Abstract

Caulobacter crescentus differentiates from a motile, foraging swarmer cell into a sessile, replication-competent stalked cell during its cell cycle. This developmental transition is inhibited by nutrient deprivation to favor the motile swarmer state. We identify two cell cycle regulatory signals, ppGpp and polyphosphate (polyP), that inhibit the swarmer-to-stalked transition in both complex and glucose-exhausted media, thereby increasing the proportion of swarmer cells in mixed culture. Upon depletion of available carbon, swarmer cells lacking the ability to synthesize ppGpp or polyP improperly initiate chromosome replication, proteolyze the replication inhibitor CtrA, localize the cell fate determinant DivJ, and develop polar stalks. Furthermore, we show that swarmer cells produce more ppGpp than stalked cells upon starvation. These results provide evidence that ppGpp and polyP are cell-type-specific developmental regulators.

INTRODUCTION

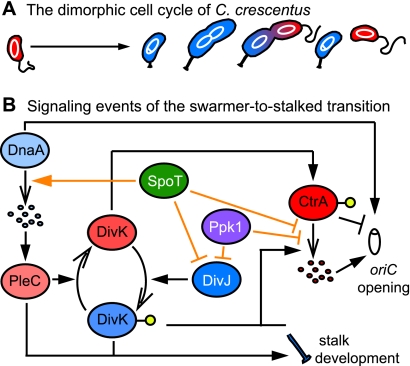

Caulobacter crescentus displays a dimorphic life cycle, beginning with a flagellated and chemotactic swarmer cell that neither grows nor replicates its chromosome. After a time, the swarmer cell sheds its flagellum and grows in its place a stalk appended with an adhesive holdfast; initiation of chromosome replication occurs concomitantly. The stalked cell grows and builds a new flagellum opposite the stalked pole, and, upon cytokinesis, a new swarmer cell is released from the parental stalked cell. The stalked cell immediately recommences chromosome replication and growth, while the swarmer cell must spend a period of time in the replicationally quiescent state before transitioning into a stalked cell (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

Important signaling events of the swarmer-to-stalked transition. (A) Morphological progression of the C. crescentus cell cycle. Swarmer cells are shown in red; stalked cells are shown in blue. The chromosome is white. (B) Reduced model of the signaling events of the swarmer-to-stalked transition. Proteins that promote swarmer cell identity are shades of red; proteins that promote stalked-cell identity are shades of blue. Filled arrowheads indicate signal activation. Open arrowheads indicate physical transitions such as proteolysis (group of ovals) or phosphorylation (yellow circles). Perpendicular lines represent signal inhibition. Black lines indicate signaling events that occur during normal cell cycle progression in nutrient-replete medium; orange lines indicate signaling events that occur during nutrient limitation. Signaling events may be direct or indirect.

Although the regulation of the C. crescentus cell cycle has been extensively studied (10), little is known about how environmental signals impinge upon cell cycle progression. C. crescentus inhabits oligotrophic (i.e., nutrient-poor) environments. The dimorphic life cycle is thought to be an adaptation to oligotrophy (14, 36), because it (i) allows the swarmer cells to seek advantageous new environments before entering the nonmotile, replicative phase (2) and (ii) allows the sessile stalked cells to remain attached to nutrient resources via the holdfast. As the two cell types have different roles with respect to the nutrient environment, one might predict that differentiation from the swarmer to stalked cell type is regulated in a nutrient-dependent manner. Indeed, a population of C. crescentus cells grown in continuous culture under phosphorus- or nitrogen-limiting conditions accumulates a higher proportion of swarmer cells than is observed in nutrient-replete medium (14, 37). To date no mechanism has been ascribed to this nutrient-dependent swarmer accumulation phenomenon.

An increase in the proportion of swarmer cells in a population requires either inhibition of the swarmer-to-stalked transition or acceleration of stalked-cell division relative to the rest of the cell cycle. In the face of nutrient limitation, we hypothesized that preferential inhibition of the swarmer-to-stalked transition is likely responsible for swarmer accumulation. This seems a logical response to low nutrients: a motile swarmer cell that transitions into a nonmotile stalked cell gives up the ability to actively seek an improved environment. Once a cell has entered the stalked phase and attached to a substrate, it can genetically escape a poor environment only by dividing and yielding a new swarmer. We predict that differentiation of the swarmer cell is more sensitive to nutrient limitation than division of the stalked cell and that this underlies nutrient-dependent swarmer accumulation.

A complex series of molecular regulatory events govern the swarmer-to-stalked transition (Fig. 1B). The final two steps of this developmental transition are initiation of chromosome replication and growth of a stalk. The origin-binding response regulator CtrA initially represses replication initiation. CtrA is both deactivated by dephosphorylation and proteolyzed at the swarmer-to-stalked transition (11, 39), and the concentration of the replication initiation factor DnaA peaks in this same period (18), promoting chromosome replication (6). The two-component receiver protein DivK is central in the regulation of these events; its phosphorylation state determines cell fate. Briefly, the swarmer cell determinant PleC localizes to the flagellar pole and functions as a phosphatase of DivK (32, 34, 51). In its unphosphorylated state, DivK stabilizes CtrA thereby inhibiting replication initiation (3, 24). The stalked-cell determinant DivJ replaces PleC at the flagellar/nascent stalked pole during the swarmer-to-stalked transition and is activated as a kinase of DivK (32, 40). Phosphorylated DivK (DivK∼P) represses a polar signaling complex (47), ultimately promoting the deactivation and proteolysis of CtrA (3) and replication. DivK∼P and PleC also activate the PleD regulator (34), which cues stalk development (35).

