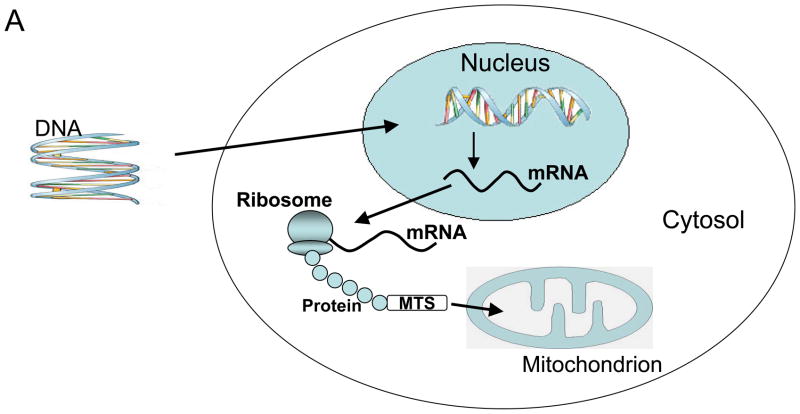

Mitochondria are cytosolic double-membrane-bound organelles found in eukaryotic cells which are involved in diverse cellular processes such as oxygen sensing, apoptotic cell death regulation, reactive oxygen species production and signaling, and ATP production. The mitochondrial proteome (a sum of all polypeptides found in this organelle) is dynamic, and its particular composition is believed to depend upon both the cell type and physiological state of the cell (1). It has been estimated to consist of at least 1500 polypeptides (2, 3), of which only 13 are encoded by mtDNA. Therefore, greater than 99% of mitochondrial proteins are encoded in the nucleus and imported into mitochondria after being synthesized on cytoplasmic ribosomes. Mitochondrial function and the mitochondrial proteome are altered in many pathological conditions such as mitochondrial diseases, diabetes, cancer, and aging. Therefore, manipulation of the mitochondrial proteome has many applications in both basic research, and as a therapeutic tool. This review will cover experimental strategies aimed at altering the composition of the mitochondrial proteome which can be divided in two broad groups: (I) methods based on DNA delivery to the nucleus, and (II) methods based on protein delivery to mitochondria (Fig.1). Even though delivery of the functional DNA to mitochondria represents an area of very active research, these approaches will not be covered here (for recent reviews and reports see (4–9)).

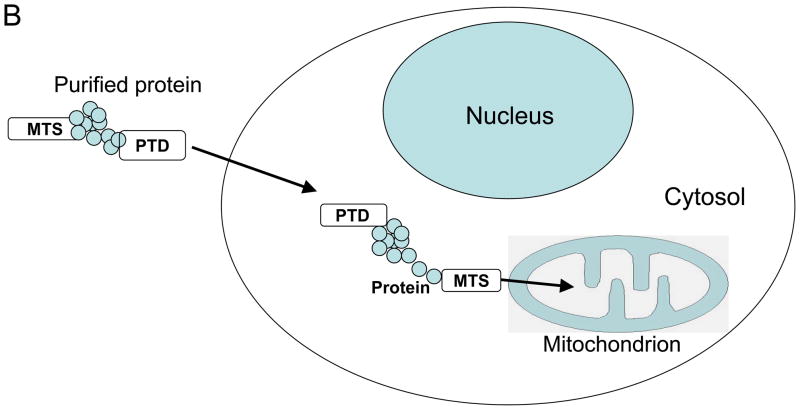

Fig. 1.

I. Methods based on DNA delivery to the nucleus

These methods take advantage of the natural import pathways used by nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins. Early studies on mitochondrial protein import revealed that proteins targeted to the mitochondrial matrix contain N-terminal presequences, which are cleaved upon import (10, 11). In 1984 Hurt et al. attached a presequence of the precursor to yeast cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (an imported mitochondrial protein) to the amino-terminus of the cytosolic protein dihydrofolate reductase. The resulting fusion protein was imported into the matrix of isolated, energized yeast mitochondria and cleaved to a polypeptide whose size was similar to that of authentic dihydrofolate reductase (12, 13). These observations indicated that cleavable presequences are both necessary and sufficient for the import of polypeptides to the mitochondrial matrix, and opened an avenue for the targeting of proteins to mitochondria. Subsequent studies identified many key components of the mitochondrial protein import machinery and provided a better understanding of this process (reviewed in (14, 15)).

Generally speaking, there are at least four different pathways for protein import into the mitochondria (14):

The presequence pathway. This pathway is by far the major one for mitochondrial protein import (16), is best studied and is used to deliver proteins to the mitochondrial matrix, the inner membrane, and the intermembrane space. Presequences, or matrix targeting signals (MTSs), are N-terminal amphipathic α-helices, typically 15–50 amino acid residues (range <10 to ~100), which are removed by a mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) upon import. The presequence directs attached proteins to the matrix. The inner membrane and intermembrane space proteins that use this pathway usually have either a non-cleavable or a cleavable hydrophobic sorting signal that follows the MTS (17–19). The initial cleavage of the MTS is often followed by additional processing of N-termini by proteases such as Oct1 (18) or Icp55 (16), thus contributing to the diversity of the N-termini and obscuring the specificity of the MPP.

The carrier protein pathway. This pathway is used by mitochondrial inner membrane proteins of the carrier family. The proteins that use this pathway have a number of non-cleavable internal signals.

The redox-regulated import pathway. This pathway employs a redox relay formed by Mia40 and Erv1, and targets proteins with conserved cysteine motifs to the intermembrane space (15, 20, 21).

The β-barrel pathway. This pathway targets proteins to the mitochondrial outer membrane (14, 15).

However, despite the availability of a variety of pathways for mitochondrial polypeptide targeting, the presequence pathway is almost exclusively employed for the purpose of experimental mitochondrial delivery. In part, this is due to the fact that this pathway uses distinct and well-defined signal sequences, and in part due to the ability to deliver, through this pathway, proteins to all three major compartments affected by mitochondrial deficiencies: the matrix, the inner membrane, and the intermembrane space. Typically (Fig.1A), a DNA sequence encoding one of a variety of available MTSs is attached by recombinant DNA techniques to the 5’ end of the gene encoding the protein of interest, and this chimerical construct, under control of an appropriate promoter, is delivered to the nucleus by one of a variety of viral or non-viral delivery approaches. Upon transcription, the resulting mRNA is translated on the cytoplasmic ribosomes, a nascent presequence is recognized by cytoplasmic chaperones, and the protein is targeted to the mitochondrial outer membrane, where it is recognized by the TOM40 complex and imported.

