Abstract

Background

We were interested in examining the relationship between socially-relevant stimuli and decision processes in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

We tested patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls on a stochastically-rewarded associative learning task. Participants had to determine through trial and error which of two faces was associated with a higher chance of reward. One face was angry, the other happy.

Results

Both patients and healthy controls were able to do the task at above-chance accuracy, and there was no significant difference in overall accuracy between groups. Both groups also reliably preferred the happy face, such that they selected it more often than the angry face on the basis of the same amount of positive vs. negative feedback. Interestingly, however, patients were significantly more averse to the angry face, such that they chose it less often than control participants when the reward feedback strongly supported the angry face as the best choice.

Conclusions

Patients show an increased aversion to angry faces, in a task in which they must learn to associate rewards with expressions.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex disorder and deficits relative to controls have been seen across a broad range of behaviors. In the present study we were interested in examining the impact of social stimuli on learning and decision making processes. While patients have deficits in both decision-making and emotion recognition, these two avenues of research have proceeded independently. By investigating decision-making within a social context, we aimed to explore how deficits in these two domains interact with one another. Our task also allowed us to examine the implicit impact of emotional stimuli when a decision had to be made about those stimuli, as opposed to the explicit responses which are often used in emotion naming tasks.

Altered decision making in patients with schizophrenia has been shown using several different behavioural paradigms. For example, patients have been shown to have reversal learning deficits in associative learning tasks, (Murray et al., 2008, Waltz and Gold, 2007) as well as deficits learning from negative feedback (Waltz et al., 2007), learning categories in the Wisconsin card sorting task (Prentice et al., 2008), and learning to select from the advantageous deck in the Iowa gambling task (Premkumar et al., 2008b).

Another, perhaps more striking, feature of schizophrenia is that of poor social performance. The DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association. and American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV., 1994) stipulates that some level of social or occupational dysfunction be present for a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia and social impairment in childhood and adolescence is associated with subsequent psychosis onset (Done et al., 1994). Patients with schizophrenia appear to be impaired on various aspects of social cognition (Penn et al., 2008), including a reliable deficit in explicit emotion perception(Archer et al., 1994, Chen et al., 2009, Feinberg et al., 1986, Laroi et al., 2010, Linden et al., 2009, Meyer and Kurtz, 2009, Mueser et al., 1996, Norton et al., 2009, Premkumar et al., 2008a, Salem et al., 1996). Although several studies have reported some form of deficit in emotion perception, however, methodological shortcomings and task variability have led to inconsistencies(Edwards et al., 2002). While some authors have found impairments in the recognition of all emotions including happiness and surprise(Archer et al., 1994, Schneider et al., 1995), others have reported only difficulties with negative emotions, particularly fear(Gaebel and Wolwer, 1992, Mandal, 1987), although this could simply reflect the fact that positive emotions are easier to recognise(Gosselin et al., 1995).

The study reported here focused on how facial affect impacts on decision-making. We have developed a task in which participants were asked to determine through trial and error which of two faces (one smiling, one angry) is associated with a higher probability of reward. In healthy participants, the expressions biased decision-making even when the emotional valence of the face stimuli was irrelevant to the task (Averbeck and Duchaine, 2009). Given that previous work has shown that patients with schizophrenia have difficulty in some inference and associative learning tasks, as well as evaluating emotional expressions, we sought to clarify how social stimuli biased decision-making in this population. Our hypotheses, not all of which were born out by the data, were that patients with schizophrenia would a) recognise clear explicit expressions of happiness and anger; b) successfully learn the expectancies associated with the more rewarding faces, responding to implicit expressions; c) demonstrate a differential response to negative feedback, associated with poorer learning and d) demonstrate a differential response to happy versus angry faces, associated with increased aversion to negative emotion.

