Abstract

The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex viruses (HSV) is essential for virulence. Accordingly, an HSV mutant lacking γ134.5 is attenuated in vivo. Despite its vaccine potential, the mechanism by which the γ134.5 null mutant triggers protective immunity is unknown. In this report we show that vaccination with the γ134.5 null mutant protects against lethal challenge from wild-type virus via IκB kinase in dendritic cells (DCs), which sense virus-associated molecular patterns. Unlike mock-treated DCs, DCs primed with the γ134.5 null mutant ex vivo mediate resistance to wild-type HSV after adoptive transfer into naïve mice. Furthermore, the γ134.5 null mutant activates IκB kinase, which facilitates p65/RelA phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, resulting in DC maturation. While unable to produce infectious virus in DCs, this mutant virus expresses early and late genes. In its abortive infection, the γ134.5 null mutant induces protective immunity more effectively in CD8+ DCs than in CD8− DCs. This is mirrored by a higher level of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-12 secretion by CD8+ DCs than CD8− DCs. Remarkably, inhibition of p65/RelA phosphorylation or nuclear translocation in CD8+ DCs disrupts protective immunity. These results suggest that engagement of the γ134.5 null mutant with CD8+ DCs elicits innate immunity to activate NF-κB, which translates into protective immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) are human pathogens responsible for a spectrum of diseases, including ocular lesions, genital herpes, and encephalitis (11). HSV infection is also a risk factor in HIV acquisition and transmission. Following infection, HSV initiates a lytic cycle in the mucosal tissues, where viral gene transcription, replication, assembly, and egress ensue. This is followed by a latency in sensory ganglia, where reactivation occurs intermittently, resulting in recurrent infections (11). In this process, HSV interacts with host cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), which capture, process, and present viral antigens. Upon maturation, DCs express high levels of costimulatory molecules. Additionally, DCs release inflammatory cytokines to induce T cell responses that restrict viral infection (1, 54, 68).

DCs detect HSV through multiple pathways (22, 48, 50). For example, plasmacytoid DCs detect HSV through Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), whereas conventional DCs sense virus via TLR-dependent and -independent pathways (22, 32, 48). It is thought that HSV proteins or RNA intermediates trigger conventional DCs (22, 48). Notably, a complex consisting of HSV glycoproteins B, D, H, and L stimulates DC maturation (50). On the other hand, HSV blocks DC activities (3, 26, 28, 52). In immature DCs, HSV type 1 (HSV-1) downregulates cell surface molecules and cytokines, impairing T cell activation (10, 26, 38, 44, 52). HSV-1 also induces apoptosis of DCs, whereas HSV-2 exerts this activity more rapidly (5, 26, 44). Further, HSV-1 perturbs mature DCs (28, 45), where it induces degradation of CD83 (28, 29). Moreover, HSV-1 reduces levels of chemokine receptors CCR7 and CXCR4, which impedes DC migration (45). Therefore, the interaction of HSV and DCs is a key step that dictates the outcome of viral infection.

We recently reported that unlike wild-type virus, an HSV mutant lacking γ134.5 stimulates DC activation (23). Relevant to this is the fact that the γ134.5 gene encodes a multifunctional protein. In infected cells, HSV-1 γ134.5 precludes the shutoff of protein synthesis mediated by the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) (9, 20, 21). It facilitates glycoprotein processing and viral egress (6, 25, 34). The γ134.5 protein also interacts with beclin 1 and inhibits autophagy (40). Additionally, the γ134.5 protein inhibits TANK binding kinase 1 and IκB kinase in the TLR pathways (24, 61). The precise role of γ134.5 is not fully understood, but its mutation attenuates HSV in vivo (4, 8, 33, 35, 43, 51, 56, 63). Of note, vaccination with the γ134.5 null mutant or its derivatives protects from lethal challenge with wild-type virus (41, 46, 55). These studies highlight the γ134.5 null mutant as a potential live attenuated vaccine. Similarly, this idea has been pursued with other HSV mutants. Examples are HSV recombinants lacking gH, gE, ICP0, ICP8, ICP10, or virion host shut-off (vhs) protein (15, 18, 19, 39, 62). While HSV mutants induce antibody and T cell responses upon vaccination (15, 18, 39, 62), the nature of innate immunity remains obscure.

This study was designed to investigate innate immunity elicited by the γ134.5 null mutant upon vaccination. We report that the γ134.5 null mutant induces protective immunity through IκB kinase in DCs. After adoptive transfer, DCs primed with the γ134.5 null mutant mediate resistance to lethal challenge. This parallels with NF-κB activation and DC maturation. Notably, the γ134.5 null mutant exerts its activity more effectively in CD8+ DCs than in CD8− DCs. Inhibition of NF-κB phosphorylation or nuclear translocation abrogates the protective effect. Thus, the interaction of the γ134.5 null mutant with CD8+ DCs activates NF-κB, which induces protective immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley Inc. and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in biosafety level 2 containment. Groups of 5-week-old mice were selected for this study. Experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Cells and viruses.

Myeloid DCs were generated as previously described (23). Briefly, bone marrow cells were removed from the tibia and femur bones of BALB/c mice. Following red blood cell lysis and washing, progenitor cells were plated in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Auckland, New Zealand) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 20 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Biosource, Camarillo, CA) in 6-well plates at 4 × 106/well. Cells were supplemented with fresh medium every other day. On day 8, DCs were positively selected for surface CD11c expression using magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) to give a >97% pure population of CD11c+ major histocompatibility complex class II-positive (MHC-II+) cells. DCs displayed low levels of CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHC class II molecules, which is characteristic of immature DCs. Purified CD11c+ DCs were cultured in fresh medium with FBS and GM-CSF and used in subsequent experiments. HSV-1(F) is a prototype HSV-1 strain used in this study (14). In recombinant virus R3616, a 1-kb fragment from the coding region of the γ134.5 gene was deleted (8).

Viral infection and DC transfer.

