Abstract

β–amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a critical factor in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). APP undergoes posttranslational proteolysis/processing to generate the hydrophobic β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides. Deposition of Aβ in the brain, forming oligomeric Aβ and plaques, is identified as one of the key pathological hallmarks of AD. The processing of APP to generate Aβ is executed by β- and γ-secretase and is highly regulated. Aβ toxicity can lead to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal cell death, impaired learning/memory and abnormal behaviors in AD models in vitro and in vivo. Aside from Aβ, proteolytic cleavages of APP can also give rise to the APP intracellular domain (AICD), reportedly involved in multiple types of cellular events such as gene transcription and apoptotic cell death. In addition to amyloidogenic processing, APP can also be cleaved by α-secretase to form a soluble or secreted APP ectodomain (sAPP-α) that has been shown to be mostly neuro-protective. In this review, we describe the mechanisms involved in APP metabolism and the likely functions of its various proteolytic products to give a better understanding of the patho/physiological functions of APP.

Keywords: β–amyloid precursor protein, α-secretase, β-secretase, γ-secretase, caspase

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), first officially described by the German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer in 1906, is the most common form of dementia. Characterized by progressive cognitive impairment, loss of memory and abnormal behavior, AD generally affects people over the age of 65. However, around 5% of AD patients develop the disease phenotype at a much younger age (~40 to 50 years old) and are classified as early-onset, most of which are also familial cases. Plaques consisting of β–amyloid (Aβ) peptide (Selkoe 1998), neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) consisting largely of hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated tau protein (Buee et al. 2000; Gendron and Petrucelli 2009) and neuron loss in the hippocampus and cortex regions are the major pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. As Aβ is believed to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of AD, its precursor protein APP has become one of the most studied proteins in the field of AD research.

Basic knowledge of APP

The amyloid plaques associated with AD were first purified and found to consist of multimeric aggregates of Aβ polypeptide containing about 40 amino acid residues in the mid-1980s (Glenner and Wong 1984; Masters et al. 1985). Cloning of the complementary DNA (cDNA) of Aβ revealed that Aβ is derived from a larger precursor protein (Tanzi et al. 1987). The full-length cDNA of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) was later isolated and sequenced and APP was predicted to be a glycosylated integral membrane cell surface receptor protein with 695 amino acids (Kang et al. 1987). The Aβ peptide was found to be a cleavage product derived from the transmembrane domain of this large precursor protein.

The APP gene is located on chromosome 21 and contains 18 exons. Although alternative splicing of transcripts from the single APP gene results in several isoforms of the gene product, APP695, whose encoding cDNA lacks the gene sequence from exons 7 and 8, is preferentially expressed in neurons (Sandbrink et al. 1994). APP751, lacking exon 8, and APP770, encoded with all 18 exons, are predominant variants elsewhere (Yoshikai et al. 1990). Two homologues of APP were also identified and named APP-like protein 1 and 2 (APLP1 and APLP2) (Wasco et al. 1992; Wasco et al. 1993; Coulson et al. 2000). APLP2, similarly to APP, is expressed ubiquitously while APLP1 is only expressed in the brain and is only found in mammals.

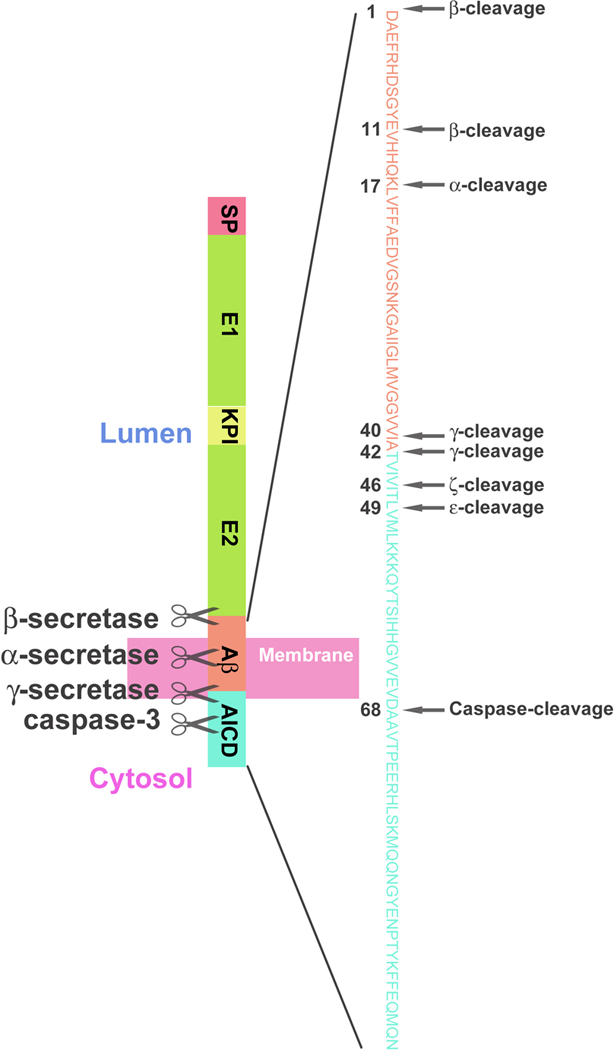

The APP protein is a type I integral membrane protein with a large extracellular portion, a hydrophobic transmembrane domain, and a short C-terminus designated the APP intracellular domain (AICD). The extracellular portion of APP contains E1 and E2 domains and a Kunitz protease inhibitor (KPI) domain that is missing in APP695 (Kang and Muller-Hill 1990;Rohan de Silva et al. 1997). The E1 domain is reported to function as the major interaction interface for dimerization of cellular APP/APLPs (Soba et al. 2005). Although trans-dimerization of the E2 domain is also observed in X-ray structures (Wang and Ha 2004), biochemical assays have failed to confirm such a trans-dimerization (Soba et al. 2005). The levels of APP isoforms with a KPI domain seem to be elevated in patients with AD (Menendez-Gonzalez et al. 2005) and a splicing shift in neurons from APP695 to KPI-containing APP isoforms, along with increased Aβ generation, is observed when the NMDA receptor is activated (Bordji et al. 2010). These studies suggest that an alteration in APP splicing may contribute to disease pathogenesis.

APLP1 and APLP2 are both type I integral membrane proteins and share conserved structures with APP, including a large extracellular motif containing the E1 and E2 domains and a short intracellular domain. However, the transmembrane domain is not conserved among APP and APLPs and the Aβ sequence is unique to APP. In addition, APLP1 does not possess the KPI domain due to a lack of the encoding exon in the APLP1 gene.

Manipulations of the APP/APLPs genes suggest that they are partially functionally redundant. Upon individual deletion of any of these three genes, mice are viable with only relatively subtle abnormalities (Zheng et al. 1995; Dawson et al. 1999). However, APP/APLP2, APLP1/APLP2 double knockout or APP/APLP1/APLP2 triple knockout mice show early postnatal lethality. Interestingly, APP/APLP1 double knockout mice are viable, indicating a crucial function of APLP2 in the absence of either APP or APLP1 (von Koch et al. 1997; Heber et al. 2000; Herms et al. 2004). Although it was reported that neurons generated from APP/APLP1/APLP2 triple knockout embryonic stem cells behave normally in vitro and in vivo (Bergmans et al. 2010), abnormal developments in the peripheral and central nervous system were repeatedly observed in both APP/APLP2 double knockout mice and APP/APLP1/APLP2 triple knockout mice (Wang et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009). Studies reported that the APP/APLP2 double knockout results in impaired neuromuscular junctions, indicating that the trans-synaptic interaction of APP is necessary for the proper development of motor neurons. Cortical dysplasia due to defective neuronal migration was also shown in APP/APLP1/APLP2 triple knockout mice (Herms et al. 2004). Although the physiological functions of APP/APLPs have not been well characterized, these loss-of-function phenotypes suggest the comprehensive involvement of these proteins during development.

