Abstract

Introduction

Malignant glioma remains a significant therapeutic challenge and immunotherapeutics might be a beneficial approach for these patients. A monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for multiple molecular targets could expand the treatable patient population and the fraction of tumor cells targeted, with potentially increased efficacy. This motivated the generation of MAb D2C7, which recognizes both wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRwt) and a tumor-specific mutant, EGFRvIII.

Methods

D2C7 binding affinity was determined by surface plasmon resonance and its specificity characterized through comparison to EGFRwt-specific EGFR.1 and EGFRvIII-specific L8A4 MAbs by flow cytometry and immunohisochemical analysis. The 3 MAbs were labeled with 125I or 131I using Iodogen, and paired-label internalization assays and biodistribution experiments in athymic mice with human tumor xenografts were performed.

Results

The affinity of D2C7 for EGFRwt and EGFRvIII was 5.2 × 109 M−1 and 3.6 × 109 M−1, and cell-surface reactivity with both receptors was documented by flow cytometry. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed D2C7 reactivity with malignant glioma tissue from 90 of 101 patients. Internalization assays performed on EGFRwt-expressing WTT cells and EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M cells indicated a threefold lower degradation of 125I-labeled D2C7 compared with 131I-labeled EGFR.1. Uptake of 125I-labeled D2C7 in NR6M xenografts (52.45 ∀ 13.97% ID/g on Day 3) was more than twice that of 131I-labeled L8A4; a threefold to fivefold tumor delivery advantage was seen when compared to 131I-labeled EGFR.1 in mice with WTT xenografts.

Conclusions

These results suggest that D2C7 warrants further evaluation for the development of MAb-based therapeutics against cancers expressing EGFRwt and EGFRvIII.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFRvIII, glioblastoma multiforme, monoclonal antibody

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; WHO Astrocytoma Grade IV) is the most common and most malignant primary brain tumor [1]. Despite aggressive treatment with gross total surgical resection, high-dose conformal external beam radiation therapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy, median survival remains around 15 to 18 months, and there are very few long-term survivors [2, 3]. In the last decade, despite the clinical evaluation of a large number of adjuvant therapies, only temozolomide [4, 5] and bevacizumab [6, 7] have been approved by the FDA for treating newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM, respectively. However, these agents are not curative, extending median survival for only a few months, and they produce objective responses in less than half of GBM patients. Recurrence of GBM is almost universal, and therapy at recurrence with agents like bevacizumab or Gliadel extends median survival for only 6 to 9 months. The features of GBM responsible for treatment failure and recurrence include poor drug delivery, the genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity of GBM cells, the widespread migration of neoplastic cells, and cellular resistance mechanisms.

Because of the genetic and cellular heterogeneity of GBM, targeting multiple molecules would probably be required to eradicate all tumor cells, particularly if therapeutics with a short range of action were envisioned. One of the earliest molecular abnormalities recognized in GBM was amplification of the wild-type epidermal growth factor gene (EGFRwt) [8,9] and the most common and novel mutation in the amplified EGFR gene consists of a deletion of exons 2 to 7, resulting in a mutant protein, EGFRvIII [10,11]. EGFRvIII contains a glycine at the fusion junction, forming a tumor-specific epitope against which specific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been raised. EGFRvIII is constitutively activated and promotes proliferation, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis [12]. Moreover, EGFR amplification, mutation, and over expression have been demonstrated to be important mechanisms of altered growth control in GBM [13,14]. Some studies have shown that amplification and expression of EGFRwt or EGFRvIII confer poor prognosis, while others have not confirmed such prognostic significance [9,15-17].

EGFRwt expression is found on epithelial cells in a majority of organs [18], but not in normal brain. Thus, while normal tissue toxicity may limit EGFRwt-targeted anti-tumor therapies in other settings, compartmental administration within the central nervous system could enhance the specificity of tumor treatment. EGFRvIII is an even more desirable target because it is tumor specific and is associated with those tumors presenting the most aggressive biological characteristics. Despite the importance of EGFRwt and EGFRvIII as major mechanisms of altered growth control in GBM, monotherapy with EGFR signal transduction inhibitors has been ineffective in multiple clinical trials, likely because of the complexity, redundancy and multiplicity of signaling pathways [19]. The relative lack of clinical efficacy of EGFRwt small molecule kinase inhibitors has provided motivation for developing other EGFR-directed strategies for GBM therapy, notably MAb-based approaches.

Numerous anti-EGFRwt and anti-EGFRvIII MAbs have been developed [20,21]. Some of the former have been studied in clinical trials for patients with a variety of EGFRwt-expressing cancers, including gliomas, with unremarkable results [21-26]. Trials in GBM patients with radiolabeled anti-EGFRwt MAbs (9A, 425, EGFR.1) have been reported [27-29] and a Phase II trial with 125I-labeled MAb 425 demonstrated an increase in median survival [30]. A small Phase I trial has been conducted using 806 MAb, which recognizes mutant EGFRvIII and an activated conformation of EGFRwt [31]. We have developed several murine MAbs against EGFRvIII including L8A4 [32-33] and demonstrated anti-tumor efficacy in brain tumor models [34-36]. MR1-1, an EGFRvIII targeted dsFv-PE38KDEL single fragment chain Pseudomonas exotoxin construct, has entered clinical trial in GBM patients [37].

The use of a MAb “cocktail” containing multiple MAbs might address the limitation imposed by variations in antigen expression within a tumor cell population by increasing the proportion of targetable tumor cells, or by increasing the target density on given cells. However, each MAb in the cocktail must be individually prepared, characterized, and tested for all aspects of its clinical utility, individually and in the context of each of the other MAbs, thus multiplying the complexity of preparing such a cocktail several fold. Moreover, regulatory agencies would likely require investigational permits and Phase I-III clinical trials with each MAb before allowing combined therapy to be evaluated.

In the current study, we sought to determine whether the same goal of multiple targeting could be achieved by developing a single MAb that recognizes two proteins important in the GBM oncogenic genotype. In particular, we describe the in vitro and in vivo characterization of D2C7, a novel MAb that binds both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII, two of the most prevalent molecular signatures of GBM.

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were of reagent grade or higher quality and were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Sodium [131I]iodide and sodium [125I]iodide were obtained from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-EGFR (wild type) MAb EGFR.1 (IgG2b) specific for the EGFRwt extracellular domain was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-EGFRvIII MAb L8A4, developed in our lab, has been described previously [36].

2.2. Cell lines and xenografts

NR6 is the NIH 3T3 murine fibroblast parent of the NS1-derived transfectants NR6W (transfected with the EGFR wild type gene) and NR6M (transfected with the mutant EGFRvIII gene) [37]. WTT is a designation for the U87MG cell line that has been transfected to over express wild type EGFR [38]. These cells were cultured as previously described [39] and xenograft propagation is described below.

