Abstract

The major concern for anticancer chemotherapeutic agents is the host toxicity. The development of anti-cancer prodrugs targeting the unique biochemical alterations in cancer cells is an attractive approach to achieve therapeutic activity and selectivity. We designed and synthesized a new type of nitrogen mustard prodrug that can be activated by high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) found in cancer cells to release the active chemotherapy agent. The activation mechanism was determined by NMR analysis. The activity and selectivity of these prodrugs towards ROS was determined by measuring DNA interstrand crosslinks and/or DNA alkylations. These compounds showed 60–90% inhibition toward various cancer cells, while normal lymphocytes were not affected. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of H2O2-activated anticancer prodrugs.

Keywords: Interstrand crosslink, H2O2-activation, anticancer prodrug, ROS-targeting, arylboronate and arylboronic acid

DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) are deleterious to cells, because they are unyielding obstruction to replication and transcription.1 This property is exploited in cancer chemotherapy. ICL-inducing agents such as nitrogen mustards and cisplatin are among the most frequently used antitumor agents in the clinic. However, these agents exhibit severe host toxicity due to their poor selectivity toward cancer cells. One approach to reduce the toxicity of crosslinking agents for normal cells is to trigger the prodrug in tumor cells. Over the past few decades, several research groups have developed novel DNA cross-linking or alkylating agents that can induce ICL formation either by oxidation, reduction, or photolysis.2–4 However, there is considerable scope for developing selective agents that can induce DNA crosslinks specifically under tumor-specific conditions. It is believed that the estrogen receptor (ER) is overexpressed in many human breast and ovarian tumors. Essigmann and coworkers have developed tumor-specific toxins by conjugating an ER ligand with a DNA damaging nitrogen mustard or a bifunctional platinum (II) complex to achieve the selective killing of tumor cells while minimizing toxicity to normal tissues.5 Cancer cells are also known to exhibit elevated intrinsic oxidative stress.6–9 The increased amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be a therapeutic advantage, because it is an exclusive feature of cancer cells.9 Therefore, it is of great interest to develop cross-linking agents that can be activated by ROS found in tumor cells and induce deleterious DNA damages (e.g. ICL formation or alkylation).

The most common ROS include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2·−), and hydroxyl radical. Among these, H2O2 has the chemical stability required to establish significant steady-state concentrations in vivo and is uncharged. Compared with their normal counterparts, cancer cells have increased level of H2O2 (up to 0.5 nmol/104 cells/h).6,10 These factors make H2O2 an ideal candidate as a therapeutic target for the development of ROS-activated prodrugs. Such agents should consist of two separate functional domains: a H2O2-accepting moiety (‘trigger’) and an ‘effector’, joined by a linker system in such a way that the reaction of the trigger with H2O2 causes a large increase in the cytotoxic potency of the effector. The aryl boronic acids and their esters are well known to be cleaved by H2O2.11 This reactivity provides a chemospecific, biologically compatible reaction method for detecting endogenous H2O2 production. Chang’s group has used boronic esters for the development of H2O2-activated fluorescent probes for imaging H2O2 in cells.12 Boronic acids and esters do not appear to have intrinsic toxicity issues, and the end product, boric acid, is considered non-toxic to humans.13 All of this information encouraged us to use aryboronates or boronic acids as the trigger units for the development of H2O2-activated anticancer prodrugs. We chose nitrogen mustard as the effector to create a more broadly-applicable strategy. Therefore, we designed and synthesized prodrugs of nitrogen mustards (1 and 2), investigated their inducible reactivities, and compared these activities with their analogs 3 and 4.

