Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic skin disease with high heritability. Apart from filaggrin (FLG), the genes influencing AD are largely unknown. We conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis of 5,606 cases and 20,565 controls from 16 population-based cohorts and followed up the ten most strongly associated novel markers in a further 5,419 cases and 19,833 controls from 14 studies. Three SNPs met genome-wide significance in the discovery and replication cohorts combined: rs479844 upstream of OVOL1 (OR=0.88, p=1.1×10−13) and rs2164983 near ACTL9 (OR=1.16, p=7.1×10−9), genes which have been implicated in epidermal proliferation and differentiation, as well as rs2897442 in KIF3A within the cytokine cluster on 5q31.1 (OR=1.11, p=3.8×10−8). We also replicated the FLG locus and two recently identified association signals at 11q13.5 (rs7927894, p=0.008) and 20q13.3 (rs6010620, p=0.002). Our results underline the importance of both epidermal barrier function and immune dysregulation in AD pathogenesis.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases with prevalence rates of up to 20% in children and 3% in adults. It commonly starts during infancy and frequently precedes or co-occurs with food allergy, asthma and rhinitis1 . AD shows a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations and is characterized by dry skin, intense pruritus, and a typical age-related distribution of inflammatory lesions with frequent bacterial and viral superinfections1. Profound alterations in skin barrier function and immunologic abnormalities are considered key components affecting the development and severity of AD, but the exact cellular and molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood1 .

There is substantial evidence in support of a strong genetic component in AD; however, knowledge on the genetic susceptibility to AD is rather limited2,3. So far, only null mutations in the epidermal structural protein filaggrin gene (FLG) have been established as major risk factors4,5 .

The only genome-wide association study (GWAS) on AD in European populations so far identified a novel susceptibility locus on 11q13.5, downstream of C11orf306. A recent second GWAS in a Chinese Han population identified two novel loci, one of which also showed evidence for association in a German sample (rs6010620, 20q13.33)7. In a collaborative effort to unravel additional risk genes for AD, we conducted a well powered two-staged genome-wide association meta-analysis in The EArly Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) Consortium.

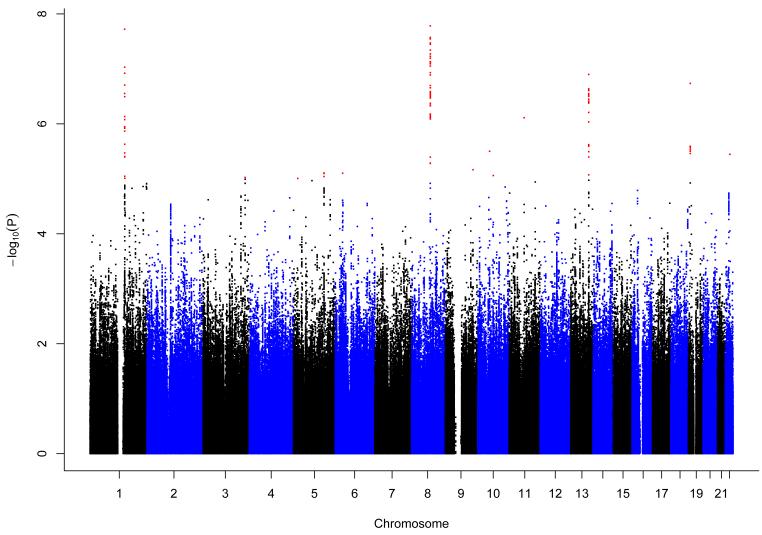

In the discovery analysis of 5,606 AD cases and 20,565 controls from 16 population-based cohorts of European descent (Supplementary Tables 1,2) there was little evidence for population stratification at study level (λGC<=1.08) or at the meta-analysis level (λGC=1.02), but an excess of association signals beyond those expected by chance (Supplementary Figs.1,2).

