Abstract

Sensory perception requires accurate encoding of stimulus information by sensory receptor cells. Here, we identify NCKX4, a potassium – dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, to be necessary for rapid response termination and proper adaptation of vertebrate olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). Nckx4−/− mouse OSNs display substantially prolonged responses and stronger adaptation. Single – cell electrophysiological analyses demonstrate that the majority of Na+ – dependent Ca2+ exchange in OSNs relevant to sensory transduction is due to NCKX4 and that Nckx4−/− mouse OSNs are deficient in encoding action potentials upon repeated stimulation. Olfactory – specific Nckx4 knockout mice have a reduced ability to locate an odorous source and lower body weights. These results establish the role of NCKX4 in shaping olfactory responses and suggest that rapid response termination and proper adaptation of peripheral sensory receptor cells tune the sensory system for optimal perception.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate encoding of spatial and temporal properties of sensory stimuli by peripheral sensory receptor cells is a prerequisite for accurate sensory perception. Tight and fast regulation of sensory transduction is necessary for the proper activation, termination, and adaptation of sensory responses, with Ca2+ often playing a critical role in all three processes. In rod and cone photoreceptors, changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels are responsible for regulating the sensitivity and kinetics of phototransduction to background light 1, while in vertebrate olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs), Ca2+ plays dual yet seemingly opposing roles in the signaling cascade 2, 3. Upon odorant stimulation, Ca2+ enters OSN cilia through the olfactory cyclic nucleotide – gated (CNG) cation channel, which is opened via the olfactory G – protein mediated signal transduction cascade 2, 3. Ca2+ in OSN cilia triggers a depolarizing Cl− current, which serves as an amplification step for membrane depolarization 4–6. Ca2+ also adapts the transduction pathway presumably by negatively regulating the activities of several transduction components, which leads to reduced sensitivity to repeated odor exposure 7. The time course over which cilial Ca2+ accumulates and is removed influences not only the sensitivity but also the rates of activation and termination of the olfactory signaling pathway. Thus, proper regulation of cilial Ca2+ dynamics should be critical for encoding olfactory stimuli.

Since OSN cilia do not contain intracilial vesicular organelles 8, Ca2+ homeostasis is believed to be achieved by plasma membrane Ca2+ transporters, including ATP – dependent Ca2+ pumps and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers 2, 9. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers are transmembrane proteins that harness the energy stored within the Na+ electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane to actively transfer Ca2+ against its electrochemical gradient. There are three families of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in mammals 10. The SLC8 family contains three NCX proteins, which exchange 3 Na+ for one Ca2+. The SLC24 family contains five NCKX proteins, which exchange 4 Na+ for one Ca2+ and one K+. The CCX family contains one member, NCLX, which is largely uncharacterized. Both NCXs and NCKXs are known to play critical roles in regulating compartmental cytoplasmic Ca2+ in sensory receptor cells, particularly in vertebrate 11 and Drosophila 12 photoreceptors. Na+ – dependent Ca2+ exchange has been observed in OSNs electrophysiologically and by Ca2+ – imaging 13–17. Inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in OSNs by replacement of extracellular Na+ results in prolonged receptor currents due to prolonged elevation of intracilial Ca2+ and continuous activation of the Cl− channel, and low extracellular Na+ also cause stronger adaptation, suggesting the importance of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in regulating olfactory transduction 13, 14, 17. Expression of several Na+/Ca2+ exchangers including members of both NCX and NCKX families has been reported in OSNs 9, 15. However, the molecular identity of the particular Na+/Ca2+ exchanger(s) involved in olfactory transduction is still undetermined.

In this study, we identified NCKX4 (SLC24a4) to be the principal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger that governs response termination kinetics and adaptation of the OSN, and that subsequently influences how odor information is encoded and perceived.

RESULTS

Nckx4 is expressed specifically in OSNs

We previously conducted a proteomic screen of OSN cilial membranes to identify novel olfactory signaling components 18. In this screen, a single Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, NCKX4 (SLC24a4), was identified. To determine the expression pattern of Nckx4 in the olfactory epithelium, we performed in situ hybridization and found that Nckx4 mRNA is expressed specifically in the layer of mature OSNs (Fig. 1a). Consistent with these findings, previous microarray evidence indicated that Nckx4 was the only Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to be enriched substantially in the olfactory epithelium 19, and specifically in OSNs 20. Together, these data implicated NCKX4 to be the leading candidate Na+/Ca2+ exchanger for regulating the OSN response.

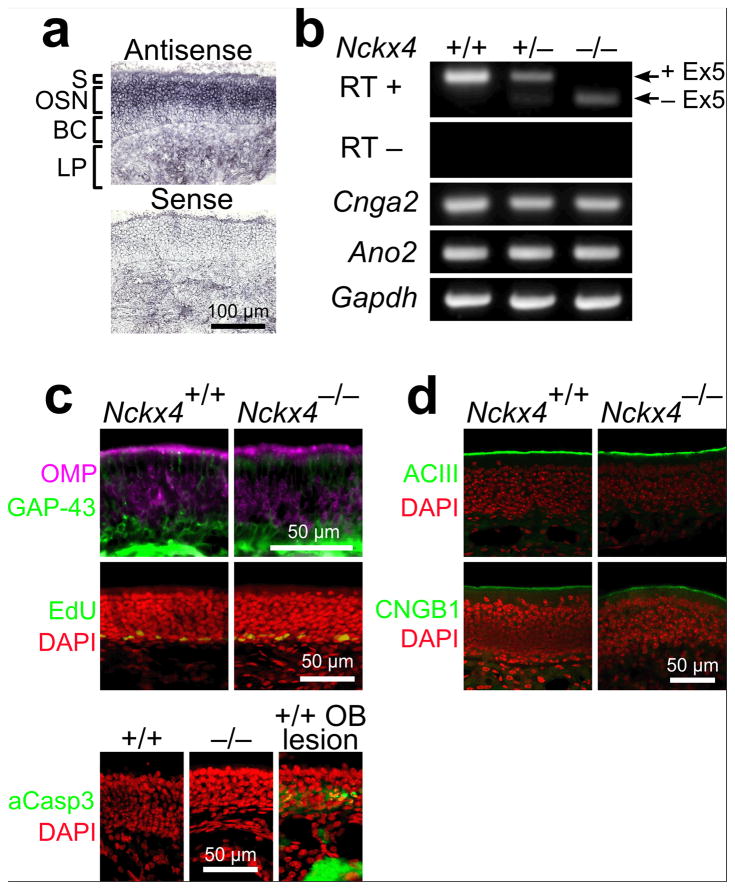

Figure 1. Expression of Nckx4 in the olfactory epithelium and the effects of NCKX4 loss on other olfactory transduction components.

(a) in situ hybridization showing Nckx4 mRNA localization within the mouse olfactory epithelium. S, sustentacular cell layer; OSN, olfactory sensory neuron layer; BC, basal cell layer; LP, lamina propria.

(b) RT – PCR analysis of Nckx4 mRNA in WT, Nckx4+/−, and Nckx4−/− mice. The amplified region flanks the targeted Exon 5. Amplifications of Cnga2, Ano2, and Gapdh transcripts were used as loading controls. See Supplementary Figure 1a – c for details of the gene targeting.

(c) Top panels: immunostaining in olfactory epithelium sections for OMP, a marker of mature OSNs, and GAP – 43, a marker of immature OSNs. Middle panels: labeling by EdU, a nucleotide analog incorporated during mitosis. The nuclei are stained with DAPI. See Supplementary Figure 1d for cell counts. Bottom panels: immunostaining for activated Caspase – 3, an indicator of apoptosis. Fewer than one labeled cell per cryosection was visible for WT and Nckx4−/− mice, whereas labeled cells and axon bundles were apparent in the positive control olfactory epithelium (48 hr after lesioning the olfactory bulb). The nuclei are stained with DAPI.

