Abstract

In asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, activation of Gq-protein–coupled receptors causes bronchoconstriction. In each case, the management of moderate-to-severe disease uses inhaled corticosteroid (glucocorticoid)/long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist (LABA) combination therapies, which are more efficacious than either monotherapy alone. In primary human airway smooth muscle cells, glucocorticoid/LABA combinations synergistically induce the expression of regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2), a GTPase-activating protein that attenuates Gq signaling. Functionally, RGS2 reduced intracellular free calcium flux elicited by histamine, methacholine, leukotrienes, and other spasmogens. Furthermore, protection against spasmogen-increased intracellular free calcium, following treatment for 6 h with LABA plus corticosteroid, was dependent on RGS2. Finally, Rgs2-deficient mice revealed enhanced bronchoconstriction to spasmogens and an absence of LABA-induced bronchoprotection. These data identify RGS2 gene expression as a genomic mechanism of bronchoprotection that is induced by glucocorticoids plus LABAs in human airway smooth muscle and provide a rational explanation for the clinical efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid (glucocorticoid)/LABA combinations in obstructive airways diseases.

Keywords: adrenoreceptor, beta-2-adrenergic receptor, protein kinase A, glucocorticoid receptor, NR3C1

Asthma affects up to 300 million people globally, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is predominantly caused by cigarette smoking, is predicted to become the third leading cause of death. Both diseases are characterized by airflow limitation due, at least in part, to bronchoconstriction. Therapeutically, long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists (LABAs), short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABAs), and inhaled glucocorticoids, clinically known as inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), represent cornerstone treatments for both asthma and COPD (1, 2). Whereas SABAs provide short-term symptomatic relief of bronchospasm, international practice guidelines recommend ICS/LABA combination inhalers for asthma patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled on ICS monotherapy (1). Moreover, clinical guidelines recommend long-acting bronchodilators as a first-line therapy for mild COPD and ICS/LABA combinations for more severe disease (1, 2). In each case, large, multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials convincingly show enhanced clinical benefits to ICS/LABA combinations that are not achieved by either component alone (2–4). However, despite the benefits achieved by these combination therapies, there is a paucity of mechanistic information accounting for these effects.

Several mediators, including acetylcholine, histamine, cysteinyl-leukotrienes, and certain prostanoids, promote bronchoconstriction, which is a defining characteristic of asthma and COPD (1, 2, 5). Such mediators contract airway smooth muscle (ASM) by activating G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that typically signal to phospholipase Cβ via the heterotrimeric G protein, Gq (6, 7). This leads to the formation of inositol(1,4,5)trisphosphate (IP3), which stimulates the release of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) from internal stores, and diacylglycerol, an activator of protein kinase C, which, together with IP3, promotes ASM contraction (6, 7). Conversely, β2-adrenoceptor agonists are bronchodilators that functionally antagonize ASM contraction irrespective of the constrictor (8). Current dogma holds that β2-adrenoceptor agonism activates the cAMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) pathway to phosphorylate downstream targets that oppose actin–myosin cross-bridge formation and reduce ASM force generation (8).

Signaling from GPCRs is terminated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (9), which enhance the rate at which Gα subunits hydrolyze GTP. We show that the expression of the regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2), a Gq selective GAP (10, 11), is transcriptionally up-regulated by LABAs and that this is enhanced and prolonged by glucocorticoids in human ASM. In vitro RGS2 down-regulates signaling from multiple Gq-coupled receptors and in vivo imparts bronchoprotection against spasmogens. Increased RGS2 gene expression therefore represents a genomic mechanism of bronchoprotection, which may contribute to the therapeutic activity of ICS/LABA combination therapies.

Results

RGS2 Expression Is Induced by LABAs and Enhanced by Glucocorticoids.

Primary human ASM cells were treated with maximally effective concentrations of dexamethasone, the LABAs, salmeterol xinafoate (salmeterol), formoterol fumarate (formoterol), and the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, before analysis for RGS2 mRNA (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A) (12). Although RGS2 mRNA was modestly induced by dexamethasone at all times, the LABAs significantly induced RGS2 expression at 1 and 2 h, and forskolin induced RGS2 mRNA at all times tested. In the presence of LABAs or forskolin, dexamethasone significantly enhanced RGS2 expression at 1 and 2 h. This effect was more than the sum of the components and is therefore described as synergy. At 6 h, neither LABAs nor dexamethasone significantly increased RGS2 mRNA, yet the combination significantly induced RGS2 mRNA.

Fig. 1.

