Abstract

An apparatus that integrates solid-state nanopore ionic current measurement with a Scanning Probe Microscope has been developed. When a micrometer-scale scanning probe tip is near a voltage biased nanometer-scale pore (10–100 nm), the tip partially blocks the flow of ions to the pore and increases the pore access resistance. The apparatus records the current blockage caused by the probe tip and the location of the tip simultaneously. By measuring the current blockage map near a nanopore as a function of the tip position in 3D space in salt solution, we estimate the relative pore resistance increase due to the tip, ΔR/R0, as a function of the tip location, nanopore geometry, and salt concentration. The amplitude of ΔR/R0 also depends on the ratio of the pore length to its radius as Ohm’s law predicts. When the tip is very close to the pore surface, ~10 nm, our experiments show that ΔR/R0 depends on salt concentration as predicted by the Poisson and Nernst-Planck equations. Furthermore, our measurements show that ΔR/R0 goes to zero when the tip is about five times the pore diameter away from the center of the pore entrance. The results in this work not only demonstrate a way to probe the access resistance of nanopores experimentally, they also provide a way to locate the nanopore in salt solution, and open the door to future nanopore experiments for detecting single biomolecules attached to a probe tip.

Keywords: solid-state nanopore, access resistance, Scanning Probe Microscope, Current blockage

1. Introduction

A voltage-biased nanopore can electronically detect individual biopolymers in their native environment. Protein nanopores suspended in lipid bilayers are capable of characterizing single DNA and RNA molecules.1–4 Solid-state nanopores fabricated from silicon nitride, silicon dioxide, or aluminum oxide have been used to detect DNA and proteins.5–7 When a nanometer scale pore in a thin insulating membrane is immersed in an electrolyte solution and a voltage is applied across the membrane, most of the voltage drop occurs inside the pore (Figure 1a). However, there should be an appreciable amount of voltage drop occurring at the immediate vicinity of the pore entrance and exit, characterized by an access resistance, due to the electric field distribution extending beyond the physical limits of the pore (Figure. S2a). When charged particles such as biomolecules are close to the pore, the particles will be first captured by the electric field near the pore and then forced to move through the pore by the electrostatic force.8–11 The capturing process is determined by the electric field distribution near the pore which is also characterized as access resistance.8–12 For monitoring nanopore resistance change based sensing devices, access resistance is an important parameter and it becomes a dominant component to the pore resistance as a pore gets thinner, as has been demonstrated in recent monolayer thin graphene nanopore experiments.13–15

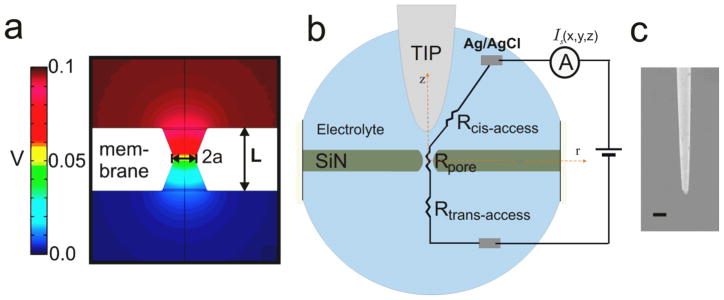

Figure 1.

(a) Simulation of electrical potential around a ~100 nm diameter pore in 0.1M KCl. The shape of the nanopore is idealized to a cylindrical hourglass shape based on recent published work.12, 37 (b) Schematic drawing of nanopore ionic current profile measurement near a nanopore with the SSN-SPM system (not to scale). The measured total pore resistance is the sum of the pore resistance and the access resistances at both sides of the pore. The SPM tip close to the nanopore increases the access resistance in the cis chamber (Rcis-access). (c) SEM image of a SPM tip used in this work. The scale bar is 5 μm.

One of the obstacles for a nanopore-based device to reach the promised potential is that the translocation speed of biomolecules has been too fast to be well resolved.3, 16, 17 Another is that the electric field distribution or the access resistance near a nanopore is not well characterized experimentally. To overcome these problems, optical tweezers18–20 as well as magnetic tweezers21 have been used to control DNA translocation through solid-state nanopores by attaching DNA molecules to micrometer size beads. Physical probes such as a focused laser beam,22 an electrolyte-filled micropipette,23, 24 and a nanotube-attached SPM tip25 have been used to study the ionic conductance profile around solid-state nanopores. Motivated to reduce the positional fluctuation compared to optically trapped beads and to detect the controlled threading of single DNA molecules attached to a probe tip, we have designed and constructed a measuring system that integrates a solid-state nanopore with a Scanning Probe Microscope (SSN-SPM) as shown in Figure 1b.

