Summary

The attachment of bacteria to surfaces provides advantages such as increasing nutrient access and resistance to environmental stress. Attachment begins with a reversible phase, often mediated by surface structures such as flagella and pili, followed by a transition to irreversible attachment, typically mediated by polysaccharides. Here we show that the interplay between pili and flagellum rotation stimulates the rapid transition between reversible and polysaccharide-mediated irreversible attachment. We found that reversible attachment of Caulobacter crescentus cells is mediated by motile cells bearing pili and that their contact with a surface results in the rapid pili-dependent arrest of flagellum rotation and concurrent stimulation of polar holdfast adhesive polysaccharide. Similar stimulation of polar adhesin production by surface contact occurs in Asticcacaulis biprosthecum and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Therefore, single bacterial cells respond to their initial contact with surfaces by triggering just-in-time adhesin production. This mechanism restricts stable attachment to intimate surface interactions, thereby maximizing surface attachment, discouraging non-productive self-adherence, and preventing curing of the adhesive.

INTRODUCTION

Many organisms derive important competitive advantages from their attachment to surfaces and the mechanisms by which they settle on a surface are subject to important regulation. For example, in sessile marine and aquatic invertebrates such as mussels, barnacles and oysters, it is well established that during the transition from the free swimming larval stage to the sessile adult, the larva reversibly contact the surface, testing and responding to the physical and chemical composition of its environment, prior to cementation and an irreversible commitment to stationary life (Tamburri et al., 1992, Morse, 1990). Surface attachment is also advantageous for bacteria because it increases nutrient access and resistance to environmental stress, and they have evolved many strategies that improve the efficiency of the attachment process.

Decades of research have clearly determined that bacterial attachment proceeds in two stages, a reversible stage that involves transient surface interactions and an irreversible stage that depends on adhesins responsible for mediating permanent attachment (van Loosdrecht et al., 1990a, van Loosdrecht et al., 1990b, Van Dellen et al., 2008, Agladze et al., 2005, Beloin et al., 2008, Vigeant et al., 2002, Hinsa et al., 2003, Otto, 2008). Flagellar motility and thin surface structures such as pili often mediate the reversible adhesion phase and allow cells to overcome the electrostatic repulsion as they approach a surface. In addition, bacteria produce exopolymers, such as adhesive polysaccharides, to mediate the transition from reversible to irreversible binding and increase their force of adhesion to surfaces. The temporal mechanism by which this transition occurs however has remained mysterious (Karatan & Watnick, 2009).

In this study, Caulobacter crescentus is used a model bacterium to study the dynamics of cell-to-surface binding. C. crescentus, exhibits a dimorphic life cycle in which each cell division produces a motile swarmer cell and a sessile stalked cell (Fig. 1). Swarmer cells (SW) harbor pili and a flagellum at the same pole. These cells are unable to initiate DNA replication and are motile for approximately 25–30 min under the conditions used in these studies, unless they attach to a surface. After the motile period, swarmer cells differentiate into stalked cells (ST) by shedding their flagellum, retracting their pili, and synthesizing an adhesive polysaccharide holdfast and a stalk. The holdfast is composed at least in part of a polysaccharide of N-acetylglucosamine that is required for irreversible adhesion to surfaces (Merker & Smit, 1988). Stalked cells initiate DNA replication, elongate, and eventually synthesize a flagellum at the pole opposite the stalk, forming the predivisional cell (PD). Flagellum rotation is initiated just prior to the completion of cell division, which always produces a swarmer cell and a stalked cell. Initial surface adhesion occurs during the swarmer phase (Bodenmiller et al., 2004, Levi & Jenal, 2006) and permanent adhesion is cemented by the holdfast, which binds to surfaces with an impressive strength in the µN range (Tsang et al., 2006). Therefore, the availability of a portion of the life cycle in which the adhesive polysaccharide is absent allows the investigation of factors that regulate its synthesis and its correlation with surface adhesion.

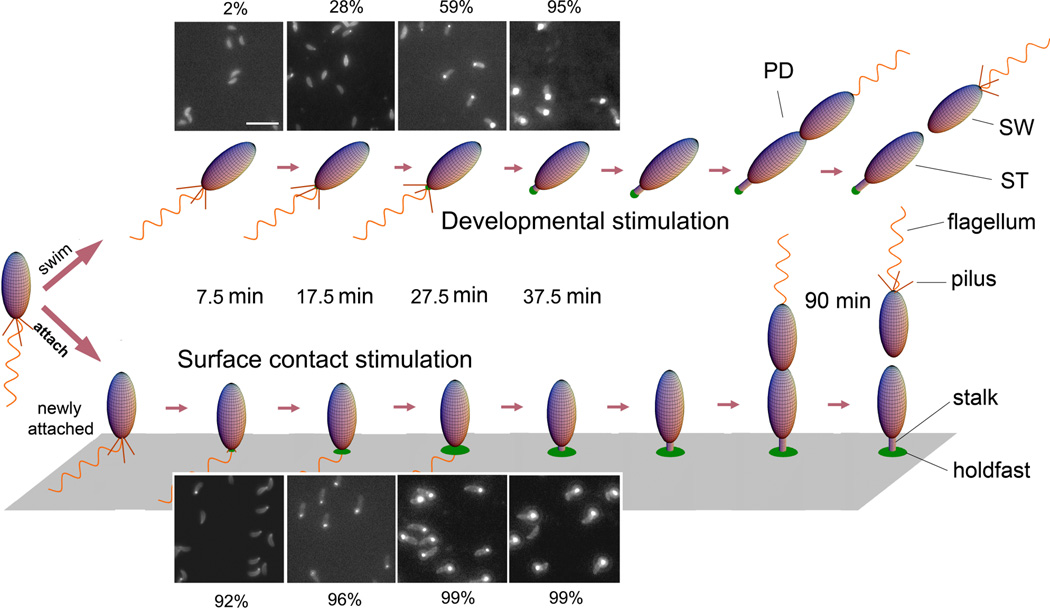

Figure 1.

Cell cycle diagram and holdfast production of unattached or attached C. crescentus cells. Fluorescence images show unattached (top) and attached (bottom) synchronized C. crescentus wild-type cells labeled with fluorescein-WGA and imaged at ages 7.5 ± 2.5 min, 17.5 ± 2.5 min, 27.5 ± 2.5 min, and 37.5 ± 2.5 min. The contrast of the images was scaled up to show the dim cell body due to non-specific labeling. The bright spot at the pole of a cell body is the holdfast. The percentage of cells with a holdfast at each time point is indicated. Attached cells rapidly produce a holdfast after surface contact, whereas unattached swarmer cells produce a holdfast just prior to differentiating into stalked cells.

Here, we take advantage of the fact that C. crescentus and several species of alphaproteobacteria synthesize polar adhesive polysaccharides (Laus et al., 2006, Brown et al., 2009, Tomlinson & Fuqua, 2009b) to show that surface contact triggers the rapid production of adhesins and to investigate the mechanism that drives the transition between reversible and irreversible attachment. We find that the interplay between pili and the flagellum during initial surface interactions causes the rapid, just-in-time production of the Caulobacter crescentus adhesin, the holdfast polysaccharide, thereby driving the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment. We show that the surface contact stimulation of adhesive polysaccharides is a general phenomenon as it also occurs in two other bacterial genera, the stalked bacterium Asticcacaulis biprosthecum and the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Surface contact stimulates the rapid, protein synthesis independent deployment of the holdfast adhesin

In order to determine if surface contact influences the biosynthesis of the holdfast polysaccharide adhesin, C. crescentus swarmer cells, which do not harbor a holdfast, were collected following synchronization and divided into two treatments. To monitor holdfast production in attached cells, an aliquot of swarmer cells was placed on a coverslip for 5 min to allow cells to attach. Unattached cells were washed away and the attached cells were grown, followed by labeling for holdfasts. To observe holdfast production in unattached cells, synchronized swarmer cells were diluted 100-fold in PYE medium such that few cells could contact the surfaces until they were labeled for holdfasts. The holdfasts of both populations were labeled at specific time points with fluorescein conjugated WGA lectin (fluorescein-WGA), which specifically binds to holdfast polysaccharide (Umbreit & Pate, 1978, Merker & Smit, 1988). Fluorescence microscopy analysis indicated that attached cells produce a holdfast much earlier than unattached cells; more than 90% of attached cells had a holdfast within 7.5 min in contrast to only 2% of unattached cells. Unattached cells took ∼37.5 min to reach a level similar to that of attached cells at 2 min (Fig. 1).

