Abstract

Throughout life, thalamocortical (TC) network alternates between activated states (wake or rapid eye movement sleep) and slow oscillatory state dominating slow-wave sleep. The patterns of neuronal firing are different during these distinct states. I propose that due to relatively regular firing, the activated states preset some steady state synaptic plasticity and that the silent periods of slow-wave sleep contribute to a release from this steady state synaptic plasticity. In this respect, I discuss how states of vigilance affect short-, mid-, and long-term synaptic plasticity, intrinsic neuronal plasticity, as well as homeostatic plasticity. Finally, I suggest that slow oscillation is intrinsic property of cortical network and brain homeostatic mechanisms are tuned to use all forms of plasticity to bring cortical network to the state of slow oscillation. However, prolonged and profound shift from this homeostatic balance could lead to development of paroxysmal hyperexcitability and seizures as in the case of brain trauma.

Keywords: sleep, wake, oscillations, synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, intrinsic plasticity

Introduction

Neuronal plasticity is the ability of neurons to modify responses to incoming stimuli due to previous activities. In this process, a leading role is usually played by synaptic plasticity, but the neuronal output is also modified by intrinsic currents, which also reveal several forms of plasticity. Synaptic plasticity when occurs in the same pathway (connection) is called homosynaptic plasticity. If it occurs in different pathways, it is called heterosynaptic plasticity. Homeostatic plasticity down (up)-regulates cellular (network) excitability depending on high (low) levels of network activity. Homeostatic plasticity occurs not necessary at a synapse with altered levels of excitability. Neuronal plasticity can roughly be subdivided on short-, mid-, and long-term, with effects occurring on (a) sub-second, (b) second to minute, and (c) minute to hours scale accordingly. All activity-dependent increase in neuronal responses is usually called facilitation and/or potentiation, and a decrease in neuronal responses is called depression. Short-term plasticity is implicated in the network operations facilitating or preventing signal transmission. Mid- and long-term plasticity might be implicated in the formation of short-term memory including learning and forgetting.

Throughout life, neurons of thalamocortical (TC) system remain spontaneously active and fire action potentials. This presets some state of neuronal plasticity. During quiet wakefulness and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep, most of neurons in TC system fire spontaneously in a tonic mode presetting steady state of neuronal plasticity. During slow-wave sleep (SWS), the neurons within TC system fire single action potentials and/or bursts spikes separated by long-lasting periods of silence. During silent periods, there should be a recovery from steady state neuronal plasticity. The patterns of neuronal firing during SWS are reminiscent of the patterns of electrical stimulation used to evoke long-term form of plasticity: repeated activation around 1 Hz reminiscent to long-term depression (LTD) protocol (periods of slow waves) and high-frequency spike trains reminiscent to long-term potentiation (LTP) protocol (neuronal firing within active periods of slow waves). Therefore, the main goal of this chapter is to estimate the extent of different forms of steady state synaptic plasticity created by natural brain activities.

Sleep and waking oscillations

Neuronal activities within TC system during sleep and waking states

From an electrophysiological point of view, waking state is defined by activated electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns, eye movements, and variable muscle tone. During SWS, EEG activity is dominated by slow waves, no eye movements, and a stable muscle tone, and during REM sleep, the EEG is activated, the muscle tone is absent, and occasionally periodic eye movements occur (Steriade, 1996; Steriade and McCarley, 1990, 2005). Recently, we published several reviews summarizing current knowledge on cellular activities recorded within TC system during sleep–wake cycle (Bazhenov and Timofeev, 2006, Bazhenov and Timofeev, 2007; Chauvette et al., 2007; Steriade and Timofeev, 2003; Timofeev and Bazhenov, 2005a). Thus, I will provide only a brief summary. Up to now, there is only one published intracellular recording from TC neuron demonstrating its relatively hyperpolarized and fluctuating membrane potential during SWS and its relatively depolarized membrane potential during REM sleep (Hirsch et al., 1983). This recording and a multitude of extracellular recordings from non-identified thalamic neurons led to speculations that both TC neurons and reticular thalamic neurons are hyperpolarized during SWS and fire spike bursts and are depolarized during both REM sleep and waking state and fire in tonic mode (reviewed in Steriade et al., 1993b). This conclusion was based on the fact that, at hyperpolarized voltages, TC neurons (Jahnsen and Llinás, 1984a,b; Steriade and Deschenes, 1984) and reticular thalamic neurons (Avanzini et al., 1989; Contreras et al., 1993) fire low-threshold spike (LTS) bursts, and at depolarized voltages, they fire in tonic mode. Recent studies revealed, however, that intracellularly applied hyperpolarizing current pulses during waking state easily elicit LTS bursts (Woody et al., 2003) and that at least some TC neurons fire spontaneous spike bursts during waking (unlikely alert) state (Bezdudnaya et al., 2006). Intracellular recordings from reticular thalamic neurons from anesthetized cats revealed that if some neurons from hyperpolarizing state generate bursts of action potentials that rapidly inactivate, the other neurons, so-called bistable cells, generated burst that was followed by long-lasting tonic firing (Fuentealba et al., 2005). This suggests that during sleep at least some reticular thalamic neurons do not fire in exclusively bursting mode.

After an initial description of slow oscillation (<1 Hz) in TC system (Steriade et al., 1993a,c, d), simultaneous intracellular and field potential recordings revealed that during EEG depth-positive (surface negative) wave the cortical neurons are hyperpolarized and during EEG depth -negative (surface positive) wave the cortical neurons are depolarized and fire action potentials (Contreras and Steriade, 1995). Stimulation of activating (cholinergic) systems leads to abolishment of hyperpolarizing potentials and induce continuous neuronal firing (Metherate and Ashe, 1993). About a decade ago, we obtained the first intracellular recordings from cortical neurons during different states of vigilance (Bazhenov et al., 2002; Mukovski et al., 2007; Steriade et al., 2001; Timofeev et al., 2000b, 2001). These recordings demonstrated that, during SWS, all recorded neurons were hyperpolarized and had no synaptic events during depth-positive EEG wave. During depth-negative EEG waves of SWS, the cortical neurons were depolarized and fired action potentials (Fig. 1). All cortical neurons were active (revealed synaptic events) during waking state (Fig. 1) and REM sleep (not shown). These results are being confirmed now in other laboratories (B. Haider and I. Lampl, personal communications). Similar patterns of activity were also found in striatal medium spiny neurons (Mahon et al., 2006). However, two studies from the same lab, using whole-cell recording technique conducted on supragranular neurons from somatosensory cortex of mice, demonstrated the presence of large amplitude membrane potential fluctuations during quiet wakefulness, and steady depolarization induced by whiskers activities (Crochet and Petersen, 2006; Poulet and Petersen, 2008). The difference in those results might be due to the fact that cortical network of carnivores, primates, and many other species has intensive “patchy” local horizontal connectivity that is absent in rodent brain (reviewed in Douglas and Martin, 2004; Sanchez-Vives et al., 2007). Distinct from well-accepted beliefs (Rockel et al., 1980), it is now clear that the neuronal density is different in different species (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2008; Rakic, 2008) and it is low in mice. It was shown that a low number of interconnected cortical neurons create unfavorable conditions for maintenance of spontaneous active states (Timofeev et al., 2000a). This could be another reason for inability of mice cortex to maintain persistent active state during quiet wakefulness. We also demonstrated that during active phases of sleep and waking state, some cortical neurons reveal fast prepotentials (FPPs) (Crochet et al., 2004), suggesting the presence of active depolarizing events in dendrites (Spencer and Kandel, 1961; Timofeev and Steriade, 1997). Although the basic features of active and silent states in cortical neurons recorded during SWS and several forms of anesthesia are similar, there are some fundamental differences. Estimation of total excitatory and inhibitory currents impinging onto cortical neurons during slow oscillation performed in slices and in anesthetized preparations show nearly perfect balance of excitation and inhibition (Doi et al., 2007; Haider et al., 2006; Rudolph et al., 2005; Shu et al., 2003). However, similar measurements performed during natural states of vigilance demonstrated that inhibition dominates during active states of sleep and during waking states (Rudolph et al., 2007). Another feature that we demonstrated only in non-anesthetized preparations is that a majority of action potentials was preceded by a brief inhibitory postsynaptic potential (Timofeev et al., 2001). Our further study shows that spontaneous firing during natural states of vigilance occur as result of a decrease in inhibitory conductances and not as result of increase in excitation (Rudolph et al., 2007). Therefore, firing dynamics, critical for synaptic plasticity, are different in anesthetized and nonanesthetized preparations.

