Background: Histone methyltransferases are key regulators in cell growth and gene expression.

Results: We identified a charge-based protein-protein interaction within a histone H3K4 methyltransferase complex that is critical for protein stability and histone methylation.

Conclusion: Charge-based protein-protein interactions are conserved among histone methyltransferases and are required for their function.

Significance: This study helps determine how histone methyltransferase complexes are assembled and how they function.

Keywords: Chromatin, Gene Regulation, Histone Methylation, Histone Modification, Histones, Acidic And Basic Amino Acids, Charge-based Interactions, H3K4 Methylation, Protein-Protein Interactions, Telomere Silencing

Abstract

Histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferases are conserved from yeast to humans, assemble in multisubunit complexes, and are needed to regulate gene expression. The yeast H3K4 methyltransferase complex, Set1 complex or complex of proteins associated with Set1 (COMPASS), consists of Set1 and conserved Set1-associated proteins: Swd1, Swd2, Swd3, Spp1, Bre2, Sdc1, and Shg1. The removal of the WD40 domain-containing subunits Swd1 and Swd3 leads to a loss of Set1 protein and consequently a complete loss of H3K4 methylation. However, until now, how these WD40 domain-containing proteins interact with Set1 and contribute to the stability of Set1 and H3K4 methylation has not been determined. In this study, we identified small basic and acidic patches that mediate protein interactions between the C terminus of Swd1 and the nSET domain of Set1. Absence of either the basic or acidic patches of Set1 and Swd1, respectively, disrupts the interaction between Set1 and Swd1, diminishes Set1 protein levels, and abolishes H3K4 methylation. Moreover, these basic and acidic patches are also important for cell growth, telomere silencing, and gene expression. We also show that the basic and acidic patches of Set1 and Swd1 are conserved in their human counterparts SET1A/B and RBBP5, respectively, and are needed for the protein interaction between SET1A and RBBP5. Therefore, this charge-based interaction is likely important for maintaining the protein stability of the human SET1A/B methyltransferase complexes so that proper H3K4 methylation, cell growth, and gene expression can also occur in mammals.

Introduction

The yeast Set1 histone H3K43 methyltransferase complex comprises the proteins Set1, Swd1, Swd2, Swd3, Bre2, Sdc1, Shg1, and Spp1 (1, 2). Deletion of any of these components, except for Shg1, was found to have significant but varying effects on H3K4 methylation and Set1 protein levels (3–6). Swd1 and Swd3 are the only Set1 complex components consistently observed to be necessary for all three states of methylation as well as for wild-type levels of Set1 protein (3–5). Importantly, multiple Set1-like H3K4 methyltransferase complexes have been identified in humans and have been implicated in human diseases. These include the MLL family (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, and MLL4) and SET1 family (SET1A and SET1B) of H3K4 methyltransferase complexes (7–10). The human homologs of the yeast Set1 complex components are as follows: RBBP5 (Swd1), WDR82 (Swd2), WDR5 (Swd3), CFP1/CGBP (Spp1), DPY30 (Sdc1), and ASH2L (Bre2) (7–10).

Several studies have focused on the contribution of the WD40 domain-containing subunits (RBBP5 (Swd1), WDR82 (Swd2), and WDR5 (Swd3)) of Set1 histone methyltransferase complexes to H3K4 methylation. WD40 domain-containing proteins typically form β-propeller-like structures that act as scaffolds upon which protein complexes can be built. Mammalian RBBP5 and WDR5 are important for efficient H3K4 methylation by MLL1 both in vitro and in vivo (5, 7, 11, 12). Several biochemical and structural studies have shown that the β-propeller-like structure of WDR5 has an arginine binding pocket that can associate with N-terminal residues of histone H3 and MLL by its WDR5 interaction motif (7, 11, 13–19). Unlike WDR5, the C terminus of RBBP5, a region outside of the WD40 domains, is important for protein-protein interactions and can interact with ASH2L and WDR5 (7, 20). Other studies have also shown that RBBP5, together with WDR5, ASH2L, and DPY30, significantly facilitates MLL1 methyltransferase activity on histone H3K4, suggesting that RBBP5 forms a stable complex with WDR5, ASH2L, and DPY30 (21, 22). In contrast to RBBP5 and WDR5, yeast Swd1 and Swd3 are essential for all H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation (3, 5). The complete loss of H3K4 methylation in Swd1 or Swd3 deletion yeast strains is likely a result of losing Set1 protein levels due to decreased protein stability (3, 5). Altogether these studies suggest that these subunits are critical for histone methyltransferase activity, additional biochemical studies are needed to understand how the various H3K4 methyltransferase complexes are assembled and mediate histone methylation.

In this study, we focused on defining the mechanism of an interaction between Set1 and the WD40 domain-containing subunit Swd1. We discovered that two patches of acidic residues found in the C-terminal tail of Swd1, a region that is separated from the WD40 domains, are important for maintaining proper Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation in vivo. Loss of these regions resulted in defects in cell growth, telomere silencing, and gene expression. In vitro binding studies showed that these regions are necessary for the interaction between Set1 and Swd1. In addition, we identified a basic patch consisting of four basic amino acids in the nSET domain of Set1 that is also crucial for maintaining Set1 protein levels and histone methylation as well as for in vitro interaction with Swd1. Importantly, conserved mutations within this basic patch resulted in the retention of the ability of Set1 to bind to Swd1. Conversely, mutating the basic patch amino acids into acidic amino acids greatly reduced binding. These in vitro results together with our in vivo data show that acidic and basic patch interaction between Set1 and Swd1 is essential for proper Set1 protein levels, histone methylation, and gene expression. Furthermore, we found that the acidic patches in Swd1 and the basic patch in Set1 are conserved in their human homologs RBBP5 and SET1A/B, and these patches are also needed to mediate the interaction of RBBP5 and SET1A in vitro, suggesting that this mode of protein interaction is functionally conserved from yeast to mammals.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Strains

All yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are described in the supplemental methods and supplemental Tables S1 and S2. Bacterial and yeast plasmids for full-length SET1 and SWD1 were made by PCR amplification from yeast genomic DNA. The wild-type SET1 for in vivo methylation studies was constructed by PCR amplification from yeast genomic DNA extracted from the yeast strain MBY1282 in which Set1 has been engineered with an integrated triple MYC (3XMYC) tag at the N terminus. 500 bp of upstream sequence and 250 bp of downstream sequence were included in the PCR product. SET1 was cloned into the yeast expression vector pRS415. SWD1 constructs were engineered with a single 3′ hemagglutinin (HA) sequence and subcloned into the yeast expression vector pRS415 or pRS416 containing an ADH1 promoter (pRS415/ADH1p or pRS416/ADH1p). For co-immunoprecipitation studies using the baculovirus expression system, SET1, SWD1, and SWD3 were PCR-amplified from SET1, SWD1, and SWD3 yeast expression constructs and subcloned into the vector pVL1392 or pVL1393 as described in the supplemental methods. For in vitro binding studies, the SET1 nSET domain and nSET domain mutants were PCR-amplified using a SET1 yeast expression construct as the template and subcloned into a pGEX2T vector. All set1 and swd1 deletions and point mutants used in this study were generated either by PCR amplification or by using the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method using SET1- and SWD1-containing plasmids as templates.

Yeast Extraction and Immunoblot Analysis

Yeast extraction and immunoblot analysis to detect modified histones were performed as described previously (23, 24). α-H3K4me1 (07-463), α-H3K4me2 (07-030), and α-H3K4me3 (07-473) were obtained from Millipore and used at 1:2500, 1:10,000, and 1:5000 dilutions, respectively. The α-H3 antibody was obtained from Abcam (Ab1791) and used at a 1:10,000 dilution. The monoclonal α-HA.11 antibody (Covance, MMS-101R) was used at a 1:5000 dilution. The rabbit α-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-805) was used at a 1:2500 dilution. The monoclonal α-MYC antibody (9E10; Roche Applied Science, 11 667 203 001) was used at a 1:5000 dilution. The monoclonal α-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-138) was used at a 1:5000 dilution. The monoclonal α-His antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8036) was used at a 1:5000 dilution. The rabbit α-glucose-6-phoshate dehydrogenase antibody (Sigma, A9521) was used at a 1:50,000 dilution.

Immunoprecipitation of Set1

For immunoprecipitation of episomally expressed 3XMYC-tagged Set1 or 3XMYC-Set1 expressed from its endogenous locus, 50-ml cultures were grown to midlog phase (A600 = 0.6). Whole-cell lysates were prepared by bead beating in buffer A (40 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 350 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF), and protein levels were normalized by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). 2× SDS sample buffer was added to an aliquot of lysate to analyze protein loading by immunoblotting for H3 levels (Abcam, Ab1791). Lysates were rotated with 2 μg of α-MYC antibody (9E10; Roche Applied Science, 11 667 203 001) for 2 h at 4 °C. 12 μl of Protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, 17-0618-01) were added, and the lysates were rotated for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitated resin was washed twice with 1 ml of lysis buffer and resuspended in 12 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled, centrifuged, and loaded on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After transfer to a PVDF membrane, Set1 was detected by immunoblotting with an α-MYC antibody as described above.

