Abstract

Genome-wide association studies have identified 32 loci associated with body mass index (BMI), a measure that does not allow distinguishing lean from fat mass. To identify adiposity loci, we meta-analyzed associations between ~2.5 million SNPs and body fat percentage from 36,626 individuals, and followed up the 14 most significant (P<10−6) independent loci in 39,576 individuals. We confirmed the previously established adiposity locus in FTO (P=3×10−26), and identified two new loci associated with body fat percentage, one near IRS1 (P=4×10−11) and one near SPRY2 (P=3×10−8). Both loci harbour genes with a potential link to adipocyte physiology, of which the locus near IRS1 shows an intriguing association pattern. The body-fat-decreasing allele associates with decreased IRS1 expression and with an impaired metabolic profile, including decreased subcutaneous-to-visceral fat ratio, increased insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, risk of diabetes and coronary artery disease, and decreased adiponectin levels. Our findings provide new insights into adiposity and insulin resistance.

Adiposity is a key risk factor for a number of common metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease1. Although the recent global increase in adiposity has been driven by lifestyle changes, family and twin studies suggest that there is also a substantial genetic component contributing to inter-individual variation in adiposity2. The specific loci accounting for this variation remain largely unknown.

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 32 common loci associated with body mass index (BMI)3-8 - the most commonly used index of adiposity and the diagnostic criterion for overweight and obesity1. These loci, however, account only for a small fraction of the variation in BMI8. Although BMI is generally a good indicator of adiposity and disease risk, it does not allow distinguishing between lean and fat body mass. Using body fat percentage, a more accurate measure of body composition, may identify new loci more directly associated with adiposity. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of 15 GWAS of body fat percentage, including altogether 36,626 individuals of white European (n=29,069) and Indian-Asian (n=7,557) descent, and followed-up the most significant findings in up to 39,576 European individuals.

RESULTS

Stage 1 genome-wide association meta-analysis of body fat percentage

We first performed a meta-analysis for the associations of body fat percentage with ~2.5 million genotyped or imputed SNPs from 15 studies, including up to 36,626 individuals of white European (n=29,069) and Indian-Asian (n=7,557) descent (Online Methods, Supplementary Figure 1). To identify genetic loci that may associate with body fat percentage in European individuals only, we performed an additional meta-analysis of individuals of European descent. Furthermore, meta-analyses were also performed in men (nEuropean=13,281; nIndian-Asian=6,535) and women (nEuropean=15,789; nIndian-Asian=1,022) separately to identify sex-specific associations with body fat percentage. Genetic variants in the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene and near the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) gene showed genome-wide significance (P<5×10−8) at this stage (Table 1, Figure 1). To confirm the loci near-IRS1 and FTO loci and to identify more adiposity loci, we took forward 14 SNPs representing the 14 most significant and independent loci for which association with body fat percentage reached a significance of P<10−6 in all individuals combined, in Europeans, in men, or in women (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 2). Loci were considered independent when they were in low linkage disequilibrium (r2<0.3) or were >1 Mb apart.

Table 1.

Stage 1 and stage 2 results of the SNPs near the IRS1, near the SPRY2 and in the FTO gene that were associated with body fat percentage at genome-wide significant (P < 5 × 10−8) levels

| Per allele change in body fat % βa |

Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1+2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus | Meta-analysis | Frequency effect allele |

Explained variance (%) |

N | P | N | P | N | P | |

| rs2943650 (near IRS1) Chr2: 226,814,165 bp Effect allele: T |

All individuals | 64 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 36,574 | 7.9×10−9 | 39,576 | 1.9×10−4 | 76,150 | 3.8×10−11 |

| Europeans | 64 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 29,017 | 3.1×10−6 | 39,576 | 1.9×10−4 | 68,593 | 6.0×10−9 | |

| Indian-Asians | 69 | NA | NA | 7,557 | 2.7×10−4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Men | 64 | −0.20 | 0.06 | 19,751 | 4.1×10−8 | 24,047 | 3.4×10−5 | 43,798 | 2.9×10−11 | |

| European men | 63 | −0.20 | 0.06 | 13,216 | 4.1×10−6 | 24,047 | 3.4×10−5 | 37,263 | 1.8×10−9 | |

| Women | 64 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 16,823 | 0.0027 | 15,529 | 0.47 | 32,352 | 9.0×10−3 | |

| European women | 63 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 15,801 | 0.012 | 15,529 | 0.47 | 31,330 | 0.024 | |

| rs534870 (nearSPRY2) Chr13: 79,857,208 bp Effect allele: A |

All individuals | 68 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 36,488 | 3.2×10−6 | 34,342 | 2.6×10−3 | 70,831 | 6.5×10−8 |

| Europeans | 70 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 28,931 | 7.9×10−7 | 34,342 | 2.6×10−3 | 63,273 | 3.2×10−8 | |

| Indian-Asians | 68 | NA | NA | 7,557 | 0.52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Men | 68 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 19,726 | 0.0016 | 20,537 | 2.1×10−3 | 40,263 | 1.1×10−5 | |

| European men | 69 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 13,190 | 8.6×10−5 | 20,537 | 2.1×10−3 | 33,727 | 1.6×10−6 | |

| Women | 69 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 16,763 | 9.0×10−4 | 13,805 | 0.34 | 30,568 | 2.2×10−3 | |

| European women | 69 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 15,741 | 0.0027 | 13,805 | 0.34 | 29,546 | 0.0048 | |

| rs8050136 (FTO) Chr16: 52,373,776 bp Effect allele: C |

All individuals | 60 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 36,537 | 3.9×10−17 | 34,105 | 4.4×10−11 | 70,642 | 2.7×10−26 |

| Europeans | 59 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 28,980 | 4.6×10−16 | 34,105 | 4.4×10−11 | 63,085 | 5.6×10−25 | |

| Indian-Asians | 68 | NA | NA | 7,557 | 0.011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Men | 60 | −0.29 | 0.10 | 19,739 | 2.5×10−8 | 20,624 | 6.0×10−7 | 40,363 | 1.3×10−13 | |

| European men | 59 | −0.29 | 0.10 | 13,204 | 2.1×10−7 | 20,624 | 6.0×10−7 | 33,828 | 1.7×10−12 | |

| Women | 60 | −0.39 | 0.13 | 16,798 | 1.2×10−8 | 13,481 | 1.6×10−5 | 30,279 | 1.1×10−12 | |

| European women | 59 | −0.39 | 0.13 | 15,776 | 2.2×10−8 | 13,481 | 1.6×10−5 | 29,257 | 2.7×10−12 | |

The effect allele for each locus is the body fat percentage decreasing (major) allele. Chromosomal positions are indicated according to Build 36 and allele coding based on the positive strand.

bp, base pairs; Chr, chromosome; NA, no individuals available for analysis.

Effect sizes in % obtained from stage 2 studies only which included only individuals of white European descent.