Methods and materials

Participants

We recruited 39 individuals (31 male) who met the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia from the outpatient department of South London and Maudsley NHS Trust. Patients were stable on treatment with antipsychotic medication (Table 1), those with dual diagnoses and drug and alcohol problems were excluded from the study. An age- (t75 = 1.8, p = 0.088) and IQ- (t75 = 1.7, p = 0.070) matched control group (n=38, 25 male) was also recruited. Patients underwent a PANSS diagnostic interview on the day of testing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographic information.

| Patient group (N = 39, Male = 31) | Control group (N = 38, Male = 25) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.9 (8.9) | 34.5 (13.2) |

| IQ | 105.0 (11.7) | 110.6 (14.7) |

| PANSS score | ||

| Positive | 14.0 (6.5) | |

| Negative | 14.1 (6.2) | |

| Total | 53.3 (16.5) | |

| Medication | ||

| Chlorpromazine Equivalents (mg/day) | 310 (228)* |

All data reported as Mean (s.d.).

This data was not available for 5 participants.

Task

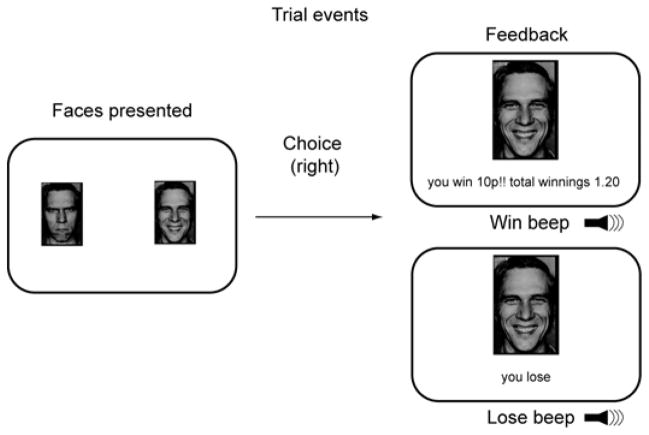

We employed a stochastically rewarded learning task using emotional faces as stimuli. The aim of the task was for the participant to try and ‘win’ on as many trials as possible, i.e. to determine through trial and error which face had a higher chance of being rewarded and select that face as many times as possible. On each trial, two faces were presented on a screen (Fig. 1). These faces had the same identity but differed in terms of facial expression - one was angry, the other happy. Each expression appeared pseudo-randomly on either the left or the right of the screen in each trial. The participants selected one of the faces using the keyboard and they were then told whether they won or lost on that trial. Feedback followed participant choice and was accompanied by the face that was chosen. A ‘win’ corresponded to 10p being added to the total winnings, a ‘loss’ meant that nothing was added, although they were explicitly given the feedback, “You lose” (Fig. 1). Participants were told that the amount they were paid depended in part on the amount of money they accrued. However in reality they were all paid the same amount. The financial incentive helped to ensure that participants engaged with the task.

Fig 1.

On each trial, participants were asked to choose between two faces (one angry, one happy). A subsequent feedback screen informed them of whether they had won or lost on that trial. The faces are rewarded differentially. The goal was to try and determine which face had a higher probability of leading to a ‘win’.

Each face was rewarded in each block according to a predetermined probability. The participant was told that one face in each block would be rewarded more often than the other but not given any further information (in actuality, one face was rewarded at 40%, the other 60%). The probabilities assigned to each face remained constant throughout each block which contained 26 trials. At the end of each block the probabilities were reassigned and the participant was informed when this happened and given a short break.

Two different identities were also used and these alternated across blocks: identity 1, identity 2, identity 1, identity 2. The reward associations were counterbalanced across blocks such that the identity 1 happy face was most often rewarded in 1 block and the identity 1 angry face was most often rewarded in 1 block and the same for identity 2. The order of happy vs. angry faces being rewarded was balanced, as much as possible across participants, such that happy faces were more often rewarded following angry faces as often as angry faces were more often rewarded following happy faces.