2.3. Hybridoma generation, antibody purification

In order to develop a MAb with affinity for both EGFRvIII-expressing cells and EGFRwt-expressing cells, we immunized BALB/C mice with a combination of microsomal membranes prepared from NR6M cells and EGFRvIII PEP3, a 14-mer peptide (LEEKKGNYVVTDHC) corresponding to the amino acid sequence at the EGFRvIII fusion junction [11]. Primary immunization was with microsomal membranes equivalent to 107 cells plus 100 μg of PEP3 in complete Freud’s adjuvant given subcutaneously. On day 67, mice were boosted subcutaneously with 100 μg of PEP3 in 0.2 ml of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant containing 1 mg of S. minnesota per milliliter. On days 82 and 176, mice were injected i.p. with microsomal membranes equivalent to 5 × 106 cells and 100 μg PEP3 in PBS. On day 193, mice were injected with microsomal membranes equivalent to 5 × 106 cells i.p. in PBS, and 4 days later their spleens were harvested and fused to Kearney variant (P3x63Ag8.653) mouse myeloma cells. Hybridomas were screened against soluble 1% Triton X-100 target extracts prepared from A431 cells (EGFRwt) and NR6M cells by capture ELISA. D2C7 MAb was positive in both screens and reacted with PEP3 and EGFR extracellular domain on viable cells as tested in flow cytometry. The hybridoma was then cloned three times and the isotype determined to be IgG1K. D2C7 MAb was purified from ascites fluid as described [40,41].

2.4. Affinity assessment of D2C7

The binding kinetics and affinity of D2C7 for EGFRwt and EGFRvIII, and of L8A4 for EGFRvIII were determined by surface plasmon resonance (Biacore 3000, Piscataway, NJ) against bacterially-expressed recombinant EGFRwt extracellular domain (ECD) and EGFRvIII ECD. Each MAb was assayed at five different concentrations (25, 50, 100, 150 and 200 nM) against immobilized targeted epitopes at a flow rate of 30 μl/min in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA and 0.005 % p20 surfactant at pH 7.4). Global curve fitting was used to determine association and dissociation rate constants by BIAevaluation Software.

2.5. Flow-cytometric specificity analysis of D2C7

For flow cytometric analysis of D2C7, L8A4, and EGFR.1 MAb cell surface binding specificity, NR6, NR6W, and NR6M cells were harvested (2 × 105/test), washed, and blocked with 10% FCS. MAbs P588, murine IgG1, and M45.6, murine IgG2b, were used as isotype-matched controls. After washing, the cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS), for 20 min. Live cells were incubated with each MAb for 1 h on ice, washed twice, and incubated with anti-mouse IgG-FITC-conjugated antibody (1:5000, Invitrogen) for 1 h on ice. Finally, cells were suspended in PBS and freshly analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACSort flow cytometer with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

2.6. Immunohistochemical analysis

2.6.1. Patient characteristics

Immunohistochemistry was performed on GBM patient tissue microarrays prepared by the Brain Tumor Tissue Biorepository at the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center, Duke University Medical Center. The mean ages of the nonamplified (n=51) and amplified (n=50) patient cohorts were 53.7 years and 57.9 years, respectively. The majority was male (55%), as noted in other studies [42-44], and 86% of the patients had primary GBM.

2.6.2. Frozen tissue immunohistochemistry

A Ventana Discovery XT Automated System (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tuscon, AZ) with DAB Map kit was used to test the snap-frozen tissue utilizing an optimized protocol. Briefly, frozen tissue sections were thawed at room temperature (RT) for 20 min and then loaded onto the system. EGFR.1, L8A4, and D2C7 MAbs at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml in antibody diluent (Dako) were incubated at RT for 60 min. MAbs were visualized by addition of anti-mouse/anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody (Ventana) at RT for 20 min followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate. Treated slides were incubated with DAB substrate and then counterstained with hematoxylin (Ventana) and Bluing Reagent (Ventana) for 4 min. After counterstaining, slides were dipped into Dawn detergent (Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH) for 2 min according to the manufacturer’s instructions, rinsed with water, initially dehydrated in 95% (v/v) ethanol followed by 100% (v/v) ethanol, and finally, 100% (v/v) xylene. Sections were mounted with cover slips for observation. During each run, known EGFR-negative normal brain tissues were run as negative controls. Concentration- and isotype-matched MAbs (mouse IgG1 and IgG2b, Invitrogen) were also run as controls.

2.6.3. Histopathology and scoring

The histologic sections were scored for immunohistochemical intensity by a neuropathologist (AFB) using the criteria described for evaluating HER2 expression in breast cancer [45], where scores indicate the following: 0, no staining; 1+, weak reactivity in #10% of cells; 2+, weak to moderate reactivity in >10% of cells; and 3+, strong reactivity in ∃30% of cells. The specimens were reviewed in random order, and the neuropathologist was blinded with respect to IHC antibody treatment, tissue type, and patient record. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize EGFR amplification status and scoring.

2.7. Radiolabeling of MAbs D2C7, EGFR.1, L8A4 and P588

For use in in vitro internalization assays and in vivo biodistribution experiments, D2C7, EGFR.1, L8A4 and P588 were labeled with 125I or 131I using a previously described variation of the Iodogen method [46]. Radiolabeled MAbs were purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Sephadex G-25 column. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitability of the labeled proteins was ≥ 99%.

2.8. In vitro internalization assays

Radiolabeled MAb internalization assays were performed against two separate target cell lines. In the first experiment, 125I-labeled D2C7 and 131I-labeled EGFR.1 were incubated with EGFRwt-expressing WTT cells at 4°C for 1 h (MAb excess, 2.5 mg per 1 × 106 cells). Unbound MAb was removed by washing with cold 1% BSA/PBS and cells were resuspended in Zinc Option culture medium containing 10% FBS at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. 500 μl aliquots were incubated at 37°C for 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 24 h. Following aliquot centrifugation, the supernatant was removed for counting and the cell pellet was washed with FBS adjusted to pH 2.0 with HCl. After recentrifugation, an LKB 1282 dual-channel automated gamma-counter (LKB, Wallac, Finland) was utilized for determination of the amount of radioactivity located within the cells (cell pellet), on the cell surface (acid wash), or remaining in the cell culture supernatant. The supernatant was precipitated with 12.5% TCA to determine the fraction of radioactivity that was protein associated. In the second experiment, a similar protocol was followed on NR6M cells incubated with 125I-labeled D2C7 and 131I-labeled L8A4. Time points were 0.25, 1, 2 and 24 h.