(d) Immunostaining in olfactory epithelium sections for the olfactory transduction components ACIII (upper panel) and CNGB1b (lower panel). The nuclei are stained with DAPI.

Generation of Nckx4−/− mice

To determine the function of NCKX4 in the olfactory system, we generated mutant mice for the Nckx4 gene. We flanked exon 5, which encodes the first of two ion – exchanger domains, with loxP sequences. Cre recombinase – mediated deletion of this highly conserved exon also causes a frame shift in the remaining transcript sequence, and should therefore cause a functionally null mutation of NCKX4 (Supplementary Fig.1a – c). Straight knockout (Nckx4−/− ) mice, generated by early embryonic Cre expression, were viable. The deletion of exon 5 from Nckx4 transcripts was confirmed by RT PCR analysis from Nckx4−/− olfactory epithelium cDNA (Fig. 1b). We found that loss of NCKX4 did not affect the overall histology of the olfactory epithelium; the relative proportion of mature (olfactory marker protein positive) and immature (GAP – 43 positive) OSNs was unchanged, and no observable difference in OSN proliferation or death was detected as assessed by EdU nucleotide incorporation and activated Caspase – 3, respectively (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1d). Further, the cilial localization of the olfactory transduction components Adenylyl Cyclase III (ACIII) and the B1 subunit of the CNG channel (CNGB1b) were unaltered (Fig. 1d). We also found that the loss of NCKX4 did not affect the overall histology of the olfactory bulb; the total number of glomeruli remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig.1e – f).

Nckx4−/− OSNs exhibit slowed response termination

To analyze the effect of NCKX4 loss on OSN responses, we recorded the electroolfactogram (EOG), an extracellular field potential at the surface of the olfactory epithelium resulting from a summation of individual OSN responses 21, 22. Upon stimulation with a brief (100 msec) odorant pulse, wildtype EOG signals show a rapid activation phase followed by a termination phase. The signals peak within several hundred milliseconds and recover to baseline within seconds 23, 24. The peak amplitudes and activation kinetics of EOG signals reflect the overall sensitivity of OSNs. We found that Nckx4−/− mice had peak EOG amplitudes equal to wildtype mice across all odorant concentrations to two commonly used odorants, heptanal (Fig. 2a, b) and amyl acetate (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We found that the response latency and the time to peak – two metrics for EOG activation kinetics – were unchanged in Nckx4−/− mice (Fig. 2c – e). Similar results were seen for responses to amyl acetate (Supplementary Fig. 2c – e). Because both the response amplitude and the activation kinetics were unaffected in the mutant mice, NCKX4 is unlikely to control the sensitivity of OSNs in response to a single odorant exposure.

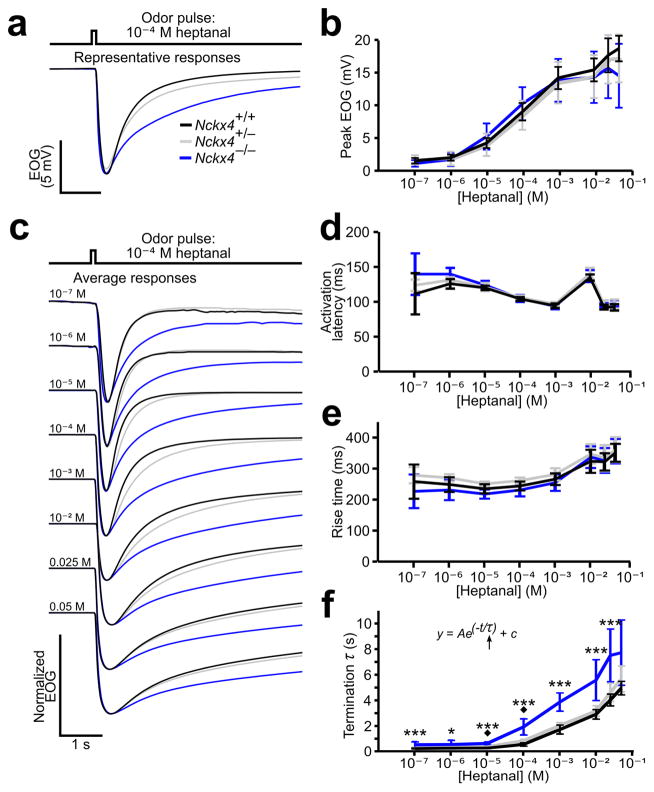

Figure 2. EOG analysis of Nckx4−/−mice.

(a) Representative EOG traces to a 100 – msec pulse of 10 −4 M heptanal. The trace color codes also apply to (b) – (f).

(b) Dose – response relationships of EOG peaks evoked by single, 100 – msec pulses of heptanal. For (b) – (e), WT, n = 9 animals; Nckx4+/−, n = 10; Nckx4−/−, n = 7.

(c) Averaged EOG traces to a 100 – msec pulse of 10 −7 – 0.05 M heptanal. The traces were normalized relative to their peaks to allow comparison of activation and termination kinetics.

(d) EOG activation latency, defined as the time from odor stimulation to 1% peak amplitude.

(e) EOG rise time, defined as the time from 1% to 99% peak amplitude.

(f) EOG termination rates. The termination time constant (τ) is determined by fitting a single exponential function to the termination phase of the EOG trace. For odor concentrations of 10 −4 M and 10 −3 M, n = 16 for WT, n = 19 for Nckx4+/−, and n = 17 for Nckx−/−. For other concentrations, n = 9 for WT, n = 10 for Nckx4+/−, and n = 9 for Nckx4−/−. Error bars, 95% CI. Asterisks indicate P values for WT vs. Nckx4−/−(*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001), and diamonds indicate P values for WT vs. Nckx4+/−(◆, P < 0.05).

While Nckx4−/− mice showed normal sensitivity, they exhibited remarkably slowed termination kinetics of EOG signals (Fig. 2c, f and Supplementary Fig. 2c, f). The time constants (τ) of the EOG termination phase, obtained by fitting the traces to a single exponential equation, were 2 – 3 – fold longer in Nckx4−/− mice as compared to their wildtype littermates. Furthermore, even Nckx4+/− (heterozygous) mice showed significantly prolonged termination to stimulation at odorant concentrations near the EC50 (Fig. 2c, f and Supplementary Fig. 2c, f), suggesting a gene dose – dependence for controlling the response termination rate.

We further analyzed the effect of NCKX4 loss on OSN response termination using single – cell suction recordings. The cell bodies of single dissociated OSNs were sucked into a recording pipette electrode with only the cilia and the dendritic knob exposed to a controlled extracellular solution 17. IBMX (1 mM), a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that elevates cilial cAMP levels, was applied to mimic odorant stimulation and induced rapidly increasing receptor currents in both wildtype and Nckx4−/− OSNs (Fig. 3a). IBMX has been widely used as a surrogate for odorants in OSN single – cell studies due to the low probability of a given OSN being responsive to a given odorant. It has been shown that termination kinetics of OSN response under IMBX stimulation closely resemble that under odorant stimulation 25. In wildtype OSNs, the current in regular Ringer solution recovered to baseline within a short time period after IBMX removal (τRinger = 146 ± 13 msec, mean ± s.e.m.) (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, in Nckx4−/− OSNs, the current recovered over a significantly longer time period (τRinger = 612 ± 53 msec) (Fig. 3a, b), consistent with the EOG data.

