Summary

Over the past several years, there have been remarkable advances in our understanding of how commensal organisms shape host immunity. Although the full cast of immunogenic bacteria and their immunomodulatory molecules remains to be elucidated, lessons learned from the interactions between bacterial zwitterionic polysaccharides (ZPSs) and the host immune system represent an integral step toward better understanding how the intestinal microbiota effect immunologic changes. Somewhat paradoxically, ZPSs, which are found in numerous commensal organisms, are able to elicit both proinflammatory and immunoregulatory responses; both of these outcomes involve fine-tuning the balance between T-helper 17 cells and interleukin-10–producing regulatory T cells. In this review, we discuss the immunomodulatory effects of the archetypal ZPS, Bacteroides fragilis PSA. In addition, we highlight some of the opportunities and challenges in applying these lessons in clinical settings.

Keywords: immune system ontogeny, Bacteroides fragilis, polysaccharide A (PSA), zwitterionic polysaccharides (ZPSs), host-microbe interactions

Introduction

Since Robert Koch first demonstrated in 1876 that microorganisms can cause disease (1), investigators have predominantly focused their studies on pathogenic bacteria. However, even as early as 1909, some investigators lamented that this increased study of pathogens was diverting attention away from studies of the normal flora (2). Over the past century, it has become clear that many common infectious diseases are caused by commensal organisms (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes) that have escaped their normal habitats (3). Until very recently, the main corpus of work in this field has examined interactions of these commensal organisms with their non-native environment (i.e. their pathogenic roles) rather than the symbiotic relationships between host and microbiota.

The human body contains an estimated 10–100 times more bacterial cells than human cells, prompting some to question ‘who parasitizes whom’ (3–5). The idea that commensal organisms are vital for the welfare of the host dates back to Pasteur, who wrote in 1885 that he was interested in trying to ‘nurture a young animal from birth with such alimentary products which have been artificially and completely deprived of the common microbes … if I would have the time – I would undertake such an experiment with the preconceived idea that under these circumstances life would become impossible’ (6). Although it took nearly a quarter of a century to prove Pasteur’s ‘preconceived idea’ incorrect (7), studies with germ-free (GF) animals have validated the critical role of the microbiota in maintaining the host’s well-being. For example, intestinal commensal organisms aid with metabolism of nutrients, outcompete pathogenic bacteria by occupying niches within the gut, play a critical role in development of the intestinal epithelium, and serve an indispensable function in proper maturation of the immune system (8–11). The gut flora has been shown to confer many benefits, but its dysregulation may also play a role in the pathogenesis of many diseases characterized by inflammation and aberrant immune responses, such as inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, asthma, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis (12–16).

These observations underscore the potential role of microorganisms, particularly the gut microbiota, in regulating human health and disease. Over the past few decades, abundant epidemiologic data have revealed an inverse correlation between early exposure to bacteria and the incidence of autoimmune and/or atopic diseases (17–19). This correlation led to the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, which has evolved over the past two decades and suggests that inadequacies in microbial exposure—in combination with genetic susceptibilities—lead to a collapse of the normally highly coordinated, homeostatic immune response (19, 20). Overall, these epidemiologic findings strongly suggest that bacterial exposure shapes the human microbiota, which can ultimately augment the host immune response to a variety of antigens. Except for a few recent breakthroughs, the specificity of the bacteria and the mechanisms through which they impact the host immune system remain largely unknown. Along these lines, our group has spent more than three decades investigating interactions of the intestinal commensal Bacteroides fragilis with the host immune system, identifying unique immunomodulatory effects of commensal-expressed polysaccharides.

The yin: bacterial polysaccharides as proinflammatory agents

Biology of the B. fragilis capsular polysaccharide complex

B. fragilis is a gram-negative anaerobe and an integral component of the gut microflora of most mammals (21). Although members of the genus Bacteroides are numerically the most abundant intestinal organisms, B. fragilis itself represents only a very small fraction of the fecal flora in humans (22). Although a minor component of the flora, B. fragilis is the most commonly isolated organism from clinical cases of intra-abdominal abscess (23, 24). This discrepancy in relative abundances suggests that B. fragilis may have a unique role in abscess formation. Studies of murine models involving intraperitoneal (IP) implants of B. fragilis combined with an adjuvant of sterile cecal contents have demonstrated that the capsular polysaccharide complex (CPC) is critical for abscess formation (25, 26). In fact, administration of purified CPC with sterile cecal contents was found to potentiate abscess formation (25). This effect was specific to the B. fragilis CPC;IP implantation of either the capsule from Escherichia coli or heat-killed S. pneumoniae did not induce abscess formation (25).

B. fragilis can produce at least eight structurally distinct capsular polysaccharides (denoted as polysaccharides A–H), of which polysaccharide A (PSA) is the most abundantly expressed (27). Individual polysaccharides from the CPC have been tested for their ability to induce intra-abdominal abscesses, and purified PSA is an order of magnitude more active in this regard than the complete CPC or polysaccharide B (PSB) (28). In addition to possessing abscess-inducing properties, B. fragilis CPC is essential for bacterial growth: mutants unable to produce at least one of the eight capsular polysaccharides exhibit severe growth attenuation (29). Moreover, mutant B. fragilis organisms expressing only a single capsular polysaccharide – polysaccharide C – cannot compete effectively with wild-type organisms in intestinal colonization of GF mice (29). The recent recognition that other Bacteroides species also possess the genetic capacity to produce multiple capsular polysaccharides suggests that surface diversity is important for these commensal organisms (30).

Although IP administration of B. fragilis CPC along with sterile cecal contents induces abscess formation, pretreatment of animals with purified CPC (without sterile cecal contents as an adjuvant) protected animals from abscess formation after challenge with B. fragilis or even with other encapsulated organisms typically found in the intestinal flora (31). These results suggested that B. fragilis CPC might be clinically useful as a vaccine against IP infections. However, transfer of serum antibodies from rats immunized with B. fragilis CPC to naive rats was not sufficient to confer protection against intra-abdominal abscess formation; thus humoral immunity is not involved (32). In further studies of the mechanism underlying CPC-mediated protection from abscess formation, transfer of splenocytes from rodents immunized with B. fragilis CPC to unimmunized animals provided protection against the development of abscesses, highlighting the critical role played by cellular immunity (32, 33). Additional experiments clarified that this protection can be mediated by transfer of CD4+ αβ T-cell receptor (αβTCR) T cells alone (32–34); the mechanism underlying this effect requires T-cell expression of a low-molecular-weight soluble factor ultimately identified as interleukin-10 (IL-10) (35, 36). These findings led to the proposal in 1982 that B. fragilis CPC induces the activity of a ‘suppressor T cell’, which only recently has been recognized to be the inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T cell (33, 37).

