Abstract

Purpose

In addition to genomic signaling, it is accepted that ERα has non-nuclear signaling functions, which correlate with tamoxifen resistance in preclinical models. However, evidence for cytoplasmic ER localization in human breast tumors is less established. We sought to determine the presence and implications of non-nuclear ER in clinical specimens.

Experimental Design

A panel of ERα-specific antibodies (SP1, MC20, F10, 60c, 1D5) were validated by western blot and quantitative immunofluorescent (QIF) analysis of cell lines and patient controls. Then eight retrospective cohorts collected on tissue microarrays were assessed for cytoplasmic ER. Four cohorts were from Yale (YTMA 49, 107, 130, 128) and four others (NCI YTMA 99, South Swedish Breast Cancer Group SBII, NSABP B14, and a Vietnamese Cohort) from other sites around the world.

Results

Four of the antibodies specifically recognized ER by western and QIF, showed linear increases in amounts of ER in cell line series with progressively increasing ER, and the antibodies were reproducible on YTMA 49 with pearson’s correlations (r2 values)ranging from 0.87-0.94. One antibody with striking cytoplasmic staining (MC20) failed validation. We found evidence for specific cytoplasmic staining with the other 4 antibodies across eight cohorts. The average incidence was 1.5%, ranging from 0 to 3.2%.

Conclusions

Our data shows ERα present in the cytoplasm in a number of cases using multiple antibodies, while reinforcing the importance of antibody validation. In nearly 3,200 cases, cytoplasmic ER is present at very low incidence, suggesting its measurement is unlikely to be of routine clinical value.

Keywords: non-nuclear, Estrogen Receptor, cytoplasmic, breast cancer

Introduction

The Estrogen Receptor (ER) is the oldest and most successful biomarker that exists in breast cancer today (1-3); however, roughly 50% of ER-positive patients still exhibit de novo or acquired resistance to tamoxifen, suggesting that more complex mechanisms are operating in these patients (4). In addition to the classical view of the Estrogen Receptor (ER) as a nuclear hormone receptor, in the past ten years, it has become accepted that ER-alpha has non-nuclear signaling functions, referred to as non-genomic signaling. In the case of breast cancer, this non-genomic signaling can involve full-length receptor or other isoforms (5-9), as well as cross-talk with other growth-factor receptors (GFRs) (4, 10-12) or cytoplasmic kinases such as Src (13-15). In preclinical models, non-genomic signaling has been shown to underlie tamoxifen resistance (13, 16-20).

The current guidelines for measuring ER in a clinical setting, however, assess only nuclear staining using immunohistochemistry (IHC) (21). The presence of cytoplasmic or membranous immunoreactivity is ignored or assumed to be non-specific, and while individual pathologists may observe it from time to time, there is no available record of the incidence of such staining. The few reports in literature are all in cell line models, and none have shown concrete evidence to date of any cytoplasmic ER in actual breast cancer cases. Furthermore, some of these studies have used antibodies with less rigorous validation. We have previously found antibody validation to play a critical role in evaluation of protein localization (22), and have thus developed extensive antibody validation protocols (23). We also have established the use of quantitative immunofluorescence (QIF), commercialized as AQUA technology (HistoRx Inc, New Haven, Connecticut), to assess expression and localization of a wide range of biomarkers on tissue microarrays (TMAs) (24-27). In addition to the benefit of quantification on a continuous scale, QIF allows more accurate assessment of protein localization, since each slide is stained with DAPI as well as cytokeratin, and a protein of interest can be assessed for co-localization with each.

In this study, we first sought to validate a panel of ER antibodies in order to determine if non-nuclear ER existed in clinical specimens using QIF on a number of retrospective cohorts. We then reviewed the localization of expression in a series of eight cohorts displayed on TMAs. We hypothesized that patients with high levels of cytoplasmic ER would show less benefit from endocrine therapies than those with low levels.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

A panel of ATCC breast cancer cell lines was chosen to span a range of ER expression. Additionally MCF-7 cells engineered with doxycyclin-inducible ER overexpression were used, which were a gift from Elaine Alarid (see Fowler et al (28)). All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2, and grown either in suggested media, or in RPMI 1640 culture medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gemini BioProducts), 100units/mL penicillin G and 100μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), and 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco).

Antibodies

Antibodies were selected for validation based on previous use in the literature. The five antibodies selected were F10 (Santa Cruz) used at 1:1000 overnight at 4deg, SP1 (Thermo) used at 1:500 overnight at 4deg, 60c (Upstate) used at 1:2000 overnight at 4deg, 1D5 (Dako) at 1:500 overnight at 4deg, and MC20 (Santa Cruz) at 1:500 for 1hr at RT. β-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, 2146), diluted 1:4000, was used as a loading control for western blots. Rabbit and mouse cytokeratin antibodies (Dako) were used at 1:100 for immunostaining.