We have identified two signaling molecules, ppGpp and inorganic polyphosphate (polyP), that are involved in inhibiting the swarmer-to-stalked transition upon exhaustion of glucose from the growth medium. ppGpp (guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate) is the effector of the stringent response, whereby orderly growth inhibition promotes survival in starvation. In the stringent response, transcription is globally reprogrammed for adaptation to starvation via the activity of ppGpp on RNA polymerase (46). ppGpp also inhibits DNA replication via its activity on replication factors (16, 30). In C. crescentus, ppGpp is synthesized by the enzyme SpoT (30). polyP consists of linear chains of phosphate residues, which are synthesized by polyphosphate kinase (Ppk1) (1). In addition to storing phosphorus, polyP helps bacteria adapt to changing nutrient availability by regenerating ATP or GTP (25), regulating sigma factors, and activating the Lon protease (28, 42). polyP levels increase in Caulobacter species during stationary phase (20).

In this work we examine the genetic and molecular basis of swarmer cell accumulation in C. crescentus, which is induced under conditions of nutrient deprivation. Specifically, we present evidence that ppGpp and polyP inhibit several critical regulatory events of the swarmer-to-stalked transition, including CtrA proteolysis, DivJ localization, replication initiation, and stalk development. This study demonstrates a role for these two broadly conserved signaling molecules as developmental regulators with cell-type-specific activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions and growth measurements.

NA1000 strains were grown in M2G minimal medium (13) or peptone-yeast extract (PYE) complex medium at 30°C. Glucose exhaustion experiments were done on cultures grown in M2G to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of <0.3. Cells were switched to M2G with 0.02% glucose (M2G1/10) and then diluted to an OD660 of 0.13. Experiments with the origin-labeled strains were done in PYE with 0.2% glucose, and tetR-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was induced for 1 h with 0.15% xylose. ppk1 overexpression experiments were done in PYE supplemented with 0.3% xylose for 1 h before growth analysis. Kanamycin was used for plasmid selection in C. crescentus at 5 μg/ml in liquid media and 25 μg/ml on solid media. Escherichia coli strains TOP10 and Mach1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for cloning. E. coli strains were grown in Terrific broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C.

C. crescentus NA1000 cultures were serially passaged so that they were maintained in log phase (OD660 ≤ 0.3) for at least 36 h before experiments were conducted. Density measurements for individual cultures were taken regularly up to an OD660 of 0.3, and growth rates were determined by fitting the data to the exponential growth equation y(t) = y0ekt, where t is time, y is cell density, and k is growth rate. Error in doubling time was calculated from the distribution of mean cell population doubling times among independent biological replicates.

For analysis of cell population growth rate data, the doubling times of ΔspoT and Δppk1 in-frame null mutants and point mutants were compared to that of four independent paired cultures of wild-type strain NA1000; the mean doubling time of the wild type was normalized to 1. ΔspoT::spoT and Δppk1::ppk1 complemented strains were grown in PYE plus 0.3% xylose; their doubling times were compared to those of empty vector control ΔspoT::EV and Δppk1::EV strains, which were normalized to those of ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains, respectively. Growth rate measurements for four independent cultures were carried out for each strain.

Strain construction.

All experimental strains (Table 1) were derived from wild-type C. crescentus strain NA1000 (15). The Δppk1 strain was made by amplifying ∼500 bases upstream and downstream of ppk1 (gene CC_1710), ligating into pNPTS138, and following a double-recombination gene replacement protocol described previously (17). The ppk1 deletion primers are as follows: up forward, 5′-GGATCCCTCCCCTTGTGGGAGAAGG-3′; up reverse, 5′-AAGCTTAGGCGCTGTTCCACATTCT-3′; down forward, 5′-GAATTCCGCGTCCTTTAGCCTATTCC-3′; down reverse, 5′-GGATCCATGACCAATCCCAGCCTGT-3′. The Δppx1 (gene CC_1708) strain was made in an analogous fashion using the following primers: up forward, 5′-GGATCCGACCGAGTTTGAGCCGATA-3′; up reverse, 5′-AAGCTTCTGCTGGTTCCGGTCCTC-3′; down forward, 5′-GAATTCCTACCAGGCCGAGTTCTTT-3′; down reverse 5′-GGATCCGCACAGCATCCTTGGACTCAA-3′. The ΔspoT ori-yfp and Δppk1 ori-yfp strains were made by the same deletion method in the NA1000 CC0006::tetO xylX::tetR-yfp (also known as NA1000 ori-yfp) background (50). The boundaries of the pNPTS138 spoT deletion plasmid have been described previously (4). Strains NA1000 divJ-yfp, NA1000 ΔspoT/divJ-yfp, and NA1000 Δppk1/divJ-yfp were made by mating E. coli strain S17-1/pBGS18T-ctermDivJ-mYFP (29) with the respective recipient strains. The NA1000 CFP-parB strain (45) was a gift from the lab of Lucy Shapiro. The ΔspoT CFP-parB, Δppk1 CFP-parB, and ΔspoTΔppk1 CFP-parB strains were made by deleting spoT, ppk1, or both, respectively, in the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-parB background. The spoT(Y323A), ppk1(H460A), and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged strains were all made by PCR amplification of regions around the mutation with gene stitching mutagenesis (21), ligation into pNPTS138, and use of the double-recombination gene replacement protocol described previously (17).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains (FC no.) | ||

