Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by a progressive cognitive decline and accumulation of neurotoxic oligomeric peptides amyloid-β (Aβ). Although the molecular events are not entirely known, it has become evident that inflammation, environmental and other risk factors may play a causal, disruptive and/or protective role in the development of AD. The present study investigated the ability of the chemokines, macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) and stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α), the respective ligands for chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4, to suppress Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Pretreatment with MIP-2 or SDF-1α significantly protected neurons from Aβ-induced dendritic regression and apoptosis in vitro through activation of Akt, ERK1/2 and maintenance of metalloproteinase ADAM17 especially with SDF-1α. Intra-cerebroventricular (ICV) injection of Aβ led to reduction in dendritic length and spine density of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 area of the hippocampus and increased oxidative damage 24 h following the exposure. The Aβ-induced morphometric changes of neurons and increase in biomarkers of oxidative damage, F2-isoprostanes, was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with the chemokines MIP-2 or SDF-1α. Additionally, MIP-2 or SDF-1α was able to suppress the aberrant mislocalization of p21-activated kinase (PAK), one of the proteins involved in the maintenance of dendritic spines. Furthermore, MIP-2 also protected neurons against Aβ neurotoxicity in CXCR2−/− mice, potentially through observed up regulation of CXCR1 mRNA. Understanding the neuroprotective potential of chemokines is crucial in defining the role for their employment during the early stages of neurodegeneration.

Keywords: chemokines, MIP-2, SDF-1α/CXCL12, hippocampus, neuroprotection, Amyloid β–neurotoxicity

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease resulting from dysfunctional neuronal synapses. It is characterized by the accumulation of neurotoxic oligomeric peptides of amyloid-β (Aβ) which affect synaptic plasticity during the early stages of AD. Neurons from the CA1 region of the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex are highly susceptible to Aβ-induced neurotoxicity (Selkoe, 2002). Several risk factors are associated with the early onset and progression of AD. Animal studies and epidemiological evidence suggest that neuroinflammation and elevated levels of transition metals (aluminum, copper, zinc, iron) and pesticides may play critical roles in the AD pathogenesis (Shcherbatykh and Carpenter, 2007; Rondeau et al., 2009; Ferretti and Cuello, 2011). Although the molecular events of AD pathogenesis are not entirely known, Aβ oligomers induce dendritic regression, spine density reduction, loss of synapses with resultant cognitive impairment, spatial memory deficits, and eventual neuronal apoptosis. Aβ oligomers also induce an up regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that initiate and promote neurodegeneration through the oxidative stress to neurons (De Felice et al., 2007). Thus, free radical-induced injury that occurs in early stages of AD is associated with an increase in F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs), prostaglandin-like molecules, produced by free radical-mediated peroxidation of arachidonic acid (AA) (Morrow et al., 1990; Pratico et al., 1998; Pratico and Sung, 2004; Milatovic and Aschner, 2009; Pratico, 2010). Among many factors that may play a causal, disruptive and/or protective role in the development of AD, chemotactic cytokines or chemokines have been proposed to be protective against Aβ–induced neuronal toxicity (Meucci et al., 1998; Watson and Fan, 2005).

Chemokines are a family of 8–16 kDa proteins that serve as chemoattractants for leukocytes. Chemokines and their cognate G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) play a significant role in inflammatory processes mediating leukocyte trafficking to the sites of inflammation. Many chemokines and their receptors, particularly CXCR2, CXCR4 and CXCR7, are involved in the development of the central nervous system (CNS). Generally in the adult CNS, chemokines are involved in modulation of neurotransmission, neuron-glial interaction and prevention of neurotoxicity (Miller et al., 2008). The chemokine CXCL12 (SDF-1α), a ligand for CXCR4 and CXCR7, is constitutively expressed by neurons and astrocytes, but the macrophage inflammatory peptide-2 (MIP-2) ligand for CXCR2 is produced by microglia in response to toxic stimuli such as Aβ peptides (Wang et al., 2000; Ito et al., 2006). Cortical regions of the brain and the hippocampus express the chemokine receptors CXCR2, CXCR4, CX3CR1 (Horuk et al., 1997; Lavi et al., 1997; Meucci et al., 1998; Xia and Hyman, 1999; Meucci et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2007).

MIP-2 and CXCL12 have been implicated to have a neuroprotective role in hippocampal neurons in terms of prevention of apoptosis induced by neurotoxic agents like HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 and Aβ peptides (Meucci et al., 1998; Watson and Fan, 2005). Rat orthologs of MIP2 also afford neuroprotection in toxic mileau (Wang et al., 2006). Moreover, CXCL12 pretreatment mediates survival signaling in hippocampal and cortico-spinal neurons (Meucci et al., 1998; Khan et al., 2008; Sengupta et al., 2009), which could be in part due to CXCL12 induced cleavage and release of the membrane bound CX3CL1 in cortical neurons and through an induction of the matrix metalloproteinase ADAM17 (Cook et al., 2010). The neuroprotective role of CXCL12 is further substantiated in a transgenic mouse model of AD where loss or reduction in level of CXCL12 led to impaired learning (Parachikova and Cotman, 2007). Importantly, reduced levels of CXCL12 have been observed in the plasma of early AD patients (Parachikova and Cotman, 2007; Laske et al., 2008).

The neuroprotective chemokines apparently generate an intracellular signaling cascade that counteracts the toxic signals in the CNS. The p21-activated kinase (PAK) is a downstream signaling effector of CXCR2 and CXCR4 pathways (Wang et al., 2002; Volinsky et al., 2006). PAK1 is an important regulator of spine morphogenesis and is required for cognitive function (Nikolic, 2008). PAK1 regulates hippocampal CA1 synaptic activity and the genetic ablation of PAK1 led to severe impairment of hippocampal long term potentiation (LTP) (Asrar et al., 2009). The activated and phosphorylated PAK regulates dendritic branching and spine morphogenesis and is distributed uniformly and diffusely in the soma. In human AD, PAK distribution in neurons is severely affected. Instead of being diffuse, PAK is particulate in distribution and aberrantly translocate to membranous and cytoskeletal areas in the hippocampal neurons (Zhao et al., 2006). This aberrant distribution can be rescued through the expression of an active form of PAK that prevents Aβ-induced dendritic regression (Ma et al., 2008).

There is a paucity of information about a protective role for chemokines in neurodegeneration. Given the conflicting reports as to whether CXCR2 activation is linked to neuroprotection or neurotoxicity (De Paola et al., 2007; Hosking et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010), the present study was conducted to test the hypothesis that chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 are neuroprotective against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Neuroprotection was evaluated in mouse primary neuronal cultures and in hippocampi of CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice by neuronal morphometry and assessment of dendritic length and spine density, neuronal apoptosis, survival or neuroprotective signaling, suppression of oxidative injury and distribution of PAK. Our studies show that either MIP-2 or CXCL12 pretreatment afford robust neuroprotection from Aβ-induced neurotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experiments were performed as approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Female CXCR2 (+/+) mice (C57BL/6 background) between 5 and 7 weeks of age were housed at 21 ± 1°C, humidity 50 ± 10%, in a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h with free access to pellet food (Rodent Laboratory Chow, Purina Mills Inc., St Louis, MO, USA) and water ad libitum. CXCR2 (+/+) mice were bred in the Vanderbilt University AALAC accredited Animal Facility. Since the CXCR2 (−/−) mice (C57BL/6 back ground) do not breed well, CXCR2 (−/−) mice were obtained by breeding CXCR2 (+/−) mice. CXCR2 (−/−) offspring mice were supplied with autoclaved food and water and were housed with a bedding of autoclaved wood shreds. All experiments were performed using the guidelines established by the NIH for humane care as outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. For some in vivo experiments age-matched female CXCR2 (+/+) mice were obtained from Jackson Research Laboratories.

Genotyping

The CXCR2 genotyping of mice was performed as described previously (Cacalano et al., 1994; Devalaraja et al., 2000). The PCR for the mouse CXCR2 gene was performed with forward primer 5’-GGCGGGGTAAGACAAGAATC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGCAAGGTCAGGGCAAAGAA-3’ and the ‘Neo’ cassette with forward primer 5’-CGGTTCTTTTTGTCAAGAC-3’ and reverse primer 5’- ATCCTCGCCGTCGGGCATGC-3’ as previously described.

Mixed cerebral cortical and hippocampal neuronal cultures

Since AD affects mainly the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus, in order to obtain a cell population containing the major relevant cell types, mixed neuronal/glial cultures were prepared from cerebral cortex and hippocampus from postnatal day 0–1 CXCR2 (+/+) or CXCR2 (−/−) mouse pups as described previously (Milatovic et al., 2010). Briefly, the animals were sacrificed under anesthesia; brains were removed from the skull and placed in modified Hank’s basal salt solution (HBSS) (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 10 mg/ml glucose). With the brain dorsum facing up, the brain hemispheres were separated and then the hippocampi and cerebral cortices were dissected away. Meninges from the hippocampi and cerebral cortices were peeled off from the front toward the back in one piece, on ice. Brain tissue was then trypsinized and triturated with Pasteur pipet and the cells were counted. A total of 600,000 cells were seeded per well (6-well plate) onto poly-L-lysine (0.5 mg/ml in borate buffer) coated cover slips in plating medium (Dulbecco’s MEM / F-12 with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and penicillin / streptomycin) and maintained for 48 h. These mixed cultures were incubated with β-D-cytoarabinofuranoside (Ara-C, 10 µM) for 24 h to limit glial proliferation. The medium was then changed to neurobasal medium with B-27 supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and replaced every 2 days for 21 days of culture. 21 DIV neuronal cultures display mature spines with PSD-95 clusters similar to the adult neurons (Gong et al., 2003). This is suitable for neurotoxic protection studies as culture of adult postmitotic neurons are difficult. Typically, 70–80% neurons were present in the mixed culture at the end of 21 days based on GFAP staining.

Preparation of Aβ

For in vitro experiments, the sodium salt of Aβ [(1–40):(1–42) – 6:1 molar ratio] (Anaspec Inc., San Jose, CA) was used in order to mimic the natural proportion of occurrence of the Aβ peptides in the cerebrospinal fluid. The Aβ mixture was dissolved in phenol-red free neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated at 4°C for 16–18 h to allow formation of oligomers of Aβ, while avoiding formation of multimers and fibrils. The resulting translucent solution was mixed and stored at −20°C in aliquots. For in vivo experiments, the sodium salt of Aβ [(1–40):(1–42) – 6:1 molar ratio] was dissolved in sterile saline and incubated at 4°C for 16–18 h to form oligomers of Aβ. The resulting translucent solution was mixed and stored at −20°C in aliquots.

Analysis of neuroprotection pathways

Neurons cultured in vitro were analyzed mainly for PI-3-kinase and ERK1/2 survival pathways. Proteins from neuronal lysates were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed for pThr308-Akt (Cell signaling,) and pERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) levels by Western blotting. The specificity of the signaling through CXCR2 and CXCR4 was determined with antagonists SB225002 and AMD-3100 respectively.

