Abstract

Proton coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions play an essential role in many enzymatic processes. In PCET, redox-active tyrosines may be involved as intermediates when the oxidized phenolic side chain deprotonates. Photosystem II (PSII) is an excellent framework for studying PCET reactions, because it contains two redox active tyrosines, YD and YZ, with different roles in catalysis. One of the redox active tyrosines, YZ, is essential for oxygen evolution and is rapidly reduced by the manganese-catalytic site. In this report, we investigate the mechanism of YZ PCET in oxygen evolving PSII. To isolate YZ• reactions, but retain the manganese-calcium cluster, low temperatures were used to block the oxidation of the metal cluster, high microwave powers were used to saturate the YD• EPR signal, and YZ• decay kinetics were measured with EPR spectroscopy. Analysis of the pH and solvent isotope dependence was performed. The rate of YZ• decay exhibits a significant solvent isotope effect, and the rate of recombination and the solvent isotope effect are pH independent from pH 5.0 to 7.5. These results are consistent with a rate limiting, coupled proton electron transfer (CPET) reaction and are contrasted to results obtained for YD• decay kinetics at low pH. This effect may be mediated by an extensive hydrogen bond network around YZ. These experiments imply that PCET reactions distinguish the two PSII redox active tyrosines.

Keywords: Photosystem II, EPR spectroscopy, solvent isotope exchange, manganese-calcium cofactor, water oxidation

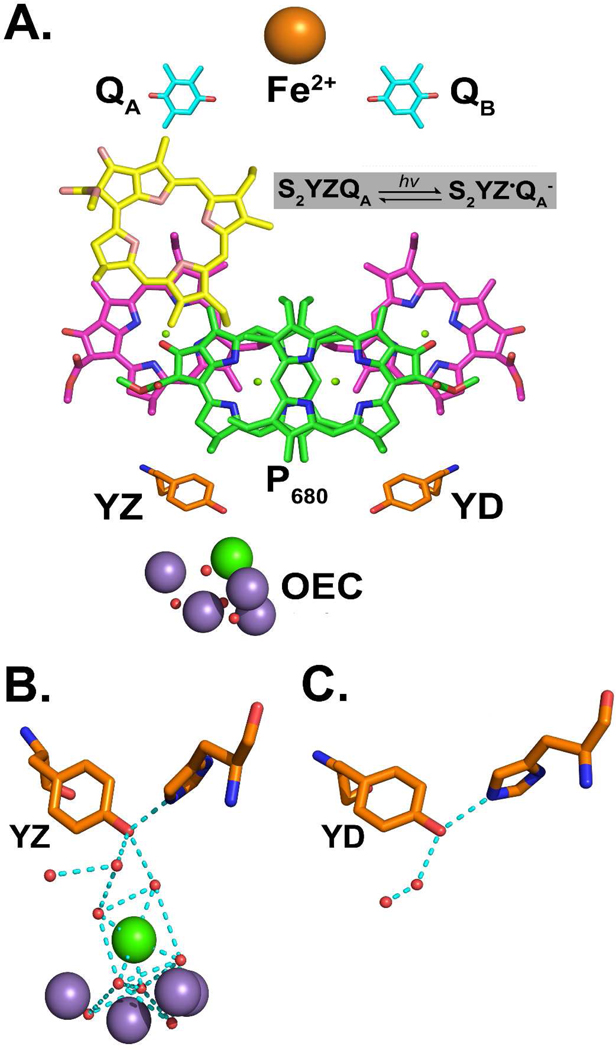

In this article, EPR spectroscopy is used to investigate YZ PCET reactions in PSII. PSII catalyzes the light driven oxidation of water at a Mn4CaO5-containing oxygen-evolving center (OEC). The transmembrane electron transfer pathway involves four chlorophylls (chl), two pheophytins, two plastoquinones, and two redox active tyrosines, YD and YZ (Figure 1A). Four flashes are required to produce oxygen from water. The OEC cycles among five Sn states, where n refers to the number of oxidizing equivalents stored.1 YD and YZ2,3 are located with approximate C2 symmetry in the reaction center.4,5 These tyrosine residues are equidistant from the chl donor, P680, and are active in PCET reactions, but play different roles in catalysis. YZ, Y161 of the D1 polypeptide, is essential for oxygen evolution.6,7 YD, Y160 of the D2 polypeptide,8,9 is not essential for catalysis, but may be involved in assembly of the OEC.10 There are other kinetic and energetic differences between the two tyrosines.11 For example, YD forms a more stable radical and is easier to oxidize.7,12 As shown in Figures 1B and C, the placement of the OEC and neighboring amino acid side chains distinguishes the two redox active tyrosines. In particular, the OEC calcium ion is located 5 Å from YZ (Figure 1B), but over 20 Å from YD (Figure 1C). An extensive set of hydrogen bonds, which link the Mn4-Ca site and YZ, is predicted. As shown in the 1.9 Å PSII structure (Figures 1B and C), hydrogen bonding helps to distinguish YZ and YD. 5

