Abstract

Libraries of 16S rRNA genes cloned from methanogenic oil degrading microcosms amended with North Sea crude oil and inoculated with estuarine sediment indicated that bacteria from the genera Smithella (Deltaproteobacteria, Syntrophaceace) and Marinobacter sp. (Gammaproteobacteria) were enriched during degradation. Growth yields and doubling times (36 days for both Smithella and Marinobacter) were determined using qPCR and quantitative data on alkanes, which were the predominant hydrocarbons degraded. The growth yield of the Smithella sp. [0.020 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C)], assuming it utilized all alkanes removed was consistent with yields of bacteria that degrade hydrocarbons and other organic compounds in methanogenic consortia. Over 450 days of incubation predominance and exponential growth of Smithella was coincident with alkane removal and exponential accumulation of methane. This growth is consistent with Smithella's occurrence in near surface anoxic hydrocarbon degrading systems and their complete oxidation of crude oil alkanes to acetate and/or hydrogen in syntrophic partnership with methanogens in such systems. The calculated growth yield of the Marinobacter sp., assuming it grew on alkanes, was [0.0005 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C)] suggesting that it played a minor role in alkane degradation. The dominant methanogens were hydrogenotrophs (Methanocalculus spp. from the Methanomicrobiales). Enrichment of hydrogen-oxidizing methanogens relative to acetoclastic methanogens was consistent with syntrophic acetate oxidation measured in methanogenic crude oil degrading enrichment cultures. qPCR of the Methanomicrobiales indicated growth characteristics consistent with measured rates of methane production and growth in partnership with Smithella.

Introduction

Methanogenic degradation of pure hydrocarbons and hydrocarbons in crude oil proceeds with stoichiometric conversion of individual hydrocarbons to methane and CO2. (Zengler et al., 1999; Anderson and Lovley, 2000; Townsend et al., 2003; Siddique et al., 2006; Gieg et al., 2008; 2010; Jones et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Comparison of methanogenic degradation of crude oil in estuarine sediment microcosms with patterns of hydrocarbon removal in degraded petroleum reservoirs has suggested that preferential removal of alkanes in biodegraded petroleum reservoirs is driven by methanogenesis and is probably responsible for the formation of the world's deposits of heavy oil (Jones et al., 2008). It has even been proposed that stimulation of in situ methanogenic biodegradation of crude oil may be harnessed to enhance energy recovery from petroleum reservoirs (Gieg et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2008; Gray et al., 2009; Mbadinga et al., 2011). From a wider perspective hydrocarbons are common contaminants of surface and shallow environments (Keith and Telliard, 1979; Hippensteel, 1997) and in situ methanogenic biodegradation of crude oil is an important component of the attenuation of contaminant plumes in such environments (Gray et al., 2010).

A meta-analysis of microbial communities in hydrocarbon impacted environments has indicated that communities in near surface sediments are distinct from those found in deeper warmer petroleum reservoirs (Gray et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). On this basis the estuarine system studied by Jones and colleagues (2008) best represents a model for direct comparison with near surface hydrocarbon impacted environments contaminated with crude oil. In comparison with pure hydrocarbons, crudeoils contain a complex mixture of chemicals including refractory and or toxic components in addition to degradable hydrocarbons. This complexity is likely to influence the activity and selection of alkane degrading microorganisms enriched on crude oil. Here we have determined the relative importance of different organisms potentially involved in methanogenic crude oil degradation in surface sediments by quantification of their growth in relation to methane production and removal of crude oil alkanes.

Results

Methanogenic oil degradation

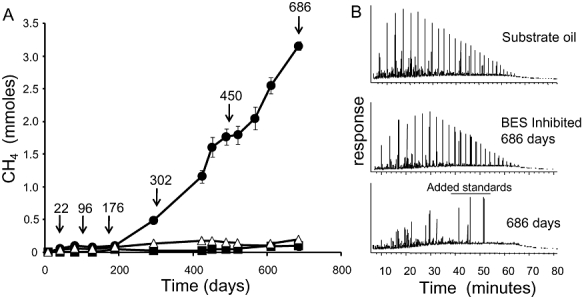

Oil conversion to methane in oil degrading microcosms inoculated with estuarine sediment and amended with North Sea oil was confirmed by comparison of methane yields and oil alterations in oil amended, unamended and (BES) inhibited control microcosms (Fig. 1). Methanogenic oil degradation was characterized by an apparent 200 day lag phase (Fig. 1A). Methane production correlated stoichiometrically with the removal of alkanes (nC7-nC34) (Jones et al., 2008, Fig. 1B). Furthermore, near complete degradation of alkanes occurred before any significant removal of aromatic hydrocarbon (Jones et al., 2008). Microcosms sacrificially sampled after 0, 22, 176, 302, 450 and 686 days for analysis of residual crude oil were also used for analysis of the microbial communities present.

Fig. 1.

A. Methane production from 300 mg North Sea crude oil added to estuarine sediments incubated under methanogenic conditions in laboratory microcosms (100 ml) for 686 days. The error bars show ±1 × standard error (n = 3). Closed circles indicate methane production from crude oil amended microcosms and open triangles indicate methane production from microcosms, which did not receive crude oil (data previously presented in Jones et al., 2008). Closed squares indicate methane production from crude oil and BES amended microcosms. Arrows indicate sacrificial sampling events at 22, 176, 302, 450 and 686 days.

B. Gas chromatograms of total hydrocarbon fractions from the undegraded substrate oil, crude oil amended and crude oil and BES amended microcosms incubated for 686 days. Time 0 on the chromatograms, which are displayed from 5 to 80 min, corresponds to injection.

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis of bacterial and archaeal communities

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of the microbial communities in replicate microcosms over time demonstrated reproducible changes associated with degradation of the crude oil and methane formation relative to control microcosms with no oil added. There was a high degree of similarity in the DGGE profiles of communities from replicate microcosms that were sacrificially sampled at different time points (Table 1). On day 22 there was no significant difference in the bacterial or archaeal community profiles between treatments; whereas, at 302 and 686 days there were statistically significant differences between treatments in both the bacterial and archaeal communities (Table 1, Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Average similarity between bacterial and archaeal DGGE profiles from methanogenic microcosms

| Bacterial profiles | Archaeal profiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (days) | Similarity within replicates | Similarity between oil and no-oil treatments | Similarity within replicates | Similarity between oil and no-oil treatments |

| 22 | 84.7 ± 5.1 | 79.4 ± 4.5 | 80.8 ± 5.0 | 75.1 ± 4.1 |

| 302 | 79.1 ± 7.2* | 32.7 ± 4.7* | 73.3 ± 3.4* | 57.3 ± 1.1* |

| 686 | 72.8 ± 1.6* | 36.9 ± 5.8* | 81.1 ± 3.8* | 40.3 ± 3.8* |

The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between oil treated and untreated samples (t-test P < 0.05).