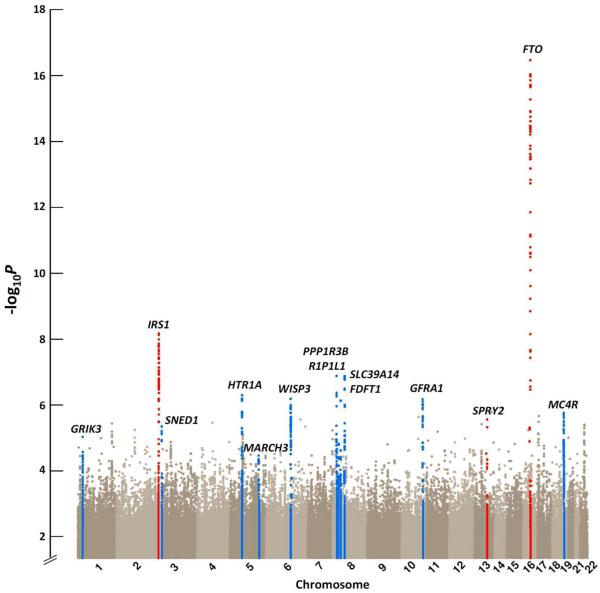

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot showing the significance of association with body fat percentage for all SNPs in the stage 1 meta-analysis of all individuals (n=36,626). SNPs are plotted on the x-axis according to their position on each chromosome against association with body fat percentage on the y-axis (shown as −log10 P-value). The loci highlighted in blue are the 11 loci that reached an association P value < 10−6 in the stage 1 meta-analysis of all individuals, Europeans, men, or women, and were taken forward for follow-up analyses, but did not achieve genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the meta-analyses combining GWAS and follow-up data. The three loci coloured in red are those that reached genome-wide significant association (P < 5 × 10−8) in the meta-analyses combining GWAS and follow-up data.

Stage 2 follow-up analyses identify three loci associated with body fat percentage

We examined the associations of the 14 SNPs with body fat percentage in up to 39,576 additional individuals of European descent from 11 studies (stage 2) (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 1). In a joint meta-analysis of stage 1 and stage 2 results, three of the 14 SNPs reached genome-wide significance (P<5×10−8) for association with body fat percentage (Table 1, Supplementary Table 3). We confirmed associations for the SNP in FTO (chr16: rs8050136; Pall=3×10−26) and for the SNP near IRS1 (chr2: rs2943650; Pall=4×10−11), which both reached genome-wide significance in stage 1 and identified a third locus near the sprouty homolog 2 (SPRY2) gene (chr 13: rs534870; PEuropeans =3×10−8 ). The near-SPRY2 locus showed association with body fat percentage only in white Europeans and not in Indian Asians, whereas the effect sizes for the near-IRS1 and in FTO loci were similar in meta-analyses of ‘Europeans only’ vs. ‘Europeans and Indian Asians combined’ (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). The association of the near-IRS1 SNP with body fat percentage was significantly (Psex-difference=0.02) more pronounced in men (P=3×10−11) than in women (P=9×10−3) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3). While FTO is a well-established adiposity gene3,5, the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci have not been previously implicated in adiposity. Therefore, we focused our follow-up analyses on the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci to estimate their impact on related metabolic traits and to gain insight into the potential functional roles of these two new adiposity loci.

Influence of genetic variation near IRS1 on anthropometric and related metabolic traits and its potential functional role

The rs2943650 SNP near IRS1 was associated with a 0.16% lower body fat percentage per copy of the major allele. The effect was stronger in men than in women (beta = 0.20% and 0.06% per allele, respectively). Interestingly, despite the highly significant associations with body fat percentage, we found no convincing evidence of association between the near-IRS1 SNP and BMI (Pall=0.32, Pmen=0.16, Pwomen=0.79) or other obesity-related traits (Supplementary Table 5). As BMI represents both fat and lean mass, whereas body fat percentage is a measure of the relative proportion of these two tissues, our observation suggests that the locus near IRS1 influences specifically adiposity, or alternatively, influences fat mass and lean body mass in opposite directions.

The rs2943650 SNP is located 500 kb upstream of the IRS1 gene, an important mediator of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling (Figure 2). Previous GWAS have identified SNPs near IRS1, in high LD with rs2943650 (r2>0.8 in the HapMap CEU population), to be associated with various metabolic traits9-11. Intriguingly, while we observed the major allele of rs2943650 to be associated with lower body fat percentage, prior work suggests that the major allele of rs2972146 (r2=0.95 with rs2943650) is associated with higher triglycerides and lower HDL cholesterol9, the major allele of rs2943641 (r2=1.00 with rs2943650) is associated with increased insulin resistance and risk of type 2 diabetes10, and the major allele of rs2943634 (r2=0.83 with rs2943650) is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease11.

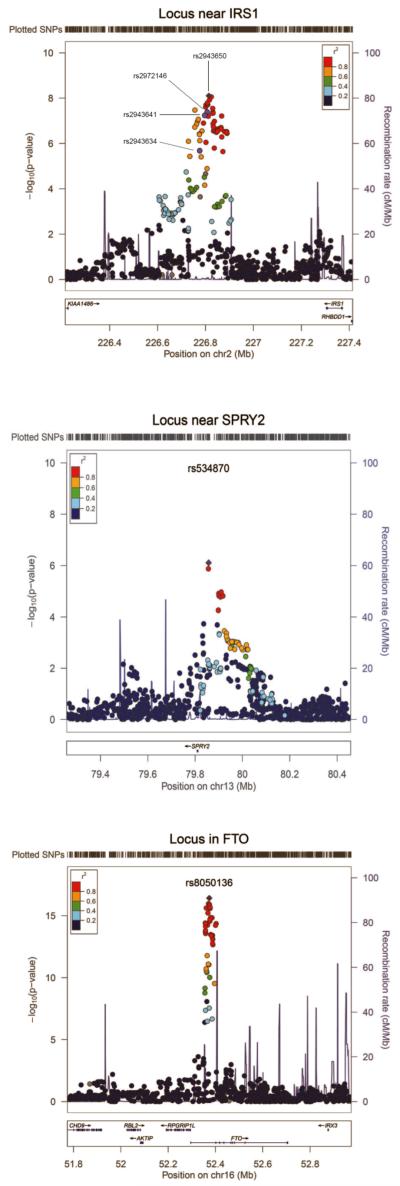

Figure 2.

Regional plot of the loci near IRS1, near SPRY2, and in FTO that reached genome-wide significant evidence for association with body fat percentage. The plotted data for the near-SPRY2 locus are from the meta-analysis of individuals of European descent only, and the data for the near-IRS1 and FTO loci are from the meta-analysis of all individuals. The rs2943650 (near-IRS1), rs534870 (near-SPRY2), and rs8050136 (FTO) SNPs which showed the strongest association with body fat percentage are indicated. For the near-IRS1 locus, the rs2972146, rs2943641, and rs2943634 SNPs, which have been associated with blood levels of HDL cholesterol and triglycerides9, risk of type 2 diabetes10 and risk of coronary artery disease11, respectively, in meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies are also indicated. The plot was generated using LocusZoom44 (see URLs).