In the SSN-SPM system, the SPM tip (Figure 1b) has sub-nanometer scale position control with a piezo actuator. A SEM image of a SPM tip used in this work is shown in Figure 1c. As illustrated in Figure 1b, the SSN-SPM system measures the ionic current, Is(x, y, z), through a nanopore as a SPM tip scans near the pore while keeping the tip height (z=Htip,) as a constant. The nanopores used in this work are fabricated in freestanding silicon nitride membranes by focused ion (Ga) beam (FIB) followed by low energy ion (noble gas) beam sculpting.5, 26 The membrane divides the electrolyte solution into two sections: cis and trans chambers. Most electrolyte solutions used in the experiment contain 1M potassium chloride (KCl) with 10mM Tris at pH 8, with some solutions having lower KCl concentrations as specified. The sole electrical and fluidic connection between the two chambers is the nanopore. The ionic current through the pore is measured by a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes in the chambers. The ionic current is measured and recorded with an Axopatch 200B integrated amplifier system (Molecular Devices). The chambers are mounted on the SPM sample stage. The relative position of the stage and probe are controlled by XYZ piezos.

1.1. Nanopore Resistance and Access Resistance

The total resistance of a nanopore (R0) in salt solution includes the pore resistance (Rpore) inside the pore and the access resistance (Raccess) from the mouths of the pore to the electrodes as shown in Figure 1b. Most features of the total resistance can be modeled by assuming the pore is a radically symmetric cylinder with length L and diameter a, and that the electrode is infinitely far away. The concept of access resistance has been described by earlier publications.27, 28 Assuming that the electrolyte is a homogeneous conducting medium with resistivity ρ, the total resistance can be written as

| (1) |

The access resistance on one side of the membrane is Racess=ρ/4a which is calculated by integrating the resistance from a disk-like mouth to an infinite hemi-sphere.29 The access resistance has the same order of magnitude as the pore resistance if the pore length L is comparable to the pore radius a which is true for both protein and solid-state nanopores. According to Eq. (1) the access resistance becomes the dominant component of the pore resistance when L/a ≤ 1.57. Equation (1) considers the electrolyte as a homogeneous conducting medium. This is based on the assumption that the membrane and pore surfaces are uncharged. This assumption is good under the condition that the pore diameter is much larger than the Debye length. In this particular experiment, Eq. (1) also assumes that the distance from the tip to the pore surface is much larger than the Debye length. For a given salt concentration and pH, a charged surface considerably reduces the access resistance of a channel,30 and the Poisson and Nernst-Planck (PNP) equations are needed to describe the flux of ions through charged channels.30, 31

The access resistance on one side of the pore, Raccess=ρ/4a, is calculated assuming that there is no obstacle between the nanopore’s mouth and the electrode and is based on Ohm’s law. If we add obstacles close to the nanopore entrance, the access resistance contribution to the total resistance will increase. Using this principle, water-soluble polymers in the vicinity of the pore were used to study the access resistance contribution to the total nanopore channel resistance.9, 32 A SPM tip near a nanopore entrance is a large obstacle that can partially block the ionic current flow and can generate a current blockage signal due to an increased pore access resistance. In this work, by measuring the ionic current blockage profile Is(x, y, z), we study how the relative pore resistance changes with the SPM tip position, nanopore diameter (Dp), and salt concentration.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Data Measured by the SSN-SPM system

Figure 2 shows a simultaneously measured topography and ionic current blockage profile as a SPM tip was scanning above a nanopore surface measured with the SSN-SPM system. An ellipse shaped nanopore was used in this measurement and its transmission electron microscope (TEM) Image (Figure 2a) shows the pore had dimensions of 35 nm × 75 nm. The amplitude of the oscillating tip is damped as it moves to within 30 nm of the surface. The shear force feedback system maintains the specific engaging distance between the tip and the surface. The engagement distance was set at Htip =10 nm for Figure 2b–2d. The height feedback error in the Scanning Probe Microscope is estimated to be about ±1nm from the topography noise. The raster scanning speed of the tip was 3 μm/s over 10 μm by 10 μm surface. The topography of the nanopore (Figure 2b) shows a crater as reported previously.33 The crater has the elliptical shape as shown in Figure 2a.