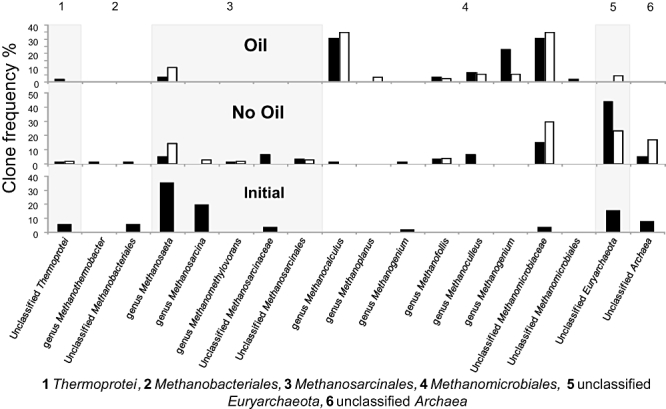

Bacterial and archaeal community composition in Tyne sediment inoculum

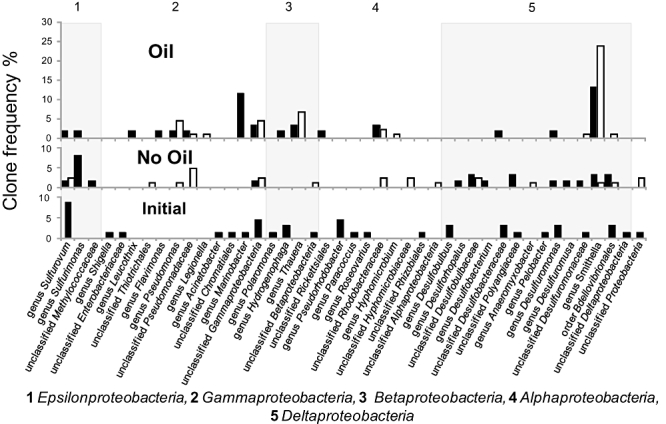

More detailed bacterial community analysis was conducted on microcosm samples from day 22, 302 and 686 using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries (see Fig. 2 legend for individual library sizes). Clone libraries for individual samples were prepared on the basis that there was high similarity between DGGE profiles from replicate samples and therefore individual samples were considered to be representative. 16S rRNA sequences from the sediment microcosms were classified using the RDP Naïve Bayesian rRNA Classifier (Wang et al., 2007). Samples taken on day 22 and from the sediment inoculum were compared using the RDP library compare tool and were found not to be significantly different for the bacterial or archaeal genera (P > 0.05). The 16S rRNA sequence data from these samples were considered together and are referred to as the initial community [Fig. 2 (Proteobacteria), Fig. 3. (Archaea), Fig. S2 (all other bacterial taxa)]. The closest matches to the 16S rRNA sequences in the EMBL database were recovered from lake, estuarine, marine, mangrove and cold seep sediments as well as sequences recovered from anaerobic sludges and soil (data not shown). A number of these bacterial or archaeal sequences were most closely related to organisms previously identified in polluted sediments including those contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (c. 14%, accession numbers GU996598, GU996609, GU996619, GU996620, GU996621, GU996627, GU996629, GU996634, GU996635, GU996636, GU996659, GU996660, GU996663, GU996690, GU996691, GU996693, GU996712 in Figs 5 and 7). These data are consistent with the long industrial history of the river Tyne, which was the first major coal exporting port to develop during the industrial revolution. The most frequently recovered archaeal sequences were from the genus Methanosaeta (35.3% of clones) and the genus Methanosarcina (19.6% of clones) both from the order Methanosarcinales (Fig. 3, bottom panel). Methanomicrobiales and Methanobacteriales together comprised only 11.7% of clones.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic affiliation of proteobacterial 16S rRNA sequences recovered from methanogenic microcosms. Clone frequency in bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from the inoculum and initial day 22 samples (bottom panel, total number of clones = 71) and in samples from methanogenic oil degrading microcosms (top panel, number of ‘day 302’ clones = 61, number of ‘day 686’ clones = 87) and control microcosms with no added oil (middle panel, number of ‘day 302’ clones = 62, number of ‘day 686’ clones = 87). Data from clone libraries from day 302 (filled bars) and day 686 (open bars) are shown. Clones were grouped into categories based on their genus, order, class or phylum level affiliation after phylogenetic analysis with the ARB software package using an RDP guide tree. The affiliation of individual sequences was cross-checked using the RDP taxonomical hierarchy with the Naïve Bayesian rRNA Classifier Version 2.0, July 2007.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic affiliation of archaeal 16S rRNA sequences recovered from methanogenic microcosms. Clone frequency distributions in archaeal 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from the inoculum and initial day 22 samples (bottom panel) and in samples from the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms (top panel) and control microcosms with no added oil (middle panel). Data from clone libraries from day 302 (filled bars) and day 686 (open bars) are shown. Clones were grouped into categories based on their genus, order, class or phylum level affiliation after phylogenetic analysis with the ARB software package using an RDP guide tree. The affiliation of individual sequence was cross-checked using the RDP Taxonomical hierarchy with the Naive Bayesian rRNA Classifier Version 2.0, July 2007.

Fig. 5.

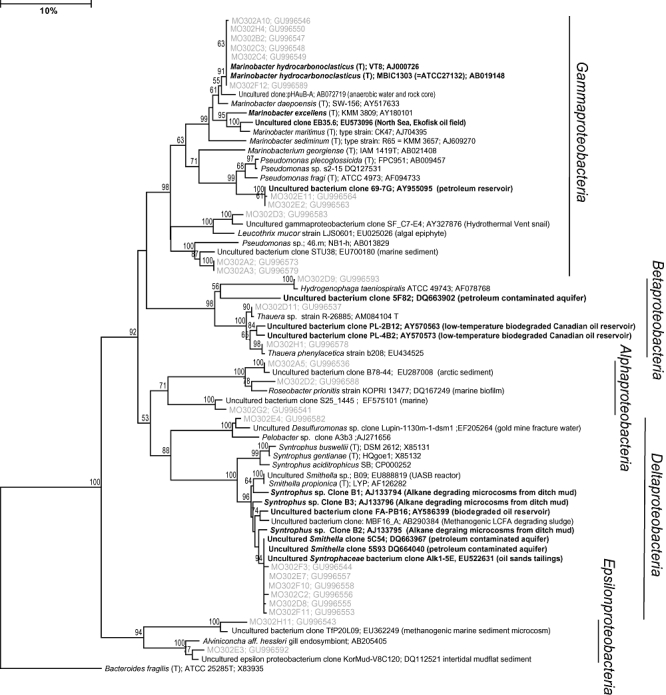

Phylogenetic distance trees based on comparative analysis of Proteobacterial partial 16S rRNA sequences recovered from a representative oil amended microcosm on day 302. Sequences recovered in this study (grey text) are prefixed by MO302. Related organisms identified in petroleum systems or those directly implicated in oil degradation are in bold. GenBank accession numbers for all database sequences are provided in parenthesis. Tree rooted with respect to the Bacteroides fragilis ATCC 25285T, 16S rRNA sequence (X83935). The scale bar denotes 10% sequence divergence and the values at the nodes indicate the percentage of bootstrap trees that contained the cluster to the right of the node. Bootstrap values less than 50 are not shown.

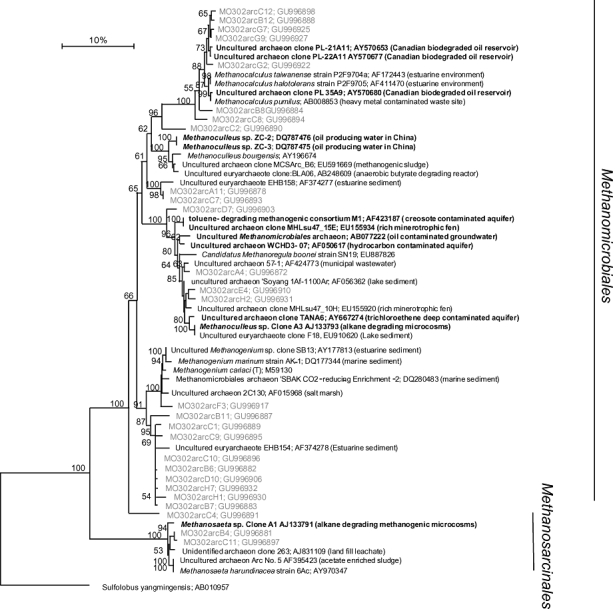

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic distance tree based on the comparative analysis of archaeal partial 16S rRNA sequences recovered from a representative oil amended microcosm on day 302. Sequences recovered in this study (grey text) are prefixed by MO302. Related organisms identified in petroleum systems or those directly implicated in oil degradation are in bold. GenBank accession numbers for all database sequences are provided in parenthesis. Tree rooted with respect to the Sulfolobus yangmingensis 16S rRNA sequence (AB010957). The scale bar denotes 10% sequence divergence and the values at the nodes indicate the percentage of bootstrap trees that contained the cluster to the right of the node. Bootstrap values less than 50 are not shown.

Structure and dynamics of bacterial communities during methanogenic crude oil biodegradation

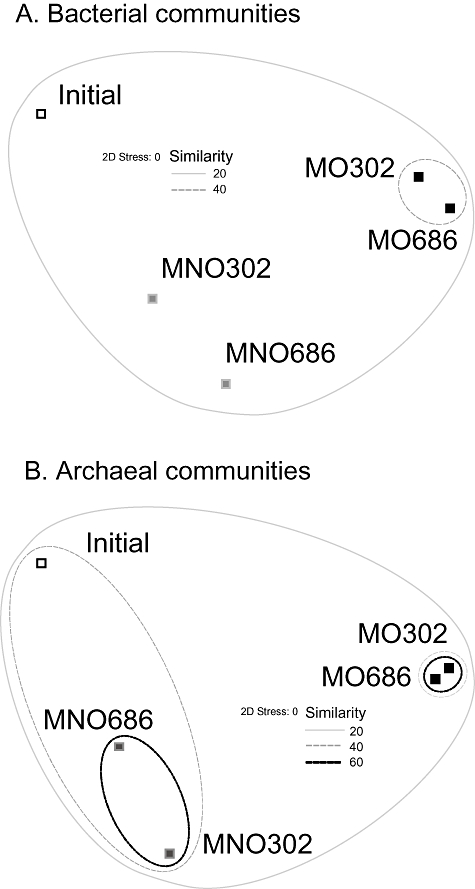

Consistent with the DGGE analysis of replicate samples, sequences from methanogenic oil degrading microcosms incubated for 302 and 686 days indicated major changes in the bacterial communities compared with the initial and unamended microcosm communities [Fig. 2 (Proteobacteria) and Fig. S2 (all other bacterial taxa)]. Ordination of 16S rRNA gene clone frequency data by non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) indicated that methanogenic oil degrading communities from independent microcosms, sampled on day 302 and day 686 clustered together (Fig. 4A). The similarity of the day 302 and 686 communities (which were obtained from separate, sacrificially sampled microcosms) was also observed in DGGE analysis of replicate samples and supports the notion that the clone library data are genuinely representative. The SIMPER routine in PRIMER 6 (Clarke and Warwick, 2001) was used to determine the contribution of different operational taxonomic units (OTUs) to the average similarity of oil-treated microcosms. This discrimination tool identified the deltaproteobacterial genus Smithella as the largest contributor (16%) to the overall similarity of the oil amended communities. The representation of this taxon was significantly greater in clone libraries from the oil degrading microcosms on day 302 and 686 compared with the initial community where it was not detected (RDP library compare tool P = 0.002 and < 0.001 respectively) and compared with unamended control microcosms sampled on day 302 and 686 (P = 0.004 and < 0.001). Sequences from the gammaproteobacterial genus Marinobacter were significantly enriched in oil-treated microcosms on day 302 relative to the initial community and unamended controls (RDP library compare tool P = 0.004 and 0.007). However, Marinobacter sequences were no longer detected in samples from day 686. In addition to Smithella and Marinobacter, other taxa, notably Thauera (Proteobacteria) and Anaerolinea (Chloroflexi), were enriched but to a lesser extent in the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms (Fig. 2 (Proteobacteria) and Fig. S2 (all other bacterial taxa)). Many of the sequences recovered at high frequency in clone libraries from methanogenic oil degrading microcosms, including Smithella and Marinobacter, were found to be most closely related to organisms directly implicated in petroleum degradation [Fig. 5 (Proteobacteria) and Fig. S3 (all other bacterial taxa)].