Expression of RGS2 in human ASM cells. (A) Primary human ASM cells were treated with combinations of 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex) or 100 nM salmeterol (Salm). Cells were harvested for real-time PCR analysis of RGS2 and GAPDH mRNAs (Upper) or unspliced RGS2 nuclear RNA (nRGS2) and U6 RNA (Lower). (Upper) Data (n = 9), expressed as RGS2/GAPDH, are plotted as fold relative to untreated (at t = 1 h) as means ± SE. (Lower) Data (n = 10) are plotted as nRGS2/U6 as means ± SE. Multiple comparisons at each time were made using ANOVA with a Bonferroni post test. Significance data relative to untreated samples are *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Significance data relative to Dex-treated samples are aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, and cP < 0.001. Significance data relative to Salm-treated samples are dP < 0.05, and eP < 0.01. (B) Primary human ASM cells were not stimulated (NS) or treated with Dex (1 μM), Salm (100 nM), or Dex (1 μM) + Salm (100 nM). After 2 h, actinomycin D (10 μg/mL) was added and RNA was harvested at 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min for RT-PCR analysis of RGS2 and GAPDH. Data (n = 7 for 15, 30, and 60 min; n = 3 for 120 and 240 min) expressed as RGS2/GAPDH are plotted as a percentage of their respective treatment at t = 0 (i.e., when actinomycin D was added) as means ± SE. (C) Cells as in A were treated with 300 nM fluticasone propionate (FP), 100 nM salmeterol (Salm), and 10 μM forskolin (Forsk) before Western blot analysis of RGS2 and GAPDH. Blots representative of four such experiments are shown. (D) Primary human ASM cells were treated with 100 nM salmeterol plus 300 nM fluticasone propionate (Salm + FP) before Western blotting for RGS2 and GAPDH. Blots representative of four experiments are shown. (E) Primary human ASM cells were left naive or infected with Ad5-PKI or Ad5-LacZ. After 24 h, cells were treated with 300 nM fluticasone propionate (FP) and/or 100 nM salmeterol (Salm) for 6 h before Western blot analysis for RGS2 and GAPDH. Blots representative of three such experiments are shown. Densitometric data for C and D are provided in Fig. S2.

To explore the mechanistic basis for this effect, unspliced nuclear RNA (nRNA) corresponding to the exon 1–intron A and exon 4–intron D splice junctions in RGS2 was examined as an index of transcription rate (Fig S1B). Because splicing reactions are not limiting and occur very rapidly (13), the transient accumulation of unspliced nRNA is a surrogate of transcription rate (14, 15). TaqMan PCR for the RGS2 exon 1–intron A slice junction revealed a very rapid increase induced by salmeterol that was further enhanced by dexamethasone (Fig. 1A). This effect had declined by 6 h, but in the presence of dexamethasone was still significantly induced. An identical effect was observed for the RGS2 exon 4–intron D junction (Fig. S1C).

To examine a role for mRNA stability, ASM cells were tested in standard actinomycin D chase experiments. Following either no treatment or stimulation with dexamethasone, salmeterol, or salmeterol plus dexamethasone for 2 h, actinomycin D was added, and decay of RGS2 mRNA was monitored by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). No significant changes in RSG2 mRNA stability were detected between any treatment group. Taken with the nRNA data, this clearly shows the increased RGS2 mRNA expression due to LABAs and that the enhancement and prolonged expression in the presence of glucocorticoid are primarily due to the modulation of gene transcription.

RGS2 protein expression revealed variable and barely detectible increases by the glucocorticoids, fluticasone propionate (FP), budesonide, and dexamethasone (Fig. 1C; Fig. S2 A and B; Fig. S3A). Conversely, salmeterol and formoterol strongly induced RGS2 expression, which peaked at 2 h (Fig. 1C; Figs. S2 and S3). This was mimicked by forskolin, but the duration of RGS2 expression was prolonged. The presence of FP further elevated salmeterol- and forskolin-induced RGS2 expression at 1 and 2 h, and, at times thereafter, RGS2 expression was dramatically prolonged (Fig. 1C). Indeed, salmeterol plus FP induced RGS2 protein from 45 min to 18 h posttreatment, with a plateau of near maximal expression between 2 and 8 h (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2). Similar data were described for salmeterol plus dexamethasone and formoterol plus budesonide (Figs. S2 and S3). The up-regulation of RGS2 expression by salmeterol or by salmeterol plus FP was attenuated by the β2-adrenoceptor selective antagonist, ICI 118,551 (Fig. S3C). This confirms the selectivity for the β2 adrenoceptors. Similarly, the ability of salmeterol or salmeterol plus dexamethasone to induce RGS2 expression was totally prevented by the RNA polymerase II inhibitor, actinomycin D, and is consistent with transcriptional control (Fig. S3D).

To explore the role of PKA, cells were infected with adenovirus overexpressing PKIα, a highly selective and potent inhibitor of PKA (16). Using this method, virtually all ASM cells express PKIα, and this inhibits cAMP response element (CRE) binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and CRE-dependent transcription (17, 18). Induction of RGS2 protein by salmeterol was blocked by Ad5-PKIα, but not by the control Ad5-lacZ (Fig. 1E). In the presence of salmeterol plus FP, RGS2 protein was strongly induced and was also inhibited by Ad-PKIα, but not by Ad5-LacZ (P < 0.001 relative to either naive or Ad5-LacZ using ANOVA with a Bonferroni post test). These data support a PKA-dependent mechanism for the induction of RGS2 by LABAs.

Repression of [Ca2+]i Flux by LABAs Is Prolonged by Glucocorticoid.

