Abstract

Several studies indicate that screening in combination with lifestyle modification may produce a greater reduction in colorectal cancer rates than screening alone. To identify national opportunities for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer, we assessed the prevalence of modifiable lifestyle risk factors in the United States. We used nationally representative, cross-sectional data from 5 NHANES cycles (1999–2000, n=2753; 2001–2002, n=3169; 2003–2004, n=2872; 2005–2006, n=2993; 2007–2008, n=3438). We evaluated the 5 colorectal cancer risk factors deemed “convincing“ by the World Cancer Research Fund (obesity, physical inactivity, intake of red meat, processed meat, alcohol), and cigarette smoking, a “suggestive” risk factor in the Surgeon General’s report. We estimated the prevalence of each risk factor separately and jointly, and report it overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity, age, and year. In 2007–2008, 81% percent of US adults, aged 20–69, had at least one modifiable risk factor for colorectal cancer. Over 15% of those younger than 50 years had 3 or more risk factors. There was no change in the prevalence of risk factors between 1999 and 2008. The most common risk factors were risk factors for other chronic diseases. Our findings provide additional support for the prioritization of preventive services in healthcare reform. Increasing awareness, especially among young adults, that lifestyle factors influence colorectal cancer risk, as well as other chronic diseases, may encourage lifestyle changes and adherence to screening guidelines. Complementary approaches of screening and lifestyle modification will likely provide the greatest reduction of colorectal cancer.

Introduction

The vision of the recently released National Prevention Strategy is to move “…the nation from a focus on sickness and disease to one based on prevention and wellness (1).” Colorectal cancer, which cost an estimated 14 billion dollars in 2010, and accounted for approximately 11% of the total cost of cancer care (2), is a focus of health care reform. The prevailing strategy to address colorectal cancer has been through secondary prevention. Screening average risk adults 50 years and older has accounted for a large proportion of an overall decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality over the past three decades (3). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 will increase access to colorectal cancer screening (4), and screening rates will be a key indicator of the prevention strategy (1). While the benefit of screening is clear, there is also extensive evidence to support increased efforts for primary prevention through lifestyle modification.

In the Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, it was estimated that increased screening in combination with a significant, but achievable, improvement in lifestyle risk factor prevalence from the rates in 2000 could reduce colorectal cancer mortality by as much as 50% in 2020 (3). In addition, estimates from a large cohort of women found that while endoscopic screening can significantly reduce risk of colorectal cancer, the magnitude of the risk reduction is less than the reduction for lifestyle and dietary changes alone (5). In a cohort of men, it was estimated that as much as 71% of colon cancer risk could be avoided through modification of a constellation of lifestyle factors (6). Collectively, this evidence suggests that the most successful national strategy for colorectal cancer prevention will include complementary approaches of both screening and lifestyle modification.

Further, in stark contrast to overall incidence, colorectal cancer incidence among adults under 50 years, and below the recommended screening age, has increased since the early-1990s (3, 7). This may be due, in part, to increases in the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors (7). The current screening practice for average risk adults will not address colorectal cancer in this age range; and there is not an evidence-base to support population-wide screening in those younger than 50 (8). It is undetermined whether the healthcare system currently has the capacity to provide quality screening even to those 50 and over (9). Thus, primary prevention of colorectal cancer through lifestyle modification may be the most effective strategy among younger adults.

To identify national opportunities for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer, and prioritize targets for prevention by sex, race/ethnicity, and age, we assessed the prevalence of modifiable lifestyle risk factors in the United States. We evaluated the prevalence the five “convincing“ risk factors as determined by the World Cancer Research Fund (i.e., obesity, physical inactivity, and intake of red meat, processed meat and alcohol) (10), as well as cigarette smoking, which was classified a suggestive risk factor in the Surgeon General’s report (11), and has been consistently associated with colorectal cancer risk in prospective studies (12).

Methods

Study Population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, is a nationally representative survey that uses a multistage stratified, clustered probability sample of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population. Data is collected through household interviews and in-person examinations at mobile examine centers. We estimated the national prevalence of colorectal cancer risk factors in five of the 2-year survey cycles (1999–2000, n=4880; 2001–2002, n=5411; 2003–2004, n=5041; 2005–2006, n=4979; 2007–2008, n=5935). We evaluated non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic black (NHB), and Mexican-American (MA) men and non-pregnant women, aged 20–69 years.