APP processing

APP undergoes posttranslational processing, involving several different secretases and proteases, via two major pathways. In the non-amyloidogenic pathway, APP is sequentially cleaved by α-secretase and γ-secretase. α-cleavage, which cuts APP at the 17th amino acid inside the Aβ peptide sequence (Fig. 1), releases a large secreted extracellular domain (sAPP-α) and a membrane-associated C-terminal fragment consisting of 83 amino acids (C83). APP C83 is further cleaved by γ-secretase to release a P3 peptide and the APP intracellular domain (AICD), both of which are degraded rapidly. In the amyloidogenic pathway, APP is primarily processed by β-secretase at the 1st residue or at the 11th residue (so called β’ site) of the Aβ peptide sequence (Fig. 1), shedding sAPP-β and generating a membrane associated C terminal fragment consisting of 99 amino acids (C99) (Sarah and Robert 2007). γ-secretase further cleaves C99 to release AICD and the amyloidogenic Aβ peptide which aggregates and fibrillates to form amyloid plaques in the brain.

Fig. 1.

Proteolytic processing of APP.

α-secretase and α-cleavage

Since APP was found to be constitutively cleaved at the α-site to yield sAPP-α (Esch et al. 1990), three members of the ADAMs (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase), ADAM-10, ADAM-17 and ADAM-9 have been proposed as the α-secretase (Buxbaum et al. 1998; Koike et al. 1999; Lammich et al. 1999).

ADAMs are type I integral membrane proteins that belong to the zinc protease super family and have been implicated in the control of cytokine and growth factor shedding. ADAM10 is widely expressed in the brain and in other tissues (Chantry and Glynn 1990; Howard et al. 1996) and a several fold increase in sAPP-α levels in cell lines overexpressing ADAM10 can be observed (Lammich et al. 1999). Moderate neuronal overexpression of human ADAM10 increases sAPP-α production while reducing Aβ generation/plaque formation in mice carrying the human APP V717I mutation, while expression of a catalytically-inactive form of the ADAM10 mutation increases the size and number of amyloid plaques in mouse brains (Lammich et al. 1999). These findings suggest that ADAM10 may be responsible for constitutive α-cleavage activity. On the other hand, although sAPP-α generation is not affected in ADAM9/17 knock-down cell lines nor in mice carrying deficient ADAM9/17 genes (Weskamp et al. 2002; Kuhn et al. 2010), overexpression of ADAM9/17 does increase the level of sAPP-α under some conditions, suggesting that ADAM9 and ADAM17 are more likely involved in the regulated α-cleavage of APP rather than in constitutive α-cleavage.

In addition to APP, ADAMs have many other substrates (Qiang et al. 2009; Altmeppen et al. 2011). For example, ADAM17 has been identified as the protease responsible for shedding of the transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor-α at its physiological processing site (Black et al. 1997; Moss et al. 1997). ADAM17 also cleaves the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family members (Peschon et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2003) and ADAM17-deficient mice possess the phenotype of mice with an EGF signaling defect (Buxbaum et al. 1998). ADAM10 can cleave Notch and ADAM10-deficient mice develop a loss of Notch signaling phenotype (Hartmann et al. 2002). In addition, ADAM10 and ADAM17 were found to be directly responsible for the constitutive and protein kinase c-regulated processing of prions, respectively (Gouras et al. 2000; Vincent et al. 2001), whereas another ADAM member, ADAM9, acts as an upstream activator of ADAM10 during this process (Cisse et al. 2005).

β-secretase and β-cleavage

Aβ generation is initiated by β-cleavage at the ectodomain of APP, resulting in the generation of an sAPP-β domain and the membrane associated APP C-terminal fragment C99. The putative β-secretase, β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), was first identified and characterized in 1999 (Sinha et al. 1999; Vassar et al. 1999; Yan et al. 1999; Hussain et al. 2000; Lin et al. 2000). BACE1 is a type I transmembrane aspartyl protease with its active site on the luminal side of the membrane. The originally identified full-length BACE1 has 501 amino acids (BACE1–501) and is predominantly expressed in perinuclear post-Golgi membranes, vesicular structures throughout the cytoplasm, as well as on the cell surface (Ehehalt et al. 2002). Several other minor transcripts of BACE1 (BACE1–476, 457 and 432) derived from alternative splicing were found later (Tanahashi and Tabira 2001), however their β-cleavage activity and subcellular localization are different from those of BACE1–501 (Tanahashi and Tabira 2001; Ehehalt et al. 2002). Knocking out the BACE1 gene prevents Aβ generation and completely abolishes Aβ pathology in mice expressing the Swedish mutation of human APP (Farzan et al. 2000; Cai et al. 2001; Luo et al. 2001; Roberds et al. 2001; Ohno et al. 2004; Laird et al. 2005). The expression level and activity of BACE1 were also found to be elevated in AD patients (Holsinger et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2003). However, there is no evidence linking BACE1 gene variants with familial AD (FAD) and the BACE1 gene variants do not affect BACE1’s activity or APP processing/Aβ generation (Sjolander et al. 2010). More recently, BACE1 knockout mice have been found to exhibit hypomyelination and altered neurological behaviors, such as reduced grip strength and elevated pain sensitivity, probably because the physiological functions of other BACE1 substrates, such as neuregulin 1 and the voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1) β2 subunit, are negatively affected in these mice (Laird et al. 2005; Hu et al. 2006; Willem et al. 2006; Gersbacher et al. 2010; Hitt et al. 2010).

BACE2 is a homolog of BACE1 (Acquati et al. 2000; Xin et al. 2000) and human BACE2 shares 71% homology and 45% identity with human BACE1. Similar to BACE1, BACE2 is predominantly localized in post-Golgi structures and on the cell surface (Ehehalt et al. 2002). Notably, Several splice variants of BACE2 were also identified and found to be expressed in several central nervous system subregions (Solans et al. 2000). However, the expression level of BACE2 is much lower in the brain than BACE1 and is mostly expressed in glial cells (Laird et al. 2005). In addition, BACE2 cleaves APP within the Aβ domain in a manner more similar to α-secretase than β-secretase (Farzan et al. 2000).

Cathepsin B was once suspected as a β-secretase candidate (Hook et al. 2005; Schechter and Ziv 2008). However, recent studies suggest that Cathepsin B can degrade Aβ into harmless fragments. It is therefore thought that Cathepsin B plays a role in the body’s natural defense against AD (Mueller-Steiner et al. 2006).

γ-secretase and γ-cleavage

Both α-cleavage and β-cleavage generate short APP C-terminal fragments that are further processed by γ-secretase. Distinct from α-/β-secretases, γ-activity involves a large proteinase complex consisting of at least four major protein components (Presenilin1 or Presenilin2, PEN2, APH1 and Nicastrin) (Vetrivel et al. 2006).

Presenilins (PSs) were identified and cloned in the mid-1990s (Levy-Lahad et al. 1995; Sherrington et al. 1995). Genetic mutations of PSs are found in a large portion of familiar AD (FAD) cases, indicating its crucial role in AD. Although other proteins are required for the γ-secretase complex, PSs are believed to contain the actual protease activity (Wolfe et al. 1999; Wen et al. 2008; Ahn et al. 2010a). PSs are multi-transmembrane proteins and can be cleaved at the cytoplasmic loop between the 6th and 7th transmembrane regions to generate an N terminal and a C terminal fragment during post-translational maturation (Thinakaran et al. 1996). The two fragments interact with each other after the cleavage and they are both necessary for γ-secretase activity. Transgenic mice overexpressing PSs with FAD mutations show significantly increased Aβ42 levels, suggesting that PS mutations probably induce AD by producing more of the hydrophobic Aβ42 form (Duff et al. 1996; Xia et al. 2001).

Nicastrin, identified as a protein that interacts with PS in 2000 (Yu et al. 2000), is a type I membrane glycoprotein with a large ectodomain (Perrin et al. 2009). Nicastrin undergoes a glycosylation/maturation process that causes a conformation change in its ectodomain, which is crucial for the assembly and maturation of the γ-secretase complex and γ-activity (Shirotani et al. 2003; Chavez-Gutierrez et al. 2008). Mature nicastrin can bind to the ectodomain of APP CTFs derived through α-/β-secretase cleavage and may act as a substrate receptor of γ-secretase (Shirotani et al. 2003; Kaether et al. 2004; Shah et al. 2005).

