Abstract

To search for optimal immunization conditions for inducing protective immunity against upper genital tract pathologies caused by chlamydial intravaginal infection, we compared protection efficacy in mice immunized intranasally or intramuscularly with live or inactivated C. muridarum organisms. Mice immunized intranasally with live organisms developed strong protection against both vaginal shedding of infectious organisms and upper genital tract pathologies. The protection correlated with a robust antigen-specific T cell response with high IFNγ but low IL-17. Although a significant level of IL-5 was also detected, these mice maintained an overall Th1-dorminant immunity following immunization and challenge infection. On the contrary, mice immunized intranasally with inactivated organisms or intramuscularly with live or inactivated organisms produced high levels of IL-17 and still developed significant upper genital tract pathologies. High titers of antibodies against chlamydial secretion antigens were detected only in mice immunized intranasally with live organisms but not mice in other groups, suggesting that the intranasally inoculated live organisms were able to undergo replication and immune responses to the chlamydial secretion proteins may contribute to protective immunity. These observations have provided important information on how to develop subunit vaccines for inducing protective immunity against urogenital infection with C. trachomatis organisms.

Keywords: Chlamydia muridarum, live infection, pathology, IFNγ & IL-17, secretion proteins

1. Introduction

Urogenital tract infection with C. trachomatis is a leading cause of sexually transmitted infection worldwide [1, 2], which, if untreated, can lead to severe complications characterized with tubal inflammatory complications, including ectopic pregnancy and infertility [3, 4]. The chlamydial intracellular replication is thought to significantly contribute to the C. trachomatis-induced inflammatory pathologies [5, 6]. Chlamydial replication cycle starts with the invasion of an epithelial cell with a chlamydial infectious elementary body (EB). The internalized EB differentiates into a noninfectious but metabolically active reticulate body (RB). The RB makes new proteins not only for the organism multiplication but also for secretion into inclusion lumen, inclusion membrane [7, 8] and host cell cytosol [9–13]. After replication, the progeny RBs differentiate back into EBs for spreading to near-by cells. The C. trachomatis secretion of proteins into the host cell cytosol seems to be essential for the organisms to productively complete the existing developmental cycle and ensure a successful start of subsequent infection cycles. Some of the secreted proteins are preexisting proteins associated with the infectious EBs [14–16] while others are newly made during infection [17]. Interestingly, not all proteins newly synthesized during infection are incorporated into the infectious EBs. For example, the chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF was detected in the infected cell culture but not in the purified EB organisms [17]. This type of proteins has been defined as infection-dependent secretion proteins. Animals infected with live organisms can develop robust antibody responses to the infection-dependent secretion antigens while animals immunized with inactivated chlamydial organisms failed to do so [17]. Thus, detection of antibodies to the infection-dependent secretion antigens can be used to monitor expression of the secretion antigens in animals and humans [18]. Importantly, the infection-dependent secretion antigen CPAF has been shown to induce protective immunity in mice [19, 20].

A major clinical challenge of C. trachomatis infection is that most acutely infected individuals don’t seek treatment due to lack of obvious symptoms, thus potentially developing serious tubal complications. A long-term solution to this challenge is vaccination so that urogenital exposure to C. trachomatis organisms can no longer induce tubal pathologies. However, there is still no licensed C. trachomatis vaccine despite the extensive efforts made in the past half century. Nevertheless, the failed human trachoma trials more than 50 years ago [21, 22] and the immunological studies in the past half-century [2, 23–29] suggested that a subunit vaccine strategy is both necessary and feasible. Thus, identifying vaccine candidate antigens and optimizing immunization routes to induce protective immunity have been the major focuses of chlamydial immunological studies.

The C. muridarum intravaginal infection mouse model has been extensively used to study C. trachomatis pathogenesis and immunology [24, 30–36]. C. muridarum is a newly classified species and used to be called mouse pneumonitis agent (designated as MoPn), a murine biovar of C. trachomatis. Although the C. muridarum organisms cause no known diseases in humans, mice are highly susceptible to C. muridarum infection and upper genital tract pathologies induced by intravaginal infection with C. muridarum in mice closely resemble those in the human genital tracts induced by C. trachomatis [37, 38]. With this mouse model, it has been demonstrated that the CD4+ T helper cell (Th1)-dominant and IFNγ-dependent immunity is a major host protective determinant for controlling chlamydial infection [39] although antibodies and other immune components may also contribute to host resistance to chlamydial infection [40–42].

In the current study, we compared protection efficacy in mice intranasally or intramuscularly immunized with live or inactivated C. muridarum organisms. The strongest protection was only observed in mice intranasally immunized with live organisms and the protection was accompanied with a robust antigen-specific T cell response of high IFNγ but low IL-17 and also high titers of antibody responses to infection-dependent chlamydial secretion proteins TC0248 (CPAF; ref:[17]), TC0177 (homolog of the secreted hypothetical protein CT795, ref: [43]) and TC0396 (IncA, ref: [44]). On the contrary, mice immunized intranasally with dead organisms or intramuscularly with dead or live organisms produced high levels of IL-17 but lacked antibodies to the infection-dependent chlamydial secretion proteins. Consequently, these mice still developed significant upper genital tract pathologies upon intravaginal infection with C. muridarum organisms. These observations have provided important information for developing subunit vaccines to induce protection against upper genital tract pathologies caused by C. trachomatis infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse immunization and urogenital tract infection

Chlamydia muridarum Nigg strain (also called MoPn) organisms were grown in HeLa cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA 20108), purified and titrated as described previously [36, 45]. Inactivation of EBs was carried out by exposure of EB preps to UV light from a G36T5L/C UV lamp (Universal light source, San Francisco, CA) at a distance of 5 cm for 45 min at room temperature. To ensure that the UV-treated EB (UV-EB) organisms are completely inactivated, each UV-EB prep was tested on HeLa cells and no inclusion-forming unit (IFU) was recovered after incubation for 24h or 36 h (data not shown). Aliquots of live and UV-EB organisms were stored at −80°C till use.

Female Balb/c mice were purchased at the age of 3 to 4 weeks old from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA) and divided into 6 different groups with 20 to 40 mice in each group for immunization. The first 3 groups were immunized intranasally (i.n.) with 50 IFUs of live or 1 X 106 IFUs of UV-light inactivated C. muridarum EBs (UV-EBs) or PBS each in a total volume of 20μl that contains 10μg CpG except for the live EB group. The rest 3 groups were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with 30μg GST protein or 1 X 105 IFUs of UV-EBs or live EBs plus 10μg CpG in a total volume of 50μl emulsified in equal volume of IFA (incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant). The intranasal immunization with live EBs was given only once at the beginning of the immunization schedule. For the rest 5 groups, the immunization was administered 3 times, on day 0, day 20 and day 30 respectively. The CpG with a sequence of 5′-TCC.ATG.ACG.TTC.CTG.ACG.TT-3′ (all nucleotides are phosphorothioate-modified at the 3′ internucleotide linkage) was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA) and the IFA from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). We used the CpG-IFA as adjuvant for the intramuscular injection because it has been previously shown to induce Th1 dominant immune responses [46]. Thirty days after the third immunization, each mouse was inoculated intravaginally with 2 X 104 IFUs of live C. muridarum organisms in 20μl of SPG (sucrose-phosphate-glutamate buffer consisting of 218mM sucrose, 3.76mM KH2PO4, 7.1mM K2HPO4, 4.9mM glutamate, pH 7.2). Five days prior to infection, each mouse was injected with 2.5mg Depo-provera (Pharmacia Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) subcutaneously to synchronize menstrual cycle and increase mouse susceptibility to C. muridarum infection. One day before the challenge infection, 5 to 10 mice from each group were sacrificed for collecting blood and spleen tissues for monitoring immune responses.