Prior to doing the task, a subset of participants were tested on a control task where they were asked to determine whether a face shown to them was happy or angry. The faces used in the main task were included in this series. This was to ensure that participants could perceive and differentiate the stimuli. All faces used in the study were male, and drawn from the Ekman set (Ekman and Friesen, 1971).

Data Analysis

At the beginning of each block of trials the participants were told that the probabilities had been reassigned and they should try to work out by trial and error which face was best. Thus, at the beginning of the block the participants had no evidence about which face was best and they had to begin selecting one or the other face, registering the feedback, and trying to work out which face was best. Although one face was rewarded more often than the other, the probabilities used were 0.6 and 0.4 and as such the task was challenging. It was even possible that over short intervals the face which had a lower probability of being rewarded would be rewarded more often than the other. Therefore, we referenced the participants’ behavior to an ideal observer model which estimated, based on all of the feedback received up to the current trial in the block, which face was best. By comparing each participant’s choices to the ideal observer trial-by-trial, a fraction correct could be derived, as a baseline estimate of performance.

Since the outcome in each trial was either win or lose, the ideal observer was based upon a binomial model. The likelihood that the rewards were being generated probabilistically by an underlying probability θi is given by:

| (1) |

Here, D is the observed series of outcomes, θi is the probability that face i (angry or happy) is rewarded, ri is the number of times face i was rewarded, and Ni is the number of times face i was selected. This equation provided us with the distributions over reward probabilities for each face. Specifically, as the participants did not know the underlying probabilities, they would infer a distribution of possible probabilities, given the reward outcomes. For example, if one observed 7 heads in 10 coin tosses, it would be possible that the coin was fair (i.e. p=0.5 of heads vs. tails), but it would also be possible, in fact more likely given the outcomes, that the coin was unfair and had a probability of heads equal to 0.7. Equation 1 would give the complete distribution over the probabilities for some set of outcomes.

To make a decision, the participants had to decide which face was better. We operationalized this decision step by assuming that participants would compute the probability that face i was more often rewarded than face j. This was given by:

| (2) |

The integral is over the posterior. For the ideal observer the prior was flat, and as such, the posterior is just the normalized likelihood. As a decision rule, this probability was thresholded at chance. This gives the ‘ideal choice’ (f̂).

| (3) |

For the analyses which compared the decision of the participant to the “choice” of the ideal observer, the case of p(θi > θj) = 0.5 was handled by incrementing both the happy and the angry choice of the ideal observer by 0.5.

See supplemental material for details of the parameterized Bayesian learning model.

Results

We carried out a control task in a subset of patients (N = 20) and controls (N = 20) and found that they all showed 100% accuracy in being able to discriminate between the angry and happy faces we used in this study. In the first analyses of the decision making task, behaviour was referenced to an ‘ideal observer’ model (see methods). It is not possible to ensure that participants were rewarded a fixed number of times for each face in each block, because we could not control which face they picked. The ideal observer, however, allows one to indicate what the participants should do, while allowing the participants unconstrained choice behaviour, which is more natural. Thus, the ideal observer allowed us (a) to check whether participants were able to do the task, as the ideal observer provided an estimate of whether the participants were learning from the feedback and (b) to see whether participant choices showed a preference for the happy or angry expression. Percent correct was given by the percentage of responses which agreed with that of the ideal observer.

