Abstract

The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) macaque model resembles human HIV-AIDS and associated brain dysfunction. Altered expression of synaptic markers and transmitters in neuro-AIDS has been reported, but limited data exist for the cholinergic system and lipid mediators such as prostaglandins. Here, we analyzed cholinergic basal forebrain neurons with their telencephalic projections and the rate-limiting enzymes for prostaglandin synthesis, cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 (COX1 and 2) in brains of SIV-infected macaques with and without encephalitis and antiretroviral therapy, and uninfected controls. COX1 but not COX2 was co-expressed with markers of cholinergic phenotype, i.e. choline acetyltransferase and vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), in basal forebrain neurons of monkey, as well as human samples. COX1 was decreased in basal forebrain neurons in macaques with AIDS vs. uninfected and asymptomatic SIV-infected macaques. VAChT-positive fiber density was reduced in frontal, parietal and hippocampal-entorhinal cortex. Although brain SIV burden and associated COX1- and COX2-positive mononuclear and endothelial inflammatory reactions were mostly reversed in AIDS-diseased macaques that received 6-chloro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine treatment, decreased VAChT-positive terminal density and reduced cholinergic COX1 expression were not. Thus, COX1 expression is a feature of primate cholinergic basal forebrain neurons; it may be functionally important and a critical biomarker of cholinergic dysregulation accompanying lentiviral encephalopathy. These results imply that insufficiently prompt initiation of antiretroviral therapy in lentiviral infection may lead to neurostructurally unremarkable but neurochemically prominent, irreversible brain damage.

Keywords: AIDS, Antiretroviral treatment, Cholinergic, Dementia, Encephalitis, Prostaglandins

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neurocognitive disorders accompany HIV infection even when it is controlled with chronic antiretroviral therapy (1, 2). Compromised brain function can occur in HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection even without overt brain structural damage (3, 4), suggesting that neurochemical alterations may underlie lentivirus-associated cognitive deficits. Supporting this hypothesis, altered cerebral expression of synaptic markers and neurotransmitters in HIV/SIV disease has been reported (5–8).

The cholinergic telencephalic system has not been carefully examined in lentiviral encephalopathy. The mammalian cholinergic basal forebrain system is comprised of several well-defined cell groups projecting to the cortex and hippocampus (9, 10), which are involved in cognition and memory (11). How the cholinergic basal forebrain system regulates cortical and hippocampal function, and is dysregulated in dementing diseases, has been extensively investigated in rodent and primate animal models (12–15). Altered cholinergic function may result from differential expression of components of the cholinergic gene locus, i.e. choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) (16–26). Neurotrophin and transmitter receptors, including those for nerve growth factor (13, 27, 28) and galanin (29), co-expressed with acetylcholine in these neurons can also modulate cholinergic function, survival and synaptic strength. Other transmitter substances present in cholinergic neurons and modulating their function may remain to be discovered.

Here, we examined the cholinergic telencephalic projection system in the rhesus macaque primate model of neuro-AIDS. SIV-infected monkeys exhibit signs of motor and cognitive impairment reminiscent of cognitive dysfunction in humans with HIV infection and associated dementia (3). We observed that the rate-limiting enzyme for prostaglandin synthesis, cyclooxygenase isotype-1 (COX1), is selectively expressed in cholinergic neurons of monkey basal forebrain complex (BFC). COX1 expression in the somata and the synaptic density of VAChT-positive projections of these neurons in cortex and hippocampus were decreased in SIV disease. These effects were not reversed in monkeys that had received brain-permeable antiretroviral treatment, which dramatically reduces viral load and productive inflammation in the SIV-infected CNS (30–32). Our findings have implications for understanding how neuroanatomically silent or subtle perturbations accompanying lentiviral infection and/or chronic inflammation may lead to cognitive impairment through effects on telencephalic cholinergic transmission and co-transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus Stock and Inoculation Procedures

Healthy rhesus macaques, 22 to 23 months of age, which were screened and found to be free of SIV, simian retrovirus type D and B virus, were used for the study (30). Experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Bioqual, Inc., an NIH-approved and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited research facility, and were carried out under the ethical guidelines in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The macaques were inoculated i.v. with 10 rhesus infectious doses of cell-free, human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-grown SIV strain δB670. Following inoculation, the animals were monitored and examined for clinical evidence of disease. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were periodically obtained from the animals (30). At the time of death, 7 macaques exhibited clinical signs of AIDS and 5 did not. Four age-matched non-infected macaques were used as controls.

Antiretroviral Treatment

Additionally, 6 SIV-infected macaques that had been treated with 6-chloro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine (6-Cl-ddG) subcutaneously when their viral load was >100,000 virions/mL in plasma and >100 virions/mL in CSF in more than 2 consecutive examinations were studied (30). Only 1 monkey received 6-Cl-ddG (200 mg/kg/day) for 3 weeks; the other 5 monkeys received 10 mg/kg/day 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI) for 3 weeks for clinical stabilization and then 75 mg/kg/day of 6-Cl-ddG for 6 weeks. The vehicle for ddI administration was phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); for 6-Cl-ddG administration the vehicle was 70% propylene glycol/30% PBS.

Brain Tissue Preparation

At death, anesthetized monkeys were perfused transcardially with PBS and formalin/PBS. Tissue specimens were obtained during necropsy and immersion fixed overnight. Tissue blocks were postfixed in Bouin-Hollande solution and processed for paraffin embedding (30). Human brain tissue blocks were obtained from individuals without neuropsychiatric disease (Department of Anatomy, Philipps University, Marburg), snap-frozen in −40°C-cooled isopentane or immersion-fixed in Bouin-Hollande solution, and processed for paraffin embedding.

Single and Double Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry (IHC), 7-μm-thick brain tissue sections were deparaffinized and cooked in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 92° to 95°C in a pressure cooker for 15 minutes, permeablized, blocked for nonspecific binding sites and incubated with primary antibodies. Immunolabeling was performed using biotinylated secondary antibodies from donkey (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany; 1/200), standard avidin-biotin-peroxidase technique (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Boehringer, Germany; 1/500), and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) with ammonium nickel sulfate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), resulting in dark blue/black staining, or using fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dianova; 1/200), as previously described (30). For visualization of 2 different antigens in the same tissue section, double immunofluorescence staining was done. Otherwise, immunostaining was carried out on adjacent sections. The primary antibodies used are listed in Table 1. Recombinant COX1 and COX2 peptides (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used for preabsorption experiments of antibodies against COX1 and COX2 on monkey and human brain tissue sections (32). Immunostained sections were analyzed and documented with Olympus AX70 or with Olympus Fluoview confocal laser scanning microscopes (Olympus Optical, Hamburg, Germany).

Table 1.

