Abstract

Truncated N6-substituted-4′-oxo- and 4′-thioadenosine derivatives with C2 or C8 substitution were studied as dual acting A2A and A3 adenosine receptor (AR) ligands. The lithiation-mediated stannyl transfer and palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reactions were utilized for functionalization of the C2 position of 6-chloropurine nucleosides. An unsubstituted 6-amino group and a hydrophobic C2 substituent were required for high affinity at the hA2AAR, but hydrophobic C8 substitution abolished binding at the hA2AAR. However, most of synthesized compounds displayed medium to high binding affinity at the hA3AR, regardless of C2 or C8 substitution, and low efficacy in a functional cAMP assay. Several compounds tended to be full hA2AAR agonists. C2 substitution probed geometrically through hA2AAR-docking, was important for binding in order of hexynyl > hexenyl > hexanyl. Compound 4g was the most potent ligand acting dually as hA2AAR agonist and hA3AR antagonist, which might be useful for treatment of asthma or other inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: lithiation-mediated stannyl transfer, structure-activity relationship, adenosine receptors, truncated adenosine, palladium-catalyzed cross coupling, dual-acting ligands

Introduction

The structure of endogenous adenosine, which binds to four subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) of adenosine receptors (ARs)1,2 to induce physiological effects, has been extensively modified, particularly on N6 and/or 4′-hydroxymethyl positions for the development of potent and selective AR ligands.3,4 Among these, 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine (Cl-IB-MECA, 1a, X = O, R = 3-iodobenzyl; Ki = 1.0 nM for hA3AR) is a versatile A3AR agonist, which is in clinical trial as an anticancer agent (Figure 1).5 2-Chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyl-4′-thioadenosine (thio-Cl-IB-MECA, 1b, X = S, R = 3-iodobenzyl; Ki = 0.38 nM for hA3AR), which has a bioisosteric relationship to 1a was also found to be a potent and selective A3AR agonist.6 Compounds 1a and 1b showed anti-proliferative effects in various cancer cell lines, resulting from down-regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway and other mechanisms.7

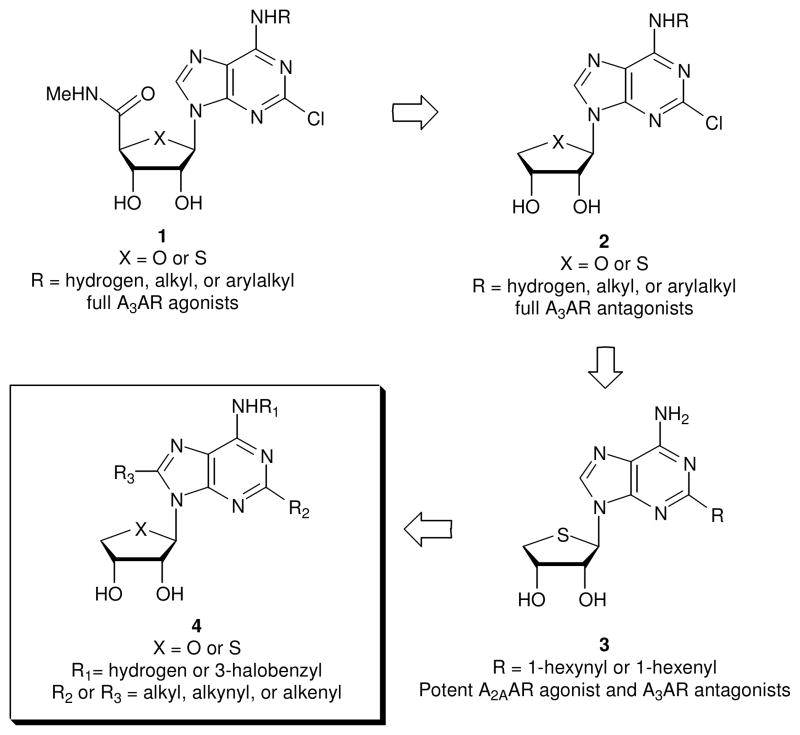

Figure 1.

The design of the target nucleosides acting dually at the A2A and A3ARs A molecular modeling study8 indicated that the NH of the 5′-uronamide of 1 serves as a hydrogen bonding donor in the A3AR binding site and is associated with the induced fit for the receptor activation. On this basis, we designed and synthesized truncated adenosine derivatives 29 removing the 5′-uronamide of 1, to bind potently but with altered ability to induce the conformational change essential for receptor activation. As expected, members of the series of compound 2 proved to be potent and selective A3AR antagonists.9 It should be noted that these A3AR antagonists 2 also showed species-independent binding affinity, making them suitable for efficacy evaluation for drug development in small animal models.9 Compound 2 (X = S, R = 3-iodobenzyl) exhibited a potent anti-glaucoma effect in vivo.10

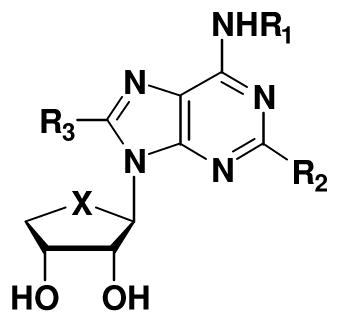

Recently, truncated C2- or C8-substituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 3 containing an appended hydrophobic hexenyl or hexynyl chain at the C2 or C8 position of 2 were designed and synthesized.11 Among these, a C2-hexynyl derivative 3 (R = hexynyl) was discovered as a new template (Ki = 7.19 ± 0.6 nM) for the development of potent A2AAR agonists12 while maintaining antagonism at the A3AR (Ki = 11.8 ± 1.3 nM).11 However, C8-substituted derivatives displayed greatly reduced binding affinity at the A2AAR, while maintaining high affinity at the A3AR, indicating that the binding pocket for C8 substituents in the A2AAR was relatively small, when compared with that for C2 substituents, which could accommodate steric bulk in both A2A and A3ARs.11 This dual activity at both of these subtypes might be beneficial for developing therapeutic drugs against diseases such as asthma and inflammation.

Thus, it was of great interest to extend the structure-activity relationship study of the truncated 4′-thio series 3 to the 4′-oxo series 4 with various substituents at C2 or C8 positions. Truncated 4′-oxo adenosine derivatives containing C2-H or C2-Cl were previously found to interact potently and selectively with the A3AR.9c,9d It was also interesting to determine the effects of N6 substituents on binding affinity to the A2AAR, because 3-halobenzyl substituents at the N6 position generally increased the binding affinity and selectivity at the A3AR.3,4 Herein, we report a full account of truncated C2-, C8-, or N6-modified adenosine derivatives acting dually at the A2A and A3ARs.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

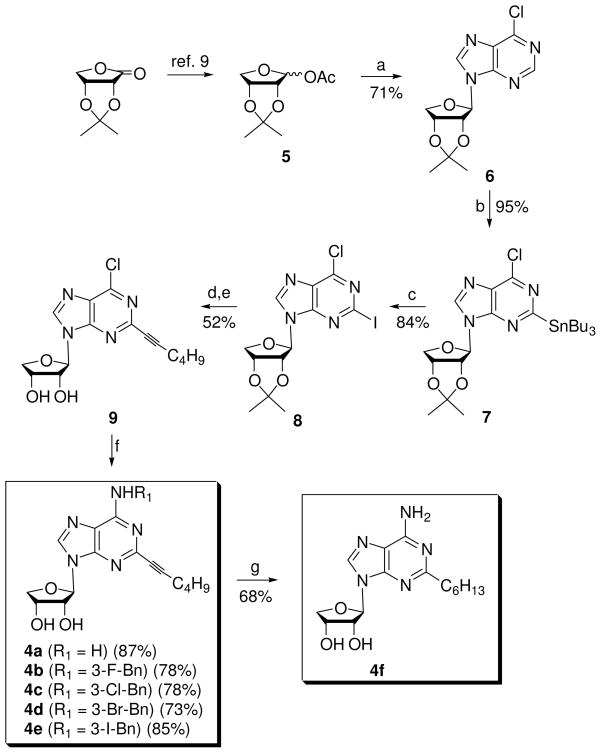

First, 2-hexynyl-N6-substituted-adenosine derivatives 4a-f were synthesized from glycosyl donor 5,9 which was easily synthesized from commercially available 2,3-O-isopropylidene-D-erythronic γ-lactone in two steps, as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1a.

Reagents and conditionsa: a) silylated 6-chloropurine, TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 80 °C, 5 h; b) LiTMP, Bu3SnCl, THF, hexane, −78°C, 1 h; c) I2, THF, rt, 24 h; d) 1-hexyne, Cs2CO3, (Ph3P)4Pd, CuI, DMF, rt, 3 h; e) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h; f) NH3/t-BuOH, 100 °C, 8 h or R1NH2, Et3N, EtOH, rt, 24–48 h; g) Pd/C, H2, MeOH.

Condensation of glycosyl donor 5 with silylated 6-chloropurine in the presence of trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) as a Lewis acid yielded the β-anomer 69c (71%) as a single diastereomer. The anomeric configuration in 6 was easily confirmed by a 1H NMR nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) experiment between H-8 and 3′-H. For the functionalization at the C2 position of 6-chloropurine in 6, lithiatio-nmediated stannyl transfer of 6-chloropurine nucleosides reported by Tanaka and coworkers13a was utilized. Treatment of 6 with a freshly prepared lithium 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidide (LiTMP) initially formed the C8-lithiated species, because the C8-hydrogen is more acidic than the C2-hydrogen. Reaction of the C8-lithiated species with n-tributyltin chloride produced C2-stannyl derivative 7 as a sole regioisomer, which resulted from an anionic transfer of the stannyl group from C8 to the C2 position (see Scheme 1S in the Supporting Information for a reaction mechanism).13a Treatment of 7 with iodine gave 2-iodo-6-chloropurine derivative 8.13 Sonogashira14 coupling of 8 with 1-hexyne in the presence of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium and cesium carbonate yielded C2-hexynyl derivative, which was hydrolyzed with 1 N HCl to give the 2-hexynyl-6-chloro derivative 9. Compound 9 was converted into 2-hexynyl-adenosine derivative 4a and 2-hexynyl-N6-substituted-adenosine derivatives 4b–e by treatment with ammonia and 3-halobenzyl amines, respectively. 2-Hexynyladenosine derivative 4a was subjected to hydrogenation with 10% Pd on carbon to give saturated analogue 4f.

The corresponding 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4g–k were synthesized from glycosyl donor 10, which was easily synthesized from D-mannose according to our previously published procedure,9 as illustrated in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2a.

Reagents and conditionsa: a) 2-iodo-6-chloropurine, BSA, TMSOTf, CH3CN, rt to 80 °C, 3 h; b) 1-hexyne, Cs2CO3, (Ph3P)4Pd, CuI, DMF, rt, 3 h; c) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 20 h; d) NH3 in t-BuOH, 100 °C, 8 h or R1NH2, Et3N, EtOH, rt, 48 h.

