Abstract

Recent years have seen remarkable progress in applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to proteins that have traditionally been difficult to study due to issues with folding, posttranslational modification, and expression levels or combinations thereof. In particular, insect cells have proved useful in allowing large quantities of isotope-labeled, functional proteins to be obtained and purified to homogeneity, allowing study of their structures and dynamics by using NMR. Here, we provide protocols that have proven successful in such endeavors.

Keywords: Isotope labeling, Baculovirus, Nuclear magnetic resonance, Recombinant protein expression, Insect cells

1. Introduction: Baculovirus-Insect Cell Expression System

Isotope labeling of proteins represents an important and often required tool for the application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to investigate the structure and dynamics of proteins. So far, the great majority of isotope-labeled proteins have been expressed in Escherichia coli (1) because of the ease of cloning and expressing proteins at low cost. When possible, protein production should be performed in a prokaryotic system (i.e., E. coli), since this strategy is the most cost-effective and allows the most flexibility. However, human or complex proteins often cannot be expressed in E. coli in an active, correctly folded, posttranslationally modified form (glycosylated, phosphorylated, etc.). The capacity of E. coli for protein folding and forming disulfide bonds is not sufficient for many recombinant proteins, although there are a number of new developments to overcome these limitations:

Coexpressing molecular chaperones (4)

Fusing highly soluble tags (gst, mbp, trxa, nusa, sumo, etc.) to the target proteins (5)

Overexpressing (6, 7) the target protein or using an engineered E. coli strain capable of forming disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm (e.g., Shuffle, neb)

Refolding in vitro

However, low-expression yield and solubility problems of the target protein in E. coli often force the change from a bacterial recombinant protein expression system to a eukaryotic host.

Numerous eukaryotic-based expression systems are currently available in protein expression laboratories. For NMR use, only three expression hosts are generally considered: yeast (Pichia pastoris (8), Hansenula polymorpha or Kluyveromyces lactis), baculovirus-mediated insect cells, and mammalian cells. More recently, the generation of baculoviruses harboring mammalian promoters (BacMams) have extended the use of baculovirus-mediated expression systems (BvE) to the development of gene delivery (9) and expression vectors in mammalian cells (10). BacMams cannot replicate in mammalian cells, which renders them a much safer alternative to conventional virus vectors (11).

Yeast offers a powerful, simple system for expressing recombinant proteins. Besides the capability of performing posttranslational modification to the recombinant protein, the main advantage of these expression hosts is the feasibility of isotope labeling in simple minimal-defined media. Therefore, the costs of 15N, 13C, or 2H uniform isotope incorporation are negligible in comparison to the costs of other eukaryotic cell media. Higher eukaryotes need well-defined expression media supplemented with expensive, labeled amino acids. But there are also disadvantages to recombinant protein expression in yeast. Since they provide N- and O-linked high-mannose-type glycans that could be immunogenic in humans (12, 13), the production of glycosylated proteins in yeast is not optimal, especially if glycosylation is required for the biological functionality of the target protein. Additionally, yeast cannot perform tyrosine O-sulfation (14), and proteins whose native forms are nonglycosylated may be hyperglycosylated when expressed in yeast (15). A recent study reported the successful reengineering of the glycosylation pathways in P. pastoris to allow the expression of recombinant proteins with human-type glycans (16). This may allow future improvements in the expression of glycosylated proteins in yeast. However, glycosylation is not the only challenge for successful expression of proteins in yeast. Certain proteins are expressed at low levels even when glycosylation is not necessarily an issue (17–19). While the reasons are not fully clear, low-expression yields have been attributed to defects in the ER folding machinery (20–22). Even for proteins in which high-expression yields can be obtained, much of the protein may be misfolded (23). In order to detect which part of the folding machinery may be responsible, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), an enzyme that catalyzes disulfide exchange in the ER, was overexpressed and found to enhance protein yields (24, 25). On the other hand, human adenosine A2A receptor levels were not found to increase with an increase in PDI expression (26). Thus, the process of disulfide bond formation in yeast remains uncertain. Finally, the case is most uncertain for membrane proteins, where there is a lack of knowledge on folding mechanisms and also on the way chaperones and the translocon participate in the folding pathway. Therefore, it is currently recommended to use higher eukaryotic hosts with advanced cell machinery systems for the production of recombinant proteins that have to be glycosylated, disulfide bonded, and/or membrane inserted for functional activity.

Advanced expression systems with higher cell machineries for posttranslational modifications are offered by the baculovirus-mediated expression system in insect cells (BvE) and mammalian expression methods. The BvE is one of the most efficient and popular systems among the eukaryotic hosts to use for expressing recombinant proteins. Therefore, its application is widespread in industrial as well as in academic environments for structural and functional studies of diverse proteins. However, for the production of therapeutic recombinant proteins, mammalian expression systems (mainly Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO) and Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells) are required. Since CHO and HEK293 cells have been extensively characterized and have the ability for human-like glycosylation, the production of recombinant therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and Fc fusion proteins in this host is safe. The rate of production of therapeutic proteins, the largest class of new products being developed by the biopharmaceutical industry, has increased significantly in recent years (27).