Western Blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 20nM TrisHCl pH8.0, 137mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 1mM NaVO3, and complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) in dH20. 25μg of each lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 4-12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPage), using NuPage MOPS SDS Running Buffer at 45mA. Resolved protein was transferred using NuPage Transfer Buffer at 50V for 2h. Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures, using the ER antibodies above.

Index TMA

Whole cell pellets (fixed in formalin and paraffin-embedded) were created from the cell line panel (for a detailed protocol, see Dolled-Filhart et al and McCabe et al (29, 30)). These pellets were cored and placed on a tissue microarray along with a panel of 40 breast cancer patient controls (spanning the range of ER expression). This TMA (referred to as the Index TMA) was used as a control array during antibody validation and immunofluorescent staining.

Patient Cohorts

In total, eight different cohorts of archival breast cancer cases, present on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded TMAs, were examined for evidence of cytoplasmic ER by immunofluorescence. One of the cohorts (YTMA 49) was also examined by traditional immunohistochemistry. Four of the TMAs were constructed at Yale according to previously published guidelines (31): YTMA 49 (diagnosed 1962-1982, n = 619, stained with 1D5, 60c, SP1, and F10), YTMA 107 (collaboration with University of Michigan as part of a Tamoxifen pharmacogenetics clinical trial (32), n = 179, stained with 1D5), YTMA 130 (diagnosed 1976-2005, n = 526, stained with 1D5 and SP1), and YTMA 128 (diagnosed 2003-2006, n = 257, stained with 1D5 and SP1). Four other cohorts came from outside institutions: NCI YTMA 99 (a Polish multi-institutional trial, n = 732 with triplicate cores for each case, stained with 1D5), NSABP B14 (a multi-institutional trial (33), n = 956, stained with SP1), South Swedish Breast Cancer Group SBII (34, 35) (n = 556, stained with 1D5), and a Vietnamese Oophorectomy cohort (premenopausal women with operable breast cancer, see Love et al (36) for more information, n = 156, stained with SP1).

Immunofluorescent (IF) Staining

Slides were deparaffinized by melting at 60°C for 20min, followed by soaking twice for 20min in xylene (JT Baker). Rehydration was performed twice in 100% EtOH for 1min, followed by 70% EtOH for 1min, and tap water for 5min. Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (3.84g sodium citrate dihydrate in 2L ddH20, brought to pH 6.0 with 1M citric acid) using the PT module from LabVision. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by 30 min incubation in 2.5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol at room temperature (RT). After washing, non-specific antigens were blocked by incubation in 0.3% bovine serum albumin in TBST for 30min at RT in humidity chamber. Rabbit Cytokeratin (Dako), diluted 1:100 in block (BSA in TBST above), and was incubated overnight at 4°C. ER was stained using various antibodies (noted under Patient Cohorts), which included 1D5 (Dako, 1:50 in block, incubated 1h at RT), SP1 (Thermo, 1:1000 in block, incubated overnight at 4°C), F10 (Santa Cruz, 1:5000 in block overnight at 4), 60c (Upstate, 1:5000 in block overnight at 4deg), MC20 (1:100 in block overnight at 4deg). Primary antibodies were followed by Alexa 546-conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit or anti-Mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:100 in mouse or rabbit EnVision reagent (Dako) for 1h at RT. Signal was amplified using Cyanine 5 (Cy5)-tyramide (Perkin-Elmer) at a dilution of 1:50 for 10min at RT. Nuclei were stained using 10μg/mL DAPI (Molecular Probes) in block for 20min at RT, and coverslips mounted with Prolong mounting medium (ProLong Gold, Molecular Probes).

AQUA analysis

ER immunofluorescence was quantified using AQUA. Briefly, a series of high-resolution monochromatic images were captured by the PM-2000 microscope (HistoRx) using AQUAsition 2.2 software (HistoRx). Images were collected for each histospot after auto-focus and auto-exposure. Fluorophores included DAPI (to create nuclear compartment), Cy3 (Alexa 546-cytokeratin to distinguish tumor from stroma and create cytoplasmic compartment), and Cy5 for the target (ER). Image analysis was performed using AQUAnalysis 2.2 software (HistoRx), which binarizes the cytokeratin stain (each pixel being “on” or “off”) to create an epithelial tumor “mask”. It uses a clustering algorithm to assign each pixel, with 95% confidence, to either a nuclear or cytoplasmic compartment. The AQUA score of ER in each subcellular compartment (nuclear, cytoplasmic, and whole tumor mask) is calculated by dividing the ER pixel intensities by the area of the compartment within which they were measured. AQUA scores are normalized to the exposure time, bit depth, and lamp hours at which the images were captured, allowing scores collected at different exposure times to be directly comparable.