PEN2 and APH1 are another two γ-secretase complex components that were originally identified as the enhancers of PSs (Francis et al. 2002). APH1 is a multiple transmembrane protein with seven transmembrane domains and a cytosolic C terminus (Fortna et al. 2004). APH1 interacts with immature nicastrin and PS to form a relatively stable pre-complex which is then translocated to the trans-Golgi from the ER/cis-Golgi for further maturation (Lee et al. 2002; Kimberly et al. 2003; Takasugi et al. 2003; Jankowsky et al. 2004). PEN2 is a hairpin-like protein with two transmembrane domains and with both ends in the lumen (Crystal et al. 2003; Takasugi et al. 2003). PEN2 is found to mediate the endoproteolysis of PS (Luo et al. 2003). Enhanced γ-secretase activity is also observed when PEN2 is exogenously expressed (Shiraishi et al. 2004).

The γ-secretase complex is assembled in sequential steps. Nicastrin and APH1 initially form a subcomplex (Shirotani et al. 2004) and then PS binds to the Nicastrin-APH1 subcomplex (Takasugi et al. 2003). The joining of PEN2 results in a conformation-dependent activation of γ-secretase (Kimberly et al. 2003; Takasugi et al. 2003). Nicastrin, PEN2, APH1 and PS interact with each other and also mutually modulate each other (Lee et al. 2002; Steiner et al. 2002; Pasternak et al. 2003; Kaether et al. 2004). Nicastrin ablation leads to decreased levels of APH1, PEN2 and PS1 fragments, accompanied by increased levels of immature full-length PS1 (Zhang et al. 2005). Downregulation of APH1, PEN2 or nicastrin also reduces the processing of PS and results in impaired γ-cleavage of APP and Notch (Francis et al. 2002). PS deficiency also results in decreased levels of PEN2 and APH1, as well as impaired glycosylation/maturation of Nicastrin (Zhang et al. 2005).

γ-secretase cleaves APP at multiple sites and in sequential steps to generate Aβ peptides of different lengths (Fig. 1). The majority of Aβ peptides produced are 40 amino acids long, however, peptides ranging from 38 to 43 amino acids are found in vivo. Besides the dominant γ-cleavage site at 40 and 42 residues, ζ-cleavage at 46 and ɛ-cleavage at 49 residues are also thought to be mediated by γ-secretase (Weidemann et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2004; Raben et al. 2005; Sato et al. 2005). Accordingly, various AICDs (C50, C53, C57 and C59) can be generated during these multi-site cleavages executed by γ-secretase. However, all of the endogenous AICD forms are rarely detected, probably due to their very rapid degradation (Ag 2000; Lu et al. 2000; Sastre et al. 2001; Yu et al. 2001; Sato et al. 2003). Interestingly, as the substrate of γ-secretase, APP itself can regulate the intracellular trafficking and cell surface delivery of PS1 (Kuzuya et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2009). In addition, APP has been found to possess a domain that negatively modulates γ-secretase activity in Aβ production by binding to an allosteric site within the γ-secretase complex (Kuzuya et al. 2007; Ahn et al. 2010b; Zhang and Xu 2010). These results reveal a novel mutual regulation between γ-secretase and its substrate.

In addition to cleaving APP, γ-secretase cleaves many other single transmembrane proteins within the transmembrane domain (Lee et al. 2002). One of the most important γ-secretase substrates, Notch, can release its intracellular domain (NICD) upon γ-cleavage. NICD is well-known as a signal molecule that transactivates a number of genes critical to development (Kopan et al. 1996; Schroeter et al. 1998). Mice with ablation of PS1, Nicastrin, or APH1A show Notch-deficient-like lethal phenotypes and neuronal tube formation defects (Shen et al. 1997; Donoviel et al. 1999; Li et al. 2003; Ma et al. 2005). Postnatal forebrain-specific inactivation of PS1 in APP transgenic mice, although preventing Aβ accumulation, failed to rescue contextual memory long-term. Conditional inactivation of γ-secretase components in the forebrain resulted in progressive memory impairment and age-related neurodegeneration (Dominguez et al. 2005; Saura et al. 2005; Serneels et al. 2009; Tabuchi et al. 2009).

Caspase-cleavage

In addition to cleavages involving secretases, APP can be cleaved by caspases independently at its C terminus (Asp664 of APP695), releasing a short tail containing the last 31 amino acids (C31) of APP and a fragment (Jcasp) from between the γ- and caspase-cleavage sites (Lu et al. 2000). Caspase-cleavages of APP are thought to be harmful since both C31 and the Jcasp fragment generated were found to be cytotoxic (Lu et al. 2003a). Transgenic mice with Swedish and Indiana mutations of APP show increased susceptibility to seizures, which can be abolished by a D664A mutation that disrupts caspase-cleavages (Ghosal et al. 2009). These results indicate that caspase-cleavages of APP contribute, at least in part, to the neurotoxicity of APP processing products.

Function of APP and its fragments

Full-length APP

Due to its highly similar structure to Notch, APP has been proposed to function as a cell surface receptor [reviewed in (Zheng and Koo 2011)]. Several studies have reported that certain ligands, including Aβ, F-spondin, Nogo-66, netrin-1 and BRI2, bind to the extracellular domain of APP, resulting in modulated APP processing and sequential downstream signals (Lorenzo et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2003b; Ho and Sudhof 2004; Park et al. 2006; Lourenco et al. 2009; Matsuda et al. 2009; Zheng and Koo 2011). However, the physiological functions of these interactions remain to be determined. Nevertheless, APP is more widely accepted as a protein contributing to cell adhesion via its extracellular domain. Studies have demonstrated that the E1 and E2 regions of APP can interact with extracellular matrix proteins (Small et al. 1999). Furthermore, the E1 and E2 regions of APP were found to interact with themselves, in parallel or anti-parallel, forming homo- (with APP) or hetero-dimers (with APLPs) (Wang and Ha 2004; Soba et al. 2005; Dahms et al. 2010). Recent studies also suggest APP/APLPs as synaptic adhesion molecules as silencing of APP led to defects in neuronal migration (Young-Pearse et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009; Norstrom et al. 2010).

sAPP-α

The constitutively secreted sAPP-α has been found to be neuro-protective (Mattson et al. 1993; Furukawa et al. 1996; Han et al. 2005; Ma et al. 2009). sAPP-α is thought to promote neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis as well as cell adhesion (Mattson 1997; Gakhar Koppole 2008). Studies have found that sAPP-α is a growth factor (Herzog et al. 2004; Siemes et al. 2006) that regulates the proliferation of embryonic and adult neural stem cells (Ohsawa et al. 1999; Caille et al. 2004). In vivo studies have also shown that sAPP-α promotes learning and memory in animal models (Meziane et al. 1998; Taylor et al. 2008). sAPP-α alone is able to rescue most of the abnormalities of APP deficient mice (Ring et al. 2007), implying that most of the physiological functions of APP are conducted by its extracellular domain.

sAPP-β

Although there are only 17 amino acids difference between sAPP-β and sAPP-α, sAPP-β reportedly lacks most of the neuroprotective effects of sAPP-α (Furukawa et al. 1996). A recent study suggested that sAPP-β can be cleaved to generate an N-terminal fragment that is a ligand for death receptor 6, activating caspase-6 which further stimulates axonal pruning and neuronal cell death (Nikolaev et al. 2009).

Aβ

The physiological and pathological functions of Aβ have been extensively investigated due to its central role in AD. Studies have demonstrated that Aβ overproduction leads to neurotoxicity, neuronal tangle formation, synaptic damage and eventually neuron loss in the pathologically affected brain regions (Selkoe 1998; Shankar and Walsh 2009). Among the various Aβ peptides generated by the multiple-site cleavages of secretases, Aβ 42 has proved to be more hydrophobic and amyloidogenic than others (Burdick et al. 1992). Most mutations related to hereditary familiar AD either increase Aβ generation or the ratio of Aβ 42/ Aβ 40 (Borchelt et al. 1996; Scheuner et al. 1996). Studies also suggest that increased Aβ 42 levels probably provide the core for oligomerization, fibrillation and amyloid plaque generation (Jarrett et al. 1993; Iwatsubo et al. 1994).

