Abstract

Cleft palate represents the second most common birth defect and carries substantial physiologic and social challenges for affected patients, as they often require multiple surgical interventions during their lifetime. A number of genes have been identified to be associated with the cleft palate phenotype, but etiology in the majority of cases remains elusive. In order to better understand cleft palate and both surgical and potential tissue engineering approaches for repair, we have performed an in-depth literature review into cleft palate development in humans and mice, as well as into molecular pathways underlying these pathologic developments. We summarize the multitude of pathways underlying cleft palate development, with the transforming growth factor β superfamily being the most commonly studied. Furthermore, while the majority of cleft palate studies are performed using a mouse model, studies focusing on tissue engineering have also focused heavily on mouse models. A paucity of human randomized controlled studies exists for cleft palate repair, and so far, tissue engineering approaches are limited. In this review, we discuss the development of the palate, explain the basic science behind normal and pathologic palate development in humans as well as mouse models and elaborate on how these studies may lead to future advances in palatal tissue engineering and cleft palate treatments.

Key words: palatal development, cleft palate, Wnt signaling, Hedgehog signaling, palate culture, cleft palate surgery, osteogenesis

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) represents the second most common birth defect, with an incidence ranging from 1 in 500 to about 1 in 2,500 births. This suggests that susceptibility genes likely differ between races.1 Furthermore, environmental risk factors have been identified, making it difficult to isolate a single cause behind CLP. When assessing all cases, annual treatment costs exceed $100 million in direct hospital costs alone in the United States.2 Taken together, whether one is referring to CLP or isolated cleft palate, these are common birth defects, and they represent an enormous biomedical burden. Affected children with CLP require their first operation as neonates to close the cleft lip; closure of the palate happens during a second operation at approximately 6–12 months of life. Following the initial closure of the cleft palate, these children face continuing challenges with speech, facial growth, dental occlusion and hearing. Affected children often undergo intensive therapy to establish normal speech patterns, but may require further surgery if unsuccessful. In addition to speech, children endure substantial dental problems that will require orthodontic intervention. Not infrequently, affected children have associated midface hypoplasia due to the restraining effect of palatal scarring on the growing maxilla and require orthognathic surgery later in life.

Development of the primary and secondary palate have been shown to be unique entities on a genetic and embryologic level.1,3 In the majority (70%) of cleft lip and palate, these deformities occur independent from other craniofacial abnormalities and are called “isolated, non-syndromic cleft lip and palate.” Though the large growth of genetics research has uncovered numerous pathways involved with syndromic cleft lip, we lack a solid genetic and molecular understanding of the cause for these isolated cleft cases.

Previous studies indicate that the pathogenesis of cleft palate is multifactorial and likely has both genetic and environmental factors. Much of our knowledge of craniofacial clefting arises from case studies of patients and selected animal models. A number of genes have been identified to be associated with the cleft palate phenotype, but the etiology of the majority of cases remains elusive. In this review, we discuss palatal development, explore the basic science behind normal and pathologic palate development and elaborate on how these findings may lead to future advances in the treatment of cleft palate.

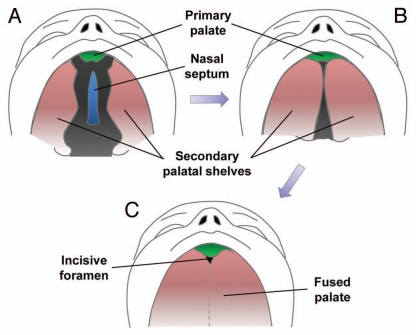

Cleft Palate Development

The facial region of the mammalian embryo originates mainly from the frontonasal prominence (forehead, nose, philtrum and primary palate), the maxillomandibular prominence from the first branchial arch (maxilla, mandible, lateral upper lip and secondary palate) and the lateral nasal prominences. The intermaxillary segment forms when the two medial nasal prominences fuse together at the midline, giving rise to the philtrum of the lip, four incisor teeth and the primary palate of the adult. The secondary palate forms from outgrowths of the maxillary prominences called palatal shelves or palatine processes; these palatal shelves fuse at the midline (Fig. 1A and B). The definitive palate is formed following fusion of the primary and secondary palates at the incisive foramen and with the nasal septum above (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Human palatal development. (A) Week six of human palatal development, with the secondary palate shown vertically on each side of the tongue and a gap between the secondary palate, nasal septum and primary palate. (B) After descent of the tongue, the secondary palatal shelves elevate and orient horizontally, allowing them to come in contact and begin fusing. (C) Fusion of the primary and secondary palate and the nasal septum separating the oropharynx from the nasopharynx. Figure modified from Dixon et al.1

The palate is limited anteriorly by the incisive foramen and extends posteriorly through the structures of the hard palate, soft palate and uvula. The structures anterior to the incisive foramen are collectively referred to as the pre-palatal structures or the primary palate (upper lip and alveolus). The structures posterior to the incisive foramen are called the secondary palate. As is the case for all branchial arches, the first arch that forms the palate contains mesodermal mesenchymal cells, ectoderm-derived neural crest cells, a cranial nerve (trigeminal) and a blood supply (maxillary artery).

Development of the human hard palate occurs between weeks 5 and 12 of gestation. The lateral palatine processes gradually grow toward the midline, fusing first anteriorly by week 8 and posteriorly as far back as the uvula by week 12. Development of the secondary palate occurs from the lateral palatine processes that grow vertically and obliquely on both sides of the developing tongue (Fig. 1A). As the tongue descends, the palatine processes swing upward into a more transverse orientation (Fig. 1B). Some instances of cleft palate can be caused by failure of descent of the tongue, as in the case of Pierre Robin Syndrome where children have an underdeveloped mandible and failure of tongue descent, leading to cleft palate formation and respiratory compromise.

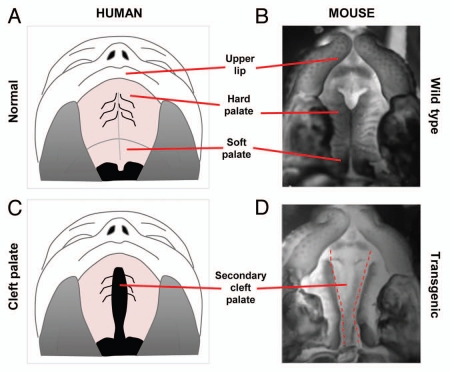

In mice, there is a significant amount of similarity in palatal development (Fig. 2A–D). Mouse facial development begins at E9.5 (corresponding to week 4 gestation in humans) with the appearance of the frontonasal process, paired maxillary and mandibular processes (late week 4 in humans). These processes have a cranial neural crest mesenchymal core surrounded by ectoderm-derived epithelium.4 The upper lip develops from the ventral frotonasal process at E10. Subsequently, the nasal placodes invaginate, and the medial and lateral nasal processes form. Growth and apposition of the medial nasal processes with each other and with the maxillary process create the intermaxillary segment, which consists of upper lip, upper two incisors and the primary palate (week 4 in human).5 By E12.5, the primary palate and upper lip development is complete (week 7 in humans). Secondary palate development starts on E11.5 (early week 7 human gestation). From E12–E14, the palatal shelves enter their active growth phase (human gestation weeks 7–8), at which time the palatal shelves are positioned vertically between the cheeks and lateral to the elevated tongue. At E14.5–E15 (week 9 in humans), the palatal shelves elevate and reorient into a horizontal position above the tongue. Subsequently, the shelves oppose and adhere along their medial edge, creating a transient medial epithelial seam. The palatal shelves then fuse anteriorly with the primary palate at the incisive foramen and dorsally with the nasal septum. The medial epithelial seam disintegrates and fusion of the palatal shelf, primary palate and vomer epithelia allow separation of the oral and nasal cavities, which is necessary for simultaneous breathing and feeding. The hard palate forms from osteogenic differentiation of palatal shelf mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts. Palatal fusion is completed by E15.5, at which point mesenchymal condensation occurs, followed by the osteogenic differentiation of the palatal mesenchyme, leading to formation of the palatine bone in the secondary palate. By E16.5, secondary palate formation is complete (10 weeks in humans).