Purified CD11c+ DCs were plated in 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) or in 96-well round-bottom plates (5 × 104 cells/well) and infected with R3616 (1 or 5 PFU/cell). After 2 h of incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF. At different time points after infection, cells were harvested for analysis. For challenge analysis, mice were anesthetized and inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 105 PFU of R3616. Two weeks after virus inoculation, mice were intranasally challenged with 1 × 107 PFU of wild-type HSV-1(F) in 50 μl of PBS. Mice were monitored daily for overall health and sacrificed when symptoms of encephalitis appeared. For in vivo transfer analysis, single splenocyte suspensions were prepared. And CD11c+ DCs (2.0 × 106 cells/spleen) were isolated and purified by using the CD11c magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotech). The cells were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD11c+ and phycoerythrin (PE) anti-CD8 before sorting. CD11c+ CD8+ and CD11c+ CD8− cells were collected. The cells, with a purity of 96 to 98%, were transferred into naïve mice (5 × 106 cells/mouse) three times intraperitoneally. This was done on days 1, 3, and 5, respectively. On day 6 after the first transfer, the mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) and monitored for 3 weeks. For ex vivo analysis, CD11c+ DCs, CD8+ DCs, or CD8− DCs derived from bone marrow were mock infected or infected with R3616. At 12 h after infection, the cells were washed with PBS and then adoptively transferred into naïve mice (5 × 106/mouse) intraperitoneally. Mice were then subjected to challenge with wild-type HSV-1(F). For NF-κB inhibition assays, DCs were infected as described above in the presence of a peptide inhibitor, SN50 (50 μg/ml), or its control peptide, SN50m (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) (30). Cells were washed and harvested for in vivo or in vitro analysis.

Plaque assay.

To determine the titer of infectious virus, on day 5 after challenge with wild-type virus, the brain stems were collected from control and R3616-vaccinated groups (3 to 5 mice) and mechanically homogenized. Samples were serially diluted in 199v medium. Viral yields were titrated on Vero cells and normalized by tissue weight (number of PFU/mg).

Immunoblot analysis and ELISA.

To analyze protein expression, cells were harvested and solubilized in disruption buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 2.75% sucrose. Samples were then subjected to electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and reacted with an antibody against FLAG (Sigma), IκB kinase β (IKKβ) and phosphorylated IKKβ (p-IKKβ) (Santa Cruz Biotech, CA), p65/RelA and phosphorylated p65/RelA (p-p65/RelA) (Santa Cruz Biotech), or β-actin (Sigma). The membranes were reacted with either goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.). Supernatants of cell culture were collected, and levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-12 were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from R&D systems according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell fractionation assays.

Cells were lysed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.4% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) and kept on ice with gentle inversion. After brief centrifugation, the nuclei were pelleted and supernatants were collected. After washing, the nuclei were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.4% Nonidet P-40. The cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against p65/RelA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GRP78 (glucose-regulated protein 78; BD Transduction Laboratories) and with antibodies against histone H3 (Cell Signaling), respectively.

Flow cytometry.

Tests for cell surface markers CD11c, MHC-II, CD80, and CD86 on DCs were performed according to a standard protocol, with some modifications (23). Cells were blocked with 1 μl of Fcγ monoclonal antibody (MAb; 0.5 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C. After a one-time wash with PBS, nonpermeabilized cells were stained with isotype-matched antibodies, anti-CD11c-PE, anti-MHC-II–FITC, anti-CD80-FITC, and anti-CD86-FITC antibodies, for 30 min on ice with gentle shaking. All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Samples were processed and screened using a FACSCalibur fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), and data were analyzed with Cell Questpro software (BD).

To determine viral infectivity, CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs mock infected or infected with R3616 were processed as described previously (23). Cells were treated with permeabilizing buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), incubated with a MAb against HSV-1 ICP27 (Virusys, Sykesville, MD), and then reacted with a goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech, CA). ICP27 expression was evaluated by flow cytometry.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNAs from mock-infected or virus-infected DCs were used to synthesize cDNA as suggested by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR analysis was performed for ICP27, UL30, and UL44 with the SYBR green system, and all data are presented as relative expression units after normalization to 18S rRNA (24).

Statistics analysis.

The statistical significance of survival rates was determined by the log rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Viral titer data, cytokine production, and cell surface marker and RNA expression were evaluated by Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Immunization with the γ134.5 null mutant confers resistance to wild-type HSV-1 through dendritic cells.

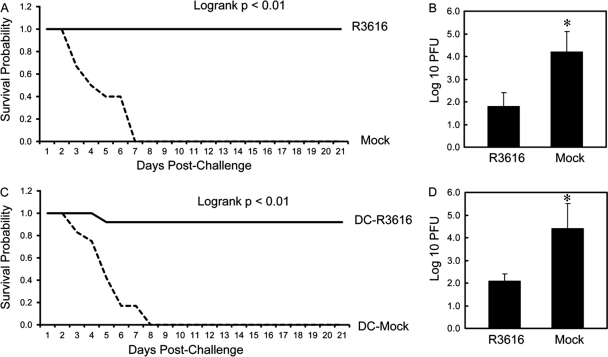

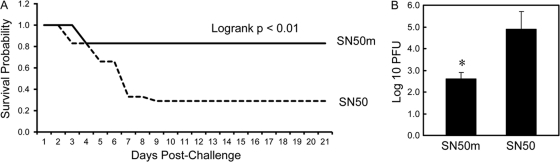

To establish an in vivo experimental model, we initially assessed the capacity of the γ134.5 null mutant to induce protective immunity in BALB/c mice. Similar to a previous observation (41), vaccination with the γ134.5 null mutant R3616 protected mice against lethal doses of wild-type HSV-1(F) and reduced viral replication in the brain (Fig. 1A and B). Compared to the mock-vaccinated control, no vaccinated mice displayed signs of encephalitis over a 21-day period. To explore the nature of observed phenotypes, we focused on DCs, which are sentinels of host immunity. As such, CD11c+ DCs isolated from R3616-vaccinated or mock-vaccinated mice were transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. Mice were challenged with wild-type HSV-1(F) intranasally on day 6 and monitored for 3 weeks. As indicated in Fig. 1C, most recipients of DCs from R3616-vaccinated mice were resistant to wild-type virus. Among mice examined, 91.6% survived. In sharp contrast, none of the recipients of DCs from mock-immunized mice survived after day 8 (Fig. 1C). Consistently, adoptive transfer of DCs from R3616-immunized mice drastically suppressed HSV-1(F) spread to the brain, with the titer being 1.1 × 102 PFU (Fig. 1D). On the other hand, the control mice failed to suppress HSV-1(F) infection, with the titer increasing to 2.5 × 104 PFU (Fig. 1D). Thus, DCs from mice vaccinated with the γ134.5 null mutant protect against lethal infection from wild-type virus.

