Abstract

Sirtuins, a class of enzymes known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylases have been shown to regulate a variety of biological processes, including aging, transcription, and metabolism. Sirtuins are considered promising targets for treating several human diseases. There are seven sirtuins in humans Sirt1-7. Small molecules that can target a particular human sirtuin are important for drug development and for fundamental studies of sirtuin biology. Here we demonstrate that thiosuccinyl peptides are potent and selective Sirt5 inhibitor. The design of this inhibitor is based on our recent discovery that Sirt5 prefers to catalyze the hydrolysis of malonyl and succinyl groups, rather than an acetyl group, from lysine residues. Furthermore, among the seven human sirtuins, Sirt5 is the only one that has this unique acyl group preference. This study demonstrates that the different acyl group preference of different sirtuins can be conveniently utilized to develop small molecules that selectively target different sirtuins.

Keywords: sirtuin, sirt5, lysine succinylation, lysine malonylation, lysine acetylation

Sirtuins are a class of enzymes known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylases.1 Humans have seven sirtuins, Sirt1-7, which are known to play important roles in many biological processes, such as the regulation of life span, transcription, and metabolism.2 Small molecules that can regulate sirtuin activity have been shown to have potential in treating several human diseases,3 such as cancer,4–7 diabetes,8,9 and Parkinson’s disease.10 Although there are controversies regarding the link between sirtuins and longer lifespan11 and the effectiveness of Sirt1 activators,12 it is clear that sirtuins play important biological functions. Inhibitors that are specific for a particular sirtuin will be very useful for investigating the biological function and therapeutic potential of the specific sirtuin. The major obstacle in the development of small molecules that can regulate sirtuin activity is the fact that four of the seven human sirtuins (Sirt4-7) have either very weak or no deacetylase activity.1,2 This poses two difficulties for the development of small molecules that can regulate sirtuin activity. First, it is hard to develop inhibitors or activators that target these sirtuins because no robust activity assay is available. Second, it is hard to tell whether the inhibitors/activators that target Sirt1, Sirt2, and Sirt3 can also target Sirt4-7.