Antibodies

| Antigen | Epitope | Species/Type | Dilution | Catalog no | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human COX1 | C-terminal 15–25 aa | Goat polyclonal | 1:8000,1:600 (f) | sc-1752 | SCB |

| Human COX2 | C-terminal 15–25 aa | Goat polyclonal | 1:5000 | sc-1745 | SCB |

| Human VAChT | C-terminal 12 aa | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:6000,1:300 (f) | 80153 | PP |

| Monkey VAChT | 27 aa | Goat polyclonal | 1:2000 | 1624 | PP |

| Human ChAT | n.d. | Mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | 1372432 | BM |

| SIVmac251 gp120 | 311–340 aa | mouse monoclonal | 1:2000 | 2318 | NIHARP |

Abbreviations: aa, amino acids; BM, Boehringer(Mannheim, Germany); ChAT, choline acetyltransferase; COX1/2, cyclooxygenase isotype-1/2; f, dilution for immunofluorescence; gp120, envelope glycoprotein 120; n.d., not determined; no, number; NIHARP, NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program (Germantown, MD);PP, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA); SCB, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); SIVmac251, simian immunodeficiency virus strain mac251; VAChT, vesicular acetylcholine transporter.

In Situ hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) was performed on human brain tissue cryosections (14 μm) using [35S]-UTP labelled riboprobes complementary to human COX1 (U63846; 912 bp subcloned in pGEM T-easy), human COX2 (M90100; 895 bp subcloned in pBSK+) and human VAChT (U10554; 780 bp subcloned in pcDNAI), as previously described (30). Radioactive ISH signals were revealed by autoradiography after 2 to 3 weeks of exposure on slides developed in NTB-2 emulsion (Eastman Kodak, NY), fixed, counterstained lightly with hematoxylin and eosin, and analyzed with the Olympus AX70 microscope.

Virus Detection in Tissues and Fluids

SIV was analyzed by IHC and ISH on brain and lymphoid tissue sections, and by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on plasma and CSF samples. IHC was carried out against SIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 (30–32). ISH was performed using probes generated by incorporation of [35S] into SIV riboprobes by in vitro transcription of sequences from SIV strain mac239 (AY588945) cloned in a pTRIKAN19 vector, or into DNA probes by random priming using sequences of cloned DNA of SIV strain macBK28 (M19499), as previously described (30, 31). The DNA templates were a 496-bp-long KpnI fragment from the pol gene of SIV strain mac239 or a 7334-bp-long BamHI fragment from SIV strain macBK28. In some experiments, ISH was performed with 30-bp-long [35S]-3′-end-labeled oligonucleotides complementary to proviral sequences at the exon/intron junction at the 5′-end of unspliced RNA from SIV strain smH4 (X14307) (30, 31). ISH signals were detected by autoradiography after 3 to 6 days of exposure and development in NTB-2 emulsion. After counterstaining with Cresyl violet, the cells with more silver grains above background (defined as signal with the sense control probes) were counted. Levels of SIV core antigen p26 in plasma were quantitated using of an antigen capture ELISA (Coulter Immunology, Miami, FL). For RT-PCR, RNA was extracted from pelleted SIV obtained by ultracentrifugation of plasma or CSF, reverse transcribed with murine MLV reverse transcriptase and amplified by PCR using [32P]-end-labelled primer (5′-GGA TGA CAT CTT AAT AGC TAG TGA-3′) and non-labelled primer (5′-ATT TTG TCT TCT TGG TGA ATT TTA-3′) for the pol gene. Radiolabeled PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis and the signals on X-ray film were computer-assisted analyzed (Quantity One; PDI, Huntington Station, NY). Serially diluted preparations of an HIV1-LAI viral stock the particle number per mL of which had been determined by electron microscopy was used to construct a standard curve.

Quantitative Image Analysis

To achieve an unbiased analysis of immunohistochemical staining, the monkey identities of sections were blinded for the investigator. For quantification of the immunostaining intensity of COX1- and VAChT-positive neurons, the relative optical densities (RODs) were determined on COX1- and VAChT-immunostained sections. Sections were analyzed under bright-field conditions using a digital camera (Spot RT Slider; Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI) and computer-assisted image analysis (ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, MD). For each monkey, 3 to 7 interval sections per anatomical area were analyzed. At least 50 random neurons with a visible nucleus were examined per anatomical area on a section. The immunostained area of each perikaryon was outlined for ROD integration and corrected by determination of background ROD on non-immunostained areas of the section. Data were expressed as mean ROD ± SD. For quantification of VAChT-positive fiber density, the numbers of pixels were determined on VAChT-immunostained sections. Sections were analyzed under bright-field conditions using a digital camera (Spot RT Slider) and using computer-assisted image analysis (MCID M4 image analysis system; Imaging Research Inc., St. Catherines, ONT, Canada). At least 10 randomly chosen planes were analyzed per section. For each monkey, 3 to 5 interval sections per anatomical area were analyzed. Data are expressed as mean pixels ± SD. All IHC parameters and procedures relevant for COX1- or VAChT-staining quantifications (e.g. antibody concentrations, reaction and washing times, temperatures, illumination and image analysis settings) were kept constant.

Statistics

ANOVA and the post-hoc Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test were used to evaluate statistical differences between the groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

COX1 but not COX2 Is Expressed in Cholinergic Neurons of the Basal Forebrain in Rhesus Macaques and Humans

We recently screened several antibodies against COX1 and COX2 for immunohistochemical specificity on rhesus monkey brain tissue sections (32). Only those antibodies giving staining in neocortical tissue sections, in which neurons are known to express COX1 or COX2 throughout different species (33–36), and which were preabsorbed exclusively with their cognate immunogen peptides, were assumed to be specific and used for the present study, as previously described (32). Whereas COX2 was not expressed in non-neuronal cells, COX1 was found in microglia and endothelial cells in normal rhesus monkey brain (32).

In addition to neocortical neurons, neurons in areas of the so-called BFC, which is composed of the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM), the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca (vdbB, hdbB) and the medial septum (10), expressed COX1 in the normal rhesus macaque. These COX1-positive neurons were cholinergic, as shown by double IHC or adjacent staining with specific markers of the cholinergic phenotype, ChAT and VAChT (Fig. 1A-J). COX1 was localized in neuronal cell bodies and proximal processes of cholinergic neurons but not in cholinergic fibers and terminals identified by staining for VAChT (Fig. 1G-J). No COX2 expression was found in these neurons (Fig. 2A-C), suggesting that the vast majority of cholinergic neurons of the BFC in rhesus monkey are able to synthesize prostaglandins exclusively through COX1, and not COX2.

