Abstract

Primary sarcomas of the pancreas are extremely rare, accounting for 0.1% of malignant pancreatic (non-islet) neoplasms. Pancreatic leiomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive malignancy that spreads in a similar manner to gastric leiomyosarcoma, i.e., by adjacent organ invasion, hematogenous spread, and lymph node metastasis. These tumors are large at the time of diagnosis and are usually found at an advanced stage. We report a case of a 70-year-old female with intermittent right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. Radiological, histopathological, and immunohistochemical studies revealed the tumor to be a primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. Herein, we describe a patient with a primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas who presented with clinical and radiological findings indicative of a mass in the pancreatic head.

Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma, Pancreas, Primary

INTRODUCTION

Most of the malignant tumors of the pancreas are adenocarcinomas arising from the ductal epithelium. Although a primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma is the most common sarcoma of the pancreas, it is rare and accounts for only 0.1% of malignant pancreatic cancers [1]. Since 1951, when Rose [2] presented the first case, less than 50 cases have been reported in the English literature [3-5]. In the Korean literature, only one case has been reported until now [6]. The majority of the reported cases are diagnosed on autopsy. Herein, we present a case of primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma occurring in a 70-year-old female.

CASE REPORT

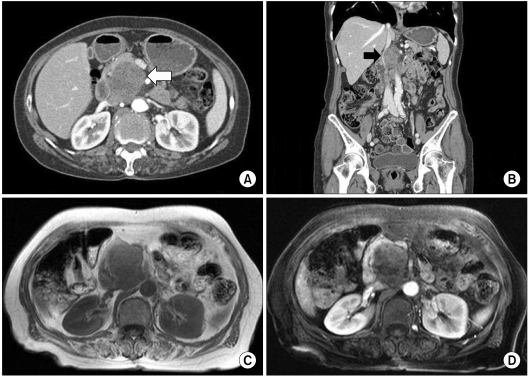

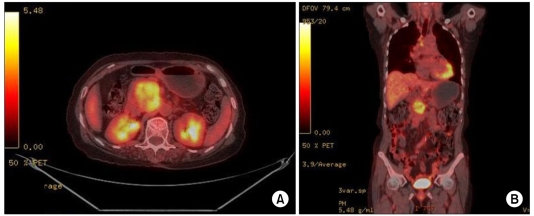

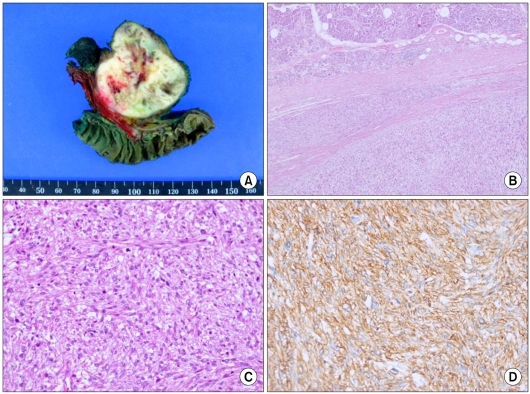

A 70-year-old woman presented with intermittent right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. Her complaints had been intermittently present for several months before admission. She was recently diagnosed with hypertension. A physical examination revealed no characteristic features. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 4.5 × 5 cm heterogeneous enhancing mass arising from the pancreatic head (Fig. 1A, B). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pancreas showed a 5.3 × 4 cm heterogenously enhanced mass that was abutting to the superior mesenteric vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) (Fig. 1C, D). No focal enhancing mass was observed in the liver, and there was an enlarged lymph node in the abdominal cavity. Whole body [18F]-fluoro-deoxy glucose positron emission tomography (PET)/CT demonstrated a 5.6 × 3.8 cm sized hypermetabolic mass arising from the pancreatic head in the retropancreatic space (Fig. 2). Laboratory data revealed that renal function was normal and tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9) were normal. The initial diagnosis was pancreatic head cancer or a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. On laparotomy, a 5 × 5 cm multiseptated mass had adhered to the IVC and left renal vein without evidence of peritoneal dissemination or hepatic metastasis. A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy with regional lymph node dissection was performed. Macroscopically, the mass had arisen from the pancreatic head and was limited to the pancreas. The cut surface of the tumor was whitish and showed signs of internal hemorrhage and partial myxoid change (Fig. 3A). Microscopically, nuclear atypia and pleomorphism were marked in the more dense cellular area, where frequent mitotic figures (up to 10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields [HPFs]) could be identified (Fig. 3B, C). The resected peripancreatic lymph node and surgical margins were free of tumor. A immunohistochemical examination showed positive staining for actin (Fig. 3D), vimentin, and focal staining for desmin. However, CK, S-100, CD34, c-kit, and myogenin were negative. Finally, the tumor was diagnosed as a primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan shows growth of the tumor, which is heterogeneously enhanced by contrast media (A, white arrow). CT scan shows the tumor, which is abutting to the inferior vena cava (B, black arrow). Magnetic resonance imaging shows a 5.3 × 4 cm heterogenously enhanced mass (C, D).

Fig. 2.

Whole body [18F]-fluoro-deoxy glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography demonstrates a 5.6 × 3.8 cm size hypermetabolic mass arising from the pancreatic head in the retropancreatic space.

Fig. 3.

