Abstract

The exchange of substances between higher organisms and the environment occurs across transporting epithelia whose basic features are tight junctions (TJs) that seal the intercellular space, and polarity, which enables cells to transport substances vectorially. In a previous study, we demonstrated that 10 nM ouabain modulates TJs, and we now show that it controls polarity as well. We gauge polarity through the development of a cilium at the apical domain of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK, epithelial dog kidney). Ouabain accelerates ciliogenesis in an ERK1/2-dependent manner. Claudin-2, a molecule responsible for the Na+ and H2O permeability of the TJs, is also present at the cilium, as it colocalizes and coprecipitates with acetylated α-tubulin. Ouabain modulates claudin-2 localization at the cilium through ERK1/2. Comparing wild-type and ouabain-resistant MDCK cells, we show that ouabain acts through Na+,K+-ATPase. Taken together, our previous and present results support the possibility that ouabain constitutes a hormone that modulates the transporting epithelial phenotype, thereby playing a crucial role in metazoan life.

Keywords: E-cadherin, occludin, cell adhesion, cardiotonic steroids

The high affinity and specificity of Na+,K+-ATPase for the plant-derived inhibitor ouabain suggested the possibility that there might exist endogenous analogs. Hamlyn et al. (1) demonstrated that there is a substance in plasma that cannot yet be distinguished from ouabain, even by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry, 1H-NMR, and liquid chromatography (2–4). Furthermore, the observation that this endogenous ouabain and its analogs increase during exercise (5), salty meals (6), and pathological conditions [such as arterial hypertension, eclampsia (7), and myocardial infarction (8)] raised the possibility that it may function as a hormone (9). This theory prompted efforts to unravel its physiological role (10). The present work stems from our previous observations that toxic levels of ouabain invariably affect cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesion molecules in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (11), suggesting that low-dose ouabain may be able to modulate cell contacts without causing irreversible damage (12). In keeping with such possibility, we have previously shown that ouabain promotes cell-cell contacts as well as contact-dependent phenomena, such as increases in cell communication, the expression of connexin-32 (13), and the molecular structure and hermeticity of the tight junction (TJ). This process occurs by regulating the specific expression and distribution of claudin-1, -2, and -4 (12) during differentiation toward the so-called “epithelial transporting phenotype.”

Pursuing our exploration of the effect of low-dose ouabain on cell contacts, we now study whether 10 nM ouabain can modulate polarity, one of the two basic cell features of the transepithelial transporting phenotype (14, 15). We gauge polarity through the expression of a single cilium at the center of the apical domain, a process that relays on the polarized delivery of many proteins to this apical compartment (16, 17). At 10 nM, ouabain causes none of its well-known toxic effects; it does not inhibit the unidirectional transport of K+ by Na+,K+-ATPase nor distorts the K+ balance of the cell, and it does not cause cell death (12, 18).

Results

Ouabain Accelerates Ciliogenesis.

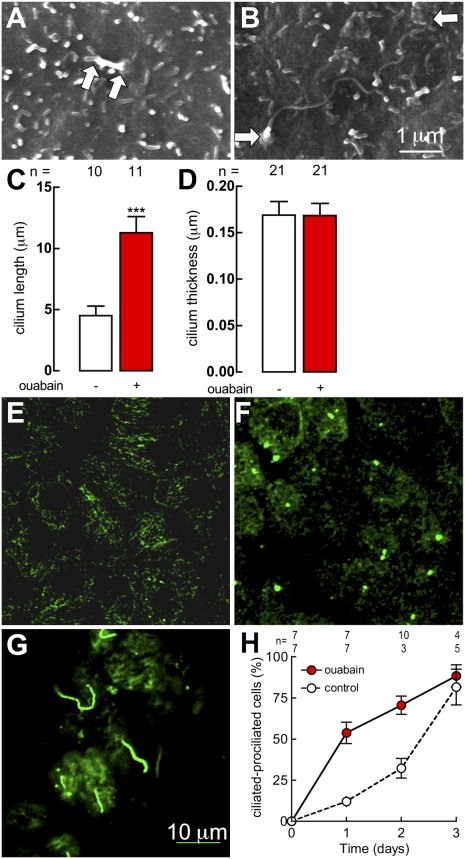

MDCK cells display procilia some 12 h after reaching confluence (Fig. 1A). Procilia progressively lengthen until they become mature cilia. At the third day almost all cells have a cilium (Fig. 1B). Ouabain increases the length of the cilium (Fig. 1C) but not its thickness (Fig. 1D). We also followed ciliogenesis by staining the cells with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin and counting the number of cells at stages without cilium (Fig. 1E), with procilium (Fig. 1F), and with a mature cilium (Fig. 1G). Fig. 1H summarizes the progressive increase in the percentage of prociliated and ciliated cells that tend to reach 100% (open circles). Ouabain accelerates the kinetics of procilia and cilia formation (Fig. 1H, red filled circles), an effect that reaches a 400% increase at 24 h.