Fig. 4.

Non-metric MDS analysis of the bacterial and archaeal communities present in the River Tyne sediment at the start of the incubation period (Initial) and after 302 and 686 days based on OTU frequencies in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries. MDS plots are representations of how different the communities are from each other based on clustering of like samples. Similarity contour lines from cluster analyses are superimposed on to the MDS plots; however, only contours encompassing more than one clone library profile are shown. The MO302 and MO686 symbols indicate the oil amended microcosms and MNO302 and MNO686 symbols indicate the unamended microcosms.

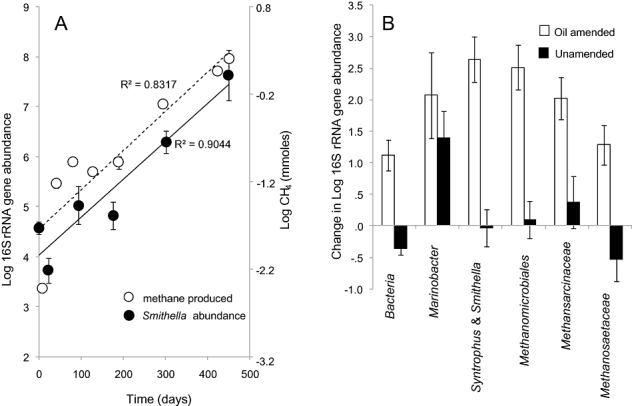

On the basis of increased representation in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries a qPCR analysis targeting Smithella and related Syntrophus spp. within the family Syntrophaceae was used to determine 16S rRNA gene abundances in triplicate samples taken on day 22, 94, 176, 302, 450 and 686. The qPCR data for Smithella/Syntrophus gave an excellent fit (R2 = 0.9) to an exponential growth model up to 450 days (Fig. 6A). In this model (NT = N0eµt) NT is the abundance of Smithella/Syntrophus at time T, N0 is the abundance of Smithella/Syntrophus at time T0. t is time in days and µ is the specific growth rate (day−1). Exponential growth coincided with the exponential increase in methane produced during the same time period (Fig. 6A). The average increase in abundance of Smithella/Syntrophus between the early phase of hydrocarbon degradation (0–176 days) and the following period (176–450 days) was 2.64 ± 0.41 log units [Figs 6B, P < 0.001; two-tailed t-test (assuming unequal variance)]. Changes in abundance were not significant over the same time period in the unamended microcosms (Fig. 6B). The specific growth rate, doubling time and growth yield on crude oil alkanes for Smithella/Syntrophus were calculated between day 0 and 450 days. The specific growth rate (µ) was 0.019 day−1 corresponding to a doubling time of 36 days and the growth yield was 0.020 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C) assuming that it was responsible for all alkane degradation.

Fig. 6.

A. Smithella/Syntrophus 16S rRNA gene abundances (log gene abundance/cm3) (closed circles) and log methane produced (open circles) in the oil degrading microcosms from 0 to 450 days. B. Average differences in 16S rRNA gene abundance (log gene abundance/cm3) between the lag phase (0–176 days) and the period of highest methane production (176–450 days) for the taxonomic groups targeted by qPCR assays. A value of zero indicates no change, a positive value indicates an increase in abundance and a negative value a decrease. Error bars represent 1 × SE.

qPCR data for Marinobacter gave a weaker fit (R2 = 0.61) to an exponential growth model between day 0 and 450 days (data not shown). Log gene abundance of the Marinobacter spp. targeted by the qPCR assay increased by 2.1 ± 0.68 log units in the oil amended microcosms ((P = 0.021, two-tailed t-test assuming unequal variance). In contrast to Smithella/Syntrophus, Marinobacter gene abundance also increased in the unamended microcosms by 0.78 ± 0.31 log units (P = 0.02, two-tailed t-test assuming unequal variance). The specific growth rate (µ) calculated for Marinobacter sp. in the amended microcosms was similar to that determined for Smithella/Syntrophus (0.019 day−1; doubling time 36 days). However, the initial log of gene abundance (copies/cm3) of Marinobacter (3.25 ± 0.29) was more than an order of magnitude lower than Smithella/Syntrophus (4.57 ± 0.13) and the estimated growthyields for Marinobacter was only 0.0005 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C) if one assumes that it was responsible for all alkane degradation.

The structure and dynamics of archaeal communities during methanogenic crude oil biodegradation

Major changes in archaeal communities were noted in methanogenic oil degrading microcosms, specifically there was a significant increase in Methanomicrobiales-related sequences relative to the initial community and all unamended control microcosms (P < 0.001 RDP library compare tool; Fig. 3). Ordination of OTU frequency data by MDS showed the same pattern of separation based on oil treatment as observed for the bacteria (Fig. 4). SIMPER analysis demonstrated that Methanocalculus sequences and unclassified Methanomicrobiaceae each contributed 29% towards the similarity of the oil degrading libraries. For all clone library comparisons the enrichment of Methanocalculus was highly significant in the oil degrading microcosms (P < 0.001; RDP library compare tool). Phylogenetic analysis of the archaeal sequences recovered from the oil degrading microcosms (Fig. 7) showed that many were closely related to organisms identified in petroleum systems or those directly implicated in oil degradation. Microcosms that were not treated with crude oil were dominated by unclassified Euryarchaeota, unclassified Archaea, unclassified Methanomicrobiaceae and Methanosaeta sequences (Fig. 3).

Archaeal gene abundances increased significantly in the oil amended microcosms between 0–176 days and 176–450 days. For instance, the log gene abundance of Methanomicrobiales increased by 2.51 ± 0.54 log units in the oil amended microcosms (P = 0.004; two-tailed t-test assuming unequal variance); Methanosarcinaceae increased by 2.0 ± 0.33 log units (P < 0.001) and Methanosaetaceae increased by 1.29 ± 0.31 log units (P = 0.03). Changes in archaeal abundance in the unamended microcosms were not significant.

The degree of enrichment of Methanomicrobiales was not significantly different to that observed for Methanosarcinaceae and was therefore less than might have been expected given the relative increase in the frequency of Methanomicrobiales sequences observed in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from day 302 and 686 (Fig. 3). The qPCR data for the different methanogen groups were a good fit to an exponential growth model between 0 and 450 days (data not shown) with R2 values of 0.92, 0.78 and 0.73 for the Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae respectively. The respective growth yields (assuming the contribution of individual methanogen groups to methane production from alkane removal was proportionate to their relative abundances) were 0.009–0.036, 2–2.2 × 10−3 and 3.0–3.5 × 10−6 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C) (see experimental procedures for explanation of the range of values). The total methanogen growth yield calculated from the combined growth of all three methanogen groups on alkane removed was 0.011–0.038 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C). Expressed in terms of moles of methane produced the individual growth yields were 0.141–0.565, 0.031–0.035, 4.6–5.5 × 10−5 g(cell-C)/mol (CH4) and the total methanogen growth yield was 0.17–0.6 g(cell-C)/mol (CH4). Calculated specific growth rates were 0.02, 0.01 and 0.01 day−1 respectively. Doubling times for Methanomicrobiales were 34 days whereas the Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae required 69 days.

Pathways of acetate-stimulated methanogenesis in methanogenic oil degrading microcosms

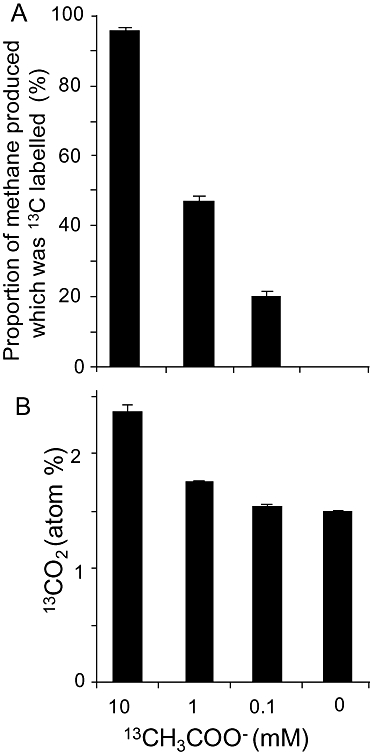

To determine the fate of acetate during methanogenesis subsamples from the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms were treated with 2-13C sodium acetate and production of 13CO2, 13CH4 and 12CH4 were compared with unamended controls. Maximum total methane production rates from acetate were 33.8 ± 0.36 nmoles h−1, 2.6 ± 0.2 nmoles h−1, 2.3 ± 0.1 nmoles h−1, 0.06 ± 0.01 nmoles h−1 in experiments to which 10, 1, 0.1 or 0 mM 2-13C sodium acetate were added. Theoretically the direct cleavage of 99 atom% 2-13C acetate to methane and CO2 by acetoclastic methanogens (Table 2, Eq. 1) should produce 100% 13CH4 with no production of 13CO2. However, if the principal sink for acetate was syntrophic actetate oxidation (Table 2, Eq. 2) coupled to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (Table 2, Eq. 3) a lower proportion of 13CH4 methane would be produced because the 13CO2 from syntrophic acetate oxidation (SAO) would be diluted with 12C from the carbonate buffered medium, before reduction of CO2 to methane. The proportion of 13CH4 from 13CH3COO- was lower than 100% (Fig. 8A) indicating that SAO was occurring in the methanogenic oil degrading system. In addition to the production of unlabelled methane, SAO was confirmed by the formation of 13CO2 above natural abundance from oxidation of C-2 of the labelled acetate to 13CO2 (Fig. 8B).

