Abstract

Electrons are allowed to pass through a single atom connected to two electrodes without being scattered as the characteristic size is much smaller than the inelastic mean free path. In this quasi-ballistic regime, it is difficult to predict where and how power dissipation occurs in such current-carrying atomic system. Here, we report direct assessment of electrical heating in a metallic nanocontact. We find asymmetric electrical heating effects in the essentially symmetric single-atom contact. We simultaneously identified the voltage polarity independent onset of the local heating by conducting the inelastic noise spectroscopy. As a result, we revealed significant heat dissipation by hot electrons transmitting ballistically through the junction that creates a hot spot at the current downstream. This technique can be used as a platform for studying heat dissipation and transport in atomic/molecular systems.

Understanding and control of heat dissipation in nanoscale structures is one of the key issues in development of atomic- and molecular-scale electronics1,2,3,4. Unlike diffusive electron transport in macroscopic systems, electronic charges are allowed to transmit through conductors without being scattered by phonons or defects when the characteristic size is much smaller than the inelastic mean free path. Energy dissipation in this quasi-ballistic regime is still non-negligible because of the huge current density that leads to relatively high electron-phonon scattering rates in the microstructures5,6,7,8,9,10. This has been elucidated by recent experiments that report substantial local heating in current-carrying atomic and molecular junctions11,12,13,14,15,16.

In contrast, little attention has been paid to power dissipation via hot electrons escaping through a quasi-ballistic contact under high field3,17, which is of practical importance from viewpoint of assessing energy efficiency and current carrying capacity of atomic/molecular electronic devices. In the present work, therefore, we developed a micro-fabricated temperature sensing system for exploring electrical heating in Au single atom contacts. The operational principle is based on a mechanically-controllable break junction (MCBJ), a well-established method widely used for forming stable atom-sized junctions18,19. Our idea here is to embed a lithographically-defined resistance thermometer20 in MCBJs and utilize it to measure the local temperature at the banks of the free-standing single-atom contact under a current flow.

Results

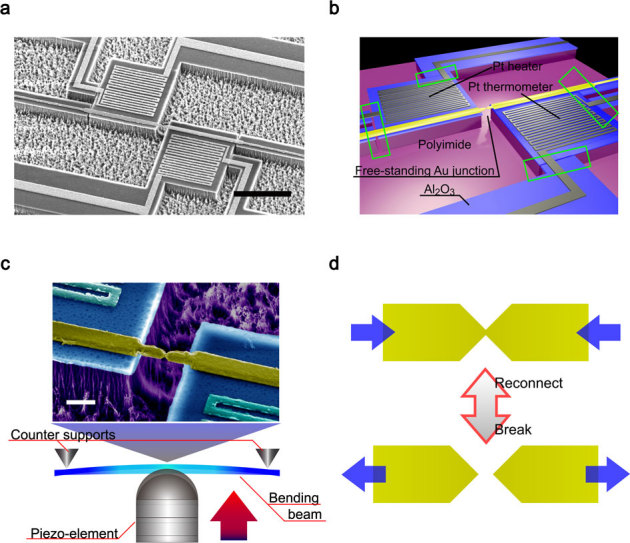

The configuration of a temperature-sensor-integrated MCBJ is shown in Fig. 1 a–d (see also Methods). It consists of a free-standing Au nano-junction and adjacent Pt coils that serve as a resistance thermometer. The device architecture is designed to achieve a high sensitivity for local temperature measurements. The Pt sensing elements are thermally coupled to the junction via the underlying Al2O3 layer. Furthermore, Pt and Au leads were made partially free-standing for the sake of minimizing heat escape from the square Al2O3 regions. The whole structure was fabricated on a thick polyimide layer possessing excellent thermal insulating characteristics (thermal conductivity is about 0.3 W/mK, two orders of magnitude lower than that of Al2O3) to prevent heat leakage to the substrate.

Figure 1. Structure and operational principle of a micro-thermometer-embedded mechanically-controllable break junction (MCBJ).