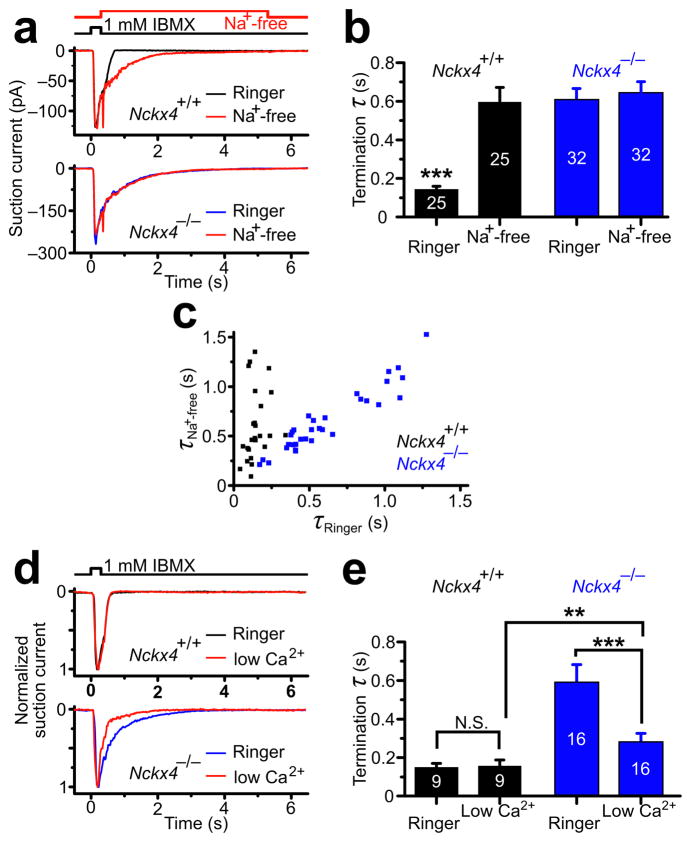

Figure 3. Single–cell analysis of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger–dependent response termination.

(a) Single cell suction electrode recordings from a dissociated WT (top panel) and Nckx4−/− (bottom panel) OSN stimulated with a 0.3–sec pulse of IBMX. For each neuron, two recordings were performed: one with extracellular Ringer’s solution applied throughout the recording time period (black trace for WT, red trace for Nckx4−/−), the other with a Na+–free Ringer’s solution applied during the termination phase of the OSN response (blue traces).

(b) Termination time constants (see Methods). Error bars represent s.e.m. ***, P < 0.001 for WT in Ringer’s solution vs. all other categories. Cell numbers (n) are indicated within the bars.

(c) Plot of the termination time constants in a Na+–free Ringer’s solution vs. in a standard Ringer’s solution for WT (black squares) and Nckx4−/− (red squares) OSNs. Each data point represents a single neuron.

(d and e) Ca2+ dependency of termination rates in Nckx4−/−OSNs. (d) Recordings from a WT (top panel) and Nckx4−/− (bottom panel) OSN stimulated with a 0.3–sec pulse of IBMX. For each neuron, two recordings were performed: one in standard Ringer solution (containing 2 mM Ca2+), the other in low Ca2+ Ringer solution (containing 20 μM Ca2+). The traces were normalized relative to their peaks for comparison of response kinetics.

(e) The termination time constants are plotted for each genotype and condition. Error bars represent s.e.m. N.S., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Cell numbers (n) are indicated within the bars.

Together, our results demonstrate that NCKX4 is necessary for efficient termination of the olfactory signaling cascade.

NCKX4 is the principal olfactory Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

We next examined whether other Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in addition to NCKX4 also regulate OSN response termination. Single – cell suction recording allows precise inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange 17 by switching the extracellular bath solution to a Na+ – free solution (Na+ was replaced equimolarly with choline+, which does not support Na+/Ca2+ exchange) to eliminate all Na+ – dependent Ca2+ extrusion. When wildtype OSNs were switched to a Na+ – free solution immediately after IBMX stimulation, the termination phase was greatly prolonged (τNa – free = 600 ± 71 msec) (Fig. 3a, b) (see also ref. 17). This prolonged current component is due to slowed Ca2+ extrusion and hence prolonged elevated cilial Ca2+ and continued opening of the Ca2+ – activated Cl− channel 14, 26. In contrast, the already prolonged response termination phase of Nckx4−/− OSNs was prolonged further only slightly (albeit significantly, see below) by removal of external Na+ (τNa – free = 646 ± 55 msec) (Fig. 3a, b), suggesting that NCKX4 contributes the vast majority of Na+/Ca2+ exchange to regulate OSN response termination. Because response termination can vary largely between individual OSNs, we plotted τRinger against τNa – free for each OSN. The τNa – Free/τRinger ratio remained quite constant among wildtype OSNs, as well as among Nckx4−/− OSNs (Fig. 3c). We further calculated the τNa – Free/τRinger for each OSN and calculated the average for all wildtype and Nckx4−/− OSNs. Exposure to Na+ – free solution prolonged the response 4.5 ± 0.6 (mean ± s.e.m.) fold in wildtype OSNs but only 1.08 ± 0.03 fold in Nckx4−/− OSNs (P < 0.001). The slight response prolongation upon Na+ removal in Nckx4−/− OSNs was statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicating that a small contribution of other Na+ – dependent Ca2+ extrusion mechanism(s) remains in Nckx4−/− OSNs.

Previously, it has been shown that prolonged Ca2+ transients in OSNs extend activation of the Ca2+ – activated Cl − channel 14, 17, 26. To determine whether the effects of prolonged termination in the Nckx4 −/− OSNs were indeed dependent on Ca2+, we performed single – cell suction electrode recordings in the presence of regular levels of Ca2+ (2 mM) or in low levels of Ca2+ (20 μM) within the extracellular solution. This low concentration of Ca2+ was chosen to minimize Ca2+ influx but not low enough to entirely unblock the CNG channel, which would yield very large Na+ currents and fast cell deterioration. In wildtype OSNs, the termination τ in the regular Ringer solution (τ = 150 ± 20 msec) and in 20 μM extracellular Ca2+ solution (τ =156 ± 30 msec) were comparable (Fig. 3d top, 3e). This result is consistent with the notion that NCKX4 allows an efficient removal of cilial Ca2+ and allows proper rate of termination under a broad range of Ca2+ concentrations. In Nckx4−/− OSNs, the response displayed prolonged termination in comparison to wildtype OSNs both in the regular Ringer solution (τ = 600 ± 90 msec) and in the 20 μM extracellular Ca2+ solutions (τ = 288 ± 40 msec), but the termination τ in the 20 μM Ca2+ solution was significantly shorter than that in the regular Ringer solution (Fig. 3d bottom, 3e). The less severe defect in 20 μM Ca2+ solution in Nckx4−/− OSNs is consistent with the idea that there is a smaller amount of Ca2+ entering the cilia and activating the Ca2+ – activated Cl− channel. Although the amount of Ca2+ entry is reduced in low Ca2+ conditions, NCKX4 is still required to ensure a fast response termination.

Together, these results demonstrate that NCKX4 is necessary for nearly all Na+ – dependent Ca2+ exchange that governs OSN response termination, likely by removing cilial Ca2+ and thus closing the Ca2+ activated Cl− channel.