Immunohistochemical Staining

IHC staining was performed on YTMA 49 in a CLIA-certified laboratory, using either the 1D5 (Dako) or SP1 (Ventana) staining system for ER in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were digitally scanned using the BioImagene slide scanner and visually assessed using ImageViewer software (BioImagene).

Assessment of Cytoplasmic ER

In order for a case to be considered positive for cytoplasmic ER, the following conditions had to be met: 1) immunoreactivity was observed using one of four valid monoclonal antibodies (1D5, SP1, 60c, F10), 2) immunoreactivity co-localized with cytokeratin but did not co-localize with DAPI, 3) immunoreactivity was robust (at least 25% the intensity of nuclear staining, or greater than nuclear staining), 4) immunoreactivity was not due to out-of-focus tissue or bleed-through from any other channel, 5) immunoreactivity was observed on the same slide as a positive (nuclear staining with no background) and negative (no staining) control cases. For each cytoplasmic case, conditions 1-5 were confirmed by two separate individuals (AWW and DLR), including a certified pathologist (DLR).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses (bivariate regressions) were performed using StatView analysis software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Antibodies to multiple epitopes of ER are highly reproducible

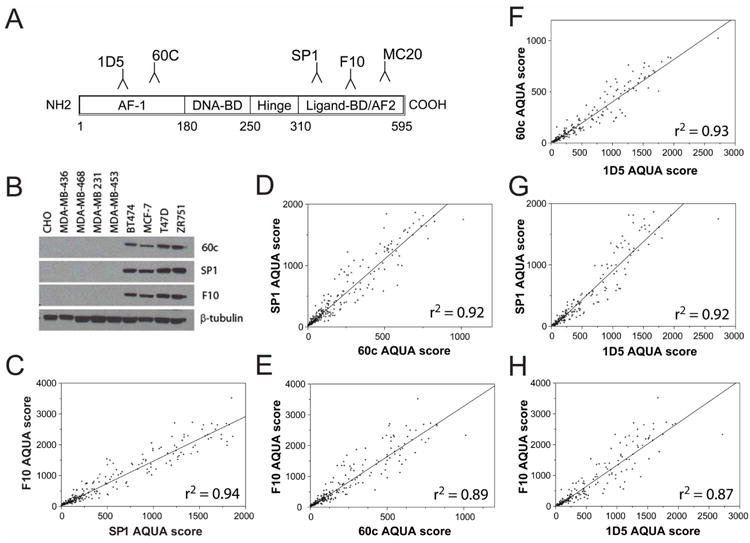

In order to see assess the existence of cytoplasmic ER in breast cancer cases, we first validated a panel of five antibodies raised against different epitopes of ER. We chose five antibodies previously reported in the literature to be specific and/or to detect cytoplasmic ER (see Figure 1A). These included 1D5 (an N-terminal mouse monoclonal from Dako, the clinical standard), SP1 (a C-terminal rabbit monoclonal, reported to be more sensitive than 1D5 and less sensitive to signal degradation due to delays in fixation (37-40)), 60c (an N-terminal rabbit monoclonal from Upstate), F10 (a C-terminal mouse monoclonal we had previously validated in the lab), and MC20 (a rabbit polyclonal reported to show cytoplasmic ER staining(41-48)). First, a panel of cell lines with known ER status was examined by western blot. SP1, 60c, and F10 showed specific detection of the expected 66kD band for full-length ER (Figure 1B) in the four lines known to be ER-positive (BT474, MCF7, T47D, ZR751). These four antibodies (1D5, F10, SP1, 60c) were then used to stain a large retrospective cohort of breast cancer cases from Yale (YTMA 49, diagnosed 1962-1982) by QIF, and levels of nuclear ER were quantified using AQUA. All antibodies showed strong reproducibility on these 619 cases (Figure 1C-H), with pearson’s r2 values ranging from 0.87 to 0.94 (r-values ranging from 0.93-0.97).

Figure 1. Antibodies to multiple epitopes of ER are highly reproducible.