Gene Expression Analysis

Quantitative real time PCR was performed as described previously (25). Briefly, 6-ml cultures were grown to midlog phase, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol. 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The real time PCR mixture contained 6.25 μl of SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems), 0.125 μl of forward and reverse primers from a 5 μm stock, 5.5 μl of sterile water, and 0.5 μl of cDNA for a total volume of 12.5 μl. DNA was amplified in a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the following program: an initial hold of 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Three biological repeats with three technical repeats each were analyzed for each sample. Data were analyzed with the ΔΔCt method in which actin (ACT1) was used as an endogenous control, and the relative quantity of SET1, SWD1, or MDH2 for each strain was compared with SET1, SWD1, or MDH2 transcript in a wild-type strain. Primer sequences used for PCR amplification are described in supplemental Table S3.

Growth and Silencing Assays

Yeast strains MSY421, MBY1587, and SDBY1146 were transformed with plasmids to express wild-type 3XMYC-Set1, 3XMYC-set1ΔKRKK, wild-type Swd1-HA, swd1-HAΔAP1, swd1-HAΔAP2, or empty vector. Cells were grown overnight, back-diluted to A600 = 1.0, serially diluted 5-fold, and plated on SC-Ura or SC-Leu plates as indicated. Cells were photographed after 36 h at 30 °C. Telomere silencing assays were performed as described previously (23, 26). Briefly, strains UCC506, UCC506 set1Δ, and SDBY1147 were transformed with the above plasmids. Individual isolates were grown to saturation in SC-Leu medium, back-diluted to A600 = 1.0, and serially diluted 5-fold. Cells were plated on SC-Leu or SC-Leu plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (100 μg/ml; Bio101, Inc.). Cell growth was monitored over time at 30 °C. Cells on SC-Leu plates were photographed after 24 h, and cells grown on SC-Leu + 5-FOA plates were photographed after 60 h.

Co-immunoprecipitation Analysis

For Set1 and Swd1 co-immunoprecipitation assays, 60 μl each of Set1 and Swd1 viruses bearing pDPM38, pDPM39, pDPM40, pDPM41, and pDPM42 constructs were incubated with 2 × 106 Sf9 cells plated on 60-mm tissue culture dishes in 3 ml of Grace's medium for 48 h at 27 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min, washed with ice-cold sterile 1× PBS, and flash frozen with liquid nitrogen. Nuclei were extracted by lysing the cells with 1 ml of buffer B (20 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF). Lysates were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. Nuclei were resuspended in 400 μl of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 300 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF) and rotated at 4 °C for 30 min. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at full speed for 5 min at 4 °C. 15 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer were added to 50 μl of nuclear lysate for a protein loading control. Lysates were rotated with 2 μg of α-MYC antibody (9E10; Roche Applied Science, 11 667 203 001) for 2 h at 4 °C. 12 μl of Protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, 17-0618-01) were added, and the lysates were rotated for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitated resin was washed twice with 1 ml of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer and resuspended in 12 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled, centrifuged, and loaded on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After transfer to PVDF membrane, Swd1 was detected by immunoblotting with a rabbit α-HA antibody as described above. To determine the protein levels of Set1 and Swd1, the reserved nuclear lysate was run on 8 and 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to PVDF membranes, and immunoblotted with α-MYC and α-HA.11 antibodies.

Co-immunoprecipitation assays to detect interaction between Set1 truncation mutant Set1(690–1080) and Swd1 or between Swd1 and Swd3 were performed in a similar manner with the following modification. Nuclear lysates were incubated with 12 μl of M2 α-FLAG resin (Sigma, A2220) and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h with rotation. The resin was washed twice with 1 ml of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer and then resuspended in 12 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled, centrifuged, loaded on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes. Swd1 was detected by immunoblotting with a rabbit α-HA antibody as described above.

In Vitro Binding Analysis

GST, GST-nSET, and GST-nSET mutants as well as GST-hSET1A-nSET and GST-MLL1-nSET were bacterially expressed in the pRARE BL21 bacterial strain. Briefly, 100 μl of an overnight bacterial culture were added to 5 ml of LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. Cultures were grown for 1 h at 37 °C. Isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to 0.1 mm, and cultures were incubated overnight at 18 °C. His-tagged Swd1, Swd1ΔAP1, Swd1ΔAP2, Swd1ΔAP1ΔAP2, RBBP5, RBBP5ΔAP1, RBBP5ΔAP2, or RBBP5ΔAP1ΔAP2 mutant constructs were expressed in the BL21(DE3) bacterial strain. The protein expression procedure was similar to that described above except that isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to 0.4 mm, and bacterial cultures were incubated for 4 h at room temperature. GST pulldown assays were performed as described previously (27, 28). Briefly, GST, GST-nSET, GST-nSET mutants, GST-hSET1A-nSET, or GST-MLL1-nSET proteins were incubated with glutathione-agarose beads and washed with buffer C (300 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF). After washing, beads were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with either 400 μl of Sf9 nuclear extracts containing empty vector, Swd1, or Swd1 mutants; bacterial extracts containing Swd1 or Swd1 mutants; or bacterial extracts containing RBBP5 or RBBP5 mutants. Beads were washed two times in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, resuspended in 13 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer, and boiled for 5 min. Samples were run on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblots were analyzed using α-His or α-HA antibody. For protein loading controls, 15 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer were added to 50 μl of bacterial or Sf9 nuclear lysate and analyzed by immunoblotting with α-His or α-HA antibody and/or Coomassie staining.

RESULTS

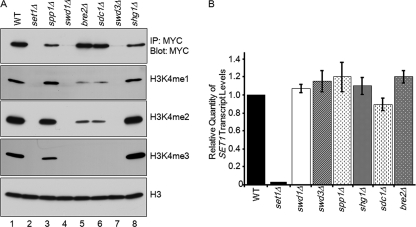

Set1 Complex Members Are Required to Maintain Proper H3K4 Methylation and Set1 Protein Levels

In the absence of SWD1 or SWD3, global H3K4 methylation is undetectable, and Set1 protein levels are greatly diminished (3–5, 6) (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 7). However, the question of whether the observed decrease in Set1 protein levels in swd1 and swd3 deletion strains was a consequence of lower Set1 transcript levels or lower protein levels had not been properly determined. To address this issue, we made gene deletions of each of the yeast Set1 complex members in a strain expressing Set1 that was 3XMYC-tagged at its endogenous locus. Consistent with previous reports, we show that deletion of SWD1 or SWD3 resulted in no detectable mono-, di-, or trimethylation, whereas deletion of BRE2 or SDC1 resulted in no detectable trimethylation and a reduction in mono- and dimethylation (Fig. 1A, lanes 4–7) (3–5, 30). Deletion of SPP1 resulted in a slight decrease in trimethylation, and deletion of SHG1 had no apparent affect on H3K4 methylation (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 8). The changes in H3K4 methylation were likely not due to uneven protein loading because an immunoblot showed near equivalent loading of histone H3 (Fig. 1A). Although others have indicated by whole-cell approaches that Set1 levels were diminished in swd1 and swd3 deletion strains, we decided to take a more stringent approach to determine how much Set1 protein was remaining in these cells. Therefore, Set1 was immunoprecipitated from each of the Set1 complex component deletion strains to determine whether Set1 protein levels were affected similarly to what others have seen (3, 5). Approximately equivalent amounts of Set1 were immunoprecipitated from bre2Δ and sdc1Δ strains when compared with a wild-type strain (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). However, Set1 protein levels were slightly decreased in spp1Δ and shg1Δ strains (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 8). In contrast, almost no Set1 protein was immunoprecipitated from swd1Δ and swd3Δ strains (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 7). To make sure differences in Set1 protein levels were not due to differences in the total amount of protein, whole-cell lysates were normalized by Bradford assay before immunoprecipitation analysis, and histone H3 immunoblots were used to control for protein loading (Fig. 1A). Importantly, these results help support and confirm the previous reports using whole-cell approaches (3, 5).

FIGURE 1.

Swd1 is necessary for proper levels of Set1 protein and H3K4 methylation but not Set1 transcript. A, 3XMYC-tagged Set1, expressed from its endogenous chromosomal locus, was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole-cell lysates prepared from the indicated strains. Protein levels of MYC-tagged Set1 were determined by immunoblotting with an α-MYC antibody. Whole-cell lysates generated from the indicated strains were immunoblotted with H3K4 mono- (me1), di- (me2), and trimethyl (me3) antibodies. Histone H3 immunoblots were used for a loading control. B, transcript levels of 3XMYC-SET1 expressed at its endogenous chromosomal locus were examined in the indicated Set1 complex component deletion strains by quantitative real time PCR. Actin expression was used as an internal loading control. The error bars shown here represent S.D. from six biological repeats with three technical repeats each.

Previous studies have assumed that the observed decrease in Set1 protein levels in swd1 or swd3 deletion strains was a consequence of increased degradation or decreased stability of Set1 protein (31). However, these studies did not determine whether Set1 mRNA transcript levels were affected (31). To test whether this is occurring, Set1 mRNA levels were analyzed in each of the Set1 complex component deletion strains using quantitative real time PCR. Set1 transcript levels in the indicated strains were determined to be approximately equal to Set1 transcript levels in a wild-type strain (Fig. 1B). Importantly, Set1 transcript levels in swd1Δ and swd3Δ strains were not significantly different from Set1 transcript levels in a wild-type strain (Fig. 1B). This suggests that Swd1 and Swd3 do not impact the transcriptional levels of SET1 but are important to mediate proper Set1 protein levels or stability likely by directly interacting with Set1.

