Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to examine the associations between reported exposure to anti-smoking warnings at the point-of-sale (POS) and smokers’ interest in quitting and their subsequent quit attempts by comparing reactions in Australia where warnings are prominent to smokers in other countries.

Design

A prospective multi-country cohort design was employed.

Setting

Australia, Canada, the UK and the US.

Participants

21,613 adult smokers who completed at least one of the seven waves (2002-2008) of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey were included in the analysis.

Measurements

Reported exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings and smokers’ interest in quitting at the same wave and quit attempts over the following year.

Findings

Compared to smokers in Canada, the UK and the US, Australian smokers reported higher levels of awareness of POS anti-smoking warnings, and this difference was consistent over the study period. Over waves in Australia (but not in the other three countries) there was a significantly positive association between reported exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings and interest in quitting (adjusted odds ratio = 1.139, 95% CI 1.039~1.249, p<0.01) and prospective quit attempts (adjusted odds ratio = 1.216, 95% CI 1.114~1.327, p<0.001) when controlling for demographics, smoking characteristics, overall salience of anti-smoking information, and awareness of anti-smoking material from channels other than POS.

Conclusions

Point-of-sale health warnings about tobacco are more prominent in Australia than US, UK or Canada and appear to act as a prompt to quitting.

INTRODUCTION

Increasing numbers of countries have acted to restrict/ban tobacco advertising and promotion in traditional media such as television, radio, print and on billboards (1-5). The tobacco industry has responded by expanding their marketing in areas where it is still allowed (6, 7). Point-of-sale (POS) tobacco promotion has become an important marketing channel for the tobacco industry as other marketing opportunities have been banned (8). The tobacco industry in the United States (US) has spent the vast majority of their promotional budget in the retail environment over the past decade (9). This ranges from promotional material, to payments for shelf space and incentive schemes for retailers.

A number of jurisdictions have banned POS tobacco advertising, and some are now moving to prohibit the display of tobacco products - putting tobacco products under the counter. Regardless of these restrictions, there are good reasons for having prominent POS anti-smoking warnings. This is the time when smokers purchase cigarettes, so it should be a critical time to have them thinking about the harms. However, there is little empirical evidence to support such initiatives.

During the study period (2002-2008), Australia had notably stronger POS anti-smoking warnings than did the other three countries in the study (Canada, the United Kingdom (UK) and the US). Australia has had prominent POS warnings for some time, but with some variation across states. For example, the most populous state of New South Wales requires a health warning message (eg, ‘Smoking is addictive’) and a Quitline number (131 848), that features: 1) black writing on a white background; and 2) between 50 and 100 centimetres (cm) wide and have an area not less than 2,000cm2 (10) (See Figure 1). In the second most populous state of Victoria, similar warnings are mandated near the POS or at the shop entrance. However, they are smaller in Victoria (A4 in size (21 × 29.7cm)) (11). In Queensland, under the Tobacco and Other Smoking Products Amendment Act 2004, from December 2005 all the retail outlets are required to display mandatory POS anti-smoking signs that encourage quitting. Two other states (South Australia and Western Australia) that began the 2002-08 study period with weaker signs, strengthened them to be similar to those of New South Wales and Victoria during the study period.

Figure 1.

An example of Australian point-of-sale anti-smoking warnings

(Notes: This picture was taken in a supermarket in New South Wales during the study period. Source: Simon Chapman of University of Sydney & Anne Jones of Action on Smoking and Health Australia).

In Australia, POS anti-smoking warnings have been integrated with other health communication strategies, such as mandating health warnings on cigarette packets and ongoing mass media campaigns that all have emphasized the health harms of smoking and promoted the Quitline number, sometimes using the same base materials (12-14).