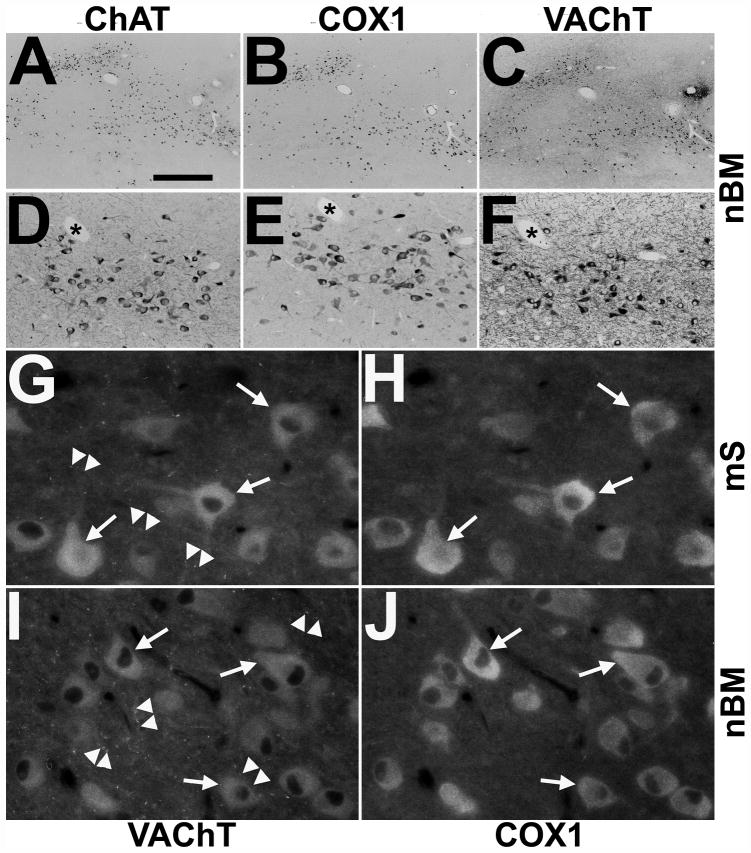

Figure 1.

Immunodetection of cyclooxygenases 1 (COX1) in cholinergic neurons of the rhesus monkey basal forebrain. (A–F) Representative single immunohistochemistry of adjacent sections alternately stained for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (A, D), COX1 (B, E) and vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) (C, F) reveal COX1 in the majority of cholinergic neurons of the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM) of a control rhesus monkey as shown in low- (A–C) and medium-power (D–F) images. Asterisks in (D–F) mark cross-sectional profiles of the same blood vessel at different section planes. (G–J) High-power double immunofluorescence demonstrates colocalization of COX1 (H, J) with VAChT (G, I) in somata and proximal processes of cholinergic neurons (arrows) but not in VAChT-positive varicose fibers and synapses (arrowheads) in the medial septum (mS; G, H) and the nbM (I, J) of a control monkey. Scale bars: A–C, 1000 μm; D–F, 200 μm; G–J, 40 μm.

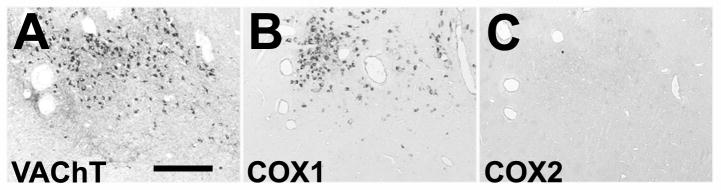

Figure 2.

Lack of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) immunoreactivity in neurons of the rhesus monkey basal forebrain. (A–C) Representative low-power images of alternate staining of interval sections reveal the presence of vesicular acetylcholine transporter VAChT (A) and COX1 (B) in neurons, but total absence of COX2 (C) in the nucleus basalis of Meynert of a control rhesus monkey. Bar = 30 μm.

Some striatal cholinergic neurons are COX1-positive; cholinergic neurons of the ventral part of the dorsal nucleus of vagus nerve are COX2-positive. Other cholinergic neurons e.g. brain stem nuclei, motoneurons of spinal ventral horn or preganglionic autonomic neurons of spinal lateral horn, were negative for both COX1 and COX2 (data not shown).

COX1 was co-immunolocalized with ChAT and VAChT in cholinergic neurons of the human BFC (Fig. 3A-C). Expression of COX1 in these cholinergic neurons was also observed by ISH (Fig. 3D, E). Endothelial and microglial cells additionally expressed COX1 mRNA in the human brain (Fig. 3F, G). COX2 protein and mRNA were not detected in human cholinergic BFC neurons.

Figure 3.

Expression of cyclooxygenase 1 (COX1) protein and COX1 mRNA in cholinergic neurons of the human basal forebrain and specificity of COX1 riboprobe. (A–C) Adjacent sections alternately immunostained (IHC) for choline acetyltransferase ChAT (A), COX1 (B) and vesicular acetylcholine transporter VAChT (C) demonstrate COX1 in cholinergic neurons (arrows) of the human nucleus basalis of Meynert. Notice that cholinergic varicose fibers are only stained for VAChT (arrowheads; C). (D, E) Representative low-power darkfield images of in situ hybridization (ISH) with [35S]-labeled riboprobes on interval sections from human nucleus basalis of Meynert reveal occurrence of COX1 mRNA (silver grains; E) in VAChT mRNA-expressing neurons (silver grains; D). (F, G) Bright-field images of riboprobe in antisense orientation against COX1 mRNA is specific and detects COX1 mRNA in endothelial cells and microglia in a human brain tissue section (double arrowheads; COX1 as; F) ISH with [35S]-labeled riboprobe in sense orientation against COX1 mRNA demonstrates no any signals except background (COX1 s, G). Asterisks show the same blood vessel in weakly hematoxylin and eosin–stained adjacent sections. Bars: A–C, 100 μm; D, E, 200 μm; F, G, 150 μm.

COX1 Is Downregulated in BFC and Frontal Cortex Neurons in SIV Infection and Is Differentially Affected in 6-Cl-ddG-Treated Monkeys

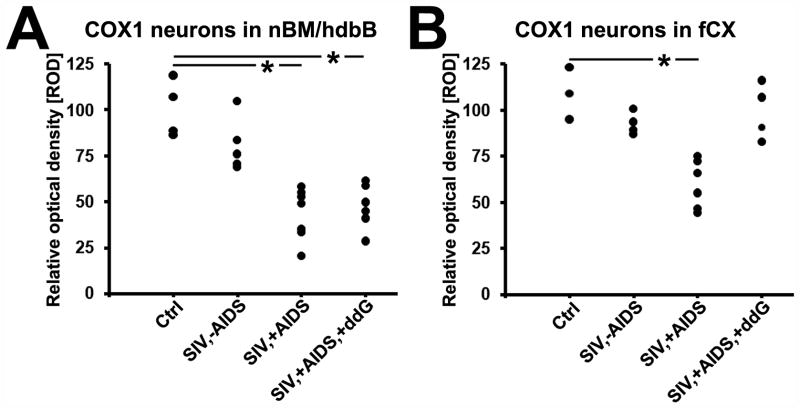

nbM and ventrally contiguous hdbB subnuclei of the BFC are known to project their cholinergic fibers to the neocortex (9). COX1 expression was not altered in early stage (SIV,−AIDS), but was reduced in the late stage of SIV infection (SIV,+AIDS) as compared to non-infected control monkeys (Fig. 4A-C). Infection and clinical status as well as SIV levels in brain, lymphoid organs, plasma and CSF of each monkey are shown in Table 2. Cerebral mononuclear and endothelial inflammatory reactions (as identified by IHC for COX1 and COX2, and described previously [32]) are presented for each monkey in Table 3. Because stereological counting of COX1-positive neurons could not be performed in the available brain tissue blocks, measurement of ROD of neuronal COX1 immunostaining, representing COX1 protein content of individual neurons, was performed for each monkey. Mean ROD of COX1 immunostaining of cholinergic neurons of the nbM and hdbB in the control group (100.3 ± 15.5) was not different compared to SIV,−AIDS (80.9 ± 14.6; p > 0.05), but the ROD was significantly reduced in the SIV,+AIDS group (43.5 ± 14.0; p < 0.05) (Fig. 5A).