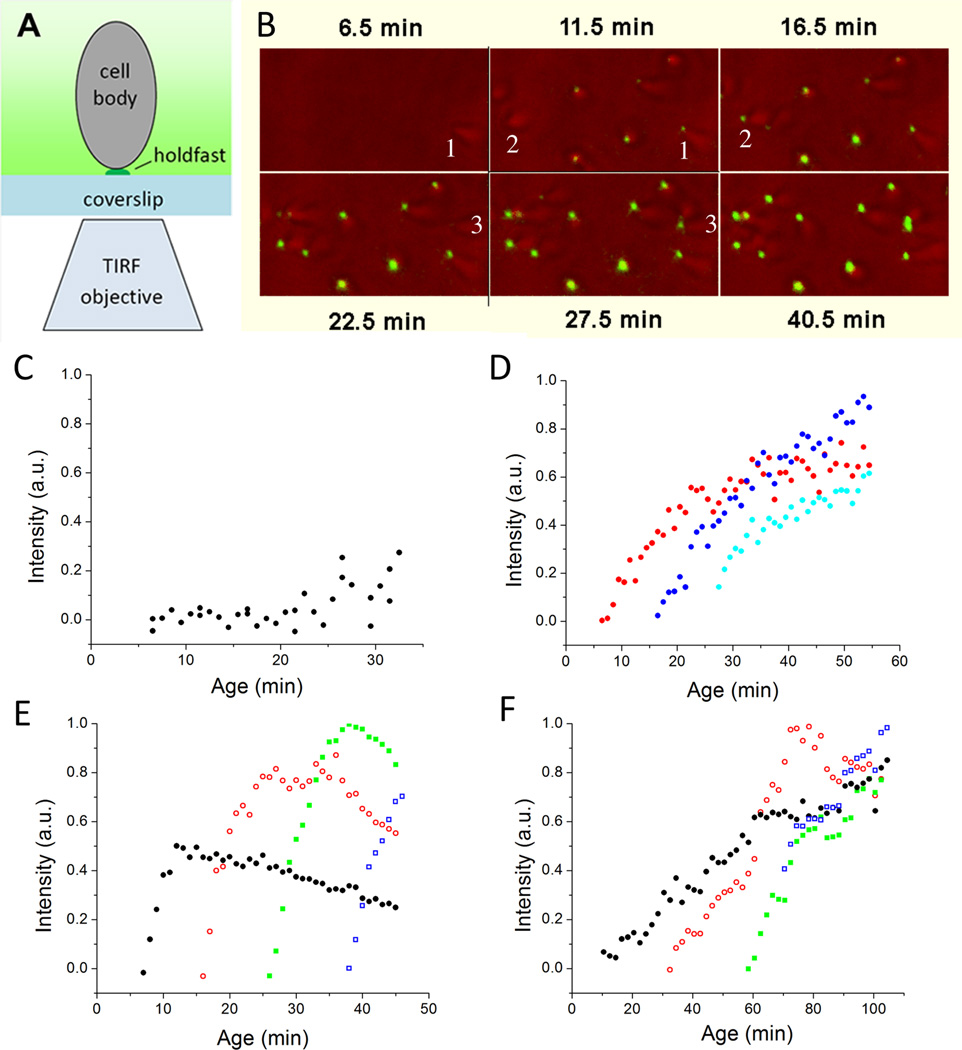

To improve the time resolution of the study of holdfast synthesis in single cells, total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy was used to observe and quantify holdfast production in real time by measuring the integrated fluorescence intensity of the labeled holdfast of individual attached cells in the presence of fluorescein-WGA (Fig. 2A and Movie S1). During the first ∼20 min after the synchrony, virtually all cells lacked holdfast prior to their contact with the surface (Fig. 2B, 2C, 2D and S1A). Througout this time interval, the timing of holdfast production depended on the time of attachment to the surface, rather than the age of the cell, and it occurred within 1–2 min of contact (Fig. 2D, S1A). Furthermore, stimulation of holdfast production did not require de novo protein synthesis since holdfast synthesis was still triggered by surface contact in the presence of a growth inhibiting concentration of kanamycin (Fig. 3A). This observation is consistent with previous work showing that addition of kanamycin, choloramphenicol, or tetracycline had no effect on attachment or holdfast biogenesis during the cell cycle of planktonic C. crescentus cells (Levi & Jenal, 2006). Thus, surface contact stimulates rapid holdfast production by a post-translational mechanism that would involve activating the holdfast polysaccharide biosynthesis or export machinery (Toh et al., 2008, Smith et al., 2003). In contrast, 25 min after synchonization, nearly all C. crescentus cells, including the unattached cells in suspension, had detectable holdfast (Fig.1, 2C, 2D, S1A). This observation is readily explained by cell-cycle dependent holdfast production, which occurs slightly prior to swarmer-to-stalk cell transition (Levi & Jenal, 2006).

Figure 2.

Holdfast production observed for individual cells with TIRF microscopy. A) Schematic drawing showing the configuration of the TIRF microscopy and a cell attached to the coverslip. Only the fluor (shown in green) within a couple hundred nanometers from the coverslip is visible. B) Overlay of light and TIRF images obtained during a time course with wild-type C. crescentus. Cells arrive at the surface without a holdfast but the holdfast is detected in the next image, which was taken five min later (see numbered examples). C) Integrated intensity in arbitrary unit (a.u.) of the TIRF image of the holdfast of newly attached wild-type C. crescentus cells. Each black dot represents the data from a newly attached individual cell. D) Integrated intensity of the TIRF images of the holdfasts of three wild-type C. crescentus CB15 cells after attachment at an age of 6.5 min (red), 16.5 min (blue), and 26.5 min (cyan). Each color shows the fluorescence intensity for a single cell as it varies through time. E) Integrated intensity of the TIRF images of the holdfasts of four A. biprosthecum cells after attachment at an age of 7.5 min (black), 16.5 min (red), 26.5 min (green), and 38.5 min (blue). Each color shows the fluorescence intensity for a single cell as it varies through time. The fluorescence intensity eventually declines due to photobleaching. F) Integrated intensity of TIRF image of the holdfasts of four A. tumefaciens cells after attachment at an age of 10.5 min (black), 32.5 min (red), 58.5 min (green), and 70.5 min (blue). Each color shows the fluorescence intensity for a single cell as it varies through time.

Figure 3.

Integrated intensity of the TIRF images of the holdfasts of A) three C. crescentus wild-type cells in medium with 10 µg/ml kanamycin at ages of 7.5 min (black), 15.5 min (red) and 26.5 min (green); B) three C. crescentus wild-type cells in medium with 10% (w/v) Ficoll 400 attached at an age of 7.5 min (black), 14.5 min (red), and 21.5 min (green); C) three C. crescentus ΔpilA cells in medium with 10% (w/v) Ficoll 400 attached at an age of 9.5 min (black), 15.5 min (red), and 25.5 min (green).