C Terminus of Swd1 Is Necessary for H3K4 Methylation and Set1 Protein Levels

Until this study, how Swd1 and Swd3 proteins interact with Set1 and contribute to Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation had not been determined. Although most of the attention is centered on the role of the β-propeller-like structure of the WD40 domains, we were intrigued by the highly acidic C-terminal tail of Swd1. Because C-terminal acidic residues in Dot1 have been shown to be important for Dot1-mediated H3K79 methyltransferase activity, we decided to focus on analyzing the functional importance of the C-terminal tail of Swd1 in histone H3K4 methylation (27, 32).

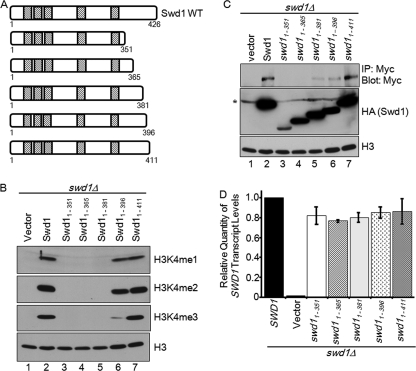

To determine whether the C terminus of Swd1 was important for H3K4 methylation, an HA tag was engineered onto the C terminus of Swd1, and a series of C-terminal truncation constructs were generated and individually expressed in an swd1Δ strain (Fig. 2A). Whole-cell lysates from these strains were first analyzed for mono-, di-, and trimethyl H3K4 levels using immunoblotting. Although full-length Swd1-HA was able to complement the H3K4 methyl phenotype of the swd1Δ strain, Swd1 constructs (Swd1(1–351), Swd1(1–365), and Swd1(1–381)) were unable to restore any detectable methylation, similar to the expression of empty vector in this strain (Fig. 2, A and B, lanes 2–5). An Swd1 construct (Swd1(1–396)) lacking the last 30 amino acids of the C-terminal tail was able to restore mono- and dimethylation to near wild-type levels (Fig. 2B, lane 6). However, trimethylation of H3K4 was decreased relative to wild type (Fig. 2B, lane 6). Finally, expression of a construct lacking only the last 15 amino acid residues of the tail (Swd1(1–411)) was able to restore H3K4 methylation, similar to full-length Swd1 (Fig. 2B, lane 7). An immunoblot for histone H3 shows near equal loading of H3 in all lanes (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

C terminus of Swd1 is important for H3K4 methylation and Set1 protein levels. A, schematic of Swd1 illustrating the positions of the predicted WD40 domains (hash mark boxes). Numbers indicate amino acid positions. B, whole-cell lysates from the indicated strains were immunoblotted with H3K4 mono- (me1), di- (me2), and trimethyl (me3) antibodies. Histone H3 immunoblots were used for a loading control. C, 3XMYC-Set1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole-cell lysates prepared from the indicated strains. Protein levels of 3XMYC-Set1 were determined by immunoblotting with an α-MYC antibody. HA-tagged Swd1 and Swd1 mutants were detected by immunoblotting whole-cell lysates with a rabbit α-HA antibody (the asterisk indicates a nonspecific band). Histone H3 was used as a loading control. D, quantitative real time PCR analysis was used to determine the transcript levels of Swd1 and Swd1 deletion constructs. Actin was used as an internal control. Data represent three biological repeats with three technical repeats each. For B, C, and D, HA-tagged SWD1 and swd1 C-terminal deletion constructs were episomally expressed in an swd1Δ strain with an integrated 3XMYC-SET1 expressed from its endogenous locus. The error bars shown here represent S.D. from three biological samples with three technical repeats each.

To determine whether the C-terminal tail of Swd1 is important for Set1 and Swd1 protein levels, whole-cell lysates were prepared from swd1Δ strains expressing empty vector, full-length Swd1, or Swd1 truncation mutants (Fig. 2A). 3XMYC-tagged Set1 was immunoprecipitated from normalized lysates, and an aliquot from each whole-cell lysate was analyzed for Swd1 expression and H3 levels (Fig. 2C). Although full-length Swd1 was expressed and able to restore Set1 protein levels, the two shortest truncation constructs (Swd1(1–351) and Swd1(1–365)) were expressed at lower levels compared with wild type and were not able to restore Set1 protein levels or histone methylation (Fig. 2, B and C, lanes 2–4). In contrast, the Swd1(1–411) truncation mutant that was able to restore wild-type levels of Swd1 was able to restore wild-type levels of Set1 and histone methylation (Fig. 2, B and C, lane 7), suggesting that the amount of Swd1 protein is important for Set1 protein levels. Interestingly, two Swd1 truncation constructs (Swd1(1–381) and Swd1(1–396)) that have similar levels of Swd1 and Set1 protein, albeit less than wild type, were unable to restore H3K4 methylation or partially restore H3K4 trimethylation (Fig. 2, B and C, lanes 5 and 6). Therefore, the difference in histone methylation between the Swd1(1–381) and Swd1(1–396) strains is likely due to another mechanism that is independent of maintaining Set1 protein levels via Swd1 protein amount (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6). Because protein levels of Swd1(1–351) and Swd1(1–365) were lower than that of wild-type Swd1, quantitative real time PCR was used to determine whether these constructs were being expressed. Our analysis indicated that all five Swd1 truncation constructs were expressed at approximately equivalent amounts (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that the C-terminal tail of Swd1 is important both for maintaining Swd1 and Set1 protein levels and for global H3K4 methylation.

Conserved Patches of Acidic Residues in C-terminal Tail of Swd1 Are Important for H3K4 Methylation and Set1 Protein Levels

Because the C-terminal tail of Swd1 appears to be important for wild-type H3K4 methylation, we analyzed the amino acid sequence of this region to further narrow down the residues that might be important for Set1-mediated H3K4 methylation. Based on our truncation of the C terminus of Swd1, it appeared that the loss of H3K4 methylation and Set1 protein levels correlated with removal of acidic amino acids. To test this idea, four acidic patches containing acidic amino acids within the tail of Swd1 were deleted (Fig. 3A). Empty vector, wild-type Swd1-HA, and the HA-tagged acidic patch mutants were expressed in an swd1Δ strain in which Set1 is 3XMYC-tagged at its endogenous locus. Immunoblot analysis was used to determine the H3K4 methylation status of these various strains. As expected, expression of empty vector in the swd1Δ strain was not able to rescue methylation, whereas expression of wild-type Swd1 was able to restore mono-, di-, and trimethylation (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2). Although Swd1 mutant containing the C-terminal acidic patch (AP) deletion (Swd1ΔAP4) was able to partially restored mono-, di-, and trimethylation (Fig. 3B, lane 5), deletion of the most N-terminal acidic patches (Swd1ΔAP1) resulted in no detectable H3K4 methylation (Fig. 3B, lane 4). Furthermore, an acidic patch deletion encompassing amino acids 366–378 (Swd1ΔAP3) was also not able to rescue H3K4 methylation (Fig. 3B, lane 3). The amino acids necessary for H3K4 methylation in an Swd1ΔAP3 acidic patch mutant were further narrowed down in another acid patch deletion (Swd1ΔAP2) lacking amino acids 372–376 (Fig. 3A). This mutant (Swd1ΔAP2) also could not rescue H3K4 methylation (Fig. 3B, lane 6).

FIGURE 3.

Acidic patches in C-terminal tail of Swd1 are important for H3K4 methylation and Set1 protein levels. A, schematic of Swd1 indicating positions of predicted WD40 repeats (hash mark boxes) and C-terminal APs. Numbers indicate amino acid positions. B, SWD1 and swd1 AP deletions were episomally expressed in an swd1Δ strain. Whole-cell lysates from the indicated strains were immunoblotted using H3K4 mono- (me1), di- (me2), and trimethyl (me3) antibodies. Histone H3 was used as a loading control. 3XMYC-Set1, expressed from its endogenous chromosomal locus, was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole-cell lysates prepared from the indicated strains. 3XMYC-Set1 was detected by immunoblotting with an α-MYC antibody. Whole-cell lysates generated from strains expressing HA-tagged Swd1 and Swd1 acidic patch mutants were immunoblotted with a rabbit α-HA antibody. Immunoblots of glucose-6-phoshate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) were used for a loading control.

In addition, Swd1 and Set1 levels were analyzed in each of these strains by immunoblotting whole-cell lysates and by immunoprecipitation, respectively. Although full-length Swd1 was able to rescue Set1 protein levels, the Swd1 acidic patch mutants that were not able to restore H3K4 methylation were also not able to restore Set1 protein levels (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 3, 4, and 6). In contrast, expression of the Swd1 mutant (Swd1ΔAP4) that could partially restore H3K4 methylation was able to restore Set1 protein levels to near wild-type levels (Fig. 3B, lane 5). To determine whether the Swd1 mutants were expressed, whole-cell lysate was probed with an antibody directed against the HA tag. All of the mutants were equivalently expressed, suggesting that the observed loss of H3K4 methylation and decreased Set1 expression were not due to uneven expression of the Swd1 constructs but rather to the absence of the acidic patches (Fig. 3B).