Mammalian expression systems have conventionally been considered to be too weak and inefficient for protein expression. However, recent advances have significantly improved the expression levels of these systems. This chapter and the following one, therefore, attempt to provide an overview of some of the recent developments in expression strategies for baculovirus-mediated insect cell and mammalian expression systems in view of NMR investigations. Since NMR requires isotope-labeled protein, the focus of this article is directed toward strategies to incorporate stable isotopes (15N, 13C) into the target protein in insect and mammalian cells (see Chapter 4). A major bottleneck of uniform labeling in higher eukaryotes is the high cost of complex medium with labeled amino acids. Another limitation of these hosts is that they cannot survive in deuterium oxide (D2O)-containing media, so cost-effective generation of perdeuterated proteins is not available, either for insect or for mammalian cell systems.

It is beyond the scope of both chapters to discuss features of the BvE or mammalian expression systems in detail. Comprehensive guides and detailed methodologies for the construction and analysis of recombinant baculovirus for insect cell expression, maintenance of insect cells in culture, and analysis of recombinant protein expression can be found elsewhere (28,29), including in Baculovirus Manuals from Invitrogen, Pharmingen, Novagen, and others). However, given the number of different BvE strategies, we begin this chapter by explaining the principle of BvE and subsequently give a short survey of BvE options.

1.1. Principle of Baculovirus-Mediated Recombinant Protein Expression

The insect cell baculovirus-mediated expression system (BvE) is a powerful platform to rapidly produce high levels of recombinant proteins (see ref. 28 for an excellent review). Unlike bacterial expression hosts, the baculovirus system relies on a eukaryotic expression system and thus offers protein modification, sorting, and transportation machineries similar to those found in higher eukaryotic organisms. Baculoviruses are insect viruses that predominantly infect insect larvae of the order Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) (30). A baculovirus expression vector is a recombinant baculovirus that has been genetically modified to contain a foreign gene of interest, which can be expressed in insect cells under the control of a baculovirus gene promoter. The BvE uses a helper-independent virus that can be propagated to high titers in insect cells adapted for growth in suspension cultures, enabling the production of large amounts of protein with relative ease (31). Finally, baculoviruses are noninfectious to vertebrates and their promoters have been shown to be inactive in mammalian cells (32).

The most commonly used baculovirus for recombinant protein expression is Autographa californica, a multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) (33). AcMNPV is a large (130 kb), lytic, double-stranded DNA virus and can accommodate large segments of foreign DNA for the expression of recombinant protein (34). The BvE is based on the infection of cultured insect cells by a recombinant virus vector in which the target DNA (or multiple genes) is integrated under the control of the strong viral polyhedron promoter (28). The polyhedrin gene (polh) is necessary for the formation of polyhedral or occlusion bodies in the cell nucleus, but is nonessential for viral replication in insect cells. Polyhedra are large particles that appear in the nuclei of AcMNPV-infected insect cells. The first recombinant baculoviruses were generated by replacing the viral polyhedrin gene with a foreign gene of interest through homologous recombination (33). Homologous exchange between the flanking sequences common to both DNA molecules facilitates the insertion of the gene of interest into the viral genome at the polh locus, resulting in the production of a recombinant virus genome and allowing the powerful polyhedron promoter to drive protein expression of the foreign gene. Since the efficiency of homologous recombination is quite low, identification, isolation, and selection of recombinant virus were traditionally achieved by labor-intensive, technically demanding plaque assays. Due to the deletion of the polyhedrin gene, the recombinant plaque has a more clearly distinct morphology than the parental virus containing the polh gene. Subsequently, additional rounds of plaque screening are required to separate the desired recombinant virus from the parental wild-type virus. However, discriminating between polyhedron-positive and -negative plaques and isolating recombinant virus turned out to be a serious problem for many investigators who used the BvE for the production of recombinant proteins. Nowadays, these technical issues and the time-consuming plaque purification processes are eliminated. In the next section, some of the key developments in the BvE are presented and discussed.

