sequence coverage as MSMEG_0887, a member of the DinB superfamily found in most Gram-positive bacteria. The M. smegmatis mst (MSMEG_0887) gene was codon optimized for expression in E. coli and synthesized by GenScript. The synthetic gene was subcloned into pET28a using NdeI and XhoI cloning sites generating a thrombin cleavable N-terminal His6-tagged protein. E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) was transformed with the pET28a-Msmst expression vector. MsMST was produced in Luria Broth containing kanamycin (30 μg/ml) and 1 mM IPTG at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. The cells were lysed by sonication and the cell free extract was purified on a Zn-liganded PrepEase (USB) His6-tagged protein purification kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MsMST was eluted in 100 mM imidizole and was concentrated on a Centricon 10 (10 kDa) ultrafilter. The buffer was exchanged on the ultrafilter with 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; 10% glycerol was added prior to storage at -70 °C. MsMST was >90% pure based upon analysis on 10-20% Tris-Tricine Criterion (Biorad) SDS gel analysis (Figure 2B, lane 1). Protein concentration was estimated using the calculated A280 value of 1.78 for a 1 mg per ml concentration (ProtParam tool at http://ca.expasy.org).

Figure 2.

10-20% Gradient SDS PAGE gel of MST proteins. (A) MST purification: lanes 1 and 8, polypeptide standards containing triosphosphate isomerase (26.6 kDa), myoglobin (17 kDa), α-lactalbumin (14.4 kDa) and aprotinin (6.5 kDa); lane 2, crude extract of M. smegmatis mc2155 protein; lane 3, 45-65% ammonium sulfate fraction; lane 4, DEAE peak fraction; lane 5, DEAE activity pool; lane 6, hydroxylapatite activity pool; lane 7, gel filtration peak fraction. (B) MST cloned proteins: lane 1, recombinant purified MsMST; lane 2, recombinant purified MtMST; lane 3, recombinant purified B. subtilis BsBST (YfiT); lane 4, recombinant purified E. faecalis EfGST; lane 5, polypeptide standards as for Figure 2A.

Cloning and Expression of M. tuberculosis mst (Rv0443) and Enterococcus faecalis gst (EF_3021)

The Rv0443 gene was amplified from M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA using forward (CATATG-ATGGCAAGCACCGAC) and reverse (AAGCTT-GGCTATCCCCCGCAGGTA) primers with the forward primer containing an Nde1 restriction site and the reverse primer having a HindIII restriction site for cloning into pet22B. The amplified fragment was first cloned into TA cloning vector pcr2.1 and the resulting plasmid was digested with Nde1/HindIII. The insert was ligated to a similarly digested pet22B vector followed by transformation into E. coli BL-21 DE3 strain. The strain harboring the recombinant pet22B vector was induced for 4-6 h at 37 °C with 0.5 mM IPTG and the culture was refrigerated overnight. The pelleted cells were sonicated and centrifuged; the supernatant was applied to a PrepEase Zn affinity column that was washed and eluted with 250 mM imidazole according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The eluted protein was desalted on a Sephadex 25 column and stored at -70 °C in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol. The purified MtMST produced a single band on SDS gel electrophoresis (Figure 2B, lane 2). The E. faecalis gst was amplified from E. faecalis ATCC 19433 genomic DNA using the forward primer CATATG-ATGAAAGTCACTCAA and the reverse primer AAGCTT-TTTTCCAATGACTAATCT, expressed and purified according to the protocol described for MtMST. SDS gel electrophoresis of the purified protein produced a single band (Figure 2B, lane 4). Protein concentration was based upon an A280 value of 1.93 per mg mL-1 calculated for both the M. tuberculosis and the E. faecalis enzymes (http://ca.expasy.org).

Bacillithiol S-Transferase (BST) Production and Assay of Activity

A clone of Bacillus subtilis YfiT was kindly provided by Wayne F. Anderson (Northwestern University) and used to produce His6-tagged Yfit (38). The protein was expressed in Luria Broth containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37 °C. The protein was purified as described for MsMST over a Zn PrepEase affinity column and was shown to be >90% pure by SDS gel electrophoresis (Figure 2B, lane 3). BsBST was shown to be active with BSH when assayed as described above for purified MST. Protein concentration was estimated using A280 = 2.1 per mg mL-1 (http://ca.expasy.org).

Survey of BsMST, BsBST and EfGST substrate specificity

Except as noted below, the survey of substrate activity was conducted at 23 °C and 0.15 mM each of thiol and substrate in 0.1 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.0; the reaction was followed at 5 min intervals by titration of 50 μL aliquots by addition to an equal volume of 0.4 mM DTNB in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and determination of the ΔA412 value. Rates were calculated using ε412 = 14.1 (39) after correcting for background rates measured in controls lacking enzyme or lacking substrate and represent the mean and standard error of at least three determinations.

The rates with CDNB were determined at 1 mM CDNB and 1 mM thiol by the method of Habig and Jakoby (40). The rates with p-nitrophenyl acetate were determined at 400 nm in 0.1 M NaCl and 25 mM HEPES pH 7.0 with 0.15 mM thiol and 0.15 mM p-nitrophenyl acetate as previously described (40). The rate for MsMST with mitomycin C (100 μM) was determined with 200 μM MSH at 37 °C in 0.1 M NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.0 following the loss of mitomycin C by HPLC analysis. Reactions (250 μL) were sampled by mixing 50 μL with 50 μL of acetonitrile containing 50 mM methanesulfonic acid. The sample was heated at 60 °C for 10 min, iced, and then centrifuged for 5 min at 13000 × g to remove protein. The supernatant was dried in a Speed Vac and resuspended in 0.1% TFA-water for HPLC analysis. Mitomycin C was assayed by HPLC with monitoring at 360 nm using a linear gradient from 0-100% B over 40 min (0.05% TFA-water, A buffer; acetonitrile, B buffer). The 4.6 × 250 mm Beckman Ultrasphere IP C18 column was operated at 23 °C and 1 ml per min. Mitomycin C eluted at 12.5 min and the product eluted at 13.8 min. The rate for BsBST with cerulenin (200 μM) was determined with 200 μM BSH at 37 °C in 0.1 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.3 following the loss of cerulenin by HPLC analysis. Cerulenin was assayed by HPLC monitored at 220 nm using the method described above for mitomycin C except that buffer A was 0.1% TFA-water and buffer B was methanol. Cerulenin eluted at 32.2 min and the product at 27.5 min.

