Abstract

Synaptic transmission relies on effective and accurate compensatory endocytosis. F-BAR proteins may serve as membrane curvature sensors and/or inducers and thereby support membrane remodelling processes; yet, their in vivo functions urgently await disclosure. We demonstrate that the F-BAR protein syndapin I is crucial for proper brain function. Syndapin I knockout (KO) mice suffer from seizures, a phenotype consistent with excessive hippocampal network activity. Loss of syndapin I causes defects in presynaptic membrane trafficking processes, which are especially evident under high-capacity retrieval conditions, accumulation of endocytic intermediates, loss of synaptic vesicle (SV) size control, impaired activity-dependent SV retrieval and defective synaptic activity. Detailed molecular analyses demonstrate that syndapin I plays an important role in the recruitment of all dynamin isoforms, central players in vesicle fission reactions, to the membrane. Consistently, syndapin I KO mice share phenotypes with dynamin I KO mice, whereas their seizure phenotype is very reminiscent of fitful mice expressing a mutant dynamin. Thus, syndapin I acts as pivotal membrane anchoring factor for dynamins during regeneration of SVs.

Keywords: membrane recruitment of dynamins, rod photoreceptor ribbon synapses, seizures with tonic–clonic convulsions, SV formation and recycling, F-BAR protein syndapin/PACSIN

Introduction

Brain development, synaptic transmission as well as neuronal plasticity require considerable membrane remodelling. Communication between nerve cells is brought about by synaptic vesicle (SV) exocytosis, endocytosis and recycling pathways. Despite ongoing membrane dynamics, however, synaptic compartmentalization is kept intact and the SV pool as well as SV size is sustained at both high and low firing rates. A tight balance of exocytic and endocytic pathways needs to be maintained during a huge variety of synaptic transmission modes to ensure proper brain function. Different modes of endocytosis have been suggested to operate in synapses (Südhof, 2004; Ryan, 2006; Voglmaier and Edwards, 2007). All seem to require a member of the dynamin family of large GTPases, resulting in the formation of SVs with uniform appearance (Fox, 1988; Harris and Sultan, 1995; Schikorski and Stevens, 1997). Additionally, several dynamin-binding proteins, so-called accessory proteins, seem to be involved in endocytic processes. Among these accessory proteins are Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain superfamily proteins. The BAR domain superfamily contains several subfamilies, among those the F-BAR subfamily (for recent reviews, see Frost et al, 2009 and Qualmann et al, 2011). Structural analyses of several F-BAR domain-containing proteins (Henne et al, 2007; Shimada et al, 2007; Wang et al, 2009) show antiparallel dimeric complexes, which are crescent shaped with a shallow curvature when viewed from side, and some appear S-shaped from above. It was suggested that these structures are capable of bending membranes or sensing membrane curvatures (Shimada et al, 2007; Frost et al, 2008). Prominent F-BAR domain proteins are syndapins, a family of genes, which—as single copies—already occur in worms and insects (Kessels and Qualmann, 2004). Syndapins are membrane-associating factors (Itoh et al, 2005; Dharmalingam et al, 2009) working in close collaboration with the actin cytoskeleton and vesicle scission machineries, which they can even physically connect via oligomerization (Kessels and Qualmann, 2006). Syndapins control the activity of the Arp2/3 complex (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000; Kessels and Qualmann, 2002; Dharmalingam et al, 2009), syndapins are critical for the membrane recruitment of the actin nucleator Cobl (Schwintzer et al, 2011) and, based on their identification as synaptic, dynamin-associated proteins (Qualmann et al, 1999) and the phosphorylation dependence of the interaction of syndapin I with dynamin I, syndapin I was suggested to be the dynamin I-phosphosensor and to play a pivotal role in SV recycling in neurons (Anggono et al, 2006). Consistently, disruption of syndapin/dynamin complexes interfered with dynamin-mediated vesicle formation from the plasma membrane (Simpson et al, 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000; da Costa et al, 2003; Braun et al, 2005; Andersson et al, 2008; Clayton et al, 2009) and from the Golgi, respectively (Kessels et al, 2006; Salvarezza et al, 2009).

Neurons rely on very efficient vesicle recycling processes, dynamin I-mediated vesicle fission reactions (Ferguson et al, 2007) and regulation of dynamin complexes by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation cycles (Clayton et al, 2009). We, therefore, generated mice deficient for the brain-enriched isoform of the syndapin family, syndapin I, to evaluate the physiological importance of syndapin I in a mammalian animal model. Our studies reveal that syndapin I is crucial for proper brain function. Syndapin I is critical for the association of dynamins with membranes. Further phenotypical analyses of syndapin I knockout (KO) mice highlight the functional importance of syndapin I for proper SV formation in hippocampal and retinal synapses, for proper hippocampal network activity and for proper function of the mammalian brain as such.

Results

Generation of syndapin I KO mice

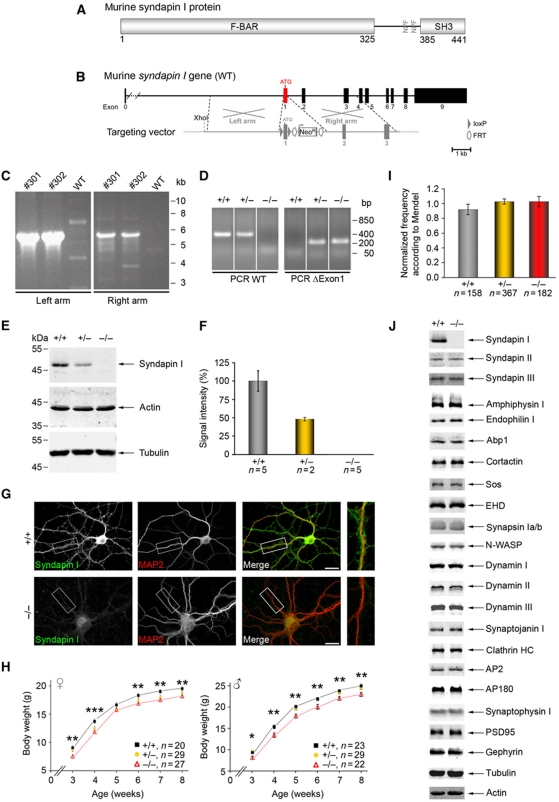

Dynamin-binding F-BAR proteins were suggested to induce and/or sense membrane curvature during vesicle formation; yet, their in vivo functions in membrane topology control and the physiological importance of such processes as well as their role in dynamin function largely remained to be demonstrated by genetic loss-of-function analyses. We, therefore, generated mice lacking the brain-enriched F-BAR domain protein syndapin I (Figure 1A) by removal of exon1 of the murine syndapin I gene (Figure 1A and B). Homologous recombination of the targeting vector (Figure 1B) was verified by long-range PCR (Figure 1C) and Southern blotting (data not shown). Syndapin I KO mice were generated by mating with ubiquitously expressing Cre mice (Figure 1D). Biochemical and immunocytochemichal analyses confirmed the complete loss of syndapin I (Figure 1E–G).

Figure 1.

Generation of syndapin I KO mice. (A) Murine syndapin I harbours an N-terminal F-BAR domain, a C-terminal SH3 domain and two NPF-motifs (aa 364–366 and 376–378). (B) The syndapin I gene is composed of 10 exons with exon1 containing the ATG. In grey, schematic organization of the targeting vector. Homologous recombination of left and right arms of the targeting vector with the murine syndapin I gene led to floxed exon1. (C) ES cell clones #301 and #302 with correct recombination events identified by long-range PCRs. (D) PCRs to genotype siblings of heterozygous matings identify all possible genotypes (the order of samples was modified, as indicated by addition of white lines). (E, F) Syndapin I immunodetection in brain homogenates (50 μg each) revealed complete loss in homozygous syndapin I KO mice and a 50% reduction in heterozygous littermates. Actin and tubulin served as loading control. Data represent mean±s.e.m. (G) The remaining anti-syndapin I immunosignal in primary hippocampal cultures (DIV21) from syndapin I KO mice was comparable to that of secondary antibody controls (data not shown) demonstrating absence of syndapin I. Scale bar, 20 μm. (H) Developmental body weight analysis of female and male mice revealed significant ∼10% reductions in homozygous syndapin I KO mice. Two-tailed Student's t-test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (I) Frequency of genotypes normalized to expected values from Mendelian distribution show no deviations. (J) Quantitative western blot analyses of brain homogenates (50 μg each, n=5 animals for +/+ and −/−) display no alterations in the expression levels of various proteins (for quantitative data, see Supplementary Figure S1). Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

Homozygous syndapin I KO mice were viable and survived for at least >1 year but their fertility was reduced by ∼30% (data not shown). Furthermore, the body weights of both genders of syndapin I KO mice were significantly reduced in comparison with wild-type (WT) mice (∼10%; Figure 1H).

Syndapin I KO, however, did not cause any embryonic lethality. Birth frequencies were according to Mendel (Figure 1I).

A comprehensive quantitative analysis of proteins with similar domain organization, function and/or of interaction partners, of proteins involved in membrane trafficking and of proteins implicated in subcellular organization of excitatory and inhibitory synapses showed no change in expression levels in syndapin I KO mice. Interestingly, also syndapins II and III neither compensated for nor were affected in stability (Figure 1J; Supplementary Figure S1). The phenotypes of syndapin I KO mice thus indeed seem specifically attributable to the lack of syndapin I.