Real time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the brain of CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice by TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After the isolation of RNA, an on-column DNA digestion was performed using RNase-free DNAse (Qiagen; Hilden, Germany). RNA was analyzed for concentration and purity using the Nano Drop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA). Two-step real time RT-PCR was performed. cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Briefly, reverse transcriptase, 400 ng RNA, and reaction buffers were combined and incubated as follows: 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 42°C, and 5 min at 85°C. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using iQ5 real-time PCR detection systems (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA) utilizing iQ SYBR Green Super mix (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA) reagent. Reactions were incubated initially at 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles as follows: 95°C for 10 sec, 30 sec of annealing at 55°C, and 30 sec of extension at 72°C, during which data collection and real time analysis was enabled. All reactions were followed by a dissociation or melting curve to ensure that the PCR product is of single species. Relative quantification of mouse CXCR1 mRNA expression was analyzed using iQ5 software (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Mouse actin expression was used to standardize CXCR1 expression levels across reactions. All primers were from SA Biosciences (Frederick, MD).

Mouse CXCR1 PCR

Total RNA was obtained from the brains of CXCR2+/+ and CXCR2−/− mice by TRIzol method. cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Briefly, reverse transcriptase, 1 µg RNA, and reaction mix and buffers were combined and incubated as follows: 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 42°C, and 5 min at 85°C. CXCR1 PCR was performed with primers specific for mouse CXCR1: forward 5′-GGGTGAAGCCACAACAGATT, reverse 5′-CGGTGTGTCAAAACCTCCTT (Hosking et al., 2009). Reaction conditions for CXCR1 were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s; step 3, annealing at 58°C for 1 min; step 4, extension at 72°C for 30 s.

Immunocytochemistry

Neuronal cultures were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.5 (58 mM Na2HPO4, 17 mM NaH2PO4 and 68 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) (PBS) and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min on ice. After washing in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), the fixed neurons were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min on ice then washed once with PBST. Cover slips were then blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (Jackson Immunoresearch Inc.,West Grove, PA) in PBS for 1 h at R.T. The primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% normal donkey serum (NDS). Mouse CXCR2 (mCXCR2) was probed with a rabbit peptide antibody (1:50) (a gift from Kuldeep Neote of Eli Lilly); CXCR4 was probed with goat anti-C-terminal CXCR4 antibody (1:25) (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA); the whole neuron was visualized with mouse anti-MAP2 (microtubule associated protein 2) antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA) (5 µg/ml). After washing with PBS thrice, the cover slips were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies, Cy2 and Cy5-labeled donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (all were 1:100 diluted) (Jackson Immunoresearch Inc., West Grove, PA). After washing thrice with PBST and one time with PBS, the cover slips were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The edges of the cover slip were sealed with nail polish. Confocal images of the neurons and glia were acquired using a Zeiss Inverted LSM-510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a 63X objective and a 1.4 Plan-APOCHROMAT oil immersion lens. The captured images were processed by Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Neuronal tracing and morphometry

Confocal images of neurons were transferred to the Neurolucida (ver. 6.0) (MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT), a fully integrated software-controlled microscopic system, designed for highly accurate 3D neuron reconstructions, brain anatomical mapping, neuronal tracing, and morphometry. Traced neurons were then transferred to NeuroExplorer, a 3D visualization and morphometric analysis program designed for analyzing total dendritic length per neuron and spine density, the total number of dendritic spines per segment of dendritic branch (100 µm).

Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections

Following anesthesia, a 5-µL ICV injection was delivered over 1 min into the left lateral ventricle using a 26-gauge Hamilton syringe and the external landmarks of 4 mm lateral to midline and 5 mm posterior from the forward edge of the left ear (Montine et al., 2002; Milatovic et al., 2003). Depth of the injection was maintained at 3 mm by using a stylet. The chemokines, MIP-2 and CXCL12 (1 µg each), were administered by ICV, 30 min prior to Aβ-ICV injections (2.1 nmole total). The control mice received saline injection. After 24 h, the mice were euthanized, the brains were rapidly removed, dissected and immersed into Golgi-Cox staining solution or 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemistry.

Golgi-Cox staining of neurons

After 3 weeks of fixation / processing with Golgi-Cox impregnation solution, the brains were stained by Golgi-Cox method according to the manufacturer specifications (FD RapidGolgiStain Kit, FD NeuroTechnologies, Ellicott City, MD). The Golgi impregnated brains were embedded in paraffin and cut to a thickness of 50 µm from paraffin-embedded blocks. Six or more Golgi-impregnated pyramidal neurons with no breaks in staining along the dendrites from CA1 sector of hippocampus were selected and spines were counted as previously described (Milatovic et al., 2003). Tracing and counting were done under 100x+oil immersion using the Neurolucida system (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT) attached to the Olympus BX61 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with Hamamatsu 1394 ORCA-ER digital camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ).

Immunohistochemistry

In order to stain p21-activated kinase (PAK), paraffin embedded brain sections from CXCR2 (+/+ and −/−) mice were cut to 5 µm thickness and PAK was probed with anti-PAK1 (total) polyclonal antibody (1:50) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and rabbit polyclonal phospho-PAK (pT423) (1:50) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). For staining of chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12, goat anti-mouse MIP2 antibody (1:50) (R & D Biosystems, Minneapolis, MN) and rabbit anti-mouse CXCL12 antibody (1:50) (Torrey Pines Biolabs, Inc, Houston, TX) were respectively employed. For the visualization of CXCR2 and CXCR4, a rabbit peptide anti-mCXCR2 (1:50) (a gift from Kuldeep Neote of Eli Lilly) and monoclonal rat anti-mouse CXCR4 (clone 247506) (1:50) (R & D Biosystems, Minneapolis, MN) antibodies were respectively employed. Briefly, the immunohistochemistry (IHC) protocol involved deparaffinization / hydration of sections by three xylene washes for 10 min each, two washes of 100% ethanol for 10 min each and two washes of 95% ethanol for 10 min each. The sections were subsequently washed twice in dIH2O for 5 min each followed by one wash in 1x Tris buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) for 5 min. For antigen unmasking, sections were heated at 100°C in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 1 min at full power followed by 9 min at medium power, and then the slides were cooled for 20 min. After antigen unmasking, sections were washed in dIH2O thrice for 5 min each. Sections were then incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 min and washed in dIH2O thrice for 5 min each followed by 1x TBST wash for 5 min. Sections were blocked for 15 min using blocking solution Background Sniper (BioCare Medical, Concord, CA) at room temperature. Primary antibody was diluted in antibody diluent (DakoCytomatin, Carpinteria, CA) and sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in humidified chamber. The primary antibody was then removed and sections were washed in 1x TBST thrice for 5 min each followed by horse anti-mouse or horse anti-rabbit antibodies from ABC-Vector kit and sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After this, the secondary antibody was removed and sections were washed in 1x TBST thrice for 5 min each. ABC reagent was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were washed in 1x TBST thrice for 5 min each. The color was developed by adding AEC chromogen substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and incubated at room temperature for 5–10 min. As soon as red color appeared, all the sections were immersed in deionized H2O. Sections were counterstained in hematoxylin for 1 min, washed in tap water, dehydrated through gradients of ethanol (70%; 95%; 100%) and cleared in xylene, then cover slips were placed using Permount Mounting Medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Apoptosis assay

The TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotide transferase [TdT]-mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick-end labeling) method is based on the in situ labeling of DNA fragmentation sites in nuclei of fixed neurons that have undergone apoptosis or programmed cell death at single neuronal level. Mixed neuronal cultures of CXCR2 WT (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) genotype were incubated with MIP2 (10 nM), CXCL12 (10 nM), Aβ (7.5 µM), MIP2+Aβ, CXCL12+Aβ for 24 h following which the medium was removed and washed with ice-cold PBS. The apoptotic neurons were detected with DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI).

Apoptotic nuclei was counted blinded to the experimenters using a confocal microscope, counting apoptotic neuronal cells per 10 high-power fields at a magnification of 400X. For each slide, a minimum of 10 randomly selected fields were examined and counted. Results were expressed as a percentage of apoptotic versus non-apoptotic neurons for both genotypes.

Quantitation of F2-Isoprostanes

Upon completion of the chemokine mediated neuroprotection experiments, the brains were rapidly harvested, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and were stored at −80°C until analysis. Total F2-Isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs) were determined with a stable isotope dilution method with detection by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and selective ion monitoring as described previously (Morrow et al., 1990; Milatovic and Aschner, 2009). Briefly, cerebral hemispheres were homogenized in Folch solution and lipids extracted from chloroform layer by evaporation. Total lipids were resuspended in 0.5 ml of methanol containing 0.005% butylated hydroxytoluene, sonicated and then subjected to chemical saponification using 15% KOH to hydrolyze bound F2-IsoPs. The samples were adjusted to a pH of 3, followed by the addition of 0.1 ng of 15-F2α-IsoP-d4 internal standard. F2-IsoPs were subsequently purified by C18 and silica Sep-Pak extraction and by thin layer chromatography. After esterification into a pentafluorobenzyl ester (a trimethylsilyl ether derivative), they were analyzed by gas chromatography followed by negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry.

Image J analysis

The Western blot read outs from the neuroprotective signaling pathways from 3–4 independent experiments were quantified using NIH Image J program (ver 1.41o)

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test with statistical significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 afford neuroprotection against Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity by preventing dendritic regression and neuronal apoptosis in vitro

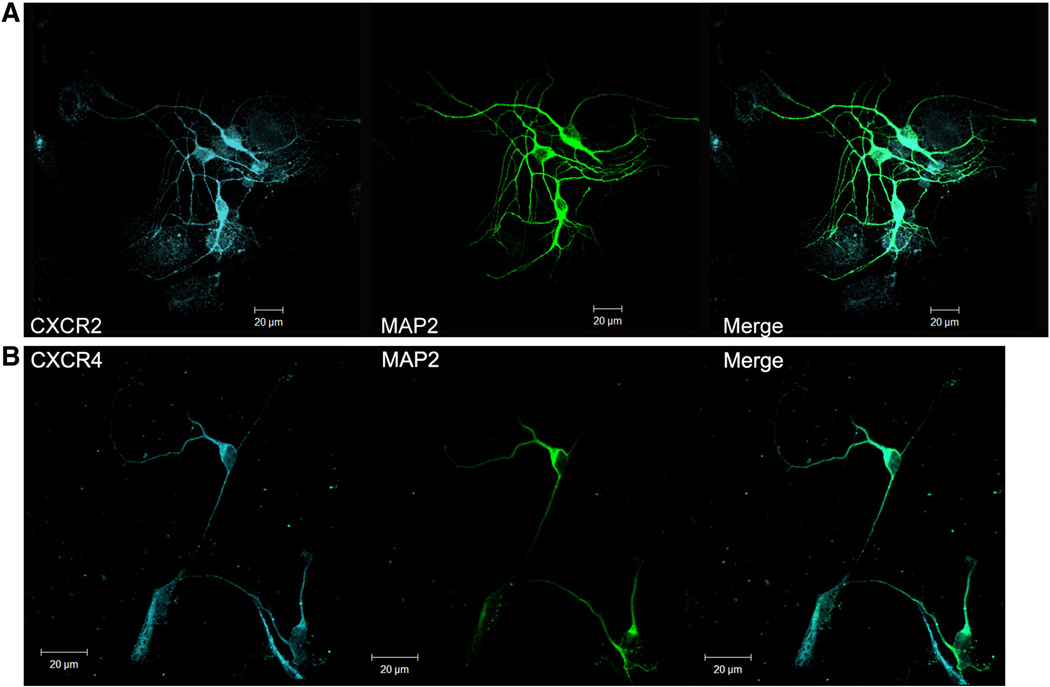

To evaluate the expression of chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 in mouse primary neuronal cultures from cerebral cortices and hippocampi, fixed cultures were probed for mouse CXCR2 (mCXCR2) or mCXCR4 by immunocytochemistry and evaluated by confocal microscopy. Results show that neurons stained positively for the neuronal marker microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP2) expressed the chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 in the soma and the dendritic branches (Fig 1A. and B).