Table 2.

Reactions involved in the methanogenic degradation of alkanes (hexadecane)

| Process | Reaction | Eq. |

|---|---|---|

| Acetoclastic methanogenesis | CH3COO- + H+→ CH4 + CO2 | 1 |

| Syntrophic acetate oxidation (SAO) | CH3COO- + H+ + 2H2O → 4H2 + CO2 | 2 |

| Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis | 4H2 + CO2→ CH4 + 2H2O | 3 |

| Syntrophic alkane oxidation to acetate and hydrogen | 4C16H34 + 64H2O → 32CH3COO- + 32H+ + 68H2 | 4 |

| Alkane degradation to methane | 4C16H34 + 30H2O → 15CO2 + 49CH4 | 5 |

Fig. 8.

(A) Proportion of 13CH4 and 12CH4 and (B) proportion of 13CO2 (atom %) in the headspace of methanogenic oil degrading enrichments amended with different concentrations of 2-13C sodium acetate (10, 1, 0.1 mM). Error bars represent 1 × SE.

The proportion of 13CH4 production compared with total CH4 production was dependent on the initial concentration of acetate (Fig. 8A). With 0.1 mM 13CH3COO-, 20% of the methane produced was labelled indicating acetoclastic methanogenesis was a minor component of biogenic methane production; however, with 1 mM 13CH3COO-, approximately 50% of the methane produced was labelled and with 10 mM 13CH3COO-, most of the methane produced was 13C-labelled (Fig. 8A). Despite the high proportion of labelled methane production in experiments amended with 10 mM 13CH3COO- and the likely dominance of acetoclastic methanogenesis in this system, there was a statistically significant production of 13CO2 above that observed in the unamended controls (Fig. 8B, P < 0.001, t-Test). This was also true of experiments with 1 mM 13CH3COO- (P = 0.014). However, despite the lower proportion of labelled methane found in the experiments amended with 0.1 mM acetate, indicating SAO, incorporation of label into CO2 was not significantly different from the unamended controls (P > 0.05). This is most likely explained by the absolute amounts of 13CH3COO- present that differed by three orders of magnitude and thus the low absolute 13CO2 yield relative to the background dissolved inorganic carbon pool in the carbonate buffered nutrient medium (30 mM).

Discussion

During the methanogenic degradation of crude oil, alkanes are oxidized syntrophically to methanogenic substrates (Table 2, Eq. 4), which are in turn converted to methane and CO2 (Table 2, Eqs 1, 2 and 3). The overall reaction for the degradation of n-alkanes (e.g. hexadecane, Table 2, Eq. 5) in oil amended microcosms was confirmed by generation of stoichiometric amounts of methane (Jones et al., 2008). Syntrophic oxidation of acetate to H2 and CO2 (Table 2, Eq. 2) during conversion of alkanes in crude oil to methane, has been suggested as an alternative to acetoclastic methanogenesis (Table 2, Eq. 1) and Rayleigh fractionation modelling has indicated that within petroleum reservoirs, a large proportion of the acetate generated from hydrocarbon degradation can be channelled through SAO (Jones et al., 2008).

The role of Syntrophaceae in low temperature hydrocarbon degrading systems

16S rRNA gene clone libraries and qPCR indicated an important role for bacteria related to the genera Smithella and Syntrophus in methanogenic crude oil degrading consortia. The relationship between Smithella and Syntrophus is at present unclear with 16S rRNA sequences from uncultured bacteria designated as Syntrophus sp. clustering with those named as Smithella (Fig. 5). However, our phylogenetic analysis provides strong bootstrap support (100%) for the separation of Smithella propionica and related sequences from uncultured organisms (including those enriched in this study) from cultured Syntrophus spp. On the basis of this analysis the Syntrophaceae sequences (e.g. MO302D8) enriched in the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms are considered to represent Smithella spp. Furthermore, we propose that the sequences designated as Syntrophus (Clones B1, B2 and B3) from a methanogenic hexadecane degrading enrichment (Zengler et al., 1999) also represent Smithella sp.. These organisms were named as Syntrophus sp. because the genus Smithella was not described at the time of Zengler and colleagues work (Liu et al., 1999).

A number of strands of evidence from this study and the wider literature provide collective evidence for a direct role for Syntrophaceae in the activation and oxidation of crude oil alkanes via long chain fatty acids (LCFA) to acetate and hydrogen in methanogenic environments. First, the calculated growth yield [0.02 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C)] for the enriched Smithella species when added to the maximum methanogen growth yield [0.038 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C)] is consistent [0.058 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C)] with a quantitatively important role for Syntrophaceace in the degradation of alkanes in the oil degrading microcosms. For comparison, growth yields for methanogenic consortia growing on various organic compounds range from 0.02 to 0.1 g(cell-C)/g(substrate-C). [values from the literature were recalculated in terms of g(cell-C)/g(substrate-C) to allow direct comparison with our results]. These substrates include formate (0.02, Dolfing et al., 2008a), benzoate (0.038, Auburger and Winter, 1995), lactate (0.055, Walker et al., 2009), glycerol (0.08, Qatibi et al., 1998), pyruvate (0.09, Walker et al., 2009), xylene (0.09, Edwards and Grbić-Galić, 1994), Toluene (0.1, Edwards and Grbić-Galić, 1994). With respect to the thermodynamics of alkane degradation in the crude oil degrading microcosms the combined growth yield should be most comparable with those found for toluene and xylene. When normalized for the number of carbon atoms, these compounds have free energy yields [toluene, −18.7 KJ mol−1 carbon and xylene −21.1 KJ mol−1 carbon (Edwards and Grbić-Galić, 1994)], which are similar to those calculated for alkanes (Dolfing et al., 2008b) i.e. C8-C80 alkanes (−23.1 to –23.4 KJ mol−1 carbon). The small discrepancy between the growth yields we have calculated and those for methanogenic degradation of toluene or xylene may be explained by our assumption in growth yield calculations that Smithella was responsible for the degradation of all alkanes to acetate and H2. In reality, the oil degrading microcosms contained a range of bacteria some of which may have utilized a proportion of the alkanes degraded.

Another strand of evidence implicating Smithella in methanogenic crude oil degradation is the large number of studies that have identified Syntrophaceae as dominant organisms in hydrocarbon impacted systems (e.g. Dojka et al., 1998; Zengler et al., 1999; Bakermans and Madsen, 2002; Kasai et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2007; Shimizu et al., 2007; Ramos-Padrón et al., 2011; Figs 2 and 5; Table 3). With the exception of the study of Shimizu and colleagues (2007), all these studies were of near surface soils, sediments, oil tailings ponds or aquifers. Critically, the association of a specific subgroup of the genus Smithella (Fig. 5) with anaerobic hydrocarbon environments suggests that these Smithella may be directly involved in the degradation of the hydrocarbons present. S. propionica, the only Smithella sp. in pure culture, is not known to degrade LCFA but in common with many other syntrophic bacteria it does degrade compounds such as acetate, propionate or butyrate. These short chain fatty acids are ubiquitous intermediates in organic matter degradation in all anoxic environments and as such these substrates are less likely to be drivers for the selection of one specific group of syntrophic bacteria. The consistent association of Smithella spp. with hydrocarbon impacted environments therefore implies that they are not selected simply by short chain fatty acids produced from alkane oxidation, but rather specifically because they have the ability to degrade hydrocarbons.

Table 3.

A survey of oil and hydrocarbon associated Syntrophaceae.a

| Study reference | Clone/strain | Accession | Source environment | Region | %b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | MO302D8 | GU996555 | Methanogenic hydrocarbon degrading enrichment | UK | 100 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | Alk1-5E | EU522631 | Methanogenically degrading oil sands tailings | Canada | 99 |

| Allen et al. (2007) | Clone 5C54 | DQ663967 | Hydrocarbon contaminated sediments | Canada | 99 |

| Zengler et al. (1999) | Clone B2 | AJ133795 | Methanogenic hexadecane degrading consortium (ditch mud) | Germany | 98 |

| Hatamoto et al. (2007) | Clone : MBF16_A | AB290384 | Methanogenic LCFA degrading sludge | Japan | 97 |

| Grabowski et al. (2005) | FA-PB16 | AY586399 | Oil field production water degrading LCFAs methanogenically | Canada | 94 |

| Shimizu et al. (2007) | YWB12 | AB294281 | Methanogenic Coal seam groundwater | Japan | 94 |

| Shimizu et al. (2007) | YWB13 | AB294282 | Methanogenic Coal seam groundwater | Japan | 94 |

| She and Zhang (Genbank)c | DQ315-22 | EU050698 | Oil field production water | China | 93 |

| Zengler et al. (1999) | B1 | AJ133794 | Methanogenic hexadecane degrading consortium | Germany | 93 |

| Dojka et al. (1998) | WCHB1-12 | AF050534 | hydrocarbon contaminated aquifer | USA | 93 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | Alk2-2B | EU522633 | Degrading oil sands tailings | Canada | 93 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | MLSB_6 m_11C_B | EF420213 | Degrading oil sands tailings | Canada | 93 |