Warnings at the POS are less prominent in the other countries. Some provinces of Canada started to mandate POS warnings from around 2004/05 (15, 16), but most do not have size requirements. Pictorial warnings at the POS were only introduced in some provinces of Canada (eg, British Columbia) from early 2008. In the UK, the Tobacco Advertising and Promotion (Point of Sale) Regulations 2004 allowed only one A5 sized (14.8×21 cm) poster advertising tobacco in store with 30% of that area taken up with a health warning (eg, “smoking seriously harms you and others around you”, in force from December 2004) (17). The US has no systematic requirements for POS anti-smoking information.

We expected an overall higher level of awareness of POS warnings in Australia, and given the improvements in regulations regarding POS warnings over the study period, increases in awareness in Australia, Canada and the UK overtime. We were also interested in determining if reported awareness of POS warnings were associated with higher quitting interest and prospectively, with higher levels of quitting activity, and whether this varied by country (in this case a proxy for warning strength).

METHODS

Data source and participants

The data comes from the first seven waves of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey (the ITC-4 Survey), which has been running annually since 2002 in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US. A detailed description of the conceptual framework and methods of the ITC-4 Survey has been reported by Fong et al (2006) and Thompson et al (2006) (18, 19), and more detail is available at http://www.itcproject.org. Briefly, the ITC-4 Survey employs a prospective multi-country cohort design and involves annual telephone surveys of representative cohorts of adult smokers in each of the four countries. The sampling is conducted via random-digit dialling. The sample size per country is approximately 2,000. At each survey wave, the approximately 30% lost to follow-up are replenished from the same sampling frame.

Participants were aged 18+ years, had smoked at least 100 cigarettes lifetime, and had smoked at least once in the past 30 days at the time of recruitment. A total of 21,613 respondents who provided complete information for at least one of the seven waves (between 2002 and 2008) were included in the analysis. The sample size for each country, the numbers of recruits in each wave/year, and their characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics, by country.

| Australia n=4,806 |

Canada n=5,265 |

UK n=5,251 |

US n=6,291 |

Total n=21,613 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% female) | 53.5 | 53.7 | 55.8 | 55.1 | 54.6 |

| Identified minority group (%) | 12.8 | 11.3 | 4.9 | 20.3 | 12.7 |

| Age at recruitment (%) | |||||

| 18-24 | 14.2 | 12.8 | 8.5 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

| 25-39 | 35.6 | 30.3 | 31.3 | 26.3 | 30.6 |

| 40-54 | 34.0 | 36.5 | 33.8 | 36.6 | 35.3 |

| 55+ | 16.1 | 20.4 | 26.4 | 25.5 | 22.4 |

| Education at recruitment (%)# |

|||||

| Low | 64.1 | 48.6 | 60.6 | 45.8 | 54.1 |

| Moderate | 21.9 | 36.4 | 25.1 | 38.3 | 30.9 |

| High | 13.9 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 15.9 | 14.6 |

| Income at recruitment (%)# |

|||||

| Low | 26.9 | 28.3 | 31.1 | 36.9 | 31.2 |

| Moderate | 32.7 | 34.4 | 31.5 | 33.3 | 33.0 |

| High | 34.0 | 28.4 | 27.6 | 22.7 | 27.8 |

| No information | 6.5 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 8.1 |

| Cigarettes per day at recruitment (%) |

|||||

| 1-10 | 29.8 | 31.4 | 29.8 | 31.1 | 30.6 |

| 11-20 | 40.1 | 42.7 | 53.4 | 45.8 | 45.6 |

| 21-30 | 22.8 | 21.1 | 11.7 | 13.1 | 16.9 |

| 31+ | 7.1 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 9.4 | 6.6 |

| No. of new recruits in each wave (n) |

|||||

| Wave 1 (in 2002) | 2,305 | 2,214 | 2,401 | 2,138 | 9,058 |

| Wave 2 (2003) | 258 | 517 | 255 | 684 | 1,714 |

| Wave 3 (2004) | 532 | 545 | 586 | 889 | 2,552 |

| Wave 4 (2005) | 362 | 519 | 503 | 742 | 2,126 |

| Wave 5 (2006) | 686 | 594 | 613 | 745 | 2,638 |

| Wave 6 (2007) | 539 | 556 | 523 | 711 | 2,329 |

| Wave 7 (2008) | 142 | 320 | 370 | 382 | 1,196 |

Notes: Percentages were based on unweighted data. For some variables the number of cases were fewer than the total, due to some “don’t know” and “missing” cases.