Fig. 1.

Ouabain, at a concentration of 10 nM, accelerates ciliogenesis. Scanning electron micrographs of a cilium (between arrows) in a monolayer that has been confluent for 12 h (A), or 3 d (B) under control conditions. Cilia length (C) and thickness (D) as measured in scanning electron microscopy micrographs of wild-type MDCK cells, under control (white bars) or 24 h of ouabain treatment (red bars); ***P < 0.001. Monolayers of MDCK cells stained with antiacetylated α-tubulin at zero (E), 24 h (F), or 72 h (G) in confluence. Ciliogenesis as observed in confluent monolayers under control (open circles) and ouabain (red circles) treatment as a function of time (H).

Role of Homo- and Heterotypic Cell-Cell Contacts.

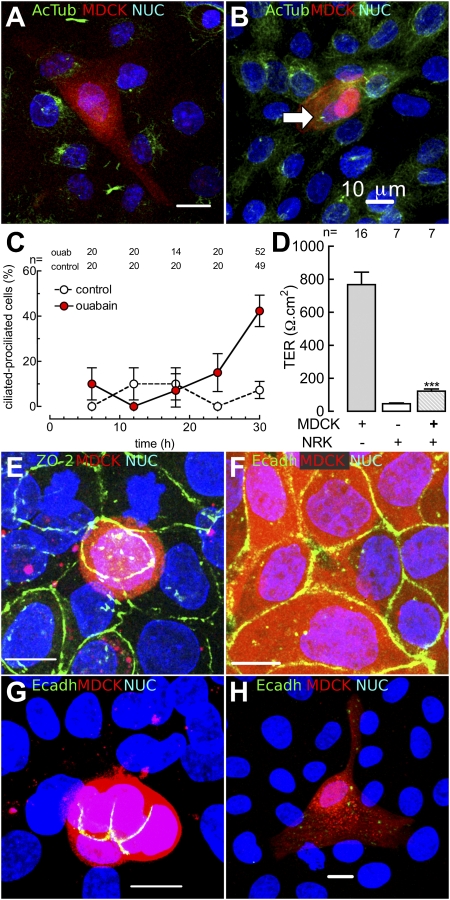

To study the role of cell-cell contacts on the effect played by ouabain on ciliogenesis, we plated cells at confluency, in mixed populations of 1% MDCK and 99% NRK cells (epithelial rat kidney). Under this condition, most single MDCK cells (Fig. 2A, red) surrounded by NRK cells do not exhibit a cilium (Fig. 2 A and C). Nevertheless, ouabain is able to stimulate cilliogenesis even in these MDCK cells totally surrounded by NRK cells (Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

Ciliogenesis in proliferation-arrested MDCK cells does not depend on homotypic cell contacts. Stable red color MDCK cells were produced by transfection of red fluorescent protein. To produce MDCK cells with arrested proliferation, we plated them at confluence in a 1/99 ratio with NRK cells. Forty-two hours later cells were fixed and stained with the indicated antibodies (green) and to detect nucleus with DAPI (blue, NUC). The figure shows a single MDCK completely surrounded by NRK cells, under control condition (A), and treated with 10 nM ouabain for the last 30 h (B). The cilium is stained with a primary antibody against antiacetylated α-tubulin (Ac Tub) and a fluoresceinated secondary one (green). Statistical analysis of single MDCK cells, either under control (open circles) or ouabain treatment conditions (red circles) (C). Establishment of tight junctions as revealed by the value of TER (D) in monolayers of pure MDCK cells (first column), pure ouabain-resistant NRK cells (second column), and a 50/50 mixture of both cell types (third column) cultured for 48 h; ***P < 0.001. In mixed monolayers of MDCK (red) and NRK cells, the cytoplasmic protein ZO-2 is detected by immunofluorescence (green) (E). Immunodetection of E-cadherin (green) in a monolayer of pure MDCK cells (3 d old) (F), or in mixed monolayers (48 h old) showing a small group (G) or a single (H) MDCK cell surrounded by NRK cells. (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

In keeping with our previous observations (19, 20) that the TJ is a promiscuous structure that can be established by epithelial cells from different organs and even from different animal species, we found that monolayers of mixed MDCK (Fig. 2, red) and NRK cells develop a transepithelial electrical resistance (TER). This parameter is proportional to the TER in the monolayer of a single-cell type and their proportion in the mixture (Fig. 2D). Mixed cells also express ZO-2 at the TJs (Fig. 2E). Nagafuchi et al. (21) showed that the expression of E-cadherin requires that the two neighboring cells belong to the same animal species (homotypic contact). In accordance with this observation, Fig. 2F shows that monolayers of pure MDCK (Fig. 2F, red), as well as small groups of MDCK cells (Fig. 2F, red), express E-cadherin (Fig. 2 F and G, green) at homotypic cell-cell borders. However, this molecule is not observed at heterotypic MDCK/NRK contacts (Fig. 2G). Accordingly, a quiescent single MDCK cell (Fig. 2H) expresses no E-cadherin at its borders. We conclude that TJ sealing and ouabain stimulation of ciliogenesis occur in cells that establish homo- and heterotypic borders, even if these express no E-cadherin at the plasma membrane.