2.9. Paired-label tissue distribution experiments

Four sets of paired-label biodistribution studies were performed in athymic mice bearing subcutaneous EGFRwt-expressing WTT tumors or EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M tumors. In the first experiment, WTT-bearing animals were injected via the tail vein with 2 μg of 125I-labeled D2C7 (2.8 μCi/μg) and 1 μg of 131I-labeled anti-EGFRwt EGFR.1 (3.9 μCi/μg). Groups of 5 animals were euthanized by halothane overdose at 24, 48, 72 and 144 h following MAb injection. Selected tissues were harvested, weighed and assayed for 125I and 131I activity using the automated gamma-counter. Results were expressed as percentage of the injected dose (% ID) per organ, per gram of tissue, and as tumor-to-tissue ratio. In the second experiment, NR6M-bearing mice were injected with 2 μg of 125I-labeled D2C7 (2.3 μCi/μg) and 2 μg of 131I-labeled anti-EGFRvIII L8A4 (1.8 μCi/μg). At 24, 48, 72, 96 and 168 h, groups of 5 animals were euthanized and treated as described above. In Experiments 3 and 4, animals bearing WTT or NR6M subcutaneous tumors, respectively, were injected with 2 μg of 125I-labeled D2C7 (3.1 μCi/μg) and 2 μg of 131I-labeled P588 (2.3 μCi/μg) (Experiment 3), or 2 μg of 125I-labeled D2C7 (2.5 μCi/μg) and 2 μg of 131I-labeled P588 (2.3 μCi/μg) (Experiment 4). The tissue distribution of radioiodine activity was determined at 12, 24, 48, 72, and either 144 h (Experiment 3) or 168 h (Experiment 4). Tumor localization indices were calculated as the ratio of D2C7 over non-specific P588 MAb in tumor divided by the same ratio in blood. Statistical analyses were performed using a paired t-test with p < 0.05 considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Affinity and specificity of D2C7 for EGFRwt and EGFRvIII

D2C7 affinity for binding to EGFRwt and EGFRvIII ECD was determined by surface plasmon resonance using a BIAcore device. MAb L8A4 was used as a positive control for EGFRvIII binding; EGFR.1 MAb did not react with the targeted EGFRwt molecule despite various epitope production methods. The KA at binding equilibrium, calculated as kassoc / kdiss, was 5.17 × 109 M−1 for D2C7 on EGFRwt, 3.60 × 109 M−1 for D2C7 on EGFRvIII, and 3.10 × 108 M−1 for L8A4 on EGFRvIII (Table 1). No binding of L8A4 to EGFRwt was observed.

Table 1.

Association (ka), dissociation (kd) and affinity constants (KA) for D2C7 and L8A4 MAbs for binding to EGFRwt and EGFRvIII measured by surface plasmon resonance

| Antibody | Epitope | ka (M−1 s−1) | kd (s−1) | KA (M−1) | KD (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2C7 | EGFRwt | 1.50 × 105 | 2.90 × 10−5 | 5.17 × 109 | 1.93 × 10−10 |

| EGFRvIII | 1.25 × 105 | 3.20 × 10−5 | 3.60 × 109 | 2.80 × 10−10 | |

| L8A4 | EGFRvIII | 7.12 × 105 | 2.30 × 10−3 | 3.10 × 108 | 3.22 × 10−9 |

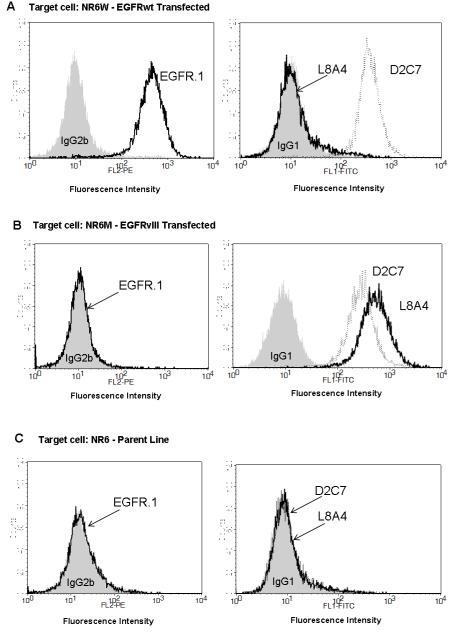

The specificity of D2C7 binding was evaluated by flow cytometry against unfixed EGFRwt-transfected NR6W, EGFRvIII-transfected NR6M, and parental NR6 cells, which lack EGFR expression. These transfected cell lines were used for this purpose because of the singularity of their cell surface EGFR type. Cell surface binding results are shown in Fig. 1 for MAbs D2C7, L8A4, and EGFR.1 and isotype-matched control MAbs. D2C7 was the only MAb that bound to both NR6W and NR6M cells, while L8A4 only bound to NR6M cells. No binding was detected for D2C7, L8A4, or EGFR.1 to parental NR6 cells.

Fig. 1.

Determination of target specificity of MAbs for EGFRwt and EGFRvIII by flow cytometric analysis of EGFRwt-expressing NR6W cells (A), EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M cells (B), and EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-negative NR6 cells (C). Negative control antibody IgG2b (isotype of EGFR.1) or P588 IgG1 (isotype of L8A4 and D2C7) shown as gray-shaded area; compared to EGFRwt-specific EGFR.1 (black trace), EGFRvIII-specific L8A4 (black trace), and D2C7, which binds to both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII (gray trace).

3.2 Immunohistochemical analyses

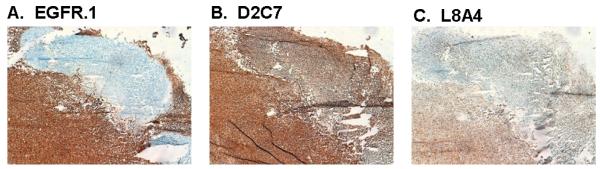

3.2.1. Dual reactivity of D2C7 with EGFR and EGFRvIII in frozen GBM tissue

Positive membrane and cytoplasmic reactivity of GBM tissue by immunohistochemistry (IHC) with EGFR.1, D2C7, and L8A4 is shown in Fig. 2. Comparison of the patterns of IHC reactivity of EGFR.1 (Fig. 2A), D2C7 (Fig. 2B), and L8A4 (Fig. 2C) on an EGFR-amplified patient sample confirmed the ability of D2C7 to react with tumors cells expressing either EGFR and/or EGFRvIII. In the area of tumor that does not react with EGFR.1 (Fig.2A), strong staining was observed with both D2C7 (Fig. 2B) and L8A4 (Fig. 2C), demonstrating the presence of cells expressing EGFRvIII in the absence of wild-type EGFR cell surface protein. D2C7 also reacted with the same tumor region that was positive with EGFR.1, indicating the presence of cells expressing EGFR. The homogeneity of staining within this GBM sample was greater for D2C7 than observed with either of the monospecific MAbs.

Fig.2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of binding of MAbs EGFR.1 (A), D2C7 (B), and L8A4 (C) to GBM tissue. Acetone-fixed frozen sections from patient with EGFRwt amplification stained with 5 μg of each MAb.