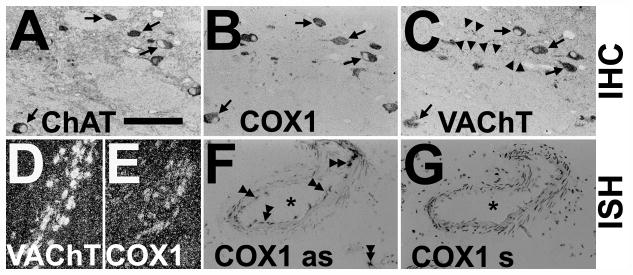

Figure 4.

Changes in neuronal cyclooxygenase 1 (COX1) immunoreactivity in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM; A–D) and frontal cortex (fCx; E–H) of rhesus monkeys after SIV infection and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG. (A–D) The intensity of COX1 immunostaining in neurons (arrows) of the nbM is reduced in a monkey with AIDS (SIV,+AIDS) (C), as compared to a non-infected control (Ctrl) (A), and a SIV-infected monkey without AIDS (SIV,−AIDS) (B); this was not reversed by 6-Cl-ddG treatment in AIDS (SIV,+AIDS,+ddG) (D). (E–H) Reduction of neuronal COX1 immunostaining (arrows) in the fCX of an AIDS-diseased monkey (G) is reversed by 6-Cl-ddG treatment (H) to levels observed in a Ctrl (E) or a SIV,−AIDS monkey (F). There are COX1-positive microglia (arrowheads) intermingled between the neurons that demonstrate the same immunostaining intensity during disease as the neurons; the staining background in these sections is similar. Bar: 50 μm.

Table 2.

Infection Status, Treatment Regime, SIV Levels and Clinical Status at Time of Death and Necropsy of Monkeys

| Monkey No | SIV infection† | Drug treatment‡ | SIV in tissues§ | SIV in fluids# | Clinical status¶ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln/Spl | Brain | Plasma | CSF | ||||

| 44 | − | Not treated | ND | ND | ND | ND | No disease |

| 50 | − | Not treated | ND | ND | ND | ND | No disease |

| 69 | − | Not treated | ND | ND | ND | ND | No disease |

| 87 | − | Not treated | ND | ND | ND | ND | No disease |

| 75 | 2.5 | Not treated | + | − | − | n.a. | Asymptomatic |

| 80 | 6.5 | Not treated | + | − | − | n.a. | Asymptomatic |

| 85 | 4.5 | Not treated | ++ | − | − | n.a. | Asymptomatic |

| 92 | n.a. | Not treated | + | − | − | n.a. | Asymptomatic |

| 93 | 4.5 | Not treated | + | − | − | n.a. | Asymptomatic |

| 46 | 19 | Not treated | + | + | +++ | n.a. | AIDS |

| 71 | 6.5 | Not treated | ++ | ++ | ++ | n.a. | AIDS |

| 74 | 6 | Not treated | +++ | +++ | ++ | n.a. | AIDS |

| 78 | n.a. | Not treated | +++ | ++ | + | n.a. | AIDS |

| 79 | 2.5 | Not treated | + | + | n.a. | n.a. | AIDS |

| 82 | 3 | Not treated | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | AIDS |

| 86 | 4.5 | Not treated | +++ | +++ | n.a. | n.a. | AIDS |

| 70 | 6.5 | ddI/6-Cl-ddG | + | − | + | − | AIDS |

| 72 | 8 | ddI/6-Cl-ddG | −/+ | − | + | − | AIDS |

| 73 | 9 | ddI/6-Cl-ddG | +/++ | −/+ | + | + | AIDS |

| 83 | 4 | ddI/6-Cl-ddG | +/++ | − | ++ | − | AIDS |

| 89 | 22 | 6-Cl-ddG | ++ | − | +++ | ++ | AIDS |

| 91 | n.a. | ddI/6-Cl-ddG | + | − | +++ | + | AIDS |

Inoculation with SIV strain δB670. Time of infection and sacrifice is presented in months.

Treatment with ddI before with 6-Cl-ddG. Monkey 89 was treated only with 6-Cl-ddG.

Detection of SIV by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization in tissues. Sections from several lymphoid organs (axillar, inguinal and mesenterial lymph nodes, and spleen) and brain regions (frontal and parietal cortex, hippocampus, and basal ganglia) were analyzed for SIV gp120 and SIV RNA, summarized and scored as follows: − (no positive cells) to +++ (>100 cells/mm2).

Detection of SIV by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction in plasma and CSF at sacrifice. Plasma of asymptomatic monkeys (Nos. 75, 80, 85, 92 and 93) and AIDS monkeys (46, 71, 74, 78 and 82) were analyzed for SIV p26. CSF and plasma of untreated AIDS monkey 82 and antiretrovirally treated AIDS monkeys (70, 72, 73, 83, 89 and 91) were analyzed for SIV RNA. Scoring for SIV p26 was as: −(<1 ng/mL) to +++ (>30 ng/mL). SIV RNA was normalized to SIV particle number and scored as: −(<50 particles/mL) to +++ (>105 particles/mL).

Criteria defining AIDS included 1 or more of the following: anemia, loss of body weight over 10%, intractable diarrhoea/dehydration requiring fluid replacement, oral lesions/thrush and other opportunistic infections.

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; 6-Cl-ddG, 6-chloro-2′.3′-dideoxyguanosine; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ddI, 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine; Ln, lymph nodes; n.a., not applied; ND, not done; No, number; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus; Spl, spleen.

Table 3.

COX1- and COX2-positive Mononuclear and Endothelial Cell Immunoreactivity in Monkey Brainsduring SIV Infection and Antiretroviral Treatment

| Monkey groups | No. | Mononuclear cells† | Endothelial cells‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX1 | COX2 | COX1 | COX2 | ||||||

| Diffuse | Focal | Diffuse | Focal | Diffuse | Focal | Diffuse | Focal | ||

| Ctrl | 44 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − |

| 50 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 69 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 87 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| SIV,−AIDS | 75 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − |

| 80 | +/++ | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 85 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 92 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 93 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| SIV,+AIDS | 46 | + | + | − | + | + | NA | − | + |

| 71 | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | + | NA | − | ++ | |

| 74 | +++ | ++ | − | ++ | + | NA | − | +/++ | |

| 78 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + | NA | − | +++ | |

| 79 | +/++ | ++ | − | +/++ | + | NA | − | + | |

| 82 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + | NA | − | +++ | |

| 86 | +++ | +++ | − | ++ | + | NA | − | ++ | |

| SIV,+AIDS,+ddG | 70 | +/++ | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − |

| 72 | ++ | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 73 | ++ | −/+ | − | −/+ | + | NA | − | − | |

| 83 | ++ | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 89 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

| 91 | + | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | |

Immunohistochemistry for COX1 and COX2 was performed on sections of several brain regions (frontal and parietal cortex, hippocampus, and basal ganglia), analyzed, summarized and scored.