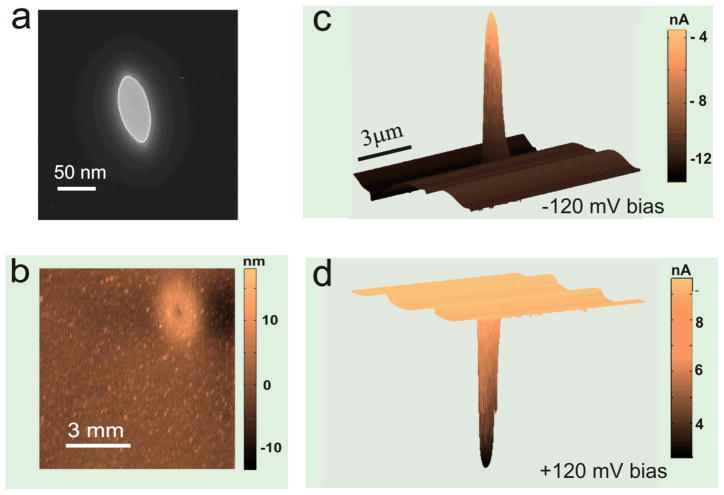

Figure 2.

(a) TEM image of an elliptical shape nanopore. The length of the major axis is 75nm and the minor axis is 35nm. (b) Topography around the same nanopore (a) measured by a SPM tip. The bulge’s major axis has the same orientation compared to the TEM image. (c) Ionic current map around the nanopore recorded at ψ= − 120mV bias in a solution of 0.1 M KCl. (d) Ionic current map measured with the same parameters of (c) except that the polarity of the bias voltage is changed to ψ=120mV. The images of (b), (c), and (d) were measured simultaneously while a SPM tip is scanning, so the x-y axis limits of (b), (c), and (d) are the same.

The nanopore ionic current profile in Figure 2c was measured at ψ = −120mV bias voltage across the Ag/AgCl electrodes in 100 mM KCl solution. In the current map, when the tip passes the pore, the ionic current amplitude is reduced from −10 nA to −4 nA. To verify that the current blockage is due to the tip interaction with the nanopore, we scanned the same area of Figure 2b with positive 120 mV bias voltage. As expected, the ionic current dropped from 8 nA to 3 nA as shown in Figure 2d. Thus, the current blockage observed in this experiment was indeed due to the tip partially blocking the ionic current flow through the nanopore. The current was measured at 2 kHz low pass filter setting on the Axopatch 200B. The advantage of this experiment compared to G. M. King’s result25 is that a micrometer scale blunt tip can occlude a large solid angle above the pore and can make a significant change to the nanopore access resistance. Furthermore, the significant change in resistance caused by a scanning micrometer scale tip can initially locate the position of the nanopore more quickly than a nanotube tip.

2.2. Nanopore Ionic Current Map for Pores of different sizes

To investigate how the SPM tip height (Htip) and its radial distance from the center of the pore affect the current flow through the pore, ionic current maps, Is(x, y, z), were measured at different height (Z=Htip) values. We first scan the area around a nanopore to know the normal vector to the surface plane, then lift the tip and scan the plane above a certain height (Htip) from the surface plane. One example of an ionic current map taken at a tip height, Htip =110 nm, is shown in Figure 3a. At lifting heights above 60 nm, the drifting of the tip in the z direction is estimated to be ~10 nm.34 At Htip =10 nm, the drifting problem is minimized since the feedback is on. The current blockage amplitude caused by the SPM tip, ΔIb, was the difference between the open pore current I0 (measured with the tip far away from the pore) and the instantaneous pore current Is. The increase in the total pore resistance due to the tip nearby can be written as