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of the PSII electron transfer pathway. After a saturating flash to a dark adapted sample at 190 K, recombination occurs between YZ• and QA− in the OEC S2 state. Hydrogen bonding environment of (B) YZ (Y161D1), showing interactions (cyan dashed lines) with predicted water molecules and H190D1 and of (C) YD (Y160D2), showing interactions with predicted water molecules and H189D2.5 Oxygen atoms are orange, manganese ions are purple, and the calcium ion is green. Hydrogen bonds were predicted using a polar contact function with an edge distance of 3.2 Å and a center distance of 3.6 Å (The Pymol Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3, Shrödinger, LLC). (B) and (C) were derived from the 1.9 Å structure from Thermosynechoccus vulcanus (3arc).5

YZ mediates electron transfer between the primary chl donor, P680, and the OEC.16 Photoexcitation of PSII produces a chl cation radical, P680+, which oxidizes YZ on the nanosecond time scale.16 If YD is available to act as an electron donor, i.e. after long dark adaptation, YD is also oxidized on the nanosecond time regime by P680+.17 YZ• is reduced by the OEC with a microsecond-millisecond rate, which depends on S state.18 The S1 to S2 transition has a barrier of 100 K, while the S0 to S1, S2 to S3, and S3 to S0 transitions occur at temperatures greater than 225 K.19 Thus, at 190 K, the S2 to S3 transition cannot occur. Acceptor side quinone molecules, QA and QB, act as electron acceptors. At 190 K, PSII is limited to one charge separation; QB is not functional.20 EPR signals from the neutral radicals, 21 YD• and YZ•, can be measured and distinguished by their decay kinetics 22,23 and by their microwave power dependence in the presence of the OEC.24

In many previous studies of YZ PCET, the OEC was removed or was absent due to biochemical manipulation of PSII. Removal of the OEC slows YZ• reduction.25 However, removal of the OEC may influence YZ PCET reactions by a conformational change or by a change in hydrogen bonding (Figure 1B). Recently, high field EPR spectroscopy suggested that there is no change in YZ• g tensor orientation when PSII crystals and OEC depleted PSII are compared.26

In this work, YZ• PCET was studied in the presence of the OEC. Oxygen-evolving PSII samples were prepared in the S1 state by dark adaptation and then illuminated at 190 K to give the S2 state. A saturating 532 nm flash was then used to generate S2YZ•QA−. The S2 state cannot act as an electron donor at this temperature, and therefore, YZ• decays by recombination with QA. The rate of the P680+QA− reaction is on the microsecond time scale in plant PSII and is pH and solvent isotope insensitive {see refs 27,28}. The YZ• and QA− recombination reaction occurs on a much longer time scale, with an overall time constant of 100–500 milliseconds in the absence of the OEC.23,29 In the presence of the OEC, the rate of YZ• and QA− recombination was similar with reported t1/2 values of 9.5 s (27%) and 0.8 (73%) s (pH 6.5, 190 K).24