(a,b) A scanning electron microscopy image (a) and a schematic layout of a thermometer-integrated MCBJ (b). The device consists of a free-standing Au nano-junction and two adjacent Pt coils that function as a heater and a resistance thermometer. The alumina layers thermally connect the junction and the Pt coils. Regions marked by green rectangles possess free-standing structure. Scale bar is 10 μm. (c) A three-point bending configuration used for break junction experiments. Scale bar in the magnified view of a Au nanobridge is 1 μm. (d) The Au contact can be broken and re-formed by manipulating the beam bending.

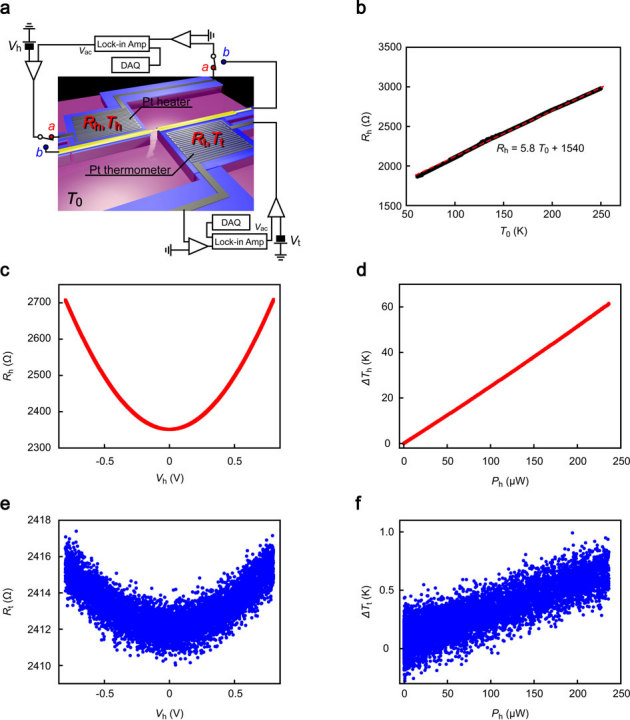

The sensitivity of the micro-thermometers was evaluated by examining Joule heating at the Pt coil heater and characterizing the temperature change using the Pt thermometer on the other side of the Au nano-junction exploiting the temperature response of the resistance Rh and Rt of the heater and the thermometer, respectively (Fig. 2 a) and the calibration curve (Fig. 2 b) for converting Rh(t) to Th(t) of the heater (thermometer) through the temperature coefficient r (see Methods for calibration of Pt resistance thermometer). Specifically, we measured Rh under a linear voltage sweep from Vh = −0.8 V to 0.8 V applied to the heater at a rate of 2 mV/s and simultaneously recorded Rt using the lock-in technique with the ac voltage Vac of 2 mV at 1 kHz for a closed Au junction at T0 = 150 K. The Rh – Vh as well as Rt – Vh characteristics reveal a parabolic feature (Fig. 2 c and e). We deduced a temperature rise at the heater ΔTh and the thermometer ΔTt from the Joule heating-induced increase in the resistivity through ΔTh(t) = (Rh(t) - R0) / r (R0 is the residual resistance estimated by extrapolating the Rh(t)-T0 curve to T0 = 0 K), which is valid in the present condition wherein f ≫ 2πτ where f = 1 kHz is the voltage modulation frequency and τ is the thermal time constant, and plotted as a function of the dissipated power in the Pt heater Ph = Vh2/ Rh (Fig. 2 d and f). We see that ΔTh and ΔTt scale linearly with Ph. This suggests steady-state power dissipation and a certain level of heat diffusion from the heater to the thermometer via the Au junction21. The fact that ΔTh is more than one order of magnitude higher than ΔTt infers only a limited amount of heat transfer across the free-standing nano-junction due to the relatively small thermal conductance compared to that of the Au and Pt micro-leads.

Figure 2. Detection of Joule heat generated at a micro-heater.

(a) A circuit used for the local temperature measurements. The lock-in amplifiers are employed to measure the resistance of the Pt coils. The circuit can also be utilized for measuring the resistance of the Au junction by turning the switch from a to b. (b) A calibration curve of the Pt thermometer. (c,d) Increase in the resistance of Pt heater Rh during a bias ramp plotted as a function of the applied dc voltage Vh (c) and corresponding temperature rise ΔTh depicted as a function of power Ph consumed by the heater (d). (e,f) A concomitant change in the Pt thermometer resistance Rt (e) and corresponding temperature rise ΔTt depicted as a function of power Ph that indicates an increase of the local temperature at the thermometer by heat transfer from the heater via the Au nanobridge (f).