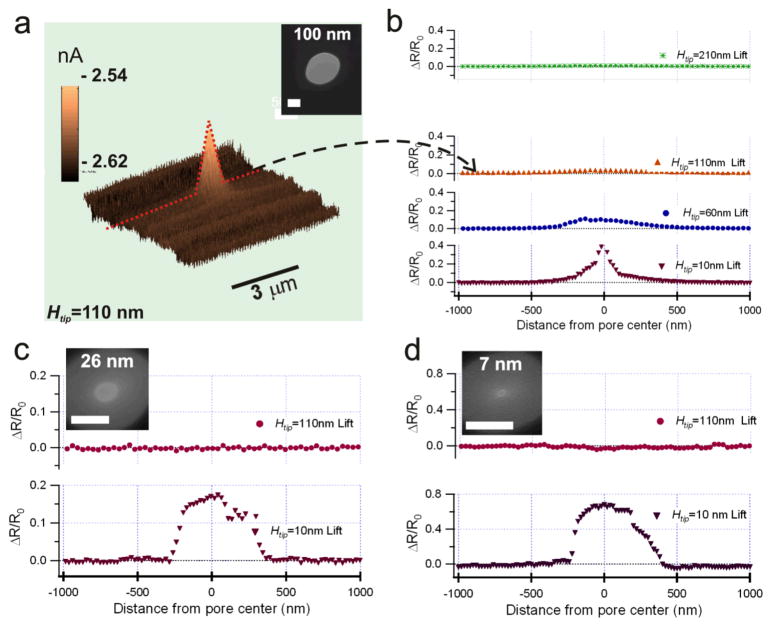

Figure 3.

(a) Nanopore ionic current map measured at the SPM tip height Htip=110 nm. A 100 nm size FIB pore was used for the measurement in 0.1 M KCl solution and Ψ =−60 mV. (b) The ratio of ΔR/R0 as a function of the distance from the 100 nm pore in (a) measured at different tip height. The ratio of ΔR/R0 measured with a 26 nm diameter pore in 1 M KCl (c) at Ψ = −100mV and with a 7 nm size pore in 1 M KCl (d) at Ψ = −150mV. The insets in (b), (c), and (d) are TEM images of the scanned pores. The scale bars are 50 nm in all the TEM images. Different voltages were used to increase the ionic current signal to noise ratio.

| (2) |

Here R0= ψ/I0 is the nanopore total resistance without a SPM tip nearby, Rs=R0+Rtip=ψ/Is is the nanopore resistance with a SPM tip nearby, ΔR =Rtip is the resistance increase caused by the tip blocking the flow of ions, and ΔIb=I0−Is. The ratio of ΔR/R0 calculated as a function of the distance from the tip to pore center and the tip lift height Htip is shown in Figure 3b for a large and long pore (2a~100 nm, L~300 nm), in Figure 3c for a pore its diameter is close to its length (2a~26 nm, L~20 nm), and in Figure 3d for a small pore (2a~7 nm, L~20 nm). The peak values of the normalized blockade current ΔIb/I0=α for data shown in Fig. 3 is listed in Table 1. The relative resistance increase of the nanopore ΔR/R0=α/(1−α) is also listed in the table. Based on the nanopore geometry and Eq. (1), the calculated ratio of the access resistance on one side of the pore Rac-cis=ρ/4a to R0, Rac-cis/R0=1/[4(L/πa +1/2)], is also given in table 1.

Table 1.

Relative current blockage, resistance change for pores measured in Fig. 3 at different lift heights

| The size of pore | 2a~100 [nm] | 2a~26 [nm] | 2a~7 [nm] |

|

| |||

| The ratio of L/a | L/a ≈ 6 | L/a ≈ 1.5 | L/a ≈ 5.7 |

|

| |||

| Rac-cis/R0 | 0.104 | 0.25 | 0.108 |

|

| |||

| Measurements | ΔIb/I0, ΔR/R0 | ΔIb/I0, ΔR/R0 | ΔIb/I0, ΔR/R0 |

|

| |||

| Htip =10 [nm] | 0.35, 0.50 | 0.15, 0.18 | 0.41, 0.69 |

| Htip =60 [nm] | 0.08, 0.10 | ||

| Htip =110 [nm] | 0.03, 0.03 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Htip =210 [nm] | 0.01, 0.01 | ||

The magnitude of the relative pore resistance increase ΔR/R0 (table 1) shows that the relatively large blunt tip blocks ion flow to the pore significantly at Htip=10 nm along the center line of the pores. Although the same tip was used for all measurements, the peak values of the ratio ΔR/R0 at Htip=10 nm are 0.54, 0.18, and 0.67 for pore thickness to radius of L/a=6.0 (2a=100 nm), 1.5 (2a=26 nm), and 5.7 (2a=7 nm), respectively. This demonstrates experimentally thatΔR/R0 depends on the ratio of L/a, not the diameter 2a, which is consistent with predictions in Equations (1) and (2) based on Ohm’s law. The SPM tip height dependence of ΔR/R0 in Figure 3b shows that for the large 100 nm pore, the ΔR/R0 was still measurable at Htip=200 nm. A 0.2% of maximum current blockage was measured with the large diameter and long pore at the lifting height of 500 nm. In the case of small diameter pores, the pore resistance change ΔR/R0 was not detected for lift heights over 110 nm as shown in Figure 3c and 3d. This is consistent with theoretical predictions that the electric field is negligible beyond a half sphere with the same radius as the pore,35 thus the detectable range of ΔR/R0 is expected to be shorter for pores with a smaller radius. The full width at half maximum of the pore relative resistance change profiles, ΔR/R0, are the same 0.54 μm for both the 26 nm (Fig. 3c) and the 7 nm (Fig. 3d) size nanopores. This is likely caused by the large dimension of the SPM tip.