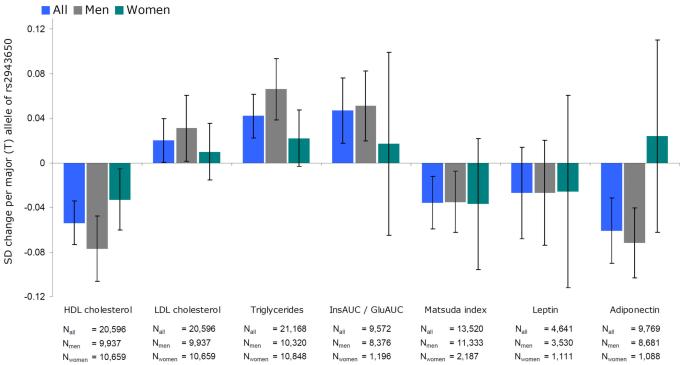

To better understand how genetic variation in the near-IRS1 locus is associated with both lower body fat percentage and a more adverse metabolic profile, we performed a series of focused follow-up analyses on the association of rs2943650 with lipid profiles, indices of insulin sensitivity, fat distribution, and circulating levels of leptin and adiponectin in the stage 2 studies that had all or some of these traits measured (Online Methods, Supplementary Figure 1). These analyses confirmed that the body fat percentage decreasing allele of rs2943650 is associated with higher triglycerides and lower HDL cholesterol levels, and with increased insulin resistance, as indicated by the increased ratio of insulin area under the curve (AUC) / glucose AUC, and decreased Matsuda12 and Gutt13 insulin sensitivity indexes (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 6). Consistent with the sex difference observed for the association of rs2943650 with body fat percentage, the associations with HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels were more pronounced in men (n=9,937 and n=10,659, respectively) than in women (n=10,659 and n=10,848, respectively) (for sex-differences P=0.027 and P=0.025, respectively) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 6) whereas associations with indices of insulin resistance were similar in both sexes.

Figure 3.

Association of the body fat percentage decreasing (T) allele of rs2943650 near IRS1 with blood lipids, insulin sensitivity traits, leptin and adiponectin. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. All traits were inverse normally transformed to approximate normality (mean = 0, sd = 1) in men and women separately. All models were adjusted for age and age squared. The numeric values for the associations are presented in Supplementary Table 6. A significant difference between men and women was found for the levels of HDL cholesterol (P = 0.027), triglycerides (P = 0.025), and adiponectin (P = 0.040). InsAUC / GluAUC, insulin area under the curve (AUC) / glucose AUC ratio.

To examine whether the association of the near-IRS1 locus with body fat percentage is mediated through association with insulin sensitivity, we carried out an analysis for body fat percentage adjusted for insulin sensitivity among 6,489 men of the METSIM (Metabolic Syndrome in Men) study (Supplementary Figure 3). Similarly, to examine whether the association of IRS1 with body fat percentage could explain association with insulin sensitivity, we carried out an analysis for insulin sensitivity adjusted for body fat percentage. While the effect size for the association of the rs2943650 (near IRS1) major allele with reduced body fat percentage did not significantly (Pdifference=0.38) change after adjusting for insulin sensitivity, the association with reduced insulin sensitivity became significantly stronger when we adjusted for body fat percentage (Pdifference=0.035). These observations suggest that the near-IRS1 locus may have a primary effect on body fat percentage and that the association with decreased insulin sensitivity is partly mediated by changes in body fat percentage, at least in men.

We next examined whether the concurrent association of the near-IRS1 locus with lower body fat percentage and an adverse metabolic profile could be due to joint associations with body fat distribution. Therefore, we determined associations of rs2943650 with abdominal visceral and subcutaneous fat obtained by computerized tomography in GWAS meta-analysis data of 10,557 individuals (personal communication with Caroline Fox). We found that the near-IRS1 locus was associated with an adverse distribution of body fat in men, i.e. the body fat percentage decreasing allele reduced subcutaneous fat in men (P=1.8×10−3, n=4,997) but not in women (P=0.063, n=5,560), whereas no association with visceral fat was observed in either men (P=0.95) or in women (P=0.63). Most evidently, the body fat decreasing allele of the locus near IRS1 was associated with a higher ratio of visceral adipose tissue to subcutaneous adipose tissue in men (P=6.1×10−6) but not in women (P=0.31). Our data thus suggest that the locus near IRS1 may associate with a reduced storage of subcutaneous fat in men, which could contribute to the associations of this locus with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia by leading to an ectopic deposition of lipids13.

Having demonstrated the association of the locus near IRS1 with the quantity and distribution of body fat and with related metabolic traits, we aimed to determine whether this locus is associated with measures of adipocyte function. Leptin and adiponectin are two hormones (adipokines) produced exclusively in adipose tissue, which respond in a reciprocal manner to changes in fat mass and insulin resistance. Higher levels of leptin and lower levels of adiponectin correlate with increased body fat and insulin resistance14. Leptin data was available for 4,641 individuals and adiponectin data for 9,769 individuals participating in our stage 2 meta-analysis (Online Methods, Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, the body fat percentage decreasing allele was associated with lower adiponectin levels in men (P=6.1×10−6, n=8,681), which is in contrast to what we expected given the inverse correlation between body fat percentage and adiponectin levels. No association with lower adiponectin levels was observed in women (n=1,088), which was significantly different from the association in men (Psex-difference=0.040) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 6). The association between the locus near IRS1 and leptin levels was not significant, which could be due to low statistical power as the size of the sample available was small (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 6). Intriguingly, recent studies in leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice have demonstrated that transgenic overexpression of adiponectin permits metabolically healthy expansion of subcutaneous adipose tissue, preventing accumulation of lipids in liver and retaining insulin sensitivity15. Vice versa, we speculate that the lower adiponectin levels, seen in men with the fat percentage decreasing allele of the near-IRS1 locus, might be associated with the lack of ability to expand subcutaneous adipose tissue, leading to a flux of lipids into liver and increased insulin resistance through a lipotoxic mechanism16.

To examine whether the rs2943650 SNP modifies the function of the IRS1 gene, we studied gene expression profiles within subcutaneous adipose tissue and blood from 604 Icelandic individuals (the deCODE cohort)6,17, within liver (n=567), subcutaneous (n=610) and omental (n=742) adipose tissue from patients who underwent bariatric surgery18, and within normal cortical brain samples of 193 individuals of European descent19 (Online Methods). We found that the body fat percentage decreasing allele is associated with lower IRS1 expression in subcutaneous and omental adipose tissue but not in liver, brain, or blood (Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Figure 4). The association with reduced expression in subcutaneous and omental adipose tissues seemed more pronounced in men than in women. Previous studies have shown that the body fat percentage decreasing allele of rs2943641 in the same locus (r2=1.0 with rs2943650) is associated with reduced expression of IRS-1 protein and reduced insulin-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase activity in skeletal muscle10.