Although excessive Aβ causes neurotoxicity, some studies have shown that Aβ40 protects neurons against Aβ42-induced neuronal damage and is required for the viability of central neurons (Plant et al. 2003; Zou et al. 2003). Moreover, two groups recently reported that low doses (picomolar) of Aβ can positively modulate synaptic plasticity and memory by increasing long-term potentiation (Morley et al. 2008; Puzzo et al. 2008), revealing a novel physiological function of Aβ under normal conditions.

AICD

Depending on the exact cleavage site of γ-secretase, AICD may have 59, 57, 53 or 50 residues. However, because AICD is quickly degraded after γ-cleavage, the biochemical features and physiological functions of AICD in vivo are difficult to study. So far, most of the information on AICD is deduced based on exogenous systems.

There are several conserved regions located on AICD: a YTSI (653–656 residues according to APP695) motif near the cell membrane, a VTPEER (667–762 residues) helix capping box and a YENPTY (682–687 residues) domain which mediates the interaction between APP/AICD and phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain containing proteins. Many AICD binding proteins have been identified. Some of the proteins, including KLC, Fe65, Shc, JIP, Numb, X11, Clathrin and mDab1, were found to share one or several common PTB domains that specifically interact with the Asn-Pro-X-Tyr amino acid sequence present in the YENPTY motif of AICD (Borg et al. 1996; Brassler et al. 1996; M. McLoughlin and Cj Miller 1996; Howell et al. 1999; Salcini et al. 1999; Kamal et al. 2000; Matsuda et al. 2001; Weggen et al. 2001; Roncarati et al. 2002; Tarr et al. 2002b; Tarr et al. 2002a; Inomata et al. 2003; Matsuda et al. 2003). Other proteins, such as PAT1, SET and 14-3-3γ, are believed to bind to the YTSI or VTPEER motif of AICD (Zheng et al. 1998; Madeira et al. 2005; Sumioka et al. 2005). AICD, therefore, may have different functions when interacting with its’ various binding partners.

AICD also contains three phosphorylation sites, including two threonine residues at 654 and 668 and a serine residue at 665. AICD has been found to be phosphorylated by PKC, calcium-calmodulin dependent-kinase II, GSK3-β, Cdk5 and JNK at the Ser/Thr sites mentioned above. Such phosphorylation may affect APP processing or the binding of AICD-interacting proteins, thus affecting the function of AICD (Gandy et al. 1988; Iwatsubo et al. 1994; Iijima et al. 2000; Inomata et al. 2003).

Since the generation of AICD is very similar to that of many other signaling molecules, such as NICD, which is also generated by γ-cleavage and can mediate the transcription of genes important for development, AICD may function in a similar fashion. Indeed, a role for AICD in gene transactivation is supported by several studies. The most widely accepted mechanism is that AICD, together with Fe65 and Tip60, forms a transcriptionally-active complex. Fe65 is one of the most well studied proteins that bind to the YENPTY motif of AICD. Tip60, a histone acetyltransferase, is a component of a larger nuclear complex with DNA binding, ATPase and DNA helicase activities (Ikura et al. 2000). Although Tip60 does not bind to AICD directly, an indirect interaction between AICD and Tip60 is mediated by Fe65. Upon forming this complex, AICD is stabilized and can be translocated into the nucleus to regulate expression of genes such as KAI1, Neprilysin, LRP1, p53, GSK-3β and EGFR (Baek et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2003; Cao and Sudhof 2004; Pardossi-Piquard et al. 2005; Alves da Costa et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007). Another transactivating complex consisting of AICD, Fe65 and CP2/LSF/LBP1 has also been reported to induce the expression of GSK3-β (Kim et al. 2003). Although the transactivation effect of AICD has been observed by different research groups, the model of how AICD functions is still controversial (Cao and Sudhof 2004; Hass and Yankner 2005; Nakaya and Suzuki 2006). It was originally widely accepted that translocating into the nucleus was necessary for AICD to activate gene expression. However, some studies have suggested that an AICD mediated conformational change in Fe65 is sufficient and that the nuclear translocation of AICD is not required (Cao and Sudhof 2004; Hass and Yankner 2005). Another study has suggested that the nuclear translocation of AICD is independent of Fe65 and is a result of its phosphorylation at T668 (Nakaya and Suzuki 2006). More investigation is required to further elucidate the mechanism.

As an adaptor protein involved in protein sorting and trafficking, X11 has been suggested as affecting APP trafficking/metabolism by interacting with AICD, leading to reduced Aβ production. X11 has also been found to suppress the transactivation of AICD, possibly by competing with AICD for the recruitment of Fe65, as they share the same binding motif (Biederer et al. 2002).

Many studies have documented that AICD is cytotoxic and that overexpressing different AICDs (C31, C57, C59) in Hela, H4, N2a or PC12 cell lines, as well as neuronal cell lines, induces cell death (Lu et al. 2000). AICDs lacking the NPTY motif that mediates the interaction between AICD and other proteins failed to induce apoptosis, suggesting the functional involvement of an AICD-binding protein (Xu et al. 2006). A Tip60 loss-of-function mutation makes Hela cells more resistant to apoptosis (Ikura et al. 2000). These results indicate that the cytotoxicity of AICD may be mediated by its interacting proteins. For example, JIP is the scaffolding protein of the JNK pathway kinase and is involved in various cell events including neuronal apoptosis and axonal transporting. By binding to AICD, JIP mediates APP/AICD phosphorylation at Thr668, thus modulating APP trafficking, maturation and processing. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that the cell death triggered by AICD is partially mediated by JIP (Taru et al. 2002).

In addition, AICD-induced cytotoxicity may be mediated by its regulation targets (Kim et al. 2003; Alves da Costa et al. 2006; Vetrivel et al. 2006). For example, P53 expression, as well as p53-mediated apoptosis, can be enhanced by AICD (Alves da Costa et al. 2006; Ozaki et al. 2006). Another AICD target gene, GSK3-β, may also contribute to AICD-related cytotoxicity by upregulating tau hyperphosphorylation. GSK-3β activation and CRMP-2 phosphorylation, along with downstream tau hyper-phosphorylation/aggregation, neurodegeneration and memory loss, are observed in an AICD C59 transgenic mouse line in which Fe65 is co-expressed (Ryan and Pimplikar 2005; Ghosal et al. 2009). However, another group found only increased neuronal sensitivity to toxic and apoptotic stimuli in mice overexpressing AICD either alone or with Fe65 (Giliberto et al. 2008).

On the other hand, C31, a short form of AICD generated by caspase cleavage, has been reported to directly activate caspase-3 in the tumor cell death process (Lu et al. 2000; Bertrand et al. 2001; Nishimura et al. 2002; Madeira et al. 2005). C31 also appears to induce a caspase-independent toxicity by selectively increasing Aβ42 (Dumanchin-Njock et al. 2001). A D664A mutation in AICD, blocking caspase cleavage, abolished the synaptic loss, axonal defects and behavioral changes found in PDAPP(D664A) mice (Galvan et al. 2006). APP binding protein 1 (APBP1) reportedly interacts with AICD and activates the neddylation pathway (Chen 2004), further downregulating the level of β-catenin and potentially resulting in apoptosis. In addition, cellular Ca2+ homeostasis appears to be modulated by AICD (Hamid et al. 2007).

Conclusion

As a crucial protein in AD, APP is multifunctional and can be post-translationally processed via different pathways. The physiological and pathological functions of APP are closely related to the processing of APP, which may suggest therapeutic treatments for AD. In this review, we have summarized the current knowledge of APP metabolism. Further understanding of APP processing and the patho/physiological functions of various APP metabolites will be important for the development of an AD treatment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants (R01AG021173, R01NS046673, R01AG030197 and R03AG034366 to H.X.), and grants from the Alzheimer’s Association (to H.X. and Y.-w.Z.), the American Health Assistance Foundation (to H.X.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (30973150 to Y.-w.Z.), the 973 Prophase Project (2010CB535004 to Y.-w.Z.), and Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar of Fujian Province (2009J06022 to Y.-w.Z.). Y.-w.Z. is supported by the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Universities (NCET), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation.