RESULTS

Assay for MST Activity

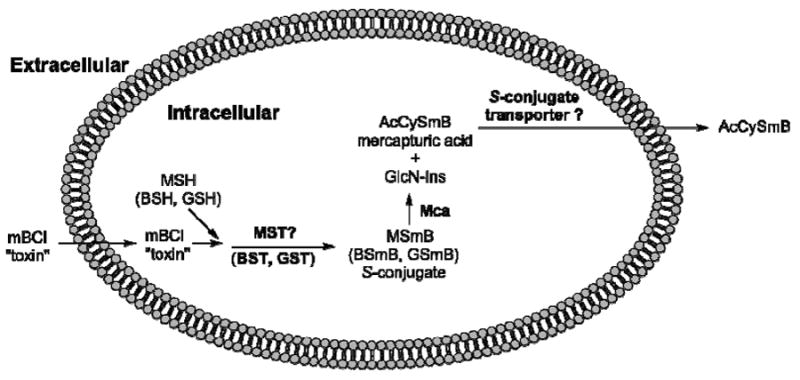

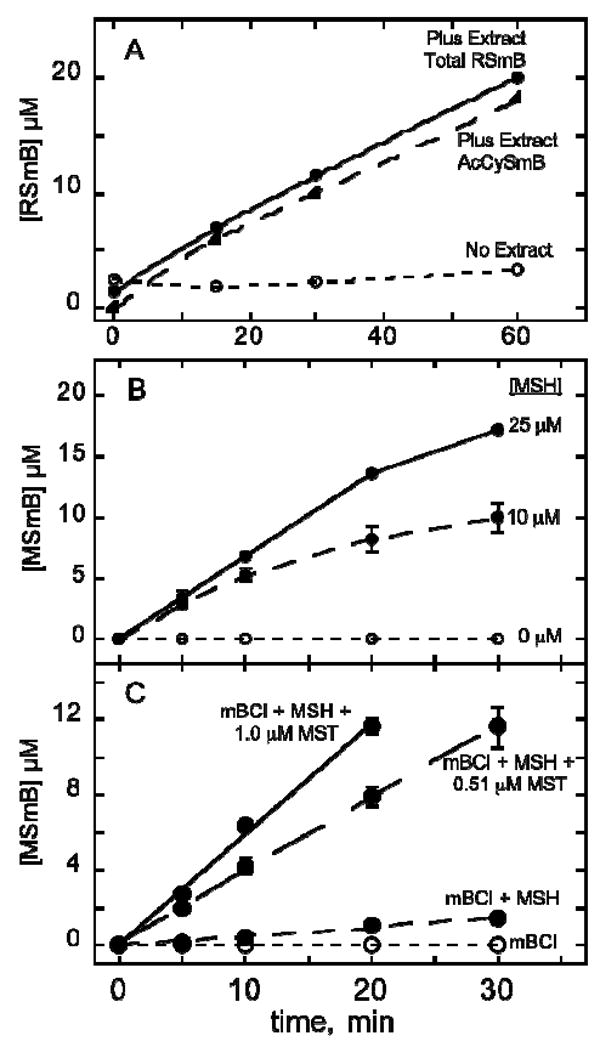

Monochlorobimane (mBCl) was found to be a useful reagent for estimating cellular GSH levels because the chemical reaction of mBCl with GSH to produce fluorescent GSmB is slow at physiological pH but is catalyzed by cellular GSTs causing cells to become fluorescent (41, 42). However, variation in GST activity between different mammalian cell lines can complicate the quantitation (43). Treatment of a M. smegmatis cell suspension with mBCl also produces fluorescence in both the extracellular and intracellular compartments. This results from the reaction of MSH with mBCl to produce fluorescent MSmB, analogous to the previously demonstrated process with the more reactive monobromobimane (44). The speed of the reaction with mBCl implied the presence of an MST catalyzing the reaction with MSH to produce MSmB (Figure 3). MSmB is rapidly cleaved by mycothiol S-conjugate amidase (Mca) to generate the bimane derivative of N-acetylcysteine (AcCySmB, fluorescent), a mercapturic acid that is excreted from the cell (Figure 3), as established by independent HPLC analysis of the cellular and extracellular fractions (data not shown, see ref (44) for the analogous process with monobromobimane). This process can also be observed in dialyzed cell-free extracts of M. smegmatis. Combining cell extract with a mixture of mBCl and MSH led to the production of a large amount of AcCySmB and only a small amount of MSmB as determined by HPLC (Figure 4A). The sum of AcCySmB and MSmB, designated RSmB, represents the activity of MST catalyzing the production of MSmB. This assay was used to purify the MST activity from M. smegmatis.

Figure 3.

Thiol detoxification scheme showing production of thiol S-conjugates (MSmB, BSmB, GSmB) catalyzed by S-transferases (MST, BST, GST), cleavage of MSmB by mycothiol S-conjugate amidase (Mca) to generate mercapturic acid AcCySmB and GlcN-Ins. The former is exported from the cell, possibly mediated by a putative S-conjugate transporter, and the latter is utilized for resynthesis of MSH (44).

Figure 4.