SNPs from two regions reached genome-wide significance in the discovery meta-analysis (Fig.1; Supplementary Table 3): rs7000782 (8q21.13, ZBTB10, OR=1.14, p=1.6×10−8) and rs9050 (1q21.3, TCHH, OR=1.33, p=1.9×10−8). Given the proximity of rs9050 to the well-established AD susceptibility gene FLG4,5, we evaluated whether the observed association was due to linkage disequilibrium (LD) with FLG mutations. Despite low correlation between rs9050 and the two most prevalent FLG mutations (in ALSPAC (The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children): r2=0.257 for R501X, r2=0.001 for 2282del4) and high levels of recombination (peak of 20cM/Mb at ~150.4Mb in HapMap) between the TCHH and FLG regions, in a meta-analysis across eight studies conditional on the two FLG mutations, rs9050 was no longer associated with AD (OR=0.98, p=0.88) (Supplementary Fig.3) and was therefore not investigated further. rs9050 might tag a far-reaching haplotype on which the FLG null mutations occur, but we cannot exclude that there are additional AD risk variants in this complex region.

Figure 1. Manhattan plot for the discovery genome-wide association meta-analysis of atopic dermatitis.

after excluding all SNPs MAF<1% and Rsqr<0.3 or proper_info<0.4. λ=1.017. SNPs with p<1×10−5 are shown in red.

The 11q13.5 locus previously reported to be associated in the only other European GWAS on AD to date6 was confirmed in our meta-analysis (rs7927894 p=0.008, OR=1.07, 95%CI 1.02-1.12) (Supplementary Fig.4). So was the variant rs6010620 reported in a recent Chinese GWAS7 (p=0.002, OR=1.09, 95%CI 1.03-1.15).

Of the 15 loci reported to be associated with asthma or total serum IgE levels in a recent GWAS8, two showed suggestive evidence for association with AD (IL13:rs1295686, p=0.0008 and rs20541, p=0.0007; STAT6:rs167769 p=0.0379) (Supplementary Table 4).