Specific approaches for manipulation of the mitochondrial proteome using nuclear delivery of DNA will be further discussed within the following groups:

Overexpression of nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins

Allotopic expression – expression of re-coded mitochondrial genes from the nucleus

Optimized allotopic expression

Xenotopic expression – expression of ETC components from other species in mammalian mitochondria

Antigenomic strategies

Progenomic strategies

Overexpression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins

This approach is used to enhance (overexpression of the wild type mitochondrial protein) or suppress (overexpression of dominant-negative mitochondrial protein) a specific mitochondrial pathway. Therapeutically, this approach is used for the correction of disorders caused by mutant mitochondrial proteins, as in the case of the correction of ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, a liver disease resulting from a mutation in the gene encoding a urea cycle enzyme, OTC. In one study, OTC-deficient mice were infused with adeno-associated virus vectors encoding either wild-type OTC or LacZ. This treatment restored urea orotate levels to virtually normal 15 days after infusion, which persisted for 1 year post-treatment. Animals receiving OTC-expressing vectors lived longer than untreated controls, and they were tolerant to a challenge with ammonia after 21 days and beyond, which caused severe morbidity in control OTC-deficient animals (22). Another example of this approach is an overexpression of human mitochondrial valyl tRNA synthetase, which leads to partial restoration of the levels of the cognate mt-tRNAVal carrying a pathogenic C25U mutation (23). This mutation results in rapid degradation of deacylated mt-tRNAVal, leading to a respiratory chain deficiency. By overexpressing mitochondrial valyl tRNA synthetase in transmitochondrial cell lines, the authors were able to partially restore steady-state levels of the mutated mt-tRNA(Val) consistent with an increased stability of the charged mt-tRNA (23).

Allotopic expression

For a diverse group of mitochondrial diseases associated with mutations in mtDNA, the possibility of expressing mtDNA-encoded genes in the nucleus (allotopic expression) provides hope for the development of treatment strategies for these hard to treat disorders. The feasibility of this approach was first demonstrated in a yeast model. Respiratory-deficient mutants of C.cerevisiae lacking endogenous ATPase subunit 8 were rescued when a normal copy of the gene, re-coded for nuclear expression and supplied with an MTS for mitochondrial import, produced a polypeptide that successfully incorporated into the mitochondrial ATPase (Complex V) and restored its function (24). Since then, allotopic expression has been tried in human cells. The T8993G mutation is responsible for defective ATPase 6 in Complex V of the respiratory chain which causes impaired ATP synthesis in two related mitochondrial disorders: neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP), and maternally inherited Leigh syndrome (MILS). Manfredi et al. expressed a wild-type ATPase 6 protein in the nucleus which was imported into mitochondria and incorporated into complex V in cybrids homoplasmic with respect to the T8993G mutation. Stable transfectants demonstrated an improved recovery after growth in selective medium as well as a significant increase in ATP synthesis (25). The same strategy was used to rescue cybrids with the mtDNA point mutation G11778A in the gene encoding the ND4 subunit of Complex I, which is responsible for Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON). Treated LHON cybrids showed a 3-fold increase in ATP synthesis, to a level comparable to cybrids with normal mtDNA (26). More recently, a variant atp6 gene resistant to oligomycin was introduced into both a CHO cell line and NARP cybrids, conferring a significant growth advantage in the presence of an otherwise lethal concentration of oligomycin (27). However, this study did not investigate ATP production levels or other mitochondrial functions, so it is not clear whether the deficiencies associated with the NARP mutation were alleviated. Later, a different group, in a more extensive study, attempted an allotopic introduction of ATPase6 into human NARP cybrids, trying both algal and human atp6 genes. They showed no evidence of improved mitochondrial function, and no assembly into ATP synthase for either subunit (28). As indicated by the authors, the ATP synthase subunit 6 is one of the most difficult mitochondrial genes to express from the nucleus, but they remain optimistic about the potential for allotopic expression as a treatment method.

Optimized allotopic expression

An intriguing approach to improve the allotopic expression of highly hydrophobic proteins was proposed by Corral-Dobrinski and colleagues. They incorporated cis-acting 3’-UTR elements from the transcripts of nuclear proteins, normally imported into mitochondria, into the allotopic mRNA to force it to localize to the surface of mitochondria, thus facilitating co-translational import (29). For their study, they used primary fibroblasts from patients with NARP or LHON mutations. The re-coded ATP6 gene was associated with the cis-acting elements of SOD2, while the ND4 gene was associated with cis-acting elements of COX10. Both ATP6 and ND4 products were efficiently translocated into the mitochondria and functional within their respective respiratory chain complexes. Transfections resulted in the rescue of respiratory chain defects evidenced by restoration of ATP production and growth on galactose as a sole carbon source which requires an efficient respiration (30). They used a similar strategy, in subsequent work to confirm the restoration of respiratory chain Complex I activity in fibroblasts from LHON patients with homoplasmic mutations in either ND4 or ND1 genes (31). The same group recently extended their investigation to an in vivo model. In this proof-of-principle study, they created a rat model of LHON by using in vivo electroporation to introduce a mutant ND4 construct into the rat eye. The resulting allotopic expression of the deficient Complex I subunit induced the degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and a decline in visual performance. A subsequent electroporation with wild-type ND4 prevented both retinal ganglion cell loss and blindness in animals (32). In the future, the authors plan to assess long-term safety and efficacy of this optimized allotopic-expression approach using adeno-associated virus-mediated gene therapy in large animals. These studies may lead to a potential breakthrough in treatment of mitochondrial optic neuropathies.

Xenotopic expression

The term “xenotopic expression” was introduced by Ojaimi et al. to describe an approach for “trans-kingdom” allotopic expression using Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ATPase 6 for successful introduction into mitochondria of human cybrids harboring the NARP mutation (33). In this review, this term will be used when discussing strategies to circumvent defects in the respiratory chain resulting from mtDNA mutations by expressing single-subunit respiratory enzymes from other species and importing them into the defective mammalian mitochondria.