Fig 1.

(A) Vaccination with the γ134.5 null mutant induces immunity to HSV-1. Mice were mock inoculated or inoculated with R3616 (1 × 105 PFU) intraperitoneally. Two weeks after immunization, the mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) intranasally and monitored over a 21-day period. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots (n = 24, log rank P < 0.01). (B) Replication of HSV-1(F). Viral yields in the brain were determined on day 5 after challenge with HSV-1(F) (n = 3 mock-vaccinated control mice, 3 vaccinated mice, P < 0.05). (C) The γ134.5 null mutant-induced protection requires dendritic cells. Mice were mock inoculated or inoculated with R3616 as described for panel A. CD11c+ DCs were isolated from spleen as described in Materials and Methods and were transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6 the mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) and monitored for an additional 21 days. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots (n = 24, log rank P < 0.01). (D) Replication of HSV-1(F). Viral yields in the brain were determined on day 5 after challenge with HSV-1(F) (n = 3 mock-vaccinated control mice, 3 vaccinated mice, P < 0.05).

Dendritic cells primed with the γ134.5 null mutant mediate protection that parallels with NF-κB activation.

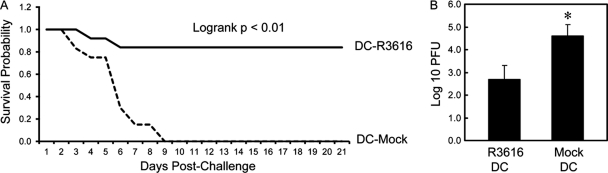

DCs recognize distinct components of HSV (22, 48, 50). When pulsed with a gD peptide ex vivo, DCs confer protective immunity upon adoptive transfer (58). To assess the γ134.5 null mutant, immature CD11c+ DCs derived from bone marrow were mock infected or infected with R3616 ex vivo for 12 h. After washing, the DCs were transferred into naïve mice and challenged with wild-type virus (1 × 107 PFU). As indicated in Fig. 2A, 83% of mice that received R3616-infected DCs were resistant to lethal challenge with HSV-1(F), whereas none of the mice harboring mock-infected DCs survived. In correlation, spread of HSV-1(F) into the brain was significantly suppressed after adoptive transfer of R3616-infected DCs compared to mock-infected DCs (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that DCs primed by the γ134.5 null mutant ex vivo initiate protective immunity.

Fig 2.

(A) DCs pulsed with the γ134.5 null mutant confer immunity to HSV-1(F). Immature CD11c+ DCs from bone marrow were mock infected or infected with R3616 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Cells were washed with PBS at 12 h after infection and adoptively transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6, mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) and monitored over a 21-day period. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots (n = 24, log rank P < 0.01). (B) Replication of HSV-1(F). Viral yields in the brain were determined on day 5 after challenge with HSV-1(F) (n = 3 mock-vaccinated control mice, 3 vaccinated mice, P < 0.05).

To examine the basis of the R3616-induced effect, we analyzed DC maturation, which is required for protective immunity (11). Unlike immature DCs, mature DCs have high expression of MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, immature CD11c+ DCs, either mock infected or infected with R3616, were assayed for the expression of these molecules. As shown in Fig. 3A, basal levels of MHC class II, CD86, and CD80 were seen in mock-infected DCs. Infection of immature DCs with R3616 dramatically enhanced the expression of these costimulatory molecules. Moreover, R3616 stimulated the production of cytokines in a dose-dependent manner. As illustrated in Fig. 3B, TNF-α expression remained at basal levels (46 pg/ml) in mock-infected cells. However, its expression increased sharply (>300 pg/ml) after infection with R3616. A similar expression profile was seen for IL-6 and IL-12. Thus, the γ134.5 null mutant stimulates DC maturation.

Fig 3.

The γ134.5 null mutant activates DCs ex vivo. Immature CD11c+ DCs were mocked infected or infected with R3616. At 12 h postinfection, cells were assayed for MHC-II, CD86, and CD80 expression by flow cytometry (A). Cell supernatants were assayed for expression of cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 (B). The data are from triplicate samples with standard deviations (P < 0.05).

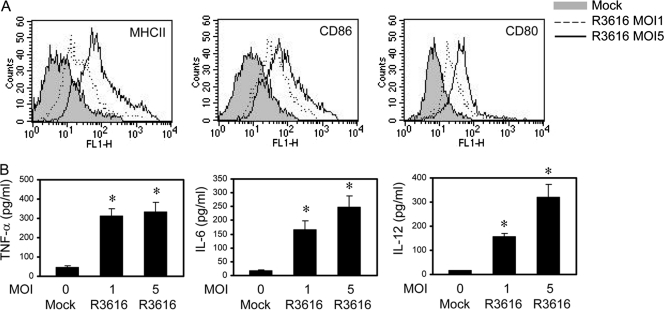

As DC maturation is coupled to NF-κB activation (49), we further assessed whether the γ134.5 null mutant had an impact on the NF-κB signaling pathway. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, while constitutively expressed, both IKKβ and p65/RelA remained unphosphorylated in mock-infected DCs. R3616 induced rapid phosphorylation of these proteins after infection. Consistently, p65/RelA was primarily located in the cytoplasm fraction in mock-infected cells (Fig. 4B). After R3616 infection, p65/RelA appeared in the nuclear fraction at all time points tested. R3616 infection had no effect on control proteins histone 3 in the nucleus and GRP78 in the cytoplasm, suggesting that R3616 infection activated IκB kinase and NF-κB. While unable to produce infectious virus, R3616 expressed ICP27, UL30, and UL44 mRNA in infected DCs (Fig. 4C and D). We conclude that the γ134.5 null mutant abortively infects DCs and activates NF-κB, which coincides with the induction of costimulatory molecules, cytokines, and protective immunity.