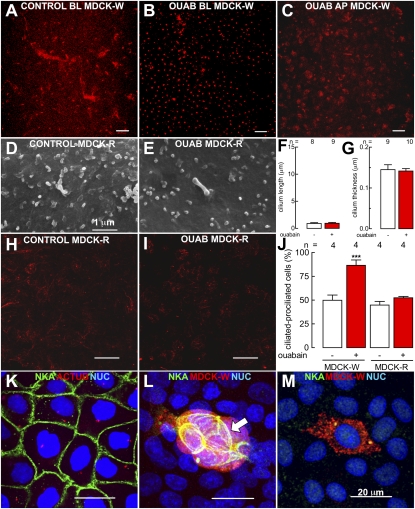

Ouabain and Na+,K+-ATPase.

Ouabain promotes ciliogenesis when added from the basolateral (Fig. 3 A, B, and J, first and second columns) but not from the apical side (Fig. 3C), in accordance with the fact that the Na+,K+-ATPase located at the intercellular cell borders is only accessible from the basal side (20, 22–24). This finding suggests that this enzyme may act as receptor for low concentrations of ouabain acting on cilliogenesis. This possibility was further tested using ouabain-resistant R-MDCK cells, a stable line produced by Soderberg et al. (25) with very low affinity for ouabain. Procilia and cilia in R-MDCK cells are rudimentary (Fig. 3 D and E), and their length (Fig. 3F) and thickness (Fig. 3G), as well as the number of ciliated and prociliated cells (Fig. 3 H, I, and J. third and fourth columns), are not stimulated by ouabain, as observed by scanning electron microscopy and immunodetection of acetylated α-tubulin. Zampar et al. (26) have clearly demonstrated that acetylated α-tubulin binds and inhibits Na+,K+-ATPase in cells of rat brain and COS (monkey kidney fibroblasts), and Menco et al. (27) have found this enzyme in the cilium of olfactory receptor cells. In MDCK cells instead, this enzyme only occupies its well-known specific position at lateral homotypic cell borders (20, 23, 24), and does not colocalize with ciliar acetylated α-tubulin (Fig. 3K). Small groups of MDCK cells expressing red fluorescent protein and surrounded by NRK cells only express Na+,K+-ATPase at homotypic MDCK-MDCK cell borders (Fig. 3L, arrow). When a single MDCK cell is completely surrounded by NRK cells, Na+,K+-ATPase cannot be observed at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3M).

Fig. 3.

Role of Na+,K+-ATPase in the effect of ouabain. Monolayers of wild MDCK cells, under control (A) and 48-h treatment with ouabain (B and C), added from the basolateral (A and B) or the apical side (C). Ouabain-resistant MDCK cells (MDCK-R) display very short cilia (D) that do not become larger (E and F) nor thicker (E and G), nor increase the number of ciliated cells (H vs. I and J) in response to 2 d of incubation with ouabain. Cilia were stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin. Statistical analysis of ciliogenesis in wild-type MDCK cells under control (J, first column) and ouabain (J, second column). Third and fourth columns indicate that ouabain-resistant MDCK cells do not increase the number of ciliated cells when treated with ouabain for 48 h (J); ***P < 0.001. In a 4-d old monolayer of pure MDCK cells (the last 3 d at confluence), Na+,K+-ATPase (green) is localized at all cell borders, and it was never observed at the cilium (red) (K). In 1.5-d mixed monolayers of MDCK (red) with NRK (unstained), the enzyme is only observed at homotypic MDCK-MDCK borders (L, arrow). In keeping with this observation, a single MDCK cell does not express the protein because all its borders contact NRK cells (M). (Scale bars, 20 μm, except for D and E, which are 1 μm.)

Cell Signaling.