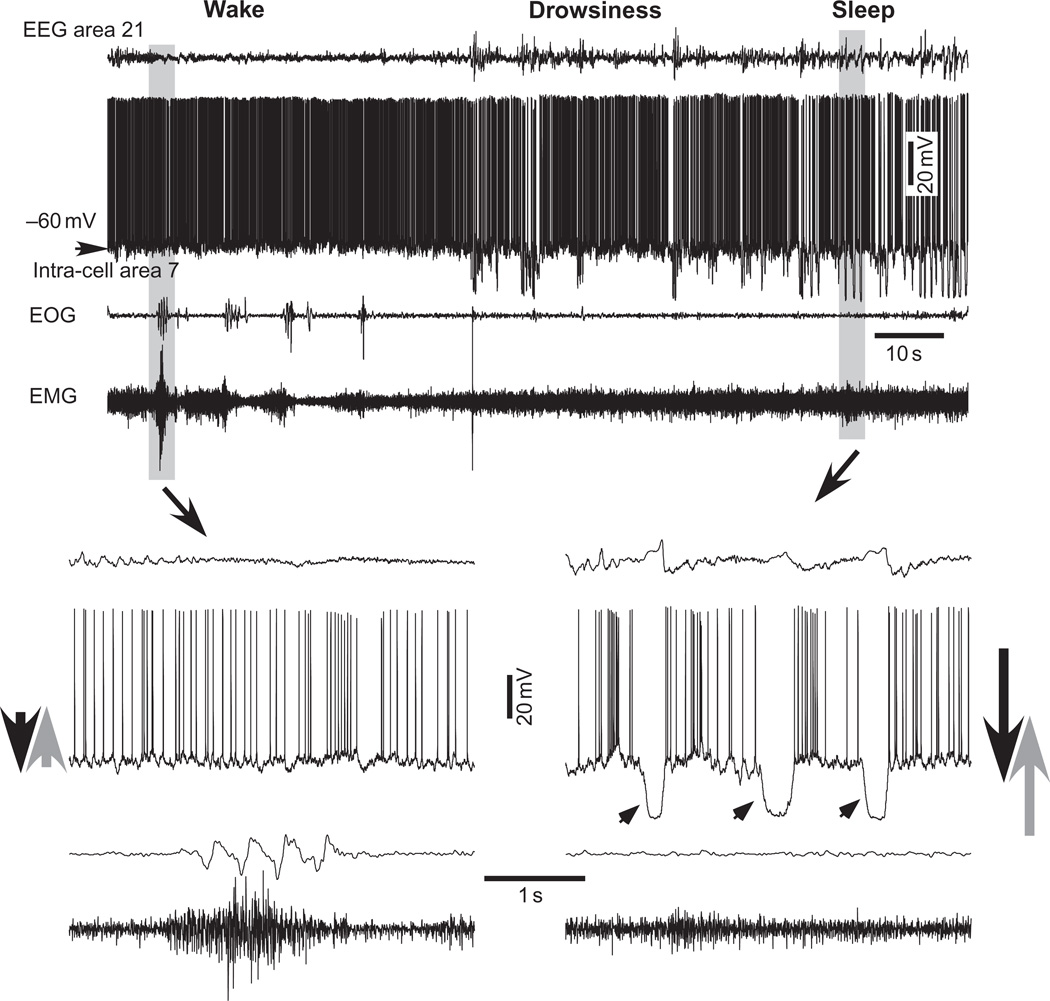

Fig. 1.

Cortical intracellular correlates of waking, drowsiness, and slow-wave sleep. The four traces depict (from top to bottom): EEG from area 21, intracellular activity of area 7 neuron (membrane potential is indicated, −60 mV), electrooculogram (EOG), and electromiogram (EMG). Low-amplitude and high-frequency field potential oscillations, tonic firing with little fluctuations in the membrane potential, and muscle tone with periodic contractions are characteristics of the waking state. A periodic slow waves accompanied with neuronal hyperpolarization appear during drowsiness. High-amplitude and low-frequency field potentials, intracellular cyclic hyperpolarizing potentials, and stable muscle tone are distinctive features of SWS. Parts indicated by arrows are expanded below. Note cyclic hyperpolarizations in SWS (indicated by arrowheads in right bottom graph). Large arrows at leftmost and rightmost parts of the bottom graphs tentatively indicate levels of de- and hyperpolarizing influences during sleep and waking states. (Modified from Timofeev and Bazhenov, 2005b).

Surprisingly up to now, there are no reliable studies that investigate mean spontaneous firing frequencies of cortical neurons during different states of vigilance. Early studies conducted on spontaneously firing neurons are controversial. Evarts with collaborator has shown that mean firing rates during SWS and waking states were similar around 5–7 Hz (Evarts, 1962). Later, Noda and Adey showed that the mean firing frequency during waking state is 13/s; SWS, 10–12/s; and REM sleep, 22/s (Noda and Adey, 1970a) with lower variability of interspike intervals during brain-activated states (Noda and Adey, 1970c). In these studies, the neurons with very low firing rates and spontaneously silent neurons were not included in analysis. Our intracellular study, that included spontaneously silent neurons, showed that during waking state the mean firing frequency was 15.7 Hz; during SWS, 11.4 Hz; and during REM sleep, 17.9 Hz, but these differences were not statistically significant (Steriade et al., 2001). Neocortical neurons reveal at least four distinct electrophysiological types: (a) regular-spiking (RS), (b) intrinsically bursting, (c) fast rhythmic bursting (FRB), and (d) fast-spiking (FS) (Gray and McCormick, 1996; McCormick et al., 1985; Steriade, 2004; Steriade et al., 1998a). We further showed that the RS neurons fire around 10–12 Hz during all states of vigilance, FS neurons fire more during brain activated states (wake, REM sleep) compared to SWS, and FRB neurons fire less during both sleep states compared to waking state (Steriade et al., 2001). In this study, the intracellular recordings were done with pipettes filled with high concentrations of potassium acetate, which likely depolarizes neurons and affects their firing rates (Waters and Helmchen, 2006). Recent patch-clamp recordings, from cortical neurons during waking state, demonstrated much lower spontaneous firing frequencies (0.6–1.5 Hz) (Constantinople and Bruno, 2011; Crochet and Petersen, 2006; Margrie et al., 2002; Poulet and Petersen, 2008) than in all previous studies. That could be explained by at least three different facts: (a) wash out of cell with patch pipette content, (b) the use of artificial cerebrospinal fluid on cortical surface that affects extracellular milieu and change neuronal excitability (Seigneur and Timofeev, 2010), and (c) recordings from superficial neurons that can fire with much lower rates, compared to other cortical neurons (Chauvette et al., 2010; Constantinople and Bruno, 2011). Using Ca2+ imaging from awaken mouse, a recent study shows also firing rates 0.5 Hz in superficial cortical neurons (Greenberg et al., 2008). In this experiment too, ACSF with high extracellular Ca2+ concentration (hyperpolarizing factor) was used. Therefore, steady state synaptic plasticity in neocortex seems to depend on the origin of presynaptic neurons: synapses formed by the axons of deeply lying neurons are likely to express strong values of steady state synaptic plasticity as compared to more superficially lying neurons.

Neuronal plasticity

Synaptic plasticity

Short-term synaptic plasticity is a ubiquitous property of cortical circuitry. Short-term dynamics could be absent in some particular synapses (Arenz et al., 2008).

Short-term plasticity

The effects of short-term synaptic plasticity usually do not exceed 1 s. Mechanisms of short-term plasticity were summarized in several recent reviews (Schwarz, 2003; Zucker and Regehr, 2002). Thus, I will provide a brief summary of known mechanisms and point to inconsistencies applied for cerebral cortex. Action potentials arriving to presynaptic membrane induce an elevation of [Ca2+]i. Classical studies of the neuromuscular junction identify the vesicle as quantum of synaptic transmission (Katz, 1969). Short-term synaptic facilitation is dependent on the elevation of presynaptic Ca2+ due to preceding presynaptic spikes and is called residual Ca2+ (Shahrezaei and Delaney, 2005; Tank et al., 1995). Higher [Ca2+]i levels increase mediator release probability to following stimuli that leads to facilitating responses (Markram et al., 1998). Colocalization of Ca2+ channel micro-domains with releasable pool of synaptic vesicles plays a critical role in the time course of synaptic facilitation (Becherer et al., 2003; Muller et al., 2005; Parekh, 2008; Qian and Noebels, 2001; Shahrezaei and Delaney, 2004, 2005). [Ca2+]e can also directly regulate postsynaptic efficacy (Hardingham et al., 2006). Short-term synaptic depression is usually attributed to a depletion of some pool of readily releasable vesicles (Markram, 1997; Markram et al., 1997, 1998; Zucker and Regehr, 2002). In cortical pyramidal neurons, each synapse contains one active zone with 2–20 docked vesicles (Harris and Sultan, 1995; Markram, 1997; Markram et al., 1997, 1998; Schikorski and Stevens, 1997, 1999). Although some studies have found evidence for multiple quantal release in central synapses (Auger et al., 1998; Isaac et al., 1998; Oertner et al., 2002; Tong and Jahr, 1994; Wadiche and Jahr, 2001), other experiments indicate that at most a single vesicle can be released in response to an action potential (Auger and Marty, 2000; Hanse and Gustafsson, 2001; Redman, 1990; Stevens and Wang, 1995; Triller and Korn, 1982). Thus, on most occasions in depressing neocortical synapses, a number of synaptic failures will grove with a progression of stimulation. Connections between excitatory cells display short-term depression (Abbott et al., 1997; Finnerty et al., 1999; Galarreta and Hestrin, 1998; Hempel et al., 2000; Thomson and Deuchars, 1997; Tsodyks and Markram, 1997; Varela et al., 1999) or facilitation (Reyes and Sakmann, 1999; Stratford et al., 1996) that is frequency dependent. Connections from excitatory cells onto inhibitory cells facilitate (Gibson et al., 1999; Helmstaedter et al., 2008; Markram et al., 1998; Reyes et al., 1998; Thomson et al., 1993) or depress (Buhl et al., 1997; Galarreta and Hestrin, 1998; Gibson et al., 1999; Helmstaedter et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 1998; Rozov et al., 2001; Tarczy-Hornoch et al., 1998). Connections from inhibitory cells onto excitatory cells depress (Castro-Alamancos and Connors, 1996a; Deisz and Prince, 1989; Galarreta and Hestrin, 1998; Gupta et al., 2000; Reyes et al., 1998; Tarczy-Hornoch et al., 1998; Varela et al., 1999). Connections between inhibitory cells depress (Galarreta and Hestrin, 1999; Gibson et al., 1999; Gupta et al., 2000; Tamas et al., 2000) or facilitate (Gupta et al., 2000). Extrinsic afferents from the thalamus depress (Gibson et al., 1999; Gil et al., 1997, 1999; Sanchez-Vives et al., 1998; Stratford et al., 1996). In response upon a train of stimuli, some particular connections display initial facilitation, followed by depression (Wang et al., 2006). The difference in depression/facilitation depends on properties of postsynaptic target (interneuron vs. pyramidal neuron) (Markram et al., 1998) and on the location of the target (e.g., layer 4 vs. layers 2 and 3) (Helmstaedter et al., 2008). Mediator release probability, connection probability, and sign and extent of synaptic plasticity for the same type of connections depend also on species (rats vs. cats) (Bannister and Thomson, 2007; Brémaud et al., 2007), although membrane properties of pyramidal neurons and interneurons are similar in monkey, cats, and rodents (Povysheva et al., 2006).