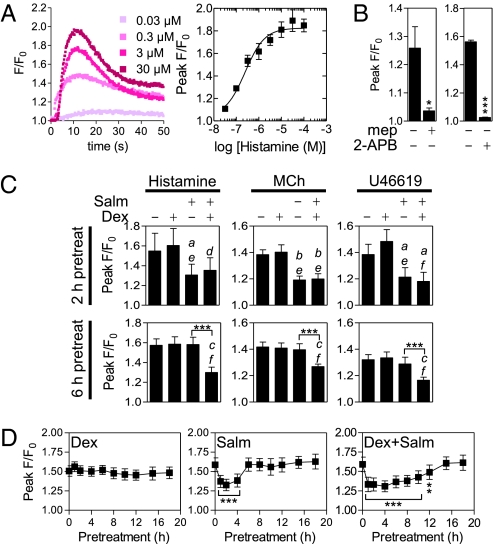

In human ASM, histamine increased [Ca2+]i with near maximal responses at 10 μM (Fig. 2A). This was blocked by mepyramine, a histamine H1 receptor antagonist (19), and 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB), an IP3R antagonist (20) (Fig. 2B). Because the H1 receptor couples to Gq (19), this confirms a Gq/IP3/IP3R pathway linked to [Ca2+]i flux. Similarly, the acetylcholine analog, methacholine, contracts ASM via the Gq-linked muscarinic M3 receptor (6, 19). In the current study, methacholine-induced [Ca2+]i was maximal at 30 μM and was blocked by 2-APB (Fig. S4 A and B). Likewise, the thromboxane analog, U46619, which is selective for the Gq-linked thromboxane receptor (TP) (19), maximally increased [Ca2+]i at 1 μM and this was blocked by 2-APB, again supporting a conventional Gq-linked pathway leading to elevated [Ca2+]i (Fig. S4 C and D).

Fig. 2.

Effect of dexamethasone and salmeterol on agonist-enhanced [Ca2+]i in human ASM cells. (A) Primary ASM cells loaded with Fluo4 were stimulated with various concentrations of histamine. Representative traces showing fluorescence/fluorescence at time 0 (F/F0) are plotted. Peak F/F0 from four such experiments are plotted as means ± SE. (B) Cells were treated as in A except that 50 nM mepyramine (mep) or 10 μM 2-APB were added 30 min before a 10-μM histamine challenge. Data (mep, n = 6; 2-APB, n = 8) are plotted as means of F/F0 ± SE. Significance was tested using a Student's t test where *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. (C) Cells were treated as in A, except that 100 nM salmeterol (Salm) and/or 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex) were added 2 or 6 h before 10 μM histamine, 30 μM methacholine (MCh), or a 1-μM U46619 challenge. Data (2 h pretreatment, n = 4; 6 h pretreatment, n = 8–10) expressed as peak F/F0 are plotted as means ± SE. Multiple comparisons were made using ANOVA with a Bonferroni post test. Significance data relative to untreated samples are aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, and cP < 0.001. Significance data relative to Dex-treated samples are dP < 0.05, eP < 0.01, and fP < 0.001. Significance between other groups is indicated where ***P < 0.001. (D) Cells were pretreated with Dex (1 μM), Salm (100 nM), or Dex (1 μM) + Salm (100 nM) for the indicated times before challenge with histamine (10 μM) and measurement of fluorescence. Peak F/Fo is plotted as means ± SE. Significance relative to F/Fo induced by histamine was tested by ANOVA with a Dunnett's post test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Because RGS2 expression was maximal 2 h after LABA addition and because this was prolonged to at least 6 h by glucocorticoid, the protective role of these treatments was tested on spasmogen-increased [Ca2+]i. Following a 2-h pretreatment, salmeterol and salmeterol plus dexamethasone, but not dexamethasone alone, significantly attenuated histamine-, methacholine-, or U46619-induced [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2C). However, after a 6-h pretreatment, only salmeterol plus dexamethasone significantly attenuated histamine-, methacholine-, and U46619-induced increases in [Ca2+]i relative to control, salmeterol, or dexamethasone alone (Fig. 2C). To explore this effect, ASM cells were pretreated with dexamethasone, salmeterol, or salmeterol plus dexamethasone for various times before stimulation with histamine (Fig. 2D). Whereas dexamethasone failed to alter histamine-induced [Ca2+]i, salmeterol significantly repressed [Ca2+]i following 1-, 2-, and 4-h pretreatments, and salmeterol plus dexamethasone provided significant protection with 1-to 12-h pretreatments (Fig. 2D). This illustrates the enhanced protective effect afforded by the LABA/glucocorticoid combination.

RGS2 Attenuates Agonist-Induced Increases in [Ca2+]i.