Figure 2.

Correlation between human and mouse palates. (A) Normal human upper lip, hard palate and soft palate. (B) Normal mouse upper lip, hard palate and soft palate. (C) Cleft of the secondary palate in human patient. (D) Clefting of secondary palate in transgenic mouse.

Abnormal Palate Development/Types of Cleft Palate

Clefts of the palate alone or associated with cleft lip may involve either the primary or secondary palate and frequently both (complete clefts). Those involving the primary palate are associated with clefts of the lip. Palatal clefts may also be unilateral or bilateral. Isolated clefts of the secondary palate (incomplete clefts) occur in the absence of defects in either the lip or the alveolar process (Fig. 2C and D). Because palatal fusion occurs in an anterior to posterior direction, clefts of the secondary palate may involve only the soft palate or both the soft and hard palates together.6 Clinically, clefting in the secondary palate extends anteriorly from the uvula to varying degrees, often involving the hard palate.7 In complete forms, the cleft can affect the entire secondary palate, reaching the incisive foramen, leaving the nasopharynx in direct communication with the oral cavity. The vomer can thus be seen as a midline structure extending from the base of the skull.

While complete and incomplete clefts of the palate may be readily apparent on physical exam, other, more subtle forms may also exist with variable import with regard to feeding, speech development and ear infections.8 The submucous cleft palate is defined by the classic triad of a bifid uvula, palatal muscle diastasis and a midline notch in the posterior edge of the bony palate.8,9 The muscle separation results in a bluish, two-layered mucosal bridge, the zona pellucida, while the midline notch results from an abnormal development of the posterior nasal spine. Though the majority of patients with submucous clefts remain asymptomatic, approximately 15% develop velopharyngeal insufficiency with hypernasal speech.9 This occurs as the velum is often too short and thin, resulting in limited mobility and easy fatigability. Eventual failure to properly obturate the pharyngeal space develops, particularly after patients undergo adenoidectomy.

All clefts involving the secondary palate (with or without associated cleft lip), including those of the submucous variety, demonstrate abnormal morphology with respect to the levator veli palatini and tensor veli palatini muscles. The levator veli palatini muscles originate from the petrous portion of the temporal bone and medial surface of the auditory tube and normally interdigitate within the central velum to form a sling suspending the soft palate from the base of the skull.10 The tensor veli palatini originates from the scaphoid fossa and pterygoid plate, coursing around the hamulus to form an aponeurosis in the anterior third of the soft palate.10 In patients with clefts of the secondary palate, these muscles aberrantly insert into the posterior edge of the hard palate forming Veau's cleft muscle.11 As the levator veli palatini is oriented sagittaly in an anterior-posterior direction, any attempt at surgical correction must anatomically restore the levator sling to a medial-lateral course for proper vector of pull.12,13

Molecular Genetics of Cleft Palate

Gaining a solid understanding of the molecular causes of cleft palate has been complicated due to the plethora of factors that can, when mutated, result in various forms of clefting. There has been a large number of studies on a variety of pathways addressing palatal development. We performed a literature search of PubMed as an attempt to break down this plethora of pathways investigated. The following search terms were used in combination to identify appropriate studies: Cleft palate, palatogenesis, gene signaling and animal studies. The search was limited to studies published in English from 2000–2011 and included both human and animal studies (Tables 1 and 2). Extracellular signaling factors were the most commonly studied, with the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) superfamily as the subject of the majority of these studies (Table 2). To assess animal models currently being used to study CLP, a literature search of PubMed was performed using the following search terms: Cleft palate, palatogenesis, repair, gene signaling and animal studies. The search was limited to studies published in English from 2000 to 2011. Studies were excluded if the full text was inaccessible, or if the animal model was not clearly identified in the methods section. Clearly, the majority of studies used mice as the primary animal model (Table 3). Most in vivo models are of two varieties: transgenic mice with cleft phenotype and a teratogen-induced cleft palate.

Table 1.

Genetic pathways involved in cleft lip and palate

| Article No. | PMID | Genetic Pathway (wnt, shh, BMP) | Evidence |

| 1 | 12223417 | Fgf8 | 1C |

| 2 | 15572143 | Fgf10 | 1C |

| 3 | 21185284 | Wnt | 1E |

| 4 | 19631205 | BMP, FGF, wnt | 1A, C, E |

| 5 | 15102710 | BMP | 1A |

| 6 | 16990542 | Sumo1 | 3 |

| 7 | 17846996 | TBX22/Sumo1 | 3 |

| 8 | 17089422 | PVRL1 | 4 |

| 9 | 12520078 | EGFR | 1A |

| 10 | 14728799 | Msx homeobox | 1A |

| 11 | 17601559 | Wnt | 1E |

| 12 | 14755462 | Wnt | 1E |

| 13 | 11359935 | TGFβ | 1A |

| 14 | 12019011 | TGFβ | 1A |

| 15 | 16607638 | Jag2-Notch1 | 6 |

| 16 | 18413325 | Wnt | 1E |

| 17 | 14756664 | BMP, Shh | 1A, D |

| 18 | 14645125 | MES degeneration | 4 |

| 19 | 15361870 | PDGF | 1B |

| 20 | 15203181 | GABA | 6 |

| 21 | 14729481 | Smad2-dependent Alk-5-driven by TGFβ3 | 1A, 2 |

| 22 | 16955138 | Insig 1,2 cholesterol pathway | 7 |

| 23 | 18161794 | Nat2 | 8 |

| 24 | 15831593 | CDH1/E-cadherin | 4 |

| 25 | 12376112 | TGF/β3 | 1A |

| 26 | 10932185 | Ryk (RTK) | 8 |

| 27 | 17041601 | IRF | 2 |

| 28 | 18452349 | GABRB3 | 6 |

| 29 | 17849453 | GAD 67 | 6 |

| 30 | 12975342 | Tgf βr2 | 1A |

| 31 | 12807959 | MSX1 | 1A |

| 32 | 16284941 | Meox-2 | 6 |

| 33 | 16998816 | Wnt9b | 1E |

| 34 | 9215640 | TGFb3 | 1A |

| 35 | 15103710 | GAD67 | 6 |

| 36 | 2416245 | HA and CS | 5 |

| 37 | 12219090 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 38 | 18001154 | Activin signaling | 1A |

| 39 | 16496313 | Wnt3/Wnt9b | 1E |

| 40 | 11420059 | Col11a1 | 5 |

| 41 | 18191119 | Wnt11 and Fgfr1b | 1C, 1E |

| 42 | 11391199 | Fgfr 1/2 | 1C |

| 43 | 17377962 | SATB2 | 3 |

| 44 | 15716346 | Bmp | 1A |

| 45 | 15731757 | TGFβR1/2 | 1A |

| 46 | 10716617 | Bmp | 1A |

| 47 | 10753521 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 48 | 12673280 | Col11A2 | 5 |

| 49 | 15870292 | Mn1 | 3 |

| 50 | 15721140 | Notch/jagged2 | 6 |

| 51 | 16723652 | MSX1 | 1A |

| 52 | 10853828 | Desmosomal DSC2 | 4 |

| 53 | 17376812 | Snail, slug | 6 |

| 54 | 15275855 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 55 | 17452626 | TGfβ3/smad | 1A, 2 |

| 56 | 17442359 | Retinoic acid | 6 |

| 57 | 16880535 | Crk | 4 |

| 58 | 15199404 | Fgf/shh | 1C, 1D |

| 59 | 16168717 | Shh | 1D |

| 60 | 17360555 | Fgf | 1C |

| 61 | 17097601 | Pax9/shh in TGFβ3 regulation | 1D, 1A |

| 62 | 15562585 | Type II collagen | 5 |

| 63 | 12203729 | Sim2 in HA synthesis | 5 |

| 64 | 10932188 | PVRL1, nectin-1 | 4 |

| 65 | 10731669 | p57Kip2, CDK inhib. | 8 |

| 66 | 12490557 | PDGFRalpha | 1B |

| 67 | 12854656 | Folbp1, Shh | 1A |

| 68 | 15028671 | Mnt | 2 |

| 69 | 12068957 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 70 | 10742093 | Msx1 | 1A |