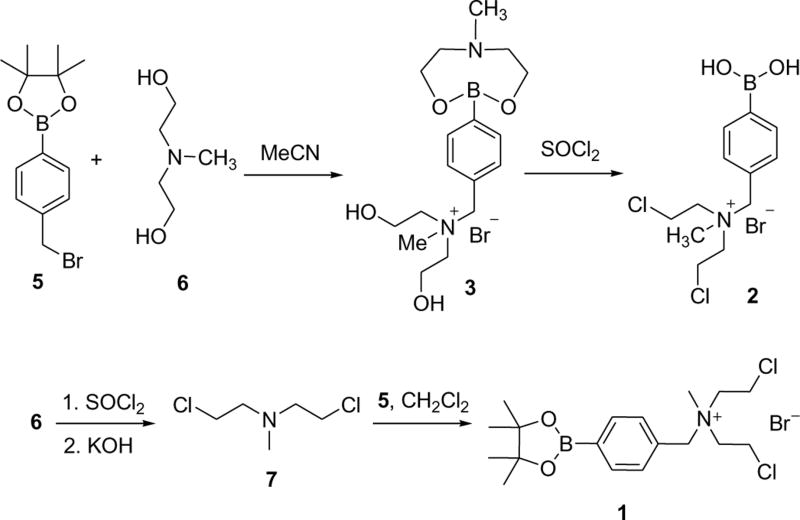

Compounds 1–3 were synthesized starting from 4-(bromomethyl)phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (5) (Scheme 1). Treatment of 5 with N-methyldiethanolamine yielded 3, which was converted to 2 by using thionyl chloride. Compound 1 was prepared by the reaction of 5 with N, N-bis(2-chloroethyl)methyl ammine (7, HN2). In a similar way, 4 was synthesized (Supporting Information (SI), Scheme S2).

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of 1–3.

It was known that the ICLs are the source of the cytotoxicity of nitrogen mustards. Thus, the activity of 1 and 2 was investigated by determining their ability to form DNA interstrand crosslinks using a 49 mer DNA duplex 8. The DNA cross-linking experiments were carried out in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.5). ICL formation and crosslinking yield were analyzed via denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with phosphorimager analysis (Image Quant 5.2) by taking advantage of the differing mobilities of ICL products and single stranded DNA. In the absence of H2O2, no ICL was observed with 1 and 2 (Figure 1, lane 2 and 10), which indicates the toxicity of nitrogen mustard mechlorethamine (7) is masked in the prodrugs. When 8 was treated with 1 or 2 in the presence of H2O2, efficient crosslink formation was observed (11–43%) (Figure 1, lanes 5–9 and 13–17). DNA crosslinking by 1 and 2 was observed at a concentration of H2O2 as low as 50 μM (lanes 3 and 11). This clearly shows that 1 and 2 are non-toxic to DNA, but can be activated by H2O2 to release the DNA damaging agent 7. The best ratio of drug to H2O2 is 2:1 (SI, Figure S1). ICL growth followed first-order kinetics. The observed rate constant for ICL formation induced by 1 (kICL = (4.6 ± 0.4) × 10−5 s−1, t1/2 = 4.2 h) was within experimental error of that induced by 2 (kICL = (4.7 ± 0.3) × 10−5 s−1, t1/2 = 4.1 h) (SI, Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Concentration dependence of compounds 1 and 2 for DNA cross-link formation upon H2O2-activation. Lane 1 without drug; lanes 2–9 with drug 1: lane 2 without H2O2 (cross-linking yield 0%); lane 3: 50 μM H2O2 + 100 μM 1 (2.2%); lane 4: 100 μM H2O2 + 200 μM 1 (5%); lane 5: 250 μM H2O2 + 500 μM 1 (11%); lane 6: 500 μM H2O2 + 1.0 mM 1 (18%); lane 7: 1.0 mM H2O2 + 2.0 mM 1 (28%); lane 8: 1.5 mM H2O2 + 3.0 mM 1 (36%); lane 9: 2.0 mM H2O2 + 4.0 mM 1 (42%); lanes 10–17 with drug 2: lane 10 without H2O2 (0%); lane 11: 50 μM H2O2 + 100 μM 2 (2.0%); lane 12: 100 μM H2O2 + 200 μM 2 (4%); lane 13: 250 μM H2O2 + 500 μM 2 (11%); lane 14: 500 μM H2O2 + 1.0 mM 2 (17%); lane 15: 1.0 mM H2O2 + 2.0 mM 2 (27%); lane 16: 1.5 mM H2O2 + 3.0 mM 2 (35%); lane 17: 2.0 mM H2O2 + 4.0 mM 2 (43%).