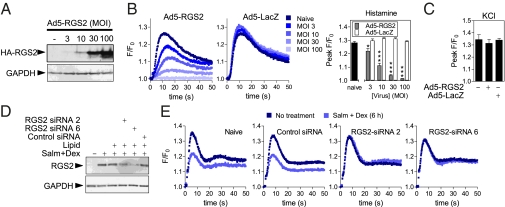

Following infection of primary human ASM cells with RGS2-expressing adenovirus, RGS2 expression correlated with multiplicity of infection (MOI) and reduced [Ca2+]i flux elicited by histamine (Fig. 3 A and B). At all MOIs, repression was significant relative to Ad5-LacZ and was reproduced for methacholine and U46619 (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4E). Similarly, bradykinin, LTB4, LTD4, and misoprostol, which act on the Gq-linked B1 and B2, BLT1 and BLT2, CysLT1 and CysLT2, and EP3 receptors, respectively (19), all elicited increased [Ca2+]i that was significantly repressed by Ad5-RGS2, but not by LacZ-expressing virus (Fig. S4F). Importantly, KCl-induced [Ca2+]i, a receptor-independent stimulus, was unaffected by Ad5-RGS2 (Fig. 3C). Thus, RGS2 attenuates procontractile responses produced by Gq-linked GPCR agonists in primary human ASM cells.

Fig. 3.

RGS2 attenuates agonist-induced [Ca2+]i primary human ASM cells. Primary human ASM cells were infected with the indicated MOIs of Ad5-RGS2.HA or Ad5-LacZ. (A) After 24 h, cells were harvested for Western blot analysis of HA-tagged RGS2. Blots are representative of four such experiments. (B) Following overnight incubation in serum-free media, cells were loaded with Fluo4 before stimulation with 10 μM histamine. Representative traces of F/Fo are shown and peak F/Fo data from four experiments are plotted as means ± SE. (C) ASM cells were infected with 100 MOI of Ad5-RGS2.HA or Ad5-LacZ or left naive. As in B, cells were challenged with 60 mM potassium chloride (KCl). Peak F/Fo (n = 4) is plotted as means ± SE. Comparisons relative to control (Ad5-LacZ) were made by Student's t test. (D) Primary human ASM cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs before treatment with 100 nM salmeterol plus 1 μM dexamethasone (Salm + Dex) for 6 h. Western blotting for RSG2 and GAPDH was performed. Blots representative of five experiments are shown. (E) Alternatively, cells were loaded with Fluo4 before a 10-μM histamine challenge. Representative traces of F/Fo from nine such experiments are shown (Fig. S4G).

Gene silencing by two targeting, but not control, siRNAs robustly reduced salmeterol plus dexamethasone-induced RGS2 expression (Fig. 3D). Following a 6-h incubation with salmeterol plus dexamethasone, repression of histamine-increased [Ca2+]i was evident in naive and control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3E and Fig. S4G). However, the two RGS2-targeting siRNAs prevented this, and equivalent effects were shown for methacholine and U46619 (Fig. 3E and Fig. S4G). Conversely, 2 h of salmeterol plus dexamethasone repressed agonist-increased [Ca2+]i, but this was unaffected by RGS2-targeting siRNAs (Fig. S4G). Because RGS2 is strongly expressed at both times (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3), we propose that RGS2 is an essential and primary effector of repression at 6 h, but that non-RGS2 repressive mechanisms exist with shorter treatments.

RGS2 Is Bronchoprotective.

Given a causal relationship between elevated [Ca2+]i and ASM contraction (6, 7), the above data imply that RGS2 prevents ASM contraction. This was tested in an experimental model using Rgs2-deficient (Rgs2−/−) C57/Bl6 mice (Fig. S5A) (21). Following PCR genotyping (Fig. S5 A and B), tracheas were removed for analysis of isometric force generated by the trachealis muscle (Fig. 4A). Methacholine concentration dependently increased tension in wild-type animals with a peak of 294 ± 22% compared with the effect of 100 mM KCl. With trachealis from Rgs2−/− littermates, methacholine achieved greater peak tensions (523 ± 104%) (Fig. 4A). Rgs2 protein was expressed in wild type, but not in Rgs2−/− tracheas (Fig. 4A, Lower).

Fig. 4.

Rgs2 is bronchoprotective. (A) Equilibrated strips of mouse trachealis smooth muscle from wild type (WT) or Rgs2−/− knockout (KO) animals were challenged with KCl (100 mM). At peak contraction, muscle strips were washed free of KCl and re-equilibrated. Cumulative concentration-response curves (n = 11–15) were constructed to methacholine (MCh) and plotted as a percentage of the KCl-induced response as means ± SE. Trachealis muscles were subsequently Western blotted for Rgs2 and Gapdh. Data from three animal pairings are shown. Comparisons were made using a Mann–Whitney U test. Significance relative to the relevant wild-type control sample is *P < 0.05. (B) Wild type (WT), Rgs2−/+ heterozygous (Het), and Rgs2−/− knockout (KO) mice were subjected to lung function analysis. Total lung resistance (Upper panels) and compliance (Lower panels) was measured at baseline (Left panels), following inhalation of nebulized PBS and PBS containing increasing concentrations of methacholine (Center panels) or 5-HT (Right panels). Data (n = 6–16) are plotted as cm H2O/s/mL (resistance) or ml/cm H2O (compliance) as means ± SE. (C) Wild type (WT) (Left panels) and Rgs2 knockout (KO) (Right panels) animals were treated by i.t. instillation with 50 μL of 0.9% saline or 0.5 mg/kg formoterol (Form). After 2 h, mice were anesthetized before lung function analysis. Total lung resistance (Upper panels) and compliance (Lower panels) were measured in response to increasing concentrations of nebulized methacholine. Data (n = 4–6) are plotted as cm H2O/s/mL or ml/cm H2O as means ± SE. Lungs (n = 4) were subsequently Western blotted for Rgs2 and Gapdh.