Figure 1. Expression profile of chemokines and their receptors in mouse neurons in vitro.

CXC chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 are present in soma and dendritic compartments in cultured neurons 21 days in vitro (DIV). MAP2 marker was used to visualize the neurons.

Representative pseudo-colored confocal images of neurons were shown as cyan – CXCR2 or CXCR4 and green – MAP-2; scale bar – 20 µm.

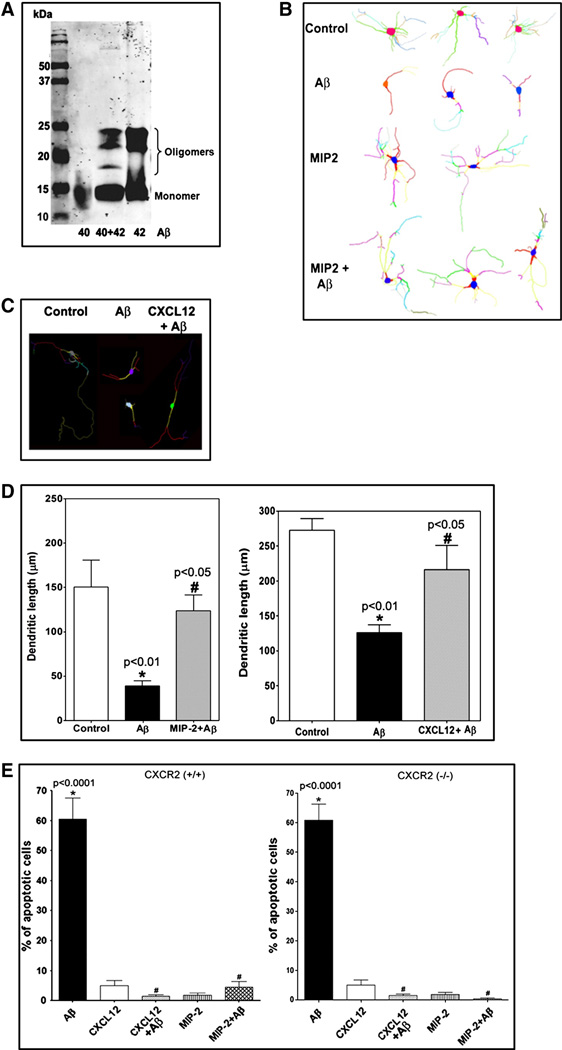

To ascertain whether the Aβ preparation [mixture of Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42)] had oligomeric/neurotoxic forms, the Aβ preparation was subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. As presented in Figure 2A, dimeric and trimeric forms of Aβ were apparent along with the monomers, similar to the forms observed in Aβ(1–42) lane. In addition, an intermediary oligomeric form was evident, possibly from a dimer composed of Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. CXC chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 afford neuroprotection in vitro.

A. The preparation of Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) mixture was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting.

B and C. Representative neurolucida traces from the confocal immunofluorescent images of MAP2-stained neurons from control, Aβ-treated and MIP-2 and CXCL12 pretreated prior to Aβ-treatment were shown depicting Aβ-induced damage and MIP2-medited and CXCL12-mediated neuroprotection.

D. CXC chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 prevent Aβ-induced dendritic regression in vitro. The graphs show the measurements obtained for the dendritic length that were plotted against the type of treatment. The dendritic length calculated using Neuroexplorer program was expressed in microns. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Aβ* - significant difference from the control (p<0.01); MIP-2+Aβ # - significant difference from Aβ (p<0.05); CXCL12+Aβ # -significant from Aβ (p<0.05).

E. CXC chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 prevent Aβ–induced neuronal apoptosis in vitro. Apoptotic nuclei per 10 random high-power fields (HPF) (400X) were counted after different treatments and were plotted as % of apoptotic neurons for each respective treatment group for both CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) primary neuronal cultures. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. * - Significant difference in neuronal apoptosis was observed in Aβ-treated group; # - Significant neuroprotection was observed in individually treated MIP-2 and CXCL12 groups.

To assess the in vitro chemokine-mediated neuroprotection, the neurons were visualized with MAP2 staining and evaluated by confocal microscopy for MIP2 and CXCL12 mediated prevention of the dendritic regression. The representative confocal images of the neurons traced with Neurolucida from the control, Aβ–treated, and MIP2 or CXCL12 pretreated/Aβ treated neuronal cultures are presented in Figures 2B and C. Significant prevention of the Aβ-induced dendritic regression of the neurons was observed in the neurons pretreated either with 10 nM MIP-2 or 10 nM CXCL12 (Fig. 2D). The dendritic length between control and CXCL12-pretreated/Aβ was not statistically significant (p>0.05) though the dendrites appear to be shorter than the control in the depicted representative images. In addition, the ability of MIP2 and CXCL12 to prevent the Aβ-induced neuronal apoptosis was evaluated in vitro by the TUNEL assay. Aβ induced significant neuronal apoptosis that was prevented by pretreatment of the CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) neurons with either 10 nM MIP-2 or 10 nM CXCL12 (Fig. 2E). Surprisingly, pretreatment of CXCR2 (−/−) neurons with MIP-2 also significantly prevented neuronal apoptosis (Fig. 2E). Overall, our data suggest that the chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 have the ability to protect the neurons from Aβ-induced toxicity in vitro.

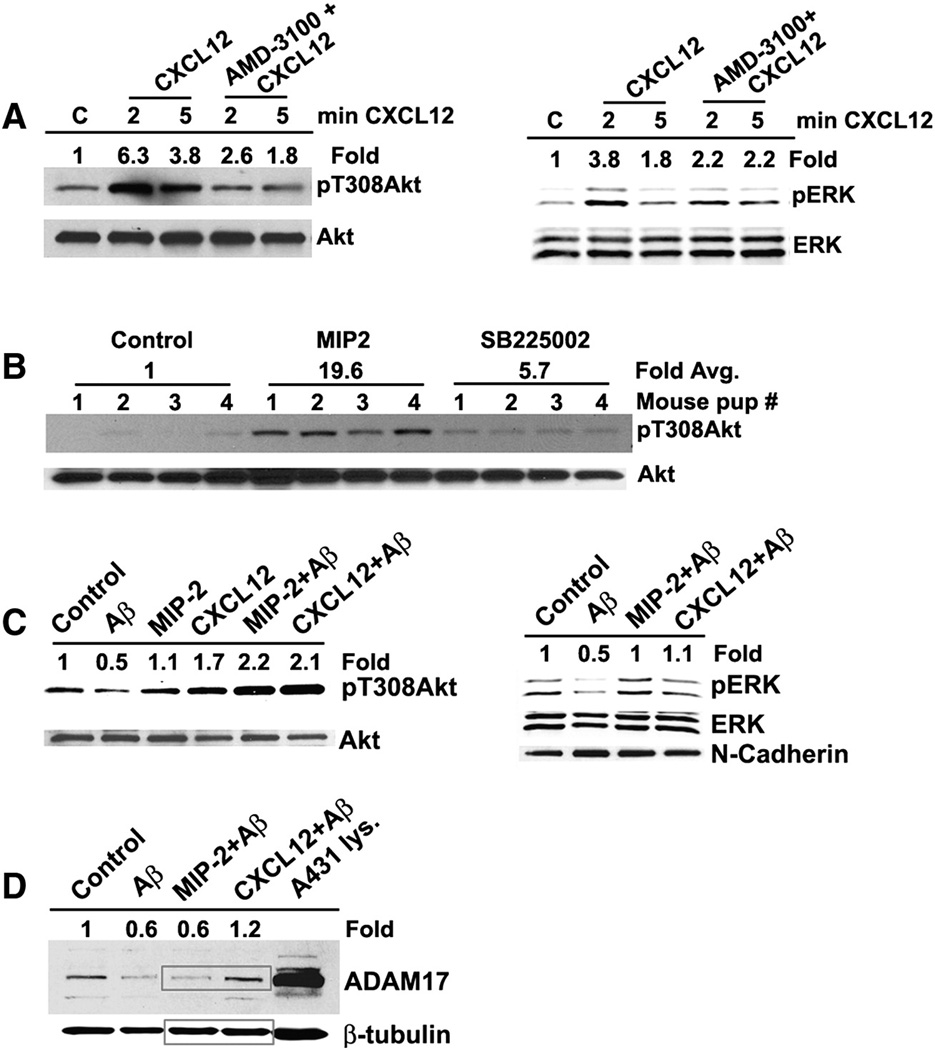

Chemokine mediated neuroprotection is associated with activation of PI-3-kinase and ERK1/2 pathways

In order to determine the signaling pathways that might contribute to the observed prevention of dendritic regression and neuronal apoptosis, the neurons from the control, Aβ–treated, and MIP2 or CXCL12 pretreated/Aβ treated neuronal cultures were lysed, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed for phospho-Akt (pT308) and phospho-ERK1/2. Before examining the neuroprotection with pAkt and pERK1/2 as the read out, the specificity of the CXCR4 and CXCR2 signaling were tested by treating the primary neuronal cultures with CXCR4 antagonist AMD-3100 and CXCR2 antagonist SB225002. Neurons were stimulated with 10 nM CXCL12 for 2 and 5 min with and without AMD-3100 pretreatment. AMD-3100 efficiently inhibited the CXCL12-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 to the control levels indicating the specificity of CXCR4 signaling (Fig. 3A). Similarly, SB225002 was able to inhibit MIP2-mediated pAkt accumulation through CXCR2 (Fig. 3B). Accordingly, it was apparent that the MIP2 and CXCL12-mediated signaling occurs through specific activation of CXCR2 and CXCR4 signaling pathways respectively.

Figure 3. Chemokine-mediated neuroprotection is associated with activation of PI-3-kinase and ERK1/2 pathways in vitro.