Structure of B. fragilis CPC

The distinctive ability of B. fragilis CPC to activate T cells and potentiate abscess formation was clarified through the elucidation of its structure. Initial chemical analysis demonstrated that PSA and PSB, the two dominant components of the B. fragilis CPC, consist of several hundred repeating units of an oligosaccharide that contains unusual constituent sugars (38–40). Moreover, PSA and PSB have free carboxyl, phosphate, and amino groups—structural characteristics resulting in a unique combination of positive and negative charges within each repeating unit (38). This zwitterionic nature is quite remarkable since most bacterial polysaccharides do not contain positively charged groups. Subsequent investigations demonstrated that this alternating arrangement of positive and negative charges forms the structural basis for the protective effects observed with PSA and PSB (28). Specifically, chemical neutralization of either charged motif eliminates the ability of zwitterionic polysaccharides (ZPSs) to protect against development of intra-abdominal abscesses (28, 41, 42). Moreover, this zwitterionic motif is required for ZPS-induced T-cell stimulation (43, 44). In addition, the protective effects of PSA are size-dependent. Native PSA has a molecular weight of ~130 kDa; a 5.0-kDa fragment (~6 repeating units) conferred no protection in a rat model of intra-abdominal abscesses, while a 17.1-kDa fragment (~22 repeating units) functioned similarly to native PSA (45).

Delineation of the three-dimensional structure of PSA2 – highly related to PSA but expressed by a different B. fragilis isolate – revealed a right-handed helix with two repeating units per turn and a pitch of 20 Å (46). Both positively and negatively charged groups line the external surface of the helix, potentially making them available for interactions with other molecules. This helical conformation is required for the functionality of ZPSs; PSA fragments of <3repeating units and chemically neutralized PSA (which lacks the zwitterionic motif) lack a helical conformation, as measured by circular dichroism, and are nonfunctional (47).

ZPSs are T-cell–dependent carbohydrates

Carbohydrates have classically been thought of as T-cell–independent antigens (48). In vaccinology, investigators have circumvented this limitation with the use of glycoconjugate vaccines, in which T-cell help is enlisted by conjugation of polysaccharides to carrier proteins (49); examples include the glycoconjugate vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae type b, Neisseria meningitidis, and S. pneumoniae. However, a few carbohydrate-based vaccines, such as the 23-valent S. pneumoniae vaccine, do not require protein conjugation to induce protective levels of IgG antibody in adult patients. The implication of this observation is that some T-cell help must be involved in this process (50). No immunologic model has existed to describe how pure polysaccharides without a carrier protein could generate T-cell–dependent immune responses. The finding that ZPSs can directly activate T cells suggested a possible experimental model in which to address carbohydrate/T-cell interactions. Similar to T-cell activation by peptide antigens, that by ZPSs requires a physical interaction of the antigen-presenting cell (APC) with the T cell, endosomal acidification, and class II major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) binding directly to the polysaccharide (51). After entry into the APC, ZPS molecules undergo deamination and are processed to low-molecular-weight polysaccharides via this nitric oxide–mediated mechanism (52, 53). In a process analogous to APC presentation of peptides, the processed polysaccharide traffics through the endocytic pathway, is loaded onto MHCII in a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DM-dependent manner, and is presented (as determined by confocal microscopy) at the interface between the APC and the T cell (52).

One notable difference between APC presentation of peptides and that of ZPSs is that N-linked glycosylation of MHCII is required for ZPS presentation (54). Previous studies had demonstrated that these N-linked glycans did not participate in peptide binding or presentation (55, 56); instead, these glycans had been thought to protect MHCII from proteolysis, to regulate spatial organization of molecules within the immune synapse, and to serve as a checkpoint before trafficking to the cell surface (57–59). Experiments using chemical inhibitors of MHCII glycosylation by eukaryotic cells and analysis of MHCII expressed by bacteria (which are unable to perform complex glycosylation of proteins) indicated a significant reduction of PSA binding to MHCII; these same assays demonstrated no negative impact on peptide binding and presentation via MHCII (54). Given that glycosylation patterns can vary with the cell type and state of inflammation (60, 61), it is possible that ZPS activation of T cells can similarly be differentially regulated.

ZPSs are present in multiple commensal bacteria

Although PSA is the best-characterized ZPS, a number of surface polysaccharides from other commensal organisms share this unique structure. For example, the species-specific polysaccharide C-substance and type-specific type I polysaccharide (Sp1) from S. pneumoniae, the capsular polysaccharides from S. aureus types 5 and 8, the cell-wall teichoic acid from a number of S. aureus strains, and the O-chain antigen from Morganella morganii all possess a zwitterionic motif (62–67). These other commensal ZPSs have also been shown to have an α-helical structure (68), to be presented via the MHCII pathway (65, 69, 70), and to activate CD4+ T cells (64, 65, 69). Several of these ZPSs were found to potentiate abscess formation in rodent models of intra-abdominal abscess (28, 64, 71). Taken together, these data support the idea that all of these structure–function relationships of ZPSs are related to the zwitterionic motif rather than to the specific charged moieties or polysaccharides present in these diverse molecules. Recent advances in chemical synthesis of polysaccharides have allowed the generation of a dimeric repeating unit of Sp1 and a monomeric unit of PSA (72,73). Prior work suggests that these current synthesized polysaccharides have too few repeating units to be functional; however, continued work in this area may ultimately yield synthetically derived, functional ZPSs that will be instrumental in further elucidating the mechanism of action of these unusual polysaccharides.

The yang: bacterial polysaccharides as immunoregulatory agents

Nexus between PSA and ontogeny of the immune system

It has been known since the 1930s that commensal organisms are vital to development of the immune system (74, 75). Specifically, GF animals have smaller splenic lymphoid follicles, fewer splenic CD4+ T cells, smaller Peyer’s patches, and fewer intestinal lymphocytes than conventionally raised animals with the normal complement of commensal organisms; these abnormalities are corrected by colonization with a normal flora (11, 74, 76). Moreover, the immune response of GF animals is T-helper 2(Th2)-skewed compared with that of conventional animals (77). It has been speculated that one or more specific microorganisms are critical in directing the maturation process, although the identity of the organism(s) was unknown (78). Given the unique structure of ZPSs, their ability to activate the immune system, and their presence in a diverse array of commensal organisms, we hypothesized that these molecules may play a critical role in the ontogeny of the immune system.