| 20 | NA1000 | 15, 31 |

| 769 | ΔspoT | 4 |

| 1460 | Δppk1 | This work |

| 1002 | spoT(Y323A) | This work |

| 1454 | ppk1(H640A) | This work |

| 1045 | ΔspoTxylX::pMT681 (ΔspoT::EV) | This work |

| 1046 | ΔspoTxylX::pMT681-spoT (ΔspoT::spoT) | This work |

| 1579 | xylX::pMT585 (NA1000::EV) | This work |

| 1581 | Δppk1xylX::pMT585 (Δppk1::EV) | This work |

| 1584 | Δppk1xylX::pMT585-ppk1 (Δppk1::ppk1) | This work |

| 943 | HA-spoT | 4 |

| 1138 | HA-spoT(Y323A) | This work |

| 1452 | ppk1-HA | This work |

| 1458 | ppk1(H460A)-HA | This work |

| 830 | CC0006::tetOxylX::(tetR-YFP) (ori-YFP) | 48 |

| 834 | ΔspoTCC0006::tetO xylX::(tetR-YFP) (ΔspoTori-YFP) | This work |

| 1439 | Δppk1CC0006::tetO xylX::(tetR-YFP) (Δppk1ori-YFP) | This work |

| 771 | CFP-parB | 44 |

| 1490 | ΔspoT CFP-parB | This work |

| 1440 | Δppk1 CFP-parB | This work |

| 1413 | divJ::pBGS18T-CTdivJ-YFP (divJ-YFP) | 29 |

| 1414 | ΔspoT divJ::pBGS18T-CTdivJ-YFP (ΔspoTdivJ-YFP) | This work |

| 1434 | Δppk1 divJ::pBGS18T-CTdivJ-YFP (Δppk1 divJ-YFP) | This work |

| 1625 | ΔspoT Δppk1 | This work |

| 1680 | ΔspoTΔppk1 CFP-parB | This work |

| 1582 | xylX::pMT585-ppk1 (NA1000::ppk1) | This work |

| 1583 | Δppx1xylX::pMT585-ppk1 (Δppx1::ppk1) | This work |

| 1675 | ΔspoTxylX::pMT585-ppk1 (ΔspoT::ppk1) | This work |

| 1677 | ΔspoTΔppx1xylX::pMT585-ppk1 (ΔspoTΔppx1::ppk1) | This work |

| 1580 | Δppx1xylX::pMT585 (Δppx1::EV) | This work |

| 1674 | ΔspoTxylX::pMT585 (ΔspoT::EV) | This work |

| 1676 | ΔspoTΔppx1xylX::pMT585 (ΔspoTΔppx1::EV) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMT681 | 43 | |

| pMT585 | 43 | |

| pNPTS138 | Dickon Alley | |

| pBGS18T | 29 |

Microscopy and image analysis.

Light microscopy was conducted with a Leica CTR5000 microscope, and images were acquired with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera. Fixed cells were immobilized on 1% agarose pads before imaging. Cells were fixed at room temperature (RT) for 8 min by mixing 500 μl of culture with 100 μl of 16% paraformaldehyde, 0.0001% glutaraldehyde, and 20 μl 1 M NaPO4, pH 7.4, then washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For each strain and time point, 400 to 1,500 cells from each of three independent biological replicates were imaged and counted, and the final values are the means for the replicates. Origin foci were counted manually. DivJ-YFP puncta were counted in ImageJ from threshold binary phase and fluorescent images.

For transmission electron microscopy for polyP granules, log phase cells were switched from M2G to M2G1/10, then collected after 5 h. The cells were fixed as described above, washed with water, spotted onto Formvar-carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grids, air dried, and visualized without staining. For transmission electron microscopy for stalk analysis, cells were prepared as described previously (5); briefly, cells were harvested, fixed, stained with 1% uranyl acetate, spotted onto Formvar-carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grids, and air dried. Grids were imaged at ×1,890 magnification for stalk analysis and at ×16,800 for polyP analysis using a FEI Technai F30 scanning transmission electron microscope equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan camera. Cells were counted manually.

Cell synchrony.

Synchronies for the ppGpp assays were conducted in nonstarvation conditions in M2G medium. Cells were labeled in KH232PO4 for 2 h and pelleted, the volume was reduced to 900 μl, 900 μl of Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the tube was spun at 11,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The stalked and swarmer bands were put into separate tubes and washed in M2. For Western blot samples in replete medium, synchronies were conducted as described previously (5). Cultures for Western blot samples during glucose exhaustion were grown in M2G, pelleted, resuspended in M2G1/10 at an OD660 of 0.13, shaken at 30°C until they reached an OD660 of 0.23, and then pelleted and resuspended in filter-sterilized spent M2G1/10 medium taken from wild-type cultures that also grew from an OD660 of 0.13 to an OD660 of 0.23. Synchronies were conducted as described above, and swarmer cells were washed and resuspended in the spent medium.

Measurement of ppGpp levels.

ppGpp was measured as described previously (4). Briefly, cells were placed into medium lacking phosphate and then incubated with KH232PO4 (Perkin Elmer) at 100 μCi ml−1. Cell lysates were formic acid extracted and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Western blots.

Anti-DnaA blotting (30), anti-CtrA blotting (19), and anti-HA blotting (4) were performed as described previously. Equal cell densities, as determined by measuring OD660, were loaded into each lane of gels. Densities of bands on Western blots were quantified using ImageJ (7).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ppGpp and polyP lengthen division times in complex medium.

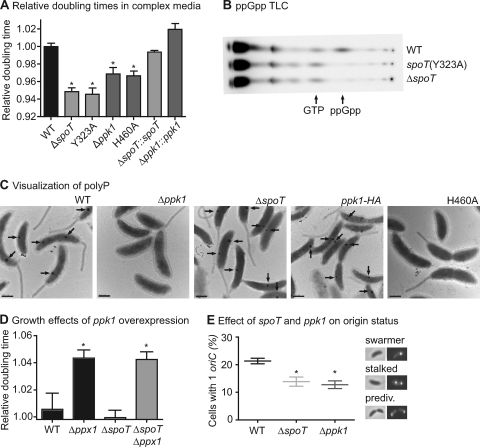

ppGpp and polyP are signaling molecules involved in adjusting growth rates during starvation, nutrient shifts, and stress. Given the result that ppGpp regulates replication initiation in C. crescentus (30) and the known role of polyP in nutrient-dependent control of bacterial physiology (9), we sought to test the role of these two molecules in the regulation of C. crescentus growth and development. Preliminary growth experiments with deletion strains (Table 1) in peptone-yeast extract (PYE) complex medium yielded a surprising result: both ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains grow faster than the wild-type NA1000 strain (Fig. 2A). The fast-growth phenotype can be complemented by integration of a single copy of spoT or ppk1, respectively, at an ectopic locus (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