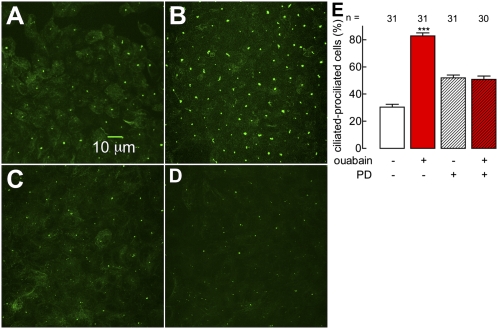

Na+,K+-ATPase forms a receptor complex by associating with signaling molecules, such as c-Src and IP3-receptor, which in turn may activate other proteins, such as ERK1/2. These associations may be modulated by ouabain (28, 29). In previous work, we observed that 10 nM ouabain increases the cell content of claudin-1 and -4 through ERK1/2, and c-Src participates in the regulation of claudin-1 but not -4 (12). This finding suggests that in principle ERK1/2 may play a significant role in ouabain-modulated ciliogenesis. Fig. 4A shows that under control conditions, there are only a few ciliated cells, as observed with an antiacetylated α-tubulin antibody, and 10 nM ouabain enhances this number (Fig. 4 B and E, first two columns). Twenty-five micromolars of PD98059 (PD), a known inhibitor of ERK1/2, is able to promote ciliogenesis by itself (Fig. 4 C and E, third column), yet it clearly prevents a full effect of ouabain (Fig. 4 D and E, fourth column). These results indicate that ouabain regulates the localization of acetylated α-tubulin at the cilium although ERK1/2.

Fig. 4.

Ouabain induces ciliogenesis through ERK1/2. Cilia stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin in a control (A) and a monolayer treated with ouabain for 48 h (B). Results corresponding to experiments similar to A and B, but in the presence of PD (25 μM), an inhibitor of ERK1/2 (C and D). Statistical analysis of the percentage of ciliated cells under control, ouabain-stimulated, control with PD, and ouabain treatment conditions in the presence of PD (columns 1–4) (E); ***P < 0.001.

Claudin-2 as a Ciliary Protein.

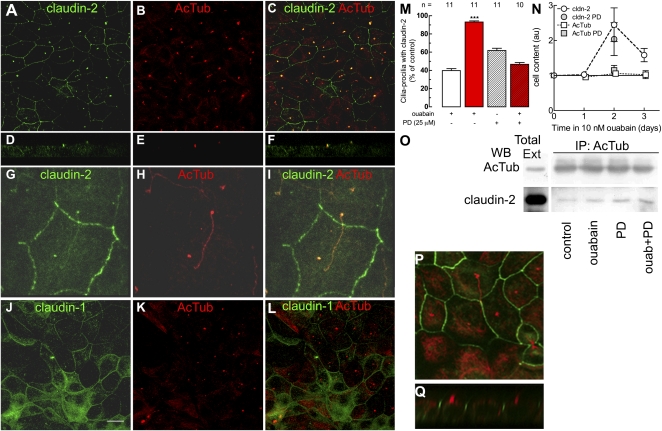

Larre et al. (12) showed that 10 nM ouabain modulates the amount and distribution pattern of claudin-1, -2, and -4. The staining of claudin-2 and -1 in green (Fig. 5 A, D, G, and J) and acetylated α-tubulin in red (Fig. 5 B, E, H, and K) indicates that claudin-2 is present at the cilium. Claudin-2 and acetylated α-tubulin are observed to colocalize in transversal optical section (Fig. 5 D, E, and F), as well as x/y projections (Fig. 5 G, H, and I). Colocalization occurs along the whole cilium; this is specific for claudin-2, as claudin-4 cannot be observed (Fig. 5 J, K, and L). Claudin-4 and occludin cannot be observed at the cilium either (Fig. S1). Ouabain increases ciliary claudin-2 (Fig. 5M, first two columns), and PD inhibits this effect (Fig. 5M, fourth vs. third columns), indicating that ouabain induces the delivery of claudin-2 to the cilium through ERK1/2. Ouabain does not modify the content of acetylated α-tubulin (Fig. 5N, open squares), but it does increase the synthesis of claudin-2, as first observed by Larre et al. (12) (Fig. 5N, open circles). Fig. 5N (gray circles) shows that this last effect does not require the activation of ERK1/2. Claudin-2 is associated to acetylated α-tubulin, as both coimmunoprecipitate with acetylated α-tubulin antibodies (Fig. 5O, lane 2). Ouabain increases the extent of this association (Fig. 5O, lane 3). This association does not depend on ERK1/2, as PD does not block it (Fig. 5O, lanes 4 and 5). Interestingly, PD by itself elicits a similar effect as ouabain. This coimmunoprecipitation of acetylated α-tubulin and claudin-2 further demonstrates that this TJ molecule is also a ciliary protein. Ciliary claudin-2 is not necessary for ciliogenesis, as different clones of MDCK cells that do not express this protein develop normal cilia (Fig. 5 P and Q).

Fig. 5.