To test this hypothesis, we measured a variety of immunologic parameters in previously GF mice colonized with B. fragilis (79). Astonishingly, monocolonization of mice with B. fragilis proved sufficient to induce maturation of splenic CD4+ T cells, increasing cell numbers to those found in specific pathogen–free (SPF) mice. This was the first demonstration of a specific, single bacterium’s ability to correct systemic immune defects in GF mice. In contrast, mice monocolonized with mutant B. fragilis deficient in PSA expression (B. fragilis ΔPSA) had splenic CD4+ T-cell levels indistinguishable from those in GF mice (79). Moreover, IP injection of PSA into GF mice led to a correction of splenic CD4+ T-cell numbers, a result demonstrating that PSA can function in the absence of the whole bacterium. Furthermore, oral administration of PSA to SPF mice induced an increase in CD4+ T-cell frequencies, an outcome indicating that PSA can affect the immune system even in the presence of a normal microbiota. CD8+ T cells and CD19+ B cells, the frequencies of which do not differ between GF and SPF animals, were not affected by PSA treatment (79). PSA not only increased the numbers of splenic CD4+ T cells but also affected their cytokine production (79). Similar to SPF animals, mice monocolonized with wildtype B. fragilis had a more balanced Th1–Th2 response that contrasted with the Th2 skew observed in GF mice and in mice colonized with B. fragilis ΔPSA. Taken together, these data demonstrate that a single bacterial polysaccharide – PSA – is sufficient to induce normal maturation of the systemic immunity. Notably, PSA remains the only example identified thus far of a specific commensal-derived molecular factor that mediates development of the mammalian immune system.

Identification of other immunomodulatory commensal organisms

Although the tremendous impact of the microbiota on the ontogeny of the immune system has long been known, this field has been slow to emerge given the complexities involved in its study. However, the increasing availability of GF and gnotobiotic facilities, the advent of high-throughput sequencing modalities, and improved techniques for studying the mucosal immune system now promise great advances in this field. Since the identification of B. fragilis as an immunogenic commensal organism, three additional examples of such organisms have been reported. Two groups independently identified segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), unculturable Clostridium-related organisms, as critical for induction of Th17 cells in the small-intestinal lamina propria of mice (80, 81). This induction of Th17 cells was important in protection against oral infection with Citrobacter rodentium (81). More recently, investigators identified a group of 46 Clostridium species that induce regulatory T cells in the colonic lamina propria, providing protection from colitis and systemic IgE responses (82). However, these investigators were unable to narrow down the effects to any particular organism in the group (82). Another commensal organism with immunomodulatory properties is Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which is underrepresented in the ileal microbiota of patients with postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease as compared to postoperative patients in remission (83). This correlative evidence was supported by the in vitro and in vivo demonstration of this organism’s anti-inflammatory properties and ability to protect against trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)–induced colitis in mice. On the basis of bacterial fractionation studies, this immunomodulatory property of F. prausnitzii was localized to the culture supernatant—a site indicating that the unidentified compound is freely secreted (83). Given that the intestinal microbiome includes more than 1000 species in total, these isolated examples of immunomodulatory commensal organisms are likely to represent the tip of the iceberg. Endeavors such as the Human Microbiome Project should greatly expand our knowledge of the influence of commensal organisms on human immunity (84).

Mechanism underlying microbe-induced maturation of the immune system Although our group and others have begun to identify bacteria with immunomodulatory potential, the mechanism(s) by which these bacteria mediate development of the immune system have yet to be elucidated. Many steps are probably involved in this process, including host recognition of the bacteria, transfer of immunogenic signals from the intestinal lumen to the lamina propria, proliferation of lymphocytes, and proper trafficking of lymphocytes. Much work has focused on the role of pattern recognition receptors in the recognition of bacteria, and intestinal expression of these receptors is known to be involved in intestinal homeostasis and control of immune-mediated diseases (15, 85). However, one analysis of the small-intestinal immune system in mice deficient in MyD88, an adapter protein for virtually all the Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways, detected decreases only in numbers of CD8αα αβTCR and γδTCR intraepithelial lymphocytes; this result suggested that the MyD88-dependent pathway plays only a minor role in homeostasis of the mucosal immune system(86). In line with this report, studies on induction of intestinal Th17 cells revealed that this process is independent of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF), and receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2)—adapters for TLR and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) proteins (87, 88); similarly, clostridial stimulation of regulatory T cells is independent of MyD88, RIP2, and CARD9 – adapters for the TLR, NOD, and dectin pathways (82). Nothing is currently known about the mechanism through which F. prausnitzii affects the host immune response.

A great deal of progress has been made in understanding the step-wise mechanism through which B. fragilis PSA interacts with and influences the host immune system. B. fragilis binds to intestinal mucins and resides within colonic crypts of monocolonized animals (89, 90). This juxtaposition of B. fragilis with the intestinal epithelium may partly explain how PSA interfaces with the host immune system. As noted above, in vitro experiments demonstrated that APCs are capable of presenting PSA via MHCII (51, 52). Examination of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) from GF mice fed fluorescently labeled PSA revealed that PSA specifically associates with CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs) (79). Fluorescently labeled PSA was never recovered from the spleen, indicating that DCs sample intestinal antigens (e.g. PSA) and migrate to local lymph nodes, where they stimulate T cells (79). These findings are in accord with the observation that commensal-loaded DCs are restricted to the mucosal immune compartment and do not reach systemic lymphoid organs (91).

After engulfing PSA, DCs secrete the proinflammatory cytokines IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) through a TLR2-dependent mechanism (79, 92). Moreover, PSA-induced production of cytokines [e.g. interferon-γ (IFN-γ)] by CD4+ T cells requires TLR2 expression by DCs, and TLR2−/−mice have less capacity for PSA-induced abscess formation than do wildtype mice (92). Taken together, these data demonstrate that PSA can link innate and adaptive immune responses via interactions with DC-expressed TLR2.

PSA directs anti-inflammatory responses

As described above, PSA affects CD4+ T-cell frequencies and alters the cytokine profiles of these cells; however, it has been unclear whether PSA induces a specific T-cell subset. By CD45Rb staining, CD4+ T cells can be classified as naive (CD4+CD45Rbhigh) or antigen-experienced (CD4+CD45Rblow) (93). Comparison of GF, SPF, B. fragilis–monocolonized, and B. fragilis ΔPSA–monocolonized mice revealed that B. fragilis – in a PSA-specific manner – expands the antigen-experienced CD4+CD45Rblow T-cell population to levels found in SPF animals (94). Notably, CD4+CD45Rblow T cells are known to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties and can confer protection in experimental models of inflammation (95). In the CD4+CD45Rb transfer model of colitis (96), oral administration of either a PSA-sufficient strain of B. fragilis or purified PSA protected animals from colitis (94). To evaluate the robustness of this finding, a second experimental model of colitis using TNBS was employed (97). Again, oral administration of PSA, either before or after onset of inflammation (i.e. prophylactically or therapeutically), protected mice against the chemical induction of colitis (37, 94). Thus, PSA not only can direct maturation of the host immune system but also can coordinate the immune response to inflammatory processes.

A series of in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that PSA-mediated protection from experimental colitis is due to stimulation of IL-10 production (94). Moreover, B. fragilis monocolonization leads to an increase in colonic IL-10 levels even in the absence of inflammation (37). B. fragilis PSA induces IL-10-producing CD4+Foxp3+ (forkhead box p3) regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the MLNs in a TLR2-dependent manner (37). Accordingly, PSA is unable to protect TLR2−/− animals from experimental colitis (37). The ZPS Sp1 was found to induce immunosuppressive, IL-10-producing CD8+CD28− T cells (98), which prevent colitis in the CD4+CD45Rb transfer model (99). This finding raises the possibility that ZPS molecules may possess multiple mechanisms for stimulating anti-inflammatory responses.