A and B. The specificity of the neuroprotective signaling from CXCR4 and CXCR2 was examined by treating the primary neuronal cultures with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD-3100 and CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 in terms of activation of Akt and ERK1/2 through phosphorylation. The representative blots were shown. Data from 3–4 independent experiments were quantitated using Image J program. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. A – a) pAkt - Control vs. CXCL12 - 2 min – p<0.001; Control vs. CXCL12 - 5 min – p<0.05; CXCL12 - 2 min vs. AMD-3100+CXCL12 – 2 min - p<0.05 b) pERK - Control vs. CXCL12 - 2 min – p<0.05. B – Control vs. MIP2 – p<0.001; MIP2 vs. SB225002+MIP2 – p<0.01.

C. Immunoblot analysis of the chemokine-mediated neuroprotection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Phosphorylation of Akt at T308 and ERK1/2 was assessed by running 50 µg of total protein from the neuronal lysates from different treatments by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. In the right ERK panel, N-cadherin served as an additional loading control. Data from 3 independent experiments were quantitated using Image J program. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test - 1) Aβ vs. MIP2+ Aβ – p<0.05 2) Aβ vs. CXCL12+ Aβ – p<0.05.

D. Immunoblot analysis of the stabilization of the matrix metalloproteinase ADAM17 by the CXCL12 pretreatment. 50 µg of the total protein from the neuronal lysates from different treatments was separated by SDS-PAGE and ADAM17 level and analyzed by immunoblotting. Data from 3 independent experiments were quantitated using Image J program. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test - Aβ vs. CXCL12+ Aβ – p<0.05.

Aβ treatment of the neurons led to a decrease in Akt phosphorylation at T308 and a decrease in phosphorylation of ERK1/2. However, neurons pretreated with the chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 before Aβ exposure, exhibited efficient activation of the PI-3-kinase and ERK1/2 pathway, based upon the increased accumulation of pT308 and pERK1/2 (Fig. 3C). Additionally, some difference in the signaling specificity of MIP2 and CXCL12 pathways was observed in terms of stabilization of ADAM17, a matrix metalloprotease. Aβ treatment induced a decrease in ADAM17 and this was prevented by CXCL12, but not by MIP2 (Fig. 3D). A431 human epidermoid carcinoma lysate with abundant ADAM17 expression served as the positive control for ADAM17 (Right lane). Thus, the observed prevention of dendritic regression and apoptosis is accompanied by activation of the PI-3-kinase and ERK pathways and stabilization of ADAM17 level.

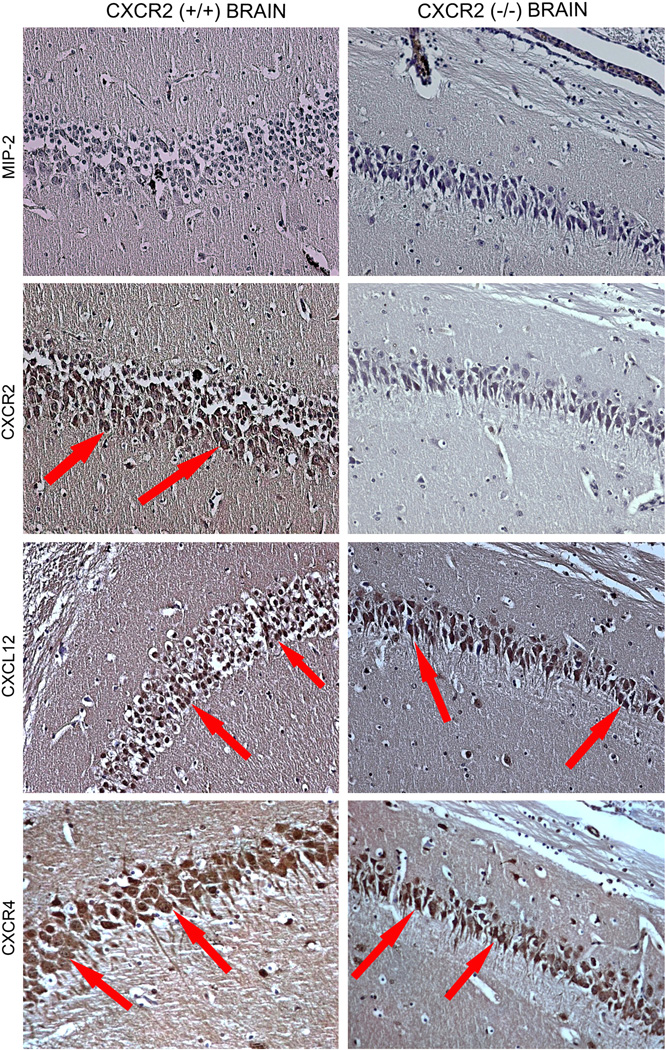

Chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 afford neuroprotection in vivo through prevention of dendritic regression and reduction in spine density

To test if the observed in vitro findings are applicable in vivo, we examined the chemokine mediated neuroprotection against Aβ–induced neurotoxicity in the hippocampal neurons of CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice. To verify the CXCR2 null or wild type status of mice and evaluate the expression of chemokines in the absence of CXCR2, expression of CXCR2, CXCR4, MIP2 and CXCL12 in hippocampal neurons of CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice were examined by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4). Results from our study show that the chemokine MIP2 was undetectable in the hippocampal neurons of both CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice, on the contrary, CXCR2, CXCR4 and CXCL12 were expressed in hippocampal neurons of CXCR2 (+/+) mice (Figure 4). CXCR2 was undetectable in CXCR2 (−/−) hippocampal neurons confirming the knockout of CXCR2 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Expression profile of chemokines and their receptors in mouse neurons in vivo.

The brain sections were examined for the expression of chemokines MIP2 andCXCL12 and the chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 in the hippocampal neurons in vivo. The left panel depicts the immunolocalization in the hippocampus of CXCR2 (+/+) mice and the right panel shows CXCR2 (−/−) mice. The hippocampal sections in which positively stained neurons were observed were indicated by red arrows.

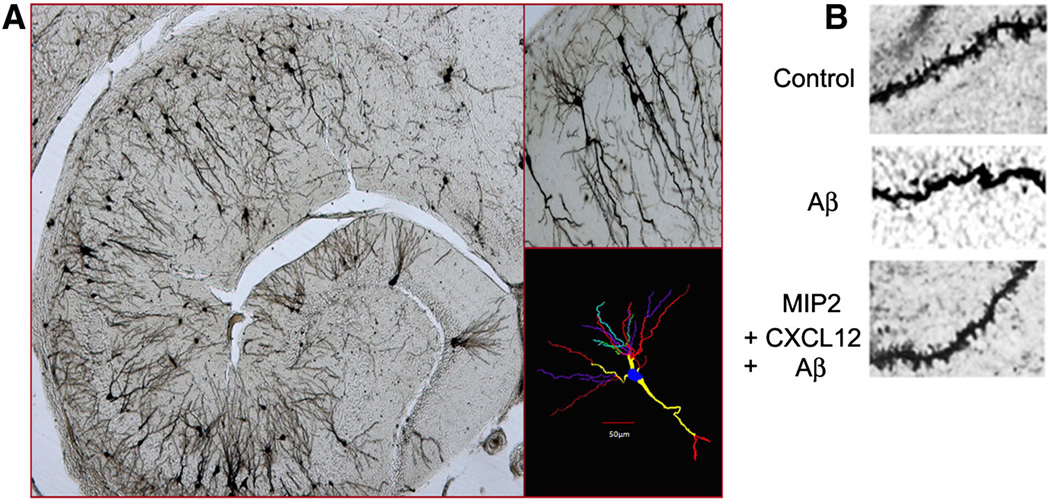

Next, the protective role of exogenous administration of MIP2 and CXCL12 on hippocampal neuron spine density was examined in vivo. The photomicrographs of a typical golgi-impregnated control mouse hippocampus and a representative Neurolucida tracing of a pyramidal neuron is shown in Figure. 5A. High power photomicrographs of dendritic segments from control (saline exposed animal) display substantially higher spine density compared to the Aβ–treated neurons (Fig. 5B). Combined ICV pretreatment with MIP-2 and CXCL12 clearly showed the prevention of Aβ–induced loss of dendritic spines and thus indicates that these two chemokines are neuroprotective at the level of dendritic spine loss.

Figure 5. Golgi-Cox staining of neurons for the assessment of quantitative neuroprotection by the chemokines in vivo.

A. Photomicrographs of mouse hippocampus (2.5X) with pyramidal neurons (10X) and neuronal tracing from CA1 hippocampal area of brain 24 h after saline (control) injection. Tracing and counting were done using a Neurolucida system at 100 x under oil immersion (MicroBrightField, VT). Colors indicate the degree of dendritic branching (yellow=1°, red=2°, purple=3°, green=4°, turquoise=5°).

B. Chemokine MIP-2 and CXCL12 pretreatment preserved the dendritic spines from Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in vivo.

The panel depicts high power photomicrographs (100 X) of Golgi-impregnated dendritic segments with spines from hippocampal neurons that were treated with either i) saline, ii) Aβ or iii) combined MIP-2 and CXCL12 before Aβ exposure.