Abbreviations used

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- AICD

APP intracellular domain

- APLP1

APP-like protein 1

- APLP2

APP-like protein 2

- APP

β–amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FAD

familiar Alzheimer’s disease

- KPI

Kunitz protease inhibitor

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- PS

presenilin

- PTB

phosphotyrosine binding

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the research reported herein.

References

- Acquati F, Accarino M, Nucci C, Fumagalli P, Jovine L, Ottolenghi S, Taramelli R. The gene encoding DRAP (BACE2), a glycosylated transmembrane protein of the aspartic protease family, maps to the down critical region. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ag CB. Generation of an Apoptotic Intracellular Peptide by gamma-Secretase Cleavage of Alzheimer's Amyloid Protein Precursor. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2000;2:289–301. doi: 10.3233/jad-2000-23-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn K, Shelton CC, Tian Y, Zhang X, Gilchrist ML, Sisodia SS, Li YM. Activation and intrinsic gamma-secretase activity of presenilin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013246107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmeppen HC, Prox J, Puig B, Kluth MA, Bernreuther C, Thurm D, Jorissen E, Petrowitz B, Bartsch U, De Strooper B, Saftig P, Glatzel M. Lack of a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase ADAM10 leads to intracellular accumulation and loss of shedding of the cellular prion protein in vivo. Mol. Neurodegener. 2011;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves da Costa C, Sunyach C, Pardossi-Piquard R, Sevalle J, Vincent B, Boyer N, Kawarai T, Girardot N, St George-Hyslop P, Checler F. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase-mediated control of p53-associated cell death in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6377–6385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0651-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek SH, Ohgi KA, Rose DW, Koo EH, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-kappaB and beta-amyloid precursor protein. Cell. 2002;110:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmans BA, Shariati SA, Habets RL, Verstreken P, Schoonjans L, Muller U, Dotti CG, De Strooper B. Neurons generated from APP/APLP1/APLP2 triple knockout embryonic stem cells behave normally in vitro and in vivo: lack of evidence for a cell autonomous role of the amyloid precursor protein in neuronal differentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:399–406. doi: 10.1002/stem.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Brouillet E, Caille I, Bouillot C, Cole GM, Prochiantz A, Allinquant B. A short cytoplasmic domain of the amyloid precursor protein induces apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2001;18:503–511. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer T, Cao X, Sudhof TC, Liu X. Regulation of APP-dependent transcription complexes by Mint/X11s: differential functions of Mint isoforms. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7340–7351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07340.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate A-beta 1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron. 1996;17:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordji K, Becerril-Ortega J, Nicole O, Buisson A. Activation of extrasynaptic, but not synaptic, NMDA receptors modifies amyloid precursor protein expression pattern and increases amyloid-ss production. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:15927–15942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3021-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg JP, Ooi J, Levy E, Margolis B. The phosphotyrosine interaction domains of X11 and FE65 bind to distinct sites on the YENPTY motif of amyloid precursor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6229–6241. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassler SL, Gray MD, Sopher BL, Hu Q, Hearn MG, Pham DG, Dinulos MB, Fukuchi KI, Sisodia SS, Miller MA. cDNA cloning and chromosome mapping of the human Fe65 gene: interaction of the conserved cytoplasmic domains of the human -amyloid precursor protein and its homologues with the mouse Fe65 protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:1589. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick D, Soreghan B, Kwon M, Kosmoski J, Knauer M, Henschen A, Yates J, Cotman C, Glabe C. Assembly and aggregation properties of synthetic Alzheimer's A4/beta amyloid peptide analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum JD, Liu KN, Luo Y, Slack JL, Stocking KL, Peschon JJ, Johnson RS, Castner BJ, Cerretti DP, Black RA. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme is involved in regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of the Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27765–27767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Wang Y, McCarthy D, Wen H, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Wong PC. BACE1 is the major beta-secretase for generation of Abeta peptides by neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:233–234. doi: 10.1038/85064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille I, Allinquant B, Dupont E, Bouillot C, Langer A, Muller U, Prochiantz A. Soluble form of amyloid precursor protein regulates proliferation of progenitors in the adult subventricular zone. Development. 2004;131:2173–2181. doi: 10.1242/dev.01103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC. Dissection of amyloid-beta precursor protein-dependent transcriptional transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24601–24611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantry A, Glynn P. A novel metalloproteinase originally isolated from brain myelin membranes is present in many tissues. Biochem. J. 1990;268:245–248. doi: 10.1042/bj2680245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Gutierrez L, Tolia A, Maes E, Li T, Wong PC, de Strooper B. Glu(332) in the Nicastrin ectodomain is essential for gamma-secretase complex maturation but not for its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20096–20105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YZ. APP induces neuronal apoptosis through APP-BP1-mediated downregulation of beta-catenin. Apoptosis. 2004;9:415–422. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000031447.05354.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse MA, Sunyach C, Lefranc-Jullien S, Postina R, Vincent B, Checler F. The disintegrin ADAM9 indirectly contributes to the physiological processing of cellular prion by modulating ADAM10 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40624–40631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson EJ, Paliga K, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. What the evolution of the amyloid protein precursor supergene family tells us about its function. Neurochem. Int. 2000;36:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal AS, Morais VA, Pierson TC, Pijak DS, Carlin D, Lee VM, Doms RW. Membrane topology of gamma-secretase component PEN-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20117–20123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahms SO, Hoefgen S, Roeser D, Schlott B, Guhrs KH, Than ME. Structure and biochemical analysis of the heparin-induced E1 dimer of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5381–5386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911326107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson GR, Seabrook GR, Zheng H, Smith DW, Graham S, O'Dowd G, Bowery BJ, Boyce S, Trumbauer ME, Chen HY, Van der Ploeg L. H, Sirinathsinghji DJ. Age-related cognitive deficits, impaired long-term potentiation and reduction in synaptic marker density in mice lacking the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Neuroscience. 1999;90:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoviel DB, Hadjantonakis AK, Ikeda M, Zheng H, Hyslop PS, Bernstein A. Mice lacking both presenilin genes exhibit early embryonic patterning defects. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2801–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C, Yu X, Prada CM, Perez-tur J, Hutton M, Buee L, Harigaya Y, Yager D, Morgan D, Gordon MN, Holcomb L, Refolo L, Zenk B, Hardy J, Younkin S. Increased amyloid-beta42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature. 1996;383:710–713. doi: 10.1038/383710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumanchin-Njock C, Alves da Costa C. A, Mercken L, Pradier L, Checler F. The caspase-derived C-terminal fragment of betaAPP induces caspase-independent toxicity and triggers selective increase of Abeta42 in mammalian cells. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:1153–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehehalt R, Michel B, De Pietri Tonelli D, Zacchetti D, Simons K, Keller P. Splice variants of the beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme BACE1 in human brain and pancreas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293:30–37. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch FS, Keim PS, Beattie EC, Blacher RW, Culwell AR, Oltersdorf T, McClure D, Ward PJ. Cleavage of amyloid beta peptide during constitutive processing of its precursor. Science. 1990;248:1122–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.2111583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan R, Swindells M, Overington J, Weir M. Nicastrin, a presenilin-interacting protein, contains an aminopeptidase/transferrin receptor superfamily domain. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:213–214. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan M, Schnitzler CE, Vasilieva N, Leung D, Choe H. BACE2, a beta -secretase homolog, cleaves at the beta site and within the amyloid-beta region of the amyloid-beta precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9712–9717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160115697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa DJ, Morris JA, Ma L, Kandpal G, Chen E, Li YM, Austin CP. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase activity modulates neurite outgrowth. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:49–60. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore F, Zambrano N, Minopoli G, Donini V, Duilio A, Russo T. The regions of the Fe65 protein homologous to the phosphotyrosine interaction/phosphotyrosine binding domain of Shc bind the intracellular domain of the Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:30853–30856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortna RR, Crystal AS, Morais VA, Pijak DS, Lee VM, Doms RW. Membrane topology and nicastrin-enhanced endoproteolysis of APH-1, a component of the gamma-secretase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3685–3693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R, McGrath G, Zhang J, Ruddy DA, Sym M, Apfeld J, Nicoll M, Maxwell M, Hai B, Ellis MC, Parks AL, Xu W, Li J, Gurney M, Myers RL, Himes CS, Hiebsch R, Ruble C, Nye JS, Curtis D. aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, gamma-secretase cleavage of betaAPP, and presenilin protein accumulation. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Barger SW, Blalock EM, Mattson MP. Activation of K+ channels and suppression of neuronal activity by secreted beta-amyloid-precursor protein. Nature. 1996a;379:74–78. doi: 10.1038/379074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Sopher BL, Rydel RE, Begley JG, Pham DG, Martin GM, Fox M, Mattson MP. Increased Activity Regulating and Neuroprotective Efficacy of Secretase Derived Secreted Amyloid Precursor Protein Conferred by a C Terminal Heparin Binding Domain. J. Neurochem. 1996b;67:1882–1896. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67051882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakhar Koppole N, Hundeshagen P, Mandl C, Weyer SW, Allinquant B, Muller U, Ciccolini F. Activity requires soluble amyloid precursor protein to promote neurite outgrowth in neural stem cell derived neurons via activation of the MAPK pathway. Eur. J.Neurosci. 2008;28:871–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Gorostiza OF, Banwait S, Ataie M, Logvinova AV, Sitaraman S, Carlson E, Sagi SA, Chevallier N, Jin K, Greenberg DA, Bredesen DE. Reversal of Alzheimer's-like pathology and behavior in human APP transgenic mice by mutation of Asp664. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7130–7135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509695103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandy S, Czernik AJ, Greengard P. Phosphorylation of Alzheimer disease amyloid precursor peptide by protein kinase C and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6218–6221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Petrucelli L. The role of tau in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersbacher MT, Kim DY, Bhattacharyya R, Kovacs DM. Identification of BACE1 cleavage sites in human voltage-gated sodium channel beta 2 subunit. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010;5:61. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal K, Vogt DL, Liang M, Shen Y, Lamb BT, Pimplikar SW. Alzheimer's disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18367–18372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907652106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giliberto L, Acker CM, Davies P, D'Adamio L. Transgenic Expression of the Amyloid- Precursor Protein-Intracellular Domain Does Not Induce Alzheimer's Disease-like Traits In Vivo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giliberto L, Zhou D, Weldon R, Tamagno E, De Luca P, Tabaton M, D'Adamio L. Evidence that the Amyloid beta Precursor Protein-intracellular domain lowers the stress threshold of neurons and has a "regulated" transcriptional role. Mol. Neurodegener. 2008;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid R, Kilger E, Willem M, Vassallo N, Kostka M, Bornhovd C, Reichert AS, Kretzschmar HA, Haass C, Herms J. Amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain modulates cellular calcium homeostasis and ATP content. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:1264–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P, Dou F, Li F, Zhang X, Zhang YW, Zheng H, Lipton SA, Xu H, Liao FF. Suppression of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activation by amyloid precursor protein: a novel excitoprotective mechanism involving modulation of tau phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:11542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3831-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, Umans L, Lubke T, Lena Illert A, von Figura K, Saftig P. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2615–2624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass MR, Yankner BA. A {gamma}-secretase-independent mechanism of signal transduction by the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:36895–36904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502861200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heber S, Herms J, Gajic V, Hainfellner J, Aguzzi A, Rulicke T, von Kretzschmar H, von Koch C, Sisodia S, Tremml P, Lipp HP, Wolfer DP, Muller U. Mice with combined gene knock-outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7951–7963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07951.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herms J, Anliker B, Heber S, Ring S, Fuhrmann M, Kretzschmar H, Sisodia S, Muller U. Cortical dysplasia resembling human type 2 lissencephaly in mice lacking all three APP family members. EMBO J. 2004;23:4106–4115. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog V, Kirfel G, Siemes C, Schmitz A. Biological roles of APP in the epidermis. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 2004;83:613–624. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitt DB, Jaramillo CT, Chetkoyich MD, Vassar R. BACE1mice exhibit seizure activity that does not correlate with sodium channel level or axonal localization. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Sudhof TC. Binding of F-spondin to amyloid-beta precursor protein: a candidate amyloid-beta precursor protein ligand that modulates amyloid-beta precursor protein cleavage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308655100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger RM, McLean CA, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Evin G. Increased expression of the amyloid precursor beta-secretase in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2002;51:783–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Toneff T, Bogyo M, Greenbaum D, Medzihradszky KF, Neveu J, Lane W, Hook G, Reisine T. Inhibition of cathepsin B reduces beta-amyloid production in regulated secretory vesicles of neuronal chromaffin cells: evidence for cathepsin B as a candidate beta-secretase of Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:931–940. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard L, Lu X, Mitchell S, Griffiths S, Glynn P. Molecular cloning of MADM: a catalytically active mammalian disintegrin-metalloprotease expressed in various cell types. Biochem. J. 1996;317(Pt 1):45–50. doi: 10.1042/bj3170045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BW, Lanier LM, Frank R, Gertler FB, Cooper JA. The disabled 1 phosphotyrosine-binding domain binds to the internalization signals of transmembrane glycoproteins and to phospholipids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5179–5188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Hicks CW, He W, Wong P, Macklin WB, Trapp BD, Yan R. Bace1 modulates myelination in the central and peripheral nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1520–1525. doi: 10.1038/nn1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain I, Powell DJ, Howlett DR, Chapman GA, Gilmour L, Murdock PR, Tew DG, Meek TD, Chapman C, Schneider K, Ratcliffe SJ, Tattersall D, Testa TT, Southan C, Ryan DM, Simmons DL, Walsh FS, Dingwall C, Christie G. ASP1 (BACE2) cleaves the amyloid precursor protein at the beta-secretase site. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;16:609–619. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima K, Ando K, Takeda S, Satoh Y, Seki T, Itohara S, Greengard P, Kirino Y, Nairn AC, Suzuki T. Neuron-specific phosphorylation of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein by cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:1085–1091. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura T, Ogryzko VV, Grigoriev M, Groisman R, Wang J, Horikoshi M, Scully R, Qin J, Nakatani Y. Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell. 2000;102:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata H, Nakamura Y, Hayakawa A, Takata H, Suzuki T, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N. A scaffold protein JIP-1b enhances amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation by JNK and its association with kinesin light chain 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22946–22955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT., Jr The carboxy terminus of the beta amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaether C, Capell A, Edbauer D, Winkler E, Novak B, Steiner H, Haass C. The presenilin C-terminus is required for ER-retention, nicastrin-binding and gamma-secretase activity. EMBO J. 2004;23:4738–4748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Stokin GB, Yang Z, Xia CH, Goldstein LS. Axonal transport of amyloid precursor protein is mediated by direct binding to the kinesin light chain subunit of kinesin-I. Neuron. 2000;28:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Muller-Hill B. Differential splicing of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 precursor RNA in rat tissues: PreA4(695) mRNA is predominantly produced in rat and human brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;166:1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90992-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Kim EM, Lee JP, Park CH, Kim S, Seo JH, Chang KA, Yu E, Jeong SJ, Chong YH. C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein exert neurotoxicity by inducing glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta expression. FASEB J. 2003;17:1951. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0106fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike H, Tomioka S, Sorimachi H, Saido TC, Maruyama K, Okuyama A, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Ohno S, Suzuki K, Ishiura S. Membrane-anchored metalloprotease MDC9 has an alpha-secretase activity responsible for processing the amyloid precursor protein. Biochem. J. 1999;343(Pt 2):371–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojro E, Gimpl G, Lammich S, Marz W, Fahrenholz F. Low cholesterol stimulates the nonamyloidogenic pathway by its effect on the alpha -secretase ADAM 10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5815–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081612998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Schroeter EH, Weintraub H, Nye JS. Signal transduction by activated mNotch: importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn PH, Wang H, Dislich B, Colombo A, Zeitschel U, Ellwart JW, Kremmer E, Rossner S, Lichtenthaler SF. ADAM10 is the physiologically relevant, constitutive alpha-secretase of the amyloid precursor protein in primary neurons. EMBO J. 2010;29:3020–3032. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird FM, Cai H, Savonenko AV, Farah MH, He K, Melnikova T, Wen H, Chiang HC, Xu G, Koliatsos VE, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Lee HK, Wong PC. BACE1, a major determinant of selective vulnerability of the brain to amyloid-beta amyloidogenesis, is essential for cognitive, emotional, and synaptic functions. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:11693–11709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2766-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammich S, Kojro E, Postina R, Gilbert S, Pfeiffer R, Jasionowski M, Haass C, Fahrenholz F. Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3922–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Fraering PC, Ostaszewski BL, Ye W, Kimberly WT, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ. Assembly of the gamma-secretase complex involves early formation of an intermediate subcomplex of Aph-1 and nicastrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37213–37222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sunnarborg SW, Hinkle CL, Myers TJ, Stevenson MY, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Gerhart MJ, Paxton RJ, Black RA, Chang A, Jackson LF. TACE/ADAM17 processing of EGFR ligands indicates a role as a physiological convertase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;995:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SF, Shah S, Li H, Yu C, Han W, Yu G. Mammalian APH-1 interacts with presenilin and nicastrin and is required for intramembrane proteolysis of amyloid-beta precursor protein and Notch. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45013–45019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, Yu CE, Jondro PD, Schmidt SD, Wang K, et al. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer's disease locus. Science. 1995;269:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.7638622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Ma G, Cai H, Price DL, Wong PC. Nicastrin is required for assembly of presenilin/gamma-secretase complexes to mediate Notch signaling and for processing and trafficking of beta-amyloid precursor protein in mammals. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3272–3277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Koelsch G, Wu S, Downs D, Dashti A, Tang J. Human aspartic protease memapsin 2 cleaves the beta-secretase site of beta-amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1456–1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Zerbinatti CV, Zhang J, Hoe HS, Wang B, Cole SL, Herz J, Muglia L, Bu G. Amyloid precursor protein regulates brain apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism through lipoprotein receptor LRP1. Neuron. 2007;56:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Zhang H, You X, Liao FF, Xu H. Intracellular trafficking of presenilin 1 is regulated by -amyloid precursor protein and phospholipase D1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808497200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Paganetti PA, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Mautino J, Vigo FS, Sommer B, Yankner BA. Amyloid beta interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:460–464. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco FC, Galvan V, Fombonne J, Corset V, Llambi F, Muller U, Bredesen DE, Mehlen P. Netrin-1 interacts with amyloid precursor protein and regulates amyloid-beta production. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:655–663. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Soriano S, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Caspase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein modulates amyloid protein toxicity. J. Neurochem. 2003a;87:733–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Shaked GM, Masliah E, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Amyloid protein toxicity mediated by the formation of amyloid protein precursor complexes. Ann. Neurol. 2003b;54:781–789. doi: 10.1002/ana.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Rabizadeh S, Chandra S, Shayya RE, Ellerby LM, Ye X, Salvesen GS, Koo EH, Bredesen DE. A second cytotoxic proteolytic peptide derived from amyloid beta-protein precursor. Nat. Med. 2000;6:397–404. doi: 10.1038/74656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo WJ, Wang H, Li H, Kim BS, Shah S, Lee HJ, Thinakaran G, Kim TW, Yu G, Xu H. PEN-2 and APH-1 coordinately regulate proteolytic processing of presenilin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7850–7854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Bolon B, Kahn S, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Denis P, Fan W, Kha H, Zhang J, Gong Y, Martin L, Louis JC, Yan Q, Richards WG, Citron M, Vassar R. Mice deficient in BACE1, the Alzheimer's beta-secretase, have normal phenotype and abolished beta-amyloid generation. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:231–232. doi: 10.1038/85059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin D, Cj Miller C. The intracellular cytoplasmic domain of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein interacts with phosphotyrosine-binding domain proteins in the yeast two-hybrid system. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, Li T, Price DL, Wong PC. APH-1a is the principal mammalian APH-1 isoform present in gamma-secretase complexes during embryonic development. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:192–198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3814-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Zhao YB, Kwak YD, Yang Z, Thompson R, Luo Z, Xu H, Liao FF. Statin's excitoprotection is mediated by sAPP and the subsequent attenuation of calpain-induced truncation events, likely via rho-ROCK signaling. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6150-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira A, Pommet JM, Prochiantz A, Allinquant B. SET protein (TAF1beta, I2PP2A) is involved in neuronal apoptosis induced by an amyloid precursor protein cytoplasmic subdomain. FEBS. J. 2005;19:1905–1907. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3839fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Sterling NR, Lo AC, Sisodia SS, Koo EH. Trafficking of cell-surface beta-amyloid precursor protein: evidence that a sorting intermediate participates in synaptic vesicle recycling. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:140–151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00140.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Matsuda Y, D'Adamio L. Amyloid beta protein precursor (AbetaPP), but not AbetaPP-like protein 2, is bridged to the kinesin light chain by the scaffold protein JNK-interacting protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38601–38606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Matsuda Y, Snapp EL, D'Adamio L. Maturation of BRI2 generates a specific inhibitor that reduces APP processing at the plasma membrane and in endocytic vesicles. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;32:1400–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Yasukawa T, Homma Y, Ito Y, Niikura T, Hiraki T, Hirai S, Ohno S, Kita Y, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Yamamoto T, Kyriakis JM, Nishimoto I. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-interacting protein-1b/islet-brain-1 scaffolds Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein with JNK. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:6597–6607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06597.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Cellular actions of beta-amyloid precursor protein and its soluble and fibrillogenic derivatives. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:1081–1132. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Cheng B, Culwell AR, Esch FS, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. Evidence for excitoprotective and intraneuronal calcium-regulating roles for secreted forms of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Neuron. 1993;10:243–254. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90315-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Gonzalez M, Perez-Pinera P, Martinez-Rivera M, Calatayud MT, Blazquez Menes B. APP processing and the APP-KPI domain involvement in the amyloid cascade. Neurodegener. Dis. 2005;2:277–283. doi: 10.1159/000092315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meziane H, Dodart JC, Mathis C, Little S, Clemens J, Paul SM, Ungerer A. Memory-enhancing effects of secreted forms of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in normal and amnestic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:12683–12688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Farr SA, Banks WA, Johnson SN, Yamada KA, Xu L. A physiological role for amyloid-beta protein: enhancement of learning and memory. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2008;19:441–449. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, Bickett DM, Burkhart W, Carter HL, Chen WJ, Clay WC, Didsbury JR, Hassler D, Hoffman CR, Kost TA, Lambert MH, Leesnitzer MA, McCauley P, McGeehan G, Mitchell J, Moyer M, Pahel G, Rocque W, Overton LK, Schoenen F, Seaton T, Su JL, Becherer JD, et al. Cloning of a disintehrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385:733–736. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Steiner S, Zhou Y, Arai H, Roberson ED, Sun B, Chen J, Wang X, Yu G, Esposito L, Mucke L, Gan L. Antiamyloidogenic and neuroprotective functions of cathepsin B: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2006;51:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya T, Suzuki T. Role of APP phosphorylation in FE65-dependent gene transactivation mediated by AICD. Genes. Cells. 