2.3. Dependence of ΔR/R0 on tip location

Using the large 100 nm pore data in Fig. 3b, we create a contour plot of ΔR/R0 by plotting equal values of ΔR/R0 for different tip heights locations (Figure 4a). The shape of the ΔR/R0 contour is elliptical, similar to the equipotential plots for the model orifices by Gregg and Steidley.36

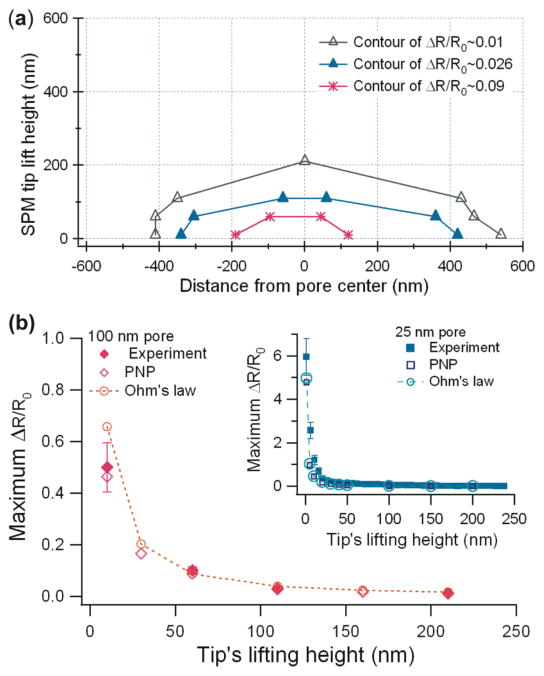

Figure 4.

Contour of ΔR/R0 equal value plot measured by the SPM tip extracted from the large 100 nm pore data in Fig. 3b (4a). Maximum pore resistance change ΔR/R0 in experiment and simulation as a function of the lift height of a tip (4b). The symbols represent experimental results for pores with diameters of 100 nm in 0.1 M KCl (◆) and 25 nm in 1 M KCl (■). The errors are the standard deviation of the Gaussian fits. The open symbols are data simulated using with PNP equations in the COMSOL Multiphysics software. The dotted lines are simulated using the same program with Ohm’s law only (no surface charge).

The plot of ΔR/R0 as a function of the SPM tip height for the large ~100 nm pore data in Fig. 4b shows that the ΔR/R0 is approximately inversely proportional to Htip, or ΔR/R0 ~1/Htip along the centerline of the pore.

Another measurement with a 25 nm pore in 1 M KCl with more data points (insert of Fig. 4b) also shows a similar result. To measure more data points at different lifting heights, instead of scanning a whole flat plane around a pore as explained in Figure 3, we located the pore with the tip, and then lifted the tip directly at increasing values of Htip while measuring ionic current. The measured maximum access resistance changes of the 25 nm diameter pore are plotted in Figure 4b (insert).

To better understand our experimental data, we simulated access resistance change (ΔR/R0) with Ohm’s law and Poisson and Nernst-Planck PNP equations (Multiphysics from COMSOL). The details of the simulation are explained in the supporting information. Briefly, using Ohm’s law or PNP equations, the access resistance can be calculated by 3D finite element simulation as shown in Figure 1a. The Nernst-Plank equation describes the motion of chemical ions in fluid. It accounts for the flux of ions under the influence of both an ionic concentration gradient (∇ci) and an electric field (−∇Φ).

| (3) |

Here Ji, Di, ci, and zi are the flux, diffusion constant, concentration, and charged species i, respectively. Φ is the local electric potential, u is the local electric potential and fluid velocity (set as zero in this work), and F, R, T are the Faraday constant, the gas constant, and the absolute temperature, respectively. The electric potential generated by chemical ions is described by the Poisson equation.

| (4) |

where ε is the dielectric constant of the fluid. The current passing through the pore is calculated by integrating both current densities from potassium ions and from chloride ions. The access resistance change without and with a SPM tip as described in Eq. (2), , can be simulated with Ohm’s law, or with PNP equations (3) and (4) if charges on the nanopore surface are considered.