Lung function of wild-type, Rgs2+/−, and Rgs2−/− animals was compared using the SciReq Flexivent system (22). Lung resistance and compliance were measured at baseline, following inhalation of nebulized PBS, methacholine, or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) (Fig. 4B). No differences in baseline resistance, or following PBS inhalation, were detected between wild-type, heterozygote, or knockout animals. Increasing methacholine doses modestly increased resistance in wild-type animals, and this was significantly enhanced in Rgs2−/− animals (Fig. 4B). Heterozygotes revealed an intermediate phenotype. Similar data were obtained for 5-HT except that knockout animals showed elevated resistance at all 5-HT doses (Fig. 4B). Lung compliance (inverse of stiffness) was significantly lower in knockout and heterozygote animals compared with wild-type counterparts (Fig. 4B). In response to inhaled methacholine or 5-HT, all animals showed reduced compliance. Knockout animals exhibited the lowest compliance, and heterozygotes were an intermediate phenotype. Graded expression of Rgs2 was confirmed (Fig. S5C). Because pathology may affect lung function, lungs were removed for histological examination by hematoxylin and eosin staining (for inflammation), periodic acid Schiff staining (for mucus), and differential cell counting in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. No differences were detected between wild-type, Rgs2+/−, and Rgs2−/− mice (Fig. S6).

In cultured mouse tracheal cells (MTCs) expressing the smooth muscle markers α-smooth muscle actin and calponin (Fig. S7A), salmeterol plus dexamethasone induced Rgs2 expression and reduced methacholine-, U46619-, and 5-HT–induced increases in [Ca2+]i (Fig. S7 B and C). Conversely, in Rgs2−/− MTCs, there was no Rgs2 and no protection by salmeterol plus dexamethasone against agonist-increased [Ca2+]i (Fig. S7 B and C). Although this establishes a functional role for Rgs2 in MTCs, regulation of mouse Rgs2 differed from human ASM cells. Whereas salmeterol induced Rgs2 protein with similar kinetics to human ASM and via the β2-adrenoceptor (Fig. S7 D and E), there was no dexamethasone enhancement in MTCs. Therefore, LABA alone was used in vivo to induce Rgs2 expression.

Two hours following intratracheal (i.t.) administration of aerosolized formoterol, there was a dose-dependent protection against methacholine-induced resistance and loss of compliance that correlated with Rgs2 expression (Fig. S8). Wild-type and Rgs2−/− animals were therefore treated with i.t. formoterol for 2 h before lung function analysis. Methacholine increased lung resistance and reduced compliance in wild-type animals, and formoterol significantly protected against these effects (Fig. 4C). In Rgs2−/− animals, the changes in lung function induced by methacholine were unaffected by formoterol. Basal and formoterol-induced Rgs2 expression was confirmed in the lungs of wild-type, but not of Rgs2−/−, animals (Fig. 4C). Thus, elevated RGS2 protects against methacholine-induced increases in lung resistance and loss of compliance.

Discussion

We describe the induction of RGS2 expression as a previously unrecognized genomic mechanism of bronchoprotection that is induced by LABAs and that is synergistically enhanced by glucocorticoids in human ASM cells. We propose that this represents an important means by which ICS/LABA therapies effect superior control of symptoms in diseases such as asthma or COPD. Thus, international guidelines for the management of asthma and COPD indicate stepwise increases in the intensity of pharmacotherapy moving from inhaled monotherapies to inhaled ICS/LABA combinations (1, 2). For example, mild-to-moderate asthmatics are generally prescribed regular ICS whereas more severe disease requires ICS/LABA combinations, which enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of the ICS to a level that cannot be achieved by ICS alone (23). Conversely, in COPD, LABAs represent an initial maintenance medication, which, in more advanced disease, is increased to ICS/LABA combinations. Equally, bronchiolitis is a major cause of hospitalization in infants of less than 1 y and is poorly controlled by conventional monotherapies (24). However, inhaled epinephrine, which will activate β2-adrenoceptors on ASM, combined with dexamethasone (epinephrine and dexamethasone were ineffective alone), significantly reduced hospitalization rates in these infants (25). Thus, multiple strands of clinical evidence support a positive, synergistic interaction between the agonist of the β2-adrenoceptor and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Our current study offers some explanation for this effect (23).