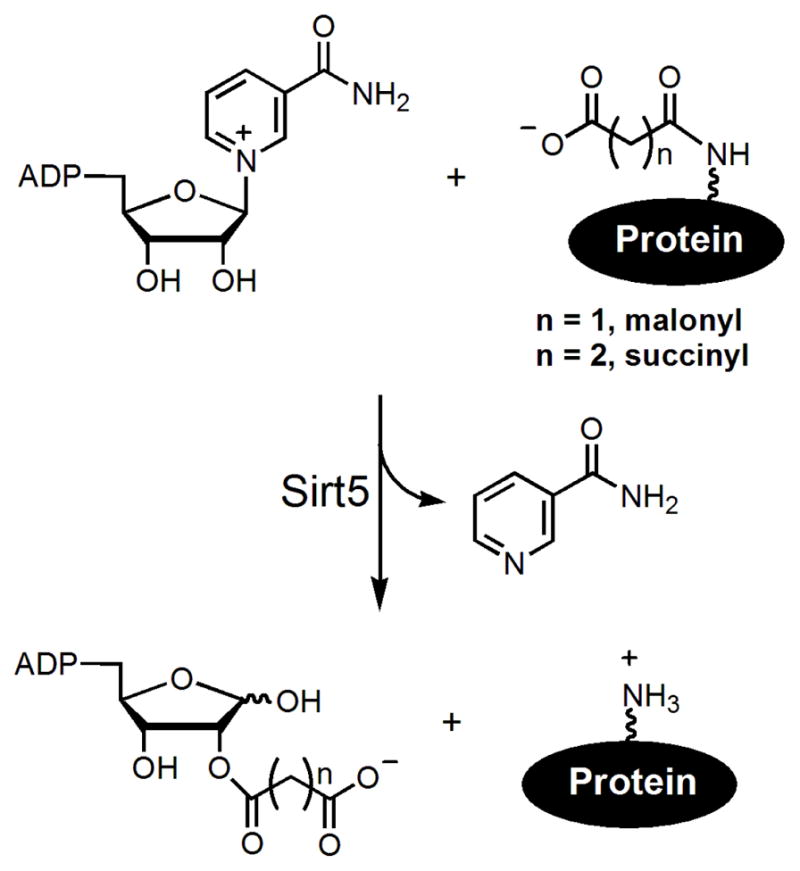

Recently, our laboratory discovered that human Sirt5, a mitochondrial sirtuin with weak deacetylase activity, is an efficient demalonylase and desuccinylase (Figure 1).13 The specificity for negatively charged malonyl and succinyl group is determined by a conserved Arg and Tyr residue in most Class III sirtuins.13 Several mitochondrial proteins are malonylated and succinylated on lysine residues.13 Sirt5 serves to remove some of the malonyl and succinyl groups from the proteins, possibly as a mechanism to reversibly regulate protein activity in mitochondria.13 Independently, Zhao and coworkers also identified lysine succinylation in E. coli as a new post-translational modification.14

Figure 1.

The NAD-dependent demalonylation and desuccinylation reactions catalyzed by Sirt5.

The discovery of the robust enzymatic activity assay now provides a reliable assay for the development of Sirt5 inhibitors.13 In addition, since Sirt5’s acyl group preference is unique among all the human sirtuins,13 we reasoned that we can take advantage of this to develop Sirt5-specific inhibitors. Such inhibitors would be valuable tools to study the biological function of Sirt5 in cells and to evaluate whether Sirt5 would be a good target for treating human diseases. Herein we report that thiosuccinyl peptides can be used as Sirt5-specific inhibitors.

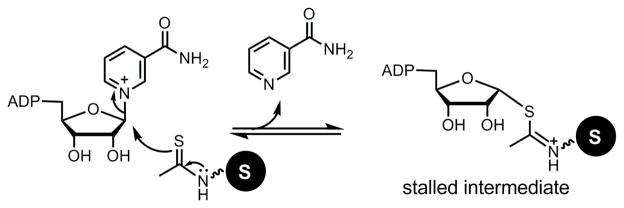

Thioacetyl peptides can inhibit sirtuins with deacetylase activities by forming a stalled covalent intermediate (Figure 2).19–21 Because Sirt5 uses the same mechanism as the deacetylases to remove malonyl and succinyl groups,13 we reasoned that thiosuccinyl or thiomalonyl peptides would be mechanism-based inhibitors for Sirt5. Because other sirtuins do not recognize malonyl and succinyl lysine peptides,13 we predicted that thiomalonyl and thiosuccinyl peptides should be Sirt5-specific inhibitors. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized a histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) thiosuccinyl peptide (H3K9TSu, Figure 3). We chose to use thiosuccinyl group because succinyl lysine is more stable (malonyl lysine is prone to decarboxylation).13

Figure 2.

Mechanism-based inhibition of sirtuins with deacetylase activity by thioacetyl peptides. The thioacetyl peptides can undergo the first step of the sirtuin-catalyzed deacetylation reaction, forming the covalent 1′-S-alkylimidate intermediate. This intermediate is relatively stable and cannot proceed further in the deacetylation reaction pathway, thus inhibiting sirtuins.

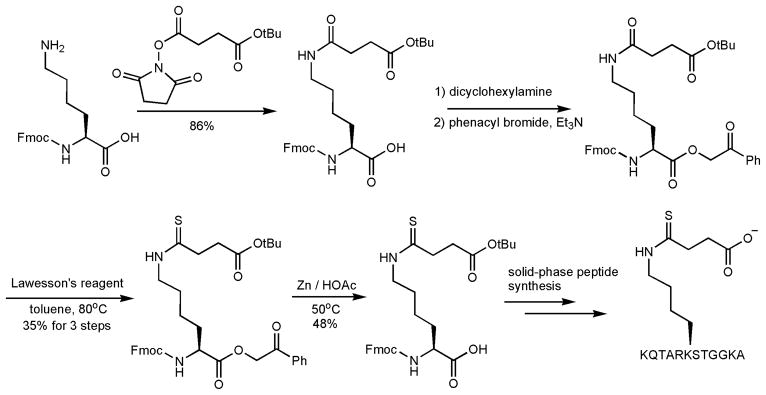

Figure 3.