For the definition of each category please see the Measures section.

Measures

The ITC-4 Survey included questions about smoking behaviour, cigarette brand information, quit history, exposure to anti-tobacco advertising, psychosocial measures, and demographics.

Outcome measures

The key outcomes were interest in quitting and quit attempts. Interest in quitting was assessed by: ‘Are you planning to quit smoking?’ Response options were ‘within the next month’, ‘within the next 6 months’, ‘sometime in the future, beyond 6 months’, ‘not planning to quit’, and ‘don’t know’. The first three categories were recoded to ‘having some interest in quitting’, and the remaining as ‘not having an interest’. Quit attempts were assessed at the next wave based on the answer to, ‘Since we last talked to you [in last survey date], have you made any attempts to stop smoking?’, or if a respondent stated that s/he had quit smoking since the previous survey date.

Measures of exposure to POS health warnings

Respondents were asked at each wave about their noticing of anti-smoking cues in a range of specific locations or media, such as on television, radio, posters or billboards. In this context the following question regarding POS anti-smoking warnings was asked: ‘In the last 6 months, have you noticed advertising or information that talks about the dangers of smoking, or encourages quitting, on store windows or inside stores where tobacco is sold?’ Those who answered ‘yes’ to this question were regarded as having been exposed to POS warnings.

Covariates

A compound measure of exposure to anti-smoking warnings in places other than at the POS was created from the following eight items: exposure on television, radio, movies, posters/billboards, newspapers/magazines, cigarette packs, leaflets, and the Internet (scores from 0-8). In addition, a measure of overall salience of anti-smoking information was used based on the following question: ‘In the last 6 months how often, if at all, have you noticed anti-smoking information?’ (1- never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often, 5-very often).

Demographics measured included sex (male, female), age at recruitment (18-24, 25-39, 40-54, 55 and older), and identified majority/minority group, which was based on the primary means of identifying minorities in each country (i.e., racial/ethnic group in the UK, Canada, and the US; and English language spoken at home in Australia). Due to the differences in economic development and educational systems across countries, only relative levels of income and education were used. ‘Low’ level of education referred to those who completed high school or less in Canada, the US, and Australia, or secondary/vocational or less in the UK; ‘moderate’ meant community college/trade/technical school/some university (no degree) in Canada and the US, college/university (no degree) in the UK, or technical/trade/some university (no degree) in Australia; and ‘high’ referred to those who completed university or postgraduate studies in all countries. Household income was also grouped into ‘low’ (less than $ 30,000 (country-specific dollars) (£ 30,000 in the UK) per year), ‘moderate’ ($ 30,000 to $ 59,999 (£ 30,000 to £ 44,999 in the UK)), and ‘high’ categories (equal to or greater than $ 60,000 (£ 45,000 in the UK)).

Cigarettes per day (CPD) was asked at each wave and recoded to: ‘already quit’, ‘1-10 CPD’, ‘11-20 CPD’, and ‘21+CPD’. Respondents were also asked at each wave about their endorsement for regulation of tobacco products via the following statement: ‘Tobacco products should be more tightly regulated’. Response options were ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’, or ‘strongly disagree’.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata Version 10.1. Both bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to examine (1) the association between reported exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings and smokers‘ interest in quitting in the same wave (ie, cross-sectional association), and (2) the association between POS exposure and subsequent quit attempts (ie, longitudinal association, in which quit attempts were measured one wave after the exposure to POS warnings). We first used chi-square tests to look at the unadjusted association between POS exposure and quit interest/attempts for each wave, and then used multivariate analyses to look at the fully adjusted association while considering data from all waves.