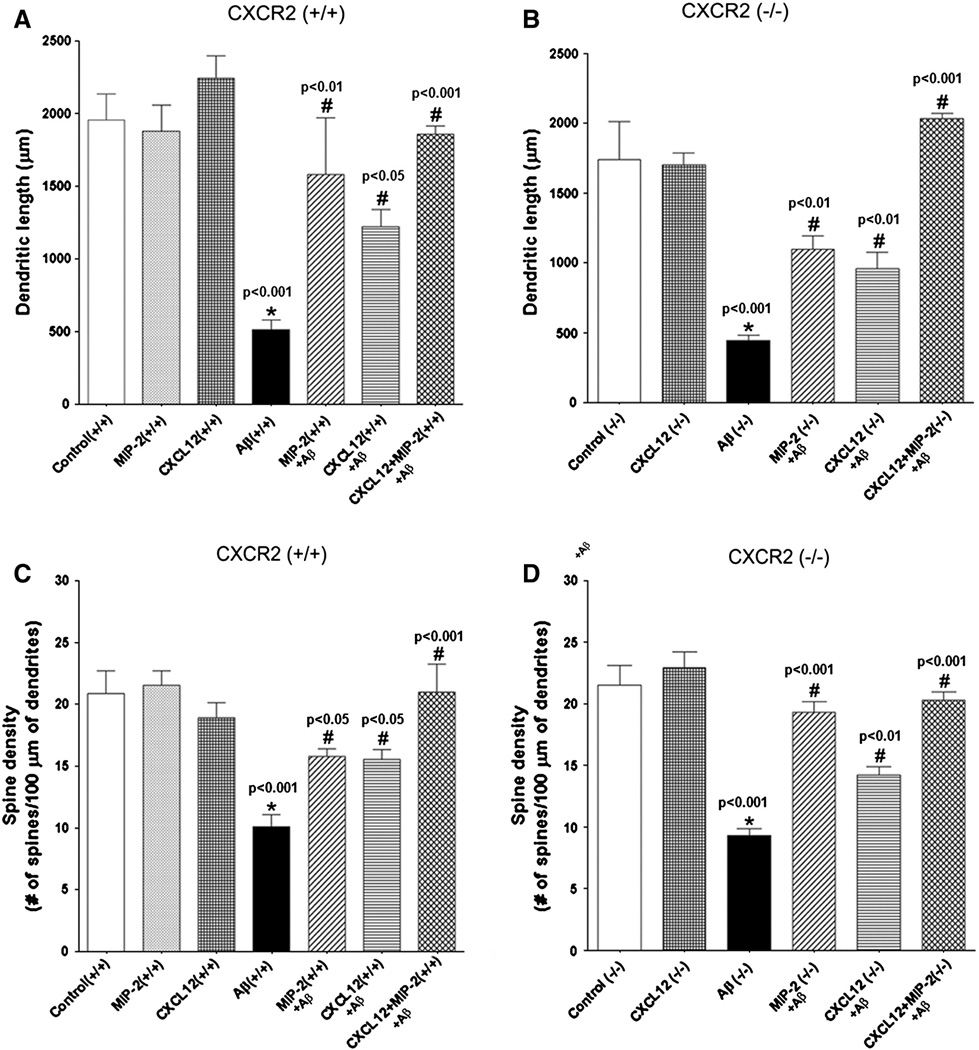

The neuroprotective effects of the chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 were further evaluated quantitatively from the computerized tracings of CA1 hippocampal neurons. Morphometric measurements of the dendritic length and spine density were plotted against Aβ and different chemokine treatments (Fig. 6A, B, and D). Treatment with Aβ induced significant regression in dendritic length (Fig. 6A & B) and reduction of the spine density (Fig. 6C & D) in both CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice. ICV pretreatment with MIP-2 (1µg) or CXCL12 (1 µg) attenuated the Aβ-induced neurotoxic effects through significant preservation of the dendritic length and the maintenance of the spine density. However, the mice that were pretreated simultaneously with both MIP-2 (1 µg) and CXCL12 (1 µg) prior to ICV delivery of Aβ displayed an enhanced protective effect over that of either chemokine alone and showed dendritic length and spine density comparable to the control (only saline exposed animals) (Fig. 6A, B, C & D). The neuronal morphometric parameters for Fig. 6A–D reflecting the neuroprotection were tabulated in Table 1.

Figure 6. Morphometric evaluation of chemokine-mediated neuroprotection in vivo.

A & B. Preservation of dendritic length of hippocampal CA1 neurons upon MIP-2 and CXCL12 pretreatment in CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice.

The dendritic length (microns) obtained was plotted against the different treatment groups. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. * - Significant difference observed in Aβ-treated group when compared to the control; # - Significant neuroprotection observed in individually treated MIP-2 and CXCL12 groups compared to the Aβ–treated group.

C & D. Preservation of dendritic spine density by MIP-2 and CXCL12 pretreatment.

The dendritic spine density of CA1 hippocampal neurons was plotted against respective treatment group. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. * - Significant difference observed in Aβ-treated group when compared to the control; # - Significant neuroprotection observed in individually treated MIP-2 and CXCL12 groups compared to the Aβ-treated group.

Table 1. Neuroprotection afforded to CA1 hippocampal neurons from Aβ-induced neurotoxicity by the CXC chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12.

The values from the saline control group was normalized to 100% and compared to other treatment groups.

| CXCR2 Genotype |

Parameter | Aβ | Aβ+MIP−2 | Aβ+CXCL12 | Aβ+MIP-2 +CXCL12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXCR2 (+/+) | Dendriticlength | 26±4% | 81±20% p<0.01 * |

62±7% p<0.05 * |

95±17% p<0.001 * |

| CXCR2 (−/−) | Dendriticlength | 26±3% | 63±6% p<0.01 * |

55±6% p<0.01 * |

117±3% p<0.001 * |

| CXCR2 (+/+) | Spine density | 48±5% | 76±4% p<0.05 * |

75±4% p<0.05* |

101±10% p<0.001 * |

| CXCR2 (−/−) | Spine density | 43±2% | 90±4% p<0.001 * |

66±3% p<0.01 * |

95±3% p<0.001 * |

Significant when compared to Aβ value; ± - S. D. (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-hoc test)

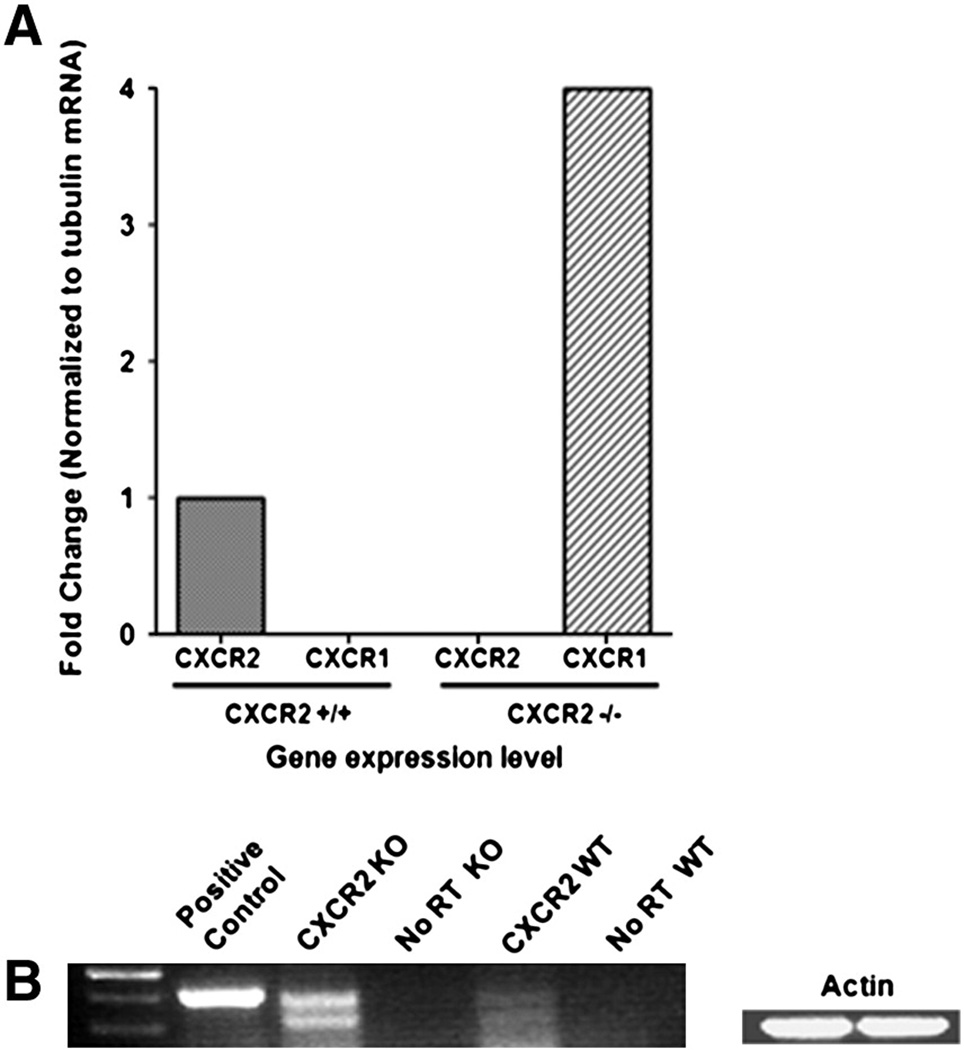

Interestingly, in CXCR2−/− mice, pretreatment with MIP-2 also suppressed Aβ induced dendritic damage and even afforded higher protection on dendritic spines compared to CXCR2 +/+ mice (Figure 6). The observed neuroprotective effect of MIP-2 in CXCR2 (−/−) neurons might be through an alternate receptor for MIP2 other than CXCR2. To evaluate the other chemokine receptor capable of binding to MIP2, we performed real-time qPCR for the presence of mouse CXCR1 in the brain of adult CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) mice. In parallel, we evaluated levels of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and the chemokine CX3CL1 (fractalkine) as internal controls. Results from these experiments show a 4-fold elevation of CXCR1 mRNA level in adult CXCR2 (−/−) mice compared to barely detectable level of CXCR1 mRNA in adult CXCR2 (+/+) brain (Fig. 7). The mRNA levels of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and the chemokine CX3CL1 (fractalkine) remained unchanged regardless of the presence or absence of CXCR2 in the brain (data not shown). RT-PCR analysis also showed a similar increase in CXCR1 mRNA in the CXCR2 (−/−) brain and lung CXCR1 mRNA served as the positive control (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Increased expression of CXCR1 mRNA in the adult CXCR2 (−/−) brain.

A. The level of CXCR1 and CXCR2 mRNA from CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) brain was analyzed by qRT-PCR of the total mRNA obtained by the TRIzol method. The level was normalized to the β-tubulin mRNA and expressed as fold change.

B. The semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the level of CXCR1 mRNA from CXCR2 (+/+) and CXCR2 (−/−) brain was performed. The lung sample served as the positive control and the actin served as the loading control.

Overall, the assessment of neuronal morphometry showed that chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 afford neuroprotection of the hippocampal neurons in vivo. In addition, the CXCR1 receptor was up regulated in the brain of CXCR2 (−/−) mice which may explain the MIP-2 mediated neuroprotection in these animals.