Diffuse mononuclear cell immunoreactivity was scored as: − (no staining), + (no signs of activation, more resting ramified type of microglia), ++(increased number of microglia), +++ (increased activation, phagocytic type of cells). Focal mononuclear cell immunoreactivity was scored as: − (no appearance of infiltrates, nodules, or multinucleated giant cells), + (low) to +++(severe encephalitis, high number of infiltrates, nodules, and multinucleated giant cells).

Diffuse endothelial cell immunoreactivity was scored as follows: − (no staining) and + (global vascular staining). Focal endothelial staining was scored as: − (no vessel staining), + (few) to +++(strong nodular vessel staining).

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; 6-Cl-ddG, 6-chloro-2′.3′-dideoxyguanosine; COX1/2, cyclooxygenase isotype-1/2; Ctrl, non-infected control animals; NA, not applicable; No, number; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus; SIV,−AIDS, SIV-infected animals without AIDS; SIV,+AIDS, SIV-infected animals with AIDS; SIV,+AIDS,+ddG, SIV-infected animals with AIDS and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of changes in neuronal cyclooxygenase 1 (COX1) immunoreactivity in the nucleus basalis of Meynert with the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (nbM/hdbB; A) and the frontal cortex (fCX; B) of rhesus monkeys after SIV infection and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG. Data are expressed as mean relative optical density (ROD). Each black dot represents a monkey. Analysis of variance and the post-hoc Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test were used to evaluate statistical differences among the groups. Values of p < 0.05 are marked with asterisks. Abbreviations: Ctrl, non-infected control animals (n = 3–4); SIV,−AIDS, SIV-infected animals without AIDS (n = 5); SIV,+AIDS, SIV-infected animals with AIDS (n = 6–7); SIV,+AIDS,+ddG, SIV-infected animals with AIDS and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG (n = 5–6).

To explore the influence of SIV burden and associated inflammation on the downregulation of COX1 in cholinergic neocortical projection neurons in AIDS, tissue sections of the BFC of monkeys that had been treated with the lipophilic 6-Cl-ddG (30–32) were also immunostained; these animals had clinical AIDS (SIV,+AIDS,+ddG; Table 2). The effects of 6-Cl-ddG on SIV levels in brain and lymphoid tissues, plasma and CSF, and on COX1/COX2-monitored mononuclear and endothelial inflammatory reactions, are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Reduction of neuronal COX1 expression of nbM and hdbB in monkeys with AIDS was not reversed by 6-Cl-ddG (Fig. 4D). The mean ROD of neuronal COX1 immunostaining in the SIV,+AIDS,+ddG group (47.4 ± 12.1) was not different from that in the SIV,+AIDS group (p > 0.05), but was still significantly reduced compared to controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5A).

A similar pattern of neuronal COX1 downregulation after SIV infection progressing to AIDS, with or without antiretroviral treatment, was observed in neurons of the vdbB and ventrally contiguous medial septum, i.e. BFC subnuclei whose cholinergic fibers project to the entorhinal-hippocampal cortex (9). Statistical analysis between all monkey groups with respect to neuronal COX1 immunostaining in vdbB and medial septum could not be performed because of limitation of available tissue blocks.

In contrast to the irreversible reduction in COX1 expression during progression to AIDS and subsequent antiretroviral treatment in BFC neurons, the mean ROD of COX1 immunostaining in neurons of the frontal cortex was reduced in SIV,+AIDS (59.9 ± 13.2; p < 0.05) vs. control (109.2 ± 14.1) and SIV,−AIDS (99.7 ± 16.5) (Figs. 4E-G, 5B), respectively, but was reversed in the SIV,+AIDS,+ddG group (102.6 ± 15.1; p < 0.05) (Figs. 4H, 5B).

Cholinergic Fiber Density Is Reduced in Target Areas of the BFC During SIV Infection and Is Not Restored in 6-Cl-ddG-Treated Monkeys