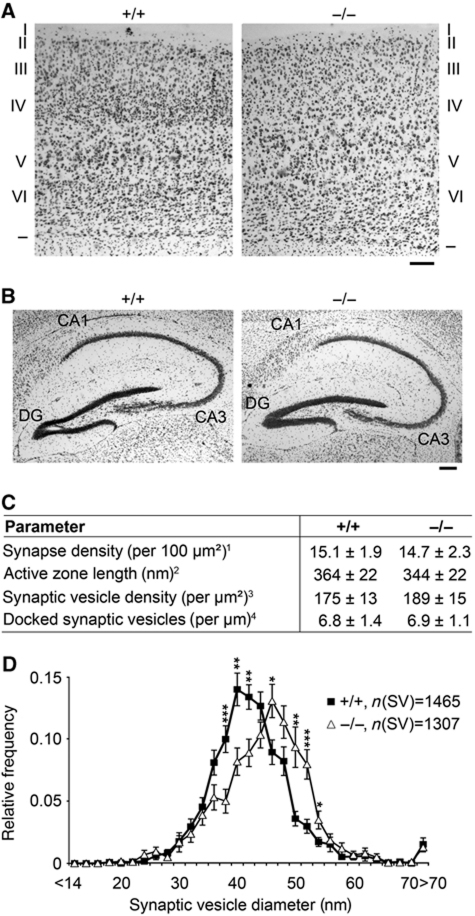

Syndapin I is important for accurate SV morphology control

Brain weight (data not shown), brain volume (compare Supplementary Figure S2) and histology showed no gross impairments of brain development. Cortical thickness and layering was normal (Figure 2A), so was the overall hippocampal architecture (Figure 2B), although the hippocampal volume was slightly increased (Supplementary Figure S2). Despite the fact that syndapin I can promote Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin nucleation, also F/G-actin ratios in different areas of the hippocampus were unchanged in syndapin I KO mice (Supplementary Figure S3A and B). Biochemical determinations of F/G-actin ratios in resting synaptosomes did not reveal any phenotype either (Supplementary Figure 3C and D).

Figure 2.

Significantly increased SV diameters in hippocampal syndapin I KO synapses. (A, B) Histological analyses of cortices (A) and hippocampi (B) of adult WT and syndapin I KO mice via Nissl staining showed no gross defects in brain development and architecture. Borders and the six layers (I–VI) of the cortex are marked (A). DG, dentate gyrus. Bars, 200 μm. (C) Detailed morphometric analyses of synaptic terminals. 1Determined as postsynaptic density (PSD) number from randomly selected electron micrographs (total area of 49.1 μm2 each, n=211 (+/+) and n=259 (−/−)), 2determined as extension of the PSD, 3determined as SV number inside a semicircle around the active zone and 4SVs located ⩽50 nm from the plasma membrane. Parameters 2–4 and SV size distribution (D) were determined from high-magnification micrographs (n=40 (+/+) and n=41 (−/−); 4 animals/genotype). (D) SV size distribution in WT and syndapin I KO animals. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

We next examined the ultrastructure of hippocampal presynapses by quantitative electron microscopical (EM) analyses (Figure 2C and D). No defects in synaptogenesis were detected, both synapse density and overall synapse morphology were normal (Figure 2C). Also, the SV density and the number of docked SVs were unchanged. The diameters of SVs of syndapin I KO synapses, however, were significantly increased and vesicle surfaces were thus less curved compared with WT (Figure 2D).

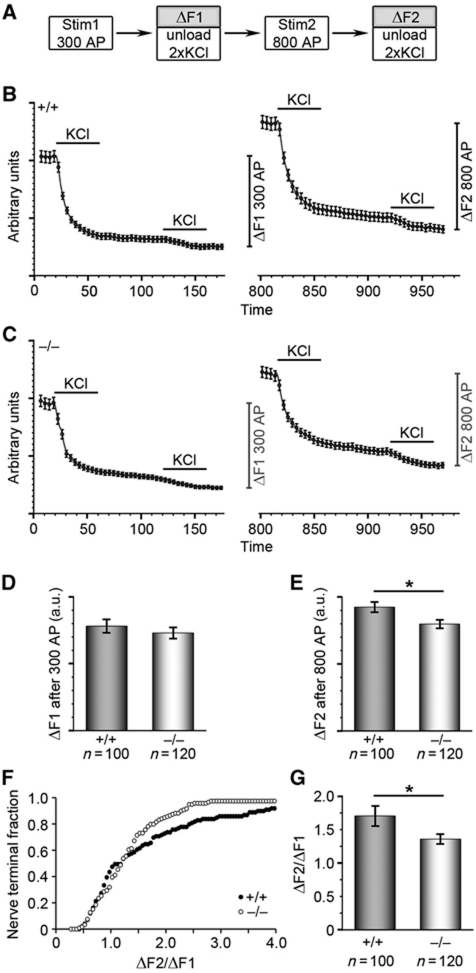

Syndapin I KO impairs SV endocytosis

Since also the KO phenotypes of the syndapin I binding partner dynamin I predominantly manifested upon stronger stimulation (Ferguson et al, 2007), we next tested FM1-43 recycling in nerve terminals of cultured hippocampal neurons after moderate and strong stimulation (Figure 3A–E). Small differences in the performance of syndapin I KO neurons in comparison with WT neurons were observed upon 300 action potentials at 10 Hz (ΔF1; Figure 3B–D). In contrast, dye turnover was significantly reduced upon the following much stronger stimulation (ΔF2; Figure 3B, C and E). Also, the ΔF2/ΔF1 ratio of individual nerve terminals determined according to Clayton and Cousin (2008) showed a significant reduction in syndapin I KO neurons (WT, 1.71±0.15 versus KO, 1.36±0.07; P=0.028; t-test) (Figure 3F and G). Thus, syndapin I deficiency particularly disturbs high-capacity retrieval of SVs.

Figure 3.

Selective activity-dependent requirement for syndapin I during synaptic vesicle recycling in hippocampal cultures. (A) Hippocampal cultures were loaded and unloaded with FM1-43 dye using the protocol displayed. (B, C) Time course of the average response of WT (B) and syndapin I KO (C) nerve terminals loaded with FM1-43 is displayed. KCl evoked unloading is shown by bar. The amount of dye unloaded after Stim1 (300 stimuli) and Stim2 (800 stimuli) yields ΔF1 and ΔF2. (D, E) Quantification of mean dye release after 300 stimuli (ΔF1, D) and after 800 stimuli (ΔF2, E) revealed a trend to reduced dye uptake after 300 stimuli (D) and significantly decreased dye uptake after 800 stimuli (E) in syndapin I KO hippocampal neurons, suggesting defective activity-dependent SV endocytosis in the absence of syndapin I. (F, G) Reduced SV turnover in individual nerve terminals shown by cumulative histogram of the ΔF2/ΔF1 ratios of individual synapses (F) and the averaged ΔF2/ΔF1 response (G) suggesting defective activity-dependent SV endocytosis in the absence of syndapin I. *P<0.05; t-test.

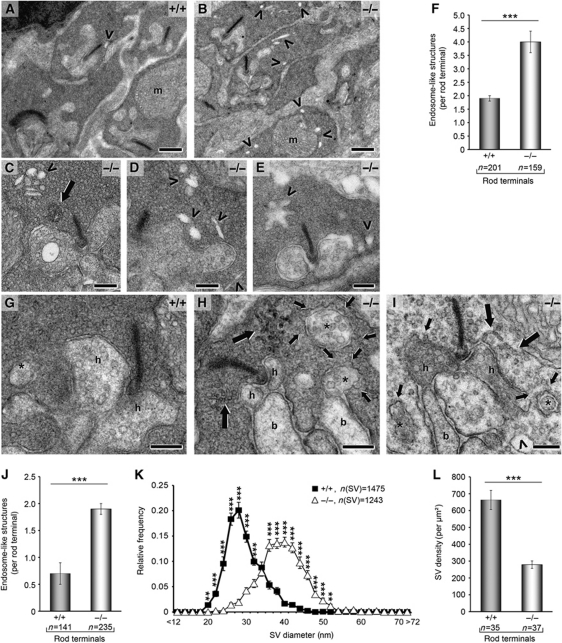

Severe SV formation defects in synapses of the retina upon syndapin I deficiency

To study a physiological system marked by high-capacity retrieval, we analysed the ultrastructure of retinae. The retina shows tremendous synaptic transmission in the dark. As transmission is effectively repressed by exposure to light, massive compensatory retrieval without overlaying vesicle exocytosis can be studied in retinae adapted to darkness and then acutely exposed to light (Figure 4A–F) or subjected to prolonged retrieval in the light, respectively (Figure 4G–L). Syndapin I is widely expressed in the retina (Houdart et al, 2005; Supplementary Figure S4), with significant proportions localizing to rod photoreceptor terminals representing the outer plexiform layer marked by the presynaptic marker and ribbon component RIBEYE (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 4.

Drastic alterations in rod photoreceptor ribbon synapses of syndapin I KO animals after light exposure. (A–F) Rod ribbon synapses after acute exposure to light from WT (A) and syndapin I KO (B–E) mice. Note the high number of endosome-like structures (arrowheads) and the occurrence of tubular structures (C, large arrow), respectively, in syndapin I KO synapses. m, mitochondrion. (F) Endosome-like structures were increased by 110% in syndapin I KO mice (n=4 animals/genotype). (G–L) Syndapin I KO synapses (H, I) differ from WT (G) after long exposure to light and showed massive membrane trafficking defects with numerous coated omega-shaped profiles at the presynaptic plasma membrane (H, I, small arrows). In addition, branched tubular structures (H, I, large arrows) and endosome-like structures (I, arrowhead) were visible in syndapin I KO synapses. h, Horizontal cell processes; b, bipolar cell dendrites; *, peripheral protrusions of horizontal cells. (J) Quantification of endosome-like structures per rod terminal from 4 animals/genotype after long exposure to light revealed a 170%-increase. (K) SV sizes were shifted to larger SV diameters. (L) SV density was reduced by 58% in syndapin I KO mice. Quantitative data represent mean±s.e.m.; **P<0.01 ***P<0.001. Scale bars, 0.5 μm (A, B) and 0.2 μm (C–E, G–I).