Nckx4−/− OSNs over – adapt to repeated odorant exposure

Since Ca2+ mediates olfactory adaptation, we hypothesized that NCKX4 is required for OSNs to adapt properly to odor. To test this hypothesis, we performed EOG recordings using a paired – pulse protocol, where the olfactory epithelium was stimulated with two equal 100 – msec odorant pulses. In wildtype mice, the response to the second pulse was significantly reduced relative to the first, signifying that the OSNs were adapted (Fig. 4a – c and Supplementary Fig. 3a – c). In Nckx4−/− mice, the response to the second pulse was even further reduced, indicating that Nckx4−/− mice exhibited enhanced OSN adaptation (Fig. 4a – c and Supplementary Fig. 3a – c). In wildtype mice, the reduction of the second response largely recovered if the interpulse interval was lengthened to 4 sec or beyond, whereas in Nckx4−/− mice significant reduction of the second response was observed even when the interpulse interval was extended to 15 seconds (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f). In addition to an amplitude reduction, another manifestation of adaptation is slower onset kinetics of the EOG signal. Using the metric of onset kinetics, the same phenomenon was seen: OSNs adapt to a greater extent in Nckx4−/− mice relative to wildtype (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 3d). As was seen for the termination kinetics, there was a gene dose dependent effect of NCKX4 on adaptation. Nckx4+/− (heterozygotes) showed an adaptation enhancement compared to wildtype, but much less pronounced than Nckx4−/− (Fig. 4a – d and Supplementary Fig. 3a – d).

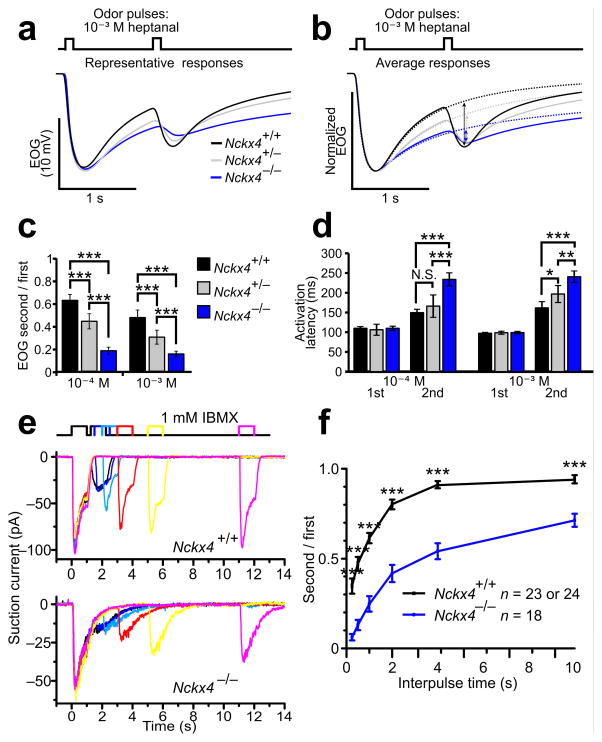

Figure 4. Analysis of adaptation of Nckx4−/−OSNs.

(a–d) EOG analysis of paired–pulse stimulation to heptanal (n = 10 animals for each genotype).

(a) Representative EOG traces.

(b) Solid traces depict averaged EOG recordings to paired–pulse stimulation. Dotted traces depict averaged EOG recordings to a single 100–msec pulse, which were used as the baseline for calculating the net amplitudes (indicated by the vertical bidirectional arrows) of the adapted responses in (c). The traces were normalized relative to the first EOG peak.

(c) Amplitude ratios of the second (adapted) response relative to the first. The amplitude of the second response is calculated by subtracting the single pulse recording from the paired–pulse recording for each animal. Error bars, 95% CI. ***, P < 0.001.

(d) Response latencies. The latency for the second pulse was calculated by subtracting the single pulse recording from the paired–pulse recording for each animal, and calculating the time from the second stimulation to 1% peak of the resulting trace. Error bars, 95% CI. N.S., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

(e and f) Single–cell suction electrode recording analysis. (e) Recordings from a WT (upper panel) and a Nckx4−/− (lower panel) OSN stimulated with paired 1–sec pulses of 1 mM IBMX with varying interpulse intervals.

(f) Average amplitude ratios of the second response relative to the first, plotted against the interpulse time. Error bars represent s.e.m. ***, P < 0.001.

We further characterized the effects of NCKX4 loss on OSN adaptation using single – cell suction pipette recordings. In these experiments, pairs of 1 – sec IBMX (1 mM) stimulations were given with varied interpulse intervals (Fig. 4e). Adaptation was assessed as a reduction in peak current to the second pulse relative to the first pulse. In both wildtype and Nckx4−/− OSNs, the effects of adaptation were strongest when the interpulse interval was shortest and became weaker as the interval was lengthened (Fig. 4f). In Nckx4−/− OSNs, the adapted responses were smaller than wildtype for each tested interval, indicating hyper – adaptation. Wildtype OSNs recovered from adaptation within 4 sec after the first pulse (Fig. 4f). In Nckx4−/− OSNs, however, the effects of adaptation persisted even when the interpulse interval extended beyond 10 sec (Fig. 4f). Together, these results demonstrate that NCKX4 activity moderates the extent of, and supports recovery from, adaptation to repeated stimulation.

Nckx4−/− OSNs fire fewer action potentials when adapted

The odor – evoked receptor potential is further transduced into action potentials within OSNs, which usually occur during the activation phase of the receptor current 17. Given that Nckx4−/− OSNs displayed slower response termination and stronger adaptation, we asked how this altered receptor potential might affect the encoding of action potentials.

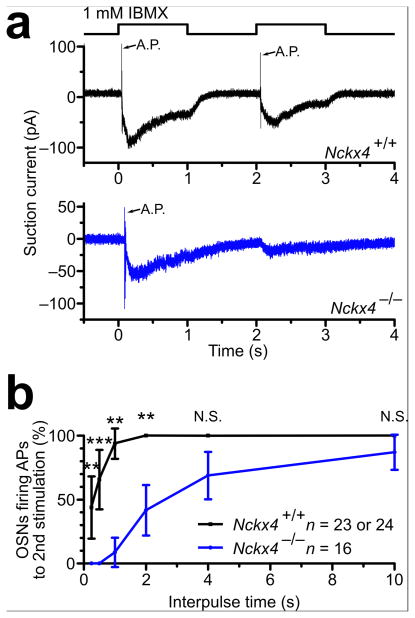

We analyzed the single – cell paired – pulse recordings under a filter setting that allows action currents to be observed (Fig. 5a). Wildtype OSNs quickly regained full ability to generate action potentials when the interpulse period was lengthened; by 0.25 sec after the first stimulation ~45% of OSNs were able to fire action potentials to a second stimulation, and by 2 sec 100% of OSNs fired action potentials (Fig. 5b.) In contrast, Nckx4−/− OSNs did not generate any action potentials to the second stimulation until the interpulse interval reached 1 sec and never gained 100% firing probability even after a 10 sec interval (Fig. 5b). These results demonstrate that NCKX4 poises OSNs to relay odor information under adapting stimulation.

Figure 5. Single–cell analysis of action potential generation in Nckx4−/− OSNs.

(a) Single–cell suction electrode recordings from a Nckx4+/+ (upper panel) and a Nckx4−/− (lower panel) OSN stimulated with paired 1–sec pulses of 1 mM IBMX separated by a 1–sec interval. Traces were filtered with the wide bandwidth of DC – 5000 Hz to monitor action potential firing. Action potential currents (A.P.) are indicated by arrows.

(b) Percentage of OSNs firing action potentials, plotted against the interpulse time. Error bars, 95% CI. N.S., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Nckx4 −/− mice exhibit a reduced ability to locate odors

Given that Nckx4−/− mice displayed a defect in relaying odor information from repeated stimulation, we investigated whether the loss of NCKX4 affects the ability of mice to perceive odors.