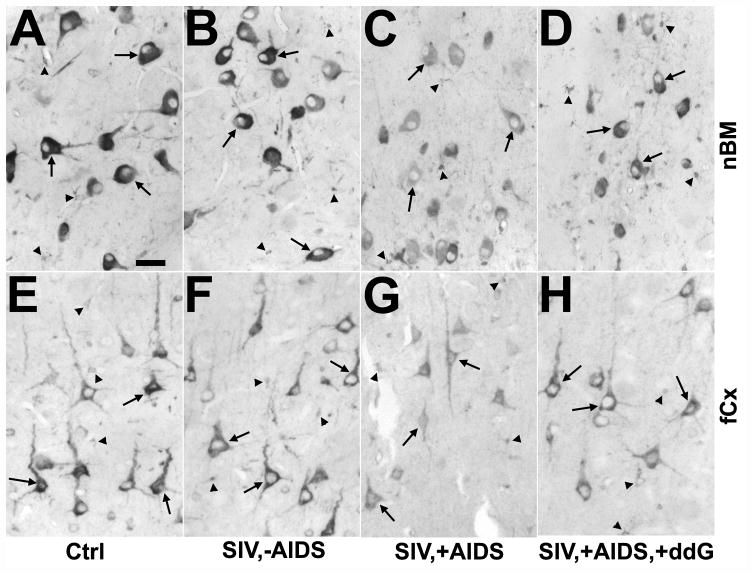

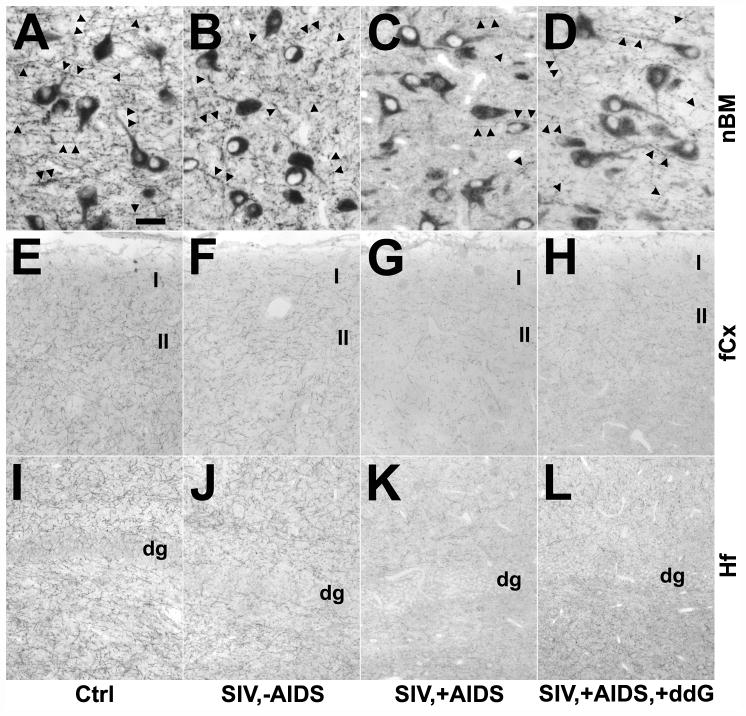

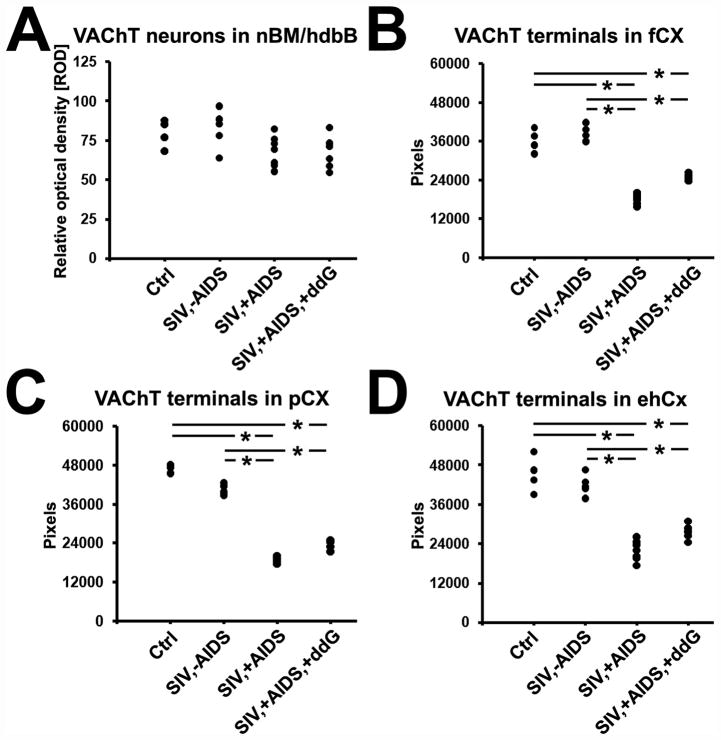

We next analyzed if reduction of COX1 expression in cholinergic neurons of the BFC might be accompanied by alteration in cholinergic terminals in the target areas of these neurons. For this purpose, IHC for VAChT was performed on neocortical target areas of the nbM and hdbB (frontal and parietal cortex), and on allocortical target areas of the vdbB and medial septum (entorhinal-hippocampal cortex) (9, 10). There was a reduction of VAChT-positive varicose fibers and synapses within the nbM itself, without apparent change in the appearance of the VAChT-positive somata in late stage disease (Fig. 6A-D). The mean ROD of VAChT immunoreactivity of neuronal cell bodies in nbM/hdbB was not significantly altered among the different monkey groups (Fig. 7A). By contrast, cholinergic fiber densities (presented as pixels) of the frontal and parietal cortices as well as of the entorhinal-hippocampal cortex were significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in SIV,+AIDS (frontal cortex: 18369.5 ± 1690.9, parietal cortex: 18865.5 ± 1019.9; entorhinal-hippocampal cortex: 21924.0 ± 3075.6) vs. SIV,−AIDS (frontal cortex: 38224.7 ± 2491.1, parietal cortex: 40465.9 ± 1666.5; entorhinal-hippocampal cortex: 41946.5 ± 3194.9) and control (frontal cortex: 36207.3 ± 3511.6, parietal cortex: 47104.0 ± 1114.7; entorhinal-hippocampal cortex: 45262.3 ± 5500.1), respectively. There was no apparent reversal of the loss in the SIV,+AIDS,+ddG group (frontal cortex: 24888.7 ± 1046.5, parietal cortex: 23534.6 ± 1290.1; entorhinal-hippocampal cortex: 27660.2 ± 2140.3) (p > 0.05) (Figs. 5E-L, 7B-D).

Figure 6.

Changes in cholinergic fibers in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM; A–D), frontal cortex (fCx; E–H) and hippocampal formation (Hf; I–L) of rhesus monkeys after SIV infection and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT). (A–D) The density of VAChT-positive varicose fibers and synapses (arrows) is decreased in the nbM of a monkey with AIDS (SIV,+AIDS) (C), as compared to a non-infected control (Ctrl) (A), and a SIV-infected asymptomatic monkey (SIV,−AIDS) (B). Antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG minimally reversed the VAChT-positive fiber loss in nbM in AIDS (SIV,−AIDS,+ddG) (D). The staining intensity of VAChT-positive neurons is not significantly altered during disease and treatment (B–D), as compared to Ctrl (A). (E–L) VAChT-positive terminals are reduced in the fCx (G) and Hf (K) of a SIV,+AIDS monkey as compared to a Ctrl monkey (E, I) and a SIV,−AIDS monkey (F, J). Treatment with 6-Cl-ddG does not prevent the reduction of VAChT-positive fibers in the fCx (H) and in the Hf (L) in late stage SIV disease. Group representative images show the upper laminae of fCx (I and II; E–H) and the area of dentate gyrus (dg; I–L). Bars: A–D, 50 μm; E–L, 200 μm.

Figure 7.

Quantitative analysis of changes in neuronal VAChT immunoreactivity in the nucleus basalis of Meynert with the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (nbM/hdbB; A) and of VAChT-positive terminals in frontal cortex (fCX; B), parietal cortex (pCX; C) and entorhinal-hippocampal cortex (ehCX; D) of the rhesus monkey after SIV infection and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG. Data are expressed as mean relative optical density (ROD) (A) or mean pixels (B–D). Each black dot represents a monkey. Analysis of variance and the post-hoc Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test were used to evaluate statistical differences between the groups. Values of p < 0.05 are marked with asterisks. Abbreviations: Ctrl, non-infected control animals (n = 3); SIV,−AIDS, SIV-infected animals without AIDS (n = 5); SIV,+AIDS, SIV-infected animals with AIDS (n = 6); SIV,+AIDS,+ddG, SIV-infected animals with AIDS and antiretroviral treatment with 6-Cl-ddG (n = 5).

In summary, in control monkeys, VAChT-positive terminal number and COX1 expression in BFC neurons are high. In SIV,+AIDS monkeys, VAChT-positive terminals and BFC COX1 expression are decreased. In SIV,+AIDS,+ddG monkeys, VAChT-positive terminals and neuronal COX1 expression in BFC remain decreased (as in the absence of treatment, i.e. 6-Cl-ddG treatment had no apparent effect); the only effect of 6-Cl-ddG was to decrease SIV burden and associated inflammation as evidenced by decrease in several markers of inflammation (30–32).