The lithiation-mediated stannyl transfer13 of 6-chloropurine nucleosides used in Scheme 1 was first tried for the synthesis of 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4g–k, but resulted in poor formation of 2-iodo-6-chloropurine derivative 11 (5%), due to the presence of acidic 1′ and 4′-protons (conventional nucleoside numbering) in the thiophene ring. Thus alternative method of directly condensing glycosyl donor 10 with freshly prepared 2-iodo-6-chloropurine13b was attempted, as shown in Scheme 2. Condensation of glycosyl donor 10 with silylated 2-iodo-6-chloropurine in the presence of TMSOTf afforded the β-anomer 11 (60%) along with a trace amount of its a-anomer. The anomeric configuration was also confirmed by a 1H NMR NOE experiment between H-8 and 3′-H. Sonogashira14 coupling reaction of 11 with 1-hexyne in the presence of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium {(Ph3P)4Pd} and cesium carbonate yielded the C2-hexynyl derivative 12. Treatment of 12 with 1 N HCl yielded the 2-hexynyl-6-chloro derivative 13, which was treated with ammonia and 3-halobenzyl amines to afford 2-hexynyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4g11 and 2-hexynyl-N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4h–k, respectively.

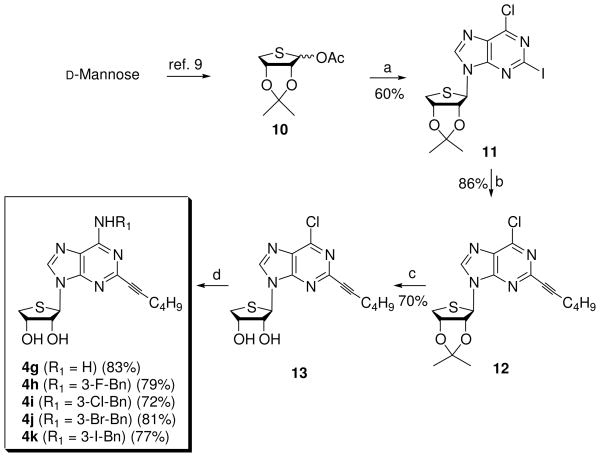

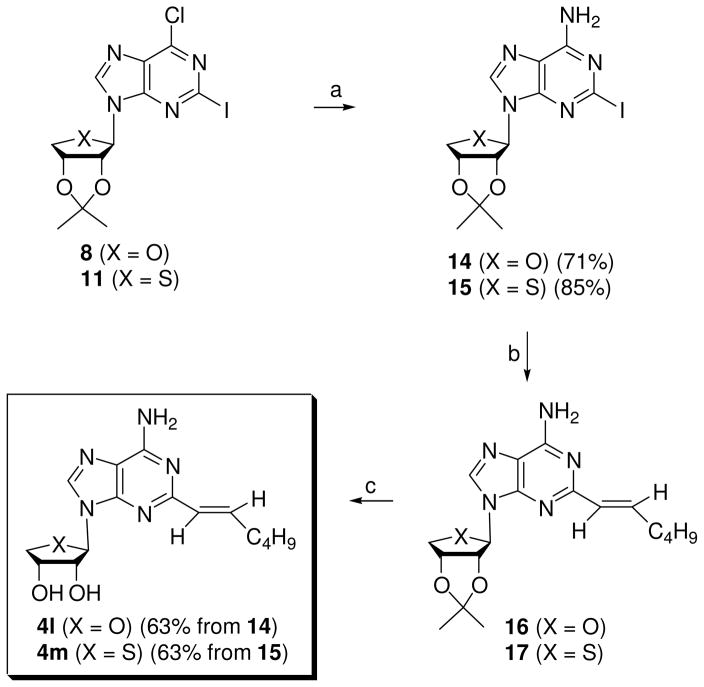

After the successful introduction of the hexynyl group at the C2 position, we decided to extend the synthesis to other hydrophobic C2-hexenyl and C2-hexanyl derivatives. Synthesis of 2-hexenyl derivatives was accomplished using a Suzuki15 coupling reaction as a key step (Scheme 3). Treatment of 2-iodo-6-chloro derivatives 8 and 11 with methanolic ammonia gave 2-iodo-6-amino derivatives 14 and 15, respectively. Suzuki coupling of C2-iodo derivatives 14 and 15 with (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene,16 prepared by treating with 1-hexyne and catecholborane in the presence of (Ph3P)4Pd, produced 2-hexenyl derivatives 16 and 17, respectively. Treatment of 16 and 17 with 1 N HCl gave 2-hexenyl-adenosine derivative 4l and 2-hexenyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4m11, respectively.

Scheme 3a.

Reagents and conditionsa: a) NH3/MeOH, 80 °C, 2 h; b) (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene, (Ph3P)4Pd, Na2CO3, DMF, H2O, 90 °C, 15 h; c) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h.

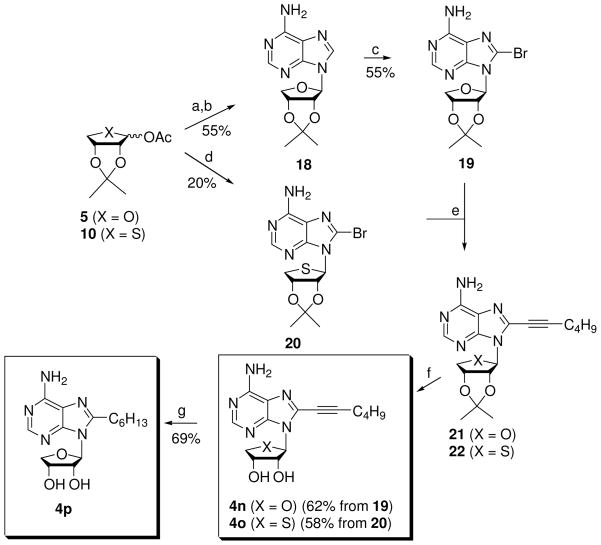

Using a similar synthetic strategy used in Scheme 1, C8-substituted adenosine derivatives 4n–p were synthesized from glycosyl donors 5 and 10 (Scheme 4). Condensation of 59 with silylated 6-chloropurine under Lewis acid conditions, followed by treatment with methanolic ammonia afforded adenine derivative 18. Treatment of 18 with bromine and sodium acetate in methanol yielded 8-bromo derivative 19. However, in the case of 4′-thioadenosine derivatives, the same method was tried, but resulted in the extensive decomposition of starting material. Thus, direct condensation of 10 with 8-bromoadenine17 under Lewis acid conditions provided 8-bromo derivative 20, but only in 20% yield. Sonogashira coupling of 19 and 20 with 1-hexyne using bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium dichloride {(Ph3P)4PdCl2} gave C8-hexynyl derivatives 21 and 22, respectively. Treatment of 21 and 22 with 1 N HCl yielded the final 8-hexynyl derivatives 4n and 4o,11 respectively. Compound 4n was converted to n-hexanyl derivative 4p using catalytic hydrogenation.

Scheme 4a.

Reagents and conditionsa: a) silylated 6-chloropurine, TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 80 °C, 5 h; b) NH3, MeOH, 80 °C, 2 h; c) Br2, 1 N NaOAc, MeOH, rt, 40 min; d) silylated 8-bromoadenine, TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 90 °C, 2 h; e) 1-hexyne, CuI, TEA, DMF, (PPh3)2PdCl2, rt, 3 h; f) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h; g) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 15 h.

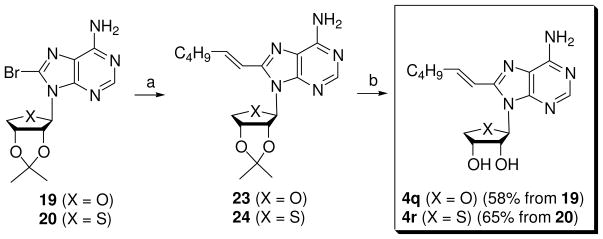

For the synthesis of 8-hexenyl derivatives 4q and 4r, 8-bromo derivatives 19 and 20 were coupled with (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene16 under Suzuki conditions15 to give C2-hexenyl derivatives 23 and 24, respectively. Removal of the isopropylidene group in 23 and 24 under acidic conditions afforded the 8-hexenyladenosine derivative 4q and the 8-hexenyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4r.11

Biological evaluation

Binding assays were carried out using standard radioligands and membrane preparations from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing the human (h) A1 or A3AR or human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells expressing the hA2AAR.18 Nonspecific binding was defined using 10 μM of 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (25, NECA).

As shown in Table 1, 4′-thio derivatives generally exhibited higher binding affinities to hA2A and hA3ARs than the corresponding 4′-oxo derivatives. In case of N6-amino derivatives, most of C2-substituted analogues (R2 = hexynyl and hexenyl) showed moderate to high potent binding affinities at the hA2A and hA3ARs, while most of C8-substitutions (R3 = hexynyl, hexenyl, and hexanyl) reduced binding affinity at the hA2AAR, but maintained high affinity at the hA3AR. These findings indicate that bulky hydrophobic pockets exist in the binding sites of A2AAR and A3AR, allowing the C2-substituent to form favorable hydrophobic interactions, but a bulky hydrophobic group at C8 position could be tolerated only at the binding site of the hA3AR, but not hA2AAR. The ability to enhance affinity at the A2AAR in the truncated series by extending an unsaturated carbon chain at the C2 position implies a mode of receptor binding in common with the riboside series.19 However, introduction of a hydrophobic 3-halobenzyl substituent on the N6-amino group of 4a and 4g, resulting in 4b–4e and 4h–4k, respectively dramatically decreased the binding affinity at the hA2AAR, but maintained the binding affinity at the hA3AR. These results indicate that an unsubstituted primary amino group at the N6 position is conducive to high binding affinity at the hA2AAR, while a bulky hydrophobic substituent at the N6 position is essential for high affinity at the hA3AR. Correlating pharmacological behavior with the nucleoside substitution pattern, a hexynyl substituent generally produced higher binding affinity than the corresponding hexenyl substituent, and two hexanyl derivatives (4f and 4p) were greatly reduced in binding affinity at the three subtypes of hARs, indicating that the geometry of the substituent is important for the binding affinity. All compounds showed weak binding affinity at the hA1AR, although 4a, 4n, and 4q displayed measurable Ki values less than 1 μM at this subtype. Thus, in some cases hydrophobic substitution at the C8 position permitted moderate binding affinity (Ki < 500 nM) at the hA1AR. 4′-Oxo derivative 4d and 4′-thio derivatives 4i, 4j, 4k, and 4o displayed high selectivity for the hA3AR in comparison to hA1AR and hA2AAR, with Ki values in the range of 20 – 67 nM. From the SAR study, compound 4g was discovered to be the most potent dually acting ligand, binding with high affinity at both the hA2AAR (Ki = 7.19 ± 0.6 nM) and hA3AR (Ki = 11.8 ± 1.3 nM) to the exclusion of the hA1AR.11

Table 1.