The gross pathological examination reveals a 5 × 5 cm multiseptated mass in the pancreatic head. The cut surface of the tumor is whitish and shows signs of internal hemorrhage and partial myxoid change (A). Interface of tumor (left) and compressed adjacent pancreatic tissue with fibrosis (B, H&E, ×40). The mass contains interlacing spindle-shaped cells with varying degrees of pleomorphism and atypia (C, H&E, ×200). The immunohistochemical findings show strong immunoreactivity of the tumor cells to actin (D, labeled streptavidin-biotin, original magnification ×200).

The patient was discharged on postoperative day 22 with an uneventful recovery. Six months later, a follow-up enhanced abdominal CT scan revealed multiple irregular ill-defined metastatic lesions in the liver, a 2.6 cm enhancing nodule invading the inferior vena cava in the aortocaval space, and focal thrombi in IVC. She refused any additional adjuvant chemotherapy and had received palliative radiotherapy. However, she was re-admitted due to aggravation of hepatic metastasis and tumoral thrombi in IVC with obstruction, and died 22 months after the surgery.

DISCUSSION

Leiomyosarcomas involving the pancreas consist of a primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma or pancreatic extensions of a retroperitoneal and gastroduodenal sarcoma [1]. Leiomyosarcomas originating from other organs such as the stomach, duodenum, and retroperitoneal organs often invade the pancreas, simulating a primary tumor of the pancreas. Therefore, to diagnose a primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas, it is essential to rule out a tumor arising from other surrounding organs [3]. In the present case, the tumor was predominantly located in the head of the pancreas, and the CT scan, MRI, whole body PET/CT, and operative findings showed no evidence of a mass originating from any other adjacent organs. The pancreatic origin of the leiomyosarcoma was thus confirmed.

A pancreatic leiomyosarcoma is more common in the fifth decade of life or older (mean age, 44.7 years; range, 14 to 80 years). Males are affected almost twice as much as females (7:4). The size of tumors is rather variable ranging from 3 to 25 cm (median, 10.5 cm) [5]. Larger tumors can develop cystic degeneration and can be misdiagnosed as pseudocysts of the pancreas [7].

Abdominal pain, weight loss, epigastric tenderness, and an abdominal mass are the most commonly presenting symptoms [7], but these are nonspecific. Imaging studies can also be nonspecific [8]. Abdominal CT scans have revealed solid, cystic and heterogenous images distributed along the pancreatic head, body, and tail [8], and angiography, ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound and MRI are all useful diagnostic imaging methods.

In general, leiomyosarcomas of the pancreas present as large cystic structures. Cystic changes are often associated with hemorrhage or necrosis and may represent degenerative change in a rapidly enlarging solid tumor. Histologically, most tumors showed aggressive features of high cellularity, pleomorphism, and a substantial number of mitosis [4].

An immunohistochemical examination is important for an accurate diagnosis. The diagnosis is based mainly on immunohistochemical characteristics, including expression of specific marker proteins. Stromal tumors are usually diagnosed as myogenic (i.e., leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas) when they are diffusely positive for desmin or smooth muscle action, as neurogenic when positive for the S-100 protein, or as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) when positive for CD117 (c-kit) [9]. Vimentin is not considered specific because this marker protein may be expressed in GIST, myogenic tumors, or neurogenic tumors. In our case, the tumor was positive for actin, desmin (focal), and negative for S-100, CD34, c-kit, indicating immunohistochemical features compatible with leiomyosarcoma.

A pancreatic leiomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive malignancy that spreads by adjacent organ direct invasion, hematogenous spread, and lymph node metastasis. In addition, these tumors are usually discovered at an advanced stage and have a propensity to invade the surrounding organs and vessels. Therefore, an extended resection such as a pancreatoduodenectomy (for lesions of the head) or a distal pancreatectomy with a splenectomy (for lesions of the body and tail) has been advocated. Complete surgical resection offers the only potential chance of cure for patients with a leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas [3]. As with other leiomyosarcomas, radiation and chemotherapy have met with minimal clinical success.

Large tumor size is not a precise predictor of adverse outcome. In leiomyomatous tumors, mitotic figures have been suggested to be the most important predicting parameter [10]. Mitotic counts of more than 10 mitoses/10 HPFs are associated with a worse outcome [1].

In summary, a primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas is extremely rare. Most pancreatic stromal tumors are GISTs or neurogenic tumors. The diagnosis of pancreatic leiomyosarcoma is confirmed by ruling out a tumor arising from other surrounding organs (i.e., stomach, duodenum, and other retroperitoneal organs). A detailed clinical evaluation and awareness of primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma will be helpful to distinguish this malignant tumor from other stromal tumors originating from other organs.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Baylor SM, Berg JW. Cross-classification and survival characteristics of 5,000 cases of cancer of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 1973;5:335–358. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross CF. Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1951;39:53–56. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003915311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aihara H, Kawamura YJ, Toyama N, Mori Y, Konishi F, Yamada S. A small leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas treated by local excision. HPB (Oxford) 2002;4:145–148. doi: 10.1080/136518202760388064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komoda H, Nishida T, Yumiba T, Nishikawa K, Kitagawa T, Hirota S, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas--a case report and case review. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:334–337. doi: 10.1007/s00428-001-0557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhammad SU, Azam F, Zuzana S. Primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:280. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin BK, Moon JS, Oh HE, Won NH, Choi JS. Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 1999;33:733–736. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato T, Asanuma Y, Nanjo H, Arakawa A, Kusano T, Koyama K, et al. A resected case of giant leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:223–227. doi: 10.1007/BF02358688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane RH, Stephens DH, Reiman HM. Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms: CT findings in 90 cases with clinical and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:83–89. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors--definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s004280000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aranha GV, Simples PE, Veselik K. Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:95–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02788364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]