Abstract

It is challenging to find membrane mimics that stabilize the native structure, dynamics, and functions of membrane proteins. In a recent advance, nanodiscs have been shown to provide a bilayer environment compatible with solution NMR. Increasing the lipid to “belt” peptide ratio expands their diameter, slows their reorientation rate, and enables the protein-containing discs to be aligned in a magnetic field for Oriented Sample solid-state NMR. Here, we compare the spectroscopic properties of membrane proteins with between one and seven trans-membrane helices in q=0.1 isotropic bi-celles, ∼10 nm diameter isotropic nanodiscs, ∼30 nm diameter magnetically aligned macrodiscs, and q=5 bicelles.

Substantial progress has been made in determining the structures of membrane proteins in recent years.1,2 However, the same major obstacles to wider application of NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography to helical membrane proteins present at the beginning of the field thirty five years ago3 are still present; these are primarily the identification and optimization of detergent/lipid environments that simultaneously meet the strict sample requirements of each method and stabilize the native structure of the protein. Micelles,4 isotropic bicelles,5 and other detergent/lipid assemblies are used as membrane mimics in solution NMR. However, solid-state NMR is distinguished by its ability to study membrane proteins in proteoliposomes6 and in magnetically aligned bicelles7. Most X-ray diffraction structures have been obtained from membrane proteins crystallized from monoolein in lipid cubic phase8 or from detergents or bicelles9.

Bicelles are characterized by the parameter q, the molar ratio of the “long-chain” phospholipid (e.g. DMPC) to the “short-chain” phospholipid (e.g. DHPC) or detergent (Triton X-100 or CHAPSO). There are two categories of bicelles. Isotropic bicelles have q<1.5, although even for small membrane proteins q<0.5 is required for the protein to give tractable NMR spectra. Magnetically aligned bicelles have q>2.5, which are useful for Oriented Sample (OS) solid-state NMR because the integral membrane protein is immobilized and aligned along with the phospholipids in the bilayers.

Recently, protein-containing nanodiscs have been introduced as a soluble bilayer environment compatible with many biophysical experiments, including solution NMR.10 A nano-disc is a synthetic model membrane system with a diameter of ∼10 nm, consisting of about 150 phospholipids surrounded by a membrane scaffold protein (MSP) or amphipathic α-helical peptides derived from apolipoprotein A-1.11 Integral membrane proteins can be inserted into the central bilayer portion of the nanodiscs, and the assemblies remain soluble and monodisperse in aqueous solution. They can accommodate a wide variety of saturated or unsaturated phospholipids. Significantly, protein-containing nanodiscs are “detergent-free”, which minimizes the possibility that the membrane environment will result in the distortion or denaturation of the native protein structure.

Since nanodiscs reorient relatively rapidly in aqueous solution, they have received particular attention in the quest for conditions that yield high-resolution solution NMR spectra of membrane proteins in bilayer environments;12-15 the principal alternatives remain detergent micelles and isotropic bicelles. In solution NMR, the line widths and consequently the spectral resolution are a function of the size and shape of the poly-peptide, its oligomeric state, the nature of the detergent/lipid assembly, especially the q value of isotropic bicelles, and the temperature. Most efforts have been aimed at minimizing the size of the protein-lipid complexes in order to decrease the rotational correlation time and obtain resonances with the narrowest line widths. However, we have found that in general the line widths of resonances from helical membrane proteins in nanodiscs are substantially broader than those observed in micelles or low q bicelles.

Here we demonstrate the opportunities presented by increasing the diameter from ∼10 nm (nanodiscs) to ∼30 nm (macrodiscs) (Figure S1). In both cases, the discs consist of “long-chain” phospholipid bilayers encircled by a 14-residue peptide (Ac-DYLKAFYDKLKEAF-NH2), which is a truncated analog of the class A amphipathic α-helical peptide 18A that forms a discoidal bilayer particle when mixed with phospholipids, and has been used previously as a model of lipid-binding sites for apolipoprotein A-I.16 The diameter of the phospholipid bilayer disc can be adjusted by changing the length of the MSP17 or the molar ratio of the phospholipids and the 14-residue peptide. The large increase in diameter dramatically alters the behavior of the bilayer discs in aqueous solution. Proteins in nanodiscs undergo isotropic reorientation with a frequency similar to that observed for q=0.5 at approximately the same rates as in q=0.5 isotropic bicelles; in contrast, protein-containing macrodiscs form magnetically alignable bilayers at temperatures above the gel-to-liquid crystalline transition temperature of the phospholipids (Figure S2), similar to q>2.5 bicelles.