3.2.2. EGFR and EGFRvIII expression in EGFR-amplified and nonamplified GBM tissue

EGFR.1, D2C7, and L8A4 reacted positively (IHC score ≥2+) with 91% (92/101), 89% (90/101), and 27% (27/101) of cases, respectively (Table 2). In those cases with EGFR gene amplification identified by FISH (EGFR:7cep ratio), 98% (49/50) and 100% (50/50) scored positive with EGFR.1 and D2C7 MAb, respectively, compared with 42% (21/50) with L8A4. In contrast, 84% (43/51), 78% (40/51), and 12% (6/51) of cases without EGFR amplification had an IHC score ≥2+ in analyses using EGFR.1, D2C7, or L8A4 MAbs, respectively.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry scores for MAb EGFR.1, L8A4 and D2C7 binding to EGFRwt amplified and non-amplified GBM sections

| EGFRwt Amplified % sectionsa |

EGFRwt Non-Amplified % sectionsb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody | Target | 0-1+ | 2+ | 3+ | 0-1+ | 2+ | 3+ |

| EGFR.1 | EGFRwt | 2.0 | 6.0 | 92.0 | 15.7 | 23.5 | 60.8 |

| L8A4 | EGFRvIII | 58.0 | 18.0 | 24.0 | 88.2 | 9.8 | 2.0 |

| D2C7 | EGFRwt/ EGFRvIII |

0 | 8.0 | 92.0 | 21.6 | 39.2 | 39.2 |

n=50

n=51

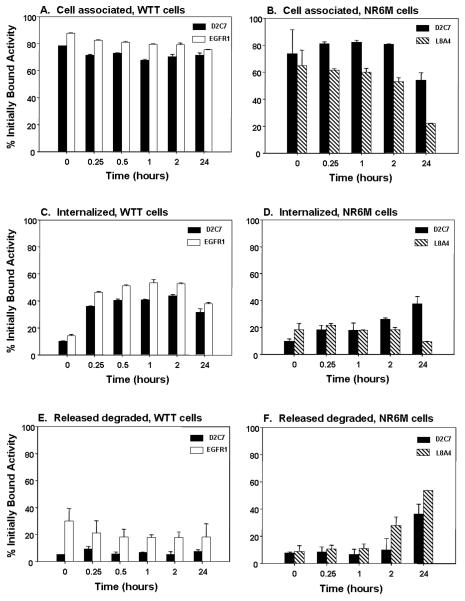

3.3. In vitro internalization and processing of radiolabeled D2C7

The cellular internalization and processing of 125I-labeled D2C7 were compared to those of 131I-labeled EGFR.1 and 131I-labeled L8A4 in paired-label in vitro experiments using EGFRwt-expressing WTT cells and EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M cells, respectively. The percentages of cell-associated (membrane bound + internalized) and internalized radioiodine activity remaining in WTT and NR6M cells are shown in Fig. 3. High percentages of radioiodine activity for both 125I-labeled D2C7 (71-80%) and 131I-labeled EGFR.1 (75-87%) remained cell associated throughout the 24-h observation period. On WTT cells, internalization of 125I-labeled D2C7 and 131I-labeled EGFR.1 occurred rapidly, reaching a plateau over 30 min – 2h at about 40% of initially bound counts for D2C7 and 50% for EGFR.1. Internalized counts for 125I-labeled D2C7 on NR6M cells were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than on WTT but reached a similar value at 24 h (37.2 ∀ 4.4%, NR6M; 31.1 ∀ 4.4%). Significantly higher levels of radioiodine activity from 125I-labeled D2C7 were cell-associated and internalized by NR6M cells compared with co-incubated 131I-labeled L8A4 at most time points. For example, at 24 h, the percentage of radioiodine activity remaining cell associated was 53.9 ∀ 5.6% for D2C7 compared with 21.7 ∀ 1.7% for L8A4.

Fig. 3.

Cell-associated activity, internalization, and processing of radiolabeled MAbs by EGFRwt-expressing WTT cells (left) and EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M cells (right). Shown are the percentages of radioiodine counts initially bound to the cells for 125I-labeled D2C7, 131I-labeled EGFR1, and 125I-labeled D2C7 that are cell associated (membrane + internalized), internalized and released degraded (TCA soluble) into the cell culture supernatant. Bars represent average of triplicate measurements ∀ SD.

The appearance of TCA soluble radioiodine in the cell culture supernatant is an indicator of MAb degradation to low molecular weight catabolites. TCA soluble counts for 125I-labeled D2C7 after incubation with WTT cells were significantly lower than for 131I-labeled EGFR.1 at all time points (Figure 3E). For example, the percentage initially bound activity after a 2-h incubation that was TCA soluble was 5.0 ∀ 1.7% for D2C7 compared with 17.8 ∀ 3.9% for EGFR.1. Likewise, TCA soluble counts for 125I-labeled D2C7 after incubation with NR6M cells were lower than for 131I-labeled L8A4 at all time points (Figure 3F) with the difference being significant beginning at 1 h (P < 0.05). For example, the percentage initially bound activity after a 2-h incubation that was TCA soluble was 9.4 ∀ 7.8% for D2C7 compared with 27.8 ∀ 6.1% for L8A4.

3.4. Paired-Label Biodistribution of D2C7 MAb in EGFRvIII- and EGFRwt-Expressing Xenografts

Two experiments were performed in athymic mice with EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M xenografts to compare the tissue distribution of 125I-labeled D2C7 MAb (IgG1) either to 131I-labeled L8A4, an EGFRvIII-specific IgG1 MAb, or to 131I-labeled P588 control MAb. As summarized in Table 3, tumor uptake of radioiodine activity for D2C7 peaked at 52.45 ∀ 13.97% ID/g on Day 3 and was twofold to threefold higher than that for co-administered L8A4 from Day 1 through Day 4. The mean weight of tumors harvested at necropsy on Days I and 6 was 0.60 ∀ 0.30 g ND 1.65 ∀ 1.33 g, respectively. Activity levels in normal tissues for the two MAbs were comparable except for the thyroid on Days 1 and 2, where significantly lower % ID were observed for D2C7 (P <0.05). Tumor-to-Tissue ratios, shown in parenthesis in Table 3, were uniformly higher for radioiodinated D2C7 compared with L8A4. The specificity of D2C7 uptake in NR6M xenografts was evaluated by direct comparison to isotype-matched P588 control MAb. Tumor localization indices for D2C7 were 3.0 ∀ 1.0, 4.2 ∀ 0.6, 5.9 ∀ 0.9, and 8.2 ∀ 2.2 on Days 1, 2, 3, and 7, respectively.

Table 3.

Paired-label tissue distribution of radioiodine activity in athymic mice bearing subcutaneous EGFRvIIIexpressing NR6M xenografts after intravenous injection of 125I-labeled D2C7 and 131I-labeled L8A4

| % ID/g (T:t)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 7 |

| 125I-D2C7 | |||||

| Liver | 6.46 ± 0.69 (5.83) | 5.09 ± 0.81 (8.45) | 4.67 ± 1.08 (11.29) | 3.62 ± 1.54 (12.72) | 1.35 ± 0.79 (11.47) |

| Spleen | 5.68 ± 0.68 (6.62) | 4.81 ± 0.83 (9.04) | 4.29 ± 0.81 (12.30) | 3.43 ± 1.85 (13.71) | 1.21 ± 0.78 (13.61) |

| Lungs | 7.76 ± 0.95 (4.88) | 6.41 ± 0.53 (6.66) | 7.10 ± 1.96 (7.48) | 5.15 ± 1.09 (8.59) | 1.91 ± 1.60 (9.94) |

| Heart | 6.42 ± 1.05 (6.01) | 5.46 ± 0.80 (7.85) | 5.73 ± 1.48 (9.24) | 4.22 ± 1.19 (10.60) | 1.37 ± 1.20 (13.66) |

| Kidneys | 6.98 ± 0.56 (5.36) | 5.40 ± 0.52 (7.85) | 5.26 ± 1.33 (10.02) | 3.82 ± 1.34 (11.64) | 1.35 ± 1.02 (12.68) |