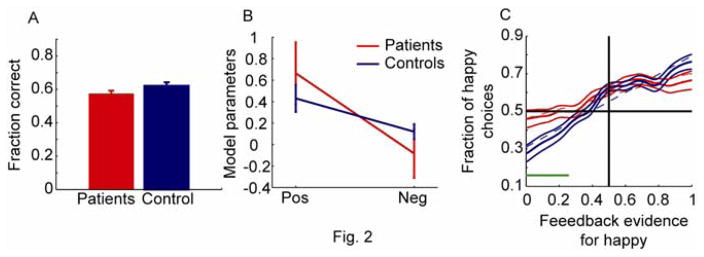

In general, this is a difficult learning task as the reward probabilities we used in each block were 60% and 40% for the most and least often rewarded face. Analyzed group-wise, patients and controls performed significantly above chance (50%) on the task (patients: t38 = 3.89, p < 0.001; controls: t37 = 6.35, p < 0.001). Patient choices concurred with the ideal observer 57% of the time and control choices concurred 62% of the time (Fig. 2A). The difference in performance between patients and controls approached but did not achieve significance (t75 = 1.84, p = 0.070). Analyzed individually, 44% of patients (p < 0.05, χ2 on choices of individual participant) and 53% of controls (p < 0.05, χ2) were individually above chance. These proportions were, however, not significantly different (Z-test, Z = 0.549, p = 0.583). Furthermore, both patients and controls showed a significant preference for the happy face. The average difference between choosing the happy face when they should have chosen the angry face (p(participant=happy|model=angry)) and choosing the angry face when they should have chosen the happy face (p(participant=angry|model=happy)) was 0.17 for both groups (patients: t38 = 4.79, p < 0.001; controls: t37 = 4.49, p < 0.001). That is, when responses differed from the predictions of the ideal observer, there was a significantly higher probability of participants choosing happy when they should have chosen angry, compared to choosing angry when they should have chosen happy. There was, however, no significant difference in the overall preference between patients and controls (t75 = 1.31, p = 0.195), when averaged across conditions in this way. Thus, both groups learned from the feedback, although this was not true of all individual participants, and both groups showed a preference for the happy face.

Fig. 2.

Between group differences in learning and face preferences. A. Fraction correct, referenced to the ideal observer when choosing between happy and angry faces in drug and placebo conditions. Error bars are +/− 1 s.e.m. B. Difference in learning from positive and negative feedback. Error bars are +/− 1 s.e.m. Positive (Pos) is parameter α from equation 4 in supplemental methods. Negative (Neg) is parameter β from equation 5 in supplemental methods. C. Evidence vs. choice probability curves. Fraction of times participants picked the happy face, give the evidence for the happy face, under drug and placebo conditions. The evidence comes from the ideal observer model, and is given by p(θhappy >θangry) from eqn. 2.

In the next analysis we split the total learning in the task into the amount learned from positive and negative feedback. This is a more detailed analysis, and previous studies have suggested that striatal dopamine levels may affect the relative amount learned from positive and negative feedback (Cools et al., 2009, Frank et al., 2004, Pessiglione et al., 2006, Waltz et al., 2007). Thus, given the dopamine hypothesis in schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al., 1998, Davis et al., 1991, Laruelle et al., 1996, Weinberger, 1987), we wanted to examine group differences in these parameters. We used a Bayesian reinforcement learning model (see supplemental methods) to estimate the amount that individual participants learned from positive and negative feedback (Fig. 2B). When we compared this across groups using a mixed effects ANOVA, however, we found that there was no main effect of group (F1,75 = 0.01, p = 0.941) and no interaction of group and valence (i.e. positive (α) vs. negative (β) F1,75 = 1.35, p = 0.249). There was a main effect of valence, across groups (F1,75 = 7.88, p = 0.006) attributable to consistent task strategies between groups.

Next, we examined the evidence vs. choice probability curves, which characterize how often participants picked each of the faces, as a function of the strength of the evidence supporting each face. For example, if a participant had picked the happy face 4 times and won 3 times and picked the angry face 4 times and won 3 times, the evidence would be equivocal (Feedback evidence for happy = 0.5). However, if the participant had received proportionally more positive feedback for the angry face than the happy face, the feedback evidence would favour the angry face, and vice-versa. We found that both groups showed the preference towards the happy face revealed by the analysis above (Fig. 2C), indicated by the shift of the evidence vs. choice probability curves up and to the left. However, the choice aversion to the angry face was stronger in the patients than controls, evidenced by the separation of the curves in the left half of the plot, when the evidence strongly favoured the angry face. Bin-by-bin t-tests confirmed this difference (Fig. 2C–green line at y = 0.15).