In contrast to mammals who pack 45 protein subunits and other components into Complex I, the mitochondria of S. cerevisiae lack Complex I entirely and instead contain single-subunit rotenone-insensitive NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductases. The S. cerevisiae Ndi1p is a single polypeptide chain that is able to carry out the electron transport function of Complex I with no electron leakage and ROS production. Earlier experiments with the yeast Ndi1 protein show that it can replace or supplement the functionality of Complex I in various cultured cells. It can restore NADH oxidase activity in Complex I deficient Chinese hamster cells (34) or in human C4T cells, which contain a homoplasmic frameshift mutation in the mitochondrial ND4 gene (35, 36). An adeno-associated virus vector system has been used to successfully deliver and express the NDI1 gene in non-proliferating human cells (37). In the first successful in vivo study, viral-mediated delivery and expression of NDI1 gene in the substantia nigra was shown to be beneficial in a murine model of chemically-induced Complex I deficiency that mimics Parkinson’s disease (38). More recently, data from the Yagi group demonstrate the protective effects of Ndi1 protein expression in a rotenone rat model of Parkinson’s disease (39). Additionally, the long-term (8 months) expression of Ndi1p in mitochondria of mouse neurons does not elicit an immune reaction (40).

Another interesting case of xenotopic expression of a respiratory chain protein in human cells involves a cyanide-insensitive alternative oxidase (AOX) from the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis. AOX is widely distributed across kingdoms but is absent in vertebrates. AOX is a single polypeptide oxidase which passes electrons from ubiquinol directly to molecular oxygen, thus bypassing Complexes III and IV of the OXPHOS system (41). In 2006, Hakkaart et al. successfully engineered AOX for expression in human embryonic kidney cells, demonstrating that the polypeptide is targeted to mitochondria and can restore electron flow to oxygen when the cytochrome portion of the respiratory chain is inhibited by poisons such as cyanide or antimycin (42). In subsequent work, lentiviral-mediated expression of AOX in COX15 mutant fibroblasts from a patient with early fatal cardiomyopathy corrected the various consequences of cytochrome c oxidase deficiency , such as decreased cell respiration and glucose and pyruvate dependency (43). For OXPHOS defects where reduced ATP production is not the key factor underlying the pathological effects, such as ROS overproduction or metabolic acidosis, AOX expression may present a potential treatment strategy. Future studies in this area will likely focus on the creation of AOX transgenic mice, as well as a wide variety of models of OXPHOS dysfunction, to test for possible use of AOX in gene therapy (44).

In the list of strategies based on DNA delivery to the nucleus, there is an alternative allotopic/xenotopic expression which involves expression of tRNA by nuclear genes and its import into mammalian mitochondria. tRNA import into mitochondria is now considered almost universal. It has been found in fungi, plants, protozoans and mammals (45, 46). Doubts about the existence of a natural tRNA import pathway in human mitochondria seem to have been answered in a recent work by Rubio et al. (47). Interest in tRNA import arises from the fact that many mitochondrial disorders are caused by mutations in mitochondrial tRNA genes. Thus, importing normal copies of tRNAs into mitochondria may be a potential treatment strategy for such defects. Recent advances in this field include expression of yeast tRNALys derivatives and their import in mitochondria, which partially rescued mitochondrial deficiency caused by a mutation in human mitochondrial tRNALys which is associated with Myoclonic Epilepsy and Red Ragged Fibers (MERRF) syndrome (48). A completely different approach by another group utilized a tRNA import mechanism of a protozoan parasite Leishmania. A purified multiprotein import complex RIC from Leishmania was added to the media of cultured human cells, at which point the whole complex was taken up by caveolin-dependent endocytosis and targeted to the mitochondrial inner membrane, where it induced the import of endogenous tRNAs from the cytosol. This elaborate process rescued mitochondrial deficiencies caused by two tRNALys mutations (MERRF and another associated with the Kearns Sayre Syndrome or KSS) (49).

Antigenomic strategies

The term antigenomic refers to the strategies aimed at altering expression of genes encoded by mitochondrial genomes (or by a subset thereof) through either reducing their copy number, or through reducing their “fitness” (e.g., through compromising mtDNA maintenance and repair). Because many mitochondrial diseases caused by mtDNA mutations are heteroplasmic (i.e., wild type and mutant mitochondrial genomes coexist in a patient’s cells), selective destruction of mutant genomes or reduction of their copy number below the threshold for manifestation of clinical symptoms represents an attractive treatment strategy. In 2001, Srivastava and Moraes (50) transfected cybrid cells heteroplasmic for mouse (2 PstI sites) and rat (no PstI sites) mtDNA with a construct encoding mitochondrially-targeted PstI restriction endonuclease (mtPstI). As a result, the heteroplasmy has shifted in favor of the rat mtDNA in clones with detectable expression of mtPstI. This was the first demonstration of proof-of-principle. Subsequently, Tanaka et al. (51) have demonstrated the applicability of this strategy to a relevant human disease, NARP. They transiently transfected cybrids containing the T8993G mutation in mtDNA (this mutation creates a unique recognition site for the SmaI/XmaI restriction endonucleases) with a construct encoding mitochondrially-targeted SmaI. This treatment effectively eliminated the mutant mitochondrial genomes.

We have extended this strategy by incorporating a construct encoding mitochondrially-targeted XmaI restrictase along with nuclear SmaI methyltransferase (for the protection of nuclear DNA from mistargeted XmaI) into an adenoviral vector (52). Infection of cybrid cells containing the NARP mutation with this vector led to selective destruction of the mutant mtDNA. This destruction proceeded in a time- and dose-dependent manner and resulted in cells with significantly increased rates of oxygen consumption and ATP production. The delivery of XmaI restrictase to mitochondria was accompanied by improvement in the ability to utilize galactose as the sole carbon source, which is a surrogate indicator of the proficiency of oxidative phosphorylation. Concurrently, the rate of lactic acid production by treated cells, which is a marker of mitochondrial dysfunction, decreased. Importantly, this study has demonstrated that treatment of a mitochondrial disease with a mitochondrially-targeted restriction endonucleases is not subject to two of the most common limitations of somatic gene therapy, as it requires neither long-term transgene expression (because the effect is essentially complete within 48h of infection) nor does it require infection of a high proportion of the target cells (because multiple infections with low doses of adenovirus led to a gradual reduction of the mutant mtDNA content) (52).

One important limitation of this strategy is the availability of restriction nucleases specific for pathogenic mutations in mtDNA. However, this limitation recently has been overcome by using zinc-finger nucleases (53). These nucleases can be “designed” to recognize virtually any DNA sequence (54), thus removing the only remaining limitation to selective elimination of mutant mtDNA species with mitochondrially-targeted nucleases.