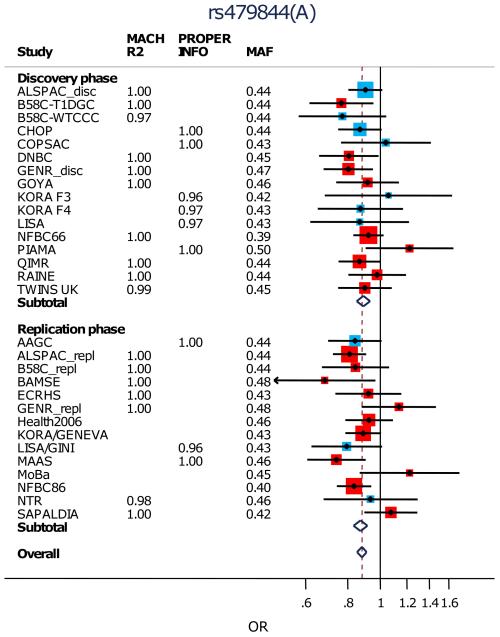

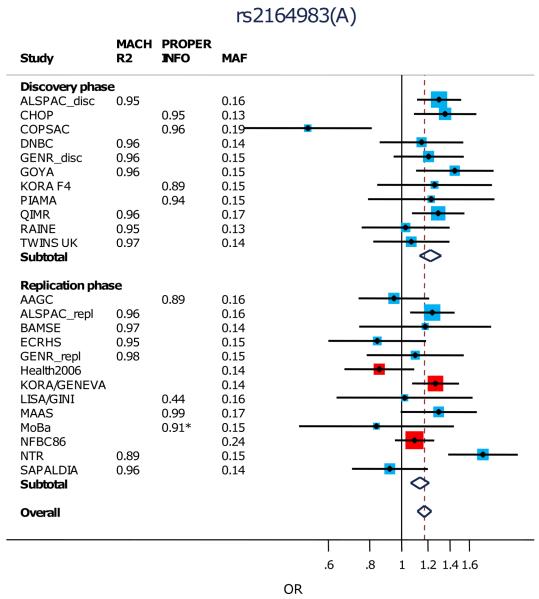

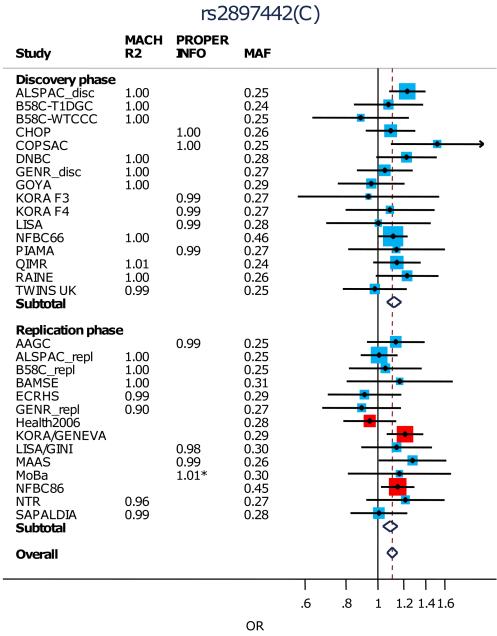

After excluding the rs9050 SNP, we attempted to replicate the remaining 10 most strongly associated loci (P<10−5 in discovery, Table 1; Supplementary Table 3; Fig.2; Supplementary Fig.5) in 5,419 cases and 19,833 controls from 14 studies (Supplementary Tables 1,2). Three of the ten SNPs showed significant association after conservative Bonferroni correction (p<0.05/10=0.005) in the replication meta-analysis (and same direction of effect as the discovery meta-analysis): rs479844 near OVOL1, rs2164983 near ACTL9, and rs2897442 in intron 8 of KIF3A (Table 1; Fig. 2). All three SNPs reached genome-wide significance in the combined meta-analysis of discovery and replication sets: rs479844 (p=1.1×10−13, OR=0.88), rs2164983 (p=7.1×10−9, OR=1.16) and rs2897442 (p=3.8×10−8, OR=1.11). In contrast, rs7000782, which had reached genome-wide significance in the discovery analysis, showed no evidence of association in replication (p=0.296). There was no evidence of interactions between the three replicated SNPs (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 1. Discovery and replication results of the loci associated with atopic dermatitis.

Results are for the fixed effect inverse-variance meta-analysis, with genomic control applied to the individual studies in the discovery meta-analysis. Stage I denotes discovery, II denotes replication and I+II denotes the combined analysis. The heterogeneity p-value (het pvalue), testing for overall heterogeneity between all discovery and replication studies was generated using Cochran’s Q-test for heterogeneity. All OR (odds ratios) are given with the minor allele representing the effect allele. CI denotes the confidence interval

| Chr | SNP | Position (bp) |

Gene | Effect allele |

Other allele |

Effect allele freq |

Stage | N | OR (95% CI) | pvalue | het pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | rs479844 | 65308533 | OVOL1 | A | G | 0.44 | I | 26,151 | 0.89 (0.85, 0.93) |

7.8E-07 | |

| II | 25,098 | 0.87 (0.83,0.92) | 2.4E-08 | ||||||||

| I+II | 51,249 | 0.88 (0.85,0.91) | 1.1E-13 | 0.23 | |||||||

| 19 | rs2164983 * |

8650381 | ACTL9 | A | C | 0.15 | I | 17,403 | 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) |

1.8E-07 | |

| II | 22,996 | 1.11 (1.04,1.19) | 0.002 | ||||||||

| I+II | 40,399 | 1.16 (1.10,1.22) | 7.1E-09 | 0.004 | |||||||

| 5 | rs2897442 | 132076926 | KIF3A | C | T | 0.29 | I | 26,164 | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) |

7.8E-06 | |

| II | 25,064 | 1.09 (1.04,1.15) | 0.001 | ||||||||

| I+II | 51,228 | 1.11 (1.07,1.15) | 3.8E-08 | 0.52 |

rs2164983 was not included in the HapMap release 21 and so was missing for some discovery cohorts. This SNP showed evidence of heterogeneity (p=0.004). The random effects combined (I+II) result for this SNP was OR=1.14 (95%CI 1.05, 1.24) p=0.001.

Figure 2. Forest plots for the association of (a) rs479844, (b) rs2164983 and (c) rs2894772 with atopic dermatitis.

All OR are reported with the minor allele (shown in brackets) as the effect allele. *MoBa imputation quality score was ‘info’ from PLINK.

GENR=Generation R. rs2164983 was not included in the HapMap release 21 and so was missing for some discovery cohorts.

Black points indicate the Odds Ratios (ORs) and the horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each study. Arrows are used to show where a CI extends beyond the range of the plot.