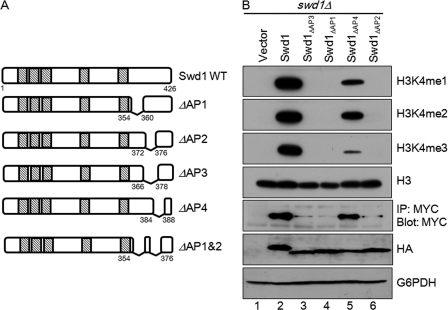

Basic Patch in nSET Domain of Set1 Is Necessary for Histone Methylation and Set1 Protein Expression

Set1 contains four annotated domains: an RNA recognition motif domain, the nSET domain, the catalytic SET domain, and the post-SET domain (Fig. 4A). It is known that the RNA recognition motif domain found at the N terminus of Set1 is important for H3K4 trimethylation and that deletion of this domain does not have an appreciable effect on Set1 protein levels (23, 33). Although the SET domain is known to be crucial for the catalytic function of Set1, the function(s) of the nSET and post-SET domains is unclear. Recently, work on human SET1A and SET1B methyltransferases has suggested that the nSET domain interacts with the Set1 complex components (8). However, the mechanism mediating these interactions is not understood. If the nSET, SET, or post-SET1 domain were necessary for interaction with Swd1, deletion of the crucial domain would result in a phenotype similar to what is observed in an swd1Δ strain. To determine whether this is the case, wild-type 3XMYC-tagged Set1 expressed ectopically under the control of its endogenous promoter and mutants that were lacking either the nSET, SET, or post-SET domain were expressed in a set1Δ strain. In addition, empty vector and wild-type Set1 were expressed in this strain as negative and positive controls, respectively. Whole-cell lysates from each strain were analyzed by immunoprecipitation for Set1 protein levels and by immunoblotting for H3K4 methylation (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, expression of Set1 lacking the SET and post-SET domains was detected, whereas expression of Set1 lacking the nSET domain was barely detected (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–5). Expression of wild-type Set1 restored Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation in the set1Δ strain, whereas expression of empty vector did not (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2). Expression of Set1 mutants lacking the nSET, SET, or post-SET domain did not restore H3K4 methylation (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–5). Analysis of H3 levels from these whole-cell lysates showed that equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Basic patch in nSET domain of Set1 is needed for H3K4 methylation and proper Set1 protein levels. A, schematic of Set1 indicating the positions of the RNA recognition motif (RRM), nSET, SET, and post-SET (Post) domains as well as the position of the nSET domain basic patch (KRKK). Numbers indicate amino acid positions. B, 3XMYC-Set1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole-cell lysates prepared from set1Δ strains expressing the indicated constructs. Set1 protein levels were detected by immunoblotting with an α-MYC antibody. C, 3XMYC-Set1 and 3XMYC-Set1ΔKRKK were immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates prepared from the indicated strains. Set1 protein levels were detected by immunoblotting using an α-MYC antibody. D, transcript levels of SET1 and the indicated set1 deletion mutants under the control of the endogenous promoter were examined using quantitative real time PCR. Actin expression was used as an internal control. The error bars shown here represent S.D. from three biological samples with three technical repeats each. E, 3XMYC-Set1 and 3XMYC-Set1ΔHRRR were immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates prepared from the indicated strains. Set1 protein levels were detected by immunoblotting using an α-MYC antibody. In B, C and E, whole-cell lysates generated from the indicated strains were immunoblotted with H3K4 mono- (me1), di- (me2), and trimethyl (me3) antibodies. Histone H3 was used for a loading control.

Because Set1 lacking the nSET domain had decreased levels of Set1 and no H3K4 methylation, similar to the swd1Δ and Swd1 acidic patch deletion strains, the sequence of the nSET domain was analyzed to further narrow down a region within this domain that would be important for Set1 protein expression and H3K4 methylation. Interestingly, the C-terminal end of the nSET domain contains a patch of basic amino acid residues (Fig. 4A). Because previous results show that an acidic-basic patch interaction is important for H3K79 methylation in vivo (27), we engineered a Set1 mutant lacking this basic patch and expressed it in a set1Δ strain. Although wild-type SET1 was able to rescue Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation in a set1Δ strain, the Set1ΔKRKK mutant, which had a significant decrease in protein amount, failed to rescue H3K4 methylation (Fig. 4C, lane 3). This observation is consistent with the results in Fig. 4B showing that deletion of nSET domain of Set1 drastically decreased the Set1 protein level and disrupted H3K4 methylation. An immunoblot for H3 showed equal loading of protein (Fig. 4C).

To determine whether our Set1 mutants were equally expressed, quantitative real time PCR was used to determine Set1 transcript level. The nSET domain, SET domain, post-SET domain, and basic patch mutants (Set1ΔKRKK) were all expressed at a level similar to that of wild-type Set1 (Fig. 4D). These data confirm that the nSET domain and basic patch deletion were transcribed and that the observed loss of H3K4 methylation was due to loss of Set1 protein levels. Furthermore, the loss of Set1 protein and H3K4 methylation seemed to be specific to the KRKK basic patch sequence because removal of a second basic patch within the nSET domain spanning amino acids 854–857 (Set1ΔHRRR) did not affect Set1 protein levels or H3K4 methylation (Fig. 4E, lane 3). Altogether these results suggest that Set1 and Swd1 are likely interacting with each other through a basic and acidic patch interaction.

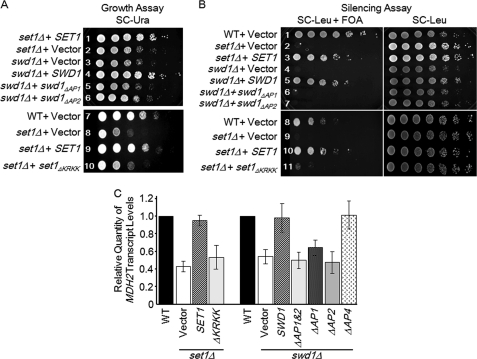

Deletion of Acidic and Basic Patches in Swd1 and Set1, Respectively, Result in Loss of Silencing, Slow Growth, and Defects in Gene Expression

Deletion of SET1 is known to result in defects in telomere, rDNA, and mating-type locus silencing as well as slow growth in certain strains (23, 24, 34). Because deletion of certain acidic patches in the C-terminal tail of Swd1 as well as deletion of a basic patch in the nSET domain of Set1 resulted in a loss of H3K4 methylation, we wanted to determine whether these deletion mutants had defects in cell growth, telomere silencing, and gene expression similar to when SET1 is deleted (23–25, 35, 36). The swd1Δ strains expressing empty vector, swd1ΔAP1, or swd1ΔAP2 used in Fig. 3 exhibited a slow growth phenotype, whereas the swd1Δ strain expressing wild-type Swd1 exhibited normal growth similar to that of the control strain (Fig. 5A, rows 1–6). In a similar manner, set1Δ strains expressing either empty vector or the set1ΔKRKK mutant exhibited slow growth, whereas a wild-type strain or a set1Δ strain expressing wild-type SET1 exhibited normal growth (Fig. 5A, rows 7–10).

FIGURE 5.

Acidic and basic patches in Swd1 and Set1 are needed for proper cell growth, telomere silencing, and gene expression. A, growth assays. The indicated yeast strains were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted on SC-Ura medium. Plates were photographed after 36 h of incubation at 30 °C. B, silencing assay. The indicated yeast strains were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted on SC-Leu + FOA or SC-Leu medium. The growth control plates (SC-Leu plates) were photographed after 24 h of incubation at 30 °C, and cells on SC-Leu + FOA plates were photographed after 60 h of incubation at 30 °C. Loss of telomere silencing was indicated by reduced or no growth on FOA-containing plates. C, transcript levels of MDH2 were examined using quantitative real time PCR in the indicated strains. Actin expression was used as an internal control. MDH2 transcript levels in Set1 and Swd1 mutant strains were compared with transcript levels in a wild-type strain. The error bars shown here represent S.D. from three biological samples with three technical repeats each.

In a complementary fashion, wild-type, set1Δ, and swd1Δ strains in which the URA3 gene was located at a subtelomeric locus were used to test whether or not the Set1 and Swd1 basic and acidic patch mutants exhibited loss of telomere silencing. Wild-type, swd1Δ, and set1Δ strains expressing empty vector or the previously mentioned Set1 and Swd1 mutants were plated on either SC-Leu or SC-Leu medium containing 5-FOA. The swd1Δ strains expressing empty vector or either swd1ΔAP1 or swd1ΔAP2 were found to be sensitive to 5-FOA, suggesting a loss of telomere silencing (Fig. 5B, rows 6 and 7). As controls, a wild-type strain expressing empty vector and a set1Δ strain expressing wild-type SET1 were both resistant to 5-FOA, and a set1Δ strain expressing empty vector was sensitive to 5-FOA (Fig. 5B, rows 1–3). Similarly, set1Δ strains expressing empty vector, wild-type SET1, or set1ΔKRKK constructs were plated on SC-Leu or SC-Leu containing 5-FOA. Although a wild-type strain or the set1Δ strain expressing wild-type Set1 were resistant to 5-FOA, the set1Δ strains expressing empty vector or the set1ΔKRKK construct were sensitive to 5-FOA, indicating a loss of telomere silencing (Fig. 5B, rows 8–11). All strains were also spotted on SC-Leu plates and showed that near equal amounts of cells were spotted in each case, suggesting that the loss of telomere silencing was specific (Fig. 5B).