ppGpp and polyP lengthen the swarmer stage in complex medium. (A) Relative doubling times of strains growing in complex medium. Shown are normalized doubling times of wild-type (WT), ΔspoT, Δppk1, and point mutant strains and ΔspoT::spoT and Δppk1::ppk1 complemented strains (Table 1) (see Materials and Methods for information on growth conditions and data analysis) (n = 4). Error bars represent standard errors of the means. All normalized doubling times are compared to the wild-type control (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; Dunnetts's posttest; ∗, P < 0.01). (B) TLC showing 32P-labeled spots of nucleotides extracted from glucose-starved wild-type, spoT(Y323A), and ΔspoT strains. (C) Transmission electron micrographs of unstained cells grown in glucose exhaustion conditions for 5 h. Dark granules containing polyP (8) are marked with arrows. Bars, 500 nm. (D) Doubling times of strains overexpressing ppk1 from the xylX promoter, normalized to their respective empty-vector control strains (Table 1). Growth was measured in PYE supplemented with 0.3% xylose (n = 3). Error bars represent standard errors of the means. Each strain overexpressing ppk1 was compared to its respective empty-vector control (one-way ANOVA; Bonferroni's posttest; ∗, P < 0.001). (E) Percentages of cells with a single origin of replication in mixed cultures growing in PYE, as quantified by counting tetR-YFP–oriC::tetO foci (Table 1). Representative images of fluorescent oriC from swarmer, stalked, and predivisional cells are at the right. The central bar indicates the mean value of the replicates (n = 3); error bars represent standard errors of the means. Each strain is compared to the wild type (one-way ANOVA; Dunnett's posttest; ∗, P < 0.05).

To confirm that this phenotype is due to the known catalytic activities of these two enzymes, we built strains with single point mutations in the ppGpp synthetase domain of SpoT (Y323A) (23) or the polyP synthesis site in Ppk1 (H460A) (26). These point mutant proteins were stable (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material) and phenocopied the full gene deletions (Fig. 2A), indicating that the fast-growth phenotypes are due to the loss of ppGpp and polyP synthesis. We confirmed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) that the spoT(Y323A) strain failed to produce ppGpp in glucose starvation (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, we visualized unstained C. crescentus cells from cultures that had exhausted their sole carbon source by transmission electron microscopy: wild-type cells and cells bearing an HA-tagged ppk1 produce electron-dense intracellular granules that are known to be phosphorus rich (8) (Fig. 2C). In contrast, cells lacking ppk1 or possessing a single amino acid substitution in the predicted Ppk1 active site produce no prominent electron-dense granules when grown under identical conditions. In E. coli, mutants defective in ppGpp synthesis also exhibit a defect in polyP accumulation (27). However, the C. crescentus ΔspoT null mutant produces granules indistinguishable from the wild type under these conditions, even though the transcription of ppk1 is strongly regulated by spoT under abrupt starvation conditions (4). From these data, we conclude that polyP synthesis and the accompanying slowing of division time require a catalytically active ppk1, but not spoT, under these tested conditions.

Since loss of ppk1 increases growth rate in complex medium, we sought to determine if ppk1 overexpression is sufficient to slow growth under similar conditions. We integrated a single copy of either ppk1 or an empty vector under the control of a xylose-inducible promoter at the chromosomal xylX locus (33). Cells expressing ppk1 in PYE complex medium supplemented with xylose showed no significant difference in growth rate relative to the empty-vector control (Fig. 2D). Since the C. crescentus genome encodes a putative exopolyphosphatase (encoded by ppx1, which is just downstream of ppk1), we reasoned that an intact Ppx1 may be responsible for breaking down excess polyP. We therefore overexpressed ppk1 in a Δppx1 background. Relative to that of the empty-vector control, the growth rate of ppk1-overexpressing cells in this genetic background was significantly slower. We repeated these growth experiments in strains lacking spoT, obtaining nearly identical growth rate changes compared to strains with intact spoT. Thus, ppk1 overexpression is sufficient to slow growth in complex medium in the absence of ppx1, and spoT is not required for this phenotype. Unlike Ppk1, which possesses one active site, SpoT contains both ppGpp synthase and hydrolase domains. We do not currently understand how these two activities are differentially regulated, but we do know that the rates of ppGpp synthesis differ between swarmer and stalked cells (see Fig. 5). Given this complexity, we were uncertain how we would interpret the results of a spoT overexpression experiment and have therefore not assessed the sufficiency of ppGpp in modulating growth rate and cell differentiation at this time.

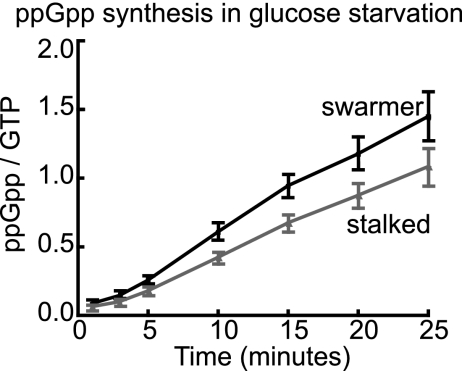

Fig 5.

ppGpp accumulation in response to starvation in swarmer versus stalked cells. Mixed cultures were labeled with KH232PO4. The swarmer and stalked-cell bands were separated in a Percoll gradient, washed separately, and then resuspended in M2 defined medium lacking glucose. Samples were extracted, and nucleotides were resolved by TLC at time points after starvation (n = 6; linear regression; P < 0.01). Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

The known roles of polyP involve promoting growth in the face of shifting nutrient conditions (28). Here, we present novel evidence that polyP can also function to “brake” bacterial growth under nutrient-replete conditions. Our data provide evidence that ppGpp also functions to slow growth not only in starvation but also in nutrient-rich conditions.