As H2O2 is not the only ROS in biological system, we studied the inducible activity of 1 and 2 towards other ROS, such as tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP), hypochlorite (OCl−), hydroxyl radical, tert-butoxy radical, superoxide (O2 −), and nitric oxide. The activation of 1 and 2 to release nitrogen mustard is highly selective for H2O2 over other ROS, which is demonstrated by the selective ICL formation (Figure 2 and SI, Figure S3). In the presence of H2O2, compounds 1 and 2 induced efficient ICL formation (35%), while less than 5% ICLs were observed with other ROS. The selective reaction of phenylboronate or boronic acid derivatives (1 and 2) with H2O2 is consistent with the observation of Chang’s group.12e

Figure 2.

ICL formation induced by 1 and 2 (2 mM) upon treatment with various reactive oxygen species (ROS) at 1 mM (black bar – compound 1; grey bar –compound 2).

In order to provide further insight into the reactivity of 1 and 2, we examined the stability and reactivity of purified ICL products and single stranded DNA isolated from the reaction mixture (8a′ and 8b′). The stability of DNA alkylation products depends upon the reaction site. The cross-links formed from 1 and 2 were almost completely destroyed upon heating at 90 ºC (pH 7.2) for 30 min (SI, Figrue S4). When the ICL was treated with 1 M piperidine (90 ºC, 30 min), strong DNA cleavage bands were observed with all dGs and weaker bands with dAs (SI, Figures S5 and S6). These results are consistent with the reaction of nitrogen mustard mainly occuring at N7- of dG.14 The alkaline hydrolysis of N7-alkylated purines produces formamidopyrimidines that are labile to heating in piperidine.2d, 15 It was reported that nitrogen mustard forms ICLs in 5′-dGC or 5′-dGNC sequences.14 Therefore, the possible cross-linking sites are G1-G97, G22-G76, G27-G71, G40-G58, or G1-G96, G49-G52 (SI, Figrue S5, lanes 4, 8, 14, 20). The alkylation was also observed with all DNA guanine units in single-stranded DNA 8a′ and 8b′ (SI, Figure S5, lanes 3, 7, 13, 19). In a control experiment, 8 was treated with drug alone (1 or 2) or H2O2 alone, no cleavage band was observed (SI, Figure S5, lanes 1, 2, 11, 12, 17, 18). This indicated that 1, 2, or H2O2 alone do not induce DNA damage under the conditions used in our experiments. When duplex 8 was treated with 3 or 4 in the presence of H2O2 followed by 1 M piperidine (90 ºC, 30 min), there was no DNA cleavage band observed (SI, Figure S7). These data showed that the released quinone methide by 3 or 4 did not produce detectable DNA alkylations under our experimental conditions. Rokita et al has shown that adducts formed between quinone methides and deoxynucleosides were reversible, and the labile alkylating products tended to decompose with short half-life time and were difficult to be isolated.16 Therefore, the detected ICL formation or alkylation induced by 1 or 2 in the presence of H2O2 was exclusively induced by 7 released from 1 and 2. In a control experiment, we examined the cross-linking efficiency of nitrogen mustard 7 alone (47% ICLs), which was identical to those induced by 1 and 2 (43%) upon H2O2-activation (SI, Figure S8).

The masked toxicity of nitrogen mustard in 1 and 2 was caused by the positive charge developed on the nitrogen (A) that strongly decreases the electron density of mustard nitrogen required for alkylation (Scheme 2). The release of tertiary amine C is triggered by the oxidation of the carbon-boron bond initiated by nucleophilic attack by H2O2 (A → B), followed by deboronation (B → C). The lone pair developed on C can form highly electrophilic aziridinium ring D by intramolecular displacement of the chloride by the amine nitrogen. D greatly facilitates the DNA alkylation and crosslinking formation. The activation of 1 and 2 by H2O2 (A → B) and the release of C were further confirmed by NMR analysis of the reaction of 1 and 2 with H2O2.

Scheme 2.

ICL formation induced by 1 and 2 upon H2O2-activation.