Our laboratory has identified several genes, including the gene MDH2 (malate dehydrogenase), for which proper gene expression depends on H3K4 methylation (25, 30). To determine whether the Swd1 acidic patch mutant and Set1 basic patch mutant strains that showed a loss of methylation were defective in gene expression, MDH2 expression was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR in a wild-type strain; set1Δ strains expressing empty vector, wild-type SET1, and set1ΔKRKK; and swd1Δ strains expressing empty vector, wild-type SWD1, and swd1 mutants that lacked C-terminal tail acidic patches (Fig. 5C). Our analysis showed that the expression of empty vector or of the set1ΔKRKK construct in the set1Δ strain resulted in 2.3- and 1.9-fold decreases in MDH2 expression relative to wild type, respectively (Fig. 5C and supplemental Table S4). In contrast, expression of wild-type SET1 in the set1Δ strain restored MDH2 transcript to near wild-type levels (Fig. 5C). Likewise, expression of empty vector or of swd1ΔAP1, swd1ΔAP2, and swd1ΔAP1&2 in an swd1Δ strain resulted in 1.9-, 1.6-, 2.1-, and 2.0-fold decreases in MDH2 expression compared with a wild-type strain, respectively (Fig. 5C and supplemental Table S4). Expression of wild-type SWD1 or swd1ΔAP4 in an swd1Δ strain restored the MDH2 transcript to near wild-type levels, which was expected because they both were able to restore Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation (Fig. 5C). Altogether, our results show that Swd1 lacking its acidic patches or Set1 lacking the basic patch in the nSET domain phenocopies swd1 and set1 deletion strains, respectively, indicating that they are functionally important in vivo.

Acidic Patches in C-terminal Tail of Swd1 Are Important for Interaction with Set1 but Not with Swd3

Because the Swd1 acidic patch deletions and the Set1 basic patch deletion have the same biochemical and cellular phenotype, we hypothesized that the acidic patches in the C-terminal tail of Swd1 are important for interaction with Set1. However, given that expression of these Swd1 acidic patch mutants in yeast leads to vastly lower levels of Set1, co-immunoprecipitation experiments in this system to examine potential interactions between full-length Set1 and Swd1 would not be possible. To resolve this issue, 3XMYC-tagged Set1 was co-expressed with wild-type HA-tagged Swd1 or with HA-tagged Swd1 acidic patch mutants using the baculovirus protein expression system and Sf9 cells (see Fig. 6A). All proteins were expressed and located in the nuclear fraction of Sf9 cells (data not shown). Co-immunoprecipitation analysis was performed to determine whether acidic patches in Swd1 were necessary for interaction with Set1.

FIGURE 6.

Acidic patches in C terminus of Swd1 are important for binding to Set1 but not Swd3. A, co-immunoprecipitation assays were used to determine whether Swd1 and Swd1 acidic patch mutants could interact with Set1. 3XMYC-Set1, Swd1-HA, and Swd1-HA acidic patch mutants were either expressed individually or co-expressed in Sf9 cells. 3XMYC-Set1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using an α-MYC antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the presence of HA-tagged Swd1, swd1ΔAP1, swd1ΔAP2, or swd1ΔAP1&2 by immunoblotting with a rabbit α-HA antibody. Immunoblots of whole-cell lysates were performed with α-MYC and α-HA.11 antibodies to determine protein loading. B, co-immunoprecipitation assays were used to determine whether Swd1 and Swd1 acidic patch mutants could interact with Swd3. FLAG-Swd3, Swd1-HA, and Swd1-HA acidic patch mutants were either expressed individually or co-expressed in Sf9 cells. Extracts were prepared, and Swd3 was immunoprecipitated using α-FLAG M2 resin. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the presence of HA-tagged Swd1, swd1ΔAP1, swd1ΔAP2, or swd1ΔAP1&2 by immunoblotting with a rabbit α-HA antibody. Immunoblots of whole-cell lysates were performed with rabbit α-FLAG and α-HA.11 antibodies to determine protein loading.

Set1 was immunoprecipitated with an α-MYC antibody, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed using α-HA immunoblotting to detect the presence of Swd1. As controls for nonspecific interactions between Set1 or Swd1 and Sf9 cell proteins, empty vector, Set1, Swd1, and the Swd1 mutants were expressed individually (Fig. 6A, lanes 1–6). Importantly, Swd1 associated with immunoprecipitated wild-type Set1 (Fig. 6A, lane 7). However, when Set1 was co-expressed with an Swd1 mutant lacking acidic patch 1 (Swd1ΔAP1) or acidic patch 2 (Swd1ΔAP2), Set1 and Swd1 interactions were disrupted and nearly abolished (Fig. 6A, lanes 8 and 9). When an Swd1 mutant lacking both acidic patches 1 and 2 (Swd1ΔAP1&2) was co-expressed with Set1, Set1 was unable to interact with Swd1ΔAP1&2 (Figs. 3A and 6A, lane 10).

To make sure that deletion of the acidic patches of Swd1 was not disrupting the overall structure of Swd1 and therefore disrupting the ability of Set1 to bind, we determined whether Swd1 acidic patch mutants could still bind to Swd3, a known interacting partner. To determine this, HA-tagged Swd1 or Swd1 acidic patch mutants were co-expressed with FLAG-tagged Swd3 and analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6B). As expected, immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged Swd3 from cells co-expressing Swd1 was able to pull down HA-tagged Swd1 (Fig. 6B, lane 8). Importantly, all of the Swd1 acidic patch mutants were able to co-immunoprecipitate with Swd3 (Fig. 6B, lanes 9–11). Nuclear lysates were blotted for expression of Swd1 and Swd3; near equivalent loading of protein was seen (Fig. 6B). This suggests that the overall structure of Swd1 is not impaired by deletion of the acidic patches but that binding between Swd1 and Swd3 occurs in a region distinct from where binding between Swd1 and Set1 occurs.

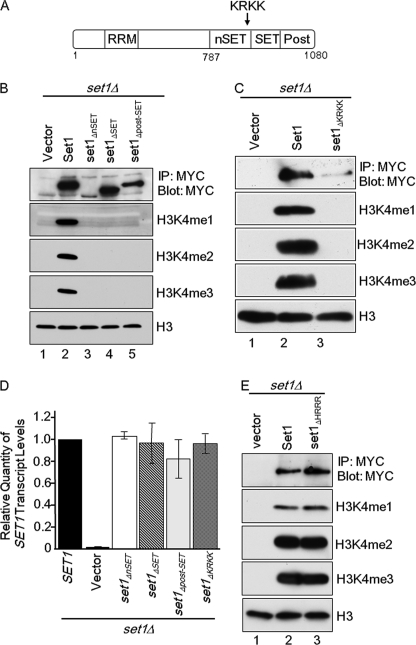

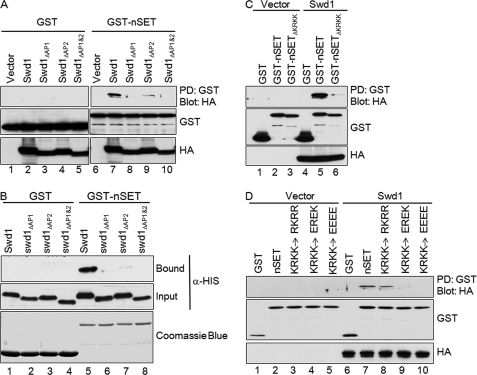

Basic Patch in nSET Domain of Set1 Is Important for Interaction with Swd1

Because we have established that the acidic patches in the C-terminal tail of Swd1 are important for its interaction with Set1 but not Swd3, we reasoned that the basic patch (KRKK) found in the nSET domain of Set1 would in a complementary fashion be important for interaction with Swd1. To test this, GST or a GST-nSET domain fusion protein was bacterially expressed and purified using glutathione-agarose. HA-tagged wild-type Swd1 and HA-tagged Swd1 acidic patch mutants were expressed using the baculovirus expression system, and extracts were incubated with GST or GST-nSET domain bound to glutathione-agarose. Swd1 and the Swd1 acidic patch mutants were not able to bind to GST itself (Fig. 7A, lanes 2–5). Although wild-type Swd1 was able to bind to the nSET domain, deletion of AP2 strongly reduced binding, and deletion of AP1 or of AP1 and AP2 together almost completely eliminated binding to the nSET domain of Set1 (Fig. 7A, lanes 7–10). Immunoblots of whole-cell lysate for GST-nSET or HA-tagged Swd1 constructs showed that equivalent amounts of protein were loaded in every lane (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Charge-based interaction mediates association between Swd1 and nSET domain of Set1 in vitro. A and B, GST fusion binding assays were used to determine binding between Swd1 and the nSET domain of Set1. GST-nSET was used to pull down (PD) the indicated HA-tagged Swd1 and Swd1 mutants from Sf9 extracts (A) or to pull down the indicated His-tagged Swd1 and Swd1 mutants from bacterial extracts (B). C, GST fusion binding assays were used to determine binding between Swd1 and the nSET domain of Set1. GST-nSET or GST-nSETΔKRKK was used to pull down (PD) HA-tagged Swd1. D, GST-nSET constructs were engineered in which the basic patch (KRKK) was mutated to conserve the charge (RKRR) or to convert to negatively charged residues (EREK or EEEE). GST fusion binding assays were used to determine binding between Swd1-HA and wild-type nSET domain and nSET domains with conserved charge or opposite charge. In all panels, GST was used as a control for nonspecific binding. Input and bound fractions of Swd1-HA were detected by immunoblotting using an α-HA.11 antibody. Input and bound fraction of His-Swd1 were detected by immunoblotting using an α-His antibody. Input fractions of GST, GST-nSET, or GST-nSET mutants were detected by immunoblotting using an α-GST antibody.