To more fully understand the observed changes in growth rate, we sought to test whether the swarmer and stalked stages of the division cycle were equally shortened in the ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains or whether one phase was differentially shortened. We used strains expressing tetR-YFP with tetO arrays near the origin of replication (50) to distinguish swarmer and stalked cells by replication status. Cells growing in PYE medium were imaged by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy, and the fraction of cells with one origin focus (swarmers) was calculated (Fig. 2E). The ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains have a smaller fraction of cells with a single origin than the wild-type strain (P < 0.05). This finding suggests that the small amounts of ppGpp and polyP produced in log phase C. crescentus cells in complex medium are sufficient to prolong the swarmer stage, delaying either replication initiation or segregation.

ΔspoT cells fail to properly halt growth under glucose exhaustion.

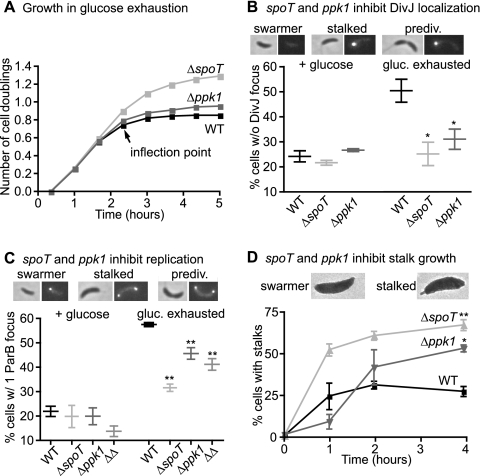

As ppGpp and polyP levels are increased during starvation, we reasoned that the preferential inhibition of the swarmer-to-stalked transition might be accentuated under a starvation condition and that these molecules may be required for swarmer accumulation. Although glucose limitation was previously reported to have no effect on swarmer accumulation (14), we thought this negative result might be a function of the glucose concentration used (2.2 mM). To test the effects of lower concentrations of glucose on swarmer accumulation, we conducted a glucose exhaustion assay in which cultures growing in M2G were switched to M2G1/10 (1.1 mM glucose). In minimal defined medium, wild-type, Δppk1, and ΔspoT cells initially grow at the same rate (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). We do not know why growth rate differences between these strains are observed in complex (Fig. 2A) but not minimal medium, but we speculate that growth rate-limiting steps vary in different medium conditions. Soon after cultures are switched to M2G1/10, they cease growth as glucose is exhausted (Fig. 3A). As observed in other species (53), the ΔspoT strain is impaired in its ability to restrain growth upon nutrient deprivation and attains a higher culture density (Fig. 3A); this greater density is partially due to an increased cell size, which is also observed in other species (52). Inability to restrain growth is presumably detrimental, as the ΔspoT strain has reduced viability after carbon starvation (30).

Fig 3.

ppGpp and polyP contribute to swarmer accumulation during glucose exhaustion. (A) Number of cell doublings, determined by measuring OD660, in wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 strains after transfer to glucose exhaustion medium (M2G1/10). The labeled inflection point indicates the time at which experiments in panel D and Fig. 4A (right) and B commenced (n = 3; error bars representing standard errors of the means are plotted but are too small to see). (B and C) Percentages of cells without a DivJ-YFP focus (B) and with a single CFP-ParB focus (C) during log phase growth in M2G (+ glucose) and 5 h after the switch to M2G1/10 (gluc. exhausted). Micrographs showing DivJ-YFP fluorescence (B) and CFP-ParB fluorescence (C) in representative swarmer, stalked, and predivisional cells are shown at the top. ΔΔ represents the ΔspoT Δppk1 strain. Strains are compared to glucose-exhausted wild-type control (one-way ANOVA; Dunnett's posttest; n = 3). ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01. (D) Percentages of swarmer cells that develop stalks during glucose exhaustion. Cells were imaged by electron microscopy at 0, 1, 2, and 4 h after synchrony at the inflection point of glucose exhaustion (n = 2; 170 to 400 cells for each replicate). Strains are compared to the wild type at the 4-h time point (one-way ANOVA; Tukey's posttest; ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01). Electron micrographs of a swarmer cell and a nascent stalked cell are shown at the top. Bars and points indicate mean values of replicates; error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

spoT and ppk1 inhibit DivJ localization in glucose exhaustion.

One of the early events in the swarmer-to-stalked transition is the phosphorylation of DivK, which indirectly signals initiation of this cell type switch. DivK is phosphorylated by DivJ, which first must be localized to the nascent stalked pole and activated (40, 41). Localization of DivJ to the pole is thus an important marker of the swarmer-to-stalked transition. To test how glucose exhaustion affects swarmer accumulation with respect to DivJ localization, we built strains with DivJ-YFP fusions in the wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 backgrounds, grew the cells to log phase in M2G defined medium, switched the cells to M2G1/10, and determined the proportions of cells with (stalked) and without (swarmers) a DivJ-YFP focus before and after glucose exhaustion. All strains in nutrient-replete M2G medium had ∼25% of cells without a DivJ focus, indicating that ∼25% of cells in these populations are swarmers (Fig. 3B). After glucose exhaustion the proportion of cells without a DivJ focus nearly doubled in wild-type cells, while remaining near 25% in the ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains (Fig. 3B). These data provide evidence that the activities of spoT and ppk1 are important for inhibiting localization, and presumably activation, of DivJ during glucose exhaustion. Because DivJ localization is thought to be required for activity (40, 41), we speculate that in wild-type glucose-exhausted cells in which DivJ fails to localize, DivK is not phosphorylated and the developmental transitions dependent upon DivK∼P do not proceed. We note that many of the DivJ foci in Δppk1 cells after glucose exhaustion are dimmer than the foci in the other strains. In addition, we observed that after prolonged glucose starvation—several hours past the time of the data presented here—all strains exhibited many cells with two bright DivJ foci.

spoT and ppk1 inhibit replication initiation in glucose exhaustion.