1.2. Commercially Available Baculovirus Expression Systems

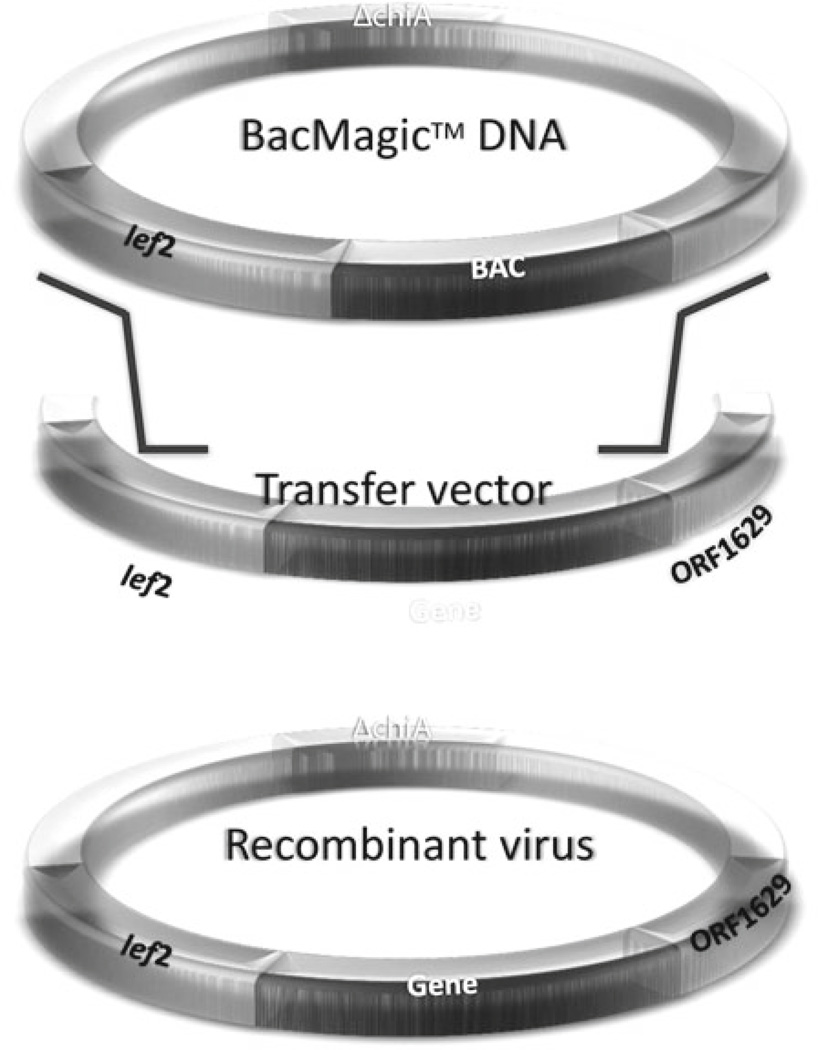

Generally, the baculovirus genome is considered too large to insert a foreign gene directly. In most applications of the BvE, the gene of interest is therefore cloned into a transfer vector, which contains sequences that flank the polyhedron gene in the baculovirus genome. The virus genome and the transfer vector are cotransfected into the insect cells and the gene of interest inserts into the virus genome via homologous recombination (see Fig. 1) under the control of the strong late viral polyhedrin promoter (35). Since a mixture of recombinant and original parental virus is produced after the initial replication, time-consuming plaque purification and isolation are required before protein expression can proceed. BacVector (Merck Biosciences), Baculo-Gold and pBacPAK (BD Biosciences), and Bac-N-Blue (Invitrogen) are commercially available BvEs that use homologous recombination to integrate foreign genes into the virus genome.

Fig. 1.

Construction of baculovirus recombinants with BacMagic system (Novagen). This expression system is based on a modified baculovirus genome containing a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) at the polyhedrin locus and a partial deletion of the essential ORF1629 viral gene. The BacMagic DNA is mixed with a transfer vector, containing a foreign gene at the polh locus and the complete ORF1629, to generate the recombinant virus via homologous recombination in insect cells. Picture taken from the Novagen manual.

New developments in generating recombinant virus by using site-specific transpositions (Bac-to-Bac or BaculoDirect, Invitrogen) or progress in recombination methodology with an engineered baculovirus containing a lethal mutation in an essential gene (open reading frame (ORF1629), flashBAC from Oxford Expression Technologies, or BacMagic from EMD Chemicals, Novagen) have facilitated the use of BvE for a larger user community (28). Generally, these improvement strategies can be classified into transfer plasmid modifications and parental baculovirus genome modification (28). The flashBAC and BacMagic are the most promising BvEs so far, since the efficiency of recombination in both systems is 100%. Therefore, these BvEs overcome the requirement of time-consuming plaque assays and protein expression can be started directly after one or two rounds of virus amplification. This technology reduces the production of recombinant virus to a one-step procedure, fully amenable to high-throughput and automated production systems. Moreover, this approach is compatible with all baculovirus transfer vectors based on homologous recombination in insect cells at the polyhedrin locus, including several multigene coexpression plasmids.

The technology of the flashBAC and BacMagic is driven by a modified bacmid, in which the baculovirus genome AcMNPV with a portion of the essential viral gene (ORF1629) deleted. In addition, a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) replaces the polyhedrin-coding region. This combination prevents nonrecombinant virus from replicating in insect cells, yet allows the viral DNA to be propagated as circular DNA in bacteria. This circular viral DNA is then isolated and purified from bacterial cells (flashBAC or BacMagic DNA provided in the kits). Homologous recombination with a compatible expression plasmid (containing the gene of interest flanked by the lef2 and ORF1629 recombination sites) restores the function of the viral ORF1629 allowing the virus DNA to replicate and replaces the BAC sequence with the target coding sequence under the control of the polyhedrin promoter (Fig. 1). Since only recombinant viruses with a restored ORF1629 can replicate, this results in a unique recombinant virus population. This population can then be used directly to infect a larger insect cell culture (50–200 mL) to produce a high-titer working stock.

1.3. Insect Cell Lines

The main insect cell lines used for cotransfections and baculovirus amplification are Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 or Sf21 (derivatives of the fall armyworm). Trichoplusia ni BTI 5B1-4 (36) (High Five™) cells are generally used for the production of secreted recombinant proteins and not for virus production because of the increased possibility of generating virus mutants (37). Due to the high-mannose and paucimannose types of glycosylation that are obtained in insect cells, no therapeutic protein is currently produced using this system as this would compromise in vivo bioactivity and potentially induce allergenic reactions. Engineering insect cells with glycosyltransferases allows the production of proteins with mammalian-type sugars (38).