Syndapin I KO synapses of rod photoreceptor cells adapted less dynamically to light exposure but were filled with irregular-shaped endosome-like structures (Figure 4A–J). Upon both acute (Figure 4A–F) and prolonged light exposure (Figure 4G–L), a dramatic and statistically highly significant increase of endosome-like structures was observed (Figure 4F and J). Additionally, syndapin I KO retina synapses exhibited accumulations of branched tubular structures (Figure 4C, H and I; large arrows) and a strongly increased abundance of omega-shaped profiles at the plasma membrane (Figure 4H and I; small arrows). Furthermore, Immuno-EM showed an increased frequency of clathrin labelling at the plasma membrane of syndapin I KO ribbon synapses (our unpublished results). In accordance with our observations in the hippocampus (Figure 2D), SV diameters were significantly larger (Figure 4K). Furthermore, a strong reduction in SV density was observed in syndapin I KO synapses (Figure 4L).

Together, these data suggest severe membrane trafficking defects in rod photoreceptor synapses of syndapin I KO mice and reveal that syndapin I is important for compensatory endocytosis following high activity.

Crucial requirement of syndapin I for membrane recruitment of dynamins

The increased SV diameter and reduced SV density together with accumulation of omega-shaped and tubulovesicular structures and a reduced functional SV pool in syndapin I KO synapses suggested that the recruitment of the vesicle formation machinery and/or the coordination of its activity with correct membrane curvatures were impaired.

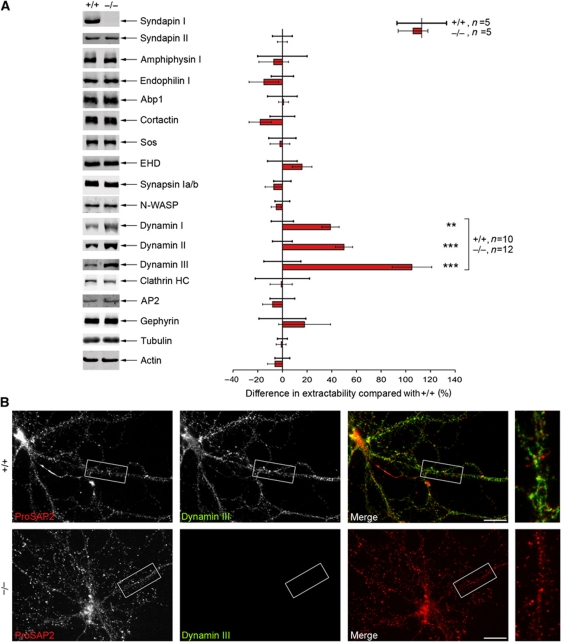

To test for any putative defects in the anchoring of the endocytic machinery, we analysed Triton X-100-soluble brain fractions. Whereas other syndapin-interacting proteins, such as EHD proteins and Sos, were unchanged, the solubility of the syndapin I interaction partner dynamin I was significantly increased in syndapin I KO mice (Figure 5A). Since dynamin I expression levels remained unchanged (Figure 1J; Supplementary Figure S1), this finding clearly indicated defective dynamin anchoring. Interestingly, an increase in extractability was also evident for the dynamin isoforms II and III. In fact, it was most striking for dynamin III (105% increase; Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Strongly increased dynamin extractability in syndapin I KO mice. (A) Equal amounts of Triton X-100-soluble fractions of either genotype subjected to quantitative western blot analyses normalized to the corresponding actin signal on the same membrane. Deviations of the mean in KO samples (set to 0) to the mean in WT samples (red column) are expressed in percent. Data represent mean±s.e.m. For dynamins, a highly statistically significant increase in Triton X-100 extractability was observed (dynamin I: 39±7%, dynamin II: 50±7%, dynamin III: 105±16%). A similar increase was observed upon normalization to tubulin. Mann–Whitney U-test; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (B) Primary hippocampal neurons (21 DIV) were subjected to Triton X-100 extraction and subsequent immunocytochemistry. Dynamin III levels were reduced to background signal in syndapin I KO cultures, whereas a reasonable signal was still present in WT cultures. Anti-ProSAP2 immunostaining served as control, this synaptic scaffold protein was not extracted. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Immunostainings for all three dynamin isoforms in primary hippocampal cultures (Supplementary Figure S5) and in the retina (data not shown) did not point to any obvious differences in the overall distribution of dynamins in syndapin I-deficient cells. However, consistent with the particular strong defects of dynamin III anchoring in the quantitative biochemical examinations (Figure 5A), we also observed in immunofluorescence analyses that the immunostaining of dynamin III was clearly reduced upon Triton X-100 treatment (Figure 5B).

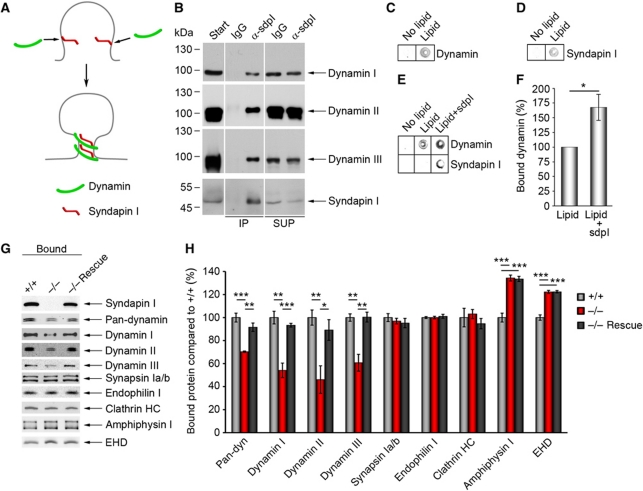

A scenario, in which syndapin I crucially assists in recruiting dynamins and/or in coordinating vesicle formation with a suitable curvature of the donor membrane (Figure 6A; Supplementary Figure S6), would mechanistically require that (i) syndapin I is able to associate with all dynamin isoforms and that (ii) membrane-bound syndapin I is able to promote membrane binding of dynamins.

Figure 6.

Syndapin I promotes lipid association of all dynamins and is of critical importance for dynamin membrane anchoring. (A) Scenario, in which syndapin I coordinates the vesicle formation machinery with membrane curvature by direct binding to curved lipid surfaces and by dynamin recruitment. (B) Specific detection of dynamins I, II and III in anti-syndapin I immunoprecipitates from brain extracts (IPs). SUP, supernatant. The order of samples on the gels was modified, as indicated by white lines. (C–F) Lipid-binding assay in 96-well plates coated with or without phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) mixture (PS:PC ratio 1:3) revealed a specific lipid binding of dynamin (C) and syndapin I (D). (E) Preincubating lipid-coated wells with syndapin I strongly increased subsequent binding of dynamin. Quantitative analyses (F) show a significant increase (167±22%) (Wilcoxon signed rank test). Data represent mean±s.e.m. N=6 experiments; *P<0.05. (G, H) Liposomes made of Folch fraction I incubated with equal amounts of WT and syndapin I KO cytosol and analysed by quantitative western blot analysis (H). Note the significant reduction of dynamin binding (30% for pan-dynamin, 40% for dynamins I and III and 50% for dynamin II), whereas synapsin Ia/b, endophilin I and clathrin heavy chain (HC) binding were unaffected. The dynamin recruitment defects in syndapin I KO cytosol were completely abolished by addition of syndapin I (−/− Rescue) (G, H). Data represent mean±s.e.m. of four independent experiments with material from 2 animals/genotype. One-way ANOVA; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

Syndapin I interactions with all three isoforms of dynamin were indeed demonstrated by immunoprecipitation of syndapin I-containing complexes from brain cytosol (Figure 6B). Syndapin I hereby interacts with all three dynamin isoforms in a direct manner, as shown by co-precipitation assays with purified proteins (Supplementary Figure S7; Qualmann et al, 1999; Kessels et al, 2006).

To directly evaluate a dynamin-recruiting function of membrane-bound syndapin I, we performed lipid-binding assays. Using an LI-COR Odyssey system, we were able to quantitatively analyse the two proteins simultaneously. In line with previous studies, both dynamin (Figure 6C) and syndapin I (Figure 6D) bound to phosphatidylserine (PS)-containing lipids when tested individually (Powell et al, 2000; Itoh et al, 2005; Dharmalingam et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2009). Strikingly, preincubation of the lipid surfaces with syndapin I enhanced subsequent dynamin binding by about 70% (Figure 6E and F). Thus, syndapin I considerably promotes the recruitment of dynamins to PS-containing membranes. Taken together, these experiments suggested that syndapin I KO directly leads to impaired membrane binding of dynamins.

Liposome-binding assays indeed revealed that syndapin I does not only promote membrane associations of dynamins but that this function is crucial for the membrane association of dynamins (Figure 6G and H). Despite the ability of dynamins to bind to liposomes themselves (Klein et al, 1998) and despite the presence of a variety of other BAR superfamily proteins in the syndapin I KO cytosol, all three dynamins in the syndapin I KO cytosol showed dramatically reduced membrane binding compared with WT (Figure 6G and H; Supplementary Figure S8).