Finally, to determine if there is a sex difference in the adipose tissue expression of the IRS1 gene, we analyzed gene expression in isolated adipocytes from male and female mice. The data showed that adipocytes from females express higher levels of IRS1 than adipocytes from males in both visceral and subcutaneous fat depots (Supplementary Figure 5). We followed up this finding in human adipose tissue, and found that the expression of IRS1 was significantly greater in visceral adipose tissue from women (n=75) than in visceral fat from men (n=26), whereas no sex difference in IRS1 expression was seen in subcutaneous adipose tissue (Supplementary Figure 6). The higher basal levels of IRS1 in female adipose tissue could, at least in theory, buffer women against the modest impairment of IRS1 expression associated with genetic variation near IRS1.

Influence of genetic variation near SPRY2 and its potential functional role

The rs534870 SNP which reached a P value of 3×10−8 in our meta-analysis of European individuals only is located 54 kb downstream of the SPRY2 gene with no other genes nearby (Figure 2). The body fat decreasing (i.e. major) allele of rs534870 was associated with 0.14% decrease in body fat percentage. Unlike for the near-IRS1 locus, the association was similar in men and women (Pdiff=0.62), and no association was observed in Indian Asians (Table 1). We found a modest association for rs534870 with BMI, body weight, and risk of obesity in a meta-analysis of all stage 2 studies (Supplementary Table 8). There was no association between near-SPRY2 and blood lipids, but we found a nominally significant association between the body fat percentage decreasing allele and increased insulin sensitivity measured with the Gutt insulin sensitivity index13 (Supplementary Table 8). The association with Gutt index was not significant after adjustment for body fat percentage (P=0.2). The body fat percentage decreasing allele of rs534870 was modestly associated with decreased SPRY2 expression in whole blood. In contrast with the near-IRS1 locus, there was no association between rs534870 and SPRY2 expression in adipose tissue, brain or liver (Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Figure 4).

SPRY2 encodes a negative feedback regulator of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway20. At the cellular level, overexpression of SPRY2 inhibits migration and proliferation of a variety of cell types in response to serum and growth factors21-23. Recent studies have identified SPRY1, a homolog of SPRY2, as a critical regulator of adipose tissue differentiation in mice24. The loss of SPRY1 function resulted in a low bone mass and high body fat phenotype.

Association of established BMI, waist circumference, and extreme obesity loci with body fat percentage

Previous GWAS have examined BMI as an index of adiposity3-8, and the recent meta-analysis by the GIANT (Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits) Consortium increased the total number of established BMI susceptibility loci to 328. The associations of the 32 confirmed BMI loci with body fat percentage were all directionally consistent with the previously established BMI associations (Binomial Sign Test P<0.0001), and associations for 17 of these loci reached nominal statistical significance (Supplementary Table 9). Our stage 1 sample size of 36,626 individuals was small compared to the GIANT stage 1 meta-analysis of BMI, which included 123,865 individuals, and we had thus insufficient power to confirm all 32 loci as body fat percentage loci. Furthermore, as BMI is a composite trait of fat and lean mass, BMI loci may associate with BMI by increasing fat mass, lean mass, or both. Disentangling whether the established BMI loci associate with body fat percentage per se or with body mass overall will require larger sample sizes.

Other GWAS have identified three loci associated with waist circumference25,26 and five loci associated with extreme obesity27,28. Similarly with BMI loci, the associations of these eight loci with body fat percentage were directionally consistent with the previously established associations (Binomial Sign Test P=0.008), and associations for one waist circumference locus and two extreme obesity loci reached nominal significance (Supplementary Table 9).

Apart from GWAS that examined traits related to overall adiposity, recent GWAS studies have identified 14 loci associated with waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for BMI26,29, a measure of body fat distribution. We found no association between these WHR loci and increased body fat percentage (Supplementary Table 9), which is consistent with the observation that these 14 loci are not or only very weakly associated with BMI and likely due to the fact that these loci were identified after accounting for BMI in the analyses.

DISCUSSION

Using a two-stage genome-wide association meta-analysis including up to 76,150 individuals, we identified three loci convincingly associated with body fat percentage. While FTO was previously established as an obesity-susceptibility locus3,5, the loci near IRS1 and near SPRY2 have not previously been identified in the large-scale genome-wide association studies for BMI8, waist circumference25,26, waist-to-hip ratio26,29 or extreme obesity27,28, suggesting that these loci have a specific association with body fat percentage.

The locus near IRS1 is associated with lower body fat percentage in men; more specifically with proportionally less subcutaneous compared to visceral fat. Of particular interest is the pattern of association with other metabolic traits which was opposite to what would be expected based on the known association between lower body fat percentage and improved metabolic profile. In effect, the fat percentage decreasing allele of the locus near IRS1 was associated with higher levels of insulin resistance, an adverse lipid profile and lower levels of adiponectin in men. Furthermore, the fat percentage decreasing alleles of SNPs in the locus near IRS1 have previously been associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes10 and coronary artery disease11.

We, and others10, demonstrated that genetic variation near IRS1 is associated with reduced IRS1 expression in major insulin target tissues, including adipose tissue and muscle, which may explain the association of this locus with increased whole-body insulin resistance and risk of type 2 diabetes. The locus near IRS1 is one of the few loci thought to increase risk of type 2 diabetes through an effect on insulin resistance, whereas other diabetes loci predominantly associate with measures of impaired beta-cell function10,30. However, the mechanisms linking the locus near IRS1 with type 2 diabetes may be more complex than previously thought. Our data suggest that genetic variation near IRS1 may be associated with a reduced ability to store subcutaneous fat, at least in men, which may partly explain the association with whole-body insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Adipose tissue insulin sensitivity itself has little impact on whole body insulin sensitivity, which is largely determined by the liver and muscle31. However, impaired ability of subcutaneous adipose tissue to expand may disrupt insulin signaling in liver and muscle by leading to ectopic deposition of lipids32. Such an indirect mechanism could exacerbate the intrinsic impairment of IRS-1 signaling in muscle.

The association of the near-IRS1 locus with body fat percentage and with many of the metabolic traits was more pronounced in men than in women. The mechanistic basis for this sexual dimorphism is yet unclear, but may be related to the powerful drive to subcutaneous adipogenesis in women compared to men, which may overcome a defect in IRS-1 function. Men tend to deposit less subcutaneous and more visceral fat than women33, and IRS-1 may thus have a stronger role in the regulation of subcutaneous fat in men. The association of the near-IRS1 locus with the expression of IRS1 in subcutaneous adipose tissue was more pronounced in men, indicating that there may be sex differences in the effects of the near-IRS1 locus on gene function itself. We also demonstrated a sex difference in both mouse and human adipose tissue expression of IRS1, with adipose tissue from females showing greater IRS1 expression.