2.2. Detecting live chlamydial organisms from vaginal, lung and muscle samples

To monitor vaginal live organism shedding, vaginal swabs were taken on different days after the intravaginal infection (once every 7 days until two consecutive negative detection results were obtained from the same mouse). Each swab was soaked in 0.5ml of SPG and vortexed with glass beads and the chlamydial organisms released into the supernatants were titrated on HeLa cell monolayers in duplicates as described previously [36]. In some experiments, mouse lung and muscle tissues were harvested and homogenized as described previously [47]. The tissue homogenates were also titrated on HeLa cells. The serially diluted swab/tissue samples were inoculated onto HeLa cell monolayers grown on coverslips in 24 well plates. After incubation for 24 hours in the presence of 2μg/ml cycloheximide, the cultures were processed for immunofluorescence assay as described below. The inclusions were counted under a fluorescence microscope. Five random fields were counted per coverslip. For coverslips with less than one IFU per field, the entire coverslips were counted. Coverslips showing obvious cytotoxicity of HeLa cells were excluded. The total number of IFUs per swab was calculated based on the number of IFUs per field, number of fields per coverslip, dilution factors and inoculation and total sample volumes. An average was taken from the serially diluted and duplicate samples for any given swab. The calculated total number of IFUs/swab was converted into log10 and the log10 IFUs were used to calculate means and standard deviation for each group at each time point.

2.3. Evaluating mouse genital tract tissue pathologies and histological scoring

Mice were sacrificed 60 days after infection for evaluating urogenital tract tissue pathology and monitoring immune responses. Before removing the genital tract tissues from mice, an in situ gross examination was performed for evidence of hydrosalpinx formation and any other gross abnormalities. The severity of oviduct hydrosalpinx was semi-quantitatively scored as the following: oviduct with no hydrosalpinx was scored with 0; hydrosalpinx can only be seen after amplification under a stereoscope was scored with 1; Hydrosalpinx clearly visible with naked eyes but with a size smaller than that of the ovary on the same side was scored with 2; Hydrosalpinx with a size similar to that of ovary was scored with 3 while larger than the ovary scored with 4. The isolated tissues, after documenting the gross pathology with a digital camera, were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned longitudinally (with 5 μm/each section). Efforts were made to include cervix, both uterine horns and oviducts as well as lumenal structures of each tissue in a given section. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as described elsewhere [37]. The H&E stained sections were assessed by a board certified pathologist (I–T.Y) blinded to mouse treatment and scored for severity of inflammation and pathologies based on the modified schemes established previously [20, 36, 37, 48]. The uterine horns and oviducts were scored separately. Scoring for dilatation of uterine horn or oviduct: 0, no significant dilatation; 1, mild dilatation of a single cross section; 2, one to three dilated cross sections; 3, more than three dilated cross sections; and 4, confluent pronounced dilation. Scoring for inflammatory cell infiltrates (at the chronic stage of infection, the infiltrates mainly contain mononuclear cells): 0, no significant infiltration; 1, infiltration at a single focus; 2, infiltration at two to four foci; 3, infiltration at more than four foci; and 4, confluent infiltration. Scores assigned to individual mice were calculated into means ± standard errors for each group of animals.

2.4. Immunofluorescence assay

HeLa cells grown on glass coverslips in 24 well plates were pretreated with DMEM containing 30mg/ml of DEAE-Dextran (Sigma, St Luis, MO) for 10 min. After the DEAE-Dextran solution was removed, swab samples that contain chlamydial organisms were serially diluted and added to the monolayers and allowed to attach to the cell monolayers for 2 hours at 37°C. The infected cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS and 2mg/ml of cycloheximide (Sigma) and processed 24h after infection. The processing included fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde dissolved in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 2% saponin (Sigma) for 1h. After washing and blocking, the cell samples were labeled with Hoechst (blue, Sigma) for visualizing DNA and a rabbit antichlamydial chaperon cofactor antibody (unpublished data) plus a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Cy2 (green; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for visualizing chlamydial inclusions. The immuno-labeled cell samples were quantitated as described above and used for image analysis and acquisition with an Olympus AX-70 fluorescence microscope equipped with multiple filter sets (Olympus, Melville, NY) as described previously [9, 45, 49, 50]. For localization of endogenous C. muridarum proteins, the C. muridarum-infected HeLa cells were immuno-labeled with mouse antibodies raised with GST-CPAF, GST-TC0177, GST-IncA or GST-MOMP fusion proteins and co-labeled with a rabbit anti-C. muridarum EB antibody. The primary antibodies were detected with a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Cy3 (red; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Cy2 (green). The DNA dye Hoechst was used to labeled DNA (blue). The immunofluorescence images were acquired as described above. All microscopic images were processed using the Adobe Photoshop program (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

2.5. Prokaryotic expression of chlamydial fusion proteins, protein purification and antibody production

The open reading frames (ORFs) coding for TC0052 (MOMP), TC0248 (CPAF; ref:[17]), TC0177 (homolog of the secreted hypothetical protein CT795, ref: [43]) and TC0396 (IncA, ref: [44]) from C. muridarum genome (NCBI protein accession# AAF39550, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez; ref:[51]) were cloned into pGEX vectors (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) and expressed as fusion proteins with glutathione-s-transferase (GST) fused to the N-terminus of the chlamydial proteins. Expression of the fusion proteins was induced with isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the fusion proteins were extracted by lysing the bacteria via sonication in a Triton-X100 lysis buffer (1%TritonX-100, 1mM PMSF, 75 units/ml of Aprotinin, 20 mM Leupeptin and 1.6 mM Pepstatin) as described previously [18, 52]. After a high-speed centrifugation to remove debris, the fusion protein-containing supernatants were either directly added to glutathione-coated microplates for measuring their reactivity with mouse sera in an ELISA as described below or further purified using glutathione-conjugated agarose beads (Pharmacia). The bead-bound fusion proteins were used to immunize mice for raising chlamydial fusion protein-specific antibodies.

2.6. Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA)

The cytokines in the supernatants of the in vitro stimulated lymphocyte cultures were measured using standard cytokine ELISA kits as instructed by the manufacturer and described previously [36, 53]. The commercially available ELISA kits [mouse IFNγ (cat# DY485), IL-17 (cat# M1700) and IL-5 (cat# DY405)] were all obtained from R&D Systems, Inc (Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, splenocytes were harvested from immunized mice with or without MoPn infection and stimulated in vitro with UV-EBs, the control protein GST or medium alone for 3 days. The culture supernatants were collected for cytokine measurements using 96 well ELISA microplates pre-coated with the corresponding capture antibodies. The capture antibody-bound cytokines were detected with biotin-conjugated antibodies and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated Avidin. The cytokine concentrations were calculated based on absorbance values, cytokine standards and sample dilution factors and expressed as ng per ml.

To detect the reactivity of antisera from the 6 groups of mice with chlamydial fusion proteins (GST-CPAF, GST-TC0177, GST-IncA & GST-MOMP), a protein array ELISA was used as described elsewhere [8, 17, 26, 54, 55]. Bacterial lysates containing the GST fusion proteins were directly added to the 96 well microplates pre-coated with glutathione (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to allow GST to interact with glutathione. After washing to remove excess fusion proteins and blocking with 2.5% nonfat milk (in phosphate-buffered solution), individual mouse serum samples after the appropriate dilutions were applied to the microplates. The serum antibody binding to antigens was detected with a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) in combination with the soluble substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulforic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS; Sigma) and quantitated by reading the absorbance (OD) at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). To reduce background binding, all mouse serum samples were pre-absorbed with lysates made from XL-1blue bacteria expressing GST alone.