This effect was dynamin specific. Other syndapin I-binding proteins, synapsins (Qualmann et al, 1999) and EHD proteins (Braun et al, 2005) as well as other dynamin-binding BAR proteins, endophilin I and amphiphysin I, and clathrin heavy chain were not negatively affected (Figure 6G and H).

Importantly, the membrane binding defects of all dynamins were completely rescued by addition of recombinant syndapin I to the syndapin I KO cytosol (Figure 6G and H). This demonstrates that the impairment of dynamin binding to the liposome membranes is specifically and solely caused by the lack of syndapin I. In contrast, the positive deviations of both amphiphysin and EHD were not responsive to syndapin I presence or absence.

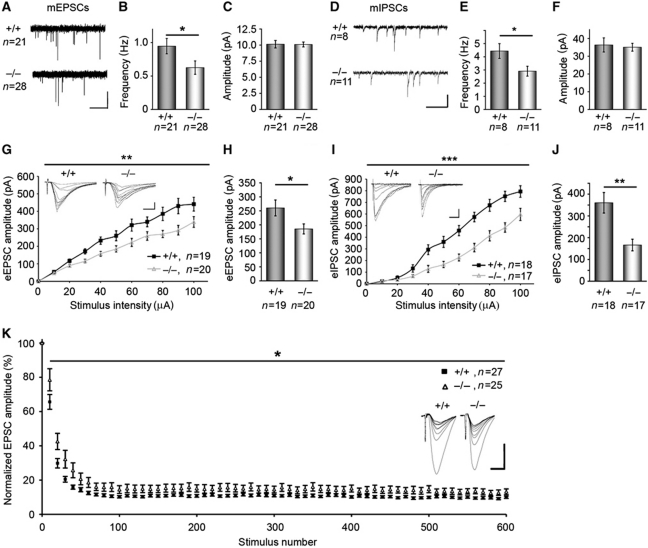

Syndapin I KO mice show reduced spontaneous quantal synaptic activity and impaired evoked synaptic transmission of both the excitatory and the inhibitory system

Syndapin I KO neurons showed impairments in endocytosis and our molecular analyses revealed that syndapin I is important for the membrane recruitment of dynamins. We next addressed the consequences of syndapin I KO for synaptic transmission by electrophysiological measurements in the hippocampus. Whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons of syndapin I KO mice indeed showed significantly reduced frequencies of both miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) (Figure 7A, B, D and E), while the peak amplitudes of both mEPSCs and mIPSCs did not differ from WT mice (Figure 7C and F). These results strongly indicate presynaptic defects in vesicle recycling in syndapin I KO neurons. This is well in line with the disturbances of endocytic processes observed in both hippocampal and ribbon presynapses (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 7.

Syndapin I KO causes defects in both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission. mEPSCs (A–C) and mIPSCs (D–F) recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons held at −60 mV. Representative traces are shown (mEPSCs, horizontal bar, 2.5 s; vertical bar, 10 pA; mIPSCs, horizontal bar, 0.5 s; vertical bar, 50 pA). The frequencies of both mEPSCs and mIPSCs were significantly reduced upon syndapin I KO (B, E), whereas the amplitudes were unchanged (C, F). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis, t-test; *P<0.05. (G–J) Measurement of eEPSCs (G; 19 and 20 slices of hippocampal CA1 regions from 9 (+/+) and 8 (−/−) animals) and eIPSCs (I; 18 and 17 slices from 9 (+/+) and 9 (−/−) animals). Inserts show example eEPSC and eIPSC traces (eEPSCs, horizontal bar, 10 ms; vertical bar, 100 pA; eIPSCs, horizontal bar, 100 ms; vertical bar, 200 pA). (H, J) eEPSC and eIPSC amplitudes, respectively, at 50 μA in WT and syndapin I KO. Data represent mean±s.e.m. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. (K) Plots of evoked EPSCs in response to 600 stimuli at 40 Hz, normalized to the amplitude of the first EPSC and averaged by 10 show a significantly reduced EPSCs amplitude depression in syndapin I KO mice. Two-way repeated measures-ANOVA; *P<0.05. The inserts depict examples of mean EPSCs during the first 100 stimuli of the train, averaged over 10 consecutive recordings. Horizontal bar, 200 pA; vertical bar, 10 ms.

As both excitatory and inhibitory synapses were affected by syndapin I KO, we next analysed whether syndapin I is present in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Immunohistological examinations showed a specific ubiquitous labelling of syndapin I throughout the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure S9A and B). In addition to its strong expression in excitatory neurons of pyramidal and granule cell layers, the protein is also highly expressed in inhibitory neurons as proven by additional costainings with parvalbumin (Supplementary Figure S9C–H).

Next, we measured whether the disturbed presynaptic quantal processes reported above did also result in overt changes in evoked excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs and eIPSCs, respectively). As shown in Figure 7G–J, we found significantly reduced eEPSC and eIPSC amplitudes in syndapin I KO mice upon an increasing strength of stimulation. The reduction was apparently larger for the inhibitory (eIPSCs) than for the excitatory system (eEPSCs) (Figure 7G–J). These data mirror eEPSC and eIPSC data reported for dynamin I KO (please compare Ferguson et al, 2007 with Figure 7H and J).

In order to address presynaptic plasticity, we measured the short-term depression of neurotransmission evoked by strong stimulations. Indicating a role of syndapin I in the integration of recently endocytosed vesicles into one of the major vesicle pools (e.g., the reserve pool), short-term depression was significantly less pronounced in syndapin I KO than in control slices (Figure 7K).

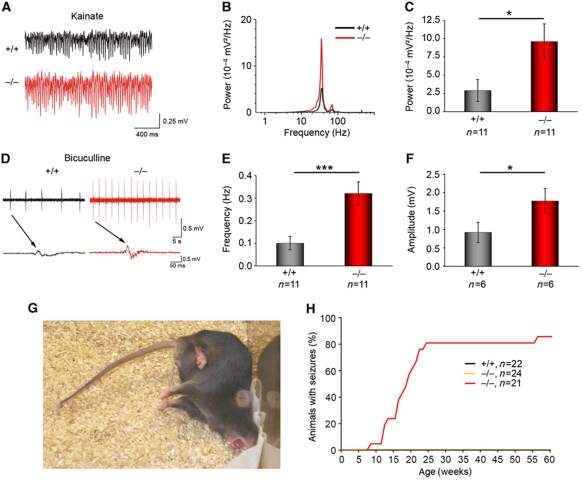

Syndapin I KO mice show severe defects in hippocampal network activity

We next analysed hippocampal network activities of WT and syndapin I KO mice under conditions of increased activity (Figure 8). The power of the oscillations at the gamma frequency band induced with kainic acid (KA; Dugladze et al, 2007) was dramatically increased by >230% in hippocampal slices of syndapin I KO mice (Figure 8A–C). These results show grossly altered hippocampal network responses upon stimulation.

Figure 8.

Syndapin I KO mice show altered hippocampal network activity and suffer from generalized seizures with tonic–clonic convulsions. (A) Examples of gamma rhythms induced by bath application of KA (400 nM) to 11 WT and 11 KO hippocampal slices (derived from 4 animals/genotype) analysed in the CA1 region. (B) Power spectra of the oscillations with one clear peak at the gamma frequency band. (C) In slices from syndapin I KO mice, gamma frequency oscillations had significantly larger power. (D–F) Epileptiform discharges induced by 5 μM bicuculline were significantly more frequent in syndapin I KO slices (11 slices from 4 animals/genotype) (E) and much stronger (6 slices from 4 animals/genotype) (F). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. (G, H) Homozygous syndapin I KO mice developed generalized seizures with tonic–clonic convulsions (G). Supplementary Movie 1 shows a typical sequence of the three behavioural phases (partial seizures, tonic–clonic convulsions and very quite pausing). Appearance of seizures was monitored for 22 (+/+), 24 (+/−) and 21 (−/−) animals, respectively, for 60 weeks (H).

We finally compared the responses of syndapin I KO and WT networks on increased activity by pharmacological reduction of inhibition (Figure 8D–F). Upon application of bicuculline, a GABAA receptor antagonist, syndapin I KO slices exhibited a >3-fold increase in the frequency of epileptiform discharges compared with WT (Figure 8D and E). Furthermore, the amplitudes of the discharges rose by >90% upon bicuculline application (Figure 8D and F). The much lower threshold for epileptiform activity evoked by bicuculline suggests that inhibitory circuits are significantly impaired by syndapin I deficiency.

Syndapin I KO mice suffer from generalized seizures

Since proper fine-tuning of neuronal network activities is crucial for sustaining physiological brain functions, we wondered whether phenotypes of syndapin I KO mice on the whole animal level could be identified that correlate with the above findings on the molecular, cellular and network levels.

In line with the electrophysiological data, homozygous syndapin I KO mice suffered from seizures with tonic–clonic convulsions without loss of consciousness in novelty situations (Figure 8G). A typical sequence consists of three behavioural phases, partial seizures, tonic–clonic convulsions and very quite pausing (Supplementary Movie 1). Statistical analyses revealed that seizure probabilities rose to 50 and 80% at 18 and 23 weeks of age, respectively (Figure 8H).