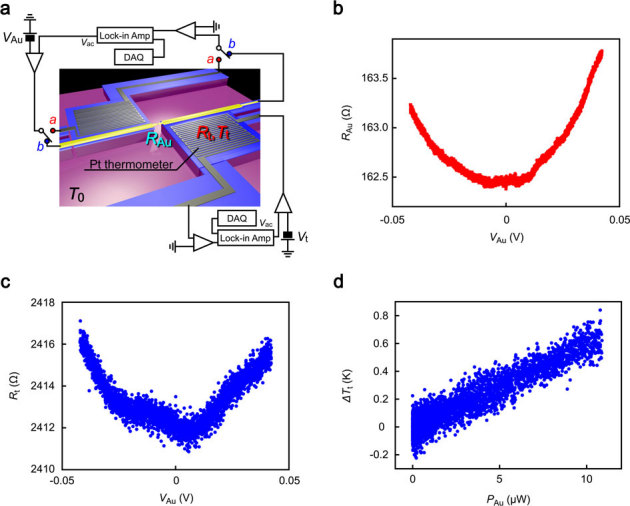

The local temperature measurements were applied to detect Joule heat generated in a Au nano-junction at T0 = 150 K. The wire resistance RAu was obtained by the ac method utilizing the ac voltage Vac of 2 mV at 1 kHz in a voltage range from VAu = −0.05 V to 0.05 V (Fig. 3 a). We observed a non-linear increase in RAu with |VAu| associated with electrical heating (Fig. 3 b). It is noticeable that RAu – VAu characteristics is asymmetric with respect to the bias polarity. This behavior is ascribed to annealing effects on the microstructure such as grain size and defect density and accompanied irreversible change in the electrical conductivity by Joule heating22. Heat dissipation in the Au bridge led to concurrent rise in the resistance of the adjacent Pt thermometer as presented in Fig. 3 c. In accordance to the RAu – VAu characteristics, Rt (and equivalently the local temperature at the thermometer) demonstrated irregular increase with VAu, further suggesting structure deformation in the Au contact during electrical heating22. Meanwhile, Tt – PAu plots reveal linear feature that manifests diffusive transport in the Au nano-contacts and Joule heating origin of the local temperature increase at the thermometer, where PAu = VAu2/RAu is the power dissipated in Au nano-junctions (Fig. 3 d)21.

Figure 3. Electrical heating of a Au nano-junction at T0 = 150 K.

(a) A measurement circuit utilized for characterization of Joule heat generated in a Au nano-junction. Bias voltage VAu was applied to the Au nano-constriction and the resistance of the junction RAu as well as that of the thermometer Rt was measured simultaneously. (b) The junction resistance RAu increases with VAu by Joule heating. (c) At the same time, the thermometer resistance Rt also increases. The irregular behaviour of Rt is presumably due to annealing effects on the Au contact microstructure. (d) The local temperature change at the thermometer ΔTt scales linearly with the power PAu consumed by the junction.