To rule out the possibility that the interaction between Set1 and Swd1 is bridged by another protein expressed from Sf9 cells, bacterially expressed Swd1 and Swd1 acidic patch mutants were used in the in vitro binding assay (Fig. 7B). Consistent with Swd1 proteins expressed in insect cells, bacterial extracts containing wild-type Swd1 was capable of interacting with the nSET domain of Set1 (Fig. 7B, lane 5). However, the interaction between Swd1 and the nSET domain of Set1 was nearly abolished when AP1 or AP2 of Swd1 was deleted (Fig. 7B, lanes 6 and 7), whereas the combinational deletion of AP1 and AP2 completely abolished the binding between Set1 and Swd1 (Fig. 7B, lane 8). Altogether, these results strongly suggest that Swd1 can directly associate with Set1 through its acidic patches in vitro.

To determine whether the basic patch within the nSET domain of Set1 was important for binding of Set1 and Swd1, a GST-nSET construct in which the basic patch was deleted was used in a GST pulldown assay. Although Swd1 was able to bind to the wild-type nSET domain, binding of Swd1 to the nSET1ΔKRKK domain was significantly reduced (Fig. 7C, lanes 5 and 6). For loading controls, whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with α-GST and α-HA antibodies for GST-nSET and HA-Swd1, respectively (Fig. 7C).

To test whether or not the observed interaction between Swd1 and the nSET domain of Set1 was mediated through an acidic-basic patch interaction, the basic patch in the GST-nSET domain was mutated either to conserve the basic residues (RKRR) or to replace the basic residues with acidic residues (EREK and EEEE). These constructs were bound to glutathione-agarose and incubated with extracts expressing either empty vector or Swd1 as described previously. GST pulldown assays and immunoblotting with α-HA antibodies were used to determine whether Swd1 could bind to the mutant nSET domains. No signal was detected in the lanes in which extract expressing empty vector was incubated with GST or with the GST-nSET constructs (Fig. 7D, lanes 1–5). As expected, Swd1 was able to bind to the wild-type nSET domain but not to GST alone (Fig. 7D, lanes 6 and 7). Importantly, Swd1 was also able to bind to the nSET domain in which the KRKK basic patch was mutated to an RKRR basic patch (Fig. 7D, lane 8). However, binding of Swd1 to the nSET domain was abolished when acidic amino acids (Glu) were introduced into the KRKK basic patch (Fig. 7D, lanes 9 and 10). GST and HA immunoblots were used to show equivalent loading of GST, GST-nSET domain, and Swd1 (Fig. 7D).

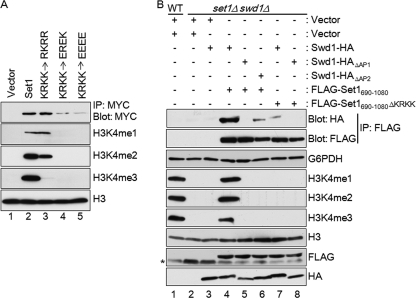

Charge-based Interaction Is Important for Association between Set1 and Swd1 and H3K4 Methylation in Vivo

Because conversion of the nSET domain basic patch to an acidic patch disrupted in vitro binding of Swd1 to the nSET domain, we wanted to determine whether expression of Set1 with these mutations would result in loss of methylation and Set1 protein level in vivo. Therefore, full-length 3XMYC-tagged Set1 ectopically expressed from its own promoter was mutated so that the nSET domain contained either a conserved basic patch (RKRR) or a basic patch containing acidic residues (EREK or EEEE). These constructs were expressed in a set1Δ strain. Whole-cell lysates from these strains were analyzed for H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation. In addition, Set1 protein levels were determined by immunoprecipitation. As expected, expression of wild-type Set1 resulted in restoration of H3K4 methylation as well as Set1 protein in a set1Δ strain (Fig. 8A, lane 2). Importantly, expression of a Set1 mutant in which the basic patch of the nSET domain was mutated to conserve the charge (KRKK to RKRR) resulted in restoration of wild-type levels of Set1 protein (Fig. 8A, lane 3). However, H3K4 monomethylation was restored to wild-type levels when this mutant was expressed, dimethylation was slightly decreased, and trimethylation was nearly abolished, suggesting that the proper basic patch sequence is also important for proper histone H3K4 di- and trimethylation (Fig. 8A, lane 3). In contrast, expression of either mutant in which the nSET domain basic patch was mutated to an acidic patch (KRKK to EREK or EEEE) resulted in decreased levels of Set1 protein (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 and 5). In addition, these mutants were not able to restore detectable levels of H3K4 methylation in the set1Δ strain (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 and 5). The decrease in Set1 levels and loss of H3K4 methylation when the nSET domain basic patch amino acids were changed to acidic amino acids were similar to what was observed in Swd1 acidic patch mutants (Fig. 3B, lanes 3, 4, and 6). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Swd1 interacts with the nSET domain of Set1 mediated by an acidic-basic patch interaction and that this interaction is important to maintain proper Set1 protein levels and H3K4 methylation.

FIGURE 8.

Charge-based interaction is important for association between Swd1 and Set1 and maintaining H3K4 methylation in vivo. A, to determine whether reversing the charge of the nSET domain basic patch affects histone methylation and Set1 protein levels, wild-type 3XMYC-Set1 or the indicated Set1 mutants were expressed in a set1Δ strain. 3XMYC-Set1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole-cell lysates and detected by immunoblotting using an α-MYC antibody. Immunoblots of whole-cell lysates using H3K4 mono- (me1), di- (me2), and trimethyl (me3) antibodies show the H3K4 methylation status from yeast strains expressing the indicated Set1 constructs. An immunoblot probed with an α-H3 antibody was used to determine protein loading. B, co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed to determine whether Swd1 and Swd1 acidic patch mutants could interact with Set1. FLAG-Set1(690–1080), FLAG-Set1 basic patch mutant (FLAG-Set1(690–1080) ΔKRKK), Swd1-HA, and Swd1-HA acidic patch mutants were either expressed individually or co-expressed in yeast. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the presence of HA-tagged Swd1, swd1ΔAP1, or swd1ΔAP2 by immunoblotting with a rabbit α-HA antibody. Immunoblots of whole-cell lysates using H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethyl antibodies show the H3K4 methylation status in yeast. Immunoblots were probed with rabbit α-FLAG, rabbit α-HA, α-H3, or α-glucose-6-phoshate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) antibody to monitor protein loading. The plus (+) and minus (−) symbols represent the expressed construct.

Our data indicate that the interaction between Set1 and Swd1 is critical for maintaining the cellular protein levels of Set1 and subsequent Set1-mediated H3K4 methylation. The disruption of this charge-based interaction by deleting the binding region in Set1 (the basic patch) or the binding regions in Swd1 (the acidic patches) resulted in a significant reduction of Set1 protein levels in vivo (Figs. 3B and 4C). However, an alternative interpretation would be that deleting these basic or acidic patches in Set1 or Swd1, respectively, causes incorrect folding of Set1, resulting in degradation of Set1 and subsequent loss of H3K4 methylation. Because the expression of the Set1 KRKK deletion mutant or the Swd1 acidic patch mutants in yeast resulted in vastly lower levels of Set1 protein, it would be very difficult to directly examine the interaction between Set1 and Swd1 in vivo. To solve this problem, we identified a Set1 construct that is stably expressed in an swd1Δ strain. Interestingly, this Set1 construct lacks the first 689 amino acids, suggesting that a degradation sequence is located in the N terminus of Set1. This Set1 construct (Set1(690–1080)), which includes the nSET domain, SET domain, and post-SET domain of Set1, was readily expressed and was able to rescue H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation to near wild-type levels (Fig. 8B, lanes 1 and 4). In contrast to full-length Set1, Set1(690–1080) was stably expressed when the KRKK region was deleted or when expressed in an swd1Δ strain (Fig. 8B, lanes 5–8, FLAG panels). To determine whether the acidic patches of Swd1 are important for Set1 binding in vivo, the wild-type Swd1 or Swd1 acidic patch mutants were co-expressed with either Set1(690–1080) or Set1(690–1080) ΔKRKK mutants in yeast, and co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed. As expected, wild-type Swd1 can interact with Set1(690–1080) (Fig. 8B, lane 4, top two panels). In contrast, deletion of AP1 of Swd1 completely abolished the binding with Set1(690–1080), whereas deletion of AP2 of Swd1 significantly reduced its capacity to bind Set1(690–1080) (Fig. 8B, lanes 5 and 6). Deletion of the basic patch KRKK of Set1 also dramatically decreased binding with wild-type Swd1 (Fig. 8B, lane 7), whereas deletion of both AP1 of Swd1 and KRKK of Set1 abolished the Set1-Swd1 interaction (Fig. 8B, lane 8). Altogether, these data combined with our in vitro results indicate that Set1 can directly associate with Swd1 through the basic-acidic patch interaction. Consistent with previous results shown in Figs. 3B and 4B, all constructs that disrupted Set1 and Swd1 interactions resulted in H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation defects (Fig. 8B, lanes 5–8). Therefore, this charge-based mode of interaction is critical for the stability of Set1 and for histone methylation.