The UV-inactivated whole C. muridarum organisms were used to titrate mouse antisera and isotype the chlamydia-specific IgG antibodies using the same ELISA procedure as described for the fusion protein ELISA above. The exceptions were that the EB coating was carried out in 96 well Nunc ELISA microplates (Nunc, Rochester, NY) in 0.1M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH=8.0) and the various goat anti-mouse IgG isotype secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP were used to measure the primary antibody binding.

2.7. Statistical analysis

ANOVA Test (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/anova.html) was performed to analyze the IFU and cytokine measurement data from multiple groups and a two-tailed Student t test (Microsoft Excel) to compare two given groups. The semi-quantitative pathology score data were analyzed with Student t test or Wilcoxon-signed rank test (an alternative non-parametric method of t-test; http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/wilcoxon.html). The Fisher’s Exact test (http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calc29.aspx) was used to analyze incidence of oviduct hydrosalpinx shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Hydrosalpinx Incidence and Severity Score. Urogenital tissues from the 6 groups of mice as indicated in the left column were counted for incidence of hydrosalpinx (central columns) and semi-quantitatively scored for severity (last column) under naked eyes or a stereoscope as described in the Materials and Methods section (also see Fig. 2A for example images). The incidence was compared between different groups using the Fisher’s Exact test while the pathology scores were analyzed with Wilcoxon-signed rank test. Groups with statistically significant difference were labeled with the corresponding p values. The data came from 3 independent experiments

| Route | Group | Mouse number | Hydrosalpinx

|

Hydrosalpinx severity scores (Mean ±SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Unilateral | Bilateral | ||||

| i. n. | PBS | 31 | 27 (87%) | 10 (32%) | 17 (55%) | 3.55 ± 2.36 |

| UV-EB | 15 | 12 (80%) | 4 (27%) | 8 (53%) | 3.40 ± 2.87 | |

| Live EB | 20 | 4 (20%) P<0.01 | 2(10%)P=0.065 | 2 (10%)P<0.01 | 0.50 ± 1.15 P<0.01 | |

|

| ||||||

| i. m.. | GST | 35 | 31(89%) | 9 (26%) | 22 (63%) | 3.89 ± 2.74 |

| UV-EB | 15 | 10 (67%) | 3 (20%) | 7 (47%) | 2.33 ± 2.50 | |

| Live EB | 17 | I2(70%) | 6 (35%) | 6(35%)p=0..57 | 2.47 ± 2.85 | |

3.Results

3.1. Intranasal immunization with live C. muridarum organisms led to a rapid clearance of intravaginal chlamydial infection

To determine immunization conditions for inducing anti-Chlamydia immunity, we immunized six groups of Balb/c mice as described Fig. 1. Three groups were given intranasally with live C. muridarum EB alone, PBS or UV-EB formulated with CpG. The other three groups were given intramuscularly with glutathione-s-transferase (GST), live or UV-EB all formulated with CpG and IFA (panel A). One month after the last immunization, mice were challenged intravaginally with C. muridarum organisms. Vaginal swabs were taken weekly for monitoring the shedding of infectious chlamydial organisms (B). On day 7 after infection, mice immunized intranasally with live EBs displayed the lowest level of IFUs (0.69±1.25) from the vaginal swabs with only 5 out of the 20 mice still shedding live organisms (C). By day 14, this group of mice completely cleared infection. However, mice similarly immunized with UV-EBs displayed a shedding time course similar to that of the PBS control group throughout the experiments. Although only 50 IFUs of live organisms were intranasally inoculated per mouse (compared to 1 X 106 IFUs of UV-EBs), the immunization induced close to sterile immunity. In contrast, intramuscular immunization with 1 X 105 IFUs of live EBs only induced partial protection. Although the overall level of vaginal IFU shedding was significantly reduced in the group intramuscularly immunized with live EBs on day 7 [4.69±1.11 (mean standard ± deviation) versus 5.53±0.49 (GST group), p<0.001], 16 out of the 17 mice were still positive for live organism shedding. Only by day 14, did most mice (12 out of 17) clear infection. The group intramuscularly immunized with UV-EBs developed even weaker protection with a significant reduction in vaginal live organism shedding on day 14 [2.42±1.8 versus 4.3±1.47 (GST group), p<0.05]. However, 12 of the 15 mice were still positive for live organism shedding. Only by day 21, did all mice clear infection. Clearly, comparing to the GST control group, the intramuscular immunization with either live or UV-EBs induced partial protection against vaginal challenge infection. Nevertheless, the protection induced by intramuscular immunization with either live or UV-EBs was not as strong as that induced by the intranasal immunization with live EBs.

Fig. 1. Effects of immunization on shedding of infectious chlamydial organisms following an intravaginal challenge infection.

br(A) Groups of mice were immunized intranasally (i.n.) or intramuscularly (i.m.) with different chlamydial EB preps. For i.n. route, mice were given three doses of PBS or UV-EB + CpG 3 times on day 0, 20 & 30 as indicated on top the figure or live EB once on day 0. For i.m. route, three doses of GST protein + CpG + IFA (incomplete Freunds Adjuvant), UV-EB + CpG + IFA or live EB + CpG + IFA were given. (B) One month following the final immunization, mice were challenged intravaginally (i.v.) with 2×104 IFUs of C. muridarum organisms and vaginal swabs were taken weekly as indicated along the x-axis for measuring the number of live organisms (expressed as inclusion forming units, IFUs). The IFUs from each swab was converted into Log10, and the log10 IFUs were used to calculate mean and standard deviation (SD) for each mouse group at a given time point as displayed along the y-axis. The log10 IFUs were compared between 6 groups of mice at each time point using ANOVA test, followed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test for comparing between a control group (PBS for i.n.; GST for i.m.) and a test group. Double asterisks ** indicate p<0.01 while single asterisk * p<0.05. The number of mice with detectable infectious units (IFUs) from each group and at each time point is listed in the chart at the bottom. (C) The number of mice with positive shedding was compared between a control and a test group using the Fisher’s Exact test. Note that the group immunized intranasally with live EBs displayed the most rapid clearance of intravaginal infection with only 5 of the 20 mice remained shedding of live organisms at a low level on day 7 and complete clearance on day 14. The data came from 3 independent experiments.