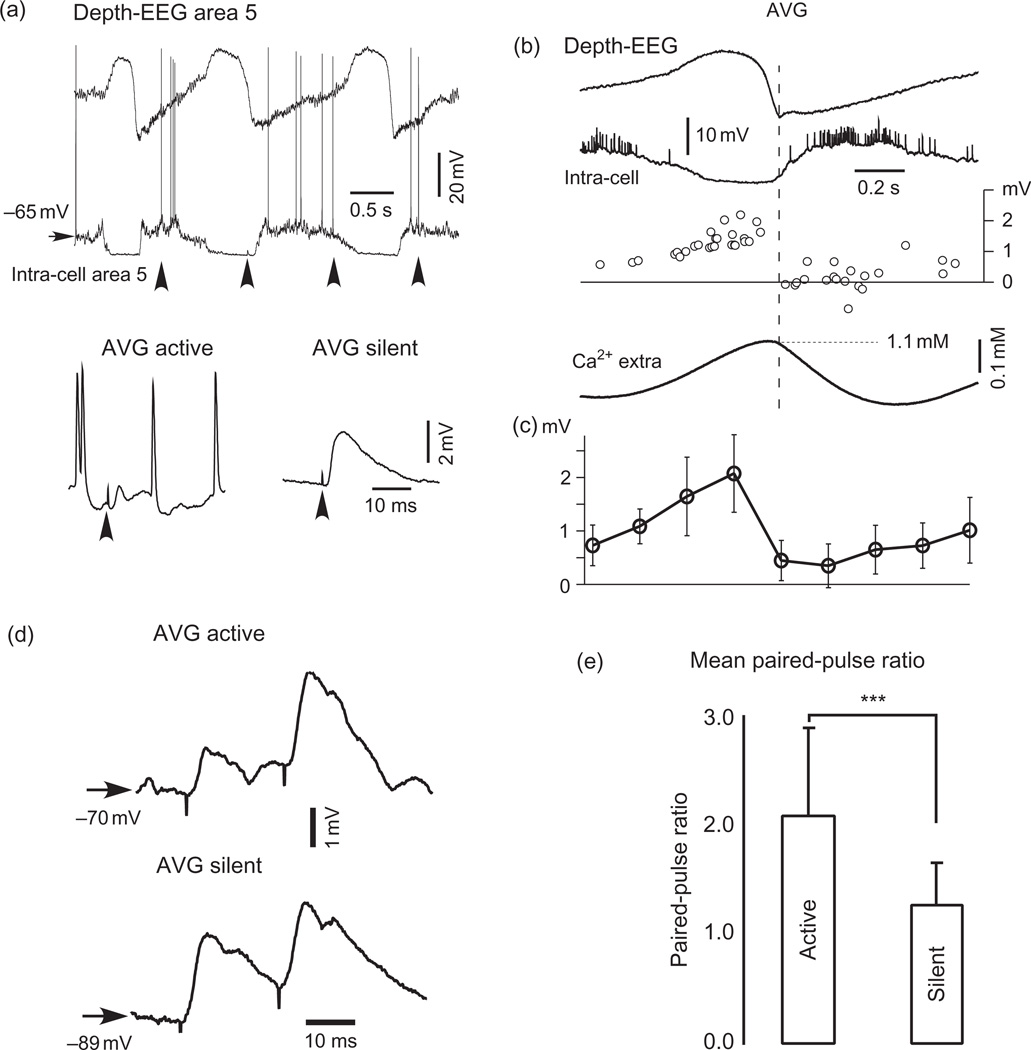

The above-mentioned results on synaptic properties cannot be superimposed directly on the understanding of brain functioning because of several technical problems: (a) all these studies were done in vitro, in silent network; therefore, the effects of network activity on responses were not investigated. Multiple in vivo studies, including ours, indicate a dramatic influence of ongoing network activity on neuronal responses (Arieli et al., 1996; Contreras et al., 1996; Fuentealba et al., 2004; Greenberg et al., 2008; Haider et al., 2006; Hasenstaub et al., 2007; Hesselmann et al., 2008; Kisley and Gerstein, 1999; Petersen et al., 2003; Rosanova and Timofeev, 2005; Timofeev et al., 1996). The total neuronal output is significantly impaired by shunting inhibition (Borg-Graham et al., 1998; Hirsch et al., 1998), which is present during spontaneous active network states, but absent during silent network states. The effects of short-term plasticity are less pronounced in vivo, compared to in vitro conditions (Reig and Sanchez-Vives, 2007; Reig et al., 2006). In large neuronal networks in vivo, the total output effect also depends on spatial and temporal summation. We have shown that when a neocortical network is silent (isolated slab), many neurons show depression and when the network is more active many neurons show facilitation (Crochet et al., 2006; Timofeev et al., 2002b). (b) The above-mentioned in vitro studies of plasticity were done in high [Ca2+]e (2–3.5 mM). Ca2+ is a primary ion responsible for mediator release (Katz, 1969; Katz and Miledi, 1968), affecting the release probability. Multiple studies show that (i) mean concentration of extracellular Ca2+ in vivo is lower and (ii) during cortical slow oscillation it fluctuates between 1.0 mM (active network states) and 1.2 mM (silent network states, Fig. 2) and drops to 0.6 mM during paroxysmal activities (Crochet et al., 2005; Massimini and Amzica, 2001; Pumain et al., 1983). Even very reliable synapses generate multiple failures at Ca2+ concentration 1.0 mM (Silver et al., 2003). We have shown that, during silent network states, the mediator release probability is much higher than during active network state and short-term depression during silent states changes to short-term facilitation during active states (Fig. 2) (Crochet et al., 2005). (c) In the majority of experiments on synaptic plasticity, the presynaptic stimuli are delivered at fixed frequencies, while in the brain, the spontaneous neuronal firing occurs with very variable interspike intervals (Noda and Adey, 1970a,b,c). It appears that stimulation with “natural” pattern of presynaptic spikes induces very different postsynaptic effects as compared to stimulation with fixed frequencies (Birtoli and Ulrich, 2004; Rosanova and Ulrich, 2005). Therefore, the synaptic responses induced by spontaneous presynaptic spikes in vivo depend on network state and can be either facilitating or depressing for the same synapse.

Fig. 2.

Activity-dependent modulation and short-term plasticity of responses elicited by microstimulation. (a) A period of spontaneous activity in neocortex in ketamine–xylazine anesthetized cat (upper panel) and averaged (AVG) responses (total averages) to microstimulation during active and silent network states (lower panel). Each average was obtained from more than 10 segments that preceded (right) or followed (left) the onset of EEG depth negativity. Arrowheads indicate the time of stimulation. (b) Wave-triggered average of EEG, intracellular activities, and [Ca2+]o as well as amplitude of intracellular events (responses and failures) triggered by microstimuli applied during different phases of slow oscillation. The first maximum of EEG-depth negativity was taken as 0 time. (c) Averaged amplitude of microstimulus-evoked events from nine neurons during different phases of slow oscillation. The amplitude was averaged for successive time windows of 200 ms. The time base in (b) and (c) is the same. (d) Averaged paired-pulse responses (all stimuli) of a neuron during active and silent network states in ketamine–xylazine anesthetized cat. (e) Mean paired-pulse ratio during active and silent states in 14 tested neurons. The increase in the paired-pulse ratio during active states was significant (p < 0.001, Student's paired t test). (Modified from Crochet et al., 2005).

It is clear that reliable and robust processing of information in the brain requires cooperative neuronal activity when individual neurons do not themselves respond reliably (Rangan et al., 2008). The effects of cooperative action on postsynaptic neurons could be very different from a sum of action at individual synapses. We have previously shown that, in neocortical slabs, low-intensity 10 Hz stimulation either did not induce dynamic changes of responses or induced short-term synaptic depression, but in all cases with large amplitude stimuli (involvement of a large number of neurons), the same frequency of stimulation invariantly induced intracortical augmenting responses (see fig. 1 and fig. 2 in Timofeev etal., 2002b). Our modeling study demonstrated that when both excitatory and inhibitory synapses reveal short-term depression, the network augmenting responses can be obtained if depression at inhibitory synapses is slightly weaker than depression at excitatory synapses (Houweling et al., 2002).