The swarmer-to-stalked transition involves multiple signaling events and morphological changes, one of which is initiation of chromosome replication. We therefore studied the effects of glucose exhaustion on swarmer accumulation with respect to replication initiation. ParB is a protein that binds at oriC and is involved in chromosome partitioning: strains with a CFP-ParB fusion exhibit fluorescent foci at each oriC in the cell (45) and can be used to quantify oriC within a cell (5). We used this fluorescent protein fusion in the wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 backgrounds to assay the proportion of cells with a single ParB focus after glucose exhaustion. We collected samples from cultures growing in M2G and cultures 5 h after the switch to M2G1/10. In M2G medium, wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 strains have ∼20% of cells with a single ParB focus (Fig. 3C), which accords with our observation that these strains grow at the same rate in M2G (Fig. S2). After glucose exhaustion the wild-type strain has almost three times as many cells with a single ParB focus (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that glucose exhaustion induces swarmer accumulation with respect to ParB localization. While both the ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains exhibit an increased proportion of cells with a single ParB focus after glucose exhaustion, both of these increases are less (P < 0.01) than is seen in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3C). Thus, both spoT and ppk1 affect the inhibition of replication initiation or segregation during glucose exhaustion.

As replication initiation is still partially inhibited during glucose exhaustion in ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains, we sought to determine if the inhibitory effects of spoT and ppk1 are additive. We constructed a ΔspoT Δppk1 strain and found that its behavior is similar to that of the single deletion mutants with respect to replication initiation and segregation (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the double mutant grows more slowly than either of the single deletion mutants during log phase in minimal defined medium (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that dysregulation of cell cycle control follows loss of both gene products and emphasizing that spoT and ppk1 do not operate in a simple linear pathway to control growth.

spoT and ppk1 inhibit stalk development in glucose exhaustion.

Data reported thus far reveal that swarmer accumulation in mixed culture depends on spoT and ppk1. To further test the hypothesis that swarmer development is specifically blocked in a spoT- and ppk1-dependent manner, we isolated synchronized populations of wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 swarmer cells in glucose exhaustion and directly assayed their propensity to grow polar stalks. Cells were first grown in M2G defined medium, then switched to M2G1/10 and allowed growth to the inflection point of glucose exhaustion (Fig. 3A). Cells were then synchronized, and isolated swarmers were resuspended in spent medium also collected from the inflection point of a wild-type culture. Samples for electron microscopy were collected directly after synchrony and up to 4 h later. Approximately 25% of wild-type swarmers grow distinguishable polar stalks in glucose exhaustion (Fig. 3D). In contrast, between 50 and 70% of ΔspoT and Δppk1 swarmer cells develop polar stalks under glucose exhaustion conditions. Thus, stalk development is inhibited by glucose exhaustion, and this developmental inhibition requires both spoT and ppk1. The ΔspoT Δppk1 strain displayed a proportion of stalked cells similar to that of the ΔspoT strain at the 4-h time point (71%).

During growth in nutrient-replete medium, stalk development and replication initiation are coupled and occur simultaneously. Stalk development and replication initiation appear largely coupled during glucose exhaustion as well. Different results were observed in experiments in which glucose was completely removed: cells that are abruptly starved for glucose show small stalks that develop in 65% of swarmer cells after 2 h, even while origins are replicated in only 10% of swarmer cells (5). These disparities may indicate that developmental phenotypes can vary based on specific environmental conditions such as abrupt starvation versus gradual nutrient exhaustion. Poindexter hypothesized that the amount of time spent in the swarmer state depends on the stored phosphorus cells inherit at birth (38); the increased propensity of Δppk1 swarmers to differentiate provides genetic support for this hypothesis.

Motivated by our observed stalk development phenotype, we investigated protein levels of PodJ, a protein known to govern polar organelle development. Though levels of this protein do not appear to depend on spoT or ppk1, we note a genetically distinct mechanism of starvation-dependent cell cycle regulation in the control of PodJ stability. PodJ, which exists as long and short forms across the cell cycle, is a localization factor for the swarmer cell determinant PleC (22, 49). In wild-type swarmer cells grown under nutrient-replete conditions, the short form of PodJ is degraded while the long form begins to accumulate at the swarmer-to-stalked transition. However, during glucose exhaustion the short form of PodJ is stabilized and the long form accumulates to lower levels. This effect is independent of both spoT and ppk1 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) and provides evidence for additional nutrient-dependent cell cycle effectors beyond ppGpp and polyP.

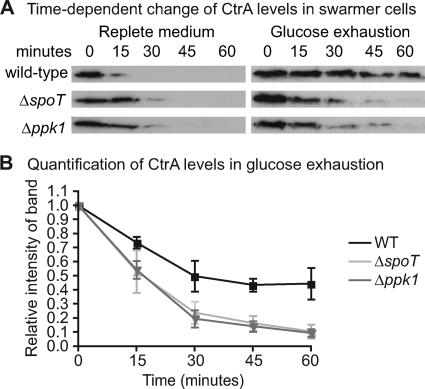

spoT and ppk1 affect the stability of the replication inhibitor CtrA.

Replication initiation is reciprocally controlled by DnaA and CtrA. CtrA binds and occludes oriC to prevent initiation during the swarmer stage and is subsequently deactivated and proteolyzed to allow replication during the swarmer-to-stalked transition (11, 39). In starvation, CtrA is stabilized in swarmer cells (19). DnaA initiates replication by binding oriC, separating the strands, and recruiting other replication factors (18). DnaA levels peak during the swarmer-to-stalked transition in replete medium (19). However, in carbon starvation ppGpp activates the premature proteolysis of DnaA to prevent replication initiation (30). We sought to test whether polyP also impacts DnaA stability and whether ppGpp and polyP affect the stability of the replication inhibitor CtrA.