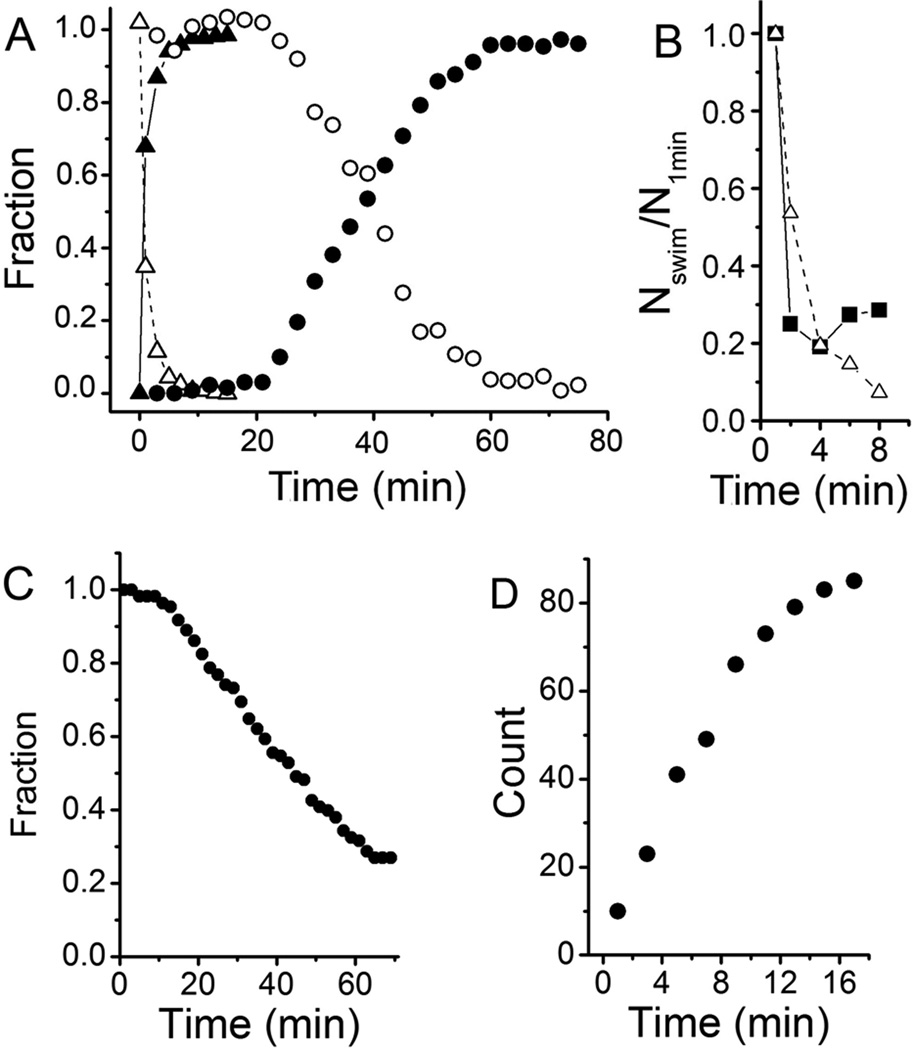

The results presented above imply that the initial attachment of newborn swarmer cells to surfaces is not mediated by the holdfast, whose synthesis or export must be stimulated in order to transit from reversible attachment to holdfast-mediated permanent attachment. In order to test this model, we observed attachment of an ΔhfsA mutant, which is deficient in holdfast synthesis (Smith et al., 2003), using a quantitative darkfield microscopy assay. After processing overlays of sequential images (see Experimental procedures) attached cells appear as stationary foci and are readily distinguished from swimming cells, which generate trajectories (Fig. S2). Swarmer cells of the ΔhfsA mutant initially attached to the glass surface nearly as efficiently as wild-type (Fig. 4B). However, they did not permanently adhere and progressively detached from the surface (Fig. 4C). In contrast, once attached, the number of attached wild-type cells remained the same for at least 90 min (data not shown). Thus, the holdfast is not required for the initial reversible weak attachment, suggesting that the stimulation of holdfast production drives the transition to the permanent adhesion stage.

Figure 4.

Attachment of C. crescentus strains CB15 (wild-type), ΔpilA, and ΔhfsA to glass surfaces. A) The fraction of attached (solid symbol) and swimming cells (open symbol) in the field of view at various times after the synchronized cells were placed between two glass surfaces separated by 12 µm. Synchronized wild-type cells (triangle) attached at a rate of 68% of cells per min immediately after birth and almost all of them had attached to the glass surface within 5 min. Synchronized ΔpilA cells (circle) only began to attach after 20 min and their attachment occurred at a rate of 2.8% of cells per min. B) Attachment of C. crescentus wild-type (triangle) and ΔhfsA (square) cells. Since the ΔhfsA strain cannot be synchronized the number of swimming cells in mixed populations (containing swarmer, stalked and predivisional cells) of both strains was normalized to that at 1 min as a function of time after the culture at mid-exponential phase was placed between two glass surfaces separated by 12 µm. C) Fraction of C. crescentus ΔhfsA cells attached to a surface decreases over time as observed under light microscopy. In a similar experiment, wild-type cells remained attached to the surface for at least 90 min (data not shown). D) Number of cells from mixed culture of a ΔpilA ΔflgE double mutant attaching to a surface. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase, placed between two coverslips, and a 40 X objective was focused on the bottom surface to take videos. Because these cells do not swim, most cells settled on the bottom surface. Unattached cells were distinguished from attached cells because unattached cells are subject to Brownian motion while attached cells are not.

Pili-mediated flagellar rotational arrest stimulates holdfast synthesis

How is reversible attachment mediated when cells encounter a surface? We used video microscopy to observe the dynamics of single cell attachment in real time. As C. crescentus wild-type cells attached to the surface, they rapidly became tethered (Movie S2). Immediately after attachment, the cell body continued to rotate due to the rotation of the flagellar motor. The majority of attached cells stopped rotation within a few seconds and formed a stable association with the surface, whereas a low proportion of cells continued rotation for a short period, but then detached and swam away. In order to quantify the efficiency of surface attachment in a population, synchronized cells were placed between two glass surfaces separated by 12 µm and were observed with darkfield microscopy with a 10× objective, allowing cells at any depth in the field of view to be imaged. Surface attachment was extremely rapid; 68% of the swarmer cells had attached to the surface within 1 min, and virtually all the cells had attached within 5 min (Fig. 4A).

C. crescentus pili are co-localized with the flagellum at the future pole of holdfast synthesis and are required for efficient surface attachment (Bodenmiller et al., 2004, Levi & Jenal, 2006, Entcheva-Dimitrov & Spormann, 2004). In order to assess the role of pili in the dynamics of single cell attachment, we synchronized swarmer cells of a mutant lacking pili, ΔpilA, and observed the cells by video microscopy. ΔpilA cells were rarely found attached to the surface. Occasionally, a ΔpilA cell became tethered to the surface by its flagellum, but the motor continued to rotate until the cell detached and swam away (Movie S3). Notably, the flagellum motor of tethered ΔpilA cells rotates considerably slower (60 Hz) than the motor of free-swimming ΔpilA cells (∼330 Hz) (Li & Tang, 2006). Thus, the decrease in flagellum motor rotation upon tethering of ΔpilA cells does not lead to permanent attachment. In contrast, the complete stopping of motor rotation following tethering of wild-type cells results in permanent adhesion (Movie S2). Thus, we infer that pili are required to arrest flagellum rotation when cells are bound to a surface.