DISCUSSION

COX1 has been identified as a unique component of primate cholinergic telencephalic projection neurons and its expression is a dynamic marker for cholinergic synaptic patency. This opens an avenue of inquiry into the potential mediator role of prostaglandins in cholinergic neurotransmission. Loss of VAChT-positive terminals in cortex and hippocampus during SIV infection is accompanied by decreased COX1 expression in cholinergic BFC neurons. This decreased expression of COX1, as well as decreased number of cholinergic synapses of both cortical and hippocampal fields in SIV-infected rhesus brains, were not reversed in monkeys that had received antiretroviral therapy late in the course of SIV disease, even though both viral load and inflammation were dramatically decreased by the treatment. Thus, COX1 in nbM and VAChT staining in cortical projection areas are important biomarkers for irreversible brain changes occurring early in SIV disease.

COX1 expression has been reported to be widespread, if not ubiquitous, in brain neurons, and as such has not merited intense study as a specific marker for any single group of neurons as defined by neurotransmitter phenotype in the brain. Rather, COX2 expression, which is specific to several cortical neuronal systems and is induced in neurodegenerative conditions, has garnered significantly more attention in neuro-AIDS and Alzheimer disease (37–39). In part, this may be because detailed anatomical studies have focused on non-primate mammalian species such as rat and mouse (40). The unique and quite selective expression of COX1 in monkey and human cholinergic telencephalic projection neurons suggests a functional (mediator) role for prostaglandins synthesized in these neurons. What added capabilities (and vulnerabilities) prostaglandin synthesis imparts to these neurons in the primate remains to be determined, but altered COX1 expression might be expected to influence cholinergic neurotransmission and, therefore, cognition.

The observed presence of COX1 expression in cholinergic neurons of the BFC is of potential neuropharmacological as well as neuropathological interest in neuro-AIDS. COX1 and COX2 are differentially expressed in various cellular compartments of the brain during neuroinflammation, including in the course of SIV disease (32). This has provided a rationale for prostaglandin-related pharmacotherapy for neuroinflammatory disease (41, 42). The discovery of COX1 expression and function in a novel neuronal compartment has relevance for the type of COX inhibition, and the stage of disease at which it should be applied, in further consideration of this therapeutic approach. Identification of cholinergic neurons themselves as a source of prostaglandin synthesis is noteworthy because it has recently been suggested that prostaglandins may modulate the release and postsynaptic efficacy of acetylcholine in the brain, and that acetylcholine itself in turn modulates the production and release of brain prostaglandins (43, 44).

Although arachidonic acid is converted to prostaglandin H by either COX1 or COX2, and all other prostaglandins can be made from prostaglandin H, neurons might generate prostaglandin D2 rather than prostaglandin E (45). Indeed, prostaglandin D2 has been reported to be neuroprotective (46). Thus, it is possible that the generation of prostaglandin D2 is an endogenous neuroprotectant that buffers cholinergic neurons against damage sustained by chronic inflammation of cortex and hippocampus. If that is the case, downregulation of COX1 expression in cholinergic neurons during chronic SIV infection of the brain would lead to enhanced vulnerability of projection neuron synapses in cortex and hippocampus as reported in neuro-AIDS (47), and as reflected in the decreased cholinergic synaptic density in hippocampal and cortical projection areas we report.

Both HIV and SIV encephalitis are characterized by a global synaptodystrophy in cortical regions, manifested prominently in derangement in distribution or decreased expression of dendritic markers (6, 48, 49). However, a striking feature of neuro-AIDS (47, 50) is that HIV/SIV encephalitis, as defined by the appearance of mononuclear nodules and multinucleated giant cells in the brain parenchyma, is not necessarily an indicator of a functional encephalopathy. In fact, multiple studies in SIV-infected rhesus macaques suggested that postsynaptic derangement correlated with macrophage infection and macrophage-associated inflammation, whereas presynaptic changes, poorly correlated with encephalitis, might be a better indicator of cumulative and, as shown here, potentially irreversible synaptic derangement (6, 47, 49). Results of our present and previous studies (30–32), and that of others (51–53), confirm a progression in which SIV burden and associated appearance of microglial nodules and multinucleated giant cells are late and actually reversible with antiretroviral drugs. It is likely that neurochemical changes (and accompanying diffuse microglial activation) begin earlier and are not reversed by antiretroviral therapy administered after the onset of symptoms of AIDS. Early intervention with brain-permeable antiretroviral agents may sustain control of brain virus load, encephalitis, and progressive synaptic damage leading to hypofunction in cholinergic systems important for memory as well as dopaminergic systems important for motor function (54).

In the current study we carefully analyzed COX1 and VAChT by quantitative IHC in BFC and cortical/hippocampal fields during SIV disease and antiretroviral treatment. COX1 in BFC neurons was in the same way irreversibly reduced as VAChT was in terminal fields (but not in originating neurons itself) in late stage SIV disease. In contrast, decrease of COX1 in cortical neurons was reversible upon antiretroviral treatment in AIDS. We are aware of the technical limitations of our study, but we are certain that the detailed quantitative immunochemical analysis on the cellular level is robust with respect to molecular specificity. Determining net changes of COX1 levels and/or of its product prostaglandin might be performed by biochemical analyses of rhesus monkey tissue, as previously done for prostaglandins in the CSF and COX1 mRNA in frontocortical white matter tissue homogenates of HIV-infected patients (55). However, the interpretation of such data would be limited due to multicellular and multi-enzymatic sources of prostaglandins (and COX1) in the brain itself. The interpretation would be more complicated as COX1 and COX2 are spatio-temporally differentially expressed during SIV disease and antiretroviral treatment, as reported in our current and previous manuscript (32).

Conclusion

Whether cholinergic dysfunction is a causative factor in cognitive impairment in neuro-AIDS is a newly opened question that merits further investigation. It is noteworthy that in Alzheimer disease and SIV disease, cortical cholinergic markers are decreased while cell body cholinergic markers are less affected or unaffected. This suggests that both types of cognitive impairment may represent diseases of cholinergic synaptic dysfunction rather than cell loss. The connection between the cholinergic system, chronic lentiviral encephalitis, and regulation of a specifically cholinergic neuron-associated prostaglandin biosynthetic enzyme uncovered here in the context of neuro-AIDS is, therefore, intriguing in the context of neurodegenerative disease and primate cognitive function. Most urgently, a pathogenic mechanism of early and irreversible changes in this system in SIV disease supports the desirability of early intervention with brain-permeable antiretroviral therapeutics in human HIV disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Volkswagen-Stiftung (project numbers VW-I-71450 and VW-I-75184) and the NIMH Intramural Research Program (project number Z01 MH002386-24).