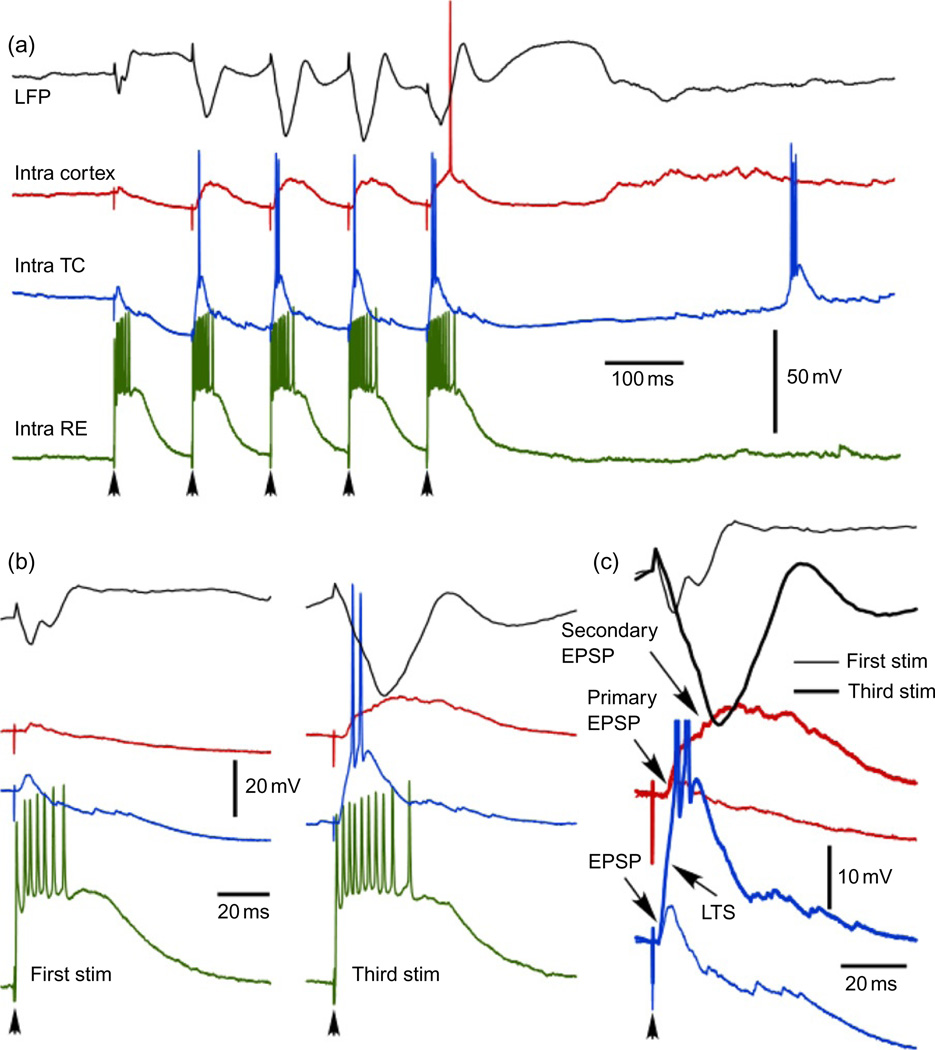

Augmenting responses

Augmenting responses is a particular form of shortterm neuronal plasticity that requires both synaptic dynamics and activation of some types of intrinsic neuronal currents. The augmenting responses were initially described by Morrison and Dempsey and were used mainly as a mode of spindle activities (Morin and Steriade, 1981; Morison and Dempsey, 1942, 1943). Augmenting responses can be reliably elicited within intact TC system (Bazhenov et al., 1998b; Morison and Dempsey, 1943; Steriade et al., 1998b), thalamus of decorticated animals (Bazhenov et al., 1998a; Houweling et al., 1999; Timofeev and Steriade, 1998), or isolated cortical preparations (Castro-Alamancos and Connors, 1996a,b; Houweling et al., 2002; Timofeev et al., 2002b) by applying rhythmic stimuli with frequency around 10 Hz (Fig. 3). In decorticated cats, augmenting responses in thalamus appear in two forms: high threshold and low threshold. High-threshold responses emerge as progressive increase in the response amplitude from the first to the third to fifth consecutive stimuli (Steriade and Timofeev, 1997; Timofeev and Steriade, 1998). They can occur either because synaptic facilitation or because of activation of high-threshold intrinsic currents. During low-threshold responses, the first stimulus elicits excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) in TC and reticular thalamic neurons. Due to burst firing of RE neurons driven by initial EPSP, the EPSP in TC neurons is followed by an inhibitory postsynaptic potential(IPSP). The second and consecutive stimuli arrive when TC neuron is hyperpolarized and the EPSP evoked in TC neuron at hyperpolarized voltages triggers a LTS that augment the response (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Augmenting responses in thalamocortical system. (a) Four different traces show typical responses of motor part of thalamocortical system to 10 Hz pulse train applied to thalamic ventro-lateral (VL) nucleus. Black—local field potential recorded from area 4, red—cortical regular-spiking neurons from area 4, blue—thalmocortical neuron from VL nucleus, green—reticular thalamic neuron from rostrolateral sector of reticular thalamic nucleus. (b and c) Magnified responses to the first and third stimuli. In response to the third stimulus note an increase in the number of spikes in reticular thalamic neuron, generation of LTS in thalamocortical neuron, generation of secondary depolarization in cortical neurons, and a dramatic increase in secondary component of cortical-evoked potential (I. Timofeev, unpublished observations).

The intracortical augmenting responses are generally weak. Experiments on slices demonstrated a leading role of intrinsically bursting neurons in the generation of augmenting responses (Castro-Alamancos and Connors, 1996b, c). In these experiments, the first stimulus induced EPSP and the second stimulus induced EPSP accompanied with intrinsic burst. However, in vivo experiments on neocortical slabs have shown that systematic comparison of intrinsically bursting neurons with other types of neurons does not indicate their leading role in the generation of augmenting responses, because they fire less action potentials and they are less depolarized as compared to other types of cortical neurons (Timofeev et al., 2002b). Experimental and modeling studies suggest that rhythmic cortical stimulation generally induces a depression of responses. The major mechanism of intracortical augmenting responses is mediated by a weak depression of inhibitory synapses at low frequencies and stronger depression of excitatory synapses (Houweling et al., 2002). An additional mechanism is based on powerful implication of fast rhythmic bursting neurons (Steriade and Timofeev, 2001). In the intact TC system, the augmenting responses are primarily based on low-threshold mechanism in the thalamus (Bazhenov et al., 1998b; Steriade et al., 1998b). Strong corticothalamic feedback reinforces burst firing of reticular thalamic neurons that result in a strong hyperpolarization of TC neurons, which generate LTS crowned with spike bursts and trigger secondary depolarization of cortical neurons (Fig. 3).

Therefore, augmenting responses is a form of short-term neuronal plasticity that is based on interaction of synaptic response and intrinsic currents. Like spindles, repeated induction of augmenting responses leads to a long-term enhancement of synaptic responses (Timofeev et al., 2002b), and eventually leads to the generation of self-sustained paroxysmal discharges (Nuñez et al., 1993; Timofeev et al., 1998).

Short-term heterosynaptic interactions

Each cortical neuron receives influences from 5000 to 60,000 synapses (Cragg, 1967; DeFelipe and Farinas, 1992). The interaction between synapses arising from different presynaptic neurons is a subject of heterosynaptic plasticity. The initial mechanism of heterosynaptic interaction is spatial summation (Eccles, 1964). Because the majority of high conductance inhibitory synapses of cortical and TC neurons are located on cell soma and excitatory synapses on dendrites, the shunting inhibition plays an important role in heterosynaptic interactions (Borg-Graham et al., 1998; Hirsch et al., 1998). We investigated the heterosynaptic interactions between either cortical and thalamic, or thalamic and cortical inputs (Fuentealba et al., 2004). In cortical neurons, these interactions generally produced a decrease in the peak amplitudes and depolarization area of evoked EPSPs elicited by a second stimulus, with maximal effect at ~10 ms and lasting from 60 to 100 ms. All neurons tested with thalamic followed by cortical stimuli showed a decrease in the apparent input resistance, the time course of which paralleled that of decreased responses, suggesting that shunting is the factor accounting for EPSP's decrease. Only half of neurons tested with cortical followed by thalamic stimuli displayed changes in input resistance. Spike shunting in the thalamus may account for those cases in which decreased synaptic responsiveness of cortical neurons was not associated with decreased input resistance because TC neurons showed decreased firing probability during cortical stimulation (Fuentealba et al., 2004). Heterosynaptic plasticity plays important role in a number of functions within TC system. It is implicated in coincidence detection (Calixto et al., 2008; Usrey et al., 2000), LTP (Dringenberg et al., 2007), and memory (Bailey et al., 2000).