Binding affinities of known A3AR antagonist 2 and truncated C2- and C8-substituted derivatives 4a–4r at three subtypes of hARs and A3AR-mediated inhibition of cAMP production

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds (R1, R2, R3) | Affinity (Ki, nM ± SEM, or % inhibition)a | Relative efficacy (%inhibition of cAMP ± SEM)c | ||

| hA1 | hA2A | hA3 | hA3 | |

| 2 (X = S, R1 = 3-I-Bn, R2 = Cl, R3 = H)b | 2490 ± 940 | 341 ± 75 | 4.16 ± 0.50 | 4.2 ± 2.3 |

| 4a (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 740 ± 430 | 63.2 ± 15 | 138 ± 44 | 17.4 ± 2.4 |

| 4b (X = O, R1 = 3-F-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 9 ± 1% | 25 ± 3% | 570 ± 130 | 29.5 ± 5.5 |

| 4c (X = O, R1 = 3-Cl-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 9 ± 5% | 42 ± 13% | 150 ± 140 | 39.7 ± 3.8 |

| 4d (X = O, R1 = 3-Br-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 12 ± 4% | 27 ± 4% | 67 ± 18 | 37.2 ± 2.9 |

| 4e (X = O, R1 = 3-I-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 18 ± 2% | 32 ± 9% | 220 ± 50 | 31.5 ± 2.8 |

| 4f (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = 2-hexanyl, R3 = H) | 10 ± 5% | 2160 ± 270 | 39 ± 5% | 22.3 ± 4.5 |

| 4g (X = S, R1 = H, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 39 ± 10% | 7.19 ± 0.6 | 11.8 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 1.6 |

| 4h (X = S, R1 = 3-F-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 24 ± 5% | 46 ± 5% | 150 ± 80 | 47.6 ± 4.9 |

| 4i (X = S, R1 = 3-Cl-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 25 ± 2% | 3730 ± 200 | 24.0 ± 6.0 | 47.2 ± 3.4 |

| 4j (X = S, R1 = 3-Br-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 12 ± 1% | 3910 ± 970 | 24.0 ± 5.0 | 25.2 ± 3.0 |

| 4k (X = S, R1 = 3-I-Bn, R2 = 2-hexynyl, R3 = H) | 15 ± 3% | 4890 ± 840 | 39 ± 5 | 40.0 ± 5.6 |

| 4l (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = 2-hexenyl, R3 = H) | 31.9 ± 1.2% | 178 ± 26 | 218 ± 79 | 42.6 ± 3.1 |

| 4m (X = S, R1 = H, R2 = 2-hexenyl, R3 = H) | 16.2 ± 8.4% | 72.0 ± 19.1 | 13.2 ± 0.8 | 10.7 ± 4.1 |

| 4n (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = H, R3 = 2-hexynyl) | 290 ± 70 | 27.2 ± 2.9% | 31.7 ± 7.4 | 24.5 ± 2.9 |

| 4o (X = S, R1 = H, R2 = H, R3 = 2-hexynyl) | 49.3 ± 4.9% | 46.5 ± 4.3% | 20.0 ± 4.0 | 1.7 ± 3.9 |

| 4p (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = H, R3 = 2-hexanyl) | 18.1 ± 5.0% | 5.8 ± 4.6% | 24.7 ±2.1% | 12.9 ± 2.2 |

| 4q (X = O, R1 = H, R2 = H, R3 = 2-hexenyl) | 500 ± 140 | 27.3 ± 6.3% | 94.2 ± 30.0 | 19.5 ± 2.4 |

| 4r (X = S, R1 = H, R2 = H, R3 = 2-hexenyl) | 3.7 ± 2.9% | 22.8 ± 6.4% | 259 ± 10 | 6.1 ± 1.7 |

All binding experiments were performed using adherent mammalian cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding the appropriate hAR (A1AR and A3AR in CHO cells and A2AAR in HEK-293 cells). Binding was carried out using 1 nM [3H]-R-(-)-N6-2- phenylisopropyl adenosine (R-PIA), [3H]-2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (26, CGS21680, 10 nM), or 0.5 nM [125I]-N6-(3-iodo-4-aminobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine (27, I-AB-MECA) as radioligands for A1, A2A, and A3ARs, respectively. Values are expressed as mean ± sem, n = 3–4 (outliers eliminated) and normalized against a non-specific binder 25 (10 μM). Values expressed as a percentage in italics refer to percent inhibition of specific radioligand binding at 10 μM, with nonspecific binding defined using 10 μM 25.

Ref. 1.

Maximal efficacy (at 10 μM) in an A3AR functional assay, determined by inhibition of foskolin-stimulated cAMP production in AR-transfected CHO cells, expressed as percent inhibition (mean ± standard error, n = 3 – 5) in comparison to effect (100%) of full agonist 1a at 10 μM.

Data for compounds 4g, 4m, 4o, and 4r are from reference 11

The functional screening protocol used at the hA3AR consisted of examining the effects of a single concentration of each compound (10 μM), which in each case except for 4f and 4p far exceeded the Ki values in binding and therefore was interpreted as a roughly maximal effect under ligand saturating conditions. As shown in Table 1, most of the derivatives are low efficacy partial agonists at the hA3AR, with relative percent inhibition of cyclic adenosine-5′-monophosphate (cAMP) formation not exceeding 50%. The 4′-thio C2-substituted derivatives 4i, 4j, and 4k appear to be hA3AR-selective partial agonists. Some of the C2-substituted derivatives, 4c, 4h, 4i, 4k, and 4l, displayed between 40–50% maximal efficacy in comparison to 1a. This was in contrast to another C2 derivative 4g, which did not have significant residual efficacy at the hA3AR. The C8-substituted derivatives 4n through 4r did not exceed 25% of the maximal efficacy to 1a. A C8-hexynyl derivative 4o in the 4′-thio series, which was highly potent in hA3AR binding (Ki = 20 nM) and selective in comparison to A1AR and A2AAR, did not have significant residual efficacy at the hA3AR.

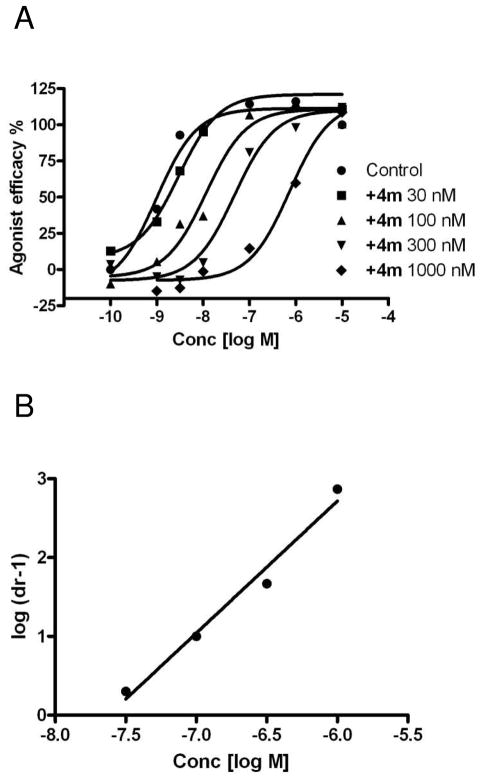

In a set of full concentration-response experiments, compound 4g induced parallel right shifts of the concentration-response curve of a full agonist 1a in the inhibition of cAMP production at the hA3AR expressed in CHO cells, indicating that it is as a full, competitive antagonist (KB = 1.69 nM) at the hA3AR,11 as our previously reported truncated N6-substituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives.9 Similarly, by the same criteria compound 4m was a competitive antagonist (KB = 23.9 nM) at the hA3AR (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of compound 4m on inhibtion of cAMP production induced by full agonist 1a at the hA3AR expressed in CHO cells (A). The data was transformed to a linear Schild plot (B) indicating competitive antagonism with a KB value of 23.9 nM.

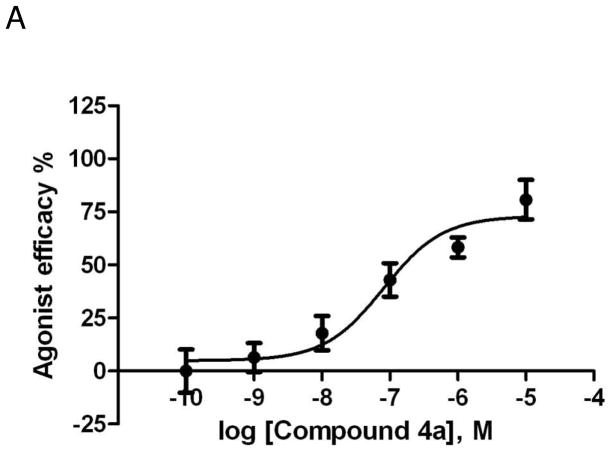

However, in a cAMP functional assay at the hA2AAR expressed in CHO cells, several of these nucleoside agonists demonstrated a higher degree of relative efficacy than at the hA3AR. For example, the most potent compound 4g behaved as a full agonist compared to the standard CGS21680 and displayed an EC50 of 12 nM,11 and compound 4a displayed a maximal stimulation of cAMP formation of 89.9 ± 3.8%, relative to the full agonist NECA (= 100%), with an EC50 of 80.3 nM (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of compounds 4a (A) and 4m (B) in stimulation of cAMP production at the hA2AAR expressed in CHO cells, compared to NECA as reference full agonist (= 100%).

Compounds 4l and 4m were also agonists at the hA2AAR, with maximal percent activity at 10 μM relative to NECA of 83.0 ± 5.2% and 108.8 ± 5.1%, respectively. In a full concentration-response curve (Figure 3B), compound 4m displayed an EC50 value of 20.6 ± 1.58 nM in stimulation of cAMP formation via the hA2AAR. As reported by us previously, compound 4g was a potent full agonist in stimulation of cAMP formation via the hA2AAR with an EC50 of 12 nM.11 The findings that truncated nucleosides 4g and 4m serve as dual ligands acting at the hA2A and hA3ARs are similar to the pharmacological profile of a more heavily 2,5′-substituted adenosine derivative, which was also a hA2AAR agonist and hA3AR antagonist.20

We then examined the effects of several compounds in stimulation of cAMP production at the hA2BAR expressed in CHO cells, compared to NECA as reference full agonist (= 100%). The most potent compound 4g was a weak partial agonist in cyclic AMP accumulation (EC50 ~10 μM).11 As indicated by the percent stimulation at a 10 μM, none of other potent truncated derivatives (4′-oxo: 4a-1.9 ± 4.0%, 4l-1.8 ± 4.9%; 4′-thio: 4m-3.6 ± 2.9%, 4o-7.0 ± 4.4%) displayed significant activity at this AR subtype.

Before examining the pharmacological effect of the most potent compound 4g, the partition coefficient (logP) was first calculated using Tripos SYBYL X-1.2 for the druggability of 4g. LogP of 4g was 0.51, which is sufficient to penetrate cell membranes, suggesting the possibility of bioavailability by oral as well as other administration routes.

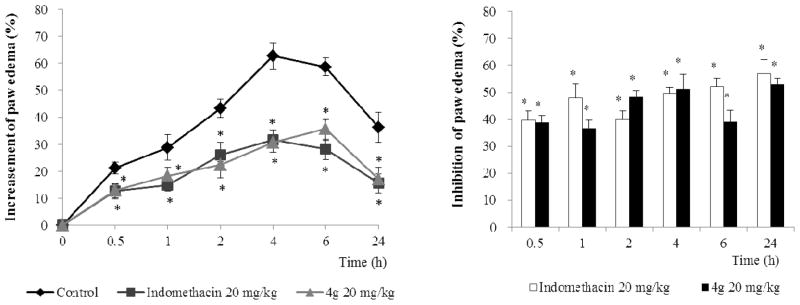

Acute inflammation is a short-term process that is characterized by the typical signs of inflammation, such as swelling, pain, and loss of function due to the infiltration of the tissues by plasma and leukocytes. Among them, edema is one of the fundamental actions of acute inflammation and it is an essential parameter to be considered when evaluating compounds with a potential anti-inflammatory activity.21 Therefore, we tested the anti-inflammatory activity of 4g on carrageenan-induced paw edema model in rats.22 Paw edema was induced by the injection of carrageenan (0.1 mL in 1% solution), and the volume of paw edema was monitored for 24 h. The paw edema was increased and reached its maximum at 4 h after treatment of carrageenan.