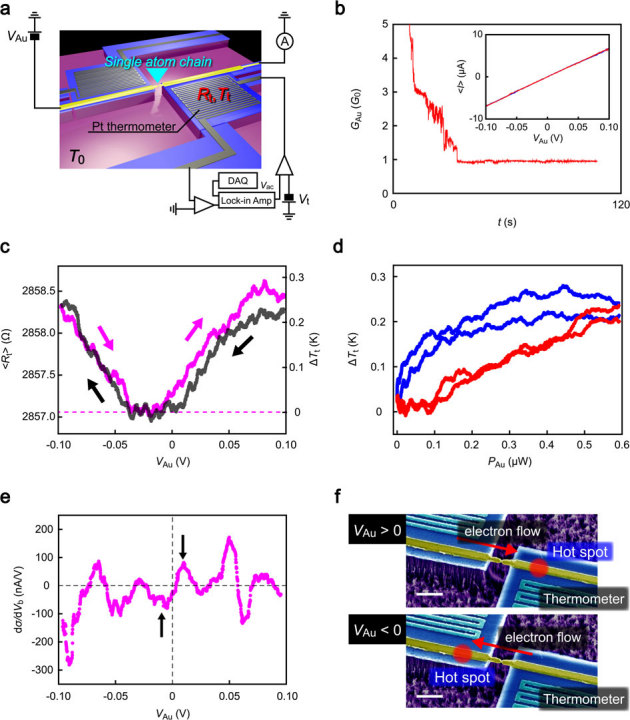

Having verified the adequate sensitivity of the micro-thermometer for detecting Joule heat occurring in the Au nano-bridge, we extended the power dissipation characterization to a single-atom chain (Fig. 4 a). After forming and holding a Au single atom contact at T0 = 80 K (Fig. 4 b, see also Methods), we performed simultaneous measurements of I – VAu characteristics and the thermometer resistance. As the atomic contact tend to become unstable under elevated field by the local heating and current-induced forces, a small bias ramp of VAu ≤ 0.1 V was used (Fig. 4 a). Furthermore, we collected 10 points of I and Rt at each 0.2 mV step of VAu for better resolution of the temperature sensor in the low-power regime. The resulting ramp rate was 0.2 mV/s. We calculated the average current <I> and the thermometer resistance <Rt> from the 10-point data. A linear <I> – VAu curve was obtained reflecting ballistic electron transport through the Au single-atom chain (Fig. 4 a, inset)10,23. At the same time, <Rt> exhibited monotonic increase by about 1 Ω with |VAu| corresponding to the temperature rise of up to about 0.3 K above T0 (Fig. 4 c). The <Rt> – VAu was reproduced in the consecutive sweeps in positive and negative directions indicating stable heat dissipation and diffusion under the relatively slow voltage sweep rate.

Figure 4. Characterization of power dissipation in a quasi-ballistic single-atom contact.

(a) The measurement set up used for detection of local electrical heating in a Au single atom contact. Bias voltage VAu was swept in a range from −0.1 V to 0.1 V and the resistance Rt of the thermometer was simultaneously recorded. (b) Formation of a Au single-atom wire using the self-breaking technique at T0 = 80 K under VAu = 0.05 V. The contact conductance GAu ( = 1/RAu) exhibits a flat plateau at about 1 G0 during mechanical stretching signifying junction thinning to a single-atom size. Inset is the average current-voltage (<I> – VAu) characteristics measured for a Au single-atom contact. (c) The local temperature change ΔTt at the thermometer during the voltage sweep on the single-atom junction estimated from the average Pt coil resistance <Rt>. (d) Plots of ΔTt with respect to PAu = VAu2/ RAu. Red (blue) dots correspond to ΔTt at VAu < 0 V (VAu > 0 V) in (b). (e) The noise spectrum of Au single atom wire. Dashed lines are a guide to the eyes. Arrows point to the lowest peak that represents an onset of local ionic heating in the atomic bridge. (f) Hot electron heating mechanism. A hot spot is generated at the different side of the junction depending on the bias polarity. Scale bars denote 1 μm.

Discussion

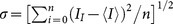

It is of interest to explore the underlying physics of the temperature rise at the Pt coil thermometer detected in response to a current flow through a single-atom junction. The positive response of ΔTt to VAu implies non-negligible heat dissipation in the Au junction. However, unlike the typical Joule heating characteristics observed for the nano-contact shown in Fig. 3 d, ΔTt – PAu plots for the single-atom chain reveal nonlinear temperature increase against the input power and an asymmetry with respect to the bias polarity (Fig. 4 c,d). In order to shed light on this peculiar feature, we investigated the onset of the electron-phonon-interaction-derived local heating in the single-atom contact by conducting an inelastic noise spectroscopy23,24,25. Current noise is characterized here by the standard deviation  calculated from the set of n-point I data acquired at each VAu step during a voltage sweep. Although the feature as a whole is broadened by thermal smearing, we can find stepwise increase of

calculated from the set of n-point I data acquired at each VAu step during a voltage sweep. Although the feature as a whole is broadened by thermal smearing, we can find stepwise increase of  with VAu as shown in Fig. S3. The corresponding d

with VAu as shown in Fig. S3. The corresponding d /dVAu – VAu curve shows peaks at around |VAu| = 0.01 V (Fig. 4 e). This inelastic spectrum thus suggests an onset of electron-phonon interactions at |VAu| ∼ 0.01 V, the corresponding excitation energy of which corresponds to the acoustic phonon modes of Au single-atom chains10,26.