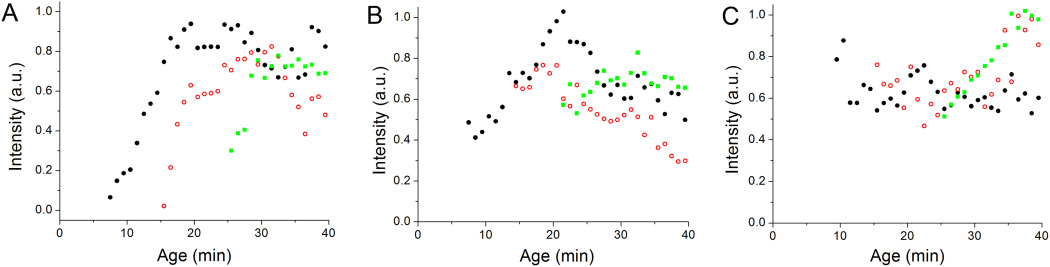

Quantitative cell attachment assays using darkfield microscopy indicated that, in stark contrast to wild-type cells, the effective attachment of ΔpilA swarmer cells only began to occur when the cells were more than 20 min old after cell division and occurred at a 24 fold lower rate than wild-type (Fig. 4A). The timing of attachment of ΔpilA swarmer cells was consistent with the timing of holdfast synthesis of unattached cells (Fig. 1, 2C, and 5), suggesting that contact between a preexisting holdfast, whose synthesis was triggered by the developmental pathway, and the surface is responsible for the attachment. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that a mutant synthesizing neither pili nor holdfasts (ΔpilA ΔhfsDAB) does not bind to surfaces since both initial reversible attachment and permanent attachment have been abolished (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that pili-mediated initial attachment is followed by rapid holdfast production that drives the transition from reversible to permanent adhesion.

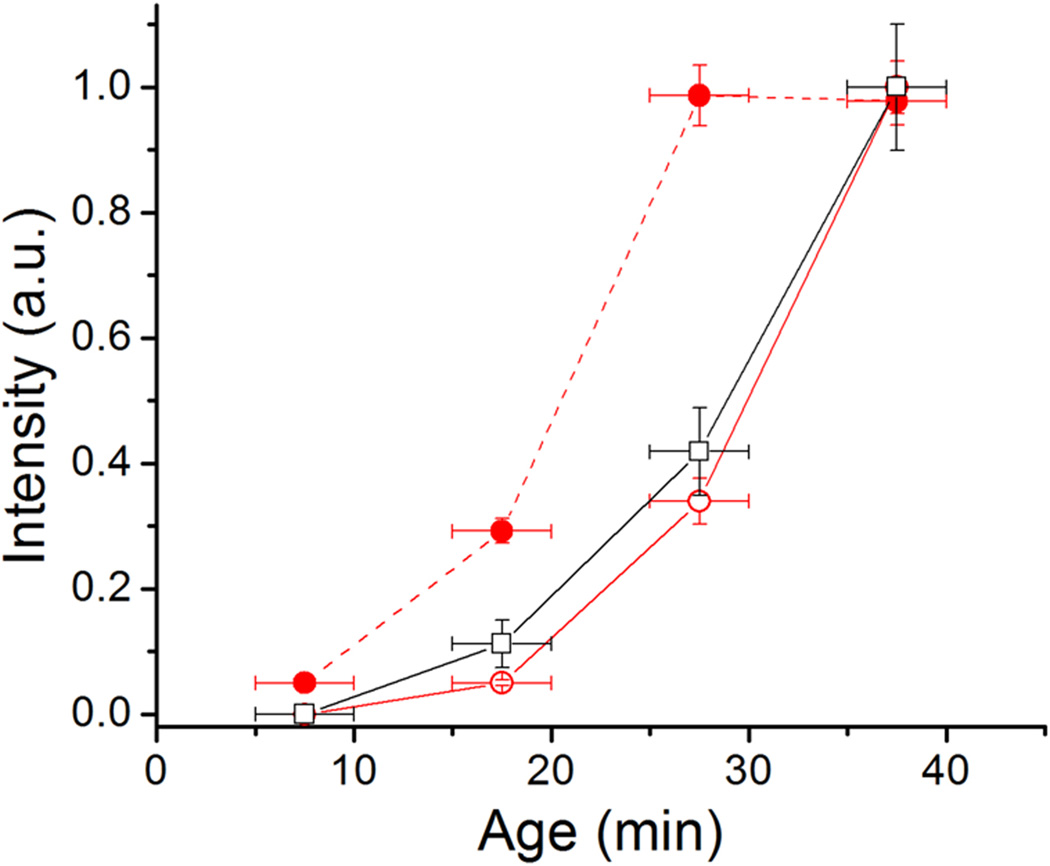

Figure 5.

Integrated fluorescence intensity of holdfast of unattached wild-type cells (open circle), wild-type attached cells (solid circle), and unattached ΔpilA cells (open square) at different ages. The error bar is the standard error of 2 to 4 measurement for each data point. Age refers to the time after cell division.

How does the initial reversible attachment stimulate holdfast production and the transition to permanent attachment? Video microscopy of the ΔpilA mutant binding to surfaces revealed that attachment of the flagellum filament enables transient attachment of the cell to the surface (Movie S3). Since the objective is focused on the surface and the cell pole remains out of focus, we infer that the flagellum-mediated attachment is not sufficient to bring the cell body into close proximity with the surface. Notably, tethering by the filament, even though it slows down flagellum rotation, appears insufficient to stimulate holdfast production since attachment of the ΔpilA mutant only becomes efficient once developmental regulation has triggered holdfast synthesis ∼20 min after cell division (Fig. 4–5). Like the ΔpilA mutant, cells from a double ΔpilA ΔflgE mutant attached at a slow rate (Figure 4D). In contrast to wild-type and ΔpilA cells, which swam to the surface and whose behavior is consistent with tethering (Movie S2 and Movie S3), cells from the ΔpilA ΔflgE mutant simply diffused to the surface. We hypothesize that adhesion by the pili brings the flagellum filament in close proximity to the surface, thereby increasing the probability of filament adhesion. Indeed, the aggregate interaction of the filament and the pili with the surface causes the rapid inhibition of motor rotation (Movie S2). This pure mechanical force may be sufficient to inhibit flagellum rotation, although it is possible that the mechanism involves a clutch or a brake type mechanism (Paul et al., 2010, Blair et al., 2008) regulated at the post-translational level. However, the rapidity by which the cell body is immobilized to the surface by the pili precludes the distinction between these mechanisms by video microscopy. Irrespective of the mechanism, inhibition of flagellum rotation is immediately followed by stimulation of holdfast synthesis, independent of the stage of the cell cycle.