Taking into consideration the correlated nature of the data within persons and across survey waves, we used the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach to compute parameter estimates. All GEE models included a specification for an unstructured within-subject correlation structure, and parameter estimates were computed using robust variance. Our large sample size allowed us to assume an unstructured correlation structure in GEE which helped us to estimate all possible correlations between within-subject responses and included them in the estimation of the variances. Both main outcomes were dichotomous, so the GEE models included a specification for the binomial distribution of the dependent variables. For the outcome of quit attempts a ‘forward’ specification was used in the analysis so longitudinal association was examined. In GEE modelling we first explored the country effect and its interactions for both outcome variables. Because country effect and its interaction were significant, we constructed separate GEE models for each country. In each of the models we included the following covariates: age, sex, ethnicity, baseline education, baseline income, and also the following time-varying covariates reported at each wave: endorsement of regulation for tobacco products, overall salience of anti-smoking information, reported exposure to anti-smoking warnings in eight places other than POS, and cigarettes per day.

RESULTS

Reported exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings by wave and country

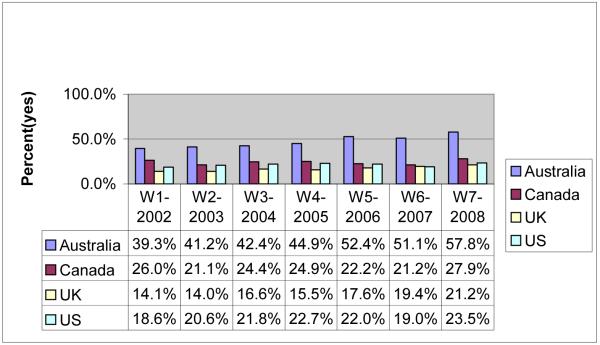

Figure 2 shows that smokers in Australia reported higher levels of noticing POS anti-smoking warnings compared to their counterparts in the other three countries, and this was consistent over time. It is also notable that the reported exposure to POS warnings in Australia increased over waves. There was also a smaller increase in the UK, but no clear evidence of an increase in either Canada or the US.

Figure 2.

Noticing POS anti-smoking warnings in shops by wave in ITC-4 countries

(Notes: ‘W1’ means ‘Wave 1’ of the Survey. This applies to the other waves. Proportions reported here were based on weighted data. A significant linear trend over years/waves was found in Australia, but not in the other 3 countries).

Interest in quitting and quit attempts by wave

Table 2 provides the reported quitting interest and attempts over waves in each of the four countries. It can be seen that the proportions of reported interest in quitting were generally higher than those of quit attempts in all the countries. Those who were exposed to POS anti-smoking warnings were more likely to report having quitting interest in Australia, but this was not the case in the other three countries. Similar results were found for quit attempts with a positive effect in Australia and no clear pattern in the other three countries, although the pattern of significant results by year in Australia was less clear than for quitting interest (Table 2).

Table 2. Reported interest in quitting and quit attempts over time, by country and exposure status to POS anti-smoking warnings.

| Wave1 (2002) | Wave2 (2003) | Wave3 (2004) | Wave4 (2005) | Wave5 (2006) | Wave6 (2007) | Wave7 (2008) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | exposed | not exp | |

| Australia -% Intended# | 76.9 | 75.3 | 75.6 | 72.3 | 77.5** | 72.2 | 77.8** | 70.9 | 76.7** | 69.8 | 77.6*** | 68.6 | 71.7** | 64.9 |

| %Attempted## | 34.6 | 34.1 | 47.4* | 41.9 | 50.4** | 41.9 | 50.6 | 47.5 | 46.1 | 46.7 | 49.6 | 49.1 | “-“ | “-“ |

| Canada - % Intended | 82.3 | 81.1 | 80.3 | 80.7 | 74.9 | 77.2 | 75.8 | 76.2 | 74.4 | 75.1 | 78.6 | 74.5 | 74.8 | 72.9 |