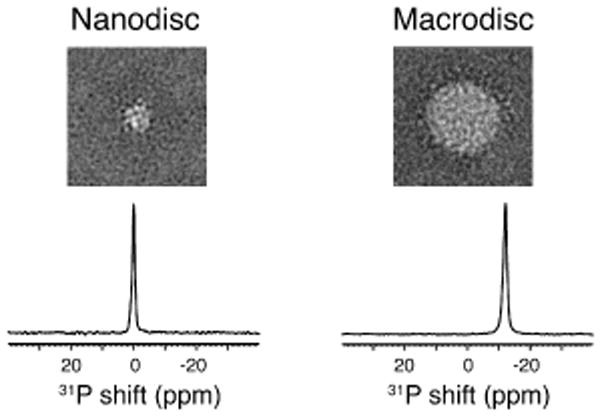

In Figure 1, single particle electron microscopy shows that a nanodisc has a diameter of ∼10 nm and that a typical macrodisc has a much larger diameter of ∼ 30 nm. The difference in diameters has a dramatic effect on their 31P NMR spectra. In the case of nanodiscs, the 31P NMR chemical shift corresponds to the isotropic value of a phosphodiester group. In contrast, macrodiscs have their 31P resonance shifted by ∼12 ppm. This frequency shift is crucial evidence that the phospholipids in macrodiscs align with their normals perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic field. Also, it is possible to ‘flip’ the direction of alignment of the macrodisc from perpendicular to parallel by adding lanthanide ions, as previously demonstrated for q>2.5 bicelles.18 The narrow line widths in the 31P NMR spectra in Figure 1 demonstrate that the phospholipids are arranged homogeneously in the samples, and that the macrodiscs are uniformly aligned in the magnetic field. The 31P NMR data indicate that the isotropic reorientation of protein-containing nanodiscs is rapid enough for solution NMR experiments. In contrast, the macrodiscs immobilize and align the proteins along with the phospholipids for OS solid-state NMR experiments. Unoriented macrodiscs can also be used for Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) solid-state NMR experiments.19,20

Figure 1.

Top row: Representative two-dimensional class average of negatively stained protein-containing nanodiscs (left) and macrodiscs (right). Each side of the display panels is 57.2 nm. Bottom row: 31P NMR spectra of the phospholipids in protein-containing nanodiscs (left) and macrodiscs (right) at 40°C. The molar ratios of DMPC to the 14-residue peptide are 1.67 for the nanodiscs and 13.3 for the macrodiscs.

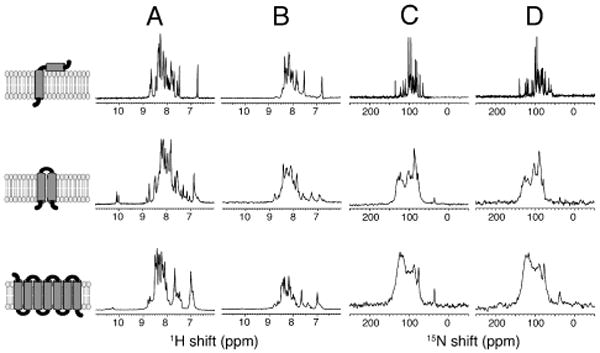

One-dimensional 15N-edited 1H solution NMR spectra of the three uniformly 15N labeled membrane proteins are compared in Figure 2. Micelle samples (q=0) with high detergent concentrations generally give solution NMR spectra with the best apparent resolution,21 however, there are now multiple examples of proteins where the addition of a small amount of long-chain phospholipid improves the spectral quality. In particular, resonances missing in q=0 micelle spectra can often be observed in q=0.1 isotropic bicelle spectra. Since q=0 and q=0.1 bicelles act as effectively spherical assemblies of detergents, the line widths of the protein resonances are similar; however, they are both problematic in terms of providing an environment conducive to the membrane protein retaining its native structure and function, especially at the high concentrations of detergent and high temperatures required to obtain the best resolved spectra.21 The membrane proteins compared in Figure 2 contain between 46 and 350 residues, and between one and seven trans-membrane helices. Therefore, they represent a broad range of the helical membrane proteins found in bacteria, viruses, and humans. The top row of Figure 2 contains spectra from the membrane-bound form of Pf1 coat protein, which has 46 residues and one hydrophobic trans-membrane helix.22 The middle row contains spectra of the p7 protein from human hepatitis C virus, which has 63 residues and two trans-membrane helices.23 The bottom row contains spectra of the human chemokine receptor CXCR1, a GPCR with 350 residues and seven trans-membrane helices.24

Figure 2.