| Stomach | 1.18 ± 0.17 (31.7) | 1.31 ± 0.12 (33.1) | 1.12 ± 0.23 (50.22) | 0.90 ± 0.31 (50.25) | 0.64 ± 0.20 (23.21) |

| Thyroidb | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 1.21 ± 0.28 | 1.59 ± 0.65 | 1.28 ± 0.31 | 3.57 ± 1.41 |

| Blood | 23.62 ± 2.17 (1.6) | 18.60 ± 1.90 (2.3) | 18.96 ± 4.37 (2.77) | 13.83 ± 4.27 (3.19) | 4.60 ± 3.93 (4.07) |

| Tumor | 37.04 ± 4.21 | 42.65 ± 10.43 | 52.45 ± 13.97 | 45.91 ± 25.30 | 15.43 ± 9.96 |

| Brain | 0.66 ± 0.12 (57.9) | 0.48 ± 0.07 (89.2) | 0.51 ± 0.12 (104.3) | 0.40 ± 0.16 (111.2) | 0.14 ± 0.10 (124.4) |

|

| |||||

| 131I-L8A4 | |||||

| Liver | 6.70 ± 0.73 (2.89) | 5.17 ± 0.94 (4.25) | 4.68 ± 1.13 (4.37) | 3.74 ± 1.67 (3.49) | 1.35 ± 0.79 (9.67) |

| Spleen | 4.79 ± 0.53 (4.03) | 3.83 ± 0.65 (5.70) | 3.39 ± 0.67 (6.06) | 2.83 ± 1.51 (4.70) | 1.00 ± 0.64 (13.3) |

| Lungs | 7.07 ± 0.87 (2.75) | 5.86 ± 0.54 (3.63) | 6.65 ± 1.84 (3.18) | 4.68 ± 1.04 (2.70) | 2.03 ± 1.41 (6.94) |

| Heart | 6.23 ± 1.07 (3.21) | 5.39 ± 0.82 (3.99) | 5.71 ± 1.43 (3.51) | 4.21 ± 1.16 (2.99) | 1.63 ± 1.08 (8.33) |

| Kidneys | 6.55 ± 0.49 (2.29) | 5.04 ± 0.44 (4.23) | 4.95 ± 1.14 (4.13) | 3.62 ± 1.26 (3.46) | 1.45 ± 0.93 (9.35) |

| Stomach | 1.14 ± 0.18 (16.9) | 1.19 ± 0.11 (17.8) | 1.00 ± 0.22 (20.4) | 0.80 ± 0.28 (16.41) | 0.56 ± 0.17 (22.6) |

| Thyroidb | 1.20 ± 0.23 | 1.80 ± 0.36 | 1.88 ± 0.55 | 1.53 ± 0.41 | 3.35 ± 1.09 |

| Blood | 24.07 ± 2.07 (0.8) | 18.99 ± 1.98 (1.1) | 19.72 ± 4.26 (1.03) | 14.34 ± 4.32 (0.87) | 5.71 ± 3.72 (2.38) |

| Tumor | 18.93 ± 3.22 | 21.16 ± 1.27 | 19.29 ± 5.09 | 13.08 ± 7.29 | 12.45 ± 6.50 |

| Brain | 0.66 ± 0.11 (29.6) | 0.48 ± 0.08 (44.6) | 0.52 ± 0.12 (39.32) | 0.41 ± 0.17 (30.98) | 0.16 ± 0.10 (84.2) |

Results are expressed as %ID per gram of tissue or per milliliter of blood with tumor-to-tissue ratios (T:t) given in parentheses.

% ID per organ for thyroid.

In similar fashion, two experiments were performed in athymic mice with EGFRwt-expressing WTT xenografts to compare the tissue distribution of 125I-labeled D2C7 MAb to either 131I-labeled EGFR.1 EGFRwt-specific MAb or 131I-labeled P588 control MAb. As summarized in Table 4, uptake of radioiodine activity in WTT xenografts for D2C7 MAb was highest at Day 1 (30.75 ∀ 3.04% ID/g) and declined thereafter, and was about threefold to fivefold higher than co-administered EGFR.1 MAb. Mean tumor weights determined at necropsy on Days 1 and 7 were 0.08 ∀ 0.04 g and 0.25 ∀ 0.11 g, respectively. Normal tissue levels for the two MAbs were comparable except for in the thyroid on Days 1-3, where significantly lower % ID were observed for radioiodinated D2C7 (D2C7, 2.07 ∀ 0.71% ID; EGFR.1, 5.10 ∀ 1.33% ID; P <0.05). Tumor-to-Tissue ratios, shown in parenthesis in Table 4, were uniformly higher for radioiodinated D2C7 compared with EGFR.1. The specificity of D2C7 uptake in WTT xenografts was evaluated by direct comparison to isotype-matched P588 MAb. Tumor localization indices for D2C7 were 2.4 ∀ 0.2, 3.3 ∀ 0.4, 4.0 ∀ 0.5, 4.1 ∀ 0.8, and 3.8 ∀ 0.3 at 12 h and on Days 1, 2, 3, and 6, respectively.

Table 4.

Paired-label tissue distribution of radioiodine activity in athymic mice bearing subcutaneous EGFRwt-expressing WTT xenografts after intravenous injection of 125I-labeled D2C7 and 131Ilabeled EGFR.1

| % ID/g (T:t)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 6 |

| 125I-D2C7 | ||||

| Liver | 3.97 ± 1.22 (8.17) | 2.53 ± 1.67 (9.37) | 2.14 ± 1.30 (7.46) | 0.84 ± 0.76 (5.59) |

| Spleen | 3.99 ± 1.21 (8.14) | 2.32 ± 1.25 (9.75) | 2.05 ± 1.01 (7.31) | 0.90 ± 0.57 (4.87) |

| Lungs | 5.73 ± 1.35 (5.53) | 2.88 ± 1.62 (7.82) | 2.39 ± 1.71 (7.21) | 0.89 ± 0.93 (5.99) |

| Heart | 4.49 ± 1.53 (7.36) | 2.57 ± 1.30 (8.64) | 1.78 ± 1.18 (9.41) | 0.62 ± 0.68 (8.98) |

| Kidneys | 4.27 ± 1.11 (7.47) | 2.55 ± 1.52 (8.96) | 2.01 ± 1.24 (8.02) | 0.85 ± 0.80 (5.67) |

| Stomach | 3.07 ± 1.12 (12.26) | 2.97 ± 0.68 (7.74) | 2.07 ± 0.27 (7.35) | 0.91 ± 0.48 (4.92) |

| Thyroidb | 2.07 ± 0.71 | 4.32 ± 1.74 | 4.80 ± 1.93 | 6.19 ± 1.43 |

| Blood | 14.66 ± 5.17 (2.24) | 8.19 ± 5.35 (2.89) | 5.55 ± 3.54 (3.05) | 2.21 ± 2.66 (2.67) |

| Tumor | 30.75 ± 3.04 | 20.73 ± 6.56 | 15.76 ± 9.95 | 5.42 ± 5.42 |

| Brain | 0.38 ± 0.14 (87.30) | 0.21 ± 0.11 (106.7)) | 0.19 ± 0.10 (80.98) | 0.07 ± 0.06 (74.10) |