These t-tests are subject to the multiple comparisons criticism, but the results are robust when examined using a regression based approach, which avoids this criticism. To evaluate this effect while avoiding the problem of multiple comparisons we fit the following regression to the evidence-choice probability data, participant-by-participant in both groups:

This analysis gives us four parameters (a0, a1, a2 and a3) for each participant. Across participants within a group we can then carry out t-tests on each individual parameter distribution to see if it is significant within that group. In other words, we get 39 values of parameter a0 for the patient group, and a t-test on that distribution tells us if that parameter is significantly positive or negative within that group. We found that the 2nd and 3rd order terms were not significant in either group so we refit the equations with only the intercept (a0) and linear (a1) terms. Both of these terms were significant in both groups (patients: a0: t38 = 11.8, p < 0.001; a1: t38 = 3.1, p = 0.003; controls: a0: t37 = 8.1, p < 0.001; a1: t37 = 6.9, p < 0.001). We then carried out t-tests on the parameter distributions between groups to assess significance. This is equivalent to a random effects model (Holmes and Friston, 1998) and thus we only carry out 2 t-tests to determine significance. We found that both the intercept and linear terms were significantly different between groups (a0: t75 = 2.81, p = 0.006; a1: t75 = 2.46, p = 0.016). Both of these would remain significant if corrected for the two comparisons using Bonferroni correction. Importantly, the significant intercept effect shows that when the evidence strongly supports the angry face (Feedback evidence happy = 0) control participants selected the angry face significantly more often. Incidentally, both the intercept and linear terms were also significantly different between groups when we included the 2nd and 3rd order terms (data not shown). The change in the slope reflects the overall decrease in performance of the participants (Fig. 2A). When assessed as the slope of the evidence vs. choice probability curve there is a significant difference between groups.

To further characterize this effect, we examined whether or not patients and controls were able to identify the best face at above chance levels when the evidence either strongly supported the happy face (Feedback evidence for happy = 1), or strongly supported the angry face (feedback evidence for happy = 0). When the evidence strongly supported the happy face, both groups were above chance (patients: t38 = 5.3, p < 0.001; controls: t37 = 7.8, p < 0.001). However, when the evidence strongly supported the angry face only the controls were significantly above chance (patients: t38 = 1.0, p = 0.329; controls: t37 = 5, p < 0.001). Thus, patients were able to pick the happy face as better when the evidence supported it, but not the angry face.

Patients have been shown to have reversal learning deficits (Waltz and Gold, 2007). However, we were not specifically interested in studying those deficits, so the task was designed to minimize those factors, using explicit breaks between blocks and onscreen instructions to the participants during the break between blocks that probabilities were randomly being reassigned. Furthermore, two identities were used and they were always presented in interleaved blocks I1, I2, I1, I2. There were no effects of carryover within either group (see supplemental material).

Next, we carried out a series of control analyses to assess correlations between PANSS scores, medication levels and our dependent behavioural variables, specifically the regression parameters for the face preference effect (a0 or a1) and the parameters assessing learning from positive and negative feedback (α and β from equations 4 and 5 of methods, plotted as positive and negative in Fig. 2B). There were no significant correlations between any of the 3 PANSS scores (positive, negative and general) and the two parameters from the regression (a0 or a1) with all p > 0.05. We also examined correlations between a combined delusion score (delusions, hallucinations, suspiciousness and hostility) and the regression parameters, but there were no significant correlations (p > 0.05). There was a significant correlation between the general symptom score and learning from positive feedback (α, r38 = 0.36, p = 0.04) but the rest of the correlations were non-significant. There was a significant correlation between medication levels measured in chlorpromazine equivalent units and both parameters from the regression (a0: r38 = 0.36, p = 0.047 and a1: r38 = −0.40, p = 0.025), but no correlation between medication levels and learning from positive and negative feedback.