/dVAu – VAu curve shows peaks at around |VAu| = 0.01 V (Fig. 4 e). This inelastic spectrum thus suggests an onset of electron-phonon interactions at |VAu| ∼ 0.01 V, the corresponding excitation energy of which corresponds to the acoustic phonon modes of Au single-atom chains10,26.

The above results manifest non-negligible local heating in the current-carrying quasi-ballistic single-atom contact that can be a possible cause of the local temperature increase detected by the thermometer. There are two distinct mechanisms responsible for the local heating in atom-sized junctions: electron-phonon and electron-electron scattering. Among these, local ionic heating via electron-phonon scattering fails to explain the bias polarity asymmetry of the ΔTt – VAu dependence: Tt starts to increase from 0 V in positive VAu region whereas the temperature rise is suppressed in the low voltage range of −0.04 V ≤ VAu ≤ 0 V at negative bias side, while on the other hand, there is no conspicuous bias polarity dependence of electron-phonon interactions confirmed in the noise spectrum (Fig. 4 e). For electron-electron scattering, it serves to heat up electrons appreciably in a quasi-ballistic nanoscale conductor by the huge current density and affect the bias dependence of the local junction temperature4,8,27. This local electron heating has been predicted theoretically to originate a larger current density at the electron flow downstream and accompanied significant electron-phonon scattering there that causes a hot spot at one side of the junction. The asymmetric ΔTt – VAu dependence can thus be explained qualitatively by the contribution of this electron heating. However, it is also anticipated that the electron heating effect is less significant compared to the local ionic heating and not detectable in metallic nanocontacts4,8,27. Therefore, although we cannot rule out the possibility, the asymmetric heating in the Au single-atom chain found in the present study may not be attributed to the local electron heating mechanism.

On the other hand, it is more likely that power dissipation by hot electrons is responsible for the electrical heating phenomenon identified through the local temperature measurements here. The accelerated electrons transmit ballistically through Au single-atom junctions and become scattered by phonons at a distance defined by the inelastic mean free path (typically several hundreds of nanometer under low field) and release the kinetic energy there17. This hot electron heating is thus directional along the electric field; a hot spot is created close to (away from) the thermometer at the electron flow downstream under positive (negative) VAu (Fig. 4 f). As a consequence, the heating effects became too weak to cause a detectable change in Tt at small negative VAu where power dissipation of hot electrons took place at the opposite side of the single-atom contact, since heat transfer to the thermometer becomes less efficient due to the relatively large thermal resistance at the atomic-scale constriction. Meanwhile, the asymmetry of ΔTt – VAu curve is becoming less obvious at the high voltage regions (Fig. 4 c). It is anticipated that inelastic scattering length of hot electrons diminishes with VAu because of enhanced probability of multiphonon scattering28,29, thereby shifting the hot spot closer to the junction. As a result, a hot spot generated near the thermometer under positive VAu tends to move away from the thermometer as VAu increases and gives rise to the saturation-like local heating effects at the high biases. In contrast, the hot spot moves closer to the thermometer when sweeping VAu from 0 to −0.1 V, which leads to more pronounced heating effects at high |VAu| in the negative bias regime. Eventually, asymmetry of the hot electron heating effects disappears under high field as hot spot emerges at the vicinity of the Au single atom contact under high field irrespective of the bias polarity, which explains the high-bias ΔTt behavior in Fig. 4 c. In fact, quantitatively, fraction of the power dissipated in the single-atom chain should be marginal considering the ballistic nature of electron transport3. Therefore, predominant portion of the power is dissipated via inelastic scattering of hot electrons at the current downstream side of the contact bank.