Risk Factors

We evaluated six colorectal cancer risk factors; obesity, physical inactivity, and intake of red meat, processed meat and alcohol, and cigarette smoking. During the household interview, participants were asked about physical activity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol use. During the examination, height and weight were measured, and a 24-hour food recall was administered. All factors of interest, except physical activity, were identically measured in each cycle.

We calculated body mass index (BMI, (weight, kg)/(height, m2)) from height and weight measured at the examination. When height and weight were missing (≤1.1% in all cycles), we used self-reported values from the interview. Participants with a BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2 were classified as obese.

Red meat and processed meat intakes were assessed using a 24-hour recall. One day of 24-hour diet recall was collected until 2003–2004, when two days of recalls were collected. To be consistent, we used the first day 24-hour recall in this study. Daily intake of items containing red meat (i.e., beef, lamb and veal; USDA codes: 21, 23, 2711, 2713, 2721, 2723, 2731, 2733, 2741, 2743, 2751, 2761, 2811, 2813), were summed.(13) Participants who consumed ≥2 oz were classified as regular red meat consumers. Daily intake of items containing processed meat (e.g., frankfurters, sausages, lunchmeats or meat spreads; USDA codes: 252, 2756), were summed (13). Participants who consumed ≥2 oz were classified as regular processed meat consumers.

Participants were asked about their cigarette smoking status and usual alcohol intake. We classified smoking in two ways: ever and current. Because smoking is thought to influence colorectal cancer risk after decades, rather than immediately (12, 14), we classified participants who smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime as “ever” smokers. However, because only current smoking behavior can be modified, we also classified participants who smoked cigarettes on “most” or “some” days as “current” smokers. We classified participants who consumed ≥2 alcoholic beverages on most days as regular alcohol consumers.

Participants were asked about their physical activity behaviors. From 1999–2006, physical activity was uniformly measured. Participants were asked to indicate (1) whether they walked/bicycled for transportation, (2) whether they took part in household/yard tasks requiring at least moderate effort, (3) all of their recreational activities, and (4) the number of minutes and days they spent doing all (transportation, household, and recreational) activities. Participants were asked to describe their “usual daily activities” as one of the following: “sit during day and do not walk very much”, “stand or walk about quite a lot during day but do not have to carry or lift things very often”, “lift or carry light loads, or have to climb stairs or hills often” or “do heavy work or carry heavy loads”. In the 2007–2008 cycle, the physical activity questionnaire was changed. As in the previous cycles, participants were asked whether they walked/bicycled for transportation, and the number of minutes and days they spent walking/bicycling. Participants also reported whether they took part in moderate or vigorous “work” activities (household and occupational activities), and the number of minutes and days they spent doing “work” activities. Rather than reporting all recreational activities, participants reported whether they took part in moderate or vigorous recreational activities, and the number of minutes and days they spent doing recreational activities. For all NHANES cycles, we summed the total minutes of moderate and vigorous activities per week. Then, using the 2007–2008 physical activity recommendations (15), we classified participants who completed ≥150 minutes of moderate or ≥75 minutes of vigorous activity each week as physically active. Because occupational activity minutes were not collected from 1999–2006, participants that selected “do heavy work or carry heavy loads” to describe their usual day were also classified as physically active.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SUDAAN 9.0 (Research Triangle Park, NC) and SAS v.9.1 (Cary, NC). Sampling weights of the smallest sub-sample (i.e., 24-hour food recall) were applied to account for the NHANES sampling design, including over-sampling, non-response, and post-stratification. The analyses included participants with complete information on all risk factors of interest (1999–2000, n=2753, 84.2% of eligible; 2001–2002, n=3169, 85.6% of eligible; 2003–2004, n=2872, 84.1% of eligible; 2005–2006, n=2993, 85.9% of eligible; 2007–2008, n=3438, 87.2% of eligible).

For each NHANES cycle, we estimated the prevalence of each risk factor (obesity, physical inactivity, ever and current smoking, and red meat, processed meat and alcohol intake) separately. The total number of risk factors was calculated by summing the six risk factors; current smoking, rather than ever, was used in the total. We compared differences in the prevalence of the risk factors and the total number of risk factors by sex, race/ethnicity and age using the chi-square test. Because these factors often co-occur, we also estimated the joint distribution of the six modifiable risk factors in 2007–2008. Of the 64 possible risk factor combinations (“risk profiles”), we report the 10 most common ones in the overall study population and in sub-populations defined by sex, race/ethnicity and age. Within each population, at least 60% of the participants had one of the 10 risk profiles. Given our objective to prioritize today’s colorectal cancer prevention efforts, we focus the results on the most recent (2007–2008) NHANES cycle and describe changes in prevalence of the risk factors over time.