As we found a correlation between medication levels and the regression parameters, we included medication level as a covariate, along with overall percent correct and IQ. Even when these variables were partialed out of the regression, there was still a group difference in the intercept term (a0, t75 = 11.7, p < 0.001). Finally, we ran an analysis to control for the effect of gender, as the proportions were not identical across groups. Gender was not a significant predictor of the intercept (a0) across groups (F1, 73 = 0.39, p = 0.534) nor was there a significant interaction between group and sex (F1,73 = 0, p = 0.979) and the effect of groups was still significant (F1,73 = 5.51, p = 0.022). Thus, this effect survives correction for possible confounding factors.

Discussion

We tested patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls on a stochastically-rewarded decision-making task using emotional faces as stimuli. Both patients and controls were able to recognise faces explicitly and showed a significant preference in favour of selecting the happy face, a preference which has previously been documented in an independent group of control participants (Averbeck and Duchaine, 2009). Assessed as overall percent correct, we found that patients could determine which face was being most often rewarded as well as control participants with a trend towards a deficit. The slope of the regression line from the evidence vs. choice probability curves was, however significantly different between groups. Importantly for the present study, the choice behaviour of the patients was significantly more averse to the angry faces than healthy controls, such that when the feedback evidence strongly supported the angry face as the best choice, patients chose it significantly less often and in fact patients performed at chance in this condition. This difference did not exist for happy faces however as patients were able to perform above chance levels when the happy face was more often rewarded. Thus, patients and controls learn to associate rewards to happy and angry faces differently.

Although excessive striatal dopamine has been consistently implicated in schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al., 1998, Bortolozzi et al., 2007, Breier et al., 1997, Laruelle et al., 1996) and modelling and experimental work has suggested that striatal dopamine levels are related to differences in learning from positive and negative feedback (Cools et al., 2006, Cools et al., 2009, Djamshidian et al., 2010, Frank et al., 2007, Frank et al., 2004, Pessiglione et al., 2006, Rutledge et al., 2009, Voon et al., 2010, Waltz et al., 2007), we did not find strong differences between patients and controls in this aspect of the task. In the study of Waltz et al., (Waltz et al., 2007) patients slightly outperformed controls in initial acquisition of the most difficult 60/40 split, which used reward contingencies equivalent to ours. Consistent with this, it has been reported that patients have intact initial acquisition of preference for rewarded stimuli (Herbener, 2009). Some authors have shown that patients with schizophrenia show deficits specifically when reward contingencies are reversed (Waltz and Gold, 2007) and other authors have shown deficits in first episode patients specifically during initial acquisition but not in all forms of reversal learning (Murray et al., 2008). Other authors have suggested that deficits, at least in the Wisconsin Card Sorting task which uses deterministic and not stochastic feedback, is in initial acquisition and not reversal (Prentice et al., 2008). Our results show relatively intact acquisition of associations in the patient group, with most of the deficit in learning being driven by an increased aversion to the angry faces. Finally, with respect to this finding it is worth noting that the reward prediction error hypothesis of dopamine (Schultz, 2002) does not predict differences between initial acquisition and reversals. Such differences are often seen, however, which suggests that there is much about this process that is still not understood.

Although studies have documented deficits in processing emotional expressions in patients (Archer et al., 1994, Chen et al., 2009, Feinberg et al., 1986, Laroi et al., 2010, Linden et al., 2009, Meyer and Kurtz, 2009, Mueser et al., 1996, Norton et al., 2009, Salem et al., 1996), including a specific misattribution of fearful faces as angry (Premkumar et al., 2008a). Our study shows that, under some conditions, patients are more sensitive to expressions than controls. Specifically, patients and controls both showed a statistically significant preference for the happy face. Patients, however, were significantly more averse to the angry face and thus patients appeared to be relatively more sensitive to the angry face. Other studies have reported emotion recognition effects that were specific to angry. This is consistent with work showing that positively valenced emotional material does not improve long-term memory in patients as it does in controls, but negatively valenced emotion material does (Herbener et al., 2007). This is in contrast to work examining labelling of emotions, which has shown that there are deficits in identifying happy or angry faces (Archer et al., 1994, Laroi et al., 2010, Linden et al., 2009, Schneider et al., 1995). While it might be argued that the behavioural differences between patients and controls seen for angry faces in our task might be due to an underlying perceptual deficit, it should be noted that the same perceptual process is engaged independent of the evidence favouring happy or angry faces, and our control task showed that given a two-alternative forced choice decision, patients can reliably determine whether a face is smiling or angry. The behavioural difference we see, however, is specific to cases in which participants have received reward evidence that the angry face is the choice which will most often win.