The synthesis of the H3K9TSu peptide and other thiosuccinyl peptides.

The synthesis of H3K9TSu peptide is shown in Figure 3. L-Fmoc-Lys-OH was first coupled to the mono-t-butyl succinate. The free carboxylate of Lys was then protected as the phenacyl ester. The fully protected Lys was then treated with Lawesson’s reagent to site-specifically introduce the thiosuccinyl functional group to the side chain of Lys. The phenacyl ester was then removed with zinc in acetic acid and the resulting compound was then used in standard Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis along with several L-Fmoc-amino acids to give the desired H3K9TSu peptide, KQTAR(TSuK)STGGKA. As a control, we also synthesized a H3K9 thioacetyl peptide (H3K9TAc), KQTAR(TAcK)STGGKA using published procedures.19

We then assayed the inhibition of Sirt1, 2, 3, and 5 with the H3K9TSu and H3K9TAc peptides. The IC50 values are shown in Table 1. All assays were carried out under identical enzyme (1 μM) and substrate (0.3 mM acyl peptide, 0.5 mM NAD) concentrations. For Sirt5, we used a H3K9 succinyl peptide, KQTAR(SuK)STGGKA as the substrate. For Sirt1-3, we used a H3K9 acetyl peptide, KQTAR(AcK)STGGKA, as the substrate. The Sirt5 (or Sirt1-3) enzyme was added last to initiate the reaction and thus there was no pre-incubation of the sirtuins with the inhibitors before initiation of the enzymatic reaction. H3K9TSu does not inhibit Sirt1-3 even at 100 μM concentration, but inhibits Sirt5 with an IC50 value of 5 μM (the dose-response curves can be found in Supporting Information). In contrast, the H3K9TAc peptide inhibits Sirt1-3 with IC50 values of 1–2 μM, but does not inhibit Sirt5 at 100 μM. The results demonstrate that the H3K9TSu peptide is a Sirt5-specific inhibitor.

Table I.

IC50 values of different inhibitors for different sirtuins. The reported values are shown in brackets.

| IC50 (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | H3K9TSu | H3K9TAc | nicotinamide | AGK2 | suramin | sirtinol |

| Sirt1 | >100* | 1 | 120 (<50)14 | 200(>40)10 | 5 (0.3)15 | 200 (131)16 |

| Sirt2 | >100* | 2 | 75 (32)17 | 150 (3.5)10 | 10 (1.2)15 | 100 (38)18 |

| Sirt3 | >100* | 2 | 50 | 200 (>40)10 | 75 | 150 |

| Sirt5 | 5 | >100* | 150 | >100** | 25 (22)20 | >100* |

No inhibition at 100 μM.

40% inhibition at 100 μM.

Many inhibitors have been developed for Sirt1, Sirt2, and Sirt3. We obtained several of them from commercial sources and tested whether they can also inhibit Sirt5 (Table I). Suramin, which has been reported to be a Sirt5 inhibitor,22 inhibits Sirt5 with an IC50 value of 25 μM but also inhibits Sirt1-3 (IC50 values from 5uM to 75uM). In addition, nicotinamide and AGK2 (a reported Sirt2-selective inhibitor)10 also showed some inhibition for Sirt5 (Table 1). However, the IC50 values are much higher and they are not selective compared to H3K9TSu. Thus, the H3K9TSu peptide is not only the first Sirt5-specific inhibitor, but probably also the most potent Sirt5 inhibitor reported thus far.