We plot the simulated access resistance change (ΔR/R0) versus the lifting height as shown in Figure 4b together with the experimental data. The parameters used for the simulations are: temperature T = 298 K, diffusion constants of potassium ion DK = 1.975 × 10−9 m2/s and of chloride ion DCl = 2.032 × 10−9 m2/s, and relative dielectric constant ε= 80. Based on recent published work,12, 37 we assume the geometry of the nanopores to be an hour glass shape (Fig. 1a). For example, for a pore with 2a = 100 nm and L=280 nm (Fig. 3b) at Ψ = 60 mV bias, the simulated open pore current I0 =−2.21 nA. When a tip is put close to the nanopore at Htip =110 nm, the simulated current changed to Is= −2.14 nA, therefore the simulated (ΔIb/I0) = 0.03 and the total pore resistance change is ΔR/R0=0.03.

When the PNP model was used, the surface charge density was set at −0.02 C/m2 for silicon nitride nanopore surface31 and −0.06 C/m2 for the fused silica tip.38 At Htip=10 nm lifting height, the access resistance change ΔR/R0 simulated (⋄, Fig. 4b) was 39% less compared to Ohms’s law (○). At Htip=110 nm, the difference between the PNP model and Ohm’s law was reduced by 1%. The 39 % decrease of ΔR/R0 at Htip=10 nm is due to the electrical double layer near the tip surface enhacing in the local solution conductivity.39, 40. At Htip=110 nm, the increase in conductivity from the electrical double layer is ignorable since the double layer (~1 nm) is much less than the tip height of Htip=110 nm.

2.4. ΔR/R0 on Salt Concentration

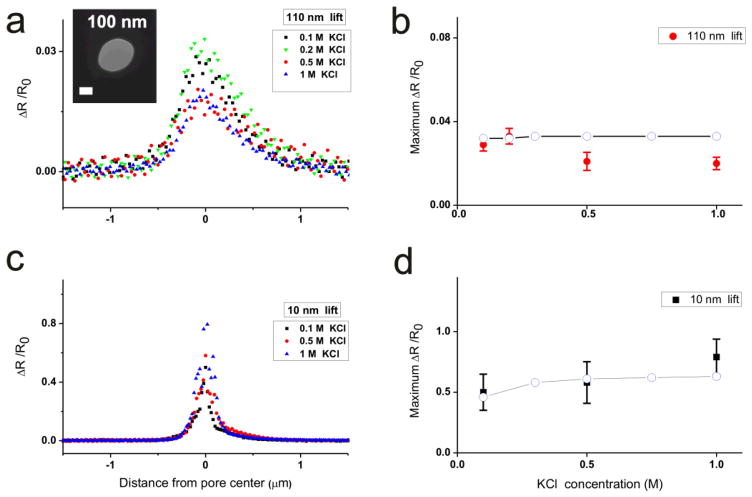

Ohm’s law predicts that solution conductivity does not affect the pore’s relative resistance change (ΔR/R0), however, the PNP equations expect that salt concentration does affect the pore’s relative resistance. We performed the same experiment with the large (2a~100 nm) pore at different KCl concentrations while keeping the tip height Htip as a constant. At Htip =110 nm, the ΔR/R0 distribution around the pore shown in Figure 5a did not change significantly at different KCl concentrations within experimental error. The maximum pore resistance change in Figure 5b shows the ΔR/R0 was about 0.03 as the KCl concentrations were changed.

Figure 5.

ΔR/R0 as a function of KCl concentration at the lift height of 110nm (a) and 10nm (c) from a 100 nm pore. (b) and (d) Maximum ΔR/R0 at different KCl concentrations in (a) and (c). The bias voltage was set at Ψ= −60 mV for the measurement. Simulation results with PNP equations are plotted with open circles (○). The inset in (a) is the TEM image of the pore used. The scale bar is 50 nm in the TEM image.

When the tip height was kept at 10 nm, the maximum access resistance changesΔR/R0 (Fig. 5c) were 0.50, 0.58, 0.79 at the KCl concentrations of 100 mM, 500 mM, 1M respectively. For a given height, the tip should cause the same geometric occlusion, however, at low salt concentrations surface charge effects can contribute to the local solution conductivity.38–40 As the salt concentration increases, the Debye length decreases. The Debye length is estimated to be ~1 nm at 0.1 M KCl and ~0.3 nm at 1 M KCl, so the current due to the surface charge relative to the total current is expected to increase at low salt concentrations for a tip height of 10 nm. Supporting this conclusion are numerical PNP solutions shown in Figure 5d that predict relative resistance changes of 0.46, 0.60, 0.64 at the KCl concentrations of 100 mM, 500 mM, 1 M. The surface charge contribution was negligible at Htip=110 nm for both experiment and numerical PNP simulation as shown in Figure 5b.