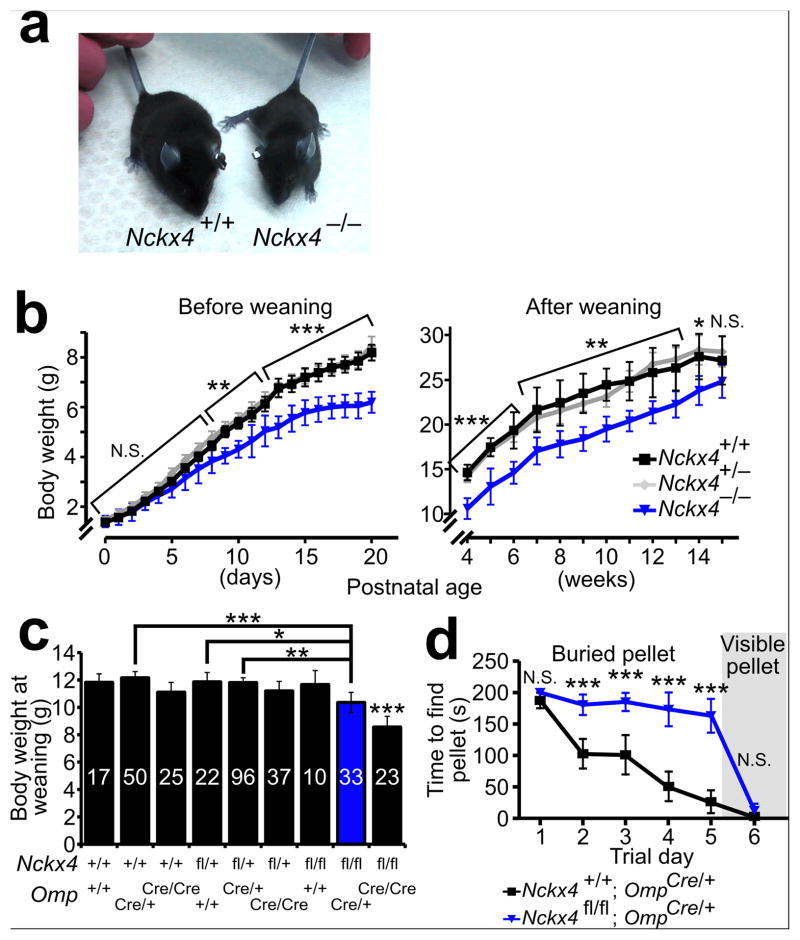

We initially observed that Nckx4−/− mice weighed less than their wildtype littermates (Fig. 6a, b). In mice, olfaction is required for pups to suckle. Reduced body weight is a hallmark characteristic of olfactory defects in mice due to impaired ability to locate the teat: anosmic mice die within the first few postnatal days unless special care is provided 27–29. Nckx4 −/− mice were viable through weaning without special care, thus suggesting that they retain at least some functional olfactory perception. But consistent with an olfactory impairment, they weighed equally to their wildtype littermates at birth and developed defects in body weight during the nursing period. Their body weight defects were most pronounced at the time of weaning (21 – 28 days after birth) and became progressively less pronounced through 4 months of observation (Fig. 6b). To determine whether the body weight reduction was likely due to an olfactory defect rather than pleiotropic effects, we generated olfactory – specific knockout mice, where Nckx4 was conditionally knocked out by the expression of Cre recombinase under the control of the olfactory marker protein (OMP) promoter 30. OMP shows restricted expression in sensory neurons of the main olfactory epithelium and of other olfactory subsystems. EOG recordings of these conditional Nckx4 knockout mice (Nckx4flox/flox; OmpCre/+) showed the similar response defects found in the straight knockout (Nckx4−/−) mice (data not shown). We found that the reduced body weight phenotype persisted in these conditional knockout mice (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6. Effects of NCKX4 loss on olfactory–mediated behaviors.

(a) Body size of a Nckx4−/− mouse relative to a Nckx4+/+ mouse at 24 days postnatal age.

(b) Timecourse of average body weights for Nckx4+/+ (n = 10–54), Nckx4+/− (n = 17–85), and Nckx4−/− (n = 5–31) mice before (left) and after (right) weaning. Error bars, 95% CI. Statistical significance for Nckx4+/+ vs. Nckx4−/− is indicated over each timepoint: N.S., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

(c) Average body weights for mice of all combinations of Nckx4 (+ or flox) and Omp (+ or Cre) alleles at 24 days postnatal age. The red color highlights the olfactory conditional Nckx4 knockout (Nckx4flox/flox;OmpCre/+). Error bars, 95% CI. All genotypes weighed significantly more than the double knockout (P < 0.001). All other pairwise P–values that are less than 0.05 are also indicated: *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01; ***, P <0.001. Mouse numbers (n) are indicated within the bars.

(d) Buried Food Pellet Test for Nckx4+/+;OmpCre/+ and Nckx4flox/flox;OmpCre/+ mice (n = 20 mice per genotype). The average time to locate the food pellet is plotted against the trial day. On day 6, the pellet was left on the surface of the bedding to be visible to the mouse. Error bars, 95% CI. N.S., not significant; ***, P < 0.001. See Supplementary Movie 1 for a video of both genotypes’ behavior in this task.

To further test whether slower response termination and enhanced adaptation of OSNs affect the ability of mice to perceive odors, we conducted the Buried Food Pellet Test. In this test, food – restricted wildtype mice learned to rapidly locate a buried food pellet, showing daily performance improvements through 5 trial days (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Movie 1). In contrast, most olfactory conditional Nckx4 knockout mice failed to locate the buried pellet within the allotted 200 seconds (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Movie 1). Over the course of 5 trial days, these conditional Nckx4 knockout mice showed no significant improvements in their ability to locate the pellet. Importantly, on trial day 6, when the food pellet was made visible by placing it on the surface, both wildtype and olfactory conditional Nckx4 knockout mice rapidly located the pellet within a similar time frame, controlling for possible secondary locomotor, motivational, or cognitive defects. These results demonstrate that NCKX4, which confers rapid olfactory response termination and moderates OSN adaptation, is necessary for mice to optimally locate odorous sources.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified NCKX4 to be the principal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to allow rapid response termination and proper adaptation of the OSN, presumably by mediating Ca2+ extrusion from OSN cilia. Furthermore, we showed that by modulating the peripheral olfactory response, NCKX4 proves critical for an animal to accurately encode and react to olfactory stimuli in the environment.

NCKX4 is a component of the olfactory transduction pathway

NCKX4 (SLC24a4) was initially chosen as the leading candidate for the olfactory Na+/Ca2+ exchanger based on our previous proteomic analysis aiming to identify novel olfactory transduction components 18. Historically, molecular identification of many olfactory transduction components was first deduced by the abundance and localization of mRNAs through the use of either cDNA library screening 31–35 or PCR – based approaches 36–38. Many of these components were later functionally confirmed by gene knockout experiments in mice 23, 28, 29, 39–41. By directly detecting the proteins at the site of their predicted function, cilial membrane proteomics have proven fruitful in identifying the remaining long – sought olfactory transduction components, including the olfactory Ca2+ – activated Cl − channel ANO218 and, here, the olfactory Na+/Ca2+ exchanger NCKX4 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The Nckx4 gene was first cloned from human and mouse brains 42, and the NCKX4 protein was demonstrated to display K+ – dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity 42, 43. However, no specific physiological role has been definitively attributed to NCKX4. Through loss – of – function analysis, this current study defines a physiological role for NCKX4 in olfactory transduction. We showed that NCKX4 is required to allow rapid olfactory termination and to prevent over adaptation to repeated stimulation. These effects of NCKX4 are most likely due to the Ca2+ transporter activity of NCKX4. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that NCKX4 may have additional functions in the olfactory system. Future technological improvements that allow imaging of Ca2+ dynamics within mammalian olfactory cilia will further clarify the precise function of NCKX4 in olfactory transduction.