Claudin-2, besides of being a typical TJ protein, is also a ciliary protein that is affected by ouabain via ERK1/2 signaling. Immunofluorescence pictures of monolayers incubated with ouabain for 48 h to stain claudin-2 (A, D, and G, green) and -1 (J, green) and acetylated α-tubulin (B, E, H, and K, red). C, F, I, and L correspond to the superposition of the corresponding images. D, E, and F are lateral views of monolayer showing claudin-2 at the cilium. (G, H, and I) x/y projections showing that claudin-2 and acetylated α-tubulin colocalize along the whole cilium at the apical domain. Statistical analysis of the percentage of cells with ciliar claudin-2 observed in images of immunofluorescent cells costained with antibodies against this protein and acetylated α-tubulin, under control, ouabain-stimulated, control with PD, and ouabain treatment in the presence of PD (columns 1–4) (M); ***P < 0.001. Total cell content of acetylated α-tubulin (N, open squares) and claudin-2 (N, open circles). The correspondent effect of PD is shown in gray circles for claudin-2 and gray squares for acetylated α-tubulin. To gain information on the association between acetylated α-tubulin and claudin-2, we coprecipitated the first and blotted for the second (O). Lane 1 corresponds to total homogenate (Total Ext), and the lanes 2–5 depict immunoprecipitation with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin (IP: AcTub), blotted with an antibody against the same acetylated α-tubulin (WB: AcTub) or claudin-2 (WB: claudin-2). Ouabain effect is shown in the lane 3 (ouabain). Lane 4 shows the effect of PD. Interestingly, this inhibitor increases by itself the association. The effect of ouabain does not depend on ERK1/2 as PD does not block the effect (lane 5). Claudin-2 (green) in a MDCK clone that does not express this protein in the cilia, identified as usual with fluorescent red label, in a x/y (P) and z/x image (Q). Ciliary claudin-2 is not required for the development of the cilium. (Magnification: A–F and J –L, 400×; G and H, 1,200×; P and Q, 600×.) (Scale bar in J, 10μm.)

Discussion

At 10 nM, ouabain does not produce its well-known toxic effects, such as the inhibition of K+ and Na+ pumping, cell detachment from its neighbors, and substrate or cell death (12, 13, 18, 20, 30, 31). Nevertheless, at this concentration, oubain modulates the sealing of TJs by changing the cell content and localization of different claudins through specific mechanisms. In the present work, we also observe that 10 nM ouabain accelerates ciliogenesis, as well as increases the length of the cilium. Ouabain accelerates the expression of acetylated α-tubulin at the cilium, yet it does not change its cell content. This molecule also increases the total cell content of claudin-2, as well as its localization at the cilium, and promotes the association between these proteins. Cilium disassembly operates usually at a constant rate in different species and conditions (16), therefore ouabain may accelerate the polarized traffic to provide building blocks to the growing cilium, as well as the anterograde transport.

We demonstrated that ouabain requires the lateral ouabain-sensitive Na+,K+-ATPase to modulate the sealing of TJs (32). To test if Na+,K+-ATPase is the receptor occupied by ouabain to accelerate ciliogenesis, we used resistant (R)-MDCK cells (25), whose resistance to ouabain results from a substitution of a cysteine by tyrosine or a phenylalanine in the first transmembrane segment of Na+,K+-ATPase (33). R-MDCK cells do not respond to low concentrations of ouabain, a result that strengthens the possibility that Na+,K+-ATPase is the receptor. As in other cellular processes, such as cell proliferation (34), death (35), and TJ sealing (12), ouabain modulates the ciliary localization of acetylated α-tubulin although ERK1/2.

Chrystallographic analysis shows that there is a single ouabain binding site per α-subunit (36), supporting the possibility that despite being extremely different, toxic and hormone-like effects are triggered by binding to the same site of in the α-subunit. In classic pharmacology, “intrinsic efficacy” is viewed as a constant for each ligand at a given receptor, irrespective of where the receptor is expressed. This concept is somewhat insufficient to provide a useful theoretic framework for the multitude of ligand-receptors known today. For this reason, Urban et al. (37) proposed that ligands induce unique ligand-receptor conformations that frequently result in the differential activation of signal-transduction pathways, and coined the term “functional selectivity.” In this respect, the present work provides evidence that the interaction of ouabain with Na+,K+-ATPase at the same receptor site, results in several drastically different cell responses. The situation is further complicated by several additional facts: (i) the expression of Na+,K+-ATPase at the cell membrane depends on the interaction of two receptors present in neighboring cells that anchor each other in such a position (22, 23); (ii) the overall effect (e.g., vectorial Na+ transport) requires that at least two cells collaborate (e.g., in the making of a TJ); and (iii) the variety of responses is further compounded by the fact that the enzyme can be assembled by at least four different α- and three different β-isoforms, which have different sensitivities to ouabain. The reasons why a given isoform predominates in certain tissues remain to be elucidated.

The exposure of Na+-K+-ATPase at a given cell border depends on the homotypic interaction between two identical β-subunits of Na+-K+-ATPases (22, 23). Failure to observe the expression of this enzyme at heterotypic borders may not be because of its absence, but because of the fact that it only dwells briefly at the plasma membrane. In this respect, we have previously observed that subconfluent cells and confluent MDCK cells incubated in media without Ca2+ express up to a third of the Na+-K+-ATPases population at the membrane, according to the 3H-ouabain binding method (38). We have also made a similar observation with the Shaker ion channel molecule in which we had deleted the retention domain: the deletion does not impair the correct polarized expression of the channel, but results in transient dwelling (39). However, a brief exposure of Na+-K+-ATPase to 10 nM ouabain is sufficient to trigger ciliogenesis in single MDCK cells completely surrounded by NRK cells.