Mechanistically, β2-adrenoceptor agonists can synergistically enhance glucocorticoid actions, and this may contribute to the enhanced efficacy of ICS/LABA combinations (12, 23). However, we show RGS2 to be a PKA-dependent effector gene, whose expression in human ASM promotes bronchoprotection and is synergistically enhanced by glucocorticoids. Functionally, RGS2 is a GAP that switches off signaling from Gq-coupled GPCRs (10, 26), including muscarinic M1 and M3 receptors (27, 28), and we confirm this for multiple other receptors that are relevant to lung disease. Importantly, combinations of LABA plus glucocorticoid enhance and extend RGS2 expression in human ASM, and loss of RGS2 expression prevents the prolonged protective effect of the combination against agonist-enhanced [Ca2+]i. In vivo, loss of RGS2 produces a hyperactive phenotype with increased lung resistance and reduced compliance. This is consistent with the hypertensive effect of RGS2 loss in the vasculature and confirms a bronchoprotective role in the lung (29, 30). Furthermore, the ability to induce RGS2 expression in vivo further protects against spasmogen-increased lung resistance and reductions in compliance. Thus, the extended induction of RSG2 in ASM by ICS/LABA combination therapies should provide superior protection from multiple spasmogens that act on Gq-coupled GPCRs in asthma, COPD, or bronchiolitis and other diseases.

Induction of RGS2 expression by β2-adrenoceptor agonists and forskolin implies a classical cAMP pathway leading rapidly to RGS2 gene expression and is consistent with isoproterenol inducing RGS2 mRNA in rat astrocytoma cells (31). Roles for the β2-adrenoceptor and PKA were confirmed by preventing RGS2 expression in the presence of ICI 118,551 or PKIα and is supported for forskolin, which induces CREB binding to CRE sites in the proximal RGS2 promoter (32). Likewise, the ability of glucocorticoids to synergistically enhance RGS2 expression could simplistically involve enhanced β2-adrenoceptor expression, coupling, or reduced receptor desensitization (see ref. 8 and references therein). However, these effects are not likely to occur acutely and in any event may not be important in ASM due to the large β2-adrenoceptor reserve (33). More likely, as RGS2 is a glucocorticoid-responsive gene (15, 34) with an established GR-binding region (35), there is a direct interaction of the cAMP and glucocorticoid pathways at the level of promoter activation. Certainly, our data support a mechanism that involves transcriptional induction of RGS2 because the level of unspliced nuclear RGS2 RNA was both enhanced and prolonged in the presence of LABA plus glucocorticoid. Because there was no obvious effect on RGS2 mRNA stability, and because protein expression correlates well with mRNA expression, these data support transcriptional control as the major effector mechanism governing RGS2 expression in human ASM cells. Furthermore, the use of three structurally distinct GR ligands with differing selectivities for other nuclear hormone receptors, including the progesterone, mineralocorticoid, androgen, and estrogen receptors (4), excludes their involvement and supports a role for GR. This interaction between the glucocorticoid and cAMP pathways requires formal investigation and should be tested alongside other physiological agents, such as parathyroid hormone or angiotensin II, which also induce RSG2 expression (36, 37).

Importantly, knockdown of RGS2 expression in human ASM cells did not prevent attenuation of spasmogen-enhanced [Ca2+]i following 2 h of salmeterol plus dexamethasone. Given the presence of RGS2 protein, classical mechanisms of bronchoprotection must operate to create functional redundancy. However, the protective effect of 6 h of salmeterol plus dexamethasone on human ASM was totally prevented by RGS2 knockdown. This indicates that elevated RGS2 gene expression is the dominant protective mechanism and clearly illustrates how ICS/LABA combinations may confer enhanced therapeutic benefit. Indeed, the 12-h protection from spasmogen-induced [Ca2+]i afforded by salmeterol plus dexamethasone, compared with just 4 h for salmeterol alone, further demonstrates the potential advantage due to RGS2. In this context, it is salient to note that the effects due to RGS2 occur on a background of other RGS proteins, including RGS3, -4, and -5, which are all relatively highly expressed in human ASM cells (38). Indeed, somewhat paradoxically, β-agonists reduce RGS5 expression, and this may be expected to reduce some of the benefit conferred by elevation of RGS2 (38).

These data also highlight important differences between mice and humans. First, human RSG2 is synergistically induced by LABAs and glucocorticoids, whereas mouse Rgs2 is induced only by LABAs. Thus, the mouse models Rgs2 function, but not gene regulation. Second, mouse Rgs2 function is nonredundant when induced by LABA alone. In this regard, there is persuasive evidence suggesting that the classical bronchodilatory effects of β-adrenoceptor agonists are mediated via the β1, rather than the β2, subtype in the mouse (39). Thus, β2-adrenoceptor agonists are poor bronchodilators in the mouse, and this explains why nonselective agonists are more effective and potent bronchodilators than β2-selective agonists (40). Nevertheless, our data clearly show that β2-adrenoceptor agonists induce the expression of Rgs2 and that this leads to a significant nonredundant bronchoprotective effect that is absent in Rgs2−/− animals.