Five antibodies binding to different epitopes of ER were chosen for validation, including mouse monoclonals 1D5 and F10, rabbit monoclonals SP1 and 60c, and rabbit polyclonal MC20 (A). Specific detection of a 66kD band for ER was detected by western blot in a cell line panel using F10, SP1 and 60c, with β-tubulin as loading control (B). Antibodies that passed validation (1D5, SP1, F10, 60c) were stained using QIF on YTMA 49, and nuclear ER expression levels (AQUA scores) were correlated between each antibody (C-H) showing Pearson’s coefficients (r2-values) from 0.87-0.94. AF1, activation function 1; BD, binding domain; AF2, activation function 2.

The next step in our antibody validation protocol is titration and analysis of specificity and reproducibility by immunofluorescence. Each cell line in the panel was formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and cored as tissue blocks to create the Index TMA, which also contained a panel of 40 breast cancer control cases in duplicate (spanning the range of ER expression). After titration on breast test TMAs to optimize their dilution, each antibody was individually used to stain the Index TMA by QIF. Specific nuclear staining was observed in the four ER-positive cell lines using 1D5, SP1, 60c and F10. Furthermore, progressively increased staining was seen in a cell line series induced to gradually overexpress amounts of ER (data only shown with SP1 as a representative case, see Figure 2F, top panels), confirming the specificity of these antibodies by IF. Duplicate control cases also showed strong reproducibility core-to-core.

Figure 2. Significance of antibody validation in detection of cytoplasmic ER.

A panel of breast cancer cell lines was analyzed by western blot for ER (full-length 66kD) using both MC20 and SP1 antibody and developed at different exposures (A, β-tubulin was loading control) to compare antibody specificity. Both antibodies were also stained using QIF on the Index array, which contained the same cell line panel (AQUA scores for MC20 in B, for SP1 in C), as well as a panel of patient controls. Correlation between AQUA scores for the patient controls is shown in D. A representative case is shown in E, with cytoplasmic immunoreactivity observed with MC20 (top panel), where there is only nuclear staining seen with SP1 (bottom panel). Lastly, a series of MCF-7 cells engineered with doxycyclin-inducible overexpression of ER (28) were maintained as six separate cultures, and treated with increasing amounts of doxycyclin for 48 hours, before pelleting and formalin-fixing for preparation on a TMA. IF staining was then performed on these cell lines, using both SP1 (F, top panels) and MC20 (F, bottom panels) in order to further validate specificity of immunoreactivity. Doxy, doxycyclin.

We also sought to test the MC20 antibody since it is commonly cited in published descriptions of cytoplasmic ER(41-48). We found that, at low exposure, the MC20 antibody appeared to detect a specific 66kD band on a western blot of cell line controls (Figure 2A, top panel). However, when the blot was left for longer exposure, and compared to SP1, MC20 showed non-specific immunoreactivity in a series of ER-negative cell lines (Figure 2A), as well as multiple immunoreactive bands. Similar non-specific immunoreactivity was observed when MC20 was used to quantify ER by IF on the cell line panel (Figure 2B), in contrast to SP1 (Figure 2C). On the panel of patient controls present on the same Index TMA, QIF analysis of ER expression using MC20 again did not correlate with SP1 (Figure 2D), and showed strong cytoplasmic staining in cases that were strictly nuclear with SP1 (Figure 2E). Lastly, in a panel of cell lines engineered to overexpress increasing amounts of ERα, MC20 showed constitutively high levels of cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, in contrast to increasing nuclear immunoreactivity seen with SP1 (Figure 2F). To confirm this data was not due to a poor antibody lot, we repeated each experiment with a second lot of MC20, and found the same results. Thus MC20 was not included in the panel of valid antibodies.