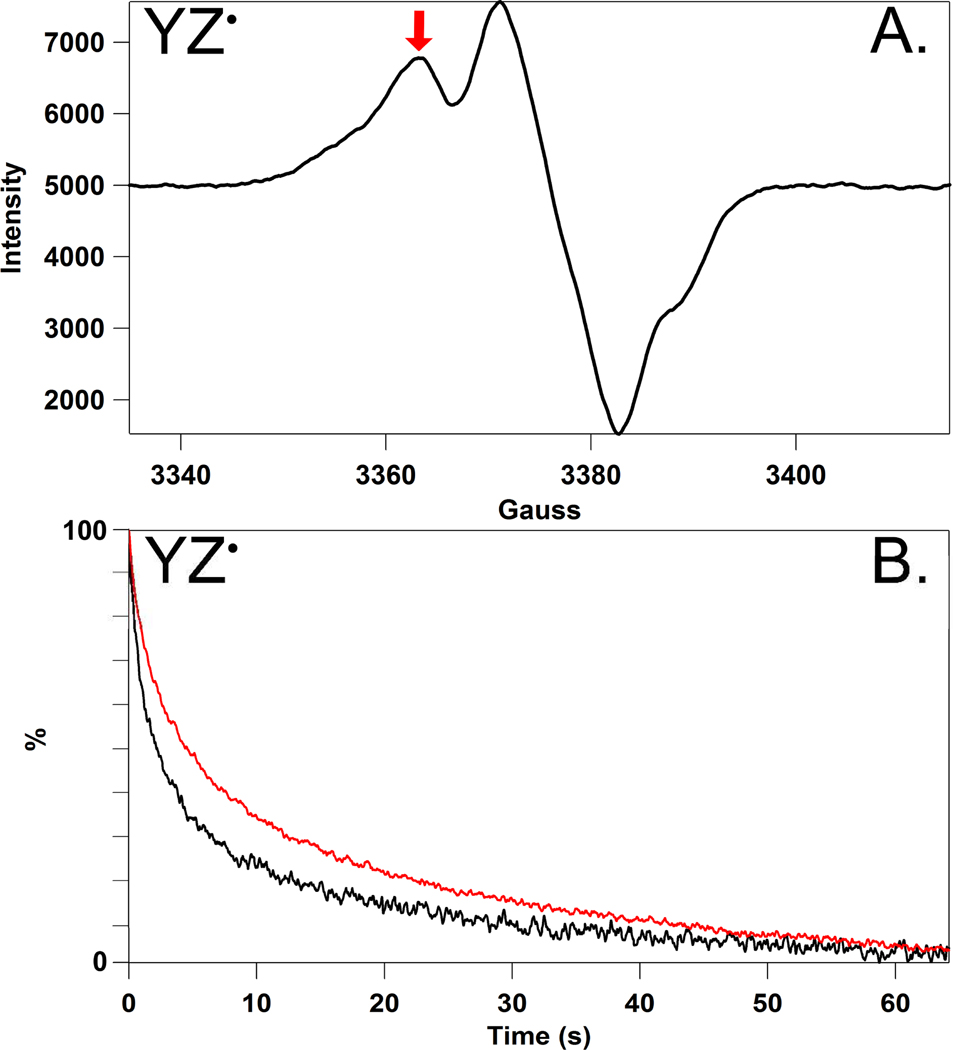

A representative field sweep spectrum of YZ• in the S2 state at 190 K is shown in Figure 2A. QA− gives rise to a spin coupled signal with an acceptor side Fe+2 ion and is not detectable under these conditions.30 The decay of YZ• was monitored by changes in EPR intensity at a fixed magnetic field (Figure 2A, arrow). Secondary electron donors, such as chl, carotenoid, and cytochrome b559, are not observed at this field position and temperature.31–34 The use of high microwave power saturates the YD• signal.24 As expected, the g value of the YZ• radical is 2.004.21,35 The YZ• spectrum and decay kinetics are similar to a previous report.24

Figure 2.

(A) Representative EPR spectrum of the S2YZ• state at 190 K and p1H 6.5. The spectrum was acquired under red-filtered illumination. The red arrow shows the magnetic field used to monitor kinetics. (B) Representative EPR transients reflecting the decay of YZ• at p1H 6.5 (black) and p2H 6.5 (red) at 190K. PSII was isolated from spinach.13 The average oxygen evolution rate was 600 µmol O2/mg chl-hr.14 The samples were solvent exchanged by repeated centrifugation at 100,000 × g in a 1H2O or 2H2O (99% Cambridge Isotopes, Andover, MA) buffer containing 0.4 M sucrose, 15 mM NaCl, and 50 mM buffer at each of the following pL values: pL 5.0 (succinate), 5.5 (succinate), 6.0 (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, MES), 6.5 (MES), 7.0 (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, HEPES), 7.5 (HEPES). Samples were stored at −70 °C. The pL is reported as the uncorrected meter reading.15 After a 20 min dark adaptation to trap the S1 state, samples were illuminated with red-filtered light (600 µmol photons/m2-s, Dolan Jenner Industries, Boxborough, MA) with 500 µM potassium ferricyanide at 190 K to generate the S2 state. Transient data at constant field were obtained following a 532 nm flash from a Continuum (Santa Clara, CA) Surelite III Nd:YAG laser. The laser intensity was 40 mJ/cm2, and the beam was expanded with a cylindrical lens. Transient data, associated with S2YZ•QA− decay, are averages from 3–5 samples; 15 transients were recorded per sample. EPR analysis was conducted on a Bruker (Billerica, MA) EMX spectrometer equipped with a Bruker ER 4102ST cavity and Bruker ER 4131VT temperature controller. EPR parameters in (A): frequency: 9.47 GHz, power: 0.638 mW, and modulation amplitude: 2 G, conversion time: 40.960 ms, time constant: 163.840 ms, sweep time: 20.972 s. EPR parameters in (B): magnetic field: 3360 G, microwave frequency: 9.47 GHz, power: 101 mW, modulation amplitude: 5 G, conversion: 20.48 ms, time constant: 164 ms. An offset, recorded from 10 s of data before the flash, was subtracted, and transients were normalized to 100% at time zero. To show that the expected YZ• hyperfine splitting is observed, the microwave power and modulation amplitude in (A) were reduced in comparison to (B).