|

| ||||

| 131I-EGFR.1 | ||||

| Liver | 4.02 ± 1.11 (2.37) | 2.12 ± 1.15 (2.58) | 1.55 ± 0.75 (1.97) | 0.58 ± 0.24 (1.89) |

| Spleen | 3.95 ± 1.34 (2.46) | 1.79 ± 1.11 (3.14) | 1.15 ± 0.55 (2.65) | 0.37 ± 0.19 (3.06) |

| Lungs | 5.68 ± 1.12 (1.67) | 2.52 ± 0.84 (2.05) | 1.87 ± 0.90 (1.62) | 0.78 ± 0.30 (1.42) |

| Heart | 4.34 ± 1.13 (2.19) | 2.36 ± 0.62 (2.19) | 1.51 ± 0.56 (1.93) | 0.61 ± 0.17 (1.82) |

| Kidneys | 4.42 ± 0.80 (2.13) | 2.39 ± 0.90 (2.19) | 1.76 ± 0.66 (1.66) | 0.85 ± 0.28 (1.30) |

| Stomach | 3.53 ± 0.85 (2.93) | 2.63 ± 0.55 (2.06) | 1.40 ± 0.34 (2.08) | 0.53 ± 0.15 (2.11) |

| Thyroidb | 5.10 ± 1.33 | 7.11 ± 1.84 | 6.81 ± 1.44 | 6.77 ± 1.05 |

| Blood | 14.32 ± 3.60 (0.66) | 7.37 ± 2.74 (0.71) | 4.75 ± 1.72 (0.61) | 2.11 ± 0.82 (0.52) |

| Tumor | 9.47 ± 2.56 | 5.34 ± 2.54 | 3.01 ± 1.36 | 1.20 ± 0.86 |

| Brain | 0.39 ± 0.11 (24.55) | 0.20 ± 0.06 (25.34) | 0.18 ± 0.04 (16.37) | 0.07 ± 0.03 (15.85) |

Results are expressed as %ID per gram of tissue or per milliliter of blood with tumor-to-tissue ratios (T:t) given in parentheses.

% ID per organ for thyroid.

4. Discussion

The success of immunotherapy is dependent on achieving uniform delivery of the MAb within all tumor regions. This is particularly critical for therapeutic approaches involving toxic agents with a cellular or subcellular range of action such as toxins, photosensitizers and radionuclides emitting short range radiation. Moreover, reasonably homogeneous tumor drug delivery should be achievable in a high fraction of patients with a given tumor type for the therapeutic strategy to be of clinical significance. In the current study, we have evaluated one approach to achieving this goal – the development of a MAb reactive with two well-characterized molecular targets associated with GBM – EGFRwt and EGFRvIII. Our dual immunization and screening protocols yielded MAb D2C7, which was confirmed by flow cytometry to bind specifically to cells transfected to express either receptor. Furthermore, the affinity for D2C7 binding to both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII was >3.5 H 109 M−1, which equals or surpasses the affinity of monospecific L8A4 MAb for EGFRvIII observed in this and previous studies [47,48]. D2C7 also demonstrated an expanded repertoire of immunoreactivity in immunohistochemistry of patient brain tumor samples compared to monospecific MAbs. To validate D2C7 as a dual-specificity reagent, we evaluated 101 patient glioma specimens and showed that D2C7 reacted with 50/50 samples with EGFRwt amplification and 40/51 samples lacking EGFRwt amplification, which compared favorably with both monospecific MAbs, particularly EGFRvIII targeted L8A4. Moreover, as exemplified in Figure 2, the uniformity of MAb staining generally was better than that seen with either monospecific MAb, a property that could help minimize tumor recurrence from subpopulations of receptor-negative tumor cells that might escape treatment if only one GBM associated molecule had been targeted.

To the best of our knowledge, no other MAb with high specificity and affinity for both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII has been reported; however, two have been described as being bispecific for both receptors. MAb 806 binds both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII [49] but recognizes an untethered transitory form of EGFRwt, which is essentially the default conformation for EGFRvIII, as the mutant receptor lacks the CR1 dimerization domain. Moreover, MAb 806 binds only a low percentage of the total available EGFRwt receptor over expressed by A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells and only about half of EGFRvIII expressed by U87MG.ΔEGFR [50]. On the other hand, MAb 806 does not bind EGFRwt on normal tissues, which could be an important advantage. MAb 528 also reacts with both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII extracellular domains [51] in a conformation-dependent manner. The MAb bound with higher intensity to U87 cells co-expressing EGFRwt and EGFRvIII compared to parental lines or EGFRwt over-expressing A431 cells [52] although receptor numbers were not quantified.

An understanding of the fate of a MAb after binding to a cell surface molecular target is important for optimizing its potential as a carrier system for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. For example, MAbs that undergo rapid internalization can be utilized as immunotoxins following chemical or genetic conjugation to polypeptide toxins [53]. In addition, internalizing MAbs might be useful in tandem with low energy Auger electron emitters such as 111In [54] that must localize near the cell nucleus to be effective, which could lead to lower toxicity to non-targeted normal tissues. On the other hand, particularly for receptors undergoing lysosomal translocation, MAb internalization requires the selection of a labeling method - both for radiohalogens and radiometals – that maximizes trapping of the radionuclide in tumor cells after internalization and MAb degradation occur [55].

In the current study, MAbs were labeled using the Iodogen method to facilitate analysis of MAb degradation and the comparison of our results with those in the literature for other bispecific EGFRwt/EGFRvIII MAbs. There was prolonged retention of cell-associated radioiodine activity on the EGFRwt-expressing cell line for EGFR.1 and D2C7 over the 24 h study with about 40% of input counts found in the intracellular compartment for both MAbs after 15 min. The fact that TCA soluble counts in the supernatant were twofold to threefold lower for MAb D2C7 suggests that this MAb is degraded to a lesser extent than EGFR.1. Differences in intrinsic MAb stability that reflect accessibility of iodotyosines to deiodinases and proteases could be a factor. Alternatively, the kinetics and path of intracellular routing for D2C7 after binding to EGFRwt could result in reduced exposure to endosomes and lysosomes compared with EGFR.1. The results for D2C7 incubation with NR6M cells instead of WTT cells yielded several differences: slower internalization kinetics, lower magnitude of cell-associated and internalized activity, and particularly at later time points, higher levels of degraded MAb. However, in the NR6M study, internalized counts for D2C7 were higher than seen for monospecific L8A4 MAb at later time points. The mechanisms for the differential processing of D2C7 by the different cell lines in currently unknown, but may involve the abilities of the cell lines to ubiquitinate and degrade the internalized receptor complexes, particularly in the presence of endogenous EGFR [56].