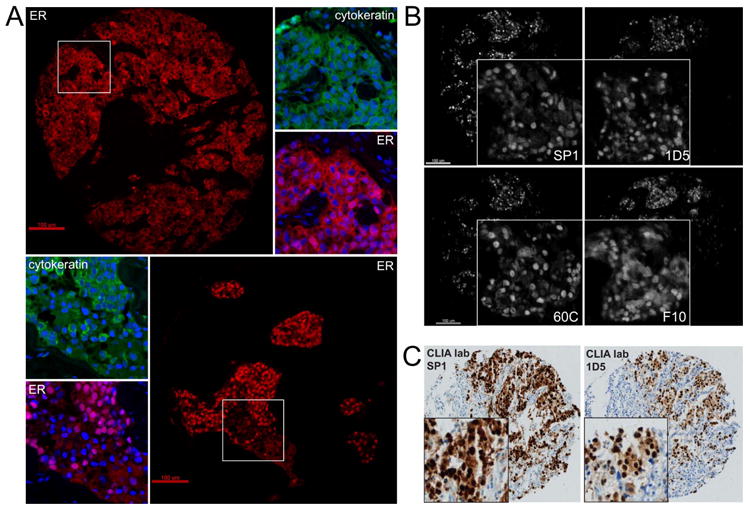

Detection of cytoplasmic ER by multiple antibodies and methods

Once specific and reproducible detection of nuclear ER was confirmed using multiple antibodies, we examined a series of large retrospective cohorts of breast cancer cases on TMAs to determine the frequency of non-nuclear expression of ER. We were able to find cases with strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in epithelial cells (co-localized with cytokeratin, not co-localized with DAPI, Figure 3A). In all cases, the staining appeared to be more cytoplasmic than membranous, and while a few cases were strictly cytoplasmic without any nuclear reactivity (Figure 3A, top panel), in a majority of instances the cytoplasmic staining was observed along with nuclear staining (Figure 3A, bottom panel). When subsequent cuts were available (this was the case in our Yale cohorts), we were able to assess expression using multiple ER antibodies and confirm that the cytoplasmic reactivity was observed using more than one antibody (Figure 3B), suggesting it was not an epitope-specific artifact, and was potentially full-length ER or an isoform containing an intact N and C terminus. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic immunoreactivity was observed using traditional IHC methods as well (Figure 3C), with both N- (1D5) and C-terminal (SP1) antibodies.

Figure 3. Detection of cytoplasmic ER by multiple antibodies and methods.

Validated antibodies (1D5, SP1, F10, 60c) were stained by QIF on eight retrospective breast cancer cohorts in order to assess presence of cytoplasmic ER according to six conditions (see Methods). Representative image of two cases are shown in A (both stained with SP1), showing cytoplasmic immunoreactivity co-localized with cytokeratin, either in the absence of nuclear staining (top panel, A), as well as alongside or along with nuclear staining (bottom panel, B). Scale bars are 100μm, insets are higher magnification. On cases from YTMA 49, which was stained using all four antibodies, cytoplasmic immunoreactivity was observed with each antibody (B, scale bars are 100μm, insets are higher magnification). Cytoplasmic immunoreactivity was also observed using traditional IHC performed in a CLIA-certified lab with both SP1 (Ventana) and 1D5 (Dako) systems (C, insets are higher magnification).

Analysis of multiple retrospective cohorts suggests incidence of cytoplasmic ER is low

We have assessed cytoplasmic ER by QIF on nearly 3,200 individual cases from eight different retrospective breast cancer cohorts, four from Yale (YTMA 49, 107, 128, and 130) and four from outside sources, including two multi-institutional trials (NSABP B14 and South Swedish Breast Cancer Group SBII) as well as two others (NCI YTMA 99 and a Vietnamese Oophorectomy cohort). One of these (YTMA 49) was assessed by QIF in duplicate (a second core from each patient) as well as by traditional IHC. In order for a case to be considered “positive” for cytoplasmic ER, five conditions had to be met, as described in the methods section.

Overall the incidence of cytoplasmic staining only averaged 1.49%, ranging from 0% to 3.2% at best (Table I), an incidence that was too low to discover any prognostic or predictive significance, even with relatively large cohorts. Since many of the cytoplasmic cases were observed on cohorts from outside institutions, we did not have broad access to the original tissue to perform any follow-up analysis on the individual cases. We attempted to extract RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cores of the cases found in YTMA 49 and 130 (in Table I), however since most of the cases are older then 10 years, the RNA was insufficiently preserved for successful RT-PCR analysis with ER-specific primers.

Table I.

Incidence of cytoplasmic ER on multiple retrospective breast cancer cohorts

| Cohort | Number of cytoplasmic cases | Number of total cases validated | Percent (%) of cases with cytoplasmic staining | Antibodies used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI YTMA 99 | 17 | 732 | 2.3 | 1D5 |

| NSABP B14 | 21 | 655 | 3.2 | SP1 |

| South Swedsh BCG SBII | 0 | 556 | 0 | 1D5 |

| YTMA 49 | 2 | 378 | 0.5 | 1D5, SP1, 60c, F10 |

| YTMA 130 | 4 | 316 | 1.3 | 1D5, SP1 |

| YTMA 128 | 0 | 183 | 0 | 1D5, SP1 |

| VIE OO Cohort | 0 | 156 | 0 | SP1 |

| TMA 107 | 3 | 179 | 1.7 | 1D5 |

| Total | 47 | 3155 | 1.49 |

Eight retrospective cohorts were assessed for presence of cytoplasmic ER, with multiple validated antibodies, according to the six conditions outlined in the Methods. Incidence of cytoplasmic ER was confirmed by two separate individuals (AWW and DLR, one a board-certified Pathologist and the other a Pathology graduate student), and reported as a percentage of the total cases with valid immunostaining (eliminated cases with missing tissue, out of focus regions, etc). NCI, National Cancer Institute; YTMA, Yale Tissue Microarray; NSABP, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project; BCG, Breast Cancer Group; VIE, Vietnamese; OO, Oophorectomy