| %Attempted | 45.8 | 43.2 | 46.5 | 43.9 | 43.0 | 42.9 | 43.4 | 42.8 | 41.9 | 42.6 | 45.5 | 46.9 | “-“ | “-“ |

| UK - % Intended | 59.0 | 65.5* | 54.3 | 61.3* | 58.0 | 63.0 | 66.9 | 63.9 | 79.9** | 60.1 | 61.5 | 56.7 | 62.6* | 57.9 |

| %Attempted | 30.2 | 31.8 | 34.3 | 38.3 | 44.1 | 44.9 | 39.0 | 41.1 | 40.5 | 41.3 | 40.0 | 40.8 | “-“ | “-“ |

| US - % Intended | 71.4 | 75.6 | 68.4 | 72.0 | 69.0 | 69.2 | 64.2 | 69.9* | 71.2 | 71.2 | 71.8 | 69.6 | 70.9 | 68.5 |

| %Attempted | 37.3 | 36.3 | 44.7 | 38.9 | 47.2 | 41.1 | 43.4 | 40.3 | 41.6 | 44.7 | 48.1 | 46.1 | “-“ | “-“ |

Notes:

Percent of participants who reported having some intention to quit. Exposure and interest in quitting variables were from same wave (ie, cross-sectional association).

Percent of participants who reported having made at least 1 quit attempt between two consecutive surveys. Quit attempts occurred in the next wave/s after exposure (ie, longitudinal association).

stands for “not applicable”, because the Wave 8 attempt data were not available at the time of writing.

Differences were significant at p<0.05, Pearson chi-square test (exposed vs not exposed, a * is placed next to the higher figure)

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Associations between exposure to POS warnings and quitting interest and attempts: GEE modelling results

GEE modelling results show that over the waves in Australia (but not in the other three countries) there was a significantly positive association between exposure to POS warnings and quitting interest (adjusted odds ratio = 1.139, 95% CI 1.039~1.249, p<0.01), in that those who were exposed to POS warnings were 13.9% more likely at the same wave to report having quitting interest than those who were not exposed (Table 3). Similarly, in Australia those who were exposed to POS warnings at one wave were 21.6% more likely to report having made quit attempts at the next wave than those who were not exposed (adjusted odds ratio = 1.216, 95% CI 1.114~1.327, p<0.001, Table 4). No significant association between exposure to POS warnings and outcomes was found in the other three countries.

Table 3. Association between exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings and interest in quitting – GEE modelling results.

| Adjusted Odds Ratio^ |

95% CI | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||

| -POS warnings | 1.139 | 1.039~1.249 | <.01 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.065 | 1.034~1.097 | <.001 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.090 | 1.052~1.129 | <.001 |

| Canada | |||

| -POS warnings | .919 | .826~1.022 | .122 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.096 | 1.064~1.129 | <.001 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.035 | .997~1.075 | .071 |

| UK | |||

| -POS warnings | 1.014 | .908~1.132 | .806 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.072 | 1.044~1.101 | <.001 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.063 | 1.031~1.097 | <.001 |

| US | |||

| -POS warnings | .911 | .825~1.007 | .069 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.065 | 1.037~1.094 | <.001 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.083 | 1.045~1.121 | <.001 |

Notes: Exposure and intention variables were from same wave (ie, cross-sectional association). Exposure to POS health warnings was coded as ‘1’ for ‘yes exposed’, and ‘0’ for ‘not exposed’ (the referent). Main effect (not shown in table) for country and its interaction (exposure*country) was significant at p<.001 level, therefore separate models were constructed for each country.

Adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, baseline education, baseline income, endorsement for regulation of tobacco products at each wave, a compound measure of exposure to anti-smoking warnings in places other than POS, overall salience of anti-smoking information, cigarettes per day at each wave, wave and cohort.