The sizes of the red and blue boxes indicate the relative weight of each study (using inverse variance weighting). Blue boxes indicate SNPs that were imputed and red boxes indicate SNPs on the genome-wide genotyping chip for the discovery cohorts and either on the genome-wide genotyping chip or individually genotyped for the replication cohorts. Only Health2006, KORA/GENEVA and NFBC86’ underwent individual SNP genotyping.

The subtotals (for discovery and replication) and overall ORs and CIs are indicated by the centre and range of the diamonds.

rs479844 (at 11q13.1) is located <3kb upstream of OVOL1. The pattern of LD is complex at this locus, but there is low recombination between rs479844 and this gene in Europeans (Supplementary Fig.2). OVOL1 belongs to a highly conserved family of genes involved in the regulation of the development and differentiation of epithelial tissues and germ cells9-11 . It acts as a c-Myc repressor in keratinocytes, is activated by the β-catenin-LEF1 complex during epidermal differentiation, and represents a downstream target of Wg/Wnt and TGF-β/BMP7-Smad4 developmental signaling pathways10,12,13. Apart from their role in the organogenesis of skin and skin appendages14,15, these pathways are also implicated in the postnatal regulation of epidermal proliferation and differentiation16-18. Disruption of OVOL1 in mice leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation, hair shaft abnormalities, kidney cysts, and defective spermatogenesis10,11. In addition, OVOL1 regulates loricrin expression thereby preventing premature terminal differentiation10. Thus, it might be speculated whether variation at this locus influences epidermal proliferation and/or differentiation, which is known to be disturbed in AD. Analysis of transcript levels of all genes within 500 kb of rs479844 (OVOL1) in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) from 949 ALSPAC individuals revealed a significant association between rs479844 and a nearby hypothetical protein DKFZp761E198 (p=7×10−5). Likewise, analysis of SNP-transcript pairs in the MuTHER (Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource) skin genome-wide expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) pilot database of 160 samples19 provided suggestive evidence for an association in the same direction with DKFZp761E198 in one of the twin sets (Supplementary Fig.6). Further investigations are needed to clarify if the causal variant(s) at this locus exerts its effect through this transcript.

rs2164983 (at 19p13.2) is located in an intergenic region 70kb upstream of ADAMTS10 and 18kb downstream of ACTL9 (encoding a hypothetical protein). ADAMTS are a group of complex secreted zinc-dependent metalloproteinases, which bind to and cleave extracellular matrix components, and are involved in connective tissue remodelling and extracellular matrix turnover20,21. Actin proteins have well-characterized cytoskeletal functions, are important for the maintenance of epithelial morphology and cell migration, and have also been implicated in nuclear activities22-24. The low recombination between rs2164983 and ACTL9 and recombination peak between rs2164983 and ADAMTS10 in CEU HapMap individuals (Supplementary Fig.2) suggests the functional variant may be located within the ACTL9 region. There was no evidence for association between this SNP and any expression level of genes within 500kb in the ALSPAC LCL eQTL analysis, nor the MuTHER skin eQTL data (Supplementary Fig.6).

rs2897442 is located in intron 8 of KIF3A, which encodes a subunit of kinesin-II complex, required for the assembly of primary cilia, essential for Hedgehog signaling and implicated in β-catenin-dependent Wnt signaling to induce expression of a variety of genes that influence proliferation and apoptosis25,26. Of note, KIF3A is located in the 5q31 region, which is characterized by a complex LD pattern and contains a cluster of cytokine and immune-related genes, and has been linked to several autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis27,28, Crohn’s disease29,30, and asthma