Mid- and long-term plasticity

It is generally accepted that long-term synaptic plasticity is a basis of short-term memory. Midterm plasticity, sometimes called short-term facilitation (depression), occurs at a second to minute scale, and LTP/LTD (long-term depression) last for hours. LTP was discovered by Lømo in 1966 (first publication dated 1973 (Bliss and Lomo, 1973)) and it represents the long-lasting improvement in communication between two neurons. Later, the opposite phenomena, LTD, was found (Levy and Steward, 1979). Tetanic stimulation of presynaptic fibers with a train of 100 Hz for 1 s induces LTP. LTD can be induced either by low-frequency stimulation (homosynaptic LTD) or as result of inactivity in synapses on a neuron that have active synapses (heterosynaptic LTD). The high-frequency stimulation required for LTP induction is clearly an artificial phenomena because such a firing pattern does not exist in brain structures. Later, a theta burst stimulation protocol for induction of LTP was proposed (Larson and Lynch, 1986; Larson et al., 1986). It consists of three to four stimuli delivered at 100 Hz, applied every 200 ms. This is a common firing pattern of hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Kandel and Spencer, 1961). Classical LTP protocol and theta burst stimulation protocol share some molecular mechanisms (Nguyen and Kandel, 1997). The physiological effects of LTP in vivo depend on exact conditions of stimulation. In human, using transcranial magnetic stimulation method, continuous theta burst stimulation reduced motor-evoked potentials and short-interval intracortical inhibition (not enhanced as would be predicted from in vitro studies), whereas intermittent theta burst stimulation increased motor-evoked potentials and short-interval intracortical inhibition (Suppa et al., 2008). Potentiating or depressing effects of theta burst stimulation largely depend on previous activity. Without prior activity (like in isolated preparations) theta burst stimulation facilitated cortical responses, but when theta burst stimulation was preceded by activity, the responses were depressing (Gentner et al., 2008). Therefore, the steady state synaptic plasticity induced by spontaneous activities affects neuronal responses and investigation of plasticity using natural or artificial stimuli should be interpreted with regard to state-dependent steady state plasticity.

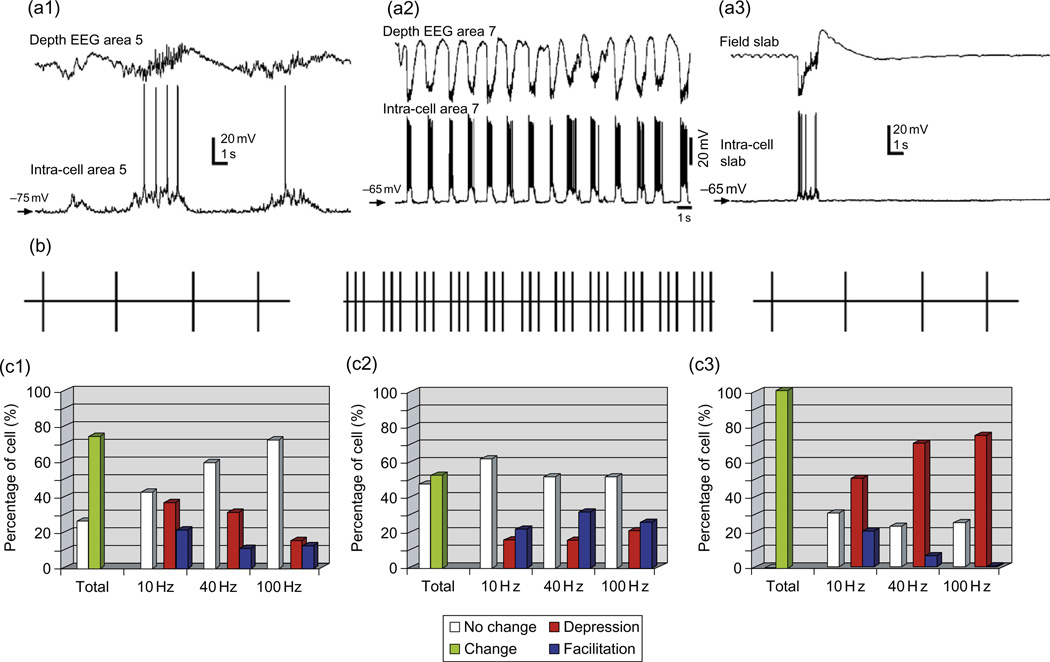

In recent reviews, we proposed that brain oscillations occurring either during sleep or during paroxysmal (seizure) activity induce some state of synaptic plasticity (Steriade and Timofeev, 2003; Timofeev and Bazhenov, 2005a). The efficacy of synaptic transmission affected by stimuli applied with patterns similar to naturally occurring oscillations was affected for duration of tens of minutes, thus termed mid-term plasticity (Cisse et al., 2004; Crochet et al., 2006; Nita et al., 2008; Timofeev et al., 2002b). We showed that in active cortical network more than 50% of synapses showed no mid-term plasticity, but in silent networks most of synapses showed mid-term synaptic depression (Crochet et al., 2006). We also showed that each particular frequency could induce mid-term facilitation or depression in the same synapses (Cisse et al., 2004; Crochet et al., 2006). In order to induce plastic changes in most of these studies, others and we used rhythmic stimuli with frequencies of 10, 40, and 100 Hz, repeated every second, to imitate spindles, gamma, and ripple activity grouped by slow cortical oscillation (Steriade et al., 1993c). Under ketamine–xylazine anesthesia (very active networks), the repeated pulse trains induced mid-term changes of responses in only half of neurons, and in neurons in which plasticity was induced, it was primarily mid-term facilitation (Fig. 4a2 and c2). With a lower level of network activity (barbiturate anesthesia), the mid-term plasticity was induced in three-fourth of recorded neurons, and it was mid-term depression in the majority of neurons (Fig. 4a and c1). And finally in mainly silent networks (neocortical slab in ketamine–xylazine anesthetized cat), the midterm plasticity was found in all tested neurons (although not at all tested frequencies) and midterm synaptic depression was a dominate type of response (Fig. 3a3 and c3). These results are in agreement with data on short-term synaptic dynamics, which also were either dramatically reduced or abolished with an increase in network activity (Reig et al., 2006). However, the firing patterns of cortical neurons are not as regular as patterns of major brain oscillations. A recent in vitro study demonstrated that if stimuli were applied with a pattern of naturally occurring spikes, both short- and long-term potentiation were significantly enhanced compared to just 10 Hz trains (Rosanova and Ulrich, 2005). There are, however, some problems with this study. (a) Only one pattern of stimuli was used, but neurons during natural behavioral states do not repeat the same pattern of spiking (Dunin-Barkowski et al., 2006). (b) Experiments were done in high Ca2+ conditions (2 mM) compared to in vivo (1.0–1.2 mM), which affected synaptic release. (c) Postsynaptic neuron was stimulated with brief intracellular current pulses (2 ms), although depolarization that takes place during active state of sleep slow oscillation lasts for several hundred milliseconds (Avramescu and Timofeev, 2008; Chauvette et al., 2010; Volgushev et al., 2006) and lasts for the duration of waking or REM sleep states (Rudolph et al., 2007; Steriade et al., 2001; Timofeev et al., 2001). Therefore, further investigations are needed to understand how natural spike trains contribute to synaptic plasticity.

Fig. 4.

Mid-term plasticity in cortical network with different levels of activity. (a) Examples of field potential (upper trace) and intracellular (lower trace) recordings from area five to seven cortical neurons during barbiturate anesthesia (a1), ketamine–xylazine anesthesia (a2) and neocortical slab of cat anesthetized with ketamine–xylazine (a3). (b) Experimental protocol in which single stimuli were applied every two seconds to collect control values of responses, single stimuli were followed by 10, 40, or 100 Hz pulse-trains. During extinction, single stimuli were applied every 2 s as in control. (c) Histograms showing the percentage of cells that displayed no change (white) or a change of the response (green) for at least one of the tested frequencies, and for each frequency the percentage of cells that displayed no change (white), a decrease (red), or an increase (blue) of the response. Experimental conditions in (c1–c3) are the same as in (a1–a3). (Modified from Crochet et al., 2006).

Multiple studies suggest that LTP and LTD may be implicated in memory formation (see reviews Bear and Abraham, 1996; Tsumoto, 1992). There was, however, direct experiment showing that mice lacking GluR-A subunit did not display associative LTP, but spatial memory in these animals was not affected (Zamanillo et al., 1999). This suggests that other than LTP forms of neuronal plasticity contribute to memory formation.

In sleep-deprived subjects, transcranial magnetic stimulation improved memory (Luber et al., 2008). It is likely that one of the effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation was to induce long-lasting silence of neurons (like sleep-silent states) (Massimini et al., 2007). My reading of these data is that repeated induction of neuronal silence was a factor that improved memory. The repeated neuronal silence during sleep slow oscillation (see below) is likely a leading mechanism of sleep-related neuronal plasticity and therefore memory formation.

Tononi and Cirelli proposed that many synapses in the brain are strengthened, or “potentiated,” by normal circuit use during wake. During sleep, the slow-wave neural activity resets the synapses, returning the brain to a baseline state (Tononi and Cirelli, 2003, 2006). So far there is no clear evidence on how slow oscillations might induce synaptic downscaling. Rather the opposite: (a) activation of muscarinic acetylcho-line receptors in vitro suppresses both thalamocortoical and intracortical synapses (Gil et al., 1997), suggesting that during both waking state and REM sleep these synapses are depressed and not potentiated as compared to SWS and (b) repeated trains of stimuli mimicking active phases of sleep slow oscillation induced a steady state synaptic depression, but a stimulus arriving after a few hundreds of milliseconds of silence produces a significant rebound in postsynaptic response (Galarreta and Hestrin, 1998, 2000). Although not regularly, multiple neurons of TC system fire continuously during waking state, and they alternate periods of activity and silence during SWS. Therefore, I propose that prolonged waking state produces steady state synaptic plasticity (depression in most of synapses), but silent periods of sleep slow oscillation serve to recover from this steady state synaptic plasticity. This hypothesis is partially supported by our current experiments. We investigate the dynamic changes of somatosensory-evoked potential during alternating states of vigilance in cats. After prolonged waking state, the initial component of somatosensory response was low. During the following SWS period, it fluctuated from failures to overshooting values of the control-evoked potential, but during the following waking state, the amplitude of the evoked potential was a double of that during prolonged waking period (Timofeev and Chauvette, 2009).