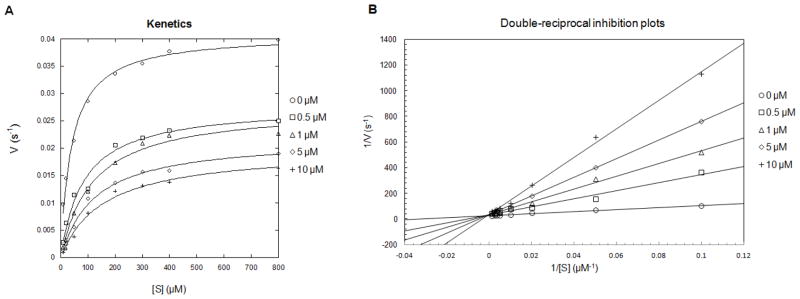

We further performed kinetic studies to find out whether H3K9TSu is competitive with substrate. Initial velocities at saturating NAD concentrations were determined at varied concentration of H3K9Su as the substrate and H3K9TSu as the inhibitor. At different inhibitor concentrations, initial velocities (V) versus substrate concentrations were plotted at each inhibitor concentration, and the data were fitted to Henri-Michaelis-Menten equation.23 As shown in Figure 4A, the apparent Km value for H3K9Su was increased by increasing the concentration of H3K9TSu inhibitor. Furthermore, the data were plotted as 1/V versus 1/[S], revealing a series of lines that intersected at the 1/V axis at each inhibitor concentration (Figure 4B). The feature of the double reciprocal plot is consistent with H3K9Su being a competitive inhibitor.

Figure 4.

(A) Henri-Michaelis-Menten plots for the effects of H3K9TSu inhibitor on the velocity of Sirt5 desuccinylation. (B) Double-reciprocal plots for the effects of H3K9TSu inhibitor on the velocity of Sirt5 desuccinylation.

Finally, to extend the application of thiosuccinyl peptides as Sirt5 inhibitors, we synthesized several shorter thiosuccinyl peptides. The IC50 values were shown in Table 2. The longer thiosuccinyl peptide is a more potent inhibitor for Sirt5 (Table 2, compare entry 1 to entries 2–6). However, with five-residue thiosuccinyl peptides, the IC50 value can still be as low as 25 μM (Table 2, entries 4–6). Interestingly, peptides with the thiosuccinyl lysine residue at the C-terminus or N-terminus (Table 2, entries 2 and 3) were less potent than peptides with the thiosuccinyl lysine residue in the middle (Table 2, entries 4–6). Thus, it may be possible to obtain Sirt5 inhibitors with lower molecular weights.

Table 2.

IC50 values of shorter thiosuccinyl peptides for Sirt5.

| Thiosuccinyl lysine peptides | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | KQTAR(TSuK)STGGKA, H3K9TSu | 5 |

| 2 | KQTAR(TSuK) | 100 |

| 3 | (TSuK)STGGKA | 100 |

| 4 | AR(TSuK)ST | 30 |

| 5 | Ac-AR(TSuK)ST-NH2 | 40 |

| 6 | Ac-RR(TSuK)RR-NH2 | 25 |

In summary, we have shown that the H3K9TSu peptide is a mechanism-based and competitive inhibitor specific for Sirt5. We also showed that shorter peptides with thiosuccinyl lysine can maintain the inhibition for Sirt5. This opens up possibilities for the development of more potent and more cell-permeable inhibitors specific for Sirt5 to study the biological function of Sirt5 and explore the therapeutic potential of Sirt5 inhibition. Given that protein succinylation and malonylation (which are controlled by Sirt5) have not been studied before, small molecule inhibitors specific for Sirt5 will also be valuable tools to control the levels of protein succinylation and malonylation, which can facilitate the study of the biological function of these protein post-translational modifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