Initially, the reaction of 1 and 2 with H2O2 was performed in 10 mM deuterated potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). However, the reaction was too fast to observe all intermediates. Compound 1 was oxidized by 97% within 5 min and spontaneously released 7 (SI, Figure S9B). After 2 h, 1 was completely consumed and converted to 7 (SI, Figure S9C). Similarly, the activation of 2 with H2O2 followed by the release of 7 was complete within 2 h (SI, Figure S9D–F). When the reaction of 1 with H2O2 was carried out in a mixture of DMSO/D2O, we were able to observe all intermediates (Scheme 3 and Figure 3A–D). The integral change of C2-H, C3-H and C4′-H indicated the kinetic transformation of compound 1 into nitrogen mustard 7. Compound 1 was transformed to 1B by 5% after 2 h (Figure 3A), as evidenced by the presence of δ 7.35 (doublet), δ 6.83 (doublet), and δ 4.53 (singlet). Subsequently, 1, 6-benzyl elimination of 1B took place leading to quinone methide that spontaneously reacted with H2O. This was evidenced by the appearance of C2-H (δ 7.09, doublet), C3-H (δ 6.70) and C4′-H (δ 4.33) of compound 9 (2% within 5 h) (Figure 3B). Compounds 1B and 9 were obtained in 32% and 20% within 24 h (Figure 3C). Nitrogen mustard 7 was released in about 25%, as shown by the shift of δ 4.13 (multiplet) to δ 3.96 (triplet) and δ 3.06 (singlet) to δ 2.84 (singlet) (Figure 3C). These data are consistent with those of the authentic sample (Figure 3D). Compound 1 was activated by H2O2 to release nitrogen mustard 7 in approximate 95% yield within 4 days in DMSO/D2O (SI, Figure S10B). However, NMR analysis 4 days after the addition of H2O2 to 2 did not show any change with compound 2 in DMSO/D2O. It is highly likely that the weak acidity of boronic acid group in 2 inhibits the oxidative ability of H2O2. It is precedented that the reaction between arylboronic acid and hydrogen peroxide was pH-dependent.11, 17

Scheme 3.

Release of nitrogen mustard by 1 upon treatment with H2O2.

Figure 3.

1H NMR analysis of the activation of 1 by H2O2 in a mixture of D2O/DMSO. (A) 2 h after addition of H2O2 (1.5 equiv.); (B) 5 h after addition of H2O2; (C) 24 h after addition of H2O2; (D)1H NMR of 7 in a mixture of D2O/DMSO.

Having established that the prodrugs 1 and 2 could be effectively passivated and activated by H2O2, the ability of these compounds to inhibit cancer cell growth was evaluated. Both compounds inhibited various types of cancer cells at 10 μM. They showed about 90% inhibition toward SR cells (Leukemia cell), 85% inhibition toward NCI-H460 (Non-small Cell Lung Cancer cells), and 66% inhibition toward CAKI-1, and 57% toward SN12C (Renal Cancer cells) (Figure 4A).18 However, compound 3 is less toxic to these cells. The toxicity of 1 and 2 is highly likely caused by the release of nitrogen mustard after tumor-specific activation. In order to determine the selectivity, we evaluated the toxicity of 1 and 2 towards non-cancer cells. Normal lymphocytes obtained from three healthy donors were incubated without or with 10 μM of compounds 1 and 2; untreated samples were used as time-matched controls. In all the 3 samples studied, compared to time-matched controls, there was no increase in apoptosis observed between 24 – 72 hrs (Figure 4B and SI, Figure S11).

Figure 4.

Effect of compounds 1, 2, and 3 on cancer cells and normal lymphocytes: (A) Four human cancer cells (SR, NCI- H460, CAKI-1, and SN12C)) were incubated with 10 μM of compounds 1, 2, and 3 for 48 h (grey bar - 3; black bar - 1; lined bar - 2); (B) Normal lymphocytes obtained from healthy donors (n=3) were incubated with 10 μM of 1 and 2 for 48 h. Time matched control samples are set up concurrently (grey bar - control; black bar - compound 1; lined bar -compound 2).

In conclusion, two prodrugs of nitrogen mustard coupled with an arylboronate or boronic acid demonstrated an effective way to mask the cytotoxicity of cancer chemotherapeutic agents and selectively release them in the presence of H2O2. The activity and selectivity were measured by crosslinking or alkylation of DNA as well as by evaluating their ability to inhibit cancer cell growth and toxicity towards normal cells. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report anticancer prodrugs (1 and 2) that can be activated by ROS to release DNA crosslinking agents. Such compounds are non-toxic but are highly likely to undergo tumor-specific activation to generate toxic species in cancer cell. They offer novel ways to improve the therapeutic effectiveness and selectivity of current anticancer agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support of this research from the National Cancer Institute (1R15CA152914-01) and UWM start-up funds (XP). This research was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (-CA136411) Lymphoma SPORE (VG).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures for all reaction and analyses, preparation and characterization of 1–7, bioactive evaluation, autoradiograms of Fe·EDTA, and piperidine treatment of cross-linked products and reacted single-stranded DNA.