PSA establishes symbiosis

The intestinal tract harbors more microorganisms than any other site in the human body. While pathogenic enteric organisms typically elicit an inflammatory response (e.g. IL-17, IL-6, and IL-8) leading to their elimination, commensal organisms can peacefully co-exist with the intestinal immune system. The finding that B. fragilis expression of PSA engenders an anti-inflammatory milieu in the intestine raised the possibility that this same process may be critical for the establishment of a commensal intestinal flora. Monocolonization experiments indicated that B. fragilis ΔPSA could not colonize the colonic epithelium as effectively as wildtype B. fragilis (90). While this difference in colonization levels may suggest that PSA serves as an adherence factor for B. fragilis, it may also reflect the immunomodulatory properties of PSA. In an investigation of the latter possibility, the intestinal cytokine response to monocolonization with either wildtype B. fragilis or B. fragilis ΔPSA was measured (90). Intriguingly, only mice monocolonized with B. fragilis ΔPSA developed significantly increased Th17 responses within the colon and MLNs, and there was no difference between these two groups of mice with respect to Th1 responses. Given that PSA is known to promote the production of colonic Tregs, it was hypothesized that the increased number of Tregs restricted the TH17 response. Specific ablation of Foxp3+ Tregs in mice monocolonized with B. fragilis resulted in an increase in Th17 cells, a result demonstrating that B. fragilis restrains the formation of proinflammatory cells via induction of suppressive Tregs (90).

Further in vitro experiments suggested that PSA stimulates IL-10 production through a TLR2-mediated pathway involving only T cells; APCs were not required regardless of TLR2 expression (90). Surprisingly, other known TLR2 ligands (e.g. Pam2CysK and Pam3CysK) did not stimulate IL-10 production in this assay (90). Although PSA relies on DC-expressed TLR2 for T-cell production of IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, it appears that PSA-stimulated IL-10 production may be unique in its APC independence (79, 90, 92); further exploration into this dichotomy is needed. Moreover, the in vivo relevance of direct PSA/T-cell interactions remains to be identified. In particular, it is currently unclear how T cells in the colonic lamina propria interact with a luminal antigen without help from APCs. B. fragilis monocolonization of Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+ T cells from wildtype or Tlr2−/− mice demonstrated that IL-10-producing Foxp3+ T cells were generated only in the TLR2-sufficient mice (90). These data again demonstrate the absolute requirement for T cell–expressed TLR2; however, it is unclear whether these findings reflect a direct interaction of PSA with T cells since DCs are present in Rag1−/− mice. Ultimately, the ability of B. fragilis to colonize the intestine is a consequence of PSA induction of IL-10-producing Foxp3+ T cells, which antagonize and restrain the proinflammatory Th17 response.

Extraintestinal effects of PSA

As detailed above, PSA has profound effects on shaping the immune system within both the intestinal and the systemic compartments. It is increasingly recognized that the commensal flora may also affect systems far removed from the intestine (e.g. the central nervous system). A number of epidemiologic studies, with some support from animal studies, suggest that microorganisms may have some relation to neurodevelopmental disorders (100–103). As more is learned about the nexus between commensal organisms and the immune system, increasing links to systemic diseases are being found. For example, the presence of intestinal SFB has been found to potentiate the development of arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) in mouse models (16, 104); however, the presence of SFB also protects female NOD mice from type 1 diabetes (105). Oddly, then, the same commensal organism both augments and suppresses autoimmune diseases, with the nature of the effect dependent on the specific disease.

The effects of PSA on extraintestinal immune responses were investigated in a mouse model of EAE, the most widely used experimental model in studies of multiple sclerosis (106). Earlier work using antibiotic disruption of the microbiota demonstrated the role of commensal organisms in modulating clinical outcome in the EAE model (107, 108). Antibiotic treatment was associated with an increase in IL-10-producing CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in the cervical and mesenteric lymph nodes, with consequent protection from disease in adoptive transfer experiments (107). Given this role of commensal flora in modulating disease severity and the critical nature of IL-10-producing Tregs in mediating protection from disease, it was reasoned that PSA might exert protective effects in the EAE model. Indeed, pretreatment of animals with either wildtype B. fragilis or purified PSA prior to induction of disease conferred protection from clinical manifestations (109, 110). Moreover, therapeutic administration of PSA after disease induction reduced the severity of EAE (110). Similar to findings in the colitis model, regulation of EAE by PSA involved enhancement of IL-10-producing CD4+Foxp3+ T cells (109, 110). Notably, this induction of Tregs was observed in the cervical lymph nodes even though PSA was administered orally (110). Moreover, CD11chighCD103+ DCs, which are typically restricted to the mucosa, accumulated in the cervical lymph nodes of mice with induced EAE that were exposed to PSA (110). This accumulation occurred only in the setting of inflammation; mice without induced EAE that were given PSA had no such increase. This dependence on an inflammatory stimulus is not yet fully understood, but changes in vascular permeability, chemokine levels, or the cytokine milieu may be involved. In summary, these data indicate that PSA can both prophylactically and therapeutically restrain inflammatory processes in extraintestinal locations in a process that involves the homing of mucosal DCs to distant sites of inflammation.

Reconciling the yin yang of PSA

At first glance, it may not be readily apparent how or why a single molecule, B. fragilis PSA, can stimulate both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses (e.g. abscesses and IL-10-producing Tregs, respectively). Determination of the specific anatomic location in which B. fragilis encounters the immune system may resolve these issues in part (Fig. 1). In the normal, healthy host, B. fragilis is localized exclusively in the intestinal tract. To establish and maintain colonization, the organism must subvert the immune response, which it does through induction of Tregs and suppression of Th17 responses (90). The symbiotic consequence of this colonization is that the host is better able to respond to inflammatory processes both within and outside of the gastrointestinal system (94, 109). If, however, intestinal integrity is breached (e.g. by surgery or penetrating trauma), many different bacterial organisms, including B. fragilis, enter the peritoneal cavity and result in peritonitis. If the host lacks the ability to confine and eliminate these intestinal organisms, potentially fatal sepsis may result, affecting the host’s well-being and disrupting the intricate ecosystem of the microbiota. At the risk of anthropomorphizing B. fragilis, it could be argued that it is in the organism’s interest to help the host stave off severe illness so that its ecological niche will return to a state of normalcy. In this process, some B. fragilis organisms will be contained and killed as a result of abscess formation. The idea that a few bacteria ‘commit suicide for the greater good’ is analogous to the concept of bacterial programmed cell death, in which individual bacteria are eliminated to protect the entire bacterial community from phage infections and periods of nutrient scarcity (111, 112). Thus, while abscess formation indicates a preceding adverse event, the abscess itself can be viewed as evidence of a ‘successful’ joint venture by the host and its flora. Similar, then, to its role in engendering a homeostatic anti-inflammatory milieu, PSA-mediated abscess formation can also be seen as a means of dampening the host immune response and protecting it from an inflammatory process.