1.4. Expression of Labeled Recombinant Protein in the Baculovirus Expression System

Due to the high costs of incorporating stable isotopes into insect cells, it is recommended that the recombinant protein expression is optimized using the chosen BvE before starting with labeled fermentation. There are only a few studies reporting the incorporation of stable isotopes into proteins expressed by baculovirus-mediated insect cell expression (39–47).

In contrast to the initial trials of amino acid-type selective labeling of proteins in user-defined insect cell media, nowadays there are commercial media (BioExpress-2000, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, CIL) available for the different labeling applications. Expression of uniformly 13C- 15N-labeled Abelson Kinase domain (13C–15N BioExpress-2000) was the first example of backbone NMR resonance assignments of a recombinant protein expressed using the BvE (48). So far, most uniform labeling protein work in insect cells is only performed by industrial research groups due to the extraordinary costs of the required media. It is not possible to cultivate insect cells in minimal medium, since this host requires essential amino acids for its growth. Reports of selective amino acid isotope labeling in BvE are more frequently cited in the literature, since this approach is easy and fast and does not require expensive medium for labeling. Even in the absence of a backbone assignment of the target protein, structural information can be deduced from the selective labeling approach based on an existing X-ray structure of the protein. From a practical aspect, it should be considered that there are essential and nonessential amino acids (alanine, cysteine, glutamic acid, glutamine, aspartic acid, and asparagine) in insect cells whose content in the medium depends on the specific provider of the medium. Before starting with site-specific amino acid labeling, the unlabeled quantity of the desired amino acid in the medium should be checked to calculate the required amount of the amino acid to be labeled. In Fig. 2, a schematic presentation of amino acid metabolism is shown for E. coli and insect cells (42). Interestingly, selective labeling of amino acids in insect cells is more effective than in bacteria, since the amino acid pathways in insect cells do not harbor as many aminotransferases as in prokaryotes, which leads to cross-labeling problems.

Fig. 2.

A schematic presentation of amino acid metabolism in E. coli and Sf9 with respect to 15N: The black arrows symbolize pathways present in both expression hosts. Pathways that only exist in E. coli are shown in grey. The strength of the arrows reflects the intensity of the conversion. Picture taken from Bruggert et al. (42).

2. Materials

2.1. Cotransfection of Insect Cells

35-mm2 tissue culture dishes.

Sf9 or Sf21 insect cells.

SF900 II insect cell culture medium (serum-free, antibiotic-free; Invitrogen).

Insect GeneJuice® transfection reagent (Novagen) (see Note 1).

BacMagic DNA: 100 ng (5 µL) per cotransfection (20 ng/µL).

Sterile baculovirus transfer vector DNA containing the gene under investigation (500 ng per cotransfection).

Plastic box to house dishes in the incubator.

Sterile pipettes, bijoux (sterile tubes).

2.2. Amplification of Recombinant Virus

Recombinant virus seed stock (Subheading 3.1).

Sf9 insect cells.

SF900 II insect cell culture medium (Subheading 2.1).

Inverted phase-contrast microscope.

2.3. Analysis of Recombinant Protein Expression

35-mm2 tissue culture dishes.

Sf9 or High Five insect cells.

SF900 II insect cell culture medium (Subheading 2.1).

Recombinant virus stock (Subheading 3.2).

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen): pH 6.2, sterilize by autoclaving.

2.4. Production of Isotopically Labeled Protein

Sf9 insect cells.

SF900 II insect cell culture medium (Subheading 2.1).

BioExpress-2000-U (CIL): Unlabeled insect cell culture medium.

BioExpress-2000-CN (CIL): 15N-, 13 C-labeled insect cell culture medium.

Recombinant virus stock (Subheading 3.2).

Protease inhibitor (Complete™, Roche).

PBS (Subheading 2.3).

3. Methods

For a general overview of the BvEs and cloning, expression, analysis, and purification of recombinant proteins in insect cells, please refer to ref. 29. The following procedures describe the cloning of a recombinant baculovirus expression vector, production (Subheading 3.1) and amplification of recombinant baculovirus (Subheading 3.2), analysis of recombinant protein expression (Subheading 3.3), and finally production of isotope-labeled protein (Subheading 3.4) expressed in insect cells. All of the procedures are based on the flash-BAC or BacMagic systems (no plaque purification required) and must be carried out using sterile technique.

Since the flashBAC system is compatible with all transfer vectors designed for homologous recombination in insect cells at the polh l (BacPAK technology), the target gene can be cloned into many suitable transfer vectors (see Note 2). Moreover, this BvE is compatible with traditional (T4 DNA ligase) and elegant recombinatorial cloning techniques, such as Creator or In-Fusion (BD Biosciences) (see Note 3). While Gateway (Invitrogen) is one of the most popular recombinatorial cloning systems, it is limited to specifically engineered expression vectors with specifically engineered expression vectors with λ recombination sites. These lead to incorporation of additional amino acids into the protein of interest. A new development to avoid multiple cloning of target genes into host-specific expression vectors is triple host transfer vector, pTriEx, from Novagen. Due to the parallel existence of three promoters in this vector series, recombinant protein expression is enabled in vertebrates, insect cells, and bacteria.

3.1. Cotransfection of Insect Cells

For efficient transfection, high-quality DNA of the transfer plasmid is prepared using commercially available plasmid DNA purification kits (Qiagen, Novagen) (see Note 4). Additionally, it is recommended to use fresh, rapidly proliferating cells (see Note 5) for transfection experiments and to have positive and negative transfection controls (see Note 6).