The expression of the mtDNA genome can be negatively altered not only by targeted destruction of mtDNA with nucleases, but also by reducing its “fitness”, i.e.: mitochondria’s ability to repair mtDNA. So far, there have been a limited number of studies demonstrating the feasibility of this approach. Thus, expression of mitochondrially-targeted but not cytosolic E. coli Exonuclease III in the MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line resulted in the impairment of the mtDNA repair following oxidative stress. This diminished mtDNA repair capacity sensitized cells to oxidative damage, and led to a decrease in their long-term survival following oxidative stress (55). In another set of studies, mitochondrial targeting of N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase (MPG), which is responsible for the removal of damaged bases such as 3-methyladenine and 1,N(6)-ethenoadenine from the DNA after alkylation, resulted in a dramatic increase in the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to methyl methanesulfonate (56). This increased sensitivity is due to the conversion of non-toxic 7-meG lesions into highly toxic repair intermediates (57).

Progenomic strategies

An approach for gene targeting with the goal of boosting protection of mtDNA against damage is a progenomic strategy. Even under normal physiological conditions, mtDNA is at high risk of being damaged oxidatively due to its close proximity to sites of ROS production in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Considering the continuous turnover of mtDNA molecules even in post-mitotic tissues, it should come as no surprise that mtDNA has high mutation rates (58, 59). One way to prevent the accumulation of mutations in mtDNA would be to increase its repair capacity. In a number of successful attempts undertaken over the past several years, DNA repair enzymes, members of Base Excision Repair (BER) pathway, were expressed in the nucleus and imported into mitochondria. 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) recognizes and removes 8-oxo-G, an oxidized derivative of guanine, from DNA. The gene for human OGG1 engineered to contain an MTS from manganese superoxide dismutase was stably expressed in HeLa cells. This caused an increase in the amount of hOGG1 protein in mitochondria. Cells expressing recombinant hOGG1 had improved mtDNA repair and displayed increased cellular survival following oxidative stress (60, 61). A similar protection was obtained by targeting hOGG1 into mitochondria of rat pulmonary artery endothelial cells (62). Targeting hOGG1 to mitochondria of rat oligodendrocytes enhanced mtDNA repair and protected cells against caspase 9-dependent apoptosis after menadione-induced oxidative stress (63) and cytokine-mediated damage (64). Another BER enzyme, AP endonuclease, works to remove abasic sites in DNA. When the yeast AP endonuclease Apn1 was expressed in mitochondria of a neuronal cell line derived from rat substantia nigra, it promoted the repair of oxidative lesions in mtDNA and enhanced resistance to cell death following oxidative insult (65). The bacterial DNA repair enzymes Endonucleases III and VIII recognize and remove oxidative lesions in pyrimidines. Expressing both enzymes as fusions with an MTS from human MnSOD increased resistance of HeLa cells to oxidative stress (66). In addition, mitochondrial overexpression of the enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, which removes certain types of alkylation damage, has been shown to increase cell survival after treatment with DNA alkylating agents (67, 68).

Technical aspects of mitochondrial targeting using intrinsic mitochondrial import pathways

The apparent simplicity of mitochondrial delivery of therapeutic polypeptides using a presequence pathway is, however, deceiving and two related caveats must be taken into consideration when designing experiments of this kind.

First, not all MTSs are equal, and the same MTS may mediate efficient mitochondrial import of some proteins, but not others. Thus, it has been observed that the MTS of yeast mitochondrial superoxide dismutase can efficiently target mouse dihydrofolate reductase (cytosolic protein) to yeast mitochondria both in vitro and in vivo. However, a fusion between this MTS and yeast cytosolic invertase protein, which is three times larger than dihydrofolate reductase, failed to enter mitochondria, and 95% of the fusion protein accumulated in the cytoplasm when expressed in yeast cells (69). Recently, we used two derivatives of the red fluorescent protein from Discosoma sp., DsRed Express (DRE) and mCherry, which are different in only 25 amino acid positions, to study this phenomenon more closely. The MTSs differed in their ability to deliver these two proteins to the mitochondrial matrix. MTSs from superoxide dismutase and DNA polymerase γ failed to direct mCherry, but not DRE to mitochondria (70). By evaluating a series of chimeras between mCherry and DRE fused to the MTS of superoxide dismutase, we were able to attribute the differences in the mitochondrial partitioning to differences in the primary amino acid sequence of the passenger polypeptide. The impairment of mitochondrial partitioning closely paralleled the number of mCherry-specific mutations, and was not specific for mutations located in any particular region of the polypeptide. Our results (70) are also consistent with the notion that the MTS may in fact mediate effects on mitochondrial import exerted by the C-terminal sequences of the passenger polypeptide (71) and by the sequences that immediately follow the MTS (72). Similarly, Waltner et al. observed that the N-terminal 23 residues of the matrix enzyme rhodanese could import several passenger proteins, but were unable to import the mature form of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (mALDH). However, if these same 23 residues were fused to the middle portion of mALDH, import was recovered, suggesting that the rhodanese signal sequence and N terminus of mALDH were incompatible for import (73). Also, Janiak et al. concluded that although the primary determinant of subcellular targeting specificity is the targeting motif, translocation competence of the passenger polypeptide augments the fidelity of transport (74).

The second caveat is related to a growing appreciation of the phenomenon of “eclipsed” distribution. Thus, yeast aconitase, an enzyme synthesized with an MTS and targeted to mitochondria, also is present in small quantities in the cytosol (75). Similarly, in human and yeast cells fumarase is found in both the cytosol and mitochondria (76). Again, in this instance the presence of the MTS does not ensure exclusive mitochondrial localization of the enzyme. Perhaps even more dramatic is the example of yeast Nfs1p, which has both an MTS and nuclear localization sequence (NLS). While the protein is only detectable in the mitochondria, a mutation in the putative NLS is lethal. This lethal phenotype can be rescued by expression of a truncated protein, which lacks an MTS (77). These observations suggest not only that a fraction of Nfs1p, despite the presence of the MTS, is (mis)localized to the nucleus, but also that nuclear Nfs1p is essential for viability. These findings highlight the phenomenon of the presence of multiple subcellular targeting signals in a single polypeptide. Other examples of this phenomenon include mitochondrial transcription factor A (78) and 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (79). The localization of the subunits of the mitochondrial ATP synthase to the lipid rafts of the plasma membrane is well documented (80, 81), yet its functional significance remains enigmatic. While it has been shown that the ectopic β-subunit of the ATP synthase serves as a high-affinity receptor for High Density Lipoprotein and is even active as an ATP hydrolase in hepatocytes (82), the functional role for the plasma membrane ATP synthase in other cell types remains to be determined.