Discussion

F-BAR domain-containing proteins have been proposed to function as membrane curvature sensing and tubulating proteins that may coordinate membrane domains and the machineries for vesicle formation. As especially the brain relies on efficient and highly adaptable and scalable membrane trafficking processes, disturbances of any of these hypothesized functions should manifest in obvious malfunctions of the nervous system. Yet, recent KO studies of the F-BAR protein Toca/CIP4 did neither report any neurological phenotypes in flies nor in mice, although endocytosis in epithelial cells (Fricke et al, 2009) and adipocytes and fibroblasts (Feng et al, 2010) was affected. Also syndapin gene KO studies in flies did not show any impairments of the nervous system (Kumar et al, 2009). In contrast, our analyses clearly show that loss of the F-BAR protein syndapin I in mice leads to impairments in SV formation, SV size control, synaptic transmission and neuronal network activity, resulting in seizures of syndapin I KO animals. We propose that this apparent discrepancy of our results and syndapin KO in flies (Kumar et al, 2009) reflects the fact that the single syndapin in flies shows the highest similarity to the muscle-enriched syndapin III isoform in mammals. Consistently, fly syndapin was exclusively found on the muscle side of neuromuscular junctions (Kumar et al, 2009), whereas mammalian syndapin I is predominantly neuronal (Plomann et al, 1998; Qualmann et al, 1999). In line with this, knockdown of syndapin III in zebrafish also did not lead to any neuronal defects but resulted in embryonic notochord and somite development defects (Edeling et al, 2009). Distinct functions of the different syndapin isoforms in vertebrates are consistent with the unchanged syndapin II and III levels in syndapin I KO mice.

Our phenotypical analyses of syndapin I KO mice provide in vivo evidence for a physiological importance of the membrane-binding and topology-modulating F-BAR protein syndapin I in proper brain function. Syndapin I KO led to defective SV recycling in hippocampal cultures after strong stimulation and impaired formation of proper SVs in both synapses of the retina and of pyramidal cells of the hippocampus. In line with syndapin I's high expression in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, these defects manifested in impairments of spontaneous and evoked synaptic transmissions of both the excitatory and the inhibitory systems and in a reduced EPSCs amplitude depression. Together, these defects led to an increased hippocampal network activity with a dramatically lowered threshold for epileptiform discharges, strongly increased amplitudes of epileptiform discharges as well as a much higher power of induced gamma oscillations. As a consequence, syndapin I KO mice suffered from seizures.

Interestingly, the human gene locus 6p21.3, which also includes the syndapin I gene, is associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (Turnbull et al, 2005). This is one of the most frequent types of epileptic diseases in men (Delgado-Escueta et al, 2003). Seizures have also been reported for a few other mice deficient for neuronal membrane trafficking components, such as Bassoon, amphiphysin I and AP3B (Di Paolo et al, 2002; Altrock et al, 2003; Nakatsu et al, 2004). In some cases, seizures were correlated with hippocampal volume changes (Angenstein et al, 2007). Careful quantitative volumetric analyses of the brain architecture indeed revealed that also syndapin I KO mice show a statistically significant increase of specifically the hippocampal volume (Supplementary Figure S2).

Mechanistically, we propose that syndapin I's important role lies in its intimate work together with dynamins during vesicle fission. Several lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, syndapin I binds all three dynamin isoforms in vivo and it does so in a direct manner (Qualmann et al, 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000; this study).

Second, in both syndapin I (this study) and dynamin I deficient mice (Ferguson et al, 2007), vesicle formation processes still did occur but resulted in larger SVs.

Third, also the decreases in eEPSC and eIPSC amplitudes and the stronger impairment of inhibitory responses suggesting general impairments of mechanisms of synaptic transmission in syndapin I KO mice almost exactly phenocopy the effects observed for dynamin I KO mice (Ferguson et al, 2007).

Fourth, the endocytic defects seen in syndapin I KO ribbon synapses and the activity-dependent requirement of syndapin I in SV endocytosis are reminiscent of the endocytic defects present in presynaptic boutons of dynamin I KO mice (Ferguson et al, 2007). Functions in vesicle formation from larger tubular-vesicular structures may be related to both syndapin and dynamin also playing a role in vesicle formation from endosomal structures of non-neuronal cells (Braun et al, 2005; Håberg et al, 2008; Derivery et al, 2009; Schroeder et al, 2010).

Fifth, in particular, high-capacity retrieval processes, such as those occurring in the retina under physiological conditions, and those we evoked by strong stimulation of hippocampal neurons, are affected by syndapin I KO. Our FM1-43 dye recycling studies are also in line with membrane trafficking defects seen in the lamprey reticulospinal presynaptic compartment after ablation of syndapin function by antibody injections. These defects were particularly observed during very high frequency stimulation (Andersson et al, 2008). A role of syndapin I in high-capacity retrieval has also been proposed from observations in rat cerebellar granule neurons using proline-rich peptides sequestering the syndapin I SH3 domain (Clayton et al, 2009). The reduced synaptic fatigue at high frequencies (40 Hz) reported for inhibiting dynamin I rephosphorylation with Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors (Clayton et al, 2010) is reminiscent of the reduced EPSC depression at 40 Hz in slices of syndapin I KO hippocampi we observed.

It remains to be explained, why synaptic fatigue measured in form of field EPSCs was normal in syndapin I KO at 50 and 100 Hz and effects were only observed at 20 Hz (Supplementary Figure S10). Synaptic fatigue attenuations with a maximal effect at 20 Hz were observed in Bassoon mutant mice but the cause for this phenotype is unknown, too (Altrock et al, 2003).

Sixth, a tight interplay of dynamins and syndapin I in endocytosis is in line with structural and biochemical analyses showing that syndapin I prefers curved membranes, as it would be required for membrane remodelling during vesicle formation (Wang et al, 2009; our unpublished data).

Seventh, we have been able to directly demonstrate in reconstitutions with purified components that syndapin I is indeed able to enhance the binding of dynamin I to membranes by virtue of its lipid-binding F-BAR domain together with its dynamin-binding SH3 domain.

Eighth, and intriguingly considering the properties and presence of a plethora of proteins, which were also suggested to coordinate dynamin functions during SV formation, all dynamin isoforms were much more readily extractable from syndapin I KO than from WT brain extracts, as demonstrated by quantitative analyses of dynamins I, II and III.

Finally, we were able to show in brain cytosol from syndapin I KO mice, that explicitly recruitment of dynamins I, II and III to the curved membranes of liposomes is impaired and that these defects can be rescued by solely adding back syndapin I. These experiments prove that syndapin I is an important membrane-associating factor for all dynamin isoforms.

In line with our conclusions, recently, fitful mice, naturally occurring mutant mice carrying an A408T exchange in the first alternatively spliced region of dynamin 1a, were also reported to suffer from seizures with tonic–clonic convulsions and were introduced as a model of generalized idiopathic epilepsy (Boumil et al, 2010). Fitful and syndapin I KO mice show very similar sequences of behaviours during seizures. Also, the onset and development of this phenotype are very similar. In both fitful and syndapin I KO mice, animals with seizure were not observed before 2 months of age and for both strains 80% seizure probability was reached at about 6 months (Boumil et al, 2010; this study).

The increased penetrance of the syndapin I KO phenotype in adult mice may relate to the developmental increase of the syndapin I expression reaching 0.8 mg/g total brain protein in mature animals (Supplementary Figure S11).

Considering the similarities with syndapin I KO mice, we propose that the molecular reasons for the fitful phenotypes and for the observed deviations from dynamin I KO phenotypes (Ferguson et al, 2007, 2009; Boumil et al, 2010) include strong dominant-negative effects on dynamin-binding proteins, such as syndapin I, which is likely to still bind to dynamin A408T because the fitful mutation (Boumil et al, 2010) is well separated from the C-terminal domain of dynamin binding to syndapin I (Qualmann et al, 1999). Dominant-negative effects of dynamin I A408T against the collective of dynamin-binding proteins and partial functional redundancies of syndapin I with other dynamin-binding proteins would also explain, why—albeit similar—fitful phenotypes are stronger than syndapin I KO phenotypes.

The reduced, but not completely lost membrane association of dynamins in syndapin I KO mice also indicates that other dynamin-binding proteins with properties similar to syndapin I exist and help to ensure proper dynamin membrane association and function. This may be one reason why dynamin I KO results in severe synaptic transmission defects and mice die at an age of ∼2 weeks (Ferguson et al, 2007) and dynamin II KO even leads to embryonic lethality (Ferguson et al, 2009), whereas syndapin I KO results in milder phenotypes. This is in contradiction to the proposed function of syndapin I as the exclusive phosphosensor of dynamin (Anggono et al, 2006) or questions the importance of sensing the dynamin phosphorylation status for normal brain function (Clayton et al, 2009). Prime candidates for proteins sharing some functional redundancy with syndapin I are the other syndapin family members, syndapins II and III, which are also expressed in brain. Furthermore, other proteins of the BAR superfamily may assist. However, in contrast to syndapin I's importance for specifically recruiting dynamin, amphiphysin was found to be important for tethering the AP2 complex and clathrin to membranes (Di Paolo et al, 2002) and the F-BAR protein FCHo was recently shown to specifically recruit eps15 and intersectin and to thereby play an important role in very early steps of endocytic coat formation (Henne et al, 2010).

Therefore, it seems that the so-called accessory factors of the BAR domain superfamily proteins play crucial but very distinct roles in membrane targeting of the protein machineries required at the various stages of endocytic vesicle formation. Our analyses show that syndapin I acts as a pivotal membrane anchoring factor for the vesicle fission-mediating dynamins in the regeneration of SVs and that this function is indispensable for proper function of the mammalian brain.