It has been suggested that active extrusion of Ca2+ from olfactory cilia is mediated by both Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases (PMCAs). Na+/Ca2+ exchangers have been favored as a mechanism for extruding Ca2+ from OSNs for olfactory transduction 13, 14, 17. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers have a much greater capacity to extrude Ca2+ than PMCAs 44, and are thus better suited for rapidly reducing intracilial Ca2+ to fulfill the need for rapid OSN response kinetics. In comparison to NCX, NCKX proteins harness additional driving force for Ca2+ by coupling the transport of an additional Na+ and a K+, which can maintain the driving force for Ca2+ removal even at depolarized membrane potentials and can allow the reduction of Ca2+ to nanomolar levels 45, 46. NCKX4 is therefore well suited for its role in regulating olfactory responses.

NCKX4 regulates the olfactory response

The loss of NCKX4 could influence the sensitivity of the OSN response positively by increasing Ca2+ – activated Cl − current and negatively by increasing PDE1C activity 23, increasing inhibition of the CNG channel, and loss of the electrogenic effect 47. However, we found that both amplitude and activation kinetics of the EOG response were, surprisingly, not changed in Nckx4−/− mice (Fig. 2). This unchanged sensitivity in Nckx4−/− OSNs could result from a cancellation of these positive and negative effects. Alternatively, NCKX4 – mediated Ca2+ extrusion might not affect these mechanisms until after the response has peaked, so that the loss of NCKX4 does not alter response sensitivity to a brief odorant exposure.

A pronounced effect of NCKX4 loss is stronger OSN adaptation (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). This result provides in vivo demonstration that Ca2+ mediates olfactory adaptation. While it is thought that Ca2+ – mediated adaptation is via negative feedback of Ca2+ on olfactory signaling components, the exact molecular target(s) of this feedback remain to be determined 24.

The most pronounced effect of NCKX4 loss on the olfactory response is a prolonged termination phase (Fig. 2). Loss of one Nckx4 allele (Nckx4+/− ) caused a mild prolongation, whereas loss of both Nckx4 alleles (Nckx4 −/− ) caused a severe prolongation. Termination of the OSN response requires the closure of both the CNG channel and the ANO2 channel. Degradation of cAMP by phosphodiesterase 1C (PDE1C), which leads to closure of the CNG channel, was once thought to determine the rate of response termination. However, Pde1c −/− mice do not show a prolonged olfactory response, indicating that regulation of cAMP dynamics does not dominate the rate of response termination 23. The slower termination seen in Nckx4 −/− mice could be best attributed to a slower clearance of Ca2+ from OSN cilia, and thus prolonged activation of the Cl − current (however, see ref 48). Together, these studies establish that regulation of Ca2+ dynamics, rather than degradation of cAMP, plays the leading role in determining the rate of OSN response termination.

Olfactory behavior requires controlled response kinetics

It has always been assumed that rapid termination of peripheral sensory responses is necessary to prepare animals to sense recurring stimulation. However, in the olfactory system this assumption has never been fully testable due to the fact that most mutations in core and modulatory signal transduction components cause either complete loss 28, 29, 41 or severe reductions in sensitivity of the OSN response 23, 39, 49. This loss or reduction of OSN sensitivity precluded investigations and confounded interpretations of whether alterations in peripheral response properties affect the ability of animals to encode and react to sensory stimuli.

Ncxk4 knockout mice, which display defects in response termination and adaptation but have unchanged sensitivity, provided a unique opportunity to address this question. We found that defects in termination and adaptation of the OSN receptor potential led to a defect in encoding action potentials (Fig. 5). Further, olfactory – specific Nckx4 knockout mice displayed lower body weights, which is consistent with a nursing defect due to impaired olfactory function (Fig. 6c). Finally, these mice were less efficient at performing a food – finding task (Fig. 6d). Thus, by identifying NCKX4 as a regulator of OSN responses, these studies suggest that rapid response termination and proper regulation of adaptation in OSNs are essential to properly encode and react to olfactory stimuli.

METHODS

Animals

For all experiments involving mice, the animals were handled and euthanized in accordance with methods approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of each applicable institution. Unless otherwise noted, all analyses involving animals were performed on adult (> 40 day – old) mice.

Generation of Nckx4 knockout mice

The 85 bp exon 5 of Nckx4 gene on chromosome 12 was selected to be flanked by loxP sites, with a 4.0 kb fragment upstream and a 5.2 kb fragment downstream of this exon used as homologous arms for ES cell gene targeting. pBluescript KS (Clontech) was PCR amplified with primers ACTGGGCCTGGTCACAGGCCTGTATCTGAAGGGAGAGGTAACAGAGGTGTTACAACGTCGTGACTGGGAA and CTCAAAAAATAAGGGGAAACACAATTGAGGAAACACTGGATAGAGAACTCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC, which contain 50 bp homologous arms (underlined) for the Nckx4 genomic DNA, and the resulting PCR product was used to retrieve the genomic DNA from BAC RP135 – I1 (Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute BACPAC Resource Center) in SW102 cells using a cell – based recombineering procedure 50. A loxP – Neomycin Resistance Cassette – loxP sequence amplified from pL452 with primers CGGTGCCAGGCTCAGATCCACACTGTGTCACTGAGAGCTTTCTGCCATCCGCCCAATTCCGATCATATTC and AGGCAACTGGGTTGTGACAAGGGAGGGGAGCACGCAGCCCCTGGGCAGGTCCGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGA, which contain 50 bp homologous targeting arms, was recombineered 5′ to Exon 5 within SW102 cells. The neomycin cassette was removed by arabinose – induced Cre recombinase expression in SW106 cells, leaving a single loxP sequence upstream of Exon 5. A Frt Neomycin Resistance Cassette – Frt – loxP sequence amplified from pL451 with primers ATGCAGAGAGAGCCAGGGCTGACTGCCCAGGGCAGTGGGGCATTTACCAGCTTGATATCGAATTCCGAAG and TGTCCCTCTGACCCCCTTGGGTTTACAAGTGAGGAAATGGAGACTTGGAGCTAATAA CTTCGTATAGCATAC, which contain 50 bp homologous targeting arms, was recombineered 3′ to Exon 5 within SW102 cells. The targeting vector was assessed by extensive restriction digestion and sequencing analysis.

ES cell gene targeting was performed in a 129s6 SvEv ES cell line (MC1 line, Johns Hopkins University transgenic core). 384 individual clones were screened for homologous recombination using a pgk promoter – specific primer CTACTTCCATTTGTCACGTCCTG and upstream primer CTCACATAGGTACTGCTCAACAGAC outside of the 5′ arm. Two ES clones were confirmed with homologous combination: 1A12 and 2B2. Each ES cell clone was injected into blastocysts (JHU transgenic core). The chimeras with highest fraction of agouti fur from both parent ES cell clones were mated to C57BL/6 females (Jackson), and germline transmission was determined in the F1 generation by the presence of agouti fur color and positive PCR for the mutant allele. Only ES clone 2B2 resulted in germline transmission. For germline (straight) knockouts, the F1 heterozygote was mated to the early embryonically – expressing Cre recombinase mouse line B6.FVB – Tg(EIIa – cre)C5379Lmgd/J (The Jackson Laboratory), the F2 mice were back – crossed to C57BL/6 to eliminate the Cre allele, and then the F3 mice were inbred to obtain homozygotes. For the OSN – specific conditional knockout mice, the F1 was mated with the ubiquitously – expressing Flippase line 129S4/SvJaeSor – Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/J (The Jackson Laboratory), the F2 mice were back – crossed to C57BL/6 to eliminate the flp, the F3 mice were mated with mouse line B6;129P2 – Omptm4(cre)Mom/MomJ (OmpCre) (The Jackson Laboratory), and then the F4 mice were inbred to obtain 9 separate genotypes, including Nckx4flox/flox;OmpCre/+, the OSN – specific conditional line. Primers AAAGGAAATGAAGAGAAGGC (AS67), and TCATCTCATAAGAAGCCCAG (AS68), which span the floxed exon 5 region, were used to genotype the Nckx4 allele, with expected band sizes being 615 bp for wildtype, 823 bp for the floxed exon (Supplementary Fig. 1b), and 450 bp for the knocked – out exon (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

RT – PCR analysis of olfactory epithelium RNA

Total olfactory epithelial RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was made by reverse transcription of total RNA using random decamer primers (Ambion). To amplify each specific gene, lower PCR cycles were used to preserve semi – quantitative information regarding relative transcript abundance. The primers used for Nckx4 were TCCAACAAAGAACGACAGCA and GTTCCTACACCGACATCTCC (245 bp product with Exon 5, 160 bp without Exon 5), for Cnga2 were TGCCGTAAGGGGGACATTG and ACAGCACTTCTAACTCCTGGGGTC (596 bp product), for Ano2 were AGTCATCTGTTTGACAATCCAG and CACTCTCCTTTAACAGTTTCTC (198 bp product in olfactory tissue), and for Gapdh were GGGTGGTGCCAAAAGGGTC and GGAGTTGCTGTTGAAGTCACA (223 bp product).