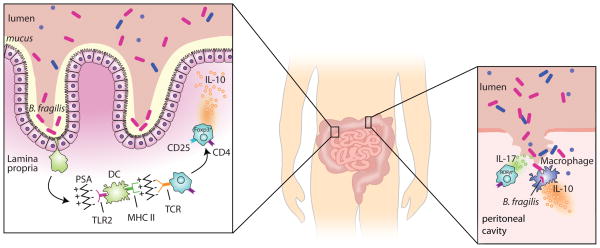

Fig. 1. Immunomodulatory effects of B. fragilis.

The small and large intestines are illustrated. The inset on the left depicts the normal, healthy state with the majority of the microbiota residing in the intestinal lumen and B. fragilis adhering to the mucus layer. Dendritic cells (DCs) sample the luminal content. B. fragilis PSA interacts with TLR2 on DCs and is ultimately presented on the DC surface by MHCII. Naive CD4+ T cells recognize MHCII-presented PSA via their T-cell receptor (TCR) and differentiate into IL-10–producing CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. The inset on the right depicts a breach of the intestinal barrier (e.g. following surgery or penetrating trauma). Many different bacteria, including B. fragilis, spill into the peritoneal cavity. Th17 cells secrete IL-17 which is essential for abscess formation. Macrophages interact with B. fragilis and secrete IL-10, which is necessary for disease containment.

Although abscess formation requires Th17 cells (34), B. fragilis–induced IL-10 production is critical for restraining proinflammatory cytokine responses and for containing disease (113). In a murine model of intra-abdominal abscess formation, IL-10−/− mice had a similar degree of bacteremia as wildtype animals but had significantly increased mortality and metastatic disease involving the pleura and pericardium (113). In contrast to the mechanism underlying symbiosis, the systemic IL-10 response during abscess formation is independent of T cells and produced largely by peritoneal macrophages, with only partial dependence on TLR2 (113). Thus, the symbiotic and ‘pathogenic’ aspects of B. fragilis both involve stimulation of IL-10 with restraint of IL-17, though the mechanistic steps differ slightly in these processes.

Translating these findings from bench to bedside

A vast number of current pharmaceuticals are based on natural products, and many of the molecules found in screening libraries and used in combinatorial chemistry exploit natural products as their foundation (114–116). As more is learned about the intricate relationship between commensal organisms and the host immune system, it is likely that a large number of commensal-derived immunomodulatory molecules with clinical relevance will be identified. With the hygiene hypothesis as a directive, attempts have been made—with varying degrees of success—to use exogenous administration of commensal organisms (i.e. probiotics) to the benefit of the patient in a variety of clinical settings (117–122). The mixed results from these studies are probably related to two factors: (i) lack of knowledge about the specific impact of a given probiotic on the immune system and (ii) differences in the bacterial strains tested, dosages used, and underlying clinical indications. A primary factor limiting the clinical use of probiotics remains lack of information on which strain may be effective for the condition of interest. Moreover, no study on probiotics has offered a mechanistic explanation for the effectiveness of a particular bacterial strain. Use of whole organisms (even organisms typically found in the intestinal flora) as probiotics is occasionally associated with disease; thus attempts to alter the bowel flora must be undertaken with caution (123, 124). Additional insights into the interplay of the microbiota and the host immune system, with particular attention to the mechanism by which microbes effect immunologic changes, are likely to improve the clinical utility of probiotics in the future and may permit the use of specific bacterial factors instead of whole organisms.

The use of whole organisms as probiotics may be complicated by their interactions with the preexistent autochthonous flora. As discussed earlier, the microbiota serves to protect the host from external microorganisms. This concept of ‘colonization resistance’, first discussed in 1971, was initially applied in attempts to re-colonize antibiotic-treated animals with components of their normal flora (125), but it is also applicable to attempts to alter the intestinal microbiota by exogenous administration of organisms. For example, oral or rectal administration of B. fragilis to SPF mice otherwise lacking B. fragilis does not result in sustained colonization (S. Dasgupta and D. L. Kasper, unpublished observations). Moreover, oral probiotics typically alter the human microbiota only transiently, even with ingestion of upwards of 108 cfu per day (126); even after more severe perturbations (e.g. in the course of antibiotic therapy), the flora largely normalizes with time (127). Furthermore, some organisms, such as SFB, exhibit intricate host specificity, so that rat SFB cannot colonize a mouse (and vice versa) in the context of a complex flora (128). Thus, clinical application of probiotics will require the resolution of issues related to colonization resistance and interspecies colonization.

Studies on probiotics raise the larger question of whether it makes sense to search for immunomodulatory molecules in ubiquitous commensals. The hygiene hypothesis asserts that changes in immunologic responses are due to a lack of exposure to microorganisms (19), suggesting that commensals that are commonly present in the microbiota may not be as relevant as exogenous organisms. There is increasing evidence, however, that the exact composition of the human microbiota varies with diet, geography, and environmental exposures (18, 129, 130). Although the gut microbiota can be classified into three general enterotypes at the community level, only 18 of the more than 1000 different bacterial species that have been identified in the human fecal microbiota appear to be common to all people (131, 132). It is likely, then, that not all people benefit from specific immunomodulatory organisms (e.g., B. fragilis) because they are not colonized with the organism in question. Moreover, it is unclear whether some threshold level of the immunogenic organism or its relevant molecule is required; if so, even people who are colonized may not benefit because of a low bacterial abundance. Finally, the microbiome maybe altered in diseased states, reducing the abundance of immunostimulatory organisms (e.g. F. prausnitzii in Crohn’s disease) (83). Accordingly, a great deal of information can likely be obtained by studying interactions of our commensal flora with our immune system, and this information may ultimately yield clinical benefits.

In some sense, the success of glatiramer acetate (marketed as Copaxone® by Teva Pharmaceuticals) may offer a proof of concept of the clinical utility of commensal-derived molecules, such as ZPSs. Glatiramer acetate is one of two first-line treatments for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis, generating annual revenues in excess of $2 billion (133). Structurally, it consists of a huge number of random polymers that vary in sequence but have defined stoichiometric ratios of four amino acids: glutamic acid, lysine, alanine, and tyrosine. This charge motif bears a striking resemblance to that of ZPSs with positively and negatively charged moieties; the primary difference is that glatiramer acetate is a peptide rather than a polysaccharide. Although the exact mechanism of action remains unknown, glatiramer acetate induction of IL-10-producing Tregs is known to be crucial for its clinical benefits (133–135). Moreover, glatiramer acetate is therapeutic in multiple murine models of colitis (136, 137). These findings mirror those obtained for PSA, i.e. the induction of IL-10-producing CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and efficacy in murine models of colitis and multiple sclerosis, and suggest that PSA may have effects similar to those of glatiramer acetate in humans. Along these lines, PSA is ~10–100 times more active than glatiramer acetate in terms of in vitro cytokine production (unpublished observations). It will be of great interest to test PSA in clinical trials against multiple sclerosis or inflammatory bowel disease.