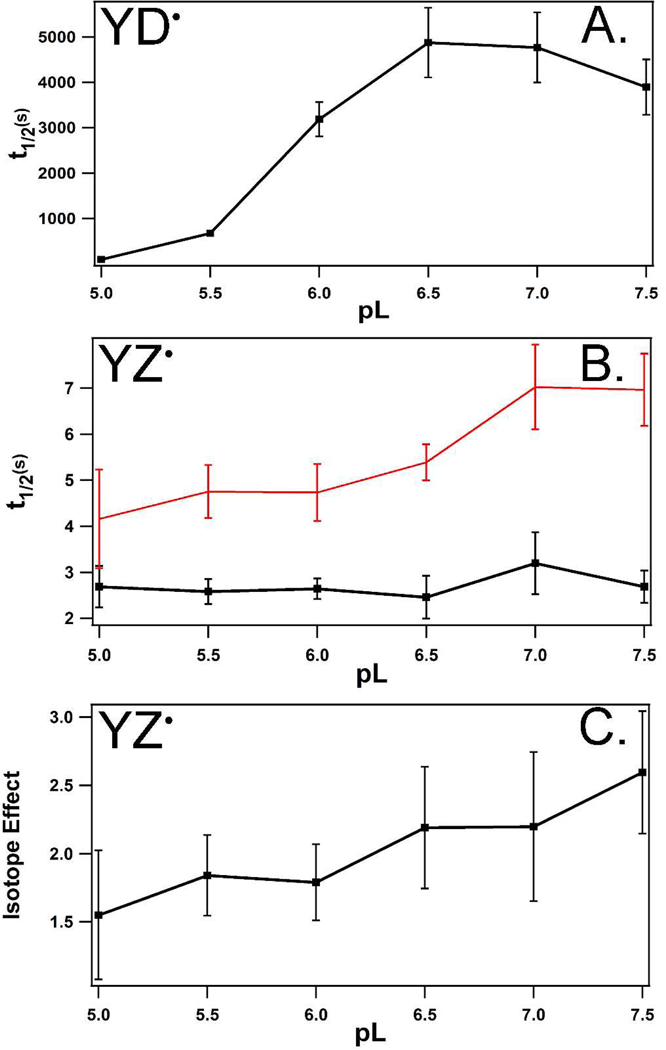

In Figure 3B, the YZ• decay kinetics were monitored, the data were fit, and the overall halftime as a function of p1H was plotted (black line). For comparison, the halftimes for YD• decay were derived from published rate constants for the majority phase,15 which are plotted in Figure 3A. While the rate of YD• decay accelerates by a factor of 10 at low p1H (Figure 3A), YZ• decay did not show significant pH dependence (Figure 3B, black line) in 1H2O buffers. YZ• decay showed only a modest pH dependence in 2H2O buffers (Figure 3B, red line). This difference may not be significant, given the error, which is estimated as one standard deviation. Over this pH range, the steady state rate of oxygen evolution was constant, and the content of extrinsic polypeptides, which interact with the OEC, was similar. Higher pL values led to activity loss and depletion of the extrinsic polypeptides (data not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) pL dependence of YD• decay, as assessed by EPR spectroscopy, attributed to YD•QA− recombination, and derived from ref 15. For pH 5.5 to 7.5, the halftime was derived from the rate constant for the majority phase, corresponding to >85% of the amplitude. For pH 5.0, the data were fit with a single exponential. (B) pL dependence of YZ• recombination in the S2 state at 190 K. Data were acquired either in 1H2O (black) or 2H2O (red) buffers. (C) pL dependence of the solvent isotope effect for YZ• recombination, derived from the data in (B).