| 71 | 16109396 | MES cells/Shh | 1D |

| 72 | 12651933 | MSX1TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 73 | 16280635 | DHCR7, cholesterol | 7 |

| 74 | 12812790 | Foxf2 | 2 |

| 75 | 15888125 | TGFβ/Smad 3/dishevelled | 1A, 1E, 2 |

| 76 | 17693063 | FGF/Spry2/Shh | 1C, 1D |

| 77 | 17941048 | PDGF-C | 1B |

| 78 | 15543606 | PDGFR-alpha | 1B |

| 79 | 16780827 | Irf6/TGFβ | 1A, 2 |

| 80 | 16141225 | Shox2, Fgf | 1C |

| 81 | 17652350 | PDS5B | 6 |

| 82 | 12163415 | Msx1/Bmp | 1A |

| 83 | 11165488 | Fgf | 1C |

| 84 | 15939375 | IRF6/Smad | 2 |

| 85 | 11559848 | TBX22 | 3 |

| 86 | 12412015 | Tbx22 | 3 |

| 87 | 15118109 | Tbx10 | 3 |

| 88 | 12165566 | TTF-2 | 2 |

| 89 | 19092777 | PDGF-C | 1B |

| 90 | 12815624 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 91 | 12627230 | FGFR1 | 1C |

| 92 | 18264099 | PDGF | 1B |

| 93 | 17066417 | PDGF-C/RA | 1B, 6 |

| 94 | 18278815 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 95 | 19401770 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 96 | 12412014 | IP 3/TGF | 1A |

| 97 | 19282774 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 98 | 19036739 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 99 | 18948418 | TBx22 | 3 |

| 100 | 16405370 | PTCH | 1D |

| 101 | 14729838 | TBX22 | 3 |

| 102 | 18431835 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 103 | 18423521 | TFAP2A | 9 |

| 104 | 19281781 | TGFβ1/3 | 1A |

| 105 | 16641627 | PVRL1/Jag2 | 4, 6 |

| 106 | 14630905 | MSX1 | 1A |

| 107 | 18836445 | AP-2/IRF6 | 2 |

| 108 | 11559849 | PVRL1 | 4 |

| 109 | 17868388 | TBX22 | 3 |

| 110 | 19249007 | BMP4 | 1A |

| 111 | 12514106 | Fgfr1 | 1C |

| 112 | 16563169 | IRF6, LHX6, LHX7 | 2 |

| 113 | 19341725 | Hand2 | 1A |

| 114 | 12571099 | Hand2 | 1A |

| 115 | 12163415 | Msx1à BMP, shh | 1A, 1D |

| 116 | 15317890 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 117 | 12374769 | TBX22 | 3 |

| 118 | 20652317 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 119 | 21295280 | FAF1 | 6 |

| 120 | 21195053 | Sprouty-2/FGF | 1C |

| 121 | 21061289 | ATRA/BMP | 1A |

| 122 | 21058326 | Chlorcyclizine, H1 antag, Wnt, FGF, BMP | 1A, 1C,1E |

| 123 | 21041365 | ADAMTS9/20 | 9 |

| 124 | 21034733 | BMP | 1A |

| 125 | 20967564 | TGFB3 | 1A |

| 126 | 20945347 | TGFB3 | 1A |

| 127 | 20940229 | Fz | 1E |

| 128 | 20920724 | FGF10 | 1C |

| 129 | 20809987 | TGFB3 | 1A |

| 130 | 20727875 | BMP/Noggin | 1A |

| 131 | 20616530 | Twist1, Snai1 and Runx2 | 6 |

| 132 | 20506229 | JARID2 | 9 |

| 133 | 20451169 | RBM10 | 9 |

| 134 | 20424327 | P63/IRF6 | 2 |

| 135 | 20424318 | P63/IRF6 | 2 |

| 136 | 20196077 | IRF6 | 2 |

| 137 | 20165883 | RECK, MMP2/3/9 | 5 |

| 138 | 20133659 | FGFR2 | 1C |

| 139 | 20007998 | PRDM16/TGFβ | 1A |

| 140 | 19934017 | Msx1/Shh | 1A, 1D |

| 141 | 19782673 | Shh | 1D |

| 142 | 19769959 | TBX2/3 | 3 |

| 143 | 19676060 | p63 | 3 |

| 144 | 19653318 | Hoxa2/msx1/BMP | 1A |

| 145 | 19648291 | Tbx22 | 3 |

| 146 | 19598129 | Wnt | 1E |

| 147 | 19415673 | TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 148 | 19394325 | Shh | 1D |

| 149 | 19388084 | Smad2/3, RA | 2, 6 |

| 150 | 19097194 | Pkdcc | 8 |

| 151 | 18948417 | Wnt | 1E |

| 152 | 18816854 | Gli3 | 2 |

| 153 | 18697225 | TGFβ/twist | 1A |

| 154 | 18694570 | TGFβ/Smad | 1A, 2 |

| 155 | 18483623 | Pax3/BMP | 1A |

| 156 | 18470539 | Zfhx1a/TGFβ | 1A |

| 157 | 18437907 | RA/BMP | 6, 1A |

| 158 | 17967447 | TGFβ | 1A |

| 159 | 17927973 | Menin, Pax3, Wnt | 6, 1D |

| 160 | 17586487 | Tshz1 | 2 |

| 161 | 17520166 | Eh (hairy ears) Hoxc5 | 9 |

| 162 | 17337617 | MYH9 | 6 |

| 163 | 17293880 | GSK3β glycogen | 5 |

| 164 | 17028893 | Tbx3/BMP4 | 3, 1A |

| 165 | 17022082 | CBFB | 6 |

| 166 | 16761282 | Runx3/TGFβ/BMP | 1A |

| 167 | 16751186 | Fidgetin/ATPase, AKAP95 | 4 |

| 168 | 16546851 | Sox9 | 6 |

| 169 | 16410076 | atRA/TGFb/Smad | 1A, 2 |

| 170 | 16330189 | Msx/BMP | 1A |

| 171 | 16313756 | BMP | 1A |

| 172 | 16199551 | PHF8 | 2 |

| 173 | 16028273 | FGF twist, snail/BMP ID1 | 1C, 1A, 6 |

| 174 | 16026545 | TGFβ2 | 1A |

| 175 | 15914589 | twist, snail and E-cadherin | 6, 4 |

| 176 | 15649471 | Smad/TGFβ | 1A, 2 |

| 177 | 15282310 | Sall3 | 2 |

| 178 | 15175245 | Osr2, Pax9, TGFβ3 | 1A |

| 179 | 15162512 | Fgf8 | 1C |

| 180 | 14761683 | PKA pathway | 8 |

| 181 | 14702176 | iNOS, BMP | 1A |

| 182 | 14691138 | TGFβ | 1A |

| 183 | 14643678 | Zfhep | 6 |

| 184 | 12666199 | Decorin, biglycan | 5 |

| 185 | 12666195 | Tbx22 | 3 |

| 186 | 12606284 | GABA(a) β3 | 6 |

| 187 | 12388835 | PKA | 8 |

| 188 | 12204278 | Tbx22 | 3 |

| 189 | 12203737 | Titf2/foxe, TTF2 fork | 2 |

| 190 | 12175701 | CRE B, phosphotase | 8 |

| 191 | 12086327 | Lhx6 | 2 |

| 192 | 11969262 | RA/BMP | 1A, 6 |

| 193 | 11795938 | EGFR | 1A |

| 194 | 11669453 | TGFβ/RA | 1A |

| 195 | 11354513 | CREB, cAMP | 8 |

| 196 | 11330859 | Twist, Fgfr | 1C |

| 197 | 10789828 | Hoxa-2 | 1A |

| 198 | 10669089 | TSP-2/TGFβ | 1A |

| 199 | 21246652 | Ephrins | 8 |

| 200 | 20333300 | GABA, GAD1, Viaat | 6 |

| 201 | 20213699 | Shh | 1D |

| 202 | 19235875 | Fgfr2 | 1C |

| 203 | 18176224 | Fgfr2 | 1C |

| 204 | 16712891 | MAPK | 8 |

| 205 | 15543606 | PDGFRα | 1B |

| 206 | 12011971 | TGFβ, RhoA | 1A |

| 207 | 11238884 | DIg, SAP97 | 6 |

Table 2.