References

- 1.a) Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. Chem Rev. 2006;106:277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dronkert MLG, Kanaar R. Mutat Res. 2001;486:217–247. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Hong IS, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10510–10511. doi: 10.1021/ja053493m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hong IS, Ding H, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:485–491. doi: 10.1021/ja0563657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Peng X, Hong IS, Li H, Seidman MM, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10299–10306. doi: 10.1021/ja802177u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Veldhuyzen WF, Pande P, Rokita SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14005–14013. doi: 10.1021/ja036943o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Richter SN, Maggi S, Mels SC, Palumbo M, Freccero M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13973–13979. doi: 10.1021/ja047655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang H, Rokita SE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5957–5960. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Wang P, Liu R, Wu X, Ma H, Cao X, Zhou P, Zhang J, Weng X, Zhang X, Qi J, Zhou X, Weng L. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1116–1117. doi: 10.1021/ja029040o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weng X, Ren L, Weng L, Huang J, Zhu S, Zhou X, Weng L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8020–8023. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Shawn MH, Marquis JC, Zayas B, Wishnok JS, Liberman RG, Skipper PL, Tannenbaum SR, Essigmann JM, Croy RG. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:977–984. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rink SM, Yarema KJ, Solomon MS, Paige LA, Mitra Tadayoni-Rebek B, Essigmann JM, Croy RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15063–15068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kim E, Rye PT, Essigmann JM, Croy RG. J Inorg Biochem. 2009;103:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Cancer Res. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toyokuni S, Okamoto K, Yodoi J, Hiai H. FEBS Lett. 1995;358:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01368-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawanishi S, Hiraku Y, Pinlaor S, Ma N. Biol Chem. 2006:365–372. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Pelicano H, Carney D, Huang P. Drug Resist Update. 2004;7:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Nature Rev. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lopez-Lazaro M. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Zieba M, Suwalski M, Kwiatkowska S, Piasecka G, Grzelewska-Rzymowska I, Stolarek R, Nowak D. Respir Med. 2000;94:800–805. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lim SD, Sun C, Lambeth JD, Marshall F, Amin M, Chung L, Petros JA, Arnold RS. Prostate. 2005;62:200–207. doi: 10.1002/pros.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuivila HG, Armour AG. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:5659–5662. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Miller EW, Albers AE, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16652–16659. doi: 10.1021/ja054474f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dickinson BC, Chang CJA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9638–9639. doi: 10.1021/ja802355u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Miller EW, Tulyathan O, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:263–267. doi: 10.1038/nchembio871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lo LC, Chu CY. Chem Commun. 2003:2728–2729. doi: 10.1039/b309393j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Srikun D, Miller EW, Domaille DW, Chang CJA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4596–4597. doi: 10.1021/ja711480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang WQ, Gao X, Wang BH. In: Boronic Acids. Hall DG, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. pp. 481–512. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Brookes P, Lawley PD. Biochem J. 1961;80:496–503. doi: 10.1042/bj0800496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rink SM, Solomon MS, Taylor MJ, Rajur SB, McLaughlin LW, Hopkins PB. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2551–2557. [Google Scholar]; c) Dong Q, Barsky D, Colvin ME, Melius CF, Ludeman SM, Moravek JF, Colvin OM, Bigner DD, Modrich P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12170–12174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraguchi K, Delaney MO, Wiederholt CJ, Sambandam A, Hantosi Z, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3263–3269. doi: 10.1021/ja012135q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinert EE, Dondi R, Colloredo-Melz S, Frankenfield KN, Mitchell CH, Freccero M, Rokita SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11940–11947. doi: 10.1021/ja062948k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuivila HG. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:870–874. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Data were obtained from Developmental Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute (NCI-60 DTP Human Tumor Cell Line Screen).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.