Abstract

Summary: High-throughput genotyping arrays provide an efficient way to survey single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome in large numbers of individuals. Downstream analysis of the data, for example in genome-wide association studies (GWAS), often involves statistical models of genotype frequencies across individuals. The complexities of the sample collection process and the potential for errors in the experimental assay can lead to biases and artefacts in an individual's inferred genotypes. Rather than attempting to model these complications, it has become a standard practice to remove individuals whose genome-wide data differ from the sample at large. Here we describe a simple, but robust, statistical algorithm to identify samples with atypical summaries of genome-wide variation. Its use as a semi-automated quality control tool is demonstrated using several summary statistics, selected to identify different potential problems, and it is applied to two different genotyping platforms and sample collections.

Availability: The algorithm is written in R and is freely available at www.well.ox.ac.uk/chris-spencer

Contact: chris.spencer@well.ox.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advent of new technologies, which can simultaneously genotype hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome, has permitted large-scale studies of human genetic variation. A major application of these technologies is to undertake genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify SNPs that correlate with phenotypes such as disease. An important step in providing convincing evidence of association is to argue that the observed correlation is not an artefact of either the sampling strategy (for example, hidden population structure) or systematic biases in inferring genotypes (for example, differences in call rates). In doing so, it has become standard practice to calculate summaries of genome-wide variation that are not expected to vary systematically between study individuals, and then to identify and remove outlying individuals.

Under the correct statistical model, losing data (that is collected at some expense) nearly always results in reduced statistical power to detect real effects. However, when the model fails to capture the data generating process, inclusion of outlying individuals often leads to an increase in false positives. Exclusion of individuals prior to analysis is a trade-off between loss of power due to reduced sample size, and the benefit of controlling the number of false positives.

The typical approach to identify potentially problematic samples is to calculate summary statistics of genome-wide data and then, by visualizing their distributions across individuals, to manually choose a threshold based on their values for the majority of the data. To automate this process requires an algorithm to infer the distribution of ‘normal’ study individuals, therefore allowing inference of outliers. For the approach to be applicable in many settings (different summary statistics, genotyping platforms and sample collections) requires a robust model for the outlying individuals.

2 METHODS

Inference of outliers

We implemented a simple mixture model to identify individuals with atypical genome-wide patterns of diversity as measured by m summary statistics of their genotypes or SNP assay intensities data X; S1(Xi),…, Sm(Xi)(i=1,…, n with n the number of individuals). To do so, we assume each individual is either ‘normal’ or an ‘outlier’, which we index by Zi∈{0, 1}, and use a Bayesian approach to infer the posterior probability of each individual's membership to the two classes. As summary statistics are averages of many (typically over 500,000) SNPs or assays, the central limit theorem should apply to these statistics across individuals. We consider the distribution of the m summary statistics to be sufficiently well described by independent Gaussian distributions in both the normal and outlier class so that

Having observed the summary statistics, our knowledge of which individuals are outliers is given by the posterior distribution

where P(Z, μ, σ2) is the prior distribution. Integrals of this form arise commonly in Bayesian statistics, and it is often not possible to compute them directly. However, there are efficient Monte Carlo methods to sample from the distribution of the unobserved labels Z and the model parameters, μ and σ2, conditional on the observed data S(X):

We used Gibbs sampling to obtain T samples from this joint posterior distribution. The posterior probability of the i-th individual being an outlier is then estimated as

where Zi(t) is the class membership of the i-th individual for the sample t and I is the indicator function. An individual is then considered as an outlier if its estimated posterior probability of being an outlier is >50%.

This approach easily generalizes to correlated summary statistics. Here we consider only two summary statistics jointly, but the model could be extended to more. Information on either the distribution of summary statistics for normal individuals, perhaps from previous analysis, or the fraction of individuals which are outlying can both be specified through prior distributions. See Supplementary Material for details.