8,29,31 (Supplementary Table 4). In particular, distinct functional IL13 variants have been associated with asthma susceptibility32. Although rs2897442 is within the KIF3A gene, there is little recombination between this region and IL4 (interleukin 4). But there does appear to be a recombination peak between this region and IL13 (Supplementary Fig.7a). However, a secondary signal also appears to be present in the IL13/RAD50 region, and when conditioning on rs2897442 in our discovery meta-analysis, the signal in the IL13/RAD50 region remains, providing evidence of two independent signals (Supplementary Fig.7b). In an attempt to refine the association at this locus further, we analysed Immunochip data from 1,553 German AD cases and 3,640 population controls, 767 and 983 of which were part of the replication stage. The Immunochip is a custom content Illumina iSelect array focusing on autoimmune disorders, and offers an increased resolution at 5q31. In the population tested, the strongest signal was seen for the IL13 SNP rs848 (p=1.93×10−10), which is in high LD with the functional IL13 variant rs20541 (r2=0.979, D’=0.995). Further significant signals were observed for a cluster of tightly linked variants in IL4 (lead SNP rs66913936, p= 2.58×10−8) and KIF3A (rs2897442, p=8.84×10−7) (Supplementary Tables 6,7; Supplementary Fig.8). While rs2897442 showed only weak LD with rs848 (r2=0.160, D’=0.483), it was strongly correlated with rs66913936 (r2=0.858, D’=0.982). Likewise, pair-wise genotype-conditioned analyses showed that the significant association of rs2897442 with AD was abolished upon conditioning on rs66913936, whereas there was a remaining signal after conditioning on rs848 (Supplementary Tables 6,7). Analysis of LCL expression levels of all genes within 500kb of rs2897442 in ALSPAC revealed a modest association between rs2897442 and IL13 transcript levels (p=2.7×10−3). No associations with any transcript levels within 500kb of the proxy variant rs2299009 (r2=1) were seen in the MuTHER skin eQTL data (Supplementary Fig.6). However, this does not exclude a regulatory effect in another tissue or physiological state, involvement of causative variants in LD with these SNPs in long-range control of more distant genes33, or different functional effects such as alternative splicing.

It is well known that genes that participate in the same pathway tend to be adjacent in the human genome and coordinately regulated34. Thus, our results and previous findings suggest that there are distinct effects at this locus, which might be part of a regulatory block. Further efforts including detailed sequencing and functional exploration are necessary to fully explore this locus.

Variants rs2164983, rs1327914 and rs10983837 showed evidence of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis (p<0.01). The overall random effects results for these variants were OR=1.14 (95%CI 1.05 −1.24), p=0.001; OR=1.06 (95%CI 1.00 - 1.13), p=0.058; and OR=1.11 (95%CI 0.98 - 1.20) p=0.155, respectively. Stratified analysis showed that the effects of rs2164983 and rs1327914 were stronger in the childhood AD cohorts (OR=1.23, p=2.9×10−9; OR=1.12, p=2.5×10−4) as compared to those studies that included AD cases of any age (OR=1.17, p=0.002; OR=1.02, p=0.584, p-value for the differences p=0.031 and p=0.028, respectively) (Supplementary Fig.9). This did not fully explain the heterogeneity for rs2164983 (in the childhood only cohorts the p-value for heterogeneity was still p<0.01). COPSAC (Copenhagen Studies on Asthma in Children) is noticeably in the opposite direction and excluding this study gives a heterogeneity p-value of 0.069 (OR=1.17, p=8.1×10−10). However, COPSAC is diagnostically and demographically comparable to the other cohorts and so there is no obvious reason why this cohort should give such a different result. Neither stratification by age of diagnosis nor whether a physician’s diagnosis was a case criterion explained the heterogeneity observed for rs10983837. Stratified analyses also indicated a stronger effect of rs2897442 in studies with a more stringent definition of AD (reported physician’s diagnosis) (OR=1.14, p=7.0×10−9) as compared to studies where AD was defined as self-reported history of AD only (OR=1.05, p=0.119) (Supplementary Fig.9). These observations underline the importance of careful phenotyping and support the claim of distinct disease entities rather than one illness as is reflected by current rather broad and inclusive concepts of AD. It is anticipated that the results of molecular studies will enable a more precise classification of AD.

In summary, in this large-scale GWAS on 11,025 AD cases and 40,398 controls we have identified and replicated two novel AD risk loci near genes which have annotations that suggest a role in epidermal proliferation and differentiation, supporting the importance of abnormalities in skin barrier function in the pathobiology of AD. In addition, we observed a genome-wide significant association signal from within the cytokine cluster on 5q31.1, this appeared to be due to two distinct signals, one centered on RAD50/IL13 and the other on IL4/KIF3A, both of which showed moderate association with IL13 expression. We further observed a signal in the epidermal differentiation complex, representing the FLG locus, and replicated the 11q13.5 variant identified in the only other (smaller) European GWAS on AD published to date. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that AD is caused by both epidermal barrier abnormalities and immunological features. Further studies are needed to identify the causal variants at these loci and to understand the mechanisms through which they confer AD risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The full list of acknowledgements for each study is in the Supplementary Note.