References

- 1.Sacktor N, McDermott MP, Marder K, et al. HIV-associated cognitive impairment before and after the advent of combination therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:136–42. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Murri R, et al. Neurocognitive impairment influences quality of life in HIV-infected patients receiving HAART. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:254–9. doi: 10.1258/095646204773557794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray EA, Rausch DM, Lendvay J, et al. Cognitive and motor impairments associated with SIV infection in rhesus monkeys. Science. 1992;255:1246–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1546323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: neuronal injury and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Cunha A, Rausch DM, Eiden LE. Early alterations in density of somatostatin mRNA-expressing neurons in frontal cortex of SIV-infected rhesus macaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1371–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissel SJ, Wang G, Ghosh M, et al. Macrophages relate presynaptic and postsynaptic damage in simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:927–41. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weed MR, Gold LH, Polis I, et al. Impaired performance on a rhesus monkey neuropsychological testing battery following simian immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:77–89. doi: 10.1089/088922204322749521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sailasuta N, Shriner K, Ross B. Evidence of reduced glutamate in the frontal lobe of HIV-seropositive patients. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:326–31. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesulam M-M, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, et al. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: Cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:170–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, et al. Atlas of cholinergic neurons in the forebrain and upper brainstem of the macaque based on monoclonal choline acetyltransferase immunohistochemistry and acetylcholinesterase histochemistry. Neuroscience. 1984;12:669–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, et al. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–17. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price DL, Martin LJ, Clatterbuck RE, et al. Neuronal degeneration in human diseases and animal models. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1277–93. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen KS, Masliah E, Mallory M, et al. Synaptic loss in cognitively impaired aged rats is ameliorated by chronic human nerve growth factor infusion. Neuroscience. 1995;68:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberini P, Cuello AC. Primate models of cholinergic dysfunction. Funct Neurol. 1995;10:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forster MJ, Dubey A, Dawson KM, et al. Age-related losses of cognitive function and motor skills in mice are associated with oxidative protein damage in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4765–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies P, Maloney MR. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1976;2:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, et al. Necropsy evidence of central cholinergic deficits in senile dementia. Lancet. 1977;1:189. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–90. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beach TG, Honer WG, Hughes LH. Cholinergic fibre loss associated with diffuse plaques in the non-demented elderly: the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease? Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93:146–53. doi: 10.1007/s004010050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bird TD, Stranahan S, Sumi SM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: choline acetyltransferase activity in brain tissue from clinical and pathological subgroups. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:284–93. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henke H, Lang W. Cholinergic enzymes in neocortex, hippocampus and basal forebrain of non-neurological and senile dementia of Alzheimer-type patients. Brain Res. 1983;267:281–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sims NR, Bowen DM, Allen SJ, et al. Presynaptic cholinergic dysfunction in patients with dementia. J Neurochem. 1983;40:503–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb11311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruberg M, Mayo W, Brice A, et al. Choline acetyltransferase activity and [3H}vesamicol binding in the temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and rats with basal forebrain lesions. Neuroscience. 1990;35:327–33. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90086-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strada O, Vyas S, Hirsch EC, et al. Decreased choline acetyltransferase mRNA expression in the nucleus basalis of meynert in Alzheimer disease: An in situ hybridization study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9549–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Fessler JA, et al. In vivo mapping of cholinergic terminals in normal aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:399–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efange SMN, Garland EM, Staley JK, et al. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter density and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:407–13. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer W, Wictorin K, Bjorklund A, et al. Amelioration of cholinergic neuron atrophy and spatial memory impairment in aged rats by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1987;329:65–8. doi: 10.1038/329065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mufson EJ, Lavine N, Jaffar S, et al. Reduction in p140-TrkA receptor protein within the nucleus basalis and cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1997;146:91–103. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beal MF, MacGarvey U, Schwartz KJ. Galanin immunoreactivity is increased in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:157–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Depboylu C, Reinhart TA, Takikawa O, et al. Brain virus burden and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase expression during lentiviral infection of rhesus monkey are concomitantly lowered by 6-chloro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2997–3005. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Depboylu C, Eiden LE, Schäfer MK, et al. Fractalkine expression in the rhesus monkey brain during lentivirus infection and its control by 6-chloro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1170–80. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000248550.22585.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depboylu C, Weihe E, Eiden LE. COX1 and COX2 expression in non-neuronal cellular compartments of the rhesus macaque brain during lentiviral infection. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsubokura S, Watanabe Y, Ehara H, et al. Localization of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase in neurons and glia in monkey brain. Brain Res. 1991;543:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breder CD, Smith WL, Raz A, et al. Distribution and characterization of cyclooxygenase immunoreactivity in the ovine brain. J Comp Neurol. 1992;322:409–38. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breder CD, Dewitt D, Kraig RP. Characterization of inducible cyclooxygenase in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:296–315. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamagata K, Andreasson KI, Kaufmann WE, et al. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron. 1993;11:371–86. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90192-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong PT, McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Decreased prostaglandin synthesis in postmortem cerebral cortex from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 1992;21:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90147-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Cyclooxygenase 2 RNA message abundance, stability, and hypervariability in sporadic Alzheimer neocortex. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:937–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<937::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Strong nuclear factor-kB-DNA binding parallels cyclooxygenase-2 gene transcription in aging and in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease superior temporal lobe neocortex. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:583–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980901)53:5<583::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tocco G, Freire-Moar J, Schreiber SS, et al. Maturational regulation and regional induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in rat brain: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1997;144:339–49. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi S-H, Aid S, Bosetti F. The distinct roles of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in neuroinflammation: implications for translational research. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi S-H, Aid S, Choi U, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 differentially modulate leokocyte recruitment into the inflamed brain. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;10:448–57. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue M, Crofton JT, Share L. Interactions between brain acetylcholine and prostaglandins in control of vasopressin release. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R420–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.2.R420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orman B, Reina S, Borda E, et al. Signal transduction underlying carbachol-induced PGE2 generation and cox-1 mRNA expression of rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:757–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vesin MF, Urade Y, Hayaishi O, et al. Neuronal and glial prostaglandin D synthase isozymes in chick dorsal root ganglia: a light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. J Neurosci. 1995;15:470–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00470.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang X, Wu L, Hand T, et al. Prostaglandin D2 mediates neuronal protection via the DP1 receptor. J Neurochem. 2005;92:477–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masliah E, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, et al. Dendritic injury is a pathological substrate for human immunodeficiency virus-related cognitive disorders. HNRC Group. The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:963–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masliah E, Ge N, Morey M, et al. Cortical dendritic pathology in human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Lab Invest. 1992;66:285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Q, Eiden LE, Cavert W, et al. Increased expression of nitric oxide synthase and dendritic injury in simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Hum Virol. 1999;2:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiley CA. Implications of the neuropathology of HIV encephalitis for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disorders. 1987;1:236–50. doi: 10.1097/00002093-198701040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xing HQ, Moritoyo T, Mori K, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in the white matter and degeneration of the cerebral cortex occur independently in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected monkey. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:508–18. doi: 10.1080/13550280390218904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xing HQ, Mori K, Sugimoto C, et al. Impaired astrocytes and diffuse activation of microglia in the cerebral cortex in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected Macaques without simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:600–11. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181772ce0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xing HQ, Hayakawa H, Gelpi E, et al. Reduced expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 and diffuse microglial activation in the cerebral cortex in AIDS cases with or without HIV encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:199–209. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819715df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray RA, Wilcox KM, Zink MC, et al. Impaired performance on the object retrieval-detour test of executive function in the SIV/macaque model of AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1031–35. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffin DE, Wesselingh SL, McArthur JC. Elevated central nervous system prostaglandins in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:592–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]