For each cotransfection, prepare one 35-mm2 plate. Seed the dishes with insect cells at least 1 h before use. Use 1 × 106 cells/dish for Sf9 cells and 1.5 × 106 cells/dish for Sf21 cells in 2 mL of SF900 II insect cell culture medium. Allow the cells to attach by incubating at 28°C for 20 min.

- During the 1-h incubation period, prepare a DNA–liposome complex cotransfection mix of BacMagic DNA and Insect GeneJuice® transfection reagent for each transfection. Assemble the following components, in the order listed, in a sterile tube (bijoux) (see Note 7):

- 1 mL serum-free, antibiotic-free SF900 II insect cell culture medium

- 5 µL Insect GeneJuice

- 5 µL BacMagic DNA (100 ng total)

- 5 µL Transfer vector DNA (500 ng total)

- 1.015 mL Total volume

Incubate at room temperature for 15–30 min to allow the DNA–liposome complexes to form.

Remove the culture medium from the 35-mm2 dishes of cells using a sterile pipette, ensuring that the cell monolayer is not disrupted (see Note 8).

Immediately after the medium has been removed from the cells, add the 1 mL of the DNA–liposome complex dropwise to the center of each dish (see Note 9) and incubate in a plastic sandwich box at 28°C for a minimum of 5 h or overnight.

After the incubation period, add another 1 mL of SF900 II insect cell culture medium to each dish and continue the incubation for 5 days in total.

Following the 5-day incubation period (see Note 10), harvest the medium containing the recombinant virus into a sterile bijoux and store in the dark at 4°C. This is the seed stock of recombinant baculovirus (see Note 11). Due to the limited size of the stock, the next step is to amplify the virus recombination sites.

3.2. Amplification of Recombinant Virus

Amplification of the recombinant virus (produced in Subheading 3.1) is necessary before proceeding with recombinant protein expression. The following provides a protocol (adapted from the Novagen and flashBAC Manual) for amplification and preparation of high-titer recombinant virus (passage 1 stock) in cells grown in suspension culture.

Observe the health and viability of cells under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (see Note 12).

Prepare a 100–200 mL culture of Sf9 cells at an appropriate cell density in serum-free SF900 II insect cell culture medium (e.g., 2 × 106 Sf9 cells/mL in log-phase growth; high aeration is recommended (see Note 13)). Cells should be infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of <1 pfu/cell.

Add 0.5 mL of recombinant virus seed stock to the cell culture. Incubate with shaking until the cells are well-infected (usually, 4–5 days) (see Note 14).

When the cells appear to be well-infected with virus, harvest the cell culture medium by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Remove the supernatant aseptically. Store the supernatant (recombinant virus stock) in the dark at 4°C (see Note 15).

3.3. Analysis of Recombinant Protein Expression

Before proceeding with use of the virus in subsequent protein expression experiments, a plaque assay to determine the accurate titer is strongly recommended by the manufacturer of the fl ash-BAC and BacMagic technology (see Note 16). This allows the calculation of MOI and ensures cross-referencing and reproducibility in the following experiments. However, for analysis of protein expression, it is not absolutely required to know the titer of the recombinant virus (see Note 17). Pilot expression analysis can also be performed by infecting cells with different amounts of P1 virus and monitoring the expression of the recombinant protein. According to the protein expression literature, it is recommended that exponentially growing cells should be infected at a high MOI to ensure that all cells are infected simultaneously and that the culture is synchronous. However, in our lab, various P1 viruses are directly added (0.5–10%) to the insect cells for determining the best ratio for optimal recombinant protein expression without knowing the exact titer of the different viruses. The best time to harvest the recombinant protein can be examined by taking samples at different time points after infection (see Note 18). It is recommended to also prepare noninfected or mock-infected cells as a control for host cell proteins and a positive control of a successfully tested recombinant virus. Recombinant protein expression can then be evaluated by SDS-PAGE or Western blot analysis. Additionally, protein expression should be compared between Sf9 and High Five cell lines, especially if the protein of interest is secreted (see Note 19). The following protocol is adapted from the Novagen and flashBAC Manual.

Seed 35-mm2 dishes (one per virus to be tested plus a positive and negative control) with 1 × 106 of S9 or High Five cells per dish and allow the cells to attach by incubating at 28°C for 1 h.

Remove the medium, add 200 µL of the recombinant virus stock to be tested, and incubate at room temperature for an additional hour.

Remove the virus inoculum, add 1.5 mL of SF900 II insect cell culture medium, and incubate at 28°C for 48 h.

Use a sterile pipette tip to scrape the cells from the dishes into suspension and to transfer them into sterile Eppendorf tubes.

Centrifuge the cells at 1,500 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Remove the supernatant and discard (see Note 20).

Resuspend the pellet (protein of interest in the cytosol) in 80 µL of PBS.

Analyze the extent of protein overexpression by using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting if a suitable antibody is available for the recombinant protein (see Note 21 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Protein overexpression and purification using insect cells. SDS PAGE (left), Western Blot (right): Protein samples loaded are BC (before Ni-NTA chromatography), FT (Flowthrough), M (Molecular weight marker), W (Wash), E (Elution).