APPENDIX

Methods

Discovery Analysis

For the discovery analysis we used 5,606 AD cases and 20,565 controls of European descent from 16 population-based cohorts, 10 of which were birth cohorts. Details on sample recruitment, phenotypes and summary details for each collection are given in the Supplementary Methods and in Supplementary Table 1. Genome-wide genotyping was performed independently in each cohort with the use of various standard genotyping technologies (see Supplementary Table 2). Each study independently conducted imputation with reference to HapMap release 21 or 22 CEU phased genotypes, and performed association analysis using logistic regression models based on an expected allelic-dosage model for SNPs, adjusting for sex and ancestry-informative principal components, as necessary. SNPs with a minor allele frequency <1% and poor imputation quality (R2<0.3 if using MACH or proper-info<0.4 if using IMPUTE imputation algorithm) were excluded. After genomic control at individual study levels, we combined association data for ~2.5 million imputed and genotyped autosomal SNPs into an inverse-variance fixed-effects additive-model meta-analysis. There was little evidence for population stratification at study level (λGC<=1.08, Supplementary Table 2) or at the meta-analysis level (λGC=1.02), and the quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot of the meta-statistic showed a marked excess of detectable association signals well beyond those expected by chance (Supplementary Fig.1).

Replication Analysis

For replication we selected the most strongly associated SNPs from the 10 most strongly associated loci in the discovery meta-analysis (all were P < 10−5 in stage 1, Table 1). These SNPs were analysed using in silico data from 11 GWA sample sets not included in the discovery meta-analysis and additional de novo genotyping in a further 3 studies (Supplementary Tables 1,2), for a maximum possible replication sample size of 5,419 cases and 19,833 controls, all of European descent. Each study again conducted the association analyses using a logistic regression model with similar covariate adjustments, based on expected allelic dosage for the in silico studies and allele counts in the de novo genotyping studies and the results were meta-analysed in Stata 11.1 software (Statacorp LP, Texas, USA). We applied a threshold of p<5×10−8 for genome-wide significance and tested for overall heterogeneity of the discovery and replication studies using the Cochran’s Q-statistic.

Immunochip Analysis Methods

We evaluated 1,553 German AD cases and 3,640 German population controls. Cases were obtained from German university hospitals (Technical University Munich as part of the GENEVA study, and University of Kiel). AD was diagnosed on the basis of a skin examination by experienced dermatologists according to standard criteria in the presence of chronic or chronically relapsing pruritic dermatitis with the typical morphology and distribution6. Controls were derived from the KORA population-based surveys35 and the previously described population-based Popgen Biobank36. 767 of the cases and 983 of the controls were also part of the replication stage. Samples with > 10% missing data, individuals from each pair of unexpected duplicates or relatives, as well as individuals with outlier heterozygosities of ±5 s.d. away from the mean were excluded. The remaining Immunochip samples were tested for population stratification using the principal components stratification method, as implemented in EIGENSTRAT37. The results of principal component analysis revealed no evidence for population stratification. SNPs that had >5% missing data, a minor allele frequency <1% and exact Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium Pcontrols <10−4 were excluded. Association P values were calculated using χ2 tests (d.f. = 1) and conditional association was analyzed using logistic regression both implemented in PLINK38 from where we also derived odds ratios and their respective confidence intervals.

ALSPAC Expression Analysis Methods

997 unrelated ALSPAC individuals for which LCLs had been generated had RNA extracted using Qiagen’s Rneasy extraction kit and amplified using Ambion’s illumina totalprep 96 RNA amplification kit and expression surveyed using the Illumina HT-12 v3 bead arrays. Each individual was run with 2 replicates. Expression data was normalized by quantile normalization between replicates and then median normalization across individuals. 949 ALSPAC individuals had both expression levels and imputed genome-wide SNP data available (see ALSPAC replication cohort genotyping above). For each of the three AD replicated SNPs (rs479844, rs2164983 and rs2897442, we used linear regression in Mach2QTL to investigate the association between each SNP and any transcript within +/− 500kb of the SNP.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Study level data analysis L Paternoster, M Standl, A Ramasamy, K Bønnelykke, L Duijts, MA Ferreira, AC Alves, JP Thyssen, E Albrecht, H Baurecht, B Feenstra, P Hysi, NM Warrington, I Curjuric, R Myhre, JA Curtin, MM Groen-Blokhuis, M Kerkhof, A Sääf, A Franke, D Ellinghaus, SB Montgomery, BS Pourcain, JP Kemp, NJ Timpson, M Müller-Nurasyid, F Geller, M March, M Mangino, TD Spector, V Bataille, CMT Tiesler, E Thiering, M Imboden, A Simpson, JJ Hottenga, HA Smit, B Chawes, E Kreiner-Møller, E Melén, A Custovic, B Jacobsson, NM Probst-Hensch, D Glass, DL Jarvis, D Strachan