Discussion

We have found that four antibodies to ER-alpha (1D5, SP1, F10 and 60c) are highly reproducible and specific by both western blot as well as QIF, in cell lines and in FFPE cases. Using each of these valid antibodies, we have found evidence for cytoplasmic ER in breast cancer specimens, with both IF and traditional IHC. However, across nearly 3,200 cases, spanning eight different retrospective cohorts, we found cytoplasmic ER is present at very low incidence. Thus, its measurement by these methods is unlikely to be of prognostic or predictive value in untreated cases.

Confirmation of immunoreactivity by multiple antibodies suggests that the cytoplasmic localization is not an epitope-specific artifact. However, there are other artifacts that cannot be ruled out, including the possibility that the cytoplasmic localization is a function of fixation method, tissue age, processing, or some other ill-defined pre-analytic variable. The specimens assessed in this study came from a variety of institutions and in many cases we have no record of how the tissue was handled. Follow-up studies on many of the cases was not possible since we did not have access to tissue. Nevertheless, studies are ongoing to determine the identity of the cytoplasmic immunoreactivity we have observed. To date, we have seen no evidence of higher incidence on tissue with longer time-to-fixation, or other pre-analytic variables. We also have no evidence for correlation between cytoplasmic ER immunoreactivity and expression of other biologically-relevant markers, including HER2, PR and stem-cell markers (ALDH and CD44 co-expression). However, we have observed some cytoplasmic staining with ER antibodies on melanoma tissue, and are in the process of determining the identity of this immunoreactivity.

The low incidence overall which we have observed is surprising, given the extent of existing data on functional non-genomic ER. One explanation for this is the discrepancies between different antibodies. Our data suggests that extensive antibody validation, as we have previously described (22, 23) is critical in assessment of ER localization. Additionally, essentially all of the evidence for cytoplasmic ER is shown in preclinical models, most of them cell lines where rapid localization of the receptor was observed. A patient tissue sample, obtained and fixed at a single moment in time, may not be able to detect such a short-lived event. Additionally, the majority of cell lines where cytoplasmic ER was observed in a more permanent nature were treated with tamoxifen. It is difficult to test patient tissue after treatment with tamoxifen, since most cohorts are made from primary breast tumors prior to any sort of treatment. In the future, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy cohorts may be able to resolve this issue.

Another explanation for our observations could be the use of TMAs instead of whole sections. If localization of ER is heterogeneous within tumors, it may be seen in whole sections, but missed in low sampling (one-fold redundant) TMA cohorts. While whole sections were not available for any of these cohorts, the use of TMAs also allowed us to maximize the number of specimens included in this study. Furthermore, in smaller series where we assessed ER on whole sections, cytoplasmic ER was not observed (49). We did, however, have triplicate cores for each case in the NCI YTMA 99 cohort, and in cases with evidence for cytoplasmic ER, we were able to observe it in multiple cores. Additionally, the largest Yale cohort (YTMA 49) has been produced at 12-fold redundancy. We found that the two cases initially positive for cytoplasmic ER were also positive in other cores from the same patient. Furthermore, examination of other cores did not reveal any new cytoplasmic cases when examining other blocks. Finally, it is possible that low levels of cytoplasmic ER exist in many clinical specimens, but the levels of expression are below the threshold of detection using the QIF or IHC assays. We have not yet determined a way to isolate and quantify ER that is present at very low levels in human tissue specimens.

Our initial goal was to develop an assay that measured cytoplasmic ER in order to predict patients who would show less benefit from endocrine therapies. However, after extensive antibody validation and examination of a large number of cases, we cannot find evidence for cytoplasmic ER on more than 4% of cases. Although these cohorts are reasonably large, the low event frequency results in insufficient statistical power to look for meaningful associations with outcome.

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Clinicians today rely on measurement of nuclear Estrogen Receptor (ER) as a hallmark of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, for over 10 years it has been widely accepted that ER exists and functions outside the nucleus, contributing to growth and survival as well as resistance to endocrine therapies in cellular models, suggesting it’s measurement could be of prognostic or predictive value, and could help address the problem of tamoxifen resistance. However, in the first study to thoroughly examine the incidence of cytoplasmic ER in human cases, we find an incidence of only 1.5%, suggesting cytoplasmic ER may only be a transient occurrence or an artifact of immunostaining, and is therefore unlikely to be of predictive value in the current clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by additional grants from the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute to Mark Sherman and Jonine Figueroa, and an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator award to Lynn Henry.