Materials and methods

Generation and examinations of syndapin I KO mice

Syndapin I gene organization was established by sequencing a suitable clone of the BAC Mouse ES-129/SvJ-library (Incyte Genomics) identified by PCR screening with an exon1 probe. Based on genomic DNA and cDNA, a targeting vector was constructed in pBluescript. Linearized targeting vector was electroporated into ES cells according to Talts et al (1999). ES cells were screened for correct homologous recombination by Southern blot analysis and PCR. Syndapin I KO mice were obtained via mating with mice ubiquitously expressing Cre recombinase (TgN(CMV-Cre)1AN; Nagy et al, 1998). For genotyping, DNA of mouse tail biopsies was extracted with 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.4 mg Proteinase K. After inactivation, a high-speed supernatant was analysed by PCR.

Body weights of 20–29 animals per gender and genotype were examined during 3–8 weeks after birth. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student's t-test.

First occurrence of seizures upon transfer into new cages and survival was analysed over a period of 60 weeks.

Manganese-enhanced MRI and volumimetric analysis of various brain structures of adult mice was performed as previously described (Angenstein et al, 2007). Due to the non-invasive character of this method, it is not prone to sectioning and incubation artifacts (Angenstein et al, 2007). Statistical analysis was performed using Mann–Whitney U-test.

Primers and antibodies

Primers used for BAC clone screenings, Southern blot probes, analytical PCRs, genotyping for WT, KO and Cre allele, respectively, as well as primers used for cloning of dynamin III PRD are listed in Supplementary data.

Primary and secondary antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary data.

Quantitative western blot analysis

Brain homogenizations were done according to Dharmalingam et al (2009).

Homogenates of adult male mice (n=5 for +/+ and −/−; n=2 for +/−) were divided into two aliquots, one was used directly for expression analysis of proteins in brain homogenates and the second was subjected to centrifugation at 100 000 g for 1 h to yield 1% Triton X-100 soluble fractions. The observed effects for dynamins in Triton X-100 soluble brain fractions were reproduced with additional brains (n=5 for +/+ and n=7 for −/−). Statistical analyses were performed using Mann–Whitney U-test.

For actin quantification, synaptosomes were prepared as described previously (Wyneken et al, 2001). Harvested synaptosomes were resuspended in 5 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.1, 1 mM EDTA, 0.32 M sucrose, equilibrated at 37°C for 5 min, and lysed by adding an equal volume of 2 × PHEM extraction buffer (120 mM PIPES, 50 mM HEPES, 20 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.3). After solubilization on ice for 15 min, F-actin was separated from G-actin by a 20-min centrifugation at 100 000 g according to Pilo Boyl et al (2007). For all analyses, quantitative western blotting was carried out using an LI-COR Odyssey system.

Immunocytochemistry and histology

Primary dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared as described (Banker and Goslin, 1988). Cell suspensions of hippocampi prepared from mice (P0-P1) were obtained by trypsination and trituration and plated onto poly-L-lysine coated glass coverslips. After 1 h at 37°C (5% CO2), coverslips were transferred into dishes containing a 70–80% confluent monolayer of glia cells in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, 2 mM glutamine, antibiotics and antimycotics. After 3 DIV, 5 μM 1-β-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine was added. After 20–22 DIV, cells were fixed (4% PFA, 4% sucrose in PBS) and subjected to immunocytochemistry as described (Kessels et al, 2001). For extraction experiments, cultures were treated 3 min at RT with HCB buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM MgCl2) containing 10 mM NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100 prior to fixation.

Immunocytochemistry and histology of brain sections were performed as follows: 12-week-old WT and syndapin I KO mice were anaesthetised and perfused transcardially with 50 ml of PBS to flush the vascular system, followed by 50 ml 4% PFA. Brains were extracted and post-fixed in 50 ml PFA for 24 h, washed in PBS and dehydrated in 30% sucrose for 48 h. Cryosectioning was performed using a Leica SM 2010R Sliding Microtome.

55 μm parasagittal slices were incubated in blocking solution (0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 0.25% Triton X-100, 5% goat serum) for 1 h and incubated for 48 h with primary antibodies. After washing, secondary antibodies were applied for 24 h and sections were washed with PBS. F/G-actin ratio quantification was performed on slices incubated in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min. After washing, slices were incubated for 24 h with Alexa Fluor®488-conjugated DNAse I and Alexa Fluor®568-conjugated phalloidin. All sections were washed with PBS and incubated with DAPI for 30 min. Sections were embedded in Fluoromont-G (SouthernBiotech). Sections were examined using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Images from WT and syndapin I KO animals were recorded digitally using identical settings.

Fluorescence intensities of the dentate gyrus inner molecular layer were measured on unprocessed images (ImageJ software). Quantification was performed on 5 ROIs of each slice, averaged per slice and statistically analysed using the two-tailed Student's t-test.

Nissl stainings were done with kresylviolet and embedded in Entellan (Merck).

Immunocytochemistry of the retina was performed as described (tom Dieck et al, 2005).

EM analyses

Anaesthetized adult male WT and syndapin I KO animals were perfused transcardially with 0.9% NaCl, and then with 2% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1% sucrose, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3. Fixed brain pieces of the hippocampal CA3 region were transferred into the above fixative, extensively washed with PBS and sectioned into thin slices. Brain slices were incubated for 1 h at RT in 2% OsO4, 0.8% K4[Fe(CN)6] in PBS, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and incubated for 30 min with 2% uranyl acetate in ethanol. After washing with ethanol, slices were embedded in EPON and prepared for EM. Samples were examined with a Zeiss EM902A and documented digitally (CCD camera FastScan-114 (TVIPS)).

For EM evaluations of retinae, adult male mice (n=12 for +/+ and −/−) were examined under various light conditions. In experiment #1, dark-adapted retinae were analysed after acute light exposure (5–20 min). In experiment #2, retinae were prepared after 4 h of light exposure. Removal of retinae and subsequent fixation was performed within 5 s to avoid fixation artefacts. Retinae were immediately processed for EM as described (Spiwoks-Becker et al, 2001). In randomly selected sections, the retinae were qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated using a Zeiss LEO TEM 906E and Analysis 3.2 software (Soft Imaging Systems).

All morphological analyses were performed blind. For statistical analysis, two-tailed Student's t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test, respectively, were used.

Immunoprecipitation of syndapin I-containing complexes

Immunoprecipitation from brain extracts was carried out with syndapin I-specific antibodies in HCB buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor Complete®EDTA-free (Roche) using ProteinA-Agarose (Santa Cruz) as described (Braun et al, 2005).

Purification of dynamin and syndapin I

Dynamin was purified from rat brain as described (Stowell et al, 1999). Syndapin I cloned into pBAT4 vector (Kessels et al, 2000) was overexpressed in E. coli and affinity purified using GST-dynamin Iab PRD.

Phospholipid binding plate assay

Lipid-binding assays were done according to Powell et al (2000) and adapted to the LI-COR Odyssey fluorescence detection system. The bottom of wells (96-well Optical-Bottom Plates, Nunc) was coated with or without lipid mixture (PS:PC ratio, 1:3). Incubations were initiated by dynamin or syndapin I addition (0.8 μg/well). After thorough washing, bound proteins were detected with appropriate antibodies (pan-dynamin (800 nm); syndapin I (680 nm)) using the LI-COR Odyssey system. Analysis of syndapin I-mediated improved lipid binding of dynamin was carried out by preincubating the lipids with syndapin I or lipid-free BSA and subsequent binding of dynamin.

Liposome-binding assay

Liposomes made of lipids from Folch fraction I (Sigma) and brain cytosol from WT and syndapin I KO mice were prepared as described (Reeves and Dowben, 1969; Kinuta et al, 2002). Liposomes (0.2 mg/ml) were incubated with brain cytosol (0.1 mg/ml) for 15 min at 37°C in cytosolic buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 25 mM KCl, 2.5 mM Mg-acetate, 100 mM K-glutamate, Complete™ EDTA-free), then harvested at 50 000 g for 30 min and washed extensively with cytosolic buffer. Quantitative western blot analyses of bound proteins were performed using the LI-COR Odyssey system.

FM1-43 dye recycling

Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared as described (Sinning et al, 2011). Hippocampal cultures were field stimulated with platinum electrodes (Chamlide EC, Live Cell Instruments, Korea) at DIV 14–16. SV turnover was analysed as described previously (Clayton and Cousin, 2008) with some modifications. Cells were continuously superfused (2 ml/min, RT) with recording solution (containing in mM: NaCl, 170; KCl, 3.5; KH2PO4, 0.4; TES, 20; NaHCO3, 5; glucose, 5; Na2SO4, 1.2; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2: 1.3; pH 7.4). After 10 min wash, nerve terminals were loaded with FM1-43 (10 μM) and SV turnover was evoked with 300 stimuli at 10 Hz (1 ms current pulses). In an independent experiment, calcium imaging confirmed that stimuli evoked action potentials. After 10 min wash, cells were exposed twice to 50 mM KCl in recording solution (NaCl, 123.5 mM to maintain osmolarity) for 40 s and dye unloading (ΔF1) was visualized (1 image/s; Axio-Observer with an AxioCam MRm (Zeiss); × 63 water-immersion objective). After 10 min wash, the protocol was repeated with 800 stimuli at 80 Hz to yield ΔF2. ROIs corresponding to nerve terminals (20/measurement, ø 1 μm) were analysed according to Clayton and Cousin (2008) (⩾5 recordings of at least two independent preparations of 5 (+/+) and 8 (−/−) animals).