As shown in Figure 4, the treatment of 4g significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the paw edema formation. The inhibition rate at 4 h was 51.1% with the treatment of 4g (20 mg/kg). In the same experimental condition, indomethacin (20 mg/kg) was shown as 49.7% inhibition at 4 h.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effect of 4g on the carrageenan-induced paw edema. Paw edema was induced as described in the Experimental Section. The paw volume was measured before (0 h) and at intervals of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 24 h after carrageenan injection using a plethysmometer. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (n=6). *indicates statistically significant differences from the control group (P < 0.01).

The potency of the anti-inflammatory effect of 4g was similar to that of indomethacin. In this study, the formation of edema reached a maximum at 4 h after carrageenan injection and the administration of 4g inhibited the paw edema induced by carrageenan (Figure 4). These findings demonstrated that 4g has a potent in vivo anti-inflammatory activity in an acute inflammation model system.

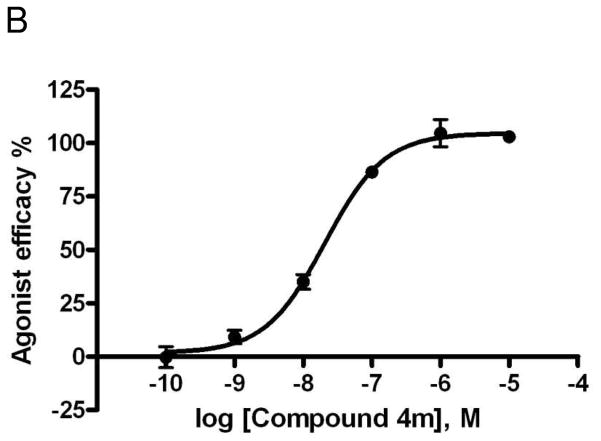

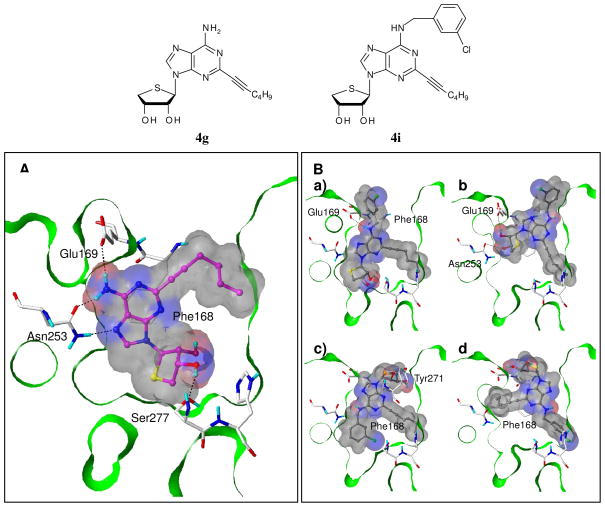

Molecular docking study

The truncated C2-substituted derivative 4g showed the excellent binding affinity at the hA2AAR with a Ki of 7.19 nM. Substituting the N6 position with a chlorobenzyl group, however, dramatically decreased the hA2AAR binding affinity of 4i by 520-fold in comparison to 4g. Our flexible docking study showed that 4g binds readily into the antagonist-bound X-ray crystal structure of human A2A AR (PDB code: 3EML)23 (Figure 5A).11 Its adenine and sugar moieties make tight interactions with the binding site residues via the π-π stacking with Phe168 and H-bonding with Glu169, Asn253 and Ser277. The C2-hexynyl group also contributes to the ligand binding through favorable hydrophobic interactions. In contrast, the N6-chlorobenzyl derivative 4i appeared to have various binding modes and did not maintain some key interactions for binding (Figure 5B). It seems that 4i would lose important interactions at the binding site in order to accommodate both the bulky N6-chlorobenzyl and C2-hexynyl groups. This result could explain why appending a halobenzyl group at the N6 position decreased the A2AAR binding affinity. Furthermore, the binding modes of a series of the C2-substituted and N6-unsubstitued derivatives (i.e. 4a, 4f, 4g, 4l, and 4m) were compared.

Figure 5.

Predicted binding modes of the C2-substituted derivative 4g and its N6-chlorobenzyl derivative 4i in an A2AAR crystal structure.23 (A) Compound 4g binds very well to the receptor, interacting with important residues at the binding site. (B) Compound 4i shows various binding modes and does not maintain the key interactions. Compounds 4g and 4i are depicted in ball-and-stick with carbon atoms in magenta and gray, respectively. The key residues are displayed as capped-stick with carbon atoms in white, and the hydrogen bonds are marked in black dashed lines. The van der Waals surfaces of the ligands are colored by hydrogen bonding capability (red: H-bond donating region; blue: H-bond accepting region). The Fast Connolly surface of the protein is Z-clipped, and the non-polar hydrogens are undisplayed for clarity.

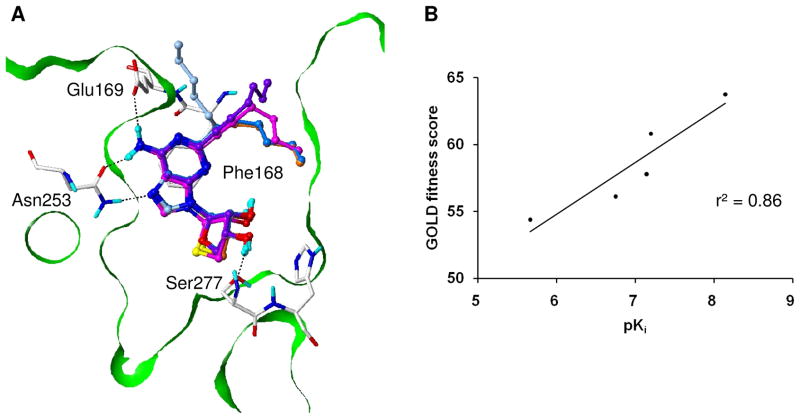

As shown in Figure 6A, the adenine and sugar moieties in this series of truncated nucleosides maintained almost exactly the same binding interactions. This docking study demonstrated that the different binding modes of the C2-substituents directly influenced their activities and a good correlation (r2 = 0.86) was shown between the binding affinities and docking scores (Figure 6B). The activity of the compounds decreased as the flexibility of their C2-substituents increased. Containing the most flexible hexanyl group at the C2 position, 4f showed a relatively low binding affinity and docking score. Taken altogether, the appropriate size of the functional group at the N6 position and rigidity of the C2-substitutents appear to contribute to the ligand binding.

Figure 6.

Predicted binding modes of the five C2-substituted and N6-unsubstituted derivatives in an hA2AAR crystal structure,23 and the correlation between their experimental binding affinities and docking scores. (A) The adenine and sugar moieties of the molecules showed almost exactly the same binding modes maintaining the key interactions. Compounds 4a, 4f, 4g, 4l, and 4m are depicted as ball-and-stick with carbon atoms in purple, light-blue, magenta, skyblue and orange, respectively. (B) The scatter plot of the pKi values and GOLD fitness scores for the five compounds showed a good correlation with r2 of 0.86.

Conclusions

In summary, the series of truncated N6-substituted 4′-oxo- and 4′-thioadenosine derivatives, 4a–r with substitution at C2 or C8 position, were synthesized in order to examine the structure activity relationships of this class of nucleosides as dual acting A2A and A3AR ligands. The corresponding 4′-thio- and 4′-oxonucleosides were prepared starting from D-mannose and D-erythronic γ-lactone, respectively. The highlight of our synthetic endeavor is the functionalization at the C2 position of 6-chloropurine nucleosides using lithiation-mediated stannyl transfer and palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reactions. From the study, it was revealed that an unsubstituted amino group at the N6 position and a hydrophobic substituent at the C2 position were required for high binding affinity at the hA2AAR, but hydrophobic substitution at the C8 position abolished binding affinity at the hA2AAR. However, most of the synthesized compounds displayed medium to high binding affinity at the hA3AR, regardless of the C2- or C8-substitution. Additionally, it was also found that the geometry of the C2-substituent is crucial for the binding affinity in order of hexynyl > hexenyl > hexanyl. From this study, compounds 4g and 4m were discovered as a preferred ligand to act dually at the hA2AAR and hA3AR with high affinity. This mixed activity as A2AAR agonist/A3AR antagonist might be advantageous for anti-asthmatic activity. Moreover, these findings may facilitate the discrimination of the modes of binding of nucleoside derivatives at all subtypes of ARs.

Experimental Section

General methods

1H-NMR Spectra (CDCl3, CD3OD or DMSO-d6) were recorded on Varian Unity Invoa 400 MHz. The 1H-NMR data are reported as peak multiplicities: s for singlet, d for doublet, dd for doublet of doublets, t for triplet, q for quartet, br s for broad singlet and m for multiplet. Coupling constants are reported in hertz. 13C-NMR spectra (CDCl3, CD3OD or DMSO-d6) were recorded on Varian Unity Inova 100 MHz. 19F-NMR spectra (CDCl3, CD3OD) were recorded on Varian Unity Inova 376 MHz. The chemical shifts were reported as parts per million (δ) relative to the solvent peak. Optical rotations were determined on Jasco III in appropriate solvent. UV spectra were recorded on U-3000 made by Hitachi in methanol or water. Infrared spectra were recorded on FT-IR (FTS-135) made by Bio-Rad. Melting points were measured on B-540 made by Buchi. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were used for to determine purity of all synthesized compounds, and the results were within ± 0.4% of the calculated values, confirming ≥ 95% purity. Reactions were checked with TLC (Merck precoated 60F254 plates). Spots were detected by viewing under a UV light, colorizing with charring after dipping in anisaldehyde solution with acetic acid, sulfuric acid and methanol. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh, Merck). Reagents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company. Solvents were obtained from local suppliers. All the anhydrous solvents were distilled over CaH2, P2O5 or sodium/benzophenone prior to the reaction.

Synthesis

(−)-6-Chloro-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-9H-purine (6)

6-Chloropurine (0.618 g, 4.00 mmol), ammonium sulfate (0.079 g, 0.60 mmol), and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) (15 mL) were refluxed for 15 h under dry and inert conditions. The volatile was evaporated under high vacuum and the resulting solid was dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane (10 mL) and cooled at 0 °C. To this solution, a solution of 59 (0.404 g, 2.00 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (10 mL) and TMSOTf (0.72 mL, 4.00 mmol) were added dropwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, at room temperature for 1 h, and finally heated at 80 °C for 5 h. The mixture was cooled and diluted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude syrup was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 2 : 1) to give 6 (0.420 g, 71%) as a white solid: mp 118–119 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 264 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.73 (s, 1 H), 8.18 (s, 1 H), 6.10 (s, 1 H), 5.49 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.27–5.29 (m, 1 H), 4.25–4.31 (m, 2 H), 1.58 (s, 3 H), 1.41 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 152.3, 151.8, 151.4, 145.1, 132.5, 113.7, 92.2, 84.7, 81.5, 76.3, 26.6, 25.0; [α]25D −50.69 (c 0.80, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 297.0752; Anal. calcd for C12H13ClN4O3: C, 48.58; H, 4.42; N, 18.88. Found: C, 48.59; H, 4.12; N, 18.08.