Methods

Fabrication of micro-thermometer-embedded mechanically-controllable break junctions

Micro-thermometer-embedded MCBJs were fabricated as follows (see also Fig. S1). First, a polyimide layer (Pyre-Ml, Industrial Summit Technology Co.) of 4 μm thick was spin coated on one side of a phosphorous bronze substrate. Micro-electrodes were fabricated on the polyimide surface using a photo-lithography technique followed by metal deposition (Cr/Au = 2 nm/20 nm) with a radio-frequency magnetron sputtering method and subsequent lift-off (Fig. S1 (a)). Al2O3 films of 20 nm thick were then rendered using an electron-beam lithography, radio-frequency magnetron sputtering, and lift-off processes. Subsequently, Au junctions having a narrow constriction with a cross-section of about 100 nm×100 nm was formed (a thin Cr layer of 1 nm thick was used for adhesion). After that, Pt coils were prepared, whose thickness and width were 30 nm and 300 nm, respectively. Finally, the sample was exposed to isotropic reactive ion etching with a mixture gas of CF4/O2. As a result, polyimide underneath was removed making the Au and Pt electrodes partially free-standing (Fig. S1 b).

Mechanical break junction system configuration

The micro-thermometer-embedded MCBJ was mounted on the stage of a cryostat in a three-point bending configuration. A piezo-actuator-driven pushing rod was placed at the back of the sample to mechanically bend the phosphorous bronze beam (Fig. 1 c). By doing so, we could narrow the constriction of the Au nanobridge by the necking and form a stable atom-sized contact (Fig. 1 d)30. After evacuating the chamber to below 10−5 Torr, we introduced liquid coolant and cooled the junction.

Pt heater and thermometer calibrations

The platinum thermometers were calibrated by checking the resistance change Rh and Rt of the Pt heater and the Pt resistance thermometer during the cooling process21,31. For this, ac voltage of Vac = 2 mV at 1 kHz was applied to the Pt coils and the differential resistance Rh(t) was acquired using two lock-in amplifiers (SR830, Stanford Research Systems Co.) while monitoring the substrate temperature T0 with a temperature sensor/controller (Scientific Instruments Model 9700) as schematically depicted in Fig. 2 a. We observed linear decrease of Rh with decreasing T0 from 300 K to 60 K at a rate of r = 5.8 Ω/K (Fig. 2 b), which is attributed to mitigated electron-phonon scattering at the low temperatures. Among the samples we fabricated, r as well as the room temperature resistance varied in a range of 4 to 7 Ω/K and 2500 to 3500 Ω, respectively. The scattering of these sensor parameters stem most likely from a difference in the coil geometries and microstructures. We note that this temperature coefficient agrees with the previous experimental reports21.

Single-atom contact formation

We imposed a tensile stress on the Au nano-bridge by mechanically bending the MCBJ substrate. By doing so, the junction was elongated by d = rMCBJ L, where d and L are the displacements of the contact and the piezo-element that bends the phosphor bronze beam, respectively. The attenuation factor rMCBJ was ∼3×10−4 estimated by examining an exponential decay of tunnelling current flowing through the vacuum gap between the two MCBJ electrodes18. As a result, we could break and form a Au junction repeatedly by controlling the substrate bending through manipulation of the piezo-actuator driving voltage. Formation of a single-atom contact was implemented via a resistance-feed-back control of the junction thinning processes30. In this procedure, a fused contact was elongated under a constant voltage of VAu = 0.05 V at a predefined stretching rates ranging from 6 nm/s to 6 pm/s while monitoring the conductance G = 1/RAu11. We observed a gradual decrease of G indicating narrowing of the junction by stress concentration at the constriction and concomitant necking deformation. The conductance trace revealed a staircase-like feature when G is further lowered to below 10 G0, and finally demonstrated a flat plateau at around 1 G0 right before dropping to zero, where G0 = 2e2/h ∼ 77.5 μS is the conductance quantum (Fig. 3 a). At this stage, the atom-sized junction undergoes mechanical thinning via atom rearrangements and eventually evolved into a single-atom chain that possesses one fully opened channel for electron transmission19.