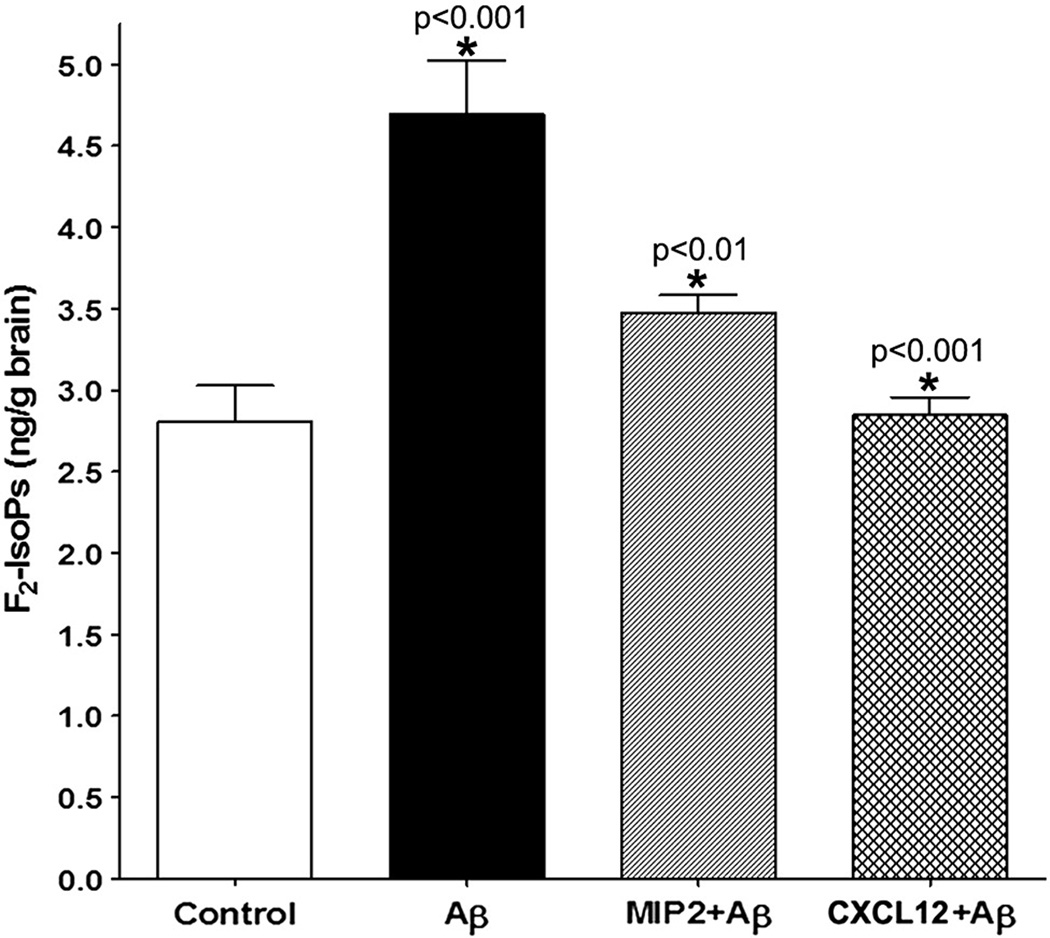

MIP2 or CXCL12 pretreatment prevented the Aβ-induced oxidative damage in vivo

In order to determine whether with chemokine pretreatment would prevent the Aβ-induced neuronal oxidative damage in vivo, total F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs) were evaluated in mouse cerebrum by using a stable isotope dilution method with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and selective ion monitoring. Results from these experiments showed that Aβ-induced increase in F2-IsoPs was suppressed if CXCR2 (+/+) mice were pretreated chemokines MIP2 or CXCL12 prior to the ICV administration of Aβ (Fig. 8). This shows that both MIP-2 and CXCL12 operate through multiple mechanisms to prevent Aβ-induced oxidative damage.

Figure 8. MIP2 or CXCL12 pretreatment prevented the Aβ-induced oxidative damage in vivo.

The oxidative damage by Aβ and the prevention of such oxidative damage by the chemokine pretreatment was assessed by the quantitative measurement of F2-isoprostanes in the cerebrum in the adult CXCR2 (+/+) brain. The level of F2-isoprostanes was expressed as ng / g of brain tissue and was plotted against different treatments. Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test – Aβ vs. control – p<0.001; Aβ vs. Aβ+MIP2 – p<0.01; Aβ vs. Aβ+CXCL12 – p<0.001.

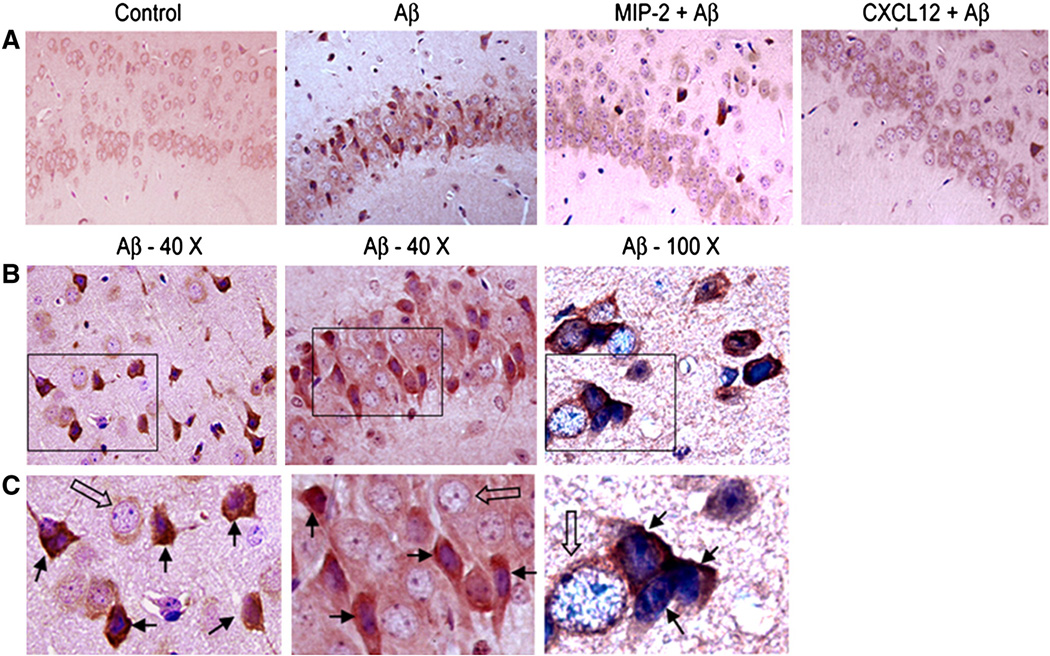

MIP-2 or CXCL12 pretreatment prevented the particulate and intense distribution of p21-activated kinase (PAK) induced by Aβ in vivo in CA1 hippocampal neurons

p21-activated kinase (PAK) has been reported to aberrantly translocate to membranous and cytoskeletal areas in the human hippocampal neurons affected by the Alzheimer’s disease as well as in in vitro models. To evaluate the ability of the chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 to prevent such aberrant translocation of PAK, we examined the localization of PAK in hippocampal neurons from saline, Aβ–treated and MIP-2 or CXCL12 pretreated CXCR2 (+/+) mice. The saline exposed control showed a very diffuse and mild staining for total PAK. The nuclei were clear with distinct nucleoli (Fig. 9A). When the brains were ICV injected with 2.1 nmol of Aβ, many neurons exhibited a PAK staining pattern that was intense and patchy, instead of mild and diffuse as observed in the control. The nuclei were condensed in many Aβ–treated neurons. At higher magnifications, the intense particulate staining for total PAK (closed arrows) was obvious compared to nearby normal, unaffected neurons (big open arrows) in the same microscopic field (Fig. 9B and C). When pretreated with either MIP2 (1 µg) or CXCL12 (1 µg) prior to Aβ injection, the intense and patchy distribution of PAK1 was significantly prevented (Fig. 9A) and both chemokines were equally effective. Overall, PAK1 misdistribution was prevented by pretreatment with either MIP-2 or CXCL12.

Figure 9. Differential distribution of p21-activated kinase (PAK) in CA1 hippocampal neurons in vivo.

A: Light photomicrographs of hippocampal CA1 neurons from control brain sections (20 X) depicting the total PAK distribution; Aβ–treated neurons showed intense or darkly stained pattern for PAK1 in the cytoplasm; MIP-2 (1 µg) or CXCL12 (1 µg) pretreatment depicts a diffuse and smooth distribution of PAK.

B: Sections from the brain that were treated with Aβ only (40 X and 100 X of two different sections) - Aβ affected neurons displayed mislocalized, intense and particulate distribution of PAK and also nuclear condensation was observed indicated by dark blue nuclei.

C: Boxed inset area in ‘B’ was magnified and shown. Note that the Aβ affected neurons pointed out by closed arrows have dark and granular PAK distribution; some have condensed dark blue nuclei. The normal adjacent neurons are indicated by open arrows with clear nuclei shown to contrast the Aβ affected CA1 hippocampal neurons in the field.

Discussion

The present study explored neuroprotective role of chemokines and chemokines receptors against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Findings revealed that chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 have the ability to protect the neurons from Aβ-induced synaptodendritic alterations and apoptotic changes in vitro. Importantly, our results also demonstrated protective role of exogenous administration of MIP2 and CXCL12 on Aβ-induced hippocampal dendritic regression, oxidative damage and aberrant translocation of PAK as well as indicate signaling pathways that might contribute to the chemokine-mediated neuroprotection in vivo.

The observed neuroprotection by these chemokines could be due to direct abrogation of the binding of Aβ oligomers by down regulation of their binding sites on neurons as observed in the case of activation of the insulin receptor by insulin (De Felice et al., 2009). Alternatively, the chemokines can act by antagonizing or counteracting the Aβ-induced stress signaling pathways that are deleterious to the maintenance of the dendrites and dendritic spines and ultimately for neuronal survival. MIP-2 mediated prevention of hippocampal neuronal apoptosis was shown to involve phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3-kinase) and extracellular signal regulated mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK) survival pathways (Watson and Fan, 2005). Recently, ERK activation has been reported to promote neuritogenesis (Wang et al., 2011). ERK2 could also phosphorylate spinophilin on Ser15 and Ser205 to increase the binding of spinophilin to actin and promote bundling of actin filaments necessary for spine morphogenesis (Futter et al., 2005). In transgenic mouse model of AD, reelin was depleted in the entorhinal cortex and the reelin-ApoER2 pathway has been implicated to activate PI-3-kinase and stabilize actin cytoskeleton through the inhibition of downstream cofilin activity by inducing phosphorylation of cofilin (Chin et al., 2007; Chai et al., 2009). In our chemokine-mediated neuroprotective model, PI-3-kinase not only imparts neuronal survival but presumably can stabilize the actin cytoskeleton similar to reelin. Interestingly, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), a CXCR2 interacting protein, was also recently reported to be critical for spinogenesis and modulation of the synaptic strength through actin polymerization and bundling (Neel et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010). Therefore, CXCR2 may afford neuroprotection possibly through its ability to interact with VASP and also the activation of ERK and PI-3-kinase pathways. Additionally, many downstream signaling pathways that are activated by MIP2, including ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2), transcription factor cyclic AMP response element binding (CREB) protein and phosphorylation of Bad at Ser112 and Ser136, were all shown to be neuroprotective in nature (Zhu et al., 2002; Watson and Fan, 2005). CXCL8, another chemokine ligand for CXCR2, has been shown to mitigate the NMDA-induced toxicity in mixed cortical neuronal cultures and also enhance the survival of hippocampal neurons (Araujo and Cotman, 1993; Bruno et al., 2000). CXCL8 has also been shown to activate PI-3-kinase in cerebellar granular neurons and differentiated neutrophil-like HL-60 cells (Limatola et al., 2002; Sai et al., 2008).

Neuroprotection afforded by MIP-2 in CXCR2 (−/−) neurons in vivo indicates that an alternate receptor like CXCR1 may mediate the protection against Aβ. It has been previously reported that a putative MIP-2 receptor (other than CXCR2) mediate its responses in CXCR2 (−/−) astrocytes (Luo et al., 2000). This alternate receptor may explain similar MIP-2 mediated neuroprotection in response to Aβ in CXCR2−/− neurons observed in our studies. Murine CXCR1 has been reported to be expressed in mouse and rat brain (Nguyen and Stangel, 2001; Puma et al., 2001; Danik et al., 2003; Goczalik et al., 2008; Lauren et al., 2010). Previously, it has been reported that CXCR2 (−/−) neutrophils do migrate to CNS in response to neurotropic viral infection due to amplification of CXCR1 mRNA in the absence of CXCR2 enabling the survival of CXCR2 (−/−) mice (Hosking et al., 2009). The 4-fold increase in CXCR1 mRNA level by qPCR in CXCR2 (−/−) mice reported in our study may explain the observed MIP2-mediated neuroprotection in these mice. The affinity of murine CXCR1 for MIP-2 is 10-fold lower than that of murine CXCL6, but this may be compensated by excess MIP2 in the circulating blood of the CXCR2 (−/−) mice (Fan et al., 2007; Cardona et al., 2008). Our data, along with these reports, suggest a neuroprotective role for MIP2 in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity that can be both CXCR2-dependent and independent (i.e., through up regulated CXCR1).