(−)-2-(Tributylstannyl)-6-chloro-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1, 3]dioxol-6-yl)-9H-purine (7)

To a stirred solution of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TMP, 10.7 mL, 63.53 mmol) in dry hexane (15 mL) and dry THF (30 mL) was added n-butyllithium (41.6 mL, 1.5 M solution in hexanes, 66.7 mmol) dropwise at −78 °C over 30 min, and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 1 h. To this mixture, a solution of 6 (3.77 g, 12.7 mmol) in dry THF (30 mL) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 30 min. n-Tributyltin chloride (17.23 mL, 63.53 mmol) was added dropwise to the dark reaction mixture and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 1 h. The resulting dark solution was quenched by dropwise addition of a saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (50 mL). After stirred at room temperature for 15 h, the mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (100 mL). The organic layer was washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude syrup was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 5 : 1) to give 7 (7.10 g, 95%) as a colorless syrup: UV (MeOH) λmax 269 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.06 (s, 1 H), 6.06 (s, 1 H), 5.58 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.30–5.32 (m, 1 H), 4.24–4.30 (m, 2 H), 1.55–1.66 (m, 9 H), 1.41 (s, 3 H), 1.27–1.38 (m, 7 H), 1.19–1.23 (m, 5 H), 0.86–0.92 (m, 9 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 182.4, 150.6, 150.1, 144.1, 131.1, 113.5, 91.9, 84.6, 81.9, 76.3, 29.3, 29.2, 29.1, 27.8, 27.5, 27.2, 26.6, 24.9, 13.9, 12.7, 12.6, 10.9, 9.3, 9.2; [α]25D −8.18 (c 0.33, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 587.1804; Anal. calcd for C24H39ClN4O3Sn: C, 49.21; H, 6.71; N, 9.56. Found: C, 49.03; H, 6.66; N, 9.16.

(−)-6-Chloro-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-2-iodo-9H-purine (8)

To a stirred solution of 7 (7.10 g, 12.1 mmol) in dry THF (100 mL) was added iodine (4.60 g, 18.2 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was diluted with saturated sodium metabisulfite, stirred for 1 h, and then extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude syrup was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 3 : 1) to give 8 (4.30 g, 84%) as a white foam: UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 282.5 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.07 (s, 1 H), 6.05 (s, 1 H), 5.40 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.25–5.28 (m, 1 H), 4.27–4.28 (m, 2 H), 1.57 (s, 3 H), 1.42 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 152.1, 151.3, 145.1, 132.4, 116.8, 113.8, 92.1, 84.7, 81.5, 76.8, 26.6, 25.1; [α]25D −21.88 (c 0.16, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 422.9715; Anal. calcd for C12H12ClIN4O3: C, 34.10; H, 2.86; N, 13.26. Found: C, 33.98; H, 2.77; N, 13.00.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Chloro-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (9)

To a solution of 8 (1.00 g, 2.37 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (20 mL) were added tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium (0.68 g, 0.59 mmol), copper iodide (0.054 g, 0.28 mmol), cesium carbonate (0.77 g, 2.37 mmol), and 1-hexyne (0.3 mL, 2.61 mmol) at room temperature, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and the crude product was used in the next step without further purification. To a stirred ice-cooled solution of above crude product in THF (5 mL) was added 1 N HCl (5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h, neutralized with 1 N NaOH solution, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The mixture was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 30 : 1) to give 9 (0.42 g, 52%) as a white solid: mp 135–137 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 281.0 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.70 (s, 1 H), 6.05 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 4.90–4.92 (m, 1 H), 4.55 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 9.6 Hz), 4.43–4.45 (m, 1 H), 4.02 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.6 Hz), 2.50 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.61–1.69 (m, 2 H), 1.50–1.58 (m, 2 H), 0.98 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 153.1, 151.1, 147.9, 147.2, 132.1, 91.5, 91.1, 80.5, 76.6, 75.7, 72.3, 31.4, 23.1, 19.5, 13.9; [α]25D −65.83 (c 0.12, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 337.1062; Anal. calcd for C15H17ClN4O3: C, 53.50; H, 5.09; N, 16.64. Found: C, 53.56; H, 5.01; N, 16.34.

(−)-6-Chloro-9-((3aS,4R,6aR)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrothieno[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl-2-iodo-9H-purine (11)

To a stirred solution of 2-iodo-6-chloropurine (1.90 g, 6.88 mmol) in dry CH3CN (30 mL) was added N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA, 2.24 mL, 9.16 mmol) under dry and inert conditions, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 45 min to obtain a clear solution. To this solution, a solution of 109 (1.00 g, 4.58 mmol) in dry CH3CN (5 mL) was added dropwise, followed by the addition of TMSOTf (0.91 mL) at room temperature, and the mixture was heated to 80 °C for 3 h. The reaction was cooled to room temperature, quenched with saturated NaHCO3 solution (40 mL), and diluted with EtOAc (50 mL) and then organic layers were separated. The aqueous layer was again extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 3 : 1) to give compound 11 as a white foam (1.20 g, 60%): UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 282.0 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.06 (s, 1 H), 5.84 (s, 1 H), 5.33 (t, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.21 (d, 1 H, J = 5.6 Hz), 3.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 12.8 Hz), 3.25 (d, 1 H, J = 12.8 Hz), 1.59 (s, 3 H), 1.37 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 151.9, 151.2, 144.4, 132.7, 116.7, 112.1, 90.0, 84.8, 70.7, 41.5, 26.6, 24.8; [α]25D −66.33 (c 0.10, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 438.9486; Anal. calcd for C12H12ClIN4O2S: C, 32.86; H, 2.76; N, 12.77; S, 7.31. Found: C, 32.89; H, 2.89; N, 12.47; S, 7.01.

(−)-6-Chloro-9-((3aS,4R,6aR)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrothieno[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purine (12)

Compound 11 (0.60 g, 1.37 mmol) was converted to 12 (0.46 g, 86%) as a thick syrupy liquid, using the same Sonogashira conditions used in the preparation of 9: UV (MeOH) λmax 285.0 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.16 (s, 1 H), 5.90 (s, 1 H), 5.32 (t, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.21 (d, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 3.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 12.8 Hz), 3.23 (d, 1 H, J = 12.8 Hz), 2.48 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.61–1.70 (m, 2 H), 1.58 (s, 3 H), 1.47–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.35 (s, 3 H), 0.95 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 151.3, 151.2, 146.3, 144.7, 130.8, 112.1, 91.3, 89.9, 843.7, 79.7, 70.2, 41.2, 30.3, 26.6, 24.8, 22.3, 19.3, 13.8; [α]25D −57.35 (c 0.469, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 393.1145; Anal. calcd for C18H21ClN4O2S: C, 55.02; H, 5.39; N, 14.26; S, 8.16. Found: C, 55.41; H, 5.21; N, 14.47; S, 8.11.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-Chloro-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (13)

Compound 12 (0.92 g, 2.34 mmol) was converted to 13 (0.58 g, 70%) as a white solid, using the same hydrolysis conditions used in the preparation of 9: mp 76–78 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 284.5 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.87 (s, 1 H), 6.11 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 4.69 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 6.4 Hz), 4.48 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 7.6 Hz), 3.56 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 10.8 Hz), 2.97 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 10.8 Hz), 2.51 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.61–1.67 (m, 2 H), 1.50–1.56 (m, 2 H), 0.98 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (CD3OD) δ 153.6, 151.0, 148.0, 147.1, 131.9, 91.5, 80.9, 80.5, 74.4, 64.6, 35.5, 31.4, 23.1, 19.5, 14.0; [α]25D −32.49 (c 0.634, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 353.0835; Anal. calcd for C15H17ClN4O2S: C, 51.06; H, 4.86; N, 15.88; S, 9.09. Found: C, 51.09; H, 4.89; N, 15.47; S, 9.21.

(−)-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-Tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-2-iodo-9H-purin-6-amine (14)

A solution of 8 (0.303 g, 0.72 mmol) in methanolic ammonia (5 mL) was stirred for 2 h at 80 °C. The reaction mixture was evaporated and the crude residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 1 : 1) to give 15 (0.205 g, 71%) as a colorless syrup: UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 262.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.16 (s, 1 H), 7.74 (br s, 2 H, D2O exchangeable), 6.11 (s, 1 H), 5.27 (d, 1 H, J = 5.6 Hz), 5.13–5.15 (m, 1 H), 4.06–4.12 (m, 2 H), 1.47 (s, 3 H), 1.33 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 155.9, 149.3, 139.8, 120.9, 118.9, 112.0, 89.2, 84.0, 80.7, 74.5, 26.2, 24.6; [α]25D −13.25 (c 0.08, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 404.0225; Anal. calcd for C12H14IN5O3: C, 35.75; H, 3.50; N, 17.37. Found: C, 35.89; H, 3.89; N, 17.47.

(−)-9-((3aS,4R,6aR)-Tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylthieno[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)-2-iodo-9H-purin-6-amine (15)

Compound 11 (0.535 g, 1.22 mmol) was converted to 15 (0.439 g, 85%) as a colorless syrup, according to the same procedure used in the preparation of 14: UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 267.0 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.20 (s, 1 H), 5.97 (s, 1 H), 5.30 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.23 (d, 1 H, J = 5.6 Hz), 3.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 12.8 Hz), 3.14 (d, 1 H, J = 12.8 Hz), 1.54 (s, 3 H), 1.35 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 156.1, 150.4, 141.9, 120.0, 118.0, 112.7, 91.2, 86.4, 71.3, 41.6, 26.8, 24.9; [α]25D −61.90 (c 0.08, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 419.998; Anal. calcd for C12H14IN5O2S: C, 34.38; H, 3.37; N, 16.70; O, 7.63; S, 7.65. Found: C, 34.11; H, 3.22; N, 16.40; S, 7.45.

(−)-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-Tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-9H-purin-6-amine (18)

A solution of 6 (0.37 g, 1.25 mmol) in methanolic ammonia (5 mL) was heated for 2 h at 80 °C. The reaction mixture was evaporated and the crude residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 1 : 1) to give 18 (0.27 g, 78%) as a white foam: UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 255 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.32 (s, 1 H), 7.89 (s, 1 H), 6.19 (brs, 2 H), 6.03 (s, 1 H), 5.48 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.27 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 5.6 Hz), 4.24–4.31 (m, 2 H), 1.58 (s, 3 H), 1.41 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 154.7, 151.3, 149.5, 141.1, 120.3, 113.5, 91.9, 84.8, 81.7, 76.1, 26.6, 25.1; [α]25D −35.48 (c 0.09, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 278.1257; Anal. calcd for C12H15N5O3: C, 51.98; H, 5.45; N, 25.26. Found: C, 51.98; H, 5.87; N, 25.47.