3.4. Production of Isotopically Labeled Protein

While fermenters and bioreactors are now routinely used to produce recombinant proteins in insect cells, good yields can be achieved in shake cultures at a fraction of the cost. Large, disposable shake fl asks can be obtained that hold up to 1.5 L insect cell culture on a shaking platform in a warm room or incubator. The most suitable culture protocol for isotope labeling of a recombinant protein in insect cells involves an initial growth phase for the insect cells in an unlabeled growth/expression medium and a subsequent expression phase, where cells are centrifuged and resuspended into the labeling medium prior to infection with the recombinant baculovirus (see Note 22). This centrifugation step allows much higher expression levels of the labeled protein compared to one with growth and expression in labeling medium without the change in medium. Recently, isotope-labeled expression media for insect cells have become commercially available (BioExpress-2000, CIL), but the source and the concentration of the amino acids in these media are not published. However, for site-specific labeling of amino acids in proteins expressed in insect cells, adding the isotope-labeled amino acid of interest to a standard insect cell medium before infection (see Note 23) also works well and the cost for this labeling strategy is comparable to that when using E. coli.

The following protocol is adapteEfficient uniform isotope labeling of proteins expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells using BioExpress® 2000 (Insect cell) medium by André Strauss, Gabriele Fendrich, and Wolfgang Jahnke.

Prior to performing isotope labeling of a protein, optimize the culture and BV-infection conditions in unlabeled medium (e.g., BioExpress 2000-U or SF900 II for expression of the protein).

Cultivate several 100 mL cultures of Sf9 cells, adapted to growth in serum-free SF900 II medium, in 500-mL Erlenmeyer fl asks for 3 days at 27°C with shaking at 90 rpm.

Prepare the uniform isotope-labeling medium (see Note 24).

When the final cell density of the culture has reached 1.5 × 106 cells/mL (~3 days), sterile centrifuge the cells at 400 × g for 20 min at 20°C.

Resuspend the pelleted cells in 100-mL portions in labeled BioExpress® 2000-CN medium and transfer them to fresh 500-mL Erlenmeyer flasks.

Add the recombinant virus stock at a titer of 0.5–2 × 108 pfu/mL to an MOI = 1–2, according to optimized conditions.

Grow the 100 mL cultures of baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells for 3 days post infection in labeled BioExpress® 2000-CN medium at 27°C, with shaking at 90 rpm (see Note 25).

Harvest the cells expressing the labeled recombinant protein by centrifuging at 400 × g for 20 min at 20°C (see Note 26); resuspend the pelleted cells in 20 mL of PBS containing protease inhibitor mix (see Note 27), followed by a second centrifugation in 50-mL plastic tubes at 400 × g for 20 min at 20°C. Store the pelleted cells at −80°C.

Isolate and purify the recombinant protein according to protocols generated for the unlabeled protein.

Footnotes

Lipofectin® (Invitrogen), FuGENE 6 (Roche), Tfx-20™ (Promega), and CELLFECTIN® (Invitrogen) have also been successfully tested.

Several suitable vectors from different providers are available and are summarized: http://www.expressiontechnologies.com/flashBAC/vectors.asp.

Ligation protocols are described in the manuals of the specific cloning technology providers.

Plasmid DNA purification protocols are provided by the manufacturers of the purification kits. The DNA must be sterile and must be of a quality suitable for transfection into cells.

Healthy cells look bright, round, and refractile, and many should be in the process of dividing into daughter cells.

A control transfer vector is supplied with the BacMagic kit and can be used to make recombinant virus; the lacZ-positive infected cells can be stained using X-gal. Add 1 mL of appropriate insect cell culture medium containing 15 µL of 2% (w/v) X-gal in N, N-dimethylformamide and incubate at 28°C. After 5 h, the cells and culture medium appear blue in color, confirming the production of recombinant virus.

Plasticware used to prepare the transfection mixture has to be made from polystyrene and not from polypropylene, since the complexes bind to polypropylene.

When removing liquid from a dish of cells, tip the dish at a 30–60° angle so that the liquid pools toward one side of the dish. It is important not to allow the cell monolayer to dry out at this point.

Adding the mixture dropwise should not disturb the cell monolayer if it is done slowly and gently.

Cell monolayers in which recombinant virus has been produced appear very different from mock-transfected control cells under the inverted microscope. Control cells form a confluent monolayer while virus-infected cells do not form a confluent monolayer and appear grainy with enlarged nuclei.

The expected titer of this initial viral seed stock is generally about 1 × 107 pfu/mL. In contrast to virus-free cells, virus-infected cells appear grainy with enlarged nuclei and do not form a confluent monolayer.

It is important that the cells are healthy and in the log phase of growth to ensure that virus replication occurs efficiently to generate high-titer stocks of virus for subsequent use in expression studies suitable for transfection into cells.

Virus-infected cells have an increased need for oxygen, and therefore the contents of the flasks should be shaken at quite high speeds to maximize aeration. The surface area-to-volume ratio should also be as large as possible for maximum gas exchange. Do not overfill the flasks.

Under a phase-contrast inverted microscope, cells infected with virus appear grainy when compared to healthy cells. The infected cells become uniformly rounded and enlarged, with distinct enlarged nuclei.