Fig 4.

(A) The γ134.5 null mutant triggers phosphorylation of p65/RelA and IKKβ. Immature CD11c+ DCs were mock infected or infected with R3616 (5 PFU per cell). At the indicated time points, lysates of cells were processed for Western blot (WB) analysis with antibodies against p65/RelA, phosphorylated p65/RelA, IKKβ, phosphorylated IKKβ, and β-actin. (B) The γ134.5 null mutant stimulates p65/RelA nuclear translocation in DCs. Cells were infected as described for panel A, and the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared for Western blot analysis with antibodies against p65, GRP78, and histone H3. (C) Growth of R3616 in DCs. Immature CD11c+ DCs were infected with R3616 as described above, and viral titers were measured at the indicated time points. (D) Viral gene expression. Immature CD11c+ DCs were infected with R3616, and the expression of ICP27, UL30, and UL44 was determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The results are from triplicate samples with standard deviations.

Inhibition of NF-κB activation in dendritic cells disrupts protective immunity elicited by the γ134.5 null mutant.

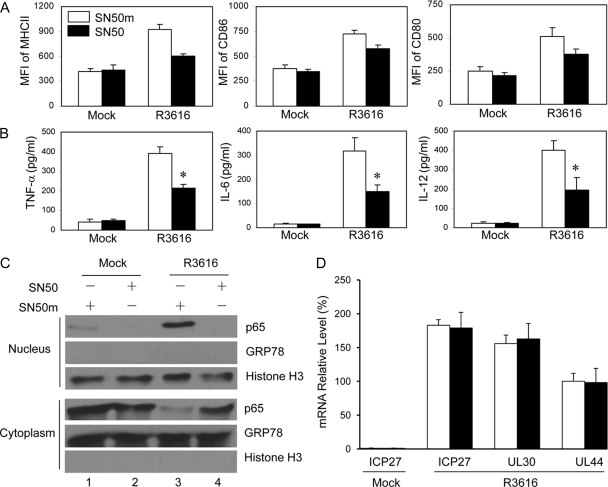

Based on the above-described analyses, we reasoned that the γ134.5 null mutant-induced NF-κB activation in DCs might be a determinant of protective immunity. To test this hypothesis, we carried out the NF-κB inhibition-coupled adoptive transfer assays. Immature CD11c+ DCs were infected with R3616 in the presence of a cell-permeant peptide NF-κB inhibitor, SN50, or its control peptide, SN50m (30). At 12 h after infection, cells were washed and adoptively transferred into naïve mice for challenge analysis. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, the majority of mice that received DCs with the NF-κB inhibitor did not survive after challenge with wild-type HSV-1(F). In this treatment group, only 25% of the animals were protected. However, most mice that received DCs with a control inhibitor survived HSV-1(F) challenge. Eighty-three percent of animals in this treatment group were protected. Concordant with these results, the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 enhanced viral spread to the brain after HSV-1(F) infection compared to the control inhibitor SN50m, with the titer reaching 8 × 104 PFU on day 5 (Fig. 5B). Thus, the γ134.5 null mutant-induced protective immunity is impaired by the NF-κB inhibitor.

Fig 5.

(A) Inhibition of NF-κB attenuates the γ134.5 null mutant-induced protective immunity. Immature CD11c+ DCs were infected with R3616 in the presence of a peptide inhibitor of NF-κB, SN50, or a control peptide, SN50m (30). At 12 h after infection, cells were transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6, mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) and monitored over a 21-day period. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots (n) = 24, log rank P < 0.01). (B) Replication of HSV-1(F). Viral yields in the brain were determined on day 5 after challenge with HSV-1(F) (n = 5 mock-vaccinated control mice, 5 vaccinated mice (P < 0.05).

To further evaluate the effect of the NF-κB inhibitor, we assessed DC maturation by R3616 ex vivo. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, unlike mock infection, R3616 infection stimulated the expression of MHC-II, CD80, CD86, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 in the presence of the control, SN50m. Addition of SN50 resulted in lower levels of costimulatory molecules and cytokines. It seems that the inhibitory effect by the NF-κB inhibitor was more drastic on the production of cytokines than on costimulatory molecule expression. Notably, the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 but not the control, SN50m, effectively blocked nuclear translocation of p65/RelA (Fig. 6C). Nevertheless, treatment with SN50 or SN50m had no effect on viral gene expression where R3616 expressed ICP27, UL30, and UL44 genes (Fig. 6D), suggesting that SN50 directly inhibited NF-κB activation. These results argue that NF-κB activation in DCs by the γ134.5 null mutant is essential to induce protective immunity against HSV-1 infection in vivo.

Fig 6.

The NF-κB inhibitor inhibits DC activation by the γ134.5 null mutant. Immature CD11c+ DCs were mock infected or infected with R3616 in the presence of SN50 or SN50m. At 12 h postinfection, cells were stained for the expression of MHC-II, CD86, and CD80 by flow cytometry (A). MFI, median fluorescence intensity. Cell supernatants were assayed for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 (B). *, P < 0.05. The cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared and samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against p65/RelA, GRP78, and histone H3 (C). The data are representative of results from two independent experiments. (D) Effect of NF-κB inhibitor on viral gene expression. DCs were mock infected or infected with R3616 as described for panel A. The expression of ICP27, UL30, and UL44 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR, with standard deviations among triplicate samples.

The γ134.5 null mutant exerts differential effects through CD8+ and CD8− dendritic cells.