Summary of molecular pathways

| Pathway Studied | Number of Studies | Percent of Studies | |

| Extracellular signaling factors | TGFβ superfamily: TGFα, TGFβ, EGFR, Msx1, BMP, Activns, Hand2 | 71 | 30.1% |

| Platelet derived growth factor: PDGF-C | 8 | 3.4% | |

| Fibroblast growth factor: FGF | 21 | 8.9% | |

| Sonic Hedgehog: Shh, PTCH, SMO, CBP | 13 | 5.5% | |

| WNT: Wnt, Dv, Fz | 13 | 5.5% | |

| Total: | 126 | 53.4% | |

| Transcription Factors | FFAP2a, AP-2a, IR F6, FOXE1, TTF-2, GLI, SMAD1, Mnt, Phf8 | 31 | 13.1% |

| T-box Transcription Factors/Protein Modification | TBX22, TBX1, TBX10, Mn1, SUMO, p63, SATB2 | 17 | 7.2% |

| Cell adhesion molecules | PVRL1, Nectin, Integrin, E-cadherin, Desmosomal protein, Crk | 10 | 4.2% |

| Extracellular Matrix | Collagen, GAG, CSPG, HA, MMP | 8 | 3.4% |

| Other Factors | Jag, Notch, GABA, RA, Snai1, Snai2, Runx2, Meox, Pax1, Pax3, PDS5B, FAF, Sox9, MYH9, Zfhep, DIg | 27 | 11.4% |

| Cholesterol Pathway | Sterol, Insig 1, Insig 2 | 2 | 0.85% |

| Kinase Cascades | NAT2, MAPK, CRE B, PKA, camp, Eph, RTK, p57Kip2 | 10 | 4.2% |

| Genes | JARID2, ADAMTS9/20, TFAP2A, RBM10, Hoxc5 | 5 | 2.1% |

Table 3.

Summary of animal models used for palate study

| Animal Type | % of studies |

| Mouse | 156/166 = 94.0% |

| Chicken | 4/166 = 2.4% |

| Zebrafish | 3/166 = 1.8% |

| Rat | 3/166 = 1.8% |

Although advances have been made in identifying the genetic causes for some syndromic forms of cleft palate, etiology of the more common non-syndromic forms remains poorly characterized.1 Using various experimental approaches, researchers are now uncovering the molecules and cellular processes that can go awry in cases of palatal clefting.1 Exploring each pathway in detail is beyond the scope of this review; however, herein, we review those pathways most commonly found to be aberrant in the onset of cleft palate.

PDGF signaling.

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptors (PDGFRα and -β) have specific roles in promoting tissue-tissue interactions to control cell migration, proliferation and survival during embryonic development.14 Deletion of Pdgfrα in the neural crest leads to defects in palatal fusion, nasal septation and abnormal development of several facial bones and cartilage structures in mouse models.14 Deletion of Pdgfa and Pdgfc also produce severe craniofacial phenotypes. Pdgfc-null neonates have a complete cleft of the secondary palate, accompanied by failure of the palatal bones to extend across the roof of the oronasal cavity. Compound deletions lead to more severe phenotypes, for example, Pdgfc/Pdgfa double-knockout embryos develop a cleft face with cranial bone defects.15

Wingless type (Wnt) protein signaling.

Wnt signaling regulates numerous developmental processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation and survival.16 Wnt signaling also plays an important role in the generation and migration of neural crest cells and the development and patterning of the embryonic face in various species.17–19 Several members of the Wnt family, including ligands, receptors and co-receptors are expressed in the developing facial prominences.20–22 Wnt pathway activity is specifically localized to facial epithelia and underlying mesenchyme in the lateral nasal, maxillary and mandibular prominences.17 The hypothesized role for Wnt activity in the facial prominences varies within different tissues. In neural crest mesenchyme, Wnts promote proliferation, thus promoting the growth of the maxillary prominences that come together to form the palate.17 In the facial epithelium, expression of multiple Wnts is essential for the fusion of facial prominences.22–24 Onset of clefting is linked to disruptions in various Wnt genes,25–27 and perturbations of the pathway produce mild to severe facial clefting in various animal models17,24 as well as in humans.28 For example, mutation of Wnt9b in mice leads to cleft lip and palate and the A/Wysn strain of mice, which have an insertional mutation near the Wnt9b locus, have an increased incidence of spontaneous cleft lip and palate.29 Furthermore, aberrant expression of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6, Lrp6, a Wnt pathway coreceptor, also results in cleft lip and palate.24

Our laboratory has studied cleft palates present in both the Indian Hedghehog-null mutant as well as the GSK-3β-null mutant. In both of these models, we noted an obvious cleft in the secondary hard palate, which we believe is caused by dysregulated Wnt and Hedgehog signaling. Previous studies have shown that increase in canonical Wnt30 or decrease in Hedgehog signaling31 result in inhibited ossification. These reports suggest that increased Wnt signaling, such as that observed in the GSK-3β-null embryo, act to inhibit the ossification program already in place.32

BMP signaling.

Bone Morphogenic Protein (BMP) signaling participates in the induction, formation, determination and migration of the cranial neural crest cells which give rise to most of the craniofacial structures. Subsequently, it is also important for patterning and formation of facial primordia. In mice, loss-of-function type I BMP receptor (Bmpr1a) mutations in the craniofacial primordia results in cleft lip and palate. Interestingly, deficiency of Bmp4 ligand alone resulted in cleft lip only.33 Furthermore, downstream targets within the BMP pathway also have a link to cleft palate. Mutations in the mouse homeobox gene Msx1 results in cleft palate, and this represents a potential model on which to study cleft palate development.34

TGFβ3.

TGFβ3 is a member of the TGFβ superfamily and is expressed by medial edge epithelial (MEE) cells just prior to fusion of the palatal shelves. TGFβ3 is required for palatal shelf fusion,35,36 as evidenced by homozygous null TGFβ3 newborns, which exhibit a cleft secondary palate.37 Furthermore, administration of anti-TGFβ3 antibodies prevents fusion of the palatal shelves.38 Data suggest the role for TGFβ3 in palatogenesis relates to regulation of the breakdown of epithelia that lie between the palatal shelves. In the TGFβ3-null mice, the palatal shelves appear to approximate and adhere, but the epithelial seam remains, thus preventing fusion. Further support for the role of TGFβ3 during palatal fusion comes from biochemical approaches.

FOXE1 (Forkhead box protein E1).

FOXE1 is a forkhead-containing transcription factor that is involved in embryonic pattern formation. The FOXE1 gene is expressed at the point of fusion between maxillary and nasal processes during palatogenesis.39 Positional cloning and candidate gene sequencing show a correlation between mutations in FOXE1 and the occurrence of cleft lip and palate.39 FOXE1 is expressed in the secondary palate epithelium of both mice40 and human embryos.41 Furthermore, mice with a null mutation in FOXE1 have cleft palates.42

Irf (Interferon regulatory factor).