In summary, the induction of RGS2 gene expression provides bronchoprotection, which, in the context of β2-adrenoceptor monotherapy, is likely to be largely redundant because of acute, nongenomic mechanisms of relaxation/bronchoprotection. However, in the clinical context of ICS/LABA combination therapies, RGS2 expression may be enhanced and prolonged. Under this condition, the genomic induction of RGS2 becomes the predominant effector for protecting against bronchoconstrictor mediators. This represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of how sympathomimetic bronchodilators improve symptom control in diseases such as asthma, COPD, or acute bronchiolitis. In terms of drug discovery, drugs, or drug combinations, that enhance and/or prolong RGS2 expression are, like ICS/LABA combinations, predicted to result in superior bronchoprotection from clinically relevant spasmogens.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified. C57/Bl6 wild-type, Rgs2 heterozygous (Rgs2+/−), and knockout (Rgs2−/−) mice were bred in-house through Rgs2+/− × Rgs2+/− crosses (21, 30). Protocols were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committee, according to the Canadian Council for Animal Care guidelines. Mice were age and sex matched between different genotype groups. Where appropriate, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane before i.t administration of aerosolized 0.9% NaCl or formoterol using a MicroSprayer aerosolizer (Penn-Century) (41). Isolated ASM cells from normal human lungs were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen) and incubated in serum-free medium before experiments (12).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR.

RNA extractions and real-time PCR (SYBR GreenER chemistry) for GAPDH was as described (15). Amplification primers were RGS2 forward (5′-CCT CAA AAG CAA GGA AAA TAT ATA CTG A-3′) and reverse (5′-AGT TGT AAA GCA GCC ACT TGT AGC T-3′). TaqMan analysis of unspliced nuclear RGS2 is described in SI Materials and Methods.

Western Blotting, siRNA Knockdown, and Adenoviral Infections.

Western blotting, siRNA transfections, and adenoviral infections were as described (42). siRNA-targeted sequences were RGS2 siRNA 2 (SI00045773; 5′-AAC GTG GTG TCT CAC TCT GAA-3′); RGS2 siRNA 6 (SI03036082; 5′-AAG GGT ATA CAG CTT GAT GGA-3′) (Qiagen); and green fluorescent protein siRNA (control siRNA) (P-002048–03-20; 5′-GGC AAG CTG ACC CTG AAG TTC-3′) (Dharmacon). Cells were infected with 300 MOI of Ad5-RGS2.HA (43) or Ad5-LacZ for 24 h before experiments.

Calcium Assay.

[Ca2+]i release was measured using Fluo4 NW according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Confluent cells were loaded for 30 min at room temperature with Fluo-4. Using 494 nm excitation, basal fluorescence (F0) was measured at 516 nm for 1.6 s (FLUOstar OPTIMA plate reader, BMG Labtech). Agonists were injected and fluorescence (F) was measured. Values expressed as F/F0 are a proxy for [Ca2+]i.

Lung Function.

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) (CEVA Santé Animale) and intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (90 mg/kg) (Wyeth). Tracheostomized mice were connected to a flexivent small animal ventilator (SciReq) before challenge with increasing concentrations of aerosolized drugs administered via an in-line nebulizer. Resistance and compliance were measured using a snapshot 150 perturbation (22).

Isometric Force Measurement.