Inhibition of the flagellar motor has been reported to trigger various changes in bacteria (McCarter et al., 1988, Anderson et al., 2010). To test if stopping flagellar rotation could stimulate holdfast production independent of surface attachment, we used the observation that polymer crowding agents can cause bacteria to aggregate in solution (Eboigbodin et al., 2005, Schwarz-Linek et al., 2010), due to osmotic pressure caused by the crowding polymers being excluded from the space between neighboring cells, an effect called the depletion effect (Tang et al., 1997, Hosek & Tang, 2004). We found that C. crescentus cells formed aggregates in 10% Ficoll within 1 min after the addition of the polymer. Single cells and some aggregates continued to move (Movie S4), propelled by the rotating flagellar filaments in the aggregates. Almost all the cells and aggregates stopped moving at 4 min (Movie S5), indicating that all flagella in the aggregates stopped rotation. The cells at age 17.5 min were labeled with fluorescein-WGA for fluorescence microscopy. The majority of the cells (78%) showed clear holdfasts in contrast to free swimming cells in medium without crowding agent of which only 29% had holdfast (Table 1 and Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Effect of various polymers on holdfast synthesis

| Test matrix | Viscosity (cp) |

Holdfasts /cells |

% with holdfast |

Aggregation | Motility at age 17.5 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PYE (control) | 1 | 152/529 | 29% | no | swimming |

| Percoll, 67% | 2.2 | 29/95 | 31% | no | swimming |

| PEG (8,000 da), 3.5% | 2.2 | 286/817 | 35% | yes | some moving aggregates and cells |

| PEG (35,000 da), 5% | 5.4 | 214/328 | 65% | yes | no moving aggregates or cells |

| Dextran (100,000–200,000 da), 5% | 2.2 | 228/314 | 73% | yes | no moving aggregates or cells |

| Ficoll (400,000 da), 5% | 2.2 | 151/179 | 84% | yes | no moving aggregates or cells |

| Ficoll (400,000 da), 10% | 5.2 | 174/223 | 78% | yes | no moving aggregates or cells |

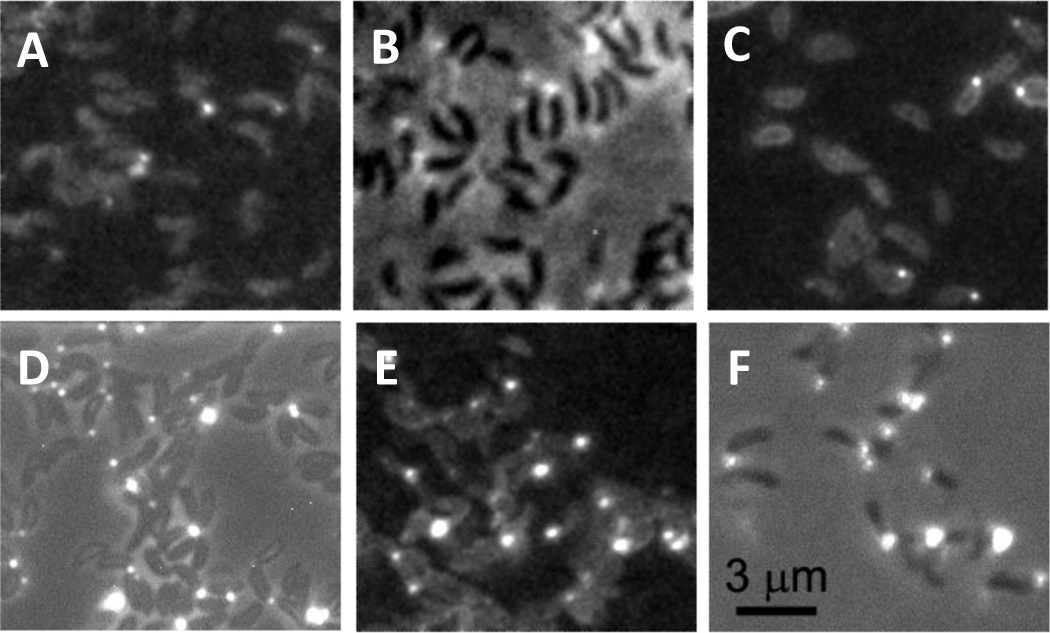

Figure 6.

Holdfast of cells at age 17.5 min grown in A) PYE medium, B) PYE medium with 67% Percoll, C) PYE medium with 3.5% PEG 8000, D) PYE medium with 5% PEG 35000, E) PYE medium with 5% Dextran, and F) PYE medium with 10% Ficoll. Panels A, C, and E are fluorescence images, which clearly show the cell bodies in addition to the holdfasts. Panels B, D, and F are overlays of fluorescence and phase contrast images.

The stimulation of holdfast production was also observed with polymers of different chemical composition that stopped flagellar motor rotation (Table 1). In contrast, polymers that did not stop flagellum rotation despite being added to a similar viscosity did not stimulate holdfast production (Table 1). The dependence of holdfast production on the inhibition of flagellum rotation triggered by viscous solution supports the notion that arrest of flagellum rotation is required for contact-dependent holdfast production. However, it is possible that the osmotic shock induced by the introduction of the viscous solution may trigger membrane stress (or another physiological change) responsible for stimulating holdfast production, although not all polymer crowding agents had this effect.

These results were confirmed with TIRF microscopy experiments in the presence of Ficoll. In contrast to what was observed in complex medium, cells in the presence of 10% Ficoll arrived at the surface with a holdfast (Fig. 3B and S3A), indicating that holdfast synthesis was stimulated prior to surface contact. Ficoll had a similar effect on ΔpilA cells, which also arrived at the surface with holdfasts already formed and adhered permanently to the surface (Fig. 3C and S3B). Therefore, pili are not required for the stimulation of holdfast synthesis by viscous agents like they are for the surface contact stimulation. This result also supports our earlier inference that, prior to the developmental trigger of holdfast synthesis, ΔpilA cells do not adhere productively after surface contact because they are unable to stimulate holdfast synthesis.

We conclude that the loss of flagellum rotation upon surface contact triggers holdfast synthesis. In addition, our results suggest that on surfaces pili are mediating the arrest of flagellum rotation, but with viscosity agents the flagellum is intrinsically impeded and the need for the pili in stimulating holdfast synthesis is bypassed. Future studies will utilize fla and mot mutants to directly determine for the contribution of the flagellum filament and motor in initial binding and the transition to permanent adhesion. At present, these experiments are complicated by the fact that these mutants have a delay in cell separation and cannot be synchronized via either the plate synchrony or density centrifugation methods. Furthermore, these mutants have altered timing of cell-cycle dependent holdfast production (data not shown). We are currently exploring alternative methods of cell synchrony to enable these studies.

Surface-contact stimulation probably activates previously assembled holdfast synthesis machinery since it does not require de novo protein synthesis. Indeed, at least the holdfast anchoring machinery (Hardy et al., 2010) and the outer membrane export protein HfsD (J. Javens et al, in preparation) are already localized at the flagellar pole in newborn swarmer cells, in close proximity to the flagellum and the pili.

Surface contact stimulation of adhesin synthesis in other bacterial genera

To determine if surface contact stimulated adhesin synthesis is a general phenomenon, we observed polar polysaccharide formation in Asticcacaulis biprosthecum and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. A. biprosthecum has a dimorphic life cycle similar to that of C. crescentus; however this bacterium produces two lateral stalks and the holdfast is made at the pole of the cell body (Pate et al., 1973). The unipolar polysaccharide (UPP) of the plant pathogen A. tumefaciens is rarely detected in single planktonic cells, but is frequently detected in cells attached to each other in rosettes or single cells attached to a surface (Tomlinson & Fuqua, 2009a). Stimulation of holdfast and UPP production following contact with a surface was readily observed in both species using TIRF microscopy. For A. biprosthecum, nearly every cell arrived at the surface without a holdfast, but these were detected as early as 2 min after contact, irrespective of cell age (Fig. 2E and S1B; Movie S6). For A. tumefaciens, most cells produced UPP within 3 min of attaching to a glass surface (Fig. 2F and S1C; Movie S7). We also tested whether the production of UPP was stimulated by contact with Arabidopsis roots, a more natural surface for A. tumefaciens attachment. UPP production occurred preferentially among cells attached to an Arabidopsis root when compared to unattached cells from the same population (Fig. 7A; Movie S8) and UPP production occurred after initial attachment of A. tumefaciens cells to the Arabidopsis root (Fig. 7B; Movie S9). These data indicate that surface contact dependent stimulation of polar polysaccharide production is conserved in multiple bacterial species.