Irf6 is a member of a large family of transcription factors that bind to specific DNA sequences and regulate gene expression. In mice, disruption of this gene results in clefting.43,44 In humans, mutations in IRF6 have been shown to cause Van Der Woude syndrome and popliteal ptyergium syndrome, two disorders that are characterized by the presence of a cleft palate.45 Furthermore, variations in IRF6 have been found to increase the risk for isolated cleft lip and palate.46 Irf6 mutant mice exhibit a hyper-proliferative epidermis that fails to undergo terminal differentiation, causing epithelial adhesions that occlude the oral cavity and result in cleft palate.43,44 Taken together, these data suggest Irf6 mutations may result in defective elevation of palatine shelves, secondary to inappropriate adhesions with oral epithelium.

VAX1.

VAX1 is a member of the Emx/Not gene family and encodes a transcriptional regulator with a DNA-binding homeobox domain. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in VAX1 have been found to be overrepresented in patients with cleft lip and palate, suggesting that variants in VAX1 itself may contribute to development of clefting (reviewed in Dixon et al. 2011). Mouse knockouts for Vax1 show cleft palates, and this gene is expressed widely in developing craniofacial structures.47 Therefore, variants in VAX1 are strong candidates in the etiopathogenesis of cleft lip and palate.

Teratogen-induced cleft palate.

Along with pathway manipulation, scientists have also exposed genetically susceptible mouse strains such as C57B/L in utero to teratogens such as phenytoin, corticosteroids and retinoic acid.48 Such manipulations are thought to create a cleft due to alterations in mucopolysaccharides and glycosaminoglycans in the developing mesenchyme.

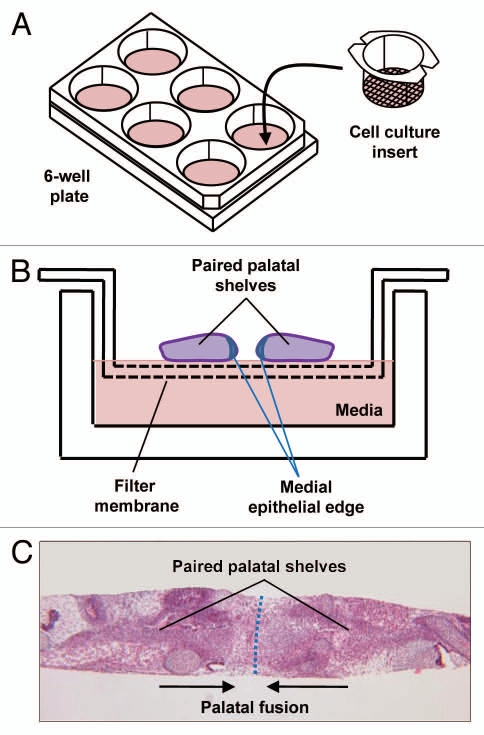

Alternative models.

Though transgenic models offer significant insight, it is difficult to manipulate the development of these mice in utero. Thus, palate organ cultures represent another promising methodology that allows direct manipulation of the palatal mesenchyme. In vitro chick palate models have been previously reported, and our laboratory has utilized a similar in vitro model using palates from E13.5 mice (Fig. 3). In our model, palate cultures are maintained for up to 96 h, and fusion is seen as early as 72 h. This model allows us to assess the critical distance needed for palates to be separated before clefting occurs. In addition, effects of various protein ligands on palatal gene expression can be studied.48,49 The disadvantage, of course, is that in vitro conditions do not completely mimic in vivo correlates, and thus palate cultures are better for analyzing pathways than morphogenesis.

Figure 3.

Palate cultures. (A) Schematic of palate culture using 6-well plate and insert with 0.4 µM pores allowing cytokines but not cells to pass through. (B) Schematic of paired palatal shelves in palate culture. (C) H&E stain of palatal fusion after 72 h of 2 palatal shelves in culture while in contact with each other.

Clinical Implications and Potential Therapies

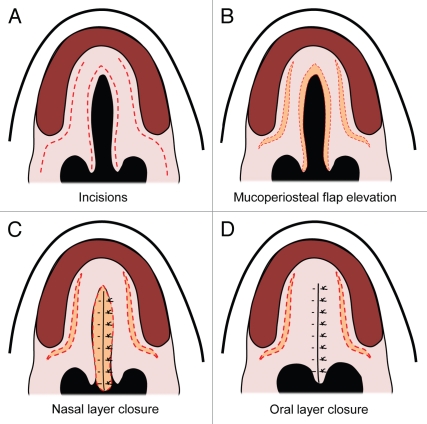

While research continues on the molecular genetics of cleft formation, surgery remains the mainstay for treatment of palatal defects. The first report of a cleft palate repair is attributed to LeMonnier, who incised the cleft edges and placed sutures leading to suppuration and then healing across the defect.6,50 Von Langenbeck later introduced the use of mucoperiosteal flaps to close clefts involving the hard palate (Fig. 4).9,50

Figure 4.

Von Langenbeck palatal repair. (A) Secondary cleft palate palate with dotted red lines demonstrating incisions. (B) Mucuoperiosteal flap elevation with orange demonstrating opening of the incisions. (C) Midline nasal closure of the defect with the nasal layer in orange. (D) Closure of the midline incision with the oral mucosa over the nasal layer closure.

A literature search of PubMed was performed to assess practice patterns of current surgical repair of cleft palates. The following search terms were used in combination to identify appropriate studies: Cleft palate, surgery, treatment and repair. The search for repair type was limited to studies published in English from 2000 to 2011 with a focus on patients within the age group 0–23 mo. Studies were excluded if the full text was inaccessible or surgical repair type was not clearly identified in the methods section. We found a wide variety of approaches used with a paucity of randomized controlled studies for any technique (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Procedure used for palate repair

| Article No. | PMID | Repair Type | Level Evidence |

| 1 | 11879069 | Furlow double opposing Z-plasty | 2 |

| 2 | 18827646 | Bardach two-flap | 3 |

| 3 | 16816695 | Bardach two-flap | 4 |

| 4 | 19443049 | Millard and two-flap | 3 |

| 5 | 12172182 | Two-flap | 4 |

| 6 | 15145666 | Furlow | 4 |

| 7 | 18594410 | Furlow w/vs. w/out islandization | 3 |

| 8 | 16799309 | Furlow | 4 |

| 9 | 16154317 | Vomer flap with push back | 3 |

| 10 | 18991170 | Secondary gingivoalveoloplasty | 3 |

| 11 | 12733955 | Furlow | 4 |

| 12 | 12142649 | Modified Langenbeck, Ernst, Veau and Axhausen technique | 3 |

| 13 | 14697077 | Wave-line technique | 2 |

| 14 | 18177196 | Square-flap method | 4 |

| 15 | 14663803 | Musculomucosal buccal flap | 4 |

| 16 | 17105319 | Mucoso-periosteal flap palatoplasty | 4 |

| 17 | 17105319 | Marginal musculo-mucosal flap | 2 |

| 18 | 16876078 | Modified z-plasty | 5 |

| 19 | 16077326 | Two-flap, V-Y, and dorrance with new adhesive | 5 |

| 20 | 11711920 | Von Langenbeck, Wardill-Kilner, | 4 |

| 21 | 16929186 | Furlow | 3 |

| 22 | 10029477 | Furlow | 4 |

| 23 | 15988251 | Veau-Wardill-Kilner | 4 |

| 24 | 15213528 | Furlow | 4 |

| 25 | 19165004 | Modified 2 flap | 2 |

| 26 | 10626963 | Push-back palatoplasty | 5 |

| 27 | 10839414 | Modified Furlow | 3 |

| 28 | 15896890 | Furlow | 4 |

| 29 | 16681406 | Vomerine flap and Von Langenbeck incisions | 2 |

| 30 | 20842387 | Vomer flap | 2 |

| 31 | 20413269 | Distraction osteogenesis (DO) vs. conventional orthognathic (CO) | 2 |