There are limitations to our study. First, we did not use an explicit punishment condition. Our loss condition used negative text, “You lose”, but in fact participants simply did not earn anything on those trials. It is possible that an explicit loss condition would have differentially affected learning behaviour – perhaps more specifically enhancing the negative feedback. Our approach is, however, consistent with previous work which used lack of reward as a negative outcome (Waltz et al., 2007). Furthermore, care must be taken, when losses are used explicitly, as they are not treated the same as gains (Kahneman et al., 1982), and adding a condition to study losses would have considerably extended the task. Additionally, as discussed above, patients were at chance performance when the evidence strongly supported the angry face. The choice behaviour in this case should have been driven by both a lack of reward for the happy face, and reward assigned to the angry face. However, if patients simply could not assign reward to the angry face, the two faces may have seemed equally rewarding. This seems unlikely, however, as the patients do pick the angry face more often when it is being more often rewarded as shown by the significant slope in the evidence vs. choice probability curve, which suggests that they do incorporate reward information about the angry face.

Conclusion

We employed a task which allowed us to examine the effects of financial feedback and emotional expressions simultaneously on choice behavior and found that patients with schizophrenia showed a larger aversion to angry faces than control participants. As our task is not a simple perceptual task, but rather requires participants to engage in choice behaviour, it may engage brain processes that are closer to social behavioural deficits seen in patients. Additional studies linking this task with parallel social cognition tasks will be necessary to examine this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank to all the volunteers who participated in this study. This work was supported by a Welcome Trust Project Grant to BBA, SSS was supported by a HEFCE Clinical Senior Lecturer Award and MRC funding within the UCL 3 Year PhD in Neuroscience to SE. This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Program of the NIH, National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Krystal J, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Bowers M, van Dyck CH, Charney DS, Innis RB, Laruelle M. Increased striatal dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: confirmation in a second cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:761–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. & American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Hay DC, Young AW. Movement, face processing and schizophrenia: evidence of a differential deficit in expression analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 1994;33 (Pt 4):517–28. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Duchaine B. Integration of social and utilitarian factors in decision making. Emotion. 2009;9:599–608. doi: 10.1037/a0016509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolozzi ALD-M, Artigas F. Pharmcology. In: Buschmann H, Diaz JL, Holenz J, Parraga A, Torrens A, Vela JM, editors. Antidepressants, Antipsychotics, Anxiolytics. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2007. pp. 389–448. [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, Weinberger DR, Weisenfeld N, Malhotra AK, Eckelman WC, Pickar D. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Norton D, McBain R, Ongur D, Heckers S. Visual and cognitive processing of face information in schizophrenia: detection, discrimination and working memory. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Altamirano L, D’Esposito M. Reversal learning in Parkinson’s disease depends on medication status and outcome valence. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:1663–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Frank MJ, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, D’Esposito M. Striatal dopamine predicts outcome-specific reversal learning and its sensitivity to dopaminergic drug administration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1538–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4467-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Kahn RS, Ko G, Davidson M. Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1474–86. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamshidian A, Jha A, O’Sullivan SS, Silveira-Moriyama L, Jacobson C, Brown P, Lees AJ, Averbeck BB. Risk and learning in impulsive and nonimpulsive patients with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1002/mds.23247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Done DJ, Crow TJ, Johnstone EC, Sacker A. Childhood antecedents of schizophrenia and affective illness: social adjustment at ages 7 and 11. BMJ. 1994;309:699–703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6956.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE. Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:789–832. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;17:124–9. doi: 10.1037/h0030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg TE, Rifkin A, Schaffer C, Walker E. Facial discrimination and emotional recognition in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:276–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030094010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Moustafa AA, Haughey HM, Curran T, Hutchison KE. Genetic triple dissociation reveals multiple roles for dopamine in reinforcement learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16311–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706111104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O’Reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science. 