3. Conclusions

In this work, we report a newly constructed apparatus that integrates solid-state nanopore ionic current measurement with a Scanning Probe Microscope (SSN-SPM). The SSN-SPM system is capable of measuring the ionic current flow through a nanopore while a SPM tip scans the top of the pore. As the tip scans across the pore at various heights, it partially blocks the flow of ions to the pore, allowing a 3D current blockage map to be measured. Important nanopore parameters can be estimated from the 3D current blockage map: 1) how far the electric field extends above the physical boundary of the pore in 3D space, which will be useful to estimate at what distance a charged biomolecule will be captured;4, 11 2) the contour map of the relative resistance increase ΔR/R0 due to an increase in the pore access resistance, which has verified the access resistance concept experimentally 3) the minimum distance from the tip to the pore at which the resistance change ΔR/R0 caused by a tip is negligible for future tethered single molecule experiments. In addition, the ΔR/R0 maps as functions of nanopore geometry and salt concentration show that ΔR/R0 is close to zero when the tip is about five times of the pore diameter, 2a, away from the center of the pore entrance regardless of the salt concentration investigated. The ratio ΔR/R0 depended on L/a, the ratio of the pore length and its radius, and on the surface charge as the PNP equations predicted. When the SPM tip is very close to the pore surface, ~10 nm, our results showed the ΔR/R0 depended on salt concentration indicating a deviation from Ohm’s law. Both experiment and COMSOL simulation show that the access resistance decreased inversely proportional to the tip height along the centerline of the pore.

The results reported in this work provide direct experimental measurement of access resistance of solid-state nanopores. As more research groups develop high resolution nanopore sensing devices, access resistance becomes a more important parameter and it becomes a dominant component to the pore resistance as a pore is thinner. Access resistance is also an important parameter for understanding the DNA translocation process, for the design of future nanopore experiments, for the interpretation of current blockage data, and furthermore for the design of using nanopores to probe single DNA molecules attached to the SPM tips.

4. Experimental Section

Nanopore fabrication

The nanopores used in this study are fabricated in a free standing silicon nitride membrane supported by 4 mm x 6 mm silicon substrate. The thickness of the silicon nitride membrane is 275 nm and is deposited by low pressure chemical vapor deposition on both sides of the 380 μm thick (100) silicon substrate. The freestanding membrane window is approximately 30 μm x 30 μm made by procedures including photolithography, reactive ion etching, followed by anisotropic wet KOH etching. Initially, a 100 nm size pore is milled on the free standing membrane using a focused ion beam (FIB, Micrion 9500). A 3 keV noble gas Ne ion beam is used to shrink the ~100 nm FIB pore to the desired pore size.33, 41

Measurement and analysis

The nanopore chips are immersed in acetone and isopropyl alcohol for 30 min in series, and then are soaked in a one to one solution of ethanol and DI water for more than a day. Electrodes are made by chloriding silver wires in bleach (Clorox). Every electrode is chlorided for one hour before measurements. The current through a nanopore is recorded by an integrated patch-clamp amplifier Axopatch 200B (Moleculer Devices). The Scanning Probe Microscope stage which holds the sample holder with a nanopore chip and the headstage of the amplifier are enclosed in a Faraday cage. Recorded data are analyzed by custom routines written in MATLAB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge discussion and helpful criticism of this work by J. Golovchenko, A. Aksimentiev, and D. Hoogerheide. We thank G. M. King for his helpful advice and discussion in the experimental setup, Dr. D. Gazum for his assistance in SPM setup. We also thank B. Ledden and E. Graef for nanopore fabrication and TEM imaging. This work was supported by the NIH (R21HG004776) and partially supported by NSF/MESEC (080054), ABI-1114, and NCRR/1P30RR031154-01.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available on the WWW under http://www.small-journal.com or from the author.