| Zengler et al. (1999) | B3 | AJ133796 | Methanogenic hexadecane degrading consortium | Germany | 93 |

| Grabowski et al. (2005) | FA-PB5 | AY586395 | Oil field production water | Canada | 92 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | BTEX1-10B | EU522637 | Oil sands tailings enrichment culture | Canada | 92 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | Nap2-2C | EU522636 | Oil sands tailings enrichment culture | Canada | 91 |

| Jackson et al. (1999) | S. aciditrophicus | U86447 | Sewage treatment plant | USA | 91 |

| Penner et al. (Genbank)c | LCA1-1C | EU522632 | Oil sands tailings enrichment culture | Canada | 91 |

| Bakermans and Madsen (2002) | 12–2 | AF351212 | Coal-tar-waste-contaminated aquifer | USA | 90 |

| Bakermans and Madsen (2002) | 8–45 | AF351238 | Coal-tar-waste-contaminated aquifer | USA | 90 |

| Bakermans and Madsen (2002) | 36–11 | AF351220 | Coal-tar-waste-contaminated aquifer | USA | 90 |

| Brofft et al. (2002) | FW99 | AF523966 | Coal impacted wetland | USA | 90 |

| Gieg et al. (2008) | lg1d02 | EU037972 | Gas condensate-contaminated aquifer | USA | 89 |

| Orcutt et al. (Genbank)c | GoM161_Bac20 | AM745136 | Oil impacted sediments | Marine | 89 |

| Winderl et al. (2008) | D25_29 | EU266903 | Hydrocarbon contaminated aquifers | Germany | 89 |

| Winderl et al. (2008) | D25_39 | EU266912 | Hydrocarbon contaminated aquifers | Germany | 89 |

| She and Zhang (Genbank)c | DQ315-4 | EU050697 | Oil field production water | China | 89 |

| Kasai et al. (2005) | clone:BSC50 | AB161292 | Hydrocarbon contaminated soils | Japan | 87 |

| Chauhan and Ogram (2006) | F1A25 | DQ201587 | Acetate utilizing microorganisms in soil | USA | 87 |

Family level assignment based on RDP taxonomic classification.

% sequence identity with the MO302D8 (this study) determined by BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990).

No accompanying journal publication.

Additional support for enrichment of the Smithella on crude oil alkanes comes from the known physiology of close relatives. Although, the only cultured Smithella sp., S. propionica is a propionate oxidizer (Liu et al., 1999), organisms with higher 16S rRNA sequence identity to MO302D8 have been implicated in the degradation of LCFA. A member of the Syntrophaceae related to Smithella spp., which shared 97% 16S rRNA sequence identity with MO302D8 from the current study, was isotopically enriched in a methanogenic sludge amended with 13C labelled palmitate (Fig. 5, AB290384; Hatamoto et al., 2007). Grabowski and colleagues (2005) also enriched (90–100% of the bacterial population) a member of the Syntrophaceae (clone FA-PB16; AY586399 in Fig. 5 and 94% 16S rRNA sequence identity with MO302D8) from a low temperature, shallow, oil field production water on LCFA (heptadecanoate and stearate).

There is thus precedence for organisms related to those enriched in the methanogenic crude oil degrading microcosms being capable of LCFA oxidation. Are these same organisms likely responsible for conversion of alkanes to LCFA, the key to alkane degradation? In our crude oil amended methanogenic microcosms or indeed any anaerobic hydrocarbon impacted subsurface environment LCFA are generated from oxidative alkane activation reactions. Such activation reactions in isolation are energetically unfavourable. For instance, using the approach and assumed reaction conditions of Dolfing and colleagues (2008b) we calculated that methanogenic hexadecane degradation yields −371 kJ mol−1(hexadecane). By contrast methanogenic degradation of hexadecanoate yields −385 kJ mol−1(hexadecanoate). The difference between these two values (i.e. +14 kJ mol−1) represents the free energy cost for conversion of the alkane to the corresponding LCFA. The process is therefore endergonic and this investment of energy can only be recovered if the same organism is also able to utilize the LCFA generated. The coupling of alkane conversion to a fatty acid and LCFA oxidation by Smithella is certainly consistent with the first report of the methanogenic degradation of a pure alkane (hexadecane, Zengler et al., 1999) where three species from the Syntrophaceae were very highly enriched (90% of the bacterial population). These species shared 99%, 93% and 93% 16S rRNA sequence identity with the organisms enriched here on added crude oil alkanes (e.g. MO302D8, Fig. 4A, Table 3) and their almost exclusive enrichment in the degradation of hexadecane suggests their activation of this substrate with subsequent LCFA degradation.

The role of Marinobacter in methanogenic oil degrading microcosms

Many Marinobacter spp. are aerobic marine heterotrophs, capable of growth on alkanes (e.g. Gauthier et al., 1992) and a number are known to degrade simple organic compounds with nitrate as an electron acceptor (Gauthier et al., 1992). Interestingly, Marinobacter spp. have been isolated from, and identified in, several anoxic hydrocarbon contaminated and subsurface environments (Huu et al., 1999; Orphan et al., 2000; Inagaki et al., 2003; Dunsmore et al., 2006; Gu et al., 2007, see Fig. 5). In these locations Marinobacter spp. are often considered non-indigenous aerobes or denitrifiers, although some deep subsurface isolates are considered indigenous (Batzke et al., 2007). A number of Marinobacter isolates, including some from subsurface marine sediments have been shown to be facultative anaerobes able to grow fermentatively (Köpke et al., 2005) and it was speculated that these organisms might be active in situ and participate in syntrophic interactions or use metal oxides as an electron sink (Köpke et al., 2005). This prompted us to evaluate the potential for anaerobic alkane degradation in the Marinobacter sp. that transiently increased in abundance in the methanogenic oil degrading microcosm clone library. The growth yield of Marinobacter (assuming that it was responsible for all alkane degradation) was only 0.0005 g(cell-C)/g(alkane-C) thus it is unlikely that Marinobacter played an important role in methanogenic alkane degradation. These data are consistent with the lack of reports of Marinobacter spp. oxidizing alkanes under methanogenic conditions; however, some Marinobacter may be capable of the anaerobic oxidation of minor components of the crude oil in partnership with methanogens. Indeed the overall yield of methane in the microcosms was greater than can be explained by conversion of all the alkanes to methane and detailed analysis of the residual oil shows that compounds other than alkanes are removed, although the concentrations of these compounds are substantially lower than the alkane concentration. This suggests that additional organisms may be responsible for conversion of different components of crude oil to methane.

Syntrophic partnerships in methanogenic crude oil degradation

In methanogenic environments organic carbon is degraded by syntrophic partnerships whereby participating organisms obtain energy by catalysing pathways that operate close to thermodynamic equilibrium (Dolfing et al., 2008b). For thermodynamic reasons bacterial syntrophy is sustainable only through the removal of the acetate, hydrogen or formate produced from fermentation of primary substrates and accordingly syntrophs rely on methanogens to consume these compounds (Dolfing et al., 2008b). MDS analysis of the microcosm communities showed a striking similarity between ordination patterns obtained with the archaeal and bacterial communities suggesting the establishment of such partnerships during methanogenic oil degradation.

In the oil amended microcosms, hydrogen-oxidizing Methanomicrobiales were enriched relative to facultative or obligate acetoclastic methanogens from the Methanosarcinales. Specifically, Methanomicrobiales sequences accounted for 82–94% of total methanogen growth and the calculated growth yield for this group [0.141–0.565 g(cell-C)/mol (CH4)] was broadly consistent but lower than values reported for pure cultures of methanogens belonging to the order Methanomicrobiales[0.64–1.47 g(cell-C)/mol (CH4)]. Members of the Methanomicrobiales lack cytochromes for energy conversion from hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis and, as such, have lower growth yields than members of the Methanosarcinales (Thauer et al., 2008).

Conventional wisdom suggests that the acetate generated from alkane oxidation should contribute two-thirds of methane production via acetoclastic methanogenesis (Table 2, Eq. 4). The predominance of hydrogen-oxidizing methanogens in subsurface environments (Head et al., 2010) may be explained by transport of additional hydrogen to petroleum reservoirs from external sources. These include hydrogen generated at high temperatures from organic matter maturation, serpentinization and radiolysis of water (Head et al., 2003). However, in our laboratory microcosms methanogens were only enriched in the presence of crude oil hydrocarbons and so there can be no external sources of hydrogen that would contribute to a predominance of hydrogenotrophic methanogens. An alternative explanation for hydrogenotroph enrichment in methangenic systems is SAO to H2 and CO2 (Table 2, Eq. 2, Zinder and Koch, 1984) coupled to methanogenesis from H2/CO2 (Table 2, Eq. 3). The possibility of SAO is supported in the present study by the formation of 13CO2 and a lower than predicted proportion of 13CH4 generated from 13CH3COO- (Fig. 7), which indicates that both acetoclastic methanogens and syntrophic acetate oxidizers were active in the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms.