Results

The study population was the estimated US adult population 20 to 69 years of age, which was comprised of 52.0% women, 77.4% non-Hispanic whites, 12.8% non-Hispanic blacks and 9.8% Mexican Americans. When divided into age categories, 29.8% were 20–34 years, 34.6% were 35–49 years, and 35.6% were 50–69 years.

Prevalence of colorectal cancer risk factors

2007–2008

Ever smoking was the most common risk factor overall (Table 1). Men were more likely to be both ever and current smokers than women. Non-Hispanic whites were most likely to be ever smokers. Non-Hispanic blacks were most likely to be current smokers (p=0.08). While ever smoking was most prevalent among the oldest age group (50–69 years), current smoking was most prevalent among the youngest age group (20–34 years).

Table 1.

US prevalence of colorectal cancer risk factors in adults aged 20–69 years overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity and age, NHANES 2007–2008a

| Risk Factorb | Overall % (SE) (n=3438) |

Sex % (SE) |

Race/Ethnicity % (SE) |

Age (years) % (SE) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=1733) |

Female (n=1705) |

p-value | NHW (n=1758) |

NHB (n=897) |

MA (n=783) |

p-value | 20–34 (n=944) |

35–49 (n=1087) |

50–69 (n=1407) |

p-value | ||

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||||||

| Ever | 48.97 (2.06) |

55.75 (2.30) |

42.73 (2.31) |

<0.01 | 51.10 (2.32) |

44.32 (2.22) |

38.29 (2.73) |

<0.01 | 46.02 (3.80) |

46.06 (2.62) |

55.28 (1.76) |

0.03 |

| Current | 26.19 (1.91) |

29.20 (1.97) |

23.42 (2.13) |

<0.01 | 26.11 (2.34) |

31.92 (2.51) |

19.37 (2.52) |

0.08 | 33.81 (2.81) |

26.84 (2.89) |

19.17 (1.51) |

<0.01 |

| Obesity | 35.61 (1.11) |

33.92 (1.29) |

36.25 (1.52) |

<0.01 | 33.54 (1.53) |

44.56 (2.39) |

40.32 (3.09) |

0.01 | 28.91 (2.27) |

36.16 (1.74) |

40.70 (2.92) |

<0.01 |

| Physical inactivity | 33.60 (1.78) |

26.75 (1.54) |

39.92 (2.07) |

<0.01 | 31.38 (2.28) |

45.20 (3.35) |

36.02 (3.73) |

0.02 | 25.50 (2.43) |

34.72 (2.21) |

39.31 (3.06) |

<0.01 |

| Intake | ||||||||||||

| Red meat | 30.67 (1.39) |

36.02 (2.16) |

25.75 (1.49) |

<0.01 | 31.25 (1.74) |

27.87 (2.14) |

29.79 (1.80) |

0.60 | 34.65 (1.72) |

29.05 (2.53) |

28.92 (1.73) |

0.01 |

| Processed meat | 14.33 (1.91) |

18.69 (1.14) |

10.31 (1.09) |

<0.01 | 14.11 (1.01) |

18.10 (1.60) |

11.15 (1.34) |

0.08 | 15.77 (1.15) |

14.60 (1.86) |

12.86 (1.57) |

0.47 |

| Alcohol | 8.47 (1.18) |

12.52 (1.40) |

4.73 (1.39) |

<0.01 | 9.28 (1.31) |

6.95 (1.21) |

4.06 (0.98) |

0.01 | 7.25 (1.20) |

8.70 (1.08) |

9.27 (1.95) |

0.37 |

Weighted. NHW: Non-Hispanic white, NHB: Non-Hispanic black, MA: Mexican American. Differences between groups evaluated using the chi-square test.

Ever smoking: >100 lifetime cigarettes smoked; Current smoking: cigarettes smoked on “most” or “some” days; Obesity: ≥ 30 kg/m2; Physical inactivity: < 150 minutes of moderate or < 75 minutes of vigorous activity each week; Red meat intake: ≥ 2 oz total red meat intake in 24-hr recall; Processed meat intake: ≥ 2 oz total processed meat intake in 24-hr recall; Alcohol intake: ≥ 2 drinks on most days.