We next evaluated the ability of MAb D2C7 to localize selectively and specifically in both EGFRwt-expressing WTT and EGFRvIII-expressing NR6M xenograft models. Unlike xenografts derived from human gliomas that express both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII as shown in this study, these transfected lines are useful for demonstrating bispecificity because each expresses only one form of the receptor. In both xenograft models, tumor uptake of radioiodine activity for D2C7 was significantly higher than that of co-administered monospecific EGFR.1 or L8A4 MAb at most times points, with the delivery advantage reaching a factor of about three at the time of maximum tumor uptake (WTT, Day 1; NR6M, Day 3). The superior tumor accumulation of D2C7 relative to L8A4 might have been predicted from the increased cell-associated activity observed for the former in the internalization assays. On the other hand, in the WTT experiments, cell associated activity in vitro for D2C7 was higher than for EGFR.1, with the opposite behavior observed in tumor xenografts in vivo. This again suggests the possibility that the intracellular routing (kinetics, pathway) and resultant catabolism of D2C7 MAb may differ from that of L8A4 or EGFR.1. We have previously reported that L8A4 is rapidly internalized in EGFRvIII-positive cells and translocated to lysosomes [32, 39]. Although the Technical Data Sheet and associated references for EGFR.1 MAb lack information on the fate of this MAb after EGFR binding, other MAbs that target EGFRwt are known to be rapidly translocated to lysosomes after receptor binding [20,21]. Studies are planned to determine the intracellular kinetics of MAb D2C7 on EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-expressing tumor cells, and to determine the epitope(s) involved in MAb binding to these receptors.

The localization indices and tumor-to-tissue ratios measured for D2C7 MAb versus negative control MAb P588 were consistent with specific targeting in both EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-expressing xenografts. In addition, the higher tumor-to-tissue ratios observed for radioiodinated D2C7 in comparison with each co-administered monospecific MAb indicated more selective targeting was achieved with D2C7 in both the WTT and NR6M models. The magnitude and selectivity of D2C7 uptake in EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-expressing tumors in athymic mice compare favorably with the values reported for directly radioiodinated MAbs 806 and 528, which also exhibit binding to both of these receptors [52]. Previous studies have demonstrated that twofold to fivefold higher uptake of radioiodine activity in NR6M as well as other EGFRvIII-expressing xenografts could be achieved with anti-EGFRvIII MAb L8A4 through the use of labeling methods designed to include charged prosthetic groups [57-59]. In order to get a better assessment of the translational potential of D2C7 MAb for radioimaging and targeted radiotherapy, future experiments are planned to determine whether these labeling strategies offer similar enhancements with D2C7 in targeting both EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-expressing tumors including those derived from human GBM.