MST catalyzed conversion of mBCl plus MSH to MSmB. (A) Assay used to purify MST activity from M. smegmatis involving reaction of 20 μM MSH (generated and maintained as described in Materials and Methods) with 25 μM mBCl as catalyzed by crude extract diluted five-fold. The main product is AcCySmB generated from MSmB (present at low steady-state level of 1-2 μM) by mycothiol S-conjugate amidase (Mca) that has high activity in the extract (44). (B) Activity of MsMST (0.51 μM) from cloned and expressed MSMEG_0887 as a function of MSH concentration with 50 μM mBCl and 0.51 μM MsMST. (C) Activity with increasing MsMST concentration at 25 μM MSH and 50 μM mBCl. Data for B and C represent the mean of triplicate determinations. Error bars show standard deviation when larger than the symbol. Experimental details are given in Material and Methods.

Purification and identity of MST from M. smegmatis

A cell-free extract of M. smegmatis was fractionated with ammonium sulfate and the 45-65% ammonium sulfate fraction found to contain the majority of the MST activity. This fraction was dialyzed and further purified by chromatography on DEAE-650M, followed by chromatography on hydroxylapatite. Final purification by size exclusion chromatography on Sephacryl S200 indicated that the native protein was ~40 kDa. Following the gel filtration step the Mca activity was separated and the product of the assay was solely MSmB. The purified MST was analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis (Figure 2A, lane 7). The lower major band at ~20 kDa was identified by high-resolution mass spectrometry as MSMEG_0887 and confirmed as MsMST by cloning (see below). Its monomer molecular weight of 20,383 together with native protein size indicates that the active protein is a dimer.

Cloning and Expression of MSMEG_0887 Confirms Assignment as MsMST

The MSMEG_0887 gene was cloned and expressed in pET28a as a N-terminal His6-tagged protein and affinity purified to generate MsMST producing a single band on SDS gel electrophoresis (Figure 2B, lane 1). Purified MsMST exhibited substantial activity with 50 μM mBCl in the presence of an equal concentration of MSH but produced no detectible activity in the presence of BSH or GSH (Table 1). MsMST produces only MSmB from MSH and mBCl in a mycothiol dependent (Figure 4B) and protein dependent (Figure 4C) manner. This enzyme activity facilitates the production of mycothiol S-conjugates which are cleaved by mycothiol S-conjugate amidase to generate a mercapturic acid that can be excreted from the cell, Figure 3 (44). It is therefore a key enzyme in the mycobacterial defense against cellular toxins.

Table 1.

Activities of thiol S-transferases with 50 μM mBCl and 50 μM thiol.

| Enzyme | Thiol | Activity (nmol min-1 mg-1) |

|---|---|---|

| MsMST | MSH | 340 ± 36 |

| BSH | <2 | |

| GSH | <0.7 | |

| MtMST | MSH | 83 ± 10 |

| BSH | <0.4 | |

| GSH | <0.4 | |

| BsBST | MSH | <0.4 |

| BSH | 2.5 ± 0.4 | |

| GSH | <0.4 | |

| EfGST | MSH | <0.04 |

| BSH | <0.04 | |

| GSH | 0.4 ± 0.06 |

Rv0443 is the MST of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The gene encoding the MST of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtMST) was identified as Rv0443 whose product has 77% sequence identity to MsMST. Rv0443 was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli BL3 DL21 as a N-terminal His6-tagged protein and purified on a zinc affinity column to generate pure protein (Figure 2B, lane 2). MtMST was highly active toward mBCl with MSH but activity with BSH or GSH was at least 200-fold lower (Table 1).

Bacillus subtilis YfiT is a Bacillithiol S-Transferase (BST)

A search of the pfam website at pfam.sanger.ac.uk with the MsMST sequence revealed that it is a member of DUF664 (PF04978), an uncharacterized family of potential enzymes of the DinB superfamily. The later is comprised of eight families and includes 30 proteins with reported crystal structures, many from organisms known to produce BSH rather than MSH (31). The expression vector for one of these (1rxq, B. subtilis yfit) was kindly provided by Wayne F. Anderson of Northwestern University. The purified protein (Figure 2B, lane 3) was assayed with mBCl and showed substantial activity with BSH but at least 60-fold lower activity with MSH and GSH (Table 1). Thus, B. subtilis YfiT is identified as a bacillithiol S-transferase and redesignated BsBST. BsBST is a member of the DinB_2 (PF12867) family of the DinB superfamily (pfam.sanger.ac.uk).

Identification of EF_3021 as a Glutathione S-Transferase (GST)

A search of the GenBank data base with the MsMST sequence identified numerous homologs among MSH producing Actinobacteria but also identified a gene in Enterococcus faecalis V583 (EF_3021) encoding a protein with 34% identity to MsMST. Since E. faecalis produces GSH but not MSH or BSH (31) we undertook the cloning and expression of this gene. Assay of the purified protein (Figure 2B, lane 4) with mBCl showed low but definite activity with GSH but at least 10-fold lower activity with MSH and BSH (Table 1). Based upon this we assign EF_3021 as the glutathione S-transferase EfGST. Like BsBST, EfGST belongs to the DinB_2 (PF12867) family of the DinB superfamily and has no homology to other bacterial GST proteins.

Substrate Specificity of MsMST, BsBST and EfGST

A survey of potential substrates was undertaken using MsMST, BsBST and EfGST (Table 2). The data should be viewed only as qualitative indicators of possible activity since conditions vary widely between different assays. Also, all of these S-transferases were isolated as His6-tagged proteins and it is possible that the presence of the His6-tag has influenced their activity. The most commonly used substrate for measurement of GST activity is CDNB (40) and both MsMST and BsBST gave positive assays with this substrate using MSH and BSH, respectively. However, EfGST failed to give detectible GSH-dependent activity in this assay.