NMR spectra of uniformly 15N-labeled membrane proteins in four different membrane-mimic environments. (A) q=0.1 bicelles. (B) Nanodiscs. (C) Macrodiscs. (D) q=5 bicelles. From top to bottom, the leftmost column contains cartoon representations of the membrane proteins with one (Pf1 coat protein), two (p7 protein), and seven (CXCR1) trans-membrane helices. (A and B) 15N-edited 1H solution NMR spectra. (C and D) OS solid-state 15N NMR spectra. The nanodisc and macrodisc samples are as described in Figure 1.

For the smaller membrane proteins, Pf1 coat protein and p7, resonances from all amide sites are observed in the solution NMR spectra (as verified by completely assigned two-dimensional HSQC spectra). However, the resonances from the nanodisc samples are considerably broader than those from the isotropic bicelle samples. In general, protein resonances from nanodisc samples have about the same line widths and numbers of observable signals as those in q=0.5 isotropic bicelles (Figure S3). While the line widths obtained from the same protein in nanodiscs are broader than those from the same protein in optimized q=0 micelles or q=0.1 isotropic bicelles, the loss in spectra resolution may be offset in some cases by the advantages of working in a “detergent-free” environment. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that nanodiscs will be the optimal choice for resolution in solution NMR spectra of small membrane proteins, at least at their present stage of development.

The situation for CXCR1 is quite different. The only signals observable in Figure 2A and B are from mobile residues at the N- and C- termini of the protein.25 Forty-four signals in Figure 2A have been assigned to individual residues. The spectrum in Figure 2B is considerably broader and weaker, and it is likely that even signals from some of the terminal residues are so broad that they are not observable. In any case, helical membrane proteins as large as GPCRs are unlikely to yield solution NMR spectra with sufficient resolution to be useful in structural studies. We have already shown that no significant improvements result from high levels of deuteration and the application of “TROSY-class” pulse sequences for CXCR1 in q=0.1 isotropic bicelles at 800 MHz.25

Macrodiscs take on an entirely different role in solid-state NMR of membrane proteins. One-dimensional 15N solid-state NMR spectra of the three membrane proteins are compared in macrodiscs (Figure 2C) and q=5 magnetically aligned bilayers (Figure 2D). In general the spectra appear to have slightly better resolution when the protein is immobilized and aligned in DMPC: Triton X-100 q=5 bicelles26 (Figure 2D) than in macrodiscs (Figure 2C). However, the macrodiscs have the advantage of being “detergent-free”, therefore the samples have the potential to be more stable and less likely to induce distortions or denaturation of the proteins. This may outweigh the slight loss of resolution in studies where the details of the protein structure and its function are at a premium.

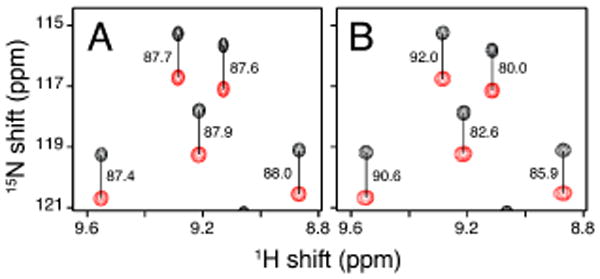

Another entirely different use of macrodiscs in solution NMR is as an alignment medium to measure residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) of soluble, globular proteins. RDCs are an important source of structural constraints in solution NMR studies. Much like high q bicelles,27 macrodiscs induce weak alignment in soluble, globular proteins in aqueous solution. As an example, the measurement of 1H-15N RDCs for chemokine interleukin-8 weakly aligned by the presence of macrodiscs in aqueous solution is illustrated in Figure 3. Importantly, there is no detectable line broadening of the resonances or chemical shift changes in the presence of the macrodiscs.

Figure 3.

Representative region of 1H-15N IPAP-HSQC spectra of uniformly 15N labeled interleukin-8 at 40°C. (A) Isotropic in aqueous solution. (B) Weakly aligned in aqueous solution by the addition of macrodiscs in a final concentration of 10% DMPC (w/v). The measured values of one-bond 1H-15N splitting are marked in Hz.