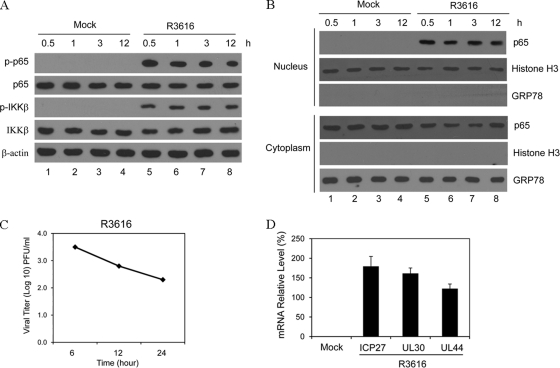

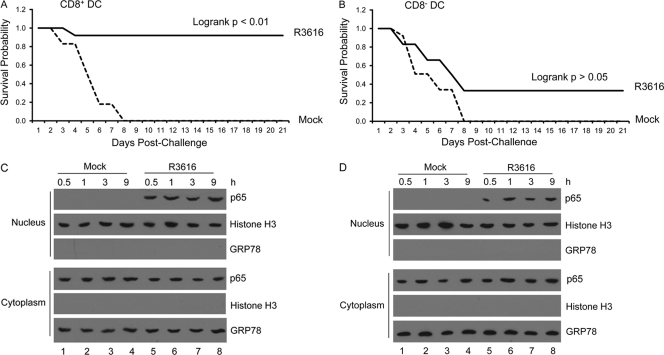

Conventional DC subsets can generally be categorized as CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs. To investigate how the γ134.5 null mutant exerted its effect, we analyzed CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs derived from bone marrow (>98% purity). Cells were either mock infected or infected with R3616 for 12 h. After washing, cells were transferred into naïve mice for challenge assays. As shown in Fig. 7A, 91.6% of mice that received R3616-infected CD8+ DCs survived after HSV-1(F) challenge. As expected, none of the mice that received mock-infected CD8+ DCs were viable beyond day 8. Interestingly, only 33.3% of mice that received R3616-infected CD8− DCs survived lethal challenge (Fig. 7B). A large fraction of mice within this treatment group did not survive beyond day 8. This lack of protection resembled the phenotype seen in mice receiving mock-infected CD8− DCs. Hence, CD8+ DCs confer protection more effectively than CD8− DCs after priming by the γ134.5 null mutant ex vivo.

Fig 7.

Effects of DC subsets on the γ134.5 null mutant-induced protective immunity. Immature CD11c+ CD8+ and CD11c+ CD8− DCs were isolated as described in Materials and Methods. CD11c+ CD8+ (A) or CD11c+ CD8− (B) DCs were mocked infected or infected with R3616 (5 PFU per cell). At 12 h after infection, cells were transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6, mice (n = 24) were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) and monitored over a 21-day period. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots. The γ134.5 null mutant stimulates p65/RelA nuclear translocation in CD11c+ CD8+ (C) and CD11c+ CD8− (D) DCs. Cells were infected as described above, and the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against p65 and GRP78 and with antibodies against histone H3, respectively. The data are representative of results from three independent experiments.

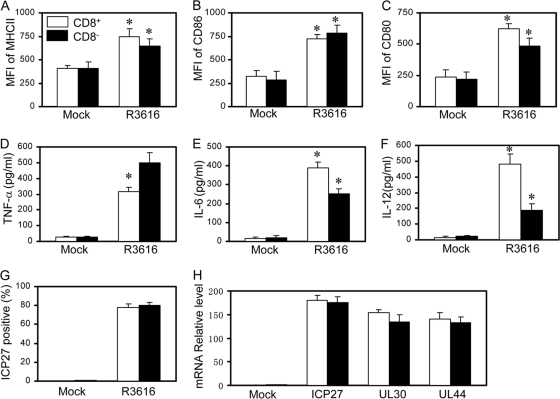

To understand the observed differences, we examined the status of NF-κB activation ex vivo. As shown in Fig. 7C and D, R3616 induced nuclear translocation of p65/RelA both in CD8+ DCs and in CD8− DCs. Next, we evaluated DC maturation. As illustrated in Fig. 8A to C, in response to R3616 infection, CD8+ DCs as well as CD8− DCs exhibited enhanced expression of MHC II, CD80, and CD86 at comparable levels. Nonetheless, CD8+ DCs secreted a higher level of IL-6 and IL-12, whereas CD8− DCs expressed more TNF-α (Fig. 8D to F). Under these conditions, R3616 infected CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs equally well, with approximately 80% infectivity, as revealed by FACS analysis of ICP27 (Fig. 8G). As infection continued, R3616 expressed comparable levels of ICP27, UL30, and UL44 in CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis (Fig. 8H). Therefore, although it activates NF-κB in CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs, the γ134.5 null mutant induces cytokine expression differentially.

Fig 8.

The γ134.5 null mutant triggers DC subsets differentially. Immature CD11c+ CD8+ and CD11c+ CD8− DCs were mocked infected or infected with R3616 (5 PFU per cell). At 12 h after infection, cells were assayed for MHC-II (A), CD86 (B), and CD80 (C) expression by flow cytometry. Cell supernatants were assayed for expression of cytokines TNF-α (D), IL-6 (E), and IL-12 (F). (G) Viral infectivity was determined by examining ICP27 expression as described in Materials and Methods. (H) The expression of ICP27, UL30, and UL44 in DCs infected with R3616 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The results are from triplicate samples with standard deviations (*, P < 0.05).

The γ134.5 null mutant-induced immunity requires NF-κB activation in CD8+ dendritic cells.