Mice were euthanized with 200 mg/kg pentobarbital and exsanguination. Excised tracheas were divided into four equal pieces before placing in oxygenated Krebs–Henseleit solution (KHS) (33). Strips were mounted vertically under a tension of 6 mN in oxygenated KHS at 37 °C. After equilibration with frequent washing for at least 120 min before experiments, changes in tension were measured isometrically (33).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the GlaxoSmithKline Collaborative Innovative Research Fund, GlaxoSmithKline Canada (to R.N., M.A.G., and R.L.); by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to R.N.); by studentship support from GlaxoSmithKline, United Kingdom (to R.N. and M.A.G.), studentship awards from the Lung Association of Alberta and North West Territories (to C.F.R.) and from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (to C.F.R.); and an Izaak Walton Killam Post-Doctoral Fellowship (to N.S.H.). R.N. and R.L. are Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions Senior Scholars and Clinical Investigators, respectively. A grant from the Canadian Fund for Innovation and the Alberta Science and Research Authority provided equipment and infrastructure for conducting real-time PCR.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1110226108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bateman ED, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–178. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabe KF, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrewsbury S, Pyke S, Britton M. Meta-analysis of increased dose of inhaled steroid or addition of salmeterol in symptomatic asthma (MIASMA) BMJ. 2000;320:1368–1373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newton R, Leigh R, Giembycz MA. Pharmacological strategies for improving the efficacy and therapeutic ratio of glucocorticoids in inflammatory lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:286–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PJ. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:183–192. doi: 10.1038/nri2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gosens R, Zaagsma J, Meurs H, Halayko AJ. Muscarinic receptor signaling in the pathophysiology of asthma and COPD. Respir Res. 2006;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahn K, et al. Ca(2+) homeostasis and structural and functional remodelling of airway smooth muscle in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:547–552. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giembycz MA, Newton R. Beyond the dogma: Novel beta2-adrenoceptor signalling in the airways. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:1286–1306. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00112605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siderovski DP, Willard FS. The GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs of heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunits. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1:51–66. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heximer SP. RGS2-mediated regulation of Gqalpha. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:65–82. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimple AJ, et al. Structural determinants of G-protein alpha subunit selectivity by regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19402–19411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaur M, Chivers JE, Giembycz MA, Newton R. Long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists synergistically enhance glucocorticoid-dependent transcription in human airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:203–214. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Audibert A, Weil D, Dautry F. In vivo kinetics of mRNA splicing and transport in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6706–6718. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6706-6718.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipson KE, Baserga R. Transcriptional activity of the human thymidine kinase gene determined by a method using the polymerase chain reaction and an intron-specific probe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9774–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chivers JE, et al. Analysis of the dissociated steroid RU24858 does not exclude a role for inducible genes in the anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:2084–2095. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meja KK, et al. Adenovirus-mediated delivery and expression of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor gene to BEAS-2B epithelial cells abolishes the anti-inflammatory effects of rolipram, salbutamol, and prostaglandin E2: A comparison with H-89. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:833–844. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke DL, Belvisi MG, Hardaker E, Newton R, Giembycz MA. E-ring 8-isoprostanes are agonists at EP2- and EP4-prostanoid receptors on human airway smooth muscle cells and regulate the release of colony-stimulating factors by activating cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:383–393. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur M, et al. Effect of beta2-adrenoceptor agonists and other cAMP-elevating agents on inflammatory gene expression in human ASM cells: A role for protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L505–L514. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00046.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander APH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th Ed. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. J Biochem. 1997;122:498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira-Dos-Santos AJ, et al. Regulation of T cell activation, anxiety, and male aggression by RGS2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12272–12277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220414397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shalaby KH, Gold LG, Schuessler TF, Martin JG, Robichaud A. Combined forced oscillation and forced expiration measurements in mice for the assessment of airway hyperresponsiveness. Respir Res. 2010;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giembycz MA, Kaur M, Leigh R, Newton R. A Holy Grail of asthma management: Toward understanding how long-acting beta(2)-adrenoceptor agonists enhance the clinical efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1090–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wainwright C. Acute viral bronchiolitis in children: A very common condition with few therapeutic options. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2010;11:39–45, quiz 45. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plint AC, et al. Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Epinephrine and dexamethasone in children with bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2079–2089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hains MD, Siderovski DP, Harden TK. Application of RGS box proteins to evaluate G-protein selectivity in receptor-promoted signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:71–88. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein LS, et al. RGS2 binds directly and selectively to the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor third intracellular loop to modulate Gq/11alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21248–21256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tovey SC, Willars GB. Single-cell imaging of intracellular Ca2+ and phospholipase C activity reveals that RGS 2, 3, and 4 differentially regulate signaling via the Galphaq/11-linked muscarinic M3 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1453–1464. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.005827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang KM, et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling-2 mediates vascular smooth muscle relaxation and blood pressure. Nat Med. 2003;9:1506–1512. doi: 10.1038/nm958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heximer SP, et al. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:445–452. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SD, et al. Mechanism of isoproterenol-induced RGS2 up-regulation in astrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y, et al. CHARGE Consortium. GIANT Consortium CRTC3 links catecholamine signalling to energy balance. Nature. 2010;468:933–939. doi: 10.1038/nature09564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giembycz MA. An estimation of beta 2-adrenoceptor reserve on human bronchial smooth muscle for some sympathomimetic bronchodilators. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JC, et al. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) scanning identifies primary glucocorticoid receptor target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15603–15608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407008101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.So AY, Cooper SB, Feldman BJ, Manuchehri M, Yamamoto KR. Conservation analysis predicts in vivo occupancy of glucocorticoid receptor-binding sequences at glucocorticoid-induced genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5745–5749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801551105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant SL, et al. Specific regulation of RGS2 messenger RNA by angiotensin II in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:460–467. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsingotjidou A, Nervina JM, Pham L, Bezouglaia O, Tetradis S. Parathyroid hormone induces RGS-2 expression by a cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-mediated pathway in primary neonatal murine osteoblasts. Bone. 2002;30:677–684. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, et al. Beta-agonist-associated reduction in RGS5 expression promotes airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11444–11455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.212480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry PJ, Goldie RG. Beta 1-adrenoceptors mediate smooth muscle relaxation in mouse isolated trachea. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:131–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomkinson A, Karlsson JA, Raeburn D. Comparison of the effects of selective inhibitors of phosphodiesterase types III and IV in airway smooth muscle with differing beta-adrenoceptor subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bivas-Benita M, Zwier R, Junginger HE, Borchard G. Non-invasive pulmonary aerosol delivery in mice by the endotracheal route. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;61:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King EM, Holden NS, Gong W, Rider CF, Newton R. Inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription by MKP-1: Transcriptional repression by glucocorticoids occurring via p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26803–26815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salim S, Sinnarajah S, Kehrl JH, Dessauer CW. Identification of RGS2 and type V adenylyl cyclase interaction sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15842–15849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.