To measure CtrA and DnaA protein levels during the swarmer-to-stalked transition, we isolated swarmer cells from wild-type, ΔspoT, and Δppk1 cultures growing in replete M2G or at the inflection point of glucose exhaustion (Fig. 3A). We then resuspended the swarmers in M2G or spent medium from a wild-type culture at the glucose exhaustion inflection point, respectively, and harvested samples for Western blots at various times after resuspension. The results of these experiments show that, in replete medium, CtrA and DnaA levels in the ΔspoT and Δppk1 strains are similar to those in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A; see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). During glucose exhaustion, DnaA is proteolyzed in the wild-type strain and stabilized in the ΔspoT strain, as reported previously for abrupt starvation (30). DnaA levels in the Δppk1 strain are similar to wild-type levels (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Consistent with previous observations (19), CtrA in wild-type swarmer cells is stabilized during glucose exhaustion. However, CtrA in ΔspoT and Δppk1 swarmer cells is improperly proteolyzed under the same conditions (Fig. 4). These data indicate that ppGpp and polyP are either directly or indirectly involved in inhibiting CtrA proteolysis during glucose deprivation, which likely contributes to their inhibitory effect on replication initiation (Fig. 2E and 3C). We note that cyclic di-GMP has been previously shown to modulate CtrA proteolysis (12) and stalk development (35) as well; thus, both of these processes are reciprocally regulated by two guanine nucleotide second messengers: c-di-GMP, which promotes stalked-cell development, and ppGpp, which inhibits it.

Fig 4.

Regulation of CtrA levels in swarmer cells. (A, left) Anti-CtrA Western blots from a population of synchronized swarmer cells in nutrient-replete (M2G) medium. (Right) Anti-CtrA blots from a population of synchronized swarmer cells under glucose exhaustion conditions. See Fig. S1B in the supplemental material for images of a loading control band under each tested condition. The glucose exhaustion experiment was conducted in triplicate; representative blots are shown. (B) Quantification of CtrA levels in swarmer cells during glucose exhaustion from three independent experiments. For each strain, the signal intensity for each band was normalized to the signal intensity of the first time point.

We note that CtrA proteolysis is part of the DivK∼P-dependent developmental program: therefore, the effects of ppGpp and polyP on CtrA may be downstream of the effect of these molecules on DivJ localization.

Swarmer cells produce ppGpp at a higher rate than stalked cells upon starvation.

As ppGpp signaling is specifically important for inhibiting the development of swarmer cells, we predicted that swarmers and stalked cells might differentially accumulate ppGpp in starvation. To test whether differential rates of ppGpp synthesis occur between cell types, we incubated cells with KH232PO4 to label nucleotides and separated the swarmers and stalked cells, which were then glucose starved. ppGpp levels were monitored by TLC. In this experiment the “stalked” category includes early stalked to late predivisional cells. The data show that swarmer cells consistently accumulate ppGpp at a faster rate and to a greater extent than stalked cells upon glucose starvation (Fig. 5). A higher rate of ppGpp synthesis in swarmer cells relative to stalked cells provides an additional layer of regulation that may contribute to preferential inhibition of the swarmer-to-stalked transition upon nutrient limitation.

Concluding remarks.

In this work we demonstrate that exhaustion of glucose from the growth medium inhibits the developmental transition from swarmer to stalked cell type and that this phenomenon is regulated by the activity of two starvation-associated molecules: ppGpp and polyP. ppGpp signaling activates the proteolysis of DnaA (30), inhibits the localization of DivJ, and inhibits the proteolysis of CtrA. polyP production inhibits the localization of DivJ and the proteolysis of CtrA. Both ppGpp and polyP function to preferentially block the transition from swarmer to stalked-cell type relative to subsequent transitions of the cell cycle. It may be that ppGpp and polyP inhibit some factor upstream of DivJ localization, leading to inhibition of CtrA proteolysis through the canonical DivK∼P pathway (Fig. 1B). Future studies will be aimed at deciphering the detailed molecular mechanism by which ppGpp and polyP exert these effects.

This work establishes novel signaling functions for the starvation effectors ppGpp and polyP and shows that they can modulate cell cycle progression by inhibiting signaling events that occur only at the swarmer-to-stalked transition.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.C.B. was supported by NIH training grant 5T32GM007183-36. J.T.H. is supported by NIH Medical Scientist National Research Service Award 2T32GM007281-37. S.C. acknowledges support for this project from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (BYI) and the Mallinckrodt Foundation.