Examination of hippocampal network activity in CA1 region

Experiments were performed on transverse slices of adult WT and syndapin I KO mice (n=4 animals each; 400 μm thickness) obtained as described (Gloveli et al, 2005). The slices were transferred to an interface chamber continuously perfused with prewarmed (34°C) oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF)-1 (containing in mM: NaCl, 126; KCl, 3; NaH2PO4, 1.25; CaCl2, 2; MgSO4, 2; NaHCO3, 24; glucose, 10). Network oscillatory activity was induced by KA (400 nM by bath). Network activities in slices from WT and syndapin I KO mice were recorded simultaneously following bath application of KA alone or of bicuculline (5 μM) and KA for 20–30 min. Extracellular field recordings in the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region were similar to those described in Gloveli et al (2005). The two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistics.

Electrophysiological measurements

Brains of 31–34-week-old male mice were placed in ice-cold ACSF-2 (containing in mM: NaCl, 124; KCl, 4.9;. KH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25.6; CaCl2, 2; MgSO4, 2; glucose, 10; saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.3–7.4)). Vibratome-cut hippocampal transverse slices (400 μm) were stored at RT in ACSF-2. After recovery for at least 1 h, an individual slice was transferred to a submerged-type recording chamber and continuously superfused with ACSF-2 (2.5 ml/min).

Patch-clamp recordings of mIPSCs and eIPSCs from CA1 pyramidal neurons were done as described (Banks et al, 2002) with minor modifications. The intra-pipette solution contained 140 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgATP and 5 mM QX-314, pH 7.3 (pipette resistance 2–5 MΩ). ACSF-2 was supplemented with CNQX (20 μM) and AP5 (40 μM). Neurons in whole-cell mode were held at −60 mV. For mIPSCs, 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) was added to the bath solution. Access resistance was 10–20 MΩ and was then compensated to 70%. Data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz and acquired at 10 kHz.

eEPSCs were recorded from CA1 pyramidal cells in whole-cell mode with glass microelectrodes filled with a solution containing 135 mM K-Gluconate, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM K-HEPES, 20 mM glucose; pH 7.25 (pipette resistance 3–6 MΩ). eEPSCs were recorded at holding potential −60 mV. Responses of eEPSCs were measured in the presence of 100 μM picrotoxin in ACSF-2.

mEPSCs were recorded at holding potential −60 mV, with the same pipette solution as for eEPSCs, and TTX (1 μM) was added.

Short-term depression was evoked as described (Clayton et al, 2010). Patch pipettes contained ACSF-3 in mM CsMeSO4, 135; NaCl, 4; HEPES, 10, EGTA, 0.1; Na-Phosphocreatine, 10; MgATP, 4; NaGTP, 0.3; QX-314, 5; pH 7.3; pipette resistances 3–5 MΩ. The external ACSF-3 was supplemented with 50 μM picrotoxin. A cut between CA3 and CA1 regions surgically isolated the latter. eEPSCs were induced by trains of 600 pulses (70–90 μA, 100 μs pulse width) delivered at 40 Hz 10 min before recording, slices were challenged with an identical prepulse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our laboratory members N Haag, W Seul, B Schade and A Kreusch as well as I von Graevenitz (University of Mainz), K Eraets (KU Leuven), K Krautwald, K Hartung (IfN, Magdeburg), R Zienecker (University of Ulm), A Hübner (University of Jena), M Westermann and C Kämnitz (EM facility, University of Jena) for valuable help. We thank B Lang for purification of GST-dynamin IIIbaa PRD and N Koch for supporting the generation of syndapin I KO mice. We also thank our colleagues listed in Materials and methods for plasmids and antibodies. This study was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft QU116/2-1-4, 5-1, 6-1 and 7-1 (to BQ), SFB TR3/B5 and GL254/5-1 (to TG), BO1718/3-1 (to TMB), SFB497/B8 (to TMB), EU Grant FP6 Epicure (to TG), KU Leuven projects OT06/23 and IDO06/004 (to DB), and a KU Leuven fellowship (to TA).