Intrinsic plasticity

Plasticity of intrinsic currents that could contribute to memory formation was largely investigated in invertebrates (Marder et al., 1996; Turrigiano et al., 1996). In cortical neurons, the plasticity of intrinsic currents was less studied. Several in vivo studies have shown that pairing of depolarizing current pulses eliciting spikes with synaptic volleys induces an increase in neuronal responsiveness for several minutes (Baranyi et al., 1991; Timofeev et al., 2002b). A recent in vitro study has shown that prolonged intracellular stimulation of layer 5 cortical neurons with depolarizing current pulses induced long-lasting enhancement of intrinsic neuronal excitability (Cudmore and Turrigiano, 2004). Repeated intracellular stimulation (400 ms current pulse applied every second) of layer 6 cortical pyramidal neurons shifts their firing pattern from regular-spiking to fast rhythmic bursting (Kang and Kayano, 1994). All this suggests an important role of plasticity of intrinsic currents in network operations, although the mechanisms mediating plasticity of intrinsic currents are not clear yet. These effects of intrinsic plasticity likely take place during sleep slow oscillation.

Homeostatic plasticity

Homeostatic plasticity is a form of plasticity that stabilizes the properties of neural circuits (Turrigiano, 1999; Turrigiano et al., 1998). Distinct from Hebbian mechanisms that are important for modifying neuronal circuitry selectively for each involved synapse, the homeostatic plasticity changes neuronal and network excitability in order to maintain some level of excitability when input conditions are altered. Evidence from in vitro studies suggest that chronic blockade of activity modifies synaptic strength and intrinsic neuronal excitability. After a few days of pharmacological blockade of activity in cortical cell cultures, the amplitudes of excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) and miniature EPSC (mEPSC) in pyramidal cells and quantal release probabilities increase in many (Murthy et al., 2001; Turrigiano et al., 1998; Watt et al., 2000), but not all connections (Kim and Tsien, 2008). Conversely, prolonged enhanced activity levels induced by blockade of synaptic inhibition or elevated [K+]o reduce the size of mEPSCs (Leslie et al., 2001; Lissin et al., 1998; Turrigiano et al., 1998). Synaptic scaling occurs in part postsynaptically by changes in the number of open channels (Turrigiano et al., 1998; Watt et al., 2000), although all synaptic components may increase (Murthy et al., 2001) including numbers of postsynaptic glutamate receptors (Liao et al., 1999; Lissin et al., 1998; O'Brien et al., 1998; Rao and Craig, 1997). There is a similar regulation of N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) currents by activity (Watt et al., 2000) (see, however, Lissin et al., 1998). Interestingly, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents are scaled down with activity blockade, in the opposite direction to excitatory currents. This effect is reversible (Rutherford et al., 1997) and is accompanied by a reduction in the number of open GABAA channels and GABAA receptors clustered at synaptic sites (Kilman et al., 2002). In addition, intrinsic excitability is regulated by activity. After chronic activity blockade, Na+ currents increase and K+ currents decrease in size, resulting in an enhanced responsiveness of pyramidal cells to current injection (Desai et al., 1999). Some of these processes may also occur in vivo (Desai et al., 2002).

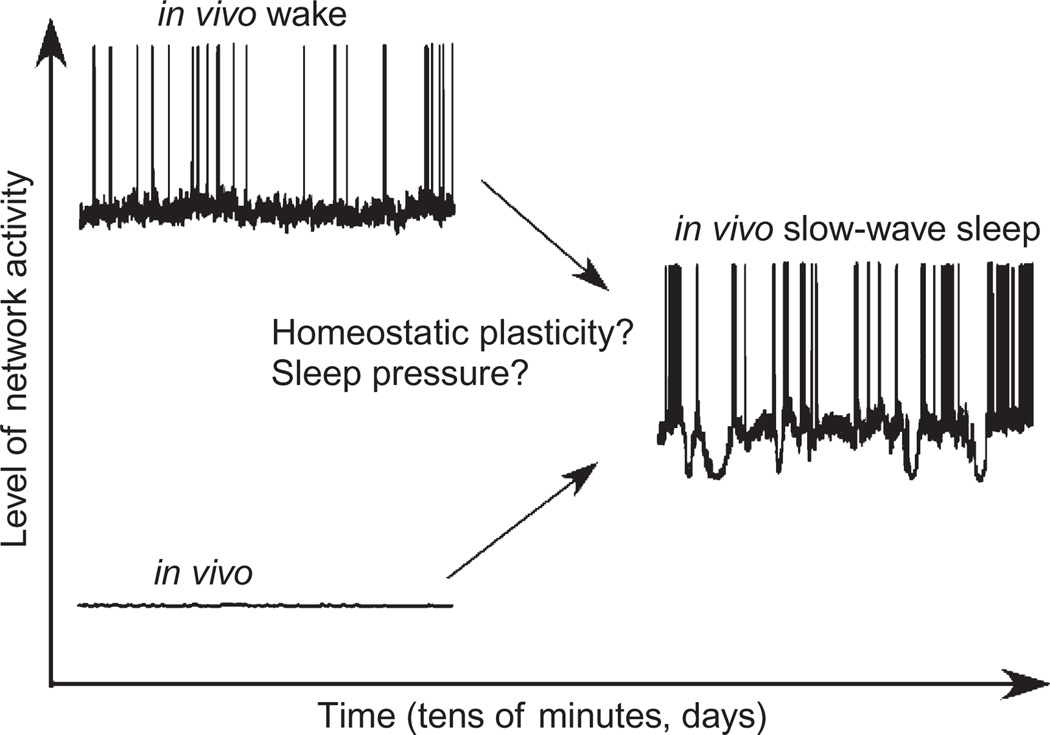

Two issues need to be discussed in relation of SWS and homeostatic plasticity. First, after a prolong period of waking, the slow-wave activity (Achermann and Borbely, 2003) and neuronal firing (Vyazovskiy et al., 2009) are increased and they are decreased during SWS. It appears that slow-wave activity is an intrinsic property of cortical networks and cortical networks tend to achieve this state. Activities of neuromodulatory systems, during activated brain states, suppress cortical intrinsic slow oscillation that progressively increases sleep pressure and eventually leads to the onset of SWS. In an early state of deafferented cortical preparations like cell cultures (Sun et al., 2010), neocortical slices (Compte et al., 2008), or neocortical slabs (Timofeev et al., 2000a), the spontaneous slow-wave activity is low. However, the slow-wave activity increases after some period of time lasting from minutes to days. Therefore, starting from two absolutely different initial conditions (activated brain states in intact animals vs. isolated brain preparations), the cortical network comes to the same state of slow-wave activity, suggesting that slow-wave activity is a homeostatically balanced state of cortical network (Fig. 5). The exact cellular mechanisms of this plastic changes remain to be elucidated, but it is clear that waking state should produce some downregulation of synaptic or intrinsic excitability and that in isolated brain preparations the neuronal excitability should be upregulated.

Fig. 5.

After certain period of time, active (waking state) or silent (typical in vitro state) cortical network transform activities to slow oscillation (I. Timofeev, unpublished observations).

Second point is a link between sleep, homeostatic plasticity, and neocortical epilepsy. A set of modeling studies demonstrated that partial cortical deafferentation induces homeostatic upregulation of neuronal excitability (Frohlich et al., 2008, 2010; Houweling et al., 2005). However, when the damage exceeds some threshold, the upregulation of neuronal excitability becomes stronger and the same cellular mechanisms that were homeostatic with smaller damage become epileptogenic with a bigger damage. How does the transition to paroxysmal states occur? The neocortex is an important component in many forms of paroxysmal activity, and it is actively involved in the generation of paroxysmal discharges (Contreras and Steriade, 1995; Crunelli and Leresche, 2002; Meeren et al., 2002; Pinault et al., 1998; Steriade and Contreras, 1998; Steriade et al., 1998a; Timofeev et al., 1998, Timofeev 2002a,b, 2004; Timofeev and Steriade, 2004). A number of neocortical seizures are nocturnal (Gowers, 1885; Timofeev, 2010, 2011), meaning they develop without discontinuity from sleep oscillations. As it is described at the beginning, during activated states the depolarizing and hyperpolarizing influences converging onto cortical neurons (small arrows in Fig. 1 bottom left) maintain relatively stable levels of membrane potential. The state of the SWS is characterized by the presence of long-lasting periods of disfacilitation associated with neuronal hyperpolarization and therefore silence (Timofeev et al., 2001), thus de- and hyperpolarizing influences set neurons to oscillate with large amplitudes (large arrows in Fig. 1 bottom right). During wave component of spike-wave seizures, the neurons are also hyperpolarized. Seemingly, to SWS this hyperpolarization is mediated by disfacilitation, but additionally by some active K+ conductances (Timofeev et al., 2004). The presence of these hyperpolarizing potentials during seizures contributes to seizure-induced increase in intrinsic neuronal excitability (Timofeev and Steriade, 2004; Timofeev et al., 2002a, 2004). The penetrating wounds or acute experimental deafferentation has been described as strong epileptogenic factors (Dinner, 1993; Jacobs and Prince, 2005; Jin et al., 2005; Kollevold, 1976; Prince et al., 1997; Topolnik et al., 2003a,b). In conditions of cortical trauma, some of the axons impinging onto postsynaptic neurons are damaged and not functioning properly, which creates a partial differentiation that may increase the sensitivity of cortical neurons in those foci and in surrounding areas. Therefore, the balance of excitation and inhibition (Haider et al., 2006; Rudolph et al., 2007) as well as activity and silence, shifts toward silence in differenced cortex. Indeed, intracellular recordings from differenced cortex in vivo demonstrated that (a) in anesthetized animals, the duration of silent states progressively increases with the time from differentiations and, as rebound, the instantaneous firing rates during active network states dramatically increase (Avramescu and Timofeev, 2008).