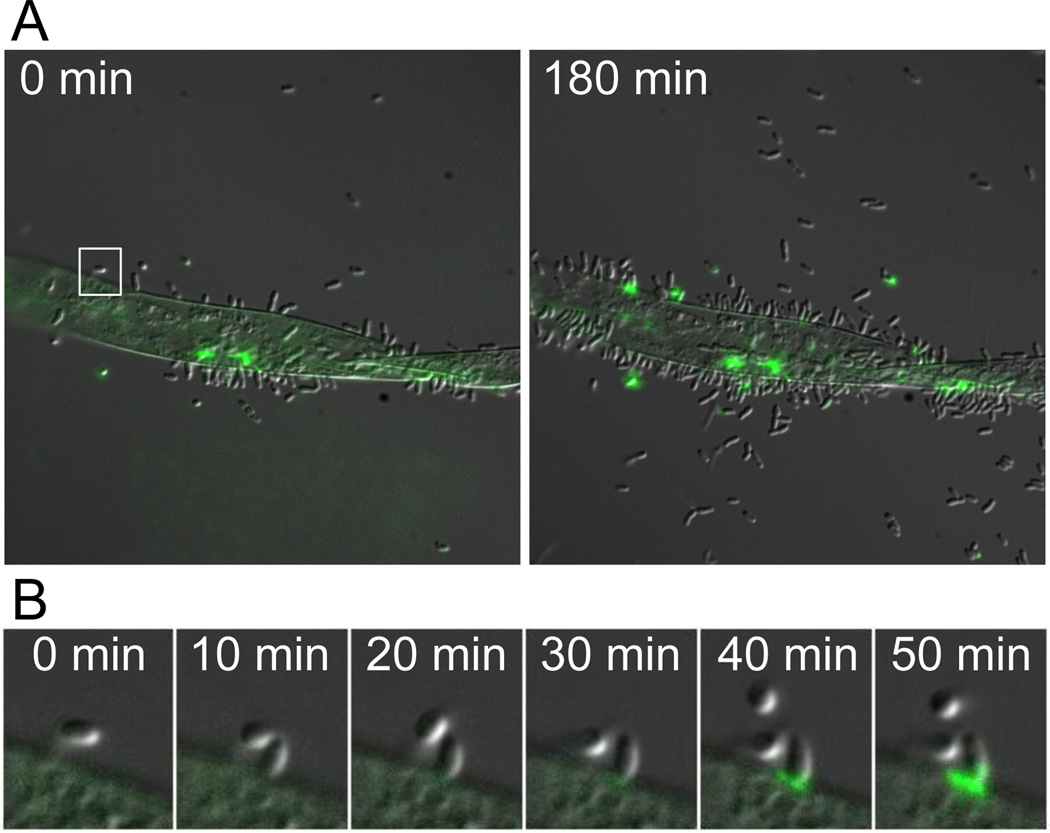

Figure 7.

Timelapse microscopy of Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells attaching to Arabidopsis roots. Production of UPP was monitored using WGA-AlexaFluor 488. A) At the initial time point, few cells are attached to the root and little UPP is detected. After 180 min, many more cells are attached to the root and UPP is frequently detected along the junction between the bacterial cells and the root. UPP is rarely observed in the unattached cells. B) Close-up of the region boxed in A. A single A. tumefaciens cell attaches to the root and subsequent production of UPP is observed.

Advantages of surface contact stimulation of adhesin synthesis

We have shown that the ability to rapidly produce a permanent adhesin is shared among at least three members of the Alphaproteobacteria, in which motile cells differentiate to become sessile cells. For many motile bacteria, initial attachment is reversible, allowing cells to detach and sample other surfaces (Hinsa et al., 2003, Korber et al., 1994). The ability to rapidly deploy a permanent adhesin may be advantageous for swimming cells that have encountered a favorable environment, enabling colonization.

Another advantage of just-in-time adhesin deployment upon surface contact is that it reduces the chances that the adhesive will be inactivated. Once exported from the cell, two main factors can reduce the adhesiveness of an adhesin; curing, as observed in the mussel byssal thread (Kamino, 2008) and also with man made glues, and occlusion of the adhesin with microscopic particles after random collision events. Either mechanism would be expected to decrease adhesiveness over time, limiting productive interactions with a surface. Indeed, previous experiments showed that permanent surface adhesion is highest during the swarmer phase of the C. crescentus developmental cycle and drops dramatically during the stalked cell stage despite the presence of a holdfast on stalked cells (Bodenmiller et al., 2004, Levi & Jenal, 2006). These results support the hypothesis that holdfast adhesiveness decreases with time after export and suggest that the ability to rapidly stimulate adhesin formation upon initial contact with a surface dramatically improves the efficiency of surface interaction and colonization.

Polar attachment of single bacterial cells as a prelude to the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment has also been seen in other proteobacteria such as Escherichia coli (Agladze et al., 2005) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Caiazza & O’Toole, 2004). Therefore, contact-dependent adhesin deployment may be a commonly utilized strategy to improve adhesion. As surface-associated adhesins may also act to stimulate host defense responses, this timing may also come into play during pathogenesis to ensure that potential antigens are not prematurely exposed to the host immune system.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains and synchronization

C. crescentus strains were grown at 30°C in peptone-yeast extract (PYE) medium (Poindexter, 1964) with 10 mg/ml kanamycin when indicated. The following C. crescentus strains were used in this study: YB135 (CB15 wild-type), YB4038 (CB15 ΔpilA), YB5086 (CB15 ΔpilA ΔflgE) and YB2833 (CB15 ΔhfsA). A. biprosthecum strain JH2 (YB1113) was grown at 26°C in PYE. A. tumefaciens strain C58 (YB2951) was grown at 26°C in LB. Synchronized newborn cells were obtained using the plate release technique (Degnen & Newton, 1972). Briefly, cultures were grown for ∼10 hours with shaking at 100 rpm. Three ml of the culture was added to 20 ml fresh growth medium in a 9 cm diameter plastic Petri dish and grown at room temperature overnight (or 48 hrs for A. tumefaciens with medium changes every 12 hrs) with shaking at 60 rpm. After growth, a monolayer of cells was attached to the surface of the Petri dish. The Petri dish was washed thoroughly with water to remove loosely attached and unattached cells. Twenty ml fresh medium was added to the Petri dish and the cells were grown further at room temperature for ∼4 hours with shaking at 60 rpm. The Petri dish was then grown for 1 more hour at 30˚C for C. crescentus and 26˚C for A. biprosthecum and A. tumefaciens. The Petri dish was washed repeatedly with oxygenated fresh medium to remove unattached cells and 1 ml fresh medium was added to the plate, which was incubated for 5 min without shaking. The synchronized cells were harvested from the 1 ml fresh medium. The resulting newborn cells differ in age by a maximum 5 min after cell division.

Fluorescence labeling and fluorescence microscopy

Labeling holdfasts of attached cells

The holdfast is composed of a polysaccharide containing N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNac), which can be labeled with fluorescein-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin lectin (fluorescein-WGA) (Merker & Smit, 1988, Ong et al., 1990). A drop of culture containing synchronized swarmer cells was placed on a coverslip for 5 min to allow some cells to attach to the glass surface. The unattached cells were rinsed with PYE. The cells attached to the coverslips were then grown in oxygenated PYE at 30 °C for various amounts of time. After growth, the coverslips were rinsed with water and the cells were labeled with 0.02 mg/ml fluorescein-WGA (Molecular Probes) and 0.05% w/v of the bacteriocide sodium azide on ice for 15 min. After labeling, the coverslips were rinsed with 0.05% w/v sodium azide three times and antiphotobleaching solution (20 µg/ml catalase, 0.5 mg/ml glucose, 0.1 mg/ml glucose oxidase, and 0.25 % v/v mercaptoethanol) was added to the slide for fluorescence microscopy.