In summary, we have developed a MAb, D2C7, which binds with high affinity to both EGFRwt and EGFRvIII, and is internalized by cells expressing these receptors. The selectivity and specificity of radioiodinated D2C7 uptake in EGFRwt- and EGFRvIII-expressing tumors was high and superior to those of monospecific MAbs co-administered as positive controls. Taken together, these results suggest that D2C7 warrants further evaluation for the development of antibody-based therapeutics against GBM as well as other cancers characterized by expression of EGFRwt and EGFRvIII. These studies will include the evaluation of optimized labeling methods for both radiohalogens and radiometals in models derived from human GBM.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Diane Satterfield and Lisa Ehinger of the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center Tissue Bank at Duke University Medical Center for providing us with GBM patient tissue. We thank R Ian Cumming and Scott E. Szafranski for FACS analyses, Ling Wang for performing immunohistochemistry, April Coan for statistical analysis, Xiao-Guang Zhao for carrying out the tissue distribution studies, and Janet Parsons for editorial review of the manuscript. This study was supported by the following NIH grants: NINDS 5P50 NS20023, NCI CA42324, NCI 5P50 CA108786, and NCI R37 CA011898.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].McLendon R, Rosenblum M, Bigner D. Russell and Rubinstein’s Pathology of Tumors of the Nervous System. Seventh edition Hodder Arnold; London: 2006. p. 1132. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kleihues P, Cavenee W. Pathology & Genetics - Tumours of the Nervous System. IARC Press; Lyon: 2000. pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stupp R, Mason W, Bent Mvd, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn M, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Friedman H, Prados M, Wen P, Middlesen T, Schiff D, Abrey L, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:4733–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stupp R, Hegi M, Mason W, Bent Mvd, Taphoorn M, Janzer R, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncology. 2009;10:459–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vredenburgh J, Desjardins A, II JH, Dowell J, Reardon D, Quinn J, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and irinotecan in recurrent malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1253–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vredenburgh J, Desjardins A, II JH, Marcello J, Reardon D, Quinn J, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Libermann TA, Nusbaum HR, Razon N, Kris R, Lax I, Soreq H, et al. Amplification, enhanced expression and possible rearrangement of EGF receptor gene in primary human brain tumours of glial origin. Nature. 1985;313:144–7. doi: 10.1038/313144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bigner SH, Burger PC, Wong AJ, Werner MH, Hamilton SR, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Gene amplification in malignant human gliomas: clinical and histopathologic aspects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1988;47:191–205. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wong AJ, Ruppert JM, Bigner SH, Grzeschik CH, Humphrey PA, Bigner DS, et al. Structural alterations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2965–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Humphrey P, Wong A, Vogelstein B, Zalutsky M, Fuller G, Archer G, et al. Anti-synthetic peptide antibody reacting at the fusion junction of deletion-mutant epidermal growth factor receptors in human glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4207–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lund-Johansen M, Bjerkvig R, Humphrey PA, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, Laerum OD. Effect of epidermal growth factor on glioma cell growth, migration, and invasion in vitro. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6039–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chin L, Meyerson M, Aldape K, Bigner D, Mikkelsen T, VandenBerg S, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Quan A, Barnett G, Lee S, Vogelbaum M, Toms S, Staugaitis S, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor amplification does not have prognostic significance in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Oncology Biol Phys. 2005;63:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shinojima N, Tada K, Shiraishi S, Kamiryo T, Kochi M, Nakamura H, et al. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6962–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Watanabe K, Tachibana O, Sata K, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Overexpression of the EGF receptor and p53 mutations are mutually exclusive in the evolution of primary and secondary glioblastomas. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:217–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00848.x. discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pimentel E. Peptide growth factors. In: Pimentel E, editor. Handbook of growth factors. CRC; London: 1994. pp. 104–85. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Hegi ME, Stupp R. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in neuro-oncology: hopes and disappointments. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:957–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wikstrand CJ, Fung KM, Trojanowski JQ, McLendon RE, Bigner DD. Antibodies and molecular immunology: immunohistochemistry and antigens of diagnostic significance. In: Bigner DD, McLendon RE, Bruner JM, editors. Russell and Rubinstein’s Pathology of the Nervous System. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 251–304. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Laskin JJ, Sandler AB. Epidermal growth factor receptor: a promising target in solid tumours. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Boskovitz A, Wikstrand CJ, Kuan CT, Zalutsky MR, Reardon DA, Bigner DD. Monoclonal antibodies for brain tumour treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1453–71. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition strategies in oncology. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:689–708. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stragliotto G, Vega F, Stasiecki P, Gropp P, Poisson M, Delattre JY. Multiple infusions of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody (EMD 55,900) in patients with recurrent malignant gliomas. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:636–40. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Faillot T, Magdelenat H, Mady E, Stasiecki P, Fohanno D, Gropp P, et al. A phase I study of an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:478–83. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wersall P, Ohlsson I, Biberfeld P, Collins VP, von Krusenstjerna S, Larsson S, et al. Intratumoral infusion of the monoclonal antibody, mAb 425, against the epidermal-growth-factor receptor in patients with advanced malignant glioma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;44:157–64. doi: 10.1007/s002620050368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Epenetos AA, Courtenay-Luck N, Pickering D, Hooker G, Durbin H, Lavender JP, et al. Antibody guided irradiation of brain glioma by arterial infusion of radioactive monoclonal antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor and blood group A antigen. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1463–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6480.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brady LW, Miyamoto C, Woo DV, Rackover M, Emrich J, Bender H, et al. Malignant astrocytomas treated with iodine-125 labeled monoclonal antibody 425 against epidermal growth factor receptor: a phase II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:225–30. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91009-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kalofonos HP, Pawlikowska TR, Hemingway A, Courtenay-Luck N, Dhokia B, Snook D, et al. Antibody guided diagnosis and therapy of brain gliomas using radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor and placental alkaline phosphatase. J Nucl Med. 1989;30:1636–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Quang TS, Brady LW. Radioimmunotherapy as a novel treatment regimen: 125I-labeled monoclonal antibody 425 in the treatment of high-grade brain gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:972–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Scott AM, Lee FT, Tebbutt N, Herbertson R, Gill SS, Liu Z, et al. A phase I clinical trial with monoclonal antibody ch806 targeting transitional state and mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4071–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611693104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wikstrand CJ, Hale LP, Batra SK, Hill ML, Humphrey PA, Kurpad SN, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against EGFRvIII are tumor specific and react with breast and lung carcinomas and malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3140–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Batra SK, Castelino-Prabhu S, Wikstrand CJ, Zhu X, Humphrey PA, Friedman HS, et al. Epidermal growth factor ligand-independent, unregulated, cell-transforming potential of a naturally occurring human mutant EGFRvIII gene. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1251–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sampson JH, Crotty LE, Lee S, Archer GE, Ashley DM, Wikstrand CJ, et al. Unarmed, tumor-specific monoclonal antibody effectively treats brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130166597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang W, Barth RF, Wu G, Ciesielski MJ, Fenstermaker RA, Moffat BA, et al. Development of a syngeneic rat brain tumor model expressing EGFRvIII and its use for molecular targeting studies with monoclonal antibody L8A4. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:341–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yang W, Barth RF, Wu G, Kawabata S, Sferra TJ, Bandyopadhyaya AK, et al. Molecular targeting and treatment of EGFRvIII-positive gliomas using boronated monoclonal antibody L8A4. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3792–802. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ding D, Kanaly C, Bigner D, Cummings T, II JH, Pastan I, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of free gadolinium with the recombinant immunotoxin MR1-1. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nagane M, Coufal F, Lin H, Bogler O, Cavenee WK, Huang HJ. A common mutant epidermal growth factor receptor confers enhanced tumorigenicity on human glioblastoma cells by increasing proliferation and reducing apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5079–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wikstrand CJ, McLendon RE, Friedman AH, Bigner DD. Cell surface localization and density of the tumor-associated variant of the epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFRvIII. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4130–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wikstrand CJ, McLendon RE, Bullard DE, Fredman P, Svennerholm L, Bigner DD. Production and characterization of two human glioma xenograft-localizing monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5933–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].He X, Archer GE, Wikstrand CJ, Morrison SL, Zalutsky MR, Bigner DD, et al. Generation and characterization of a mouse/human chimeric antibody directed against extracellular matrix protein tenascin. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;52:127–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].CBTRUS . Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2000-2004. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Liu L, Backlund LM, Nilsson BR, Grander D, Ichimura K, Goike HM, et al. Clinical significance of EGFR amplification and the aberrant EGFRvIII transcript in conventionally treated astrocytic gliomas. J Mol Med. 2005;83:917–26. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Umesh S, Tandon A, Santosh V, Anandh B, Sampath S, Chandramouli BA, et al. Clinical and immunohistochemical prognostic factors in adult glioblastoma patients. Clin Neuropathol. 2009;28:362–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zalutsky MR, Archer GE, Garg PK, Batra SK, Bigner DD. Chimeric anti-tenascin antibody 81C6: increased tumor localization compared with its murine parent. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:449–58. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Reist CJ, Archer GE, Kurpad SN, Wikstrand CJ, Vaidyanathan G, Willingham MC, et al. Tumor-specific anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III monoclonal antibodies: use of the tyramine-cellobiose radioiodination method enhances cellular retention and uptake in tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Reist CJ, Batra SK, Pegram CN, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. In vitro and in vivo behavior of radiolabeled chimeric anti-EGFRvIII monoclonal antibody: comparison with its murine parent. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:639–47. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Luwor RB, Johns TG, Murone C, Huang HJ, Cavenee WK, Ritter G, et al. Monoclonal antibody 806 inhibits the growth of tumor xenografts expressing either the de2-7 or amplified epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) but not wild-type EGFR. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5355–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Johns TG, Adams TE, Cochran JR, Hall NE, Hoyne PA, Olsen MJ, et al. Identification of the epitope for the epidermal growth factor receptor-specific monoclonal antibody 806 reveals that it preferentially recognizes an untethered form of the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30375–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jungbluth AA, Stockert E, Huang HJ, Collins VP, Coplan K, Iversen K, et al. A monoclonal antibody recognizing human cancers with amplification/overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:639–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232686499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Johns TG, Stockert E, Ritter G, Jungbluth AA, Huang HJ, Cavenee WK, et al. Novel monoclonal antibody specific for the de2-7 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that also recognizes the EGFR expressed in cells containing amplification of the EGFR gene. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:398–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hall WA, Fodstad O. Immunotoxins and central nervous system neoplasia. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:1–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Costantini D, McLarty K, Lee H, Done S, Vallis KA, Reilly RM. Anti-tumor effects and normal tissue toxicity of 111In-NLS-trastuzumab in mice bearing HER-positive human breast cancer xenografts. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1084–1091. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.072389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hens M, Vaidyanathan G, Welsh P, Zalutsky MR. Labeling internalizing anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III monoclonal antibody with 177Lu: in vitro comparison of acyclic and macrocyclic .ligands. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Davies GC, Ryan PE, Rahman L, Zajac-Kaye M, Lipkowitz S. EGFRvIII undergoes activation-dependent downregulation mediated by the Cbl proteins. Oncogene. 2006;25:6497–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vaidyanathan G, Alston KL, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Nε-(3-[*I]iodobenzoyl)-Lys5-Nαmaleimido-Gly1-GEEEK ([*I]IB-Mal-D-GEEEK): A radioiodinated prosthetic group containing negatively charged D-glutamates for labeling internalizing monoclonal antibodies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:1085–1092. doi: 10.1021/bc0600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Foulon CF, Reist CJ, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Radioiodination via D-amino acid peptide enhances cellular retention and tumor xenograft targeting of an internalizing anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4453–4460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Improved xenograft targeting of tumor-specific anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III antibody labeled using N-succinimidyl 4-guanidinomethyl-3-iodobenzoate. Nucl Med Biol. 2002;29:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]