IRS-1 function has been described in animal models. Knockout of IRS1 in mice leads to hyperinsulinemia and mild-to-moderate insulin resistance despite a lean phenotype34,35. IRS-236 and IRS-337,38 partly compensate for the lack of IRS-1. Knockout of IRS1 and IRS3 genes together leads to severe early-onset lipoatrophy with marked hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance39. The gene encoding IRS-3 is lacking in the humans, which may make humans more dependent on IRS-1. Data from cell lines of IRS1 knockout animals suggest that IRS1 is involved in adipocyte differentiation40,41. In IRS1 knockout mice, the ability of embryonic fibroblast cells to differentiate into adipocytes is reduced by 60%40. Cells of knockout mice for both IRS1 and IRS2 are completely unable to differentiate into adipocytes, and show a severe reduction in white adipose tissue soon after birth40.

Our second new locus for body fat percentage, near-SPRY2, showed association only in white Europeans, not in Indian Asians. Different from the near-IRS1 locus, the association between the body fat percentage decreasing allele of near-SPRY2 and insulin resistance was in the expected direction, i.e. this allele associated with higher insulin sensitivity and adjustment for body fat percentage attenuated the association. Similarly with near-IRS140,41, near-SPRY2 may play a role in the regulation of adipose tissue differentiation24. Different from the GWAS of BMI, which have mainly established loci mechanistically linked with central nervous system control of appetite and energy expenditure8, our meta-analysis of body fat percentage thus indicates that loci harboring genes with potential links with adipocyte physiology may also play important roles in the regulation of body adiposity.

Our stage 1 meta-analyses included individuals of European and of Indian Asian descent. The Indian Asian individuals were mainly of north Indian descent (‘Ancestral north Indians’, a western Eurasian population) and thus more closely related to Europeans, and, to a lesser extent, to Asians (‘Ancestral south Indians’)42. Furthermore, the overall body fat percentage of the Indian Asian sample did not differ from that of individuals of white European descent in our study. However, despite some similarities, genetic differences between European and Indian Asian populations remain, and as differences in body composition between both ethnicities have been documented43, we also performed a stage 1 GWAS in Europeans only. Exclusion of the Indian Asians did not affect the associations observed for the near-IRS1 locus, but it did for the near-SPRY2 locus. More specifically, the near-IRS1 locus was associated with body fat percentage in individuals of European and of Indian Asian descent at stage 1. The association for the near-SPRY2 locus, however, was only seen in Europeans, whereas no association was seen in Indian Asians. These observations illustrate the value of inclusion of the Indian Asian sample as stratified analyses allow inferring the ethnic-specificity of the identified loci.

In summary, we identified a locus near the IRS1 gene that is associated with reduced body fat percentage and adipose tissue IRS1 expression in men, but also with a combination of adverse metabolic and disease risk traits, including lower levels of subcutaneous fat, increased insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, decreased circulating levels of adiponectin, and increased risk of diabetes and coronary artery disease. Furthermore, genetic variation in a locus near SPRY2 associates with body fat percentage in individuals of European descent. Our findings provide new insights into adiposity and insulin resistance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A full list of Acknowledgements appears in the Supplementary Note.

Funding was provided by Academy of Finland (10404, 124243, 129680, 129494, 141005, and 213506); Agency for Health Care Policy Research (HS06516); ALF/LUA research grant in Gothenburg; Althingi (the Icelandic Parliament); American Heart Association (10SDG269004); AstraZeneca; Baltimore Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers; Biocentrum Helsinki Foundation; Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (G20234); British Heart Foundation (PG/07/133/24260, RG/08/008, SP/04/002, SP/07/007/23671); CamStrad; Cancer Research UK; Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors’ Chair in Medical Genetics; Centre for Medical Systems Biology (The Netherlands); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (Lausanne); Croatian Ministry of Science, Education and Sport (196-1962766-2747, 216-1080315-0302 and 309-0061194-2023); Department of Health (UK); Department of Veterans Affairs (US); Emil and Vera Cornell Foundation; Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam); Erasmus University (Rotterdam); European Commission (DG XII, FP7/2007-2013, FP7-KBBE-2010-4-266408, HEALTH-F2-2007-201681, HEALTH-F2-2008-201865-GEFOS, HEALTH-F4-2007-201413, HEALTH-F4-2007-201550, LSHG-CT-2006-018947, LSHG-CT-2006-01947, LSHM-CT-2003-503041, LSHM-CT-2004-512013, QLG1-CT-2001-01252 and QLG2-CT-2002-01254); Finnish Diabetes Foundation; Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Finnish Heart Foundation; Finnish Medical Society; Folkhälsan Research Foundation; Food Standards Agency (UK); Foundation for Life and Health in Finland; German Bündesministerium für Forschung und Technology (01AK803A-H and 01IG07015G); German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; German National Genome Research Network (NGFN-2 and NGFNPlus: 01GS0823); Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation; GlaxoSmithKline; Göteborg Medical Society; Gyllenberg Foundation; Health and Safety Executive (UK); Health Care Centers in Vasa, Närpes and Korsholm; Hjartavernd (the Icelandic Heart Association); John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation; Leenaards Foundation; Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München; Lundberg Foundation; Medical Research Council (UK); Men’s Associates of Hebrew SeniorLife; Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports (The Netherlands); Ministry of Education (Finland); Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (The Netherlands); Municipal Health Care Center and Hospital in Jakobstad; Municipality of Rotterdam; Närpes Health Care Foundation; National Institutes of Health (USA) (AG13196, DK063491, K23-DK080145, M01-RR00425, N01-AG12100, N01-AG62101, N01-AG62103, N01-AG62106, N01-HC15103, N01-HC25195, N01-HC35129, N01-HC45133, N01-HC55222, N01-HC75150, N01-HC85079 through N01-HC85086, P30-DK072488, R01-AG031890-01, R01-AG18728, R01-AG032098-01A1, R01-AR/AG41398, R01-AR046838, R01-DK06833603, R01-DK075787, R01-DK07568102, R01-HL036310-20A2, R01-HL087652, R01-HL08770003, R01-HL088119, U01-HL080295, U01-HL72515 and U01-HL84756); Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging (050-060-810); Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (175.010.2005.011 and 911-03-012); Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development; Nordic Center of Excellence in Disease Genetics; Novo Nordisk Foundation; Ollqvist Foundation; Paavo Nurmi Foundation; Perklén Foundation; Petrus and Augusta Hedlunds Foundation; Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2); Robert Dawson Evans Endowment; Royal Society (UK); Sahlgrenska Center for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Research (A305:188); Science Funding programme (UK); Scottish Executive Health Department; Sigrid Juselius Foundation; State of Bavaria; Stroke Association (UK); Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland; Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research; Swedish Research Council (K2010-54X-09894-19-3, K2010-52X-20229-05-3 and 2006-3832); Swedish Strategic Foundation; Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics; Swiss National Science Foundation (3100AO-116323/1, 310000-112552 and 33CSCO-122661); TEKES (1510/31/06); Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg’s Foundation; United Kingdom NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre; University of Lausanne; University of Maryland General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR 16500); Uppsala University; Västra Götaland Foundation; Wellcome Trust (077016/Z/05/Z, 084723/Z/08/Z and 091746/Z/10/Z)