3.2. Intranasal immunization with live C. muridarum organisms induced a strong protection against mouse upper genital tract pathologies

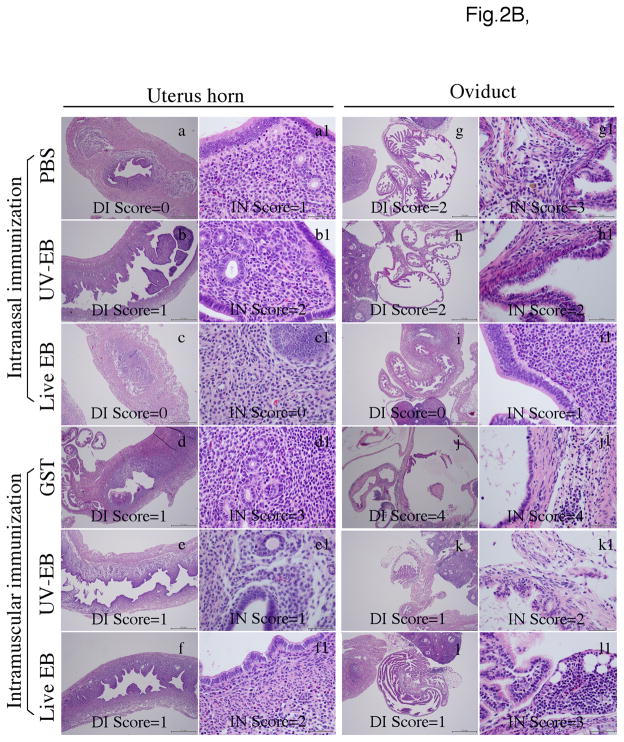

Sixty days after infection, all immunized mice were sacrificed for evaluating inflammatory pathology in genital tract tissues (Fig. 2). Under naked eyes or a stereoscope, both uterine horn dilation and oviduct hydrosalpinx can be determined and semi-quantitatively scored [36, 37, 48, 56]. The severity of hydrosalpinx largely correlates with the extent of oviduct blockage [37, 48]. Due to large file size, only a representative image from each of the 6 mouse groups was displayed in Fig. 2A. The uterine horn dilation under naked eyes was not obvious in any of the Balb/c mice, which is consistent with previous observations [36, 56]. Thus, only the gross pathology hydrosalpinx was scored. As shown in table 1, >80% of mice in the intranasal or intramuscular control groups developed unilateral or bilateral hydrosalpinx upon C. muridarum intravaginal infection. Mice intranasally immunized with live EB developed the lowest level of hydrosalpinx in terms of incidence & severity (p<0.01 for both) while the UV-EB-immunized mice developed hydrosalpinx as severe as the PBS control group. Interestingly, mice intramuscularly immunized with either live or UV-EBs did not display any significant reduction in hydrosalpinx incidence or severity despite the significant reduction in vaginal live organism shedding. The genital tissue inflammation was further examined under a microscope (Fig. 2B & C). Histological sections from both uterine horn and oviduct tissues were semi-quantitatively graded for severity of lumenal dilatation and inflammatory cell infiltration by a board-certified pathologist in a double blind fashion. Consistently with the gross appearance evaluation, there was no statistically significant difference in uterine horn pathologies between different groups under a microscope. Importantly, mice intranasally immunized with live organisms displayed significantly reduced levels of oviduct pathology in terms of both lumenal dilatation and inflammatory cell infiltration (p<0.01 for both). None of the other immunized groups displayed any significant difference in these parameters when comparing to the corresponding control groups.

Fig. 2. Effects of immunization on genital tract pathologies induced by intravaginal chlamydial infection.

Groups of mice were immunized either i.n. or i.m. with live or UV-EBs and infected intravaginally with C. muridarum organisms as described in Fig.1 legend. Sixty days after infection, mice were sacrificed for evaluating pathologies of genital tract tissues under both naked eyes (for gross appearance) and microscope (for luminal dilatation & inflammatory cellular infiltration). (A) Representative images of the gross appearance of mouse genital tracts were presented from each of the 6 groups of mice as listed on the left of the figure. The entire genital tract from vagina to ovary was displayed from left to right (left panels) and the oviduct and ovary regions were amplified from both sides (right panels). Although the uterine horn regions from all mice appeared to be normal, significant hydrosalpinx in the oviduct regions developed in different groups of mice. Both the incidence and severity of hydrosalpinx were scored under naked eyes or stereoscope. Mice with hydrosalpinx in one (unilateral) or both (bilateral) oviducts were indicated at the right of the figure (white arrows). The severity of the hydrosalpinx was semi-quantitatively scored as described in the method section and examples of the hydrosalpinx severity scoring were indicated in the right panels. Both the incidence and severity of hydrosalpinx were compared statistically in table 1. (B) The urogenital tract tissues were sectioned for microscopic observation of inflammatory pathologies. Representative H&E stained section images covering either the uterine horn (panels a-f) or oviduct (g–l) regions were presented from each group (as indicated on the left). Each section was semi-quantitatively scored for both inflammatory infiltration (IN) and lumenal dilatation (DI) as described in the method section. Examples of the dilatation scores were indicated in the low amplification images (panels a-f for uterus horn; g-l for oviduct) while inflammatory infiltration scores were indicated in the high amplification images (panels a1 to f1 for uterine horn; g1–l1 for oviduct). The semi-quantitation results were presented in (C). Inflammation (panels a & c) and dilatation (b & d) scores (each derived from 5 different sections) assigned to individual mice were used to calculate the means and standard errors for each group as shown along the Y-axis. The mouse groups were indicated along the X-axis at the bottom while the tissue sources were indicated on the top. The scores were compared between different groups using ANOVA followed by the two-tailed Student t test. The data came from 3 independent experiments.

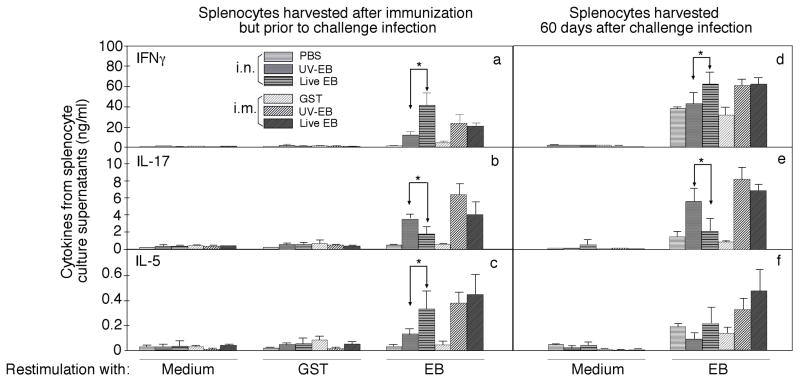

3.3. Intranasal immunization with live C. muridarum organisms induced a robust Th1- dominant immunity with a minimal Th17 response

To monitor immune responses induced by various immunization schemes, splenocytes and sera were collected from mice one month after the final immunization (prior to challenge infection) or two months after challenge infection (at the time when mice were sacrificed for evaluating urogenital tract pathologies). The splenocytes, after in vitro re-stimulation with UV-inactivated C. muridarum EB organisms or control antigens for 3 days, were detected for production of cytokines IFNγ (by Th1 CD4+ T cells), IL-17 (Th17) and IL-5 (Th2; Fig.3). As controls, splenocytes harvested from EB-immunized mice did not produce any significant T cell cytokines when cultured in the absence of specific antigens and splenocytes from mock-immunized mice did not respond to stimulation with UV-EBs, demonstrating that the in vitro restimulation culture systems can allow us to measure antigen-specific T cell responses. Upon EB antigen restimulation, all EB-immunized mice produced significant levels of T cell cytokines above the background, suggesting that the immunization was successful. Careful comparison between the various immunized groups revealed that mice intranasally immunized with live EBs produced the highest level of IFNγ. Interestingly, these same mice produced the lowest level of IL-17 while the IL-5 level of these mice was comparable to the two intramuscular immunization groups but significantly higher than the UV-EB intranasal immunization group. The trend of high IFNγ with low IL-17 in live EB intranasal immunization group continued even after challenge infection although the IL-5 level was attenuated after infection. Clearly, intranasal immunization with live EBs induced a Th1 dominant and Th17 low response while intranasal immunization with UV-EB induced a Th17 dominant response. The intramuscular immunization with either live or UV-EBs induced responses with high levels of both Th17 and Th2 cytokines. Obviously, only the Th1 dominant and Th17 low response best correlated with protective immunity.