The virus stock can be stored in the dark at 4°C for 6–12 months, although the titer begins to drop after 3–4 months. Titer the virus before use and reamplify if necessary. The addition of 2–5% serum when using serum-free medium can be helpful in avoiding a drop in titer. Virus may be frozen at −80°C for longer periods of time. Avoid multiple freeze–thaw cycles.

Protocols for plaque assays can be found in the manuals of Novagen and Oxford Expression Technologies.

After cotransfecting and harvesting the seed stock of virus for further amplification, it is possible to harvest the remaining cells from the dish and prepare these for SDS-PAGE/Western blotting. This gives a quick check for gene expression.

The most commonly used times are at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post infection (hpi). Some proteins may be very stable and accumulate to high levels by 96 hpi, and others may start to degrade and thus need to be harvested much earlier.

High Five cell lines (Invitrogen) often increase the yield of secreted recombinant proteins.

For secreted protein expression, the supernatant has to be analyzed.

Standard molecular biology procedures like SDS-PAGE and Western-blotting are precisely described in Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual) (49).

A similar cost-reducing labeling strategy in E. coli was also described for the production of isotope-labeled protein by Marley and coworkers (50).

300–600 mg of 15N-Phe or 15N-Leu (per liter culture medium) was immediately added to the insect cells after being infected with virus. The medium used for the amino acid-selective labeling was 1LSF-900 II serum-free medium from Invitrogen.

Medium can be stored, and filter-sterilized for several months at 4°C in the dark without loss of capacity for protein expression. Warm to 28°C before using.

The harvesting time of the infected cells depends on the stability of the target protein.

For secreted protein expression, the supernatant has to be further purified.

Protease inhibitor mix: Roche complete (one tablet dissolved in 200 mL PBS)

Contributor Information

Krishna Saxena, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Arpana Dutta, Department of Structural Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Judith Klein-Seetharaman, Department of Structural Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Harald Schwalbe, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, schwalbe@nmr.uni-frankfurt.de.