Study design L Paternoster, M Standl, CM Chen, L Duijts, JP Thyssen, B Feenstra, PM Sleiman, M Kerkhof, E Dermitzakis, AL Hartikainen, A Pouta, J Pekkanen, M Kaakinen, GD Smith, J Henderson, HE Wichmann, N Novak, A Linneberg, T Menné, EA Nohr, A Hofman, AG Uitterlinden, CM van Duijn, F Rivadeneira, JC de Jongste, RJ van der Valk, HA Boyd, JC Murray, TD Spector, P Sly, W Nystad, A Simpson, D Postma, GH Koppelman, HA Smit, H Bisgaard, DI Boomsma, A Custovic, NM Probst-Hensch, H Hakonarson, M Melbye, DL Jarvis, VW Jaddoe, C Gieger, MR Jarvelin, J Heinrich, DM Evans, S Weidinger

Writing paper L Paternoster, M Standl, A Ramasamy, K Bønnelykke, J Heinrich, DM Evans, S Weidinger

Data collection K Bønnelykke, L Duijts, JP Thyssen, B Feenstra, R Myhre, M Kerkhof, R Fölster-Holst, E Dermitzakis, SB Montgomery, AL Hartikainen, A Pouta, J Pekkanen, M Kaakinen, DL Duffy, PA Madden, AC Heath, GW Montgomery, PJ Thompson, MC Matheson, PL Souëf, J Henderson, SM Ring, W McArdle, A Linneberg, T Menné, EA Nohr, JC de Jongste, RJ van der Valk, M Wjst, R Jogi, F Geller, HA Boyd, JC Murray, F Mentch, TD Spector, V Bataille, CE Pennell, PG Holt, P Sly, M Imboden, W Nystad, A Simpson, D Postma, GH Koppelman, HA Smit, B Chawes, E Kreiner-Møller, H Bisgaard, E Melén, DI Boomsma, A Custovic, B Jacobsson, NM Probst-Hensch, LJ Palmer, M Melbye, DL Jarvis, VW Jaddoe, NG Martin, MR Jarvelin, J Heinrich, S Weidinger

Genotyping R Myhre, A Franke, AIF Blakemore, JL Buxton, P Deloukas, SM Ring, N Klopp, E Rodríguez, W McArdle, A Linneberg, AG Uitterlinden, F Rivadeneira, M Wjst, C Kim, CE Pennell, T Illig, C Söderhäll, B Jacobsson, LJ Palmer, MR Jarvelin

Revising and reviewing paper L Paternoster, M Standl, CM Chen, A Ramasamy, K Bønnelykke, L Duijts, MA Ferreira, AC Alves, JP Thyssen, E Albrecht, H Baurecht, B Feenstra, PM Sleiman, P Hysi, NM Warrington, I Curjuric, R Myhre, JA Curtin, MM Groen-Blokhuis, M Kerkhof, A Sääf, A Franke, D Ellinghaus, R Fölster-Holst, E Dermitzakis, SB Montgomery, AL Hartikainen, A Pouta, J Pekkanen, AIF Blakemore, JL Buxton, M Kaakinen, DL Duffy, PA Madden, AC Heath, GW Montgomery, PJ Thompson, MC Matheson, PL Souëf, BS Pourcain, GD Smith, J Henderson, JP Kemp, NJ Timpson, P Deloukas, SM Ring, HE Wichmann, M Müller-Nurasyid, N Novak, N Klopp, E Rodríguez, W McArdle, A Linneberg, T Menné, EA Nohr, A Hofman, AG Uitterlinden, CM van Duijn, F Rivadeneira, JC de Jongste, RJ van der Valk, M Wjst, R Jogi, F Geller, HA Boyd, JC Murray, C Kim, F Mentch, M March, M Mangino, TD Spector, V Bataille, CE Pennell, PG Holt, P Sly, CMT Tiesler, E Thiering, T Illig, M Imboden, W Nystad, A Simpson, JJ Hottenga, D Postma, GH Koppelman, HA Smit, C Söderhäll, B Chawes, E Kreiner-Møller, H Bisgaard, E Melén, DI Boomsma, A Custovic, B Jacobsson, NM Probst-Hensch, LJ Palmer, D Glass, H Hakonarson, M Melbye, DL Jarvis, VW Jaddoe, C Gieger, D Strachan, NG Martin, MR Jarvelin, J Heinrich, DM Evans, S Weidinger