| 32 | 20335871 | Millard, Pfeifer, Afroze | 1 |

| 33 | 20299247 | CO vs. DO | 2? |

| 34 | 20227244 | Collagen membrane | 4 |

| 35 | 20163243 | Collagen matrix w/rhBMP-2 | 2 |

| 36 | 20048619 | No tensor transection, tensor transection alone and tensor tenopexy | 3 |

| 37 | 19816334 | Tennison, periosteoplasy, pushback | 4 |

| 38 | 17652050 | Von Langenbeck and Furlow | 3 |

| 39 | 17440366 | Wardill-Kilner vs. Kriens | 2 |

| 40 | 17328643 | Vomerine and Von Langenbeck | 2 |

| 41 | 17105327 | Von Langenbeck | 1 |

| 42 | 15861051 | Vomer, pushback, Von Langenbeck | 3 |

| 43 | 14577817 | Millard, Von Langenbeck | 2 |

| 44 | 12498603 | Modified Von Langenbeck | 2 |

| 45 | 11141029 | Millard, Von Langenbeck | 2 |

| 46 | 12846601 | Zurich, Von Langenbeck | 2 |

| 47 | 12846598 | Millard, Von Langenbeck | 2 |

Level 1, Prospective multi-center double blinded randomized control study; Level 2, Prospective randomized control study; Level 3, Retrospective analysis, case control study or systematic review of studies; Level 4, Case series; Level 5, Expert opinion, case report or clinical example.

Table 5.

Summary of procedures used for palate repair

| Level | % of studies at that level |

| 1 2/47 = 4.3% | |

| 2 | 16/47 = 34.0% |

| 3 | 11/47 = 23.4% |

| 4 | 15/47 = 31.9% |

| 5 | 3/47 = 6.4% |

Overall, the most widely used techniques include Von Langenbeck's, the Vaeu-Wardill-Kilner and the two-flap repair described by Bardach.6,51 While many modifications of each exist, the main principles across all cleft palate repairs include tension-free closure of the oral and nasal layers, dissection of muscles from the posterior edge of the hard palate and construction of a horizontally oriented palatal sling to restore normal velar function.51

Repair of the cleft palate begins with an incision along the cleft margin at the junction between oral and nasal mucosa. The incision is carried anteriorly along the gingiva, allowing elevation of mucoperiosteal flaps off the hard palate.10,51 With exposure of the greater palatine neurovascular bundle, mobilization can be performed by gentle stretching using scissors. The tendon of the tensor veli palatini can also be divided medial to the hamulus to facilitate medialization of the levator muscle.9 The nasal mucoperiosteum is then widely mobilized from the undersurface of the hard palate. Posteriorly, an intravelar veloplasty is typically performed, with separation of the oral, muscle and nasal linings and release of the muscles from their abnormal attachment to the posterior edge of the bony palate. Closure of the defect is performed in three layers (nasal mucosa, velar muscle and oral mucosa), with horizontal reorientation of the levator veli palatini establishing proper orientation of the sling. In the region of the hard palate, a two-layer repair is performed, with the nasal layer sometimes requiring a vomerine flap.6

In patients with either clefting of the soft palate or a submucous cleft, a Furlow palatoplasty can also be performed. Double opposing z-plasties are fashioned on the velum, with release of the levator muscle from the posterior edge of the hard palate.52 Transposition of the flaps yields retropositioning of the muscle to a more medial-lateral position.53 With this technique, simultaneous palatal lengthening and reconstruction of the levator sling is established along with additional narrowing of the nasopharyngeal aperture.11 Velopharyngeal competence allowing development of normal speech is one of the most critical outcomes in cleft surgery, and the Furlow technique has been associated with some of the lowest rates of persistent velopharyngeal insufficiency following primary repair.52–55

While techniques for cleft palate repair have become well-established, postoperative development of oronasal fistulas still remains a significant problem. Reports have noted an incidence ranging from 11% to 23%, with the most likely site being the junction of the hard and soft palates.56–59 Depending on size, fistulas may contribute to hypernasal speech, nasal regurgitation and food trapping. Several retrospective studies have identified the extent of cleft to be a significant factor, as patients with bilateral clefts were found to have a 2- to 3-fold higher incidence of postoperative fistula development compared with unilateral clefts.51,60 Operator experience has also been shown to play a role.58,60 Recent investigations have evaluated the utility of the buccal fat pad as adjunctive tissue for use in both primary palatal cleft repair and treatment of postoperative fistulas. Used in a pedicled fashion with overlying mucosa, the buccal fat pad has been shown to successfully treat wide oroantral and oronasal clefts.61,62 More recently, buccal fat has also been employed to cover laterally exposed bone adjacent to gingival mucosa following medialization of the mucoperiosteal flaps.63 As this was found to re-epithelialize within two weeks, use of the buccal fat pad may result in an eventual reduction of palatal scarring, which may limit subsequent growth restriction of the maxilla. And in similar fashion to AlloDerm, the buccal fat pad has also been shown to be effective as an interpositional layer between oral and nasal lining in the repair of postoperative fistulas.63 Fuimora et al. have even evaluated the utility of combining the two, with the successful treatment of oronasal fistulas using pedicled buccal fat covered with lyophilized dermis in adult patients.64

Palatal Tissue Engineering

The use of autogenous grafted material is now the standard of care, but tissue engineering is an attractive alternative that could greatly reduce the morbidity of surgery and potentially enhance the healing process. An exhaustive literature search only yielded 36 non-review studies discussing tissue engineering of the palate (Table 6). Of these 36 studies, 20 discussed engineering of the mucosa (Table 7). Regarding mucosal repair, cultured epithelial grafts, dermal substitutes and a combination of the two, called mucosa equivalents, are commonly used to provide extra tissue and aide in wound healing after cleft palate repair. Cultured epithelial grafts can provide coverage for large areas while being derived from only a small biopsy, but they are prone to infection and fail to reduce scarring or contraction in full-thickness wounds due to absence of a dermal component.65 Such grafts can be either allogenic or autologous. Allogenic grafts have the advantage of being readily available but have a low take rate and are generally only used for temporary coverage, while autologous grafts take require extra time to culture but have a higher take rate.

Table 6.

Recent studies of palatal tissue engineering

| Article no. | PMID | Tissue Engineered | Experimental model | Review? | Species |

| 1 | bone/mucosa | mouse/rat/human/in vitro | |||

| 2 | 21465220 | bone | ALL | review | ALL |

| 3 | 21282641 | mucosa | mouse | ALL | |

| 4 | 20863943 | bone | human | ALL | |

| 5 | 20676486 | bone | rat | ALL | |

| 6 | 20646804 | bone | in vitro (rat bone marrow) | ALL | |

| 7 | 20524191 | mucosa | human | ALL | |

| 8 | 20078790 | mucosa | ALL | review | ALL |

| 9 | 19615638 | bone | human | ALL | |

| 10 | 19473448 | mucosa | rat | ALL | |

| 11 | 18834238 | mucosa | human | Dog | |

| 12 | 19387150 | bone | in vitro | Dog | |

| 13 | 19184287 | bone | rat | Dog | |

| 14 | 19043190 | bone | human | human | |

| 15 | 19018060 | both | human | review | human |

| 16 | 18774917 | both | ALL | review | human |

| 17 | 18650554 | mucosa | in vitro | human | |

| 18 | 18520371 | mucosa | rat | human | |

| 19 | 18427300 | both | ALL | review | human |

| 20 | 18427291 | both | ALL | review | human |

| 21 | 18319673 | both | ALL | review | human |

| 22 | 18269029 | mucosa | rat | human | |

| 23 | 18206405 | bone | human | human | |

| 24 | 18093570 | mucosa | rat | human | |

| 25 | 18041711 | mucosa | in vitro | human | |

| 26 | 18022477 | both | ALL | review | human |

| 27 | 17971350 | mucosa | Dog | in vitro | |

| 28 | 17764402 | mucosa | Dog | in vitro | |

| 29 | 17667684 | bone | human | in vitro | |

| 30 | 17465023 | mucosa | in vitro | in vitro | |

| 31 | 17393689 | bone | Dog | in vitro | |

| 32 | 17346560 | both | ALL | review | in vitro |

| 33 | 16525276 | bone | rat | in vitro | |

| 34 | 15948680 | mucosa | human | in vitro | |

| 35 | 15927149 | bone | human | mouse | |

| 36 | 15894371 | mucosa | in vitro | mouse | |

| 37 | 15348479 | bone | rat | rat | |

| 38 | 14619596 | mucosa | rat | rat | |

| 39 | 14513576 | mucosa | rat | rat | |

| 40 | 12544232 | bone | mouse | rat | |

| 41 | 12109699 | mucosa | in vitro | rat | |

| 42 | 11896993 | mucosa | in vitro | rat | |

| 43 | 11213985 | mucosa | human | rat | |

| 44 | 11203575 | bone | human | rat | |

| 45 | 10845305 | both | ALL | review | rat |

| 46 | 9821920 | mucosa | human | rat |

Table 7.