CXCL12 is capable of modulating the activity of CA1 hippocampal neurons through modulation of voltage-dependent channels (Na+, K+ and Ca2+), activation of G-protein-activated inward rectifier potassium current and increase in neurotransmitter release (glutamate, dopamine and γ-amino butyric acid) (Guyon and Nahon, 2007). A growing body of evidence indicates that the chemokine CXCL12 has neuroprotective abilities in a wide variety of neurotoxic injuries presumably through modulation of the activity of CA1 hippocampal neurons to counter the neurotoxic stress (Meucci et al., 1998; Dugas et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Shyu et al., 2008). Application of CXCL12 significantly increased the survival of CXCL12-treated hippocampal and cortical neurons (Meucci et al., 1998; Dugas et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2008). Furthermore, the neuroprotective role of CXCL12 became evident in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease where loss of CXCL12 contributed to impaired learning presumably due to dendritic regression and spine loss (Parachikova and Cotman, 2007). Like MIP-2, CXCL12 can also activate PI-3-K, ERK and cAMP-dependent transcription factor CREB survival pathways in neurons that may afford neuroprotection (Floridi et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2009; Sengupta et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009). Activation of the chemokine receptor CXCR7 by CXCL12 also activated PI-3-K and ERK pathways that may stabilize the survival of astrocytes when challenged by neurotoxic agents like Aβ (Odemis et al., 2010). Loss of ADAM17 upon Aβ treatment seen in our study is in agreement with observed decreased levels of ADAM17 in AD (Bernstein et al., 2009). Interestingly, activation of PI-3-K and ERK pathways by HSV-2 antiapoptotic gene ICP10PK in neurons has been shown to release the chemokine CX3CL1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (neuronally derived) to provide neuroprotection (Laing et al., 2010). The broad neuroprotective role of CXCL12 became evident in a rat model of cerebral ischemia where CXCL12 not only protected neurons at and around the site of ischemic injury due to experimental cerebral infarction but also reduced the volume of cerebral infarct (Shyu et al., 2008). This neuroprotective effect was suggested to be due to the CXCL12-dependent mobilization of bone marrow hematopoietic cells to the site of cerebral infarction that have the potential of supporting the repair of the infarcted area.

Neurons incubated with CXCL12 also liberate ADAM17 (Cook et al., 2010). The soluble chemokine CX3CL1 is also neuroprotective in nature by activating Akt and ERK1/2 similar to CXCL12 (Re and Przedborski, 2006). This chemokine-mediated chemokine release amplifies the neuroprotection cascade. In this study, CXCL12, but not MIP2, was capable of retaining the level of ADAM17 protein that was lost upon Aβ administration. Therefore, in addition to convergence of signaling for survival cascades, some differential signaling between CXCL12 and MIP-2 is also noted.

An additional goal of this study was to determine whether chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 suppress cerebral lipid peroxidation associated with Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. To our knowledge this is the first report that MIP-2 and CXCL12 pretreatment can indeed prevent such Aβ-induced oxidative damage. This indicates the involvement of multiple neuroprotective mechanisms of investigated chemokines.

Next, we investigated involvement of PAK in chemokines mediated protection following Aβ exposure. p21-activated kinases (PAKs) are effectors of small Rho GTPases, Rac1 and Cdc42 and active PAK promotes spine morphogenesis by retaining drebrin at the synapses and inactivating cofilin, an actin severing protein. PAK is a downstream effector of CXCR2 and CXCR4 signaling pathways (Wang et al., 2002; Volinsky et al., 2006). The level of active PAK correlates with an increase in the number of excitatory synapses. Operation of a GIT1/PIX/Rac/PAK signaling module locally at the spine level through phosphorylation and activation of myosin II regulatory light chain (MLC) has been reported (Zhang et al., 2005). Interestingly, total PAK1/2/3 was increased AD patients only in the early stages of AD but the level decreased in moderate and severe stages of AD (Nguyen et al., 2008). A similar increase in total PAK in terms of its staining in the hippocampal neurons was observed in our model similar to early AD. Loss of PAK1 and PAK3 has been observed in the neurons in late stages of human AD. Moreover, in the APP Swedish transgenic mouse model (Tg2576) loss of PAK1 and PAK3 contributes to defective dendritic spines and cognitive deficits and reduced expression and activity of PAK1 and PAK3 in temporal cortex and hippocampus correlated with concurrent loss of spine actin-regulatory protein drebrin (Zhao et al., 2006). In the Zhao study, PAK1 was observed to be intensely granular in distribution. Aβ–induced aberrant translocation of PAK from the cytosol to the particulate membranous fractions can have adverse effects on the dendritic spine morphology, but this can be prevented by kinase-active but not kinase-dead PAK (Ma et al., 2008). Since active PAK can be generated through ligand activation of CXCR2 and CXCR4 (Wang et al., 2002; Volinsky et al., 2006), it follows that in our study the ICV pretreatment of the hippocampus with MIP2 and CXCL12 would have generated enough active PAK to counteract its Aβ–induced aberrant translocation. The PAK mediated pathway provides some mechanistic insight into how MIP-2 or CXCL12 can provide protection from Aβ-induced loss of dendritic spines.

In summary, we report here a neuroprotective role for chemokines MIP-2 and CXCL12 in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, as evaluated by morphometry of neurons from cerebral and hippocampal cultures in vitro and pyramidal neurons from mouse CA1 hippocampal area in vivo. Chemokine pretreatment afforded prevention of Aβ-induced dendritic regression and neuronal apoptosis, maintenance of ADAM17 levels in vitro, and blocked both the aberrant translocation of PAK and the increase of F2-isoprostanes in vivo. In addition to quantitative evaluation of the MIP2 and CXCL12 mediated neuroprotection, this study provides mechanistic insight into chemokine-mediated neuroprotective pathways that indicate a protective role for chemokine receptors CXCR1, CXCR2 and CXCR4. Our findings suggest that controlled regulation of chemokines may provide an effective therapeutic strategy for suppressing neuronal damage and slowing progression of neurodegenerative processes.

Research Highlights.

In this study, we examined the neuroprotective ability of the chemokines MIP2 and CXCL12 against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity

Pretreatment with MIP-2 or SDF-1α significantly protected neurons from Aβ-induced dendritic regression and apoptosis in vitro through activation of Akt, ERK1/2 and maintenance of metalloproteinase ADAM17 especially with SDF-1α.

Intra-cerebroventricular (ICV) injection of Aβ led to reduction in dendritic length and spine density of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 area of the hippocampus and increased oxidative damage 24 h following the exposure.

The Aβ-induced morphometric changes of neurons and increase in biomarkers of oxidative damage, F2-isoprostanes, was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with the chemokines MIP-2 or SDF-1α.

Additionally, MIP-2 or SDF-1α was able to suppress the aberrant mislocalization of p21-activated kinase (PAK), one of the proteins involved in the maintenance of dendritic spines. Furthermore, MIP-2 also protected neurons against Aβ neurotoxicity in CXCR2−/− mice, potentially through observed up regulation of CXCR1 mRNA. Understanding the neuroprotective potential of chemokines is crucial in defining the role for their employment during the early stages of neurodegeneration.

Acknowldgements

This work was supported in whole or in part by National Institutes of Health Grants - Specialized Neuroscience Research Program grant U54NS041071-6 under Project 2 (G.F and A.R.), CA34590 (A.R.) and NS057223 (D.M.). This work was also supported by a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Ingram Professorship (A.R.). We acknowledge the VUMC cell imaging shared resource used in confocal studies (supported by NIH grant CA68485)

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- MIP-2

macrophage inflammatory protein-2

- SDF-1α

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

- ICV

intra-cerebroventricular (ICV)