We observed that claudin-2, a typical molecular component of the TJ, localizes also at the cilium, and that this expression is specific, as neither claudin-1 nor -4, nor occludin were detected (Fig. 5 and Fig. S1). These results show that the expression of claudins at the cilium is not restricted to the human retinal pigment epithelium, as previously suggested (40). Nevertheless, here we show that ciliary claudin-2 is not necessary for ciliogenesis. Septin forms a diffusion barrier that restricts the passage of large molecules toward and away from the cilium (41), with a limit around 10 kDa (17). This barrier may prevent ciliary claudin-2 from diffusing toward the rest of the apical domain. Yu et al. (42) and Muto et al. (43) observed that claudin-2 has the ability to form pores in the TJs where the side-chain carboxyl group of aspartate-65 forms a site that specifically favors the passage of Na+ ions. However, given that the cilium does not separate the two liquid compartments, it is highly unlikely that ciliary claudin-2 would play a role in permeation. However, if claudin-2 contains a Na+-sensitive site, it may possibly bind to this ion in a concentration-dependent manner and act as a sensor of Na+ concentration in the lumen of the nephron. This sensing role of cilia would be consistent with its participation in olfaction and photoreception. Furthermore, cilia are connected to a series of other mechanisms, such as signaling routes (44). In this respect, we observed that the effect of ouabain is also mediated by ERK1/2.

We have previously showed that 10 nM ouabain modulates cell contacts, such as TJs (12), and communicating junctions (13). Here we demonstrate that 10 nM ouabain also stimulates cell polarity, the other fundamental feature of the transporting epithelial phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Chemicals.

Antibodies against: claudin-1(Cat. no. 51–9000), -2 (Cat. no 51-6100), -4 (Cat. no 32-9400), ZO-2 (Cat. no 71-1400), and occludin (Cat. no 71-1500), as well as secondary HRP-anti mouse (Cat. no 61-6620), HRP-anti rabbit (Cat. no 62-6120), FITC-anti rabbit (Cat. no F2765), TRITC-anti mouse (Cat. no 62-6514), and FITC-goat anti-rat (Cat. no 62-9511) were obtained from Invitrogen. Antiacetylated tubulin was obtained from Sigma (T-7451) and α-subunit Na+,K+-ATPase from Thermo Scientific (MA3-929). Ouabain was obtained from Sigma (O-3125), and inhibitor PD98059 was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem.

Cell Culture, Chemicals, and Antibodies.

MDCK-II cells (canine renal; American Type Culture Collection, CCL-34) were grown at 36.5 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in DMEM (GIBCO-Invitrogen) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin 10,000 U⋅μg⋅mL (In Vitro) and 10% FBS (GIBCO-Invitrogen). This medium will be referred to as CDMEM. Cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA (In Vitro) and plated on glass coverslips contained in 24-well multidishes (Costar 3524) and other supports specified below for each experiment. The medium were cultured at a ∼70% saturating density, maintained for one day in CDMEM, followed by serum starvation (24 h, 1% FCS in CDMEM) and then treatment with or without 10 nM ouabain. NRK cells (rat kidney; American Type Culture Collection CRL 1571) were cultured in the same manner. Monolayers were exposed to PD 1 h before starting the challenge with ouabain.

Ciliogenesis in Mixed Monolayers.

To obtain small groups (1–5 cells) of MDCK cells, suspensions of MDCK cells expressing the red fluorescent protein (see below) were mixed at a ratio of 1:99 with nonstained NRK cells and plated to confluence. These cells were allowed 30 min to attach, and then the medium was changed to medium containing 10% FCS. This medium was replaced 12 h later by medium with 1% CDMEM with or without 10-nM ouabain and cells fixed at different times and stained as described below.

Immunoblot.

Total cell extracts from monolayers in inserts were washed three times with ice-cold PBS with Ca2+ and then incubated at 4 °C for 10 min with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris pH 7.5) for protein extraction. Then cells were centrifuged 10 min at 17,000 × g. The supernatant was recovered and the total protein content was measured by the BCA assay (Pierce), subsequently boiled in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad; Cat. no. 1610737) and resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF sheets (Hybond-P; Amersham Biosciences). These sheets were blocked overnight with 5% BSA. Specific bands were detected with specific antibodies and chemiluminiscence (ECL and Hiperfilm; Amersham). Resolved bands were analyzed with the software Kodak 1D 3.5.4 (Eastman Kodak) and data were processed with GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software).