Currently, the properties of MTS and passenger polypeptide contributing to the efficiency of mitochondrial import are poorly understood, and targeting of any new protein to mitochondria remains a trial-and-error exercise. Therefore, any experiment aiming to establish an effect of mitochondrial targeting of a protein should control for the effects of cytoplasmic expression of this protein in anticipation that a fraction of overexpressed protein inevitably will be retained in the cytosol.

Finally, there is emerging evidence that function of the MTS is not always limited to mitochondrial targeting. Thus, in mammals, subunit c of the F1F0-ATP synthase has three isoforms (P1, P2, P3). These isoforms differ by their cleavable mitochondrial targeting peptides, while the mature peptides are identical. Recently, Manfredi’s group has investigated this apparent genetic redundancy by knocking down each of the three subunit c isoforms by RNA interference in HeLa cells (83). Silencing any of the subunit c isoforms individually resulted in an ATP synthesis defect, indicating that these isoforms are not functionally redundant. Because the expression of exogenous P1 or P2 was able to rescue the respective silencing phenotypes, but the two isoforms were unable to cross complement each other, the authors hypothesized that their functional specificity resided in their targeting peptides. In fact, the expression of P1 and P2 targeting peptides fused to GFP variants rescued the ATP synthesis and respiratory chain defects in the silenced cells. This report provides the first experimental evidence that targeting peptides, in addition to mediating mitochondrial protein import, may play an as yet undiscovered role in respiratory chain maintenance (83).

II. Delivery of purified proteins to mitochondria

Delivery of proteins to mitochondria is one of the applications of the more general phenomenon called protein transduction. As has been discussed in the preceding paragraphs, the ability to deliver recombinant proteins to mitochondria has potential therapeutic value. Until recently, the ability to ectopically express novel proteins that have a therapeutic benefit was largely limited to the transfer of genes into eukaryotic cells, either using viral vectors or non-viral mechanisms such as microinjection, electroporation or chemical transfection. These approaches remain problematic, especially in vivo where gene delivery by adenoviral vectors is associated with significant difficulties relating to limited specificity and toxicity. An alternative approach involves delivering therapeutic proteins directly into cells. The recent identification of a group of proteins with enhanced ability to cross the plasma membrane in a receptor-independent fashion has led to a discovery of a class of protein domains with cell membrane-penetrating properties called Protein Transduction Domains (PTDs, also called cell-penetrating peptides CPPs). The fusion of these PTDs with the sequences of heterologous proteins is sufficient to cause their translocation into a variety of different cells in a concentration-dependent manner (84, 85). In fact, for the past several years there has been an explosion in research that has successfully exploited the ability of various PTDs to deliver a broad range of therapeutics, including proteins, DNA, antibodies, oligonucleotides, imaging agents and liposomes, into a variety of situations and biological systems (for recent reviews see (86–88)). One such PTD is the TAT domain, an 11 amino acid peptide derived from the HIV Tat protein. Recently, data coming from several groups has shown that the TAT PTD can be used in fusion with mitochondrially-targeted proteins to translocate them through the cell membrane first, then to deliver them to mitochondria (Fig.1B). Asoh et al. fused the FNK, an enhanced version of the antiapoptotic Bcl-xL, to a TAT PTD and added it to cultured neurons. PTD-FNK rapidly transduced into cells and localized to mitochondria, where it protected neurons against apoptosis (89). Later this group extended their studies to in vivo models to show that PTD-FNK successfully protected cells from cell death induced by a number of pathological conditions including ischemic injury to the brain (90), heart (91), and liver (92), toxic injury to lungs (93), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (94). Del Gaizo et al. used the fusion of GFP with the TAT PTD and MTS from mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase (mMDH). TAT-mMDH-GFP allowed rapid transduction and localization of fusion protein to mitochondria of multiple cell types in vitro and, when injected in mice, it localized in multiple tissue types. Furthermore, fusion protein injected into pregnant mice crossed the placenta and was detectable in both the fetus and the newborn pups (95, 96). Shokolenko et al. showed mitochondrial delivery of Exonuclease III from E.coli in fusion with the TAT PTD and the N-terminal MTS from MnSOD. The transduced protein was effectively internalized by MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and subsequently targeted to mitochondria, where it decreased the repair of mtDNA, rendering the cells more susceptible to a oxidative stress (97). More recently, Rapoport et al. used protein transduction technology to develop a therapeutic approach for restoring the activity of multienzymatic complexes in mitochondrial deficiency disorders by directly delivering a wild-type enzyme into the cells and their mitochondria. Their fusion protein consisted of a TAT PTD fused to the wild-type human lipoamine dehydrogenase (LAD), which is a component of the multisubunit α-ketoacid dehydrogenase and is mutated in LAD deficiency, a severe neurodegenerative disorder. The results obtained with cultured cells from patients indicate that TAT-LAD was able to enter cells and their mitochondria rapidly and efficiently, and it was able to restore LAD activity to normal levels (98). In another example of mitochondrial protein delivery using protein transduction, a stretch of 11 arginines was used as a PTD combined with an additional MTS from MnSOD fused to the mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM. The PTD-MTS-TFAM construct designated MTD-TFAM was successfully transduced into cells and delivered into mitochondria in vitro and in vivo. It was able to increase the basal respiration rate in cybrid cells carrying a LHON mutation, and also in brain and skeletal muscle cell mitochondria isolated from MTD-TFAM treated mice (99).

In summary, it is becoming increasingly clear that mitochondria play a critical role in the pathogenesis of many human diseases. It is likely that some of the approaches described in this review will be employed in the near future to prevent or slow the progression of some of these diseases.