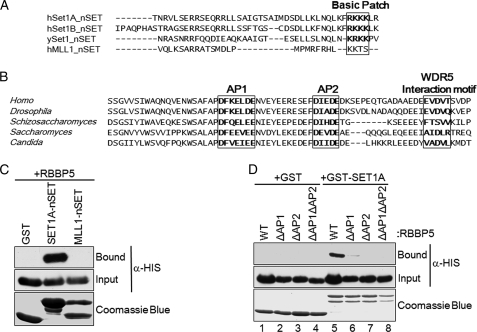

Human SET1A, but Not MLL1, Interacts with Human RBBP5 in Vitro

A previous study has shown that the nSET domains of SET1A and SET1B, the human homologs of Set1, are important for interacting with other members of the human SET1 H3K4 methyltransferase complex (8), although the associating partner was not identified. However, based on our data showing that Swd1 directly interacts with the nSET domain of Set1 in yeast, we hypothesized that the human homolog of Swd1, RBBP5, is the target protein that binds to the nSET domain of human SET1A and SET1B. Interestingly, by sequence alignment, the C-terminal end of the nSET domain of SET1A and SET1B has a basic patch of amino acids (RKKK) that is located at a position similar to that of the basic patch (KRKK) in the nSET domain of yeast Set1 (Fig. 9A). However, a conserved basic patch in the same region does not exist in another human Set1-like complex, MLL1 (Fig. 9A). This observation suggests the possibility that this charge-based interaction mechanism is conserved between SET1A/SET1B and RBBP5 in mammals. To determine whether this mode of interaction is conserved, in vitro GST fusion binding assays were performed using purified GST-tagged SET1A-nSET or GST-tagged MLL1-nSET incubated with bacterially expressed His-tagged RBBP5. As predicted, SET1A-nSET fragment efficiently bound to RBBP5, whereas MLL1-nSET fragment did not directly bind to RBBP5 (Fig. 9C). This result suggests that the nSET domain of SET1A is important to mediate an in vitro interaction between RBBP5 and SET1A.

FIGURE 9.

Human SET1A, but not MLL1, interacts with human RBBP5 in vitro. A, sequence alignment of the nSET domain regions of yeast Set1 compared with human orthologs SET1A, SET1B, and MLL1. The conserved basic patch region is bold and boxed. The alignment was generated by ClustalX software using the nSET domain sequences. The y represents budding yeast nSET domain sequence, and h represents human nSET domain sequences. B, sequence alignment of yeast Swd1 compared with other orthologs. The region shown represents the C-terminal region of Swd1 and RBBP5. The conserved acidic patches (AP1 or AP2) and the WDR5 interaction motif are bold and boxed. This result was generated by ClustalX software using the full-length amino acid sequences of Swd1 and RBBP5. Homo represents Homo sapiens, Drosophila represents Drosophila melanogaster, Schizosaccharomyces represents Schizosaccharomyces Pombe, Saccharomyces represents Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Candida represents Candida albicans. C, GST fusion binding assays were performed to determine whether the nSET domains of SET1A and MLL1 bind to RBBP5. GST-SET1A-nSET (amino acids 1498–1572) or GST-MLL1-nSET (amino acids 3753–3832) was used to pull down bacterially expressed His-tagged RBBP5. GST was used as a control for nonspecific binding. D, GST fusion binding assays were used to determine whether acidic patches in RBBP5 are important for its binding to the nSET domain of SET1A. GST-SET1A-nSET was used to pull down His-tagged RBBP5 and the indicated RBBP5 acidic patch mutants. GST was used as a control for nonspecific binding. The input and bound fractions of His-RBBP5 were detected by immunoblotting with an α-His antibody. The amount of GST or GST fusion protein fragments was analyzed by Coomassie Blue staining.

Because Swd1 C-terminal tail acidic patches are conserved from yeast to higher eukaryotes and RBBP5 has C-terminal acidic patches that are similar to those in Swd1 (Fig. 9B), it is very likely those acidic patches are also important for associating with the nSET domain of SET1A. To this end, the in vitro GST fusion binding assays were performed using purified GST or GST-tagged nSET domain of SET1A incubated with His-tagged wild-type RBBP5 or acidic patch mutants including deletion of acidic patch 1 (ΔAP1), deletion of acidic patch 2 (ΔAP2), and deletion of both AP1 and AP2 (ΔAP1ΔAP2). RBBP5 and RBBP5 acidic patch mutants were not able to bind to GST itself (Fig. 9D, lanes 1–4). Although wild-type RBPP5 was able to bind to the nSET domain of SET1A, deletion of AP1 or AP2 strongly reduced binding, and deletion both AP1 and AP2 together completely eliminated binding to the nSET domain of SET1A (Fig. 9D, lanes 5–8). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the charge-based interaction mechanism between Set1 and Swd1 in yeast is evolutionarily and functionally conserved between SET1A/B and RBBP5 in human. Further experiments are needed to examine whether this mode of interaction is also essential for H3K4 methylation, cell growth, and specific gene expression patterns in humans or other eukaryotes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined that small acidic patches in the C-terminal tail of Swd1 and a basic patch in the nSET domain of Set1 are necessary for interaction between these two members of the Set1 complex. This interaction is important because deletion of these key amino acids resulted in near abolishment of Set1 protein levels and a complete loss of H3K4 methylation. In addition, deletion of either the acidic patches or basic patch resulted in growth defects, loss of telomere silencing, and decreased gene expression similar to what is observed for a set1Δ phenotype or when H3K4 methylation is lost (23, 24, 34). Furthermore, we showed that the interaction between Swd1 and Set1 is mediated by a charge-based interaction that is critical for the cellular integrity of Set1 and H3K4 methylation. In addition, our data suggest that this charge-based interaction likely occurs in humans as well, demonstrating an evolutionarily conserved mode of interaction.

Previous work has shown that basic amino acids forming the N-terminal basic patch of histone H4 could interact with acidic amino acid residues in the C terminus of the H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1 (27). In addition, this charge-based interaction was important for H3K79 methylation. In a similar manner, we determined that a charge-based interaction can occur between two Set1 complex components Set1 and Swd1. Therefore, charge-based interactions appear to be crucial not only for interactions between histones and histone methyltransferases but also for interactions among the various components of histone methyltransferase complexes. Upon examination of the amino acid sequences of Set1 and other Set1 complex components, it is clear that other acidic and basic amino acid patches exist. Additional work will be needed to determine whether they play a role in the assembly of the methyltransferase complex, histone methylation, or other unknown functions. Using the Saccharomyces Genome Database PatMatch program, a program that allows you to search for similar peptide or nucleotide sequence patterns, many different types of chromatin-associated factors appear to have small protein motifs containing short stretches of basic and acidic residues. Therefore, it is likely that many of these acidic and basic patch motifs found within chromatin-associated factors could mediate key biochemical interactions that are important for their function.

Although the compositions of the yeast and human Set1 and Set1-like complexes have been known for quite some time, how the different members of these complexes contribute to H3K4 methylation is still being explored (1, 2, 6, 8, 9). Nonetheless, several studies on yeast and human H3K4 methyltransferase complexes have provided key insights into how some of these components interact (3, 8, 30, 37, 38). For example, the nSET domains of SET1A and SET1B have been shown to be important for interacting with other members of the human SET1 H3K4 methyltransferase complex (8). Although it was not shown which protein was directly associating with the nSET domain in that study, our study indicates that RBBP5 is directly binding to the nSET domain of SET1A by a charge-based interaction (Fig. 9). Additional studies will be needed to examine whether this charge-based interaction occurs in vivo and whether this interaction is important for maintaining H3K4 methylation and proper gene expression in mammals. In addition, given that overexpression of the nSET domain of human SET1A results in decreased protein levels of endogenous SET1A and SET1B (8), it is presumed that this fragment can interact with RBBP5 and titrate away RBBP5 from endogenous SET1A or SET1B, resulting in the degradation of endogenous SET1A/B. This suggests that association of SET1A or SET1B with RBBP5 is necessary for protein stability (8) and is reminiscent of what was seen when the acidic and basic patches of Swd1 and Set1, respectively, were removed.

Previous studies have shown that deletion of Set1 complex subunits both in yeast and in human, such as Swd1(RBBP5) and Swd3 (WDR5), results in the loss of Set1 protein and the disruption of the histone methyltransferase complex (3, 5). However, how Swd1 and Swd3 influence Set1 protein stability and maintain the complex stability was not understood until this study. However, additional studies will be needed to fully understand how the Set1 complex is assembled. For example, although our study identified a charge-based mode of interaction between Set1 and Swd1, deletion of either the acidic patches of Swd1 or the basic patch of Set1 did not completely eliminate Set1 protein, suggesting that some other components of Set1 complex or other regions of Set1 may also be involved in maintaining Set1 protein stability. In addition, our result has shown that deletion of Spp1 and Shg1 moderately decreased Set1 protein levels (Fig. 1A). Further work is needed to determine whether these two subunits participate in modulating Set1 protein level or what other regions of Set1 are also needed for maintaining Set1 protein. Finally, it is still unclear how Set1 is degraded, although it is likely degraded by the proteasome. Interestingly, our data would suggest that the signal for protein degradation in Set1 may exist at its N terminus because an N-terminal Set1 truncation mutant was expressed in an swd1Δ strain, whereas full-length Set1 was not. Defining this signal will further shed light on how the 26 S proteasome recognizes Set1 for degradation and how the integrity of Set1 complex is regulated.