- CXC

Cys-X-Cys motif

- CC

Cys-Cys motif

- CXCL

Cys-X-Cys-ligand

- CXCR

CXC receptor

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick-end labeling

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain

References

- Araujo DM, Cotman CW. Trophic effects of interleukin-4, −7 and −8 on hippocampal neuronal cultures: potential involvement of glial-derived factors. Brain Res. 1993;600:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90400-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrar S, Meng Y, Zhou Z, Todorovski Z, Huang WW, Jia Z. Regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation by p21-activated protein kinase 1 (PAK1) Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Stricker R, Lendeckel U, Bertram I, Dobrowolny H, Steiner J, Bogerts B, Reiser G. Reduced neuronal co-localisation of nardilysin and the putative alpha-secretases ADAM10 and ADAM17 in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome brains. Age (Dordr) 2009;31:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno V, Copani A, Besong G, Scoto G, Nicoletti F. Neuroprotective activity of chemokines against N-methyl-D-aspartate or beta-amyloid-induced toxicity in culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;399:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, Ryan AM, Pitts-Meek S, Hultgren B, Wood WI, Moore MW. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Sasse ME, Liu L, Cardona SM, Mizutani M, Savarin C, Hu T, Ransohoff RM. Scavenging roles of chemokine receptors: chemokine receptor deficiency is associated with increased levels of ligand in circulation and tissues. Blood. 2008;112:256–263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X, Forster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M. Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3. J Neurosci. 2009;29:288–299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Massaro CM, Palop JJ, Thwin MT, Yu GQ, Bien-Ly N, Bender A, Mucke L. Reelin depletion in the entorhinal cortex of human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2727–2733. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3758-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Hippensteel R, Shimizu S, Nicolai J, Fatatis A, Meucci O. Interactions between chemokines: regulation of fractalkine/CX3CL1 homeostasis by SDF/CXCL12 in cortical neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:10563–10571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danik M, Puma C, Quirion R, Williams S. Widely expressed transcripts for chemokine receptor CXCR1 in identified glutamatergic, gamma-aminobutyric acidergic, and cholinergic neurons and astrocytes of the rat brain: a single-cell reverse transcription-multiplex polymerase chain reaction study. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:286–295. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, Viola K, Fernandez SJ, Ferreira ST, Klein WL. Abeta oligomers induce neuronal oxidative stress through an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent mechanism that is blocked by the Alzheimer drug memantine. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:11590–11601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Vieira MN, Bomfim TR, Decker H, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Zhao WQ, Ferreira ST, Klein WL. Protection of synapses against Alzheimer’s-linked toxins: insulin signaling prevents the pathogenic binding of Abeta oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1971–1976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paola M, Buanne P, Biordi L, Bertini R, Ghezzi P, Mennini T. Chemokine MIP-2/CXCL2, acting on CXCR2, induces motor neuron death in primary cultures. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2007;14:310–316. doi: 10.1159/000123834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalaraja RM, Nanney LB, Du J, Qian Q, Yu Y, Devalaraja MN, Richmond A. Delayed wound healing in CXCR2 knockout mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:234–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas JC, Mandemakers W, Rogers M, Ibrahim A, Daneman R, Barres BA. A novel purification method for CNS projection neurons leads to the identification of brain vascular cells as a source of trophic support for corticospinal motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8294–8305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2010-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Patera AC, Pong-Kennedy A, Deno G, Gonsiorek W, Manfra DJ, Vassileva G, Zeng M, Jackson C, Sullivan L, Sharif-Rodriguez W, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Hedrick JA, Lundell D, Lira SA, Hipkin RW. Murine CXCR1 is a functional receptor for GCP-2/CXCL6 and interleukin-8/CXCL8. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:11658–11666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti MT, Cuello AC. Does a pro-inflammatory process precede Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:164–174. doi: 10.2174/156720511795255982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floridi F, Trettel F, Di Bartolomeo S, Ciotti MT, Limatola C. Signalling pathways involved in the chemotactic activity of CXCL12 in cultured rat cerebellar neurons and CHP100 neuroepithelioma cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;135:38–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter M, Uematsu K, Bullock SA, Kim Y, Hemmings HC, Jr, Nishi A, Greengard P, Nairn AC. Phosphorylation of spinophilin by ERK and cyclin-depende nt PK 5 (Cdk5) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3489–3494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409802102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goczalik I, Ulbricht E, Hollborn M, Raap M, Uhlmann S, Weick M, Pannicke T, Wiedemann P, Bringmann A, Reichenbach A, Francke M. Expression of CXCL8, CXCR1, and CXCR2 in neurons and glial cells of the human and rabbit retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4578–4589. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon A, Nahon JL. Multiple actions of the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha on neuronal activity. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38:365–376. doi: 10.1677/JME-06-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horuk R, Martin AW, Wang Z, Schweitzer L, Gerassimides A, Guo H, Lu Z, Hesselgesser J, Perez HD, Kim J, Parker J, Hadley TJ, Peiper SC. Expression of chemokine receptors by subsets of neurons in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 1997;158:2882–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking MP, Liu L, Ransohoff RM, Lane TE. A protective role for ELR+ chemokines during acute viral encephalomyelitis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000648. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking MP, Tirotta E, Ransohoff RM, Lane TE. CXCR2 signaling protects oligodendrocytes and restricts demyelination in a mouse model of viral-induced demyelination. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Sawada M, Haneda M, Ishida Y, Isobe K. Amyloid-beta peptides induce several chemokine mRNA expressions in the primary microglia and Ra2 cell line via the PI3K/Akt and/or ERK pathway. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MZ, Brandimarti R, Shimizu S, Nicolai J, Crowe E, Meucci O. The chemokine CXCL12 promotes survival of postmitotic neurons by regulating Rb protein. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1663–1672. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing JM, Smith CC, Aurelian L. Multi-targeted neuroprotection by the HSV-2 gene ICP10PK includes robust bystander activity through PI3-K/Akt and/or MEK/ERK-dependent neuronal release of vascular endothelial growth factor and fractalkine. J Neurochem. 2010;112:662–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laske C, Stellos K, Eschweiler GW, Leyhe T, Gawaz M. Decreased CXCL12 (SDF-1) plasma levels in early Alzheimer’s disease: a contribution to a deficient hematopoietic brain support? J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:83–95. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren HB, Lopez-Picon FR, Brandt AM, Rios-Rojas CJ, Holopainen IE. Transcriptome analysis of the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cell region after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus in juvenile rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi E, Strizki JM, Ulrich AM, Zhang W, Fu L, Wang Q, O’Connor M, Hoxie JA, Gonzalez-Scarano F. CXCR-4 (Fusin), a co-receptor for the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), is expressed in the human brain in a variety of cell types, including microglia and neurons. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limatola C, Ciotti MT, Mercanti D, Santoni A, Eusebi F. Signaling pathways activated by chemokine receptor CXCR2 and AMPA-type glutamate receptors and involvement in granule cells survival. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;123:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WH, Nebhan CA, Anderson BR, Webb DJ. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) induces actin assembly in dendritic spines to promote their development and potentiate synaptic strength. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:36010–36020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Darnall L, Hu T, Choi K, Lane TE, Ransohoff RM. Myelin repair is accelerated by inactivating CXCR2 on nonhematopoietic cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9074–9083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1238-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DY, Tang CH, Yeh WL, Wong KL, Lin CP, Chen YH, Lai CH, Chen YF, Leung YM, Fu WM. SDF-1alpha up-regulates interleukin-6 through CXCR4, PI3K/Akt, ERK, and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Fischer FR, Hancock WW, Dorf ME. Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and KC induce chemokine production by mouse astrocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:4015–4023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QL, Yang F, Calon F, Ubeda OJ, Hansen JE, Weisbart RH, Beech W, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. p21-activated kinase-aberrant activation and translocation in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:14132–14143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708034200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meucci O, Fatatis A, Simen AA, Bushell TJ, Gray PW, Miller RJ. Chemokines regulate hippocampal neuronal signaling and gp120 neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14500–14505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meucci O, Fatatis A, Simen AA, Miller RJ. Expression of CX3CR1 chemokine receptors on neurons and their role in neuronal survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8075–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090017497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D, Aschner M. Measurement of isoprostanes as markers of oxidative stress in neuronal tissue. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1214s39. Chapter 12, Unit12 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D, Montine TJ, Zaja-Milatovic S, Madison JL, Bowman AB, Aschner M. Morphometric analysis in neurodegenerative disorders. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2010;12:1–14. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1216s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D, Zaja-Milatovic S, Montine KS, Horner PJ, Montine TJ. Pharmacologic suppression of neuronal oxidative damage and dendritic degeneration following direct activation of glial innate immunity in mouse cerebrum. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1518–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ, Rostene W, Apartis E, Banisadr G, Biber K, Milligan ED, White FA, Zhang J. Chemokine action in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11792–11795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3588-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Milatovic D, Gupta RC, Valyi-Nagy T, Morrow JD, Breyer RM. Neuronal oxidative damage from activated innate immunity is EP2 receptor-dependent. J Neurochem. 2002;83:463–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow JD, Hill KE, Burk RF, Nammour TM, Badr KF, Roberts LJ., 2nd A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel NF, Barzik M, Raman D, Sobolik-Delmaire T, Sai J, Ham AJ, Mernaugh RL, Gertler FB, Richmond A. VASP is a CXCR2-interacting protein that regulates CXCR2-mediated polarization and chemotaxis. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1882–1894. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D, Stangel M. Expression of the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in rat oligodendroglial cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;128:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Galvan V, Huang W, Banwait S, Tang H, Zhang J, Bredesen DE. Signal transduction in Alzheimer disease: p21-activated kinase signaling requires C-terminal cleavage of APP at Asp664. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1065–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic M. The Pak1 kinase: an important regulator of neuronal morphology and function in the developing forebrain. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;37:187–202. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odemis V, Boosmann K, Heinen A, Kury P, Engele J. CXCR7 is an active component of SDF-1 signalling in astrocytes and Schwann cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1081–1088. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parachikova A, Cotman CW. Reduced CXCL12/CXCR4 results in impaired learning and is downregulated in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico D. The neurobiology of isoprostanes and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:930–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico D, Sung S. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative imbalance: early functional events in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:171–175. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico D, V MYL, Trojanowski JQ, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA. Increased F2-isoprostanes in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for enhanced lipid peroxidation in vivo. Faseb J. 1998;12:1777–1783. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puma C, Danik M, Quirion R, Ramon F, Williams S. The chemokine interleukin-8 acutely reduces Ca(2+) currents in identified cholinergic septal neurons expressing CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptor mRNAs. J Neurochem. 2001;78:960–971. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re DB, Przedborski S. Fractalkine: moving from chemotaxis to neuroprotection. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:859–861. doi: 10.1038/nn0706-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau V, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Commenges D, Helmer C, Dartigues JF. Aluminum and silica in drinking water and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive decline: findings from 15-year follow-up of the PAQUID cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:489–496. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai J, Raman D, Liu Y, Wikswo J, Richmond A. Parallel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent and Src-dependent pathways lead to CXCL8-mediated Rac2 activation and chemotaxis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:26538–26547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805611200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta R, Burbassi S, Shimizu S, Cappello S, Vallee RB, Rubin JB, Meucci O. Morphine increases brain levels of ferritin heavy chain leading to inhibition of CXCR4-mediated survival signaling in neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2534–2544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5865-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbatykh I, Carpenter DO. The role of metals in the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:191–205. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Yen PS, Su CY, Chen DC, Wang HJ, Li H. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha promotes neuroprotection, angiogenesis, and mobilization/homing of bone marrow-derived cells in stroke rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:834–849. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinsky N, Gantman A, Yablonski D. A Pak- and Pix-dependent branch of the SDF-1alpha signalling pathway mediates T cell chemotaxis across restrictive barriers. Biochem J. 2006;397:213–222. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Sai J, Carter G, Sachpatzidis A, Lolis E, Richmond A. PAK1 kinase is required for CXCL1-induced chemotaxis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7100–7107. doi: 10.1021/bi025902m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JY, Shum AY, Chao CC, Kuo JS, Wang JY. Production of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 following hypoxia/reoxygenation in glial cells. Glia. 2000;32:155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Luo W, Reiser G. Activation of protease-activated receptors in astrocytes evokes a novel neuroprotective pathway through release of chemokines of the growth-regulated oncogene/cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant family. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3159–3168. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Luo W, Stricker R, Reiser G. Protease-activated receptor-1 protects rat astrocytes from apoptotic cell death via JNK-mediated release of the chemokine GRO/CINC-1. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1046–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yang F, Fu Y, Huang X, Wang W, Jiang X, Gritsenko MA, Zhao R, Monore ME, Pertz OC, Purvine SO, Orton DJ, Jacobs JM, Camp DG, Smith RD, 2nd, Klemke RL. Spatial Phosphoprotein Profiling Reveals a Compartmentalized Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase Switch Governing Neurite Growth and Retraction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:18190–18201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson K, Fan GH. Macrophage inflammatory protein 2 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide (1–42)-mediated hippocampal neuronal apoptosis through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:757–765. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Peng H, Cui M, Whitney NP, Huang Y, Zheng JC. CXCL12 increases human neural progenitor cell proliferation through Akt-1/FOXO3a signaling pathway. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1157–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia MQ, Hyman BT. Chemokines/chemokine receptors in the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:32–41. doi: 10.3109/13550289909029743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Webb DJ, Asmussen H, Niu S, Horwitz AF. A GIT1/PIX/Rac/PAK signaling module regulates spine morphogenesis and synapse formation through MLC. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3379–3388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]