References

- 1.Astier Y, Braha O, Bayley H. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1705–1710. doi: 10.1021/ja057123+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meller A, Nivon L, Branton D. Physical Review Letters. 2001;86(15):3435–3438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakane JJ, Akeson M, Marziali A. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2003;15:R1365–93. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Stein D, McMullan C, Branton D, Aziz MJ, Golovchenko JA. Nature. 2001 Jul 12;412:166–169. doi: 10.1038/35084037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Ling XS, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Nat Mater. 2003;2:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nmat941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatesan BM, Dorvel B, Yemenicioglu S, Watkins N, Petrov I, Bashir R. Adv Mater. 2009;21:1–6. doi: 10.1002/adma.200803786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakane J, Akeson M, Marziali A. Electrophoresis. 2002;23(16):2592–601. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:16<2592::AID-ELPS2592>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vodyanoy I, Bezrukov SM. Biophys J. 1992;62:10–11. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81762-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanunu M, Morrison W, Rabin Y, Grosberg AY, Meller A. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(2):160–165. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershow M, Golovchenko JA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007 Dec;2:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowalczyk SW, Grosberg AY, Rabin Y, Dekker C. Nanotechnology. 2011;22(31) doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/31/315101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garaj S, Hubbard W, Reina A, Kong J, Branton D, Golovchenko JA. Nature. 2010;467(7312):190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant CA, Healy K, Wanunu M, Ray V, Peterman N, Bartel J, Fischbein MD, Venta K, Luo Z, Johnson ATC, Drndi M. Nano Lett. 2010;10(8):2915–2921. doi: 10.1021/nl101046t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider GF, Kowalczyk SW, Calado VE, Pandraud G, Zandbergen HW, Vandersypen LMK, Dekke C. Nano Lett. 2010;10(8):3163–3167. doi: 10.1021/nl102069z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fologea D, Uplinger J, Thomas B, McNabb DS, Li J. Nano Lett. 2005;5(9):1734–1737. doi: 10.1021/nl051063o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Gershow M, Stein D, Brandin E, Golovchenko JA. Nat Mater. 2003;2:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nmat965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyser UF, Does Jvd, Dekker C, Dekker NH. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77(10) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyser UF, Koeleman BN, Dorp Sv, Krapf D, Smeets RM, Lemay SG, Dekker NH, Dekker C. Nature Physics. 2006;2:473–477. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trepagnier EH, Radenovic A, Sivak D, Geissler P, Liphardt J. Nano Lett. 2007;7(9):2824–2830. doi: 10.1021/nl0714334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng H, Ling XS. Nanotechnology. 2009:20. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/18/185101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keyser UF, Krapf D, Koeleman BN, Smeets RMM, Dekker NH, Dekker C. Nano Lett. 2005;5(11):2253–2256. doi: 10.1021/nl051597p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CC, Derylo MA, Baker LA. Anal Chem. 2009;81(11):4742–4751. doi: 10.1021/ac900065p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansma PK, Drake B, Marti O, Gould SA, Prater CB. Science. 1989;243(4891):641–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2464851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King GM, Golovchenko JA. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(21) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.216103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein DM, McMullan CJ, Li Jiali, Golovchenko JA. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75:900–905. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Healy K, Schiedt B, Morrison AP. Nanomedicine. 2007;2(6):875–897. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3. Sunderland MA: Sinauer Assoc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall JE. JGen Physiol. 1975;66:531–532. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguilella-Arzo M, Aguilella VM, Eisenberg RS. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:314–322. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White HS, Bund A. Langmuir. 2008;24:2212–2218. doi: 10.1021/la702955k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I. Biophys J. 1993;64:16–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Golovchenko JA. In: Micro and Nano Technologies in Bioanalysis. Lee JW, Foote RS, editors. Human Press; Pringer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York: 2009. pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choy JL, Parekh SH, Chaudhuri O, Liu AP, Bustamante C, Footer MJ, Theriot JA, Fletcher DA. Rev Sci Instrum. 2007;78 doi: 10.1063/1.2727478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sokirko AV. Bioelectrochemistry and Bioenergetics. 1994;33:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregg EC, Steidley KD. Biophys J. 1965;5:393–405. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(65)86724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MJ, McNally B, Murata K, Meller A. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:205302. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein D, Kruithof M, Dekker C. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93(3):035901-1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.035901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoogerheide DP, Garaj S, Golovchenko JA. PHYS REV LETT. 2009;102 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.256804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smeets RM, Keyser UF, Krapf D, Wu M-Y, Nynke DH, Dekker C. Nano Lett. 2006;6(1):89–95. doi: 10.1021/nl052107w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai Q, Ledden B, Krueger E, Golovchenko JA, Li J. J Appl Phys. 2006;100:024914. doi: 10.1063/1.2216880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.