References

- 1.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SJ, McLean WHI. Eczema genetics: current state of knowledge and future goals. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:543–552. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morar N, Willis-Owen SAG, Moffatt MF, Cookson WOCM. The genetics of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:24–34. 35–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer CNA, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez E, et al. Meta-analysis of filaggrin polymorphisms in eczema and asthma: robust risk factors in atopic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1361–70. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esparza-Gordillo J, et al. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun LD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Chinese Han population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:690–694. doi: 10.1038/ng.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffatt MF, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li B, et al. Ovol1 regulates meiotic pachytene progression during spermatogenesis by repressing Id2 expression. Development. 2005;132:1463–1473. doi: 10.1242/dev.01658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair M, et al. Ovol1 regulates the growth arrest of embryonic epidermal progenitor cells and represses c-myc transcription. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:253–264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai X, et al. The ovo gene required for cuticle formation and oogenesis in flies is involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3452–3463. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowanetz M, Valcourt U, Bergström R, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Id2 and Id3 define the potency of cell proliferation and differentiation responses to transforming growth factor beta and bone morphogenetic protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4241–4254. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4241-4254.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, et al. The LEF1/beta -catenin complex activates movo1, a mouse homolog of Drosophila ovo required for epidermal appendage differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6064–6069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092137099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens P, Han G, Li AG, Wang XJ. The role of Smads in skin development. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:783–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widelitz RB. Wnt signaling in skin organogenesis. Organogenesis. 2008;4:123–133. doi: 10.4161/org.4.2.5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buschke S, et al. A decisive function of transforming growth factor-?/Smad signaling in tissue morphogenesis and differentiation of human HaCaT keratinocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:782–794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-11-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maganga R, et al. Secreted Frizzled related protein-4 (sFRP4) promotes epidermal differentiation and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanowska M, et al. Wnt5a exhibits layer-specific expression in adult skin, is upregulated in psoriasis, and synergizes with type 1 interferon. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nica AC, et al. The architecture of gene regulatory variation across multiple human tissues: the MuTHER study. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apte SS. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31493–31497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.052340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter S, Clark IM, Kevorkian L, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem J. 2005;386:15–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollard TD. The cytoskeleton, cellular motility and the reductionist agenda. Nature. 2003;422:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nature01598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winder SJ. Structural insights into actin-binding, branching and bundling proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:14–22. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. Beta-catenin hits chro matin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:276–286. doi: 10.1038/nrm2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang M, et al. Variants in the 5q31 cytokine gene cluster are associated with psoriasis. Genes Immun. 2008;9:176–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nair RP, et al. Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL -23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Genet. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, et al. The 5q31 variants associated with psoriasis and Crohn’s disease are distinct. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2978–2985. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weidinger S, et al. Genome-wide scan on total serum IgE levels identifies FCER1A as novel susceptibility locus. PLoS Genet. e1000166;4:2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vercelli D. Discovering susceptibility genes for asthma and allergy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:169–182. doi: 10.1038/nri2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinjan DA, van Heyningen V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:8–32. doi: 10.1086/426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sproul D, Gilbert N, Bickmore WA. The role of chromatin structure in regulating the expression of clustered genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:775–781. doi: 10.1038/nrg1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holle R, Happich M, Löwel H, Wichmann HE, MONICA/KORA Study Group KORA–a research platform for population based health research. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S19–S25. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krawczak M, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price A, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.