The solvent isotope effect was calculated from the data in Figure 3B. Figure 3C shows the YZ• solvent isotope effect as a function of pL. A significant solvent isotope effect was observed from pL 5.0 to 7.5 with an average value of ~2. The value of the solvent isotope effect is pH independent, given the standard deviations. The overall magnitude is consistent with a pH independent, kinetic isotope effect (KIE) on YZ• recombination with QA−. The observation of a significant solvent isotope effect between pL 5.0 and 7.5 implies that the YZ pocket is exposed and readily accessible to water, consistent with recent X-ray crystal structures.4,5 Thus, the lack of pH dependence (Figures 3B and C) cannot be attributed to lack of accessibility. By contrast, the decay of YD• showed a ~10 fold increase in rate at low pH (Figure 3A) and a pH dependent isotope effect, with a maximum value of 2.4 at high pL.15 A proton inventory at high pL was consistent with multiple proton transfer pathways to YD•, with histidine and water molecules suggested to be the proton donors on the two different pathways.36

Phenol and tyrosine model compounds have been used to determine the mechanism of PCET reactions. PCET may occur through a concerted pathway, in which the electron and proton are transferred in one kinetic step and through one transition state (CPET). Alternatively, either the electron or proton may be transferred first (defined as ETPT or PTET, respectively). In tyrosine model compounds, a CPET mechanism has been inferred in some studies.37–40 The magnitude of the KIE and the pH dependence can be used as a first approach to distinguish these mechanisms.

For YD• reduction, the pH dependence and the kinetic isotope effect were used to argue that the mechanism is PTET at low pH and CPET at high pH.36 Unlike YD•, YZ• recombination does not show an increased rate at low pH values. The lack of significant pH dependence is not consistent with a PTET mechanism.38,40 The observation of a significant (average 2.0) kinetic isotope effect is not consistent with an ETPT mechanism.38,40 In refs 38 and 40, an isotope effect of 1.6 or greater was considered to be consistent with CPET. In ref 41, CPET in model phenols with internal hydrogen bonding was pH independent, and in ref 40, CPET in model phenols in neat water was pH independent at low pH. Therefore, our data are consistent with a CPET mechanism for YZ• reduction. The experiments also suggest that PCET mechanism distinguishes YD and YZ.

The experiments presented here focus on the mechanism of YZ• reduction. Previous work has concerned the mechanism of YZ oxidation. For OEC depleted preparations, optical studies of P680+ reduction were used to argue a CPET mechanism at low pH and a pure ET or a PTET mechanism at high pH.37,42 A pK of ~7.5 was derived from the optical data and attributed to titration of a base near YZ. As shown in Figure 1, removal of the OEC may influence PCET reactions. For OEC containing preparations, optical studies of P680+ reduction have shown no significant solvent isotope effect on nanosecond components of this reaction.43–45 A significant equilibrium isotope effect46 may explain a difference in KIE on the oxidation and reduction reaction. Low fractionation factors can occur if YZ is involved in a strong hydrogen bond, in which case deuterium will prefer the solvent.47

Model compound studies have shown that intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds facilitate CPET reactions.37–40,48,49 These reactions avoid the formation of high energy intermediates, but occur at the expense of a high reorganization energy, which is defined as the energy to reorganize from the initial to final coordinates, without charge transfer.37–40 We propose that the extensive hydrogen bonding network around YZ• and the calcium ion facilitates CPET at low pH.5 In the 1.9 Å structure, His 190 is located 2.5 Å from YZ and several water molecules, bound to calcium, are modeled, with one water at 2.6 Å (Figure 1B). The observation that recombination of YZ is not accelerated at low pH is of significance with regard to PSII activity, which must be maintained under the acidic conditions of the thylakoid lumen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH GM43273 (NIGMS and NEI) to B.A.B.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