References

- 1.Mootha VK, Bunkenborg J, Olsen JV, Hjerrild M, Wisniewski JR, Stahl E, Bolouri MS, Ray HN, Sihag S, Kamal M, Patterson N, Lander ES, Mann M. Integrated analysis of protein composition, tissue diversity, and gene regulation in mouse mitochondria. Cell. 2003;115:629–640. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00926-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor SW, Fahy E, Ghosh SS. Global organellar proteomics. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:82–88. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor SW, Fahy E, Zhang B, Glenn GM, Warnock DE, Wiley S, Murphy AN, Gaucher SP, Capaldi RA, Gibson BW, Ghosh SS. Characterization of the human heart mitochondrial proteome. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nbt793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle SR, Chan CK. Mitochondrial gene therapy: an evaluation of strategies for the treatment of mitochondrial DNA disorders. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1335–1348. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Souza GG, Boddapati SV, Weissig V. Gene therapy of the other genome: the challenges of treating mitochondrial DNA defects. Pharm Res. 2007;24:228–238. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9150-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katrangi E, D'Souza G, Boddapati SV, Kulawiec M, Singh KK, Bigger B, Weissig V. Xenogenic transfer of isolated murine mitochondria into human rho0 cells can improve respiratory function. Rejuvenation Res. 2007;10:561–570. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber-Lotfi F, Ibrahim N, Boesch P, Cosset A, Konstantinov Y, Lightowlers RN, Dietrich A. Developing a genetic approach to investigate the mechanism of mitochondrial competence for DNA import. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada Y, Harashima H. Mitochondrial drug delivery systems for macromolecule and their therapeutic application to mitochondrial diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1439–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon YG, Yang YW, Koob MD. PCR-based cloning of the complete mouse mitochondrial genome and stable engineering in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:1671–1676. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schatz G, Butow RA. How are proteins imported into mitochondria? Cell. 1983;32:316–318. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schatz G. How mitochondria import proteins from the cytoplasm. FEBS Lett. 1979;103:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)81328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurt EC, Pesold-Hurt B, Schatz G. The cleavable prepiece of an imported mitochondrial protein is sufficient to direct cytosolic dihydrofolate reductase into the mitochondrial matrix. FEBS Lett. 1984;178:306–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurt EC, Pesold-Hurt B, Schatz G. The amino-terminal region of an imported mitochondrial precursor polypeptide can direct cytoplasmic dihydrofolate reductase into the mitochondrial matrix. Embo J. 1984;3:3149–3156. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chacinska A, Koehler CM, Milenkovic D, Lithgow T, Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138:628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mokranjac D, Neupert W. Thirty years of protein translocation into mitochondria: unexpectedly complex and still puzzling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogtle FN, Wortelkamp S, Zahedi RP, Becker D, Leidhold C, Gevaert K, Kellermann J, Voos W, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Global analysis of the mitochondrial N-proteome identifies a processing peptidase critical for protein stability. Cell. 2009;139:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glick BS, Brandt A, Cunningham K, Muller S, Hallberg RL, Schatz G. Cytochromes c1 and b2 are sorted to the intermembrane space of yeast mitochondria by a stop-transfer mechanism. Cell. 1992;69:809–822. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90292-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gakh O, Cavadini P, Isaya G. Mitochondrial processing peptidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:63–77. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jan PS, Esser K, Pratje E, Michaelis G. Som1, a third component of the yeast mitochondrial inner membrane peptidase complex that contains Imp1 and Imp2. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:483–491. doi: 10.1007/s004380051192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann JM, Kohl R. Catch me if you can! Oxidative protein trapping in the intermembrane space of mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:559–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesecke N, Terziyska N, Kozany C, Baumann F, Neupert W, Hell K, Herrmann JM. A disulfide relay system in the intermembrane space of mitochondria that mediates protein import. Cell. 2005;121:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscioni D, Morizono H, McCarter RJ, Stern A, Cabrera-Luque J, Hoang A, Sanmiguel J, Wu D, Bell P, Gao GP, Raper SE, Wilson JM, Batshaw ML. Long-term correction of ammonia metabolism and prolonged survival in ornithine transcarbamylase-deficient mice following liver-directed treatment with adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;14:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rorbach J, Yusoff AA, Tuppen H, Abg-Kamaludin DP, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, McFarland R, Lightowlers RN. Overexpression of human mitochondrial valyl tRNA synthetase can partially restore levels of cognate mt-tRNAVal carrying the pathogenic C25U mutation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3065–3074. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagley P, Farrell LB, Gearing DP, Nero D, Meltzer S, Devenish RJ. Assembly of functional proton-translocating ATPase complex in yeast mitochondria with cytoplasmically synthesized subunit 8, a polypeptide normally encoded within the organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:2091–2095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredi G, Fu J, Ojaimi J, Sadlock JE, Kwong JQ, Guy J, Schon EA. Rescue of a deficiency in ATP synthesis by transfer of MTATP6, a mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene, to the nucleus. Nat Genet. 2002;30:394–399. doi: 10.1038/ng851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guy J, Qi X, Pallotti F, Schon EA, Manfredi G, Carelli V, Martinuzzi A, Hauswirth WW, Lewin AS. Rescue of a mitochondrial deficiency causing Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:534–542. doi: 10.1002/ana.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zullo SJ, Parks WT, Chloupkova M, Wei B, Weiner H, Fenton WA, Eisenstadt JM, Merril CR. Stable transformation of CHO Cells and human NARP cybrids confers oligomycin resistance (oli(r)) following transfer of a mitochondrial DNA-encoded oli(r) ATPase6 gene to the nuclear genome: a model system for mtDNA gene therapy. Rejuvenation Res. 2005;8:18–28. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bokori-Brown M, Holt IJ. Expression of algal nuclear ATP synthase subunit 6 in human cells results in protein targeting to mitochondria but no assembly into ATP synthase. Rejuvenation Res. 2006;9:455–469. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaltimbacher V, Bonnet C, Lecoeuvre G, Forster V, Sahel JA, Corral-Debrinski M. mRNA localization to the mitochondrial surface allows the efficient translocation inside the organelle of a nuclear recoded ATP6 protein. Rna. 2006;12:1408–1417. doi: 10.1261/rna.18206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonnet C, Kaltimbacher V, Ellouze S, Augustin S, Benit P, Forster V, Rustin P, Sahel JA, Corral-Debrinski M. Allotopic mRNA localization to the mitochondrial surface rescues respiratory chain defects in fibroblasts harboring mitochondrial DNA mutations affecting complex I or v subunits. Rejuvenation Res. 2007;10:127–144. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonnet C, Augustin S, Ellouze S, Benit P, Bouaita A, Rustin P, Sahel JA, Corral-Debrinski M. The optimized allotopic expression of ND1 or ND4 genes restores respiratory chain complex I activity in fibroblasts harboring mutations in these genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1707–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellouze S, Augustin S, Bouaita A, Bonnet C, Simonutti M, Forster V, Picaud S, Sahel JA, Corral-Debrinski M. Optimized allotopic expression of the human mitochondrial ND4 prevents blindness in a rat model of mitochondrial dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ojaimi J, Pan J, Santra S, Snell WJ, Schon EA. An algal nucleus-encoded subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase rescues a defect in the analogous human mitochondrial-encoded subunit. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3836–3844. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo BB, Kitajima-Ihara T, Chan EK, Scheffler IE, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Molecular remedy of complex I defects: rotenone-insensitive internal NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria restores the NADH oxidase activity of complex I-deficient mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9167–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai Y, Hajek P, Chomyn A, Chan E, Seo BB, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T, Attardi G. Lack of complex I activity in human cells carrying a mutation in MtDNA-encoded ND4 subunit is corrected by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NDI1) gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38808–38813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai Y, Park JS, Deng JH, Li Y, Hu P. Restoration of mitochondrial function in cells with complex I deficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1042:25–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo BB, Wang J, Flotte TR, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. Use of the NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NDI1) gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a possible cure for complex I defects in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37774–37778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Flotte TR, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. In vivo complementation of complex I by the yeast Ndi1 enzyme. Possible application for treatment of Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14250–14255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marella M, Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Greenamyre JT, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Protection by the NDI1 gene against neurodegeneration in a rotenone rat model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barber-Singh J, Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Lau YS, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Neuroprotective effect of long-term NDI1 gene expression in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson disorder. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:259–267. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siedow JN, Umbach AL. The mitochondrial cyanide-resistant oxidase: structural conservation amid regulatory diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:432–439. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakkaart GA, Dassa EP, Jacobs HT, Rustin P. Allotopic expression of a mitochondrial alternative oxidase confers cyanide resistance to human cell respiration. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:341–345. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dassa EP, Dufour E, Goncalves S, Jacobs HT, Rustin P. The alternative oxidase, a tool for compensating cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in human cells. Physiol Plant. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rustin P, Jacobs HT. Respiratory chain alternative enzymes as tools to better understand and counteract respiratory chain deficiencies in human cells and animals. Physiol Plant. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alfonzo JD, Soll D. Mitochondrial tRNA import--the challenge to understand has just begun. Biol Chem. 2009;390:717–722. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharyya SN, Adhya S. The complexity of mitochondrial tRNA import. RNA Biol. 2004;1:84–88. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubio MA, Rinehart JJ, Krett B, Duvezin-Caubet S, Reichert AS, Soll D, Alfonzo JD. Mammalian mitochondria have the innate ability to import tRNAs by a mechanism distinct from protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9186–9191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804283105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolesnikova OA, Entelis NS, Jacquin-Becker C, Goltzene F, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Lightowlers RN, Martin RP, Tarassov I. Nuclear DNA-encoded tRNAs targeted into mitochondria can rescue a mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with the MERRF syndrome in cultured human cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2519–2534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahata B, Mukherjee S, Mishra S, Bandyopadhyay A, Adhya S. Functional delivery of a cytosolic tRNA into mutant mitochondria of human cells. Science. 2006;314:471–474. doi: 10.1126/science.1129754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srivastava S, Moraes CT. Manipulating mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy by a mitochondrially targeted restriction endonuclease. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:3093–3099. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.26.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanaka M, Borgeld HJ, Zhang J, Muramatsu S, Gong JS, Yoneda M, Maruyama W, Naoi M, Ibi T, Sahashi K, Shamoto M, Fuku N, Kurata M, Yamada Y, Nishizawa K, Akao Y, Ohishi N, Miyabayashi S, Umemoto H, Muramatsu T, Furukawa K, Kikuchi A, Nakano I, Ozawa K, Yagi K. Gene therapy for mitochondrial disease by delivering restriction endonuclease SmaI into mitochondria. J Biomed Sci. 2002;9:534–541. doi: 10.1159/000064726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexeyev MF, Venediktova N, Pastukh V, Shokolenko I, Bonilla G, Wilson GL. Selective elimination of mutant mitochondrial genomes as therapeutic strategy for the treatment of NARP and MILS syndromes. Gene Ther. 2008;15:516–523. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minczuk M, Papworth MA, Miller JC, Murphy MP, Klug A. Development of a single-chain, quasi-dimeric zinc-finger nuclease for the selective degradation of mutated human mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papworth M, Kolasinska P, Minczuk M. Designer zinc-finger proteins and their applications. Gene. 2006;366:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shokolenko IN, Alexeyev MF, Robertson FM, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. The expression of Exonuclease III from E. coli in mitochondria of breast cancer cells diminishes mitochondrial DNA repair capacity and cell survival after oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:471–482. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fishel ML, Seo YR, Smith ML, Kelley MR. Imbalancing the DNA base excision repair pathway in the mitochondria; targeting and overexpressing N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase in mitochondria leads to enhanced cell killing. Cancer Res. 2003;63:608–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rinne ML, He Y, Pachkowski BF, Nakamura J, Kelley MR. N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase overexpression increases alkylation sensitivity by rapidly removing non-toxic 7-methylguanine adducts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2859–2867. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown WM, George M, Jr, Wilson AC. Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:1967–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khrapko K, Coller HA, Andre PC, Li XC, Hanekamp JS, Thilly WG. Mitochondrial mutational spectra in human cells and tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13798–13803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dobson AW, Kelley MR, Wilson GL, LeDoux SP. Targeting DNA Repair Proteins to Mitochondria. In: Copeland WC, editor. Mitochondrial DNA: Methods and protocols. Vol. 197. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2002. pp. 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rachek LI, Grishko VI, Musiyenko SI, Kelley MR, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Conditional targeting of the DNA repair enzyme hOGG1 into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44932–44937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dobson AW, Grishko V, LeDoux SP, Kelley MR, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN. Enhanced mtDNA repair capacity protects pulmonary artery endothelial cells from oxidant-mediated death. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L205–210. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00443.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Druzhyna NM, Hollensworth SB, Kelley MR, Wilson GL, Ledoux SP. Targeting human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase to mitochondria of oligodendrocytes protects against menadione-induced oxidative stress. Glia. 2003;42:370–378. doi: 10.1002/glia.10230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Druzhyna NM, Musiyenko SI, Wilson GL, LeDoux SP. Cytokines induce nitric oxide-mediated mtDNA damage and apoptosis in oligodendrocytes. Protective role of targeting 8-oxoguanine glycosylase to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21673–21679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ho R, Rachek LI, Xu Y, Kelley MR, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Yeast apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease Apn1 protects mammalian neuronal cell line from oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2007;102:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rachek LI, Grishko VI, Alexeyev MF, Pastukh VV, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Endonuclease III and endonuclease VIII conditionally targeted into mitochondria enhance mitochondrial DNA repair and cell survival following oxidative stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3240–3247. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cai S, Xu Y, Cooper RJ, Ferkowicz MJ, Hartwell JR, Pollok KE, Kelley MR. Mitochondrial targeting of human O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase protects against cell killing by chemotherapeutic alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3319–3327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rasmussen AK, Rasmussen LJ. Targeting of O6-MeG DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) to mitochondria protects against alkylation induced cell death. Mitochondrion. 2005;5:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Steeg H, Oudshoorn P, Van Hell B, Polman JE, Grivell LA. Targeting efficiency of a mitochondrial pre-sequence is dependent on the passenger protein. Embo J. 1986;5:3643–3650. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pastukh V, Shokolenko IN, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF. Mutations in the passenger polypeptide can affect its partitioning between mitochondria and cytoplasm : Mutations can impair the mitochondrial import of DsRed. Mol Biol Rep. 2008;35:215–223. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sato T, Esaki M, Fernandez JM, Endo T. Comparison of the protein-unfolding pathways between mitochondrial protein import and atomic-force microscopy measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17999–18004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504495102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilcox AJ, Choy J, Bustamante C, Matouschek A. Effect of protein structure on mitochondrial import. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15435–15440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507324102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Waltner M, Hammen PK, Weiner H. Influence of the mature portion of a precursor protein on the mitochondrial signal sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21226–21230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Janiak F, Glover JR, Leber B, Rachubinski RA, Andrews DW. Targeting of passenger protein domains to multiple intracellular membranes. Biochem J. 1994;300 ( Pt 1):191–199. doi: 10.1042/bj3000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Regev-Rudzki N, Karniely S, Ben-Haim NN, Pines O. Yeast aconitase in two locations and two metabolic pathways: seeing small amounts is believing. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4163–4171. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh B, Gupta RS. Mitochondrial import of human and yeast fumarase in live mammalian cells: retrograde translocation of the yeast enzyme is mainly caused by its poor targeting sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakai Y, Nakai M, Hayashi H, Kagamiyama H. Nuclear localization of yeast Nfs1p is required for cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8314–8320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pastukh V, Shokolenko I, Wang B, Wilson G, Alexeyev M. Human mitochondrial transcription factor A possesses multiple subcellular targeting signals. FEBS J. 2007;274:6488–6499. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hashiguchi K, Stuart JA, de Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA. The C-terminal alphaO helix of human Ogg1 is essential for 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase activity: the mitochondrial beta-Ogg1 lacks this domain and does not have glycosylase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5596–5608. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bae TJ, Kim MS, Kim JW, Kim BW, Choo HJ, Lee JW, Kim KB, Lee CS, Kim JH, Chang SY, Kang CY, Lee SW, Ko YG. Lipid raft proteome reveals ATP synthase complex in the cell surface. Proteomics. 2004;4:3536–3548. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim KB, Lee JW, Lee CS, Kim BW, Choo HJ, Jung SY, Chi SG, Yoon YS, Yoon G, Ko YG. Oxidation-reduction respiratory chains and ATP synthase complex are localized in detergent-resistant lipid rafts. Proteomics. 2006;6:2444–2453. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinez LO, Jacquet S, Esteve JP, Rolland C, Cabezon E, Champagne E, Pineau T, Georgeaud V, Walker JE, Terce F, Collet X, Perret B, Barbaras R. Ectopic beta-chain of ATP synthase is an apolipoprotein A-I receptor in hepatic HDL endocytosis. Nature. 2003;421:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nature01250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vives-Bauza C, Magrane J, Andreu AL, Manfredi G. Novel Role of ATPase Subunit C Targeting Peptides Beyond Mitochondrial Protein Import. Mol Biol Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction technology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Modulation of Cellular Function by TAT Mediated Transduction of Full Length Proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:97–104. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chauhan A, Tikoo A, Kapur AK, Singh M. The taming of the cell penetrating domain of the HIV Tat: myths and realities. J Control Release. 2007;117:148–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heitz F, Morris MC, Divita G. Twenty years of cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wagstaff KM, Jans DA. Protein transduction: cell penetrating peptides and their therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1371–1387. doi: 10.2174/092986706776872871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Asoh S, Ohsawa I, Mori T, Katsura K, Hiraide T, Katayama Y, Kimura M, Ozaki D, Yamagata K, Ohta S. Protection against ischemic brain injury by protein therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17107–17112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262460299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katsura K, Takahashi K, Asoh S, Watanabe M, Sakurazawa M, Ohsawa I, Mori T, Igarashi H, Ohkubo S, Katayama Y, Ohta S. Combination therapy with transductive anti-death FNK protein and FK506 ameliorates brain damage with focal transient ischemia in rat. J Neurochem. 2008;106:258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3042.2008.05360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arakawa M, Yasutake M, Miyamoto M, Takano T, Asoh S, Ohta S. Transduction of anti-cell death protein FNK protects isolated rat hearts from myocardial infarction induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Life Sci. 2007;80:2076–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagai S, Asoh S, Kobayashi Y, Shidara Y, Mori T, Suzuki M, Moriyama Y, Ohta S. Protection of hepatic cells from apoptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion injury by protein therapeutics. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen H, Zhang L, Jin Z, Jin E, Fujiwara M, Ghazizadeh M, Asoh S, Ohta S, Kawanami O. Anti-apoptotic PTD-FNK protein suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ohta Y, Kamiya T, Nagai M, Nagata T, Morimoto N, Miyazaki K, Murakami T, Kurata T, Takehisa Y, Ikeda Y, Asoh S, Ohta S, Abe K. Therapeutic benefits of intrathecal protein therapy in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:3028–3037. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Del Gaizo V, MacKenzie JA, Payne RM. Targeting proteins to mitochondria using TAT. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Del Gaizo V, Payne RM. A novel TAT-mitochondrial signal sequence fusion protein is processed, stays in mitochondria, and crosses the placenta. Mol Ther. 2003;7:720–730. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shokolenko IN, Alexeyev MF, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. TAT-mediated protein transduction and targeted delivery of fusion proteins into mitochondria of breast cancer cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rapoport M, Saada A, Elpeleg O, Lorberboum-Galski H. TAT-mediated delivery of LAD restores pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in the mitochondria of patients with LAD deficiency. Mol Ther. 2008;16:691–697. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Iyer S, Thomas RR, Portell FR, Dunham LD, Quigley CK, Bennett JP., Jr Recombinant mitochondrial transcription factor A with N-terminal mitochondrial transduction domain increases respiration mitochondrial gene expression. Mitochondrion. 2009;9:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]