H.L. acknowledges The Camille and Henry Dreyfus New Faculty Award Program and NIH (GM086703 and NS073049) for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental methods for the synthesis of peptides and HPLC assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sauve AA, Wolberger C, Schramm VL, Boeke JD. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:435–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michan S, Sinclair D. Biochem J. 2007;404:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milne JC, Denu JM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao W, Kruse JP, Tang Y, Jung SY, Qin J, Gu W. Nature. 2008;451:587–590. doi: 10.1038/nature06515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heltweg B, Gatbonton T, Schuler AD, Posakony J, Li H, Goehle S, Kollipara R, DePinho RA, Gu Y, Simon JA, Bedalov A. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4368–4377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Au Q, Zhang M, Barber JR, Ng SC, Zhang B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:729–733. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara E, Mai A, Calvanese V, Altucci L, Lopez-Nieva P, Martinez-Chantar ML, Varela-Rey M, Rotili D, Nebbioso A, Ropero S, Montoya G, Oyarzabal J, Velasco S, Serrano M, Witt M, Villar-Garea A, Inhof A, Mato JM, Esteller M, Fraga MF. Oncogene. 2008;28:781–791. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, Carney DP, Smith JJ, Gagne DJ, Jin L, Boss O, Perni RB, Vu CB, Bemis JE, Xie R, Disch JS, Ng PY, Nunes JJ, Lynch AV, Yang H, Galonek H, Israelian K, Choy W, Iffland A, Lavu S, Medvedik O, Sinclair DA, Olefsky JM, Jirousek MR, Elliott PJ, Westphal CH. Nature. 2007;450:712–716. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guarente L. Nature. 2006;444:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Outeiro TF, Kontopoulos E, Altmann SM, Kufareva I, Strathearn KE, Amore AM, Volk CB, Maxwell MM, Rochet JC, McLean PJ, Young AB, Abagyan R, Feany MB, Hyman BT, Kazantsev AG. Science. 2007;317:516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1143780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper MD, Hoddinott M, Sutphin GL, Leko V, McElwee JJ, Vazquez-Manrique RP, Orfila AM, Ackerman D, Au C, Vinti G, Riesen M, Howard K, Neri C, Bedalov A, Kaeberlein M, Soti C, Partridge L, Gems D. Nature. 2011;477:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacholec M, Bleasdale JE, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, Flynn D, Garofalo RS, Griffith D, Griffor M, Loulakis P, Pabst B, Qiu X, Stockman B, Thanabal V, Varghese A, Ward J, Withka J, Ahn K. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8340–8351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du J, Zhou Y, Su X, Yu J, Khan S, Jiang H, Kim J, Woo J, Kim JH, Choi BH, He B, Chen W, Zhang S, Cerione RA, Auwerx J, Hao Q, Lin H. Science. 2011;334:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45099–45107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trapp J, Meier R, Hongwiset D, Kassack Matthias U, Sippl W, Jung M. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:1419–1431. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mai A, Massa S, Lavu S, Pezzi R, Simeoni S, Ragno R, Mariotti FR, Chiani F, Camilloni G, Sinclair DA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7789–7795. doi: 10.1021/jm050100l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neugebauer RC, Uchiechowska U, Meier R, Hruby H, Valkov V, Verdin E, Sippl W, Jung M. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1203–1213. doi: 10.1021/jm700972e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grozinger CM, Chao ED, Blackwell HE, Moazed D, Schreiber SL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38837–38843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fatkins DG, Monnot AD, Zheng W. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3651–3656. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith BC, Denu JM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14478–14486. doi: 10.1021/bi7013294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawse WF, Hoff KG, Fatkins DG, Daines A, Zubkova OV, Schramm VL, Zheng W, Wolberger C. Structure. 2008;16:1368–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuetz A, Min J, Antoshenko T, Wang CL, Allali-Hassani A, Dong A, Loppnau P, Vedadi M, Bochkarev A, Sternglanz R, Plotnikov AN. Structure. 2007;15:377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Copeland RA. Enzymes. WILEY-VCH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.