Fig. 3. MoPn-specific cellular immune responses induced by immunization with live or UV-EB.

organisms. The 6 groups of mice were immunized and infected as described in Fig.1 legend. Splenocytes were collected from the six groups of mice one month after the final immunization (prior to challenge infection, panels a–c) or two months after challenge infection (d–f) for in vitro re-stimulation with UV-inactivated MoPn EB organisms at 1×106 IFUs per well or 10μg/mL GST or medium alone as indicated at the bottom of the figure. Three days after the stimulation, the culture supernatants were collected for IFNγ, IL-17 and IL-5 detection and the results were expressed as ng/ml as listed along the Y-axis (mean ± SD). The cytokine concentrations were compared between different groups using ANOVA followed by a two-tailed Student t test. Note that intranasal immunization with live organisms induced significantly higher levels of IFNγ & IL-5 but lower IL-17 than the dead organism-immunized group (* p<0.05) prior to challenge infection. The trend continued even after challenge infection. However, intramuscular immunization with either live or dead organisms induced significant levels of all 3 cytokines. The data came from one experiment with 5 mice in each group.

We further monitored the immunization-induced Chlamydia-specific humoral immune responses (Fig. 4). The Chlamydia-specific total IgG antibody titers from all 6 groups were determined using ELISA with C. muridarum organisms as antigens. All mice immunized with EBs regardless of the immunization routes and EB preps developed significantly high levels of anti-chlamydial organism antibodies comparing to the control groups. The titer of antibodies in the intranasal UV-EB immunization group that developed no protective immunity was significantly lower than that in the intranasal live EB immunization group that developed the strongest protective immunity. However, both groups immunized intramuscularly with either live or UV-EBs, although only developed partial protective immunity, developed robust anti-chlamydia antibody responses with the titers similar to that of the intranasal live EB immunization group. Thus, the overall anti-chlamydia antibody titers did not always correlate with the protective immunity. When the chlamydia-specific IgG antibodies were further isotyped, we found that among all the groups, the intranasal live EB group displayed the highest ratio of IgG2a versus IgG1, suggesting that an overall Th1-dominant environment was maintained in this group of mice, which may contribute to the robust protective immunity.

Fig. 4. Chlamydia-specific humoral immune responses following immunization with live or UV-EB organisms.

Serum samples were collected one month after the final immunization (prior to challenge infection) from six groups of mice (with 15 to 20 mice in each group) as shown along the X-axis and described in Fig.1 legend. (A) The total IgG antibody titers were determined using ELISA with C. muridarum organisms (UV-EBs) as antigens. The mouse sera were 5 fold serially diluted starting with 1:80. The mouse antibody binding to chlamydial organisms were detected with a goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate and the results were expressed as absorbance as displayed along the Y-axis. Note that all EB-immunized mice produced significant levels of anti-chlamydial organism antibodies. (B) The Chlamydia-specific IgG antibodies were further isotyped using the same C. muridarum organism-coated ELISA plates. The ratios of IgG2a versus IgG1 from each group of mice were displayed along the Y-axis. The serum dilutions used for the isotyping were 1:80 for the two control groups and UV-EB i.n. group and 1:2000 for the rest of the groups. The IgG2a/IgG1 ratios maintained a similar trend when the sera were isotyped at different dilutions. Note that the highest ratio of IgG2a versus IgG1 was observed in the intranasal live EB immunization group (p<0.01 against any other groups). The data came from 3 independent experiments.

3.4. Mice immunized intranasally but not intramuscularly with live C. muridarum organisms produced antibodies to chlamydial secretion proteins

It has been previously demonstrated that antibody responses to chlamydial secretion proteins that are not packaged in the EBs can be used to indicate chlamydial organism biosynthesis and replication in the infected hosts [17, 18, 44]. To test whether chlamydial organisms undergo biosynthesis and replication in mice after intranasal inoculation or intramuscular immunization with live EBs, we compared the reactivity of antisera (collected prior to challenge infection) with chlamydial secretion proteins between mice immunized via different routes (Fig. 5). The antisera from mice intranasally immunized with live chlamydial organisms but not from other groups recognized all 3 chlamydial secretion proteins including CPAF, TC0177 and IncA although antisera from all groups of mice reacted with MOMP (the chlamydial major outer membrane structural protein). The results demonstrated that C. muridarum organisms underwent biosynthesis and possibly replication only in the intranasal live EB immunization mice. Since the chlamydial proteins were coated onto the ELISA microplates in the form of GST fusion proteins, sera from the GST-immunized mice recognized all GST fusion proteins, indicating that all chlamydial fusion proteins were coated at an equivalent level (Fig. 5A). To directly demonstrate whether the live C. muridarum organisms inoculated intranasally or injected intramuscularly can indeed replicate in mice, we harvested the corresponding mouse tissues on days 8 and 21 after the live organism delivery and compared the recovery of the infectious organisms in a separate experiment (Fig. 5B). Significant amounts of live organisms were recovered from the lungs of mice intranasally inoculated with 50 IFUs on day 8 after the inoculation but not day 21, suggesting that the intranasal inoculation caused airway infection and the infection is self-limiting. However, no live organisms were ever found from the muscle tissues of mice intramuscularly injected with 1 x 105 IFUs of live C. muridarum organisms on either day 8 or 21. These results confirmed that live chlamydial organism replication took place only in the intranasally immunized mice. The intracellular localization of these 4 C. muridarum antigens was further visualized in C. muridarum-infected cells (Fig. 5C). As expected, CPAF, TC0177 and IncA were secreted into host cell cytosol and inclusion membrane respectively without any significant amounts inside the inclusions. In contrast, MOMP was restricted within the inclusions.

Fig. 5. Mouse antibody reactivity with C. muridarum secretion proteins.

(A) Mouse serum samples as described in Fig.4 legend (shown along the X-axis) were reacted with the following fusion proteins GST-CPAF (panel a), GST-TC0177 (b), GST-IncA (c) & GST-MOMP (d) immobilized onto glutathione-coated ELISA plates (via GST-glutathione interactions). The reactivity was recorded as absorbance at 405nm (shown along the Y-axis). Sera from the GST-immunized mice reacted equally well with all GST fusion proteins, indicated that all GST fusion proteins were coated onto the ELISA plates at equivalent levels. Although sera from all EB-immunized groups reacted with GST-MOMP, only the intranasal live EB immunization group significantly recognized the secretion proteins CPAF, TC0177 & IncA. The data came from 3 independent experiments. (B) Mice intranasally inoculated with 50 or intramuscularly with 1X105 IFUs (n=5) were sacrificed on day 8 or 21 (X-axis) for titrating live organisms harvested from lungs or muscle tissues. The number of IFUs was calculated per lung or gram of muscle tissues and converted into log10 (Y-axis). The data came from one experiment with 5 mice in each group. (C) Mouse antibodies raised with chlamydial GST fusion proteins as shown on top of the images were used to localize the endogenous chlamydial proteins (red) in C. muridarum-infected HeLa cells. The cell samples were also co-labeled with a rabbit antiC. muridarum EB antibody (green) and DNA Hoechst dye (blue). Both CPAF and TC0177 (homolog of CT795, a known secreted protein of C. trachomatis) were secreted into cytosol of the infected cells while IncA to inclusion membrane. However, MOMP is restricted within the inclusions. The representative images came from one experiment and 3 independent experiments were carried out.