Summary of tissues described in tissue engineering of the palate

| Mucosa = 20/36 | 0.555 = 55.5% |

| Bone = 16/36 | 0.44 = 44% |

Dermal substitutes made from polymers, purified collagen or de-epidermized dermis (DED or AlloDerm) provide additional physical support that is often lacking in epithelial grafts. However, some require a secondary procedure to apply a split-thickness skin graft or cultured epithelia. In recent years, repair of palatal fistulas have begun to employ acellularized dermal matrix (AlloDerm) with promising results. Using AlloDerm as an interpositional layer between nasal and oral mucoperiosteum has been shown to significantly reduce fistula recurrence rates in multiple series.66,67 Furthermore, recent studies have also demonstrated the utility of AlloDerm as an adjunctive measure in the primary repair of wide clefts. In a series of seven patients with palatal clefts wider than 15 mm, placement of AlloDerm between the muscle and oral lining was found to result in the development of no postoperative fistulas.68 Even in two patients with oral dehiscence and exposure of the AlloDerm, uneventful healing proceeded, with remucosalization occurring over a 4-week follow-up.68

Cultured mucosa equivalents provide an epithelial and dermal substitute in a one-step process, which seem to be the optimal replacement for mucosa, since this provides material for repair with properties closest to the original tissue. However, long-term evaluation of their clinical efficacy is still lacking. Tissue engineering using epithelial and mesenchymal stem cells could greatly enhance these options for repair once characterization and isolation of true stem cells can be routinely achieved.

The other tissue discussed in 20 of the 36 palatal tissue engineering articles was palatal bone (Table 7). In cleft palate repair, one of the major challenges lies in reconstructing the bony hard palatal and alveolar defects. Surgical repair with autogenous bone grafts is the current standard of care. Bone is most commonly harvested from the iliac crest but can be taken from the rib, tibia, calvarium or mandibular symphysis. This often requires multiple operations and extensive healing time and is associated with high donor site morbidity, including postoperative pain, altered sensation, scarring and infection. In addition, bone graft harvest ultimately yields a very limited quantity of bone for reconstruction. Furthermore, this bone often does not fully integrate into the host site and can undergo some resorption. Bony repair needs to be very strong to support tooth eruption and to withstand physical stress from muscles of mastication. There are also allogeneic and synthetic material available for grafting, and while these solve the problem of donor site morbidity, there is still the risk of infection, elicitation of an immune response and problems with structural integrity and contour.69

The use of tissue engineering could avoid many disadvantages of autogenous grafting, such as donor site morbidity, and could potentially decrease the number of surgeries needed while providing improved outcomes. Only a limited number of studies currently exist exploring palatal tissue engineering, and of these studies, only 36% pertain to human subjects, making it an attractive avenue for future research endeavors (Table 8).

Table 8.

Summary of animal models in studies discussing tissue engineering of the palate

| Dog = 8.3% |

| Human = 36% |

| In Vitro = 22% |

| Mouse = 5.5% |

| Rat = 27.8% |

Conclusion

Craniofacial clefts, specifically clefting of the lip and palate, remain a significant biomedical burden. Therefore, understanding normal palate development as well as aberrant pathways involved in abnormal palate development is crucial to allow us to better develop therapeutic modalities to treat these patients. Clearly, despite an improvement in surgical outcomes, there is a paucity of randomized controlled studies (level I data), leading surgeons to depend on clinical reports and non-randomized trials, which are often misleading. The current gold standard for treating cleft palate patients involves a team approach between plastic surgeons, pediatricians, otolaryngologists, speech pathologists, orthodontists and geneticists, underscoring the myriad of complications caused by CLP beyond just the tissue deficit. Thus, identifying the major pathways involved and manipulating those pathways prior to birth would represent a monumental step to prevent the primary and many secondary complications caused by CLP. Tissue engineering approaches also remain an exciting and potentially profitable direction of investigation as the field of regenerative medicine advances.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant 1R21DE018727-01, the Oak Foundation and Hagey Laboratory for Pediatric Regenerative Medicine and the National Endowment for Plastic Surgery to M.T.L. B.L. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant 1F32AR057302.