Based on our results and studies on the human H3K4 methyltransferase complex components, it appears that conserved components of the SET1 and MLL complexes are likely to assemble differently. Although our data suggest that Swd1 can interact with Set1 by itself, work done with MLL1 demonstrates that WDR5 requires RBBP5 to stabilize MLL1 complex association (7). Interestingly, knockdown of RBBP5 does not seem to affect MLL1 protein levels (5, 7). In contrast, human SET1 components are needed for the stability of SET1A and SET1B protein levels (8, 39, 40). As mentioned above, SET1A and SET1B methyltransferases contain a conserved basic patch. However, by sequence alignment, we were unable to identify a similar basic patch in the nSET domain of MLL1. In addition, our data would also suggest that RBBP5 interacts specifically with the nSET domain of SET1A but not MLL1 (Fig. 9C). Taken together, these data suggest that whereas the SET1A/B and MLL H3K4 methyltransferase complexes are composed of similar subunits and target the same residue for methylation they are likely assembled in different ways.

Given that human SET1A/B and yeast Set1, but not MLL1, require various complex components for protein stability, it is possible that association and disassociation of Set1 complex members could be used as a mechanism to control H3K4 methylation at specific gene loci. Furthermore, if these H3K4 methyltransferases are found to assemble differently, there may be ways to distinctly inhibit the SET1A/B and MLL1–4 complexes. This is important because both MLL1 and SET1A play a role in regulating gene expressions of potential oncogenes (29, 41–43). Overall, additional biochemical and structure studies are needed so that small molecule inhibitors specific to the various H3K4 methyltransferase complexes can be generated and used to help treat human diseases.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM74183 to (to S. D. B.).

This article contains supplemental methods and Tables S1–S4.

- H3K4

- histone H3 lysine 4

- MLL

- mixed lineage leukemia

- 5-FOA

- 5-fluoroorotic acid

- 3XMYC

- triple MYC

- H3K79

- histone H3 lysine 79

- AP

- acidic patch.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roguev A., Schaft D., Shevchenko A., Pijnappel W. W., Wilm M., Aasland R., Stewart A. F. (2001) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4. EMBO J. 20, 7137–7148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller T., Krogan N. J., Dover J., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Johnston M., Greenblatt J. F., Shilatifard A. (2001) COMPASS: a complex of proteins associated with a trithorax-related SET domain protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12902–12907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dehé P. M., Dichtl B., Schaft D., Roguev A., Pamblanco M., Lebrun R., Rodríguez-Gil A., Mkandawire M., Landsberg K., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Rosaleny L. E., Tordera V., Chávez S., Stewart A. F., Géli V. (2006) Protein interactions within the Set1 complex and their roles in the regulation of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35404–35412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mueller J. E., Canze M., Bryk M. (2006) The requirements for COMPASS and Paf1 in transcriptional silencing and methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 173, 557–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steward M. M., Lee J. S., O'Donovan A., Wyatt M., Bernstein B. E., Shilatifard A. (2006) Molecular regulation of H3K4 trimethylation by ASH2L, a shared subunit of MLL complexes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 852–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagy P. L., Griesenbeck J., Kornberg R. D., Cleary M. L. (2002) A trithorax-group complex purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for methylation of histone H3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 90–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dou Y., Milne T. A., Ruthenburg A. J., Lee S., Lee J. W., Verdine G. L., Allis C. D., Roeder R. G. (2006) Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 713–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee J. H., Tate C. M., You J. S., Skalnik D. G. (2007) Identification and characterization of the human Set1B histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13419–13428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yokoyama A., Wang Z., Wysocka J., Sanyal M., Aufiero D. J., Kitabayashi I., Herr W., Cleary M. L. (2004) Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5639–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes C. M., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Milne T. A., Copeland T. D., Levine S. S., Lee J. C., Hayes D. N., Shanmugam K. S., Bhattacharjee A., Biondi C. A., Kay G. F., Hayward N. K., Hess J. L., Meyerson M. (2004) Menin associates with a trithorax family histone methyltransferase complex and with the hoxc8 locus. Mol. Cell 13, 587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel A., Vought V. E., Dharmarajan V., Cosgrove M. S. (2008) A conserved arginine-containing motif crucial for the assembly and enzymatic activity of the mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 core complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32162–32175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Southall S. M., Wong P. S., Odho Z., Roe S. M., Wilson J. R. (2009) Structural basis for the requirement of additional factors for MLL1 SET domain activity and recognition of epigenetic marks. Mol. Cell 33, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ruthenburg A. J., Wang W., Graybosch D. M., Li H., Allis C. D., Patel D. J., Verdine G. L. (2006) Histone H3 recognition and presentation by the WDR5 module of the MLL1 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 704–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wysocka J., Swigut T., Milne T. A., Dou Y., Zhang X., Burlingame A. L., Roeder R. G., Brivanlou A. H., Allis C. D. (2005) WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell 121, 859–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avdic V., Zhang P., Lanouette S., Groulx A., Tremblay V., Brunzelle J., Couture J. F. (2011) Structural and biochemical insights into MLL1 core complex assembly. Structure 19, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schuetz A., Allali-Hassani A., Martín F., Loppnau P., Vedadi M., Bochkarev A., Plotnikov A. N., Arrowsmith C. H., Min J. (2006) Structural basis for molecular recognition and presentation of histone H3 by WDR5. EMBO J. 25, 4245–4252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Couture J. F., Collazo E., Trievel R. C. (2006) Molecular recognition of histone H3 by the WD40 protein WDR5. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 698–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han Z., Guo L., Wang H., Shen Y., Deng X. W., Chai J. (2006) Structural basis for the specific recognition of methylated histone H3 lysine 4 by the WD-40 protein WDR5. Mol. Cell 22, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song J. J., Kingston R. E. (2008) WDR5 interacts with mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) protein via the histone H3-binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35258–35264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Odho Z., Southall S. M., Wilson J. R. (2010) Characterization of a novel WDR5-binding site that recruits RbBP5 through a conserved motif to enhance methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 by mixed lineage leukemia protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32967–32976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel A., Dharmarajan V., Vought V. E., Cosgrove M. S. (2009) On the mechanism of multiple lysine methylation by the human mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 (MLL1) core complex. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24242–24256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patel A., Vought V. E., Dharmarajan V., Cosgrove M. S. (2011) A novel non-SET domain multi-subunit methyltransferase required for sequential nucleosomal histone H3 methylation by the mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 (MLL1) core complex. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 3359–3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fingerman I. M., Wu C. L., Wilson B. D., Briggs S. D. (2005) Global loss of Set1-mediated H3 Lys4 trimethylation is associated with silencing defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28761–28765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Briggs S. D., Bryk M., Strahl B. D., Cheung W. L., Davie J. K., Dent S. Y., Winston F., Allis C. D. (2001) Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15, 3286–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mersman D. P., Du H. N., Fingerman I. M., South P. F., Briggs S. D. (2009) Polyubiquitination of the demethylase Jhd2 controls histone methylation and gene expression. Genes Dev. 23, 951–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nislow C., Ray E., Pillus L. (1997) SET1, a yeast member of the trithorax family, functions in transcriptional silencing and diverse cellular processes. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 2421–2436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fingerman I. M., Li H. C., Briggs S. D. (2007) A charge-based interaction between histone H4 and Dot1 is required for H3K79 methylation and telomere silencing: identification of a new trans-histone pathway. Genes Dev. 21, 2018–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Du H. N., Fingerman I. M., Briggs S. D. (2008) Histone H3 K36 methylation is mediated by a trans-histone methylation pathway involving an interaction between Set2 and histone H4. Genes Dev. 22, 2786–2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milne T. A., Martin M. E., Brock H. W., Slany R. K., Hess J. L. (2005) Leukemogenic MLL fusion proteins bind across a broad region of the Hox a9 locus, promoting transcription and multiple histone modifications. Cancer Res. 65, 11367–11374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. South P. F., Fingerman I. M., Mersman D. P., Du H. N., Briggs S. D. (2010) A conserved interaction between the SDI domain of Bre2 and the Dpy-30 domain of Sdc1 is required for histone methylation and gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 595–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Halbach A., Zhang H., Wengi A., Jablonska Z., Gruber I. M., Halbeisen R. E., Dehé P. M., Kemmeren P., Holstege F., Géli V., Gerber A. P., Dichtl B. (2009) Cotranslational assembly of the yeast SET1C histone methyltransferase complex. EMBO J. 28, 2959–2970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Altaf M., Utley R. T., Lacoste N., Tan S., Briggs S. D., Côté J. (2007) Interplay of chromatin modifiers on a short basic patch of histone H4 tail defines the boundary of telomeric heterochromatin. Mol. Cell 28, 1002–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schlichter A., Cairns B. R. (2005) Histone trimethylation by Set1 is coordinated by the RRM, autoinhibitory, and catalytic domains. EMBO J. 24, 1222–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bryk M., Briggs S. D., Strahl B. D., Curcio M. J., Allis C. D., Winston F. (2002) Evidence that Set1, a factor required for methylation of histone H3, regulates rDNA silencing in S. cerevisiae by a Sir2-independent mechanism. Curr. Biol. 12, 165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krogan N. J., Dover J., Khorrami S., Greenblatt J. F., Schneider J., Johnston M., Shilatifard A. (2002) COMPASS, a histone H3 (lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10753–10755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santos-Rosa H., Schneider R., Bannister A. J., Sherriff J., Bernstein B. E., Emre N. C., Schreiber S. L., Mellor J., Kouzarides T. (2002) Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419, 407–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Takahashi Y. H., Lee J. S., Swanson S. K., Saraf A., Florens L., Washburn M. P., Trievel R. C., Shilatifard A. (2009) Regulation of H3K4 trimethylation via Cps40 (Spp1) of COMPASS is monoubiquitination independent: implication for a Phe/Tyr switch by the catalytic domain of Set1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 3478–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]