Author Contributions

M. Tsutsui, T. K., and M. Taniguchi planned and designed experiments. M. Tsutsui and M. Taniguchi fabricated MCBJ devices, exhibited single-molecule conductance measurements, and performed data analyses. M. Tsutsui, T. K., and M. Taniguchi co-wrote paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

T. K. Acknowledges financial support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through its “Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology”.

References

- Cahill D. G. et al. Nanoscale thermal transport. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 793 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Pop E., Sinha S. & Goodson K. E. Heat generation and transport in nanometer-scale transistors. Proc. IEEE 94, 1587 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Pop E. Energy dissipation and transport in nanoscale devices. Nano Research 3, 147 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Dubi Y. & Di Ventra M. Heat flow and thermoelectricity in atomic and molecular junctions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 131 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Todorov T. N. Local heating in ballistic atomic-scale contacts. Philos. Mag. B 77, 965 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Todorov T. N., Hoekstra J. & Sutton A. P. Current-induced emblittlement of atomic wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3606–3609 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. –C., Zwolak M. & Di Ventra M. Local heating in nanoscale conductors. Nano Lett. 3, 1691–1694 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- D'Agosta R., Sai N. & Di Ventra M. Local electron heating in nanoscale conductors. Nano Lett. 6, 2935–2938 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin M., Nitzan A. & Ratner M. A. Heat conduction in molecular transport junctions. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155312 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Agrait N., Untiedt C., Rubio-Bollinger G. & Vieira S. Onset of energy dissipation in ballistic atomic wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 216803 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M., Kurokawa S. & Sakai A. Bias-induced local heating in Au atom-sized contacts. Nanotechnology 17, 5334–5338 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. et al. Local ionic and electron heating in single-molecule junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 698–403 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M., Taniguchi M. & Kawai T. Local heating in metal-molecule-metal junctions. Nano Lett. 8, 3293 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe Z. et al. Detection of heating in current-carrying molecular junctions by Raman scattering. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 727–732 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze G. et al. Resonant electron heating and molecular phonon cooling in single C60 junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136801 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. R., Corley D. A., Tour J. M. & Natelson D. Vibrational and electronic heating in nanoscale junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 33–38 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbritter A. et al. Connective neck evolution and conductance steps in hot point contacts. Phys. Rev. B 65, 045413 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- van Ruitenbeek J. M. et al. Adjustable nanofabricated atomic size contacts. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 67, 108 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Agraït N., Yeyati A. L. & van Ruitenbeek J. M. Quantum properties of atomic-sized conductors. Phys. Rep. 377, 81 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Schwab K., Henrikesen E. A., Worlock J. M. & Roukes M. L. Measurement of the quantum of thermal conductance. Nature 404, 974–977 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P., Shi L., Majumdar A. & McEuen P. L. Thermal transport measurements of individual multiwalled nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 215502 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B. et al. In situ transmission electron microscopy imaging of grain growth in a platinum nanobridge induced by electric current annealing. Nanotechnol. 22, 205705 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M., Taniguchi M. & Kawai T. Single-molecule identification via electric current noise. Nat. Commun. 1, 138 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C. & Di Ventra M. Effect of electron phonon scattering on shot noise in nanoscale junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 166802 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt F., Novotony T. & Belzig W. Phonon-assisted noise in molecular junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 136601 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski H., Mehlhorn M. & Margenstern K. Imaging phonon excitation with atomic resolution. Science 319, 930–933 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agosta R. & Di Ventra M. Local electron and ionic heating effects on the conductance of nanostructures. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20, 374102 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanson I. K. & Shklyarevskii O. I. Point-contact spectroscopy of metallic alloys and compounds. Sov. J. Low Temp. Phys. 12, 509 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Persson B. N. J. & Demuth J. E. Inelastic electron tunneling from a metal tip. Solid State Communs. 57, 769–772 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M., Taniguchi M. & Kawai T. Atomistic mechanics and formation mechanism of metal-molecule-metal junctions. Nano Lett. 9, 2433–2439 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. et al. Measuring thermal and thermoelectric properties of one-dimensional nanostructures using a microfabricated device. J. Heat Trans. 125, 881 (2003). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information