Table 2.

Activity of MsMST, BsBST and EfGST with various substrates.

| Substrate | Enzyme Activity (nmol min-1 mg-1)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MsMST | BsBST | EfGST | |

| mBClb | 340 ± 36 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.06 |

| CDNB | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 54 ± 4 | ≤0.03 |

| CuOOH | <3c | 5 ± 2 | <2c |

| H2O2 | <2c | <80c | <2c |

| Cerulenin | <1c | 40 ± 9 | <0.2c |

| Mitomycin C | 17 ± 3 | <1c | ndd |

Determined as described in Materials and Methods except as noted.

From Table 1.

Detection of activity limited by the indicated rate of the control reaction lacking enzyme.

Not determined.

The only previously reported activity for BsBST (YfiT) was an esterase activity (results not shown) with p-nitrophenyl acetate in the absence of thiol (38). Esterase activity with p-nitrophenyl acetate was observed with MsMST (6.5 ± 0.1 nmoles min-1mg-1), EfGST (2.0 ± 0.1 nmoles min-1mg-1) and BsBST (4.4 ± 0.4 nmoles min-1mg-1) in the absence of thiol. The respective addition of 0.15 mM MSH, GSH, or BSH did not significantly increase the rate.

Some bacterial GSTs have activity with peroxides (13, 45) but neither MsMST nor EfGST gave measurable rates with CuOOH or H2O2 (Table 2). BsBST produced a low but significant rate with CuOOH that was above the control value. However, the control rate without enzyme was very high for H2O2. This suggests that BSH alone, or complexed with a suitable metal ((31) and unpublished results), may function together with a bacillithiol disulfide reductase (currently unidentified) to protect B. subtilis against peroxide toxicity. BsBST, but neither MsMST or EfGST, exhibited significant activity with the antibiotic cerulenin produced by the fungus Sarocladium oryzae (46). Other antibiotics, including antimycin A, azithromycin, lincomycin, spectinomycin and streptozocin, had little or no detectable activity (<2 nmol min-1 mg-1) with the three S-transferases in the thiol depletion assay. For BsBST the result was similar with rifamycin S but higher limits were obtained with MsMST (< 6 nmol min-1 mg-1) and EfGST (< 4 nmol min-1 mg-1) owing to higher control rates for the uncatalyzed reaction.

The positive assays for MsMST with mitomycin C and for BsBST with cerulenin indicate that antibiotic detoxification may be a function of these S-transferases. A more detailed survey of native substrates and the detailed kinetics of these reactions will have to await the preparation and isolation of the native form of these enzymes.

Phylogenetic Analysis of MsMST, BsBST and EfGST Homologs

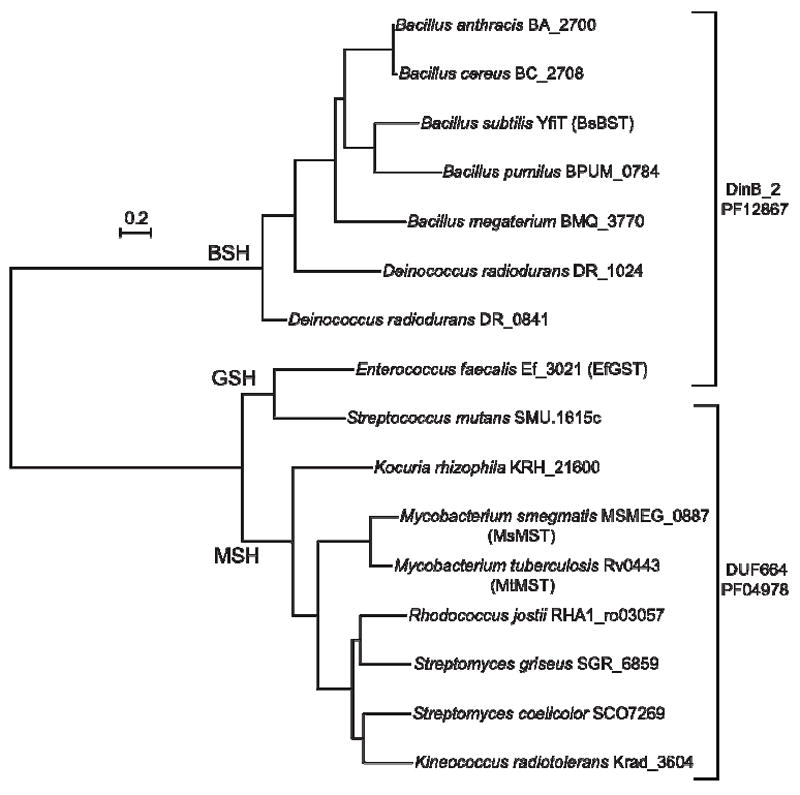

The DinB superfamily is comprised of eight families, all but one of which have been labeled domains of unknown function (DUF) (pfam.sanger.ac.uk). One family is designated MDMPI_N (pfam11716) based upon the identification of one member as a mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate isomerase (MDMPI) in Corynebacterium glutamicum (34) and subsequent determination of its structure (35). To elaborate the relationship between MDMPI and the enzymes identified here we searched the GenBank database for sequence homologs of MsMST, BsBST and EfGST. Results were limited to those organisms for which low-molecular-weight thiol analyses were available (27, 31, 47, 48) and a phylogenetic tree was generated for representative species (Figure 5). The S-transferase sequences fall into three groups associated with the major low-molecular-weight thiol found in the organism. The organisms that produce MSH belong to the DUF664 family of the DinB superfamily (pfam.sanger.ac.uk).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of selected S-transferase sequences. Branches are labeled with the thiol that the bacteria of the group are known to produce. Proteins belonging to the DinB_2 and DUF664 families are designated by brackets.