Macrodiscs demonstrate that the diameter of bilayer discs encircled by the 14-residue peptides derived from apolipoprotein A-1 can be varied by at least three-fold by changing the lipid to peptide molar ratio. Nanodiscs and macrodiscs provide complementary lipid environments for NMR and other physical and functional studies of membrane proteins. The NMR spectra in the figures demonstrate that nanodiscs with ∼10 nm diameter and megadiscs with ∼30 nm diameter bridge between the relatively rapid isotropic motion associated with solution NMR spectroscopy and the complete magnetic alignment and immobilization associated with OS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Although nanodiscs do not compete well with micelles and low q isotropic bicelles for optimal resolution in solution NMR spectra of membrane proteins, the resolution attainable with macrodiscs is similar to that of the best high q bicelles in OS solid-state NMR spectra. Both nanodiscs and macrodiscs have the advantage of providing a “detergent-free” bilayer environment that reduces the possibility of distorting or denaturing the protein structures. In addition, macrodiscs provide an alignment medium for soluble, globular proteins, enabling the measurement of RDCs. Thus, macrodiscs have the potential to play several complementary roles to nanodiscs and other membrane-mimics in NMR studies of membrane proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Girvin for providing the sequence of the 14-residue peptide. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and utilized the Biomedical Technology Resource for NMR Molecular Imaging of Proteins at the University of California, San Diego, which is supported by grant P41EB002031.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Details of experimental procedures and Figures S1-S3. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/listAll/list.

- 2.http://www.drorlist.com/nmr/MPNMR.html.

- 3.Tanford C, Reynolds JA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;457:133–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(76)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross TA, Opella SJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;92:478–484. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vold RR, Prosser RS, Deese AJ. J Biomol NMR. 1997;9:329–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1018643312309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis BA, Harbison GS, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4671–4679. doi: 10.1021/bi00338a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Angelis AA, Nevzorov AA, Park SH, Howell SC, Mrse AA, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15340–15341. doi: 10.1021/ja045631y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landau EM, Rosenbusch JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14532–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faham S, Bowie JU. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nath A, Atkins WM, Sligar SG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2059–2069. doi: 10.1021/bi602371n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchie TK, Grinkova YV, Bayburt TH, Denisov IG, Zolnerciks JK, Atkins WM, Sligar SG. Methods in Enzymol. 2009;464:211–231. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyukmanova EN, Shenkarev ZO, Paramonov AS, Sobol AG, Ovchinnikova TV, Chupin VV, Kirpichnikov MP, Blommers MJ, Arseniev AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2140–2141. doi: 10.1021/ja0777988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raschle T, Hiller S, Yu TY, Rice AJ, Walz T, Wagner G. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17777–17779. doi: 10.1021/ja907918r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gluck JM, Wittlich M, Feuerstein S, Hoffmann S, Willbold D, Koenig BW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12060–12061. doi: 10.1021/ja904897p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenkarev ZO, Lyukmanova EN, Paramonov AS, Shingarova LN, Chupin VV, Kirpichnikov MP, Blommers MJ, Arseniev AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5628–5629. doi: 10.1021/ja9097498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anantharamaiah GM, Jones JL, Brouillette CG, Schmidt CF, Chung BH, Hughes TA, Bhown AS, Segrest JP. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10248–10255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Lazarides AA, Sligar SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3477–3487. doi: 10.1021/ja0393574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prosser RS, Hunt SA, DiNatale JA, Vold RR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118:269–270. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Kijac AZ, Sligar SG, Rienstra CM. Biophys J. 2006;91:3819–3828. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kijac AZ, Li Y, Sligar SG, Rienstra CM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13696–13703. doi: 10.1021/bi701411g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonnell PA, Shon K, Kim Y, Opella SJ. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:447–463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SH, Marassi FM, Black D, Opella SJ. Biophys J. 2010;99:1465–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook GA, Opella SJ. Eur Biophys J. 2010;39:1097–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0533-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SH, Prytulla S, De Angelis AA, Brown JM, Kiefer H, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7402–7403. doi: 10.1021/ja0606632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SH, Casagrande F, Das BB, Albrecht L, Chu M, Opella SJ. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2371–2380. doi: 10.1021/bi101568j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SH, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12552–12553. doi: 10.1021/ja1055565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjandra N, Bax A. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.