Table 4. Longitudinal association between exposure to POS anti-smoking warnings and subsequent quit attempts– GEE modelling results.

| Adjusted Odds Ratio^ |

95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||

| -POS warnings | 1.216 | 1.114~1.327 | <.001 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

.995 | .968~1.023 | .718 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.042 | 1.006~1.079 | .023 |

| Canada | |||

| -POS warnings | .909 | .820~1.007 | .067 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.011 | .983~1.039 | .450 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

.997 | .961~1.034 | .854 |

| UK | |||

| -POS warnings | .949 | .835~1.079 | .425 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.005 | .976~1.035 | .738 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

1.062 | 1.025~1.100 | .001 |

| US | |||

| -POS warnings | .987 | .900~1.082 | .774 |

| -Seen in other health warning domains (number) |

1.022 | .997~1.048 | .081 |

| -Overall salience of anti- smoking information |

.959 | .928~.992 | .016 |

Notes: Exposure to POS health warnings was coded as ‘1’ for ‘yes exposed’, and ‘0’ for ‘not exposed’ (the referent). “Having made quit attempts” were measured one wave AFTER the exposure to POS warning, and a ‘forward’ specification was used in the analysis. Main effect (not shown in table) for country and its interaction (exposure*country) was significant at p<.001 level, therefore separate models were constructed for each country.

Adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, baseline education, baseline income, endorsement for regulations of tobacco products at each wave, a compound measure of exposure to anti-smoking warnings in places other than POS, overall salience of anti-smoking information, cigarettes per day at each wave, wave and cohort. When interest in quitting was also adjusted for the effect remained essentially the same for each country, including the significant effect in Australia.

DISCUSSION

Point-of-sale anti-smoking warnings are designed to warn of the dangers of smoking and encourage smokers to quit. This study clearly shows that the stronger, larger Australian POS warnings are noticed and are associated with increased interest in quitting and prospectively with quit attempts for smokers in Australia. However, the weaker, or non-existent warnings in the other countries appear to have no measurable effects. In Australia, the positive association between exposure to POS warnings and outcomes remained even when exposure to anti-smoking warnings in other domains and overall salience of anti-smoking information were controlled for.

The findings raise two important questions. First, does only finding a relation with quitting in Australia suggest some threshold effect, and second, how likely is it that the relation we found for quitting are causal? The Australian warnings are required to be placed in prime POS positions – they are not incidental to signs promoting or announcing tobacco sales, and they clearly promote the Quitline number. They are typically at least A4 in size and black on white text, although there is variation between states (12). The small state of Tasmania now mandates coloured graphic warnings using the same images as are on the cigarette pack warnings (20)), but the sample size is too small and the introduction too recent to be able to test for an independent effect of these warnings. The data are clearly consistent with some threshold of exposure, that is related to warning message design and position. However, the failure to find any evidence of effects of the newly introduced POS anti-smoking warnings in some Canadian provinces weakens the argument for a threshold effect, and is more consistent with between-country differences. It is also consistent with their warnings not evoking the broader anti-smoking efforts as Australia warnings do. In other studies of the ITC-4 cohort, we have not found between-country effects for the impact of health warnings on cigarette packs (14), even though in the US they are far smaller and less prominent than in the other countries. One possibility for this pattern of findings is that pack warnings are available to smokers all the time, and smokers are prone to notice them from time to time, even when they are tucked away on the side of the pack. By contrast, little time is spent in stores, so they need to be prominent enough to be noticed with some regularity to have any real effect. This suggests that POS warnings should be designed and placed in such a way that they are large and prominent enough to be noticed.