The proteins related to BsBST (YfiT) are members of the DinB_2 family (PF12867) of the DinB superfamily (Figure 5, pfam.sanger.ac.uk) and are produced in bacteria known to generate bacillithiol. It should be noted that FosB, the previously identified example of a BST (32), is not a member of the DinB superfamily. The two GST sequences belong to different families, the EfGST assigned to DinB_2 but the Streptococcus mutans enzyme is categorized with DUF664.

The three families that have been found to include thiol-dependent biochemical processes (MDMPI_N, DUF664, DinB_2) contain 69% of the total sequences assigned to the DinB superfamily.

On the function of DinB superfamily proteins

The one demonstrated physiologic function of a DinB superfamily protein is for C. glutamicum MDMPI that plays an essential role in the metabolism of gentisate and other aromatic compounds (34, 35, 49). Substantial primary sequence homologs are found in many Actinobacteria and likely have the same function. Other members of the MDMPI_N family have lower primary sequence homology and their function remains to be established.

B. subtilis YfiT (BsBST) structure (1rxq) is an example of a DinB crystal structure that was probably of early interest due to it genome context. In the B. subtilis genome yfiT is flanked by genes encoding efflux transport proteins. Orthologs of yfiS in Bacilli are annotated (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, KEGG) as macrolide transport proteins (http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?bsu:BSU08380) and orthologs of yfiU are annotated as multi-drug-resistance transporter or drug resistance transporters (http://ssdb.genome.jp/ssdb-bin/ssdb_best?org_gene=bsu:BSU08400). The efflux transporters for mercapturic acids in MSH-producing species (Figure 3 and reference (29)) and for cysteine S-conjugates in BSH-producing species have not been identified but yfiS and yfiU are candidate genes for these transporters. The genome context of yfiT is consistent with its proposed function in the detoxification of antibiotics. Thus, the genome context of yfiT as well as the results of Table 2 are consistent with the hypothesis that antibiotic detoxification is a physiological function of BsBST.

The DinB superfamily as determined by structural parameters (SCOP, http://sufam.cs.bris.ac.uk/SUPERFAMILY/) appears to be much larger than simple sequence searches suggest and the variation of DinB protein content with genera provides some support for their involvement with antibiotics. The DinB superfamily is overrepresented in the genomes of the Bacillales (9.1 sequences per species/strain) and Actinobacteria (9.3 sequences per species/strain) relative to the Proteobacteria (1.9 sequences per species/strain) and other genomes (pfam.sanger.ac.uk). The content is particularly high in those bacteria known to produce secondary metabolites. The secondary metabolite biosynthesis potential of marine actinomycetes has been assessed by the number of polyketide synthesis (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthesis (NRPS) operons found in the genome (50). Taking the secondary metabolite potential as the total of the PKS and NRPS genes found in the NCBI database for bacteria, we find a significant correlation between the content of genes encoding DinB proteins and the secondary metabolite potential (Table S1). In the Firmicutes the bacilli have up to 22 genes for DinB proteins per species and are rich in PKS and NRPS secondary metabolite synthesis genes. The Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus genera have genes encoding only 1 or 2 DinB proteins and 1 or 2 genes for secondary metabolites. The largest numbers of genes (20-38 per species) encoding DinB proteins occur in the Actinobacteria which also contain the largest number of PKS plus NRPS genes, 24-66 per species. Especially notable are Amycolatopsis mediteranei, a rifamycin producer with 38 DinB protein encoding genes, and Saccharopolyspora erythraea, an erythromycin producer with 34 such genes, correlating with 29 and 33 PKS plus NRPS genes, respectively. It is interesting that M. tuberculosis, an obligate human pathogen, has 11 DinB encoding genes, about half of what is found in M. smegmatis, a soil bacterium. The lowest number of genes for DinB proteins (1-4) among Actinobacteria are found in Kocuria rhizophila, Micrococcus luteus, and Rubrobacter xylanophilus which have only 1 or 2 secondary metabolite genes. The apparent correlation of DinB genes with secondary metabolite genes suggests that these proteins may function in the production of secondary metabolites, or in self-protection against toxic effects of these metabolites, rather than in protection against secondary metabolites produced by other competing bacteria in the environment.

The small number of DinB proteins encoded by Proteobacterial genomes, and in those of the green sulfur and green non-sulfur bacteria, correlates with the few PKS or NRPS genes present in these bacteria. Exceptions include the Gram-negative bacteria Nostoc muscorum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with only one or two genes for DinB proteins and multiple PKS and NRPS genes (Table S1). N. muscorum (51) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19) have the canonical CDNB-utilizing GST that may function in place of DinB enzymes related to EfGST.

DISCUSSION

The identification of four new thiol-dependent S-transferase enzymes as members of the DinB superfamily substantially expands our understanding of this large and important group of proteins. As pointed out previously (52) the DinB superfamily proteins are not to be confused with the E. coli dinB encoded type IV DNA polymerase and homologous enzymes that are involved in error prone DNA repair (53, 54). The first DinB superfamily protein to have a function assigned was the mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate isomerase from C. glutamicum (34, 35) and this defines the MDMPI_N family. The MDMPI_N family currently includes 779 sequences from 144 species/strains (pfam.sanger.ac.uk), nearly all from Actinobacteria where MSH has been generally found to be the dominant low-molecular-weight thiol. The primary sequences of these proteins have only distant homology to that of MsMST but like other DinB proteins (52) MDMPI has a binding site for divalent metals (35).