APPENDIX

ONLINE METHODS

Study design

We designed a multi-stage study (Supplementary Figure 1) comprising a GWA meta-analysis for body fat percentage (stage 1) of data of up to 36,626 individuals of European (n=29,069) or Indian-Asian (n=7,557) descent from 15 studies, and selected 14 SNPs with P values <1×10−6 for follow-up in stage 2. Stage 2 comprised up to 34,556 additional European individuals from 11 studies. Body fat percentage in stage 1 and stage 2 cohorts was measured either with bioimpedance analysis or dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), as described in the Supplementary Note. To explore the comparability of the methods, we studied the correlation between body fat percentage obtained by DEXA and bioimpedance in the Fenland study (n=2,535), in which both measurements were taken at the same time point. The Fenland study is a population-based cohort of white European men and women between the age of 30-60 years (Supplementary Note - Table 3). The Pearson correlation co-efficient showed that the DEXA and bioimpedance measurements of body fat percentage are highly correlated (r=0.92). The correlation between body fat percentage with BMI was moderate (r=0.62 measured by DEXA and r=0.58 measured by BIA, respectively).

Meta-analysis of stage 1 and stage 2 summary statistics identified three loci that reached genome-wide significance (P<5×10−8) for the association with body fat percentage. Two of these loci (near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2) had not been previously identified in genome-wide association studies for BMI8, waist circumference25,26, waist-to-hip ratio26,29 or extreme obesity27,28. Subsequently, we performed a series of focused follow-up analyses (stage 3) to estimate the impact of these two new established body fat percentage loci and to explore their potential functional roles.

Stage 1 genome-wide association meta-analysis of body fat percentage

Genotyping

The 15 studies included in the stage 1 meta-analysis were genotyped using Affymetrix, Illumina, and Perlegen whole genome genotyping arrays (Supplementary Note). To allow for meta-analysis across different marker sets, imputation of polymorphic HapMap European CEU SNPs was performed using MACH45, IMPUTE46 or BIMBAM47 (Supplementary Note). Indian Asian genotype data in the Lolipop study was imputed using pooled haplotypes from all three HapMap populations (CEU, YRI, JPT+CHB). Imputation scores for the successful SNPs were slightly lower for Indian Asians than for Europeans. The Indian Asian GWAS of men genotyped with Illumina 610 K array had an average r2-hat of 0.942, whereas the GWAS from the GOOD study, genotyped with the same chip, had an average r2-hat of 0.956. In the Indian-Asian GWAS genotyped with the Perlegen array, average r2-hat was 0.751, whereas it was 0.851 in the European GWAS sample from the same study, genotyped with the same chip. In previously published data48, comparisons of imputed and experimentally derived genotypes in Indian-Asians yielded an estimated imputation error rate of 2.86% per allele and an estimated average r2 of 89.8%

Association analysis with body fat percentage

Each study performed single marker association analyses with body fat percentage using an additive genetic model implemented in MACH45, Merlin49, SNPTEST46 or Plink50. Body fat percentage was adjusted for age and age squared and inverse normally transformed to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Analyses were stratified by sex. To allow for relatedness in the Framingham Heart, Amish HAPI Heart, Family Heart, and Erasmus Rucphen studies, regression coefficients were estimated in the context of a variance component model that modeled relatedness in men and women combined with sex as a covariate. In the Twins UK study, only one twin was randomly selected for the analyses from monozygotic twin pairs, whereas from dizygotic twin pairs, both twins were used for the analyses. Association analyses accounted for the relatedness between dizygotic twin pairs.

Before performing meta-analyses on the genome-wide association data for the 15 studies, SNPs with poor imputation quality scores (r2-hat <0.3 in MACH, proper_info <0.4 in IMPUTE, or observed/expected dosage variance <0.3 in BIMBAM) were excluded for each study. All individual GWAS were genomic control corrected before meta-analysis. Individual study-specific genomic control values ranged from 0.979 to 1.052 (Supplementary Note).

Meta-analysis of stage 1 association results

Next, we performed the stage 1 meta-analyses using the inverse variance method, which is based on beta-coefficients and standard errors from each individual GWAS. The meta-analyses were performed for all individuals combined, for European individuals, for men, and for women using METAL (see URLs). The genomic control values for the meta-analysed results were 1.074, 1.065, 1.052 and 1.040 in all individuals, European individuals, men, and women, respectively (Supplementary Figure 7).

Selection of SNPs for follow-up

Fourteen SNPs, representing the 14 most significant (<1×10−6) independent loci in all individuals, Europeans, men, or women (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 2), were selected for replication analyses (stage 2). Loci were considered independent when they were in low LD (r2<0.3) or were >1 Mb apart. SNPs which had been genotyped in less than 50% of the samples and/or that had a minor allele frequency <0.5% were excluded. For some loci, the SNP with the strongest association could not be genotyped for technical reasons and was substituted by a proxy SNP that was in high LD with it (r2>0.8) according to the HapMap CEU data. We tested the association of these 14 SNPs in four de novo and seven in silico replication studies in stage 2.

Test for sex difference

The differences between the effect sizes in men and women for the strongest signals were assessed with a t-test with additional correction for the correlation between standard errors in men and women in the GWA data as follows: {t = (βmen − βwomen)/[(se2men + se2women) − 2corr(βmen − βwomen)semensewomen]}.

Stage 2 follow up of 14 most significant loci

Samples and genotyping

Directly genotyped data for the 14 SNPs was available from up to 22,485 adults of European ancestry from four studies (Supplementary Note). Samples and SNPs that did not meet the quality control criteria defined by each individual study were excluded. Minimum genotyping quality control criteria were defined as Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium P>10−6, call rate >90%, and concordance >99% in duplicate samples in each of the follow-up studies. Association results were also obtained for the 14 most significant SNPs from 10,713 individuals of European ancestry from seven GWAS that had not been included in the stage 1 analyses (Supplementary Note). Studies included between 719 and 3,132 individuals and were genotyped using Affymetrix and Illumina genome-wide genotyping arrays. Autosomal HapMap SNPs were imputed using either MACH45 or IMPUTE46. SNPs with poor imputation quality scores from the in silico studies (r2.hat <0.3 in MACH or proper_info <0.4 in IMPUTE) were excluded.

Association analyses and meta-analysis

We tested the association between the 14 SNPs and body fat percentage in each in silico and de novo stage 2 studies separately as described for the stage 1 studies. We subsequently performed a meta-analysis of beta-coefficients and standard errors from the stage 2 studies using the inverse variance method. Data was available for at least 31,705 individuals for 11 SNPs, except for three SNPs (rs17149412 in FDFT1, rs7736910 near HTR1A and rs7738021 near MARCH3), for which data was only available for ~24,400 individuals due to technical challenges relating to the genotyping and imputation of these SNPs. Next, we performed a meta-analysis of the summary statistics of the stage 1 and stage 2 meta-analyses using the inverse variance method in METAL. Differences in effect sizes between men and women were assessed as in stage 1.