We thank Patrick Viollier and Aretha Fiebig for critical feedback on drafts of the manuscript and the labs of Lucy Shapiro and Christine Jacobs-Wagner for strains, plasmids, and antibodies.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print 21 October 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahn K, Kornberg A. 1990. Polyphosphate kinase from Escherichia coli. Purification and demonstration of a phosphoenzyme intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11734–11739 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berne C, Kysela DT, Brun YV. 2010. A bacterial extracellular DNA inhibits settling of motile progeny cells within a biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 77:815–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biondi EG, et al. 2006. Regulation of the bacterial cell cycle by an integrated genetic circuit. Nature 444:899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boutte CC, Crosson S. 2011. The complex logic of stringent response regulation in Caulobacter crescentus: starvation signalling in an oligotrophic environment. Mol. Microbiol. 80:695–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Britos L, et al. 2011. Regulatory response to carbon starvation in Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS One 6:e18179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collier J, Shapiro L. 2007. Spatial complexity and control of a bacterial cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18:333–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins TJ. 2007. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques 43:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Comolli LR, Kundmann M, Downing KH. 2006. Characterization of intact subcellular bodies in whole bacteria by cryo-electron tomography and spectroscopic imaging. J. Microsc. 223:40–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crooke E, Akiyama M, Rao NN, Kornberg A. 1994. Genetically altered levels of inorganic polyphosphate in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:6290–6295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curtis PD, Brun YV. 2010. Getting in the loop: regulation of development in Caulobacter crescentus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:13–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Domian IJ, Quon KC, Shapiro L. 1997. Cell type-specific phosphorylation and proteolysis of a transcriptional regulator controls the G1-to-S transition in a bacterial cell cycle. Cell 90:415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duerig A, et al. 2009. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 23:93–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ely B. 1991. Genetics of Caulobacter crescentus. Methods Enzymol. 204:372–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. England JC, Perchuk BS, Laub MT, Gober JW. 2010. Global regulation of gene expression and cell differentiation in Caulobacter crescentus in response to nutrient availability. J. Bacteriol. 192:819–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evinger M, Agabian N. 1977. Envelope-associate nucleoid from Caulobacter crescentus stalked and swarmer cells. J. Bacteriol. 132:294–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferullo DJ, Lovett ST. 2008. The stringent response and cell cycle arrest in Escherchia coli. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiebig A, Castro-Rojas CM, Siegal-Gaskins D, Crosson S. 2010. Interaction specificity, toxicity and regulation of a paralogous set of ParE/RelE-family toxin-antitoxin systems. Mol. Microbiol. 77:236–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorbatyuk B, Marczynski GT. 2001. Physiological consequences of blocked Caulobacter crescentus dnaA expression, an essential DNA replication gene. Mol. Microbiol. 40:485–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorbatyuk B, Marczynski GT. 2005. Regulated degradation of chromosome replication proteins DnaA and CtrA in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1233–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grula EA, Hartsell SE. 1954. Intracellular structures in Caulobacter vibrioides. J. Bacteriol. 68:498–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki RK. 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:7351–7367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hinz AJ, Larson DE, Smith CS, Brun YV. 2003. The Caulobacter crescentus polar organelle development protein PodJ is differentially localized and is required for polar targeting of the PleC development regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 47:929–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hogg T, Mechold U, Malke H, Cashel M, Hilgenfeld R. 2004. Conformational antagonism between opposing active sites in a bifuctional RelA/SpoT homolog modulates (p)ppGpp metabolism during the stringent response. Cell 117:57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hung DY, Shapiro L. 2002. A signal transduction protein cues proteolytic events critical to Caulobacter cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:13160–13165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishige K, Zhang H, Kornberg A. 2002. Polyphosphate kinase (PPK2), a potent, polyphosphate-driven generator of GTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:16684–16688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumble KD, Ahn K, Kornberg A. 1996. Phosphohistidyl active sites in polyphosphate kinase of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:14391–14395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuroda A, Murphy H, Cashel M, Kornberg A. 1997. Guanosine tetra- and pentaphosphate promote accumulation of inorganic polyphosphate in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:21240–21243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuroda A, et al. 2001. Role of inorganic polyphosphate in promoting ribosomal protein degradation by the Lon protease in E. coli. Science 293:705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lam H, Matroule JY, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2003. The asymmetric spatial distribution of bacterial signal transduction proteins coordinates cell cycle events. Dev. Cell 5:149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lesley JA, Shapiro L. 2008. SpoT regulates DnaA stability and initiation of DNA replication in carbon-starved Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 190:6867–6880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marks ME, et al. 2010. The genetic basis of laboratory adaptation in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 192:3678–3688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matroule JY, Lam H, Burnette DT, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2004. Cytokinesis monitoring during development; rapid pole-to-pole shuttling of a signaling protein by localized kinase and phosphatase in Caulobacter. Cell 118:579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meisenzahl AC, Shapiro L, Jenal U. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a xylose-dependent promoter from Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 179:592–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paul R, et al. 2008. Allosteric regulation of histidine kinases by their cognate response regulator determines cell fate. Cell 133:452–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paul R, et al. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 18:715–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poindexter JS. 1981. Oligotrophy: fast and famine existence. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 5:63–89 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poindexter JS, Staley JT. 1996. Caulobacter and Asticcaculis stalk bands as indicators of stalk age. J. Bacteriol. 178:3939–3948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Poindexter JS. 1984. Role of prostheca development in oligotrophic aquatic bacteria, p. 33–40. In Klug MJ, Reddy CA. (ed.), Current perspectives in microbial ecology. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quon KC, Yang B, Domian IJ, Shapiro L, Marczynski GT. 1998. Negative control of bacterial DNA replication by a cell cycle regulatory protein that binds at the chromosome origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:120–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radhakrishnan SK, Pritchard S, Viollier PH. 2010. Coupling prokaryotic cell fate and division control with a bifunctional and oscillating oxidoreductase homolog. Dev. Cell 18:90–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radhakrishnan SK, Thanbichler M, Viollier PH. 2008. The dynamic interplay between a cell fate determinant and a lysozyme homolog drives the asymmetric division cycle of Caulobacter crescentus. Genes Dev. 22:212–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shiba T, et al. 1997. Inorganic polyphosphate and the induction of rpoS expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:11210–11215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thanbichler M, Iniesta AA, Shapiro L. 2007. A comprehensive set of plasmids for vanillate- and xylose-inducible gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thanbichler M, Shapiro L. 2006. Chromosome organization and segregation in bacteria. J. Struct. Biol. 156:292–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thanbichler M, Shapiro L. 2006. MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell 126:147–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Traxler MF, et al. 2008. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 68:1128–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsokos CG, Perchuk BS, Laub MT. 2011. A dynamic complex of signaling proteins uses polar localization to regulate cell-fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Dev. Cell 20:329–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Viollier PH, Shapiro L. 2004. Spatial complexity of mechanisms controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:572–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Viollier PH, Sternheim N, Shapiro L. 2002. Identification of a localization factor for the polar positioning of bacterial structural and regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:13831–13836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Viollier PH, et al. 2004. Rapid and sequential movement of individual chromosomal loci to specific subcellular locations during bacterial DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:9257–9262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wheeler RT, Shapiro L. 1999. Differential localization of two histidine kinases controlling bacterial cell differentiation. Mol. Cell 4:683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xiao H, et al. 1991. Residual guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5980–5990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhou YN, et al. 2008. Regulation of cell growth during serum starvation and bacterial survival in macrophages by the bifunctional enzyme SpoT in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 190:8025–8032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.