The finding that MsMST and MtMST belong to the DUF664 (PF04978) family (Figure 5) provides the first identification of function for this family. Both proteins recognize mBCl as substrate and are specific for MSH as the thiol cofactor (Table 1) while MsMST was also shown to have activity with CDNB and Mitomycin C (Table 2). The activities are modest compared with those for other bacterial GSTs (6, 45) but sufficient to establish the validity of the catalytic activity. Quantitative assessment of these MSTs will have to await preparation of the native forms for the enzymes. Close homologs (>65% identity) are found in all mycobacterial genomes with the exception of that for Mycobacterium leprae and substantial homologs (>40% identity) are found in about half of 88 genomes for other Actinobacteria. There can be little doubt that these proteins also have MSH-dependent enzyme activities. The DUF664 family includes 453 sequences from 186 species/strains, ~70% of which are Actinobacteria and most of the remainder are Bacilli (pfam.sanger.ac.uk). It seems likely that many of the proteins encoded by these genes are also MSH-dependent enzymes. The M. smegmatis genome contains two other members of the DUF664 family (MSMEG_1356 and MSMEG_3923) that share 27% primary sequence identity but are only 16% identical to the MsMST (MSMEG_0887) sequence. It is possible that these two related proteins are also MSH-dependent enzymes but this needs to be established experimentally.

BsBST (Yfit) belongs to the DinB_2 family (PF12867) and has BSH-specific S-transferase activity but how good a model is it for other DinB_2 family proteins? This family contains 2153 sequences from 735 species, of which ~50% are Firmicutes, ~14% Proteobacteria, and ~10% each Actinobacteria and Bacteriodetes (pfam.sanger.ac.uk). Close primary sequence homologs of BsBST are found in most members of the Class Bacilli and in several species of Deinococci so it seems likely that these are BSH-dependent enzymes. More distant homologs are present in the Thermaceae the strongest found in the genome of Meiothermus silvanus (Mesil_2528) but thiol analyses have not been conducted on members of this Order so whether they produce BSH is uncertain. More surprising was the finding of strong homologs of BsBST among the Bacteroidetes, including in ~60% of the completed genomes of Flavobacteria, Sphingobacteria and Cytophagia. The thiols produced by these bacteria have not been studied but those Bacteroidetes with strong BsBST homologs also have strong homologs of the B. subtilis protein YllA proposed to encode BshC, the BSH synthase (55), so it seems likely that these bacteria are capable of producing BSH. It would thus appear that a substantial portion of the DinB_2 family proteins could prove to be BSH-dependent enzymes.

The novel GST enzyme identified here in E. faecalis appears to have substantially more restricted distribution than MST or BST. The genomes of S. mutans and E. faecalis contain a gene that encodes an unusual protein that catalyzes both steps of GSH biosynthesis, designated either GSHF (12) or γ-GCS-GS (11). The fused gene for GSH synthesis appears in the genomes of diverse Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria suggesting that it was spread by lateral gene transfer (11, 12). However, of the 13 Gram-positive bacteria other than E. faecalis identified as having the gshF (gshAB) gene only the S. mutans genome encodes a protein (SMU.1615c) with substantial homology to EfGST (Figure 5). There are weaker homologs of EfGST in bacteria producing MSH and identified as MSTs but it seems clear that this unusual GST has only a very limited distribution.

About three-quarters of these sequences contain only the DinB domain while the others contain one or more additional domains of varying type. In addition to BsBST, the B. subtilis genome has two additional sequences belonging to the DinB_2 family, YkkA (BSUU13070) and YuaE (BSU32030), containing only the DinB_2 domain. The sequences of YkkA and YuaE are only 12% identical, as are those of BsBST (YfiT) and YkkA, whereas the sequences of BsBST and YuaE are 14% identical. Whether these two additional B. subtilis sequences assigned to the DinB_2 family are also BSH-dependent proteins requires experimental verification.

The crystal structure of BsBST (YfiT, 1rxq) provides some insights as to how this protein may function. YfiT (BsBST) was crystallized as a dimer with the Ni binding site facing away from the dimmer interface and towards the solvent (38). The Ni could be readily exchanged with Zn by dialysis and we assume the Zn form is the native form of the enzyme. In MshC Zn binds the cysteine sulfhydryl in the mycothiol ligase reaction that links Cys with GlcN-Ins producing Cys-GlcN-Ins, an intermediate in MSH biosynthesis (56, 57). The Zn ligand in YfiT (BsBST) is a possible binding site for the cysteine sulfhydryl of bacillithiol. Rajan, et al. (38) note that the metal binding site is surrounded within 10 Å by 3 pairs of hydrophobic amino acids (Tyr8 and Tyr93, Tyr54 and Tyr157, and Trp59 and Trp 159) that may define a hydrophobic binding site for aromatic xenobiotics. These amino acids are fully conserved in the proteins of the BSH branch of Figure 5 with the exception of DR_1024 where the positions corresponding to Tyr93 and Tyr157 have Ala in place of Tyr. The hydrophobic site generated by these residues could provide a binding site for hydrophobic substrates such as mBCl, CDNB, CuOOH and cerulenin (Table 2).

CONCLUSIONS

In this work we have identified three new types of S-transferase enzymes that involve three different thiol cofactors. These include the first mycothiol S-transferase to be reported, a bacillithiol S-transferase unrelated to FosB, recently reported to have BST activity, and a glutathione S-transferase unrelated to the superfamily of known GSTs. These enzymes belong to two families (DinB_2 and DUF664) of the DinB superfamily that also includes the MDMPI_N family previously shown to have mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate isomerase activity. These three families include more than two-thirds of the sequences comprising the DinB superfamily indicating that thiol-dependent metabolic and detoxification processes represent a major activity of this superfamily. The full range of natural substrates for these enzymes remains to be determined. Such studies will not be pursued in the Fahey laboratory that was recently closed but it is hoped that the present study provides key insights and methods to aid such studies by our collaborators and other investigators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wayne F. Anderson for a gift of the YfiT expression clone, Russell Doolittle for assistance with the phylogenetic analysis and Philong Ta for conducting preliminary experiments with mBCl.