Immunoprecipation.

After 48 h of 10 nM ouabain treatment, 100 cm2 monolayers were washed with PBS containing 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and scraped into 1,500 μL of RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 30 mM NaF, 40 mMβ-glycerophosphate, 20 mM sodium orthovanadate, 3 mM benzamidine; 0.5% Nonidet Nonidet P-40, and a protease inhibitor mixture from Roche) and lisated with an insuline syringe. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g, 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatants were collected and 5.5 mg of protein were used for the immunoprecipitation. This assay was performed with the exacta Cruz Kit (Cat. no. sc-45053; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) following the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Immunofluorescence.

Monolayers on coverslips were washed three times with ice-cold PBS fixed and permeabilized with methanol for 8 min at −20 °C, washed three times with PBS, blocked 1 h with 0.5% BSA, and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with a specific primary antibody, followed by washes as above, and an incubation with a second antibody against the primary antibody. Monolayers were then rinsed six times with PBS, incubated with a FITC- or TRITC-labeled secondary antibody according to the animal species used (1 h at room temperature), rinsed as indicated before, mounted in Fluorguard (Bio-Rad), and examined by confocal microscopy (SP2 Leica Microsystems). Captured images were processed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and figures constructed with GIMP (GNU image manipulation program).

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

After 24 h of 10 nM ouabain treatment, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in saline buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 3.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Hepes pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37 °C and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Monolayers were gently washed three times with PBS, dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (from 50% to 100%), critical-point dried using a Sandri-780A apparatus (Tousimis), gold-coated with a Desk II Gold sputter-etch unit (Denton Vacuum Inc.), and examined with a Jeol JSM-6510LV scanning electron microscope.

Tansepithelial Electrical Resistance.

Cells were grown on Transwell permeable supports as described by Larre et al. (13).

Cell Transfection to Obtain Permanently Red-Stained MDCK Cell.

MDCK-II (3 × 105 cells/mL, that affords roughly 80–90% confluence) were seeded in 2 mL of growing medium in 35-mm diameter dish 1 d before transfection. Cells were prewashed with Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (GIBCO; 31985–062). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was complexed with unmodified pDsRed2-N1 expression vectors (BD Biosciences Clontech). Plasmid at reagent: DNA ratio of 1.56 μL:3 μg. Complexes were prepared by mixing lipofectamine 2000, 6 μL with 250 μL of Opti- MEM I, followed by the addition of plasmid DNA. The mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature after the addition of the transfection reagent, and another 30 min after addition of DNA. Lipofectamine 2000 complexes with DNA were added in a volume of 0.5 mL per dish. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and the transfection complexes were removed. All transfectants were maintained in antibiotic-free complete medium. The stable cell line was acquired under stress condition with antibiotic G418. The fluorescent cells were viewed with a confocal and Epi-fl microscopy. pDsRed2-N1 was used to express a DsRed2 protein in the MDCK cell line as a transfection marker (red-MDCK). pDsRed2-N1 was amplified and then purified by Wizard Plus Maxipreps DNA Purification System (Promega; A7270).