The contribution of SAO to acetate removal was affected by the initial acetate concentration. This finding is consistent with the balance of acetoclastic and non-acetoclastic methanogenesis in long-term acetate-fed chemostats inoculated with anaerobic digester sludge (Shigematsu et al., 2004). In a reactor with low acetate concentrations (10 mg l−1, 0.169 mM) 62–90% of methane was produced via SAO whereas in a reactor with high acetate concentrations (250 mg l−1, 4.2 mM) 95–99% of methane was derived from acetoclastic methanogenesis. In the methanogenic oil degrading microcosms, measured acetate concentrations were below detection limits (< 10 µM) throughout the incubation period consistent with the high proportion of SAO activity inferred from hydrogenotrophic methanogen growth yields. Propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric or valeric acids were also below detection limits.

In the methanogenic crude oil degrading systems studied here, enrichment of known syntrophic acetate oxidizers (e.g. Clostridium and Thermoacetogenium spp. Schnürer et al., 1996; Hattori et al., 2000; Hattori, 2008) was not observed. However, isotope tracer measurements and analysis of enrichment cultures suggest that SAO is a widely distributed phenotype in other phyla (e.g. Hori et al., 2007; Schwarz et al., 2007). For instance, in a stable isotope probing study using 13C-acetate enrichments of Florida Everglade eutrophic wetland soils (where SAO linked to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis was the dominant methanogenic pathway) members of the Syntrophaceae were by far the most enriched bacteria (Chauhan and Ogram, 2006). On this basis the intriguing possibility exists that the Smithella sp. enriched in the oil degrading microcosms reported here and implicated in alkane oxidation via fatty acids was responsible for the complete degradation of alkanes to H2 and CO2 and ultimately to methane in syntrophic partnership with hydrogenotrophic methanogens.

Experimental procedures

Methanogenic hydrocarbon degrading microcosms

A description of the preparation of the methanogenic crude oil degrading microcosms is provided by Jones and colleagues (2008). Briefly, anaerobic microcosms were prepared with brackish carbonate buffered nutrient medium (100 ml) designed for the enrichment of sulfate reducing bacteria (Widdel and Bak, 1992) but without the addition of sulfate. Microcosms were inoculated with 10 g of sediment from the River Tyne, Newcastle, UK (54.96°N, 1.68°W). The methanogenic oil degradation experiments reported here comprised one experimental treatment and two control treatments [1. North Sea crude oil (300 mg); 2. North Sea crude oil (300 mg) plus 2-bromoethane sulfonate (BES; 10 mM final concentration) to inhibit methanogenesis; 3. No oil]. 18 replicate microcosms per treatment were prepared to allow for sacrificial sampling of triplicate microcosms at 22, 94, 176, 302, 450 and 686 days after inoculation. All microcosms were incubated in the dark in an anaerobic cabinet and routinely sampled for head space gas analysis (reported in Jones et al., 2008). Only microcosm samples from oil amended and unamended treatments were used for preparation of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries and qPCR analyses.

Microbial community analyses

Before sacrificial sampling, microcosms were shaken to ensure homogeneity and vacuum filtered (10 ml) onto polycarbonate membrane filters (0.2 µm pore size, 13 mm diameter; Nucleopore, Whatman, Leicestershire, UK). DNA was extracted from the filters using a FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (Q-BIOgene, California, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene fragments

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene fragments (∼ 1500 bp) were amplified by PCR using primers pA (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and pH reverse (5′-AAG GAG GTG ATC CAG CCG CA-3′) (Edwards et al., 1989). Archaeal 16S rRNA gene fragments (c. 1000 bp) were amplified with primers Arch46 (5′-YTA AGC CAT GCR AGT-3′) (Øvreås et al., 1997) and Arch1017 (5′-GGC CAT GCA CCW CCT CTC-3′) (Barns et al., 1994).

DGGE analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA genes was conducted on DNA from microcosms sacrificially sampled on day 22, 302 and 686. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene fragments were subjected to a second round of amplification using primer 3 (5′-CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG-3′) containing a 5′ GC clamp and primer 2 (5′-ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG-3′) (Muyzer et al., 1993). Archaeal 16S rRNA gene fragments were subjected to a second round of amplification using Arch344 (5′-GAC GGG GHG CAG CAG GCG CGA-3′) containing a 5′ GC clamp (Raskin et al., 1994) and Uni 522 (5′-GWA TTA CCG CGG CKG CTG-3′) (Amann et al., 1995). PCR products were purified using a Qiagen PCR clean up kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). DGGE analysis was conducted using a D-Gene denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) as previously described (Gray et al., 2002). Stained gels were viewed using a Fluor-S MultiImager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The Bionumerics software package (Applied Maths, Austin, Texas, USA) was used to produce normalized composite gels with reference to marker lanes (van Verseveld and Röling, 2004), and band identity and relative intensity were determined for individual community profiles. Band matching data from this analysis were used to calculate Dice similarity indices for pairwise combinations of DGGE profiles. Dice similarities were used to calculate average similarity values of DGGE profiles from replicate microcosms and between treatments (oil amended and unamended). The mean similarities of community profiles were compared using Student's t-test.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments

16S rRNA gene clone libraries were generated from the Tyne sediment used as an inoculum and from single replicate microcosms sampled from each treatment at 22, 302 and 686 days. Single representative samples were used on the basis of high similarity of DGGE profiles from replicate microcosms subject to the same treatments (c. 70–85% similarity; Table 1). PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments were cloned using a TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) using the pCR4-TOPO vector according to the manufacturer's instructions. Randomly selected clones were screened to determine insert size using PCR with the vector-specific primers pUCF. (5′-GTT TTC CCA GTC ACG AC-3′) and pUCR (5′-CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG AC-3′). Cloned inserts of the correct size in PCR reactions (5 µl) were purified using ExoSAP-IT (2 µl; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 3730xl DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) by the Institute for Research on Environment and Sustainability (IRES) sequencing service. (Newcastle University, UK). Sequences were compared to the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database at the European Bioinformatics Institute using Fasta3 (Pearson and Lipman, 1988) to identify the nearest neighbours. Initially, ∼ 500 nucleotides of sequence read was obtained from the primer pC (Edwards et al., 1989) for bacterial clones and the primer Arch 46 (Øvreås et al., 1997) for archaeal clones. Sequence quality was determined using Chromas 2.3 (Technelysium Pty; http://www.technelysium.com.au/chromas.html). Sequences were assigned to the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP release 10) taxonomic hierarchy using the online classifier tool (Wang et al., 2007). In addition, sequences were imported into the tree-building and database management software ARB, aligned and inserted into reference bacterial or archaeal trees in ARB using the quick parsimony insertion tool (Ludwig et al., 2004). The resultant trees were used to further refine taxonomic classifications. For the day 302 methanogenic oil degrading bacterial clone library phylogenetic reconstruction was refined by obtaining longer sequences (approximately 900 bp) for OTUs sharing less than 99% sequence identity. These longer sequences were obtained using additional primers T3 (5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGA-3′) or T7 (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′). Longer archaeal sequences (approximately 1000 bp) were obtained by using the primer Arch 1017 (Barns et al., 1994). Assembly of sequencing reads was performed in BioEdit (Hall, 1999) using the Contig Assembly Program (CAP; Huang, 1992). The presence of chimeric sequences within the data set were determined using Mallard (Ashelford et al., 2006) and/or Pintail (Ashelford et al., 2005) available from http://www.bioinformatics-toolkit.org. All 16S rRNA sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers (GU996298-GU997026). Neighbour joining distance trees for the longer sequences were constructed with reference sequences from GenBank selected to represent cultured and uncultured close relatives. Trees were constructed using the method of Saitou and Nei (Saitou and Nei, 1987) with the Jukes and Cantor correction for multiple substitutions at a single site (Jukes and Cantor, 1969). Bootstrap re-sampling was conducted with 100 replicates using the TREECON package (van De Peer and De Wachter, 1994).

Analysis of bacterial and archaeal community composition

Comparison of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries was based on rank abundance data for different OTUs identified. The rank abundance data were analysed by non-metric MDS (Clarke and Warwick, 2001) using Primer 6 community analysis software (PRIMER 6 for Windows; Version 6.1.5, PRIMER -E Ltd, UK). To determine which OTUs most influenced clustering of the data the contribution of each OTU was disaggregated using the SIMPER routine in PRIMER whereby species were ordered by their average contribution to the dissimilarities of the communities in the oil-treated and unamended microcosms. In addition, pairwise comparisons of clone libraries were made using the RDP Naive Bayesian rRNA Classifier Version 2.2, which provides estimates of the significance of differences in a given taxon between clone libraries.

Quantification of 16S rRNA genes in methanogenic oil degrading microcosms

The abundance and dynamics of specific bacterial and archaeal groups within the oil amended and unamended microcosms were determined by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR). The choice of primer pairs was based on the identity of OTUs, which were enriched or depleted in the oil amended microcosms (Table 4). For instance, a primer pair targeting a subgroup of the family Syntrophaceae within the Deltaproteobacteria (specifically, the genera Smithella and Syntrophus) was designed for this study along with a primer pair targeting a group of sequences from the genus Marinobacter (Gammaproteobacteria), which included Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus strain VT8 (AJ000726) and sequences identified in the oil amended microcosms. The design of these primer pairs was accomplished using the probe and PCR primer design software tool Primrose (Ashelford et al., 2002) incorporating full-length sequences for the target groups (i.e. 15 Smithella and Syntrophus sequences and 5 Marinobacter affiliated clone sequences). Candidate primers were then screened against a larger database constructed within PRIMROSE, which included (in addition to the RDP release 8 database) sequences from all bona fide Syntrophacaeae and Alteromonadales incertae sedis 7 present in RDP release 10. Candidate primer sequences were screened (see Table 4) for specificity using the RDP probe match analysis tool (Cole et al., 2007). In addition, the specificity of a primer pair targeting most bacteria, adapted from Maeda et al. (2003), was tested along with three primer pairs (Yu et al., 2005) targeting different archaeal groups (Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae). Quantification was performed on DNA extracts from all of the oil amended and unamended microcosms for all of the sacrificial sampling time points (22, 94, 176, 302, 450 and 686 days). Gene abundance in microcosm DNA samples was determined in relation to calibration standards from a 10-fold dilutions series (108–101 gene copies per µl) of target DNA sequence. The DNA targets were derived from clone sequences obtained from the oil degrading microcosms.