Funding Sources This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI072133 and by Academic Senate Grant CHE168G from the University of California, San Diego to RCF and National Institutes of Health Grant GM061223 to MR.

Abbreviations

- BSH

bacillithiol

- BST

bacillithiol S-transferase

- CDNB

1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GSH

glutathione

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- mBCl

monochlorobimane

- MSH

mycothiol

- MDMPI

mycothiol-dependent maleylpyruvate S-transferase

- MST

mycothiol S-transferase

- TLCK

N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysinechloromethyl ketone

- TPCK

N-α-p-tosyl-l-phenylalanylchloromethyl ketone

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Supplementary Table S1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Eaton DL, Bammler TK. Concise review of the glutathione Stransferases and their significance to toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 1999;49:156–164. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/49.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frova C. Glutathione transferases in the genomics era: new insights and perspectives. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:149–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josephy PD, Mannervik B. Molecular Toxicology. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. Glutathione transferases; pp. 333–364. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark AG, Smith JN, Speir TW. Cross specificity in some vertebrate and insect glutathione-transferases with methyl parathion (dimethyl p-nitrophenyl phosphorothionate), 1-chloro-2,4-dinitro-benzene and s-crotonyl-N-acetylcysteamine as substrates. Biochem J. 1973;135:385–392. doi: 10.1042/bj1350385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stourman NV, Branch MC, Schaab MR, Harp JM, Ladner JE, Armstrong RN. Structure and function of YghU, a nu-class glutathione transferase related to YfcG from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1274–1281. doi: 10.1021/bi101861a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahey RC, Brown WC, Adams WB, Worsham MB. Occurrence of glutathione in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:1126–1129. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.3.1126-1129.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copley SD, Dhillon JK. Lateral gene transfer and parallel evolution in the history of glutathione biosynthesis genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0025. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-research0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malki L, Yanku M, Borovok I, Cohen G, Mevarech M, Aharonowitz Y. Identification and characterization of gshA, a gene encoding the glutamate-cysteine ligase in the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5196–5204. doi: 10.1128/JB.00297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton GL, Javor B. gamma-Glutamylcysteine and thiosulfate are the major low-molecular-weight thiols in halobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:438–441. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.438-441.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janowiak BE, Griffith OW. Glutathione synthesis in Streptococcus agalactiae. One protein accounts for gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and glutathione synthetase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11829–11839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopal S, Borovok I, Ofer A, Yanku M, Cohen G, Goebel W, Kreft J, Aharonowitz Y. A multidomain fusion protein in Listeria monocytogenes catalyzes the two primary activities for glutathione biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3839–3847. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3839-3847.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allocati N, Federici L, Masulli M, Di Ilio C. Glutathione transferases in bacteria. FEBS J. 2009;276:58–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vuilleumier S, Pagni M. The elusive roles of bacterial glutathione S-transferases: new lessons from genomes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;58:138–146. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0836-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shishido T. Glutathione S-Transferase from Escherichia coli. Agric Biol Chem. 1981;45:2951–2953. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahey RC, Buschbacher RM, Newton GL. The Evolution of Glutathione Metabolism in Phototrophic Microorganisms. J Mol Evol. 1987;25:81–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02100044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahey RC, Newton GL. Occurrence of low molecular weight thiols in biological systems. In: Larsson A, Orrenius S, Holmgren A, Mannervik B, editors. Functions of Glutathione: Biochemical, Physiological, Toxicological and Clinical Aspects. Raven Press; New York: 1983. pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton GL, Fahey RC. Glutathione in Procaryotes. In: Viña J, editor. Glutathione: Metabolism and Physiological Functions. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1989. pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccolomini R, Di Ilio C, Aceto A, Allocati N, Faraone A, Cellini L, Ravagnan G, Federici G. Glutathione transferase in bacteria: subunit composition and antigenic characterization. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:3119–3125. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-11-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arca P, Hardisson C, Suarez JE. Purification of a glutathione S-transferase that mediates fosfomycin resistance in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:844–848. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang T, Li DF, Zhou NY. Identification and clarification of the role of key active site residues in bacterial glutathione S-transferase zeta/maleylpyruvate isomerase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anandarajah K, Kiefer PM, Jr, Donohoe BS, Copley SD. Recruitment of a double bond isomerase to serve as a reductive dehalogenase during biodegradation of pentachlorophenol. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5303–5311. doi: 10.1021/bi9923813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Federici L, Masulli M, Di Ilio C, Allocati N. Characterization of the hydrophobic substrate-binding site of the bacterial beta class glutathione transferase from Proteus mirabilis. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2010;23:743–750. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiefer PM, Jr, Copley SD. Characterization of the initial steps in the reductive dehalogenation catalyzed by tetrachlorohydroquinone dehalogenase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1315–1322. doi: 10.1021/bi0117504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vuilleumier S, Ivos N, Dean M, Leisinger T. Sequence variation in dichloromethane dehalogenases/glutathione S-transferases. Microbiology. 2001;147:611–619. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-3-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xun L, Belchik SM, Xun R, Huang Y, Zhou H, Sanchez E, Kang C, Board PG. S-Glutathionyl-(chloro)hydroquinone reductases: a novel class of glutathione transferases. Biochem J. 2010;428:419–427. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton GL, Arnold K, Price MS, Sherrill C, delCardayré SB, Aharonowitz Y, Cohen G, Davies J, Fahey RC, Davis C. Distribution of thiols in microorganisms: Mycothiol is a major thiol in most actinomycetes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1990–1995. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1990-1995.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jothivasan VK, Hamilton CJ. Mycothiol: synthesis, biosynthesis and biological functions of the major low molecular weight thiol in actinomycetes. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:1091–1117. doi: 10.1039/b616489g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton GL, Buchmeier N, Fahey RC. Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:471–494. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawat M, Av-Gay Y. Mycothiol-dependent proteins in actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31:278–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton GL, Rawat M, La Clair JJ, Jothivasan VK, Budiarto T, Hamilton CJ, Claiborne A, Helmann JD, Fahey RC. Bacillithiol is an antioxidant thiol produced in Bacilli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:625–627. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma SV, Jothivasan VK, Newton GL, Upton H, Wakabayashi JI, Kane MG, Roberts AA, Rawat M, La Clair JJ, Hamilton CJ. Chemical and Chemoenzymatic Syntheses of Bacillithiol: A Unique Low-Molecular-Weight Thiol amongst Low G + C Gram-Positive Bacteria. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:7101–7104. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper DR, Grelewska K, Kim CY, Joachimiak A, Derewenda ZS. The structure of DinB from Geobacillus stearothermophilus: a representative of a unique four-helix-bundle superfamily. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:219–224. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109053913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng J, Che Y, Milse J, Yin YJ, Liu L, Ruckert C, Shen XH, Qi SW, Kalinowski J, Liu SJ. The gene ncgl2918 encodes a novel maleylpyruvate isomerase that needs mycothiol as cofactor and links mycothiol biosynthesis and gentisate assimilation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10778–10785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang R, Yin YJ, Wang F, Li M, Feng J, Zhang HM, Zhang JP, Liu SJ, Chang WR. Crystal structures and site-directed mutagenesis of a mycothiol-dependent enzyme reveal a novel folding and molecular basis for mycothiol-mediated maleylpyruvate isomerization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16288–16294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unson MD, Newton GL, Davis C, Fahey RC. An immunoassay for the detection and quantitative determination of mycothiol. J Immunol Meth. 1998;214:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajan SS, Yang X, Shuvalova L, Collart F, Anderson WF. YfiT from Bacillus subtilis is a probable metal-dependent hydrolase with an unusual four-helix bundle topology. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15472–15479. doi: 10.1021/bi048665r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riddles PW, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Reassessment of Ellman’s reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Habig WH, Jakoby WB. Assays for differentiation of glutathione S-transferases. Methods Enzymol. 1981;77:398–405. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)77053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook JA, Pass HI, Russo A, Iype S, Mitchell JB. Use of monochlorobimane for glutathione measurements in hamster and human tumor cell lines. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:1321–1324. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrieve DC, Bump EA, Rice GC. Heterogeneity of cellular glutathione among cells derived from a murine fibrosarcoma or a human renal cell carcinoma detected by flow cytometric analysis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14107–14114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ublacker GA, Johnson JA, Siegel FL, Mulcahy RT. Influence of glutathione S-transferases on cellular glutathione determination by flow cytometry using monochlorobimane. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1783–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newton GL, Av-Gay Y, Fahey RC. A novel mycothiol-dependent detoxification pathway in mycobacteria involving mycothiol S-conjugate amidase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10739–10746. doi: 10.1021/bi000356n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanai T, Takahashi K, Inoue H. Three distinct-type glutathione S-transferases from Escherichia coli important for defense against oxidative stress. J Biochem. 2006;140:703–711. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayyadurai N, Kirubakaran SI, Srisha S, Sakthivel N. Biological and molecular variability of Sarocladium oryzae, the sheath rot pathogen of rice. In: Oryza sativa L, editor. Curr Microbiol. Vol. 50. 2005. pp. 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchmeier NA, Newton GL, Fahey RC. A mycothiol synthase mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has an altered thiol-disulfide content and limited tolerance to stress. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6245–6252. doi: 10.1128/JB.00393-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson T, Newton G, Fahey RC, Rawat M. Unusual production of glutathione in Actinobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2008;191:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0423-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen XH, Jiang CY, Huang Y, Liu ZP, Liu SJ. Functional identification of novel genes involved in the glutathione-independent gentisate pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3442–3452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3442-3452.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gontang EA, Gaudencio SP, Fenical W, Jensen PR. Sequence-based analysis of secondary-metabolite biosynthesis in marine actinobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2487–2499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02852-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galhano V, Gomes-Laranjo J, Peixoto F. Exposure of the cyanobacterium Nostoc muscorum from Portuguese rice fields to Molinate (Ordram((R))): Effects on the antioxidant system and fatty acid profile. Aquat Toxicol. 2011;101:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper DR, Grelewska K, Kim CY, Joachimiak A, Derewenda ZS. The structure of DinB from Geobacillus stearothermophilus: a representative of a unique four-helix-bundle superfamily. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:219–224. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109053913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benson RW, Norton MD, Lin I, Du Comb WS, Godoy VG. An active site aromatic triad in Escherichia coli DNA Pol IV coordinates cell survival and mutagenesis in different DNA damaging agents. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hori M, Yonekura S, Nohmi T, Gruz P, Sugiyama H, Yonei S, Zhang-Akiyama QM. Error-Prone Translesion DNA Synthesis by Escherichia coli DNA Polymerase IV (DinB) on Templates Containing 1,2-dihydro-2-oxoadenine. J Nucleic Acids. 2010;2010:807579. doi: 10.4061/2010/807579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaballa A, Newton GL, Antelmann H, Parsonage D, Upton H, Rawat M, Claiborne A, Fahey RC, Helmann JD. Biosynthesis and functions of bacillithiol, a major low-molecular-weight thiol in Bacilli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6482–6486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000928107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan F, Luxenburger A, Painter GF, Blanchard JS. Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis cysteine ligase (MshC) Biochemistry. 2007;46:11421–11429. doi: 10.1021/bi7011492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tremblay LW, Fan F, Vetting MW, Blanchard JS. The 1.6 A Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis MshC: The Penultimate Enzyme in the Mycothiol Biosynthetic Pathway (dagger) Biochemistry. 2008;47:13326–13335. doi: 10.1021/bi801708f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.