(−)-8-Bromo-9-((3aS,6R,6aS)-tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylfuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-9H-purin-6-amine (19)

To a solution of 18 (89 mg, 0.32 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) and 1 N sodium acetate (1.7 mL) was added bromine (0.033 mL, 0.64 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 40 min. The mixture was diluted with saturated sodium metabisulfite solution and stirred until the red color disappeared. The volatile was evaporated and the resulting aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with water, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and filtered. The solvent was evaporated to give a pale yellowish residue. The residue was purified by flash silica gel column chromatography (hexane : EtOAc = 2 : 1) to give 19 (63 mg, 55%) as a white foam: UV (CH2Cl2) λmax 262 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.26 (s, 1 H), 6.20 (brs, 2 H), 6.16 (s, 1 H), 5.61 (d, 1 H, J = 5.6 Hz), 5.36–5.38 (m, 1 H), 4.20–4.21 (m, 2 H), 1.59 (s, 3 H), 1.42 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 153.8, 151.9, 150.9, 128.8, 120.0, 113.2, 92.4, 84.3, 82.2, 76.5, 26.6, 24.9; [α]25D −28.08 (c 0.26, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 356.0365; Anal. calcd for C12H14BrN5O3: C, 40.47; H, 3.96; N, 19.66. Found: C, 40.12; H, 3.88; N, 19.48.

(−)-8-Bromo-9-((3aR,6R,6aS)-tetrahydro-2,2-dimethylthieno[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-9H-purin-2-amine (20)

8-Bromoadenine (0.40 g, 1.84 mmol) and 10 (0.20 g, 0.92 mmol) were condensed to give 20 (69 mg, 20%) as colorless syrup, according to similar procedure used in the preparation of 6: UV (MeOH) λmax 263.5 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.25 (s, 1 H), 5.91 (s, 1 H), 5.81 (brs, 2 H, NH2), 5.54 (d, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.50 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 3.87 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 12.4 Hz), 3.14 (d, 1 H, J = 12.4 Hz), 1.60 (s, 3 H), 1.38 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 154.3, 153.0, 150.7, 127.8, 120.4, 111.4, 89.0, 86.0, 71.9, 41.4, 26.6, 24.7; [α]25D −77.07 (c 0.16, CH2Cl2); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 373.0151; Anal. calcd for C12H14BrN5O2S: C, 38.72; H, 3.79; N, 18.81; S, 8.61. Found: C, 38.88; H, 3.88; N, 18.48; S, 8.41.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4a)

A solution of 9 (0.125 g, 0.42 mmol) in NH3/tBuOH (5 mL) was stirred at 100 °C for 8 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and the residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4a (0.103 g, 87%) as a white solid: mp 164–166 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 269.5 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.26 (s, 1 H), 5.94 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 4.86–4.87 (m, 1H), 4.51 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 9.6 Hz), 4.40–4.42 (m, 1 H), 3.98 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.0, 9.6 Hz), 2.45 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.61–1.65 (m, 2 H), 1.49–1.55 (m, 2 H), 0.98 (t, 3 H, J = 7.6 Hz); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 157.2, 151.1, 148.1, 142.3, 120.1, 99.4, 88.4, 81.4, 76.6, 75.4, 72.3, 31.7, 23.2, 19.6, 14.1; [α]25D −39.50 (c 0.16, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 318.1557; Anal. calcd for C15H19N5O3: C, 56.77; H,6.03; N, 22.07. Found: C, 56.98; H, 5.88; N, 22.01.

General procedure for the synthesis of 4b–4e

To a solution of diol 9 in EtOH (5 mL) were added Et3N (3 equiv) and 3-halobenzylamine (1.5 equiv) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 to 48 h. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by a flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4b–4e as white solids.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-(3-Fluorobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4b)

Yield: 78%; mp 206–207 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 272.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.47 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.44 (s, 1 H), 7.32–7.37 (m, 1 H), 7.12–7.17 (m, 2 H), 7.02–7.07 (m, 1 H), 5.85 (d, 1 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.45 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.20 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.69–4.75 (m, 3 H), 4.33 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 9.2 Hz), 4.24–4.25 (m, 1 H), 3.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.2 Hz); 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.49–1.56 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 163.4, 161.0, 154.0, 149.1, 145.8, 142.9, 140.6, 130.2 (d), 123.1, 119.0, 113.6 (q), 87.1, 85.6, 81.6, 74.4, 73.5, 70.2, 42.4, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −58.87 (c 0.23, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 426.1948; Anal. calcd for C22H24FN5O3: C, 62.11; H, 5.69; N, 16.46. Found: C, 61.98; H, 5.89; N, 16.23.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-(3-Chlorobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4c)

Yield: 78%; mp 210–212 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 271.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.47 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.44 (s, 1 H), 7.27–7.39 (m, 4 H), 5.84 (d, 1 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.45 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.20 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.67–4.75 (m, 3 H), 4.33 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 9.2 Hz), 4.24–4.25 (m, 1 H), 3.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.2 Hz); 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.49–1.57 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.0, 149.2, 145.8, 142.5, 140.6, 132.9, 130.1, 128.3, 127.0, 126.6, 125.8, 87.1, 85.7, 81.6, 74.4, 73.5, 70.2, 42.3, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −57.46 (c 0.13, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 442.1647; Anal. calcd for C22H24ClN5O3: C, 59.79; H, 5.47; N, 15.85. Found: C, 59.99; H, 5.55; N, 15.90.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-(3-Bromobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4d)

Yield: 73%; mp 217–218 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 273.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.47 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.44 (s, 1 H), 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.42 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.25–7.34 (m, 2 H), 5.84 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 5.45 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.20 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.67–4.74 (m, 3 H), 4.32 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 9.2 Hz), 4.24–4.25 (m, 1 H), 3.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.2 Hz); 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.49–1.56 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.0, 145.8, 142.8, 140.6, 130.5, 130.0, 129.6, 126.3, 121.5, 87.1, 85.7, 81.6, 78.8; 74.4, 73.5, 70.2, 42.3, 29.9, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −49.63 (c 0.14, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 486.1136; Anal. calcd for C22H24BrN5O3: C, 54.33; H, 4.97; N, 14.40. Found: C, 54.23; H, 5.01; N, 14.21.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-(3-Iodobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydofuran-3,4-diol (4e)

Yield: 85%; mp 224–226 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 273.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.47 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.43 (s, 1 H), 7.73 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.59 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.11 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 5.84 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 5.44 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.19 (d, 1 H, J = 2.8 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.63–4.72 (m, 3 H), 4.33 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 9.2 Hz), 4.25 (brs, 1 H), 3.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.2 Hz); 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.50–1.57 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 153.9, 149.1, 145.8, 142.6, 140.6, 135.9, 135.4, 130.5, 126.6, 118.9, 94.7, 87.1, 85.7, 81.6, 74.4, 73.5, 70.2, 42.2, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −58.09 (c 0.14, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 534.0998; Anal. calcd for C22H24IN5O3: C, 49.54; H, 4.54; N, 13.13. Found: C, 49.14; H, 4.13; N, 13.01.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-2-hexy1-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4f)

A mixture of 4a (22 mg, 0.069 mmol), absolute ethanol (5 mL), and 10% palladium on carbon (5 mg) was hydrogenated on a Parr apparatus at 40 psi for 15 h. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to give a residue. The residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4f (15 mg, 68%) as a white solid: mp 105–107 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 261.5 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.19 (s, 1 H), 5.95 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 4.93–4.96 (m, 1 H), 4.52 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 9.6 Hz), 4.42–4.44 (m, 1 H), 3.99 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 9.6 Hz), 2.74 (t, 2 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.74–1.80 (m, 2 H), 1.30–1.39 (m, 6 H), 0.88–0.92 (m, 3 H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 167.2, 157.1, 151.8, 141.5, 119.0, 90.5, 76.6, 75.5, 72.5, 40.0, 33.0, 30.3, 30.0, 23.8, 14.6; [α]25D −54.05 (c 0.11, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 322.1883; Anal. calcd for C15H23N5O3: C, 56.06; H, 7.21; N, 21.79. Found: C, 56.44; H, 7.02; N, 21.49.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-Amino-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4g)

Compound 13 (0.065 g, 0.18 mmol) was converted to 4g (0.051 g, 83%) as a white solid, using the same procedure in the preparation of 4a: mp 234–235; UV (MeOH) λmax 271.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.47 (s, 1 H), 7.35 (br s, 2 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.85 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.53 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.34 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.57–4.61 (m, 1 H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz), 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.49–1.55 (m, 2 H), 1.40–1.46 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 155.7, 149.9, 145.7, 140.4, 118.3, 85.4, 81.3, 78.5, 72.2, 61.1, 34.3, 29.9, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −28.36 (c 0.20, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 334.1336; Anal. calcd for C15H19N5O2S: C, 54.04; H, 5.74; N, 21.01; S, 9.62. Found: C, 54.44; H, 5.89; N, 21.21; S, 9.41.

General procedure for the synthesis of 4h–4k

To a solution of diol 13 in EtOH (20 mL) were added Et3N (3 equiv) and 3-halobenzylamine (1.5 equiv) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by a flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4h–4k as white solids.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-(3-Fluorobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-dio (4h)

Yield 79%; mp 200–202 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 274.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 8.45 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 7.32–7.37 (m, 1 H), 7.12–7.17 (m, 2 H), 7.02–7.07 (m, 1 H), 5.87 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.54 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.68 (br s, 2 H), 4.58–4.62 (m, 1 H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz), 2.40 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.49–1.55 (m, 2 H), 1.39–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 163.4, 160.9, 154.0, 149.4, 145.6, 143.0, 140.5, 130.2 (d), 123.1, 118.6, 113.6 (q), 85.7, 81.5, 78.6, 72.2, 61.1, 42.4, 34.4, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −48.91 (c 0.184, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 442.1708; Anal. calcd for C22H24FN5O2S: C, 59.85; H, 5.48; N, 15.86; S, 7.26. Found: C, 59.84; H, 5.88; N, 15.47; S, 7.21.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-(3-Chlorobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4i)

Yield 72%; mp 199–201 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 275.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 8.46 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 7.27–7.39 (m, 4 H), 5.87 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 5.54 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.35 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.58–4.67 (m, 3 H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 10.8 Hz), 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.50–1.57 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 153.9, 149.4, 145.7, 142.5, 140.5, 132.9, 130.1, 127.0, 126.6, 125.8, 118.7, 85.7, 81.6, 78.6, 72.2, 61.1, 42.3, 34.4, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −46.67 (c 0.30, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 458.1415; Anal. calcd for C22H24ClN5O2S: C, 57.70; H, 5.28; N, 15.29; S, 7.00. Found: C, 57.41; H, 5.68; N, 15.47; S, 7.00.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-(3-Bromobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4j)

Yield 81%; mp 206–208 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 275.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 8.46 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.42 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.33 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.27 (t, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 5.87 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.84 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.60–4.66 (m, 3 H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 10.8 Hz), 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.51–1.55 (m, 2 H), 1.39–1.45 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 153.9, 149.4, 145.6, 142.7, 140.5, 130.4, 129.9, 129.5, 126.2, 121.5, 118.6, 85.7, 81.5, 78.6, 72.2, 61.1, 42.3, 34.4, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −52.17 (c 0.207, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 504.0890; Anal. calcd for C22H24BrN5O2S: C, 52.59; H, 4.81; N, 13.94; S, 6.38. Found: C, 52.22; H, 4.89; N, 13.57; S, 5.99.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-(3-Iodobenzylamino)-2-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4k)