One unique and relevant aspect of Australia’s tobacco control programme is its comprehensiveness. It has integrated communications from mass-media campaigns, pack warnings and POS warnings. Recent research into the different measures designed to reduce smoking rates in Australia found that increases in tobacco taxes and greater exposure to televised mass media campaigns contributed to the decreased smoking prevalence among Australian adults (21), and this is consistent with international evidence showing that strong disease-related messages are potent motivators of making quit attempts (8). The overall broad and multi-location strategy of using the same prominent warnings on the cigarette packs and at POS, as well as via mass media would likely provide additional opportunities for smokers to remember the warnings and this, in turn, might lead to an increase in the likelihood that the warnings would lead to action. Our data indicate that overall salience of anti-smoking information was associated with interest in quitting in all countries but Canada (for reasons that are unclear) and quit attempts in Australia and the UK. A recent study by Brennan et al (2011) found that graphic health warnings on cigarette packets and on television operated in a complementary manner to positively influence Australian smokers’ awareness of the health risks of smoking and motivation to quit (13), suggesting that such a multi-location strategy may enhance effects. It is worth reflecting on the fact that in most jurisdictions where POS is critical for tobacco marketing, the POS pack displays have traditionally served as a prompt for smokers to purchase tobacco rather than avoid it, and to pose a risk for relapse for those who have quit (22, 23).

Although some weak effect of POS exposure on interest in quitting was identified (in bivariate analysis) in a couple of waves (ie, Waves 5, 7) in the UK, overall the relation between POS warning exposure and quit interest/attempts in other three countries (ie, Canada, the US and UK) was not significant or consistent. As these countries have also strengthened POS regulations governing tobacco display/health warnings more recently, it will be interesting for future research to use the upcoming ITC-4 survey data to further assess their impacts on cessation.

This study has some strengths and weaknesses. One of the main strengths is its longitudinal design, which allowed for changes in exposure and outcomes over time to be assessed for the outcome of quit attempts, especially using GEE modelling which allowed us to combine respondents from all waves while accounting for inherent within-person correlation, thereby increasing our sample size and power to detect effects. This study covered a seven year period, providing unique and rich information to examine the association between POS anti-smoking warnings and smokers’ interest in quitting and their subsequent quit attempts. Our use of nationally representative samples of smokers and essentially identical measures and parallel data collection methods across all four countries (18, 24) strengthened the validity of conclusions about the similarities or differences of the impact of POS warnings.

This study did not examine the nuances of enactment/implementation differences between states/provinces within the countries. The sub-national differences might be important, and should be explored in future research. The study relies on self-reports of exposure to anti-smoking warnings and it is possible that sensitivity to warnings, rather than their actual presence in the person’s environment might be more important. Thus smokers more interested in quitting might be noticing the warnings more and then these are the smokers who go on to make more quit attempts, making the results an artefact. We think this is unlikely as we controlled for interest in quitting in the analyses of quit attempts, and this explanation cannot account for the effects only being present in Australia. Respondents’ recall might be imprecise, especially when a long period of time (eg, 6 months or 1 year) was involved, and they could be affected by external factors such as amount of competing material in the environment. However, there is no evidence to suggest that self-report is systematically inaccurate in population-based studies of this kind. The important point here is to exercise caution when making inference about differences across the countries.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that the effects of POS anti-smoking warnings on interest in quitting and quit attempts were not homogenous across the four western countries, and that greater exposure to POS warnings was positively associated with increased interest in quitting and quit attempts only for smokers in Australia over time. The results support the use of more prominent, comprehensive and consistent anti-smoking warnings at the POS, especially if they are employed in multiple locations and multiple channels as has been done in Australia. Doing so should encourage more smokers to take action to quit.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards or research ethics boards of the University of Waterloo (Canada), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (USA), University of Strathclyde (UK), University of Stirling (UK), The Open University (UK), and The Cancer Council Victoria (Australia).

What this paper adds.

This study has demonstrated that reported exposure to prominent anti-smoking warnings at the point-of-sale was associated with increased interest in quitting and quit attempts among adult smokers. This pattern of results was found in Australia, but not in three other countries, which had no or weaker rules for the display of anti-smoking warnings. It provides support for initiatives to strengthen point-of-sale anti-smoking warnings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank other members of the ITC Four Country Survey team for their support. We would also like to thank Jessica Longbottom of Cancer Council Victoria and Karima Ladhani of University of Waterloo for helping obtain some point-of-sale policies and relevant materials. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors who provided useful suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper.