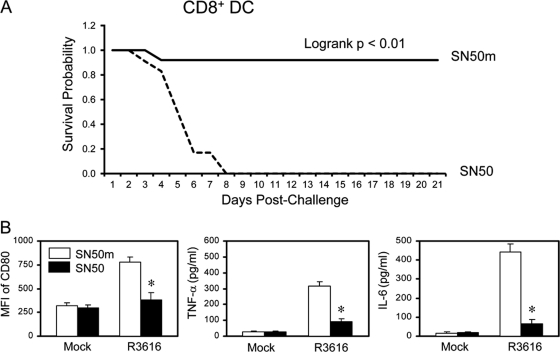

Finally, we tested whether the γ134.5 null mutant exerted its effect through NF-κB in CD8+ DCs. Purified CD8+ DCs were infected with R3616 in the presence of SN50 or SN50m for 12 h. Cells were adoptively transferred into naïve mice, which were challenged with HSV-1(F). As illustrated in Fig. 9A, none of the mice that received DCs with the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 survived beyond day 8 after lethal challenge with HSV-1(F). In stark contrast, 92% of mice that received DCs with the control inhibitor SN50m survived. In correlation, SN50 but not SN50m effectively inhibited the induction of CD80, TNF-α, and IL-6 by R3616 in CD8+ DCs (Fig. 9B). These results suggest that the γ134.5 null mutant-induced protective immunity requires NF-κB activation in CD8+ dendritic cells.

Fig 9.

(A) CD11c+ CD8+ DC-induced immunity requires NF-κB activation. Immature CD11c+ CD8+ DCs were infected with R3616 in the presence of SN50 or SN50m (30). At 12 h after infection, cells were transferred into naïve mice on days 1, 3, and 5. On day 6, mice were challenged with HSV-1(F) (1 × 107 PFU) and monitored over a 21-day period. The survival rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plots (n = 24, log rank P < 0.01). (B) Immature CD11c+ CD8+ DCs infected as described for panel A were assayed for CD80, TNF-α, and IL-6 expression. The results are from triplicate samples with standard deviations (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Control of acute or persistent HSV infection initially involves the innate immune system, which consists of DCs, macrophages, natural killer cells, cytokines, and complement proteins (11). In this study, we show that DCs from mice vaccinated with an HSV mutant lacking the γ134.5 gene confer resistance to HSV-1. Ex vivo exposure of DCs to the γ134.5 null mutant activates NF-κB, which parallels with upregulation of costimulatory molecules and inflammatory cytokines. This interaction translates into protective immunity against wild-type HSV-1 in vivo. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling in DCs reverses the protective effect. CD8+ DCs function more effectively than CD8− DCs. These results support the concept that stimulation of innate immune signaling by the γ134.5 null mutant potentiates protective immunity.

The γ134.5 null mutant is avirulent in vivo (4, 8, 33, 35, 43, 51, 56, 63). Although unable to produce infectious virus in DCs, the γ134.5 null mutant expressed early and late genes. Upon adoptive transfer, these DCs mediated protection against lethal challenge from wild-type virus. A question arises as to how the γ134.5 null mutant elicits immunity via DCs. Accumulating evidence suggests that TLR3, MDA5, and RIG-I detect HSV RNA (36, 47, 67), whereas polymerase III and IFI16 recognize intracellular HSV DNA (7, 59). Additionally, an unknown receptor in DCs senses HSV glycoproteins (50). We speculate that viral DNA, RNA, or a protein from the γ134.5 null mutant may trigger an aforementioned pathway(s) in its abortive infection, leading to protective immunity. In this respect, it is notable that HSV mutants deficient in ICP0, ICP4, or ICP27 behave differently in DCs (37). The ICP27 mutant stimulates the expression of type I interferon (IFN) and inflammatory cytokines in DCs, whereas ICP0 and ICP4 mutants do not. This is thought to result from an effect of ICP27 on posttranscriptional events in host RNA processing or the expression of a viral inhibitor(s) of cytokine expression (37). DCs recognize HSV via TLR-dependent and -independent pathways (22, 48, 50). As ICP27 and γ134.5 mutants differ in the nature of mutation, such a difference may affect their ways to interact with DCs. Although activating DCs, these mutants likely trigger innate immune pathways differently. Additional work is needed to test this hypothesis.

IκB kinase sits at the center of innate immune pathways, and its activation is linked to DC maturation (27, 49). It is well recognized that HSV both activates and inhibits NF-κB during infection. While NF-κB activation by HSV is required for optimal viral replication and cell survival in some cell settings (16, 17, 42), its activation also stimulates antiviral immunity (12, 37, 60). Intriguingly, HSV activation of NF-κB is linked to double-stranded-dependent protein kinase PKR (57). We noted that the γ134.5 null mutant induced phosphorylation of IKKβ and p65/RelA in DCs which induced protective immunity upon adoptive transfer. Inhibition of NF-κB activation reversed these phenotypes but had no effect on viral gene expression. We suspect that upon infection with the γ134.5 null mutant, viral proteins, such as gD and UL37, may activate NF-κB (31, 53). Alternatively, viral nucleic acids may stimulate NF-κB activation in DCs. Although not investigated, our data do not exclude the idea that the γ134.5 null mutant may act on DCs through additional pathways. An attractive possibility is to activate interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which leads to the expression of type I IFN and chemokines (27, 61). Another possibility is to stimulate transcription factor AP-1, which controls cytokine expression (27, 66).

It is noteworthy that the γ134.5 null mutant affects CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs differentially. Although activating NF-κB both in CD8+ DCs and in CD8− DCs, the γ134.5 null mutant induced protective immunity only via CD8+ DCs. We noted that the γ134.5 null mutant infected CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs equally well, with comparable early and late gene expression. This result rules out a difference in viral infection that may contribute to the observed phenotypes. A plausible explanation is that these DC subsets are functionally distinct. Therefore, besides NF-κB activation, an additional signal(s) or component from DCs is required to initiate protective immunity. Interpreted within this model, it is interesting that CD8+ DCs secreted a higher level of IL-6 and IL-12 than CD8− DCs upon exposure to the γ134.5 null mutant. Conversely, CD8− DCs produced more TNF-α. As these DC subsets displayed similar levels of cell surface molecules, different cytokine responses probably contributed to the phenotypes observed in vivo.