Labeling holdfasts of unattached cells

One milliliter of synchronized swarmer cells was added to 100 ml oxygenated PYE and grown at 30 °C without agitation for various amounts of time. In this large volume, very few cells get sufficiently close to the surface to attach. After growth, the unattached cells were supplemented with 0.05% w/v sodium azide and transferred to a pre-cooled glass beaker. Fluorescein-WGA was added to a final concentration of 20 mg/ml and the cells were labeled for 15 min on ice. The solution was then passed through an Isopore membrane of 0.4 µm pore size (Millipore Inc.) to collect the cells. The collected cells on the membrane were further washed with cold 0.05% w/v sodium azide solution to remove excess dyes. Antiphotobleaching solution was added for fluorescence microscopy.

Attachment of C. crescentus on a glass surface

Immediately after synchronization, an aliquot of synchronized cells was placed between a coverslip and a glass slide that had been cleaned with a solution of 6.5 g Nochromix (Godax Laboratories, Inc.) in 100 ml sulfuric acid for 30 min, rinsed thoroughly with water and dried in air before use. The slide sample was quickly transferred to a warm stage kept at 30°C and observed with darkfield microscopy with a 10× objective, allowing cells at any depth in the field of view to be imaged. To monitor the attachment process, a 1-second-long video was taken at 10 frames per second every 2 to 3 min. To identify attached cells, an average image was obtained by overlaying the ten frames of a video and dividing the intensity of the overlay by 10. Since the swimming cells are moving, the brightness of swimming cells is ten times weaker than that of attached cells in the average image, and therefore the attached cells can be identified by appropriately scaling the image to show only the bright spots (Fig. S2A and S2B). The attached cells were counted from such images. Attached cells can be distinguished from unattached non-swimming cells because the later drift randomly due to Brownian motion, while attached cells do not. To image the swimming cells, we removed the attached cell from the video by subtracting the average image from each frame. Three consecutive frames were then overlaid and the number of trajectories was counted as the number of swimming cells (Fig. S2C and S2D). The thickness of the sample was measured using phase contrast microscopy with a 100× objective by focusing on the top and bottom surfaces respectively (Li & Tang, 2004).

The strain YB2833 (ΔhfsA) lacks a holdfast, is unable to form a stable monolayer, and therefore cannot be synchronized by plate release. To quantify its attachment, YB2833 cells were grown to exponential phase in a mixed culture, centrifuged, and resuspended in fresh PYE. An aliquot was confined between a coverslip and a glass slide and the sample was observed by darkfield microscopy at 30°C. The culture at mid-exponential phase is a mixture of swarmer cells, stalked cells, and predivisional cells. We measured the decrease in the number of swimming cells as a measure of attachment by counting the number of cell trajectories as described above. The attached cells could easily be washed off the surface, unlike similarly treated wild-type cells, which are tightly attached through their holdfast. Although this strain is able to attach to glass surface through pili, the attachment is not permanent. To quantify the detachment, we added a drop of cell culture at mid-exponential phase to a coverslip, allowed it to sit for 2 min and rinsed gently to remove unattached cells. The number of attached cells was recorded under the light microscope over time.

Labeling holdfast in viscous media

The test viscosity agents used included Percoll (GE), PEGs of molecular weight 8000 da and 35000 da (Fluka), dextran of molecular weight 100,000–200,000 da (Sigma), and Ficoll of molecular weight 400,000 da (Fluka). The viscosity was measured with the falling ball method (Tang et al., 1999), except for PEG 8000 (Gunduz, 1996) and Ficoll (Chen & Berg, 2000), which are obtained from the literature. Synchronized C. crescentus wild-type cells were mixed with these agents at the designated concentration and 10 µg/ml fluorescein-WGA in PYE in a 1 ml tube. A portion of the mixture was taken out to make slide samples at different times to observe cell swimming and aggregation. To observe holdfast labeling 15 min after mixing, the mixture was passed through a 0.44 µm microfilter (Millipore, Inc.), followed by passing 60 ml water to wash the cells trapped by the filter. About 100 µl water was left in the filter to collect the cells, which became dispersed by the procedure. The cells were then dried on a coverslip for microscopic observation.

Fluorescence microscopy

A Nikon Eclipse E800 epifluorescence microscope with a 100 X oil immersion objective lens (Plan Apo) was used to image the fluorescently labeled holdfast. A highly sensitive and linear CoolSnap camera controlled by MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, PA) was used to record labeled holdfast fluorescence. The fluorescence images were taken at 0.1 s exposure time. To keep the same photobleaching time for each sample, we focused on the holdfast by taking successive pictures under fluorescence microscopy after readjusting the sample stage height between pictures. If the holdfast was in focus prior to the 11th exposure, subsequent exposures were taken and the picture taken at the 11th exposure was used to measure the fluorescence intensity.

TIRF microscopy

TIRF microscopy was performed with a Nikon E2000 inverted microscope with a TIRF objective (NA=1.49). Two hundred µl of synchronized swarmer cells (2.5±2.5 min old) in 20 µg/ml fluorescein-WGA lectin solution in PYE was added to a cleaned coverslip sitting on top of the TIRF objective. Some of the dye adsorbed to the coverslip, facilitating focusing of the microscope. After focusing, the TIRF illumination was kept on for 2 min to photobleach the adsorbed dye. Since the TIRF setting varies from experiment to experiment, it is hard to control the light intensity on the holdfast and inconsistent levels of photobleaching are observed. Light microscopy images and TIRF images were taken alternately with 30 sec interval to get a time series. The integrated intensity of the TIRF image of individual holdfasts was measured over time. For experiments in the presence of polymers, cells were mixed with the polymers as indicated and 20 µg/ml fluorescein-WGA lectin prior to TIRF observation. All the experiments were performed at approximately 22 °C.

A. tumefaciens UPP production during attachment to an Arabidopsis root

Sterilized Arabidopis thaliana seeds were placed on ½ MS salts plates with 1% agar and 1% sucrose and allowed to germinate and grow until the roots were approximately 3 cm long (Ramey et al., 2004). Wild-type A. tumefaciens cells were grown in LB medium at 26°C until reaching exponential phase. 200 µl of cell culture was washed and resuspended in a solution containing 1 mM calcium chloride and 0.4% sucrose. The bacterial cell suspension was spotted into a petri dish and a root segment was floated in the bacterial cell suspension. The root segments were incubated in the bacterial culture overnight in the dark at room temperature. The root segments were rinsed in 1 mM calcium chloride and 0.4% sucrose to remove unattached cells and placed on an agarose pad containing Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated-WGA. The attachment of A. tumefaciens cells to the root segments was observed using timelapse microscopy. A. tumefaciens attachment to the root occurs prior to the formation of UPP and this structure is rarely observed in the unattached cells (Fig. 7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Initial stages of this work were supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM51986 and an Indiana University Faculty Research Support Program grant to Y.V.B., and by a grant from the Indiana METACyt Initiative of Indiana University (funded in part through a major grant from the Lilly Endowment, Inc.) to C.F. and Y.V.B. The major portion of this work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM077648 to Y.V.B. and J.X.T. and GM080546 to C.F. P.J.B.B. was supported by a postdoctoral National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award number F32AI072992 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors thank Peter Merritt for his assistance in growing Arabidopsis thaliana, Daniel Kearns, and members of their laboratories for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Supporting information is available at (web site link to be supplied at time of publication).