(b) Intracellular recordings from differenced cortex in nonanesthetized animals demonstrate the presence of silent states during both REM sleep and waking states (Nita et al., 2007; Timofeev et al., 2010), therefore prolonging the total network silence and increasing neuronal excitability that eventually leads to seizure generation.

Yin and Yang of brain oscillations and plasticity

The presence of bidirectional links between neuronal plasticity and sleep–wake oscillations is evident. On one hand, the repeated neuronal firing modulated by TC oscillations induces some state of plasticity in neurons. Therefore, the new information arrives to neurons (synaptic contacts) that are already at some state of steady plasticity (depression or facilitation). Because of almost continuous firing of neurons during waking state, this steady state plasticity is continuously present during waking state and the silent periods of SWS contribute to the release from this steady state neuronal plasticity. On the other hand, the sleep and wake oscillations are mediated by activities of interacting neurons. Because these neuronal networks display synaptic plasticity, this plasticity contributes to the generation of network oscillations. It has been proposed that synaptic depression contributes to the termination of active network states of sleep slow oscillation (Bazhenov et al., 2002; Compte et al., 2003; Hill and Tononi, 2004). It is likely that an increase in [Ca2+]e (Fig. 2) that facilitates synaptic release contributes to the generation of active network states.

Acknowledgments

I thank S. Ftomov and J. Seigneur for excellent technical assistance and all my trainees for their contribution to different aspects of our studies of TC physiology. Research activities in my laboratory are supported by grants (MOP-67175 and MOP-37862) from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant 298475), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS060870 and 1R01NS059740). A part of my salary is covered by Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec via Chercheur Nationale program.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- [Ca2+]e

extracellular calcium concentration

- EPSP

excitatory postsynaptic potential

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term facilitation

- LTS

low-threshold spike

- SWS

slow-wave sleep

References

- Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB. Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science. 1997;275:220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achermann P, Borbely AA. Mathematical models of sleep regulation. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2003;8:s683–s693. doi: 10.2741/1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenz A, Silver RA, Schaefer AT, Margrie TW. The contribution of single synapses to sensory representation in vivo. Science. 2008;321:977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1158391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli A, Sterkin A, Grinvald A, Aertsen A. Dynamics of ongoing activity: Explanation of the large variability in evoked cortical responses. Science. 1996;273:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger C, Kondo S, Marty A. Multivesicular release at single functional synaptic sites in cerebellar stellate and basket cells. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:4532–4547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04532.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger C, Marty A. Quantal currents at single-site central synapses. The Journal of Physiology. 2000;526:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzini G, De Curtis M, Panzica F, Spreafico R. Intrinsic properties of nucleus reticularis thalami neurones of the rat studied in vitro. The Journal of Physiology (London) 1989;416:111–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avramescu S, Timofeev I. Synaptic strength modulation following cortical trauma: A role in epileptogenesis. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:6760–6772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0643-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CH, Giustetto M, Huang YY, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Is heterosynaptic modulation essential for stabilizing Hebbian plasticity and memory? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2000;1:11–20. doi: 10.1038/35036191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AP, Thomson AM. Dynamic properties of excitatory synaptic connections involving layer 4 pyramidal cells in adult rat and cat neocortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:2190–2203. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi A, Szente MB, Woody CD. Properties of associative long-lasting potentiation induced by cellular conditioning in the motor cortex of conscious cats. Neuroscience. 1991;42:321–334. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I. Thalamocortical oscillations. 2006 http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Thalamocortical_Oscillations.

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I. Intrinsic and synaptic mechanisms of cortical active states generation during slow-wave sleep. In: Timofeev I, editor. Mechanisms of spontaneous active states in the neocortex. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2007. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Cellular and network models for intrathalamic augmenting responses during 10-Hz stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998a;79:2730–2748. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Computational models of thalamocortical augmenting responses. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998b;18:6444–6465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06444.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Model of thalamocortical slow-wave sleep oscillations and transitions to activated states. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:8691–8704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, Abraham WC. Long-term depression in hippocampus. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:437–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becherer U, Moser T, Stuhmer W, Oheim M. Calcium regulates exocytosis at the level of single vesicles. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:846–853. doi: 10.1038/nn1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdudnaya T, Cano M, Bereshpolova Y, Stoelzel CR, Alonso JM, Swadlow HA. Thalamic burst mode and inattention in the awake LGNd. Neuron. 2006;49:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtoli B, Ulrich D. Firing mode-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:4935–4940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0795-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. The Journal of Physiology. 1973;232:331–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg-Graham LJ, Monier C, Fregnac Y. Visual input evokes transient and strong shunting inhibition in visual cortical neurons. Nature. 1998;393:369–373. doi: 10.1038/30735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brémaud A, West DC, Thomson AM. Binomial parameters differ across neocortical layers and with different classes of connections in adult rat and cat neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14134–14139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl EH, Tamãs G, Szilãgyi T, Stricker C, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Effect, number and location of synapses made by single pyramidal cells onto aspiny inter-neurones of cat visual cortex. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:689–713. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto E, Galvan EJ, Card JP, Barrionuevo G. Coincidence detection of convergent perforant path and mossy fibre inputs by CA3 interneurons. The Journal of Physiology. 2008;586:2695–2712. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA, Connors BW. Cellular mechanisms of the augmenting response: Short-term plasticity in a thalamocortical pathway. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996a;16:7742–7756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07742.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA, Connors BW. Short-term plasticity of a thalamocortical pathway dynamically modulated by behavioral state. Science. 1996b;272:274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA, Connors BW. Spatiotemporal properties of short-term plasticity in sensorimotor thalamocortical pathways of the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996c;16:2767–2779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02767.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvette S, Volgushev M, Mukovski M, Timofeev I. Local origin and long-range synchrony of active state in neocortex during slow oscillation. In: Timofeev I, editor. Mechanisms of spontaneous active states in the neocortex. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2007. pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvette S, Volgushev M, Timofeev I. Origin of active states in local neocortical networks during slow sleep oscillation. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20:2660–2674. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse Y, Crochet S, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Synaptic enhancement induced through callosal pathways in cat association cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:3221–3232. doi: 10.1152/jn.00537.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compte A, Reig R, Descalzo VF, Harvey MA, Puccini GD, Sanchez-Vives MV. Spontaneous high-frequency (10–80 Hz) oscillations during up states in the cerebral cortex in vitro. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:13828–13844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2684-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compte A, Sanchez-Vives MV, McCormick DA, Wang X-J. Cellular and network mechanisms of slow oscillatory activity (<1 Hz) and wave propagations in a cortical network model. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89:2707–2725. doi: 10.1152/jn.00845.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinople CM, Bruno RM. Effects and mechanisms of wakefulness on local cortical networks. Neuron. 2011;69:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Dossi RC, Steriade M. Electro-physiological properties of cat reticular thalamic neurones in vivo. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:273–294. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Steriade M. Cellular basis of EEG slow rhythms: A study of dynamic corticothalamic relationships. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:604–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00604.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Mechanisms of long-lasting hyperpolarizations underlying slow sleep oscillations in cat corticothalamic networks. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:251–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg BG. The density of synapses and neurones in the motor and visual areas of the cerebral cortex. Journal of Anatomy. 1967;101:639–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Chauvette S, Boucetta S, Timofeev I. Modulation of synaptic transmission in neocortex by network activities. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21:1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Fuentealba P, Cisse Y, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Synaptic plasticity in local cortical network in vivo and its modulation by the level of neuronal activity. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:618–631. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Fuentealba P, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Selective amplification of neocortical neuronal output by fast prepotentials in vivo. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:1110–1121. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Petersen CC. Correlating whisker behavior with membrane potential in barrel cortex of awake mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:608–610. doi: 10.1038/nn1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V, Leresche N. Childhood absence epilepsy: genes, channels, neurons and networks. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrn811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore RH, Turrigiano GG. Long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in LV visual cortical neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:341–348. doi: 10.1152/jn.01059.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defelipe J, Farinas I. The pyramidal neuron of the cerebral cortex: Morphological and chemical characteristics of the synaptic inputs. Progress in Neurobiology. 1992;39:563–607. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisz RA, Prince DA. Frequency-dependent depression of inhibition in guinea-pig neocortex in vitro by GABAB receptor feed-back on GABA release. The Journal of Physiology (London) 1989;412:513–541. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Turrigiano GG. Plasticity in the intrinsic excitability of cortical pyramidal neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:515–520. doi: 10.1038/9165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinner D. Posttraumatic epilepsy. In: Wyllie E, editor. The Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles. Philadelphia: Lea & Fibinger; 1993. pp. 654–658. [Google Scholar]