Yield 77%; mp 225–227 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 274.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 8.45 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 7.73 (s, 1 H), 7.58 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.34 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.11 (t, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 5.87 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.54 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.57–4.62 (m, 3 H), 4.32–4.36 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 10.8 Hz), 2.42 (t, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.50–1.57 (m, 2 H), 1.38–1.47 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13 C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 153.9, 149.4, 145.6, 142.6, 140.5, 135.9, 135.4, 130.5, 126.6, 118.6, 94.7, 85.7, 81.5, 78.6, 72.1, 61.1, 42.2, 34.3, 29.8, 21.5, 17.9, 13.4; [α]25D −43.33 (c 0.18, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 550.0764; Anal. calcd for C22H24IN5O2S: C, 48.09; H, 4.40; N, 12.75; S, 5.84. Found: C, 48.09; H, 4.21; N, 12.47; S, 6.01.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-2-((E)-hex-1-enyl)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4l)

A mixture of 14 (0.096 g, 0.24 mmol), tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium (28 mg, 0.024 mmol), sodium carbonate (76 mg, 0.72 mmol), and (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene (67 mg, 0.33 mmol) in DMF and H2O (8 : 1, 5 mL) was stirred at 90 °C for 15 h. The reaction mixture was filtered over a Celite bed, and the residue was evaporated to give the crude compound 16. To a solution of 16 in THF (5 mL) was added 1 N HCl (5 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h. The mixture was neutralized with 1 N NaOH, and then carefully evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4l (48 mg, 63%) as a white solid: mp 165–167 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 293.0 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.20 (s, 1 H), 6.99–7.06 (m, 1 H), 6.36 (tt, 1 H, J =1.6, 15.6 Hz), 5.97 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz), 4.94 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.8, 6.0 Hz), 4.53 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 9.6 Hz); 4.43–4.46 (m, 1 H), 3.99 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.0, 9.6 Hz), 2.25–2.31 (m, 2 H), 1.47–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.36–1.45 (m, 2 H), 0.95 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 160.9, 156.9, 151.7, 141.6, 141.3, 130.7, 90.3, 76.4, 75.4, 72.4, 57.9, 33.3, 32.3, 23.4, 14.3; [α]25D −47.05 (c 0.12, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 320.1747; [α]25D − 44.80 (c 0.12, MeOH); Anal. calcd for C15H21N5O3: C, 56.41; H, 6.63; N, 21.90. Found: C, 56.78; H, 6.89; N, 21.77.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-Amino-2-(E)-hex-1-enyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4m)

Compound 15 (46 mg, 0.11 mmol) was converted to 4m (23 mg, 63%) as a white solid, according to the same procedure used in the preparation of 4l: mp 209–210 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 274.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.37 (s, 1 H), 7.11 (brs, 2 H, NH2), 6.87–6.94 (m, 1 H), 6.29 (d, 1 H, J = 15.2 Hz), 5.89 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.52 (d, 1 H, OH, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.36 (d, 1 H, OH, J = 4.0 Hz), 4.63–4.67 (m, 1 H), 4.37 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 3.2 Hz), 3.42 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.4, 10.8 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz); 2.20–2.26 (m, 2 H), 1.41–1.48 (m, 2 H), 1.29–1.38 (m, 2 H), 0.90 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 158.2, 155.5, 150.6, 139.6, 138.2, 130.4, 117.7, 78.5, 72.3, 61.0, 34.4, 31.4, 30.5, 21.7, 13.8; [α]25D −44.80 (c 0.12, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 336.1499; Anal. calcd for C15H21N5O2S: C, 53.71; H, 6.31; N, 20.88; S, 9.56. Found: C, 53.89; H, 6.71; N, 20.49; S, 9.32.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-8-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4n)

Compound 19 (0.605 g, 0.19 mmol) was dissolved in Et3N (10 mL) and DMF (10 mL). After purging the solution with N2, (Ph3P)2PdCl2 (0.238 g, 0.34 mmol), CuI (0.065 g, 0.34 mmol), and 1-hexyne (0.49 mL, 4.25 mmol) were subsequently added dropwise. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The volatiles were evaporated to give the crude compound 21. To a solution of 21 in THF (10 mL) was added 1 N HCl (10 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h. The mixture was neutralized with 1 N NaOH, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 10 : 1) to give 4n (0.334 g, 62%) as a white solid: mp 228–232 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 291.5 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.19 (s, 1 H), 6.14 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.32 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.8, 6.8 Hz), 4.57 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 9.6 Hz), 4.43–4.45 (m, 1 H), 3.99 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.2, 9.6 Hz), 2.59 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.64–1.70 (m, 2 H), 1.52–1.58 (m, 2 H), 1.00 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ156.9, 154.4, 150.6, 136.7, 120.3, 99.9, 91.1, 76.1, 75.1, 72.9, 70.8, 31.2, 23.1, 19.7, 13.9; [α]25D −42.75 (c 0.14, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 318.1568; Anal. calcd for C15H19N5O3: C, 56.77; H, 6.03; N, 22.07. Found: C, 56.89; H, 6.23; N, 22.47.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-Amino-8-(hex-1-ynyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4o)

Compound 20 (69 mg, 0.19 mmol) was converted to 4o (36 mg, 58%) as a white solid, according to the same procedure used in the preparation of 4n: mp 234–235 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 294.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.16 (s, 1 H), 7.40 (brs, 2 H, NH2), 6.03 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 5.44 (d, 1 H, -OH, J = 6.4 Hz), 5.33 (d, 1 H, OH, J = 4.0 Hz), 5.24–5.29 (m, 1 H), 4.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 3.2 Hz), 3.42 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 11.2 Hz), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.0, 11.2 Hz), 2.59 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.55–1.62 (m, 2 H), 1.44–1.51 (m, 2 H), 0.93 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 155.7, 153.1, 149.1, 133.7, 118.9, 98.0, 76.5, 72.3, 70.7, 63.2, 35.5, 29.6, 21.4, 18.3, 13.4; [α]25D −112.2 (c 0.14, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 334.1339; Anal. calcd for C15H19N5O2S: C, 54.04; H, 5.74; N, 21.01; S, 9.62. Found: C, 54.43; H, 5.88; N, 19.94; S, 9.31.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-8-hexyl-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4p)

A mixture of 4n (0.116 g, 0.36 mmol), absolute ethanol (20 mL), and 10% palladium on carbon (20 mg) was hydrogenated on a Parr apparatus at 40 psi for 15 h. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated. The mixture was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4p (81 mg, 69%) as a white solid: mp 228–229 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 259.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.14 (s, 1 H), 7.41 (brs, 2 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.76 (d, 1 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.37 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.25 (brs, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.13–5.15 (m, 1 H), 4.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 9.2 Hz), 4.28 (pseudo t, 1 H, J = 3.2 Hz), 3.83 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz), 2.82–2.87 (m, 2 H), 1.69–1.77 (m, 2 H), 1.32–1.39 (m, 2 H), 1.26–1.31 (m, 4 H), 0.85–0.88 (m, 3 H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.3, 152.9, 150.5, 150.1, 118.1, 88.3, 74.3, 73.2, 70.7, 30.9, 28.4, 27.6, 27.4, 22.0, 13.9; [α]25D −36.50 (c 0.13, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 322.1883; Anal. calcd for C15H23N5O3: C, 56.06; H, 7.21; N, 21.79. Found: C, 56.45; H, 7.22; N, 21.77.

(−)-(2R,3S,4S)-2-(6-Amino-8-(hex-1-enyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (4q)

A mixture of 19 (78.8 mg, 0.22 mmol), tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium(0) (26 mg, 0.022 mmol), sodium carbonate (70 mg, 0.66 mmol), and (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene (134 mg, 0.66 mmol) in DMF and H2O (8 : 1, 5 mL) was stirred for 15 h at 90 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered by a bed of Celite, and the volatiles were evaporated to give the crude compound 23. To a solution of 23 in THF (3 mL) was added 1 N HCl (3 mL), and the mixture stirred at room temperature for 15 h. The mixture was neutralized with 1 N NaOH solution, and then carefully evaporated under reduced pressure. The mixture was subjected to flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 20 : 1) to give 4q (41 mg, 58%) as a white solid: mp 204–206 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 296.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.08 (s, 1 H), 7.18 (brs, 2 H, D2O exchangeable), 6.84–6.92 (m, 1 H), 6.58 (tt, 1 H, J = 1.6, 15.6 Hz), 5.91 (d, 1 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 6.8 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.21 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.05–5.06 (m, 1 H), 4.37 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 9.6 Hz), 4.28 (d, 1 H, J = 3.6 Hz), 3.82 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.2, 9.6 Hz); 2.28–2.34 (m, 2 H), 1.43–1.50 (m, 2 H), 1.31–1.40 (m, 2 H), 0.91 (t, 3 H, J = 7.6 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 155.4, 151.9, 150.2, 148.0, 140.8, 118.8, 116.6, 87.6, 74.1, 73.3, 70.5, 32.0, 30.3, 21.7, 13.7; [α]25D −24.76 (c 0.11, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 320.1717; Anal. calcd for C15H21N5O3: C, 56.41; H, 6.63; N, 21.93. Found: C, 56.32; H, 6.85; N, 21.89.

(−)-(2R,3S,4R)-2-(6-Amino-8-(hex-1-enyl)-9H-purine-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (4r)

Compound 20 (42 mg, 0.12 mmol) was converted to 4r (25 mg, 65%) as a white solid, according to the same procedure used in the preparation of 4q: mp 248–249 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 297.5 nm; 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.15 (s, 1 H), 6.94–7.01 (m, 1 H), 6.60 (d, 1 H, J = 15.2 Hz), 6.15 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 5.27 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 8.0 Hz), 4.48–4.50 (m, 1 H), 3.65 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.6, 11.6 Hz), 2.93 (dd, 1 H, J = 1.6, 11.6 Hz), 2.36–2.42 (m, 2 H), 1.53–1.58 (m, 2 H), 1.42–1.50 (m, 2 H), 0.98 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 153.5, 152.9, 151.8, 151.2, 143.9, 120.1, 117.4, 78.8, 74.4, 63.9, 36.3, 32.0, 32.1, 23.4, 14.3; [α]25D −71.56 (c 0.10, MeOH); (ESI+) (M+H+) m/z 336.1494; Anal. calcd for C15H21N5O2S: C, 53.71; H, 6.31; N, 20.88; S, 9.56. Found: C, 53.56; H, 6.33; N, 20.67; S, 9.45.

Pharmacology

In vitro assays

Cell culture and membrane preparation

CHO cells stably expressing either the recombinant hA1 or hA3AR and HEK-293 cells stably expressing the human A2AAR were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) and F12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 μmol/mL glutamine. In addition, we added 800 μg/mL Geneticin to the hA2AAR media and 500 μg/mL Hygromycin B to the hA1AR, hA2BAR, and hA3AR media. After harvesting the cells, we centrifuged them at 250g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), containing 10 mM MgCl2. The suspension was homogenized with an electric homogenizer for 10 s and was then recentrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The resultant pellet was homogenized again, resuspended in the buffer mentioned above in the presence of 3 U/mL adenosine deaminase, finally pipetted into 1 mL vials, and stored at −80°C until the binding experiments were conducted. The concentration of protein was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL).24

Radioligand binding assay

Radioligand binding assays with A1, A2A, and A3ARs were performed according to the procedures described previously.25–27 Briefly, for binding to human A1 receptors, [3H]PIA (1 nM) was incubated with membranes (40 μg/tube) from CHO cells stably expressing human A1 receptors at 25 °C for 60 min in 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4; MgCl2, 10 mM) in a total assay volume of 200 μL. Nonspecific binding was determined using 10 μM of 25. For human A2A receptor binding, membranes (20 μg/tube) from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human A2AARs were incubated with 15 nM [3H]26 at 25 °C for 60 min in 200 μl 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, containing 10 mM MgCl2. Reaction was terminated by filtration with GF/B filters. For competitive binding assay to human A3ARs, each tube contained 100 μL suspension of membranes (20 μg protein) from CHO cells stably expressing the human A3AR, 50 μL of [125I]27 (0.5 nM), and 50 μL of increasing concentrations of the nucleoside derivative in Tris·HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA. Nonspecific binding was determined using 10 μM of 25 in the buffer. The mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 60 min. Binding reactions were terminated by filtration through Whatman GF/B filters under reduced pressure using a MT-24 cell harvester (Brandell, Gaithersburgh, MD, USA). Filters were washed three times with 9 mL ice-cold buffer. Radioactivity was determined in a Beckman 5500B γ-counter.