References

- Agladze K, Wang X, Romeo T. Spatial periodicity of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm microstructure initiates during a reversible, polar attachment phase of development and requires the polysaccharide adhesin PGA. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:8237–8246. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8237-8246.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JK, Smith TG, Hoover TR. Sense and sensibility: flagellum-mediated gene regulation. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloin C, Houry A, Froment M, Ghigo JM, Henry N. A short-time scale colloidal system reveals early bacterial adhesion dynamics. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KM, Turner L, Winkelman JT, Berg HC, Kearns DB. A molecular clutch disables flagella in the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Science. 2008;320:1636–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1157877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmiller D, Toh E, Brun YV. Development of surface adhesion in Caulobacter crescentus. J.Bacteriol. 2004;186:1438–1447. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1438-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Hardy GG, Trimble MJ, Brun YV. Complex regulatory pathways coordinate cell-cycle progression and development in Caulobacter crescentus. Adv Microb Physiol. 2009;54:1–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)00001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazza NC, O’Toole GA. SadB is required for the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4476–4485. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4476-4485.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Berg HC. Torque-speed relationship of the flagellar rotary motor of Escherichia coli. Biophys J. 2000;78:1036–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76662-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnen ST, Newton A. Chromosome replication during development in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Mol.Biol. 1972;129:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eboigbodin KE, Newton JRA, Routh AF, Biggs CA. Role of nonadsorbing polymers in bacterial aggregation. Langmuir. 2005;21:12315–12319. doi: 10.1021/la051740u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entcheva-Dimitrov P, Spormann AM. Dynamics and control of biofilms of the oligotrophic bacterium Caulobacter crescentus. J.Bacteriol. 2004;186:8254–8266. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8254-8266.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz U. Evaluation of viscosities of polymer-water solutions used in aqueous two-phase systems. J Chromatogr B. 1996;680:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GG, Allen RC, Toh E, Long M, Brown PJ, Cole-Tobian JL, Brun YV. A localized multimeric anchor attaches the Caulobacter holdfast to the cell pole. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:409–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsa SM, Espinosa-Urgel M, Ramos JL, O’Toole GA. Transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 requires an ABC transporter and a large secreted protein. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:905–918. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek M, Tang JX. Polymer-induced bundling of F-actin and the depletion force. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2004;69:0519071–0519079. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamino K. Underwater adhesive of marine organisms as the vital link between biological science and material science. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2008;10:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s10126-007-9076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatan E, Watnick P. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:310–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber DR, Lawrence JR, Caldwell DE. Effect of Motility on Surface Colonization and Reproductive Success of Pseudomonas fluorescens in Dual-Dilution Continuous Culture and Batch Culture Systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1421–1429. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1421-1429.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laus MC, Logman TJ, Lamers GE, Van Brussel AA, Carlson RW, Kijne JW. A novel polar surface polysaccharide from Rhizobium leguminosarum binds host plant lectin. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1704–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi A, Jenal U. Holdfast formation in motile swarmer cells optimizes surface attachment during Caulobacter crescentus development. J.Bacteriol. 2006;188:5315–5318. doi: 10.1128/JB.01725-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Tang J. Diffusion of actin filaments within a thin layer between two walls. Phys. Rev. E. 2004;69:061921. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.061921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Tang JX. Low flagellar motor torque and high swimming efficiency of Caulobacter crescentus swarmer cells. Biophys.J. 2006;91:2726–2734. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter L, Hilmen M, Silverman M. Flagellar dynamometer controls swarmer cell differentiation of V. parahaemolyticus. Cell. 1988;54:345–351. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merker RI, Smit J. Characterization of the adhesive holdfast of marine and freshwater Caulobacters. Appl. Environ.Microbiol. 1988;54:2078–2085. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2078-2085.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DE. Recent progress in larval settlement and metamorphosis: closing the gaps between molecular biology and ecology. Bull. Mac.Sci. 1990;46:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ong CJ, Wong MLY, Smit J. Attachment of the adhesive holdfast organelle to the cellular stalk of Caulobacter crescentus. J.Bacteriol. 1990;172:1448–1456. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1448-1456.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto K. Considering the first steps toward a stable and orderly way of bacterial life. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL, Porter JS, Jordan TL. Asticcacaulis biprosthecum sp.nov.: Life Cycle, Morphology, and Cultural Characteristics. Antonie van Leewenhoek. 1973;39:569–583. doi: 10.1007/BF02578901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “backstop brake” mechanism. Mol Cell. 2010;38:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poindexter JS. Biological properties and classification of the Caulobacter crescentus group. Bacteriol.Rev. 1964;28:231–295. doi: 10.1128/br.28.3.231-295.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey BE, Matthysse AG, Fuqua C. The FNR-type transcriptional regulator SinR controls maturation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1495–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Linek J, Dorken G, Winkler A, Wilson LG, Pham NT, French CE, Schilling T, Poon WCK. Polymer-induced phase separation in suspensions of bacteria. Epl-Europhys Lett. 2010;89 [Google Scholar]

- Smith CS, Hinz A, Bodenmiller D, Larson DE, Brun YV. Identification of genes required for synthesis of the adhesive holdfast in Caulobacter crescentus. J.Bacteriol. 2003;185:1342–1442. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1432-1442.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburri MN, Zimmer-Faust RK, Tamplin ML. Natural sources and properties of chemical inducers mediating settlement of oyster larvae: a re-examination. Biological Bulletin. 1992;183:327–338. doi: 10.2307/1542218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JX, Ito T, Tao T, Traub P, Janmey PA. Opposite Effects of Electrostatics and Steric Exclusion on Bundle Formation by F-actin and Other Filamentous Polyelectrolytes. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12600–12607. doi: 10.1021/bi9711386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JX, Janmey PA, Stossel TP, Ito T. Thiol oxidation of actin produces dimers that enhance the elasticity of the F-actin network. Biophys.J. 1999;76:2208–2215. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77376-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh E, Kurtz HD, Jr, Brun YV. Characterization of the Caulobacter crescentus holdfast polysaccharide biosynthesis pathway reveals significant redundancy in the initiating glycosyltransferase and polymerase steps. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7219–7231. doi: 10.1128/JB.01003-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson AD, Fuqua C. Mechanisms and regulation of polar surface attachment in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009a;12:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson AD, Fuqua C. Mechanisms and regulation of polar surface attachment in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009b;12:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang PH, Li G, Brun YV, Freund LB, Tang JX. Adhesion of single bacterial cells in the micronewton range. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.USA. 2006;103:5764–5768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601705103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbreit TH, Pate JL. Characterization of the holdfast region of wild-type cells and holdfast mutants of asticcacaulis biprosthecum. Arch.Microbiol. 1978;118:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dellen KL, Houot L, Watnick PI. Genetic analysis of Vibrio cholerae monolayer formation reveals a key role for DeltaPsi in the transition to permanent attachment. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:8185–8196. doi: 10.1128/JB.00948-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loosdrecht Mc, Lyklema J, Norde W, Zehnder AJ. Influence of interfaces on microbial activity. Microbiol Rev. 1990a;54:75–87. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.1.75-87.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loosdrecht MC, Norde W, Zehnder AJ. Physical chemical description of bacterial adhesion. J Biomater Appl. 1990b;5:91–106. doi: 10.1177/088532829000500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigeant MAS, Ford RM, Wagner M, Tamm LK. Reversible and irreversible adhesion of motile Escherichia coli cells analyzed by total internal reflection aqueous fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ.Microbiol. 2002;68:2794–2801. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2794-2801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.