Table 4.

Quantitative PCR primers used in this study

| Target group | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Reference | Target group matches | Non-target matches |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | U1048f | GTG ITG CAI GGI IGT CGT CA | 323 | 60.5 | This studya | 93% | 0 sequences |

| U1371 | ACG TCI TCC ICI CCT TCC TC | ||||||

| Syntrophus + Smithella | Syn 827f | TTC ACT AGG TGT TGR GRG | 436 | 59.6 | This study | 88% & 77%b | 0 sequences |

| Syn 1263r | CTC TTT GTR CCR CCC ATT | ||||||

| Marinobacter | Mab 451f | TGG CTA ATA CCC ATG AGG | 122 | 60 | This study | 9%b,c | 2 sequencesc |

| Mab 573r | TAG GTG GTT TGG TAA GCG | ||||||

| Methanomicrobiales | MMB 282f | ATC GRT ACG GGT TGT GGG | 550 | 66 | Yu et al. (2005) | 90% | 0.4%b,d |

| MMB 832r | CAC CTA ACG CRC ATH GTT TAC | ||||||

| Methanosarcinaceae | Msc 380f | GAA ACC GYG ATA AGG GGA | 448 | 62 | Yu et al. (2005) | 45% | 0.7%b,e |

| Msc 828r | TAG CGA RCA TCG TTT ACG | ||||||

| Methanosaetaceae | Mst 702f | TAA TCC TYG ARG GAC CAC CA | 126 | 62 | Yu et al. (2005) | 71% | 0.2%b,e |

| Mst 826r | CCT ACG GCA CCR ACM AC |

Adapted from Maeda and colleagues (2003).

Primer pair targets all target group sequences found in the day 302 and 686 clone libraries but no non-target sequences.

The Marinobacter primer pair targeted only a small subgroup (9.2%) of the Marinobacter genus including Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus (T); VT8; AJ000726. The forward and reverse primers shared two non-target sequences namely, the uncultured bacterium; F20; AY375115 currently assigned by RDP to the alphaproteobacterial genus Erythrobacter and an unclassified proteobacterium ctg_NISA064; DQ396144.

Indicates only non-target matches within the class Methanosarcinales.

Indicates only non-target matches within in the class Methanomicrobiales. The Methanosarcinaceae primers targeted approximately 12% of Methanosaetaceae and the Methanosaetaceae primers targeted approximately 0.3% of the Methanosarcinaceae.

I, inosine.

qPCR reactions comprised iQ Supermix (10 µl), PCR primers (1 µl of 10 pmoles µl−1 each), sterile water (6 µl), SYBR Green (0.2 µl per reaction of 100 × diluted from 10 000 × concentrate) and DNA template (3 µl) made up to a final volume of 20 µl. qPCR reactions were carried out using a Bio-Rad iQ5 thermocycler and included an initial denaturation (7 min at 95°C), followed by 40 cycles (for the bacterial primer pair) or 55 cycles (for all other primer pairs) of [30 s at 95°C, 30 s at the specific primer annealing temp (see Table 3) and 40 s at 72°C]. Optimal annealing temperatures were determined for the Syntrophaceae and Marinobacter primer pairs by performing a temperature gradient PCR with annealing temperatures in the range of 57°C to 70°C. Target 16S rRNA gene templates were PCR-amplified from bacterial and archaeal clones obtained and sequenced in this study. The target clone sequences were amplified using primers pUCf and pUCr as described above. The DNA concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. To improve PCR efficiencies standard dilution series containing known concentrations of target 16S rRNA gene fragments were prepared by mixing the highest concentration standard (109 genes µl−1) with a complex mixture of PCR-amplified bacterial 16S rRNA genes obtained from River Tyne sediment DNA. In the presence of this background matrix all the target standard dilution series gave high correlation coefficients (above 0.99), similar calibration slopes (between −3.0 and −3.9) and qPCR efficiencies (> 80%). Without adding this background matrix the efficiency of some of the qPCR assays determined with pure standard was consistently low. The background contribution of Syntrophus/Smithella and Marinobacter genes present in River Tyne sediment derived 16S rRNA matrix used to prepare the standard dilution series was estimated at less than 1% of the respective added amounts of standard target DNA.

Microcosm cell size estimates

Microcosm samples (0.5 ml) were fixed by addition of 0.5 ml molecular biology grade filtered absolute ethanol (0.2 micron filtered) and stored at −20°C. SYBR-gold nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) (50 µl diluted 100-fold) was added to fixed samples (1 ml) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation cells were vacuum filtered onto polycarbonate membrane filters (Isopore, 13 mm, 0.2 µm pore size, Millipore, Watford, UK), washed in 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (130 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4), and covered with a cover slip on a standard microscope slide. Cells were viewed under oil immersion (100 ×) on an epifluorescence microscope (BX40, Olympus, London, UK), under a blue light filter. Images were captured using a digital camera (Olympus E-400, Olympus, UK) and cell size estimates were obtained using the Cell C image analysis software (Selinummi et al., 2005, https://sites.google.com/site/cellcsoftware/).

Growth characteristics derived from qPCR data

Specific growth rates µ were calculated from qPCR derived cell abundance using ln NT − ln N0 = µ t where N0 is the number of cells at the start of the exponential growth phase, NT is the number of cells at time T, and t is the time elapsed in days. Doubling times were calculated as ln2/µ). Growth yields (g cell carbon/g carbon from alkane) were calculated using alkane removal data from Jones and colleagues (2008) and biomass carbon. Biomass carbon was estimated from qPCR derived gene abundances as follows. Cell numbers were derived from qPCR data by dividing 16S rRNA gene abundances by the rRNA operon copy number for the different taxa analysed (Smithella/Syntrophus 1 copy, Marinobacter 3 copies, Methanomicrobiales 1–4 copies, Methanosarcinaceae 3 copies and Methanosaetaceae 3 copies) obtained from the ribosomal RNA operon copy number database (rrnDB) (Lee et al., 2009). Cell numbers were converted to cell volumes using the average measured cell volume (0.024 µm3) determined from the hydrocarbon degrading microcosm samples. Finally, cell volumes were converted to carbon content based on an assumption of 310 fg C µm−3 (Fry, 1990).

Measurement of SAO

Syntrophic acetate oxidation in samples from the methanogenic crude oil degrading microcosms was measured in glass serum bottles (14 ml, Aldrich, UK) sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and aluminium crimps (Aldrich, UK). Replicate incubations were prepared with anaerobic carbonate buffered nutrient medium (5 ml; Widdel and Bak, 1992) and different amounts of 2-13C sodium acetate, 99 Atom%, Sigma Aldrich UK). The final concentration of added labelled acetate in each treatment was 10, 1, 0.1 or 0 mM). The serum bottles were inoculated with 1 ml from a methanogenic oil degrading microcosm, which had been incubated for 450 days. All microcosms were incubated on a shaker (100 r.p.m.) at 22°C. Headspace gases were periodically analysed for 13C- and 12C-labelled CH4 and CO2 (Gray et al., 2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the BACCHUS2 biodegradation consortium for financial support, discussions and permission to publish. The BACCHUS2 members are Agip ENI, BP/Amoco, Chevron Texaco, Conoco Phillips, StatoilHydro, Petrobras, Saudi Aramco, Shell, Total and Woodside. Financial support was also provided by the Natural Environment Research Council (Grant NE/E01657X/1 to IMH, NDG and DMJ and a Federation of European Microbiological Societies Research Fellowship (FEMS 2007-1) to CRJH).

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1. Bacterial and archaeal DGGE profiles from replicate oil amended and unamended microcosms sacrificed on day 302.

Fig. S2. Phylogenetic affiliation of non-Proteobacterial 16S rRNA sequences recovered from methanogenic microcosms. Clone frequency in bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from the inoculum and initial day 22 samples (bottom panel, total number of clones = 71) and in samples from methanogenic oil degrading microcosms (top panel, number of ‘day 302’ clones = 61, number of ‘day 686’ clones = 87) and control microcosms with no added oil (middle panel, number of ‘day 302’ clones = 62, number of ‘day 686’ clones = 87). Data from clone libraries from day 302 (filled bars) and day 686 (open bars) are shown. Clones were grouped into categories based on their genus, order, class or phylum level affiliation after phylogenetic analysis with the ARB software package using an RDP guide tree. The affiliation of individual sequences was cross-checked using the RDP taxonomical hierarchy with the Naive Bayesian rRNA Classifier Version 2.0, July 2007. DGGE profiles from replicate microcosms were highly reproducible and clone libraries were prepared for one representative replicate microcosm for each time point.