Approximation for robust detection of outliers

To facilitate the use of Gibbs sampling, we used conjugate priors for the model parameters, except for the variance of the outlier class. To ensure identifiability, we assume that the SD of the outliers (for which Zi=1) is factor λ larger than the SD of the normal individuals (for which Zi=0) so that:

The parameter λ is fixed a priori and controls the stringency of the outlier classification. Using this hard prior assumption, the variance of outlier class is completely determined by the variance of the normal class. We made the additional assumption that the percentage of outlier samples is small, so that all the information about the variance of the normal class is assumed to come from the normal individuals:

This assumption adds robustness to the model: the distribution of the outliers will have little impact on the model fit which, because of the light tails of the Guassian distribution, can be heavily influenced by outlying observations. The approximation is similar in motivation to the concept of trimmed-likelihoods, where the likelihood is computed after trimming the least likely observations (Hadi and Luceno, 1997) or perhaps also to contamination models, where the influence of the outliers goes to zero.

3 APPLICATION

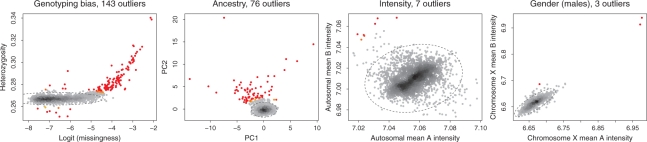

We applied the clustering approach independently to four different control datasets genotyped as part of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2). These comprised 2918 samples from the 1958 Birth Cohort (58C) and 2530 National Blood Service controls (UKBS) genotyped on the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP 6.0 and the Illumina custom Human 1.2M-Duo chips. We considered four different quality control criteria, based on summaries of each individual's genotypes or probe intensities:

Genotyping bias: genome-wide heterozygosity (the fraction of heterozygote calls) and call rate (the proportion of missing genotypes). Indicative of assay failure, contamination or inbreeeding.

Ancestry: projection of individual's genotypes onto two axes of variation which differentiate individuals with European, Asian and African ancestry. Indicative of individuals with atypical ancestry with respect to the majority of the sample.

Intensity: genome-wide average of the probe intensities which target the two alleles at each autosomal SNP. Indicative of partial assay failure or insufficient normalization.

Gender: for females and males separately, the mean probe intensities across SNPs on chromosome X. Indicative of incorrect gender assignment.

Results are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures S1–S3 for, 58C and UKBS samples genotyped on Affymetrix and Illumina platforms, respectively. As well as being statistically principled, in practice, it is helpful that, once the prior distributions have been specified, identification of outliers is automatic. Empirically, it appears to make sensible inference for a range of normal and outlier distributions, suggesting it is useful for quality control in GWAS [successfully applied in, for example Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium & the WTCCC2 (2010); The International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & the WTCCC2 (2011); The UK IBD Genetics Consortium & the WTCCC2 (2009)] and perhaps in other settings.

Fig. 1.

Outlier identification for 2918 58C samples genotyped on Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP 6.0. ‘Normal’ individuals are coloured from black to grey, with darker colours denoting higher density of individuals. Outliers are coloured from orange to red, with redder colours denoting higher posterior probability of being an outlier. The 99% confidence ellipse of the inferred distribution of ‘normal’ individuals is shown as a dashed grey line.

Funding: This work was supported by Wellcome Trust awards 090532/Z/09/Z, 075491/Z/04/B and 084575/Z/08/Z. PD was supported in part by a Royal Society Wolfson Merit Award and CCAS by a Nuffield Department of Medicine Scientific Leadership Fellowship.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†A list of participants and affiliations appear in Supplementary Material.

REFERENCES

- Hadi A.S., Luceno A. Maximum trimmed likelihood estimators: a unified approach, examples, and algorithms. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1997;25:251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium & the WTCCC2. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:985–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & the WTCCC2. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UK IBD Genetics Consortium & the WTCCC2. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1330–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.