When considering current smoking rather than ever, obesity was the most common risk factor overall, followed closely by physical inactivity. Women had higher prevalences of obesity and physically inactivity than men; and non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans had higher prevalences of obesity and physical inactivity than non-Hispanic whites. The prevalences of obesity and physical inactivity increased with age.

Among the dietary risk factors, intake of red meat was the most common risk factor, followed by processed meat, and then alcohol. Men were more likely to regularly consume all three dietary risk factors than women. Across race/ethnicity groups, red meat intake was similar, processed meat intake was highest among non-Hispanic blacks, and alcohol intake was highest among non-Hispanic whites. Across age groups, those 20–34 years were most likely to consume red meat, but processed meat and alcohol intake did not differ by age.

Changes over 1999–2008

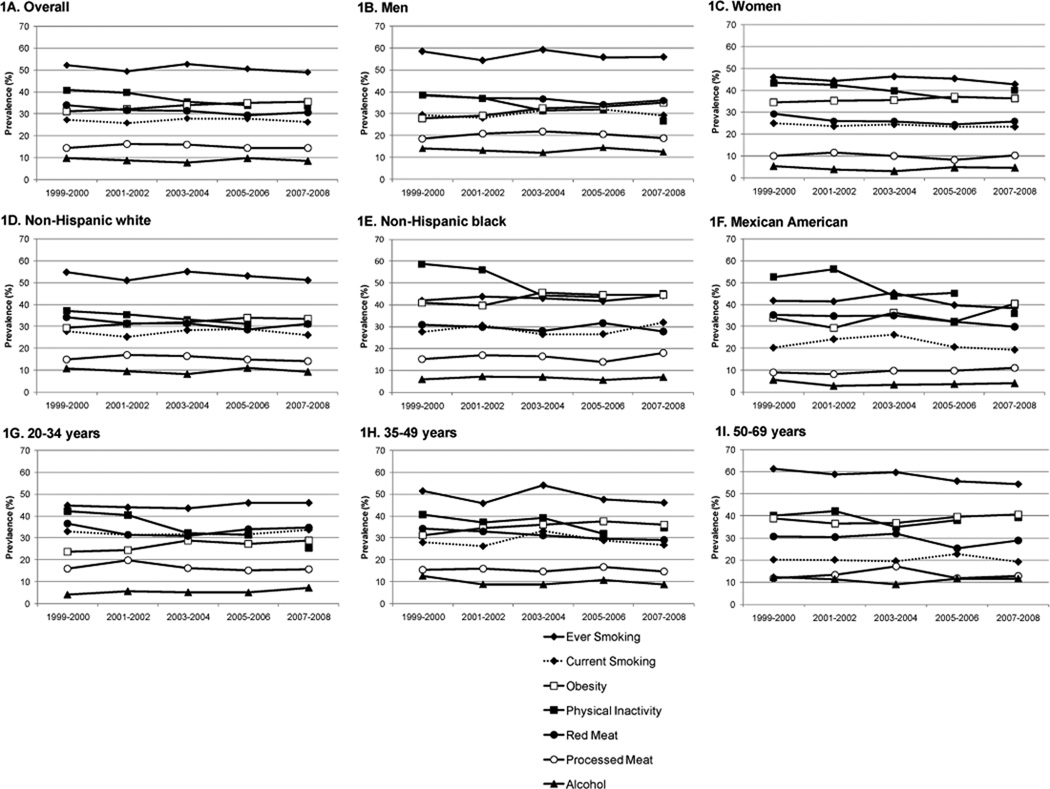

The prevalences remained relatively constant over time in the overall study population and by sex, race/ethnicity and age (Figure 1). Between the 1999 and 2008 survey cycles, the prevalence of obesity increased in the overall study population and within each sub-group. The prevalence of physical inactivity decreased over time in the overall study population and within all sub-groups except those aged 50–69 years; these results are based on physical activity assessments that were not completely consistent over time.

Figure 1.

US prevalence of colorectal cancer risk factors in adults aged 20–69 years overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity and age, NHANES 1999–2008. The measurement of physical activity in NHANES 2007–2008 differed from previous years, therefore the 2007–2006 physical inactivity prevalence estimate is not connected to prior estimates.