- Doi A, Mizuno M, Katafuchi T, Furue H, Koga K, Yoshimura M. Slow oscillation of membrane currents mediated by glutamatergic inputs of rat somatosensory cortical neurons: In vivo patch-clamp analysis. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26:2565–2575. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KA. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:419–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringenberg HC, Hamze B, Wilson A, Speechley W, Kuo M-C. Heterosynaptic facilitation of in vivo thalamocortical long-term potentiation in the adult rat visual cortex by acetylcholine. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:839–848. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunin-Barkowski WL, Sirota MG, Lovering AT, Orem JM, Vidruk EH, Beloozerova IN. Precise rhythmicity in activity of neocortical, thalamic and brain stem neurons in behaving cats and rabbits. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;175:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC. The physiology of synapses. Berlin: Springer; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Evarts EV. Spontaneous discharge of single neurons during sleep and waking. Science. 1962;135:726–728. doi: 10.1126/science.135.3505.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty GT, Roberts LS, Connors BW. Sensory experience modifies the short-term dynamics of neo-cortical synapses. Nature. 1999;400:367–371. doi: 10.1038/22553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich F, Bazhenov M, Sejnowski TJ. Pathological effect of homeostatic synaptic scaling on network dynamics in diseases of the cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:1709–1720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4263-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich F, Sejnowski TJ, Bazhenov M. Network bistability mediates spontaneous transitions between normal and pathological brain states. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:10734–10743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1239-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Crochet S, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Synaptic interactions between thalamic and cortical inputs onto cortical neurons in vivo. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;91:1990–1998. doi: 10.1152/jn.01105.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Timofeev I, Bazhenov M, Sejnowski TJ, Steriade M. Membrane bistability in thalamic reticular neurons during spindle oscillations. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93:294–304. doi: 10.1152/jn.00552.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Frequency-dependent synaptic depression and the balance of excitation and inhibition in the neocortex. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:587–594. doi: 10.1038/2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature. 1999;402:72–75. doi: 10.1038/47029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Burst firing induces a rebound of synaptic strength at unitary neocortical synapses. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:621–624. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner R, Wankerl K, Reinsberger C, Zeller D, Classen J. Depression of human corticospinal excitability induced by magnetic theta-burst stimulation: Evidence of rapid polarity-reversing metaplasticity. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2046–2053. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature. 1999;402:75–79. doi: 10.1038/47035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19:679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Efficacy of thalamocortical and intracortical synaptic connections: Quanta, innervation, and reliability. Neuron. 1999;23:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers WR. Epilepsy and other chronic convulsive diseases: Their causes, symptoms & treatment. New York: William Wood & Company; 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, McCormick DA. Chattering cells: Superficial pyramidal neurons contributing to the generation of synchronous oscillations in the visual cortex. Science. 1996;274:109–113. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DS, Houweling AR, Kerr JND. Population imaging of ongoing neuronal activity in the visual cortex of awake rats. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:749–751. doi: 10.1038/nn.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Wang Y, Markram H. Organizing principles for a diversity of GABAergic interneurons and synapses in the neocortex. Science. 2000;287:273–278. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, McCormick DA. Neocortical network activity in vivo is generated through a dynamic balance of excitation and inhibition. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:4535–4545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5297-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanse E, Gustafsson B. Quantal variability at glut-amatergic synapses in area CA1 of the rat neonatal hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:467–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0467i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham NR, Bannister NJ, Read JCA, Fox KD, Hardingham GE, Jack JJB. Extracellular calcium regulates postsynaptic efficacy through group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6337–6345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5128-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Sultan P. Variation in the number, location and size of synaptic vesicles provides an anatomical basis for the nonuniform probability of release at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1387–1395. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00142-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub A, Sachdev RNS, McCormick DA. State changes rapidly modulate cortical neuronal responsiveness. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:9607–9622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2184-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter M, Staiger JF, Sakmann B, Feldmeyer D. Efficient recruitment of layer 2/3 interneurons by layer 4 input in single columns of rat somatosensory cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:8273–8284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5701-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel CM, Hartman KH, Wang XJ, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Multiple forms of short-term plasticity at excitatory synapses in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:3031–3041. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herculano-Houzel S, Collins CE, Wong P, Kaas JH, Lent R. The basic nonuniformity of the cerebral cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12593–12598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805417105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselmann G, Kell CA, Eger E, Kleinschmidt A. Spontaneous local variations in ongoing neural activity bias perceptual decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SL, Tononi G. Modeling sleep and wakeful-ness in the thalamocortical system. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;93:1671–1698. doi: 10.1152/jn.00915.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JA, Alonso JM, Reid RC, Martinez LM. Synaptic integration in striate cortical simple cells. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:9517–9528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09517.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JC, Fourment A, Marc ME. Sleep-related variations of membrane potential in the lateral geniculate body relay neurons of the cat. Brain Research. 1983;259:308–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling AR, Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Grenier F, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Frequency-selective augmenting responses by short-term synaptic depression in cat neocortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;542:599–617. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling A, Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski T. Cortical and thalamic components of augmenting responses: A modeling study. Neurocomputing. 1999;26–27:735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Houweling AR, Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity can explain post-traumatic epileptogenesis in chronically isolated neocortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:834–845. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Luthi A, Palmer MJ, Anderson WW, Benke TA, Collingridge GL. An investigation of the expression mechanism of LTP of AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission at hippocampal CA1 synapses using failures analysis and dendritic recordings. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1399–1410. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs KM, Prince DA. Excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents in a rat model of epileptogenic microgyria. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93:687–696. doi: 10.1152/jn.00288.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Electrophysiological properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones: An in vitro study. The Journal of Physiology. 1984a;349:205–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Ionic basis for electro-responsiveness and oscillatory properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1984b;349:227–247. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Impaired Clextrusion in layer V pyramidal neurons of chronically injured epileptogenic neocortex. Journalof Neurophysiology. 2005;93:2117–2126. doi: 10.1152/jn.00728.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Spencer WA. Electrophysiology of hippocampal neurons II. After-potentials and repetitive firing. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1961;24:243–259. doi: 10.1152/jn.1961.24.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Kayano F. Electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of layer VI pyramidal cells in the cat motor cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:578–591. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. The release of neuronal transmitter substances. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. The Journal of Physiology. 1968;195:481–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilman V, Van Rossum MC, Turrigiano GG. Activity deprivation reduces miniature IPSC amplitude by decreasing the number of postsynaptic GABA(A) receptors clustered at neocortical synapses. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1328–1337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Tsien RW. Synapse-specific adaptations to inactivity in hippocampal circuits achieve homeostatic gain control while dampening network reverberation. Neuron. 2008;58:925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisley MA, Gerstein GL. Trial-to-trial variability and state-dependent modulation of auditory-evoked responses in cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:10451–10460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10451.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollevold T. Immediate and early cerebral seizures after head injuries. Part I. Journal of the Oslo City Hospitals. 1976;26:99–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Lynch G. Induction of synaptic potenti-ation in hippocampus by patterned stimulation involves two events. Science. 1986;232:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.3704635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Research. 1986;368:347–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie KR, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Post-synaptic depolarization scales quantal amplitude in cortical pyramidal neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:RC170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-j0005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy WB, Steward O. Synapses as associative memory elements in the hippocampal formation. Brain Research. 1979;175:233–245. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Zhang X, O'Brien R, Ehlers MD, Huganir RL. Regulation of morphological postsyn-aptic silent synapses in developing hippocampal neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:37–43. doi: 10.1038/4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissin DV, Gomperts SN, Carroll RC, Christine CW, Kalman D, Kitamura M, et al. Activity differentially regulates the surface expression of synaptic AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:7097–7102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber B, Stanford AD, Bulow P, Nguyen T, Rakitin BC, Habeck C, et al. Remediation of sleep-deprivation-induced working memory impairment with fmri-guided transcranial magnetic stimulation. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2077–2085. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon S, Vautrelle N, Pezard L, Slaght SJ, Deniau J-M, Chouvet G, et al. Distinct patterns of striatal medium spiny neuron activity during the natural sleep-wake cycle. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:12587–12595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3987-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Abbott LF, Turrigiano GG, Liu Z, Golowasch J. Memory from the dynamics of intrinsic membrane currents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:13481–13486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margrie TW, Brecht M, Sakmann B. In vivo, low-resistance, whole-cell recordings from neurons in the anaesthetized and awake mammalian brain. Pflügers Archiv. 2002;444:491–498. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0831-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H. A network of tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons. Cerebral Cortex. 1997;7:523–533. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Lubke J, Frotscher M, Roth A, Sakmann B. Physiology and anatomy of synaptic connections between thick tufted pyramidal neurones in the developing rat neocortex. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:409–440. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Wang Y, Tsodyks M. Differential signaling via the same axon of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:5323–5328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini M, Amzica F. Extracellular calcium fluctuations and intracellular potentials in the cortex during the slow sleep oscillation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:1346–1350. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini M, Ferrarelli F, Esser SK, Riedner BA, Huber R, Murphy M, et al. Triggering sleep slow waves by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8496–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702495104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Connors BW, Lighthall JW, Prince DA. Comparative electrophysiology of pyramidal and sparsely spiny stellate neurons of the neocortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985;54:782–806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]