CD8+ DCs have been reported to play a key role in controlling viral infections (1, 2, 54). In light of these observations, it is intriguing that the γ134.5 null mutant induced protective immunity through CD8+ DCs. In principle, the γ134.5 null mutant may primarily target CD8+ DCs upon immunization. In this process, it likely promotes DC maturation as well as antigen presentation, which is coupled to NF-κB activation (64, 65). Emerging evidence suggests that CD8+ DCs preferentially initiate CD8 T cell immunity through TLR3 in response to HSV infection (13). Hence, the γ134.5 null mutant may activate the TLR3 pathway leading NF-κB activation. In line with this model, the γ134.5 null mutant induced NF-κB activation and the maturation of CD8+ DCs. While having no effect on viral gene expression, inhibition of NF-κB disrupted the ability of CD8+ DCs to mediate protective immunity in vivo. These observations underscore a key role of NF-κB and CD8+ DCs in controlling HSV infection. Work is in progress to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI092230).

We thank Bernard Roizman for providing valuable reagents.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Allan RS, et al. 2003. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8α+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science 301:1925–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belz GT, et al. 2004. Cutting edge: conventional CD8α+ dendritic cells are generally involved in priming CTL immunity to viruses. J. Immunol. 172:1996–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bjorck P. 2004. Dendritic cells exposed to herpes simplex virus in vivo do not produce IFN-α after rechallenge with virus in vitro and exhibit decreased T cell alloreactivity. J. Immunol. 172:5396–5404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bolovan CA, Sawtell NM, Thompson RL. 1994. ICP34.5 mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17syn+ are attenuated for neurovirulence in mice and for replication in confluent primary mouse embryo cell cultures. J. Virol. 68:48–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bosnjak L, et al. 2005. Herpes simplex virus infection of human dendritic cells induces apoptosis and allows cross-presentation via uninfected dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 174:2220–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown SM, MacLean AR, Aitken JD, Harland J. 1994. ICP34.5 influences herpes simplex virus type 1 maturation and egress from infected cells in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 75:3679–3686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. 2009. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell 138:576–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chou J, Kern ER, Whitley RJ, Roizman B. 1990. Mapping of herpes simplex virus-1 neurovirulence to γ134.5, a gene nonessential for growth in culture. Science 250:1262–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chou J, Roizman B. 1992. The γ134.5 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 precludes neuroblastoma cells from triggering total shutoff of protein synthesis characteristic of programmed cell death in neuronal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:3266–3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cotter AR, et al. 2010. The virion host shut-off (vhs) protein blocks a TLR-independent pathway of herpes simplex type 1 recognition in human and mouse dendritic cells. PLoS One 5:e8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cunningham AL, et al. 2006. The cycle of human herpes simplex virus infection: virus transport and immune control. J. Infect. Dis. 194(Suppl 1):S11–S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daubeuf S, et al. 2009. HSV ICP0 recruits USP7 to modulate TLR-mediated innate response. Blood 113:3264–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davey GM, et al. 2010. Cutting edge: priming of CD8 T cell immunity to herpes simplex virus type 1 requires cognate TLR3 expression in vivo. J. Immunol. 184:2243–2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ejercito PM, Kieff ED, Roizman B. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behaviour of infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2:357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farrell HE, et al. 1994. Vaccine potential of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant with an essential glycoprotein deleted. J. Virol. 68:927–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodkin ML, Ting AT, Blaho JA. 2003. NF-kappaB is required for apoptosis prevention during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 77:7261–7280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gregory D, Hargett D, Holmes D, Money E, Bachenheimer SL. 2004. Efficient replication by herpes simplex virus type 1 involves activation of the IkappaB kinase-IkappaB-p65 pathway. J. Virol. 78:13582–13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gyotoku T, Ono F, Aurelian L. 2002. Development of HSV-specific CD4+ Th1 responses and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes with antiviral activity by vaccination with the HSV-2 mutant ICP10deltaPK. Vaccine 20:2796–2807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halford WP, et al. 2011. A live-attenuated HSV-2 ICP0 virus elicits 10 to 100 times greater protection against genital herpes than a glycoprotein D subunit vaccine. PLoS One 6:e17748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He B, Gross M, Roizman B. 1998. The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 has the structural and functional attributes of a protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit and is present in a high molecular weight complex with the enzyme in infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20737–20743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He B, Gross M, Roizman B. 1997. The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1α to dephosphorylate the α subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:843–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hochrein H, et al. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type-1 induces IFN-alpha production via Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:11416–11421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jin H, et al. 2009. The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 is required to interfere with dendritic cell maturation during productive infection. J. Virol. 83:4984–4994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jin H, Yan Z, Ma Y, Cao Y, He B. 2011. A herpesvirus virulence factor inhibits dendritic cell maturation through protein phosphatase 1 and IκB kinase. J. Virol. 85:3397–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jing X, Cerveny M, Yang K, He B. 2004. Replication of herpes simplex virus 1 depends on the γ134.5 functions that facilitate virus response to interferon and egress in the different stages of productive infection. J. Virol. 78:7653–7666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones CA, et al. 2003. Herpes simplex virus type 2 induces rapid cell death and functional impairment of murine dendritic cells in vitro. J. Virol. 77:11139–11149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawai T, Akira S. 2006. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 7:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kruse M, et al. 2000. Mature dendritic cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibit inhibited T-cell stimulatory capacity. J. Virol. 74:7127–7136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kummer M, et al. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 induces CD83 degradation in mature dendritic cells with immediate-early kinetics via the cellular proteasome. J. Virol. 81:6326–6338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin YZ, Yao SY, Veach RA, Torgerson TR, Hawiger J. 1995. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14255–14258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu X, Fitzgerald K, Kurt-Jones E, Finberg R, Knipe DM. 2008. Herpesvirus tegument protein activates NF-kappaB signaling through the TRAF6 adaptor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:11335–11339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R, Iwasaki A. 2003. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:513–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacLean AR, Mul-Fareed Robertson L, Harland J, Brown SM. 1991. Herpes simplex virus type 1 deletion variants 1714 and 1716 pinpoint neurovirulence-related sequences in Glasgow strain 17+ between immediate early gene 1 and the ‘a’ sequence. J. Gen. Virol. 