In situ hybridization

Nckx4 probe template was PCR amplified from mouse olfactory epithelial cDNA with primers TACTACTCGAGCTCTGTCATTGTGCTCATTGCG and AGATGGCGGCCGCCGTGAACACCCACTTAGCCTTGTC, and cloned into pBluescript KS(+) (Clontech). This 655 bp fragment of Nckx4 was chosen to minimize cross – reactivity of the probe with other Na+/Ca2+ genes. Antisense and sense digoxigenin – labeled RNA probes were then generated by transcription from the T3 and T7 promoters. The in situ hybridization was performed on 14 μm thick OE cyrosections.

Immunohistochemistry

The olfactory epithelium (OE) and olfactory bulb tissues were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde at 4°C followed by cryoprotection in 30% (wt/vol) sucrose. The tissues were cut into 18 μm – thick (OE), 20 μm – thick (olfactory bulb) coronal cryosections. Sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X – 100 and 1% (vol/vol) goat serum. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti – OMP, 1:1000 (chicken antibody, provided by Q. Gong); anti – Gap43, 1:500 (Chemicon MAB347); anti – ACIII (Chemicon AB3403), 1:200; 1:500; anti – CNGB1b 24, 1:300; anti – NCAM (DSHB, 5B8 supernatant), 1:1. After washing, the sections were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs) containing DAPI stain and imaged. To assess cell death, 30 μm – thick sections were stained with anti – cleaved Caspase – 3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology #9661) at a dilution of 1:200 as the primary antibody. The activated Caspase – 3 staining was performed on 28 day – old mice.

Cell proliferation assay

Mice were injected with 125 μg 5 – ethynyl – 2′ deoxyuridine (EdU) (Invitrogen) every 2 hours for 12 hours (7 injections total). Two hours after the final injection, the tissue was fixed and cryoprotected as described above. Olfactory epithelium tissue was cut into 30 μm sections. EdU – labeled cells were detected using Click – iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen). Sections were mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI stain and imaged. The EdU labeling was performed on 28 day – old mice.

EOG recording

Mouse EOG recordings were performed as described 21. Adult mice, aged 3 – 5 months, were used. Heptanal and amyl acetate and were diluted in DMSO to result in a 50x stock solution series. The stock solutions were then diluted to 1x in water to 5 ml final volume in a sealed 60 ml glass bottle to generate vapor phase odorant. EOGs were recorded from a consistent position on turbinate IIB. One set of mice was used in single – pulse dose – response recordings. Another set of mice was used for single, paired – pulse, and extended – pulse recordings at 10 −4 and 10 −3 M odorant concentrations. The data was collected and analyzed using AxoGraph Software (Axon Instruments) at a sampling rate of 1 KHz. All recordings were digitally filtered at 25 Hz prior to analysis. For measuring termination time constants, the time windows used for the fit were 2.5 – 4 sec for 10 −7 M odorant, 2.4 – 4 sec for 10 −6 M, 2.4 – 4.5 sec for 10 −5 M, 2.4 – 10 sec for 10 −4 M, 2.4 – 15 s for 10 −3 M, and 2.4 – 20 sec for 10 −2 – 0.05 M.

Single – cell suction recording and analysis

The suction pipette technique 17 was used to perform single OSN recordings. The cell body of an isolated OSN was sucked into the tip of a recording pipette, leaving the cilia and the dendritic knob (but not the cell body) accessible for solution changes. Solution exchanges were achieved by transferring the tip of the recording pipette across the interface of neighboring streams of solution using the Perfusion Fast – Step SF – 77B solution changer (Warner Instruments). As the intracellular voltage is free to vary in this recording configuration, the recorded current has two components: fast biphasic current transients resembling action potentials and the slower receptor current. Currents were recorded with a Warner PC – 501A patch clamp amplifier, digitized using a Mikro1401 and Signal acquisition software (Cambridge Electronic Design). Suction currents were sampled at 10 KHz. The recorded signals were filtered DC – 50 Hz to display the suction current alone, and filtered DC – 5000 Hz to display action potential currents. Mammalian Ringer solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 0.01 EDTA, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose. The pH was adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Experiments were performed at 37°C.

The decay time constant was calculated by integrating the current generated after cessation of IBMX exposure. This overall charge was normalized to the current at the cessation of IBMX exposure. The obtained time constant is mathematically equivalent to the time constant obtained from a single exponential decay (in cases that the current decay follows a single exponential decay).

Body mass measurement

Mouse pups were weighed daily to an accuracy of 10 mg. After weaning, mice were weighed weekly to an accuracy of 100 mg. All weight measurements were carried out at the same time of day.

Buried food pellet test

The Buried Food Pellet Test was performed using adult Nckx4+/+;OmpCre/+ (n = 20) and Nckx4flox/flox;OmpCre/+ (n = 20) mice at Zietgeber Time 7 – 12. All animals were housed individually with wood – shavings bedding for the duration of the experiment with free access to water. Mice were deprived of food for 24 h prior to the experiment and subsequently restricted to 2.5 g of Rodent Chow (Harlan Teklad) per day. The testing chambers were clean cages of dimensions 30 × 19 × 13 (L× W × H, in cm) filled with ~800 cm3 of wood – shavings bedding. Two 40 – 60 mg pieces of Oreo Cookies (Nabisco) were buried just below the surface of the bedding in the following manner: The cage area was designated into halves length – wise. One cookie piece was buried in a randomized location within the left half, the other within the right half. Including two pellets in the experiment reduced the effective search area by half and better controlled for variance in the depth that the pellet was buried. In a single trial, a mouse was placed in the center of the cage and was given 200 sec to locate either of the two pellets. Latency in finding the first pellet was recorded when the mouse touched the pellet. After the mouse located the first pellet, they were allowed to consume the cookie, and were given another 200 sec to locate the second pellet. If a mouse failed to find a pellet within the allotted 200 sec, the cookie pellet was exposed and presented to the mouse for subsequent consumption. After the trial, each mouse was returned to its respective cage. Mice were tested in a single trial per day for 5 consecutive days. The testing order of the animals was randomized for each day. Fresh bedding was used for each mouse, each day.

Statistical analyses

For the comparison of percentage of OSNs firing action potentials (Fig. 5b), the P – values were calculated using a Chi – square test. For all other comparisons that only involved WT mice vs. Nckx4−/− mice, P – values were calculated with Student’s t – test at each odorant concentration or timepoint. When three or more genotypes were compared, pairwise P – values were calculated with the Tukey – Kramer ANOVA post – test at each odorant concentration or timepoint. Statistical analyses were performed using R (http://www.r-project.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Bozza for providing the OMP – Cre mouse line. We thank K. Cunningham, K. Cygnar, D. Fambrough, S. Hattar, R. Kuruvilla, D. Luo, and F. Margolis for suggestions and discussions. We also thank members of the Hattar – Kuruvilla – Zhao mouse tri – lab of the Johns Hopkins Department of Biology for discussions. This research is supported by NIH DC007395, a Morley Kare Fellowship (to J.R.) and the Monell Chemical Senses Center. A.B.S. is currently a Department of Energy-Biosciences Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors do not declare any competing interests.