4.Discussion

Since the first successful isolation of C. trachomatis organisms from human ocular tissues more than half a century ago [57, 58], tremendous amounts of efforts have been made to develop vaccines for preventing C. trachomatis-induced diseases [2, 20–22, 24, 28, 34, 59–63]. During human trachoma trials, intramuscular immunization with formalin-fixed C. trachomatis whole organisms not only failed to induce lasting protective immunity but also exacerbated ocular pathologies [21, 22, 59–61], suggesting that antigens associated with the purified organisms may not be sufficient for inducing protective immunity in humans and identification of protective antigens as C. trachomatis subunit vaccines is necessary. Various animal model studies have revealed that live chlamydial infection can induce strong protective immunity against subsequent chlamydial challenge infection [27, 36, 56, 64–66], suggesting that replicating chlamydial organisms can produce and present protective antigens to the appropriate host immune compartments to induce protection-relevant immunological memory. Thus, in the current study, we used a live infection immunization mouse model to characterize immune responses responsible for protective immunity against C. trachomatis-induced upper tract pathologies. Although intravaginal infection with C. muridarum organisms is known to induce sterile immunity against subsequent infection in mice, a single intravaginal infection is sufficient for inducing severe upper genital tract pathologies [36, 56]. We, thus, used an intranasal infection as the route for live replicating organism immunization. It has been known that the C. muridarum organisms can undergo productive infection when intranasally inoculated into mice [47]. We compared intranasal live immunization with immunization conditions that do not permit organism replication, including intranasal immunization with UV-EBs and intramuscular with live or UV-EBs. We found that the immunity induced by intranasal immunization with live EBs protected mice from developing upper genital tract pathology following intravaginal infection. We have further characterized the protective immunity as a Th1-dominant but Th17-low T cell response coupled with immune responses to chlamydial secretion proteins.

The extensive immunological studies have led to the identification of a Th1-dominant host immune response as an essential element of the anti-C. trachomatis protective immunity [2, 39, 67]. However, the induction conditions and antigen basis of the Th1-dominant protective immunity for preventing chlamydial infection has not been identified. The primary site of C. trachomatis infection is the lower genital tract tissue that is dominant with Th2 responses after chlamydial infection [68]. How to use vaccination to induce a Th1 dominant response in the lower genital tract has become an important issue facing chlamydial vaccine development. Fortunately, the current study revealed that mice intranasally immunized with live organisms developed a long lasting Th1-dominant immunity against intravaginal chlamydial infection, leading to complete protection from chlamydia-induced upper genital tract pathologies.

Interestingly, this robust protection was accompanied with a low Th17 response. Although an early IL-17 response was found to play a protective role in controlling chlamydial airway infection [47, 69, 70] and Th17 is required for protection against pulmonary infection with fungi [71], apparently, IL-17 is not required for resolution of chlamydial genital tract infection [72]. More importantly, a sustained Th17 response has been frequently associated with inflammatory pathologies with [73] or without [74] infection. Under some infection condition, IL-17 signaling may even exacerbate infection and infection-induced pathologies [75]. In the current study, mice intramuscularly immunized with live or UV-EBs produced high levels of IL-17 and remained susceptible to chlamydial intravaginal infection and developed severe upper genital tract pathologies. These results suggest that a C. trachomatis vaccine aimed at preventing upper genital tract pathologies induced by chlamydial intravaginal infection in humans should avoid activation of an excessive Th17 response.

Accompanying with the robust protection against intravaginal infection induced by the replicating organisms in the airway is also the production of antibodies recognizing chlamydial secretion proteins, including CPAF, TC0177 and IncA. Mice immunized either intranasally with UV-EBs or intramuscularly with UV-EBs or live EBs did not permit biosynthesis and replication of the injected EBs and thus failed to produce antibodies against the chlamydial secretion proteins. These observations are consistent with the established concept that only replicating organisms can produce these secretion antigens. The correlation of chlamydial secretion protein expression with protective immunity suggests that the Chlamydia-secreted proteins may contribute to the protective immunity. Indeed, the secreted protein CPAF has been shown to induce protective immunity in mice [19, 20, 76]. The next question is how to deliver these protection relevant antigens to the host immune system so that long lasting antigen-specific memory responses can be induced with the phenotype of high Th1 & low Th17.