Financial Disclosure

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:167–178. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robin NH, Baty H, Franklin J, Guyton FC, Mann J, Woolley AL, et al. The multidisciplinary evaluation and management of cleft lip and palate. South Med J. 2006;99:1111–1120. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000209093.78617.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser FC. Thoughts on the etiology of clefts of the palate and lip. Acta Genet Stat Med. 1955;5:358–369. doi: 10.1159/000150783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gritli-Linde A. The etiopathogenesis of cleft lip and cleft palate: usefulness and caveats of mouse models. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;84:37–138. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang R, Bush JO, Lidral AC. Development of the upper lip: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1152–1166. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thaller SR, Bradley JP, Garri JI. Craniofacial Surgery. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowitz S. Stereophotogrammetric analysis of casts of normal and abnormal palates. Am J Orthod. 1971;60:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(71)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommerlad BC, Fenn C, Harland K, Sell D, Birch MJ, Dave R, et al. Submucous cleft palate: a grading system and review of 40 consecutive submucous cleft palate repairs. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:114–123. doi: 10.1597/02-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorne CH, Bartlett SP, Beasley R, Aston S, Gurtner GC, Spear SL. Grabb & Smith's Plastic Surgery. Philadelpha, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardach J. Atlas of Craniofacial and Cleft Surgery: Cleft Lip and Palate. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 1999. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noorchashm N, Dudas JR, Ford M, Gastman B, Deleyiannis FW, Vecchione L, et al. Conversion Furlow palatoplasty: salvage of speech after straight-line palatoplasty and “incomplete intravelar veloplasty”. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:505–510. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000210154.72830.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriens OB. An anatomical approach to veloplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:29–41. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardill WEM. The technique of operation for cleft palate. Br J Surg. 2005;25:117. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800259715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoch RV, Soriano P. Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development. 2003;130:4769–4784. doi: 10.1242/dev.00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding H, Wu X, Boström H, Kim I, Wong N, Tsoi B, et al. A specific requirement for PDGF-C in palate formation and PDGFRalpha signaling. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/ng1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3286–3305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Gregorieff A, Leucht P, ten Berge D, Fuerer C, et al. Wnt signaling mediates regional specification in the vertebrate face. Development. 2007;134:3283–3295. doi: 10.1242/dev.005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basch ML, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest inducing signals. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:24–31. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-469546_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt C, Patel K. Wnts and the neural crest. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;209:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oosterwegel M, van de Wetering M, Timmerman J, Kruisbeek A, Destree O, Meijlink F, et al. Differential expression of the HMG box factors TCF-1 and LEF-1 during murine embryogenesis. Development. 1993;118:439–448. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Shackleford GM. Murine Wnt10a and Wnt10b: cloning and expression in developing limbs, face and skin of embryos and in adults. Oncogene. 1996;13:1537–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geetha-Loganathan P, Nimmagadda S, Antoni L, Fu K, Whiting CJ, Francis-West P, et al. Expression of WNT signalling pathway genes during chicken craniofacial development. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1150–1165. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan Y, Ryan RC, Zhang Z, Bullard SA, Bush JO, Maltby KM, et al. Expression of Wnt9b and activation of canonical Wnt signaling during midfacial morphogenesis in mice. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1448–1454. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song L, Li Y, Wang K, Wang YZ, Molotkov A, Gao L, et al. Lrp6-mediated canonical Wnt signaling is required for lip formation and fusion. Development. 2009;136:3161–3171. doi: 10.1242/dev.037440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, Mah DG. The clf1 gene maps to a 2- to 3-cM region of distal mouse chromosome 11. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:789. doi: 10.1007/s003359900298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, Brown CJ. Unravelling the complex genetics of cleft lip in the mouse model. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:426–435. doi: 10.1007/s003350010284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, Dewell SL, Brown CJ, Mager DL, Gagnier L, et al. Investigations of the genomic region that contains the clf1 mutation, a causal gene in multifactorial cleft lip and palate in mice. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:103–113. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiquet BT, Blanton SH, Burt A, Ma D, Stal S, Mulliken JB, et al. Variation in WNT genes is associated with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2212–2218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, McMahon AP, Carroll TJ, Lidral AC. Wnt9b is the mutated gene involved in multifactorial nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in A/WySn mice, as confirmed by a genetic complementation test. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:574–579. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behr B, Longaker MT, Quarto N. Differential activation of canonical Wnt signaling determines cranial sutures fate: a novel mechanism for sagittal suture craniosynostosis. Dev Biol. 2010;344:922–940. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2072–2086. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu KJ, Arron JR, Stankunas K, Crabtree GR, Longaker MT. Chemical rescue of cleft palate and midline defects in conditional GSK-3beta mice. Nature. 2007;446:79–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Song Y, Zhao X, Zhang X, Fermin C, Chen Y. Rescue of cleft palate in Msx1-deficient mice by transgenic Bmp4 reveals a network of BMP and Shh signaling in the regulation of mammalian palatogenesis. Development. 2002;129:4135–4146. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satokata I, Maas R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat Genet. 1994;6:348–356. doi: 10.1038/ng0494-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, et al. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelton RW, Saxena B, Jones M, Moses HL, Gold LI. Immunohistochemical localization of TGF-beta1, TGF-beta2 and TGF-beta3 in the mouse embryo: expression patterns suggest multiple roles during embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1091–1105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunet CL, Sharpe PM, Ferguson MW. Inhibition of TGF-beta3 (but not TGF-beta1 or TGF-beta2) activity prevents normal mouse embryonic palate fusion. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39:345–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreno LM, Mansilla MA, Bullard SA, Cooper ME, Busch TD, Machida J, et al. FOXE1 association with both isolated cleft lip with or without cleft palate and isolated cleft palate. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4879–4896. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dathan N, Parlato R, Rosica A, De Felice M, Di Lauro R. Distribution of the titf2/foxe1 gene product is consistent with an important role in the development of foregut endoderm, palate and hair. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:450–456. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trueba SS, Augé J, Mattei G, Etchevers H, Martinovic J, Czernichow P, et al. PAX8, TITF1 and FOXE1 gene expression patterns during human development: new insights into human thyroid development and thyroid dysgenesis-associated malformations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:455–462. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Felice M, Ovitt C, Biffali E, Rodriguez-Mallon A, Arra C, Anastassiadis K, et al. A mouse model for hereditary thyroid dysgenesis and cleft palate. Nat Genet. 1998;19:395–398. doi: 10.1038/1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson RJ, Dixon J, Malhotra S, Hardman MJ, Knowles L, Boot-Handford RP, et al. Irf6 is a key determinant of the keratinocyte proliferation-differentiation switch. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1329–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingraham CR, Kinoshita A, Kondo S, Yang B, Sajan S, Trout KJ, et al. Abnormal skin, limb and craniofacial morphogenesis in mice deficient for interferon regulatory factor 6 (Irf6) Nat Genet. 2006;38:1335–1340. doi: 10.1038/ng1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little HJ, Rorick NK, Su LI, Baldock C, Malhotra S, Jowitt T, et al. Missense mutations that cause Van der Woude syndrome and popliteal pterygium syndrome affect the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation functions of IRF6. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:535–545. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanton SH, Cortez A, Stal S, Mulliken JB, Finnell RH, Hecht JT. Variation in IRF6 contributes to nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Am J Med Genet. 2005;137:259–262. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallonet M, Hollemann T, Pieler T, Gruss P. Vax1, a novel homeobox-containing gene, directs development of the basal forebrain and visual system. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3106–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erfani S, Maldonado TS, Crisera CA, Warren SM, Lee S, Longaker MT. An in vitro mouse model of cleft palate: defining a critical intershelf distance necessary for palatal clefting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:403–410. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200108000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levi B, James AW, Nelson ER, Brugmann SA, Sorkin M, Manu A, et al. Role of Indian hedgehog signaling in palatal osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1182–1190. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182043a07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langenbeck B. Operation on congenital total cleft of the hard palate by a new method. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bardach J. Two-flap palatoplasty: Bardach's technique. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;2:211–214. doi: 10.1016/S1071-0949(06)80034-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furlow LT., Jr Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:724–738. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198678060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirschner RE, Wang P, Jawad AF, Duran M, Cohen M, Solot C, et al. Cleft-palate repair by modified Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1998–2010. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta R, Kumar S, Murarka AK, Mowar A. Some modifications of the furlow palatoplasty in wide clefts-a preliminary report. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:9–19. doi: 10.1597/09-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LaRossa D, Jackson OH, Kirschner RE, Low DW, Solot CB, Cohen MA, et al. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia modification of the Furlow double-opposing z-palatoplasty: long-term speech and growth results. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31:243–249. doi: 10.1016/S0094-1298(03)00141-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amaratunga NA. Occurrence of oronasal fistulas in operated cleft palate patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:834–838. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen SR, Kalinowski J, LaRossa D, Randall P. Cleft palate fistulas: a multivariate statistical analysis of prevalence, etiology and surgical management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1041–1047. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emory RE, Jr, Clay RP, Bite U, Jackson IT. Fistula formation and repair after palatal closure: an institutional perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1535–1538. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Landheer JA, Breugem CC, van der Molen AB. Fistula incidence and predictors of fistula occurrence after cleft palate repair: two-stage closure versus one-stage closure. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47:623–630. doi: 10.1597/09-069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu Y, Shi B, Zheng Q, Hu Q, Wang Z. Incidence of palatal fistula after palatoplasty with levator veli palatini retropositioning according to Sommerlad. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:637–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hai HK. Repair of palatal defects with unlined buccal fat pad grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:523–525. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hudson JW, Anderson JG, Russell RM, Jr, Anderson N, Chambers K. Use of pedicled fat pad graft as an adjunct in the reconstruction of palatal cleft defects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:24–27. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(95)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levi B, Kasten SJ, Buchman SR. Utilization of the buccal fat pad flap for congenital cleft palate repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1018–1021. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199f80f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fujimura N, Nagura H, Enomoto S. Grafting of the buccal fat pad into palatal defects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990;18:219–222. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu J, Bian Z, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Von den Hoff JW. Skin and oral mucosa equivalents: construction and performance. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010;13:11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.16016343.2009.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steele MH, Seagle MB. Palatal fistula repair using acellular dermal matrix: the University of Florida experience. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:50–53. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000185469.80256.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cole P, Horn TW, Thaller S. The use of decellularized dermal grafting (AlloDerm) in persistent oro-nasal fistulas after tertiary cleft palate repair. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:636–641. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clark JM, Saffold SH, Israel JM. Decellularized dermal grafting in cleft palate repair. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:40–44. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.5.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, Slater BJ, Kwan MD, Liu KJ, Longaker MT. Tissue engineering in cleft palate and other congenital malformations. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:545–551. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816a743e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]