A.B.S and H.Z. designed and performed the initial experiments to identify NCKX4. A.B.S generated the targeted deletion of Nckx4 in mice and designed and conducted the in situ hybridizations, immunostaining, EOG analyses, and behavioral analyses. S.T. set up crosses and weighed the conditional knockout mice, performed the OB NCAM staining, and performed the adaptation time course EOGs. J.R. designed and performed the single cell – recordings. M.D. performed the Ca2+ – free single – cell recordings. C.M.W. analyzed glomerular formation using anti – OR antibodies (data not shown). A.B.S., H.Z., and J.R. wrote the initial manuscript draft. All authors discussed the results and the contents of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fain GL, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Koutalos Y. Adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:117–151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleene SJ. The electrochemical basis of odor transduction in vertebrate olfactory cilia. Chem Senses. 2008;33:839–859. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjn048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaupp UB. Olfactory signalling in vertebrates and insects: differences and commonalities. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrn2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reisert J, Lai J, Yau KW, Bradley J. Mechanism of the excitatory Cl- response in mouse olfactory receptor neurons. Neuron. 2005;45:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe G, Gold GH. Nonlinear amplification by calcium-dependent chloride channels in olfactory receptor cells. Nature. 1993;366:283–286. doi: 10.1038/366283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleene SJ. High-gain, low-noise amplification in olfactory transduction. Biophys J. 1997;73:1110–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zufall F, Leinders-Zufall T. The cellular and molecular basis of odor adaptation. Chem Senses. 2000;25:473–481. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menco BP. Ciliated and microvillous structures of rat olfactory and nasal respiratory epithelia. A study using ultra-rapid cryo-fixation followed by freeze-substitution or freeze-etching. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;235:225–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00217846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyrski M, et al. Sodium/calcium exchanger expression in the mouse and rat olfactory systems. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:944–958. doi: 10.1002/cne.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lytton J. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers: three mammalian gene families control Ca2+ transport. Biochem J. 2007;406:365–382. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnetkamp PP. Calcium homeostasis in vertebrate retinal rod outer segments. Cell Calcium. 1995;18:322–330. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, et al. Light activation, adaptation, and cell survival functions of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger CalX. Neuron. 2005;45:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antolin S, Matthews HR. The effect of external sodium concentration on sodium-calcium exchange in frog olfactory receptor cells. J Physiol. 2007;581:495–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.131094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisert J, Matthews HR. Na+-dependent Ca2+ extrusion governs response recovery in frog olfactory receptor cells. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:529–535. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.5.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noe J, Tareilus E, Boekhoff I, Breer H. Sodium/calcium exchanger in rat olfactory neurons. Neurochem Int. 1997;30:523–531. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung A, Lischka FW, Engel J, Schild D. Sodium/calcium exchanger in olfactory receptor neurones of Xenopus laevis. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1741–1744. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199409080-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reisert J, Matthews HR. Response properties of isolated mouse olfactory receptor cells. J Physiol. 2001;530:113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0113m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephan AB, et al. ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11776–11781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903304106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su AI, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sammeta N, Yu TT, Bose SC, McClintock TS. Mouse olfactory sensory neurons express 10,000 genes. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:1138–1156. doi: 10.1002/cne.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cygnar KD, Stephan AB, Zhao H. Analyzing responses of mouse olfactory sensory neurons using the air-phase electroolfactogram recording. J Vis Exp. 2010;37 doi: 10.3791/1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott JW, Scott-Johnson PE. The electroolfactogram: a review of its history and uses. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:152–160. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cygnar KD, Zhao H. Phosphodiesterase 1C is dispensable for rapid response termination of olfactory sensory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:454–462. doi: 10.1038/nn.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y, et al. Olfactory CNG channel desensitization by Ca2+/CaM via the B1b subunit affects response termination but not sensitivity to recurring stimulation. Neuron. 2008;58:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reisert J, Yau KW, Margolis FL. Olfactory marker protein modulates the cAMP kinetics of the odour-induced response in cilia of mouse olfactory receptor neurons. J Physiol. 2007;585:731–740. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reisert J, Matthews HR. Simultaneous recording of receptor current and intraciliary Ca2+ concentration in salamander olfactory receptor cells. J Physiol. 2001;535:637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Reed RR. X inactivation of the OCNC1 channel gene reveals a role for activity-dependent competition in the olfactory system. Cell. 2001;104:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong ST, et al. Disruption of the type III adenylyl cyclase gene leads to peripheral and behavioral anosmia in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2000;27:487–497. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belluscio L, Gold GH, Nemes A, Axel R. Mice deficient in G(olf) are anosmic. Neuron. 1998;20:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Ishii T, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P. Odorant receptor gene choice is reset by nuclear transfer from mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Nature. 2004;428:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nature02433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan C, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase enriched in olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9677–9681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sautter A, Zong X, Hofmann F, Biel M. An isoform of the rod photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channel beta subunit expressed in olfactory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4696–4701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones DT, Reed RR. Golf: an olfactory neuron specific-G protein involved in odorant signal transduction. Science. 1989;244:790–795. doi: 10.1126/science.2499043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhallan RS, Yau KW, Schrader KA, Reed RR. Primary structure and functional expression of a cyclic nucleotide-activated channel from olfactory neurons. Nature. 1990;347:184–187. doi: 10.1038/347184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakalyar HA, Reed RR. Identification of a specialized adenylyl cyclase that may mediate odorant detection. Science. 1990;250:1403–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.2255909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liman ER, Buck LB. A second subunit of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel confers high sensitivity to cAMP. Neuron. 1994;13:611–621. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley J, Li J, Davidson N, Lester HA, Zinn K. Heteromeric olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: a subunit that confers increased sensitivity to cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8890–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munger SD, et al. Central role of the CNGA4 channel subunit in Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent odor adaptation. Science. 2001;294:2172–2175. doi: 10.1126/science.1063224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michalakis S, et al. Loss of CNGB1 protein leads to olfactory dysfunction and subciliary cyclic nucleotide-gated channel trapping. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35156–35166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606409200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunet LJ, Gold GH, Ngai J. General anosmia caused by a targeted disruption of the mouse olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Neuron. 1996;17:681–693. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li XF, Kraev AS, Lytton J. Molecular cloning of a fourth member of the potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger gene family, NCKX4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48410–48417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visser F, Valsecchi V, Annunziato L, Lytton J. Exchangers NCKX2, NCKX3, and NCKX4: identification of Thr-551 as a key residue in defining the apparent K(+) affinity of NCKX2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4453–4462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:763–854. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnetkamp PP, Basu DK, Szerencsei RT. The stoichiometry of Na-Ca+K exchange in rod outer segments isolated from bovine retinas. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;639:10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altimimi HF, Schnetkamp PP. Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers (NCKX): functional properties and physiological roles. Channels (Austin) 2007;1:62–69. doi: 10.4161/chan.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danaceau JP, Lucero MT. Electrogenic Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchange. A novel amplification step in squid olfactory transduction. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:759–768. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.6.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billig GM, Pal B, Fidzinski P, Jentsch TJ. Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) currents are dispensable for olfaction. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nn.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buiakova OI, et al. Olfactory marker protein (OMP) gene deletion causes altered physiological activity of olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9858–9863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 2003;13:476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.