Stage 3 follow-up of near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2

Association analyses of near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 with anthropometric traits, obesity, and overweight

The associations of the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci with BMI, body weight, height, risk of being obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), and risk of being overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) were tested in all stage 2 studies (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Note - Tables 4-8). Additional analyses for waist circumference, hip circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio were performed in three of the stage 2 studies (EPIC-Norfolk, Fenland, and MRC Ely) (Supplementary Figure 1). The associations of the SNPs with quantitative secondary traits (BMI, body weight, height, waist circumference, hip circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio) were tested with linear regression. The associations with overweight or obese status were assessed using logistic regression. All quantitative traits were analysed as non-transformed data. All tests assumed an additive genetic model and were stratified by sex, adjusting for age and age squared. Summary statistics (betas-coefficients and standard errors) were meta-analysed using the inverse variance method of METAL (see URLs).

Evidence for the association of the near-IRS1 locus with subcutaneous and visceral fat, obtained by computerized tomography from 10,557 individuals, was extracted from another GWAS meta-analysis (personal communication with Caroline Fox).

Association analyses of near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 with blood lipids

Associations of the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci with blood levels of HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol were examined in three of the stage 2 studies, including EPIC-Norfolk, Fenland, and MRC Ely (Supplementary Figure 1). In the EPIC-Norfolk Study, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides were measured from non-fasting blood whereas fasting blood samples were available in the MRC Ely and Fenland studies. The concentration of LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula in all three studies. The associations of the SNPs with lipid levels were tested with linear regression in men and women separately, assuming an additive genetic model and adjusting for age, age squared, and the use of lipid lowering medication. An inverse normal transformation for lipid levels was performed in men and women separately before the analyses. Summary statistics (beta-coefficients and standard errors) were pooled using the inverse variance meta-analysis method of METAL (see URLs).

Association analyses of near-IRS1 with insulin sensitivity traits

The associations of the near-IRS1 locus with insulin sensitivity traits [M/I ratio, i.e. glucose infused (M) derived by the circulating insulin concentration (I); insulin area under the curve (AUC) / glucose AUC ratio; Matsuda insulin sensitivity index12; Gutt insulin sensitivity index13) were examined in five studies (METSIM, MRC Ely, RISC, ULSAM, and Whitehall II), of which three (RISC, ULSAM, and Whitehall II) were not part of our stage 2 meta-analysis of body fat percentage (Supplementary Figure 1). The RISC and ULSAM studies had data from both euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps and oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT), whereas the METSIM, MRC Ely, and Whitehall II studies had OGTT data only. The M/I ratios were thus only available from the RISC and ULSAM studies, whereas the three other insulin sensitivity traits were available from all five cohorts. The samples and assays used for the measurement of circulating levels of glucose and insulin are shown in Supplementary Note - Table 9. Insulin AUC / Glucose AUC ratio and Matsuda and Gutt insulin sensitivity indexes were calculated using data from all available measurement time points. As the Whitehall II cohort had only two measurement time points available, the results from Whitehall II were not included in our meta-analysis of the association between the near IRS1 locus and insulin AUC / glucose AUC ratio.

Individuals were excluded from the analyses on insulin sensitivity traits if they had self-reported or physician diagnosed diabetes or were using oral antidiabetic drugs or insulin. The associations of the SNPs near IRS1 with insulin sensitivity traits were tested with linear regression in men and women separately, assuming an additive genetic model and adjusting for age and squared. All insulin sensitivity traits were inverse normally transformed in men and women separately before the analyses. Summary statistics (beta-coefficients and standard errors) were pooled using the inverse variance meta-analysis method of METAL (see URLs).

Association analyses of near-IRS1 with leptin and adiponectin

The associations of the near-IRS1 locus with circulating levels of adiponectin were examined in three studies participating in our stage 2 meta-analysis (METSIM, MRC Ely, MrOS Sweden) and in the RISC study (Supplementary Note - Tables 4-8). The samples and assays used for the measurement of leptin and adiponectin are listed in Supplementary Note - Table 9. The associations were tested using linear regression in men and women separately, assuming an additive genetic model and adjusting for age and age squared. Analyses on leptin levels in the MrOS Study were additionally adjusted for study centre. Leptin and adiponectin levels were inverse normal transformed in men and women separately before the analyses. Summary statistics (beta-coefficients and standard errors) were pooled with the inverse variance meta-analysis method of METAL (see URLs).

eQTL analyses for near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2

The gene expression analyses for the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci in subcutaneous adipose tissue and in whole blood from Icelandic individuals were carried out as described in detail previously (GEO database: GSE7965 and GPL3991)6,17. In brief, 603 individuals with adipose tissue samples and 745 blood samples were genotyped with the Illumina 317K or 370K chip. The RNA samples were hybridized to a single custom-made human array containing 23,720 unique oligonucleotide probes. Association was tested between the SNPs and the mean logarithm (log10) expression ratio (MLR) adjusting for age, sex, and age*sex, as well as differential cell count in the blood analyses, assuming an additive genetic model and accounting for familial relatedness.

The gene expression analyses for the near-IRS1 and near-SPRY2 loci in liver, subcutaneous and omental fat tissue from American patients who underwent bariatric surgery have been described in detail previously18. In brief, liver (n=567), subcutaneous (n=610) and omental (n=742) fat tissue were obtained. RNA was extracted and hybridized to a custom Agilent 44,000 feature microarray composed of 39,280 oligonucleotide probes targeting transcripts representing 34,266 known and predicted genes. All patients were genotyped on the Illumina 650Y SNP genotyping arrays. Cis-associations between each SNP and the adjusted gene expression data were tested with linear regression, adjusting for age, race, gender, and surgery year.

The eQTL analyses in cortical tissue have also been described in detail previously (GEO database: GSE8919)19. In brief, DNA and RNA of neuropathologically normal cortical brain samples of 193 individuals (mean age 81 years, range 65-100 years) of European descent were isolated. DNA was genotyped using the Affymetrix Gene-Chip Human Mapping 500K Array Set and genotypes were imputed using the data from the Phase II HapMap CEU population. RNA expression was assessed with the Illumina Human Refseq-8 Expression BeadChip system. Cis-association analyses assumed an additive model and were adjusted for sex and age at death.

Analyses for IRS1 expression in mouse adipocytes

Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment in groups of two to five at 22°C-24°C using a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Some cohorts were singly housed to measure food intake. The mice were fed standard chow (#2916, Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI) and water was provided ad libitum. Care of all animals and procedures were approved by the UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The fractionation of SV cells and adipocytes was performed as described previously51 with slight modifications. Briefly, SV cells were isolated from pooled white adipose depots [(inguinal, perigonadal, retroperitoneal, interscapular (the white adipose tissue juxtaposed to the interscapular brown adipose tissue)] that were explanted and minced into fine pieces (2-5mm2). The adipose pieces were then digested in adipocyte isolation buffer (100mM HEPES pH7.4, 120mM NaCl, 50mM KCl, 5mM glucose, 1mM CaCl2, 1.5% BSA) containing 1mg/ml collagenase at 37°C with constant slow shaking (~120rpm) for 2 hours. During the digestion period, the suspension was triturated several times through a pipet to dissociate the clumps. The suspension was then passed through an 80mm mesh to remove undigested clumps and debris. The effluent was centrifuged at 500xg for 10 minutes and the pellet washed once in 5ml PBS. To isolate floated adipocytes, the just-described collagenase-treated mixture was passed through a 210mm mesh, centrifuged at 500xg for 10 minutes and floated adipocytes collected from the top. Adipocyte gene expression was analyzed by qPCR.