Total number of colorectal cancer risk factors

2007–2008

Nineteen percent of the overall population had no risk factors, whereas approximately 64% had 1 or 2 risk factors and 17% had ≥3 risk factors (Table 2). Men had more risk factors than women; approximately 20% of men had ≥3 risk factors as compared to approximately 15% of women (p=0.07). The distribution of number of risk factors differed significantly by race/ethnicity and age groups: non-Hispanic blacks had the highest prevalence of ≥3 risk factors (~23%), followed by non-Hispanic whites (~16%), and Mexican Americans (~13%). The prevalence of ≥3 risk factors increased slightly with age (20–34, ~16%; 30–49, ~17%; 50–69, ~18%).

Table 2.

US prevalence of total number of colorectal cancer risk factors overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity and age, NHANES 2007–2008a

| Total number of colorectal cancer risk factors, % (SE) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4+ | p-value | |

| Overall | 18.76 (1.74) |

34.17 (1.20) |

30.03 (1.35) |

13.76 (1.30) |

3.28 (0.36) |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 17.33 (2.21) |

31.15 (1.46) |

32.23 (1.79) |

15.06 (1.61) |

4.22 (0.78) |

0.07 |

| Female | 20.07 (1.83) |

36.96 (2.09) |

28.00 (1.84) |

12.57 (1.28) |

2.41 (0.55) |

|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NHW | 19.73 (2.38) |

34.64 (1.50) |

29.13 (1.83) |

13.50 (1.57) |

3.01 (0.54) |

0.03 |

| NHB | 12.77 (1.92) |

29.55 (1.63) |

34.39 (2.18) |

17.34 (2.06) |

5.95 (0.79) |

|

| MA | 18.90 (1.53) |

36.50 (1.74) |

31.49 (1.63) |

11.22 (1.19) |

1.90 (0.92) |

|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–34 | 18.51 (2.48) |

36.72 (2.15) |

28.53 (1.56) |

12.95 (1.46) |

3.29 (0.90) |

≤0.01 |

| 34–49 | 18.97 (2.57) |

33.20 (1.98) |

30.82 (2.07) |

13.10 (2.09) |

3.91 (0.71) |

|

| 50–69 | 18.75 (2.65) |

32.98 (1.91) |

30.51 (2.58) |

15.10 (1.11) |

2.66 (0.50) |

|

Weighted. NHW: Non-Hispanic white, NHB: Non-Hispanic black, MA: Mexican American. Differences between groups evaluated using the chi-square test.

Changes over 1999–2008

These patterns were similar across all 5 NHANES cycles in the overall population and by sex, race/ethnicity, and age (Supplemental Table 1). The prevalence of ≥3 risk factors was consistent across cycles. However, in earlier cycles, the prevalence of having no risk factors was lower, and the prevalence of one risk factor was higher, than in later cycles, particularly in men, non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans. This difference was likely due to the corresponding change in the prevalence of physical inactivity, which was most pronounced in these same subgroups.

Colorectal cancer risk factor profiles

2007–2008

Because these risk factors often co-occur, we also identified the most common risk factor profiles. Among those with ≥1 risk factor, the top 3 most common risk profiles were obesity only, physical inactivity only, and both obesity and physical inactivity; these were also the most common profiles among women, non-Hispanic blacks, Mexican Americans and those 50–69 years (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2). Similarly, the top profiles among non-Hispanic whites and those 35–49 years old included obesity and physical activity, but also current smoking. Among men and young adults, the top three risk profiles were obesity only, red meat intake only (or their combination), and current smoking.

Discussion

We found that there are many opportunities for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer in the United States. In 2007–2008, 81% percent of US adults, aged 20–69, had at least one modifiable risk factor for colorectal cancer. In the Annual Report to the Nation, it was estimated that screening, in combination with a considerable reduction in the 2000 prevalence of lifestyle risk factors could have a significant impact on colorectal cancer mortality (3). Yet, we observed no notable improvement in the prevalence of a subset of those risk factors in the decade between 1999 and 2008. The combination of sub-optimal screening rates and a steady prevalence of lifestyle risk factors suggests that colorectal cancer rates will not decrease to the extent possible in the near future. The most prevalent modifiable risk factors for colorectal cancer, like obesity, are not novel; these are the same risk factors as for other chronic diseases, like diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Our findings do not signify a need for specialized colorectal cancer lifestyle interventions, but they do provide additional evidence for the need for the early intervention and targeted prevention and wellness services to be developed as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (4).