For binding at all three subtypes, Ki values are expressed as mean ± sem, n = 3–5 (outliers eliminated), and normalized against a non-specific binder, 10 μM 25. Alternately, for weak binding a percent inhibition of specific radioligand binding at 10 μM, relative to inhibition by 10 μM 25 assigned as 100%, is given.

cAMP accumulation assay

Intracellular cAMP levels were measured with a competitive protein binding method.28 CHO cells that expressed the recombinant hA2AAR, hA2BAR, or hA3AR were harvested by trypsinization. After centrifugation and resuspended in medium, cells were planted in 24-well plates in 1.0 mL medium. After 24 h, the medium was removed and cells were washed three times with 1 mL DMEM, containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Cells were then treated with the test agonist in the presence of rolipram (10 μM) and adenosine deaminase (3 units/mL). For the hA2AAR and the hA2BAR, incubation with agonist was performed for 30 min. For the hA3AR, after 30 min forskolin (10 μM) was added to the medium, and incubation was continued for an additional 15 min. The reaction was terminated by removing the supernatant, and cells were lysed upon the addition of 200 μL of 0.1 M ice-cold HCl. The cell lysate was resuspended and stored at −20°C. For determination of cAMP production, 100 μl of the HCl solution was used in the Sigma Direct cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay following the instructions provided with the kit. The results were interpreted using a Bio-Tek Instruments ELx808 Ultra Microplate reader at 405 nm.

Data analysis

Binding and functional parameters were calculated using the Prism 5.0 software (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA, USA). IC50 values obtained from competition curves were converted to Ki values using the Cheng-Prusoff equation.29 Data were expressed as mean ± standard error.

In vivo assay of anti-inflammatory effect

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (140~160 g, 5 weeks old) were purchased from Central Laboratory Animal Inc. (Seoul, Korea). Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions with free access to food and water. The temperature was thermostatically regulated to 22 °C ± 2 °C, and a 12-hour light/dark schedule was maintained. Prior to their use, they were allowed one week for acclimatization within the work area environment. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines of Seoul National University (SNU-201110-4).

Carrageenan-induced paw edema

Carrageenan-induced hind paw edema model in rats was used for the assessment of anti-inflammatory activity.30 Test compounds 4g (20 mg/kg) and indomethacin (20 mg/kg) were administered by an intraperitoneal injection dissolved in 5% cremophor and 5% ethanol in PBS, and solvent alone was served as a vehicle control. Thirty minutes after the administration of 4g, vehicle, or indomethacin, paw edema was induced by subplantar injection of 0.1 mL of 1% freshly prepared carrageenan suspension in normal saline into the right hind paw of each rat. The left hind paw was injected with 0.1 mL of normal saline. The paw volume was measured before (0 h) and at intervals of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 24 h after carrageenan injection using a plethysmometer (Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy).

Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data were presented as means ± SD for the indicated number of independently performed experiments. The statistical significances within a parameter were evaluated by one-way and multiple analysis of variation (ANOVA).

Molecular modeling

The 3D structures of the molecules were generated with Concord and energy minimized using MMFF94s force field and MMFF94 charge until the rms of Powell gradient was 0.05 kcal mol−1A−1 in SYBYL-X 1.2 (Tripos International, St. Louis, MO, USA). The X-ray crystal structure of the A2AAR (PDB ID: 3EML) was prepared by Biopolymer Structure Preparation Tool in SYBYL. The docking study was performed using GOLD v.5.0.1 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK), which employs a genetic algorithm (GA) and allows for full ligand flexibility and partial protein flexibility. The region of 9 Å around the co-crystallized ligand was defined as the binding site. The side chains of the eight residues (i.e., Thr88, Phe168, Glu169, Trp246, Leu249, Asn253, Ser277, and His278), which are important for ligand binding, were set to be flexible with ‘crystal mode’. GoldScore scoring function was used and other parameters were set as default except the number of GA runs as 30. The Fast Connolly surface of the receptor and the van der Waals surface of each ligand were generated by MOLCAD in SYBYL. All computation calculations were undertaken on Intel® Xeon™ Quad-core 2.5 GHz workstation with Linux Cent OS release 5.5.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5a.

Reagents and conditionsa: a) (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene, (Ph3P)4Pd, Na2CO3, DMF, H2O, 90 °C, 15 h; b) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from Basic Science Research (2008-314-E00304), the National Core Research Center (2011-0006244), the World Class University (R31-2008-000-10010-0), National Leading Research Lab Program (2011-0028885), and Brain Research Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research (2011K000289) from National Research Foundation (NRF), Korea, and the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

adenosine receptor

- Cl-IB-MECA

2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine

- Thio-Cl-IB-MECA

2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyl-4′-thioadenosine

- TMSOTf

trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- R-PIA

(−)-N6-2-phenylisopropyl adenosine

- I-AB-MECA

N6-(3-iodo-4-aminobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- HMDS

hexamethyldisilazane

- BSA

N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine-5′-monophosphate

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Scheme 1S for the mechanism of lithiation mediated stannyl transfer for the formation of 7. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Olah ME, Stiles GL. The role of receptor structure in determining adenosine receptor activity. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85:55–75. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredholm BB, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P. Pharmacology of adenosine receptors and therapeutic applications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;3:413–426. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Romagnoli R, Merighi S, Varani K, Borea PA, Spalluto G. A3 adenosine receptor ligands: history and perspectives. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:103–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200003)20:2<103::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HO, Ji X-d, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jeong LS, Jin DZ, Kim HO, Shin DH, Moon HR, Gunaga P, Chun MW, Kim YC, Melman N, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted D-4′-thioadenosine-5′-methyluronamides: Potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3775–3777. doi: 10.1021/jm034098e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong LS, Lee HW, Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Shin DH, Lee JA, Gao Z-G, Lu C, Duong HT, Gunaga P, Lee SK, Jin DZ, Chun MW, Moon HR. Structureactivity relationships of 2-chloro-N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosine-5′-uronamides as highly potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:273–281. doi: 10.1021/jm050595e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Park EJ, Shin DH, Jeong LS, Lee SK. A novel adenosine analog, thio-Cl-IB-MECA, induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005; 70: 918–924. (b) Bar-Yehuda, S., Stemmer, S. M., Madi, L., Castel, D., Ochaion, A., Cohen, S., Barer, F., Zabutti, A., Perez-Liz, G., Del Valle, L., Fishman, P. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF102 induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via de-regulation of the Wnt and NF-κB signal transduction pathways, Int. J. Oncol. 2008; 33: 287–295. (c) Kohno, Y., Sei, Y., Koshiba, M., Kim, H. O., Jacobson, K. A. Induction of apoptosis in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells by selective adenosine A3 receptor agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;219:904–910. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SK, Jacobson KA. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship of nucleosides acting at the A3 adenosine receptor: Analysis of binding and relative efficacy. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1225–1231. doi: 10.1021/ci600501z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong LS, Choe SA, Gunaga P, Kim HO, Lee HW, Lee SK, Tosh DK, Patel A, Palaniappan KK, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Moon HR. Discovery of a new nucleoside template for human A3 adenosine receptor ligands: D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives without 4′-hydroxymethyl group as highly potent and selective antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2007; 50: 3159–3162. (b) Jeong, L. S., Pal, S., Choe, S. A., Choi, W. J., Jacobson, K. A., Gao, Z.-G., Klutz, A. M., Hou, X., Kim, H. O., Lee, H. W., Tosh, D. K., Moon. H. R. Structure-activity relationships of truncated D- and L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives as species-independent A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2008; 51: 6609–6613. (c) Pal, S., Choi, W. J., Choe, S. A., Heller, C. L., Gao, Z.-G., Chinn, M., Jacobson, K. A., Hou, X., Lee, S. K., Kim, H. O., Jeong, L. S. Structure-activity relationships of truncated adenosine derivatives as highly potent and selective human A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009; 17: 3733–3738. (d) Jacobson, K. A., Siddiqi, S. M., Olah, M. E., Ji, X. d., Melman, N., Bellamkonda, K., Meshulam, Y., Stiles, G. L., Kim, H. O. Structure-activity relationships of 9-alkyladenine and ribose-modified adenosine derivatives at rat A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1720–1735. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Do CW, Avila MY, Peterson-Yantorno K, Stone RA, Gao ZG, Joshi B, Besada P, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA, Civan MM. Nucleoside-derived antagonists to A3 adenosine receptors lower mouse intraocular pressure and act across species. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou X, Kim HO, Alexander V, Kim K, Choi S, Park S, Lee JH, Yoo LS, Gao Z, Jacobson KA, Jeong LS. Discovery of a new human A2A adenosine receptor agonist, truncated 2-hexynyl-4′-thioadenosine. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:516–520. doi: 10.1021/ml1001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sitkovsky MV, Lukashev D, Apasov S, Kojima H, Koshiba M, Cladwell C, Ohta A, Thiel M. Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia-inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2004; 22: 657–682. (b) Lappas, C. M., Sullivan, G. W., Linden, J. Adenosine A2A agonists in development for the treatment of inflammation. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2005;14:797–806. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Kato K, Hayakawa H, Tanaka H, Kumamoto H, Shindoh S, Shuto S, Miyasaka T. A new entry to 2-substituted purine nucleosides based on lithiation-mediated stannyl transfer of 6-chloropurine nucleosides. J Org Chem. 1997;62:6833–6841. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brun V, Legraverend M, Grierson DS. Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors: development of a general strategy for the construction of 2,6,9-trisubstituted purine libraries. Part 1. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:8161–8164. [Google Scholar]; (c) Taddei D, Kilian P, Slawin AMZ, Woollins D. Synthesis and full characterization of 6-chloro-2-iodopurine, a template for the functionalisation of purines. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:665–670. doi: 10.1039/b312629c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinchilla R, Nájera C. The Sonogashira reaction: A booming methodology in synthetic organic chemistry. Chem Rev. 2007;107:874–922. doi: 10.1021/cr050992x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki A. Carbon-carbon bonding made easy. Chem Commun. 2005;38:4759–4763. doi: 10.1039/b507375h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboronates with vinylic halides: (1Z,3E)-1-phenyl-1,3-octadiene. Org Syn Coll Vol. 1993;8:532–534. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laxer A, Major DT, Gottlieb HE, Fischer B. (15N5)-Labeled adenine derivatives: Synthesis Studies of Tautomerism by 15N NMR Spectroscopy Theoretical Calculations. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5463–5481. doi: 10.1021/jo010344n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]