2006;11:633–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimura M, Isoo N, Takasugi N, Tsuruoka M, Ui-Tei K, Saigo K, Morohashi Y, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T. Aph-1 contributes to the stabilization and trafficking of the gamma-secretase complex through mechanisms involving intermolecular and intramolecular interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12967–12975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev A, McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD, Tessier-Lavigne M. APP binds DR6 to trigger axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases. Nature. 2009;457:981–989. doi: 10.1038/nature07767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Nishimura I, Uetsuki T, Kuwako K, Hara T, Kawakami T, Aimoto S, Yoshikawa K. Cell death induced by a caspase-cleaved transmembrane fragment of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:199–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norstrom EM, Zhang C, Tanzi R, Sisodia SS. Identification of NEEP21 as a ss-amyloid precursor protein-interacting protein in vivo that modulates amyloidogenic processing in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:15677–15685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4464-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Sametsky EA, Younkin LH, Oakley H, Younkin SG, Citron M, Vassar R, Disterhoft JF. BACE1 deficiency rescues memory deficits and cholinergic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;41:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa I, Takamura C, Morimoto T, Ishiguro M, Kohsaka S. Amino-terminal region of secreted form of amyloid precursor protein stimulates proliferation of neural stem cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:1907–1913. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T, Li Y, Kikuchi H, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Nakagawara A. The intracellular domain of the amyloid precursor protein (AICD) enhances the p53-mediated apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;351:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi-Piquard R, Petit A, Kawarai T, Sunyach C, Alves da Costa C, Vincent B, Ring S, D'Adamio L, Shen J, Muller U, St George Hyslop P, Checler F. Presenilin-dependent transcriptional control of the Abeta-degrading enzyme neprilysin by intracellular domains of betaAPP and APLP. Neuron. 2005;46:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Gimbel DA, GrandPre T, Lee JK, Kim JE, Li W, Lee DH, Strittmatter SM. Alzheimer precursor protein interaction with the Nogo-66 receptor reduces amyloid-beta plaque deposition. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1386–1395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3291-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak SH, Bagshaw RD, Guiral M, Zhang S, Ackerley CA, Pak BJ, Callahan JW, Mahuran DJ. Presenilin-1, nicastrin, amyloid precursor protein, and gamma-secretase activity are co-localized in the lysosomal membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26687–26694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m304009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Johnson RS, Fitzner JN, Boyce RW, Nelson N, Kozlosky CJ, Wolfson MF, Rauch CT, Cerretti DP, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Black RA. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant LD, Boyle JP, Smith IF, Peers C, Pearson HA. The production of amyloid beta peptide is a critical requirement for the viability of central neurons. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5531–5535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postina R, Schroeder A, Dewachter I, Bohl J, Schmitt U, Kojro E, Prinzen C, Endres K, Hiemke C, Blessing M, Flamez P, Dequenne A, Godaux E, van Leuven F, Fahrenholz F. A disintegrin-metalloproteinase prevents amyloid plaque formation and hippocampal defects in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1456–1464. doi: 10.1172/JCI20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S, Jiang P, Guan XM, Singh G, Trumbauer ME, Yu H, Chen HY, Van de Ploeg L. H, Zheng H. Mutant human presenilin 1 protects presenilin 1 null mouse against embryonic lethality and elevates Abeta1–42/43 expression. Neuron. 1998;20:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Juan Z, Hien T, Marcel V, Karina R, Guojun B. LRP1 shedding in human brain: roles of ADAM10 and ADAM17. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009;4 doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring S, Weyer SW, Kilian SB, Waldron E, Pietrzik CU, Filippov MA, Herms J, Buchholz C, Eckman CB, Korte M, Wolfer DP, Muller UC. The secreted beta-amyloid precursor protein ectodomain APPs alpha is sufficient to rescue the anatomical, behavioral, and electrophysiological abnormalities of APP-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:7817–7826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1026-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Anderson J, Basi G, Bienkowski MJ, Branstetter DG, Chen KS, Freedman SB, Frigon NL, Games D, Hu K, Johnson-Wood K, Kappenman KE, Kawabe TT, Kola I, Kuehn R, Lee M, Liu W, Motter R, Nichols NF, Power M, Robertson DW, Schenk D, Schoor M, Shopp GM, Shuck ME, Sinha S, Svensson KA, Tatsuno G, Tintrup H, Wijsman J, Wright S, McConlogue L. BACE knockout mice are healthy despite lacking the primary beta-secretase activity in brain: implications for Alzheimer's disease therapeutics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1317–1324. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan de Silva HA, Jen A, Wickenden C, Jen LS, Wilkinson SL, Patel AJ. Cell-specific expression of beta-amyloid precursor protein isoform mRNAs and proteins in neurons and astrocytes. Brain. Res. Mol. Brain. Res. 1997;47:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati R, Sestan N, Scheinfeld MH, Berechid BE, Lopez PA, Meucci O, McGlade JC, Rakic P, D'Adamio L. The gamma-secretase-generated intracellular domain of -amyloid precursor protein binds Numb and inhibits Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102192599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KA, Pimplikar SW. Activation of GSK-3 and phosphorylation of CRMP2 in transgenic mice expressing APP intracellular domain. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:327–335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbrink R, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Beta A4-amyloid protein precursor mRNA isoforms without exon 15 are ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues including brain, but not in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:1510–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarah C, Robert V. The Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Mol. Neurodegener. 2007;2 doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre M, Steiner H, Fuchs K, Capell A, Multhaup G, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Haass C. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein at a site corresponding to the S3 cleavage of Notch. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Tanimura Y, Hirotani N, Saido TC, Morishima-Kawashima M, Ihara Y. Blocking the cleavage at midportion between gamma- and epsilon-sites remarkably suppresses the generation of amyloid beta-protein. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2907–2912. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Dohmae N, Qi Y, Kakuda N, Misonou H, Mitsumori R, Maruyama H, Koo EH, Haass C, Takio K, Morishima-Kawashima M, Ishiura S, Ihara Y. Potential link between amyloid beta-protein 42 and C-terminal fragment gamma 49–99 of beta-amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24294–24301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Chen G, Malkani S, Choi SY, Takahashi RH, Zhang D, Gouras GK, Kirkwood A, Morris RG, Shen J. Conditional inactivation of presenilin 1 prevents amyloid accumulation and temporarily rescues contextual and spatial working memory impairments in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6755–6764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1247-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter I, Ziv E. Kinetic properties of cathepsin D and BACE 1 indicate the need to search for additional beta-secretase candidate(s) Biol. Chem. 2008;389:313–320. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld MH, Roncarati R, Vito P, Lopez PA, Abdallah M, D'Adamio L. Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) interacting protein 1 (JIP1) binds the cytoplasmic domain of the Alzheimer's -amyloid precursor protein (APP) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird TD, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, Larson E, Levy-Lahad E, Viitanen M, Peskind E, Poorkaj P, Schellenberg G, Tanzi R, Wasco W, Lannfelt L, Selkoe D, Younkin S. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. The cell biology of beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:447–453. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serneels L, Dejaegere T, Craessaerts K, Horre K, Jorissen E, Tousseyn T, Hebert S, Coolen M, Martens G, Zwijsen A, Annaert W, Hartmann D, De Strooper B. Differential contribution of the three Aph1 genes to gamma-secretase activity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1719–1724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serneels L, Van Biervliet J, Craessaerts K, Dejaegere T, Horre K, Van Houtvin T, Esselmann H, Paul S, Schafer MK, Berezovska O, Hyman BT, Sprangers B, Sciot R, Moons L, Jucker M, Yang Z, May PC, Karran E, Wiltfang J, D'Hooge R, De Strooper B. gamma-Secretase heterogeneity in the Aph1 subunit: relevance for Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2009;324:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1171176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Lee SF, Tabuchi K, Hao YH, Yu C, LaPlant Q, Ball H, Dann CE, 3rd Sudhof T, Yu G. Nicastrin functions as a gamma-secretase-substrate receptor. Cell. 2005;122:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Walsh DM. Alzheimer's disease: synaptic dysfunction and Abeta. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009;4:48. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Bronson RT, Chen DF, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Tonegawa S. Skeletal and CNS defects in Presenilin-1-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89:629–639. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, Tsuda T, Mar L, Foncin JF, Bruni AC, Montesi MP, Sorbi S, Rainero I, Pinessi L, Nee L, Chumakov I, Pollen D, Brookes A, Sanseau P, Polinsky RJ, Wasco W, Da Silva H. A, Haines JL, Perkicak-Vance MA, Tanzi RE, Roses AD, Fraser PE, Rommens JM, St George-Hyslop P. H. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]