Author contributions: DK, IS-B, VS, DB, TG, MMK and BQ designed research. DK, IS-B, VS, ASi, TD, ASt, RA, JG, SS, AM, FA, TA, AD, MM, StD, MMK and BQ performed research and analysed data. RS, DB and TG analysed data. TMB, RF and CAH provided analytical tools. DK, MMK and BQ wrote the paper with important contributions from IS-B, DB and TG.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Altrock WD, tom Dieck S, Sokolov M, Meyer AC, Sigler A, Brakebusch C, Fässler R, Richter K, Boeckers TM, Potschka H, Brandt C, Löscher W, Grimberg D, Dresbach T, Hempelmann A, Hassan H, Balschun D, Frey JU, Brandstätter JH, Garner CC et al. (2003) Functional inactivation of a fraction of excitatory synapses in mice deficient for the active zone protein bassoon. Neuron 37: 787–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson F, Jakobsson J, Löw P, Shupliakov O, Brodin L (2008) Perturbation of syndapin/PACSIN impairs synaptic vesicle recycling evoked by intense stimulation. J Neurosci 28: 3925–3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angenstein F, Niessen HG, Goldschmidt J, Lison H, Altrock WD, Gundelfinger ED, Scheich H (2007) Manganese-enhanced MRI reveals structural and functional changes in the cortex of Bassoon mutant mice. Cereb Cortex 17: 28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anggono V, Smillie KJ, Graham ME, Valova VA, Cousin MA, Robinson PJ (2006) Syndapin I is the phosphorylation-regulated dynamin I partner in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nat Neurosci 9: 752–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker G, Goslin K (1988) Developments in neuronal cell culture. Nature 336: 185–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, Hardie JB, Pearce RA (2002) Development of GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 88: 3097–3107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumil RM, Letts VA, Roberts MC, Lenz C, Mahaffey CL, Zhang ZW, Moser T, Frankel WN (2010) A missense mutation in a highly conserved alternate exon of dynamin-1 causes epilepsy in fitful mice. PLoS Genet 8: pii: e1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun A, Pinyol R, Dahlhaus R, Koch D, Fonarev P, Grant BD, Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2005) EHD proteins associate with syndapin I and II and such interactions play a crucial role in endosomal recycling. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3642–3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EL, Anggono V, Smillie KJ, Chau N, Robinson PJ, Cousin MA (2009) The phospho-dependent dynamin-syndapin interaction triggers activity-dependent bulk endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. J Neurosci 24: 7706–7717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EL, Cousin MA (2008) Differential labelling of bulk endocytosis in nerve terminals by FM dyes. Neurochem Int 53: 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EL, Sue N, Smillie KJ, O’Leary T, Bache N, Cheung G, Cole AR, Wyllie DJ, Sutherland C, Robinson PJ, Cousin MA (2010) Dynamin I phosphorylation by GSK3 controls activity-dependent bulk endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nat Neurosci 13: 845–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa SR, Sou E, Xie J, Yarber FA, Okamoto CT, Pidgeon M, Kessels MM, Mircheff AK, Schechter JE, Qualmann B, Hamm-Alvarez SF (2003) Impairing actin filament or syndapin functions promotes accumulation of clathrin-coated vesicles at the apical plasma membrane of acinar epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 11: 4397–4413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Escueta AV, Perez-Gosiengfiao KB, Bai D, Bailey J, Medina MT, Morita R, Suzuki T, Ganesh S, Sugimoto T, Yamakawa K, Ochoa A, Jara-Prado A, Rasmussen A, Ramos-Peek J, Cordova S, Rubio-Donnadieu F, Alonso ME (2003) Recent developments in the quest for myoclonic epilepsy genes. Epilepsia 11: 13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Sousa C, Gautier JJ, Lombard B, Loew D, Gautreau A (2009) The Arp2/3 activator WASH controls the fission of endosomes through a large multiprotein complex. Dev Cell 5: 712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmalingam E, Haeckel A, Pinyol R, Schwintzer L, Koch D, Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2009) F-BAR proteins of the syndapin family shape the plasma membrane and are crucial for neuromorphogenesis. J Neurosci 42: 13315–13327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G, Sankaranarayanan S, Wenk MR, Daniell L, Perucco E, Caldarone BJ, Flavell R, Picciotto MR, Ryan TA, Cremona O, De Camilli P (2002) Decreased synaptic vesicle recycling efficiency and cognitive deficits in amphiphysin 1 knockout mice. Neuron 33: 789–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugladze T, Vida I, Tort AB, Gross A, Otahal J, Heinemann U, Kopell NJ, Gloveli T (2007) Impaired hippocampal rhythmogenesis in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17530–17535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeling MA, Sanker S, Shima T, Umasankar PK, Höning S, Kim HY, Davidson LA, Watkins SC, Tsang M, Owen DJ, Traub LM (2009) Structural requirements for PACSIN/Syndapin operation during zebrafish embryonic notochord development. PLoS One 12: e8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Hartig SM, Bechill JE, Blanchard EG, Caudell E, Corey SJ (2010) The Cdc42-interacting protein-4 (CIP4) gene knock-out mouse reveals delayed and decreased endocytosis. J Biol Chem 285: 4348–4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Brasnjo G, Hayashi M, Wölfel M, Collesi C, Giovedi S, Raimondi A, Gong LW, Ariel P, Paradise S, O’toole E, Flavell R, Cremona O, Miesenböck G, Ryan TA, De Camilli P (2007) A selective activity-dependent requirement for dynamin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Science 316: 570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Raimondi A, Paradise S, Shen H, Mesaki K, Ferguson A, Destaing O, Ko G, Takasaki J, Cremona O, O’ Toole E, De Camilli P (2009) Coordinated actions of actin and BAR proteins upstream of dynamin at endocytic clathrin-coated pits. Dev Cell 6: 811–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GQ (1988) A morphometric analysis of synaptic vesicle distributions. Brain Res 475: 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke R, Gohl C, Dharmalingam E, Grevelhörster A, Zahedi B, Harden N, Kessels M, Qualmann B, Bogdan S (2009) Drosophila Cip4/Toca-1 integrates membrane trafficking and actin dynamics through WASP and SCAR/WAVE. Curr Biol 19: 1429–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A, Perera R, Roux A, Spasov K, Destaing O, Egelman EH, De Camilli P, Unger VM (2008) Structural basis of membrane invagination by F-BAR domains. Cell 5: 807–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A, Unger VM, De Camilli P (2009) The BAR domain superfamily: membrane-molding macromolecules. Cell 2: 191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloveli T, Dugladze T, Rotstein HG, Traub RD, Monyer H, Heinemann U, Whittington MA, Kopell NJ (2005) Orthogonal arrangement of rhythm-generating microcircuits in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 13295–13300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håberg K, Lundmark R, Carlsson SR (2008) SNX18 is an SNX9 paralog that acts as a membrane tubulator in AP-1-positive endosomal trafficking. J Cell Sci 9: 1495–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Sultan P (1995) Variation in the number, location, and size of synaptic vesicles provides an anatomical basis for the non-uniform probability of release at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Neuropharmacology 34: 1387–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne WM, Boucrot E, Meinecke M, Evergren E, Vallis Y, Mittal R, McMahon HT (2010) FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science 328: 1281–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne WM, Kent HM, Ford MG, Hegde BG, Daumke O, Butler PJ, Mittal R, Langen R, Evans PR, McMahon HT (2007) Structure and analysis of FCHo2 F-BAR domain: a dimerizing and membrane recruitment module that effects membrane curvature. Structure 15: 839–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdart F, Girard-Nau N, Morin F, Voisin P, Vannier B (2005) The regulatory subunit of PDE6 interacts with PACSIN in photoreceptors. Mol Vis 11: 1061–1070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Erdmann KS, Roux A, Habermann B, Werner H, De Camilli P (2005) Dynamin and the actin cytoskeleton cooperatively regulate plasma membrane invagination by BAR and F-BAR proteins. Dev Cell 9: 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Dong J, Leibig W, Westermann P, Qualmann B (2006) Complexes of syndapin II with dynamin II promote vesicle formation at the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Sci 8: 1504–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG (2000) Association of mouse actin-binding protein 1 (mAbp1/SH3P7), an Src kinase target, with dynamic regions of the cortical actin cytoskeleton in response to Rac1 activation. Mol Biol Cell 11: 393–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG, Qualmann B (2001) Mammalian Abp1, a signal-responsive F-actin-binding protein, links the actin cytoskeleton to endocytosis via the GTPase dynamin. J Cell Biol 153: 351–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2002) Syndapins integrate N-WASP in receptor-mediated endocytosis. EMBO J 21: 6083–6094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2004) The syndapin protein family: linking membrane trafficking with the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 117: 3077–3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2006) Syndapin oligomers interconnect the machineries for endocytic vesicle formation and actin polymerization. J Biol Chem 281: 13285–13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinuta M, Yamada H, Abe T, Watanabe M, Li SA, Kamitani A, Yasuda T, Matsukawa T, Kumon H, Takei K (2002) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate stimulates vesicle formation from liposomes by brain cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 5: 2842–2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DE, Lee A, Frank DW, Marks MS, Lemmon MA (1998) The pleckstrin homology domains of dynamin isoforms require oligomerization for high affinity phosphoinositide binding. J Biol Chem 273: 27725–27733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Alla SR, Krishnan KS, Ramaswami M (2009) Syndapin is dispensable for synaptic vesicle endocytosis at the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. Mol Cell Neurosci 2: 234–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Moens C, Ivanyi E, Pawling J, Gertsenstein M, Hadjantonakis AK, Pirity M, Rossant J (1998) Dissecting the role of N-myc in development using a single targeting vector to generate a series of alleles. Curr Biol 8: 661–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu F, Okada M, Mori F, Kumazawa N, Iwasa H, Zhu G, Kasagi Y, Kamiya H, Harada A, Nishimura K, Takeuchi A, Miyazaki T, Watanabe M, Yuasa S, Manabe T, Wakabayashi K, Kaneko S, Saito T, Ohno H (2004) Defective function of GABA-containing synaptic vesicles in mice lacking the AP-3B clathrin adaptor. J Cell Biol 167: 293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilo Boyl P, Di Nardo A, Mulle C, Sassoè-Pognetto M, Panzanelli P, Mele A, Kneussel M, Costantini V, Perlas E, Massimi M, Vara H, Giustetto M, Witke W (2007) Profilin2 contributes to synaptic vesicle exocytosis, neuronal excitability, and novelty-seeking behavior. EMBO J 26: 2991–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomann M, Lange R, Vopper G, Cremer H, Heinlein UA, Scheff S, Baldwin SA, Leitges M, Cramer M, Paulsson M, Barthels D (1998) PACSIN, a brain protein that is upregulated upon differentiation into neuronal cells. Eur J Biochem 256: 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KA, Valova VA, Malladi CS, Jensen ON, Larsen MR, Robinson PJ (2000) Phosphorylation of dynamin I on Ser-795 by protein kinase C blocks its association with phospholipids. J Biol Chem 16: 11610–11617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann B, Kelly RB (2000) Syndapin isoforms participate in receptor-mediated endocytosis and actin organization. J Cell Biol 148: 1047–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann B, Koch D, Kessels MM (2011) Let's go bananas: revisiting the endocytic bar code. EMBO J 30: 3501–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann B, Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Kelly RB (1999) Syndapin I, a synaptic dynamin-binding protein that associates with the neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Mol Biol Cell 10: 501–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JP, Dowben RM (1969) Formation and properties of thin-walled phospholipid vesicles. J Cell Physiol 1: 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TA (2006) A pre-synaptic to-do list for coupling exocytosis to endocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 4: 416–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvarezza SB, Deborde S, Schreiner R, Campagne F, Kessels MM, Qualmann B, Caceres A, Kreitzer G, Rodriguez-Boulan E (2009) LIM kinase 1 and cofilin regulate actin filament population required for dynamin-dependent apical carrier fission from the trans-Golgi network. Mol Biol Cell 1: 438–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T, Stevens CF (1997) Quantitative ultrastructural analysis of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci 17: 5858–5867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder B, Weller SG, Chen J, Billadeau D, McNiven MA (2010) A Dyn2–CIN85 complex mediates degradative traffic of the EGFR by regulation of late endosomal budding. EMBO J 29: 3039–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwintzer L, Koch N, Ahuja R, Grimm J, Kessels MM, Qualmann B (2011) The functions of the actin nucleator Cobl in cellular morphogenesis critically depend on syndapin I. EMBO J 30: 3147–3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada A, Niwa H, Tsujita K, Suetsugu S, Nitta K, Hanawa-Suetsugu K, Akasaka R, Nishino Y, Toyama M, Chen L, Liu ZJ, Wang BC, Yamamoto M, Terada T, Miyazawa A, Tanaka A, Sugano S, Shirouzu M, Nagayama K, Takenawa T et al. (2007) Curved EFC/F-BAR-domain dimers are joined end to end into a filament for membrane invagination in endocytosis. Cell 129: 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson F, Hussain NK, Qualmann B, Kelly RB, Kay BK, McPherson PS, Schmid SL (1999) SH3-domain-containing proteins function at distinct steps in clathrin-coated vesicle formation. Nat Cell Biol 1: 119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning A, Liebmann L, Kougioumtzes A, Westermann M, Bruehl C, Hübner CA (2011) Synaptic glutamate release is modulated by the Na+-driven Cl−/HCO3− exchanger Slc4a8. J Neurosci 31: 7300–7311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiwoks-Becker I, Vollrath L, Seeliger MW, Jaissle G, Eshkind LG, Leube RE (2001) Synaptic vesicle alterations in rod photoreceptors of synaptophysin-deficient mice. Neuroscience 107: 127–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell MH, Marks B, Wigge P, McMahon HT (1999) Nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in dynamin: evidence for a mechanochemical molecular spring. Nat Cell Biol 1: 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof TC (2004) The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 509–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talts JF, Brakebusch C, Fässler R (1999) Integrin gene targeting. Methods Mol Biol 129: 153–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- tom Dieck S, Altrock WD, Kessels MM, Qualmann B, Regus H, Brauner D, Fejtová A, Bracko O, Gundelfinger ED, Brandstätter JH (2005) Molecular dissection of the photoreceptor ribbon synapse: physical interaction of Bassoon and RIBEYE is essential for the assembly of the ribbon complex. J Cell Biol 5: 825–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J, Lohi H, Kearney JA, Rouleau GA, Delgado-Escueta AV, Meisler MH, Cossette P, Minassian BA (2005) Sacred disease secrets revealed: the genetics of human epilepsy. Hum Mol Genet 14: 2491–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmaier SM, Edwards RH (2007) Do different endocytic pathways make different synaptic vesicles? Curr Opin Neurobiol 17: 374–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Navarro MV, Peng G, Molinelli E, Goh SL, Judson BL, Rajashankar KR, Sondermann H (2009) Molecular mechanism of membrane constriction and tubulation mediated by the F-BAR protein Pacsin/Syndapin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 31: 12700–12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyneken U, Smalla KH, Marengo JJ, Soto D, de la Cerda A, Tischmeyer W, Grimm R, Boeckers TM, Wolf G, Orrego F, Gundelfinger ED (2001) Kainate-induced seizures alter protein composition and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function of rat forebrain postsynaptic densities. Neuroscience 102: 65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.