REFERENCES

- 1.Joliot P, Kok B. In: Bioenergetics of Photosynthesis. Govindjee, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 387–412. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry BA, Babcock GT. Proc. Nat. Acad. of Sci. 1987;84:7099–7103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boerner RJ, Bixby KA, Nguyen AP, Noren GH, Debus RJ, Barry BA. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:17151–17154. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guskov A, Kern J, Gabdulkhakov A, Broser M, Zouni A, Saenger W. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:334–342. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen J-R, Kamiya N. Nature. 2011;473:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debus RJ, Barry BA, Sithole I, Babcock GT, McIntosh L. Biochemistry. 1988;27:9071–9074. doi: 10.1021/bi00426a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metz JG, Nixon PJ, Rögner M, Brudvig GW, Diner BA. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6960–6969. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debus RJ, Barry BA, Babcock GT, McIntosh L. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1988;85:427–430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermaas WFJ, Rutherford AW, Hansson Ö. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1988;85:8477–8481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ananyev GM, Sakiyan I, Diner BA, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 2002;41:974–980. doi: 10.1021/bi011528z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry BAJ. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2011;104:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boussac A, Etienne AL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;766:576–581. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berthold DA, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. FEBS Letters. 1981;134:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry BA. Meth. Enzym. 1995;258:303–319. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)58053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenson D, Evans A, Barry BA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:12599–12604. doi: 10.1021/jp075726x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerken S, Brettel K, Schlodder E, Witt HT. FEBS Letters. 1988;237:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faller P, Debus RJ, Brettel K, Sugiura M, Rutherford AW, Boussac A. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:14368–14373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251382598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babcock GT, Blankenship RE, Sauer K. FEBS Letters. 1976;61:286–289. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)81058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Styring S, Rutherford AW. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;933:378–387. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Paula JC, Innes JB, Brudvig GW. Biochemistry. 1985;24:8114–8120. doi: 10.1021/bi00348a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry BA, El-Deeb MK, Sandusky PO, Babcock GT. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:20139–20143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S, Barry BA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13882–13892. doi: 10.1021/bi981318v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala I, Kim S, Barry BA. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2137–2144. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77054-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ioannidis N, Zahariou G, Petrouleas V. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6292–6300. doi: 10.1021/bi800390r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babcock GT, Sauer K. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1975;376:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(75)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka H, Shen J-R, Kawamori A, Nishiyma K, Ohba Y, Yamauchi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4655–4660. doi: 10.1021/ja2000566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diner BA, Force DA, Randall DW, Britt RD. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17931–17943. doi: 10.1021/bi981894r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Wijn R, van Gorkom HJ. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11912–11922. doi: 10.1021/bi010852r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekker JP, van Gorkom HJ, Brok M, Ouwehand L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;764:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutherford AW, Zimmermann JL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;767:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald GM, Boerner RJ, Everly RM, Cramer WA, Debus RJ, Barry BA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4393–4400. doi: 10.1021/bi00180a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald GM, Steenhuis JJ, Barry BA. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8420–8428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buser CA, Diner BA, Brudvig GW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11449–11459. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanley J, Deligiannakis Y, Pascal A, Faller P, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8189–8195. doi: 10.1021/bi990633u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayala I, Range K, York D, Barry BA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:5496–5505. doi: 10.1021/ja0164327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenson D, Barry BA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10567–10573. doi: 10.1021/ja902896e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sjödin M, Styring S, Akermark B, Sun L, Hammarström L. J. Am.Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3932–3936. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer JM, Rhile IJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1655:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irebo T, Reece SY, Sjödin M, Nocera DG, Hammarström L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15462–16464. doi: 10.1021/ja073012u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonin J, Costentin C, Louault C, Robert M, Routier M, Savéant J-M. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3367–3372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914693107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sjödin M, Irebo T, Utas JE, Lind J, Merényi G, Akermark B, Hammarström L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13076–13083. doi: 10.1021/ja063264f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rappaport F, Boussac A, Force D, Peloquin J, Bryndal M, Sugiura M, Un S, Britt D, Diner B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4425–4433. doi: 10.1021/ja808604h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karge M, Irrgang K-D, Renger G. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8904–8913. doi: 10.1021/bi962342g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haumann M, Bogershausen O, Cherepanov D, Ahlbrink R, Junge W. Photosynth. Res. 1997;51:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schilstra MJ, Rappaport F, Nugent JHA, Barnett CJ, Klug DR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3974–3981. doi: 10.1021/bi9713815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schowen KB, Schowen RL. Meth. Enzym. 1982;87:551–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cleland WW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:317–319. doi: 10.1021/bi00117a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammes-Schiffer S, Soudackov AV. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:14108–14123. doi: 10.1021/jp805876e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irebo T, Johansson O, Hammarström L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9194–9195. doi: 10.1021/ja802076v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]