References

- 1.Goto NK, Kay LE. New developments in isotope labeling strategies for protein solution NMR spectroscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:585–592. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schein CH. Optimizing protein folding to the native state in bacteria. Curr Opin. Biotechnol. 1991;2:746–750. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(91)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qing G, Ma LC, Khorchid A, Swapna GV, Mal TK, Takayama MM, Xia B, Phadtare S, Ke H, Acton T, Montelione GT, Ikura M, Inouye M. Cold-shock induced high-yield protein production in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:877–882. doi: 10.1038/nbt984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young JC, Agashe VR, Siegers K, Hartl FU. Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito D, Chatterjee DK. Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006;17:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen CL, Matthey-Dupraz A, Missiakas D, Raina S. A new Escherichia coli gene, dsbG, encodes a periplasmic protein involved in disulphide bond formation, required for recycling DsbA/DsbB and DsbC redox proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;26:121–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5581925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardwell JC. Building bridges: disulphide bond formation in the cell. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickford AR, O’Leary JM. Isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins from the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;278:17–33. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu YC. Baculoviral vectors for gene delivery: a review. Curr. Gene Ther. 2008;8:54–65. doi: 10.2174/156652308783688509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kost TA, Condreay JP, Ames RS, Rees S, Romanos MA. Implementation of BacMam virus gene delivery technology in a drug discovery setting. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitchman RB, Possee RD, King LA. Baculovirus expression systems for recombinant protein production in insect cells. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2009;3:46–54. doi: 10.2174/187220809787172669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam JS, Huang H, Levitz SM. Effect of differential N-linked and O-linked mannosylation on recognition of fungal antigens by dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasgupta S, Navarrete AM, Bayry J, Delignat S, Wootla B, Andre S, Christophe O, Nascimbeni M, Jacquemin M, Martinez- Pomares L, Geijtenbeek TB, Moris A, Saint-Remy JM, Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV, Lacroix-Desmazes S. A role for exposed mannosylations in presentation of human therapeutic self-proteins to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:8965–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702120104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore KL. The biology and enzymology of protein tyrosine O-sulfation. The J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24243–24246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daly R, Hearn MT. Expression of heterologous proteins in Pichia pastoris a useful experimental tool in protein engineering and production. J. Mol. Recognit. 2005;18:119–138. doi: 10.1002/jmr.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton SR, Gerngross TU. Glycosylation engineering in yeast: the advent of fully humanized yeast. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chisholm V, Chen CY, Simpson NJ, Hitzeman RA. Molecular and genetic approach to enhancing protein secretion. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:471–482. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85039-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorner AJ, Kaufman RJ. Analysis of synthesis, processing, and secretion of proteins expressed in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:577–596. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85046-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moir DT. Yeast mutants with increased secretion efficiency. Biotechnology. 1989;13:215–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biemans R, Thines D, Rutgers T, De Wilde M, Cabezon T. The large surface protein of hepatitis B virus is retained in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum and provokes its unique enlargement. DNA Cell. Biol. 1991;10:191–200. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gennaro DE, Hoffstein ST, Marks G, Ramos L, Oka MS, Reff ME, Hart TK, Bugelski PJ. Quantitative immunocytochemical staining for recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1991;198:591–598. doi: 10.3181/00379727-198-43294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuster JR. Gene expression in yeast: protein secretion. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1991;2:685–690. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(91)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mollaaghababa R, Davidson FF, Kaiser C, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: expression of functional mammalian opsin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:11482–11486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson AS, Hines V, Wittrup KD. Protein disulfide isomerase overexpression increases secretion of foreign proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnology (N Y) 1994;12:381–384. doi: 10.1038/nbt0494-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shusta EV, Raines RT, Pluckthun A, Wittrup KD. Increasing the secretory capacity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of single-chain antibody fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butz JA, Niebauer RT, Robinson AS. Co-expression of molecular chaperones does not improve the heterologous expression of mammalian G-protein coupled receptor expression in yeast. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003;84:292–304. doi: 10.1002/bit.10771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durocher Y, Butler M. Expression systems for therapeutic glycoprotein production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarvis DL. Baculovirus-insect cell expression systems. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:191–222. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O´Reilly DR, Miller L, Luckow VA. Baculovirus Expression Vectors - a Laboratory Manual. New York: WH Freeman; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Regenmortel MH, Mayo MA, Fauquet CM, Maniloff J. Virus nomenclature: consensus versus chaos. Arch. Virol. 2000;145:2227–2232. doi: 10.1007/s007050070053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt I. From gene to protein: a review of new and enabling technologies for multi-parallel protein expression. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;40:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carbonell LF, Klowden MJ, Miller LK. Baculovirus-mediated expression of bacterial genes in dipteran and mammalian cells. J. Virol. 1985;56:153–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.1.153-160.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith GE, Summers MD, Fraser MJ. Production of human beta interferon in insect cells infected with a baculovirus expression vector. Molecular Cell. Biol. 1983;3:2156–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayres MD, Howard SC, Kuzio J, Lopez- Ferber M, Possee RD. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:586–605. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitts PA, Possee RD. A method for producing recombinant baculovirus expression vectors at high frequency. Biotechniques. 1993;14:810–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kost TA, Condreay JP, Jarvis DL. Baculovirus as versatile vectors for protein expression in insect and mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:567–575. doi: 10.1038/nbt1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friesen PD, Nissen MS. Gene organization and transcription of TED a lepidopteran retrotransposon integrated within the baculovirus genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:3067–3077. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison RL, Jarvis DL. Protein N-glycosylation in the baculovirusinsect cell expression system and engineering of insect cells to produce “mammalianized” recombinant glycoproteins. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;68:159–191. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)68005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeLange F, Klaassen CH, Wallace-Williams SE, Bovee-Geurts PH, Liu XM, DeGrip WJ, Rothschild KJ. Tyrosine structural changes detected during the photo-activation of rhodopsin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23735–23739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creemers AF, Klaassen CH, Bovee-Geurts PH, Kelle R, Kragl U, Raap J, de Grip WJ, Lugtenburg J, de Groot HJ. Solid state 15N NMR evidence for a complex Schiff base counterion in the visual G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7195–7199. doi: 10.1021/bi9830157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellizzi JJ, Widom J, Kemp CW, Clardy J. Producing selenomethionine-labeled proteins with a baculovirus expression vector system. Structure. 1999;7:R263–R267. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruggert M, Rehm T, Shanker S, Georgescu J, Holak TA. A novel medium for expression of proteins selectively labeled with 15 N-amino acids in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;25:335–348. doi: 10.1023/a:1023062906448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss A, Bitsch F, Cutting B, Fendrich G, Graff P, Liebetanz J, Zurini M, Jahnke W. Amino-acid-type selective isotope labeling of proteins expressed in Baculovirus-infected insect cells useful for NMR studies. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;26:367–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1024013111478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauss A, Bitsch F, Fendrich G, Graff P, Knecht R, Meyhack B, Jahnke W. Efficient uniform isotope labeling of Abl kinase expressed in Baculovirus-infected insect cells. J. Biomol. NMR. 2005;31:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-2451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Betz M, Vogtherr M, Schieborr U, Elshorst B, Grimme S, Pescatore B, Langer T, Saxena K, Schwalbe H. Chemical Biology (Prof. Dr. Stuart L. Schreiber, P. D. T. M. K. P. D. G., Ed.) 2008. Chemical Biology of Kinases Studied by NMR Spectroscopy; pp. 852–890. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stockman BJ, Kothe M, Kohls D, Weibley L, Connolly BJ, Sheils AL, Cao Q, Cheng AC, Yang L, Kamath AV, Ding YH, Charlton ME. Identification of allosteric PIF-pocket ligands for PDK1 using NMR-based fragment screening and 1H-15N TROSY experiments. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2009;73:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jahnke W, Grotzfeld RM, Pelle X, Strauss A, Fendrich G, Cowan-Jacob SW, Cotesta S, Fabbro D, Furet P, Mestan J, Marzinzik AL. Binding or bending: distinction of allosteric Abl kinase agonists from antagonists by an NMR-based conformational assay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7043–7048. doi: 10.1021/ja101837n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vajpai N, Strauss A, Fendrich G, Cowan-Jacob SW, Manley PW, Jahnke W, Grzesiek S. Backbone NMR resonance assignment of the Abelson kinase domain in complex with imatinib. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2008;2:41–42. doi: 10.1007/s12104-008-9079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maniatis T. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual / T. Maniatis, E.F. Fritsch, J. Sambrook. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marley J, Lu M, Bracken C. A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2001;20:71–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1011254402785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]