Fig. S3. Phylogenetic distance trees based on comparative analysis of non-Proteobacterial partial 16S rRNA sequences recovered from a representative oil amended microcosm on day 302. Sequences recovered in this study (grey text) are prefixed by MO302. Related organisms identified in petroleum systems or those directly implicated in oil degradation are in bold. GenBank accession numbers for all database sequences are provided in parenthesis. Tree rooted with respect to the Marinobacter excellens KMM 3809T 16S rRNA sequence (AY180101). The scale bar denotes 10% sequence divergence and the values at the nodes indicate the percentage of bootstrap trees that contained the cluster to the right of the node. Bootstrap values less than 50 are not shown.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Allen JP, Atekwana EA, Atekwana EA, Duris JW, Werkema DD, Rossbach S. The microbial community structure in petroleum-contaminated sediments corresponds to geophysical signatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2860–2870. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01752-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RT, Lovley DR. Biogeochemistry – hexadecane decay by methanogenesis. Nature. 2000;404:722–723. doi: 10.1038/35008145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashelford KE, Weightman AJ, Fry JC. PRIMROSE: a computer program for generating and estimating the phylogenetic range of 16S rRNA oligonucleotide probes and primers in conjunction with the RDP-II database. Nucl Acids Res. 2002;30:3481–3489. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashelford KE, Chuzhanova NA, Fry JC, Jones AJ, Weightman AJ. At least one in twenty 16S rRNA sequence records currently held in public repositories estimated to contain substantial anomalies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7724–7736. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7724-7736.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashelford KE, Chuzhanova NA, Fry JC, Jones AJ, Weightman AJ. New Screening software shows that most recent large 16S rRNA gene clone libraries contain chimeras. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5734–5741. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00556-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auburger G, Winter J. Isolation and physiological characterization of Syntrophus buswellii strain GA from a syntrophic benzoate-degrading, strictly anaerobic coculture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans C, Madsen EL. Diversity of 16S rDNA and naphthalene dioxygenase genes from coal-tar-waste-contaminated aquifer waters. Microb Ecol. 2002;44:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s00248-002-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barns S, Fundyga RE, Jeffries MW, Pace NR. Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batzke A, Engelen B, Sass H, Cypionka H. Phylogenetic and physiological diversity of cultured deep-biosphere bacteria from equatorial Pacific ocean and Peru margin sediments. Geomicrobiol J. 2007;24:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Brofft JE, McArthur JV, Shimkets LJ. Recovery of novel bacterial diversity from a forested wetland impacted by reject coal. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:764–769. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Ogram A. Phylogeny of acetate-utilizing microorganisms in soils along a nutrient gradient in the Florida Everglades. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6837–6840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01030-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR, Warwick RM. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation. 2nd edn. Plymouth, UK: PRIMER-E; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, et al. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:D169–D172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl889. (Database issue): doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van De Peer Y, De Wachter R. Treecon for windows – a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the microsoft windows environment. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:569–570. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dojka MA, Hugenholtz P, Haack SK, Pace NR. Microbial diversity in a hydrocarbon- and chlorinated-solvent-contaminated aquifer undergoing intrinsic bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3869–3877. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3869-3877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolfing J, Jiang B, Henstra AM, Stams AJM, Plugge CM. Syntrophic growth on formate: a new microbial niche in anoxic environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008a;74:6126–6131. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01428-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolfing J, Larter SR, Head IM. Thermodynamic constraints on methanogenic crude oil biodegradation. ISME J. 2008b;2:442–452. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore B, Youldon J, Thrasher DR, Vance I. Effects of nitrate treatment on a mixed species, oil field microbial biofilm. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:454–462. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E, Grbić-Galić D. Anaerobic degradation of toluene and o-xylene by a methanogenic consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:313–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.313-322.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards U, Rogall T, Blöcker H, Emde M, Böttger EC. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterisation of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucl Acids Res. 1989;17:7843–7853. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry JC. Direct methods and biomass estimation. In: Grigorova R, Norris JR, editors. Methods in Microbiology, Volume 22, Techniques in Microbial Ecology. London, UK: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 41–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier MJ, Lafay B, Christen R, Fernandez L, Acquaviva M, Bonin P, Bertrand JC. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new extremely halotolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:568–576. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieg LM, Duncan KE, Suflita JM. Bioenergy production via microbial conversion of residual oil to natural gas. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:3022–3029. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00119-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieg LM, Davidova IA, Duncan KE, Suflita JM. Methanogenesis, sulfate reduction and crude oil biodegradation in hot Alaskan oilfields. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:3074–3086. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski A, Blanchet D, Jeanthon C. Characterization of long-chain fatty-acid-degrading syntrophic associations from a biodegraded oil reservoir. Res Microbiol. 2005;156:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ND, Miskin IP, Kornilova O, Curtis TP, Head IM. Occurrence and activity of Archaea in aerated activated sludge wastewater treatment plants. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:158–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ND, Matthews JNS, Head IM. A stable isotope titration method to determine the contribution of acetate disproportionation and carbon dioxide reduction to methanogenesis. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;65:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ND, Sherry A, Larter SR, Erdmann M, Leyris J, Liengen T, et al. Biogenic methane production in formation waters from a large gas field in the North Sea. Extremophiles. 2009;13:511–519. doi: 10.1007/s00792-009-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ND, Sherry A, Hubert C, Dolfing J, Head IM. Methanogenic degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in subsurface environments: remediation, heavy oil formation, and energy recovery. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2010;72:137–161. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)72005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Cai H, Yu S-L, Qu R, Yin B, Guo Y-F, et al. Marinobacter gudaonensis sp. nov., isolated from an oil-polluted saline soil in a Chinese oilfield. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:250–254. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamoto M, Imachi H, Yashiro Y, Ohashi A, Harada H. Diversity of anaerobic microorganisms involved in long-chain fatty acid degradation in methanogenic sludges as revealed by RNA-based stable isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4119–4127. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00362-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori S. Syntrophic acetate-oxidizing microbes in methangenic environments. Microbes Environ. 2008;23:118–127. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.23.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori S, Kamagata Y, Hanada S, Shoun H. Thermacetogenium phaeum gen. nov., sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1601–1609. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head IM, Jones DM, Larter SR. Biological activity in the deep subsurface and the origin of heavy oil. Nature. 2003;426:344–352. doi: 10.1038/nature02134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head IM, Larter SR, Gray ND, Sherry A, Adams JJ, Aitken CM, et al. Hydrocarbon Degradation in Petroleum Reservoirs. In: Timmis KN, McGenity T, van der Meer JR, de Lorenzo V, editors. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. pp. 3097–3109. pp. 4699 p. Voume 4. Part 6. Chapter 54. [Google Scholar]

- Hippensteel D. Perspectives on environmental risk management at hydrocarbon contaminated Sites. Environ Geosci. 1997;4:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Noll M, Igarashi Y, Friedrich MW, Conrad R. Identification of acetate-assimilating microorganisms under methanogenic conditions in anoxic rice field soil by comparative stable isotope probing of RNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:101–109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01676-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. A contig assembly program based on sensitive detection of fragment overlaps. Genomics. 1992;14:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huu NB, Denner EBM, Ha DTC, Wanner G, Stan-Lotter H. Marinobacter aquaeolei sp. nov., a halophilic bacterium isolated from a Vietnamese oil producing well. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:367–375. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki F, Takai K, Hirayama H, Yamato Y, Nealson KH, Horikoshi K. Distribution and phylogenetic diversity of the subsurface microbial community in a Japanese epithermal gold mine. Extremophiles. 2003;7:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s00792-003-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BE, Bhupathiraju VK, Tanner RS, Woese CR, McInerney MJ. Syntrophus aciditrophicus sp. nov., a new anaerobic bacterium that degrades fatty acids and benzoate in syntrophic association with hydrogen-using microorganisms. Arch Microbiol. 1999;171:107–114. doi: 10.1007/s002030050685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DM, Head IM, Gray ND, Adams JJ, Rowan A, Aitken C, et al. Crude-oil biodegradation via methanogenesis in subsurface petroleum reservoirs. Nature. 2008;451:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature06484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro HN, editor. Mammalian Protein Metabolism. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai Y, Takahata Y, Hoaki T, Watanabe K. Physiological and molecular characterization of a microbial community established in unsaturated, petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:806–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith LH, Telliard WA. Priority pollutants I – a perspective view. Environ Sci Technol. 1979;13:416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Köpke B, Wilms R, Engelen B, Cypionka H, Sass H. Microbial diversity in coastal subsurface sediments: a cultivation approach using various electron acceptors and substrate gradients. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7819–7830. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7819-7830.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ZM, Bussema C, 3rd, Schmidt TM. rrnDB: documenting the number of rRNA and tRNA genes in bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn689. (database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Balkwill DL, Aldrich HC, Drake GR, Boone DR. Characterization of the anaerobic propionate degrading syntrophs Smithella propionica gen. nov., sp. nov. and Syntrophobacter wolinii. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:545–556. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, Kumar Y, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acid Res. 2004;32:1363–1371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Fujimoto C, Haruki Y, Maeda T, Kokeguchi S, Petelin M, et al. Quantitative real-time PCR using TaqMan and SYBR green for Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, tetQ gene and total bacteria. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:81–86. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbadinga SM, Wang L-Y, Zhou L, Liu J-F, Gu J-D, Mu B-Z. Microbial communities involved in anaerobic degradation of alkanes. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2011;65:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G, De Waal EC, Utterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis analysis of Polymerase Chain Reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphan VJ, Taylor LT, Hafenbradl D, Delong E. Culture-dependent and Culture-independent characterization of microbial assemblages associated with high-temperature petroleum reservoirs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:700–711. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.2.700-711.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]