Understanding the mechanisms of protective immunity against urogenital tract infection with C. trachomatis will be the key for developing an effective vaccine. The intranasal immunization with live organisms plus intravaginal infection protocol has provided an appropriate system for us to dissect the mechanisms. The key question is how the robust protective immunity is induced. For example, what signals are required for activating host cells (including DCs, lymphocytes and cells yet to be identified) in the airway so that protective immunity can be induced against urogenital challenge infection? Our hypothesis is that the quality of DCs activated by live chlamydial infection in the airway may matter the most. First, the chlamydial organisms and their secretion proteins (proteins produced and secreted out of the organisms during live infection but not incorporated back to the organisms, thus designated as infection-dependent proteins) have to access to the submucosal DCs, which can be achieved via live infection but not dead organism inoculation. Second, the chlamydia secretion or infection-dependent proteins released from the lysed epithelial cells or produced by chlamydial organisms inside DCs may simultaneously activate multiple innate immunity receptor-mediated signaling pathways to promote antigen presentation. The DCs thus activated in the airway may possess the ability to induce memory lymphocytes that can be recruited to the urogenital tract for protecting against challenge infection. Since dead organisms don’t contain nor produce the infection-dependent antigens, exposure of increasing amounts of dead organisms to DCs may not be able to achieve the same type/level of DC activation induced by live organisms. This hypothesis is consistent with the observations that live organism-activated DCs are both quantitatively and qualitatively different from those activated by dead organisms [33, 77, 78] and DCs pulsed with whole organisms in vitro induced robust protection against chlamydial infection and the protection was dependent on IL-12 and other Th1 promoting cytokine production by the pulsed DCs [34, 79]. A recent study by Yu et al from Dr. Brunham’s group [77] has shown that intranasal live infection with Chlamydia significantly reduced live organism shedding 6 days after intravaginal challenge infection and this protection correlated with the generation of T cells able to produce both IFNγ & TNFα. Consistent with these previous observations, our current study has also demonstrated that the intranasal live organism infection induced an IFNγ-dominant response that correlated with protection against both lower tract infection and upper tract pathology. We are in the process of evaluating whether chlamydial infection-dependent proteins in the absence of live infection can efficiently activate DCs and the DCs thus activated can present chlamydial antigens to T cells and induce protective immunity in the urogenital tract.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants (to G. Zhong) from the US National Institutes of Health and Merck.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C; Services USDoHaH. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2008. Atlanta, GA: Nov, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/toc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockey DD, Wang J, Lei L, Zhong G. Chlamydia vaccine candidates and tools for chlamydial antigen discovery. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009 Oct;8(10):1365–77. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman KJ, Daling JR, Stergachis A, Weiss NS, Foy HM, Wang SP, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases and tubal pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 1990 Jul-Sep;17(3):115–21. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinnunen AH, Surcel HM, Lehtinen M, Karhukorpi J, Tiitinen A, Halttunen M, et al. HLA DQ alleles and interleukin-10 polymorphism associated with Chlamydia trachomatis-related tubal factor infertility: a case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2002 Aug;17(8):2073–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephens RS. The cellular paradigm of chlamydial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2003 Jan;11(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong G. Killing me softly: chlamydial use of proteolysis for evading host defenses. Trends Microbiol. 2009 Oct;17(10):467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockey DD, Scidmore MA, Bannantine JP, Brown WJ. Proteins in the chlamydial inclusion membrane. Microbes Infect. 2002 Mar;4(3):333–40. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Chen C, Chen D, Wu Y, Zhong Y, Zhong G. Characterization of fifty putative inclusion membrane proteins encoded in the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. Infect Immun. 2008 Jun;76(6):2746–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00010-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong G, Fan P, Ji H, Dong F, Huang Y. Identification of a chlamydial protease-like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J Exp Med. 2001 Apr 16;193(8):935–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong G, Lei L, SG, Lu C, Qi M, Chen D. Chlamydia-secreted proteins in chlamydial interactions with host cells. Current Chemical Biology. 2011;5(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valdivia RH. Chlamydia effector proteins and new insights into chlamydial cellular microbiology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008 Feb;11(1):53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betts-Hampikian H, Fields K. The chlamydial type III secretion mechanism: revealing cracks in a tough nut. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2010 October 19;1(1):13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong S, Lei L, Chang X, Belland R, Zhong G. Chlamydia trachomatis secretion of hypothetical protein CT622 into host cell cytoplasm via a secretion pathway that can be inhibited by the type III secretion system inhibitor compound 1. Microbiology. 2011 Jan 13; doi: 10.1099/mic.0.047746-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clifton DR, Fields KA, Grieshaber SS, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Mead DJ, et al. A chlamydial type III translocated protein is tyrosine-phosphorylated at the site of entry and associated with recruitment of actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jul 6;101(27):10166–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402829101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel J. Tarp and Arp: How Chlamydia induces its own entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jul 6;101(27):9947–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403633101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hower S, Wolf K, Fields KA. Evidence that CT694 is a novel Chlamydia trachomatis T3S substrate capable of functioning during invasion or early cycle development. Mol Microbiol. 2009 Jun;72(6):1423–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma J, Bosnic AM, Piper JM, Zhong G. Human antibody responses to a Chlamydia-secreted protease factor. Infect Immun. 2004 Dec;72(12):7164–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7164-7171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Zhang Y, Lu C, Lei L, Yu P, Zhong G. A genome-wide profiling of the humoral immune response to Chlamydia trachomatis infection reveals vaccine candidate antigens expressed in humans. J Immunol. 2010 Aug 1;185(3):1670–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphey C, Murthy AK, Meier PA, Neal Guentzel M, Zhong G, Arulanandam BP. The protective efficacy of chlamydial protease-like activity factor vaccination is dependent upon CD4+ T cells. Cell Immunol. 2006 Aug;242(2):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy AK, Chambers JP, Meier PA, Zhong G, Arulanandam BP. Intranasal vaccination with a secreted chlamydial protein enhances resolution of genital Chlamydia muridarum infection, protects against oviduct pathology, and is highly dependent upon endogenous gamma interferon production. Infect Immun. 2007 Feb;75(2):666–76. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01280-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhir SP, Agarwal LP, Gupta SB, Detels R, Wang SP, Grayston JT. Trachoma vaccine trial in India: results of two-year follow-up. Indian J Med Res. 1968 Aug;56(8):1289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grayston JT, Wang SP, Woolridge RL, Alexander ER. Prevention of Trachoma with Vaccine. Arch Environ Health. 1964 Apr;8:518–26. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1964.10663711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison SG, Su H, Caldwell HD, Morrison RP. Immunity to murine Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract reinfection involves B cells and CD4(+) T cells but not CD8(+) T cells. Infect Immun. 2000 Dec;68(12):6979–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6979-6987.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Vaccination with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein can elicit an immune response as protective as that resulting from inoculation with live bacteria. Infect Immun. 2005 Dec;73(12):8153–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8153-8160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong G, Berry J, Brunham RC. Antibody recognition of a neutralization epitope on the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1994 May;62(5):1576–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1576-1583.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong G, Toth I, Reid R, Brunham RC. Immunogenicity evaluation of a lipidic amino acid-based synthetic peptide vaccine for Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol. 1993 Oct 1;151(7):3728–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H, Messer R, Whitmire W, Hughes S, Caldwell HD. Subclinical chlamydial infection of the female mouse genital tract generates a potent protective immune response: implications for development of live attenuated chlamydial vaccine strains. Infect Immun. 2000 Jan;68(1):192–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.192-196.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su H, Morrison RP, Watkins NG, Caldwell HD. Identification and characterization of T helper cell epitopes of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Exp Med. 1990 Jul 1;172(1):203–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens RS, Wagar EA, Schoolnik GK. High-resolution mapping of serovar-specific and common antigenic determinants of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Exp Med. 1988 Mar 1;167(3):817–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotter TW, Meng Q, Shen ZL, Zhang YX, Su H, Caldwell HD. Protective efficacy of major outer membrane protein-specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG monoclonal antibodies in a murine model of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1995 Dec;63(12):4704–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4704-4714.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry LL, Feilzer K, Hughes S, Caldwell HD. Clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis from the murine genital mucosa does not require perforin-mediated cytolysis or Fas-mediated apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1999 Mar;67(3):1379–85. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1379-1385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barteneva N, Theodor I, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Role of neutrophils in controlling early stages of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1996 Nov;64(11):4830–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4830-4833.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang D, Yang X, Lu H, Zhong G, Brunham RC. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis induced by vaccination with live organisms correlates with early granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-12 production and with dendritic cell-like maturation. Infect Immun. 1999 Apr;67(4):1606–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1606-1613.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Zhong G. Interleukin-12 production is required for chlamydial antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to induce protection against live Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1999 Apr;67(4):1763–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1763-1769.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murthy AK, Sharma J, Coalson JJ, Zhong G, Arulanandam BP. Chlamydia trachomatis pulmonary infection induces greater inflammatory pathology in immunoglobulin A deficient mice. Cell Immunol. 