In addition to their potential usefulness as immunomodulators in inflammatory conditions, ZPSs may also prove valuable in enhancing the immunogenicity of vaccines. Vaccines represent one of the greatest public health successes of the last century, offering antibody-mediated protection from a variety of infectious diseases (138–140). However, carbohydrate-based vaccine antigens are typically poorly immunogenic (48), and the incorporation of ZPS-like moieties may prove useful. In fact, the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine (marketed as Pneumovax® by Merck) utilizes a known ZPS, Sp1, as one of its constituents (141). It is possible that the immunogenicity of this vaccine, one of the few carbohydrate-based vaccines used clinically, is related to the incorporation of Sp1. Augmenting bacterial carbohydrates to artificially include ZPS moieties and fusing antigens to known ZPS compounds have been demonstrated to enhance the immunogenicity and potency of vaccines both in vitro and in animal studies (142–144). Moreover, in a number of conditions (infectious and otherwise), neutralizing antibodies do not offer adequate protection, and the potential advantage of strengthening mechanisms of cellular immunity has intensified interest in improving T-cell–inducing vaccines (145–148). The ability of ZPSs to stimulate T cells may represent a novel mechanism for enhancement of the host immune response and consequent reductions in morbidity and mortality (149, 150).

It is important to note that the vast majority of studies evaluating the immunogenic effects of commensal organisms have thus far been conducted in animals. One reason is that human-based studies would, at best, permit only correlations because of our inability to manipulate the microbial environment in a controlled manner. However, there are clearly numerous immunologic differences between mice and humans (151), and it remains to be seen whether lessons learned from commensal-host interactions in the mouse can be translated to humans. One known difference involves SFB; although these bacteria have clear and dramatic effects on the intestinal immune system in rodents and are present in a variety of vertebrates (80, 81, 152), only scant evidence suggests the presence of SFB-like organisms in humans, and the prevailing assumption is that humans do not harbor such organisms (152–155). Given that humans do have intestinal Th17 cells (156), they probably harbor some still-unidentified organisms that are equivalent to SFB in terms of immunogenic function. PSA induction of Tregs illustrates another distinction between murine and human studies. Although PSA induces CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in mice (37), PSA treatment of peripherally isolated naive CD4+ T cells from humans is reported to cause differentiation of predominantly CD4+CD25+Foxp3− T cells, an induced T-regulatory type 1 cell (Tr1) (157). Moreover, these PSA-induced Tr1 cells express IL-10 but not transforming growth factor β, while the PSA-differentiated murine Tregs express both cytokines (37, 110, 157). Thus, even though animal studies permit greater experimental manipulation and investigation into mechanisms of microbe-induced immunologic changes, these two examples underscore the importance of ultimately confirming results obtained in animals with human samples.

Concluding thoughts

The 20th century saw incredible advances in our understanding of host–microbe interactions, with identification of numerous disease-associated organisms and elucidation of pathogenic mechanisms. However, the vast majority of this work was directed at purging the human body of pathogenic organisms (158). The discovery of antibiotics, the development of vaccines, and improvements in public sanitation led to a remarkable decrease in the incidence of infectious diseases, the successful elimination of scourges like smallpox, and the near-elimination of polio (159, 160). In terms of bacterial disease, vaccines have almost eradicated invasive disease related to H. influenzae type b and the vaccine serotypes of S. pneumoniae (161–163). While all of these efforts have dramatically reduced morbidity and mortality related to infections, they may also have inadvertently rid us of needed immunomodulatory molecules. Researchers have spent more than 100 years studying pathogens with the aim of their eventual elimination, with little regard for what happens in their absence; it is now clear that many ‘pathogens’ more commonly exist as commensal organisms (3). During the 21st century, we need to expand our understanding of commensalism and of how these pathogenic organisms may actually be vital to our well-being.