In the clinical setting, the guidelines for colorectal cancer prevention focus on screening the average risk adult at age 50 (16). However, our data indicate that the conversation about colorectal cancer risk and prevention needs to start much earlier. We observed that more than 15% of those younger than 50, and thus, not recommended for screening, had 3 or more risk factors. In contrast to overall rates, colorectal cancer incidence has increased in those younger than 50 (7). Alerting younger adults about their colorectal cancer risk based on lifestyle factors provides an opportunity for change. Awareness of personal risk due to lifestyle risk factors may also increase awareness of the importance of adherence to screening guidelines at the appropriate age. Indeed, a growing body of evidence supports the benefit of simultaneously addressing multiple health behaviors in healthcare settings (17–19). Because colorectal cancer screening is a complex behavior (20); more research is needed to determine whether increased awareness of lifestyle risk factors among young adults would influence future screening behavior.

Our findings also show that the population sub-groups with the highest burden of colorectal incidence and mortality also have the greatest opportunity for primary prevention through lifestyle modification. The total burden of colorectal cancer risk factors mirrored colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates by sex and race/ethnicity. Men had a higher total number of risk factors than women; men also have higher colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates than women (21). Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest total number of risk factors among the race and ethnicity groups; and African Americans have the highest colorectal cancer incidence and mortality (21). Providing access to resources that encourage appropriate lifestyle changes, as well as increasing access to screening, may improve colorectal cancer rates in those with the highest burden.

We used nationally representative data to estimate the separate and joint prevalences of risk factors, overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity, and age over a 10-year period. The data were cross-sectional; individuals were not followed over time or for colorectal cancer outcomes. The prevalence of current smoking that we estimated in NHANES 2007–2008 was higher than that reported in the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (22); our estimate is for a narrower age range (20–69 years versus 18+). We were unable to fully evaluate physical inactivity time trends because its assessment was changed in the 2007–2008 NHANES survey relative to the 1999–2006 surveys. In addition, the 1999–2006 surveys incompletely assessed occupational activity, an activity type that may differ across sex, race/ethnicity, age and time. Red meat and processed meat intakes were evaluated using the current state-of-art, one-day, 24-hour diet recall, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Automated Multiple Pass Method (23). We used a single 24-hour diet recall because multiple days were not available for two of the five NHANES cycles evaluated. While multiple days of 24-hour diet recall are needed to assess individuals’ usual intake, this single 24-hour recall is a robust method to describe the average dietary intake of a group (23).

Improved clinical and community preventive services are a major aspect of the National Prevention Strategy. Colorectal cancer is a disease with many opportunities for prevention. Increasing national screening rates is an important strategy for reducing the burden of colorectal cancer, but it should not be the only strategy. We found that the vast majority American adults have at least one modifiable colorectal cancer risk factor. Further, a sizable proportion of those younger than 50 years have several colorectal cancer risk factors. When advising the public about risks associated with factors like obesity and cigarette smoking, colorectal cancer should be included in the discussion. Increasing the public’s awareness that these factors also impact colorectal cancer risk may enhance efforts to modify lifestyle, and may further encourage adherence to screening guidelines. The most successful national strategy for colorectal cancer prevention will likely include complementary approaches of both screening and lifestyle modification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding: CEJ was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number T32 CA009314) and the Seraph Foundation. GAC is supported by the American Cancer Society (Clinical Research Professorship).

References

- 1.National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council. National Prevention Strategy America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 111th Congress ed. United States: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei EK, Colditz GA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Rosner BA. Cumulative risk of colon cancer up to age 70 years by risk factor status using data from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:863–872. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platz EA, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Giovannucci E. Proportion of colon cancer risk that might be preventable in a cohort of middle-aged US men. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:579–588. doi: 10.1023/a:1008999232442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1695–1698. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klabunde C, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel M. Trends in Colorectal Cancer Test Use among Vulnerable Populations in the U.S. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2406–2415. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 3.0. Beltsville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannucci E. An updated review of the epidemiological evidence that cigarette smoking increases risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:725–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: 2008. Report No.: U0036. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Shah M, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2011: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:8–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN, Taylor WC, Goodrick GK, Moye L. Simultaneous vs sequential counseling for multiple behavior change. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1152–1158. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prochaska JJ, Nigg CR, Spring B, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. The benefits and challenges of multiple health behavior change in research and in practice. Prev Med. 2010;50:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:339–359. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults. United States, 2007. Atlanta, GA: 2008. Nov 14, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson F, Subar A. Dietary Assessment Methodology. In: Coulston A, Boushey C, editors. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.