72:631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mao H, Rosenthal KS. 2003. Strain-dependent structural variants of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP34.5 determine viral plaque size, efficiency of glycoprotein processing, and viral release and neuroinvasive disease potential. J. Virol. 77:3409–3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McKie EA, Hope RG, Brown SM, MacLean AR. 1994. Characterization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17+ neurovirulence gene RL1 and its expression in a bacterial system. J. Gen. Virol. 75:733–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Melchjorsen J, et al. 2010. Early innate recognition of herpes simplex virus in human primary macrophages is mediated via the MDA5/MAVS-dependent and MDA5/MAVS/RNA polymerase III-independent pathways. J. Virol. 84:11350–11358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Melchjorsen J, Siren J, Julkunen I, Paludan SR, Matikainen S. 2006. Induction of cytokine expression by herpes simplex virus in human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells is dependent on virus replication and is counteracted by ICP27 targeting NF-kappaB and IRF-3. J. Gen. Virol. 87:1099–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mikloska Z, Bosnjak L, Cunningham AL. 2001. Immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells are productively infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:5958–5964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morrison LA, Knipe DM. 1997. Contributions of antibody and T cell subsets to protection elicited by immunization with a replication-defective mutant of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 239:315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Orvedahl A, et al. 2007. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 1:23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parker JN, et al. 2006. Genetically engineered herpes simplex viruses that express IL-12 or GM-CSF as vaccine candidates. Vaccine 24:1644–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel A, et al. 1998. Herpes simplex type 1 induction of persistent NF-kappa B nuclear translocation increases the efficiency of virus replication. Virology 247:212–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perng GC, et al. 1995. An avirulent ICP34.5 deletion mutant of herpes simplex virus type 1 is capable of in vivo spontaneous reactivation. J. Virol. 69:3033–3041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pollara G, et al. 2003. Herpes simplex virus infection of dendritic cells: balance among activation, inhibition, and immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 187:165–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prechtel AT, et al. 2005. Infection of mature dendritic cells with herpes simplex virus type 1 dramatically reduces lymphoid chemokine-mediated migration. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1645–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prichard MN, et al. 2005. Evaluation of AD472, a live attenuated recombinant herpes simplex virus type 2 vaccine in guinea pigs. Vaccine 23:5424–5431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rasmussen SB, et al. 2009. Herpes simplex virus infection is sensed by both Toll-like receptors and retinoic acid-inducible gene-like receptors, which synergize to induce type I interferon production. J. Gen. Virol. 90:74–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rasmussen SB, et al. 2007. Type I interferon production during herpes simplex virus infection is controlled by cell-type-specific viral recognition through Toll-like receptor 9, the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein pathway, and novel recognition systems. J. Virol. 81:13315–13324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rescigno M, Martino M, Sutherland CL, Gold MR, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. 1998. Dendritic cell survival and maturation are regulated by different signaling pathways. J. Exp. Med. 188:2175–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reske A, Pollara G, Krummenacher C, Katz DR, Chain BM. 2008. Glycoprotein-dependent and TLR2-independent innate immune recognition of herpes simplex virus-1 by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 180:7525–7536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robertson LM, MacLean AR, Brown SM. 1992. Peripheral replication and latency reactivation kinetics of the non-neurovirulent herpes simplex virus type 1 variant 1716. J. Gen. Virol. 73:967–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Salio M, Cella M, Suter M, Lanzavecchia A. 1999. Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by herpes simplex virus. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:3245–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sciortino MT, et al. 2008. Involvement of HVEM receptor in activation of nuclear factor kappaB by herpes simplex virus 1 glycoprotein D. Cell. Microbiol. 10:2297–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith CM, et al. 2003. Cutting edge: conventional CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells are preferentially involved in CTL priming after footpad infection with herpes simplex virus-1. J. Immunol. 170:4437–4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Spector FC, et al. 1998. Evaluation of a live attenuated recombinant virus RAV 9395 as a herpes simplex virus type 2 vaccine in guinea pigs. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1143–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spivack JG, et al. 1995. Replication, establishment of latent infection, expression of the latency-associated transcripts and explant reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 gamma 34.5 mutants in a mouse eye model. J. Gen. Virol. 76:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Taddeo B, Luo TR, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2003. Activation of NF-kappaB in cells productively infected with HSV-1 depends on activated protein kinase R and plays no apparent role in blocking apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12408–12413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Taylor PR, et al. J-LEAPS vaccines initiate murine Th1 responses by activating dendritic cells. Vaccine 28:5533-–5542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Unterholzner L, et al. 2010. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 11:997–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Lint AL, et al. 2010. Herpes simplex virus immediate-early ICP0 protein inhibits Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inflammatory responses and NF-kB signaling. J. Virol. 84:10802–10811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Verpooten D, Ma Y, Hou S, Yan Z, He B. 2009. Control of TANK-binding kinase 1-mediated signaling by the γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1. J. Biol. Chem. 284:1097–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Walker J, Leib DA. 1998. Protection from primary infection and establishment of latency by vaccination with a herpes simplex virus type 1 recombinant deficient in the virion host shutoff (vhs) function. Vaccine 16:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Whitley RJ, Kern ER, Chatterjee S, Chou J, Roizman B. 1993. Replication, establishment of latency, and induced reactivation of herpes simplex virus γ134.5 deletion mutants in rodent models. J. Clin. Invest. 91:2837–2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yoshimura S, Bondeson J, Brennan FM, Foxwell BM, Feldmann M. 2003. Antigen presentation by murine dendritic cells is nuclear factor-kappa B dependent both in vitro and in vivo. Scand. J. Immunol. 58:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yoshimura S, Bondeson J, Brennan FM, Foxwell BM, Feldmann M. 2001. Role of NFkappaB in antigen presentation and development of regulatory T cells elucidated by treatment of dendritic cells with the proteasome inhibitor PSI. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1883–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zachos G, Clements B, Conner J. 1999. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection stimulates p38/c-Jun N-terminal mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and activates transcription factor AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5097–5103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang SY, et al. 2007. TLR3 deficiency in patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. Science 317:1522–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhao X, et al. 2003. Vaginal submucosal dendritic cells, but not Langerhans cells, induce protective Th1 responses to herpes simplex virus-2. J. Exp. Med. 197:153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]