Analyses for IRS1 expression in human adipose tissue

We analyzed 108 (from 29 men and 79 women) subcutaneous and 105 visceral (from 29 men and 76 women) adipose tissue samples from participants with a body mass index (BMI) within 20 and 68 kg/m2, who were recruited at the Endocrinology Service of the Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta (Girona, Spain). All subjects were of Caucasian origin and reported that their body weight had been stable for at least three months before the study. Individuals with liver and renal diseases were excluded. All subjects gave written informed consent. Adipose tissue samples were obtained from subcutaneous and visceral fat depots during elective surgical procedures (cholecystectomy, surgery of abdominal hernia and gastric by-pass surgery). All samples were washed, fragmented and immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storing at −80°C.

RNA was prepared from the adipose tissue samples using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (QIAgen, Izasa SA, Barcelona, Spain). The integrity of each RNA sample was checked by Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Total RNA was quantified by a spectrophotometer (GeneQuant, GE Health Care, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc., Madrid, Spain) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene expression was assessed by real time PCR using an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems Inc, Madrid, Spain) and TaqMan. The following commercially available and pre-validated TaqMan primer/probe sets were used: endogenous control PPIA (4333763, cyclophilin A, Applied Biosystems Inc., Madrid, Spain) and target gene Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 (IRS1, Hs00178563_m1, Applied Biosystems Inc, Madrid, Spain). The RT-PCR TaqMan reaction was performed in a final volume of 25μl. The cycle program consisted of an initial denaturing of 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 sec denaturizing phase at 95°C, and 1 min annealing and extension phase at 60°C. A threshold cycle (Ct value) was obtained for each amplification curve and a ΔCt value was first calculated by subtracting the Ct value for human Cyclophilin A (PPIA) RNA from the Ct value for each sample. Fold changes relative to the endogenous control were then determined by calculating 2−ΔCt. The gene expression results are thus expressed as an expression ratio relative to PPIA gene expression according to manufacturers’ guidelines.

Footnotes

URLs. LocusZoom44, http://csg.spg.umic.edu/locuszoom/METAL, http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/Metal/

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A full list of Author Contributions appears in the Supplementary Note.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare competing financial interests. A full list of competing interests appears in the Supplementary Note.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Technical Report Series. Vol. 894. WHO; Geneva: 2004. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maes HH, Neale MC, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet. 1997;27:325–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1025635913927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frayling TM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loos RJ, et al. Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat Genet. 2008;40:768–75. doi: 10.1038/ng.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scuteri A, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorleifsson G, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willer CJ, et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42:937–48. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teslovich TM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rung J, et al. Genetic variant near IRS1 is associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1110–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samani NJ, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutt M, et al. Validation of the insulin sensitivity index (ISI(0,120)): comparison with other measures. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;47:177–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badman MK, Flier JS. The adipocyte as an active participant in energy balance and metabolism. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2103–15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JY, et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2621–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI31021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. It’s not how fat you are, it’s what you do with it that counts. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emilsson V, et al. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature. 2008;452:423–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong H, Yang X, Kaplan LM, Molony C, Schadt EE. Integrating pathway analysis and genetics of gene expression for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:581–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers AJ, et al. A survey of genetic human cortical gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1494–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabrita MA, Christofori G. Sprouty proteins, masterminds of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yigzaw Y, Cartin L, Pierre S, Scholich K, Patel TB. The C terminus of sprouty is important for modulation of cellular migration and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22742–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CC, et al. Overexpression of sprouty 2 inhibits HGF/SF-mediated cell growth, invasion, migration, and cytokinesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:5193–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang C, et al. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by human sprouty 2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:533–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155461.50450.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urs S, et al. Sprouty1 is a critical regulatory switch of mesenchymal stem cell lineage allocation. Faseb J. 2010;24:3264–73. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-155127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heard-Costa NL, et al. NRXN3 is a novel locus for waist circumference: a genome-wide association study from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgren CM, et al. Genome-wide association scan meta-analysis identifies three Loci influencing adiposity and fat distribution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyre D, et al. Genome-wide association study for early-onset and morbid adult obesity identifies three new risk loci in European populations. Nat Genet. 2009;41:157–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherag A, et al. Two new Loci for body-weight regulation identified in a joint analysis of genome-wide association studies for early-onset extreme obesity in French and german study groups. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heid IM, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42:949–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grarup N, Sparso T, Hansen T. Physiologic characterization of type 2 diabetes-related Loci. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:485–97. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stumvoll M, Jacob S. Multiple sites of insulin resistance: muscle, liver and adipose tissue. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1999;107:107–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arner P. Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: role of fatty acids. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(Suppl 2):S5–9. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wajchenberg BL. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araki E, et al. Alternative pathway of insulin signalling in mice with targeted disruption of the IRS-1 gene. Nature. 1994;372:186–90. doi: 10.1038/372186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamemoto H, et al. Insulin resistance and growth retardation in mice lacking insulin receptor substrate-1. Nature. 1994;372:182–6. doi: 10.1038/372182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou L, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2) can mediate the action of insulin to stimulate translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface in rat adipose cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29829–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaburagi Y, et al. Role of insulin receptor substrate-1 and pp60 in the regulation of insulin-induced glucose transport and GLUT4 translocation in primary adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25839–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith-Hall J, et al. The 60 kDa insulin receptor substrate functions like an IRS protein (pp60IRS3) in adipose cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8304–10. doi: 10.1021/bi9630974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laustsen PG, et al. Lipoatrophic diabetes in Irs1(-/-)/Irs3(-/-) double knockout mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3213–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.1034802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miki H, et al. Essential role of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 in adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2521–32. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2521-2532.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tseng YH, Kriauciunas KM, Kokkotou E, Kahn CR. Differential roles of insulin receptor substrates in brown adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1918–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1918-1929.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL, Singh L. Reconstructing Indian population history. Nature. 2009;461:489–94. doi: 10.1038/nature08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnett AH, et al. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk in the UK south Asian community. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2234–46. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pruim RJ, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Abecasis GR. Mach 1.0: Rapid haplotype reconstruction and missing genotype inference. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;S79:2290. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–13. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Servin B, Stephens M. Imputation-based analysis of association studies: candidate regions and quantitative traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chambers JC, et al. Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2008;40:716–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang ZV, Deng Y, Wang QA, Sun K, Scherer PE. Identification and characterization of a promoter cassette conferring adipocyte-specific gene expression. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2933–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.