Declaration of interest: The research reported in this paper was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute of the United States (P50 CA111326, P01 CA138389, and R01 CA100362), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (57897 and 79551), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903 and 450110), Cancer Research UK (C312/A3726), Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (014578), and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, with additional support from the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, Canadian Cancer Society, and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. Sara C. Hitchman receives additional funding from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Doctoral Research Award. The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None identified.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saffer H. Tobacco Advertising and Promotion. In: Jha P, Chaploupka F, editors. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press, Inc.; Oxford: 2000. pp. 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitanondh H. Thailand country report on tobacco advertising and promotion bans. In: Tobacco control, editor. WHO tobacco control papers. University of California; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris F, MacKintosh AM, Anderson S, Hastings G, Borland R, Fong GT, et al. Effects of the 2003 advertising/promotion ban in the United Kingdom on awareness of tobacco marketing: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl_3):iii26–33. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman S, Wakefield M. Tobacco control advocacy in Australia: Reflections on 30 years of progress. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28:274. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paynter J, Edwards R, Schluter P, McDuff I. Point of sale tobacco displays and smoking among 14 15 years olds in New Zealand: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control. 2009;18:268–274. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Yong H-H, Borland R, Fong GT, Thompson ME, Jiang Y, et al. Reported awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China compared to Thailand, Australia and the USA. Tob Control. 2009;18(3):222–227. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute . Tobacco control monograph No.19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2008. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use; pp. 211–281. NIH Pub. No. 07-6242, June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Trade Commission . Cigarette Report for 2004 and 2005. Federal Trade Commission; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.New South Wales Parliamentary Counsel’s Office [Accessed 3 March 2011];Public Health (Tobacco) Regulation. 1999 Available at: http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/xref/inforce/?xref=Type%3Dsubordleg%20AND%20Year%3D1999%20AND%20No%3D468&nohits=y. archived by Webcite at http://www.webcitation.org/617U6kZoP)

- 11.Victorian Government Department of Human Services . Tobacco Retailer Guide. Melbourne: [Accessed 18 January 2011]. 2006. Available at: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/tobaccoreforms/downloads/retailers_guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman B, Chapman S. 11.4. State and territory legislation. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. 3rd ed ed. Melbourne: [Accessed 17 February 2011]. 2011. Available at: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-11-advertising/11-4-state-and-territory-legislation. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan E, Durkin S, Cotter T, Harper T, Wakefield MA. Mass media campaigns designed to support new pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets: Evidence of a complementary relationship. Tobacco Control. 2011 doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039321. published Online first on 7 April 2011, doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong G, Hammond D, Cummings K, Yong H, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: Findings from four countries over five years. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:358–364. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Government of Ontario [Accessed 28 July 2009];Smoke-Free Ontario Act. 2006 available at: http://www.cctc.ca/cctc/EN/lawandtobacco/byregion/on/smoke-free_ontario_act. archived by Webcite at http://www.webcitation.org/617UXBJVT.

- 16.Government of Quebec Tobacco Act. 2010 available at: http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=2&file=/T_0_01/T0_01_A.html. Accessed 28 February 2010; archived by Webcite at: http://www.webcitation.org/617Ujc4KN.

- 17.Government of the UK . The Tobacco Advertising and Promotion (Point of Sale) Regulations 2004. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii3–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Driezen P, Hyland A, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii12–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bicevskis M. [Accessed 28 July 2010];Graphic point-of-display tobacco health warnings in Tasmania: Expected and unexpected benefits. 2006 Available from: http://2006.confex.com/uicc/wctoh/techprogram/P5024.HTM. archived by Webcite at: http://2006.confex.com/uicc/wctoh/techprogram/P5024.HTM. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakefield M, Durkin S, Spittal M. Impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on monthly adult smoking prevalence. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Germain D, McCarthy M, Wakefield M. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiciton. 2009;105:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiciton. 2008;103(2):322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IARC . IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention: Tobacco Control. Volume 12. Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2008. [Google Scholar]