2004;306:1940–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W, Wolwer W. Facial expression and emotional face recognition in schizophrenia and depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;242:46–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02190342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin P, Kirouac G, Dore FY. Components and recognition of facial expression in the communication of emotion by actors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:83–96. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES. Impairment in long-term retention of preference conditioning in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1086–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Rosen C, Khine T, Sweeney JA. Failure of positive but not negative emotional valence to enhance memory in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:43–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AP, Friston KJ. Generalisability, random effects and population inference. NeuroImage. 1998;7:s754. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroi F, Fonteneau B, Mourad H, Raballo A. Basic emotion recognition and psychopathology in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:79–81. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c84cb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Gil R, D’Souza CD, Erdos J, McCance E, Rosenblatt W, Fingado C, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Charney DS, Innis RB. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden SC, Jackson MC, Subramanian L, Wolf C, Green P, Healy D, Linden DE. Emotion-cognition interactions in schizophrenia: Implicit and explicit effects of facial expression. Neuropsychologia. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal MK. Decoding of facial emotions, in terms of expressiveness, by schizophrenics and depressives. Psychiatry. 1987;50:371–6. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1987.11024368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MB, Kurtz MM. Elementary neurocognitive function, facial affect recognition and social-skills in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;110:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Doonan R, Penn DL, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Nishith P, DeLeon J. Emotion recognition and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:271–5. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GK, Cheng F, Clark L, Barnett JH, Blackwell AD, Fletcher PC, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET, Jones PB. Reinforcement and reversal learning in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:848–55. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton D, McBain R, Holt DJ, Ongur D, Chen Y. Association of impaired facial affect recognition with basic facial and visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1094–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Sanna LJ, Roberts DL. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:408–11. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature. 2006;442:1042–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar P, Cooke MA, Fannon D, Peters E, Michel TM, Aasen I, Murray RM, Kuipers E, Kumari V. Misattribution bias of threat-related facial expressions is related to a longer duration of illness and poor executive function in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2008a;23:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar P, Fannon D, Kuipers E, Simmons A, Frangou S, Kumari V. Emotional decision-making and its dissociable components in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a behavioural and MRI investigation. Neuropsychologia. 2008b;46:2002–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice KJ, Gold JM, Buchanan RW. The Wisconsin Card Sorting impairment in schizophrenia is evident in the first four trials. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge RB, Lazzaro SC, Lau B, Myers CE, Gluck MA, Glimcher PW. Dopaminergic drugs modulate learning rates and perseveration in Parkinson’s patients in a dynamic foraging task. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15104–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3524-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem JE, Kring AM, Kerr SL. More evidence for generalized poor performance in facial emotion perception in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:480–3. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Gur RC, Gur RE, Shtasel DL. Emotional processing in schizophrenia: neurobehavioral probes in relation to psychopathology. Schizophr Res. 1995;17:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00031-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Reynolds B, Brezing C, Gallea C, Skaljic M, Ekanayake V, Fernandez H, Potenza MN, Dolan RJ, Hallett M. Impulsive choice and response in dopamine agonist-related impulse control behaviors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;207:645–59. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1697-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, Frank MJ, Robinson BM, Gold JM. Selective reinforcement learning deficits in schizophrenia support predictions from computational models of striatal-cortical dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:756–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, Gold JM. Probabilistic reversal learning impairments in schizophrenia: further evidence of orbitofrontal dysfunction. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]