2004 Jul;230(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng W, Shivshankar P, Li Z, Chen L, Yeh IT, Zhong G. Caspase-1 contributes to Chlamydia trachomatis-induced upper urogenital tract inflammatory pathologies without affecting the course of infection. Infect Immun. 2008 Feb;76(2):515–22. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01064-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah AA, Schripsema JH, Imtiaz MT, Sigar IM, Kasimos J, Matos PG, et al. Histopathologic changes related to fibrotic oviduct occlusion after genital tract infection of mice with Chlamydia muridarum. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Jan;32(1):49–56. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148299.14513.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton DL, Landers DV, Schachter J. Experimental Chlamydia trachomatis salpingitis in mice: initial studies on the characterization of the leukocyte response to chlamydial infection. J Infect Dis. 1989 Jun;159(6):1105–10. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.6.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison RP, Caldwell HD. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 2002 Jun;70(6):2741–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2741-2751.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrison SG, Morrison RP. A predominant role for antibody in acquired immunity to chlamydial genital tract reinfection. J Immunol. 2005 Dec 1;175(11):7536–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fling SP, Sutherland RA, Steele LN, Hess B, D’Orazio SE, Maisonneuve J, et al. CD8+ T cells recognize an inclusion membrane-associated protein from the vacuolar pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Jan 30;98(3):1160–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampe MF, Wilson CB, Bevan MJ, Starnbach MN. Gamma interferon production by cytotoxic T lymphocytes is required for resolution of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1998 Nov;66(11):5457–61. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5457-5461.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi M, Lei L, Gong S, Liu Q, Delisa M, Zhong G. Chlamydia trachomatis secretion of an immunodominant hypothetical protein (CT795) into host cell cytoplasm. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JB.01301-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rockey DD, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. Cloning and characterization of a Chlamydia psittaci gene coding for a protein localized in the inclusion membrane of infected cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995 Feb;15(4):617–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greene W, Xiao Y, Huang Y, McClarty G, Zhong G. Chlamydia-infected cells continue to undergo mitosis and resist induction of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2004 Jan;72(1):451–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.451-460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu RS, Targoni OS, Krieg AM, Lehmann PV, Harding CV. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997 Nov 17;186(10):1623–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Gao L, Lei L, Zhong Y, Dube P, Berton MT, et al. A MyD88-dependent early IL-17 production protects mice against airway infection with the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia muridarum. J Immunol. 2009 Jul 15;183(2):1291–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imtiaz MT, Schripsema JH, Sigar IM, Kasimos JN, Ramsey KH. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases protects mice from ascending infection and chronic disease manifestations resulting from urogenital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun. 2006 Oct;74(10):5513–21. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00730-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao Y, Zhong Y, Su H, Zhou Z, Chiao P, Zhong G. NF-kappa B activation is not required for Chlamydia trachomatis inhibition of host epithelial cell apoptosis. J Immunol. 2005 Feb 1;174(3):1701–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan T, Lu H, Hu H, Shi L, McClarty GA, Nance DM, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis in chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J Exp Med. 1998 Feb 16;187(4):487–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, et al. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Mar 15;28(6):1397–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma J, Zhong Y, Dong F, Piper JM, Wang G, Zhong G. Profiling of human antibody responses to Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital tract infection using microplates arrayed with 156 chlamydial fusion proteins. Infect Immun. 2006 Mar;74(3):1490–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1490-1499.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng W, Shivshankar P, Zhong Y, Chen D, Li Z, Zhong G. Intracellular interleukin-1alpha mediates interleukin-8 production induced by Chlamydia trachomatis infection via a mechanism independent of type I interleukin-1 receptor. Infect Immun. 2008 Mar;76(3):942–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong GM, Brunham RC. Immunoaccessible peptide sequences of the major outer membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis serovar C. Infect Immun. 1990 Oct;58(10):3438–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3438-3441.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Z, Chen D, Zhong Y, Wang S, Zhong G. The chlamydial plasmid-encoded protein pgp3 is secreted into the cytosol of Chlamydia-infected cells. Infect Immun. 2008 Aug;76(8):3415–28. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01377-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen L, Lei L, Chang X, Li Z, Lu C, Zhang X, et al. Mice deficient in MyD88 Develop a Th2-dominant response and severe pathology in the upper genital tract following Chlamydia muridarum infection. J Immunol. 2010 Mar 1;184(5):2602–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang FF, Huang YT, Chang HL, Wong KC. Isolation of trachoma virus in chick embryo. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1957;1(2):109–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y. Etiology of trachoma: a great success in isolating and cultivating Chlamydia trachomatis. Chin Med J (Engl) 1999 Oct;112(10):938–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clements C, Dhir SP, Grayston JT, Wang SP. Long term follow-up study of a trachoma vaccine trial in villages of Northern India. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979 Mar;87(3):350–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang SP, Grayston JT. A potency test for trachoma vaccine utilizing the mouse toxicity prevention test. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5 Suppl):1443–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang SP, Grayston JT, Alexander ER. Trachoma vaccine studies in monkeys. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5:Suppl):1615–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tammiruusu A, Penttila T, Lahesmaa R, Sarvas M, Puolakkainen M, Vuola JM. Intranasal administration of chlamydial outer protein N (CopN) induces protection against pulmonary Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in a mouse model. Vaccine. 2007 Jan 4;25(2):283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishizaki M, Allen JE, Beatty PR, Stephens RS. Immune specificity of murine T-cell lines to the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1992 Sep;60(9):3714–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3714-3718.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olsen AW, Theisen M, Christensen D, Follmann F, Andersen P. Protection against Chlamydia promoted by a subunit vaccine (CTH1) compared with a primary intranasal infection in a mouse genital challenge model. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Intranasal immunization induces long-term protection in mice against a Chlamydia trachomatis genital challenge. Infect Immun. 1996 Dec;64(12):5341–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5341-5348.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cui ZD, Tristram D, LaScolea LJ, Kwiatkowski T, Jr, Kopti S, Ogra PL. Induction of antibody response to Chlamydia trachomatis in the genital tract by oral immunization. Infect Immun. 1991 Apr;59(4):1465–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1465-1469.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morrison RP, Feilzer K, Tumas DB. Gene knockout mice establish a primary protective role for major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted responses in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1995 Dec;63(12):4661–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4661-4668.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marks E, Tam MA, Lycke NY. The female lower genital tract is a privileged compartment with IL-10 producing dendritic cells and poor Th1 immunity following Chlamydia trachomatis infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001179. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bai H, Cheng J, Gao X, Joyee AG, Fan Y, Wang S, et al. IL-17/Th17 promotes type 1 T cell immunity against pulmonary intracellular bacterial infection through modulating dendritic cell function. J Immunol. 2009 Nov 1;183(9):5886–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou X, Chen Q, Moore J, Kolls JK, Halperin S, Wang J. Critical role of the interleukin-17/interleukin-17 receptor axis in regulating host susceptibility to respiratory infection with Chlamydia species. Infect Immun. 2009 Nov;77(11):5059–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00403-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wuthrich M, Gern B, Hung CY, Ersland K, Rocco N, Pick-Jacobs J, et al. Vaccine-induced protection against 3 systemic mycoses endemic to North America requires Th17 cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011 Jan 4; doi: 10.1172/JCI43984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scurlock AM, Frazer LC, Andrews CW, Jr, O’Connell CM, Foote IP, Bailey SL, et al. IL-17 contributes to generation of Th1 immunity and neutrophil recruitment during Chlamydia muridarum genital tract infection but is not required for macrophage influx or normal resolution of infection. Infect Immun. 2010 Dec 13; doi: 10.1128/IAI.00984-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu W, Li J, Chen F, Zhu H, Peng G, Chen Z. Circulating Th17 cells frequency is associated with the disease progression in HBV infected patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;25(4):750–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Nitto D, Sarra M, Cupi ML, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Targeting IL-23 and Th17-Cytokines in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(33):3656–60. doi: 10.2174/138161210794079164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guiton R, Vasseur V, Charron S, Arias MT, Van Langendonck N, Buzoni-Gatel D, et al. Interleukin 17 receptor signaling is deleterious during Toxoplasma gondii infection in susceptible BL6 mice. J Infect Dis. 2010 Aug 15;202(3):427–35. doi: 10.1086/653738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murthy AK, Cong Y, Murphey C, Guentzel MN, Forsthuber TG, Zhong G, et al. Chlamydial protease-like activity factor induces protective immunity against genital chlamydial infection in transgenic mice that express the human HLA-DR4 allele. Infect Immun. 2006 Dec;74(12):6722–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01119-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu H, Karunakaran KP, Kelly I, Shen C, Jiang X, Foster LJ, et al. Immunization with live and dead Chlamydia muridarum induces different levels of protective immunity in a murine genital tract model: correlation with MHC class II peptide presentation and multifunctional Th1 cells. J Immunol. 2011 Mar 15;186(6):3615–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rey-Ladino J, Koochesfahani KM, Zaharik ML, Shen C, Brunham RC. A live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain induces the maturation of dendritic cells that are phenotypically and immunologically distinct. Infect Immun. 2005 Mar;73(3):1568–77. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1568-1577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shaw JH, Grund VR, Durling L, Caldwell HD. Expression of genes encoding Th1 cell-activating cytokines and lymphoid homing chemokines by chlamydia-pulsed dendritic cells correlates with protective immunizing efficacy. Infect Immun. 2001 Jul;69(7):4667–72. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4667-4672.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.