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 4. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was estimated with a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni's multiple comparison test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). All experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are presented as mean ± SE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Arias for his expert input; E. del Oso, Y. de Lorenz, J. Soriano, E. Estrada, and E. Méndez for technical and administrative aid; S. González (Electron Microscopy Unit, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional) for her competent assistance in studies involving scanning electron microscopy; and R. Bonilla for plasmid manipulations. This work was supported by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Technología and the Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología del DF (México City Research Council).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1102617108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hamlyn JM, et al. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6259–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamura A, et al. On the structure of endogenous ouabain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6654–6659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komiyama Y, et al. Identification of endogenous ouabain in culture supernatant of PC12 cells. J Hypertens. 2001;19:229–236. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider R, et al. Bovine adrenals contain, in addition to ouabain, a second inhibitor of the sodium pump. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:784–792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer N, et al. Ouabain-like compound changes rapidly on physical exercise in humans and dogs: Effects of beta-blockade and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Hypertension. 2005;45:1024–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165024.47728.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Salt intake and depletion increase circulating levels of endogenous ouabain in normal men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R553–R559. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00648.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamlyn JM, et al. A circulating inhibitor of (Na+ + K+)ATPase associated with essential hypertension. Nature. 1982;300:650–652. doi: 10.1038/300650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagrov AYa, et al. Endogenous plasma Na,K-ATPase inhibitory activity and digoxin like immunoreactivity after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1991;25:371–377. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoner W. Endogenous cardiac glycosides, a new class of steroid hormones. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2440–2448. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: Their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C509–C536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00098.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Contreras RG, et al. Ouabain binding to Na+,K+-ATPase relaxes cell attachment and sends a specific signal (NACos) to the nucleus. J Membr Biol. 2004;198:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0670-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larre I, et al. Ouabain modulates epithelial cell tight junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11387–11392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000500107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larre I, et al. Contacts and cooperation between cells depend on the hormone ouabain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10911–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604496103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cereijido M, Contreras RG, Shoshani L. Cell adhesion, polarity, and epithelia in the dawn of metazoans. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1229–1262. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cereijido M, Contreras RG, Shoshani L, Flores-Benitez D, Larre I. Tight junction and polarity interaction in the transporting epithelial phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:770–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa H, Marshall WF. Ciliogenesis: Building the cell's antenna. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrm3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith EF, Rohatgi R. Cilia 2010: The surprise organelle of the decade. Sci Signal. 2011;4:mr1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.4155mr1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pchejetski D, et al. Inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase by ouabain triggers epithelial cell death independently of inversion of the [Na+]i/[K+]i ratio. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González-Mariscal L, Chávez de Ramirez B, Lázaro A, Cereijido M. Establishment of tight junctions between cells from different animal species and different sealing capacities. J Membr Biol. 1989;107:43–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01871082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contreras RG, et al. A novel type of cell-cell cooperation between epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 1995;145:305–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00232722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagafuchi A, Shirayoshi Y, Okazaki K, Yasuda K, Takeichi M. Transformation of cell adhesion properties by exogenously introduced E-cadherin cDNA. Nature. 1987;329:341–343. doi: 10.1038/329341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padilla-Benavides T, et al. The polarized distribution of Na+,K+-ATPase: Role of the interaction between beta subunits. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2217–2225. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoshani L, et al. The polarized expression of Na+,K+-ATPase in epithelia depends on the association between beta-subunits located in neighboring cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1071–1081. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammerton RW, et al. Mechanism for regulating cell surface distribution of Na+,K(+)-ATPase in polarized epithelial cells. Science. 1991;254:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1658934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soderberg K, Rossi B, Lazdunski M, Louvard D. Characterization of ouabain-resistant mutants of a canine kidney cell line, MDCK. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12300–12307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zampar GG, et al. Acetylated tubulin associates with the fifth cytoplasmic domain of Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase: Possible anchorage site of microtubules to the plasma membrane. Biochem J. 2009;422:129–137. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menco BP, et al. Ultrastructural localization of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels and Na+,K(+)-ATPase in the rat's olfactory epithelial surface. Chem Senses. 1998;23:137–149. doi: 10.1093/chemse/23.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aperia A. New roles for an old enzyme: Na,K-ATPase emerges as an interesting drug target. J Intern Med. 2007;261:44–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Z. Molecular mechanisms of Na/K-ATPase-mediated signal transduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;986:497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Contreras RG, Shoshani L, Flores-Maldonado C, Lázaro A, Cereijido M. Relationship between Na(+),K(+)-ATPase and cell attachment. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4223–4232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akimova OA, et al. Cardiotonic steroids differentially affect intracellular Na+ and [Na+]i/[K+]i-independent signaling in C7-MDCK cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:832–839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larre I, Cereijido M. Na,K-ATPase is the putative membrane receptor of hormone ouabain. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:625–628. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.6.13498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canessa CM, Horisberger JD, Louvard D, Rossier BC. Mutation of a cysteine in the first transmembrane segment of Na,K-ATPase alpha subunit confers ouabain resistance. EMBO J. 1992;11:1681–1687. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian J, et al. Changes in sodium pump expression dictate the effects of ouabain on cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14921–14929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808355200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aizman O, Uhlén P, Lal M, Brismar H, Aperia A. Ouabain, a steroid hormone that signals with slow calcium oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13420–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221315298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogawa H, Shinoda T, Cornelius F, Toyoshima C. Crystal structure of the sodium-potassium pump (Na+,K+-ATPase) with bound potassium and ouabain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13742–13747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907054106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Urban JD, et al. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoshani L, Contreras RG. In: Biogenesis of Epithelial Polarity and the Tight Junctions. Tight Junctions. Cereijido M, Anderson JM, editors. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreno J, Cruz-Vera LR, García-Villegas MR, Cereijido M. Polarized expression of Shaker channels in epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 2002;190:175–187. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishiyama K, Sakaguchi H, Hu JG, Bok D, Hollyfield JG. Claudin localization in cilia of the retinal pigment epithelium. Anat Rec. 2002;267:196–203. doi: 10.1002/ar.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Q, et al. A septin diffusion barrier at the base of the primary cilium maintains ciliary membrane protein distribution. Science. 2010;329:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1191054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu AS, Kanzawa SA, Usorov A, Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Peters DJ. Tight junction composition is altered in the epithelium of polycystic kidneys. J Pathol. 2008;216:120–128. doi: 10.1002/path.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muto S, et al. Claudin-2-deficient mice are defective in the leaky and cation-selective paracellular permeability properties of renal proximal tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8011–8016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912901107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerdes JM, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. 2009;137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.