Over the past several decades, our laboratory has demonstrated that ZPS molecules, which are present in a wide variety of commensal organisms and of which PSA is the archetype, are sufficient for maturation of the immune system and engender an anti-inflammatory milieu that protects the host from a variety of insults. These studies constitute a critical first step toward a better understanding of host–microbe interactions and their role in the development of the host immune system. In the coming years and decades, we expect exponential progress in this field, much like that made in the work on pathogenic organisms during the last century. Ultimately, we hope to harness our improved knowledge of commensals and to use immunomodulatory bacterial factors as adjunctive clinical therapies. Ironically, we must now attempt to replicate the effects of microorganisms that we have spent a century trying to eliminate from the human body. Our work with PSA indicates that we may ultimately be successful in this endeavor.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie B. McCoy for editorial assistance. N.K.S is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant F32 AI091104. Work in D.L.K.’s laboratory is supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Senior Research Award, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, NIH/NIAID R21 AI090102, and NIH/NIAID R01 AI089915. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Koch R. Untersuchungen über Bakterien: V. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschicte des Bacillus anthracis. Cohns Beitrage zur Biologie der Pflanzen. 1876;2:277–310. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendall AI. Some observations on the study of the intestinal bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1909;6:499–507. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isenberg HD. Pathogenicity and virulence: another view. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:40–53. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobzhansky T. Genetics of the Evolutionary Process. New York: Columbia University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckey TD. Introduction to intestinal microecology. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972;25:1292–1294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasteur L. Observations relatives a la Note Precedente d. M. Duclaux. C R Acad Sci III. 1885;100:68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohendy M. Experiences sur la vie sans microbes. Ann inst Pasteur. 1912;26:106–137. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1058709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith K, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. Use of axenic animals in studying the adaptation of mammals to their commensal intestinal microbiota. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, et al. Commensal bacteria (normal microflora), mucosal immunity and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett. 2004;93:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen L, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. Epub 2008 Sep 1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu HJ, et al. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach JF. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ege MJ, et al. Exposure to environmental microorganisms and childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:701–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehlers S, Kaufmann SH. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: lifestyle changes affecting the host-environment interface. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:10–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ley RE, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science. 2008;320:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.1155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore WE, Holdeman LV. Human fecal flora: the normal flora of 20 Japanese-Hawaiians. Appl Microbiol. 1974;27:961–979. doi: 10.1128/am.27.5.961-979.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG. Anaerobic infections (second of three parts) N Engl J Med. 1974;290:1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197405302902207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polk BF, Kasper DL. Bacteroides fragilis subspecies in clinical isolates. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:569–571. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-5-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL, Cisneros RL, Bartlett JG. The capsular polysaccharide of Bacteroides fragilis as a virulence factor: comparison of the pathogenic potential of encapsulated and unencapsulated strains. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:82–89. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett JG, Onderdonk AB, Louie T, Kasper DL, Gorbach SL. A review. Lessons from an animal model of intra-abdominal sepsis. Arch Surg. 1978;113:853–857. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1978.01370190075013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krinos CM, Coyne MJ, Weinacht KG, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, Comstock LE. Extensive surface diversity of a commensal microorganism by multiple DNA inversions. Nature. 2001;414:555–558. doi: 10.1038/35107092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Rosner B, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. Structural features of polysaccharides that induce intra-abdominal abscesses. Science. 1993;262:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.8211161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu CH, Lee SM, Vanlare JM, Kasper DL, Mazmanian SK. Regulation of surface architecture by symbiotic bacteria mediates host colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3951–3956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709266105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J, et al. Evolution of symbiotic bacteria in the distal human intestine. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasper DL, Onderdonk AB, Crabb J, Bartlett JG. Protective efficacy of immunization with capsular antigen against experimental infection with Bacteroides fragilis. J Infect Dis. 1979;140:724–731. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.5.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onderdonk AB, Markham RB, Zaleznik DF, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. Evidence for T cell-dependent immunity to Bacteroides fragilis in an intraabdominal abscess model. J Clin Invest. 1982;69:9–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shapiro ME, Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL, Finberg RW. Cellular immunity to Bacteroides fragilis capsular polysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1188–1197. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung DR, et al. CD4+ T cells mediate abscess formation in intra-abdominal sepsis by an IL-17-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:1958–1963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz-Perez B, et al. Modulation of surgical fibrosis by microbial zwitterionic polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16753–16758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505688102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaleznik DF, Finberg RW, Shapiro ME, Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL. A soluble suppressor T cell factor protects against experimental intraabdominal abscesses. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1023–1027. doi: 10.1172/JCI111763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumann H, Tzianabos AO, Brisson JR, Kasper DL, Jennings HJ. Structural elucidation of two capsular polysaccharides from one strain of Bacteroides fragilis using high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1992;31:4081–4089. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasper DL, Weintraub A, Lindberg AA, Lonngren J. Capsular polysaccharides and lipopolysaccharides from two Bacteroides fragilis reference strains: chemical and immunochemical characterization. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:991–997. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.991-997.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzianabos AO, Pantosti A, Baumann H, Brisson JR, Jennings HJ, Kasper DL. The capsular polysaccharide of Bacteroides fragilis comprises two ionically linked polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18230–18235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Smith RS, Kasper DL. Structure-function relationships for polysaccharide-induced intra-abdominal abscesses. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3590–3593. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3590-3593.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Zaleznik DF, Smith RS, Kasper DL. Structural characteristics of polysaccharides that induce protection against intra-abdominal abscess formation. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4881–4886. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4881-4886.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brubaker JO, Li Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, Finberg RW. Mitogenic activity of purified capsular polysaccharide A from Bacteroides fragilis: differential stimulatory effect on mouse and rat lymphocytes in vitro. J Immunol. 1999;162:2235–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzianabos AO, et al. T cells activated by zwitterionic molecules prevent abscesses induced by pathogenic bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6733–6740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalka-Moll WM, et al. Effect of molecular size on the ability of zwitterionic polysaccharides to stimulate cellular immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:719–724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Kalka-Moll WM, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL. Structural basis of the abscess-modulating polysaccharide A2 from Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13478–13483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreisman LS, Friedman JH, Neaga A, Cobb BA. Structure and function relations with a T-cell-activating polysaccharide antigen using circular dichroism. Glycobiology. 2007;17:46–55. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avci FY, Kasper DL. How bacterial carbohydrates influence the adaptive immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein Klouwenberg P, Bont L. Neonatal and infantile immune responses to encapsulated bacteria and conjugate vaccines. Clin Dev Immunol. 2008;2008:628963. doi: 10.1155/2008/628963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poolman JT. Pneumococcal vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3:597–604. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalka-Moll WM, Tzianabos AO, Bryant PW, Niemeyer M, Ploegh HL, Kasper DL. Zwitterionic polysaccharides stimulate T cells by MHC class II-dependent interactions. J Immunol. 2002;169:6149–6153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 2004;117:677–687. doi: 10.016/j.cell.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duan J, Avci FY, Kasper DL. Microbial carbohydrate depolymerization by antigen-presenting cells: deamination prior to presentation by the MHCII pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5183–5188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan SO, Bonomo JA, Zhao F, Cobb BA. MHCII glycosylation modulates Bacteroides fragilis carbohydrate antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1041–1053. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frayser M, Sato AK, Xu L, Stern LJ. Empty and peptide-loaded class II major histocompatibility complex proteins produced by expression in Escherichia coli and folding in vitro. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;15:105–114. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Li H, Martin R, Mariuzza RA. Structural basis for the binding of an immunodominant peptide from myelin basic protein in different registers by two HLA-DR2 proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:177–188. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dustin ML, et al. Low affinity interaction of human or rat T cell adhesion molecule CD2 with its ligand aligns adhering membranes to achieve high physiological affinity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30889–30898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trombetta ES, Helenius A. Lectins as chaperones in glycoprotein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wormald MR, Dwek RA. Glycoproteins: glycan presentation and protein-fold stability. Structure. 1999;7:R155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrera C, Espejo R, Reyes VE. Differential glycosylation of MHC class II molecules on gastric epithelial cells: implications in local immune responses. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:384–393. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell BJ, Yu LG, Rhodes JM. Altered glycosylation in inflammatory bowel disease: a possible role in cancer development. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:851–858. doi: 10.1023/a:1022240107040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jennings HJ, Lugowski C, Young NM. Structure of the complex polysaccharide C-substance from Streptococcus pneumoniae type 1. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1980;19:4712–4719. doi: 10.1021/bi00561a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindberg B, Lindqvist B, Lonngren J, Powell DA. Structural studies of the capsular polysaccharide from Streptococcus pneumoniae type 1. Carbohydr Res. 1980;78:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)83664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tzianabos AO, Wang JY, Lee JC. Structural rationale for the modulation of abscess formation by Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9365–9370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Young NM, Kreisman LS, Stupak J, Maclean LL, Cobb BA, Richards JC. Structural characterization and MHCII-dependent immunological properties of the zwitterionic O-chain antigen of Morganella morganii. Glycobiology. 2011 doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baddiley J, Buchanan JG, Rajbhandary UL, Sanderson AR. Teichoic acid from the walls of Staphylococcus aureus H. Structure of the N-acetylglucosaminyl-ribitol residues. Biochem J. 1962;82:439–448. doi: 10.1042/bj0820439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanderson AR, Strominger JL, Nathenson SG. Chemical structure of teichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus, strain Copenhagen. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:3603–3613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi YH, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL, Wang JY. A unique structural pattern shared by T-cell-activating and abscess-regulating zwitterionic polysaccharides. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:15144–15151. doi: 10.1021/bi020491v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Velez CD, Lewis CJ, Kasper DL, Cobb BA. Type I Streptococcus pneumoniae carbohydrate utilizes a nitric oxide and MHC II-dependent pathway for antigen presentation. Immunology. 2009;127:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stephen TL, et al. Transport of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide in MHC Class II tubules. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weidenmaier C, McLoughlin RM, Lee JC. The zwitterionic cell wall teichoic acid of Staphylococcus aureus provokes skin abscesses in mice by a novel CD4+ T-cell-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pragani R, Seeberger PH. Total synthesis of the Bacteroides fragilis zwitterionic polysaccharide A1 repeating unit. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:102–107. doi: 10.1021/ja1087375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu X, Cui L, Lipinski T, Bundle DR. Synthesis of monomeric and dimeric repeating units of the zwitterionic type 1 capsular polysaccharide from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Chemistry. 2010;16:3476–3488. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gordon HA. Morphological and physiological characterization of germfree life. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1959;78:208–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb53104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glimstedt G. Bakterienfreie Meerscheinchen. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1936;30:1–295. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guy-Grand D, Griscelli C, Vassalli P. The mouse gut T lymphocyte, a novel type of T cell. Nature, origin, and traffic in mice in normal and graft-versus-host conditions. J Exp Med. 1978;148:1661–1677. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.6.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sudo N, Sawamura S, Tanaka K, Aiba Y, Kubo C, Koga Y. The requirement of intestinal bacterial flora for the development of an IgE production system fully susceptible to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997;159:1739–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rook GA, Brunet LR. Give us this day our daily germs. Biologist (London) 2002;49:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ivanov II, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atarashi K, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sokol H, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu Q, Tang C, Xun S, Yajima T, Takeda K, Yoshikai Y. MyD88-dependent signaling for IL-15 production plays an important role in maintenance of CD8 alpha alpha TCR alpha beta and TCR gamma delta intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;176:6180–6185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Atarashi K, et al. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature07240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ivanov II, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell host and microbe. 2008;4:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang JY, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. The human commensal Bacteroides fragilis binds intestinal mucin. Anaerobe. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Round JL, et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011;332:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Macpherson AJ, Uhr T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1662–1665. doi: 10.1126/science.1091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Q, et al. A bacterial carbohydrate links innate and adaptive responses through Toll-like receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2853–2863. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bell EB. Function of CD4 T cell subsets in vivo: expression of CD45R isoforms. Semin Immunol. 1992;4:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells suppress systemic and mucosal immune activation to control intestinal inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:256–271. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maloy KJ, Salaun L, Cahill R, Dougan G, Saunders NJ, Powrie F. CD4+CD25+ T(R) cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2003;197:111–119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, Stuber E, Strober W. Antibodies to interleukin 12 abrogate established experimental colitis in mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1281–1290. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mertens J, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 capsular polysaccharide induces CD8CD28 regulatory T lymphocytes by TCR crosslinking. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000596. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Menager-Marcq I, Pomie C, Romagnoli P, van Meerwijk JP. CD8+CD28-regulatory T lymphocytes prevent experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1775–1785. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bilbo SD, Levkoff LH, Mahoney JH, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Neonatal infection induces memory impairments following an immune challenge in adulthood. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:293–301. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Finegold SM, et al. Gastrointestinal microflora studies in late-onset autism. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:S6–S16. doi: 10.1086/341914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Heijtz RD, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Krause D, et al. The association of infectious agents and schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:739–743. doi: 10.3109/15622971003653246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee YK, Menezes JS, Umesaki Y, Mazmanian SK. Proinflammatory T-cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 (Suppl):4615–4622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kriegel MA, Sefik E, Hill JA, Wu HJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11548–11553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mix E, Meyer-Rienecker H, Hartung HP, Zettl UK. Animal models of multiple sclerosis--potentials and limitations. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:386–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ochoa-Reparaz J, et al. Role of gut commensal microflora in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:6041–6050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yokote H, Miyake S, Croxford JL, Oki S, Mizusawa H, Yamamura T. NKT cell-dependent amelioration of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis by altering gut flora. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1714–1723. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ochoa-Reparaz J, et al. Central nervous system demyelinating disease protection by the human commensal Bacteroides fragilis depends on polysaccharide A expression. J Immunol. 2010;185:4101–4108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ochoa-Reparaz J, et al. A polysaccharide from the human commensal Bacteroides fragilis protects against CNS demyelinating disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:487–495. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lewis K. Programmed death in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:503–514. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.503-514.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cohen-Poradosu R, McLoughlin RM, Lee JC, Kasper DL. Bacteroides fragilis-stimulated interleukin-10 contains expanding disease. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:363–371. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Molinski TF, Dalisay DS, Lievens SL, Saludes JP. Drug development from marine natural products. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:69–85. doi: 10.1038/nrd2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Reeves CD. The enzymology of combinatorial biosynthesis. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2003;23:95–147. doi: 10.1080/713609311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Deshpande G, Rao S, Patole S, Bulsara M. Updated meta-analysis of probiotics for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2010;125:921–930. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Arvilommi H, Kero P, Koskinen P, Isolauri E. Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1076–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kligler B, Hanaway P, Cohrssen A. Probiotics in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:949–967. xi. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Thomas DW, Greer FR. Probiotics and prebiotics in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1217–1231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stapleton AE, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1212–1217. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Surawicz CM, Alexander J. Treatment of refractory and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Nature reviews Gastroenterology and hepatology. 2011;8:330–339. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Husni RN, Gordon SM, Washington JA, Longworth DL. Lactobacillus bacteremia and endocarditis: review of 45 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1048–1055. doi: 10.1086/516109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Salminen MK, et al. Lactobacillus bacteremia, clinical significance, and patient outcome, with special focus on probiotic L. rhamnosus GG. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:62–69. doi: 10.1086/380455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.van der Waaij D, Berghuis-de Vries JM, Lekkerkerk L-v. Colonization resistance of the digestive tract in conventional and antibiotic-treated mice. J Hyg (Lond) 1971;69:405–411. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400021653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bezkorovainy A. Probiotics: determinants of survival and growth in the gut. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:399S–405S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.399s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tannock GW, Miller JR, Savage DC. Host specificity of filamentous, segmented microorganisms adherent to the small bowel epithelium in mice and rats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:441–442. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.2.441-442.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.De Filippo C, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:6ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Qin J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Racke MK, Lovett-Racke AE. Glatiramer acetate treatment of multiple sclerosis: an immunological perspective. J Immunol. 2011;186:1887–1890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1090138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hong J, Li N, Zhang X, Zheng B, Zhang JZ. Induction of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by copolymer-I through activation of transcription factor Foxp3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6449–6454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502187102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Miller A, et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with copolymer-1 (Copaxone): implicating mechanisms of Th1 to Th2/Th3 immune-deviation. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;92:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]