Support for this research comes from NIH R33 CA 106709 (to DLR) and a US Army CDMRP pre-doctoral fellowship (AWW).

References

- 1.Fisher B, Redmond C, Brown A, Wolmark N, Wittliff J, Fisher ER, et al. Treatment of primary breast cancer with chemotherapy and tamoxifen. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107023050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Redmond C, Brown A, Wickerham DL, Wolmark N, Allegra J, et al. Influence of tumor estrogen and progesterone receptor levels on the response to tamoxifen and chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:227–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.4.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne SJ, Bowen RL, Jones JL, Wells CA. Predictive markers in breast cancer--the present. Histopathology. 2008;52:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiff R, Massarweh SA, Shou J, Bharwani L, Arpino G, Rimawi M, et al. Advanced concepts in estrogen receptor biology and breast cancer endocrine resistance: implicated role of growth factor signaling and estrogen receptor coregulators. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 1):s10–s20. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li L, Haynes MP, Bender JR. Plasma membrane localization and function of the estrogen receptor alpha variant (ER46) in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831079100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, Loggie BW, Chang Y, Deuel TF. A variant of estrogen receptor-{alpha}, hER-{alpha}36: transduction of estrogen- and antiestrogen-dependent membrane-initiated mitogenic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9063–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603339103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acconcia F, Ascenzi P, Bodeci A, Spisni E, Tomasi V, Trentalance A, et al. Palmitoylation-dependent estrogen receptor-alpha membrane localization regulation by 17 beta-estradiol. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:231–7. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonyaratanakornkit V, Edwards DP. Receptor mechanisms mediating non-genomic actions of sex steroids. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:139–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Miksicek RJ. Identification of a dominant negative form of the human estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1707–15. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-11-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, Barnes CJ, Kumar R. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status modulates subcellular localization of and interaction with estrogen receptor α in breast cancer cells. Clin Canc Res. 2004;10:3621–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baserga R, Peruzzi F, Reiss K. The IGF-1 receptor in cancer biology. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:873–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hitosugi T, Sasaki K, Sato M, Suzuki Y, Umezawa Y. Epidermal growth factor directs sex-specific steroid signaling through Src activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10697–706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiscox S, Morgan L, Green TP, Barrow D, Gee J, Nicholson RI. Elevated Src activity promotes cellular invasion and motility in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Canc Res & Treat. 2006;97:263–74. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greger JG, Fursov N, Cooch N, McLarney S, Freedman LP, Edwards DP, et al. Phosphorylation of MNAR promotes estrogen activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1904–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01732-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Wong CW, McNally C, Nickbarg E, Komm BS, Cheskis BJ. Estrogen receptor-interacting protein that modulates its nongenomic activity-crosstalk with Src/Erk phosphorylation cascade. Pnas. 2002;99:14783–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192569699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Fan P, Wang J, Santen RJ, Yue W. Long-term treatment with tamoxifen facilitates translocation of estrogen receptor alpha out of the nucleus and enhances its interaction with EGFR in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Canc Res. 2007;67:1352–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massarweh S, Schiff R. Unraveling the mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer: New therapeutic opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1950–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, Qin L, Tsimelzon A, Huang S, et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res. 2008;68:826–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gururaj AE, Rayala SK, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Novel mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy: Genomic and nongenomic considerations. Clin Canc Res. 2006;12(3 Suppl):s1001–s7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiseman LR, Johnson MD, Wakeling AE, Lykkesfeldt AE, May FE, Westley BR. Type I IGF receptor and acquired tamoxifen resistance in oestrogen-responsive human breast cancer cells. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:2256–64. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2784–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anagnostou VK, Welsh AW, Giltnane JM, Siddiqui S, Liceaga C, Gustavson M, et al. Analytic variability in immunohistochemistry biomarker studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:982–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordeaux J, Welsh A, Agarwal S, Killiam E, Baquero M, Hanna J, et al. Antibody validation. Biotechniques. 2010;48:197–209. doi: 10.2144/000113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger AJ, Davis DW, Tellez C, Prieto VG, Gershenwald JE, Johnson MM, et al. Automated quantitative analysis of activator protein-2alpha subcellular expression in melanoma tissue microarrays correlates with survival prediction. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11185–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, King BL, Rimm DL. Quantitative analysis of breast cancer tissue microarrays shows that both high and normal levels of HER2 expression are associated with poor outcome. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giltnane JM, Ryden L, Cregger M, Bendahl PO, Jirstrom K, Rimm DL. Quantitative measurement of epidermal growth factor receptor is a negative predictive factor for tamoxifen response in hormone receptor positive premenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3007–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moeder CB, Giltnane JM, Harigopal M, Molinaro A, Robinson A, Gelmon K, et al. Quantitative justification of the change from 10% to 30% for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 scoring in the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines: tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer and its implications for tissue microarray based assessment of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5418–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler AM, Solodin N, Preisler-Mashek MT, Zhang P, Lee AV, Alarid ET. Increases in estrogen receptor-alpha concentration in breast cancer cells promote serine 118/104/106-independent AF-1 transactivation and growth in the absence of estrogen. Faseb J. 2004;18:81–93. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0038com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolled-Filhart M, McCabe A, Giltnane J, Cregger M, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Quantitative in situ analysis of beta-catenin expression in breast cancer shows decreased expression is associated with poor outcome. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5487–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCabe A, Dolled-Filhart M, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) of in situ protein expression, antibody concentration, and prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1808–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camp RL, Neumeister V, Rimm DL. A decade of tissue microarrays: progress in the discovery and validation of cancer biomarkers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5630–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry NL, Rae JM, Li L, Azzouz F, Skaar TC, Desta Z, et al. Association between CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen-induced hot flashes in a prospective cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:571–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0309-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Poisson R, Bowman D, Couture J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:479–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902233200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryden L, Jonsson PE, Chebil G, Dufmats M, Ferno M, Jirstrom K, et al. Two years of adjuvant tamoxifen in premenopausal patients with breast cancer: a randomised, controlled trial with long-term follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryden L, Jirstrom K, Bendahl PO, Ferno M, Nordenskjold B, Stal O, et al. Tumor-specific expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 but not vascular endothelial growth factor or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 is associated with impaired response to adjuvant tamoxifen in premenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4695–704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Love RR, Duc NB, Allred DC, Binh NC, Dinh NV, Kha NN, et al. Oophorectomy and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy in premenopausal Vietnamese and Chinese women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2559–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheang MC, Treaba DO, Speers CH, Olivotto IA, Bajdik CD, Chia SK, et al. Immunohistochemical detection using the new rabbit monoclonal antibody SP1 of estrogen receptor in breast cancer is superior to mouse monoclonal antibody 1D5 in predicting survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5637–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brock JE, Hornick JL, Richardson AL, Dillon DA, Lester SC. A comparison of estrogen receptor SP1 and 1D5 monoclonal antibodies in routine clinical use reveals similar staining results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:396–401. doi: 10.1309/AJCPSKFWOLPPMEU9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocha R, Nunes C, Rocha G, Oliveira F, Sanches F, Gobbi H. Rabbit monoclonal antibodies show higher sensitivity than mouse monoclonals for estrogen and progesterone receptor evaluation in breast cancer by immunohistochemistry. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu J, Kulkarni S, Chandrasekhar R, Rees M, Hyde K, Wilding G, et al. Effect of delayed formalin fixation on estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer: a study of three different clones. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:813–9. doi: 10.1309/AJCPVCX83JWMSBNO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedram A, Razandi M, Sainson RC, Kim JK, Hughes CC, Levin ER. A conserved mechanism for steroid receptor translocation to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22278–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1996–2009. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedram A, Razandi M, Wallace DC, Levin ER. Functional estrogen receptors in the mitochondria of breast cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2125–37. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Razandi M, Pedram A, Levin ER. Heat shock protein 27 is required for sex steroid receptor trafficking to and functioning at the plasma membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3249–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01354-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Razandi M, Pedram A, Merchenthaler I, Greene GL, Levin ER. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors exist and functions as dimers. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2854–65. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Razandi M, Pedram A, Rosen E, Levin ER. BRCA1 inhibits membrane estrogen and growth factor receptor signaling to cell proliferation in breast cancer. Mol Cell Bio. 2004;24:5900–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5900-5913.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clarke CH, Norfleet AM, Clarke MS, Watson CS, Cunningham KA, Thomas ML. Perimembrane localization of the estrogen receptor alpha protein in neuronal processes of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;71:34–42. doi: 10.1159/000054518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norfleet AM, Thomas ML, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Estrogen receptor-alpha detected on the plasma membrane of aldehyde-fixed GH3/B6/F10 rat pituitary tumor cells by enzyme-linked immunocytochemistry. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3805–14. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung GG, Zerkowski MP, Ghosh S, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor heterogeneity in breast cancer. Lab Invest. 2007;87:662–9. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]